#continental light dragoons

Text

Turnsgiving 2022: Day 4

What If?

After doing more research for both SS&SP and my own college project, I definitely think Turn should’ve included more or Benjamin Tallmadge’s military escapades, which were with his regiment, the 2nd Continental Light Dragoons. They were active in the important battles of the Philadelphia Campaign and then there were raids led by Tallmadge in New York throughout the rest of the war against the British for their supplies and territory. They also served as part of General Washington’s life guard. Turn showed a couple these at The Battle of Stony Point and the Battle of Fort St. George, but on a lesser scale. I could say a lot more, but I’ll refrain from going full military history nerd at the moment. In my opinion, it wouldn’t have derived too much of the “spying” from the show’s plot because one of the Dragoon’s jobs was reconnaissance- patrols to get enemy troop numbers, camp locations, and amount of weapons and supplies they had. Cavalrymen were respected because of the ability they had to have as horsemen, shooters, messengers, and scouts. One of their other key roles? Filling space in General Washington’s guard. Showing more of Benjamin’s cavalry duties would’ve shown how intelligent he was and why he was capable of being Washington’s spymaster.

#SHOW ME MORE DRAGOONS#I LOVE DRAGOONS#the Continental dragons? my best friends#I have to be a horse girl on main#benjamin tallmadge#turn: washington's spies#turnsgiving2022#continental Dragoons#2nd Continental Light Dragoons

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Abe sassy hand on hip stanceTM

#( ooc )#( crack )#( Abe wants to speak with your manager )#( or rather to the captain of the 2nd continental light dragoons )

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I need a reenactment tumblr tag (other than bluecoat posting), help me decide… pretty pls. 🥺

#meera.txt#tumblr polls#personal#american revolution#historical reenactment#reenactment#queue are more than what people see

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

The world turned upside down

On this day in history: October 19th, 1781. Charles Cornwallis surrendered to the combined troops of George Washington and the patriots French allies. Symbolically raising a white handkerchief and giving up a sword to Washington as a sign of civil surrender. Famously when the sword was offered to the French, they refused saying, “we are subordinate to the Americans now.” Famously, Alexander Hamilton and John Laurens had stormed the the English silently by force the previous night. Amongst other heroes, holding position in case Laurens and Hamilton need retreat, was the 2nd continental light dragoons, better known to some as “Sheldon’s horse” or “Benjamin Tallmadge’s unit.” Famously, ill or humiliated, all the English showed up to formally surrender, expect Banastre Tarelton and Cornwallis himself. Legend has it, though the historical records never say, the English played the famous folk song (dating about to 1646) titled “When the King enjoys his own” perhaps more aptly titled in this scenario “the world turned upside down.”

youtube

Yorktown: PBS.

Mount Vernon: Yorktown.

Siege of Yorktown by Henry Freeman.

Hamil-film: Yorktown.

#battle of Yorktown#on this day in history#history#18th century#american revolution#18th century history#meerathehistorian#george washington#charles cornwallis#marquis de lafayette#1780s#john laurens#historical alexander hamilton#historical john laurens#historical lams#benjamin tallmadge#ben tallmadge#banastre tarelton#turn: washington's spies#turn amc#amc turn#turn washington's spies#queue are made by history

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Establishment of the American Army,” in which Congress set out details regarding the Army’s structure, organization, and other details. May 27, 1778.

Record Group 360: Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional Convention

Series: Papers of the Continental Congress

File Unit: Reports of the Board of War and Ordnance

Transcription:

339

IN CONGRESS, May 27, 1778.

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE AMERICAN ARMY.

I. I N F A N T R Y.

Resolved, That each batallion of infantry shall consist of nine companies, one of which shall be of light infantry; the light infantry to be kept compleat by drafts from the batallion, and organized during the campaign into corps of light infantry:

That the batallion of infantry consist of

Pay per month.

[bracket] Commissioned

I Colonel and Captain 75 dollars.

I Lieutenant Colonel and Captain, 60

I Major and Captain, - 50

6 Captains, each 40

I Captain Lieutenant - 26 2-3ds.

8 Lieutenants, each 26 2-3ds.

9 Ensigns, each 20

Paymaster,

Adjutant, } to be taken from the line { 20 doll. } In addition to their pay as officers in the line.

Quart. [Quarter] Master, } { 13 }

} { 13 }

I Surgeon, - 60 dollars.

I Surgeon's Mate, - 40

I Serjeant Major, - 10

I Quartermaster Serjeant, - 10

27 Serjeants, each, 10

I Drum Major, - - 9

1 Fife Major, - - 9

18 Drums and Fifes, each, 7 1-3d.

27 Corporals, each, 7 1-3d.

477 Privates each, 6 2-3ds.

Each of the field officers to command a company.

The Lieutenant of the Colonel's company to have the rank of Captain Lieutenant.

[Math in the margins]

553

3

----

1659

533

3

----

1599 [/Math in the margins]

II. A R T I L L ERY

That a batallion of artillery consist of

Pay per month.

[bracket] Commissioned

I Colonel, - - 100 dollars.

I Lieutenant Colonel, - 75

I Major, - - 62 1-half

12 Captains, each 50

12 Captain Lieutenants, each 33 1-3d.

12 First Lieutenants, each 33 1-3d.

36 Second Lieutenants, each 33 1-3d.

Paymaster,

Adjutant, } to be taken from the line { 25 doll. } In addition to their pay as officers in the line.

Quart. [Quarter] Master, } { 16 }

} { 16 }

I Surgeon, - 75 dollars.

I Surgeon's Mate, - 50

I Serjeant Major, - 11 23-90ths.

I Quartermaster Serjeant, - 11 23-90ths.

I Fife Major, - - 10 38-90ths.

I Drum Major, _ _ 10 38-90ths.

72 Serjeants, each 10

72 Bombardiers, each 9

72 Corporals, each 8 2-3ds.

72 Gunners, each 8 2-3ds.

336 Matrosses each 8 1-3d.

III. C A V A L R Y.

That a batallion of cavalry consist of

Pay per month.

Dollars.

[bracket] Commissioned

I Colonel, - - 93 3-4ths.

I Lieutenant Colonel, - 75

I Major, - - 60

6 Captains, each 50

12 Lieutenants , each 33 1-3d.

6 Cornets, each 26 2-3ds.

1 Riding Master, - - 33 1-3d.

Paymaster,

Adjutant, } to be taken from the line { 25 doll. } In addition to their pay as officers in the line.

Quart. [Quarter] Master, } { 15 }

} { 15 }

I Surgeon, - - 60 dollars.

I Surgeon's Mate, - - 40

I Sadler, - - 10

1 Trumpet Major, - - 11

6 Farriers, each 10

6 Quarter Master Serjeants each 15

6 Trumpeters, each 10

12 Serjeants each 15

30 Corporals, each 10

324 Dragoons, each 8 1-3d.

IV. P R O V O S T

RESOLVED, That a Provost be established, to consist of

Pay per month.

I Captain of Provosts - 50 dollars.

4 Lieutenants, each 33 1-3d.

I Clerk, - - 33

I Quartermaster Serjeant, - 15

2 Trumpeters, each 10

2 Serjeants, each 15

5 Corporals, each 10

43 Provosts or Privates, each 8 I-3d.

4 Executioners, each 10

This corps to be mounted on horse-back, and armed and accoutred as light dragoons.

RESOLVED, That in the E N G I N E E R I N G department three companies be established, each to consist of

Pay per month

I Captain, 50 dollars.

3 Lieutenants, each 33 I-3d.

4 Serjeants, each 10

4 Corporals, each 9

60 Privates, each 8 I-3d.

These companies to be instructed in the fabrication of fieldworks, as far as relates to the manual and mechanical part. Their business shall be to instruct the fatigue parties to do their duty with clarity and exactness: To repair injuries done to the works by the enemy's fire, and to prosecute works in the face of it. Commissioned officers to be skilled in the necessary branches of the mathematics: The non-commissioned officers to write a good hand.

RESOLVED, That the adjutant and quartermaster of a regiment be nominated by the field officers out of the subalterns, and presented to the commander in chief or the Commander in a separate department for approbation; and that being approved of, they shall receive him a warrant agreeable to such nomination.

That the Paymaster of a regiment be chosen by the officers of the regiment out of the Captains or Subalterns, and appointed by warrant as above: the officers are to risque their pay in his hands: the Paymasters to have the charge of the cloathing, and to distribute the same.

RESOLVED, That the brigade major be appointed a heretofore by the commander in chief, or commander in a separate department, out of the captains in the brigade to which he shall be appointed.

That the brigade quartermaster be appointed by the quartermaster general, out of the captains or subalterns in the brigade to which he shall be appointed.

RESOLVED, That two aids-de-camp be allowed to each major general, who shall for the future appoint them out of the captains or subalterns.

REOLVED, That in addition to their pay as officers in the line there be allowed to

An Aid-de-Camp, 24 dollars per month.

Brigade Major, 24

Brigade Quartermaster, 15

RESOLVED, That when any of the staff officers appointed from the line are promoted above the ranks in the line out which they are respectively appointable, their staff appointments shall thereupon be vacated.

The present aids-de-camp and brigade majors to receive their present pay and rations.

RESOLVED, That aids-de-camp, brigade majors, and brigade quartermasters, heretofore appointed from the line, shall hold their present ranks and be admissible into the line again in the same rank they held when from the line; provided that no aid, brigade major, or quartermaster, shall have the command of any officers who commanded him while in the line.

RESOLVED, That whenever the adjutant general shall be appointed from the line, he may continue to hold his rank and commission in the line.

RESOLVED, That when the supernumerary lieutenants are continued under this arrangement of the batallions, who are to do the duty of ensigns, they shall be intitled to hold their rank and to receive the pay such rank intitled them to receive.

RESOLVED, That no more colonels be appointed in the infantry; but where any such commission is or shall become vacant, the batallion shall be commanded by a lieutenant colonel, who shall be allowed the same pay as is now granted to a colonel of infantry, and shall rise in promotion from that to the rank of brigadier: and such batallion shall have only two field officers, viz. a lieutenant colonel and major, but it shall have an additional captain.

M A Y 29, 1778.

RESOLVED, That no persons hereafter appointed upon the civil staff of the army shall hold or be intitled to any rank in the army by virtue of such staff appointment.

[page 2]

JUNE 2, 1778

RESOLVED, That the officers herein after mentioned be intitled [sic] to draw one ration a day, and no more; that where they shall not draw such ration, they shall not be allowed any compensation in lieu thereof.

AND to the end that they may be enabled to live in a manner becoming their stations.

RESOLVED, That the following sums be paid to them monthly for their subsistence, viz.

To every Colonel, 50 dollars per month.

To every Lieutenant Colonel, 40

To every Major, 30

To every Captain, 20

To every Lieutenant and Ensign, 10

To every Regimental Surgeon, 30

To every Regimental Surgeon's Mate, 10

To every Chaplain of a brigade, 50

RESOLVED, That subsistence money be allowed to officers and others on the staff in lieu of extra rations, and henceforward none of them be allowed to draw more than one ration a day.

ORDERED, That the committee of arrangement be directed to report to Congress as soon as possible such an allowance as they shall think adequate to the station of the respective officers and persons employed on the staff.

NOVEMBER 24, 1778

CONGRESS took into consideration the report of the committee of arrangement, and thereupon came to the following resolutions:

WHEREAS the settlement of rank in the army of the United States has been attended with much difficulty and delay, inasmuch as no general principles have been adopted and uniformly pursued;

RESOLVED, therefore, That upon and dispute of rank the following rules shall be hereafter observed;

1. For determining rank in the continental line between all colonels and inferior officer of different States, between like officers of infantry and those of horse and artillery appointed under the authority of Congress, by virtue of a resolve of the 16th of September, 1776, or by virtue of any subsequent resolution prior to the 1st of January, 1777, all such officers shall be deemed to have their commissions dated on the day last mentioned, and their relative rank with respect to each other in the continental line of the army shall be determined by their rank prior to the 16th day of September, 1776. This rule shall not be considered to affect the rank of the line within any State, or within the corps of artillery, horse, or among the sixteen additional batallions [sic], where the rank hath been settled; but shall be the rule to determine the relative rank within the particular line of artillery so far as the rank remains unsettled.

2. In the second instance preference shall be given to commissions in the new levies and flying camp.

3. In determining rank between continental officers in other respects equal, proper respect shall be had to their commissions in the militia, where they have served in the continental army for the space of one month.

4. All colonels and inferior officers appointed to vacancies since the 5th day of January, 1777, shall take rank from the right of succession to such vacancies.

5. In all cases where the rank between the officers of different States is equal, between an officer of State-troops and one of cavalry, artillery, or of the additional batallions [sic] the precedence is to be determined by long.

6. All officers who have been prisoners with the enemy being appointed by their State, and again enter into the service, shall do it agreeably to the above rule; that is to say, all of the rank of captains, and under, shall enter into the same regiment to which they formerly belonged, and if such regiment is dissolved or otherwise reduced, they shall be intitled [sic] to the first vacancy in any regiment of the State in their proper rank, after the officers belonging to such regiments have been provided for.

7. The rules of rank above laid down between officers of different States are to govern between officers of the same State, except in cases where the State may have laid down a different rule, or already settled their rank.

8. A resignation shall preclude any claim of benefit from former rank under a new appointment.

WHEREAS from the alteration of the establishment, and other causes, many valuable officers have been and may be omitted in the new arrangement as being supernumerary, who from their conduct and services are entitled to the honourable [sic] notice of Congress, and to a suitable provision until they can return to civil life with advantage;

RESOLVED, therefore, That Congress gratefully acknowledge the faithful services of such officers, and that all supernumerary officers be entitled to one year's pay of their commissions respectively, to be computed from the time such officers had leave of absence from the commander in chief on this account: And Congress do earnestly recommend to the several States to which such officers belong, to make such farther [sic] provision for them as their respective circumstances and merits entitle them to.

WHEREAS it will be for the benefit of the service that some rule for promotions be established; therefore

RESOLVED, That it be recommended to the several States to provide that in all future promotions, officers rise regimentally to the rank of captain, and thence in the line of the State to the rank of colonel, except in cases where a preference may be given on account of distinguished merit.

RESOLVED, That all officers who have been in the service, and having been prisoners with the enemy, now are, or hereafter may be exchanged, or otherwise related, shall, if appointed by authority of the State, be entitled in cases of vacancy to enter into the service of their respective State, in such rank as they would have had if they had never been captures; provided always, that every such officer do within one month after his exchange or release, signify to the authority of the State to which he belongs, his release and his desire to enter again into the military service.

RESOLVED, That every officer so released, and giving notice as aforesaid, shall until entry into actual service be allowed half pay of the commission to which by the foregoing resolve he stand entitled; provided always, that in case of his receiving any civil office of profit, such half pay shall thenceforth cease.

RESOLVED, That no brevets be for the future granted, except to officers in the line, or in case of very eminent services.

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MAJOR BENJAMIN TALLMADGE // INTEREST TRACKER

MUSE STATUS: SECONDARY

(By liking this post, you are indicating interest in plotting with this character, and are OK with me sending memes/prompts to your inbox!)

NAME: Benjamin Tallmadge

ALT NAMES: Major (Benjamin) Tallmadge, Major, Tallboy, Bennyboy, John Bolton

SEX/GENDER/PRONOUNS: Male, he/him

SEXUALITY: Bisexual

FACECLAIM: Seth Numrich

AGE: Late 20′s

NATIONALITY/ETHNICITY: American / caucasian, white

HEIGHT: 6′0″

BUILD/BODY TYPE: He’s a fit, fuzzy twink with a cavalryman booty.

HAIR: Dark honey blonde

EYES: Blue

PINTEREST BOARD

ALL ABOUT BEN:

Per the Turn Wiki here,

Major Benjamin Tallmadge (born February 25, 1754) is an officer for the Continental Army and the 2nd Continental Light Dragoons that went on to become a spy for them during the American Revolutionary War. Joining together with childhood friends Caleb Brewster and Abraham Woodhull, the three formed what would later become the Culper Ring.

The organization received the aid and assistance of various others, including Abe's former lover, Anna Strong. The organization would report to Commander-in-Chief, George Washington. Tallmadge was a Captain until the official founding of the Culper Ring in 1777 and was promoted to Major soon after.

It's clear through his actions that Benjamin Tallmadge is a strong, loyal soldier and a leader with honorable intentions... most of the time. He isn't afraid to bend rules when absolutely necessary, but can sometimes be led too far by his emotions and his own personal sense of justice. Duty and honor are extremely important to him, as are loyalty and trust and the value of his friends; those things he places above all else. He takes his duties very seriously, and there are times he might come off as just an innocent preacher’s son from a backwater fishing village... but he is so much more.

Underneath the pomp and attempts at restraint is a young man who can be hot-headed and stubborn, mischievous, even playful. There are a lot of emotions pent up behind his officer's restraint--a boy trying to become a man, to live up to the image of a gentleman and an officer who carries the burden of command and of the guilt of fallen friends, comrades, and family. All of those ideals and baggage and the burden of caring about so many things and so many people can really weigh on him, can cause him to be short-sighted, restless, irrational. He’s trying--he’s trying to keep himself together, trying to keep the Culper Ring together, trying to run a spy network, trying not to get his friends killed, his dragoons killed, himself killed. As he goes through the war, he grows and becomes disillusioned in some things--namely, Washington himself--but despite everything, he continues to push ever onward for the cause and most importantly, for his loved ones.

WARNINGS: RPing with this character will involve sensitive topics such as mental illness/depression/PTSD, violence/gore/injuries, crude/early surgical and medical topics, amputation, racism/colonialism/imperialism/nationalism, slavery, socio-economic issues past & present, homophobia past & present, possible discussions of cannibalism & definite discussions of war & murder.

By liking this post and indicating your interest to engage in RP with this character, you are accepting the above warnings and have read the rules posted here on this blog.

#.// a cavalry lad (ben)#.// a formal feeling comes (character pages)#.// hope perches in the soul (ooc)#image is a placeholder

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

24 Days of La Fayette – Day 16: François-Louis Teissèdre de Fleury

Today’s aide-de-camp is François-Louis Teissèdre de Fleury, Marquis de Fleury and son of François Teisseydre de Fleury. He was born in 1749 and first served in the French army as a volunteer from 1768 onwards. In 1772 he was made sous-aide-major in the Rouergue Regiment.

While La Fayette and his group of fellow travelers are certainly among the most famous foreign personal in the continental army, their idea was by no means novel. There were several groups of Frenchman that tried one way or another to join the War in America (and for one reason or another). Fleury was part of such a group - and he was one of the, comparatively speaking, few successful ones.

He was made a Captain of Enginers by the Continental Congress on May 22, 1777 and was awarded 50 Dollar for his travelling expenses. William Heath wrote to George Washington on April 26, 1777:

The Three appear to be Officers of Abilities—They inform me that Mr Dean promised them that their Expences should be born to Philadelphia &c.—I must confess I scarcely know what to do with them, & wish Direction, I have advanced to Col. Conway, as advance pay 150 Dollars to enable him to proceed to Philadelphia—And to Capt. Lewis Fleury 50 Dollars—The latter is engaged as a Capt. Engineer.

“To George Washington from Major General William Heath, 26 April 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 9, 28 March 1777 – 10 June 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999, pp. 277–280.] (12/16/2022)

He was initially assigned to a corps of rifleman but soon got promoted and re-assigned after he fought with distinction at the Battle of Brandywine, where his horse was shot from under him. A Boston newspaper wrote on December 4, 1777:

The Chevalier du Plessis, who is one of General Knox’s Family, had three Balls thro’ his Hat. Young Fleuri’s Horse was killed under him. He shew’d so much Bravery, and was so useful in rallying the Troops, that the Congress have made him a Present of another.

“Extract from a Boston Newspaper, [after 4 December 1777],” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 25, October 1, 1777, through February 28, 1778, ed. William B. Willcox. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986, pp. 244–245.] (12/16/2022)

Fleury also participated in the Battle of Germantown, where, in classical La Fayette-fashion, he was wounded in the leg. The General Orders from October 3, 1777 read as follows:

Lewis Fleury Esqr. is appointed Brigade Major to The Count Pulaski, Brigadier General of the Light Dragoons, and is to be respected as such.

“General Orders, 3 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 11, 19 August 1777 – 25 October 1777, ed. Philander D. Chase and Edward G. Lengel. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2001, pp. 372–375.] (12/16/2022)

Fleury was ordered to defend Fort Mifflin on November 4, 1777, where he would be engaged in the attack on Fort Mifflin on November 15 of the same year. Fleury was again wounded but even more important, he kept a very detailed journal and his entries from October 15-19 were often cited to illustrate the events surrounding the attack.

Concerning his wounds (and his personal value) Colonel Samuel Smith wrote to George Washington on November 16, 1777:

Major Fleury is hurt but not very much. he is a Treasure that ought not to be lost.

To George Washington from Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Smith, 16 November 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 12, 26 October 1777 – 25 December 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. and David R. Hoth. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2002, pp. 281–282.] (12/16/2022)

La Fayette became aware of Fleury’s brave conduct and wrote to Henry Laurens on November 18, 1777:

You heard as soon almost as myself of all the interesting niews on the Delaware. The gallant defense of our forts deserves praisespraise and her daughter emulation arethe necessary attendants of an army. I am told that Major Fleury and Captain du Plessis have done theyr duty. It is a pleasant enjoyement for my mind, when some frenchmen behave a la francoise, and I can assure you that everyone who in the defense of our noble cause will show himself worthy of his country shall be mentionned in the most high terms to the king, ministry, and my friends of France when I’l be back in my natal air.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 151-153.

George Washington had recommended Fleury and as a result of this recommendation, Fleury was commissioned a Lieutenant Colonel on November 26. La Fayette was very much in Fleury’s favour, and he wrote again to Henry Laurens on November 29, 1777:

The bearer of my letter is Mr. de Fleury who was in Fort Miflin, and as he is reccommanded by his excellency I have nothing more to say but that I am very sensible of his good conduct. (…) Mr. de Fleury receives just now the commission of lieutenant colonel, I think he wo’nt go to day to Congress, and I send this letter by one other occasion (…)

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 160-161.

Fleury was also recommended by Colonel Henry Leonard Philip, Baron d’Arendt, the commander of Fort Mifflin. Arendt wrote to Alexander Hamilton on October 26, 1777:

Col. Smith who is well acquainted with this place, its defence, and my Intentions respecting them, will make every necessary arrangement in my absence to maintain harmony between himself and Colo. [John] Green—I must do him the justice to say that he is a good Officer and I wish America a great many of the same cast. I must render the same justice likewise to Maj. Fleury who is very brave and active.

Notes of “To George Washington from Brigadier General David Forman, 26 October 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 12, 26 October 1777 – 25 December 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. and David R. Hoth. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2002, pp. 13–16.] (12/16/2022)

George Washington also had something to say about this quarrel between his soldiers. He wrote to James Mitchell Varnum on November 4, 1777:

I thank you for your endeavours to restore confidence between the Comodore & Smith—I find something of the same kind existing between Smith and Monsr Fleury, who I consider as a very valuable Officer. How strange it is that Men, engaged in the same Important Service, should be eternally bickering, instead of giving mutual aid. Officers cannot act upon proper principles who suffer trifles to interpose to create distrust, & jealousy (…)

“From George Washington to Brigadier General James Mitchell Varnum, 4 November 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 12, 26 October 1777 – 25 December 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. and David R. Hoth. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2002, pp. 128–129.] (12/16/2022)

I do not praise you often, but in this case I will – well said, Sir!

There was no division in the army at the present that Fleury could assume command of and he was therefor appointed sub-inspector under the Baron von Steuben. The General Orders from April 27, 1778 read:

Lieutt Coll Fleury is to act as Sub-Inspector and will attend the Baron Stuben ’till Circumstances shall admit of assigning him a Division of the Army—Each Sub-Inspector is to be attended daily by an Orderly-Serjeant drawn by turns from the Brigades of his own Inspection that the necessary orders may be communicated without delay.

“General Orders, 27 April 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 14, 1 March 1778 – 30 April 1778, ed. David R. Hoth. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2004, pp. 657–658.] (12/126/2022)

La Fayette, in the meantime, was lobbying for Fleury and other French officers – apparently to a degree or in a way that he later was unwilling to admit. The following passage was removed by the Marquis from a letter to George Washington from January 20, 1778:

I am told that Mullens is to be lieutenant colonel, if it is so, as that the same commission was done for Mssrs. de Fleury and du Plessis who are on every respect so much out of the line of Mullens who being by his birth of the lowest rank, and not so long ago a private soldier, I hope that those gentlemen are to be at least brigadier generals.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 238-239.

It was around this time that preparations for the Canadian expedition were made – an expedition under La Fayette’s command that never came into fruition and probably was never really intended to do so. It was here that Fleury was appointed aide-de-camp to La Fayette. Horatio Gates wrote to our Marquis on January 24, 1778:

Congress having thought proper and in compliance with the wishes of this Board, from a Conviction of your Ardent Desire to signalize yourself in the Service of these States, to appoint you to the Command of an Expedition meditated against Montreal it is the Wish of the Board that you would immediately repair to Albany, taking with you Lt. Colo. de Fleury, and such other gallant French officers as you think will be serviceable in an Enterprise in that Quarter. (…)

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 249-250.

La Fayette in his turn wrote to Henry Laurens on February 4 and on February 7, 1778 respectively to inform him of the proceedings. He also used the opportunity to get a word for Fleury in and to gossip a bit about the same.

There is Lieutenant Colonel Fleury who not only out of my esteem and affection for him but even by a particular reccommandation of the board of war is destinated to follow me to Canada. I schould have desired of Congress every thing or employement which I could have believed more convenient to his wishes, had I not expected to see him before-you know he was upon my list. He desires to be at the head of an independent troop with the rank of Colonel. I do’nt know which will be the intentions of Congress but every thing which can please Mr. de Fleury not only as a frenchman but as a good officer, and as being Mr. de Fleury will be very agreable to me. (…) I have showed to Colonel Fleury the first lines of my letter, in order to let him know my giving willingly the reccommandation he asks for you. You know that gentleman's merit and that Duplessis and himself were made lieutenant colonels as reward of fine actions.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 279-280.

You have seen Mr. de Fleury. I fancy entre nous that he will not be satisfied in so high pretensions. He is very unhappy that Mr. Duer is no more in Congress because he is his intimate friend and confident-that will perhaps surprise you.’ Mr. de Fleury is entre nous a fine officer but rather too ambitious. When I say such things I beg you to burn the letters.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 282-283.

Henry Laurens replied on February 7, 1778 and his wording at the end especially is quite interesting given La Fayette’s previous letter.

I had the honour this Morning of receiving your Commands by the hands of Lt. Colo. Fleury. This Gentleman notwithstanding the aid of some able advocates in Congress has failed in his pursuit of a Colonel's Commission. You will wonder less, when you learn that the preceeding day I had strove very arduously as second to a warm recommendation from a favorite General, Gates, on behalf of Monsr. Failly, for the same Rank, without effect. The arguments adduced by Gentlemen who have opposed these measures, are strong & obvious. “We are reforming & reducing the Number of Officers in our Army, let us wait the event, & see how our own Native Officers are to be disposed of”-& besides, there is a plan in embrio for abolishing the Class of Colonel in our Army, while the Enemy have none of that Rank in the Field. Some difficulty attended obtaining leave for Monsr. Fleury to follow Your Excellency, Congress were at first of opinion he might be more usefully employed against the shipping in Delaware & formed a Resolve very flattering & tempting to induce him-but his perseverence in petitioning to be sent to Canada, prevailed. Monsr. Fleury strongly hopes Your Excellency will encourage him to raise & give him the Command of a distinct Corps of Canadians. I am persuaded you will adopt all such measures as shall promise advantage to the Service & there is no ground to doubt of your doing every reasonable & proper thing for the gratification & honour of [a] Gentleman of whom Your Excellency speaks & writes so favorably.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 1, December 7, 1776–March 30, 1778, Cornell University Press, 1977, pp. 284-285.

With the failure of the expedition, Fleury once again longed for an independent command and La Fayette wrote to Charles Lee in June of 1778:

One of the best young french officers in America Mr. de Fleury wishes much to be annexed to the Rifle Corps and is desired by Clel. Morgan.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 2, April 10, 1778–March 20, 1780, Cornell University Press, 1978, pp. 62-64.

In the end, Fleury was given command of a light infantry battalion on June 15, 1779. The General Orders for that day read as follows:

The sixteen companies of Light-Infantry drafted from the three divisions on this ground are to be divided into four battalions and commanded by the following officers;

4. companies from the Virginia line by Major Posey.

4—ditto from the Pennsylvania line by Lt Colo. Hay.

4—ditto two from each of the aforesaid lines by Lieutenant Colonel Fleury.

“General Orders, 15 June 1779,” Founders Online, National Archives,[Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 21, 1 June–31 July 1779, ed. William M. Ferraro. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012, p. 176.] (12/16/2022)

He led his battalion into the attack of Stony Point on July 16, 1779. His conduct was, by all accounts, heroic and George Washington wrote on September 30, 1779:

Colo. Fleury who I expect will have the honour of presenting this lettr. to you, and who acted an important & honourable part in the event, will give you the particulars of the assault & reduction at Stony Point (…) He led one of the columns – struck the colours of the garrison with his own hands – and in all respects behaved with intrepidity & intelligence which marks his conduct upon all occasions.

Idzerda Stanley J. et al., editors, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776–1790, Volume 2, April 10, 1778–March 20, 1780, Cornell University Press, 1978, pp. 313-319.

His actions were indeed so gallant that Congress awarded him a silver medal on July 26, 1779. This is indeed quite remarkable since he was the only foreign officer thus honoured. No other foreign officer, not even La Fayette, received such a silver medal during the Revolutionary War.

Fleury obtained a leave of absence from Congress in September of 1779 and left America on November 16. La Fayette was at this time in France as well and was eager to receive a first-hand account from Fleury with respect to political as well as to military matters. Although still in possession of his American commission, Fleury re-entered the French army and was made a Major of the Saintonge Regiment in March of 1780 (this might interest you @acrossthewavesoftime.) A few months later, in July of 1780, he joined General Rochambeau’s expeditionary force. Fleury was one of the French soldiers at the Battle of Yorktown. He left America for good in January of 1783 and sailed from Boston to France. It was only at this point, that he resigned his American commission. In France, he joined the Pondichéry Regiment and was named its Colonel. He was elevated to a maréshal de camp in 1791 and fought in the battle of Mons on April 28-30, 1792. During the retreat, he was wounded for the third time. While his previous injuries were all relative mild, this one appears to have been rather serious. He resigned from the army not long after.

Not much is known about Fleury’s later life, and I have seen drastically different accounts of the time of his death. While some editors of (La Fayette’s) letters/papers have put the date of his death around 1814, it is far more likely that he died in 1799. Fleury never married and there are no known children of his.

François Louis Teisseydre, Marquis de Fleury’s legacy is the De Fleury Medal that is granted to outstanding members of the United States Army Corps of Engineers.

#24 days of la fayette#la fayette's aide-de-camps#marquis de lafayette#french history#la fayette#american history#american revolution#french revolution#letter#history#francois louis teisseydre#marquis de fleury#1777#1778#1772#1779#1780#1783#battle of yorktown#stony point#fort mifflin#henry laurens#george washington#battle of brandywine#battle of germantown#1799#1791#1792#1814#founders online

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

NEW OC BIO (2)

GENERAL INFORMATION

NAME: Charlotte Anne Brewster

NICKNAMES/TITLES: Charlie, Lottie ( VERY select people; namely the Washingtons ), Annie (by her papa, sometimes), Mascot of the Continental Army (by everyone in camp), Brat (by Bradford, Arnold, a few others in camp)

SPECIES: Human

AGE: 15, (mainly playing younger)

GENDER: Cis Female

DATE OF BIRTH: 8 July, 1778

NOTE-WORTHY ABILITIES: hatchet throwing, musket firing, embroidery, cooking, horseback riding

CURRENT RESIDENCE: The Continental Army camp, Setauket (Post War, briefly), Connecticut (Post War), Mt. Vernon, Virginia (during winter months)

OCCUPATION: Does being the middle child count? (Thinks shes the oldest, for a while)

AFFILIATIONS: The Continental Army, 2nd Continental Light Dragoons, the Patriots

SPOKEN LANGUAGES: English, French, Latin, a few words in Iroquoian

PERSONALITY

ALIGNMENT: Chaotic good

ASSETS: switchblade, tin whistle

FLAWS: Naiveté, quick temper

LIKES: going barefoot, the wind in her hair, playing in the woods around camp, spending time in sackett's tent/shop, time on the water with her papa, her younger sister georgie, older sister kaia (eventually), playing hide & seek with uncle robert, playing soldiers with uncle nate, the smell of the salty sea air, campfires, worn leather

DISLIKES: the british, simcoe, arnold, sitting still in one spot for a long period of time, washing laundry, cleaning things, homophobia, transphobia

FEARS/PHOBIAS: fear of abandonment, letting her family down, getting kidnapped, getting hanged

CONNECTIONS

FAMILY: Caleb Brewster (Papa), Benjamin Tallmadge (Dad/Dada), Georgia "Georgie" Lynn (younger sister), Kaia Elizabeth (Older sister), Nate (uncle), Anna Strong (Aunt), Abraham Woodhull (Uncle), Mary Woodhull (Aunt), Thomas Woodhull, Jr, "Sprout" (calls him a cousin), General Washington (surrogate Grandfather, calls him Gampa ), Martha Washington (surrogate Grandmother, calls her Gamma ), Nathaniel Tallmadge ( biological Grandfather, calls him Grandfather), Nathaniel Sackett ( surrogate Grandfather, calls him Pops (learned it from Caleb, he hates it but he can't tell her no), Robert Rogers (Uncle), Robert Townsend (Uncle), Edmund Hewlett (Uncle), Akinbode (Uncle), Abigail (Auntie), Cicero ( sort-of cousin)

FRIENDS: Georgia, Kaia, Nate, Sprout, a few other children in Setauket, New York & Connecticut; her stuffed bear, Bubba

ROMANTIC INTEREST: none, yet, but she grows up to be bisexual, so she has a lot of options, and what with being a Congressman's daughter & the Presidents (sort-of) granddaughter, she has a lot of opportunities for suitors--male, female & non-binary alike.

ENEMIES: simcoe, the british navy, other queens rangers, traitors to the cause, richard woodhull

OTHERS: none atm

FACTS AND TRIVIA:

she says she was born in setauket, if anyone asks, but she was actually born in a small barn on the outskirts of the continental army camp.

she loves wearing hats, especially her papa's. usually has her hair in two braids or loose, trailing down her back. the only time she has her hair up and (semi) neat is if she's at an event with her grandfather(s), church, or at whitehall. (richard wouldn't allow her in otherwise)

#* about / charlie.#* bio / charlotte anne.#[ my fiesty girl ]#[ she is Truly both of her fathers' daughter tbh ]

1 note

·

View note

Text

Three Tokens

The point has been made many times that The Patriot misrepresents several populations that played key roles in the American Revolution. To be honest, it misrepresents all populations involved. The British did not make a habit of targeting civilians (at least no more than the Patriots did), and wealthy South Carolina landowners farmed their lands using slave labor. Apart from these outright lies, though, there is a more insidious misrepresentation involved with three populations not centered by the movie: the French, American Loyalists, and enslaved Black Americans. Each of these groups is represented by one character that is written specifically to present the Patriot cause in a favorable light, or at least deflect criticism away from it.

Major Villeneuve

When we first meet him, Villeneuve has it in for Benjamin Martin. “It is such an honor to meet the hero of Fort Wilderness” he sneers in reference to Martin’s brutal executions of French soldiers during the French and Indian War. It is entirely believable that French soldiers could have held on to such animosities; the war in which they had fought the Americans as enemies only ended thirteen years prior to the start of the American Revolution. Villeneuve’s dialogue with Martin becomes suspicious as he shifts from anger at Martin’s past war crimes to anger with Martin for forbidding his execution of surrendering British soldiers. The British had sunk the ship on which his wife and children were passengers. Just as the French and their Cherokee allies had murdered and raped Colonial civilians just prior to the Fort Wilderness incident. Villeneuve’s judgement of Martin is superseded by his hypocrisy. This becomes a theme wherein characters’ personal experiences are presented as more important than their political beliefs, particularly when those beliefs are critical of Patriot ideas and practices.

James Wilkins

To get the pesky historical facts out of the way first, the idea of using one man to represent Loyalism in a colony characterized by particularly fierce fighting between Loyalists and Patriots is laughable. The audience is given no explanation for why Wilkins would join the Green Dragoons (historically, a Loyalist regiment formed in New York, though apparently not the in the movie given Tavington’s “another Colonial?” comment). Wilkins is the single American Loyalist present in the movie after the Charlestown assembly of 1776, and we are told that he had been part of a Loyalist militia prior to joining the dragoons. What happened to the other Loyalists at the assembly? What happened to the militia? 🤷♀️

We do learn that Wilkins’ Loyalism has a motivation, sort of. It is not revenge, which motivates every single other non-British White man in the movie in spite of South Carolinian Loyalists having ample cause to seek vengeance against Patriots. To Mr. Howard at the assembly he cites the lack of an American nation, and to Tavington he says “Those who make a stand against England deserve to die a traitor’s death.” Frankly, this sounds like the straw man reasoning a Patriot polemist would ascribe to Loyalists, and I suppose that is exactly what it is. He is not loyal to cultural and/political institution of which he is part but to a country across an ocean from his home. Okay, Wilkins. The movie does provide us with a Loyalist perspective; it just happens to be one completely divorced from accurate historical context.

Occam

I’ll confess to falling down a rabbit hole of research about Black Americans’ involvement in the American Revolution for this section, and it was eye-opening. I knew that more Black people supported the British than the Patriots, but I had no idea how enormous the disparity was. The number of enslaved people who took up the Continental Army’s offer of freedom at the end of military service was dwarfed by the numbers of those who directly aided the British or took the chaos of war as an opportunity to escape the plantations. Both of these larger groups are erased in The Patriot. Of the enslaved characters, Occam is the only one to speak, and some on Charlotte’s plantation die for their silence about her whereabouts. The longest speech from a free Black character exists to inform the audience and Tavington that he is free and is almost completely ignored by Tavington.

All this means that Occam is the only character to actually articulate a Black experience of the American Revolution, but he prefers to express himself through his actions. These include staring into middle distance while pensive music plays every time the topic of freedom is raised, risking his life to save the one militia man who treats him as poorly as his enslaver did, fighting for the militia that enslaver gave him to even after he is free, and helping his comrades surprise Benjamin Martin by building him a new house after the war ends. It is hard to imagine that he is going to surprise him again with a bill for his services. In short, Occam celebrates his liberation from slavery by doing volitionally the exact same things he would have been compelled to do as a slave. Freedom, baby!

As egregiously limited as each of these characters are as representations of their respective groups, each contains a grain of truth. There was some held over mistrust between French and American veterans of the previous war. There were Loyalists who partook in atrocities against Patriot civilians. There were Black people, both enslaved and free, who aided the Patriot cause. However, by presenting only one person from each of these populations, the filmmakers use these characters’ individual choices to downplay or silence those populations’ justified grievances with Patriots. There is, however, one South Carolina population from the American Revolution era that is not represented by so much as a single token: the Cherokees. We know they were there; people keep referencing Martin’s victory over them. The tomahawk prominently featured from the opening shot of the movie to Martin’s final fight with Tavington is a trophy from Martin’s Indian fighting days. But the only Cherokee people who appear are the scouts in one blink-and-you-miss-it shot after they deliver the single survivor of Martin’s massacre in the woods to the British camp. That they appear at all begs the question: why is Tavington not using their help to find the militia? They likely know about the mission; their ancestors were there long before the Spanish built it. For once, the movie is accurate; Banastre Tarleton did not receive Cherokee aid either. This was not because the Cherokees chose to forgive and forget with regards to the previous war, as Villeneuve ultimately does, but because they had been driven from the colony by Patriot atrocities that might even have raised Colonel Tavington’s eyebrows.

#the patriot#american revolution#colonel villeneuve#captain james wilkins#occam#representation#racism#i'm too tired to think of all the tags this needs#whew!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHARACTER QUESTIONNAIRE !!

Tagged by: myself.

Tagging: @withinycu, @adrienne-lafayette-official, @johngravessimcoe, @cavalrylad, @musenssang, @philip-hamilton-official, @sharp-teeth-and-wide-grins, @virgosjukebox. 💙

✧・゚ 𝐃𝐀𝐒𝐇 𝐆𝐀𝐌𝐄.

► BENJAMIN TALLMADGE.

Name: Benjamin Tallmadge.

Alias(es): Ben, Major Tallmadge, 2nd Continental Light Dragoon, Tall-boy, & Captain Tallmadge. “Beagle tilting his head.” (Creator of Washington’s spies tv).

“Beagle” “Washington’s hunting dog” (affectionate & derogatory, from both sides)

Gender: male (he/him).

Orientation: not your business.

(Bi, repressed and ashamed about it, but bi, in my personal portrayal and reading/headcanons, having read his memoirs & letters, but the truth is… as with Alexander Hamilton, we’ll never know).

Age: 22-24.

Date of birth: February 25, 1754

Place of birth: Setauket or Brookhaven, Long Island, NYC.

For simplicity he’ll say, New York, sometimes.

Spoken language(s): English, Latin, trying really hard for French thus far not succeeding. Do code books count?

Occupation(s): soldier, spymaster, congressman, statesman. (au: lawyer) (modern verse: law student).

★ ⸻ APPEARANCE

Eye colour: blue, the kind you can drown in, it’s his most attractive feature, according to popular opinion.

Hair colour: dirty blonde.

Height: 6’0” (tall by 18th century standards).

Other: rarely ever seen out of uniform.

Has anxiety & PTSD, should probably touch grass. Deserves a hug and deserves better.

★ ⸻ FAVORITE

Colour: red, white, gold and blue, neutral black that suits everything or gray works to.

Song: Benjamin’s playlist.

Food: bread, salt, cheese, or fish.

Drink: brandy or wine.

★ ⸻ HAVE THEY...

Passed university: Yale college, top of his class!

Had sex: not your business.

Had sex in public: no.

Gotten pregnant/someone else pregnant: wants kids, but not that way, and not at this exact moment. Given the war.

Kissed a boy: no. (Yes) Nathan Hale.

Kissed a girl: yes.

Gotten tattoos: no.

Gotten piercings: no.

Been in love: he’s not sure if it counts, to be blunt, but for reason of answering, yes.

Stayed up 24+ hours: for the cause, yes.

★ ⸻ ARE THEY...

A virgin: not your business, also a construct society cruelly and hypocritically only applies to the fairer sex. (No).

A cuddler: yes.

A kisser: circumstantially.

Scared easily: most certainly not!

Jealous easily: yes!

Submissive: switch.

Dominant: none of your business.

In love: verse/thread dependant.

Relationship status: I am married to honour and the revolution until this is over. (Single).

★ ⸻ RANDOM QUESTIONS

TW for self-harm/suicide mention.

Have they harmed themselves: not unless you count accidentally falling in the Delaware river.

Thought of suicide/ideated: under the pressure of war, atrocities, violence and bloodshed. Yes. But rarely.

Attempted suicide: only if you count a Protestant martyr complex, as the son of a preacher it runs in the family.

Wanted to kill someone: side eyes Simcoe.

But he didn’t enjoy the killing in question.

Have/had a job: Washington’s staff.

Fears: death, abandonment, losing control, not being enough, losing the war, tyranny, his own capacity to help vs harm and the moral dilemma of mundane human existence and soldiering.

Sibling(s):

Samuel Tallmadge.

William Tallmadge.

John Tallmadge.

Isaac Tallmadge.

Parent(s): Susannah Tallmadge (née Smith)(deceased)/Rev. Samuel Tallmadge sr.

Children: verse/thread dependant.

Children In history:

Frederick A. Tallmadge

Maria Jones Tallmadge

William Smith Tallmadge

Harriet Tallmadge Delafield

Benjamin Tallmadge Jr.

Henry Tallmadge.

Significant other(s): Nathan Hale (deceased), Sarah Livingston (ex lover, kinda, sorta, it’s complicated & traumatizing).

Significant other(s) in history:

Mary Floyd (1784 to 1805).

Maria Hallet (1808 til death in 1835).

Pet(s): he should like to have a beagle, or grey hound, but, none presently.

Benjamin’s Wikipedia.

Benjamin’s memoir.

In canon: TURN.

Culper ring.

#muse: benjamin tallmadge#about / to confide or confess#visage / merely aiding nature#meta#headcanon#headcanons#historical verse.#history#historical references

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

✧˖°. 𝑴𝑼𝑺𝑬 𝑰𝑵𝑻𝑹𝑶𝑫𝑼𝑪𝑻𝑰𝑶𝑵 .°˖✧

───────────────────────────────

✧˖°. Muse Status: Open for interaction

✧˖°. Historical setting: 18th Century

✧˖°. Faceclaim: (in process)

✧˖°. AUs: (in process)

───────────────────────────────

𝑷𝒆𝒓𝒔𝒐𝒏𝒂𝒍 𝑫𝒂𝒕𝒂

✧˖°. Name: William Dalton

✧˖°. Nicknames: Will, Dalton, Bill,

✧˖°. Birth: July 13th 1758

✧˖°. Gender: Male

✧˖°. Pronouns: he/him (usually)

✧˖°. Sexuality: Bisexual

✧˖°. Nationality: Irish-American

✧˖°. Mother Tongue: English & Irish

───────────────────────────────

𝑷𝒉𝒚𝒔𝒊𝒄𝒂𝒍 𝑫𝒆𝒔𝒄𝒓𝒊𝒑𝒕𝒊𝒐𝒏

✧˖°. Height: 5'11

✧˖°. Eye colour: Greyish blue

✧˖°. Hair: Curly Blonde

✧˖°. Ethnicity(?: Caucassian

✧˖°. Body type: Slim, slightly muscled.

───────────────────────────────

𝑨𝒅𝒅𝒊𝒕𝒊𝒐𝒏𝒂𝒍 𝑰𝒏𝒇𝒐𝒓𝒎𝒂𝒕𝒊𝒐𝒏

- Family:

Parents:

Ryan Dalton (Father; 1730) & Adara Hayes (Mother; 1736)

Siblings:

Caroline Dalton (Sister; 1762 - 1768 in most AUs)

Extended Family

Cillian (Dalton) Smith (Cousin; 1752 - ?)

Cora Smith (Aunt; 1732 - 1758)

-Occupation/Studies:

AmRev Verse

Lieutenant in the Continental 2nd Light Dragoons Regiment (1778-1781)

Graduated in Law from King's College

-About his life:

(To be edited)

───────────────────────────────

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Turn Week 2023:

History Nerdery!

Hello, and Happy Fourth of July! For today's Turn Week, I wanted to talk about Benjamin's regiment in the Continental Army. We all know he's a Connecticut Dragoon, but what does that mean and what did they do, exactly? I'm going to let you know! The Continental Cavalry is my favorite unit in the army, and I actually did an Honors Research Project on them last year for my college. WARNING: this is going to be LONG. I'm sorry. Kind of.

What is the Continental Cavalry?

The cavalry is the mounted troops in a military force, meaning they fight on horseback. At the time of the Revolution, the cavalry was considered an elite and necessary force for a proper military. Combat on horseback was dangerous- you not only had to avoid cannon and gunfire, but you had to attack other mounted troops with lances and sabers of their own.

There are two types of cavalry: light cavalry and heavy cavalry. The light cavalry had three primary duties. Scouting, which was to patrol enemy forces, movements, and the terrain surrounding camps and battlefields, which also played into reconnaissance. They also served as messengers to officers on and off the battlefield. On the other hand, heavy cavalry was troops used in action. Their objective was to lead charges and weaken the enemy’s unmounted troops, like going after their flanks. They also performed raids/ambushes or small skirmishes against the enemy. Their combat was on and off the battlefield.

Due to the near constant lack of funds for the Continentals, their Dragoons performed both light and heavy cavalry roles. A dragoon/trooper is a soldier who fights either on horseback or on foot, depending on the amount of horse available. They used weapons such as: a cavalry saber, a shortgun, and a musket.

Unlike the British army, which brought over cavalry forces, at the beginning of the war, there was not an official cavalry for the Continentals. Some state and organized militias had mounted troops- such as the Philadelphia Light Horse- but professional, commissioned troops had not seen action.

After seeing the performance of the British cavalry during the New York Campaign, General George Washington realized his army needed horses of their own. Writing to Congress in late 1776, “From the Experience I have had in this Campaign… I am Convinced there is no carrying on the War without them.”

What made up the Continental Cavalry?

In 1777, the cavalry's first year in action, there were four regiments of Light Dragoons.

The 1st Regiment of Dragoons- from Virginia, also known as Bland's Light Horse. Their uniforms were originally the "classic" Continental coat: blue with red facings, but they then changed the standard to brown with green facings.

The 2nd Regiment, also known as the Connecticut Light Dragoons, Colonel Elisha Sheldon and Benjamin Tallmadge's force, mustered from Connecticut, hence the name. Their uniform was blue with buff facings.

The 3rd Regiment, aka Colonel Baylor's or Lady Washington's Light Horse, in honor of Martha Washington. Their uniform was white with blue facings (one of my favorite uniforms in the army.)

And the 4th Regiment, led by Colonel Stephen Moylan. His troops originally wore red! coats, and this lead to some incidents of friendly fire. At Washington's order, the regiment changed to green with red facings.

How does this relate to Turn: Benjamin Tallmadge and His Dragoons.

Although the show does not get into heavy detail about Benjamin Tallmadge's battle experience, we know what battles he was present at with his regiment.

1777 the cavalry's first years as professional troops in battle. Both had very... different outcomes, let's say. Both were also mentioned or briefly shown in season 2 of Turn, and my research focused on this.

During the Campaigns, a set of troops from each regiment of Dragoons was stationed with General Washington in Pennsylvania, led by Bland, Moylan, Baylor, Sheldon, and Tallmadge.

Benjamin Tallmadge and his soldiers were present at both the Battles of Brandywine and Germantown.

At Brandywine, Washington first used the dragoons for only scouting, not combat. But as the British went after his insecure right flank, he frantically sent units of soldiers and cavalry to prevent the British from getting to the road along and to Brandywine Creek. The cavalry also acted as messengers to officers during this battle, but insufficient preparation and speed led to delayed reports. The cavalry did lead a charge that allowed Washington to retreat, but the day was lost. Afterwards, the British marched into the Continental capital of Philadelphia.

After Brandywine, Washington needed another battle to try and take back Philadelphia. With a night march, he decided to attack the British near their camp in Germantown, Pennsylvania, a small village outside the city.

Washington had four columns, 2 made up of Continental forces and two of state militias. Just as at Brandywine, his right wing was commanded by Sullivan, and his left by Greene. The Dragoons were now under their newly commissioned commander, General Pulaski. Tallmadge stated in his memoirs that, “if every division of the army had performed its allotted part, it seems as if we must have succeeded.”

Unfortunately, this would not be the outcome at Germantown. At the beginning of the battle, the Continentals were winning. Part of the camp was captured. A heavy fog and rain set over the battlefield, and the British used this fog to their advantage. They retreated into a local country house and created a stalemate.

Benjamin Tallmadge and his dragoons were first stationed with Sullivan’s division, close upon “the scene of the action.” As the battle turned against the Continental forces and the troops became victim to enemy and friendly fire, Washington ordered him to use his 2nd Dragoons to block any further retreat, to no avail. Germantown was lost.

Germantown was the last official engagement of the Philadelphia campaign. But on June 28, 1778, the Continental Army and the Cavalry engaged the forces at the Battle of Monmouth in New Jersey. Due to proper military training thanks to the Inspector General Baron von Steuben and six months of waiting at Valley Forge, the army emerged as a proper fighting force and prevailed against the British. The victory allowed the Continentals to take back their capital and keep Washington in as Commander in Chief.

Monmouth is the shown in the finale of season 2- Gunpowder, Treason, and Plot- with Benjamin leading his dragoons into the battle.

After the 1777 campaigns, Tallmadge and his dragoons would stay up north, particularly New York, to patrol and engage the enemy in raids. They also participated in the Battles of Stony Point and Fort St. George, which were shown in seasons 3 and 4 of Turn.

Sources (and further reading):

Memoir of Col. Benjamin Tallmadge : Tallmadge, Benjamin, 1754-1835 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive

Brandywine: A Military History of the Battle that Lost Philadelphia but Saved America, September 11, 1777 by Michael C. Harris, Paperback | Barnes & Noble® (barnesandnoble.com)

Germantown: A Military History of the Battle for Philadelphia, October 4, 1777 by Michael C. Harris, Hardcover | Barnes & Noble® (barnesandnoble.com)

Cavalry of the American Revolution - Jim Piecuch - Westholme Publishing

#oh my GOD#i went insane#i went crazy#i'm so so sorry#i just really really like dragoons.#turn week 2023#turn: washington's spies#benjamin tallmadge#military history#american revolution#the Philadelphia campaign#saber & shortgun#I hope I got everything right. oh my god. I’m sorry.#long post

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

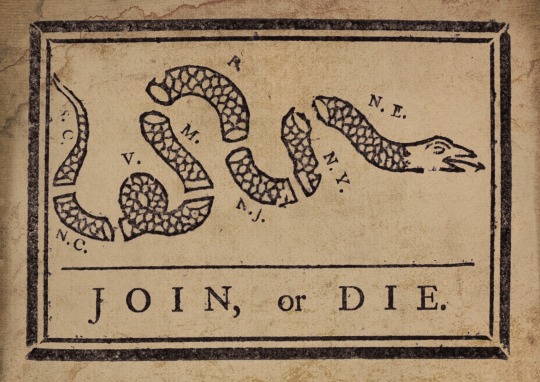

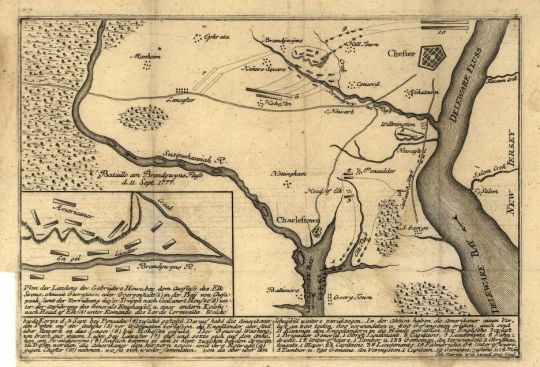

British "masters of the field" : The disaster at Brandywine

Illustration of the Battle of Brandywine, drawn by cartographer, engraver and illustrator Johann Martin Will (1727-1806) in 1777. Image is courtesy of the Library of Congress.

This post is reprinted from Academia.edu and my History Hermann WordPress blog. It was originally written in September 2016, one day after the anniversary of the battle, when I was a fellow at the Maryland State Archives for the Finding the Maryland 400 project. Enjoy!

On the night of September 10, 1777, many of the soldiers and commanding officers of the Continental Army sat around their campfires and listened to an ominous sermon that would predict the events of the following day. Chaplain Jeremias (or Joab) Trout declared that God was on their side and that

“we have met this evening perhaps for the last time…alike we have endured the cold and hunger, the contumely of the internal foe and the courage of foreign oppression…the sunlight…tomorrow…will glimmer on scenes of blood…Tomorrow morning we will go forth to battle…Many of us may fall tomorrow.” [1]

The following day, the Continentals would be badly defeated by the British and “scenes of blood” would indeed appear on the ground near Brandywine Creek.

In the previous month, a British flotilla consisting of 28 ships, loaded with over 12,000 troops, had sailed up the Chesapeake Bay. [2] They disembarked at the Head of Elk (now Elkton, Maryland) in July, under the command of Sir William Howe, and had one objective: to attack the American capital of Philadelphia. [3] Howe had planned to form a united front with John Burgoyne, but bad communication made this impossible. [4] At the same time, Burgoyne was preoccupied with fighting the Continental Army in Saratoga, where he ultimately surrendered later in the fall. With Howe’s redcoats, light dragoons, grenadiers, and artillerymen were Hessian soldiers fighting for the Crown. [5]

Opposing these forces were two sections of the Continental Army. The first was the main body of Continentals led by George Washington, consisting of light infantry, artillery, ordinary foot-soldiers, and militia from Pennsylvania and Maryland. The second was the Continental right wing commanded by John Sullivan, which consisted of infantry from New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Virginia, and Maryland. The latter was led by William Smallwood and included the First Maryland Regiment. Other Marylanders who participated in the battle included Walter Brooke Cox, Joseph Marbury, Daniel Rankins, Samuel Hamilton, John Toomy, John Brady, and Francis Reveley. While the British were nearby, the 15,000-man Continental Army fortified itself at Chadd’s Ford, sitting on Brandywine Creek in order to defend Philadelphia from British attack. [6]

A map by Johann Martin Will in early 1777, in the same set as the illustration of the battle at the beginning of this post, which shows British and Continental troop movements during the Battle of Brandywine.

The morning of September 11 was warm, still, and quiet in the Continental Army camp on the green and sloping area behind Brandywine Creek. [7] Civilians from surrounding towns who were favoring the Crown, the revolutionary cause, or were neutral watched the events that were about to unfold. [8]

Suddenly, at 8:00, the British, on the other side of the creek, began to bombard the Continental positions facing the creek complimented by Hessians firing their muskets. [9] However, these attacks were never meant as a direct assault on Continental lines. [10] Instead, the British wanted to cross the creek, which had few bridges, including one unguarded bridge called Jeffries’ Ford on Great Valley Road. As Howe engaged in a flanking maneuver, which he had used at the Battle of Brooklyn, the Marylanders would again find themselves on the front lines.

As the British continued their diversionary frontal attack on the Continental lines, thousands of them moved across the unguarded bridge that carried Great Valley Road over Brandywine Creek. Washington received reports about this British movement throughout the day but since these messages were inconsistent, he did not act on them until later. [11] At that point, he sent Sullivan’s wing, including Marylanders, to push back the advancing British flank. [12]

These Marylanders encountered seasoned Hessian troops who, when joined by British guards and grenadiers, attacked the Marylanders. Due to the precise and constant fire from Hessians and a British infantry charge with bayonets, the Marylanders fled in panic. [13] Lieutenant William Beatty of the Second Maryland Regiment, who would perish in the Battle of Hobkirk’s Hill, recounted this attack:

“…[in] the Middle of this Afternoon…a strong Body of the Enemy had Cross’d above our Army and were in full march to out-flank us; this Obliged our Right wing to Change their front…before this could be fully [executed]…the Enemy Appeared and made a very Brisk Attack which put the whole of our Right Wing to flight…this was not done without some Considerable loss on their side, as of the Right wing behaved Gallantly…the Attack was made on the Right, the British…made the fire…on all Quarters.” [14]

As a Marylanders endured a “severe cannonade” from the British, the main body of the Continental Army was in trouble. [15] Joseph Armstrong of Pennsylvania, a private in a Pennsylvania militia unit, described retreating after the British had crossed Brandywine Creek, and moved back even further, at 5:00, for eight or nine miles, with the British in hot pursuit. [16]

Despite the “heavy and well supported fire of small arms and artillery,” the Continentals could not stop the British and Hessian troops, who ultimately pushed the Americans into the nearby woods. [17] The British soldiers, exhausted and wearing wool, were able to push back the Continentals at 5:30 on that hot day. [18] As Washington would admit in his apologetic letter to the President of the Continental Congress, John Hancock, “…in this days engagement we have been obliged to leave the enemy masters of the field.” [19]

As the smoke cleared, the carnage was evident. Numerous Continentals were wounded, along with French military men such as the Marquis de Lafayette. [20] Despite Washington’s claim that “our loss of men is not…very considerable…[and] much less than the enemys,” about 200-300 were killed and 400 taken prisoner. [21] This would confirm Lieutenant Beatty’s claim that Continental losses included eight artillery pieces, “500 men killed, wounded and prisoners.” [22] In contrast, on the British side, fewer than a hundred were killed while as many as 500 were wounded. [23] Beatty’s assessment was that the British loss was “considerable” due to a “great deal of very heavy firing.” [24] Still, as victors, the British slept on the battlefield that night.

Not long after, the British engaged in a feint attack to draw away the Continental Army from Philadelphia and marched into the city without firing a shot, occupying it for the next ten months. [25] In the meantime, Congress fled to York, Pennsylvania, where it stayed until Philadelphia could be re-occupied in late June 1778.

In the months after the battle, the Continental Army chose who would be punished for the defeat. This went beyond John Adams’s response to the news of the battle: “…Is Philadelphia to be lost? If lost, is the cause lost? No–The cause is not lost but may be hurt.” [26] While Washington accepted no blame for the defeat, others were court-martialed. [27]

One man was strongly accused for the defeat: John Sullivan. While some, such as Charles Pickney, praised Sullivan for his “calmness and bravery” during the battle, a sentiment that numerous Maryland officers agreed with, others disagreed. [28] A member of Congress from North Carolina, Thomas Burke, claimed that Sullivan engaged in “evil conduct” leading to misfortune, and that Sullivan was “void of judgment and foresight.” [29] He said this as he attempted to remove Sullivan from his commanding position. Since Sullivan’s division mostly fled the battleground, even as some resisted British advances, and former Quaker Nathaniel Greene led a slow retreat, the blame of Sullivan is not a surprise. [30] Burke’s effort did not succeed since Maryland officers and soldiers admired Sullivan for his aggressive actions and bravery, winning him support. [31]

Another officer accused of misdeeds was a Marylander named William Courts, a veteran of the Battle of Brooklyn. He was accused of “cowardice at the Battle of Brandywine” and for talking to Major Peter Adams of the 7th Maryland Regiment with “impertinent, and abusive language” when Adams questioned Courts’ battlefield conduct. [32] Courts was ultimately acquitted, though he left the Army shortly afterwards. However, his case indicates that the Continental Army was looking for scapegoats for the defeat.

The rest of the remaining Continental Army marched off in the cover of darkness, preventing a battle the following day. They camped at Chester, on the other side of the Schuylkill River, where they stayed throughout late September. [33] Twenty-four days after the battle on the Brandywine, the Continental Army attacked the British camp at Germantown but foggy conditions led to friendly fire, annulling any chance for victory. [34] While it was a defeat, the Battle of Germantown served the revolutionary cause by raising hopes for the United States in the minds of European nobility. [35] It may have also convinced Howe to resign from the British Army, as commander of British forces in North America, later that month.

In the following months, the Continental Army continued to fight around Philadelphia and New Jersey. After the battle at Germantown, the British laid siege to Fort Mifflin on Mud Island for over a month. They also engaged in an intensified siege on Fort Mercer at Red Bank, leading to its surrender in late October. In an attempt to assist Continental forces, a detachment of Maryland volunteers under Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Smith were sent to fight in the battle at Fort Mifflin. [36] By November, the Continentals abandoned Fort Mifflin and retired to Valley Forge. Still, this hard-fought defense of the Fort denied the British use of the Delaware River, foiling their plans to further defeat Continental forces.

As the war went on, the First Maryland Regiment would fight in the northern colonies until 1780 in battles at Monmouth (1778) and Stony Point (1779) before moving to the Southern states as part of Greene’s southern campaign. [37] They would come face-to-face with formidable British forces again in battles at Camden (1780), Cowpens (1781), Guilford Courthouse (1781), and Eutaw Springs (1781). In the end, what the Scottish economist Adam Smith wrote in 1776 held true in the Battle of Brandywine and until the end of the war: that Americans would not voluntarily agree with British imperial control and would die to free themselves from such control. [38]

– Burkely Hermann, Maryland Society of the Sons of American Revolution Research Fellow, 2016.

Notes

[1] Collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Vol. 1 (Merrehew & Thompson, 1853), 70-72; Lydia Minturn Post, Personal Recollections of the American Revolution: A Private Journal (ed. Sidney Barclay, New York: Rudd & Carleton, 1859), 207-218; Virginia Biography, Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography Vol. V (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1915), 658. Courtesy of Ancestry.com; George F. Scheer, and Hugh F. Rankin, Rebels and Redcoats: The American Revolution Through the Eyes of Those who Fought and Lived It (New York: De Capo Press, 1957, reprint in 1987), 234. Trout, who was also a Reverend, would not survive the battle. While some records reprint his name as “Joab Traut,” other sources indicate that his first name was actually Jeremias and that his last name is sometimes spelled Trout.

[2] Andrew O’Shaughnessy, The Men Who Lost America: British Command During the Revolutionary War and the Preservation of the Empire (London: One World Publications, 2013), 254; Ferling, 177; Letters from Gen. George Washington, Vol. 5, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_344144_0001, item number 152, p. 87; “A Further Extract from the Examination of Joseph Galloway, Esq; by a Committee of the British House of Commons,” Maryland Journal, December 7, 1779, Baltimore, Vol. VI, issue 324, page 1.

[3] Washington thrown back at Brandywine, Chronicle of America (ed. Daniel Clifton, Mount Kisco, NY: Chronicle Publications, 1988), 163; “The Examination of Joseph Galloway, Esq; before the House of Commons,” Maryland Journal, November 23, 1779, Baltimore, Vol. VI, issue 322, page 1. Joseph Galloway, a former member of the Contintental Congress who later became favorable to the British Crown, claimed that inhabitants supplied the British on the way to Brandywine.

[4] Stanley Weintraub, Iron Tears: America’s Battle for Freedom, Britain’s Quagmire: 1775-1783 (New York: Free Press, 2005), 115.

[5] Bethany Collins, “8 Fast Facts About Hessians,” Journal of the American Revolution, August 19, 2014. Accessed August 31, 2016. They were called Hessians since many of them came from the German state of Hesse-Kassel, and many of them were led by Baron Wilhelm Von Knyphausen.

[6] Chronicle of America, 163; Letters from Gen. George Washington, Vol. 5, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_344144_0001, item number 152, p. 33. Courtesy of Fold3.com; Letters from Gen. George Washington, Vol. 5, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_344144_0001, item number 152, p. 37. Courtesy of Fold3.com; Letters from Gen. George Washington, Vol. 5, Papers of the Continental Congress, National Archives, NARA M247, Record Group 360, roll pcc_344144_0001, item number 152, p. 41. Courtesy of Fold3.com; The Annual Register or a View of the History, Politics, and Literature, for the Year 1777 (4th Edition, London: J. Dosley, 1794, 127-8; Mark Andrew Tacyn, “’To the End:’ The First Maryland Regiment and the American Revolution” (PhD diss., University of Maryland College Park, 1999), 137; The Winning of Independence, 1777-1783, American Military History (Washington D.C.: Center for Military History, 1989), 72-73.