#harper's weekly

Text

Odin, the Northern God of War by Valentine Cameron Prinsep

#odin#wotan#art#valentine cameron prinsep#norse mythology#old norse#norse#northern#europe#european#mythology#mythological#gods#war#northern europe#germanic#harper's weekly

590 notes

·

View notes

Text

Promenade Concert on New Year's Eve at the Produce Exchange, New York, Thure de Thulstrup, 1887

#New Year's Eve#art#art history#Thure de Thulstrup#engraving#illustration#Gilded Age#Americana#American art#19th century art#Harper's Weekly

218 notes

·

View notes

Text

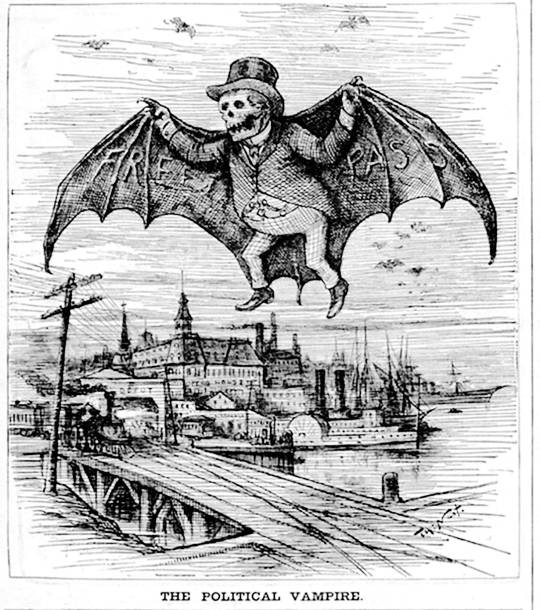

"The Political Vampire" Thomas Nast, Harper's Weekly, April 4, 1885 - zontar page on Facebook.

#politics#vampire#vampires#vampirecore#harper's weekly#19th century art#skulls#skeletons#horror art#bat#bats#batwings#gothic aesthetic

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

source: @artistsanimals (How Artists See Animals)

Title: The Crowning Insult to Him Who Occupies The Presidential Chair

Artist: Thomas Nast (American)

Date: May 13, 1876

Publisher: Harper’s Weekly Medium: Wood engraving

Source: Bates Museum

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harper's Weekly, March 16, 1907

Also for the record, it seems this is my 5000th post in this blog.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

A newspaper clipping from Harper's Weekly. Jefferson Davis is portrayed with deathly eyes, reaping plants with skulls on them with a sickle, circa 1861. Illustration by unknown artist.

#us civil war#death#jefferson davis#fuck jefferson davis#fuck the confederacy#harper's weekly#illustrations

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 1869 solar eclipse gained widespread news coverage, including this full page article in Harper's Weekly. The newspaper reproduced some of the earliest photographs taken of an eclipse for its readers; much safer than observing with the naked eye!

Astronomers of the day set up solar telescopes to study the rare phenomenon for clues about our solar system, including whether the sun's corona consisted of a gaseous atmosphere like the Earth's, and whether or not another planet existed between Mercury and the sun.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

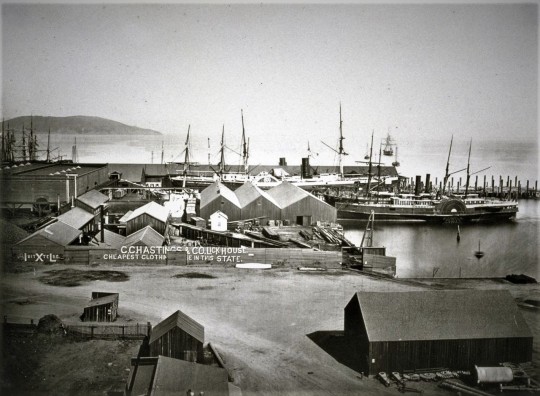

“San Francisco – P.M.S.S. Co.’s Wharf- Off for China and Japan” c. 1874. Illustrator unknown (from the collection of the National Parks Gallery).

Ships, Sheds and Wharves: Chinese and the Pacific Mail Steamship Co.

The earliest history of the Chinese in America remains intertwined with the Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s sheds on San Francisco’s wharf and the broader narrative of maritime transportation, immigration, and economic development during the 19th century in California. Founded in 1848 as a response to the California Gold Rush, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company (“PMSSC”) aimed to carry US mail on the Pacific leg of a transcontinental route from the east coast of the US to San Francisco on the west coast via Panama.

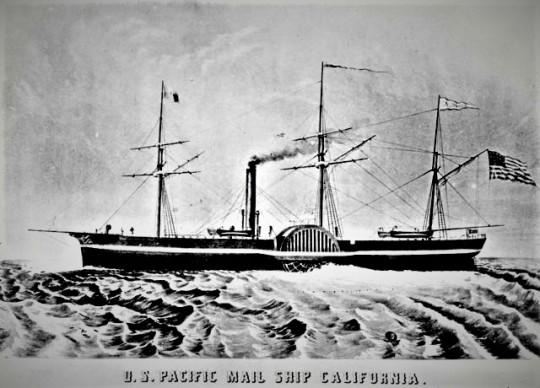

Illustration of the steamship SS California, the first ship of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. Only a few passengers were on board when the ship left New York on October 6, 1848. By the time the ship reached its stop on the Panama’s Pacific coast, word had spread of the great new find of gold in California. Over 700 people tried to get passage on the ship in that harbor. The Pacific Mail agent managed to cram 365 people aboard the ship before it set sail for California. The ship and passengers reached San Francisco on February 28, 1849, where all but one member of the crew deserted the ship for the goldfields. The ship was lost in a wreck off the Peruvian coast in 1894. (Illustrator unknown, from the collection of the US National Postal Museum)

The discovery of gold in the Sierra Nevada in 1849 produced a massive influx of people to California

from all over the world, including China. According to historian Thomas W. Chinn, “Hong Kong was the general rendezvous for departure to California. The emigrants usually stayed at dormitories provided by the passage brokers or at friends' and relatives' homes until the day of embarkation. The earliest ships between China and California were sailing vessels, some of which were owned by Chinese. . . . However, most of the ships in the early days bringing Chinese immigrants were American or British owned. At the time the shipping of Chinese to California was a very profitable business.”

The voyage in sailing vessels across the Pacific varied from 45 days to more than three months. Chinese passengers typically spent most of the voyage below decks in the overcrowded steerage. Conditions aboard the ships varied with the ship and shipmaster. In March 1852, 450 Chinese arrived in the American ship Robert Browne bound for San Francisco objected to the captain's order to cut off their queues as a hygienic measure. They rebelled, killed the captain and captured the ship. According to Chinn, “health conditions on the bark Libertad were so bad that when she sailed into San Francisco harbor in 1854, one hundred out of her five hundred Chinese passengers and the captain had died during the voyage from Hong Kong.”

In 1866, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company (“PMSSC”) entered the cargo and passenger trade to and from the Orient. As the sole federal contract-carrier for US mail, the PMSSC became a key mover of goods and people and a key player in the growth of San Francisco, California.

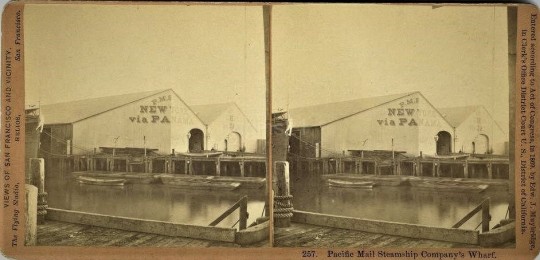

“257. Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s Wharf” c. 1869 -1871. Photo and stereoview by Eadweard J. Muybridge (from a private collection). The Pacific Mail’s wharf at the foot of Brannan Street in San Francisco at the approximate location of its old Pier 36. This was the first waterside view of the city for virtually every Chinese immigrant making landfall in San Francisco.

For the first six decades of the Chinese diaspora to the US, the sheds provided the first experience for every Chinese immigrant on California soil.

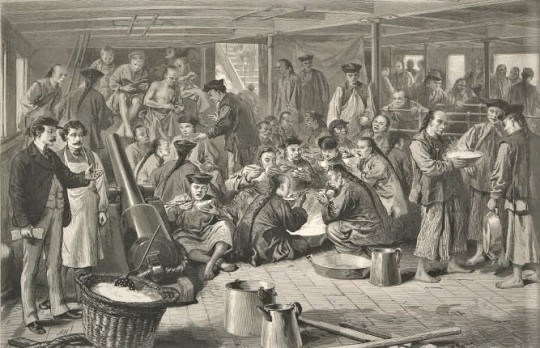

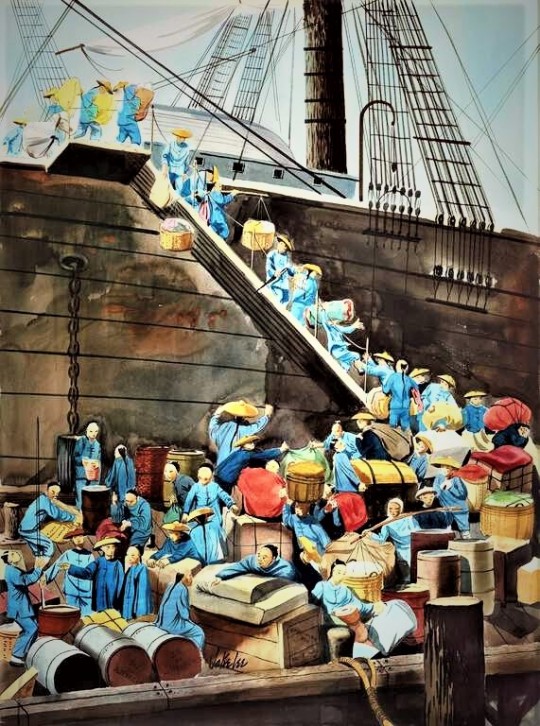

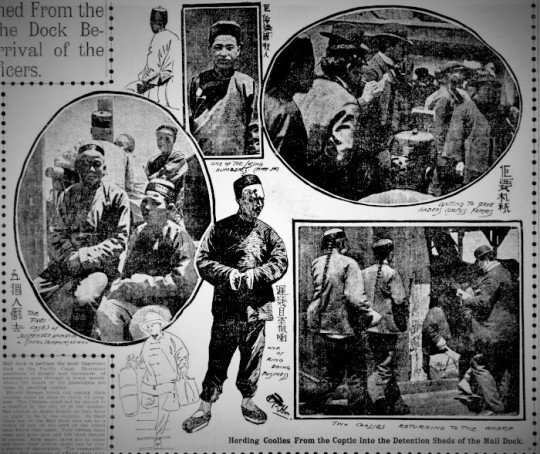

“Chinese Emigration to America,” no date. Illustrator unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library). This illustration shows life aboard a Pacific Mail Steamship Co. ship making the passage from China to San Francisco.

Amidst the Gold Rush and burgeoning industries like mining, agriculture, and construction, Chinese immigrants from southern China flocked to California. The PMSSC’s sheds, located along San Francisco’s waterfront, played a crucial role in handling cargo, passengers, and immigrants who arrived via steamships. Serving as pivotal infrastructure, they provided storage space for goods, customs processing areas, and waiting areas for passengers.

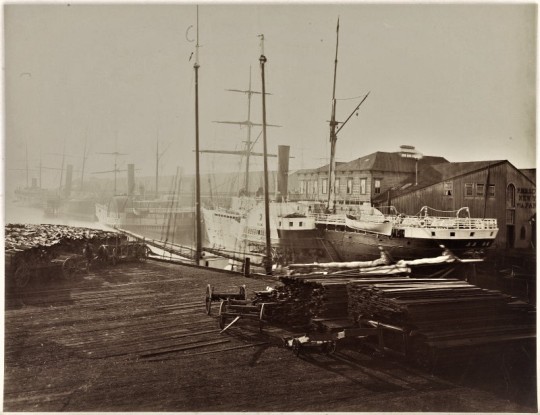

Pacific Mail Steamship Co. dock, c. 1864- 1872. Photograph by Carlton Watkins, probably derived from Watkins Mammoth Plate CEW 611. (from a private collection, the Roy D. Graves Pictorial Collection, Bancroft Library; and the San Francisco National Maritime Museum). In this elevated view east from Rincon Hill to the Pacific Mail dock, sidewheel steamer vessels identified by the SF National Maritime Museum as the SS Colorado (built in 1865 and scrapped in 1879), the steamer SS Senator at right (1865-1882), and various sailing ships are seen with Yerba Buena Island in the background. The Oriental Warehouse (built 1867 and still standing at 650 Delancey Street) is at left. The opensfhistory.org site identifies the three-part wooden structure at center as the Occidental Warehouse, used for grain storage, with blacksmith and boiler shops to the left. Ads for C.C. Hastings & Co. Clothing at Lick House can be seen on the fence.

Even as the Gold Rush waned, the PMSSC initiated in 1867 the first regularly scheduled trans-Pacific steamship service, connecting San Francisco with Hong Kong, Yokohama, and later, Shanghai. This route facilitated an influx of Japanese and Chinese immigrants, enriching California’s cultural diversity.

Pacific Mail Steamship Co. docks, c. 1871. Photograph by Carleton Watkins (from a private collection).

“Disembarking.” Painting by Jake Lee (from the collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America). In this watercolor, one among a suite of paintings commissioned by Johnny Kan for his then-new Kan’s Restaurant on San Francisco’s Grant Avenue in Chinatown, artist Jake Lee depicted a stylized unloading of mostly male passengers at the Pacific Mail Steamship Co. wharf in San Francisco.

When a ship dropped anchor at the dock in San Francisco, the emigrants finally set foot on American soil. A journalist for the Atlantic Monthly in 1869 described the debarkation of 1,272 Chinese as follows:

"… a living stream of the blue coated men of Asia, bearing long bamboo poles across their shoulders, from which depend packages of bedding, marring, clothing, and things of which we know neither the names nor the uses, pours down the plank…. They appear to be of an average age of twenty-five years… and though somewhat less in stature than Caucasians, healthy, active and able bodied to a man. As they come down upon the wharf, they separate into messes or gangs of ten, twenty, or thirty each, being recognized through some to us incomprehensible free-masonry system of signs by the agents of the Six Companies as they come, are assigned places on the long broad shedded wharf [to await inspection by the customs officers]."

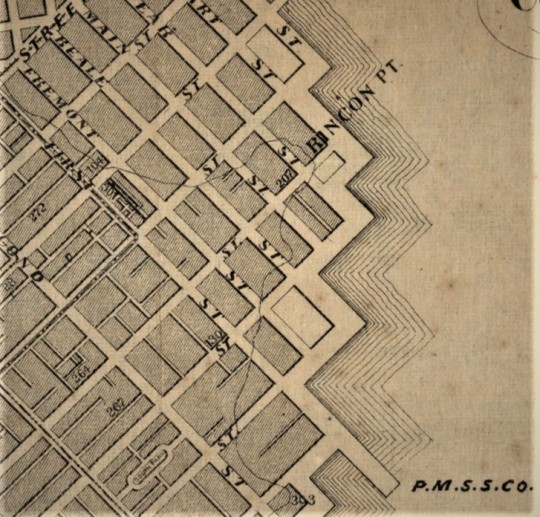

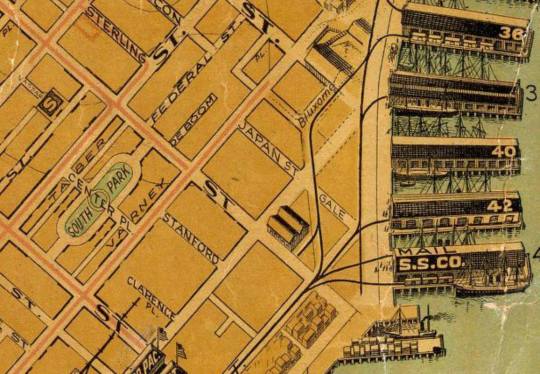

A detail from the "Bancroft's Official Guide Map of San Francisco" of 1873. The lower right corner of the image locates the Pacific Mail Steamship Co. pier at the foot of First Street (at Townsend) running in a southeasterly direction. According to local historian Garold Haynes, "that was before the seawall realignment of the waterfront in the late 1870s."

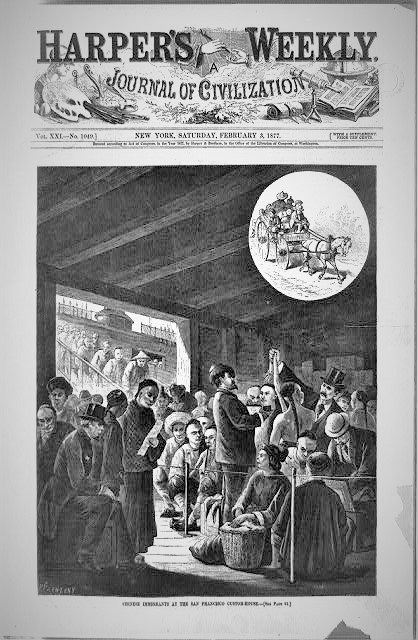

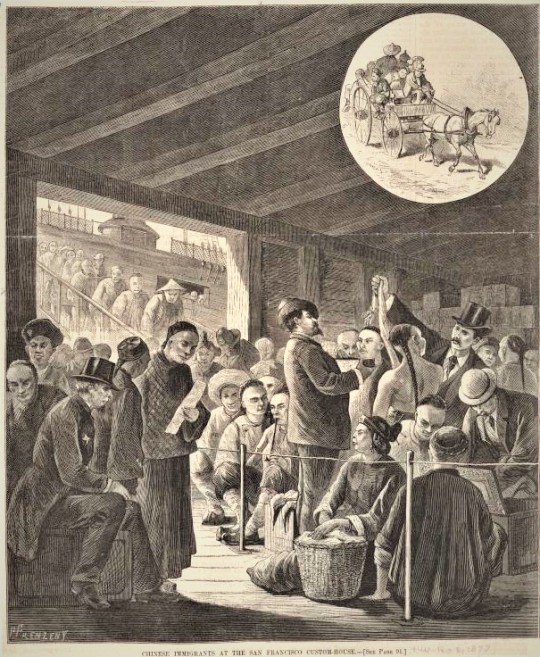

“Chinese Immigrants by The San Francisco Custom House” Harper’s Weekly, February 1877. Illustration by artist Paul Frenzeny (from the collection of the Library of Congress). Chinese immigrants wait for processing in the Pacific Mail Steamship Co.’s sheds while more arrivals from China disembark from the gangway seen in the background.

For many of the immigrants arriving on Pacific Mail steamships, the sheds served as the initial point of contact with the United States. Additionally, the sheds served as immigration processing areas, where Chinese immigrants underwent inspections and screenings. The sheds were a crowded and unsanitary place. Immigrants were often forced to wait for days in the sheds before they could be processed. They were also subjected to medical examinations and interrogations by immigration officials.

As the Atlantic Monthly writer described in 1869 described after each group passed through customs, “. . .They are turned out of the gates and hurried away toward the Chinese quarters of the city hv the agents of the Six Companies. Some go in wagons, more on foot, and the streets leading up that way arc lined with them, running in 'Indian file' and carrying their luggage suspended from the ends of the bamboo poles slung across their shoulders . . .”

In a political cartoon (c. 1888, based on the reference to the Republican Party presidential ticket of 1888 in the upper left corner of the image), Chinese immigrants stream off ships onto the wharves of the Pacific Mail Steamship Co. and the Canadian Pacific Steamship Co. and directly into the factories of San Francisco Chinatown and beyond. Illustrator unknown (from the collection of the Bancroft Library).

"New Arrivals." Date, location, and photographer unknown. The wagon on which the Chinese are riding, presumably having come directly from the Pacific Mail Steamship Co. wharf to San Francisco Chinatown, appears very similar to the 1877 configuration seen in the upper right corner of the preceding Harper's Weekly illustration.

The surge in Chinese immigration led to anti-Chinese sentiments, as reported in the illustrated magazines of the era. The arrival was often violent, as hoodlum elements would sometimes throw stones, potatoes and mud at the new immigrants. After the arrival in Chinatown, the newcomers were temporarily billeted in the dormitories of the Chinese district associations (citing Rev. Augustus W. Loomis, “The Chinese Six Companies,” Overland Monthly, os. v. 1 (1868), pp. 111-117).

“Hoodlums” Pelting Chinese Emigrants On Their Arrival At San Francisco” c. 1870s. Illustrator unknown (from a private collection). A rough sketch of the Pacific Mail Steamship Co. sheds appears in the background.

In San Francisco, local efforts to stop Chinese immigrants moved beyond the sheds and onto the arriving ships, which often became the focal points for Chinese litigants in the local and federal courts.

For example, in August of 1874, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s vessel Japan arrived in San Francisco carrying around 90 Chinese women. The Commissioner of Immigration boarded the ship and conducted interviews with about 50 to 60 of these women. From his inquiries, he concluded that 22 of them had been brought to San Francisco for “immoral purposes,” as reported by the Daily Alta California on August 6, 1874. When the Pacific Mail Steamship Company refused to provide the necessary bonds, the Commissioner instructed the ship’s master to keep the 22 women on board.

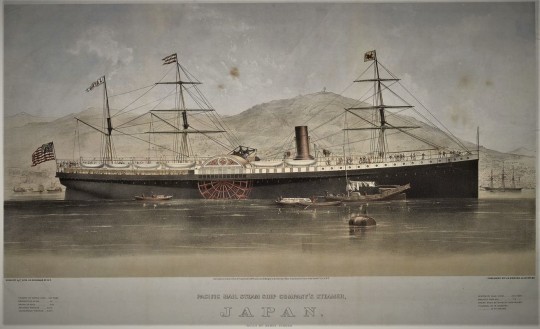

Pacific Mail Steam Ship Company’s Steamer, Japan, c. 1868. Print created by Endicott & Co. (New York, N.Y.), Menger, L. R., publisher (from the collection of The Huntington Library). Junks in the foreground, and, to the left in the background, Hong Kong’s Victoria Peak with semaphore at top appears in the background, center right. The SS Japan is flying the American flag from its stern, a Pacific Mail house-flag from the middle mast, and a pennant with the vessel’s name from the aft mast. A flag flying from the first mast appears to be a red dragon on a yellow field. Print includes vessel statistics and the name of the builder, Henry Steers.

Promptly, attorneys representing the detained women sought legal recourse by requesting a writ of habeas corpus from the state District Court in San Francisco. For two days, legal representatives from various parties engaged in debates over whether the Commissioner’s authority under the law was valid and whether the so-called “Chinese maidens” were indeed involved in prostitution. Reverend Mr. Gibson, who claimed expertise in this area, confidently asserted that Chinese prostitutes could be easily identified by their attire and behavior, likening the distinction to that between courtesans and respectable women in the city. He concluded that only half of the women were destined for prostitution. Ultimately, the District Court ruled that all the women should remain detained and ordered them to stay on the ship.

Shortly before the ship Japan was set to depart, the County Sheriff boarded and brought the 22 women ashore based on a writ of habeas corpus issued by the California Supreme Court. Two weeks later, Justice McKinstry, in a brief opinion on behalf of the court in Ex Parte Ah Fook, 49 Cal 402 (1874), affirmed the lower court’s decision, validating the Commissioner’s authority as a legitimate exercise of the state’s police power.

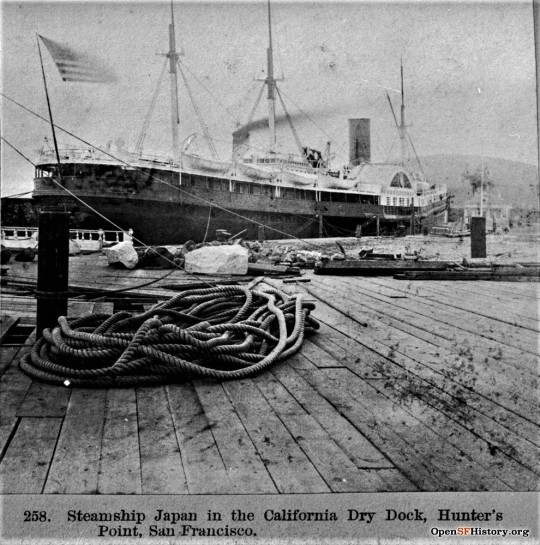

“258. Steamship Japan in California Dry Dock, Hunter’s Point, San Francisco”c. 1869. A side view of the steamship Japan of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company at the dry dock at Hunters Point. Photograph by Thomas Houseworth (from the Marilyn Blaisdell Collection). The ship would become the setting for a controversial habeas corpus case involving the entry of 22 Chinese women over the objections of state authorities in the case of Ex Parte Ah Fook, 49 Cal 402 (1874).

A third writ of habeas corpus presented the matter to the United States Circuit Court, presided over by Justice Stephen J. Field and Judge Ogden Hoffman. During the oral arguments, Justice Field made it clear that he wouldn’t dismiss constitutional arguments as easily as the state Supreme Court had, emphasizing the principle of equal treatment for citizens and non-citizens.

The Pacific Mail Steamship Co. derrick and coal yard in San Francisco, c. 1871. Photograph by Carleton Watkins (from the collection of the California Historical Society).

In the ruling, Justice Field discharged the petitioners, stating that California’s statute surpasses a state’s legitimate police power and violates the principle of “the right of self-defense.” He noted that the statute could exclude individuals who posed no immediate threat to the state. Judge Hoffman, in a concurring opinion, went further, suggesting that the states should have no control over immigration due to the exclusive nature of the commerce clause.

Although the Circuit Court decision released the Chinese women, while limiting the state’s power over Chinese entry, the Japan case reinvigorated California’s efforts to deter Chinese immigration. The influx of Chinese immigrants coupled with high unemployment in the late 1870s allowed Dennis Kearney of the Workingmen’s Party to target the Chinese as scapegoats. The “Chinese must go” movement gained traction, with both the Republican and Democratic parties adopting anti-Chinese stances.

The Pacific Mail Steamship Co.’s wharf in San Francisco. Photograph by Carleton Watkins (from the collection of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco).

During the San Francisco Riot of 1877, the sandlot mob attacked the wharves of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, because this shipping line represented the primary mode of transportation for America-bound Chinese immigrants headed to California. Although the steamships were not burned, the wharves were partially wrecked. Rioters also burned the lumber and hay yards adjacent to the Pacific Mail wharves.

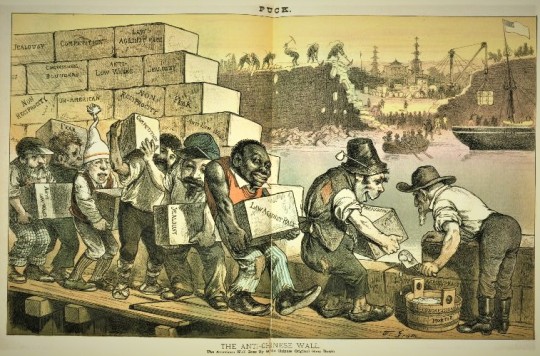

“The Anti-Chinese Wall – The American Wall Goes Up as the Chinese Original Goes Down.” Illustration by Friedrich Graetz in Puck of March 29, 1883 (v. 11, no. 264). The cartoon portrays a multi-ethnic coalition gathered on the wharf to halt Chinese immigration in the aftermath of the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in May 1882.

California was able to transfer its racial grievances and resentments to the national stage, culminating in the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. This marked a turning point in the history of Chinese immigration and had profound effects on the Chinese-American community. The Act severely restricted Chinese immigration to the United States.

The use the PMSSC’s sheds posed significant challenges to federal and state attempts to enforce the Exclusion Act (and its punitive extension in the Geary Act of 1892), against all Chinese, regardless of birth or immigration status.

As an article in the San Francisco Call of May 12, 1900, details, the chaotic scene at the Pacific Mall dock where Chinese immigrants disembarked from the ship Coptic was typical for that era. In the Coptic case, federal officials were observed allowing the landing of alleged "coolies" despite the spirit of the exclusion act, causing outrage. The detention shed, initially meant for temporary housing, had become a long-term residence for over 370 Chinese immigrants, generating substantial profit for the PMSSC. The maintenance of this facility posed several concerns, including violations of health regulations and potential disease outbreaks. The Call decried the authorities' negligence in enforcing the law and highlighted the role of a Chinese "ring" in facilitating fraudulent practices and illegal immigration. With multiple ships arriving with more immigrants, the newspaper called for investigation and reform.

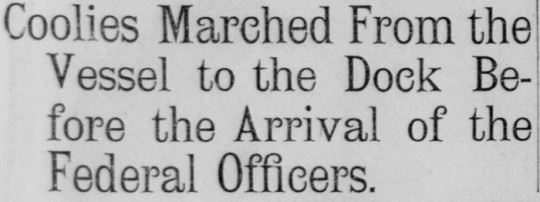

Headlines from the The Call of May 12, 1900, regarding the crowd of detained Chinese immigrants disembarked from the Pacific Mail ships Coptic and America Maru, the lack of security in the Pacific Mail sheds, and alleged immigration fraud.

Illustrations and photographs from the San Francisco Call of May 12, 1900, for its report about the crowd of detained Chinese immigrants disembarked from the Pacific Mail ships Coptic and America Maru, the lack of security in the Pacific Mail sheds, and alleged immigration fraud.

For Chinese and other immigrants and travelers from Asia, the transpacific journey, and even entering San Francisco Bay itself, posed hazards. The dangers were never more evident than in the case of the SS City of Rio de Janeiro. Launched in 1878, this steamship had been an essential component of the Pacific Mail Steamship Company's fleet. Its routes connected pivotal locations such as San Francisco, Honolulu, Yokohama, Japan, and Hong Kong, and the ship had played a role in America's expansion into the Far East and the Pacific in the aftermath of the Civil War and during the Spanish American War.

“A Thousand Boys in Blue S.S. Rio de Janeiro bound for Manila” copyright 1898. Published by M.H. Zahner (from the collection of the Robert Schwemmer Maritime Library). Built by John Roach & Son in 1878 at Chester, Pennsylvania, this vessel had served as a vital link between Asia and San Francisco, regularly transporting passengers and cargo. This stereograph shows its charter by the federal government for use as a military troop transport during the Spanish American War.

On the morning of February 22, 1901, the SS City of Rio de Janeiro commenced its approach to the Golden Gate and the entrance to San Francisco Bay. They had sailed with a crew that was mostly Chinese. History indicates that approximately 201 people were aboard the Rio de Janeiro, as follows: Cabin passengers 29; second cabin, 7; steerage (Chinese and Japanese), 68; white officers, 30; Chinese crewmen, 77. Of the Chinese crewmen, only two spoke English and Chinese. During the long voyage, the ship’s officer gave orders by using signs and signals. The ship’s equipment and lifeboat launching apparatus appeared to be in good working order and were capable of being lowered in less than five minutes.

Near the location of the future location of the Golden Gate Bridge, tragedy struck as the SS City of Rio de Janeiro. In the dense morning fog that obscured the surroundings, the ship collided with jagged rocks on the southern side of the strait, near Fort Point. The vessel’s non-watertight bulkheads led to rapid and unstoppable flooding. In a mere ten minutes, the SS City of Rio de Janeiro succumbed to the relentless forces of the sea.

The majority of the passengers, many of whom were Chinese and Japanese emigrants in steerage, were caught unaware in their cabins as the ship sank. The toll was staggering, with 128 lives lost out of the 210 souls on board. Of the 98 Asians reportedly on board the ill-fated ship, only 15 passengers were rescued, and 41 Chinese crewmen survived.

The SS City of Rio de Janeiro in Nagasaki, Japan, c. 1894. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park). The ill-fated ship, which transported passengers and cargo between Asia and San Francisco, sank seven years later after running into rocks near the present site of the Golden Gate Bridge. The never-salvaged shipwreck rests 287 feet underwater.

The sinking of the SS City of Rio de Janeiro represented the deadliest maritime disaster at the San Francisco Bay's entrance, forever etching its name in the annals of maritime history as the “Titanic of the Golden Gate,” drawing a sad parallel to another infamous shipwreck. Today, the case serves as a reminder of the unpredictable forces of nature and the inherent dangers of maritime travel to which thousands of Chinese immigrants and other Asian travelers subjected themselves to gain a better life in America.

"Chinese Passengers on Deck, 1900–15," enroute to Hawaii. Photographer unknown (from the collection of the Hawaii State Archives). Chinese passengers, some eating from rice bowls, crowd the deck of a steamship. After the Exclusion Acts, the numbers of Chinese voyaging to the US had decreased sharply.

Despite reduced immigration due to the passage of successive exclusion acts in 1882 and 1892, the PMSSC's sheds remained operational, their purpose shifting from off-loading immigrants to facilitating trade and commerce between the east and west coasts of the US.

The Pacific Mail Steamship shed on the San Francisco waterfront at the turn of the century. Photograph attributed to Arnold Genthe. Located at the former pier 36, where Brannan Street runs into the Embarcadero, the immigration station was moved to Angel Island in 1910. Pier 36, the last of the docks at Brannan was torn down in 2012. In just one year, 1852, 25,000 Chinese entered California for the Gold Rush and other opportunities. Chinese America began here.

The convergence of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads in Utah in 1869, had started the process of eroding the Pacific Mail's profitability on the Panama-to-San Francisco route over the ensuing decades, eventually leading to the sale or redirection of many of its ships to other routes.

The Pacific Mail Steamship Co. offices on the southeast corner of Market and First streets in downtown San Francisco, c. 1896. Photographer unknown (from a private collection).

The landscape changed drastically in 1906, when a devastating earthquake and subsequent fire struck San Francisco, including the PMSSC’s wharf facilities. Although destroyed during 1906 disaster, the PMSSC’s sheds were rebuilt shortly thereafter. The sheds continued to be used for detaining and interrogating Chinese immigrants until the opening of immigration station facilities on Angel Island in 1910 for the processing Chinese and other immigrants.

A detail from the August Chevalier Map of 1915. The PMSSC sheds were located on Pier 36 at the intersection of Brannan and First Street.

The legacy of the PMSSC’s sheds, intertwined with their role at the inception of Chinese immigration to California and the US, is deeply rooted in San Francisco's maritime and Chinese American history. Both the company's operations and the experiences of the first wave of the Chinese diaspora arriving on American shores by steamships will remain forever part of the socio-economic dynamics of 19th-century San Francisco and the American West.

“Chinese Immigrants by the San Francisco Custom House” c. 1877. Detail of the magazine cover illustration by artist Paul Frenzeny for the Harper’s Weekly (from the collection of the New York Public Library.

[updated 2023-10-17]

#Pacific Mail Steamship Co.#Pacific Mail sheds#Chinese immigration detention#Carleton Wtakins#Paul Frenzeny#Harper's Weekly#SS Japan#In re Ah Fook#Stephen Field#Eadweard Muybridge#Pier 36 San Francisco

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘Elizabeth Shippen Green, 1871-1954, Philadelphia, oil on artists board, published in color in "Harpers Weekly" 1911, Titled "Tapestries of Twilight" and again in Richard Le Gallienne's "Maker Of Rainbows and Fables" illustrating the story "The Rags of Queen Cophetua". labeled on the verso "The Rags of Queen Cophetua, after she would steel away by herself and enter that secret Gallery-", signed lower left Elizabeth Shippen Green. 23.8" high by 15.25" wide.’

#esg#elizabeth shippen green#oil on board#oil painting#painting#harper's weekly#magazine#magazine illustration#1911#1910s#tapestries of twilight#richard le gallienne#maker of rainbow and fables#illustration#the rags of queen cophetua#after she would steel away by herself and enter that secret gallery#secret gallery#queen cophetua#mandolin

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

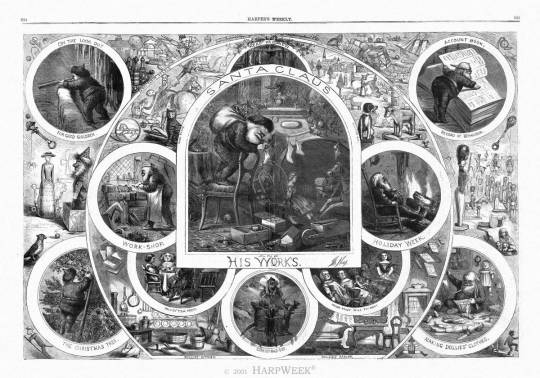

#santa#santa claus#father christmas#vintage christmas#vintage illustration#santa claus: his works#harper's weekly#black and white#vintage santa

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Continuing my trend of being late to talk about holidays, here's a little article from 1908 on April Fool's Day that I found interesting:

Link

"A little nonsense now and then

Is relished by the wisest men."

New favorite quote, we stan.

0 notes

Text

Bird's-eye View of Chicago as it was before the Great Fire, from Harper's Weekly NYC 1871 (via Library of Congress)

1 note

·

View note

Text

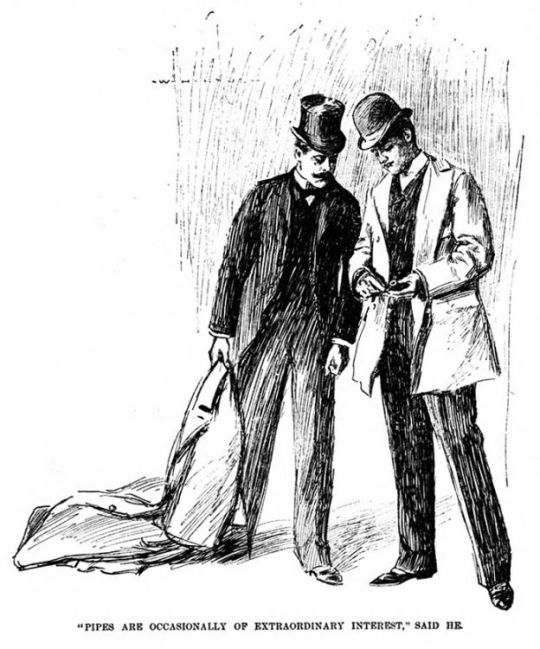

#Sherlock Holmes#Harper's Weekly#Victorian#illustration#black and white#art#The Adventure of the Yellow Face

0 notes

Text

kick bim and bling into ruins, re

...and always willing to chat

occasionally in the vicinity of our larger cities.

er, they very coolly take down Joss, kick bim and

bling into ruins, and but few of the best are re

over his puttering work, he

—

OCR cross (four) column misread, involving “The Traveling Tinker” and “Chinese Gods” at Harper’s Weekly (“A Journal of Civilization”) 14:726 (November 26, 1870) : 753 (Stanford copy)

same page (Michigan copy) at hathitrust

—

on the traveling tinker (entire) —

The itinerant tinker, a few years ago, was an important personage in the rural districts. He traveled from village to village, from farm-house to farm-house, and being generally a good-natured, oldish man, with a talent for conversation and telling stories, and always willing to chat over his puttering work, he was almost as welcome as the traveling peddler. The growth of villages, and the increasing cheapness of manufacture, have nearly driven him out of business, and he is now rarely met with except in districts remote from large towns. People have discovered that it is cheaper to throw away leaky pans and kettles, and buy new ones, than to have the old tinkered up. He is, however, to be met with occasionally in the vicinity of our larger cities. The illustration on this page [“drawn by John Bolles”] is a sketch from life in a New Jersey village near New York.

search results, inconsistent, subject to weather? solar storms? meander of the geomagnetic poles?

0 notes

Text

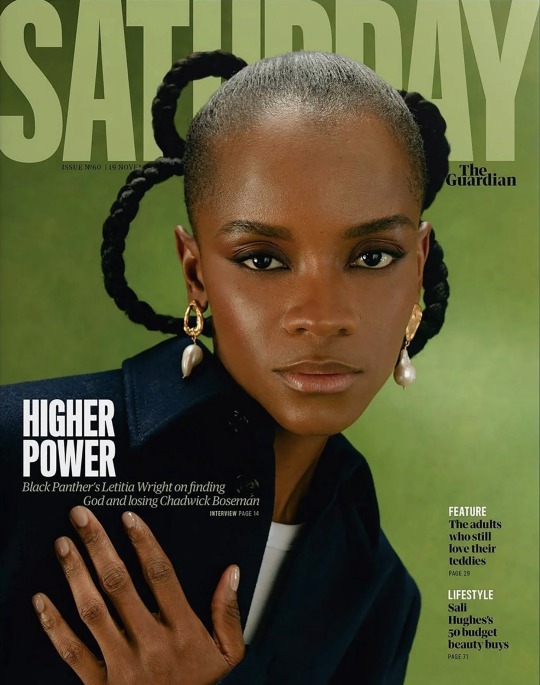

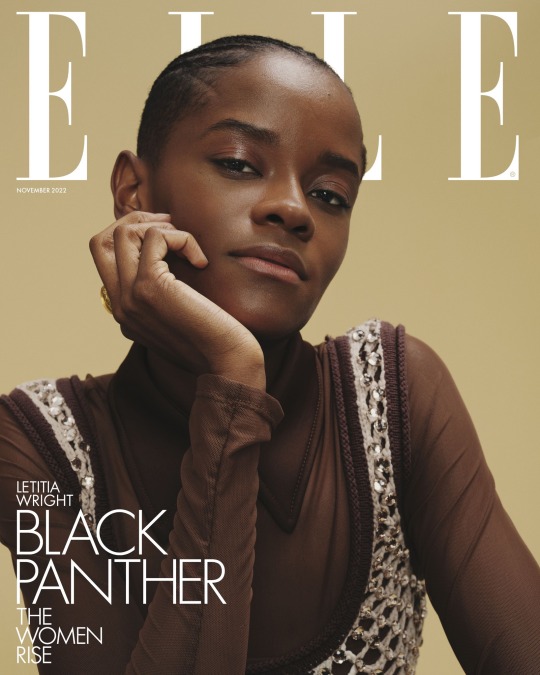

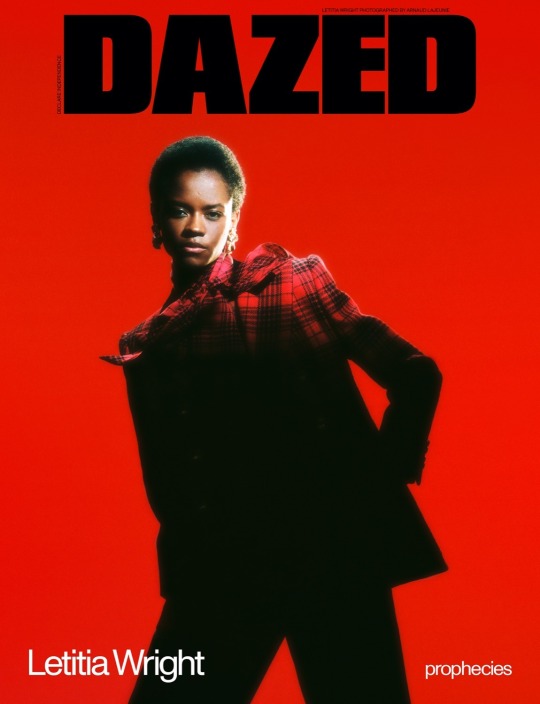

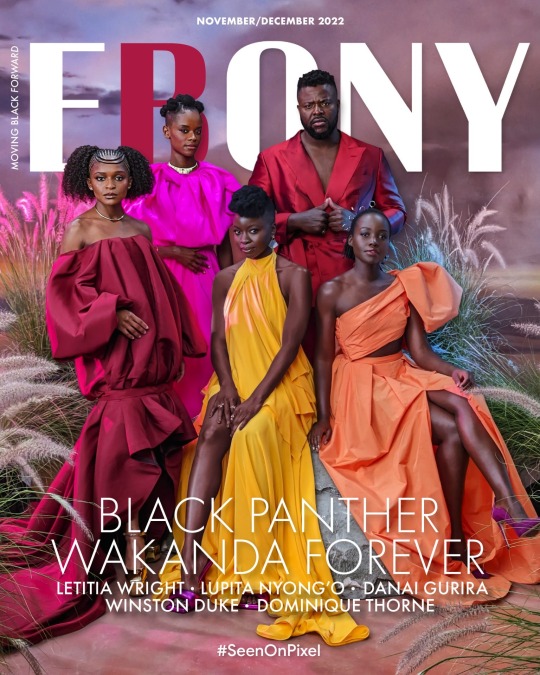

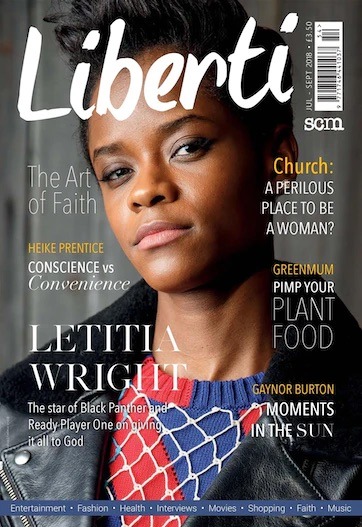

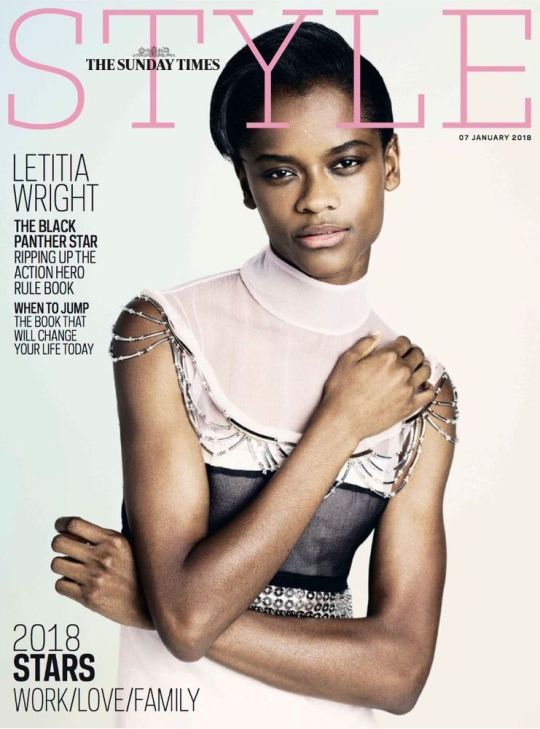

ʟᴇᴛɪᴛɪᴀ ᴡʀɪɢʜᴛ x ᴍᴀɢᴀᴢɪɴᴇ ᴄᴏᴠᴇʀs

ʙᴀᴢᴀᴀʀ | ᴛʜᴇ ʜᴏʟʟʏᴡᴏᴏᴅ ʀᴇᴘᴏʀᴛᴇʀ | sᴀᴛᴜʀᴅᴀʏ: ᴛʜᴇ ɢᴜᴀʀᴅɪᴀɴ | ᴇs | ᴇʟʟᴇ | ᴘᴏʀᴛᴇʀ | ᴡ | ᴅᴀᴢᴇᴅ | sᴄʜᴏ̈ɴ! | ᴠᴀʀɪᴇᴛʏ | ᴡᴏɴᴅᴇʀʟᴀɴᴅ | ᴇʙᴏɴʏ | ᴠᴏɢᴜᴇ: sɪɴɢᴀᴘᴏʀᴇ | ᴇssᴇɴᴄᴇ | ᴇɴᴛᴇʀᴛᴀɪɴᴍᴇɴᴛ ᴡᴇᴇᴋʟʏ | ᴇᴍᴘɪʀᴇ | ʟɪʙᴇʀᴛɪ | ᴜᴘsᴄᴀʟᴇ | sᴛʏʟᴇ | ᴍᴀɢɴɪғʏ

#this is literally her song#letitia wright#shuri#bpwf#black panther#the woman literally does it all!#the Saturday mag looks are 💯#ITS THE RANGE FOR ME#harper bazaar#ebony magazine#the hollywood reporter#the guardian#elle magazine#variety#entertainment weekly#vogue#prada ss23#fashion#lupita nyong'o#danai gurira#angela bassett#ryan coogler#dominque thorne

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

Weekly Press Briefing #66: September 24th - 30th

Welcome back to the Weekly Press Briefing, where we bring you highlights from The West Wing fandom each week, including new fics, ongoing challenges, and more! This briefing covers all things posted from September 24 - September 30, 2023! Did we miss something? Let us know; you can find our contact info at the bottom of this briefing!

Challenges/Prompts:

The following is a roundup of open challenges/prompts. Do you have a challenge or event you’d like us to promote? Be sure to get in touch with us! Contact info is at the bottom of this briefing.

@callixton hosted The West Wing Pride Week (@twwpride here on tumblr) September 17 - 23. More details here, and you can check out the AO3 collection here!

This Week in Canon:

Welcome back to This Week in Canon, where we revisit moments in The West Wing that occurred on these dates during the show’s run.

Season 1, Episode 2: Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc aired on September 29, 1999.

Season 4, Episode 1: 20 Hours in America Part I aired on September 25, 2002.

Season 4, Episode 2: 20 Hours in America Part II aired on September 25, 2002.

Season 5, Episode 1: 7A WF 83429 aired on September 24, 2003.

Season 7, Episode 1: The Ticket aired on September 25, 2005.

Photos/Videos:

Here’s what was posted from September 24 - September 30:

Bradley Whitford posted a photo of his wife Amy Landecker along with a sweet message for her birthday.

Marlee Matlin posted a photo of herself with her daughters in honor of National Daughters Day.

Marlee Matlin posted a photo of herself and her sister getting their hair done together over FaceTime.

Marlee Matlin posted photos of herself with her sons in honor of National Sons Day.

Marlee Matlin posted photos of herself out on the ice for an NHL game.

Rob Lowe posted a throwback photo of him swimming underwater in the ocean.

Donna Moss Daily: September 24 | September 25 | September 26 | September 27 | September 28 | September 29 | September 30

Daily Josh Lyman: September 24 | September 25 | September 26 | September 27 | September 28 | September 29 | September 30

No Context BWhit: September 24 | September 25 | September 26 | September 27 | September 28 | September 29 | September 30

@twwarchive: September 24 | September 25 | September 26 | September 27 | September 28 | September 29 | September 30

@bestofcjtoby: September 24

Editors’ Choice:

Because it premiered this week in 2005, we’re rounding up some of our favorite fics that take place during or after the events of The Ticket (Season 7, Episode 1).

I don't wanna miss you like this (come back... be here) by WitchyPrentiss | Rated G | Josh Lyman/Donna Moss | Complete | This starts as the part in the rom-com where everything feels like it won’t end up okay and some sad song is playing as the leads go about their lives without each other - but bare with me because every rom-com has a happy ending.

Post the ticket, pre the Al Smith dinner

Title: Come Back Be Here by Taylor Swift

As Swords Go by thefinestmuffins | Rated T | Josh Lyman/Donna Moss | Complete | After his disaster interview with Donna, Josh gets some advice from Leo and does his best to makes amends with the help of emotional vulnerability and Chinese takeout.

Post-Ep Fix-It for The Ticket

see right through me by itwasit | Rated T | Josh Lyman/Donna Moss | Complete | Lou shoves him into the room with her and he’s not prepared. He doesn’t have his folder full of her quotes to remind him of why he can’t miss her. He doesn’t have his memories prepared, in the front of his mind, of the specific ways her leaving hurt.

taylor swift song fic (josh's version) (the archer)

Spoiling for a Fight at Midnight by LizaCameron | Rated T | Josh Lyman/Donna Moss | Complete | Josh and Donna finally fight it out, post The Ticket

You're Gonna Die Bloody (and All You Can Do is Choose Where) by onekisstotakewithme for daylight_angel, miabicicletta, Luppiters, hondagirll | Rated T | Danny Concannon/C.J. Cregg | Complete | The hearings will turn over every rock in her life, every email, every phone call – and of course they’ll see Danny’s name – but she can’t drag him down any further.

Chianti by TheBreakfastGenie | Rated G | Josh Lyman & Toby Ziegler, C. J. Cregg & Toby Ziegler,Josh Lyman/Donna Moss, Danny Concannon/C. J. Cregg | Complete | The bag hits the ground with her, and the bottle breaks, spilling dark wine all over the driveway.

He stares at the dark liquid spreading over the ground, staining the ice. It’s more purple than red, but it might as well be blood.

make

an honest stand by jazzjo | Rated G | C. J. Cregg/Kate Harper | Complete | Oliver Babish asks her, once, then again after a dizzying go-around, if she trusts Kate.

She does; she trusts Kate Harper with her life.

Please hold while we reblog with this week's fics!

#the west wing#tww#west wing#tww fandom#josh lyman#donna moss#tww fic#cj cregg#sam seaborn#toby ziegler#danny concannon#josh x donna#danny x cj#kate x cj#kate harper#will bailey#weekly press briefing

12 notes

·

View notes