#madame d'aulnoy

Text

In Heidi Ann Heiner's Cinderella Tales From Around The World, I've now read the variants from Germany, Belgium, and France.

*Of course the most famous German Cinderella story is Aschenputtel by the Brothers Grimm. If you don't know it from reading it, you probably know it from Into the Woods, and if you don't know it from there, you've probably heard of it in pop culture. Too many people mistakenly think it's the "original" version of Cinderella. But there are other German Cinderella stories too – all similar to the Grimms' version, but with differences here and there.

*In nearly every German version, and in both of the two Belgian versions the book features, the heroine gets her elegant gowns and shoes from a tree. It throws them down to her, or opens up to reveal them, after she either recites a rhyme underneath it or knocks on it.

**Some variants, like the Grimms', have the archetypal "father goes on a journey and asks for gift requests" plot line, and the heroine gets a hazel twig, which she plants on her mother's grave and which grows into a tree. But in other versions, the tree is seemingly a random one, which either a dove, a dwarf, or a mysterious old man or woman advises her to ask for finery.

**That said, there's one exception: a German version called Aschengrittel, where the heroine meets a dwarf who, like the fairies in some Italian versions, gives her a magic wand to grant her wishes.

*As in the Egyptian, Greek, and Italian versions, it varies whether the German versions have the heroine abused by a stepmother and stepsister(s) or by her own mother and sister(s), whether her father is alive or not, and whether the special event she attends is a royal ball/festival or a church service. In both of the two Belgian versions, the heroine's abusers are her own mother and sister(s).

*While in the Mediterranean versions, the heroine's future husband is always either a prince or (more rarely) a king, in the German versions he's occasionally a knight or a rich merchant instead.

*Other typical German and Belgian details are (a) the (step)mother forcing the heroine to sort lentils, seeds, or grain, usually by picking them out of the ashes, which is usually resolved by birds doing the job for her, (b) the prince (or king, or merchant) having the palace or church steps smeared with pitch so that the heroine loses her shoe, and (c) the notorious detail of the (step)sisters cutting off parts of their feet to make the shoe fit, which is revealed when either birds or a dog call out that there's blood in the shoe.

**One Greek version has the prince catch the heroine's shoe by having the church steps smeared with honey, but the Mediterranean Cinderellas usually lose their shoes either by accident or by choice, while in Germany and Belgium it's usually the prince's doing.

**The foot-cutting episode is clearly typical of German and Belgian versions, but the Grimms' other notorious detail, where the stepsisters' eyes are pecked out by doves at the end, isn't typical. The Grimms themselves added that grisly detail to give the story a more "moral" ending with the stepsisters appropriately punished.

*The Grimms' footnotes for their version are included in this book. They mention several other German variants, including two that continue after the heroine's marriage and have the stepmother and stepsister try to murder her, and one where the stepmother starts out as the heroine's childhood nurse and murders the girl's mother by pushing her out a window, then claims she committed suicide.

*The German, Belgian, and French Cinderellas aren't quite so cunning and unfazed as the Greek and Italian Cinderellas. Now we see more heroines who cry over their hardships, and/or who beg to be allowed to go to the ball/festival or church, and whose magical help is more given to them and less in their own control. One notable French exception to this pattern, though, is Madame d'Aulnoy's cunning and self-reliant Finette Cendron.

*France doesn't seem to have the same pattern of culturally-distinct oral versions of this tale that other countries do. Instead, the French examples in this book are nearly all literary versions, and each one is almost completely different from the others.

**Of course the most wildly famous and important French Cinderella is Charles Perrault's Cendrillon. This is the Cinderella we all know best, with the fairy godmother, the pumpkin coach, the magic only lasting until midnight, and the glass slipper.

**Published in the same year as Perrault's version was Madame d'Aulnoy's Finette Cendron. This is an interesting, much longer variation that starts out as a Hop o'My Thumb/Hansel and Gretel story, where three sisters are abandoned in the woods and nearly eaten by an ogre, only for the clever youngest, Finette, to outwit him, but then turns into a Cinderella story when the older sisters abuse Finette after they make the dead ogre's castle their home, but Finette follows them to a ball in finery she finds in a chest.

**Another French literary variant is The Black Cat, which starts out as a Cinderella tale, but then has the heroine be stranded on an island and give birth to a black cat son (long story), then turns into a Puss in Boots tale as the cat helps his mother. Yet another is The Blue Bull, where the heroine runs away from her stepmother with her only friend, a magical bull, only for the bull to be killed protecting her from lions, and which then becomes a Donkeyskin/All Kinds of Fur-type of story, where she becomes a servant at the prince's palace and gets her ballroom finery from the bull's grave.

*Perrault and d'Aulnoy's versions are the only two Cinderellas so far where the heroine has a fairy godmother. Yes, in some others there are fairies or mysterious old women who help her, but the concept of a fairy godmother seems to have French literary origins.

*These same two versions, Perrault's and d'Aulnoys are also where we first see strong emphasis on the heroine's virtue and kindness, even to her cruel (step)family. While some oral versions do have her forgive them in the end, these literary versions not only have her do that, but have her constantly be gracious and kind to them (Perrault) or save their lives even at great personal sacrifice (d'Aulnoy).

*Now that I've read Finette Cendron, I can see its slight influence on Massanet's opera Cendrillon. In Finette Cendron, instead of Perrault's choice to have the slipper taken from house to house, all the ladies are invited to the palace to try it on, and Finette's fairy godmother sends her a horse to ride there – just like Cinderella's fairy godmother transports her to the slipper-fitting at the palace in the opera. Finette Cendron's Prince Cherí also falls deathly ill with love for the mystery girl, but is cured when he finds her. (A recurring theme in many different variants, which I forgot to mention when I covered the Mediterranean versions.) In the opera, this has its parallel when Prince Charming faints in despair over the seeming failure of the slipper-fitting, and before that when Cinderella herself becomes gravely ill because she thinks she'll never see her prince again.

@adarkrainbow, @ariel-seagull-wings, @themousefromfantasyland

#cinderella#fairy tale#variations#germany#belgium#france#the brothers grimm#charles perrault#madame d'aulnoy#cinderella tales from around the world#heidi ann heiner#tw: violence#tw: murder#tw: suicide mention

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

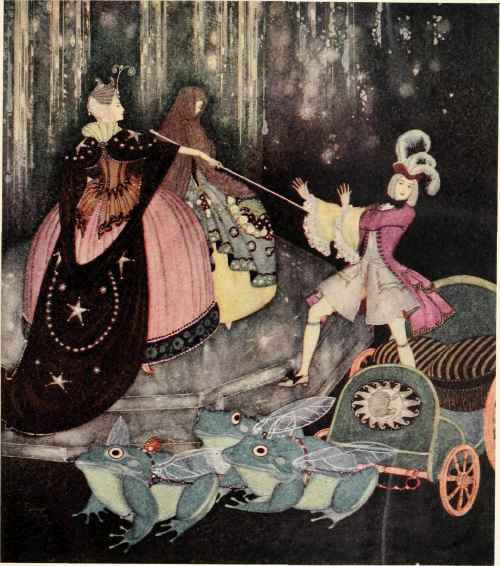

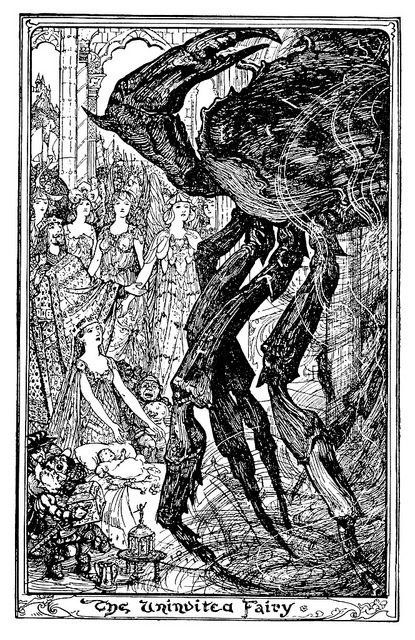

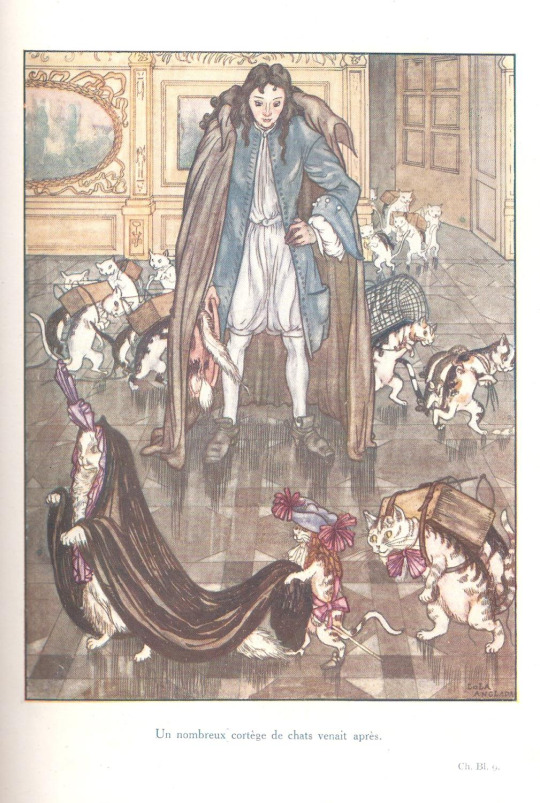

The Fairy of the Desert crashes Princess Toute-Belle's wedding.

Art by Walter Crane for The Yellow Dwarf by Madame d'Aulnoy.

#fairies#fairytales#madame d'aulnoy#walter crane#the fairy of the desert#and yes the turkeys breathe fire#that is a look and she is serving

77 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello there. First of all thank you for all the analysis and in depth look into fairy tales.

I stumbled upon a take that was utterly surprising to me about how fairy tales validate women through submissive beauty while the men are portrayed as active and violent and how fairy tales are tools to reinforce gender roles and patriarchy.

And I wonder how did we end up here? I seem to remember you talking about how a lot of fairy tales authors were women, but even in the Grimm brothers fairy tales the women are active, it's not only the men who go through trials.

Anyway I was wondering if you had any thoughts on this?

A most interesting, complex and yet simple question!

Do not be surprised by this take: it has been THE dominating take on fairytales until very recently. It was the big 20th century idea about fairytales - and in fact, it was one of the ideas heralded and massively shared by Jack Zipes in his famous book. This is also partially thanks to him that most Americans share this exact same view. Now we know, thanks to today's research, that this is not as true as people like to think and that this only applies to some fairytales - but the idea that fairytales can actually be subversive, can actually challenge an established society's codes, structure or hierarchy, is in truth fairly recent - or rather has only been accepted fairly recently.

A part of this is definitively Disney. There is no denying that the "Disney fairytale" marked forever popular culture's view of fairytales AND that as a result it inclined a lot of people to look at traditional fairytales under a certain angle. Remember - to make a Disney princess an active character, with the likes or their Rapunzel or Tiana, was seen during the movies' releases as a MASSIVE breakthrough for Disney.

That being said, to well answer this, I think a look at the French literary fairytales can be interesting. (Especially since... it is much more of my domain than the Grimm fairytales for example Xp)

Now Jack Zipes expressed this very theory by talking of Charles Perrault fairytales. In his book he clearly said that, through his stories, Perrault taught girls to be passive damsels waiting to be saved ; and boys to be active heroes. The typical "prince saving the damsel in distress ; knight rescuing the princess in the tower". And on a first, superficial, quick glance... Zipes is right - and many, MANY people read Perrault's fairytales as such.

Indeed, female protagonists of Perrault share a distinct passiveness and earn their happy ending through patience, pleasing people and looking good. Cinderella endures abuse without talking back, only has to look pretty for a prince thanks to an outside interference, and her marriage is what saves her - before she even forgives her wicked stepsisters! Sleeping Beauty spends half of her story sleeping before being saved by the arrival of a prince ; and then the second half she is the helpess victim of the ogress and only is helped by either the butler or the prince. The wife of Bluebeard cannot save herself, it is her brothers that save the day, while in Diamond and Toads the good girl is rewarded for just being nice and helping a poor woman, and it is again through a wedding she gains happiness. Many people also like to invoke the semi-fairytale Griselidis which is... a whole another topic to go into.

Meanwhile the male protagonists are "active", industrious heroes and vanquishers of evil. Puss in Boots is a trickster who hunts animals, actively runs around, and devours an ogre. Little Thumbling also puts together all sorts of plans, actively changes the crowns and nightcaps, steals away the ogre's boots, and once again runs around... The brothers of Bluebeard's protagonists are the big heroes that come in the end to murder the persecutor.

So far, it all seems right... And somewhat, yes, it is true. Because of the context, because of the society, culture and time these stories were written into. In 17th century upper-class France, women were only valuable if they were pretty, if they didn't cause trouble, if they could be good wives or good mothers ; men on the contrary were expected to be sportsmen, warriors, active members of their community or of the government... But as usual with Perrault, nothing is as simple as it is, since there is joke and satire hidden in his texts that many fail to see, and when we look a bit closer at all this, we see hidden behind the apparent dichotomy the traces of a more nuanced take.

Yes, Puss in Boots is an active male character... But the marquis de Carabas is just as passive as another Cinderella or Donkeyskin, as he literaly does NOTHING but look good, obey the cat and follow everybody around. "Puss in Boots" is Cinderella told through the eyes of the supernatural helper - the talking cat is the fairy godmother, who is the one that brings beautiful clothes and meeting with the royals and the seeds of a romance to his passive, useless master. In fact, the "morals" of both stories are eerily similar: Perrault jokes at the end of Cinderella that anything is possible as long as you have a powerful or well-placed godparent ; and Puss in Boots moral is also about how "If you can find the way, you can trick the system, and become a prince when you shouldn't AT ALL". Both stories aren't in the end about someone being rewarded for being pretty or enduring suffering - but simply about having enough hidden resources and trickery to use the very flaws of the system used upon you.

Again, let us take Cinderella. She endures her suffering, according to people, she does nothing for herself, the fairy godmother does everything, and her salvation comes from a prince marrying her... She is pointed out to be so naive she chats with her stepsisters as if everything was normal when she is at the ball. She proves to be the ultimate goody-two-shoes when she forgives her persecutors at the end... And yet, what does the moral point out? That openly forgiving your enemies is the best way to put them in your pocket... because as such they'll be indebted to you, and you forced them into depending on your kindness. The idea of a sly and more cunning Cinderella is also highlighted by the ambiguity of when Cinderella loses her shoe. Perrault writes it so that it is unclear if she loses the shoe by accident... or if she deliberatly drops it. Same cunning with Donkeyskin - she does have on her own the idea of dropping a ring into the cake for the prince, ensuring her marriage with him...

So while the female protagonists of Perrault are definitively NOT active, it does not mean they are dumb or just pretty faces or that they are just rewarded for being "nice". They are intelligent, they know how to go around, there is a certain celebration of the "feminine cunning" if you will. Diamonds and Toads' moral isn't about actually being nice ; it is about learning when to be polite and when to do flattery when needed. Perrault's fairytales truly are about glorifying inventivity, intelligence and tricks. And the "passive character only good at being beautiful and married" does not exclusively apply to women. The marquis de Carabas is a good example, but what about the prince of Sleeping Beauty? All he does is literally... come in. Arrive. And that's it. How does he save Sleeping Beauty from her sleep? He just enters the castle, and suddenly she wakes up, not even a kiss. How does he save his wife from the ogress? He comes in and asks what's going, and everything is solved immediately. The actual heroic force of the tale is the butler, who is the one that saves the day - but again, not by using power, but by using tricks, deceiving the ogress that he cannot possibly fight (ogres embodying brutality and violence). In fact you have no monster-killer or dragon-slayers in Perrault's fairytales - the closest of a monster killer is Puss in Boots, but only because he tricks the ogre into turning into a mouse. Little Thumbling does not defeat the ogre by strength or violence - again it is all tricks and deception... and theft.

Because this is the other side of the "active male character". Yes, male heroes in Perrault's tale are more active than their female counterpart. But are they moral or "deserving" because of it? Certainly not. Puss in Boots lies to a king, threatens poor peasants so they say lies, usurps the castle of its legitimate lord and deceives the king into marrying the princess well under her rank. Similarly, Little Thumbling tricks an ogre into committing an infanticide, steals his boots from him (but so far it is all excused because the victims are the worst kind of ogres) - and then he scams a grieving mother into giving away all her fortune, before becoming a personal messenger for adulterers... And the narrator himself points out the immorality of those actions. Once again, it isn't because the male characters are more active that they are supposed to be praised for it... Perrault's tales are ultimately, deep down, hidden under a fake veneer of politeness and romance and galant things, trickster tales.

But to get that, you need to read carefully the stories and place them back into their proper context, and many people failed to do it in the 19th century, wrote a lot of misinformed texts that influence the people of the 20th century, and Disney was yet another relay of this misconception, and from generation to generation it all piled up... Claiming that Perrault was SUBVERSIVE in the second half of the 20th century was something seen as a genius and fresh take - when in fact it is just... just a truth people had failed to see.

However we can't reduce everything to Perrault. I mean the 19th and 20th centuries did reduce everything to Perrault, but let's see at the mother of the French fairytale, madame d'Aulnoy. Each of the female authors of fairytales had their own take and twist on gender norms and gender stereotypes, but given the scope and influence of madame d'Aulnoy (still felt in the 19th century), we will focus on her.

Madame d'Aulnoy's fairytales ARE the ones from which the idea that a fairytale is a "knight saving a damsel in a tower from a dragon" comes from. And, again, from a quick glance, madame d'Aulnoy seems to perfectly embody the dichotomy of "A heroine has to be patient and pretty and saved and pleasant and passive ; a hero has to be an active, vigorous, strong savior and monster-slayer". Graceful and Percinet? (Also known as Graciosa and Percinet). It is Psyche's myth told all over again. The Yellow Dwarf? A king keeps searching for his missing fiancee trapped away, and confronts all sorts of obstacles in-between. The Benevolent Frog? A prince kills the dragon that wants to eat his future wife, who literaly does nothing throughout the tale. The Doe in the Woods? The princess spends her time locked away, turned into an animal or fleeing, while the prince is a warrior and hunter who actively keeps going around.

And yet, once again, this just a watered-down, simplified, 19th century-glasses on vision of madame d'Aulnoy's fairytales. She had a wild, WILD life that led her to understand being an obedient good girl and passive meant NOTHING (in fact I do plan on making a series of posts about the craziness of these female French fairytale authors) - she conspired to have her abusive husband killed, she had to flee the country to escape authorities, she knew more than anyone that women had to be active to save their skin in life. And all throughout her stories, she kept having strong, active, female characters that broke the "passive mold", and on the contrary men that failed to be the "active ideal". All of it wrapped into the craziness, madness and exhuberant firework of animalistic fairies, enormous giants, multi-headed dragons and other clownish looking wizards, so that it looked less obvious at first glance. The princess of the Yellow Dwarf spends her time attacked by the titular dwarf and locked within his domain waiting for a rescue, but the story begins when she decides on her own to undergo a dangerous and perillous travel to find out what her mother suffers from, while the prince is shown to be quite helpless against the magic of the Fairy of the Desert and needs the magic of the mermaid to escape. In the Benevolent Frog, the prince kills the dragon... But at the very end, after being given all sorts of magical artefacts and an impossible horse, and they do the trick instead of him (similar to the prince's so-called "victory" against Maleficent in Disey's Sleeping Beauty, where it was truly the fairies that did the work) ; meanwhile the princess' father, the king, also proved utterly useless at saving his wife and daughter spending several years just... sitting by the side of a lake ; all the while his wife and daughter had to become amazonian huntresses, and the fairy-frog is shown doing all the behind-the-scenes work of saving everybody, using a lot of resources, and performing hard feats such as going at the top of a long staricase made for giants WITH THE BODY OF A TINY FROG, which is why she spends years doing so.

And many more are the tales breaking the mold! Cunning Cinders? The girl literaly CHOPS OFF an ogress' head with an axe, right after pushing an ogre into the oven - and it was no small feat given the ogre was also a giant. In the Pigeon and the Dove, the first time the giant imprisons the princess, putting her in his bag, she gets out by herself, without anybody's help. The Orange-Tree and the Bee? The princess does all the work - saves the prince, hides him, feeds him, nurse him, takes him away ; while also doing all the heroic and clever feats, tricking the ogres, stealing their magic wand, performing magical transformations. No wonder the final transformation is passive for the prince (the orange-tree) and active for the princess (the bee that stings anybody getting too close to the tree). In fact, the fairytale "La princesse Printanière", (Princess Mayblossom in English), seems to be an explicit and literal deconstruction of the passive-active model: the titular princess acts like a typical "good princess" (following her heart's impulses without thinking about it too much ; giving kindly all her food to her lover on a deserted island), only to be met by the harshest of realities (following an unknown pretty boy around is not good, and her lover is a selfish and brutal jerk). She only can escape the bad situation she created for herself by STABBING HER EVIL LOVER IN THE EYE, and then she is greeted by the positive sight of her fairy godmother in a war attire, beating the crap out of the wicked fairy of the story in a celestial duel. In fact, this tale contains a double message about women being active to change their life, because before her "passive episode" on the Island of Squirrels that gives her all sorts of misery, she is active, oh yes. She forces the random boy she just met to follow him, and she plans a whole escape at night - because, like an active character, she wants to determine her life, she wants to just do as she pleases, she show who's in charge... But this is proven bad because as it turns out acting impulsively and harshly without prudence or thought - taking away the hand of the first pretty boy that passes, fleeing rashly at night on a whim without preparing any substantial thing - only leads to disaster and misery (being stuck on a deserted island with an abusive companion). And this is opposed to the good "activity" in the end, one thought about and that is a just reaction to the situation, or well-equiped for handling its problem - the princess killing her would-be-murderer ; the good fairy getting a chariot, weapons and an armor to destroy the old, wicked, rusty Carabosse.

This all comes very clearly and strongly in d'Aulnoy's fairytales - if Perrault wasn't so much about gender as he was about tricks, cunning and cheating the system with well-placed connections ; madame d'Aulnoy clearly had some ideas of how women should learn to be active queens, great warriors, trained travellers, well-equiped survivors and, if need there is, monster slayers. Is it then a wonder that when the authorities and minds of the 19th century took a good look at fairytales, they decided that madame d'Aulnoy should be erased in favor of Perrault, where the ideal female models are a girl sleeping a thousand year, another girl that gets hit without answering back, a princess that becomes a cleaning-girl and a cook good ; or even a nice girl with big diamonds?

What happened? In the case of French fairytales: this. First all the openly subversive authors were pushed aside and buried in oblivion ; then the more subtle ones had their tales oversimplified or read the wrong way until it entered a mold they were not supposed to fit. Madame d'Aulnoy was forgotten, and people took Perrault's jokes seriously.

#fairytales#fairy tales#french fairytales#charles perrault#madame d'aulnoy#perrault fairytales#d'aulnoy fairytales#gender in fairytales#women in fairytales#men in fairytales

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

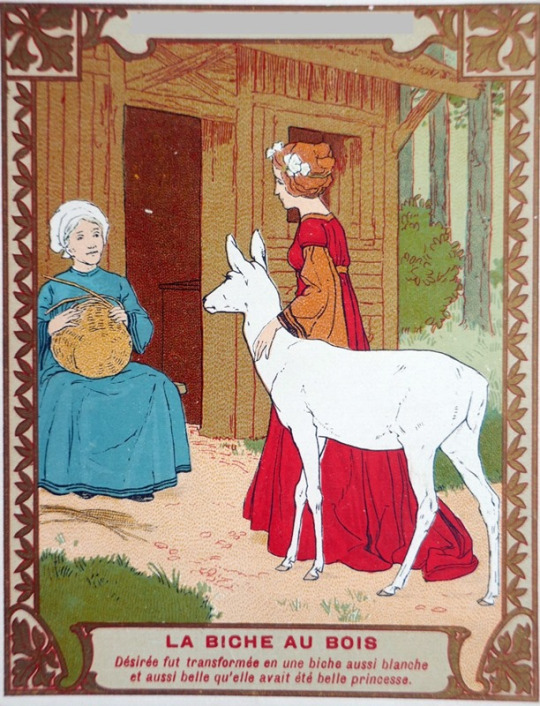

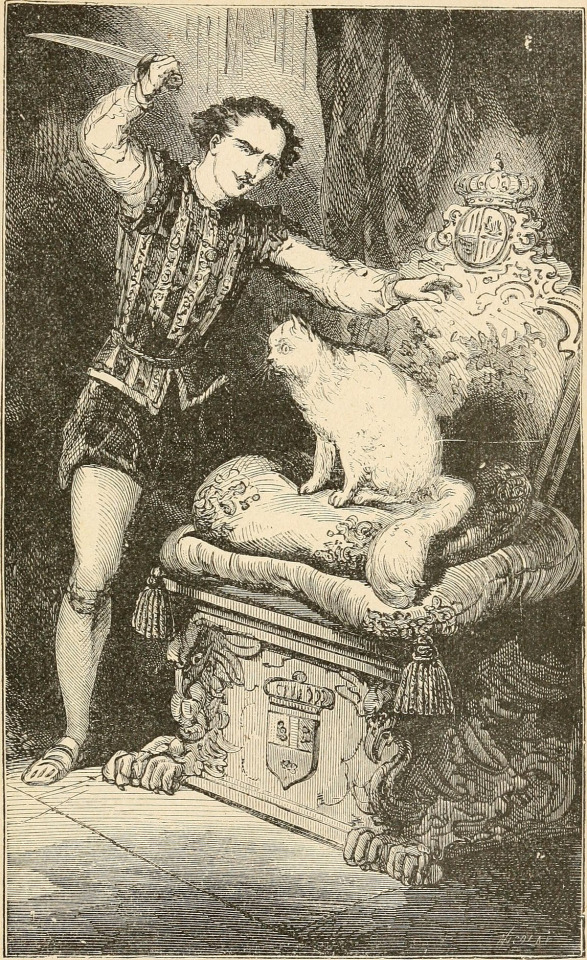

ANONYMUS 19th CENTURY ILLUSTRATIONS FOR THE BLUE BIRD (MADAME D'AULNOY)

@adarkrainbow @princesssarisa @themousefromfantasyland @the-blue-fairie @faintingheroine @angelixgutz @softlytowardthesun @grimoireoffolkloreandfairytales @professorlehnsherr-almashy @amalthea9

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

A fantasy read-list: B-2

Part B: The First Classical Fantasy

2) On the other side, a century of France...

As I said in my previous post, for this section I will limit myself to two geographical areas: on one side the British Isles (especially England/Scotland), and now France. More specifically, the France of fairytales!

Maybe you didn’t know, but the genre of fairy tales, and the very name “fairy tale” was invented by the French! Now, it is true that fairytales existed long before that as oral tales spread from generations to generations, and it is also true that fairy tales had entered literature and been written down before the French started to write down their own... But the fairytale genre as we know it today, and the specific name “fairy tale”, “conte de fées”, is a purely French AND literary invention.

# If we really want to go back to the very roots of fairy tales in literature, the oldest fairytale text we have still today, it would be a specific segment of Apuleius’ The Golden Ass (or The Metamorphoses depending on your favorite title). In it, you find the Tale of Psyche and Cupid, and this story, which got MASSIVELY popular during the Renaissance, is actually the “original” fairytale. In it you will find all sorts of very common fairytale tropes and elements (the hidden husband one must not see, the wicked stepmother imposing three impossible tasks, the bride wandering in search of her missing husband and asking inanimate elements given a voice...), as well as the traditional fairytale context (an old woman telling the story to a younger audience to carry a specific message). In fact, all French fairytale authors recognized Psyche and Cupid as an influence and inspiration for their own tales, often making references to it, or including it among the “fairytales” of their time.

# The French invented the genre and baptized it, but the Italian started writing the tales and began the new fashion! The first true corpus, the first literary block of fairytales, is actually dating from the 16th century Italy. Two authors, Straparola and Basile, inspired by the structure, genre and enormous success of Boccace’s Decameron, published two anthologies respectively titled, Piacevoli Notti (The Facetious Nights) and the Pentamerone, or The Tale of Tales. These books were anthologies of what we would call today fairytales, stories of metamorphosed princes, and fairies, and ogres, and magical animals, and bizarre transformations, and curses needing to be broken, and damsels needing to be rescued... In fact, these books contain the “literary ancestors” and the “literary prototypes” of some of the very famous fairytales we know today. The ancestors of Sleeping Beauty (The Sun, the Moon and Thalia), Cinderella (Cenerentola), Snow-White (Lo cuorvo/The Raven), Rapunzel (Petrosinella) or Puss in Boots (Costantino Fortunato, Cagliuso)...

However be warned: these books were intended to be licentious, rude and saucy. They were not meant to be refined and delicate tales - far from it! Scatological jokes are found everywhere, many of the tales are sexual in nature, there’s a lot of very gory and bloody moments... It was basically a series sex-blood-and-poop supernatural comedies where most of the characters were grotesque caricatures or laughable beings. We are far, far away from the Disney fairytales...

# The big success and admiration caused by the Italian works prompted however the French to try their hand at the genre. They took inspiration from these stories, as well as from the actual oral fairytales that were told and spread in France itself, and turned them into literary works meant to entertain the salons and the courts. This was the birth of the French fairytale, at the end of the 17th century - and the birth of the fairytale itself, since the name “fairy tale” was invented to designate the work of these authors.

The greatest author of French fairytale is, of course, Charles Perrault with his Histoires ou Contes du Temps Passé (Stories or Tales of the Past), mistakenly referred to by everyone today as Les Contes de Ma Mère L’Oie (Mother Goose Fairytales - no relationship to the Mother Goose of nursery rhymes). Charles Perrault is today the only name remembered by the general public and audience when it comes to fairytales. He is THE face of fairytales in France and part of the “trio of fairytale names” alongside Grimm and Andersen. He wrote some of the most famous fairytales: Sleeping Beauty, Puss in Boots, Cinderella... He also wrote fairytales that are considered today classics of French culture, even though they are not as well known internationally: Donkey Skin, Diamonds and Toads or Little Thumbling. The first Disney fairytale movies (Sleeping Beauty, Cinderella) were based on his stories!

But another name should seat alongside his. If Charles Perrault was the father of fairytales, madame d’Aulnoy was their mother. She was for centuries just as famous and recognized as Charles Perrault - when Tchaikovsky made his “Sleeping Beauty” ballet, he made heavy references to both Perrault and d’Aulnoy - only to be completely ignored and erased by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, for all sorts of reasons (including the fact she was a woman). But Madame d’Aulnoy had stories translated all the way to Russia and India, and she wrote twice more fairytales as Perrault, and she was the author of the very first chronological French fairytale! (L’Ile de la Félicité, The Island of Felicity). Her fairytales were compiled in Les Contes des Fées (The Tales of Fairies), and Contes Nouveaux, ou Les Fées à la mode (New Tales, or Fairies in fashion) - and while for quite some times madame d’Aulnoy fell into obscurity, many of her tales are still known somehow and stayed classics that people could not attribute a name to. The White Doe (an incorrect translation of “The Doe in the Wood), The White Cat, The Blue Bird, The Sheep, Cunning Cinders, The Orange-Tree and the Bee, The Yellow Dwarf, The Story of Pretty Goldilocks (an incorrect translation of “Beauty with Golden Hair”), Green Serpent...

A similar warning should be held as with the Italian fairytales - because the French fairytales aren’t exactly as you would imagine. These fairytales were very literary - far away from the short, lacking, simplified folklore-like tales a la Grimm. They were pieces of literature meant to be read as entertainment for aristocrats and bourgeois, in literary salons. As a result, these pieces were heavily influenced (and heavily referenced) things such as the Greco-Roman poems, or the medieval Arthuriana tales, and the most shocking and vulgar sexual and scatological elements of the Italian fairytales were removed (the violence and bloody part sometimes also). But it doesn’t mean these stories were the innocent tales we know today either... These fairytales were aimed at adults, and written by adults - which means, beyond all the cultural references, there are a lot of wordplays, social critics, courtly caricatures and hidden messages between the lines. The sexual elements might not be overtly present for example, but they are here, and can be found for those that pay attention. These stories have “morals” at the end, but if you pay attention to the tale and read carefully, you realize these morals either do not make any sense or are inadequated to the tales they come with - and that’s because fairy tales were deeply subversive and humoristic tales. People today forgot that these fairytales were meant to be read, re-read, analyzed and dissected by those that spend their days reading and discussing about it - things are never so simple...

# While Perrault and d’Aulnoy are the two giants of French fairytales, and the ones embodying the genre by themselves, they were but part of a wider circle of fairytale authors who together built the genre at the end of the 17th century. But unfortunately most of them fell into obscurity... Perrault for example had a series of back-and-forth coworks with a friend named Catherine Bernard and his niece mademoiselle Lhéritier, both fairytale authors too. In fact, the “game” of their “discussion through their work” can be seen in a series of three fairytales that they wrote together, each author varying on a given story and referencing each-other in the process: Catherine Bernard wrote Riquet à la houppe (Riquet with the Tuft), Charles Perrault wrote his own Riquet à la houppe in return, and mademoiselle Lhéritier formed a third variation with the story Ricdin-Ricdon. Other fairytale authors of the time include madame de Murat/comtesse de Murat, mademoiselle de La Force, or Louise de Bossigny/comtesse d’Auneuil. Yes, the fairytale scene was dominated by women, since the fairytale as a genre we perceived as “feminine” in nature. There were however a few men in it too, alongside Perrault, such as the knight de Mailly with his Les Illustres Fées (Illustrious Fairies) or Jean de Préchac with his Contes moins contes que les autres (Fairy tales less fairy than others).

A handful of these fairytales not written by either Perrault or d’Aulnoy ended up translated in English by Andrew Lang, who included them in his famous Fairy Books. For example, The Wizard King, Alphege or the Green Monkey, Fairer-than-a-Fairy (The Yellow Fairy Book) or The Story of the Queen of the Flowery Isles (The Grey Fairy Book).

# These people were however only the first wave, the first generation of what would become a “century of fairytales” in France. After this first wave, the publication of a new work at the beginning of the 18th century shook French literature: Antoine Galland translation+rewriting of The One Thousand and One Nights, also known later as The Arabian Nights. This work created a new wave and passion in France for “Arabian-flavored fairytales”. Everybody knows the Arabian Nights today, thanks to the everlasting success of some of its pieces (Aladdin, Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, Sinbad the Sailor, The Tale of Scheherazade...), but less people know that after its publication in France tons of other books were published, either translating-rewriting actual Arabian folktales, or completely inventing Arabian-flavors fairytales to ride on the new fashion. Pétis de la Croix published Les Milles et Un Jours, Contes Persans, “The One Thousand and One Days, Persian tales” to rival Galland’s own book. Jean-Paul Bignon wrote a book called Les Aventures d’Abdalla (The Adventures of Abdalla), and Jacques Cazotte a fairytale called La Patte de Chat (The Cat’s Paw). I could go on to list a lot of works, but to show you the “One Thousand and One” mania - after the success of 1001 Nights and 1001 Days, a man called Thomas-Simon Gueulette came to bank on the phenomenon, and wrote, among other things, The One Thousand and One Hours, Peruvian tales and The One Thousand and One Quarter-of-Hours, Tartar Tales.

# Then came what could be considered either the second or third “wave” or “generation” of fairytales. It is technically the third since it follows the original wave (Perrault and d’Aulnoy times, end of the 17th) and the Arabian wave (begining of the 18th). But it can also be counted as the second generation, since it was the decision in the mid 18th century to rewrite French fairytales a la Perrault and d’Aulnoy, rejecting the whole Arabian wave that had fallen over literature. So, technically the “return” of French fairytales.

The most defining and famous story to come of this generation was, Beauty and the Beast. The version most well-known today, due to being the shortest, most simplified and most recent, was the one written by Mme Leprince de Beaumont, in her Magasin des Enfants. Beaumont’s Magasin des Enfants was heavily praised and a great best-seller at the time because she was the one who had the idea of making fairytales 1- for children and 2- educational, with ACTUAL morals in them, and not fake or subversive morals like before. If people think fairytales are sweet stories for children, it is partially her fault, as she began the creation of what we would call today “children literature”. However Leprince de Beaumont did not invent the Beauty and the Beast fairytale - in truth she rewrote a previous literary version, much longer and more complex, written by madame de Villeneuve in her book La Jeune Américaine et les contes marins (The Young American Girl and the sea tales). Madame de Villeneuve was another fairy-tale author of this “fairytale renewal”. Other names I could mention are the comtesse de Ségur, who wrote a set of fairytales that were translated in English as Old French Fairytales (she was also a defender of fairytales being made into educational stories for children), and mademoiselle de Lubert, who went the opposite road and rather tried to recreate subversive, comical, bizarre fairytales in the style of madame d’Aulnoy - writing tales such as Princess Camion, Bear Skin, Prince Glacé et Princesse Etincelante (Prince Frozen and Princess Shining), Blancherose (Whiterose)...

Similarly to what I described before, a lot of these fairytales ended up in Andrew Lang’s Fairy Books. Prince Hyacinth and the Dear Little Princess, Prince Darling (The Blue Fairy Book), Rosanella, The Fairy Gifts (The Green Fairy Book)...

# The “century of fairy tales” in France ended up with the publication of one specific book - or rather a set of books. Le Cabinet des Fées, by Charles-Joseph Meyer. As we reached the end of the 18th century, Meyer noticed that fairy tales had fallen out of fashion. None were written anymore, nobody was interested in them, nothing was reprinted, and a lot of fairytales (and their authors) were starting to fall into oblivion. Meyer, who was a massive fan of fairytales, hated that, and decided to preserve the fairytale genre by collecting ALL of the literary fairytales of France in one big anthology. It took him four years of publication, from 1785 to 1789, but in a total of forty-one books he managed to collect and compile the greatest collection of French literary fairytales that was ever known - even saving from destruction a handful of anonymous fairytales we wouldn’t know existed today if it wasn’t for his work. In a paradoxical way, while this ultimate collection did save the fairytale genre from disappearing, it also marked the end of the “century of fairytales”, as it set in stone what had been done before and marked in the history of literature the fairytale genre as “closed off”. All the French fairytales were here to be read, and there was nothing more to add.

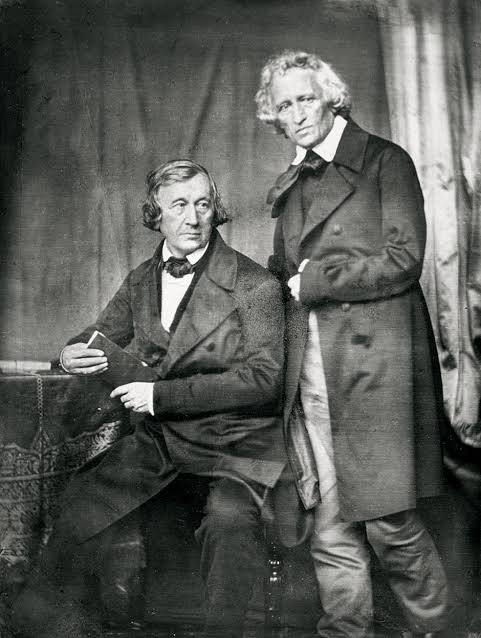

Ironically, Le Cabinet des Fées itself was only reprinted and republished a handful of times, due to how big it was. The latest reprints are from the 19th century if I recall correctly - and after that, there was a time where Le Cabinet was nowhere to be found except in antique shops and private collections. It is only in very recent time (the late 2010s) that France rediscovered the century of fairytales and that new reprints came out - on one side you have cut-down and shortened versions of Le Cabinet published for everybody to read, and on the other you have extended, annotated, full reprints of Le Cabinet with additional tales Meyer missed that are sold for professional critics, teachers, students and historians of literature. But the existence of Le Cabinet, and Meyer’s great efforts to collect as much fairytales as possible, would go on to inspire other men in later centuries, inciting them to collect on their own fairytales... Men such as the brothers Grimm.

#fantasy literature#fantasy read-list#fantasy reading list#fairy tales#fairytales#history of fairy tales#french literature#the one thousand and one nights#charles perrault#madame d'aulnoy#italian fairy tales#the century of fairytales#evolution of fairytales

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

A piece of my soul dies every time someone assumes that Disney owns the entire concept of fairytales. Like people please read about a version that isn't from fucking Disney I promise you it's not hard to do.

I swear to god if I see another Cinderella's stepsister named Anastasia-

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Madame d'Aulnoy

20x30in. Acrylic on canvas

Kacper Abolik, 2023

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Does the French fairytale Princess Mayblossom exist in the Disneyverse?

Eh, I was tempted for a bit as it is where the og name Carabosse comes from, but ultimately I decided that it was 1. A little too close to what we already have with Sleeping Beauty (hence why the name travled over into the Sleeping Beauty Ballet and became ubiquitous with the Wicked Fairy until Maleficent's portrayal gained prominence)

And 2. Its just a little bit too silly? Well not silly so much as tounge in cheek, which was very common for the salon fairy tales/ conte de fees before the Brothers Grimm's more folkloric style gained popularity (one of the reasons Beauty and the Beast has managed to become a staple when so many of the other salon takes have faded was because Beaumont's version reworked it into this folklore style)

And while I can definitely appreciate the tounge in cheek aspect and actually enjoy it from time to time my personal tastes run more towards Grimm's style.

#asks#princess mayblossom#conte de fées#brothers grimm#madame d'aulnoy#jeanne marie leprince de beaumont#madame beaumont#fairy tales#DisneyVerse#carabosse#sleeping beauty ballet#sleeping beauty

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mercredi 1er novembre à 19H, nouvelle émission de la Petite Boutique Fantasque avec la chronique Fières de lettres animée par Monique Calinon de la BNF, autour de madame d’Aulnoy. Cette chronique est précédemment parue dans l'édition numérique de Libération.

Cette émission a été enregistrée et montée au studio de RadioRadioToulouse et diffusée en hertzien, Toulouse : 106.8 Mhz ou en streaming https://www.radioradiotoulouse.net/ et pour tout le reste du temps sur les podcasts de mixcloud.

Programmation musicale :

1) Broken english (Marianne Faithful)

2) Aria populaire (Catherine Ribeiro)

3) Trampled rose (Allison Kraus)

4) Va danser (Monique Morelli)

5) Weren’t born a man (Dana Gillespie)

6) Palmier plastique (Isabelle Mayereau)

7) La Durance (Michèle Bernard)

8) Peace wil com (according to plan) (Mélanie)

+Chronique Fières de lettres n°2 par Monique Calinon : Madame d’Aulnoy

Pour ceux qui auraient piscine indienne, ou toute autre obligation, il y a une possibilité de rattrapage avec les podcasts de la PBF :

Sus aux Philistins !

1 note

·

View note

Note

i want you to be happy with alonzo and demeter

“So she won’t even be a cat anymore? He cuts off her head and her tail, and she just turns into a human like she was never a cat at all?”

Alonzo could see the tiny hint of a smile playing at the side of Munkustrap’s mouth. “That’s the way I heard the story, anyway. The way the humans tell it.”

Demeter’s eyes rolled very faintly, and from her place in her lap, Sillabub’s snort wasn’t nearly so subtle. “Yeah, they would,” she pouted, leaning her head miserably over her mother’s arms.

Munk was getting worse at hiding his smile by the second. “All right, then—how would you give the story a proper feline ending?” His eyes flitted over to Demeter’s, who caught Alonzo’s eye in turn, and he could feel everyone bracing themselves. The tradition had begun shortly after Sillabub was born, when Munk insisted on telling as many bedtime stories as he could to make up for lost time (Alonzo had never been told any himself, most of the stories Demeter knew either had very sad endings or weren’t easily understood by small kittens, and Macavity was… Macavity). Once he had exhausted the supply he could remember from his mother, he’d moved onto the ones he’d heard from Gus—old fairy tales and folk legends from humans playing a long game of “tell her phone” (as Sillabub called it) and writing down all the wrong details. Most of them were pretty harmless since humans were their own favorite animals and the cats were just supporting roles (and no doubt carrying on much more interesting lives off-page somewhere). But whenever the cats became the main characters, that was when the complaints came out. Last night’s story, about Rodillardus and his fierce enemies the Council of Rats, ended in an uproar of there’s no way the rats won, they were too busy fighting each other and Rodillardus could have just squashed them if he wanted to, you’re not telling the story right! And as soon as this Prince came back to the benevolent White Queen’s court after his father—still not satisfied after gifts of stars and ships and crowns from every head in Europe—told him to bring home a girl to marry, Demeter’s tail had puffed out the way it always did before a storm rolled overhead.

“Oh, that’s easy,” Jemima piped up, now bouncing on her haunches at Alonzo’s side. “The Prince is a lot happier in the White Queen’s court anyway, so he should stay there and become a cat with her! It’s a lot less complicated than the way humans get married anyway.”

“I dunno, Jem, that’s a pretty big ask,” Alonzo pointed out. “He’s been human all his life, that’s what he’s used to—how’s she gonna convince him to stay with her?”

“She already gave him an acorn with the Dog Star inside of it!” Sillabub sounded so indignant on the White Queen’s behalf that Alonzo had to choke down a laugh. “She can give him anything he wants—why wouldn’t he want to stay with her?”

“It’s not that simple, sweetheart,” Demeter said, running her claws gently over Silly’s head. “Somebody can give you all sorts of presents, and they don’t have to love you at all. Sometimes the presents are a way to force you to stay with them, and I don’t think the White Queen would be that selfish.”

“That’s true.” Jemima fell silent for a moment, tail at half-mast and twitching anxiously before it suddenly and happily shot upward. “Maybe instead of getting something for the king, the prince gets her a present this time! Something she really needs that’ll make him into a cat at the same time—so he doesn’t have to marry a human girl!”

“Maybe he wants to marry a human girl,” Alonzo said, already grinning. This was going to be a fun response…

And Sillabub did not disappoint. “No, he doesn’t,” she said haughtily. “Humans smell.”

“What do you have in mind, then?” Demeter prodded, nodding to her oldest and giving her youngest an affectionate flick of the ear. Sillabub just reached up to flick her ears right back and grinned at her own daring, completely sidetracked for a moment.

“Maybe it’s a… it’s a cats-eye jewel! Yeah—she’s got so many, but she doesn’t have that one! And Tanto says they’re supposed to help with getting better after you’ve had your heart broken, so… maybe that happened to her in the past, and she needs the jewel to get better, too. And maybe she doesn’t say anything about it ‘cause she likes the Prince, but he’s a human and she’s gonna get her heart broken all over again when he leaves and becomes king, so she asks him to get it for her before he goes. So she can still feel better after.”

“Do you think he’d really come back?” Alonzo asked. “He could always just leave and stay in his own kingdom to become king.”

“Nuh-uh!” Sillabub protested, shaking her head violently. “That’d be so mean, after all she did for him! And he loves her and wants her to be happy!”

“That’s right,” Jemima said with a firm nod of her own head. “He might not really know what’s going on, but he still gets the jewel for her and brings it back and tells her that.” With this, she held out both paws in front of her, lifted her head, and said in her deepest, most “handsome” voice, “I don’t know what’s been making you so sad, Your Majesty, but I already told you that I’d rather spend my life here than at some boring old human castle. Plus, I really do love you and I want you to be happy.”

“And does that turn him into a cat right then?” Demeter asked, leaning as far forward as she could over Sillabub’s head and resting her chin over a paw.

“Well, not right away,” Jemima added. “First he gives her the jewel, and then he kisses her on the head, right between her ears—”

“And the kiss breaks the spell!” Sillabub jumped in. “He’d been a cat the whole time ‘cause some witch had turned him into a human, and now he can go home with the White Queen and live happily ever after!”

Alonzo could practically hear Munk and Demeter’s eyebrows shoot up and Jemima’s thoughts stall for a second before she finally nodded. “Yeah. Yeah, that’s what happens! And so—” she clapped her paws together like she was slamming a heavy book—“that’s how the story really ends!”

Just like that, the dam burst, and Demeter started to giggle helplessly into her paw. Not out of mockery or even because anything was particularly funny (her laugh was much louder when something really took her by surprise), but simply out of sheer joy. The way she pulled Sillabub closer to her chest only clinched it. The story didn’t matter—it was her kittens telling it and her mates coaching them along, and she would have found anything they said delightful, and the moment they did all she could feel was that joy at their presence. It didn’t matter how many times he heard it, but when it came to how far Alonzo would go to hear it again, the distance always got a little further, and the relief at no longer having to hide it washed even more warmly through his chest.

Munkustrap’s expression said it all for him as he dropped a nuzzle onto each queen’s head in turn. “Well, I’m glad my girls enjoyed a version of the story. Even if I didn’t tell it.”

#I'm *ages* late to this but I took the opportunity to spread more Demelonzostrap propaganda--hope it passes muster still. XD#The fairy tale in question is Madame d'Aulnoy's 'The White Cat' which I also remember being very mad at as a child.#cats the musical#alonzo#demeter#munkustrap#jemima#sillabub#asked and answered#bombawife

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Studying 17th century French tales is like. In Perrault's tale, the Chaperon Rouge dies. But not in the Grimm brothers' tales, although they usually picture really graphic stuff. In Perrault's version there is a fairy godmother. In Grimms' there are birds and they pierce the bad sisters' eyes during Cendrillon's wedding, one eye at a time. Also the sisters cut their feet and bleed in the carriage. It is indeed a pantoufle de verre in Perrault's version, not vair. Sleeping Beauty has two children, Aurore and Jour, whom their grandmother attempts to eat. Try and forget Disney's version. And actually the first part of the tale does not have popular roots at all, Perrault mimics them. And the fairy isn't mad that she wasn't invited, she is mad because her cutlery at the wedding was not made of gold as it was specially made for the 7 fairies that were to attend

#I'm gonna panic during the exam and mistake my versions it's certain#Now off to read Madame d'Aulnoy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The latest series of stories I've read in Cinderella Tales From Around the World are from Eastern and Central Europe: Belarus, Ukraine, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Hungary.

*In several Eastern European versions, the Virgin Mary is the girl's helper who gives her finery. She appears either from a well or from inside an oak tree or a fir tree.

*In most of these variants, the heroine goes to church. Only a very few have a ball instead.

*Several also have the stepmother give the heroine a task similar to the Grimms' lentils in the ashes – typically poppy or millet seeds to sort either from the ashes or from sand, or bushels of wheat to clean – and birds help her. Also recalling the Grimms' version (and many others, of course), the third time the heroine flees, the prince usually has the church or palace steps smeared with tar or wax, causing her to lose her shoe.

*In the one Ukrainian version, the heroine has a cow who magically finishes the impossible amount of spinning and weaving the stepmother demands she do every day. Of course the stepmother eventually has the cow killed, but in its entrails the girl finds a grain of corn, which she plants, and it grows into a willow tree. From then on, when she wants finery for church, the tree opens and ladies come out to dress her. In this version, she also loses both of her golden shoes rather than just one in the tar on the church steps.

*Two Hungarian versions, The Three Princesses and Popelusa, and one unnamed Polish version are all near-identical to Finette Cendron. Three daughters of a deposed king are abandoned in the forest, they find an ogre couple's castle, the youngest outwits the ogres and slays them, but then her ungrateful sisters treat her like a servant, etc. Since Madame d'Aulnoy's tale is a literary story, could this be a sign of French influence in Eastern and Central European culture?

*Another Polish version, The Princess with the Pigskin Cloak, combines Cinderella with themes from Snow White. A wicked queen has a magic mirror, which tells her that her stepdaughter is more beautiful than she is. So she orders her servants to kill the princess and bring back her heart, but they let her go and bring back a dog's heart instead. The princess dresses herself in pigskin and finds work as a swineherd, but she knows a certain hollow oak tree that's sacred to the Virgin Mary, and when she goes inside it, she finds a room where she receives finery for church. She finally loses a shoe, is found by the prince and marries him, and the queen dies of rage and grief when her magic mirror tells her the news.

*Several of these versions have the heroine run away from her stepfamily, but unlike most others that use this device, they don't have her work as a servant at the prince's palace, but just find farm work somewhere nearby, a la Perrault's Donkeyskin.

*This brings me to an issue that's appeared in many versions so far, but which I didn't bother to discuss until now. I suppose now is as good a time as any, because it's a theme that appears in many of these Eastern and Central European tales. In so many versions of Donkeyskin/All-Kinds-of-Fur, or any Cinderella story where the heroine leaves her home and finds work as a lowly servant at the royal palace or elsewhere, the prince tends to repeatedly meet her in her rags or animal skins, and he mistreats her. In the versions where she works at the palace, when she takes off his boots or brings him bath water, a towel, and a comb, he throws them at her. Or in versions where she works elsewhere, she meets him on the road, he drops things and she hands them back to him, but instead of thanking her, he hits her with them. Then at the ball or at church, when she's in her beautiful gowns and he's smitten with her, he asks her where she came from, and she replies with allusions to his earlier rudeness, which he fails to understand.

**This is obviously uncomfortable by modern standards. I suppose to the original audiences, it was funny, ironic social commentary: the prince pines over the "mystery princess" with no idea that she's really the scraggly kitchen maid he treats like dirt, and he's clueless when she alludes to her identity. But does it bode well for "happily ever after" when she marries a man who treated her badly? I think this goes to show that in traditional oral fairy tales, there tends to be less emphasis on finding "true love" than on simply escaping from bad situations and achieving safety, comfort, and preferably wealth and high status. It doesn't matter that the prince is a bit of a jerk, what matters is that he makes the girl a princess in the end. Still, when you want her to marry a worthy man and believe he'll make her happy, it's uncomfortable. Different adaptations obviously find different ways to handle it. For example, Grimm's Fairy Tale Classics' "The Coat of Many Colors" avoids all this and has the prince always be kind to Aleia, while "Sapsorrow" from Jim Henson's the Storyteller keeps his rudeness but gives him a small redemption arc, first by finally sharing a sympathetic conversation with "the Straggletag," then by agreeing to marry her when the slipper fits her before he learns her identity.

**Maybe this tradition partly explains why the prince in the classic movie Three Wishes for Cinderella is slightly bratty and rude at first. I know that @thealmightyemprex found that choice off-putting when he reviewed the movie, and I have mixed feelings about it too, but maybe it stems from the fact that in Europe's oral Cinderella stories, bratty princes are surprisingly common.

Speaking of which...

*This book includes the two Cinderella stories from the Czech-Austrian writer Božena Němcová's collection that inspired Three Wishes for Cinderella. One is called The Three Sisters, the other O Popelusce ("Of Cinderella").

**They both follow the same formula. The heroine's kind father (whom the movie replaces with a surrogate-father manservant) sets out on a journey, and his daughter asks him to bring her the first thing that knocks against his head. This turns out to be the branch of a nut tree, containing three nuts, which produce beautiful dresses and shoes that she wears to church three times.

*Each version is slightly different, though, and both are slightly different from the 1973 movie. In The Three Sisters, the heroine Anuska is abused by her own mother and sisters, while in O Popelusce she has a stepmother and stepsisters. Meanwhile, the movie uses a stepmother and just one stepsister. In both stories, the (step)mother cuts the sisters' feet to make the slipper fit, with the movie replaces with their stealing Cinderella's clothes to pass Dora off as her. As I said, both stories have the heroine go to church, while the movie draws on the Western European Cinderella tradition and has a ball, and unsurprisingly, neither the movie Cinderella's sassy tomboy personality nor her dressing as a boy to join a royal hunt can be found in Němcová's original tales.

*Still, it's clear that in some ways the movie draws strongly on Němcová's texts. In The Three Sisters, the second sister's name is Dorotka, which must explain why the one stepsister in the movie is named Dora. And Anuska's first church dress is rose colored with silver trim, just like the movie Cinderella's ball dress

**From now on, in Three Wishes for Cinderella, I think I'll imagine "Anuska" as Cinderella's real name, as it is in The Three Sisters. It's a Czech equivalent of "Annie," and she's definitely a spunky Little Orphan Annie type of character in the movie!

*There's also a Hungarian version that's almost identical to Němcová's, with three dress-producing walnuts. But it has a completely different ending. The heroine doesn't lose a shoe. Instead the prince's servant follows her as far as her house, then puts a golden rose on the gatepost to mark it. Meanwhile, her loving father can't bear to let her be abused anymore and takes her to live with a childless widow in the forest – she's still poor and still has to work, but she's better off than with her stepfamily. When the prince comes to the family's house to look for her, only her stepsisters are there, but then the golden rose magically rises up and floats through the air to the forest cottage, and there she is. But then, in a different (and sadly racist) twist on the common "false bride replaces Cinderella" plot line, a Romani woman pushes the heroine into a lake, steals her magic walnuts, and dresses in her clothes to trick the prince. But the heroine survives by turning into a golden duck, then resumes her true form and finds work as a servant near the palace. But one day, the prince brings his new bride out in public and urges her to tell everyone the story of her life. The Romani woman fabricates a story, but then the real Cinderella speaks up and reveals the truth, and the prince instantly recognizes his true bride. He has the Romani woman executed, the stepmother jailed, and the stepsisters' hair cut off, while the father marries the widow from the forest in a double wedding with his daughter and the prince.

@adarkrainbow, @ariel-seagull-wings, @themousefromfantasyland

#cinderella#fairy tale#variations#cinderella tales from around the world#heidi ann heiner#tw: violence#tw: abuse#tw: racism

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Madame d'Aulnoy wrote a LOT of fairytales. 24 in totals (and her fairytales ranged from three times to nine times longer than your usual Grimm tale). So if you want to start somewhere, I can suggest to you the handful of madame d'Aulnoy's tales that were the most famous and renowned - her "best-sellers" so to speak, that were huge successes and fairy classics throughout the 18th and 19th centuries (and even up to the mid 20th century for some).

The Blue Bird (L'oiseau bleu)

The Doe in the Woods (also known as The White Doe, The Hind in the Woods, La biche au bois)

The White Cat (La chatte blanche)

The Beauty with golden hair (La belle aux cheveux d'or, also translated as "The fair one with golden hair")

The Yellow Dwarf (Le Nain Jaune)

Cunning Cinders (Finette Cendron)

This is truly just a tiny fragment of her work, 6 tales over 24, but these six remained great successes and well-known references until the early 20th century (as opposed to some of her fairytales which fell in obscurity as early as the 18th century).

#madame d'aulnoy#french fairytales#d'aulnoy fairytales#the yellow dwarf#the hind in the woods#the doe in the woods#the blue bird#the white doe#the white cat#cunning cinders#the beauty with golden hair#illustrations

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

@tamisdava2 @the-blue-fairie @softlytowardthesun @superkingofpriderock @faintingheroine @princesssarisa

I once found myself thinking about which fairy tale collectors/authors have the most similar styles to be combined in the same universe. In addition to writing stylistics and characterization, criteria such as cultural and chronological proximity also enter.

The combinations that came were as follows:

Universe D'Aulnoy/Perrault: both French, wrote stories at the same time period that took classical myths and archetypes of folklore with a narrative of more flowery language, seeking to impress an elite in the literary salons.

Universe Grimm/Schönwerth/Němcová: The three Germans and the Czech-Austrian. Schönwerth sought to be more faithful to the way the people told the tales, so his style is more raw, with a narrative that can feel like it ended abruptly, compared to the more polished Grimm and Němcová. But all three are inspired by the rural world of Germany and its neighbors, with a subtle presence of Christianity and marked by the mixture of beauty and wonder with dark and sometimes grotesque violence.

Universe Asbjørnsen and Moe/Jacobs: The Norwegians and the English (born in Colonial Australia). The three, while admiring the work of Perrault and Grimm, also questioned the apparent domination of the French and Germans in fairy tales, so their collection of Norse and Celtic tales was a response to this domination. Its protagonists are often smart and even lazy rogues, its heroines, not always conventionally beautiful, are defined by courage and determination in the pursuit of happiness. If you've read a tale collected in Norway by Asbjørnsen and Moe, you're likely to find a variant of that tale collected by Jacobs in England, Ireland, and Scotland.

Universe Andersen/Oscar Wilde: The two most iconic LGBTQIA+ authors in Fairy Tale history. Their stories read like novellas, with characters that come out of the archetype zone. They are more complex, constantly philosophizing about issues like mortality, faith, good and evil, poverty and wealth. The presence of royalty is rare, and the focus becomes the common man, with his struggles represented by a tin soldier, a match seller, a student or a gardener. When royalty is present, it is possible to see a criticism of it, in short stories such as The Emperor's New Clothes or The Infanta's Birthday. Romance is also rarely the focus, and when it does, there's no guarantee it's going to have a happy ending. Andersen and Wilde introduced the complexities of nineteenth-century modernity to Fairy Tales.

#fairy tales#fantasy#folklore#literature#madame d'aulnoy#charles perrault#franz xaver von schönwerth#brothers grimm#grimm brothers#božena němcová#jorgen moe#peter christen asbjørnsen#joseph jacobs#hans christen anderson#oscar wilde

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Magical summer: The seven-league boots

THE SEVEN-LEAGUE BOOTS

Category: French fairytales

The seven-league boots (in French “Les bottes de sept lieues”) are a very famous European magical item, that were invented by Charles Perrault for his also very famous “Mother Goose Tales”.

The seven-league boots most famously appear in the fairytale “Hop O’ My Thumb” (Le Petit Poucet) : they belong to the large and wealthy ogre in whose house Hop O’ My Thumb and his six brothers end up after being abandoned by their parents. When the little boys manage to escape the house without being eaten (but not before tricking the ogre into devouring his own daughters), the ogre puts on these magical boots to hunt them down – because their power is that, by just doing one step, the person wearing them can cross seven leagues in total. A league (or “une lieue” in the original French) was an old measurement system of France, that basically covered the distance a man could cross in one hour (roughly 4-5 kilometers), so in total the boots allowed in one step to cross either 28-35 kilometers, either the equivalent of seven hours of walk. Well the exact number of meters the boots allow to cross is not important (as the number “seven” is just a thematic number in this fairytale, the same way there are seven little boys lost in the woods and the ogre has seven daughters) – overall the idea is that the seven league boots allow you to advance very fast on very long distances.

With these boots the ogre easily catches up to the boys, but hopefully for them the ogre is just a lazy glutton/drunkard all these efforts of walking outside his house tire him, so he falls asleep beneath a tree near them. Hop O’ My Thumb then quickly steals the ogre’s boots away and puts them on his own feet. The boots magically shrink to his size so that they would fit (and Hop O’My Thumb is named like that because he is REALLY small, so small people he was literally named after a thumb), and he uses them to cross the country – as his brothers go back home (since now the ogre is powerless and they can easily escape), Hop O’ Thumb uses the boots to go back to the ogre’s house to trick his wife into believing her husband was taken hostage during a war and she needs to give him all of their treasure to pay the ransom. Then he returns to his home with the boots, gives the treasure to his parents so his poor family would become rich – and much later he uses his magical boots to deliver messages to and for the king, becoming the official royal messenger.

Charles Perrault also used the seven-league boots in another one of his fairytales, “Sleeping Beauty”, even though nobody remembers this because they are used in one line, as a little “funny eater egg” detail (so that those that read Hop O’ My Thumb would just wink and nod upon hearing about the boots in Sleeping Beauty) : basically, when the princess pricks her finger and falls asleep, the good fairy godmother that changed the death spell into a sleeping spell is warned of the event by a dwarf wearing the seven-league boots.

Given the French fairytales of the 17th century were actually a distraction and game of small social and literary circles, it makes sense that the other fairytale writers and tellers of the time would reuse and play with the concept : as a result, when Madame d’Aulnoy wrote her fairytale “The orange-tree and the bee”, she had her own ogre (called Ravagio) use seven-league boots to hunt down his adoptive daughter who eloped with the prince he intended to eat for supper.

As you might know, the French fairytales became so popular that they poured into the other cultures of Europe, and so the seven-league boots became an iconic and recurring element in posterior fairytales of other cultures. The seven-league boots almost made it into the Grimm’s fairytales when they included a variation of Hop O’ My Thumb named “Okerlo” (an attempt to translate in German the term “ogre”), but they then removed the tale from their next edition of their tales because they realized it was a French tale, not a German one – but you can still find the “meilenstiefel” or “mile-boots” in the “Sweetheart Roland” story ; and magical travelling shoes in “The King of the Golden Mountain”. They also entered deeply German culture and literature by being featured in the story “Peter Schlemihl” alongside other popular elements of fairytales ; and then being used in the “Faust” play of Goethe. The boots can also be found back in several Finnish and Estonian fairytales under the name “boots of seven Scandinavian miles” (seistsemän peninkulman saappaat, or seitsmepenikoormasaapad) ; we also have in Norway the “femten fjerdinger” boots – the boots of fifteen fjerdinger, roughly 34 kilometers) that pop up in “Soria Moria Castle”. And while not exactly a copy of the seven-league boots, fast-travelling shoes do also appear in various English fairytales, such as in Tom Thumb (in which he has shoes that allow him to travel anywhere) or in Jack the Giant-Killer (an ogre has “shoes of swiftness”).

- - -

But in truth it is hard to say where Perrault's influence stop and traditional folklore begins, because there ARE magical shoes of travel in a lot of folkloric traditions and fairytales that Perrault's own tales couldn't have influenced. For example there is an Hungarian tale called Zsuka and the Devil which has the devil keep "sea-striding shoes" - but here we can draw a parallel as the tale is Hop O' Thumb but with a woman instead of a boy and a devil instead of an ogre. However, when it comes for example to the "sapogi-skorokhody" or "fast-walker boots" that appear in the Slavic fairytales, the link could be harder if not impossible to make.

You see, Charles Perrault didn't "invent" the shoes that make you hyper fast or allow you to travel supernaturally. He just kept a tradition that existed before - dating back to Ancient Times, with Hermes and Perseus' flying shoes for example, or the "shoes of speed" of Loki in Norse mythology. It is a recurring element of folklore that does pop up everywhere, the same way his writing of "Hop O' My Thumb" was actually a rewrite and adaptation of a recurring traditional fairytale which had many different regional versions in France. BUT here is the thing: Perrault reinvented this archetype with the iconic name of "X measure boots" or "V measure shoes" - and this is why it is much easier to trace back Perrault's influence on fairytales that use shoes named "the 10 miles boots" or something similar.

It is commonly theorized that Charles Perrault found the idea of naming these magical boots as such, because in France at the time (aka 17th century France) by reusing an actual expression of the time: the boots of post-boys at the time were commonly referred to as "seven-league boots". It was a reference to all the road and travels post-boys had to do between two coach inns (in truth it was more like four or five leagues, but anyway). Charles Perrault thought it would be funny to take back this traditional expression and apply it literaly in his fairytales.

One last point might also be drawn to the importance of boots in Perrault's fairytales, as they are also a symbol of wealth and social ascension. Boots weren't worn by peasants or low-class, except if they were messengers or domestics to wealthy people : boots were usually worn by precisely these wealthy or upper-class people, either for horse-riding or for the hunt. And in both Hop O' My Thumb and another one of Perrault's fairytale, Puss in Boots, having boots also means for who wears it obtaining riches and a higher social status. In the case of Hop O' My Thumb, the titular little boy steals the boots from a very wealthy giant that has everything in abundance (tons of foods, a big treasure, a vast house, lots of daughters) and once obtained, he uses them first to make his family rich, then to find a high-positioned and well-paid job. Conclusion: if you want to become high-class, get boots.

#magical summer#seven-league boots#fairytales#french fairytales#charles perrault#madame d'aulnoy#magical shoes#ogre

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

HAPPY 50TH COMIC!!!! <3

The tale that the Charming parents hail from is unknown, but I do recall seeing something about their tale involving an ogre. Since it's obviously not Puss in Boots, the most likely candidate for their tale in my opinion is The Bee and the Orange Tree, a somewhat obscure late 17th century French fairytale by Madame d'Aulnoy featuring a prince rescuing a princess from her ogre foster parents. I decided to headcanon this as the tale of the Charming parents, with the father being Prince Aime and the mother being Princess Aimee and Darling being expected to inherit her mother's role.

Also, I love Maddie silently judging you in the last panel. Maddie knows what you did last night...

#source: kimbbearly on tumblr#creator: yours truly#images from: youtube printscreen#ever after high#incorrect quotes#daring charming#darling charming#maddie hatter#the bee and the orange tree#headcanons

18 notes

·

View notes