#richard duke of york

Text

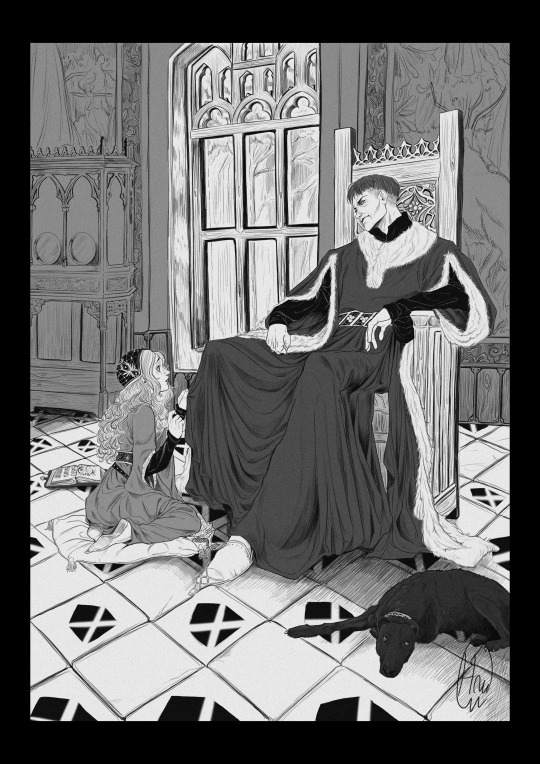

Book illustration - Anne & Cecily Neville.

There's not much difference between a woman and a caged bear cub. We are prisoners in our own marriage, Cecily.

#the wars of the roses#15th century#middle ages#medieval#medieval fashion#illustration#sketch#drawing#art#edward iv#elizabeth woodville#cecily neville#richard duke of york#anne countess of stafford#henry vi#humphrey duke of gloucester#john duke of bedford#catherine of valois#elizabeth of york#artists on tumblr#character design#english history#the white queen#the white princess#book writting#medieval costume#house of york#house of lancaster

93 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you feel about the house of york

I feel like it's a medieval dynasty that one a war. That's about it.

I also think that Richard Duke of York was nothing more than a jealous cousin that saw the perfect opportunity to climb the ladder and took it, justly paying the price. Edward IV's anger over his and his brother's death is understandable and so were his actions. Too bad that he didn't saw that the Duke of York's ruthless ambitions had trickled down to his sons Richard and George before they tried it with him. I think the Woodvilles were overtly greedy and took too much of the hand that fed them making the nobility hate them, and they also paid for it. I mean, arranging prestige marriages for every single Woodville? I get it, one of them was the Queen, but come on now, they clearly overplayed.

On the whole, I find this representation of the Yorks as this typical Good HeirsTM that took their rightful place on the throne and stepped up through harsh times that persists so much to this day lame and reductive. The truth of the matter is, they were never more just and GoodTM than the Lancasters. The Lancasters successfully organized a coup and sat the throne, the Yorks did the same, demonizing Henry VI and Queen Margaret of Anjou through propaganda as a freak and an overly ambitious femme fatale respectively, while casting their teenage son as a cruel bastard. All for defending fiercely what was by right theirs (we have Shakespeare to blame for that as well).

#wars of the roses#house york#house lancaster#edward iv#richard duke of york#george plantagenet#richard iii#Henry vi#margaret of anjou#edward of westminster#medieval warfare#medieval england#late middle ages

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the end, politics was an accretion of personal decisions, and that means that the personality of the protagonists cannot be left out of the discussion. It determined not only how they reacted to the situations in which they found themselves, but how others reacted to them. The growing support for Edward IV in 1461 must have owed something to the realisation that he would make an effective king - whereas his father never seems to have been regarded in that light.

--Rosemary Horrox, "Personalities and Politics", The Wars of the Roses (Problems in Focus), edited by A.J Pollard

...When the worst had happened, and civil war was a reality, the overwhelming imperative was to find some way of restoring order. At the level of high politics, what this entailed in practice was a rallying around the de facto king. The Wars of the Roses, far from weakening the monarchy, actually strengthened it, since the king was the only man able to surmount faction. In spite of (Henry VI’s) manifest failings, Richard, duke of York's criticism of the regime commanded little high-level support - and would have commanded even less but for the crown's alienation of the junior branch of the Nevilles, headed by York's brother-in-law the earl of Salisbury. York in fact never did attain the political viability to break the vicious circle of temporary ascendancy and political exclusion. It was his son, Edward, earl of March, who finally mustered enough support to take the throne. He was able to do so in part because the situation had been transformed by the country's descent into open war, which reduced the compulsion to uphold the king as the embodiment of stability. Once it was no longer a matter of averting war, but of stopping it, political opinion began to divide more evenly between Henry VI and his rival.

However, the crucial change may well have been York's own death at the Battle of Wakefield late in 1460. In the ensuing months Edward of York was able to present himself as the man who could mend the shattered political community. That self-identification with unity proved immensely potent, and it was not a role which could plausibly have been filled by his father. In the eyes of contemporaries, York had been the begetter of faction: a man tainted by his willingness to go to extremes.

#oof💀#I can't decide if this is more awkward or ironic#But it's nevertheless VERY interesting#Edward IV#Richard Duke of York#my post#wars of the roses#Edward still had to win Towton (ie: a military victory) to actually secure his kingship and bring over a lot of the nobility to his side#But this point is nonetheless very true - not just for his road to victory but also for the image he cultivated after he had won#It's very common to hear about how Edward IV was eventually viewed by many as a 'better' alternate to the throne than Henry VI#But what isn't acknowledged nearly as much is how by that logic he would've equally been viewed as a better alternate than his father#Ironically this entire point is made even clearer by the actions of York's own staunchest supporters ie the Nevilles#Certainly both Edward & Warwick learned their lesson from York's disastrous attempt at an acclamation in 1460#Considering how comparatively well-planned and well-executed Edward's own acclamation was in comparison#This is another reason I dislike how the Yorkists are often viewed and spoken of as a collective. the broader dynastic label tends to#minimize the differences in certain situations like this one or Richard's usurpation

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

I find it so weird when people talk about Henry VII’s ‘dollop of royal blood’ as if royal blood really was something that was scientifically measured before someone could declare their claim to the English throne. For example, Rosemary Horrox (who I admire greatly as a historian btw) once said:

That a young man with no claim to the throne – beyond being the grandson of Henry V’s widow and the son of a great-great-granddaughter of Edward III – could in 1485 amass enough support to overthrow the reigning king can be seen as just the final stage in the cascade of depositions which followed that of Henry VI in 1461.

The thing is, when Richard of York presented his claim to the English throne in 1460 he was exactly what Henry Tudor was in 1485: the son of a great-great-granddaughter of Edward III, and many people today think he had a valid claim. You could go on and on about the Beauforts being legitimised sufficiently or not, but to measure the exact quantity of royal blood compared to other contestants is just pointless. For comparison:

Edward III → Lionel of Antwerp (son) → Philippa Plantagenet (granddaughter) → Roger Mortimer (great-grandson) → Anne Mortimer (great-great-granddaughter) → Richard of York (‘the son of a great-great-granddaughter of Edward III’) → Edward IV and Richard III (the grandsons of a great-great-granddaughter of Edward III etc)

Edward III → John of Gaunt (son) → John Beaufort (grandson) → John Beaufort (great-grandson) → Margaret Beaufort (great-great-granddaughter) → Henry Tudor (‘the son of a great-great-granddaughter of Edward III’)

#like lol might was right and that's it#henry vii#richard duke of york#historian: rosemary horrox#idk talk of blood purity never sits right with me

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I love your posts and insights about the Wars of the Roses. Do you think you could talk a bit about Richard Duke of York? What do you think his character/life was like? Also re his and his sons appearance??

Hi! I'm sorry for taking so long to answer your ask, but I just couldn't find the time before. (I happen to currently have more free time than usual, due to particular circumstances.)

Thank you for asking about Richard, Duke of York, because I think he is a very interesting historical figure who gets usually overshadowed by his sons. If one day someone decides to make a new TV show or movie about the Wars of the Roses that doesn't just skip over the 1460s and start when Richard Duke of York, his life would make quite a compelling story.

As for historical books about him, I recommend Matthew Lewis' Richard, Duke of York: King by Right.(2016), which is a very detailed (but still very interesting, to me at least) account of his life. I read it a few years ago so I don't remember all the details, only the main points and overall impression I got from it.

My main impression is that, although he is often portrayed by pro-Lancaster writers as power-hungry, this is far from the truth. It seems unlikely that he ever wanted to challenge Henry VI and put himself forward as king, before the last year of his life - and this controversial act makes perfect sense when you look at the circumstances and the things that had happened to him and his family just before that. Besides, while Richard was for a long time - before Edward of Lancaster was born - Henry VI's heir, it seems more likely that he was hoping that his son would one day succeed Henry, rather than himself, since Henry was younger than him and in good physical health. Rather than the result of some evil overreaching lust for power, it seems to me that his conflict with the Lancaster/Beaufort faction was a result of the years of frustration over his treatment. As the conflict grew, staking his clai to the throne throne may have been an act of desperation (since, at that point, this must have seemed like the only way to protect himself and his family), but maybe he was also just really done with everything, and with Henry VI and unwilling to support him as King. Considering the context, I don't really think even pro-Henry VI people could really blame him.

But first I think we'd have to go back to the beginnings. I think that Richard's childhood and, most of all, what happened to his father, is what framed his whole life. Richard's mother, Anne Mortimer (great-granddaughter of Lionel, Duke of Clarence, the second of the sons of king Edward III who survived childhood), died soon after giving birth to him, aged only 22. His father, Richard, Earl of Cambridge (himself the grandson of Edward III through his 4th surviving son Edmund, the Duke of York), was executed - when Richard wasn't even 4 years old - for his involvement in the Southampton Plot to depose Henry V in favor of his brother-in-law, Edmund Mortimer (but since Edmund had no children, really in favor of his own son Richard, who would be his heir).

After all, the Lancasters, i.e., Henry V's father Henry IV , himself the son of Edward III's third son John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, had deposed Richard II, skipping over the line of the elder son Lionel, so it could have been reasonably argued that the Mortimers's claim to the throne was stronger (sure, it was through the female line - but so was the English royals' claim to the throne of France - France had installed the Salic Law to bar the female lines from the throne of France - really to bar the English kings from it, but England did not). But Henry V was a crowned and annointed king, so trying to depose him would have been treason... (Even though he was only on the throne because his father had deposed, imprisoned and starved to death another annointed king. To quote one of my favorite TV shows, "Treason, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder". But it's crucial whether you won or lost.)

Just a couple of months later, his uncle Edward, his father's elder brother, was killed without children, Richard became the heir to his lands and titles and became the Duke of York at the age of 4. Ten years later, after the death of his maternal uncle Edmund, he also became heir to the Mortimer estates.

So, young Richard grew up as an orphan but also one of the technically most powerful and richest people in England, and heir not just to titles and lands but also the claims to the throne from not just the 4th but also the 2nd son of Edward III (the latter being the senior line of succession after the deposition and death of Richard II) to rival the Lancaster dynasty. And at the same time, he lived in the shadow of the fact that his father had died as a traitor and rebel against the crown for pressing that same claim.

If I were to speculate about Richard's personality and how his upbringing shaped it, I think he was a person who tried hard to do everything right, to fulfil his duties in every way and be beyond reproach, exactly because he had so much responsibility and probably so much to prove. Something that really strikes me about Richard is that he seemed almost too perfect: competent, respected nobleman popular with the people, in a stable marriage, not known to have any mistresses or sexual transgressions, had seven children who suvvived childhood including four sons...What the contrast to Henry VI, a nice and pious man but notoriously disinterested in ruling (long before he started showing signs of mental ilness and became catatonic), prone to relying on favorites such as his extremely incompetent cousin Edmund Beaufort. and also, for a long time, unable to conceive a child with his wife Margaret of Anjou (and possibly uninterested in trying), before finally siring Edward.

And this is exactly why Richard must have come across both as such a threat in the eyes of Queen Margaret, Edmund Beaufort and other people around Henry VI. How could they not be wary of his powerful man, Henry's cousin and heir, who had all the qualities you'd want in a king, which Henry lacked? However, if he was really power hungry and eager to replace Henry as king, he certainly didn't show that for many years. I think he must have been especially eager to prove his loyalty with the "son of the traitor" thing hanging over his head since he was a child. But he was nevertheless constantly under suspicion and distrusted by the Queen and her faction. I remember reading the details of his career, which come across as Richard constantly having to prove himself while being denied positions or sent away - his appointment in Ireland was really meant a virtual exile, to get him away from court (but it resulted in him and by extension the York dynasty gaining long-term popularity and stronghold in Ireland). (One of the common myths is that Richard was warlike and that this got him in conflict with the supposedly more peaceful faction - in fact, if I remember correctly, it was Edmund Beaufort who acted belligerent in France but made a mess of things, which Richard then had to clean up.)

It all must have been really frustrating to Richard - he was doing everything right, but it was never enough, and he had to prove his loyalty over and over. Maybe the Queen and the Lancastrians really created a self-fulfilling prophecy. Theoretically, I suppose Richard could have been binding his time and playing some really long con to depose Henry, but that seems unlikely looking at the details.

Instead, I think the most likely reason for his decision to start claiming the throne for himself in 1460 is that the conflict had become too harsh and the situation too desperate after he had been proclaimed a traitor to the crown and had to flee to Ireland. The attainder meant he was to be killed if he set foot in England again, and his family was disinherited. He had to successfully invade (ironically, he was in a similar situation that the future Henry IV before he deposed Richard II) and then either make himself Lord Protector again or even Henry's heir, or to proclaim himself the true king.

But I thin the earlier loss at the castle of Ludlow, when the Yorkist troops were reluctant to fight the Lancastrian army when Henry VI himself was at its head (a puppet or not, ineffectual or disinterested, the annointed king was seen in an almost religious light and had enormous symbolic authority), and then the brutal sack of the castle, where Richard's wife Cecily Neville, his daughter Margaret and his two youngest children George and Richard (who was only 7) at the very least had to witness awful scenes of rape and pillage, by that same army with Henry as its nominal head... this may have been the straw that broke the camel's back and made Richard decide he was done with Henry VI. (Whether or not he had earlier really respected Henry or just respected his position as King.) And I really can't blame him.

I wonder how he felt when he finally made that decision, which would lead to his death less than a year later - followed by his eldest son's successful campaign and decisive victory over the Lancasters? Was it sheer desperation and survival, was he angry, did he decide he deserved the crown after all and was going to take it, did he feel any pride and relief that his decision would also basically mean an annoncement that his father was not really a traitor? I don't know, but I'm surprised there aren't more novels, movies and TV shows with him as the protagonist, delving into those questions.

Now, as for Richard's appearance and those of his sons.

There doesn't seem to be a lot of direct evidence of what he looked like (and the drawing that, for whatever reason, you'll find most often as a supposed portrait of him on Google definitely isn't reliable), but there are some indirect ones: Richard III was said to particularly look like his father. The phrase about Richard III looking like his father in face and figure has been often interpreted to mean that Richard, Duke of York was short, because Richard was a bit on the shorter side. However, there's no indication whatsoever that York was short, and we know that Richard III was shorter than he would've otherwise been due to his scoliosis (but still quite taller than some other men such as Niklas von Popplau, the German knight who was his guest and described him later). And to put things into context - Richard III was being praised for his similarity to his father and the mention of his figure seems more likely to be a reference to the late Edward IV becoming notoriously overweight in his 30s (while Richard was slim and lean), so I think it simply meant that their father Richard Duke of York was slim and in good shape when he was killed at the age of 49.

This miniature portrait of Richard Duke of York from the Talbot Shrewsbury book (around 1445, when he was 33/34, around the same age Richard III was when he died) shows a blond man with a strong chin - similar to that seen in the portraits of his sons Edward and Richard, an acquiline nose similar to Richard, and full lips (the one detail that doesn't match Richard that well and in fact seems more similar to Edward, going by their portraits).

There are a lot of myths about what the brothers looked like that were mostly created by historical fiction - including that Edward and George were tall and strong while Richard was small (in fact, I don't think we have any contemporary evidence of what George looked like), or that Edward or maybe George too were blond while Richard was dark (both Edward and Richard seemed to have medium brown hair) or that Edward and Richard looked nothing alike. I actually think there is quite a resemblance between the two brothers mostly in chin and face shape, which probably would've been obvious before Edward had gained weight and his face shape got much fuller.

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

— 2 October 1452, Richard III is born

The last member of the house of York to sit upon the throne of England, in his lifetime Richard III seems to have been chiefly famous for his loyalty and good service to his elder brother, King Edward IV. However, after his own government was overthrown by a usurper with French support, but no valid claim to the English crown, Richard became famous chiefly for his heavily blackened reputation. This was by no means a unique event. Rewriting of history has occurred on other occasions in the wake of a violent change of regime.

— John Ashdown-Hill

#richard iii#historyedit#history#perioddramaedit#wars of the roses#english history#house of york#perioddramasource#gifshistorical#periodedit#periodedits#userstream#medieval#medieval history#tom hiddleston#fancast#richard duke of york#cecily neville#edward iv#my edit#look how they massacred my boy richard iii

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the years before his death Prince Edward gradually came to symbolize Lancastrian hopes: Lancastrian troops bore not only the King's but also the Prince's livery, of crimson and black with ostrich feathers. Although in the agreement of October 1460 between Henry VI and Richard, Duke of York, Prince Edward was denied the right of inheritance in favour of York himself, Edward could have been venerated as the 'natural', legitimate heir of Henry VI. He was the only and last Lancastrian descendant: Henry VI had no other children or Siblings, and all his uncles were dead by then. Edward's reputation required that rumours about his parentage be opposed and that his military prowess, courage and leadership be emphasized.

Danna Piroyansky, Martyrs in the Making: Political Martyrdom in Late Medieval England (Palgrave, 2008)

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

So today, instead of finishing my essay, I chose procrastination and this is where I ended up. This "book" is obviously trash but 3.64?? Anyways I'm going to read it ironically.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard Plantagenet, the third Duke of York was born on the 21st September, 1411 which was exactly 593 years before that of the Communist Party of India ( Maoist) with whom he shares his birthday. He spent his youth battling the French feudalists and imperialists in Normandy thereby avenging the colonisation of England by the Normans some three centuries prior and had built himself mass support amongst the peasantry and the proletariat of England and Ireland to overthrow the elements of the feudal classes who favoured the Henry of Lancaster ( commonly known as Henry VI & II of England and France) which was wont to partake in anti-people measures ( amongst other things by corruption and graft thereby letting the Beauforts monopolise the control of the productive forces in England and by depriving the poorer peasantry and proletariat who had less than 40 shillings from having any say in governance by depriving them the right to vote in 1430). As it is evident, he was in contact with the mass uprising led by Jack Cade and the fact that he had based his demands on what the people had demanded in the uprising but in a more formalized manner shows that he came up with the Maoist practice of implementing the mass-line on his own. He then waged the People's War against the House of Lancaster and was ultimately beheaded in Wakefield at 1460 by the Lancastrian roadsters.

#maoism#marxism-leninism-maoism#marxism leninism#house of york#house of lancaster#plantagenets#richard duke of york#richard plantagenet#henry vi#socialism#socialist revolution#wars of the roses#shitpost#english history#edward iv

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cecily Neville and her father, Ralph.

That's it. That's all the description I can do before I pass out.

#the wars of the roses#15th century#art#character design#sketch#drawing#cecily neville#ralph neville earl of westmorland#medieval#historical art#historical fiction#digital artwork#richard duke of york#hundred years war#humphrey duke of gloucester#john duke of bedford#neville#joan beaufort#father and daughter#artist on tumblr#edward iv#elizabeth woodville#oc artist#middle ages#british history#elizabeth of york#nobility#isabel neville#richard iii#henry vi

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The late medieval nobility were not always gleefully ganging up on the king. On the contrary, a lord with pretensions of dominance would find his severest critics among his fellow nobles, who seem on the whole to have considered an inept king infinitely preferable to a colleague wielding excessive power. The isolation of Richard of York in the 1450s can be paralleled in the fourteenth century by Thomas of Lancaster, whose assumption of dominance in opposition to Edward II was much disliked, in spite of the king's own unpopularity."

-Rosemary Horrox, "Personalities and Politics", The Wars of the Roses (Problems in Focus), edited by A.J Pollard

#this chapter also points out how Warwick and Clarence found almost no noble backing outside their own immediate circle when they#imprisoned Edward IV - and were so demonstably unable to represent royal authority that they were forced to free him#I wanted to add that here originally but since the situation wasn't exactly the same as the two mentioned above I left it out#richard duke of york#henry vi#edward ii#thomas of lancaster#queue

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

I read a remark that earl of march Edward (later Edward IV of England), like many York parties at that time, initially opposed his father, Duke of York's attempt to seize the throne?

Yeah, he presumably opposed his father's usurpation with Warwick on various discussions with the Yorkist leadership. However, new evidence hints that this is untrue. Warwick did sail to Ireland in 1459 to confer with York, and Hicks discovered a letter from Edward IV in 1463 about Warwick 'giving him great news' on his return from Ireland.

It's difficult to assess what complicated thoughts someone has on one of the most decisive choice his father made, a decision which dramatically influenced his own life. I think it's possible Edward IV pushed back and forth on the issue, especially after seeing the peers' reluctance to depose Henry VI. However, because it's what happened, March ultimately followed his father no matter his choice on usurpation. A divided house can't survive, and he knew that. And it's telling that when the choice became his, he followed his father's steps and usurped the crown.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me towards the British monarchy: 😤

Me towards true crime: 😤

Me towards any discussion about the Princes In The Tower: 👀

#princes in the tower#Edward V#Richard Duke of York#those murdered British boys#look i feel bad for them they were just kids even if they were royalty#charlie please say you'll investigate the remains in the urn#history

3 notes

·

View notes