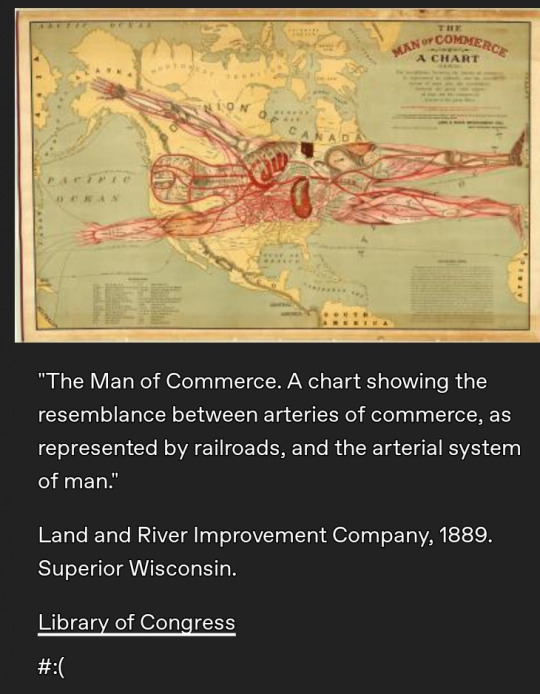

#the Victorian/Gilded Age state of things

Text

It's a big mess of hubris; the manipulative use of scientific language to legitimate/validate the status quo; Victorian/Gilded Age notions of resource extraction; the "rightness" of "land improvement"; and the inevitability of empire.

This was published in the United States one year before the massacre at Wounded Knee.

This was the final year-ish of the so-called "Indian Wars" when the US was "completing" its colonization of western North America; at the beginning of the Gilded Age and the zenith of power for industrial/corporate monopolies; when Britain, France, and the US were pursuing ambitious mega-projects across the planet like giant canals and dams; just as the US was about to begin its imperial occupations in Central America and Pacific islands; during the height of the "Scramble for Africa" when European powers were carving up that continent; with the British Empire at the ultimate peak of its power, after the Crown had taken direct control of India; in the years leading up to mass labor organizing and the industrialization of war precipitating the mass death of the two world wars.

This was also the time when new academic disciplines were formally professionalized (geology; anthropology; archaeology; ecology).

Classic example of Victorian-era (and emerging modernist and twentieth-century) imperial hubris which implies justification for its social hierarchies built on resource extraction and dispossession by invoking both emerging technical engineering prowess (trains, telegraphs, electricity) and the in-vogue scientific theories widely popularized at the time (Lyell's work, dinosaurs, and the geology discipline granting new understanding of the grand scale of deep time; Darwin's work and ideas of biological evolution; birth of anthropology as an academic discipline promoting the idea of "natural" linear progression from "savagery" to imperial civilization; the technical "efficiency" of monoculture/plantations; emerging systems ecology and new ideas of biogeographical regions).

While also simultaneously doing the work to, by implication, absolve them of ethical complicity/responsibility for the cruelty of their institutions by naturalizing those institutions (excusing the violence of wealth disparities, poverty, crowded factory laboring conditions, mass imprisonment, copper mines, South Asian famine, the industrialization of war eventually manifesting in the Great War, etc.) by claiming that "commerce is a science"; "pursuit of profit is Natural"; "empire is inevitable".

This tendency to invoke science as justification for imperial hegemony, whether in Britain in the 1880s or the United States in the 1920s and such, might be a continuation of earlier European ventures from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries which included the use of cartography, surveying/geography, Linnaean taxonomy, botany, and natural history to map colonies/botanical resources and build/justify plantations and commercial empires in the Portuguese slave ports, Dutch East Indies, or the Spanish Americas.

Some of the issues at play:

-- Commerce is "A Science". Commerce is shown to be both an ecological system (by illustrating it as if it were a landscape, which is kinda technically true) and a physiological system (by equating infrastructure/extraction networks with veins) suggesting wealth accumulation is Natural.

-- If commerce/capitalism are Natural, then evolutionary theory and linear histories suggest it is also Inevitable (it was not mass violence of a privileged few humans who spent centuries beating the Earth into submission to impose the Victorian/Gilded Age state of things, it was in fact simply a natural evolutionary progression). And if wealth accumulation is Natural, then it is only Right to pursue "land improvement".

-- US/European hubris. They can claim to perceive the planet in its apparent totality (as a globe, within the bounds of extraterrestrial space as if it were a laboratory or plantation). The planet and all its lifeforms are an extension of their body, implying a justified dominion.

-- However, their anxiety and suspicions about the stability of empire are belied by their fear of collapse and the simultaneous US/European obsession at the time with ancient civilizations, the "fall of Rome", classical ruins, etc. At this time, the professionalization of the field of archaeology had helped popularize images and stories of Sumer, Egypt, the Bronze Age, the Aegean, Rome, etc. And there was what Ann Stoler has called an "imperialist nostalgia" and a fascination with ancient ruins, as if Britain/US were heirs to the legacy of Athens and Rome. You can see elements of this in the turn of the century popularity of Theosophy/spiritualism, or the 1920s revival of "classical" fashions. This historicism also popularized a sort of "linear narrative" of history/empires, reinforced by simultaneous professionalization of anthropology, which insinuated that humans advance from a "primitive" state towards modernity's empires.

-- Meanwhile, from the first decades of the nineteenth century when Megalosaurus and Iguanodon helped to popularize fascination with dinosaurs, Georgian and later Victorian Britain became familiar with deep time and extinction, which probably contributed to British anxiety about extinction, imperial collapse, lastness, and death.

-- Simultaneously, the massive expansion of printed periodicals allowed for sensationalist narrativizing of science.

-- The masking of the cruelty in a euphemism like "land improvement". Like sentencing someone to a de facto slow death and deprivation in a prison but calling it a "sanatorium" or "reformatory". Or calling the mass amounts of poor, disabled, women, etc. underclasses of London "unfortunates". Whether it's Victorian Britain or early twentieth century United States: "Our empire is doing this for the betterment and advancement of all mankind."

-- If an ecosystem is conceived as a machine, "land improvement" actually means monoculture, high-density production, resource extraction, concentration.

-- The image depicts the body is itself is also a mere machine (dehumanization, etc.). And if human bodies are shown to be also systems, networks, machines like an ecosystem, then human bodies can also be concentrated for efficiency and productivity (literal concentration camps, prisons, factories, company towns, slums, dosshouses, etc.). This is the thinking that reduces humans and other creatures to objects, resources, to be concentrated and converted into wealth.

And so after the rise of railroads and coal-power and industrial factories in the earlier nineteenth century, the fin de siecle and Edwardian era then saw the expansion of domestic electricity, easier photography, telephones, radio, and automobiles. But you also witness the spread of mass imprisonment, warplanes, and machine guns, etc. And in the midst of this, the Victorian/Gilded Age also saw the rise of magazines, newspapers, mass media, pop-sci stuff, etc. So this wider array of published material, including visual stuff like maps and infographics could "win over" popular perception. This is nearly a century after the Haitian Revolution, so more and more people would have been able to witness and call out the contradictions and hypocrisies of these "civilized" nations, so scientific validation was important to empire's public image. (Think: 100 years prior, everyone witnessed widespread revolutions and slave rebellions, but now the European empires are still using indentured labor, expanding prisons, and growing even more powerful in Africa, etc. An outrage.)

Illustrations like this ...

It's people with power (or people with a vested interest in these institutions, people who aspire to climbing the social ladder, people who defend the status quo) looking around at the general state of things, observing all of the cruelty and precarity, and then using scientific discourses to concede and say "this was inevitable, this was natural" and not only that, but also "and this is good".

Related reading:

Peoples on Parade: Exhibitions, Empire, and Anthropology in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Sadiah Qureshi, 2011); The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856 (Ralph O’Connor); "Science in the Nursery: the popularisation of science in Britain and France, 1761-1901" (Laurence Talairach-Vielmas, 2011); Citizens and Rulers of the World: The American Child and the Cartographic Pedagogies of Empire (Mashid Mayar); "Viewing Plantations at the Intersection of Political Ecologies and Multiple Space-Times" (Irene Peano, Marta Macedo, and Collette Le Petitcrops); “Paradise Discourse, Imperialism, and Globalization: Exploiting Eden" (Sharae Deckard); "Forgotten Paths of Empire: Ecology, Disease, and Commerce in the Making of Liberia's Plantation Economy" (Gregg Mitman, 2017); Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination (Ann Laura Stoler, 2013)

Fairy Tales, Natural History and Victorian Culture (Laurence Talairach-Vielmas, 2014); Mining the Borderlands: Industry, Capital, and the Emergence of Engineers in the Southwest Territories, 1855-1910 (Sarah E.M. Grossman, 2018); Pasteur’s Empire: Bacteriology and Politics in France, Its Colonies, and the World (Aro Velmet, 2022); "Shaping the beast: the nineteenth-century poetics of palaeontology" (Talairach-Vielmas, 2013); In the Museum of Man: Race, Anthropology, and Empire in France, 1850-1960 (Alice Conklin, 2013); Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity (Pratik Chakrabarti, 2020)

90 notes

·

View notes

Note

i am so c o n f u s e d

ive been seeing u reblogging/talking abt the gilded age among a couple others of ppl I follow/talk abt JA and like............ITS LOOKS PRETTY. SEEEMS LIKE ITS A VICTORIAN ERA THING WHICH IS NICE. but but would it be as inapp as bridgerton?? I can just skip through fucking scenes so I can look at the prett dresses but if theres outright fucking itd be age inapp BUT I need smth to watch while crocheting and this seems like the perfect kinda trashy show to watch

so so as a person whos seen it like should i watch it or not? 😭😭

It’s set in 1882 in the first season and 1883 in the second! It’s very mild, in terms of sexual content. Clothed making out between George and Bertha Russell and then in the second season their son has an ill-advised fling with an older woman that results in them making out while fully clothed and a scene of them chatting in bed while under the covers. I think the most you see is Laura Benanti’s bare leg. ETA: there is a scene in the first season where one character tries to seduce another by being naked in his bed but he gets real mad and immediately makes her get dressed and leave.

It’s a lot of fun, but admittedly it’s fun for me for some very specific reasons. If any of these resonate with you, I’d give it a shot:

1) great costuming

2) nearly every contemporary Broadway star is there to chew on scenery, be witty, and wear hats

3) ridiculous gilded age nonsense where ultra-rich robber barons and “old money” New Yorkers fight over who gets invited to what party. The overarching plot of the second season is about the construction of the Metropolitan Opera House

4) neat subplots featuring genuinely cool female historical figures who accomplished an incredible amount given the societal constraints under which they existed. Last season there was a long subplot about Clara Barton founding the Red Cross and this season there’s a subplot about the female engineer who was actually responsible for constructing the Brooklyn Bridge instead of her husband

5) fantastic scenery

6) a look at the Black elite of New York at the time— a group I didn’t know much about until this show

7) Nathan Lane giving one of the strangest and funniest performances of his long and varied career.

8) on location shooting at big Gilded Age mansions in New York State and in Newport, Rhode Island. The house belonging to the character played by one of my fave Broadway prima donnas, Kelli O’Hara, is actually Lyndhurst House, the actual Gothic Revival mansion of actual Gilded Age robber baron Jay Gould.

9) an insanely high props budget that they use to buy such outlandishly delightful things as penny-farthing bicycles and magic lanterns

Is it a good show? Honestly, I don’t know if I can answer that question.

Is it great if you’re a musical theatre fan who enjoys being able to say, “oh my god that’s Douglas Sills from The Scarlet Pimpernel and Little Shop of Horrors playing the Russell’s chef!” Yes.

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

i remember you saying that you did a lot of research for gfs, and lately i've been thinking of writing a more historical story so i was wondering if you had any tips for thoroughly researching a specific time period? literally anything will help, i'm horrible at research lol

i have a normal and logical level of love for research. I am not absolutely gleeful over this question to an amount far higher than normal. i am NOT--

yeah no i love this question

SO. I am going to answer the question that writers everywhere cry themselves to sleep over (probably) (maybe)

How The Fuck Do I Research Stuff For My Story? (Specific Time Period Edition)

1: know it's not just one thing.

you're not just "researching". That's a big, big umbrella that holds a LOT of things inside of it. You're researching clothing, politics, economic state, government, food, weapons, societal values at the time, and significant going-ons, among other things. It's better to break that into pieces than to try and tackle "research" as a whole.

Also: HAVE A RESEARCH DOCUMENT. Seriously. Write down anything that could be relevant. Also, have a table of contents or something similar and keep it organized. It helps, trust me.

2: Now, here's your pieces. Go in order.

1) ERA IN GENERAL.

So, you've told me (thanks to my frantic asks to you) that your story in particular is around the 1880s-1900s and takes place in the USA, Britain, France, and Japan. That means your story will exist in the gilded age (rich people! but also poverty), the very end of the Victorian era (she lived so fuckin long bro), the formative years (wooo France is full of communists) and the Meiji period (Japan gets to be powerful!).

No but really you picked a bunch of very.... interesting eras to collide all at once in your story skdjfskjfhk

In general, when it comes to researching the era, you want to look at the big picture of what was going on. You can first search "what era was [time period] for [country]", and then once you have the name of it, go wild: e.g. with the gilded age, you can go "advancements in the gilded age" "politics in the gilded age" "social issues in the gilded age" "the gilded age", and so on and so forth. Put the era's name in your search and you'll find results a lot quicker.

Era will include the economic state, political state, significant historical events before/after (aka events that have influenced your age or that are being influenced by your age), what the era is generally known for, advancements at the time, and relationships with the other countries your story is focusing on.

2) EVERYDAY THINGS AND/OR VERY IMPORTANT THINGS.

Food, fashion, common jobs, family structure, architecture & buildings, societal views, and other things that are addressed almost every day in some way. This is where you want to take the societal positions of your characters into your mind; a poor Jewish immigrant man and a high-class young white woman are going to have very different lives, even if they both live in NYC in the USA's Gilded Age. They'll eat different food, wear different clothes, be expected to have different skills, have different cultural beliefs/practices, have different jobs, and likely have very different political views.

So, when looking things up, think whether or not your characters would actually have that in their lives. There are people in ballgowns and people in rags, and you've got to figure out which one your character will be wearing.

Don't just research something like "1890s clothing". You want to find what is worn in that age by the types of people your characters are. So, "what did people wear in the victorian era" is a bad thing to google and expect precise results. "what did poor men wear in the victorian era" is a lot better.

Now's the time to do your research for some really big things, too. Say you have a scene that happens in a mansion in America, and it's a SUPER IMPORTANT SCENE. You're going to want to look up what American mansions in the Gilded Age often were like beforehand, even if none of your characters live in one or will have seen one beforehand.

3) MUCH MORE SPECIFIC THINGS.

Ok, so you know what a rich woman in the Meiji period would wear every day. Cool. But do you know what she should be wearing in that one scene with the super fancy event? Do you know what music would be playing? Do you know what weapon she could best have in that event?

It's ok if the answer is "no", even after your general research. Specific research is best saved for when you have to know it. Getting bogged down in research is a real thing, and it's very, very frustrating. So, either look those details up when you outline the scene (if you outline it) or when you actually need to write it. Like, say your characters end up in Paris in 1888 for a scene or two. Well, that's when the Eiffel Tower was built! You knew that already, because you looked up 1880s-1900s France and know quite a bit about it!

... what you don't know yet is what the construction site of the Eiffel Tower looked like. And that's fine--it's until it's time to actually focus on that scene.

3: Make Sure Your Sources Are Legit.

This can be hard, but in my experience, good sources will 1) list their sources and not try to hide them or just not have any, and 2) their information will agree with the info in other good sources. Basically, if 4 sources say XYZ and 1 says ABC, you can probably believe that ABC is wrong.

(Reading published books can help with this, though they're not always true, either. Basically: compare, compare, compare.)

4: Know This Takes Time.

It's ok to look at this and go "haha.... maybe I won't write anything historical". It's daunting! It can be a lot!

But it's all just pieces.

You read a couple articles and watch a video about clothing worn by Japanese peasants. You borrow a book that talks about food in the Gilded Age. You get lost down the rabbit hole of Victorian high-society politics. You write it all down in that trusty research doc.

And suddenly, you KNOW THINGS. You know things!! And videos that hinted at X but didn't quite talk about it lead you to researching X, which hints and Y and leads you to research Y, and so on and so forth.

It takes a long time, definitely. You'll be researching before you write, while you outline, and when you're writing. You'll research when you're editing and rewriting, too. But even if you don't particularly like it, you can find comfort in the fact that it just involves searching the right phrases and sitting down to watch some videos or read a library book. And in the end, you'll have a well-researched story--and that info doesn't go away! If you ever have to know something about the Victorian age, you'll be able to look back at what you learned awhile back. (Especially because you have your research doc, right?)

5: TLDR.

know research isn't just one clump, it's a lot of different things you look at

research the era, then general things, then things you need to know in specific situations only

use specific phrases, not just general things; "what jobs did men have in France in the 1880s" is lots better than "French jobs"

make sure your sources aren't just people lying on the internet for fun. comparing what your sources say and using a lot of them can help with this!

know it takes time, but don't stress. You don't have to get it done all at once.

have your motherfucking research doc. are you listening to me. WRITE DOWN THE INFORMATION THAT YOU FINDDDDDD

OK. This was a SUPER long post, but!! I really hope it's helpful!! If you have more questions, feel free to ask away :D

#researching#writblr#writeblr#nico yells writing advice into the void#long post#asks#luce!#i am. so sorry#i cant shut up </3

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Note: I've linked StoryGraph summaries of every book to each title.

The Duke Gets Even by Joanna Shupe

There was a lot of reasons The Duke Gets Even worked as well as it did and I can split it between the relatability factor and the hotness factor.

Because it's set in Gilded Age America, the language is definitely more accessible for first-time HR readers. Even content-wise, the heroine, Nellie, becomes a birth control advocate which comes at a... very fitting time for us here in the United States. She also harbors fears of losing herself to a man if she were to get married, all while being in that position where she's the only single in her friend group. Super relatable.

What is less relatable is just how off-the-charts the chemistry between Nellie and the Duke of Lockwood is. We know it's slowly building in the last 3 books but watching it implode is glorious. I don't know if this is a trend but Lockwood seems to written in the mold of the "new" HR hero, similar to MacLean's Duke of Clayborn, where they give and take in equal measure: sexually (in this case, a bit of pain), and perhaps they even give a little more emotionally in the beginning. They respect their heroines in that they have a deep understanding of what makes them tick, but obviously "respect" doesn't mean they aren't willing to get down and dirty. And when they do, it's GREAT.

Also, because of all the water imagery in this book, I'd recommend listening to the Moonlight soundtrack by Nicholas Britel while you read (try The Middle of the World).

Her Husband's Harlot by Grace Callaway

January has been my Grace Callaway month and I was endlessly delighted as I read every HR she's ever published. This was the first book I read by Grace (who is an Asian Canadian author btw), and it's exactly the sort of deranged nonsense I live for: a bit o' rough self-made hero elevated to the aristocracy, a genteel heroine he falls for immediately and marries, but he panics on their wedding night that the d was too big and he was an animal with her, so he goes to slake his lusts at a brothel with a harlot except, well, guess who the "harlot" is. It's great. 10/10 would recommend.

Fiona and the Enigmatic Earl by Grace Callaway

I was reaching the tail-end of my Callaway marathon when I hit this book and wow... I did not expect to be shook further by Grace. Not only did I enjoy the "investigative services for women" plot, but the couple, Fiona and Hawk, had excellent chemistry even as they ostensibly start off as having married out of "convenience".

There's too much to list but here are a few highlights: "oh no I'm too sore so mutual masturbation it is", One of the best carriage blowjob scenes, in part because he's *standing*, he performs a Clayborn (iykyk), there's a Victorian sex toy store, and there is a dungeon(s) in the toy store with an alter on which our heroine is "sacrificed".

What I Did for a Duke by Julie Anne Long

You can read the summary above⬆️ but let me take this opportunity to wax a rhapsodic on what worked for me in this book:

First, it features a hero hellbent on *revenge* for being cucked. Which is great. The *revenge* involves seducing the sister of the man who cucked him. Also great.

Listen... Alexander says some hot shit. And the reason it's hot isn't even because it's the dirtiest stuff; it's because Genevieve takes in his words and internally goes haywire, and any suggestiveness in Alex's words is not lost on her. She's a Knowing virgin, if you will. They're also usually the two smartest people in the room which makes for great dialogue suffused with barely-restrained sexual tension. Alex is also a very real hero, if that makes sense. He makes dumb jokes after having sex. He can't resist trolling his future brother-in-law. His grief is not over-the-top, but a quiet thing, and all the more moving for it.

Side note: @viscountessevie (Sahara), @jeanvanjer (Z), and I did, in fact, debate whether or not Alexander was daddy (the answer is no).

The Legend of Lyon Redmond by Julie Anne Long

The "Love at first sight" trope can easily be written in a trite, boring way, but Julie wrote it brilliantly here. The book alternated between flashbacks and present-day so we got the full picture of Lyon and Olivia's early relationship (in all its, ah, young adult glory. See: below). We also see them as older and fairly jaded and world-weary, which makes their reunion all the more moving and romantic (and hot. very hot).

It was an emotional book overall, and Z and I found ourselves crying for unexpected characters, to say the least.

The Counterfeit Scoundrel by Lorraine Heath (Releases on Feb 21st)

For the full (funny) story on how I got an early copy, see here.

This was very much a *thinking* book. Ever since I started writing as certain dark things are to be loved almost two years ago, I've always been on the look out for books that basically show that fight for women's rights neither began nor ended with suffrage. I appreciate this book because it delves into how much more difficult it was for women to be granted a divorce historically, and gives a fictionalized take on the lengths women might be willing to go to in order to get a divorce. Make no mistake, Blackwood and Daisy's relationship is very very romantic, but I think by the time I finished, I felt like the history was the main draw for me.

A Daring Pursuit by Kate Bateman

The classic familial enemies-to-lovers book. Also, it's very rare to see HR set in Wales, which I did appreciate. Anyway, "enemies" Carys (a proper Welsh name, according to Rhys Winterborne) and Tristan decide to have an affair so Carys can see what she's missing out on in the marriage bed. As it turns out, A Lot despite her thinking otherwise because of a bad first time. Obviously this gives our hero a chance to be all "he didn't do this for you??" It's all very fire-and-ice until they find themselves in over their heads with all their Feelings, especially Carys.

There is a very primal sex scene post bear-chase, and if that doesn't compel you to read this book, I don't know what will.

#trivia's book round-up#january 2023#julie anne long#lorraine heath#historical romance#grace callaway#kate bateman#joanna shupe#sarah maclean#bridgerton#book recs

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The miracle of the monarchy is how it has survived in a democratic and egalitarian age. Everything it stands for — inheritance rather than merit and ascription rather than election — is the antithesis of everything we hold dear as a civilization. Yet the British monarchy has not only survived, it has thrived. It’s made none of the compromises of the bicycling monarchies of the Scandinavian world. Indeed, it has almost relished defying compromise.

(…)

Bagehot thought that statecraft was far too serious to be left to the masses. Rather, government needed to be left to a tiny elite of serious-minded men who understood the world. But how could you get the people to accept such a situation in a democratizing age? The answer lay in distraction by means of monarchy. Bagehot hoped that the people would focus on the splendid royals in their gilded carriages, leading the great parade, while “the real rulers are secreted in second-rate carriages.” “No one cares for them or asks about them, but they are obeyed implicitly and unconsciously by reason of the splendor of those who eclipsed and preceded them.”

Bagehot also replaced the individual with the family at the heart of his drama. This was part of his distraction strategy. As he saw it, regular people — particularly women — cared 50 times more for a marriage than a ministry. Distraction also doubled as legitimacy: People were far more likely to obey a state with a human face than one that was a mere abstraction. By providing ordinary people with brilliant editions of universal facts — such as birth, marriage and death — the Royal Family also anchored the business of government in regular human affairs. It was part of an embourgeoisement strategy.

In Bagehot’s schema the royal family was to be transformed from a relic of aristocratic society into an embodiment of bourgeois virtues. Victoria’s job was to be both Empress of India and the acme of companionable marriage. The monarchy remains physically Victorian. The palaces and their decorations reflect the tastes of the queen-empress. The great events continue in their Victorian incarnations. The ceremonial uniforms of the guards are as Victorian as Gilbert and Sullivan operettas.

But Elizabeth II had to abandon Bagehot’s handbook and invent a new one all of her own. Nobody today believes that the Queen ruled as well as reigned — and if they did they would have rightly demanded change. The idea that monarchy is essentially a show is taken for granted. It is a distraction in the sense of a diversion rather than a disguise.

(…)

The Queen’s genius was to understand that monarchy provides not distraction but a counterbalance to the imperatives of modern life. Clever courtiers like to emphasize the way she moved with the times and modernized the Firm, as she liked to call it. “Everything’s changed except the headscarf,” says one, leaving aside such little things as Windsor Castle and Balmoral. The Queen grasped Edmund Burke’s great dictum that, for a true conservative, the point of change is to stay the same, at least in the things that really matter. Monarchy is a restraint on modernity or it is nothing.

The Queen’s most obvious achievement was to provide an element of continuity in a world that is in a fever of change. Liberal capitalism has taken the principle of creative destruction to the Nth degree — not only through the creation and destruction of companies but also through the constant reordering of daily life (whenever you think that you have learned how to use electronic banking, the rules change and you have to master a new system). Yet the populist alternatives to liberal capitalism are all exceedingly ugly, from the jingoism of the far right to the criminal kleptocracy of Vladimir Putin.

The Queen embodied the civilizing power of tradition, which counterbalances change without resorting to the bloviation of outright reaction. Robert Hardman, perhaps the most perceptive of Britain’s strange tribe of royal watchers, puts it well: “She is the living incarnation of a set of values and a period of history. In Britain, she is Tower Bridge and a red double-decker bus on two legs, not to mention Big Ben, afternoon tea, village fetes and sheep-flecked hills in the pouring rain. In the wider world, she is the newsreel figure who just has carried on going into digital high definition.”

(…)

The Queen lived a life of duty in an age when duty is going out of fashion. The meritocratic elite that has come to dominate the world since Elizabeth came to the throne is estranged from the world of duty and service. Believing that they owe their position to merit rather than luck, they think in terms of what the world owes them rather than what they owe the world. And living in the global economy, they don’t have any time for local ties and obligations.

(…)

Her commitment to duty went along with an unfailing air of dignity. Again this is a counterbalance to an increasingly demotic world in which a reality TV star can become president of the United States, a man who has repeatedly been sacked for lying can become British prime minister, and the airwaves are increasingly dominated by bellowing maniacs. The Queen was the focus of an alternative world in which everything was in its place and there is a place for everything — an ordered world but also a world in which there is plenty of room for nurses and carers as well as diplomats and dignitaries, a quiet world in which shouting is banned and words are few and well chosen.

We have been hard on Bagehot and his notion of the monarch as a distraction. But just as central to his argument is the idea that the British constitution is based on a distinction between the dignified branch of government and the efficient branch. The dignified constitution refers to permanent institutions that exist in a sort of Platonic ideal world. The efficient part belongs to the impermanent world of politicians and their struggles for power. The Queen’s job was to embody the first while ultimately bowing to the second. She had to read out the agenda of the government of the day and, at the same time, embody the dignity of the state.

(…)

There will be much talk of the future of the monarchy in coming months as the first shock of the Queen’s death fades. This division of powers has surely become more, rather than less, important in recent years as the culture wars have raged and tempers have flared. America’s belief that the president is both a political actor and the head of state was profoundly tested by the Trump presidency. In Britain, it is possible to loathe Liz Truss or Keir Starmer but still happily participate in state functions. The Queen pulled off a remarkable trick in preserving a monarchy that was simultaneously majestic and apolitical. It is a measure of her achievement that the new monarch will be largely judged on his ability to pull off exactly the same trick.

The Queen is dead. Long live the King.”

“Monarchs, if they have enjoyed particular significance, are sometimes accorded the honour of an 'age'. Victoria, Edward VII, the Georges – their 'ages' would all come to define not just a period of time but a culture, a mindset, even a style of architecture.

But history will note that there was one sovereign whose reign defied any such categorisation. Because the reign of Queen Elizabeth II simply spanned too much.

Whole eras came and went on her watch. She had steered her nation through the Jet Age, on through the Space Age and was well into the Digital Age when her unsurpassed stewardship of the Crown came to an end.

(…)

Elsewhere, however, Queen Elizabeth II represented stability on a staggering, enviable scale. Her coronation would predate their constitutions, their national anthems, their flags and their currencies. She was history made flesh.

(…)

And therein lay perhaps her two greatest attributes – her sense of duty and the sense of continuity which prevailed all through her reign. Whatever the crisis – personal, familial, national or global – Elizabeth II was the embodiment of the old wartime adage, 'keep calm and carry on'.

(…)

One well-known British political commentator, whose family had come to Britain as refugees, liked to quote his grandmother's wise maxim: 'As long as the Queen is safe in her palace, I'm safe in my flat in Hendon.' But all this would rest on far more than stoicism and longevity. For this unchanging, utterly unspun world figure would actually change the institution around her more than any monarch in 100 years.

Not even George V's creation of the House of Windsor, to replace the Germanic House of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha at the height of the First World War, was as radical as the internal revolution that his granddaughter would bring about.

The other great Queen of modern history, Victoria, would do her best to withdraw from an ever-changing world. Elizabeth II would always ensure that she moved with it.

(…)

But the monarchy was already well down the road to reform. Back in those contented times in the mid-Eighties, a wise new Lord Chamberlain (de facto chairman of the Royal Household) had arrived in the form of the Earl of Airlie.

A shrewd former banker, he could see that the entire organisation was in dire need of internal reform. The Royal Household was living beyond its means and its staffing arrangements, like its ethos, had barely changed since the turn of the century. And it was depending on an arbitrary annual handout from the Treasury, the Civil List, which dated back to the 19th century.

Lord Airlie took his concerns to the Queen who authorised a top-to-bottom investigation. The subsequent report, stretching to well over 1,000 pages, covered everything from boilers to uniforms to pensions. The Queen then told Lord Airlie and his team to implement it all and that he would negotiate new terms with the Treasury.

The reforms caused mayhem at every level inside the Palace, not least when the five separate tiers of the staff dining restaurant were knocked in to one. But the costs fell and Mrs Thatcher's government, along with the Opposition, agreed to fix the Civil List at £7.9million a year for ten years.

When that time was up, the annual costs were under such tight control that the same fixed rate was applied for another decade. As a result, the Queen would run the only arm of the state which performed the same role on the same budget for 20 years.

Long before the question of royal taxation had become an issue, Lord Airlie had initiated discussions with the Inland Revenue on that score, too. When, in 1993, it was confirmed that the Queen would pay regular income tax, the media portrayed it as a victory for the critics. In fact, it was virtually a done deal anyway.

(…)

Two trends would emerge in the later stages of the reign: the Queen wanting younger faces at royal events and her greater emphasis on issues of faith.

The Queen would always prefer to hear young people explaining what they were doing now or next rather than her contemporaries reminiscing about the past. A royal itinerary would always be more likely to opt for the school over the town hall. The Queen was the first Supreme Governor of the Church of England in history to visit the mosques and temples of other faiths and to welcome a Pope to Britain. And a study of her Christmas broadcasts is telling.

As Britain became a more secular society, so her annual message became more overtly religious in tone. Over time, she would be the only major public figure who could talk about God without fear of ridicule or mockery. Her faith was uncomplicated, unswerving and reaffirming.

(…)

Having sworn to protect the Church of Scotland (it has no 'Head'), the Queen was a much-loved member of the church community at Crathie Kirk, the small church next to the Balmoral estate. Few parishioners could match her knowledge of a place where she had worshipped since she was a small child. Though it was seldom remarked, the Queen was the most Scottish monarch since the Act of Union, being twice descended from Robert the Bruce on her (Scottish) mother's side.

(…)

A special office inside Buckingham Palace was opened to ensure that royal engagements were more efficient and targeted. Called the Co-ordination and Research Unit, it would go out of its way to find sections of the community which had less exposure to the Royal Family. Military organisations or counties such as Berkshire were never short of royal visits; ethnically mixed inner cities less so.

Steered by her advisers, the Queen quietly amended her own job description.

For as long as anyone could recall, the monarch's position was Head of State and his or her role was laid down in Walter Bagehot's 1867 English Constitution.

During the Nineties, the Queen quietly added a new title to official royal publications – Head of the Nation. This covered all the unspecific but crucial roles of a modern monarch: promoting excellence and voluntary service, fostering national unity and so on. It was bolted on to the royal website, another innovation which the Queen endorsed.

(…)

The Commonwealth was in its infancy when she came to the throne. Just three years old, it had eight members. By the time of her Golden Jubilee, it had more than 50 member states and spanned every continent, every major faith and up to a third of the world's population.

As a child, she was expected to inherit the British Empire. But a post-war Empire wanted to go its own way, led by India and Pakistan. That nearly all the colonies of the Empire would soon opt for independence yet remain part of this post-imperial club was largely down to the unifying (and glamorous) figure with the honorary title of Head of the Commonwealth.

During her reign, she would visit almost every part of it, often several times. Many Commonwealth nations, from Australia and Canada to Belize and Barbados, would opt to keep her as their head of state long after independence. Others, such as Kenya or Trinidad, would opt to become republics. But no one ever doubted that the Queen should be the symbolic figurehead of the Commonwealth itself.

(…)

The Queen's dedication to the organisation was beyond doubt, however. Many diplomats have claimed that the whole thing would have fallen apart without her uniting influence.

At the same time, the Commonwealth was gently reshaping British society through the arrival of workers from former colonies to help rebuild post-war Britain.

By the midpoint of her reign, Britain was well on its way to becoming the multi-cultural society we have today.

(…)

No one did more to put the U into UK, yet her kingdom was seldom completely united about anything during her unrivalled 70-year reign. Such is the nature of a true democracy.

But it will surely be united now – in the grief that is, indeed, the price we pay for love.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Today in Black Military History, the Americas between 1880 and 1914:

Today in Black Military history covering major events of the Americas between 1880 and 1914. The first case is a specific choice of historiography with one look at the more positive aspects of the legacy of the Buffalo Soldiers, one more negative, and then one focusing specifically on the broader aspects of the segregated US military that lasted until the Truman Administration.

A key point with this is that in certain ways the military both embodied elements of society around it and in certain ways there were specific rhythms to the actual realities versus how memory would otherwise have them. The United States Colored Troops forces formed in the War of the Rebellion endured through the Gilded Age and into the era of the World Wars.

What this meant in practice is that along with the cowboys being much Blacker than historical memory and movies made them out to be, so were the soldiers in the West. Black soldiers fought in the Cheyenne and Apache Wars, and shared with their fellow soldiers the unlovely experiences of garrison duties and the bitter shabby sequences of violent genocidal spasms of war between the imperial power of the United States and the individual bands of Indigenous peoples who were the last holdouts against it.

To be still more blunt, in this as in other things for the Black people who welcomed this, like this article says, it mattered greatly that Black people were allowed to participate in even a limited sense. That it was there at all mattered more than what it was, for if it was not this, it would be nothing. This is one of the bits of Victorian-age realpolitik that later generations have rather more choices with.....and which would help in the longer terms to store up all the problems that would come home to roost in the Vietnam War.

#lightdancer comments on history#black history month#military history#us history#gilded age#indian wars#buffalo soldiers

0 notes

Text

Illuminating the Past: The Hierarchy of Vintage Lamps in the USA

Collectors, home decorators, and lighting lovers appreciate the special character and classic allure of the vintage lamps. These glowing antiques are a window into the artistry and fashion of another period. The American lamp hierarchy is a fascinating exploration of design, nostalgia, and American history.

Oil Lamps: An Early Technology

Oil lamps are the lowest-ranking vintage lamps. These lamps were used in American homes during the 19th century and date back to the early years of the country's independence. Oil lamps served their purpose, were easy to make, and occasionally displayed excellent craftsmanship. The use of antique oil lamps nowadays is a nostalgic throwback to the days before widespread access to electricity.

Aladdin Lamps: The Next Generation

Significant progress in lamp technology may be traced back to the introduction of Aladdin lights in the early 20th century. The luminous efficiency of these paraffin lights won widespread acclaim. Due to their unique appearance and high-caliber illumination, Aladdin lamps have become sought-after collectibles. In places where power was rare, they enhanced residents' quality of life.

Tiffany Lamp: An Iconic Icon in Stained Glass

As we ascend the social ladder, we reach the exquisite Tiffany lamps. The beautiful stained glass designs made famous by Tiffany, an American artist, ushered in a new era in lamp design in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These lights are well-known for their elaborate patterns, vibrant colors, and organic inspiration. Because of their association with wealth and prestige, Tiffany lamps are widely prized and fetch great prices on the vintage lamp market.

Art Deco Lighting: the Jazz Age

The Art Deco style, popular in the 1920s and 1930s, introduced a new refinement and modernity to the lighting industry. Art Deco lights are distinguished by their streamlined silhouettes, geometric patterns, and glamorous aesthetic. Collectors with a taste for all things Jazz Age will find great value in these lamp shades as they perfectly capture the spirit of the time.

Mid-Century Lamps: an Enduring Icon

The post-World War II era saw the emergence of Mid-Century Modern architecture and interior design, which prioritized practicality and minimalism. Designers such as George Nelson, Isamu Noguchi, and Arne Jacobsen are responsible for iconic lights that flawlessly combine form and function. Because of their enduring style, Mid-Century Modern lamps are widely sought after in the modern antique market.

Victorian Parlor Lamps: the Elegant Companion

Victorian parlor lamps perfectly exemplify the generosity and extravagance of the Victorian era. These vintage lamps were made to be the focal points of living rooms. Therefore, they typically feature elaborate metalwork, porcelain, and hand-painted glass shades. Collectors value these lamps because they are beautifully crafted and intricately detailed, evoking the spirit of Victorian design.

Lamps with a Hollywood Regency Flair

Popularized in the middle of the twentieth century, the Hollywood Regency aesthetic aims to capture the glamor and sophistication of the silver screen. Ornate, gilded highlights, and striking motifs are typical of lamps in this era. They are highly sought after because of their retro appeal to modern decor.

Lights from the Atomic Age: Looking to the Future

The time following World War II and the beginning of the space age, known as the Atomic Age, influenced lamp design with futuristic and space-inspired patterns. Lamps from this era are often minimalist and incorporate space-age materials and design touches like Sputnik-inspired arm extensions. They evocate the era's boundless hope and enthusiasm for new technologies.

Final Words

In conclusion, the hierarchy of vintage lamps in the United States reflects the long and varied tradition of lamp making and the many different aesthetic considerations that have shaped it. Each era has made its stamp on the world of antique lamps, from the practical simplicity of oil lamps to the ornate grandeur of Victorian parlor lights and the evergreen charm of Mid-Century Modern designs.

These illuminated artifacts are still highly prized by collectors and enthusiasts, who value them for the light they provide, the history they preserve, and the artistry they represent. Discovering the history of lighting is fascinating, whether you're a collector or just interested in the past.

Visit Us, https://www.fenchelshades.com/

Original Source, https://bityl.co/LgtU

0 notes

Text

7 BEST Things to Do in Richmond

Richmond, Virginia, is a city steeped in history and culture. With its vibrant arts scene, historic landmarks, and beautiful outdoor spaces, there's a wealth of experiences to enjoy. Whether you're a history buff, foodie, or outdoor enthusiast, Richmond has something for you. And remember, if you encounter any personal injury issues during your visit, don't hesitate to seek guidance from a Richmond personal injury lawyer.

1. Visit the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts is home to an impressive collection of art from around the world. From ancient Egyptian artifacts to modern American art, there's something to interest everyone.

2. Explore the American Civil War Museum

The American Civil War Museum offers a comprehensive look at the Civil War from multiple perspectives. Its exhibits explore the experiences of the Confederate and Union sides, African Americans, and the civilian population.

3. Stroll Through Maymont

Maymont is a beautifully preserved Victorian estate that offers a glimpse into the Gilded Age. The property also includes a nature center, Japanese and Italian gardens, and a wildlife exhibit.

4. Enjoy the Richmond Food Scene

Richmond's food scene is a culinary adventure. From Southern comfort food to international cuisine, the city's restaurants, bakeries, and food markets offer a feast for the senses.

5. Visit the Virginia State Capitol

Designed by Thomas Jefferson, the Virginia State Capitol is a National Historic Landmark. Take a guided tour to learn about the building's architecture and the history of Virginia's government.

6. Explore the James River Park System

The James River Park System is an oasis of outdoor adventure. Enjoy hiking, biking, or kayaking, or simply relax by the river and take in the stunning natural beauty.

7. Visit the Edgar Allan Poe Museum

The Edgar Allan Poe Museum celebrates the life and work of one of America's greatest writers. Explore exhibits on Poe's life, his famous works, and his influence on literature.

While enjoying the sights and experiences of Richmond, if you face any personal injury challenges, it's essential to contact a trusted legal professional. A reliable personal injury lawyer Richmond can provide you with the necessary assistance and guidance. For directions to their office, you can refer to this map.

In conclusion, Richmond is a city that's rich in history, culture, and natural beauty. With its diverse attractions ranging from world-class museums to delectable cuisine and beautiful outdoor spaces, it offers a unique and memorable experience for every traveler. So, start planning your trip to Richmond today and get ready to create some unforgettable memories.

Business Name: Breit Biniazan

Address: 2100 E Cary St Suite 310, Richmond, VA 23223, United States

Phone: +18043519040Website:https://www.bbtrial.com/richmond/ GBP URL: https://goo.gl/maps/M3KwpReqMFLtsbw99

#injury attorney#injury lawyer#injury#motorcycle accident lawyer#pedestrian accident#vehicle accident attorney#bicycle accident attorney#virginia beach#Breit Biniazan

0 notes

Text

[ad_1]

History was told on the 2022 Met Gala red carpet, and the best dressed celebrities carried the message. Among them, Sarah Jessica Parker left her mark in a striking Christopher John Rogers gown. The "And Just Like That" star wore a Victorian-inspired, off-the-shoulder frock with a sweetheart-neckline corset and a pleated ballroom skirt in charcoal shades.

Her ivory silk faille and silk moiré design recalled a "three-piece cape and gown ensemble" the late Mary Todd Lincoln wore circa 1862, a look that's been credited to an unsung Black seamstress, Elizabeth Keckley. Keckley was born into slavery in 1818, and her dressmaking skills helped her purchase her freedom in 1855. She went on to launch one of the most successful clothing businesses in Washington DC. Braving the long history of racism in the United States, Keckley became the first Black designer to be engaged by the White House. While few, if any, of her creations have been preserved, they were known for their impeccable tailoring and sophisticated design. Parker shared this untold chapter of history at the Met Gala, choosing a Black designer to orchestrate this spectacular moment. She took things up a notch with a dramatic feathered headpiece designed by Philip Treacy, another classic element of Gilded Age fashion.

The "Sex and the City" actress brought style and substance to the event, similar to Gabrielle Union, who paid tribute to the Black and brown people whose labor generated the wealth of the Gilded Age. "When you think about the Gilded Age and Black and brown people in this country, this country is built off of our backs, our blood, sweat, and tears," Union said in a live interview with Vogue. The 49-year-old star accessorized her Atelier Versace dress with a fringe red crystal hair tie to "represent the blood spilled during the accumulation of gross wealth by a few during the Gilded Age."

Appreciate Parker's historic Met gala appearance ahead.

window.fbAsyncInit = function()

FB.init(

appId : '175338224756',

status : true, // check login status

xfbml : true, // parse XFBML

version : 'v8.0'

);

ONSUGAR.Event.fire('fb:loaded');

;

// Load the SDK Asynchronously

(function(d)

var id = 'facebook-jssdk'; if (d.getElementById(id)) return;

if (typeof scriptsList !== "undefined")

scriptsList.push('src': 'https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js', 'attrs': 'id':id, 'async': true);

(document));

[ad_2]

Source link

0 notes

Text

Europe in 1808 vs. Europe in 1893- A Comparison Between the Time of the Tucks and the Time of Winnie Foster

A little while ago, @luluthecatprincess requested that I explore the differences between the social, political, and cultural situations in Europe in 1808 (the Tuck’s original time) and in 1893 (Winnie Foster’s original time). Thank you so much for being patient with me as I collected and organized my sources to write this frankly massive post, and thank you so much for your help in providing me with some of those sources! I hope you (and everyone else) enjoys this.

In 1808, Europe was in the midst of what is now commonly known as the Regency period (often called the Federalist period in the US). In England this particular period is also often called the Georgian period, due to the fact that King George III was on the throne (although not for much longer- his son George IV became regent in 1811 due to his suffering from mental illness and he eventually died in 1820).

This period was characterized by relative simplicity in terms of fashion, as well as a desire for the natural among affluent members of society. It was also a time of great artistic achievements, however, as several famous composers, artists, and authors were in their heyday. Beethoven was probably the most famous composer of the time, but many others including Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s son) were prolific in their writing and publishing of music. As for painters, Joseph Mallord William Turner and Marguerite Gérard were two who had met with great success by 1808. Famous authors included Ann Radcliffe, Maria Edgeworth, and Samuel Richardson. Jane Austen would come along a few years later, publishing her first book (Sense and Sensibility) in 1811.

Despite all this, however, much of Europe was in the midst of turmoil. The Napoleonic wars were raging, and England had only just outlawed the slave trade in 1807. Meanwhile, in Russia Tsar Paul I (son of Catherine the Great) had been assassinated in 1801 (as an interesting side note, the capital of Russia in the early 19th century was St. Petersburg and not Moscow).

The Regency/Georgian/Federalist period was a time of great political upheaval in Europe, and much of that bled over into the new United States and would have directly affected the Tucks. The War of 1812 was a direct result of both the Napoleonic wars as well as England’s kidnapping of American sailors and forcing them to work on British ships, and it eventually led to British troops storming Washington DC in August of 1814 and burning most of it (including the White House) to the ground. Miles, Jesse, or Angus might have indeed fought in the war, and it certainly would have been a defining moment of this period for them regardless.

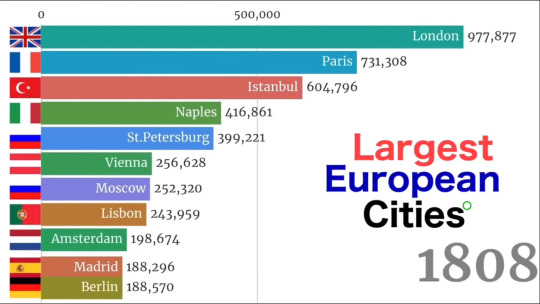

In the decades following the Tucks becoming immortal many, many things happened in both Europe and the United States. Most prominently, the industrial revolution swept across both Europe and the United States, turning what had been primarily agrarian (farming) communities into more urban, industrial societies. This is clearly visible when looking at the populations of the largest cities in Europe in 1808 and comparing them with the populations of the largest cities in Europe in 1893.

Factories were a major contributing factor to the rapid industrialization taking place all over the world (but particularly in Europe and the United States), and Jesse or Miles probably would have likely worked in one for at least a little while in order to make money while traveling the world.

The 1890s marked the end of both the Victorian era (Queen Victoria became queen in 1837 and died in 1901) as well as the end of the “Gilded Age”. The decadence and opulence favored by the upper classes during this time stands in stark contrast to the relative simplicity of the Regency era, although the two periods did have similarities in that major social reforms and political upheaval occurred during both. Striking workers pushed for labor reforms not only in the United States but also in much of Europe, growing resentment among the people of Russia (who in 1893 were under the rule of Tsar Alexander III, although he would die in 1894 leaving the throne to his son, the now-infamous Tsar Nicholas II) would eventually lead to revolution in 1917, and the first entrance of the US onto the world stage caused tension which would eventually lead to the Spanish-American War in 1898.

Despite this (or perhaps because of it) much like in the early 19th century the fine arts were alive and well in the late 19th century. Composers like Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (who died in 1893) produced famous songs still well-known today, artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Vincent Van Gogh (just to name a few) created many of their most famous paintings, and authors like Leo Tolstoy, Oscar Wilde, and Louisa May Alcott (who died in 1888) wrote classics which are still widely read and enjoyed today.

We can only imagine what it must feel like to live through all that the Tucks had lived through by the time they met Winnie Foster, and what it must have felt like to live on after her. Certainly, their immortality was a curse, but they lived through one of the most interesting periods in history and I, for one, find that to be extremely compelling to think about.

Sources:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FJi5LcWpznw&t=735s

https://www.artsy.net/gene/late-19th-century

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/19th_century_in_literature

https://www.britannica.com/event/War-of-1812

#tuck everlasting#tuck everlasting fanfiction#jesse tuck#miles tuck#angus tuck#mae tuck#history#european history#1800s#1890s#winnie foster

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Curiouser and Curiouser: the Mysteries of EtN (reposted from A Personal Analysis of Escape the Night, Chapter 25 of AO3)

Summary

A random plot bunny-ish. Just some things to ponder about.

Season 1

Why was there a Death Note located randomly in a drawer in what was likely a hidden chamber? Is there any context to this in-universe? How does the thing even work?

Season 2

Where is the approximate location for the Victorian mansion? We know that it is the Victorian Era in the UK and a complex series of events (last of most, the Gilded Age) in the US, and a cowboy and a Japanese spider goddess made it through the borders, but are we able to pin down an exact explanation?

A follow-up to the above: at what point in time IS the Victorian mansion located? With a cowboy appearing in the flashback of Episode 3, we can assume that it may have taken place in the Wild West era, but can we pinpoint something more precise? Can the YouTubers' outfits be used to help analyze at least the decade in question? (Since there is a fake booty on Lauren's gown, I will assume that it was the 1870s or the 1890s…)

Is there an explanation for the anachronistic names? After all, Riley was a boy's name in the late 19th century, and I don't reckon it WAS a girl's name before the latter half of the 20th century, even in the 18th century (since the Sorceress used 100 years to perfect her wickedness). Also, what era IS Alison from? It was a popular girl's name in the Middle Ages and is one in the modern years, but 'Alice' would be the closest alternative to her name in the Victorian era.

Season 3

Exactly WHERE is Everlock located? If in the US, which state, at the very least? The news articles in the beginning sequence of Episode 1 gives NO information on the location, and the first article that shows up said that the entire world was shocked, so it gives zero leads, even if a geographically relevant newspaper (e.g. one based in London or whatever city) printed an article about Everlock.

How DID time work in Everlock? Was every single day 13 October 1978? Were the people born in Everlock between the date of official disappearance and the day Season 3 took place technically the same age, regardless of what day they were actually born in? Was it a Groundhog Day sequence that was only broken by the arrival of the YouTubers? Did people AGE in Everlock at all? We can assume that Calliope had not since her arrival, so are the residents of the town older than they actually appeared? And last of the sequence, did Everlock return to modern day society after Season 3, or will they be stuck on 13 October 1978 perpetually and forevermore?

How did the issue with Nicholas and Lucy (his DAUGHTER) work out in the first place? Are they even biologically related? If they are, did they have her after being turned Evil or before? (I'm inclined to think 'after' based on the Episode 9 flashback, but you never know.)

Season 4

Why is Purgatory preserved in what appears to be a 1940s theme? Does WWII have anything to do with this arrangement?

Why did the Collector choose to make Joey's past demons an exhibit in its own rights?

How were the YouTubers taken to Purgatory after death? How did they change clothes and be stuck in a position in the intro/second teaser trailer like wax statues?

How was there a Cursed God totem all the way back in the caveman era?

Can someone please explain the historically incorrect Chinese history for Episode 4? The closest to a rebellion in the timeline of the Ming Dynasty occurring around canon time (1521) took place in 1519, and nowhere near the Imperial capital for the rebels to speak Mandarin Chinese unless they moved there - and why would they head south to Jiangxi in the first place? The southern provinces' bureaucrats were generally those who had fallen out of favour by the Imperial government, and even if this were to be the case, why was the male wearing a queue from the mid-late Qing Dynasty (the last dynasty, which came after the Ming and wouldn't be established for another hundred years at least - and the Manchus who ruled during the era were from the Northeast, not the Southeastern region)?

Is the Black Knight really Mordred from the legends? Why were they wearing metallic armour, when they wouldn't be for another few centuries?

Where were the Pirates from Episode 8 from? Rorik was the name of a Danish Viking (from before even 1000AD) and his name is rarely used, as far as I know. Jezebel is an Ancient Hebrew name, and few in the world even use this Biblical name, as it brings up connotations of wickedness (refer to the Old Testament).

In real life, Velociraptors were only the size of a turkey - did the creators use Jurassic Park for reference? Why did they straight-up EAT their victim (RIP cinnamon roll) instead of say, slashing them to death with their claws (or hasn't that been a very common death throughout the season already, and they needed an obligatory extra-gory-and-traumatizing death scene)? Did the Raptors have feathers in the Episode, as they should have IRL?

The whole mystery regarding the Minotaur's Maze (aka Labyrinth). Isn't it supposed to be a virgin sacrifice of a youngster? Colleen didn't even fit the requirements of the old myths! Or did Purgatory and the Collector find a way to mess with the myths too?

Why was the Gorgon (aka Jael's sister) present in the Ancient Greco-Roman era, according to the Episode 6 flashback? Why was there a ROMAN gladiator when Ancient Greece was the origin era for the Medusa myth? How did she even get to that era?

All Seasons/General

Can we precisely pin down the EtN timeline? We know that Season 2 and 3 took place in between "a couple of months", according to Rosanna in Season 3 Episode 1, but can we find a closer definition?

What happened in real time between the seasons? Were the YouTubers declared dead, or just missing? Leah's choices indeed make sense, but cam we find a more definite, solid real-world impact look?

Exactly how long were the YouTubers gone for, during each round - one night, or longer? If longer, why so? (I propose that it was because the connection between the modern world and the historical era disappeared, for the first three seasons: the time-travelling car was blown up, the carriages disappeared for whatever reasons - probably the Sorceress' meddling - and there was no connection between Everlock and the modern world to begin with, since they arrived by seance.)

Did the YouTubers get erased from existence if they died - that is, would the Unborn Phenomenon side of the Fandom be proven correct?

Couldn't someone have just broken the lock to a puzzle so as to cheat their way through the challenges? Or used a lockpick (even an impromptu one made with a couple of hairclips)?

Exactly how old is the Cursed God, and what are his origins? Does he have a 'normal' name?

When and how was the SAE founded? How do they operate? Were all the deaths in our current series necessary for missions to be completed? I mean, it sounded like it was a norm according to Shane's note back in Season 1 Episode 1, but are there any better alternatives?

Did more Cursed God-related incidents happen during the timeline of EtN? What would have happened, and where? When?

Are Pepito and Colin related in any way? (Someone please debunk or confirm this crack theory.)

From an in-universe perspective, why is it JOEY that is targeted?

What role has Daniel played in this series of unfortunate events, in-universe?

If so many creatures - from Vampires and Werewolves and Fairies, to Catholic Demons, Literature characters and Deities from various pantheons - coexist, how many walk among us? How many people do we know are actually one of these? Will they hurt us? How many are even affiliated with Evil?

Additional Notes

Joey, if you are reading this, please take notes and find some way to explain these phenomena. This series really, from a realistic perspective, needs to stop being such a mindf**k session. @joeygraceffa

TLDR version: I have a lot of questions, mainly concerning history and geography. And a couple of theories.

#escape the night#escape the night with joey graceffa#etn#escape the night theories#etn theories#me being weird#me being petty#me being salty#escape the night analysis#analysis#etn fandom#escape the night spoilers#i tried#i'm done#im crazy#i'm crazy#i'm confused#i'm curious#ao3#my ao3#shameless self promotion#my post

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Teaching: Understanding the Spiritual Place of English

What is the Place of English?

English, as a curriculum subject, has proven itself to be the most mutable of them all. Scholars and researchers have long endeavoured to define the essence of what is taught in English: to sequester its core ethos and manifest a policy that can regulate its delivery. This has landed with its back against impossibility. The subject is abstract by definition; it relies on relativity to establish its discourse. As such, trying to quantify the unquantifiable - insofar as the National Curriculum is concerned - has resulted in the slow asphyxiation of a subject which is most fruitful when left to transpire organically. This is not to say that there should be no structure to the teaching of the subject– quite the opposite. What I am suggesting here is that English must be taught in a context that values it as a spiritual activity; it must be an extension of a channel of thought that takes its roots in a humanistic view of education. When we consider Socrates’ classic view of education as ‘the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel,’ we can begin to understand English as the subject which is most closely aligned with the original purpose of education – to inspire children to grow into their own source of light that will illuminate their future path. This pursuit is - at its core - a spiritual endeavour, and the place of English must be seen as such.

Most trainees (which, it must be recognised, become teachers; trainees do not remain in some reactionary, limbo-like headspace for their entire careers, and it is not valuable to continually avow their experiences in this manner) regard The Bullock Report of 1975 as a viable starting point for the debate of the position of English, but the constellations of thought surrounding this were being brought into alignment decades before. The 1920s – often referred to as The Gilded Age of literature – strikes me, personally, as the golden age of thought and policy in terms of orientating the subject of English. The Newbolt Report of 1921 is the first piece of research that still exists in the collective memory of academics and teachers alike for birthing a strain of thought that worked to situate education and English in the context of an individual’s internal life. The report concentrated on the moralisation of pupils, claiming that education had become “too remote from life” (Newbolt, 1921, part 3). It says of English, “It is not the storing of compartments in the mind, but the development and training of faculties already existing. It proceeds, not by the presentation of lifeless facts, but by teaching the student to follow the different lines on which life may be explored and proficiency in living may be obtained. It is, in a word, guidance in the acquiring of experience” (Ibid, part 4). In this view, English is not the simple regurgitating of ‘popular’ opinion of ‘popular’ literature; it is not the calculated analysis of the linguistic frameworks that allow us to communicate with one another, and it is not the process of teaching content to assessment. It should be a heuristic process, awakening the child to the world inside them and working to position this inner space as entirely unique; it is causing the bird to realise that its ability to fly is innate, and does not need to be taught – only practised and explored.

Dixon’s 1969 report, ‘Growth Through English,’ echoed the Newboltian sentiment of the place of English being in alignment with the fundamentally spiritual purpose of education. It also acknowledged that there can be various ‘models’ applied to teaching, which serve, in my mind, two purposes; first, to dissect the multitudinous nature of teaching in order to make it palatable for those whose spectrum of thought is narrower than the concept itself; and second, to excuse those subjects which have begun to ‘fill vessels’ rather than ‘kindle flames,’ so as to render them workable by way of compartmentalisation. Here, we witness the beginning of censorship in English. It is this very notion that has led to teachers of English carrying the largest workloads, and it is this vein of applied stigmatism that creates an ‘us’ and ‘them’ dynamic across contemporary institutions. This was expanded upon, then, by the aforementioned Bullock Report. 1988 saw the publication of the Kingman’s ‘Knowledge About Language.’ This marked a landmark moment in the history of English as a curriculum subject; his suggested progressive subversion of the ‘old’ ways of thinking about and teaching English led to censorship by way of government intervention. Here, the government effectively claimed ownership over English. Further regulatory measures ensued – The Cox Report of 1989, closely followed by The National Curriculum of 1990, placed English in an Orwellian place of censorship and instruction. The power ascribed to the teachers of the ‘80s was gone; the profession had been watermarked by the uniform brush of the law.

We, as teachers of English, need to reclaim ownership of the subject which has always spoken to us on that unquantifiable, primitive level. The place of English should be within the unique space that exists between the academic and the spiritual - evolutionary and sentient, transitory in perception, but perpetuated through honour. At its core, English is – I believe - the most noble of curriculum subjects. It ventures, unashamedly, into the ambitious territory of the expansion of human experience. It dares to progress the internal story of its pupils through the study of the consciousness of others. It is the education of the spirit.

English as a Spiritual Practice

Spirituality is a majestic and ineffable term that evades permanent definition only because of its unrivalled subjectivity. However, a definition can be approached through an acknowledgement of the factors which contribute to its process. Groen, Caholic, and Graham (Groen, Caholic, and Graham, 2012) assert that, “Spirituality includes one’s search for meaning and life purpose, connection with self, others, the universe, and a higher power that is self-defined” (ibid, p.2). In the context of this essay, it is necessary to reinforce the idea that spirituality remains entirely separated from faith. Eagleton (Eagleton, 1983) articulates how the failure of religion in Victorian Britain meant that English was able to impeach this “pacifying” space and “save our souls” (ibid, p. 20). Neither I nor Eagleton are concerned not with a religious spirituality, but with the intrinsic human spirituality that Tisdell (Tisdell, 2007) describes as simply, “one of the ways people construct knowledge and meaning. It works in consort with the affective, the rational or cognitive, and the unconscious and symbolic domains” (ibid, p.20). In this view, spirituality refers to the semiotics of the subconscious mind. In my view, it is also about transcending the self in order to exist within a constant state of mindfulness of universal context, and to understand the interconnectedness of all things. To develop spiritually is to find that metacognition and existential reflexiveness come naturally. It is the place of English to aid in the development of this process.

According to Love and Talbot (Love and Talbot, 1999), “spiritual development involves an internal process of seeking personal authenticity, genuineness, and wholeness as an aspect of identity development. It is the process of continually transcending one’s current locus of centricity” (ibid, p.365). Ultimately, spiritual development - within the context of the English classroom - is about attempting to bring the lifeworld of the learner into harmony with the internality of an abstract or literary ‘other.’ This epoch exists both in and outside of human knowing; we can access our feeling of an affinity with a higher purpose without intention, but to harness this pursuit in an actionable and pedagogical way is the role of English.

The Newbolt Report describes English as the “record and rekindling of spiritual experiences,” explaining that it “does not come to all by nature, but is a fine art, and must be taught as a fine art” (Newbolt, part 14). In this view of English as an art, the writer and teacher are placed as artists. I believe it is the job of the artist to try to perpetuate those thoughts and feelings which he/she feels will most contribute to a better world; art is evidenced creationism for the betterment of the collective human spirit. Indeed, those colleagues I have surveyed within my SE school demonstrate a frustrated liberality in attempting to express their view of the place of English, echoing the sentiment of the artist being asked to quantify the purpose of their work. This is demonstrative of the way in which the abstract qualities of English have been stigmatised. On the topic of English, The National Curriculum itself states that, “through reading in particular, pupils have a chance to develop culturally, emotionally, intellectually, socially and spiritually” (NC, 1990). The decision for spirituality to be the note that this list ends on resonates powerfully with me. When ‘spirit’ can be used synonymously with ‘soul,’ it becomes clear that through all their stifling and bastardising policy, the Conservatives know that English lessons must be respected for the work that they do for the navigation of the soul.

Pedagogy of the Second-Guessed

Too much government interference has willed a separation of the academic mind from the ubiquitous spirit. The objectification of the teacher within bourgeois educational structures seems to denigrate notions of wholeness and uphold this idea: one that promotes and supports compartmentalisation (hooks, 1994, p.5). Gove’s proposed new GCSE syllabus for English literature, with its emphasis on Britannica and marginalisation of the literature of other cultures (particularly, by omission, North America), demonstrates the further devaluing of empirical learning. It works, instead, to reinforce a nationalist ideology that will serve only to racialise the British education, and therefore disenfranchise the British schoolchild. This political approach is disturbingly far from the original purpose of education, and implicates Gove as a delusional philistine.