#the art assignment

Text

Crash Course Art History is coming April 11!

This won't be the usual chronological, Eurocentric, names-and-dates version. In this series we'll hear a more expansive tale of art history, featuring diverse ways of making and a huge range of artists from across the globe.

131 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Remember The Art Assignment? Good times.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

© Paolo Dala

Under The Wave Off Kanagawa

You’ve seen this image before. A giant wave, its distinctive curly claws arched and ready to pounce. It’s invoked when natural disaster strikes, but also when it’s time to sell beer, jeans, and sweatshirts. It inspired Claude Debussy’s orchestral work “La Mer” as well as a not-insignificant number of tattoos. It’s an omnipresent image and one used towards a variety of ends. Good grief, it’s even an emoji. What is it about this image that continues to enthrall us? Let’s better know the Great Wave.

First off, the title is not the “Great Wave”, and its subject isn’t really a wave. It’s one of a series of wood block prints called “36 Views of Mount Fuji” made by the Japanese printmaker Katsushika Hokusai, between 1830 and 1833. Long considered sacred by followers of Shintoism and Buddhism among others, Mt. Fuji is depicted from a variety of perspectives and the artwork in question is just one of them.

Its actual title translates to “Under the Wave off Kanagawa” because “under” is where Mt. Fuji is nestled, far in the distance. Also under the wave are fishermen, just trying to get home after delivering fish to the city of Edo, rowing for their lives to escape the wave, but the great wave, of course, dominates the composition and has become an accepted title…

In the 1830s when the Great Wave was created, Japan was largely shut off to the wider world due to the isolationist policies of the Tokugawa shogunate then in power. We can see Hokusai borrowing from Japanese artists like Ogata Korin, especially in the tentacle-like projections from his waves, but Western realism was creeping in to Japanese art nevertheless, largely due to European engravings smuggled in by Dutch traders.

The Great Wave betrays a clear Western influence. The use of linear perspective, a low horizon line, and the appearance of Prussian blue, a synthetic pigment then very new to Japan, hailing from, that’s right, Prussia. Thousands of copies of the Mt. Fuji prints were released within Japan, mostly bought as souvenir by an emerging market of domestic tourists and those making pilgrimages to the mountain, but in the 1850s after Hokusai’s death, trade began to open up and his work was shown at the 1867 International Exposition in Paris.

Japanese culture quickly became all the rage in Europe and prints were admired and collected by many, including Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, and a number of artists who were heavily influenced by their depictions of city life, vivid colors, and what for them was a flattening of space.

In 1896, a tsunami hit Northern Japan and news of its destruction spread worldwide. It’s been hypothesized that this event, coupled with the craze helped propel the Great Wave to international renown, although the print does not depict a tsunami. In 2009, researchers identified it as a 32 to 39 foot tall rogue wave, or what they call plunging breaker. It would certainly still be deadly, however, and that’s where we get to the real and obvious drama of the picture. Nature is large and we are small.

This juxtaposition can be seen in the art of many cultures at many different times, but we have perhaps never seen it played out more clearly and more distinctly than here.

Traditional Japanese landscapes of the time put the viewer at a remove from the action, but here we are right up against this pending disaster. Hokusai’s contrast of near and far, and manmade and natural, heighten the tension and place us inside the narrative. When Debussy composed La Mer in 1903, he drew on his own childhood experience of surviving a terrifying storm on a fishing boat, as well as paintings by JMW Turner and Hokusai’s print, which he selected for the score’s cover.

The image later illustrated a 1948 Pearl Buck novel that tells the story of a young boy from a Japanese fishing village who loses his family to a tidal wave, a post World War II story of grief but also resilience.

It’s an image mobilized when disaster strikes, as it was after the devastating 2011 earthquake and tsunami off the Eastern Coast of Japan. Scientists and empirical evidence tell us that global average temperatures are rising, with extreme weather events becoming more frequent and more intense. While the sea has always been a formidable opponent for humankind and The Great Wave a useful illustration for that relationship, its relevance is likely to become even stronger, but of course the image can be interpreted in many different and less specific ways, symbolizing a great many imbalance of power.

We don’t know if our fishermen are going to make it out of there alive. It’s a cliffhanger, even if you don’t register the boats or Mt. Fuji and see the wave alone in its detached emoji state, it still holds us in and tells us quite forcefully that big things are happening, or are about to happen. Unlike the GoPro views of surfers tunneling through barrel waves, The Great Wave’s story is not one of mastery over nature. It’s notably called The Great Wave and not “The Heroic Fishermen Who Survived the Rogue Wave”.

Other artists have capitalized on the power and theatricality of waves as subject matter, but rarely in such a way that we marvel at the talents of the artist instead of the spectacular beauty of the wave itself.

What’s more, this image was meant to be reproduced, not sequestered in one museum where only a few have the privilege of witnessing it. While there are certainly numerous crimes against this image perpetrated across the internet, the crisp graphic quality of the original woodblock prints make it friendlier fodder for duplication and interpretation.

When most of us experience the ocean, this is thankfully not how we usually see it. It’s an incredibly improbable view. It’s a film still or screen capture in the most dynamic, unstable, and unpredictable of environments, but it has nevertheless become our favorite stand-in for the ocean, a way to isolate some fraction of the vastness that covers 70% of planet Earth. It’s an icon. It’s the ultimate, most wave-like of all waves, but it’s also an entire story told simply and succinctly and masterfully. Whatever your Great Wave is made of, you are undoubtedly under it and always will be, until you’re not.

Sarah Urist Green

Better Know the Great Wave

#Sarah Urist Green#Better Know the Great Wave#Katsushika Hokusai#Under the Wave off Kanagawa#Great Wave#Art#Postcard#Still Life#Architecture#Museum#Urban#City#Sumida-Hokusai Museum#Sumida#Tokyo#Japan#The Art Assignment

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"breakfast" a tma s5 animation thing

audio on:333

dawg can't even fry me an egg in this eyeconomy

[VD: A Magnus Archives animation done in orange and teal titled "Pusryčiai" (meaning: "breakfast"). Mellow music plays as Martin cracks two eggs into a frying pan. He turns away to throw the shells while the pan sizzles, and when he returns with a spatula, a "boom" sound effect plays as Martin recoils with comic disgust.

The egg yolks have been replaced by human eyeballs. Martin stares at them for a moment. He then pokes at the egg with the spatula, producing a squelching sound, and one of the eyes blinks with another gross wet sound. Martin goes from disgusted to comically sad and disappointed, and he fades away before the setting does. The video ends on the words "darė Skaistė" (meaning: made by Skaistė) and a quick shot of an eyeball. End VD]

ty @princess-of-purple-prose for the description, i edited it a bit too.

#tma#the magnus archives#tma season 5#pusryčiai means breakfast and the words at the end just say that it's made by me#did this for a video class assignment last minute#video class my ass we talk on zoom and do everything on our own#anyway figured i wasnt gonna do anything if i didnt somehow put tma in it#martin blackwood#tma fanart#animation#animatic#sketch#my posts#art#digital art#tma spoilers

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

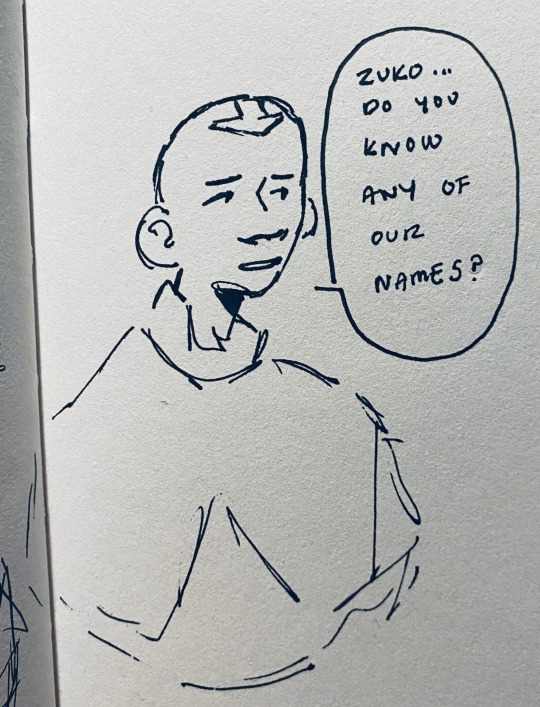

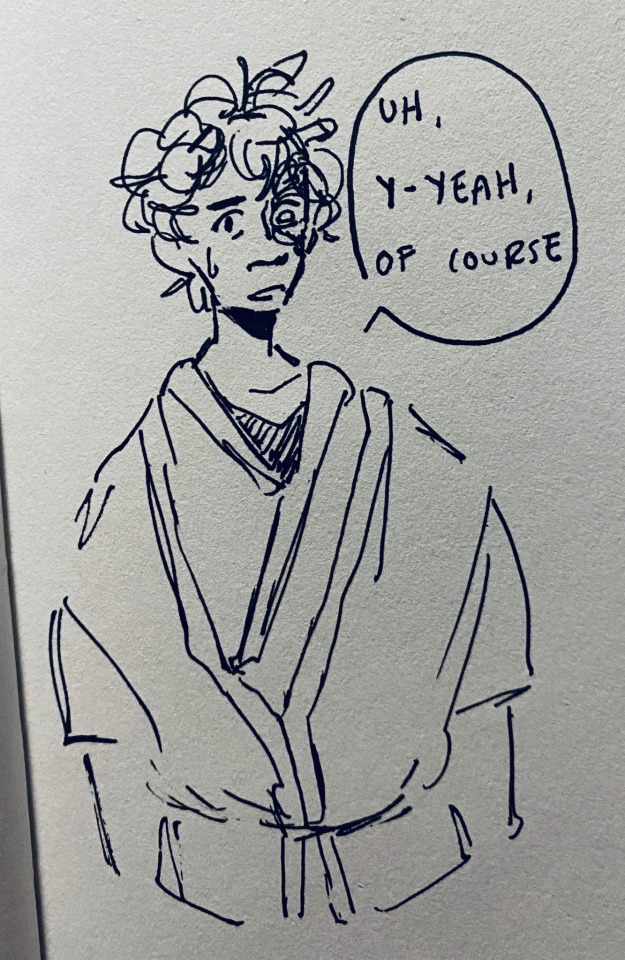

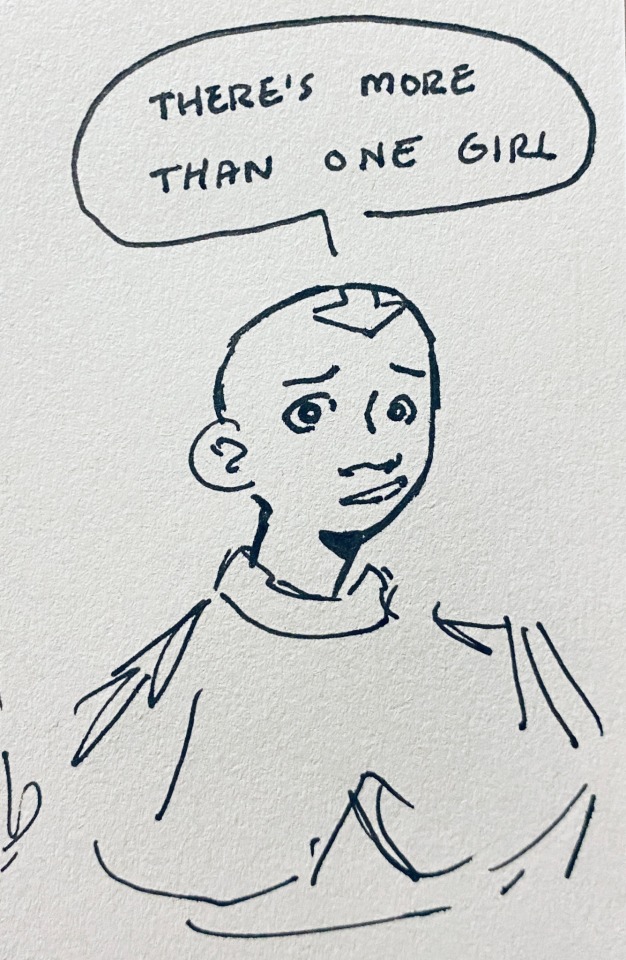

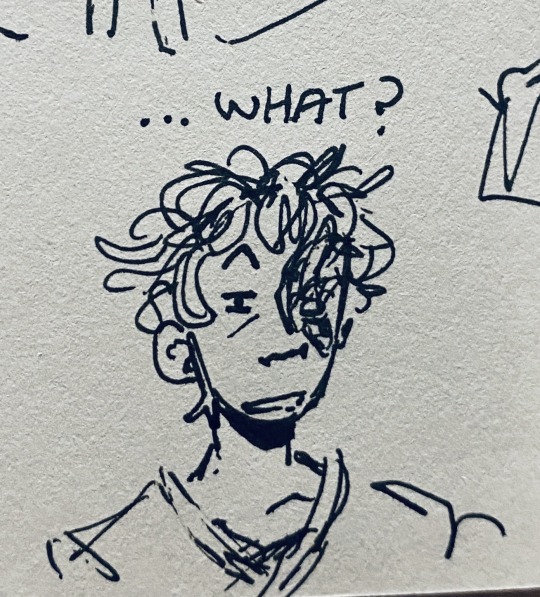

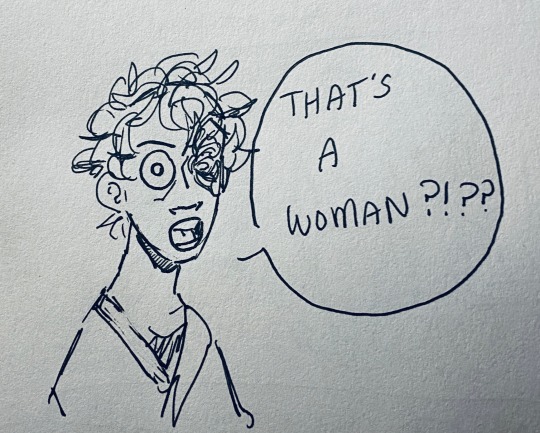

His ass does not pay attention enough to know all of their genders. Toph wears baggy clothes, he squinted at her and went “yeah that’s a boy. Or boy adjacent. Probably.” and moved on. Ally???

#memes#my crappy art#art#fyp#kay draws#atla art#atla fanart#atla#avatar#avatar the last airbender#sokka#aang#avatar aang#zuko#flameo hotman#fire lord zuko#katara#toph#toph beifong#ally????#assigned trans masc at zuko

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Creativity is Overrated by The Art Assignment

#creative motivation#art#artist problems#art block#encouragement#tips advice suggestions#The Art Assignment#video essaya#Youtube#corona2020on

1 note

·

View note

Text

hmmmm

#animation class assignment was to make examples of anticipation with 3 characters#grabbed these losers KJHSDGS#also finally an excuse to animate them!!! dies#transformers#tf#maccadam#my art#elite trine#starscream#skywarp#thundercracker#animation

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

the dunmeshi party if i were to be the lord of the dungeon.. just a glimpse into my dark reality..

#gonna try to draw izutsumi farlyn kabru and mithrun before my classes give me big assignments again 😭#sorry i havent been posting for a while :')#would also LOVE to draw the winged lion as a calico critter too if i get the chance cuz i think he'd look ridiculous lol#dungeon meshi#delicious in dungeon#dunmeshi#dungeon meshi fanart#my art#personal#digital art#fanart#manga#calico critters#sylvanian families#laios thorden#marcille donato#chilchuck tims#senshi#senshi of izganda

14K notes

·

View notes

Text

Disco wall

#for a class assignment where we had to make a few posters#of whatever we wanted#disco elysium#harrier du bois#harry du bois#raphaël ambrosius costeau#kim kitsuragi#disco elysium fanart#disco elysium art#fanart#digital art#art#my art#featured

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

imagine if Cal and Kanan met after the Purge

i like the headcanon that they were bros back in padawan days, messing around and giving a headache to everyone in the temple c::

#honestly the only one Cal could’ve given a headache to is himself#with his psychometry talents#star wars#star wars fanart#cal kestis#kanan jarrus#caleb dume#bd 1#jedi survivor#jedi fallen order#star wars rebels#jedi order#jfo#sw rebels#rebels fanart#rebels au#my art#was in a sketching doodling mood suddenly#ah yes urgent assignments that you don't really want to do can do that to you#artists on tumblr

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

ougghhh ive been doodling so many lawyers lately. they are in love your honor

#narumistu#wrightworth#miles edgeworth#phoenix wright#ace attorney#fanart#art#if youre curious the graduation season is hell#still trying to finish up my long term assignments before exams start in 2 weeks lmaooo#barely managing it tbh but whatever#drawing some lawyers is all that keeps me going atm

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

You might think that art history is a stuffy subject that's mostly about old white dudes. But with Crash Course Art History, we're thinking critically about different objects and images to understand the people, places and time periods they come from. The first episode is now available on YouTube!

By the end of this series, you'll know how to use your own canon cannon to launch artists into your own personal canon of beloved artists!

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

warrior

#ruby rose#rwby#my art#for one of my assignments where we could chose any fictional character of our liking to render#wanted to go for weiss but#sweet baby bastard is so bloody white. i am not rendering all that white. naw#might draw her on my own time lol#ruby's v7 hair still greatly confuses me lmao#the ear is so fucked up hghhhh#this could've been better but im too tired to give any more fucks hjhhhhjh#one more week sth until sem break again!!! १(>益<१)#gonna go barf out the remaining work i gotta do byee

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

© Paolo Dala

Klee, the Music Painter

Paul Klee and Cutback Studio (2022)

Infinity des Lumières (Dubai, United Arab Emirates)

Instagram And Art

Instagram has more than 500 million daily users, and its focus on images has made it especially popular among those who make and appreciate art. We are all just singular humans rooted in space and time, but Instagram gives us access to creative production all around the world, whenever we want it. Hooray! But what is it doing to us? Is it changing the way we interact with and experience art?

The benefits of using Instagram became clear pretty soon after it launched in 2010, for institutions and individuals alike. For photographers and designers and artists of all kinds, Instagram is your own free gallery. Well, if you don't count the cost of giving away your data and attention to advertisements, but it does give power to artists who represent themselves outside of traditional systems. You don't have to wait to be taken on by a gallery or make the kind of work a gallery thinks they can sell. You hold the reigns and can show your art how you'd like it to be seen. You can share aspects of your process and demonstrate that you are a person outside of your work...

Art history has tended to provide us only a handful of iconic images of artists seriously engaged in their work or posed with a painting conveniently in the background, but Instagram gives us views into the daily lives of a multitude of artists, making visible the diversity of the individuals producing art today and allowing each the ability to represent themselves, and Instagram is an outstanding networking tool, allowing you to not only build and cultivate community among other artists, but also speak directly to followers, fans, and potential collectors.

When most commercial galleries take 50% of a sale, the ability to connect to potential buyers without a middle person can be a real boon. As galleries are painfully aware, rent is high and employing people is expensive. While showing your work in person may be the ideal scenario, it's not always feasible, especially if you live in a place that isn't a cultural mecca, which is most places.

Does Instagram favor particular kinds of work? Heck yes. Square! Bright! Easily legible! Immersive! Some artworks come across better in photos than others, but most can figure out a way around these problems if they want to, and plenty of artists have used the platform as a strategic aspect of their work, recruiting participants and fundraising for performances and events, and sharing documentation with those who can't be there in person.

Some have used the images they find on Instagram to make actual works in real life. Ai Wei Wei has consistently shown us the power of social media to bear witness to his own experience of censorship and to injustice and suffering around the world, all of which are integral to the work he presents in museums and galleries, but Instagram can be a limiting influence for artists just as it's an empowering one. Like the rest of us, artists are susceptible to the dopamine rush that comes from likes and instant feedback. Artist Andrea Crespo admitted in a 2018 Vulture article, "Reward systems in social media were influencing my decisions while art making. I would think about what people would think based off of likes and comments."

Artists have long sat out insight and criticism from friends and colleagues, but more often than not, the feedback offered on Instagram is superficial or purely congratulatory or when offered by anonymous strangers, unconstructively cruel. Exposing your work on Instagram can also make it vulnerable to copycats, other artists as well as companies just trying to decorate their stores. An artist doesn't have to have their own account for this to happen either. Anyone can snap a pic of your work and post it with your name associated, making you present on Instagram even if you don't want to be, and what about Instagram's effects on museums and galleries?

Most not-for-profit institutions have missions that involve sharing their collections with the public, and their publics used to have pretty finite geographical boundaries...

Today, their conception of public can be much more expansive and inclusive. They can now try to create meaningful experiences with art for anyone with an internet connection and Instagram plays a big role in these efforts.

Museums have the problem of only being in one place. You've got to take the bus or drive and pay for parking and do all the walking. Social media platforms give museums a way of reaching people where they are, sharing works from their collection, promoting special exhibitions, and luring people out of their hidey holes with glimpses of the cool things they can be doing out in the world, and the magical part is that it doesn't have to be one way communication anymore. For so long, museums were the authority, imparting knowledge upon the huddled masses, but with social media, the huddled masses can easily impart their knowledge on the authority, explaining what they value about their experiences and what they don't.

If art museums are trying to show us the best of what's around, the peak moments in human creativity, do we want them heavily weighing Instagrammability when deciding what shows to devote money and scholarship to?

The answer doesn't have to be yes or no, and museums often navigate this by creating Insta-worthy moments within exhibitions, even if the art itself isn't so Insta-friendly...

For some, it might just be, art is cool. Me is cool, too, but I think there is more to it, or at least there can be. The research on this is just beginning, but a study of one exhibition in 2014 suggested that visitors use Instagram in meaningful ways to promote the exhibition, not replacing the in-person experience, but encouraging others to see it for themselves. The study found that visitors' use of Instagram was actually connected to their aesthetic experience. They captured mostly close-up images of the objects in the show and focused on their details. Only 9% of the images in the dataset included people.

Now, this was just one single exhibition in Sydney, Australia about the history of shoe design from the 1500s to the present. It was not a Kusama infinity room, where almost any photo is a selfie, but it's still showing, at least in one case, what I'd call real engagement with the objects. What we're really getting to here is how we construct meaning around art, right? Like, the old way was to just look at the thing, walk around it, observe it, and maybe read about it and talk about it with others.

Perhaps the camera and Instagram are tools we now use in this construction of meaning, revealing details we might not have noticed through our eyes alone, selecting and framing alternative views of the art. Does this add to the way we understand art or does it replace the traditional methods of direct observation and reflection? If, on average, we only look at a work of art for seven seconds, does our photographing it extend our engagement or does it take the place of what might have been a more fulfilling experience? Is one way better than the other or in the wise words of the internet's favorite young lass, "Why don't we have both?"

...One study published in 2017 found that taking photos with the intention to share them on social media actually undermines your enjoyment of the thing you're experiencing, increasing your feelings of anxiety. By worrying about presenting yourself in a positive light, you've lessened your engagement with the experience.

One of the co-authors of the study Alixandra Barasch, suggests you might take the pictures but wait until after the experience to share them, or you might even just take pictures for your own memories, which I think we can all agree is weird. I mean, who does that? But it's complicated. I really enjoy virtually visiting artworks and shows I can't get to by following artists and museums and galleries and curators on Instagram, and by exploring hashtags and geotags, I can find out about the ways other people experience the art I can get to. Like when I visited Prada Marfa in the middle of nowhere, Texas, I spent mediated as well as unmediated time at the site, but later, I found it really enriching to discover who else had been there, famous and not famous, years ago or just an hour before or after I did. This expanded my experience of it, extending the work beyond just an interaction between me and the art.

...Now, of course seeing an image of an artwork on a phone is not as good as being there, but social media gives us access to art and ideas that were previously off-limits for many of us due to geography or privilege and sharing art on Instagram is clearly something people want to be doing, at least right now. Museums would be foolish to ignore or resist our strong impulse to capture and share our experiences, but hopefully, we'll all evolve better, healthier ways of doing so, ways that deepen our engagement instead of making it more superficial.

Instagram can't last forever. No platform does. Maybe one day, we'll just get tired of filtering our lives through screens and museums will still be there for us. Not as stage sets for our individual dramas, but as destinations in themselves, whole places filled with voices and visions, past and present, where we can come together and interact in real time and real space, or maybe we'll come to some sort of equilibrium between those poles. Until then, I'll see you on Instagram.

Sarah Urist Green

Is Instagram Changing Art?

#Sarah Urist Green#Is Instagram Changing Art?#Art#The Art Assignment#Klee#the Music Painter#Paul Klee#Cutback Studio#Infinity des Lumières#Immersive Art#Dubai Mall#Dubai#United Arab Emirates

1 note

·

View note

Text

cod boy and salmon girl do some fishing

#do you know like- those photos of men posing with the fish they just caught? this is the same thing except its the fandom assigned sister#avian/canary jimmy became popular so they had to steal the seablings aesthetic adskjdakds#grian mc#grian mc fanart#pearlescentmoon#pearlescentmoon fanart#hermitcraft#man i love season 10#so much fishing#mcyt#artist on tumblr#digital art#fanart#sol art#skyblings#grian#grian fanart

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

little doodle of the boys :’))

#manga spoilers#bnha spoilers#mha spoilers#bnha#mha#my hero academia#midoriya izuku#bakugou katsuki#deku#kacchan#bkdk#dkbk#bakudeku#habs art#doodles#mha 403#I’ve got something else cooking too but it needs to simmer longer#(ie I have like ten assignments due next week and need a miracle to get everything done)

7K notes

·

View notes