Text

Isn’t Everything Autobiographical?: Ethan Hawke In Nine Films And A Novel by Marya Gates

When asked during his first ever on-camera interview if he’d like to continue acting, a young Ethan Hawke replied, “I don’t know if it’s going to be there, but I’d like to do it.” He then gives a guileless shrug of relief as the interview ends, wiping imaginary sweat off his brow. The simultaneous fusion of his nervous energy and poised body language will be familiar to those who’ve seen later interviews with the actor. The practicality and wisdom he exudes at such a young age would prove to be a through-line of his nearly 40-year career. In an interview many decades later, he told Ideas Tap that many children get into acting because they’re seeking attention, but those who find their calling in the craft discover that a “desire to communicate and to share and to be a part of something bigger than yourself takes over, a certain craftsmanship—and that will bring you a lot of pleasure.”

Through Hawke’s dedication to his craft, we’ve also seen his maturation as a person unfold on screen. Though none of his roles are traditionally what we think of when we think of autobiography, many of Hawke’s roles, as well as his work as a writer, suggest a sort of fictional autobiographical lineage. While these highlights in his career are not strictly autofiction, one can trace Hawke’s Künstlerromanesque trajectory from his childhood ambitions to his life now as a man dedicated to art, not greatness.

Hawke’s first two films, Joe Dante’s sci-fi fantasy Explorers with River Phoenix and Peter Weir’s Dead Poets Society with Robin Williams, set the tone for a diverse filmography filled with popcorn fare and indie cinema in equal measure, but they also served as touchstones in his development as person drawn to self-expression through art. In an interview with Rolling Stone’s David Fear, Hawke spoke about the impact of these two films on him as an actor. When River Phoenix, his friend and co-star in Explorers, had his life cut short by a drug overdose, it hit Hawke personally. He saw from the inside what Hollywood was capable of doing to young people with talent. Hawke never attempted to break out, to become a star. He did the work he loved and kept the wild Hollywood lifestyle mostly at arm’s length.

Like any good film of this genre, Dead Poets Society is not just a film about characters coming of age, but a film that guides the viewer as well, if they are open to its message. Hawke’s performance as repressed schoolboy Todd in the film is mostly internal, all reactions and penetrating glances, rather than grandiose movements or speeches. Through his nervy body language and searching gaze, you can feel both how closed off to the world Todd is, and yet how willing he is to let change in. Hawke has said working on this film taught him that art has a real power, that it can affect people deeply. This ethos permeates many of the characters Hawke has inhabited in his career.

In Dead Poets Society, Mr. Keating (Robin Williams) tells the boys that we read and write poetry because the human race is full of passion. He insists, “poetry, beauty, romance, love—these are what we stay alive for.” Hawke gave a 2020 TEDTalk entitled Give Yourself Permission To Be Creative, in which he explored what it means to be creative, pushing viewers to ask themselves if they think human creativity matters. In response to his own question, he said “Most people don’t spend a lot of time thinking about poetry, right? They have a life to live and they’re not really that concerned with Allen Ginsberg’s poems, or anybody’s poems, until their father dies, they go to a funeral, you lose a child, somebody breaks your heart, they don’t love you anymore, and all of the sudden you’re desperate for making sense out of this life and ‘has anyone ever felt this bad before? How did they come out of this cloud?’ Or the inverse, something great. You meet somebody and your heart explodes. You love them so much, you can’t even see straight, you know, you’re dizzy. ‘Did anybody feel like this before? What is happening to me?’ And that’s when art is not a luxury. It’s actually sustenance. We need it.”

Throughout many of his roles post-Dead Poets Society, Hawke explores the nature of creativity through his embodiment of writers and musicians. Often these characters are searching for a greater purpose through art, while ultimately finding that human connection is the key. Without that human connection, their art is nothing.

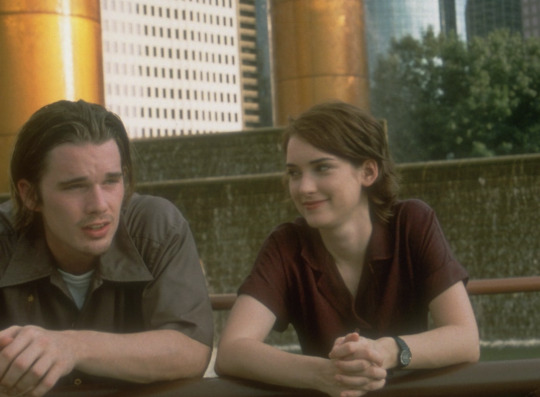

We see the first germ of this attraction to portray creative people on screen with his performance as Troy Dyer in Reality Bites. As Troy Dyer, a philosophy-spouting college dropout turned grunge-band frontman in Reality Bites, Hawke was posited as a Gen-X hero. His inability to keep a job and his musician lifestyle were held in stark contrast to Ben Stiller’s yuppie TV exec Michael Grates. However in true slacker spirit, he isn’t actually committed to the art of music, often missing rehearsals, as Lelaina points out. Troy even uses his music at one point to humiliate Lelaina, dedicating a rendition of “Add It Up” by Violent Femmes to her. The lyrics add insult to injury as earlier that day he snuck out of her room after the two had sex for the first time. Troy’s lack of commitment to his music matches his inability to commit to those relationships in his life that mean the most to him.

Reality Bites is also where he first positioned himself as one of the great orators of modern cinema.” Take this early monologue, in which he outlines his beliefs to Winona Ryder’s would-be documentarian Lelaina Pierce: “There’s no point to any of this. It’s all just a random lottery of meaningless tragedy and a series of near escapes. So I take pleasure in the details. You know, a quarter-pounder with cheese, those are good, the sky about ten minutes before it starts to rain, the moment where your laughter become a cackle, and I, I sit back and I smoke my Camel Straights and I ride my own melt.”

Hawke brings the same intense gaze to this performance as he did to Dead Poets Society, as if his eyes could swallow the world whole. But where Todd’s body language was walled-off, Troy’s is loud and boisterous. He’s quick to see the faults of those around him, but also the good things the world has to offer. It’s a pretty honest depiction of how self-centered your early-20s tend to be, where riding your own melt seems like the best option. As the film progresses, Troy lets others in, saying to Lelaina, “This is all we need. A couple of smokes, a cup of coffee, and a little bit of conversation. You, me and five bucks.”

Like the character, Hawke was in his early twenties and as he would continue to philosophize through other characters, they would age along with him and so would their takes on the world. If you only engage with anyone at one phase in their life, you do a disservice to the arc of human existence. We have the ability to grow and change as we learn who we are and become less self-centered. In Hawke’s career, there’s no better example of this than his multi-film turn as Jesse in the Before Trilogy. While the creation of Jesse and Celine are credited to writer-director Richard Linklater and his writing partner Kim Krizan, much of what made it to the screen even as early as the first film were filtered through the life experiences of Hawke and his co-star Julie Delpy.

In a Q&A with Jess Walter promoting his most recent novel A Bright Ray of Darkness, Hawke said that Jesse from the Before Trilogy is like an alt-universe version of himself, and through them we can see the self-awareness and curiosity present in the early ET interview grow into the the kind of man Keating from Dead Poets Society urged his students to become.

In Before Sunrise, Hawke’s Jesse is roughly the same age as Troy in Reality Bites, and as such is still in a narcissistic phase of his life. After spending several romantic hours with Celine in Vienna, the two share their thoughts about relationships. Celine says she wants to be her own person, but that she also desperately wants to love and be loved. Jesse shares this monologue, “Sometimes I dream about being a good father and a good husband. And sometimes it feels really close. But then other times it seems silly, like it would ruin my whole life. And it’s not just a fear of commitment or that I’m incapable of caring or loving because. . . I can. It’s just that, if I’m totally honest with myself, I think I’d rather die knowing that I was really good at something. That I had excelled in some way than that I’d just been in a nice, caring relationship.”

The film ends without the audience knowing if Jesse and Celine ever see each other again. That initial shock is unfortunately now not quite as impactful if you are aware of the sequels. But I think it is an astute look at two people who meet when they are still discovering who they are. Still growing. Jesse, at least, is definitely not ready for any kind of commitment. Then of course, we find out in Before Sunset that he’s fumbled his way into marriage and fatherhood, and while he’s excelling at the latter, he’s failing at the former.

As in Reality Bites, Hawke explores the dynamics of band life again in Before Sunset, when Jesse recalls to Celine how he was in a band, but they were too obsessed with getting a deal to truly enjoy the process of making music. He says to her, “You know, it's all we talked about, it was all we thought about, getting bigger shows, and everything was just...focused on the future, all the time. And now, the band doesn't even exist anymore, right? And looking back at the... at the shows we did play, even rehearsing... You know, it was just so much fun! Now I'd be able to enjoy every minute of it.”

The filming of Before Sunset happened to coincide with the dissolution of Hawke’s first marriage. And while these films are not autobiographical, everyone involved have stated that they’ve added personal elements to their characters. They even poke fun at it in the opening scene when a journalist asks how autobiographical Jesse’s novel is. True to form, he responds with a monologue, “Well, I mean, isn’t everything autobiographical? I mean, we all see the world through our own tiny keyhole, right? I mean, I always think of Thomas Wolfe, you know. Have you ever seen that little one page note to reader in the front of Look Homeward, Angel, right? You know what I'm talking about? Anyway, he says that we are the sum of all the moments of our lives, and that, anybody who sits down to write is gonna use the clay of their own life, that you can’t avoid that.”

While Before Sunset was shot in 2003, released in 2004 and this monologue refers to the fictional book within the trilogy entitled This Time, Hawke would take this same approach more than a decade later with his novel A Bright Ray of Darkness.

In the novel, Hawke crafts a quasi-autobiographical story, using his experience in theater to work through the perspective he now has on his failed marriage to Uma Thurman. Much like Jesse in Before Sunset, Hawke is reluctant to call the book autobiographical, but the parallels to his own divorce are evident. And as Jesse paraphrased Wolfe, isn’t everything we do autobiographical? In the book, movie star William Harding has blown up his seemingly picture-perfect marriage with a pop star by having an affair while filming on location in South Africa. The book, structured in scenes and acts like a play, follows the aftermath as he navigates his impending divorce, his relationship with his small children, and his performance as Hotspur in a production of Henry IV on Broadway.

Throughout much of the novel, William looks back at the mistakes he made that led to the breakup of his marriage. He’s now in his 30s and has the clarity to see how selfish he was in his 20s. Hawke, however, was in his forties while writing the book. Through the layers of hindsight, you can feel how Hawke has processed not just the painful emotional growth spurt of his 20s, but also the way he can now mine the wisdom that comes from true reflection. Still, as steeped as the novel is in self-reflection, it does not claim to have all the answers. In fact, it offers William, as well as the readers, more questions to contemplate than it does answers.

The wisdom to know that you will never quite understand everything is broached by Hawke early in the third film in the Before Trilogy, 2013’s Before Midnight. At this point in their love story, Jesse’s marriage has ended and he and Celine are parents to twin girls. Jesse has released two more books: That Time, which recounts the events of the previous film, and Temporary Cast Members of a Long-Running But Little Seen Production of a Play Called Fleeting. Before Midnight breaks the bewitching spell of the first two films by adding more cast members and showing the friction that comes with an attempt to grow old with someone. When discussing his three books, a young man says the title of his third is too long, Jesse says it wasn’t as well loved, and an older professor friend says it’s his best book because it’s more ambitious. It seems Linklater and company already knew how the departure of this third film might be regarded by fans. But it is this very departure that shows their commitment to honestly showing the passage of time and our relationship to it.

About halfway through the film Jesse and Celine depart the Greek villa where they have been spending the summer, and we finally get a one-on-one conversation like we’re used to with these films. In one exchange, I feel they summarize the point of the entire trilogy, and possibly Hawke’s entire ethos:

Jesse: Every year, I just seem to get a little bit more humbled and more overwhelmed about all the things I’m never going to know or understand.

Celine: That’s what I keep telling you. You know nothing!

Jesse: I know, I know! I'm coming around!

[Celine and Jesse laugh.]

Celine: But not knowing is not so bad. I mean, the point is to be looking, searching. To stay hungry, right?

Throughout the series, Linklater, Delpy, and Hawke explore what they call the “transient nature of everything.” Jesse says his books are less about time and more about perception. It’s the rare person who can assess themselves or the world around them acutely in the present. For most of us, it takes time and self-reflection to come to any sort of understanding about our own nature. Before Midnight asks us to look back at the first two films with honesty, to remove the romantic lens with which they first appeared to us. It asks us to reevaluate what romance even truly is.

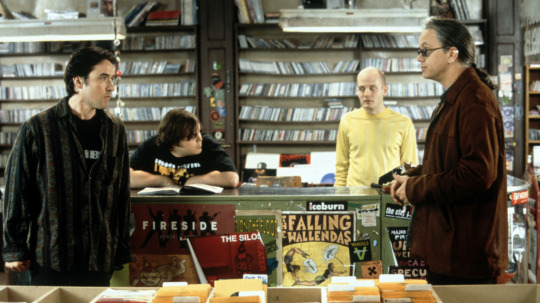

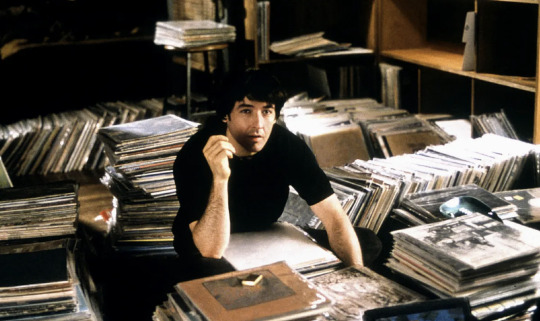

Hawke explores this same concept again in the 2018 romantic comedy Juliet, Naked. In this adaptation of the 2009 Nick Hornby novel, Hawke plays a washed-up singer-songwriter named Tucker Crowe. He had a big hit album, Juliet, in the early ‘90s and then disappeared into obscurity. Rose Bryne plays a woman named Annie whose longtime boyfriend Duncan is obsessed with the singer and the album, stuck on the way the bummer songs about a bad breakup make him feel. As the film begins, Annie reveals that she thinks she’s wasted 15 years of her life with this schmuck. This being a rom-com, we know that Hawke and Byrne’s characters will eventually meet-cute. What’s so revelatory about the film is its raw depiction of how hard it is for many to reassess who they really are later in life.

Duncan is stuck as the self-obsessed, self-pitying person he likely was when Annie first met him, but she reveals he was so unlike anyone else in her remote town that she looked the other way for far too long. Now it’s almost too late. By chance, she connects with Crowe and finds a different kind of man.

See, when Crowe wrote Juliet, he also was a navel-gazing twentysomething whose emotional development had not yet reached the point of being able to see both sides in a romantic entanglement. He worked through his heartbreak through art, and though it spoke to other people, he didn’t think about the woman or her feelings on the subject. In a way, Crowe’s music sounds a bit like what Reality Bites’s Troy Dyer may have written, if he ever had the drive to actually work at his music. Eventually, it’s revealed that Crowe walked away from it all when Julie, the woman who broke his heart, confronted him with their child—something he was well aware of, but from which he had been running away. Faced with the harsh reality of his actions and the ramifications they had on the world beyond his own feelings, he ran even farther away from responsibility. In telling the story to Annie, he says, “I couldn’t play any of those songs anymore, you know? After that, I just... I couldn’t play these insipid, self-pitying songs about Julie breaking my heart. You know, they were a joke. And before I know it, a couple of decades have gone by and some doctor hands me... hands me Jackson. I hold him, you know, and I look at him. And I know that this boy. . . is my last chance.”

When we first meet Crowe, he’s now dedicated his life to raising his youngest son, having at this point messed up with four previous children. The many facets of parenthood is something that shows up in Hawke’s later body of work many times, in projects as wholly different as Brooklyn’s Finest, Before Midnight, Boyhood, Maggie’s Plan, First Reformed, and even his novel A Bright Ray of Darkness. In each of these projects, decisions made by Hawke’s characters have a big impact on their children’s lives. These films explore the financial pressures of parenthood, the quirks of blended families, the impact of absent fathers, and even the tragedy of a father’s wishes acquiesced without question. Hawke’s take on parenthood is that of flawed men always striving to overcome the worst of themselves for the betterment of the next generation, often with mixed results.

Where Juliet, Naked showed a potential arc of redemption for a father gone astray, First Reformed paints a bleaker portrait. Hawke plays Pastor Toller, a man of the cloth struggling with his own faith who attempts to counsel an environmental activist whose impending fatherhood has driven him to suicidal despair. Toller himself is struggling under the weight of fatherhood, believing he sent his own son to die a needless death in a morally bankrupt war. Sharing the story, he says “My father taught at VMI. I encouraged my son to enlist. It was the family tradition. Like his father, his grandfather. Patriotic tradition. My wife was very opposed. But he enlisted against her wishes. . . . Six months later he was killed in Iraq. There was no moral justification for this conflict. My wife could not live with me after that. Who could blame her? I left the military. Reverend Jeffers at Abundant Life Church heard about my situation. They offered me a position at First Reformed. And here I am.” How do we carry the weight of actions that affect lives that are not even our own?

If Peter Weir set the father figure template in Dead Poets Society, and Paul Schrader explored the consequences of direct parental influence on their children’s lives, director Richard Linklater subverts the idea of a mentor-guide in Boyhood, showing both parents are as lost as the kid himself. When young Mason (Ellar Coltrane) asks his dad (Hawke) what’s the point of everything, his reply is “I sure as shit don’t know. Nobody does. We’re all just winging it.” As the film ends, Mason sits atop a mountain with a new friend he’s made in the dorms discussing time. She says that everyone is always talking about seize the moment—carpe diem!—but she thinks it’s the other way around. That the moments seize us. In Reality Bites, Troy gets annoyed at Lelaina’s constant need to “memorex” everything with her camcorder, yet Boyhood is a film about capturing a life over a 12-year period. The Before Trilogy checks in on Jesse and Celine every nine years. Hawke’s entire career. in fact, has captured his growth from an awkward teen to a prolific artist and devoted father, a master of his craft and philosopher at heart.

#ethan hawke#boyhood#before trilogy#before midnight#before sunset#before sunrise#reality bites#first reformed#dead poets society#a bright ray of darkness#film writing#film essay#musings#oscilloscope laboratories

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is Serious Business You're Fucking with Here: The Films of William Friedkin by Bill Ryan

The way things currently stand, it’s probably safe to say that William Friedkin has retired. Not that there isn’t still a market for his brand of hilarious, opinionated coarseness—as two recent documentaries, Francesco Zeppel’s Friedkin Uncut, and Alexandre O. Philippe’s Leap of Faith: William Friedkin on The Exorcist can attest—but as a filmmaker, as a director of movies of all kind, movies that are often idiosyncratic, sometimes nakedly commercial, not infrequently provocative, even deeply shocking, he appears to have packed it in. Friedkin is 85 now, so who can blame him, especially when you consider how much longer the gaps between his films had become? He’s made just three in the last fifteen years.

One of those, the last one, is a documentary called The Devil and Father Amorth, which purports to document the genuine exorcism of a woman actually possessed by an evil spirit. I have my doubts about this, but regardless, if that film does indeed turn out to be Friedkin’s last, there’s a neat symmetry to it, as his first picture was also a documentary. The People vs. Paul Crump was made for television, and combines noirish reenactments and interviews with the key subjects to tell the case of Paul Crump, a black man on Death Row for the murder of a security guard during an attempt to rob the payroll office of a Chicago meatpacking plant. The crime occurred in 1953, and Friedkin’s film—which in addition to suggesting Crump was innocent, also asserts that even if he’s guilty, he was rehabilitated—aired in 1962.

The People vs. Paul Crump was very successful, and allowed Friedkin to pick up more TV work until, in the late 60s, he was finally able to begin his career in features. It’s one hell of a wild career, too, one that can be divided into sections that show both the occasionally scattershot nature of his subject matter and the years when his focus on theme and his own specific style was much sharper, which I’ve done. Let’s get started:

I. Do You Recognize an External Force?

There is no better evidence that Friedkin’s life as a filmmaker has been a unique one than the fact that his first feature was Good Times, a kind of sketch comedy film starring Sonny & Cher (and quite frankly starring Sonny more than Cher) that was ultimately kind of a dry-run for their eventual TV variety shows. It co-stars, naturally enough, George Sanders as a movie executive whose pitch to Sonny about getting him and his wife into the movie business leads to a series of fantasies in which Sonny plays the bumbling hero in different genre movies— a Western, jungle adventure, and so on.

I’ll say this much for Good Times: it could be worse. It sure as hell could also be better, and in any case it’s not very distinctive as far as Friedkin’s own work on it goes. The kind of palatable, big-cartoon-flower Laugh-In-style psychedelia of the film doesn’t exactly jibe with the sensibilities and preoccupations that define most of his work. Friedkin would follow up Good Times with another comedy, The Night They Raided Minsky’s (1968), a period film about the origins of striptease. Made in collaboration with producer and co-writer (with Sidney Michaels and Arnold Schulman) Norman Lear, the film is, according to Friedkin, a complete shambles, a disaster that threatened to ruin his career before it had really begun. In his memoir The Friedkin Connection, he describes his fraught relationship with Lear, and writes: “I brought what I could to the picture, but I was the director in name only.

Unfortunately, or maybe fortunately, I was unable to watch The Night They Raided Minsky’s in time for this piece, but following a Sonny and Cher sketch film and a comedy about burlesque striptease, his next film was an adaptation of Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party. “It was the first film I really wanted to make, and felt passionate about,” he writes in his memoirs, and that hunger and inspiration is evident. The Birthday Party is, to my mind, Friedkin’s first masterpiece. Taking place almost entirely in just two rooms, the film stars Robert Shaw as Stanley, a shambolic, drunken tenant of a small boarding house run by Meg (Dandy Nichols) and her husband Petey (Moultrie Kelsall). After a long, strange, almost sinisterly flirtatious conversation between Stanley and the dowdy Meg, two new boarders arrive: McCann (Patrick Magee) and Goldberg (Sydney Tafler). These two men appear to know something about Stanley—indeed, they seem to be there, at this boardinghouse, entirely because of Stanley—and as they charm the naïve Meg into throwing a birthday party for Stanley (whether it is even really his birthday is unclear), the atmosphere of the kitchen, and of the parlor, and of the film, grows increasingly infernal.

When turning a stage play into a work of cinema, it’s a common mistake for the director to overwork the camera, and to block the scenes so that the actors never stop moving, all in a desperate attempt to save the audience from what they imagine would otherwise be immense boredom. A good example of this is Michael Corrente’s film of David Mamet’s American Buffalo, in which Dennis Franz is forever wandering around his pawn shop while he talks to Dustin Hoffman, with no clear purpose behind his movements. Friedkin, on the other hand, waits until the camera needs to do something before he does it. Early on, there’s an elegant shot during breakfast: the camera dollies in on the plate of fried bread that Meg has set on the counter for Stanley. It then moves around the counter and into the kitchen itself. This happens slowly, but is dynamic, and opens up the geography of the space. It also expresses the curious menace of the everyday, which is the psychological level from which Pinter’s play begins.

Later, as the action and dialogue during the party (and especially when the characters play Blind Man’s Bluff) becomes increasingly surreal, absurdist, and frightening—and as good as Magee, Shaw, and Nichols are, the terrifying Sydney Tafler steals the film—Friedkin’s direction becomes more chaotic, switching from color to black-and-white any time the lights are turned off, and employing stark, grainy afterimage optical effects that he would use again five years later in The Exorcist. And the overall impact of The Birthday Party is, for me, that of an unusually powerful horror film. What happens in the film, why it happens, is essentially inexplicable, but at the core is something horrible. It’s the terror of the unknown in the everyday. To me, it most closely resembles the exquisitely unnerving horror fiction of Robert Aickman, and of “Mr. Clubb and Mr. Cuff,” a novella by horror writer and Aickman acolyte Peter Straub.

By now seemingly obsessed with plays about birthday parties, Friedkin’s next film was an adaptation of Mart Crowley’s The Boys in the Band (1970). The play, and film, takes place over the course of a day and night, about a group of gay men who are gathering at Michael’s (Kenneth Nelson) to celebrate the birthday of Harold (Leonard Frey). Harold is late to his own party, and acts like a satyr, or Satan, when he does.

The Boys in the Band is a bit more conventional, as a piece of filmmaking, than The Birthday Party, but it’s a good movie, and the first example in Friedkin’s career of his willingness to either consciously buck against, or simply not think about, what, in a given era, is considered polite or tasteful, or to attempt to make mainstream that which others believe should be hidden. The Boys in the Band was, in fact, one of the first American films to focus exclusively on the lives of gay characters. Not all of the actors were gay, but many were, and the tragedy of it all is that several of them, including Nelson and Frey, would die in the ‘80s and ‘90s of AIDS-related illnesses. Another, Reuben Greene, seems to have vanished off the face of the earth.

II. I Am No One

And then suddenly, everything changed. The French Connection happened in a very ordinary way. William Friedkin met and got to know the producer Phil D’Antoni, who one day told him about a non-fiction book by Robin Moore he’d optioned, about an enormous heroin bust, so they flew to New York to meet the two cops at the center of the case. They had to shop Ernest Tidyman’s script around for a while, but that’s not unusual, either. What was unusual was that it was 1971, New Hollywood was taking over, and it was possible to make The French Connection the way Friedkin saw it, and the way it should be made. Or, the way it could be made to work, at least. Friedkin was at the time, by his own admission, an abusive, ill-tempered director. In order to get the performance out of the anxious, uncertain, surly Gene Hackman (playing the racist, ruthless and brilliant cop Popeye Doyle) that he wanted, Friedkin was intentionally tyrannical towards the actor, stoking the rage he wanted Doyle to express: “Gene had to play an angry, obsessive man, and I could provoke that anger in him and let him focus it on me,” he writes in his memoir.

I’m no director, but there are perhaps better ways of handling that. Worse still is the way he shot the famous car/subway chase. From The Friedkin Connection: “I…would not…risk the lives of others as we did, but the best moments of the chase came from this long run with three cameras; pedestrians and cars dashed out of the way, warned only by the oncoming siren.” When Friedkin appeared on Marc Maron’s “WTF” podcast, he told Maron that now he would use computer effects to shoot a scene like that. Dubious, Maron pointed out how real The French Connection was, and when reminded by Friedkin that it’s not real, it’s a movie, Maron protested “You just said people’s lives were in danger!” Friedkin gently responded “That’s not a good thing, Marc.”

But two things are unavoidable: no one died or was even hurt in that scene, and to this day that chase scene kills. It is headlong, heedless, as wild and dangerous as it looks. And Hackman’s Doyle, one senses, would just as soon run down the woman with the baby carriage if he didn’t think it would slow him down more than swerving around her at the last second. Suddenly, the world of Friedkin’s cinema was one of terrifying moral uncertainty, both in the stories they told, and in their making.

While making his next film, The Exorcist (1973), based on the best-selling novel by William Peter Blatty, who wrote the screenplay, Friedkin slapped the face of Father William O’Malley, an actual priest who was cast to play Father Dyer, so that when he yelled “Action!” a second later, O’Malley’s hands would shake the way Friedkin wanted, as Dyer gave Last Rites to his best friend, Father Damien Karras (Jason Miller). Further, in order to get the shot of Ellen Burstyn as Chris MacNeil, the harried single mother of the demonically possessed young girl Regan (Linda Blair), being thrown across the room by Regan, Friedkin put a harness on the actress, which was attached to a device that would lift her off the ground and yank her backward. This stunt, for which Burstyn was not fully prepared, badly injured her back, from which she still suffers. In the various documentaries about the making of The Exorcist in which she has appeared, Burstyn doesn’t seem to have ever forgiven him. And of course, the depraved horror imagery of the film remains repulsive. I still cannot believe that the “Let Jesus fuck you!” scene exists in a big budget studio film. It’s mind-boggling, not only that it’s there, but that it passed the MPAA with an R rating.

If any of this sounds like I disapprove of the film, think again. I think The Exorcist is Friedkin’s greatest achievement; I’m one of those boring people who considers it the best horror film ever made. The wintery cinematography casts a pall over the MacNeil home before anything has happened to Regan. Mike Oldfield’s “Tubular Bells” playing over the nuns in flowing white habits that Chris sees on the street makes them seem alien and unknowable. The secular world of post-“Is God Dead?” America as represented by Chris (more so than Regan, who probably hasn’t given the matter much thought) is about to have a lot of questions it had never asked itself before. Blatty was very much a Catholic, and Friedkin, who was born Jewish, has an approach to religious faith that is at least complex. (He’s described himself as an agnostic who believes the teachings of Jesus. He and Blatty were close up until the writer’s death in 2017.)

The energizing idea behind The Exorcist is to express both religious faith and Blatty and Friedkin’s belief in mankind’s essential decency through extreme transgression. This isn’t going to sit well with everybody, of course, but that’s finally what The Exorcist is, however many people wish to psychoanalyze Blatty and Friedkin by claiming the film is really about man’s (small “m”) fear of female puberty and sexuality. By which I don’t mean that Regan’s age and gender were chosen by throwing darts at a board, but this reading of the film seems to not only want to treat the ending as meaningless or arbitrary, but to pretend that Father Karras and Father Merrin (Max von Sydow) have no function in the story at all. The still-shocking obscenities in The Exorcist are meant to show the corruption not only of Regan's innocence, but the natural growth that her puberty is bringing forth, as well. Blatty and Friedkin don’t see her pending womanhood as terrifying—they view the unnatural exploitation of it by the demon as terrifying.

The Exorcist was a sensation. Having won the Oscars for Best Director and Best Picture for The French Connection two years earlier, Friedkin was nominated for both again in 1973. His string of failures was at an end. He seemed to be spending the ‘70s the same way Francis Ford Coppola was, with one incredible artistic and commercial achievement after another. Maybe this is where karma stepped in. If so, the form it took was that of Sorcerer (1977), one of his best films. (I’d call it his best, if not for The Exorcist.) Based on Henri-Georges Clouzot 1953 classic The Wages of Fear, Sorcerer (screenplay by Walon Green) is about a group of men—a hitman (Francisco Rabal), a terrorist (Amidou), a disgraced banker (Bruno Cremer), and a thief and getaway driver (Roy Scheider)—on the run from their various crimes and countries, who find themselves together in Porvenir, a small Latin American town. There they land work transporting crates of unstable dynamite, each stick sweating nitroglycerine, over hills and mountains, across swaying bridges and through violent storms. And so the stage is set for an unbearably tense journey, with every jolt along the way potentially setting off the dynamite and killing them all.

The actions of each of these men have brought them to a situation where every rock in the dirt road could bring instant death, a fact not lost on them. Sorcerer is a film of exhaustion—physical, mental, metaphysical, and existential. A long sequence featuring the two gigantic trucks slowly moving across a rotten, rainswept bridge, is a masterpiece of theme as plot, theme as action. In this moment for these men, inches from being blown to pieces, it seems impossible to move forward, but also impossible to go back. So they move forward. Later in the film, when Scheider is the only one left and his truck has died mere miles from his destination, Friedkin and cinematographers Joseph M. Stephens and Dick Bush film the barren landscape where the once huge, now contextually miniscule truck sits stranded as if these were images from a different planet or a dark, lifeless underworld. It is one of the purest visual depictions of despair I’ve ever seen.

In a way, Sorcerer is a combination of Friedkin’s previous two films: it has all the gritty, hard-nosed cynicism of The French Connection as well as The Exorcist's quest for something more beyond the Hell of these men’s lives, even if the quest is carried out ignorantly, the goal swept at blindly, futilely. According to Friedkin, he had no doubt it would be a hit. It was not.

III. You Want Bread, Fuck a Baker

Needing to find a way back from the wilderness of Sorcerer to the brief days of his glorious success after The French Connection and The Exorcist, Friedkin’s next film was The Brink’s Job (1978). The film, which is not at all bad, seems like a blatant plea for commercial acceptance. It’s a heist comedy, based on a true story, roughly along the lines of the wildly successful The Sting from 1973 (a film that beat out The Exorcist at that year’s Oscars). Boasting a stacked cast that includes Peter Falk, Peter Boyle, Paul Sorvino, and Warren Oates, it nevertheless more closely resembles Friedkin’s earlier job-for-hire films. It’s well-made, at times pretty funny, and contains at least one great performance, that given by Warren Oates. But it has no personality of its own, which on the one hand is strange considering how distinct Friedkin’s aesthetic had become in the first half of the ‘70s, but on the other hand, given that he is very outspokenly against the Auteur Theory, perhaps it’s not so strange after all.

At any rate, The Brink’s Job was another commercial disappointment, so Friedkin’s response to which was to say “Fine,” and then go ahead and make Cruising (1980). Perhaps the worst career decision Friedkin could have made, it’s also clearly a film that only Friedkin was ever going to make. Based in part on the only novel written by Gerald Walker, editor and journalist for The New York Times Magazine, the story of the film is a fictionalized account of a real series of murders of gay men in the late ‘70s. The killer turned out to be Paul Bateson, a former radiologist at NYU Medical Center, and who appeared briefly, as a radiologist’s assistant, in The Exorcist. However, Walker’s novel was published in 1970, before Bateson’s murders, so in crafting the screenplay (one of only a handful he’s written) Friedkin pulled material from the book, Bateson’s story, and conversations he’d had with Randy Jurgensen, a homicide detective who’d worked a case undercover in much the same way Al Pacino’s cop Steve Burns does in the film.

Set largely amidst the gay BDSM subculture in New York, Cruising is relentlessly grimy—a grime similar to but apart from that of The French Connection—and aggressive, and for this reason it was, and remains, enormously controversial. Gay activists at the time of its release, and even during filming, protested, believing that the movie would only be used to justify the prejudices of the straight world. Friedkin claims that was never his intention, and Pacino, who almost never discusses the film, said the same thing. This is at least partially borne out by Don Scardino as Ted Bailey, Steve’s neighbor after he goes undercover and rents an apartment near the Meatpacking District, where the BDSM culture is strongest. Ted’s just a normal guy who happens to be gay, and whose murder at the film’s end is the final, nasty shock of this nasty, shocking movie. But Ted’s just one character, and it’s not difficult to understand why activists were so upset about Cruising. Add to this the fact that, originally, Friedkin shot footage of explicit gay sex to include in the nightclub scenes (which, to the surprise of no one, he was forced to remove, and which subsequently, according to Friedkin, was lost) and that, later, when he went back to restore the film for a home video release, he added split-second inserts of hardcore sex during the brutal knife murders, well, perhaps you could at least surmise that Friedkin wanted controversy, and he got it.

Which of course does not mean Cruising is a bad film. The central idea—that this investigation awakens something in Steve Burns, having to do with both his own sexuality, but of a dormant violent streak, even a psychotic one—is fascinating, and played with a kind of brash subtlety so unique to the Pacino of that era that he probably could have trademarked it. And Friedkin’s use of Boccherini’s “La Musica Notturna Delle Strade di Madrid, No. 6, Op. 30” is utterly inspired— incongruous, counterintuitive, and absolutely perfect. But Cruising is a film that struggles with itself, one that at turns seems to be trying to wrench a dark, meaningful thriller from the jaws of empty provocation, and throwing up its hands and succumbing. This is also the source of its power.

This all went about as well for Friedkin as you can imagine, and so with his next film he tried again for commercial viability. The resulting film, 1983’s political comedy Deal of the Century (written by Paul Brickman of Risky Business fame) needn’t concern us for very long. It’s about illegal arms dealers, and it stars Chevy Chase, Sigourney Weaver, and Gregory Hines. They’re all pretty good here, and the way Chase, as one of those arms dealers, says, while demonstrating all the features of a newfangled machine gun to a trio of revolutionaries, “There’s a built-in wire cutter here; you got a wire you wanna cut, it’s built in here” is something I find inexplicably amusing. But that’s about it. The biggest problem in a movie that’s full of them is that, especially in the scene just referenced, Chase’s character is supposed to be a tonier version of Steven Prince’s character from Taxi Driver. And, incredibly, we’re supposed to like this guy, even before he develops a conscience. You know, like illegal arms dealers are always doing? It’s misjudged on almost every level, and, again, exhibits none of Friedkin’s most compelling gifts.

A lot of Friedkin’s post-Sorcerer work suggests a “one for me, one for nobody” philosophy was at play, but his next film, at least when looked at within the full context of its influence, is as close to a cross-over hit as he’d had since The Exorcist. Indeed, To Live and Die in L.A. (1985) is still talked about, still watched, still discovered by new audiences, and deservedly so. A crime film about the rarely explored job of the Secret Service to track down and arrest counterfeiters—and based on a novel by Gerald Petievich, a former Secret Service agent who did that same job—perhaps the most surprising thing about the film is that it basically could not have been influenced by Michael Mann. At that time, Mann had only made (outside of some TV work) Thief and The Keep, the latter of which doesn’t apply to this situation. (Miami Vice had been on for about a season). Which means that in the mid-’80s, Mann and Friedkin were roughly, and independently, on the same wavelength. Or roughly the same wavelength, because while Mann’s color schemes tend to be brazen and primary, even neon at times, in To Live and Die in L.A., Friedkin’s take on Los Angeles crime is more pastel, somehow both muted and bright.

What Friedkin does amp up are the shock and sleaze, elements that Mann uses sparingly. To Live and Die in L.A. begins with a suicide bomber exploding (as he falls off a building, no less), for example, and is rather frank in its sexuality. It also may include the only example in film history of its particular type of villain, the sadistic counterfeiter, played here by an almost boyish Willem Dafoe. This man, Eric Masters, is the foil to Secret Service agent Richard Chance, played by William Petersen, who was one year away from starring in Mann’s Manhunter, and whose scary blankness serves him well in both. Here, Petersen is basically doing his version of Hackman’s Popeye Doyle: both men are so eerily focused on catching their prey that all other considerations, including the safety of the public, or of their fellow law enforcement colleagues, fall by the wayside. Similarly, John Pankow—as John Yukovich, Chance’s partner—matches Roy Scheider’s Buddy Russo, in that both men have a perspective and conscience that their partners lack, though Yukovich is a bit quicker to panic than Russo.

To Live and Die in L.A. is perhaps best remembered for its jaw-dropping car chase—at one point Petersen drives against traffic on the freeway—a cop/action movie trope Friedkin has returned to often, finding a new twist on it each time. As with the chase in The French Connection, this one is incredibly visceral. Despite, or perhaps because, of the fact that a chase like this could not possibly last this long without ending in catastrophe, the threat of sudden death is ever-present. It hangs over the entire film, in fact, appropriately so, given where our protagonist ends up. Speaking of which, a curious motif, and always effectively and disturbingly applied, in Friedkin’s crime films is the image of someone getting shot in the face. This goes back as far as The People vs. Paul Crump, appears again in the opening minutes of The French Connection, and occurs more than once in To Live and Die in L.A. There’s no jolt of violence quite as upsetting as that millisecond flash of a human face being ruined. If he does nothing else, Friedkin will make you feel that.

IV. It’s the Devil Station

To Live and Die in L.A. was a modest success, critically and commercially, but it didn’t put Friedkin back on the A-list. His next film, Rampage, was shot in 1987 but due to producer Dino De Laurentiis’s shifty finances, it remained unreleased in the United States until 1992, when it was acquired by Miramax. It did poorly. In The Friedkin Connection, the director describes this experience as the time he “hit bottom”: “There have been successful filmmakers of my generation, before and since, who didn’t survive disasters like Rampage. They never directed another film. It was entirely possible the same fate awaited me.”

Very well, but I happen to think Rampage is one of Friedkin’s most gripping pictures. Based on a novel by former criminal prosecutor William P. Wood, which itself was based on the murders, arrest, and trial of serial killer Richard Chase (and if you don’t know anything about Chase or his crimes, I urge to continue down this path of blissful ignorance), it’s about a murderer named Charles Reece (Alex McArthur) whose vicious crimes lead the Sacramento District Attorney to insist that the prosecutor assigned to the case, Anthony Fraser (Michael Biehn), pursue the death penalty. This despite the belief that no jury would ever find someone like Reece legally sane. And what Rampage turns out to be, quite surprisingly, is a pro-death penalty film. This is a long way from the stance Friedkin took in The People vs. Paul Crump, although wherever you stand on this issue, I’d say Crump is somewhat easier to sympathize with than Richard Chase.

Anyway, on top of everything else, without being as graphic as some of Friedkin’s films before and after this, Rampage contains some of his most disturbing imagery. It begins, bizarrely, on a freeze-frame of Reece from behind, walking down the street. The frame stays like that for maybe a second before kicking into motion. Friedkin wants the audience to start off disoriented, and then proceed from there. Of the violent imagery—very few of the killings occur on-screen—most unforgettably for me is the blood-soaked measuring cup being put into an evidence bag. Rampage also recalls, in many ways, The Exorcist, with Fraser’s flashbacks to the death of his young daughter resembling Karras’s dream sequence in that earlier film. There’s also a disquieting scene that involves a desecrated church.

It really is the damnedest movie: a melodramatic (the Morricone score is relentless) pro-execution polemic/horror film with incredibly tense, absorbing, and occasionally absurd courtroom scenes. There should have been a mistrial about three different times. But it also includes some wonderful character performances—McArthur is chilling, and especially great when the cops show up at the gas station where Reece works, and they know he’s their guy, but he pretends he’s not Reece—and some genuine emotion. The late Royce D. Applegate is especially memorable as a man trying to find a way to survive after Reece murders his wife and eldest son.

Friedkin would spend the rest of the 90s not quite living up to Rampage. His next film, The Guardian (1990, filmed three years after but released two years before Rampage), is the only other horror film he’s made, outside of The Exorcist, than you couldn’t argue belonged to another genre. But while I find the movie kind of fun (there’s a bit where a bunch of young punks are killed by trees, bushes, etc., that I quite enjoyed), and, at least in the scenes that take place in the forest, it has an interesting, low-budget kind of Labyrinth thing going on visually, it’s not actually something to go out of your way to see. Along with Deal of the Century, it’s the only film he doesn’t even mention in The Friedkin Connection.

Better, though flawed, especially at the end, and anyway not especially Friedkin-esque is 1994’s Blue Chips, a sports drama starring Nick Nolte and Shaquille O’Neal(!). Nolte plays a college basketball coach, which is a role I hope we can all agree is the one Nolte was born to play, providing as it does ample opportunities for him to say things like “Jesus Christ” and “goddamnit.”

Friedkin’s most notorious film from this era is Jade (1995), one of the films that lured David Caruso away from NYPD Blue, before sending him back to CSI: Miami. This one’s not much good either, but I’d argue it’s not without interest. One of those erotic thrillers they used to make (many of which were written by Joe Eszterhas, including this one), Friedkin—who over the years has gone from being famous for his out-sized ego to being extremely self-critical—believes Jade “contains some of my best work.” I don’t know about that, but it does have another terrific car chase, mostly slow-speed this time, through a parade in Chinatown (where there is apparently always a parade), resulting in injuries, some possibly fatal, to many innocent bystanders. It would be more interesting if it wasn’t always clear who was responsible for the injuries, David Caruso’s district attorney character or whoever the hell it was he was chasing (I have forgotten), but nobody was prepared to push the protagonist that far to the dark side. It also has a quite grim ending that should have had a better movie behind it, and a shot of Linda Fiorentino, as Jade, on all fours, facing the camera, her features grossly distorted by the stocking pulled over her head, that is more jarring and, in its way, sexually blunt than anything in Eszterhas and director Paul Verhoeven’s thriller Basic Instinct.

V. Abe Says “Where Do You Want This Killin’ Done?” and God Says “Out on Highway 61”

Friedkin spent the first half of the 2000s making a pair of military thrillers. The first, Rules of Engagement (2000), has a script from decorated Vietnam vet, successful novelist, former Secretary of the Navy, and future U.S. Senator James Webb. It stars Samuel L. Jackson as Terry Childers, a Marine colonel who, during a mission to stop an attack on the U.S. Embassy in Yemen, in which members of his platoon are killed, orders his men to fire on a group of protestors. Though Childers gave the order because he believed the protestors were armed and fired on his soldiers first, for various reasons this is perceived by the National Security Advisor (Bruce Greenwood) as murder, and Childers is charged. Childers goes to his old Vietnam buddy Hays Hodges (Tommy Lee Jones), now a military lawyer, to represent him. He agrees, squaring off in court with prosecutor, Major Mark Briggs (Guy Pearce, distractingly accented).

It’s an interesting film, and largely a good one, in my view, but it’s also the sort of thing that attracted an enormous amount of controversy, as it does ultimately support the idea that such a massacre as the audience is witness to can be justified. When the Marines fired down from the roof of the embassy at the protestors, we see, quite clearly, that the crowd includes women and children; this is something from which Friedkin does not flinch, as militarily and morally justifiable. While of course it can be, in the scenario laid out in the film (one can’t expect Marines to not return fire on their attackers), if Friedkin was surprised by the reaction, you do have to kind of wonder how he could be. Then again, at least in The Friedkin Connection, the aspect of the controversy that seems to have concerned him most was those coming specifically from Yemen, and how the film, it was believed, was both racist towards Arabs and would ruin that country’s reputation. Friedkin assures his readers that he was able to smooth things over.

It’s a rather clichéd film too, though, in a lot of ways. The worst example of this is when Hodges returns from Yemen, where he was investigating the incident, and is unable at this point in the film to prove Childers’s version of the story. He goes straight to Childers’s house (drunk, of course), furious with the colonel because he’s starting to believe his friend is a war criminal. Naturally, the two men get into a fist fight, which ends in a tie, both men battered and exhausted on the floor, and then they start laughing. Which is the sort of thing that only happens in movies, and is also the sort of thing that I would have expected Friedkin, at this point in his career, to have cut.

Much better is The Hunted (2003). Written by David Griffiths, Peter Griffiths, and Art Monterastelli, and starring Benicio del Toro and, once again, Tommy Lee Jones, it’s about Sgt. Hallam (del Toro), a former special forces operative turned assassin for the U.S., who, after an especially grueling assignment in Kosovo, snaps. He retreats to the forests of Oregon, where he murders two hunters. It is determined that Hallam is behind the killings, so the FBI agent in charge (Connie Nielsen) asks Lt. Bonham (Jones), the man who trained Hallam, to help with the case. He agrees.

The Hunted is more directly critical of the U.S. military than Rules of Engagement, and what it can force its soldiers to do, and experience, and how these things can warp a person, and turn them into something they weren’t before. Although like the earlier film, its sympathies lay with the soldiers on the ground, not those behind the desk. It is also an absolutely propulsive thriller, so primal that when the action moves from the forest to “civilization,” it feels like the film is stepping out of the world in which it really belongs, into something alien, oppressive, and unfree. It climaxes with what is to me one of the great fight scenes in modern American cinema. We’re back in the wilderness, and Jones and del Toro, armed only with knives, the only two men who belong there, are finishing what was started a very long time ago.

VI. I Am the Super Mother Bug!

The Hunted did not set the world on fire. It probably should have, but it didn’t. Friedkin wouldn’t make another movie for three years, but when he returned, and setting aside The Devil and Father Amorth, he seemed to have come to the conscious decision to end his filmmaking life making two of the best movies of his career. They are also, if I may be blunt, two of the most fucked-up films he’s ever made, which you must admit is saying something; they’re even more fucked up than The Exorcist, because it might be impossible to locate the moral center in either.

Each is based on a play by Tracy Letts, and Letts also wrote both scripts. Another play of his, August: Osage County, was turned into a film by network TV director John Wells, and a third, Superior Doughnuts, was turned into a short-lived network sitcom. I guess you’d have to call that range. Anyway, Friedkin got there first, and as with The Birthday Party, Friedkin took the inherent limitations of a cinematic adaptation of a stage production into virtues and turned Bug (2006) into an expressionistic nightmare. The film is about a woman named Agnes (Ashley Judd) who works as a waitress in a lesbian bar. She is married to a violent convict named Jerry (Harry Connick, Jr.), with whom she had a son, who we discover has disappeared. One night, through a friend, she meets Peter (Michael Shannon), an odd but friendly man with whom she starts a relationship. Peter seems like a charming eccentric at first, telling Agnes that he makes people uncomfortable because he notices things they don’t, and he knows a great deal about insects. But it soon becomes clear that Peter is a genuine madman. His brain is in a constant state of short circuit, bursting with nonsensical conspiracy theories, ranging from the belief that smoke detectors cause illness, to microchips being implanted into every American born after 1982 as a means of surveillance, and even beyond that. Unfortunately, the insanity of all this is noticed by the audience, not by Agnes. She accepts it, and it doesn’t even take her that long to come around. The title Bug applies not only to literal insects, but to the synonym for “virus,” as the story being told is that of Agnes’s infection.

The film itself is also infected. As Bug proceeds towards its ultimate conflagration (check your smoke detectors, people), Agnes and Peter become more and more connected to each other, and less connected to anyone else. At a certain point, Peter rips from his mouth, with pliers, teeth that he considers compromised, and while Agnes screams at him to stop, she soon comes to understand the wisdom behind his actions. This extraction scene goes on and on, at such a high pitch of hysteria—so many teeth are pulled—that you may be forgiven for eventually laughing. Friedkin calls the film a comedy, though I must say I didn’t laugh. I don’t know what’s wrong with the rest of you.

In another scene, their paranoia reaches such an extreme that what they believe is going on outside of their motel room—a sort of attack by intimidation by bugs and the government, some kind of air assault—is shown by Friedkin DP Michael Grady, and felt by the audience: the room begins to shake, blinding lights stream through the window. In this moment, Peter and Agnes are correct in their beliefs. We’re the ones still asleep. The last scene of Bug is bathed in blue light, the motel room is wrapped in foil. All the blood that is spilled in this scene, a not insignificant amount, is black in this light. Judd as Agnes and Shannon as Peter have been completely untethered. And somehow, Judd is not crushed by the Mack truck that is Michael Shannon. Rather, she matches him minute to minute, second to second, as outlandishly magnificent as he is, right down to her final “Oh!”

Then there’s Killer Joe (2012). The only other time I can think of off the top of my head of a filmmaker in his mid-70s releasing a picture as transgressive as this, that so upset so many people, is when, on Christmas Day 2013, Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street came out. Mind you, in that case the larger issue was critics and audiences not understanding Scorsese’s intent (or maybe while they understood it, they didn’t believe you would). In the case of Killer Joe, I don’t think it can be fairly argued that an essential point was missed by those who reviled it. They simply reviled it. (One prominent critic wrote on Letterboxd that those of his colleagues that he respected who had admitted to laughing throughout the film were “making [him] sick to [his] stomach”).

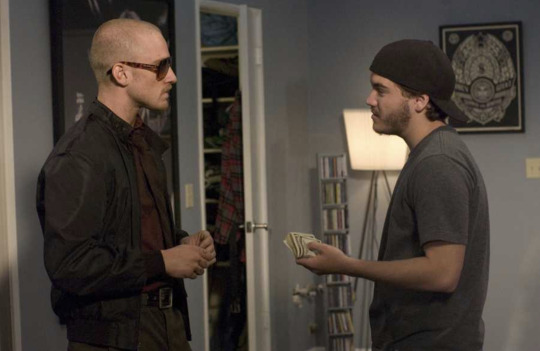

The plot is simple enough: Chris Smith (Emile Hirsch) convinces his father Ansel (Thomas Haden Church) to hire a cop and killer-for-hire named Joe Cooper (Matthew McConaughey) to murder Chris’s mother and Ansel’s ex-wife, Adele. It is Chris’s belief that Adele’s $50,000 life insurance payout will go to his sister Dottie (Juno Temple). Soon Chris, Ansel, Dottie, and Ansel’s new wife Sharla (Gina Gershon) are all in agreement to go ahead with this. The first problem they encounter is that Joe demands payment in advance, but they don’t have the money. So, in lieu of that, Chris and Ansel agree to Joe’s proposal that he be given Dottie for a night.

This is troubling enough, of course, Dottie being a good deal younger than Joe, and it’s simply an unpleasant idea anyway. But wait, it gets worse: at one point we learn that when she was a child, Adele tried to smother Dottie. Since Dottie doesn’t seem as mature as her apparent age would suggest, it’s not a leap to assume that the failed murder attempt by her own mother has resulted in Dottie suffering from some kind of developmental disability. (It is also my belief that she and Chris have, or once had, an incestuous relationship, though I don’t have a lot to hang that theory on.) This does not stop anybody. The subsequent scene between Joe and Dottie involves a bizarre, unsettling seduction, in which Joe tells her to recount to him her first experiences with love and sex. During this, talking to her as if the experience was currently happening, he asks her “How old are you now?” Dottie says “Twelve,” and in a grotesquely impassioned whisper, Joe says “So am I…” Did this make me laugh? Due to the sheer insanity of it, I admit that it did. I still think it’s funny, or “funny,” whichever.

Put simply, Killer Joe just doesn’t care. The long last scene is a small masterpiece of black comedy, discomfort, and escalating horror, ending back at the start with comedy of the darkest kind. The last image, and the cut to end credits, with the most perfect choice of end credits song I’ve seen, is the biggest laugh in a movie full of them, however little you might want to give Killer Joe what it wants from you. And if you don’t laugh, fine. The most controversial moment in the film, and the one that got it an NC-17 from the MPAA (though the uncut version is officially “unrated”), is when, in this last section, Joe, after beating Sharla because he’s learned she was double-crossing everybody, forces her to simulate fellatio on a KFC chicken drumstick, acting the whole time as though it was not a drumstick he was holding. And it’s awful, truly awful, and I don’t think it’s funny. And it goes on and on.

But I believe it’s fair to ask the question, when looked at in the context of the kind of person we understand Joe to be, why should the audience believe he would be better than that? Of course, it’s not because we believe that, it’s because we don’t want to see him do it. And we definitely don’t want to laugh at it. So don’t laugh at it, I’d argue; I certainly didn’t (though I did laugh at the moment when Ansel grabs his son around the waist to keep him from escaping from Joe’s brutal attack, crying “Get ‘im, Joe!”). But too rarely do modern films try to make the audiences squirm. They may make you upset because you disagree with their politics, but the makers of those films don’t care, or even want, you to watch them anyway. Killer Joe wants you to watch it, and wants you to react to it however you react to it. I won’t say it “challenges” the audience, because Killer Joe isn’t pushing forward any particular idea or philosophy. It’s a wild, depraved scream of amoral laughter.

And it would appear to be William Friedkin’s last feature film. When looked at in the context of his entire career, Killer Joe and Bug feel like the work of a man who has spent too much of his career not making the kinds of movies he was passionate about, that it was his natural instinct to make. Then again, the unavoidable and obvious fact of the film industry is that you have to have success, or at least some kind of positive reputation, to make anything at all. If not for his two monumental successes of the early 70s, there’s no way Friedkin would have been allowed, by anyone, to make these last two pictures. His name still meant something in 2006 and 2012, as it does now. Thank God by then he had the power of will, and the ability to put “From the Director of The Exorcist” on a poster, to go back to doing what he does best: shooting the audience in the face.

#musings#film writing#oscilloscope laboratories#william friedkin#the exorcist#the french connection#killer joe#bug film#rules of engagement#the hunted#sorcerer film#rampage#the guardian#horror film#tracy letts#the friedkin connection#cruising#cruising film#sonny and cher#beastie boys#adam yauch

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘America’s Not a Country, It’s Just a Business’: On Andrew Dominik’s ‘Killing Them Softly’ By Roxana Hadadi

“Shitsville.” That’s the name Killing Them Softly director Andrew Dominik gave to the film’s nameless town, in which low-level criminals, ambitious mid-tier gangsters, nihilistic assassins, and the mob’s professional managerial class engage in warfare of the most savage kind. Onscreen, other states are mentioned (New York, Maryland, Florida), and the film itself was filmed in post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans, though some of the characters speak with Boston accents that are pulled from the source material, George V. Higgins’s novel Cogan’s Trade. But Dominik, by shifting Higgins’s narrative 30 or so years into the future and situating it specifically during the 2008 Presidential election, refuses to limit this story to one place. His frustrations with America as an institution that works for some and not all are broad and borderless, and so Shitsville serves as a stand-in for all the places not pretty enough for gentrifying developers to turn into income-generating properties, for all the cities whose industrial booms are decades in the past, and for all the communities forgotten by the idea of progress._ Killing Them Softly_ is a movie about the American dream as an unbeatable addiction, the kind of thing that invigorates and poisons you both, and that story isn’t just about one place. That’s everywhere in America, and nearly a decade after the release of Dominik’s film, that bitter bleakness still has grim resonance.

In November 2012, though, when Killing Them Softly was originally released, Dominik’s gangster picture-cum-pointed criticism of then-President Barack Obama’s vision of an America united in the same neoliberal goals received reviews that were decidedly mixed, tipping toward negative. (Audiences, meanwhile, stayed away, with Killing Them Softly opening at No. 7 with $7 million, one of the worst box office weekends of Brad Pitt’s entire career at that time.) Obama’s first term had been won on a tide of hope, optimism, and “better angels of our nature” solidarity, and he had just defeated Mitt Romney for another four years in the White House when Killing Them Softly hit theaters on Nov. 30. Cogan’s Trade had no political components, and no connections between the thieving and killing promulgated by these criminals and the country at large. Killing Them Softly, meanwhile, took every opportunity it could to chip away at the idea that a better life awaits us all if we just buy into the idea of American exceptionalism and pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps ingenuity. A fair amount of reviews didn’t hold back their loathing toward this approach. A.O. Scott with the New York Times dismissed Dominik’s frame as “a clumsy device, a feint toward significance that nothing else in the movie earns … the movie is more concerned with conjuring an aura of meaningfulness than with actually meaning anything.” Many critics lambasted Dominik’s nihilism: For Deadspin, Will Leitch called it a “crutch, and an awfully flimsy one,” while Richard Roeper thought the film collapsed under the “crushing weight” of Dominik’s philosophy. It was the beginning of Obama’s second term, and people still thought things might get better.

But Dominik’s film—like another that came out a few years earlier, Adam McKay’s 2010 political comedy The Other Guys—has maintained a crystalline kind of ideological purity, and perhaps gained a certain prescience. Its idea that America is less a bastion of betterment than a collection of corporate interests, and the simmering anger Brad Pitt’s Jackie Cogan captures in the film’s final moments, are increasingly difficult to brush off given the past decade or so in American life. This is not to say that Obama’s second term was a failure, but that it was defined over and over again by the limitations of top-down reform. Ceaseless Republican obstruction, widespread economic instability, and unapologetic police brutality marred the encouraging tenor of Obama’s presidency. Donald Trump’s subsequent four years in office were spent stacking the federal judiciary with young, conservative judges sympathetic toward his pro-big-business, fuck-the-little-guy approach, and his primary legislative triumph was a tax bill that will steadily hurt working-class people year after year.

The election of Obama’s vice president Joe Biden, and the Democratic Party securing control of the U.S. Senate, were enough for a brief sigh of relief in November 2020. The $1.9 trillion stimulus bill passed in March 2021 does a lot of good in extending (albeit lessened) unemployment benefits, providing a child credit to qualifying families, and funneling further COVID-19 support to school districts after a year of the coronavirus pandemic. But Republicans? They all voted no to helping the Americans they represent. Stimulus checks to the middle-class voters who voted Biden into office? Decreased for some, totally cut off for others, because of Biden’s appeasement to the centrists in his party. $15 minimum wage? Struck down, by both Republicans and Democrats. In how many more ways can those politicians who are meant to serve us indicate that they have little interest in doing anything of the kind?

Modern American politics, then, can be seen as quite a performative endeavor, and an exercise in passing blame. Who caused the economic collapse of 2008? Some bad actors, who the government bailed out. Who suffered the most as a result? Everyday Americans, many of whom have never recovered. Killing Them Softly mimics this dynamic, and emphasizes the gulf between the oppressors and the oppressed. The nameless elites of the mob, sending a middle manager to oversee their dirty work. The poker-game organizer, who must be brutally punished for a mistake made years before. The felons let down by the criminal justice system, who turn again to crime for a lack of other options. The hitman who brushes off all questions of morality, and whose primary concern is getting adequately paid for his work. Money, money, money. “This country is fucked, I’m telling ya. There’s a plague coming,” Jackie Cogan says to the Driver who delivers the mob’s by-committee rulings as to who Jackie should intimidate, threaten, and kill so their coffers can start getting filled again. Perhaps the plague is already here.

“Total fucking economic collapse.”

In terms of pure gumption, you have to applaud Dominik for taking aim at some of the biggest myths America likes to tell about itself. After analyzing the dueling natures of fame and infamy through the lens of American outlaw mystique in The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Dominik thought bigger, taking on the entire American dream itself in Killing Them Softly. From the film’s very first second, Dominik doesn’t hold back, equating an easy path of forward progress with literal trash. Discordant tones and the film’s stark, white-on-black title cards interrupt Presidential hopeful Barack Obama’s speech about “the American promise,” slicing apart Obama’s words and his crowd’s responding cheers as felon Frankie (Scoot McNairy), in the all-American outfit of a denim jacket and jeans, cuts through what looks like a shut-down factory, debris and garbage blowing around him. Obama’s assurances sound very encouraging indeed: “Each of us has the freedom to make of our own lives what we will.” But when Frankie—surrounded by trash, cigarette dangling from his mouth, and eyes squinting shut against the wind—walks under dueling billboards of Obama, with the word “CHANGE” in all-caps, and Republican opponent John McCain, paired with the phrase “KEEPING AMERICA STRONG,” a better future doesn’t exactly seem possible. Frankie looks too downtrodden, too weary of all the emptiness around him, for that.

Dominik and cinematographer Greig Fraser spoke to American Cinematographer magazine in October 2012 about shooting in post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans: “We were aiming for something generic, a little town between New Orleans, Boston and D.C. that we called Shitsville. We wanted the place to look like it’s on the down-and-down, on the way out. We wanted viewers to feel just how smelly and grimy and horrible it was, but at the same time, we didn’t want to alienate them visually.” They were successful: Every location has a rundown quality, from the empty lot in which Frankie waits for friend and partner-in-crime Russell (Ben Mendelsohn)—a concrete expanse decorated with a couple of wooden chairs, as if people with nowhere else to go use this as a gathering spot—to the dingy laundromat backroom where Frankie and Russell meet with criminal mastermind Johnny “Squirrel” Amato (Vincent Curatola), who enlists them to rob a mafia game night run by Markie Trattman (Ray Liotta), to the restaurant kitchen where the game is run, all sickly fluorescent lights, cracked tile, and makeshift tables. Holding up a game like this, from which the cash left on the tables flows upward into the mob’s pockets, is dangerous indeed. But years before, Markie himself engineered a robbery of the game, and although that transgression was forgiven because of how well-liked Markie is in this institution, it would be easy to lay the blame on him again. And that’s exactly what Squirrel, Frankie, and Russell plan to do.

The “Why?” for such a risk isn’t that hard to figure out. Squirrel sees an opportunity to make off with other people’s money, he knows that any accusatory fingers will point elsewhere first, and he wants to act on it before some other aspiring baddie does. (Ahem, sound like the 2008 mortgage crisis to you?) Frankie, tired of the crappy jobs his probation officer keeps suggesting—jobs that require both long hours and a long commute, when Frankie can’t even afford a car (“Why the fuck do they think I need a job in the first place? Fucking assholes”)—is drawn in by desperation borne from a lack of options. If he doesn’t come into some kind of money soon, “I’m gonna have to go back and knock on the gate and say, ‘Let me back in, I can’t think of nothing and it’s starting to get cold,’” Frankie admits. And Australian immigrant and heroin addict Russell is nursing his own version of the American dream: He’s going to steal a bunch of purebred dogs, drive them down to Florida to sell for thousands of dollars, buy an ounce of heroin once he has $7,000 in hand, and then step on the heroin enough to become a dealer. It’s only a few moves from where he is to where he wants to be, he figures, and this card-game heist can help him get there.

In softly lit rooms, where the men in the frame are in focus and their surroundings and backgrounds are slightly blown out, slightly blurred, or slightly fuzzy (“Creaminess is something you feel you can enter into, like a bath; you want to be absorbed and encompassed by it” Fraser told American Cinematographer of his approach), garish deals are made, and then somehow pulled off with a sobering combination of ineptitude and ugliness. Russell buys yellow dishwashing gloves for himself and Frankie to wear during the holdup, and they look absurd—but the pistol-whipping Russell doles out to Markie still hurts like hell, no matter what accessories he’s wearing. Dominik gives this holdup the paranoia and claustrophobia it requires, revolving his camera around the barely-holding-it-together Frankie and cutting every so often to the enraged players, their eyes glancing up to look at Frankie’s face, their hands twitching toward their guns. But in the end, nobody moves. When Frankie and Russell add insult to injury by picking the players’ pockets (“It’s only money,” they say, as if this entire ordeal isn’t exclusively about wanting other people’s money), nobody fights back. Nobody dies. Frankie and Russell make off with thousands of dollars in two suitcases, while Markie is left bamboozled—and afraid—by what just happened. And the players? They’ll get their revenge eventually. You can count on that.

So it goes that Dominik smash cuts us from the elated and triumphant Russell and Frankie driving away from the heist in their stolen 1971 Buick Riviera, its headlights interrupting the inky-black night, to the inside of Jackie Cogan’s 1967 Oldsmobile Toronado, with Johnny Cash’s “The Man Comes Around” providing an evocative accompaniment. “There’s a man going around taking names/And he decides who to free, and who to blame/Everybody won’t be treated all the same,” Cash sings in that unmistakably gravelly voice, and that’s exactly what Jackie does. Called in by the mob to capture who robbed the game so that gambling can begin again, Jackie meets with an unnamed character, referred to only as the Driver (Richard Jenkins), who serves as the mob’s representative in these sorts of matters. Unlike the other criminals in this film—Frankie, with his tousled hair and sheepish face; Russell, with his constant sweatiness and dog-funk smell; Jackie, in his tailored three-piece suits and slicked-back hair; Markie, with those uncannily blue eyes and his matching slate sportscoat—the Driver looks like a square.

He is, like the men who replace Mike Milligan in the second season of Fargo, a kind of accountant, a man with an office and a secretary. “The past can no more become the future than the future can become the past,” Milligan had said, and for all the backward-looking details of Killing Them Softly—American cars from the 1960s and 1970s, that whole masculine code-of-honor thing that Frankie and Russell break by ripping off Markie’s game, the post-industrial economic slump that brings to mind the American recession of 1973 to 1975—the Driver is very much an arm of a new kind of organized crime. He keeps his hands clean, and he delivers what the ruling-by-committee organized criminals decide, and he’s fussy about Jackie smoking cigarettes in his car, and he’s so bland as to be utterly forgettable. And he has the power, as authorized by his higher-ups, to approve Jackie putting pressure on Markie for more information about the robbery. It doesn’t matter that neither Jackie nor the mob thinks Markie actually did it. What matters more is that “People are losing money. They don’t like to lose money,” and so Jackie can do whatever he needs. Dominik gives him this primacy through a beautiful shot of Jackie’s reflection in the car window, his aviators a glinting interruption to the gray concrete overpass under which the Driver’s car is parked, to the smoke billowing out from faraway stacks, and to the overall gloominess of the day.