Text

20 Years of Quentin Tarantino’s Brilliantly Bloody Kill Bill: Vol 1

Defined by its killer soundtrack, striking visual design and engaging, unforgettable characters, acclaimed filmmaker Quentin Tarantino’s senior feature Kill Bill: Vol 1 made its breathtaking debut on October 10th, 2003 and has culminated in persistent acclaim and adoration since. An American love letter to the classic Japanese martial art and Jidaigeki (period) works, especially Toshiya Futija’s 1937 masterpiece Lady Snowblood, the film features the dazzling casting choice in the amazingly talented Uma Thurman as The Bride. Thurman’s role is a mysterious assassin who seeks revenge on her former group of assassins after they left her and her unborn child for dead during her wedding reception. The first installment in the two-part project, which Tarantino considers one whole film himself, sees The Bride travel to Tokyo to take down the viciously skilful yakuza.

As mentioned, Tarantino’s work took the film industry by storm after its October 2003 release. Thanks to its brilliantly executed plot and action-packed sequences with an overall blend of impassioned drama, it attracted countless critical acclaim and audience praise and grossed over $180 million worldwide having been made from a $30 million budget. This turn out makes it one of the director’s biggest successes and highest-grossing weekends. Furthermore, the first volume of Kill Bill rightfully holds an unmovable status in American film. It exists as a work that defines the Western take on the medium as combining thrills with drama and intense character examinations. Tarantino’s writing never misses, pacing the fight/kill scenes alongside the dialogue-driven ones that display character motivation and progression. It additionally offers witty quips to add a dark comedic tone to overall atmosphere of brutality and violence, showcasing the versatility that has helped cement Kill Bill: Vol 1 in the cinephile psyche.

It’s visual design demonstrates some stark and stylised iconography, from costuming to choreography. First of all, The Bride’s iconic yellow and black tracksuit borrowed artistic influences from Bruce Lee’s attire in the 1972 incomplete film Game of Death, written, directed and produced by the martial arts icon himself. Here, Tarantino pays further tribute to the martial art works that inspired his love for watching and creating cinema in every little detail in his own work that are artistically inspired by the efforts of those who defined the cinematic genre. From visual to audio quality, the infamous sound design of alerting sirens which are embedded into the score every time The Bride faces an opponent have become a pop and film culture phenomenon. This stylistic trademark has been replicated and immediately recognised in subsequent films that go on to pay tribute to the work Tarantino created as an act of appreciation himself.

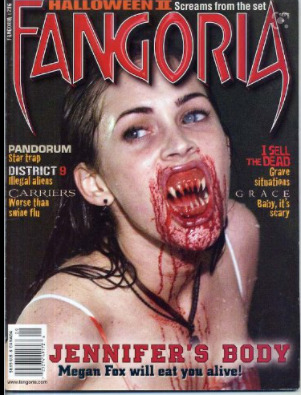

Furthermore, Kill Bill: Vol 1 is also a bold and ambitious execution of Tarantino’s artistic staple of excessive and graphic violence that strays away from gory shock value seen in most modern horror. The feature makes use of buckets on buckets of blood as limbs are shredded off the body and torsos are slashed open by The Bride’s attentive sword work and passion for revenge. This is most evident in the brilliantly tense and climatic climax which sees The Bride take on the Crazy 88, an elite group of masterfully trained fighters against dreamy blue landscapes that illuminate the characters’ shadows during battle. Once we see the fight in the forefront, we are astounded and sometimes repulsed by how each severment of a limb triggers an ongoing spurt in blood. Each spurt immediately follows the other before in some sort of gruesome rhythm until the redness takes up the screen.

This quest for revenge mirrors a hidden desire audiences suppress and, in the case of Kill Bill’s unforgettable protagonist, a brutal and extreme display of ‘feminine rage’. This cinematic notion is structurally characterised as a strive to be heard and fulfilled on a woman’s part, executed by intense and “unfeminine” outbursts of repressed emotion from screaming to physical conflict. As a brilliant female lead dignified with a profound backstory and layered depiction as conveyed in a terrific performance, The Bride is introduced in the first installment as working under a more serene and controlled demeanour that covers her festering feminine rage. Despite a powerful taste for blood leading her every move, the character remains unflustered throughout the narrative, even when she’s engaging in prolonged violent combats and kills. This accentuates her layered characterisation because it offers a harmony between her rageful quest for vengeance and her collected sense.

The character reads as a thorough and detailed portrayal of how there is no force nastier and more persistent than a scorned woman, with audiences relishing in her journey of executing “an eye for an eye” (a more fitting analogy in the sequel). She lets nothing stand in her way of getting revenge and leaves a bloodbath in her wake with hardly a bat of an eye. Through this graphic rhythm of violence interjected into her emotional backstory, The Bride as a central woman in film challenges conventional tropes of a more “well-behaved” and approachable cinematic leading woman. It’s virtually impossible not to immediately align with Thurman’s character and support her. Audiences recognise, understand and resonate with her backstory, identifying the severe betrayal she was a victim of. The unapologetic aggression The Bride showcases in this film is something many women connect to, with many critics suggesting they come to fantasise about doing the same to those (possibly men) who have wronged and scorned them.

Two decades on, Kill Bill: Volume 1 is appreciated as a masterful visual work that encompasses compelling cinematography to showcase its unique character writing and stark violence. It’s thrilling from opening to conclusion with a perfect structural and tonal disposition between the emotive drama, dark comedy and explicit violence. Tarantino’s directing skills that convey thorough character development, memorable iconography and immersive action allow for both compelling expressiveness and decorative appeal, appeasing audience’s need for stimulation and entertainment. Such artistry and storytelling are cherished by cinema lovers, leading to Kill Bill: Volume 1’s everlasting status in film.

youtube

#kill bill#kill bill vol. 1#quentin tarantino#bellatrix kiddo#uma thurman#cinema#film#film analysis#film critic#classic#american film#2000s cinema#movie#Youtube

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Where You Can Find Me and My Writing

Film and Social Politics on Medium: https://medium.com/@rosietibbs-co-uk

Film on A Rabbit's Foot: https://www.a-rabbitsfoot.com/

Film on Far Out Magazine: https://faroutmagazine.co.uk/author/rosietibbs/

Film on Best of Netflix: https://best-of-netflix.com/author/rosietibbs/

Letterboxd: https://letterboxd.com/okcoolros/

Journalism Twitter: https://twitter.com/wordsbyros

Overall Portfolio: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1-wh_r_0lBvmRvUlhrO7SZY9el35McbIMWuUi6UC-g_8/edit

0 notes

Text

Goodbye Ghosts and Killers. Hello Politics and Commentary: Horror in the 2020s

Spoiler Warning for Get Out, Candyman and Squid Games. Some spoilers refer to racial tensions and attacks/murders.

What is it about horror that draws so many people to it? What fears shown in horror scare people the most? Expected answers would involve getting to watch dumb teens get slashed one by one or unworldly forces terrorising a family during the night. The horror genre has given a lot of different scares over the years- vampires in gothic castles to evil computers in a teen girl’s bedroom chilling audiences to the bone. As time goes on and external factors change, the genre may fully delve into something a little too realistic to get some fresh scares. Recently, the contextual background of our own political climate has been inspiring horror screenwriters’ imaginations and has been bleeding onto our screens. Rather than masked knife-wielding maniacs making us jump, the 2020s may be the decade that sees the torch handed to ghastly representations of political figures and events.

Films, similar to most mediums, can be documentation of current events. Our culture is always influencing creatives and horror is beginning to demonstrate this. Each era or trope of horror can be tied to a decade or two. The 70s brought us chilling supernatural stories and exploitation films, the 80s and 90s gave killers Jason and Ghostface the spotlight, and the 2000s to 2010s concerned themselves with torture porn. Now, social allegories are looking to be the latest craze, with recent horror exposing societal ills in metaphors. Writers and directors are utilising their stories and mise-en-scene as tools to execute social commentary. It’s important to note that while these political metaphors are only now becoming popular, the genre has dipped into this before. Profound directors such as Romero and Carpenter steered some films to critique societal issues: Romero’s Night of the Living Dead attacked ideas of civilisation while They Live was Carpenter’s disapproval of excessive materialism. But now politics is heavily and frequently reaching the visual arts in correlation with an influx of widely absorbed social justice.

One figure who can be credited with springboarding socio-political horror is Jordan Peele, whose award-winning screenplay and complemented direction in Get Out (2017) referred to racial issues in society. The film received accolades and praise for exploring and performing the psychological horror of racism in America. In turn, it generated not only an intense emotional reaction as horror does but also a display of critical evaluation among audiences in their reflections. Get Out’s terror didn’t reside in something shallow and familiar in horror, but instead something powerful and familiar in societal structures and attitudes. Chris becoming a victim of a psychological hijacking as a means of exploiting his traits was Peele’s outlet to communicate the disgusting culture vulture mistreatment that black people experience. There was also a critique on white liberalism and pandering to black people shown in the white family, lacing the film with some painfully true aspects.

Peele contributed to another racial allegory featured in the horror genre, as he wrote and produced alongside director Nia DeCosta in her re-telling of Candyman (2021). This film told a story of a cursed killer breaking through the gap of life and death to get his victims, but also a story of racial injustice and tribute to the victims. Candyman’s origin displays prejudice and unfairness, as he was murdered by a white mob after being accused of harming a white girl, not proven to, accused. This echoes the devastating murders black people fall victim to at the hands of police once those officers decide they’re a threat over nothing. The hook (pardon the sudden pun) of Candyman’s curse is that you have to say his name. As Candyman had a pushed back release due to the Covid pandemic, it came after the murder of George Floyd and the BLM marches that followed-where Say Their Name is a verbal signal of acknowledging the victims of racially charged murders. The story reflects the Black Lives Matter movement in its events and characterisation, further cementing horror blending with political landscapes and social critiques which serve as the backdrop for its stories.

Presidential campaign debates and elections can be harrowing events to maintain track of. The sheer hypocrisy and inconsistencies one has to endure when watching the televised debates always proves to be a challenge and concern for America’s future. If this is the case, surely you would switch the TV off and turn over to a film as a means of escapism instead? Not if you choose to watch The Purge franchise, as the sequels to the original 2013 flick are a hyperbolic presentation of American political leaders and climate. These films follow an annual night of all legalised crime, justified by an alleged claim of “purging” civilians’ negative emotions, however, the sequels show how this is a false cover-up. The elite population take this night as an opportunity to murder minorities; the lower class, POC, basically anyone who does not suit their narrow-minded manifesto. The government see the purge as an opportunity for population control and a sick case of natural selection to keep America “great”. The third instalment, Election Year, came out during one of the most controversial and discussed presidential elections- Trump v Clinton. Since Trump’s unfortunate win, The Purge sequels that followed only became more on-the-nose and extreme with their political satirical commentary, paving the way for more representations of politics in horror that, given the current political climate, will stop seeming so over the top.

What does torture horror have to say on the matter? Darren Lynn Bousman and Josh Stolberg provided an answer to this with Spiral: From The Book Of Saw, a spin-off to the Saw franchise. Despite the misplaced classification of the previous films as shock value, buckets of gore driven torture porn, the franchise has always held political and philosophical undertones (the whole sixth film is a massive f you to the American health care system for being heavily commodified), however, this spin-off was less under and more overtone. Chris Rock plays a cop who finds himself in a web of a Jigsaw copycat’s sick games, where seedy corrupted officers are murdered for shooting innocent POC and the witnesses who can get their jobs taken away. The traps aren’t testing the officers but instead simply punishing them for abusing their power in such vile manners. Likewise to Candyman, this film got pushed back a year due to the pandemic and so viewers watched it with George Floyd in their minds, something that gave the twist ending an unforeseen kick in the stomach of realism.

If you spent any time on Twitter last year, it’s safe to say you know what Squid Games is, even if you didn’t watch it. The smash-hit and record-breaking Netflix original series constructed a gripping horror story using class inequality as a value. A group of players crippled by debt compete in childhood games with a deadly twist in order to win a mass sum of cash. The situation is a literal matter of life and death, correlating with the metaphorical one debt creates. The show’s scare factor was distributed between the “loser’s” deaths and the uncomfortable but powerful portrayal of class division influencing concepts of humanity. The death scenes in the games are of course chilling, but that cannot compare to the horror of the players killing one another to get rid of too much competition. Squid Games held a mirror to our capital-mad society and its detrimental flaws, in turn, displaying how horror is employing social commentary in the 2020s.

Social commentary horror doesn’t appear to be letting up any time soon as we move into the new decade, with the Covid pandemic possibly sparking new ideas for horror stories of infections destroying civilization. A strong chance of a new wave of zombie movies that are more hard-hitting given the context is therefore on the cards. Peele has to our screens with his mysterious feature Nope and a remake of capitalism satire The People Under The Stairs, so it looks as if the 2020s will be brimming with horror grounded in political discourse.

#horror#horror movies#scary movies#film#cinema#film analysis#film critic#film studies#social commentary#politics

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Phenomenology and Cognitivism of Kon’s Perfect Blue

Introduction

Psychological thrillers are stylistically designed to create emotional responses such as suspense and unsettlement, using their portrayals of distorted mental perceptions and a dissolving sense of reality. This formula attracts interpretations under cognitive theory; an analytical toolset that concerns itself with the mental reactions that carry out during spectatorship, and Phenomenology: an assessment of how film creates sensations during the viewing experience. Satoshi Kon replicated the psychological thriller’s credentials in his 1997 animation Perfect Blue, a cult classic that follows the story of a pop idol who finds her sense of reality slipping as she is stalked by a possible murderer. Perfect Blue corresponds with both the psychological thriller and both phenomenology and cognitive film theory as a result of the thematic values lacing its story and visuals. Kon’s narrative consists of perception, identity, the distortion between reality and illusion, and finally psychological distress as its thematic values. These story elements being explored generate cognitive and emotional activity in spectators, ranging from character alignment to responses of fear and confusion.

Perfect Blue’s Cognitivism: Narrative and Visual Style

Furthermore, identity and perception are explored cognitively through the story element of Mima acting in her first TV performance in a psychological crime show; the genre echoing the tone of the film. Mima’s character in the show experiences a traumatic rape and as a coping mechanism, changes her identity by creating a new persona free from the trauma. This stylistically echoes what is happening to the real Actress Mima in real-life as she too is experiencing issues with establishing a set and true perception of her own identity. Mima’s character’s first line “Excuse me who are you?”, can serve as a demonstration of this because audiences can interpret this as her not only asking the other TV character but also herself as her two personas clash. As a result, this illustrates Kon’s psychological presentation of both identity and perception in Perfect Blue’s narrative; not only is the real Mima experiencing her identity conflicts but the character is she portraying in the aftermath of this identity split is as well, in turn elevating the theme and unsettling the audience. Kon combines identity and perception as cognitive elements with conventions of the psychological thriller in the narrative reveal of someone imitating Mima’s identity online. Mima is shocked to discover an imposter has taken her identity and is writing what they want Mima to write and doing what they want Mima to do, further creating a severance in her identity and perception as people take the imposter’s writing as veracity to who she is. This mysterious imposter is later revealed to be Mima’s psychologically disturbed stalker, this addition to the story signals its classification as a psychological thriller due to its unsettling nature. This creates an emotional response of fear for Mima’s safety as well as a disturbance in spectators, and as it is done as a straight narrative element rather than the use of visuals it provides support for Plantinga’s claim that “narrative scenarios are the most important structuring mechanisms in the movies” (2009).

Perfect Blue’s classification as a psychological thriller is further emphasised in the murders of people around Mima. The identity of the killer remains unknown for the majority of the film, creating a sense of mystery, however, an answer is suggested in that of Mima who we see murder a photographer for exploiting her body This leads to an implication that Mima is the one committing all the murders, as “the skilled filmmaker may provide intentionally ambiguous or contradicting affect cues, typically for specific effects such as the elicitation of suspense or curiosity” (Plantinga, 2009), meaning that spectators have been invited to pin the murders to Mima even though they only have the confirmation she has committed this one. During the brutal killing, Mima is juxtaposed against the pop idol version of herself who is projected behind her. This is effective as it demonstrates the two identities existing at the same time as a suggestion of what created such an inner turmoil and disturbance that caused her to allegedly commit these murders. This element of the visual style being used to solidify the themes can steer audiences to align these personas with the violent act as an understanding of who Mima is, even though this contrasts a great deal with how Mima was portrayed in the beginning. Mima begins to question herself as innocent of the other murders, further emphasising her inability to recognise who she is and her actions, in turn, leading spectators to struggle to rely on Mima to assist in them aligning herself and her actions.

Kon combines his thematic values of identity and perception with that of the distortion between reality and illusion, as Mima’s loss of identity elevates the loss of reality and immersion into the illusion. As previously mentioned, Perfect Blue’s narrative involves a TV show, called Double Bind, being shot within the film with Mima having a minor role. This creates a sense of reality and illusion being blurred because spectators have to focus and cognitively align what is Perfect Blue’s story and what is Double Bind’s, something that poses as challenging as scenes that appear to take place in Perfect Blue’s story are later revealed to be the shooting of scenes from Double Bind, with no sharp and separating editing from real life to the film being shot. The story world of Double Bind shares themes with Perfect Blue which steers this confusion in alignment, one notable scene that exemplifies this is the one in which a private investigator claims that one fixed persona is an illusion and that illusions cannot come to reality, fitting with what Mima is struggling within her loss of identity and so audiences can interpret this as reality, however, it is immediately revealed to be a scene from the film and so illusion. This narrative element, as conveyed through the visual style confuses the audience who can struggle to align Mima’s reality with the illusion of the fictional world she is acting in.

Overall, a cognitive inspection of Kon’s Perfect Blue as supported by Plantinga’s interpretations and criticisms pioneers a landscape of thematic evaluation, genre, narrative and visual style as a means to identify and understand how spectators are mentally engaged to create alignment. Plantinga’s emphasis on a film’s narrative is the key source of cognitive activity applied to Perfect Blue as a result of its thematic values deriving its meaning, despite being communicated stylistically through its visuals for audiences to use.

Perfect Blue’s Phenomenology: Narrative and Visual Style

Kon’s Perfect Blue can be interpreted not only using cognitivism and its mental activity but also phenomenology’s emphasis on sensory qualities during viewership. Sobchack expresses how “contemporary film theory” has been neglectful of “cinema’s sensual address and the viewer’s corporeal material being” (2004), severing the mind and body in the process. Whilst Plantinga would observe Perfect Blue using associations of mental engagement as proposed by the narrative and visual style, Sobchack would describe the sensations of both the film and its effect on audiences as a “phenomenon”, meaning it is an experience. When phenomenology is applied to film, it concerns itself with the worldliness of a film and how spectators are steered to perceive this world the director has created, as when spectators watch a film they engage with the film world as if it were their primary environment. Perfect Blue’s world is kept in the spaces of the TV studio, the subway, Mima’s room and occasionally the pop stage; spectators become immersed in Mima’s situation as carried through the spaces she occupies and is consistently reacting to what is going on. Kon has assigned these areas as the key spaces the audiences’ perceptional field is held to, thus, their understanding of the film world is constructed by the frequent presence of these significant spaces. The order of presentation of Perfect Blue’s film world is dependent upon its narrative and this as an overall and cohesive playing out of events is what engages spectators with a bodily experience. This is supported by phenomenology’s key claim that we perceive experiences as wholes as opposed to parts, therefore, when spectators are perceiving and experiencing a film they do so through a consistent story made up of a cause and effect chain of events. Sobchack speaks to this in her writing, outlining how “the sensuous is located in the events of the narrative” (2004) and signalling phenomenology’s emphasis on a compilation of parts to create an overall experience. In this, Sobchack echoes Plantinga’s interpretation of narrative serving as the key provider of perception and understanding for spectators, however, her interpretation relies upon an engagement with a primary engagement of feeling in experiencing film using senses whereas Plantinga advocates for narrative as endorsed by secondary cognition.

Phenomenology as a lens for watching Perfect Blue would invite spectators to shift focus on which senses are being engaged as the driving force of the film experience, this shift being sight to touch and more bodily sensory reactions. Sobchack comments on this engagement of these two senses in the film viewing experience, “our vision and hearing are informed and given meaning” (2004), illustrating how the perception and understanding of a film are tied to sight and sound as vital tools. This would be exemplified in Kon’s use of visuals, most notably the symbolism of Pop Idol Mima’s reflection creating contrast against Actress Mima which, as previously analysed, is important in spectator understanding of the film. This use of visuals taps into spectators’ senses of viewing to make sense of Perfect Blue’s narrative, this is also paired with hearing as a sense when spectators listen to the dialogue of “I’m the real Mima”. Essentially, spectators are invited to use their bodily senses of sight and hearing as tools for perceiving Mima and what she is experiencing; steered by Kon’s objectives in storytelling. One could propose that Kon’s visuals are phenomenological descriptions used to create meaning, ones that his spectators are trusted to perceive and interpret using their own sensuous understanding as a way to experience his story in an ideal manner. Cognitivism is the methodology that would highlight the significance of Perfect Blue’s visual symbolism, as it generates stimulation for alignment and identification, however, Sobchack encourages perception and engagement that transcends this, as “we do not see any movie only through our eyes”, but rather “feel films with our whole bodily being” (2004). Phenomenology calls for an emphasis on the body and the sensations carried through it, thus, when one is watching Perfect Blue as a phenomenon they would do so without reliance on sight alone.

Kon steers his spectators to engage with their sensuous being to rather extreme levels, notably due to Perfect Blue’s status as a psychological thriller which serves as the core for its choice of meaning, therefore spectators will have their senses combined with some rather unsettling experiences. A significant example of this is the scene where a psychologically distressed Mima cuts her hands using glass to make them bleed; an image that is effective due to its connection to the senses. This is due to how the visuals of sharp glass penetrating Mima’s skin and drawing blood call to the spectators’ senses to live the painful experience themselves, an objective shot of cut skin and bloody hands causes spectators to understand the feeling of this sensation on their own skin. Sobchack speaks to this by stating “our lived bodies sensually relate to things that matter onscreen”, demonstrating explanations for how the film experience of watching Mima’s skin as it is cut open has a visceral effect on the spectator’s body. She progresses with this proposal by arguing how “we see and comprehend and feel films with our entire bodily being, informed by the full history and knowledge of our sensorium” (2004), meaning spectators perceive and respond to films with a sensuous landscape that transcends just sight as exemplified by responses to this unsettling scene.

To conclude, Phenomenology provides an understanding of spectators’ bodies and senses during the experience of watching Perfect Blue. One can use this methodology to interact with the sensory realm of film spectatorship, free from claims of a mind and body separation and instead can combine the two. Perfect Blue, likewise to cognition, relies on its narrative and visuals to engage with spectators’ senses. Mima’s experience as communicated through the story and its visuals are where bodily reactions derive from and is supported by its genre of a psychological thriller which influences how it is perceived by consisting of intense and complex subject matter.

Bibliography

Plantinga, Carl R. Moving Viewers: American Film and the Spectator’s Experience. E-book, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009

Sobchack, Vivian Carol.. Carnal thoughts: embodiment and moving image culture. Berkeley : University of California Press, c2004.

#perfect blue#satoshi kon#film analysis#film critic#film essay#phenomenology#cognitive theory#film studies#anime#90s

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analysing The Debate on Controversial Films And Filmmakers’ Place in Contemporary Society

I. Introduction

The film industry is in a never-ending dialogue of complicated discussion and debate, ones that question what counts as cinema and what doesn’t, or ones that evaluate ways spectators consume film to locate the most ideal. When observing discussions on film in very recent years, a topic that has been the core of a mass division among academics and everyday fans is the dispute of whether or not we can separate art from the artist when consuming and interpreting films. As audiences, we can do more than just simply watch films passively. We can connect with the style techniques of the story, visuals and characters in an emotional realm, in turn aligning our own identities and outlooks with the films we choose to watch. Our favourite films are an exegesis of our passions and interests in life, something we share with others to convey who we are and generate this same interest in others.

But what do we do when those favourite films we watch, love and connect with are made under controversial means or by controversial people who have displayed a severe absence of morals? Suppose audiences classify a film or a director’s filmography as representing parts of their identities and passions. Building from this, one has to ask do any problematic or corrupt elements tied to either the film or director also represent them.

These questions have been dissected and analysed in both academic and casual film-orientated discussions, with critics attempting to compromise a director’s unethical actions in real life, such as abuse or bigotry, with their artistry in quality filmmaking. However, as Elizabeth Shaffer cites, despite “the intersection between art and morality” being “a huge topic…the majority of scholarship dedicated to what happens when bad people make good art has stopped before posing a solution” (2019, Page 2). This shows the difficulty in initial attempts to approach this discussion, as the binary opposition between a “bad” person constructing “good” art effectively establishes the challenging compromise of the situation. The dominating element of our morality and emotional responses to enjoying a good film is when we know that the person who provided it for us does not uphold moral values. This can prove to be too close to home for a large number of people, and thus, a “solution”, as Schaffer says, is avoided for the time being. The lack of morals or ethics in question can reside in the techniques a director uses when making a film. A prominent example of this is Stanley Kubrick, who submitted his main actress Shelley Duvall to borderline abuse when filming The Shining. The matter becomes more complicated when observing how they can also be found in a director’s life outside his art, such as Roman Polanski, who made quality contributions to filmmaking in Rosemary’s Baby. However, the act of rape he committed against a minor ten years after the film’s release has clouded every move he has made since.

Taking knowledge of both these situations into account, film critics and consumers are faced with the challenges and dilemmas that come with this debate. Shaffer references how, when she consumes and critiques art pieces, she is “operating wholly under my (her) own moral compass and aesthetic taste” (2019, Page 2). These are the tools needed to decipher a ‘bad’ person who has made ‘good’ art, a process that incorporates issues of objectivity and subjectivity. The interpretation that art of any medium can be objectively good or bad is one that has been tackled and dissected consistently throughout art criticism. Films like The Shining and other Kubrick works are deemed objectively good, masterpieces even, by film scholars and fans. However, one can find that his actions during the filming of The Shining are subjectively bad due to a varied classification of what counts as abuse and perfectionism. One’s aesthetic taste can direct to regarding The Shining as a ‘good’ piece of art, and their moral compass can contrast this by citing Kubrick as a ‘bad’ person, but not a ‘bad’ artist.

The relationship between art, artist and consumer is challenged and explored in the debate of separating art from the artist. Some propose that you can separate art from the artist because of what art can mean to those who consume it, overriding whatever the artist did wrong, that art belongs to those it is made for. However, this is counteracted through the emphasis on the artist as the one who put time, creativity and effort into composing whatever medium of art they created. Some take the perception that “art is not created by the people. The poet, composer, or painter is the creator and can do as he pleases with his creations” (Wilkinson, 2010, Page 18), claiming the artist is the sole creator and should be held accountable for anything their art achieves. This dynamic between the creator, what they create, and the audience they create it for is a frequent addition explored in critical and casual readings on the matter.

I would propose the thesis that whilst a prominent majority argue that a severance between art and artist is possible, contemporary analysis on the matter signals mostly to the opposition; severance between the two cannot be done. I will be analysing academic works and casual film fan posts using CDA, hoping to identify the thematic values of both sides to draw a conclusion on the matter.

II. Kubrick and Duvall: When The Artist Goes Too Far For His Art

Kubrick’s enlivenment of Stephen King’s novel The Shining was released in 1980 as the 11th feature in the director’s filmography and his first contribution to horror. Despite an initial wave of criticism for tampering with the book upon release, there has been a re-evaluation. The film is now heavily praised in both horror and overall filmmaking. It is cited as one of the greatest horrors and films ever made, being ranked the 75th greatest film of all time in the Sight & Sound directors’ poll in 2012. As is the case with most globally iconic pictures, The Shining’s filmmaking history is branded in alleged trivia and stories, ones that are rather challenging to hear. The central point of focus in these stores lies in the performance of Shelley Duvall as Wendy Torrance, a performance that has been panned and attacked by both critics and film fans and resulted in Duvall receiving a Razzie award for worst performance.

In recent years, Duvall’s performance in the film has been reassessed and interpreted as an unfortunate repercussion of Kubrick’s perfectionism bleeding into his directorial methods. To achieve what he decided to be a believable performance in psychological horror, Kubrick tarnished the wall between reality and pretence by commanding the cast and crew to not show any sympathy for Duvall and asking them to ignore her completely. He placed all praise and encouragement on leading actor Jack Nicholson while submitting Duvall to criticism and verbal disappointment. Kubrick actively tried to maintain Duvall’s high-stress levels on set, all for the sake of art in his quest for an authentic performance on Duvall’s part, who channelled her emotional reactions into her acting as seen in the film. Duvall’s health and well-being deteriorated under this quest for art she did not consent to, evident in how “this intensive training of the mind with isolation and “torture” for the role was too stressful for Duvall to bear, who started losing hair and was “in and out of health”, having been pushed to the very threshold” (Sur, 2021).

Kubrick’s mistreatment of Duvall during the filming of The Shining has generated consistent controversy and debate on whether such actions are ethical when done for the objective of quality art. Is it morally right that Duvall was forced to endure psychological torture every day on set, with the only available outlet being her performance as Wendy just “to appease the filmmaker’s expectations regarding the character”? (Sur, 2021). Contemporary film culture appears to neglect Kubrick’s directorial methods. On March 31, 2022, the Razzie committee officially rescinded Duvall’s nomination, stating, “We have since discovered that Duvall’s performance was impacted by Stanley Kubrick’s treatment of her throughout the production”.

III. Polanski

The issue of separating art from its artist to enjoy it freely can also derive when aligning the artist’s antics alongside the quality of their official work. Polish-French director Roman Polanski contributed to cinema history in his adaptation of Ira Levin’s psychological novel Rosemary’s Baby, released in 1968 and cementing the director’s place in filmmaking. Likewise to Kubrick’s cinematic take on The Shining, Rosemary’s Baby received critical acclaim upon release and continues to this day, being ever credited as one of the greatest horror films of all time. As high quality and praised as the film rightfully is, spectatorship and interpretation of the overall film and its subject matter were compromised upon Polanski’s conviction after raping a minor during a photography session in 1977. In an attempt to avoid his sentencing, the director fled to Paris, where he received protection and has since avoided repercussions for his actions. Despite his crimes, Polanski continues to make films that are widely watched and well-received, even obtaining a standing ovation at the Oscars in 2002, exactly 25 years after his act of assault.

Observing Rosemary’s Baby’s thematic material and characterisation under this knowledge of Polanski generates unsettling and confusing outlooks. The film is about the physical and psychological abuse of women and the exploitation of their bodies. It is evident in how Rosemary is used to carrying and birthing the antichrist for a Satanic cult and is gaslit whenever she voices uncertainty or resistance. Under the interpretation of the film critiquing women being exploited in this manner, one can only conclude this narrative is hypocritical and perplexing when this is exactly what Polanski did himself to a female child. However, suppose the interpretation of a critique is removed. In that case, the film automatically becomes laced with a sinister and sickening undertone, almost as if Polanski is manoeuvring the film to be an exercise of his outlook on women. As mentioned, the film’s plot is adapted from a book; while Polanski did not write the actual story, he still chose to bring it to the big screen. It is even stated that Polanski contacted Evans immediately after finishing the book to tell him it was an “interesting project” he would love to adapt.

After consideration and any evaluation of this mass context when watching Rosemary’s Baby, separating the art from the artist soon becomes unobtainable in this example. Audiences sometimes struggle to stomach Polanski’s work, so much so that there have been incidents of direct action against him, such as “feminist groups in France have regularly staged protests against Mr Polanski, including outside a retrospective of his career at the prestigious Cinémathèque in October 2017 (Alderman and Peltier, 2019).

IV. The Debate Of Separating Art From The Artist In Readings

Proceeding from the outlines of prominent examples in this debate, there have been proposals that separating art from the artist in consumption is a possibility, thus, arguing one can enjoy The Shining and Rosemary’s Baby for the highly-rated contributions to their craft that they are on the surface.

Writing for The Daily Free Press, Eden Mor tackles the challenge of disassociating the two with an immediate establishment and admitting that she felt guilty when consuming art from a problematic creator. This emotional response of guilt is a frequent occurrence in the discussion around separating art and the artist, as well as one alleged reason that it cannot be done. Therefore, one can identify emotions of guilt as a theme in this debate and research it. However, Mor attempts a counteraction to this by asking if there is logic and rationality in the argument that you can’t separate the two, does it “make sense to associate…actions…with the art?” (2021). This standpoint varies on the example to which we are applying it; some artists have committed acts that are a lesser evil when compared to others. Taking this standpoint under the hypothetical answer of no and applying it to Polanski’s films, it is possible to separate the artist from his art. Focusing on Rosemary’s Baby following the outline of context, one has to consider that Polanski isn’t responsible for creating the story, characters and messages. The author Levin has to receive the credit for what the film presents to its audiences, as it was his imagination that conjured up Rosemary as a character and the events she engages with. Mor alludes to this consideration by mentioning how countless people are paid when one consumes art, not just the one director who may be “the face” but “there are hundreds of other people profiting” (2021). When watching a film, one must consider that despite the head figure of a director leading the actors, what you see on screen can also result from the actor’s interpretation of the character. Mia Farrow (Rosemary) is the one who pours emotion into the role to, in turn, generate an emotional response in audiences. She deserves just as much credit for bringing Levin’s character from page to screen to life as a result of her chosen craft as Polanski does for his. Thus, the incorporation of other professionals involved in a film negotiates to grant a sole figure full credit. Mor expands her stance on the matter by bringing it directly to the audience, who are responsible for separating the art from its artist. Mor communicates her belief that “there isn’t a yes or no answer to this question. The art which you consume — whether it be movies, TV shows or music — is your own decision” (2021). This illustrates a conclusion offered to those undecided on the debate, one that can be explained as separating art from the artist exists as a “personal decision” (2021). Overall, Mor’s contribution to the matter is concerned with a reason as supported by a broader picture being evaluated, one that hands responsibility to audiences following this objective and thorough inspection and illustrates the debate as something that cannot be decided on without this.

Any counteraction to this claim is never far behind, evident in Ella Adams’ commentary on the matter as read in The Appalachian. Adams assures an overall contextual awareness in the opening of her opinion article, made clear in how she acknowledges social media’s placement as “the conversation on whether you can separate the art and the artist is hotly debated in social media comment sections whenever a new scandal involving a popular artist pops up” (2021). When tying this to the two established case studies, this is evident in film Twitter accounts posting about Rosemary’s Baby on the anniversaries of its release, where the comments will be split between praising the film itself and mentioning how Polanski is a paedophile and confusion about why the film is being posted due to this, combated with the debate. Adams echoes Mor’s interpretation in highlighting that “art is a personal expression of one’s perspective of the world. A piece of art’s relationship and meaning to its creator is exactly what makes it art.” (2021). However, Adams uses this element of the debate to provide a counteraction that you cannot separate, stating “because art is so personal…filmmakers and other artists cannot be separated from their creations” (2021). This is relevant to both case studies as a personal tie is employed. This element of personal expression serves as a further theme in the discussion’s research. Kubrick’s take on filmmaking and directing his cast is the controversy surrounding his work The Shining, and Polanski’s crimes bleed easily into the narrative and message of Rosemary’s Baby. When taking these examples into account, it can become rather controverting to propose you can separate art from the artist because of how much of the artist exists in the art. Adams progresses with this reasoning by highlighting the issue of income and profit as derived from art consumption, “art can also be a means of income. By supporting an artist’s work, you are supporting the artist themself,” when audiences consume art, they “support his (the artist) career and ability to create more content” (2021). This point of capital given to the artist, as another key theme, is a prominent addition when observing the matter of audience consumption, the fact that artists who have done wrong gain financial aid through being distanced from their work for the sake of consumption and enjoyment create a great deal of unsettlement. Adams’ argument is centred around this aspect, that the power that comes with the capital these artists receive outweighs any other claim to separate them from their art. Therefore, a difficult compromise is proposed when seeking any outcome to the debate.

Commenting on the debate in Triton Times, writer Reid Corley opposes the arguments similar to those seen in Adams’ piece with an immediate establishment of his ‘you can’ stance. He writes, “there must be a separation of art from the artist, especially given the current era we live in”, highlighting how he claims to be evaluating this stance under contemporary attitudes, an interesting thing to assure as most examples in this debate took place decades ago. Corley navigates his argument with a hierarchy of art consumption, stating that if we wish “to maintain the diversity of film and appreciate the artistic passion and creativity of individuals for the sake of the product, we must employ separation” (2019). Thus, Corley is proposing we place an art’s display of passion and creativity above artists’ actions. He progresses with the acknowledgement of “the backlash people receive from supposedly “endorsing” artists’ behaviour” when consuming their art, something fans of The Shining and Rosemary’s Baby are familiar with as the directors’ actions heavily cloud the films. However, there resides the opposition to this in Corley’s claim that “the appreciation for a piece of art should not indicate or imply the endorsement of the morality and actions of the artist”, thus, outlining the perspective that consuming and loving art has no place in being tied to supporting artists’ actions. This is a clear and precise negotiation of the attitudes as shown by Adams and others in perceiving art to be a personal exegesis of its artist. It relies on the ability to perceive and interpret the art purely on what the art is, not what its creator did or said. It is implied that Corley separates the two inevitably and with no further consideration, conveying that the art and whatever it is expressing is his biggest priority. Corley adds to this argument in an acknowledgement of others who contributed to the body of work, claiming that “to throw out an entire work for the sake of the involvement of one person is unfair to the thousands of others who work on projects” (2019). Here, Corley is supporting the previously outlined proposal that by dismissing Rosemary’s Baby, one also indirectly dismisses the effort Farrow put into her title performance, which is unarguably unfair to her. Corley strategically concludes his stance piece by communicating his standpoint that in claiming you cannot separate the art from its artist, one is employing the artists’ crimes as a measurement of art, something he perceives as wrong because “if we continue to dig up the crimes and vices of artists and use that in our judgment of art, we are openly evading satisfaction and pleasure from the artistic expression” (2019). In his conclusion, Corley argues for sake of enjoyment and remaining unbias in consuming and interpreting art because “it is not only necessary but imperative we establish this division” (2019). The division in question is between what a piece of art can bring and anything immoral its creator did. Overall, Corley’s verdict on the matter emanates from focusing on art specifically and what it can provide for audiences.

When conjoining his opinions with the case study films, one could conclude that Corley would advise watching The Shining under the analytical scope of what it shows about filmmaking and storytelling, to subtract Kubrick’s actions from the equation and instead recognise how the film represents a great deal of what makes visual horror. This would mean not even considering any information of what happened during filming to create the final product as it brings nothing to the final and ever-present imprint or messages the film has in its overall craft. This would be likewise when observing Polanski and Rosemary’s Baby, in that one who is consuming the film for the piece of film art it is should do so in the tunnel vision of its commentary on false pretences in seemingly prestige conservative societies and women’s liberation. However, as Corley emphasises the importance of art’s potential messaging from an isolated perspective, he falls short in considering the financial gain problematic artists gain from this and the power this provides. This, in turn, subtracts objective analysis of the debate under all potential arguments.

Ashley Griffin contributes to the discussion via OnStageBlog, where she opens rather heavily and emotionally with a reference to Dylan Farrow’s open letter about the abuse she endured at the hands of her filmmaking stepfather, Woody Allen. Griffin highlights how in the letter, Farrow asks, “What’s your favorite Woody Allen movie? Before you answer, you should know: when I was seven years old, Woody Allen took me by the hand and led me into a dim, closet-like attic on the second floor of our house. He told me to lay on my stomach and play with my brother’s electric train set. Then he sexually assaulted me.” (1994). The section of the letter Griffin focuses on strategically ends with Farrow’s statement, “Imagine she spends a lifetime stricken with nausea at the mention of his name. Imagine a world that celebrates her tormenter.” (1994), which sets up both the tone and the stakes of the piece and the debate. Using this personal letter, Griffin is transferring the heavy emotional burden that resides in the debate of separating art from the artist, something she accentuates by mentioning her own abuse to develop the tone and stating how her experiences led her to decide “maybe I’m the perfect person to have this conversation about separating art from the artist” (2021). This emotive weight carries through the psychological abuse Duvall suffered in order to create a character in The Shining as well as the trauma Polanski’s young victim is now left with; Griffin makes sure to acknowledge this in writing “people who have experienced abuse and, because of their experiences, are triggered and forever impacted when the artist is ignored so that their art can be untarnished” (2021). Griffin emphasises the consideration that “there may not BE a way to have a truly neutral discussion about it”, proposing there are minimal opportunities to be objective, proposing an answer to why many written takes on the matter fail to be.

However, she does take a moment to consider the separation is a possible stance, expressing the claim that “but if every artist has to have a perfect, upstanding moral character we’d never consume art again. No one could live up to those standards” (2021), a statement she does agree with “to some degree” (2021). As a method of compromising with both sides, Griffins argues for informed consumption because, in her eyes, “there’s a difference between censoring something because of a disagreement about the content and censoring because the creator is a bad person” (2021). This conveys how Griffins is distinguishing the standard responses to problematic art made by a problematic person when the root of the problematic classification can be varying. To Griffins, one has to recognise and assign where the controversy lies in the consumption of a piece of art, as this can influence the issue of separation. This could be interpreted as being directed to the emotive and intellectual responses audiences make to art, meaning that if the art itself is problematic in subject matter, then it calls for censorship easier than if the artist were to have committed a problematic act. Therefore The Shining has the potential to remain consumed and praised because it is not problematic in the subject matter. Instead, it is a well-told horror story. However, Griffins finalises her own personal stance with a clear assignment of guilt to herself when consuming art she knows to be made by a controversial figure. She states how she “can’t help feeling a bit icky” (2021) whenever she engages with the art, and this is something she claims is “not an intellectual discussion I have with myself. It’s a gut response” (2021), thus, proposing the response is instinct over intellectual evaluation. This can relate to the case of Polanski in that Griffins would be unable to watch Rosemary’s Baby or any of his other films without a fight or flight response of negative feelings stemming from the knowledge of his paedophilia, thus, implying that separation between art and creator is virtually impossible due to this inner and natural emotional response. Griffins is clearly centring emotion in her piece and, in turn, looking away from a rational standpoint which is an occurring theme in the online discourse on the matter.

Unlike pieces previously analysed, Griffins draws attention to an outer audience and references opinions and interpretations other than her own, stating she recognises “those who are most willing to do mental gymnastics to justify continued enjoyment of works by newly revealed problematic creator” (2021). This highlights the potential strategy that has kept figures like Polanski free from persecution despite his crimes; film consumers connect to certain works to such a strong degree that repression and negotiation follow as cognitive responses when faced with any immoral acts committed by the film creators. Through this statement, Griffins acknowledges the intimate relationship between creator and consumer and the sphere of art reception. She suggests that emotional ties to a visual piece of art can override facts surrounding the artist in her argument; people push themselves to repress the knowledge and guilt to enjoy art. Griffins diplomatically follow with the aftermath of this repression on the audiences’ part, as she connects support with helping artists hide as through this repression when consuming, “money is going into their pockets…their power in the industry is strengthened” (2021). This is offered as a direct consequence and criticism of separating art from the artist; to make this severance means to allow abusers such as Polanski to still flourish under financial aid. In her conclusion, Griffins advises art consumers to search out alternate methods of consuming art and hold people accountable rather than cancel, as “if you do want to continue consuming a problematic artist’s art, find ways to do so that won’t financially profit them” such as using a library to take out films. A further piece of advice is to counteract any controversy in artmaking by making “your own good art” as “that means it’s your turn to make a platform for yourself” (2021). Overall, Griffins’ articulation on the debate of separating art from the artist is one that exists between an intimate and first-person experience as well as an exterior examination of what the majority do to ensure separation.

In 2018, Constance Grady opens her piece titled ‘ What Do We Do When The Art We Love Was Created By A Monster?’ with a direct and potential answer. She writes, “One of the common answers to that question has been repeated so often it has come to seem as though it’s an ontologically self-evident truth: You must separate the artist from the art”(2018), conveying how this side of the debate is treated as one that is non-negotiable as it is a universal ‘truth’. She continues by including how “separating the artist from the art, this argument goes, is the best way to approach all art, no matter what you try to get from it. And to fail to do so is both childish and gauche because only philistines think it necessary to reconcile their feelings about a piece of art with their feelings about the people who created it.”(2018). This statement draws from the argument for a separation with reference to its emphasis on an alleged logic. This trait can be interpreted as what makes this stance a “universal truth”. However, Grady counteracts this claim using an overarching perspective and observation of art criticism; “the idea of separating the artist from the art is not a self-evident truth. It is an academic idea that was extremely popular as a tool for analyzing poetry [art] at the beginning of the 20th century, and that has since evolved in several different directions” (2018). Grady is criticising classifying ‘you can separate art from the artist’ as a universal truth by considering how critics have manoeuvred the stance in a way that allows further analysis of art to branch it into a scientific realm, as it eliminates acknowledgement of who created it which can cause tension. This displays an ideology that explores and questions art’s potential essence because it’s negotiating any corruption in an artist’s character in a quest to push the actual art itself to higher boundaries.

Grady elaborates by underlining how critics call for an evaluation of art based on its ability to ‘stand-alone, as “the text had to stand on its own, and if it didn’t, the New Critics argued, that proved it wasn’t really good art” (2018). This highlights ideas of separating art from the artist, such as claiming art is only of quality when one can consume and acclaim it with no reference to who the artist is or what they’ve done prior, as “the best way to engage with any really good piece of art is to treat it as a transcendent work that can stand on its outside of history and speak to anyone from any place and time.” (2018). Essentially, Grady establishes how the mindset of consuming and critiquing art based on its ability to transcend from any indication of its creator and instead exist as its own artistic entity influences the separating art from the artist debate. This is an analytical lens that calls for an emphasis on art and art alone, generating critics and consumers to have a tunnel interpretation of asking what is the art saying. Furthermore, it is prompting that consuming art to conclude that the art’s quality relies on being able to perceive it without the artist’s influence. When tying this to our case studies, one would conclude that the New Critics Grady references would direct film fans to watch The Shining as a horror film and decipher their stance on it based on its ability to generate the appropriate emotional response and its quality in visuals and storytelling. Therefore, Kubrick’s methods and any behind-the-scenes knowledge would have to be absent from consumption and interpretation.

This mindset can be negotiated or made difficult when it relates to ideas of audience identity and stance when watching films and other forms of media. To elaborate, if one watches The Shining as a horror fan, then this would be a simple route to take because, for them, the art is standing separate from its creator as they focus on genre and its effect. However, suppose one watches and interprets The Shining from a Kubrick fan rather than a horror fan. In that case, this mindset is challenging as they are watching for the creator and the creator alone, thus, consistently considering Kubrick and his complicated methods when viewing. As a result, audience identity and what has drawn the spectator to the film significantly challenge the stance New Critics are calling for. Anyone consuming The Shining under the identity of a Kubrick fan would potentially be submitting to Auteur theory, the belief that the director is the head creative force behind the film as a whole who imprints their own identity and vision onto a script, thus, “the film artist is thought to make films in the same way the writer creates books” (Demiray, 2015).

Kubrick’s position as an auteur filmmaker with a distinct style proposes complications with consuming any art outside the artist as the New Critics strive for. His recognisable vision in filmmaking collects a dedicated fanbase who consume his work for him. Therefore, they reflect back to him as a creator when consuming his art. This leads to further stances against separating art from the artist, in that if the director leaves such a heavy imprint on their work that it becomes an extension of their identity, then it becomes challenging to separate them as a person from what they have created. However, whilst “classic auteur theory has commanded much of film scholar debate since the 1960s”(Tredge, 2013) and, thus, has influenced the audience’s perception in associating a film so heavily with its director, it can be negotiated as the set in stone outlook. One can argue against both auteur theory and its impact on the debate when considering the numerous roles that exist in filmmaking other than the director. To elaborate, “feature films are never made by a single person. From the writer to the director to the studio executives, many ideas and hours of hard work go into collaborating on film production. It is important to know that one theory of authorship will not answer the question for all films” (Tredge, 2013), an attitude previously explored by Corley. Expanding from Corley, this can liberate a film from any controversy or lack of morals its director holds because it removes the director as the sole provider, thus, proposing audiences consume a film no matter any errors on the director’s part. Under this attitude, one can recognise the other efforts and creativity that went into creating Rosemary’s Baby or The Shining, such as the score composers who assist in executing the atmosphere or the actors who bring the script to life. Overall, one can use the stance of a film as “a primarily collaborative medium” to identify how it would “seem odd that theorists are constantly searching for the singular artist responsible for authorship (Gerstner and Staiger 5)” (Tredge, 2013), thus, separating art from its artist (in this case the director) becomes inevitable due to the other credits a film has in creation.

In his article On The Possibility Of Separating Art From The Artist in The Stanford Daily, Jacob Kuppermann offers an opinion that issues counteractions to these ideas. He references how this debate is heavily significant and present in entertainment and cultural discussions as “there is perhaps no story repeated more often in the annals of pop culture than that of the brilliant artist who is revealed to be a vile person” (2017), offering the binary opposition of a “brilliant artist” who can offer amazing art to negotiate how they are a “vile person”. He recounts previous and overall dialogue on the matter to solidify his own upcoming opinion, for example, highlighting “the idea that we must not abandon works of art solely because of the misdeeds of their creators is a popular one” which created a decision that the “only thing that should matter when experiencing a work of art is what’s actually going on in the work itself” (2017). This constructs a narrative thread for his readers using a planting of immediate perspectives on such a complicated debate, in turn, creating anticipation for his own take that may agree or disagree, which he soon offers in “I agree that personal guilt is not a useful part of the work of critically assessing artists who have done reprehensible things, but the idea that a work must only be evaluated based on its direct content is trickier”. Here, Kuppermann is communicating the opposition between having emotional responses to art made by a controversial figure and the critical and logical observation needed to come to a conclusion. This opposition in question is stemmed from how emotional reactions prevent critical evaluation of information even though they are cognitive processes resulting in the gathering of information. By deeming emotions of guilt and shame as “not useful”, Kuppermann is critiquing delving into emotions during this discussion and branding the act as an interruption in evaluation. This proposes moving forward into a more logical headspace once one has classified the emotions of guilt towards an art they enjoy upon finding out the artist is problematic.

Furthermore, Kupperman proposes a counteraction to the rejection of auteur theory in finding a solution. He does so by proposing a filmmaker chooses to invest personally in their project as“the artists themselves don’t separate themselves from their work” (2017), an outlook made evidently in Kubrick’s emphasis on himself as an auteur. This makes it difficult to separate the artist from their work because“a critical approach that refuses to consider outside factors is limited and foolish, blinding us from a full consideration of any creative work” (2017). To Kupperman, one cannot eliminate consideration of external factors in creating art, such as Kubrick’s emotionally taxing director methods used to make his film, because it refuses to observe the art fully. Essentially, Kupperman is questioning the rejection of how the art was made in a problematic manner by arguing it means rejecting a large portion of the artistic product itself. He carries his argument on by adding a further emphasis on auteurship and the personal elements of creating art, stating how“in modern pop culture, persona and identity so deeply intermingle with art that the artist themselves often becomes impossible to disentangle from their art fully. Consider the films of Woody Allen. The protagonists of movies like “Crimes and Misdemeanors,” “Annie Hall” and “Manhattan,” in all of their neuroticism and sexual dysfunction, are less characters and more proxies for the director himself, who plays all three” (2017). This serves as a critical element in separating art from the artist debate, calling out how directors can invest a huge amount of themselves into their films and manoeuvre them to be an extension of their own emotions, lifestyles and persona and therefore negotiate the ability to be separated from their art by having their art be them. The extreme emotional range Duvall displayed in The Shining is a direct result of Kubrick’s belief in creating a real-life psychological breakdown to portray a fictitious one. Polanski’s real-life actions sinisterly align with the conflict and oppressive themes represented in Rosemary’s Baby. Their intimate attitudes and perspectives are elements of their filmmaking with regard to narrative, visuals and themes, thus combining themselves and their art.

Kupperman further emphasises cognition and logic when evaluating art made by controversial figures by highlighting the specific processes audiences go through, as “to appreciate one of these films while simultaneously remaining aware” of an artist’s problematic behaviour “is an exercise in cognitive dissonance” (2017). This mirrors Griffins’ exploration of the mental justifications made to enjoy art for art despite the knowledge the creator lacks morals. Yet, Kupperman cites it as dissonance and, thus, the elimination of harmony between art and what the creator did. This displays a more in-depth evaluation of the emotional and psychological aspects involved when it comes to separating the art from the artist, one that locates the processes one inherits to be able to do so as distancing the artist’s act from their work to fully appreciate the work as its own physical entity. To gain some objectivity in his piece, Kupperman goes on to examine why and how one could not separate the two, as “every creative work is inherently the unique product of the person (or persons) who made it” (2017), implying the relationship that comes from someone creating a piece of work may be too powerful to separate. Kupperman makes an example of this in how the “same minds” that create works are the same ones that can “sexually assualt” numerous people, conveying how “the personal elements of their crafts are powered by the same people who have done despicable things” (2017). This “ever-present blurring of the lines between the personal and creative spheres” serves as a compromise to separating art from the artist in Kuppermann’s eyes. The personal acts artists commit cannot be severed from their art because both are products of the same person. Kuppermann progresses this perspective by incorporating a familiar criticism of any attempt to distance the art from the problematic artist, as “the fact of the matter is, in our capitalistic, fame-obsessed culture, being a critically or commercially successful artist gains you a significant amount of influence. This influence, when in the hands of certain unfortunate individuals, can be leveraged to do harm to others” (2017). Here, Kupperman is pinpointing the capital and power artists gain when audiences consume and support their work, presenting it as a gateway to further assaults and immoral acts. This argument dresses the debate in the manner of it not mattering if one can separate art from the artist but instead should one separate the two? This brings the issues of ethics and morality straight to the art’s audiences rather than just the artist themself, prompting those engaging in the debate to reflect on their own morals as implied by their standpoint.

Kupperman situates the stance that you can make the separation against the credentials needed for it to be maintained, the same ones that are associated with issues of ethics and morality. He informs that “separating the art from the artist would be a perfectly sound critical school among many in an ideal world, one where the power dynamics and imbalances fueled by fame and industry influence did not exist and were not vital tools used by sexual predators of all stripes” (2017). This works to identify and call out the idiocies in the entertainment industry that inflict onto the separation debate, ones that Kuppermann is presenting as valid reasons to not separate art from its artist as these are detrimental issues for victims and those vulnerable. To Kupperman, to separate art from the artist means to ignore the harmful abuse of power that problematic artists carry out once audiences have ignored previous acts to enjoy the selected art. This is supported by Kupperman’s direct acknowledgement of the victims who have suffered at the hands of abusive artists. He addresses how “by creating a culture that excuses the misdeeds of the powerful, talented or rich, we make it harder for their victims, from fellow celebrities to anonymous teenagers, to retain their dignity in society” (2017), which demonstrates the emotional turmoil victims go through. This situates the debate further against the emotional aspect, mentioning how society separating art from a problematic artist allows victims to suffer and remain publicly humiliated. This very statement supports the stance of not separating art from the artist. It emphasises how separating the two prioritises a physical art piece over a person who has been exploited and left traumatised, thus, displaying a grounded perspective that calls for emotional well-being to be considered.

Russell Smith wrote his opinions on the debate the same year as Kupperman, therefore, has the same amount of knowledge on relevant events. However, his take differs vastly. He is immediately in illustrating his stance by stating to his readers, “the knowledge of the immorality of the creator does not distract from my enjoyment of his creation; indeed, I am made even more curious to know how beauty is perceived by a violent man” (2017). Therefore, Smith displays confidence in his ability to automatically serve art from the actions of its creator. He does, however, suggest some form of conjoining high-quality art with the disturbing acts of its artists, which is something unfamiliar in academic discourse, implying that one should delve into the bitter irony surrounding the perspective. Smith does echo previous pieces analysed in shifting from his own personal experience with consuming art to an overall cultural experience, done so when analysing any judgment he receives for separating art from the artist. He writes, “and if I do this and am judged immoral for it, is it because it is bad for just me or bad for society at large?” (2017), conveying the potential argument that engaging with art made by problematic people has detrimental effects on our society as a whole. This does make sense to a degree because it alludes to supporting abusive figures who exploit the power consumption of their art provides, something Smith considers in highlighting “the problem of engaging with art by bad people, it is said, is an economic one”(2017). This is expanded on when Smith underlines the overall issues in the entertainment industry and supports abusive figures such as Polanski, as “ it is also argued that the culture of movie-making in Hollywood is pervasively sexist and abusive and that contributing to its economic success as a whole is a subtle approval of its tactics. An essayist in The New York Times tweeted that “the critical acclaim and economic clout of the art facilitate the abuse.” (2017). Smith is directly referencing other conclusive statements on the matter. Such statements are drawn from an overall observation of the dangerous aftermaths of still providing finances for someone like Polanski. This proposal still praising his work, allows his sexual abuse to fester and flourish.

Despite this, Smith remains grounded in his stance that separation is both possible and needed. He supports this stance by opposing the syntax used when it comes to discussing consuming art made by controversial figures, shown in “I want to take issue with the idea of “enjoying” art as well. Yes, one does enjoy it, sometimes, but that’s far from the only reason for art’s existence” (2017), thus, challenging the ways people have been discussing and evaluating the debate by suggesting their view on art and its purpose has been one dimensional and therefore, lacklustre. Smith’s worldview on the matter is given as “to consume art is for me as necessary a means of understanding the culture around me as reading the news is; it is necessary and automatic, almost involuntary” (2017). This grants art as an educator, similar to what Grady’s presentation of the New Critics was underlining. Smith is illustrating how art isn’t just wanted for entertainment purposes and is instead a vital window into societal views during any time of creation. Therefore, it holds intellectual merit alongside enjoyment. Smith goes on to dissect this newfound intellectual aspect of art as a medium, tying it into his reasoning of separating any art from a problematic creator in stating how “If I were to stop delving into unpleasant, embarrassing or possibly immoral art for any reason, I would feel cut off from my own intellect. I would feel stupid” (2017). Here, Smith argues for the separation between art and artist for the alleged sake of intellect that art offers, regardless of its content or tone. This emphasises art’s ability to stand on its own, separate from its creator, in generating cognitive action in the form of education for audiences. Essentially, Smith is asking his readers to consider that, no matter what the creator of artwork has done, the potential education art can offer has to exceed the controversial actions because it can elevate individuals and society.