#Charles Edenshaw

Text

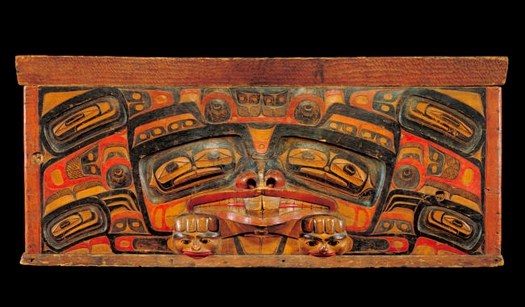

Yaahl hat

Isabel Rorick (Haida) in collaboration with Robin Rorick (Haida)

Woven and painted spruce root. 7.25” x 14.25” x 14.25”

This painted hat is the newest collaboration between mother/son duo Isabel and Robin Rorick. Yaahl means “raven” in Massett Haida dialect, and the design of the hat was directly inspired by a Charles and Isabella Edenshaw painted hat from 1900. The Roricks are direct descendants of the Edenshaws, and carry on the tradition of Haida women weaving spruce root and Haida men painting them once completed. To ready himself to paint on his mother’s exquisite spruce root weavings, Robin sought the advice of fellow Haida artist and family member Robert Davidson, and also visited the collections at the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia to handle and study the historic Edenshaw works.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Somewhere there is, like a bizarro-world @official-kircheis going,

"Great achievements in art:

The ceiling of the cistine chapel

The woodcarving and silver work of Charles Edenshaw

Vermeer's Girl With Pearl Earring

The work of Hieronymus Bosch

Francisco Goya's Saturn Devouring His Son

Great Achievements in STEM:

?????

Seriously name me one Mathematical equation or semiconductor which is as pretty to look at as any of those, I'll wait."

And then like, bizarro-world versions of his opponents going,

"Actually a lot of those artists used mathematics to figure out perspective"

And then he's like,

"Lol, so the only thing they contributed was the ability for other people to make things way prettier than they ever could have made? Sounds like pure cope but okay."

23 notes

·

View notes

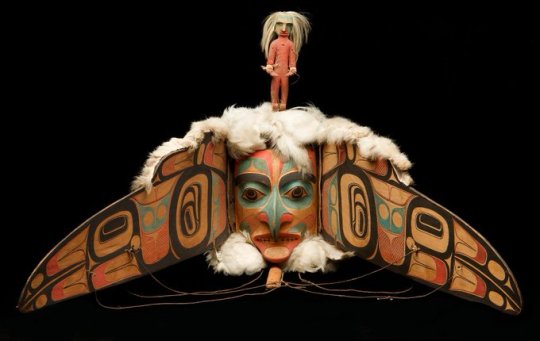

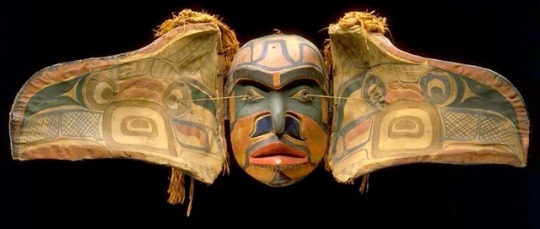

Photo

Charles Edenshaw ~ Transformation mask, Haida Gwaii Pacific Northwest Coast, British Columbia, 1891

287 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles Edenshaw - Haida nation artist and master craftsman - Bear Mother Carving, 1900

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top left: Charles Edenshaw (1839 - 1920) “Dogfish Bracelet”, silver (late 19th century) Photo : Vancouver Art Gallery

Top right: Charles Edenshaw, “Sea Bear Bracelet”, silver (late 19th century) Photo: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery

Bottom: “Charles Edenshaw carving a silver bracelet amidst examples of his argillite model poles and a box. The damage to his left eye from a revolver accident bothered him as he got older but did not affect the exquisite sense of balance and symmetry in his carving. Photographer unknown, circa 1880.” — Canadian Museum of History

Charles Edenshaw (Tahayren) biography: Canadian Museum of History

#charles edenshaw#Tahayren#Haida#master carver#19th century art#jewelry#bracelet#first nations#formline#silver

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An assortment of anthropomorphic transformation masks created by Pacific Northwest Coast Indigenous peoples on the continent of North America.

#Transformation masks#NW Coast Haida#Movable masks#Kwakiutl#Haida#masks#transformation#bear transformation mask#Northwest Coast Indian art#Vancouver Island#British Columbia#Pacific Northwest#Tsa-qwa-supp#Pitt Rivers Museum#American Museum of Natural History#Eagle Mask#Charles Edenshaw#Kwakwaka'wakw artists#Raven Travelling#Wanderer mask#First Nations of British Columbia#Northwest coast of Canada#magictransistor#Late 19th century#magic transistor#Native American art#American art#Ameerica#Americans#Wooden transformation mask

8K notes

·

View notes

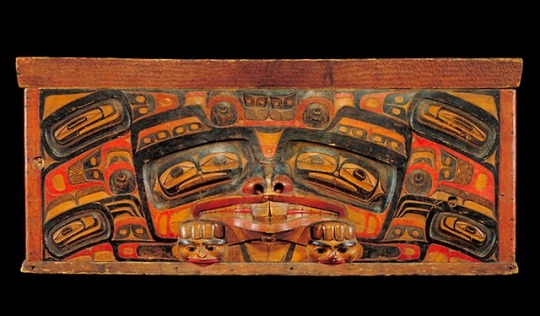

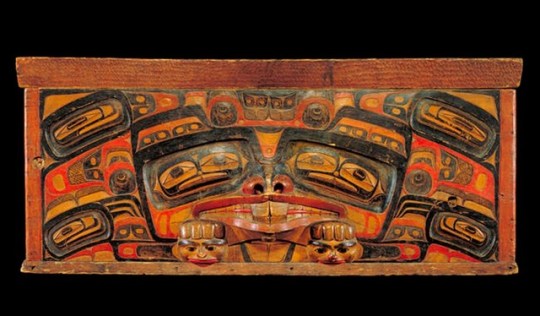

Photo

Bentwood Chest

Charles Edenshaw

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Fungus Man (in the canoe to the left of Raven) has the best facial expressions.” —Colin Dickey, referencing the image on the cover of Entering Time: The Fungus Man Platters of Charles Edenshaw, by Colin Browne, which is described on the Talon Books website in this way:

During the groundbreaking Charles Edenshaw exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 2013, poet Colin Browne found himself returning often to study three large argillite (slate) platters carved by the Haida master in the late 1800s. Produced several years apart, each of the platters presents the same scene: in a Haida canoe, Raven holds his spear at the ready, his bracket-fungus helmsman is wedged into the stern, and below the canoe a figure hovers. Where are they going, and why? And who is the bracket-fungus helmsman? Browne begins by tracing his family’s lives in a small village on Vancouver Island. He explores the Surrealist attraction to the Indigenous arts of the Northwest Coast, the tragic results from colonial incursions and government policies, and the extraordinary achievement of Haida artists during a century of radical change. He encounters a story with a teaching that is as profound and relevant today as it was when Da.a xiigang, Charles Edenshaw, learned it in his youth. And he finds in Da.a xiigang’s art a deeply personal and moving response to the arrival of the modern world.

Colin Browne’s Entering Time: The Fungus Man Platters of Charles Edenshaw is an extended, often poetic, meditation on the three argillite platters created in the late nineteenth century. In this newly published book, Browne ranges through the fields of art history, literature, ethnology, and oral history to discover a parallel history of modernism within one of the world’s most subtle and sophisticated artistic and literary cultures.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Clapper in Form of a Fish with Human Head for Finger Lever, Charles Edenshaw, pre-1864, Brooklyn Museum: Arts of the Americas

Carved wood clapper in the form of a halibut with the face of the fish’s spirit represented on the tail. Condition: good.

Size: 9 3/4 x 2 3/4 in. (24.8 x 7.0 cm)

Medium: Cedar wood, pigment

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/126624

54 notes

·

View notes

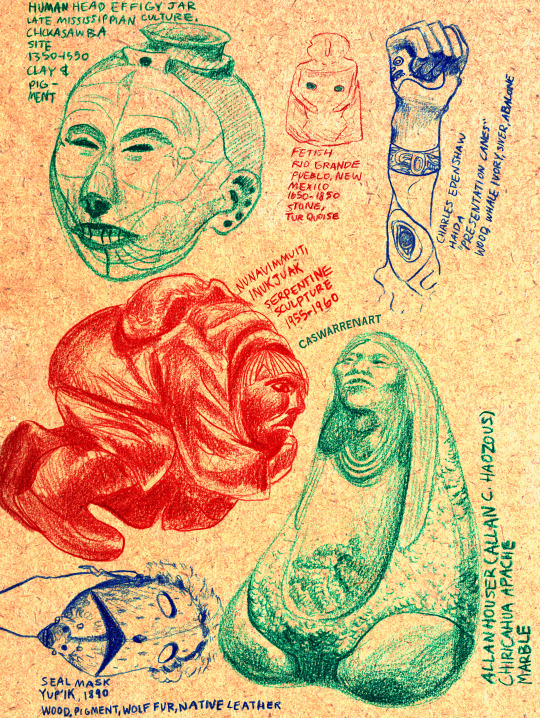

Photo

My studies of the Nelson Atkin’s North American First Nations collection, my favorite part of the museum. You can see and learn more about these pieces here: human figure, Presentation Cane by Charles Edenshaw, serpentine sculpture, seal mask, Untitled Sculpture by Allan Houser, and human head effigy jar (possibly no longer in the collection)

#caswarrenart#casper warren#2017#sketchbook#colored pencil#pencil#sketch#drawing#native american#native america#history#art history#first nations#indigenous#illustration#sculpture#haida#yupik#yup ik#apache#chiricahua#Nunavimmuit#inupiaq#inukjuak#Rio Grande Pueblo#pueblo#Late Mississippian Culture#Chickasawba#nelson atkins

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Totem Pole Model, Charles Edenshaw, ca. 1890, Metropolitan Museum of Art: Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas

Ralph T. Coe Collection, Gift of Ralph T. Coe Foundation for the Arts, 2011

Size: H. 16 1/4 x W. 3 1/4 in. (41.3 x 8.3 cm)

Medium: Argillite

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/319092

6 notes

·

View notes

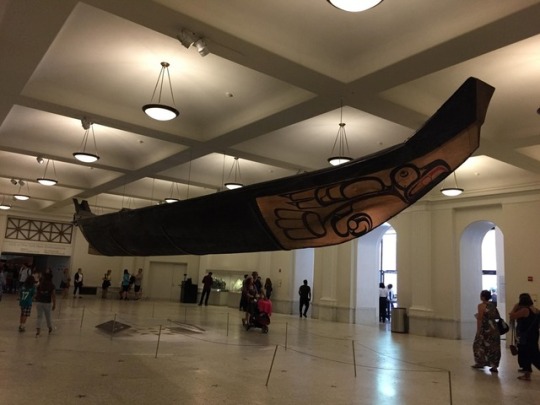

Photo

At 63 feet long, the Great Canoe is completely seaworthy! Well, it was originally. After hanging in a museum gallery for so long, maybe not. Carved in the 1870s from the trunk of a single cedar tree, it has design elements from different Native American peoples of the Northwest Coast, notably Haida and Heiltsuk.

Although it is not known for sure, the beautiful killer whale depicted on either side of the prow of the Great Canoe was most likely painted by Charles Edenshaw (1839-1924), one of the most influential Haida artists of his time, known for his woodcarving, jewelry, and painting. Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History.

#history#art history#native american#native people#indigenous#museum#american museum of natural history

1K notes

·

View notes

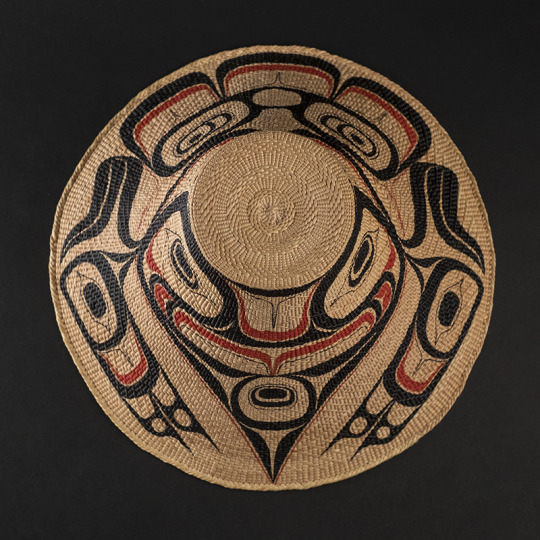

Photo

Lidded Basket. Charles Edenshaw. Isabella Edenshaw. 1885–90 Canada, British Columbia. Haida. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Deeply Carved"

“Deeply Carved”

“While attending his (Bill Reid) grandfather’s funeral in Skidegate in 1954, Reid held and closely examined a pair of bracelets made by Charles Edenshaw that were “really deeply carved,” and he would later say that after that transformative encounter, “the world was not really the same.” the bracelets left an indelible impression that compelled him to refine his standards for the making of Haida…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

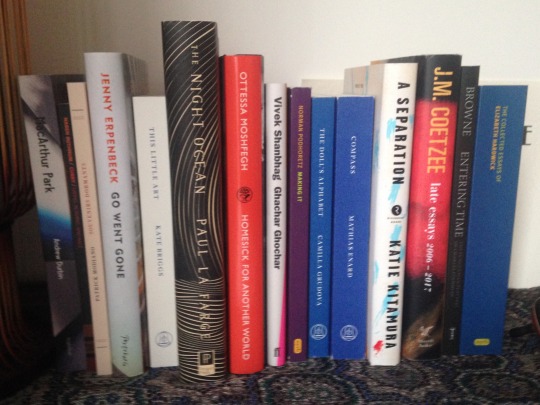

A Year in Reading: My Favourite Books Published in 2017

Mathias Enard, Compass (New Directions/Fitzcarraldo, 2017). Trans. Charlotte Mandell.

The insomniac thoughts and memories of Franz Ritter, an ethnomusicologist who specializes in how western classical music has been influenced by music of the east. Over the course of one night, he reflects on his life and work, particularly as it related to a woman he loved, another orientalist scholar whom he continuously encountered on field work throughout the Middle East. A fascinating meditation on the interpenetration of self and other, as well as a requiem for the places and cultures recently destroyed by civil war and the continued aftereffects of colonialism. Easily my favourite book of the year. I read it in French originally when it appeared in 2015, and Charlotte Mandell’s translation was excellent -- I rarely enjoy a translation of a book I’ve already read as much as I did this one.

Jenny Erpenbeck, Go, Went, Gone (New Directions/Portobello, 2017). Trans. Susan Bernofsky.

A recently retired classics professor becomes more and more involved in the plight and lives of recent migrants to Berlin. He also thinks back on his own life and history as an East German. The way the protagonist's experiences -- the whole swath of his East German historical tapestry -- were wax-printed onto his observations of the refugees made it global in a way that European novels rarely achieve, so often caught up in themselves, and only themselves. With this, Erpenbeck managed to conjure a way into the world that connected the twentieth century history of Europe with something more contemporary: its present, which is no longer only the purchase of Europeans.

Paul La Farge, The Night Ocean (Penguin, 2017).

A man goes missing not long after realizing that he had been conned into believing a manuscript detailing H. P. Lovecraft’s sex life with a younger man was authentic but then continues on a quixotic quest for the truth. I’m not even a Lovecraft fan, but this novel -- with its mise-en-abyme stories within stories within grifts within stories -- was unputdownable. It is as much about reading and fandom as it is about Lovecraft. About the way stories attempt to form our world into something more than a night ocean.

Ottessa Moshfegh, Homesick for Another World (Jonathan Cape, 2017).

A collection of stories by the author of Eileen. Drifters, failures, fuckups. Her prose is such a pleasure to read, its forensic exactitude.

Camilla Gurdova, The Doll’s Alphabet (Coach House/Coffee House/Fitzcarraldo, 2017).

I loved these strange parables. The ways she took her stories and sentences were continually unexpected. This book about transformations, women, and animals is so sui generis that it begs comparisons -- Sheila Heti, Marie Darrieussecq, Angela Carter, Marie de France, David Garnett -- if only to prove that none of them quite hold.

Vivek Shanbhag, Ghachar Gholchar (Faber, 2017). Trans. Srinath Perur.

A man recounting the story of his marriage over one evening after he discovers something unspeakable. The novel -- novella? -- is extremely short. But every piece of the story is exactly where it needs to be. In a way, its form reminds me of the best longer stories by Henry James.

Katie Kitamura, A Separation (Riverhead, 2017).

A woman goes to Greece to look for her estranged husband who has gone missing. Once there, she finds herself with more of a problem than she originally thought. I read this when it was released, and more than many other novels from the beginning of the year, its images have remained. I’ve heard it described as being somewhat like Javier Marias. I don’t think so. It’s doing something quite different. Although the narrator does have a penchant for observation, its style of storytelling is more controlled. Kitamura is also excellent with images, like those of a slightly aloof poet, whose images of a hot and arid Greek landscape have stayed with me.

Patrick Modiano, Souvenirs Dormants (Gallimard, 2017).

Thematically and stylistically, Modiano has nothing to prove, so this novel continues where his previous ones left off. A story about the way people from your past can reappear unexpectedly. It’s his first since winning the Nobel. Modiano is doing what Modiano is good at. That said, I would put it above Pour que tu ne te perds pas dans le quartier, for example. It’s not as good as Dans le cafe de la jeunese perdue or La place d’etoile, but it’s that’s not saying much. It’s still good. It also happens to be partially set a block away from my current apartment...

Naben Ruthnum, Curry: Eating, Reading, Race (Coach House, 2017).

The topic at heart of Curry is language -- how words are used, how they designate, market, and identify. The book attempts to address the ways in which writers of colour, in this case brown writers, relate to the signifiers associated with their so-called culture of origin. Ruthnum manages to address such complicated ideas about race and culture all the while coining a term to indicate a kind of book that white people seem to love seeing brown writers publish: currybooks. Ruthnum addresses the problems head on, considering his own Journey prize-winning story “Cinema Rex,” the first and only time he delved into his Mauritian heritage, as well as providing a literary assessment of South Asian diasporic writing, the pitfalls of an industry that seems to pigeonhole brown writers in a specific genre of literary novel. (Full disclosure: I’ve known Naben since he was three. Throughout the writing of Curry, I kept jokingly pestering him via email to include me in the book because I cook his mom’s dahl recipe weekly.)

J M Coetzee, Late Essays: 2006-2017 (Harvill Secker, 2017).

His three essays on Beckett are more than worth the price of admission alone. Of interest to me also were the essays on German literature -- those on Kleist, Walser, and Goethe. At his best, he is one of my favourite living writers, as both a novelist and critic; at their best, these essays did not disappoint.

Colin Browne, Entering Time: The Fungus Man Platters of Charles Edenshaw (Talon, 2016*).

Poet, filmmaker and critic Colin Browne’s essay Entering Time (about the “Fungus man” platters of nineteenth century Haida artist Charles Edenshaw) attempts wrestle with some of the tensions inherent within Canadian culture: the far too unspoken imbalance between its settler-colonial population with its indigenous one. The essay grapples with the dynamic of a white person engaging with the art of the North West coast without losing focus on its subject: the aesthetic marvels and legacy that are the work of Charles Edenshaw. It then proceeds to offer an incredibly convincing interpretation of these masterworks of Haida art.

*The colophon says 2016, but I don’t think it was available in Canadian bookstores until Jan. 2017.

Kate Briggs, This Little Art (Fitzcarraldo, 2017).

A meditation on Briggs’s translation of Roland Barthes, This Little Art becomes an essay on the art of translation, on the relationship between translators and authors, specifically women translators, as well as being about the late work of Roland Barthes. I remember reading Briggs’s translation of Barthes’s In Preparation of the Novel years ago when it was published, and it was such a pleasure to read this extended essay. Until this point, my favourite book on translation has been Rosemary Waldrop’s A Lavish Absence: Recalling and Rereading Edmund Jabés (Waldrop’s excellent memoir about translating, reading, and knowing the great poet). But I think This Little Art now takes the throne as my favourite book by a translator about the art of translating.

Norman Podhortez, Making It (New York Review of Books Classics, 2017).

I never thought I’d like something by one of the architects of the neocon movement, but so it goes. A friend gave this book to me after we discussed something that I was working on. Said she thought I’d enjoy it, and I did. It is a frank and bitter depiction of the New York intellectual scene that surrounded the Partisan Review. A fascinating document in twentieth century intellectual history. It’s also a compelling memoir in its own right. A must read for anyone interested in that generation of New York critics, but especially if you’re interested (as I am) in Clement Greenberg...

Andrew Durbin, MacCarthur Park (Nightwood, 2017).

A novel about a young writer who is writing a novel about the weather. Or so he says. It also is the novel that we, as readers, are reading. Upstate utopian colonies, artists, gay New York club life, hurricane Sandy, the Tom of Finland Foundation, failed attempts at transcendental meditation, the ebb and flow of romantic relationships, all fit into the story of a young man in New York. It’s a portrait of a place, and it’s also, I think, quite a perceptive meditation on names -- how meaning is projected onto something via its name. In that way, as well as in its form, it’s a very Proustian novel.

Elizabeth Hardwick, The Collected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick (New York Review of Books Classics, 2017)

Although I’m not finished this, I’ve been savouring each essay. All 600 pages worth of them.

Special mention (aka shameless promotion)

Pierre Mac Orlan, Mademoiselle Bambù (Wakefield, 2017). Trans. Chris Clarke.

I can’t properly include this book because (a) it’s not released until December and (more importantly -- full disclosure -- b) I wrote the afterword for it (on the French illustrator Gus Bofa whose illustrations accompany Mac Orlan’s tale). Otherwise I would be calling it one of the great finds of the year. It still is. (But with that caveat of full disclosure.) A tale of early twentieth century espionage. Mac Orlan was once condescendingly referred to as “le Proust des pauvres,” which I think is a compliment in so many unintended ways. A writer who straddles the line between avant-garde modernism and various kinds of genre fiction (in the case of this novel, mystery and espionage), Mac Orlan deserves a far greater readership. Check it out: http://wakefieldpress.com/mac_orlan_bambu.html

0 notes