#Daniel taradash

Text

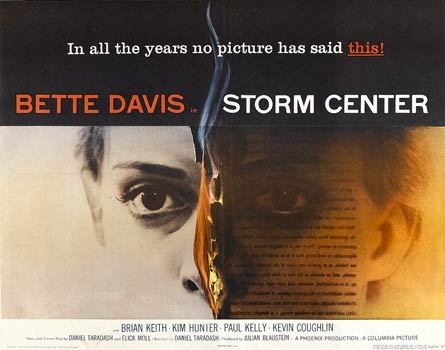

Golden Boy (Rouben Mamoulian, 1939).

#golden boy#golden boy (1939)#rouben mamoulian#william holden#Lewis Meltzer#Daniel Taradash#Sarah Y. Mason#Victor Heerman#Clifford Odets#Karl Freund#Nicholas Musuraca#Otto Meyer#Lionel Banks#Robert Kalloch

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best Donna Reed movies and performances:

1. It's a Wonderful Life - Frank Capra (1946)

2. From Here to Eternity - Fred Zinnemann (1953)

#donna reed#it's a wonderful life#from here to eternity#frank capra#fred zinnemann#1946#1953#1940s#1950s#40s#50s#1940s movies#1950s movies#40s movies#50s movies#Christmas by medium#Daniel taradash#magic realism#From here to eternity novel#Drama#James Jones author#The greatest gift#United States army#Philip van doren stern#burt lancaster#charles dickens#montgomery clift#a christmas carol#frank sinatra#james stewart

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Don’t Bother to Knock (1952)

On social media, there are certain actors from Golden Age Hollywood whose imagery, on occasion, seeps through the Internet’s algorithmic modern biases. Too often, those posts are from individuals who have never seen such actor’s movies. Chief among those actors are James Dean, Marlon Brando, Audrey Hepburn, and Marilyn Monroe. Against the grain, I hold that James Dean’s posthumous legacy has overshadowed three performances I am no fan of and Brando’s airbrushed reputation leaves him overvalued in the popular written histories of American cinema. By contrast, Audrey Hepburn’s standing in modern times feels just about correct (although more people should seek out her films beyond 1953’s Roman Holiday and 1961’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s). For Marilyn Monroe, a recent film like Andrew Dominik’s Blonde (2022) follows decades of works that have exploited her image – oftentimes simplifying her to a tragic sex symbol. Monroe, of the four aforementioned Old Hollywood actors who show up from posts from non-film buffs, is the only one whose talents I consider underrated.

There is no better showcase of her early-career dramatic abilities than in Roy Ward Baker’s film noir Don’t Bother to Knock, released by 20th Century Fox. Up to this point, Monroe had starred in more than a dozen films in supporting roles. In a time when actors and film crewmembers were contracted to a studio, Fox loaned Monroe early in her career to Columbia, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), and most recently to RKO. Fox executive Darryl F. Zanuck was still not entirely sure what to make of her, despite a strong performance in RKO’s Clash by Night (1952). Offering Monroe the lead role in Don’t Bother to Knock, Zanuck gave her the opportunity to prove herself (in addition to ascertaining British director Roy Ward Baker’s skills for his first Hollywood picture). Wary of the risks of pushing an actress to her first lead role as well as working with an unfamiliar director, Zanuck allowed a budget that, by Fox’s standards in the early ‘50s, was a trifle. Yet, because of these limitations, Don’t Bother to Knock is a decent noir and a solid Marilyn Monroe vehicle.

One night in a New York City hotel, airline pilot Jed Towers (Richard Widmark, one of Fox’s brightest stars at this time) approaches his ex-girlfriend Lyn Lesley (Anne Bancroft in her film debut), the hotel club’s singer. Lyn broke up with Jed recently by letter, and explains to her ex that her reasoning is due to his attitude. Jed, flustered, heads back to his room. On the same floor Jed is on but across the air shaft, elevator operator Eddie Forbes (noir mainstay Elisha Cook Jr.) introduces his niece Nell (Marilyn Monroe) to guests Peter (Jim Backus) and Ruth Jones (Lurene Tuttle). Nell will serve as babysitter to the Jones’ daughter, Bunny (Donna Corcoran), while the couple attend a reception downstairs. All is set in motion when Jed first sees Nell across the way.

Also in the cast is Don Beddoe as Mr. Ballew. And Disney fans might recognize Verna Felton – the Elephant Matriarch in Dumbo (1941) and the Fairy Godmother in Cinderella (1950), among others – playing Mr. Ballew’s meddling wife, Emma.

Don’t Bother to Knock’s categorization as a film noir comes from its storyline, rather than its visuals. Bar one scene involving Jed believing someone on the other side of the room to be asleep, the film lacks the shadowy aesthetic one comes to expect from noir. Shot and lit conventionally, Don’t Bother to Knock never quite escapes the fact it is obviously soundstage-bound. The small number of different locations for the film’s various scenes also does not help matters. From a perspective of style, this is a disappointing effort from cinematographer Lucien Ballard, who had ample experience in film noir by this point – see The Lodger (1944) and The House on Telegraph Hill (1951) in this collaboration with Baker.

Yet it is the two central performances that elevate the material. The audience is witnessing Marilyn Monroe before sporting her platinum blonde locks. The natural brunette keeps her natural hair color for this film; not truly transforming into the Marilyn that most casual film audiences know about until Niagara (1953). Unlike the typecast dumb blonde roles that she received later in her career, her role in Don’t Bother to Knock is neurotic, restless, and wide-eyed not in a sexual way. Monroe brings a level of internal strife strewn across her face, a measured gait, and a nervous avoidance of eye contact with Richard Widmark and other actors opposite her. To yours truly, having seen Monroe in so many other roles, it was difficult for me to connect her speaking voice – high-pitched, like a streetwise Snow White living in urban America – to this character’s neuroses. She does not attempt much modification in her delivery or register, whether in this role or others. But given that this is early in her career, this can slide. It is otherwise a solid turn that justifies Zanuck’s supposed gamble on her as a lead actress.

After his debut in Henry Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947) for 20th Century Fox, Richard Widmark became one of the studio’s prize actors. His role as the sneering, misogynistic, and psychopathic Tommy Udo brought instant notoriety, as well as spawning fan clubs in American colleges and universities known for their sexism. Early in his Fox career, he would largely play villains, but cinephiles knowledgeable of classic Hollywood know that Widmark was equally capable in more honorable roles. In Don’t Bother to Knock, his Jed sits somewhere squarely in the middle – deeply unlikeable, abrasive, yet with glimmers of compassion and helpfulness. That Tommy Udo sneer finds its way onto Widmark’s face, if only for a few passing moments, due to the pain of his recent separation from Anne Bancroft’s Lyn. Despite Jed’s less-than-virtuous qualities, the viewer – because of the situation that transpires between him and Nell – will find themselves rooting for that elusive happy ending in a film noir. Widmark’s performance in Don’t Bother to Knock is not as remarkable as that in Kiss of Death or No Way Out (1950), but he complements Monroe’s performance wonderfully.

Adapted from the little-read and slender book Mischief by Charlotte Armstrong, Don’t Bother to Knock received its adapted screenplay treatment from Daniel Taradash (1953’s From Here to Eternity, 1955’s Picnic). The pulpy screenplay takes place over a few evening hours, refusing to show its entire hand until a little more than halfway through. Eventually, discussion and a depiction mental illness – as it was understood in the 1950s – becomes prominent in the film. By today’s standards, the script’s understanding of mental illness is deficient. It is used more as a plot device rather than something to inspire dialogue about how the individual in question is coping or how the mental health professional have utterly failed them. Some might argue this might detract from the narrative at-large (and noir is very much a narrative-driven subgenre), but I contend that noir with a social conscience only adds depth to the noir tradition.

Director Roy Ward Baker and co-star Richard Widmark, initially frustrated with Monroe’s habits – requiring acting coach, Natasha Lytess, to be on set constantly; frequently asking to take breaks between takes; and constant tardiness – changed their minds when viewing the film’s rushes (the raw unedited footage played back for the director and editor after the film’s shoot is completed for the day). Monroe brought a rawness appropriate for her role in Don’t Bother to Knock, and her inexperience contributed to her believability in the role. As Don’t Bother to Knock made its theatrical premiere in July 1952, some of the nation’s leading movie critics only added to Darryl F. Zanuck’s unease about framing Marilyn Monroe as a lead actress. Ignoring the plaudits from the audiences, Baker, Widmark, and less-prominent critics, Zanuck instead fixated on the likes of The New York Times’ Bosley Crowther claiming that, “Monroe is being groomed by Twentieth Century-Fox for razzle-dazzle stardom… if they also expect her to act, they’re going to have to give her a lot of lessons under an able and patient coach.”

These reviews (that Zanuck spent too much time thinking about) from Crowther and his fellow contemporaries drip with condescension, misogyny, and language more appropriate for a gossip column. For Monroe – only in her mid-twenties and whose shyness and insecurity followed her through all of her life – one can only imagine how hurtful these words and Zanuck’s perceptions must have been. The crafting of the culturally dominant image of Monroe – as a voluptuous and ditzy blonde plaything with no interiority – was beginning to take shape. In the final year that any American could reasonably not have known the name of Marilyn Monroe, Don’t Bother to Knock represents the end of her status as a Hollywood afterthought.

My rating: 7/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#Don't Bother to Knock#Roy Ward Baker#Richard Widmark#Marilyn Monroe#Anne Bancroft#Donna Corcoran#Jeanne Cagney#Lurene Tuttle#Elisha Cook Jr.#Jim Backus#Verna Felton#Don Beddoe#Daniel Taradash#Charlotte Armstrong#Lucien Ballard#Darryl F. Zanuck#Lionel Newman#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Picnic (1955)

My rating: 6/10

Gosh, but everybody in this is awfully high strung, aren't they.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Top two vote-getters will move on to the next round. See pinned post for all groups!

#best best adapted screenplay tournament#best adapted screenplay#oscars#academy awards#the departed#william monahan#felix chong#alan mak#from here to eternity#daniel taradash#james jones#the imitation game#graham moore#andrew hodges#moonlight#barry jenkins#tarell alvin mccraney#the bad and the beautiful#charles schnee#george bradshaw#pygmalion#george bernard shaw#ian dalrymple#Cecil Arthur Lewis#w.p. lipscomb#polls#bracket tournament#poll#brackets

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Kim Novak in Bell, Book and Candle (Richard Quine, 1958)

Cast: James Stewart, Kim Novak, Jack Lemmon, Ernie Kovacs, Hermione Gingold, Elsa Lanchester, Janice Rule. Screenplay: Daniel Taradash, based on a play by John Van Druten. Cinematography: James Wong Howe. Art direction: Cary Odell. Film editing: Charles Nelson, Music: George Duning.

Kim Novak was not an actress of wide range, but in the right role and with a good supporting cast, she made a strong, sexy impact, as she does in Picnic (Joshua Logan, 1955), Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958), and Bell, Book and Candle, in which she is paired again with her Vertigo co-star, James Stewart, and surrounded by a supporting cast full of scene-stealers: Jack Lemmon, Elsa Lanchester, Hermione Gingold, and Ernie Kovacs. The movie is nothing special: a fantasy romantic comedy with Novak as Gillian Holroyd, a witch who runs a primitive-art gallery on the ground floor of the apartment house where Shep Henderson (Stewart), a book publisher, lives. She puts a spell on him; he leaves his fiancée, Merle Kittridge (Janice Rule), for her but breaks it off when he discovers that he's been hexed. And so on. The movie was made after Vertigo, and Novak and Stewart were re-teamed because of a deal Columbia had made when it loaned out Novak to Paramount for the Hitchcock film. It's not the most plausible of pairings: Novak was 25 to Stewart's 50 -- an age difference that was less problematic in the plot of Vertigo, with its theme of erotic obsession. After Bell, Book and Candle, Stewart chose never to play another romantic lead, but the film gives him some good moments to show off his exemplary skill at physical comedy, as in the scene in which he's forced to scarf down a nauseating witches' brew concocted by Mrs. De Passe (Gingold). The screenplay by Daniel Taradash opens up a one-set Broadway comedy by John Van Druten that had starred Rex Harrison and Lili Palmer. It was nominated for Oscars for art direction and for Jean Louis's costumes, but lost in both categories to Gigi (Vincente Minnelli). The cinematography is by James Wong Howe.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Strangers When We Meet (Richard Quine, 1960)

Pocas veces ha contado la filmografía de un cineasta, de forma tan implícita como evidente, una historia en principio feliz pero de tan triste final como la de Richard Quine entre 1954 y 1962, es decir, desde que conoce y dirige por primera vez a la starlet de la Columbia Pictures Kim Novak, en Pushover (La casa nº 322), trágico thriller en blanco y negro inspirado en Double Indemnity (Perdición, 1944), de Billy Wilder, y con uno de sus principales intérpretes, Fred MacMurray, hasta que, ocho años más tarde, se despide de ella —en la pantalla—, de nuevo en blanco y negro tras un interludio de amor en color, pero esta vez en el marco algo amargo de una comedia negra policíaca y británica nada feliz y no del todo lograda, The Notorious Landlady (La misteriosa dama de negro), con Jack Lemmon, Fred Astaire y varias viejecitas tan estrafalarias como siniestras.

En medio hay dos verdaderas declaraciones de amor sobre celuloide y a todo color, la primera esperanzada, la comedia de misterio y fantasía, pero típicamente neoyorquina y realista al mismo tiempo, titulada Bell, Book and Candle (Me enamoré de una bruja, 1958), en la que Quine se anticipa unos meses a Vértigo (De entre los muertos), de Hitchcock, al emparejar a Kim Novak con el larguirucho James Stewart; la segunda, muy desesperanzada, es un pesimista melodrama de amargo final, coprotagonizado por Kirk Douglas, Strangers When We Meet (Un extraño en mi vida, 1960), muy minnelliano de paleta cromática y planteamiento, pero probablemente muy autobiográfico (sustitúyase al arquitecto que trabaja por encargo por el director bajo contrato con la Columbia).

No es esta crónica de un amor muy larga ni detallada, pues, sino elíptica y zigzagueante, como suelen serlo las mejores películas de este sensible y poco apreciado director —menos llamativo que su amigo Blake Edwards, menos brillante que Stanley Donen, que era el veterano del trío, aunque Quine fuera el mayor—, pero desde el primer plano de Kim Novak en Pushover, aunque nada sepamos de la relación que hubo entre ella y Quine, intuimos que no es que la actriz sea de una notable —y más bien pasiva— fotogenia, ni posea esa enigmática capacidad de fascinar a la cámara que tienen algunas mujeres, y de las que otras, incluso mejores intérpretes y hasta mucho más guapas, carecen, a veces por completo, sino que el director estaba ya prendado de ella. Hay algo en la manera de iluminarla y encuadrarla, de seguirla y hasta acariciarla con la cámara, que va más allá de cualquier hábil estrategia dramática de Quine para hacer que los espectadores comprendamos el hechizo que siente por ella el policía encarnado por MacMurray. A medida que avanza la historia, y se comprende que Kim es una de esas mujeres débiles que, casi sin proponérselo, resultan fatales para los hombres que se enamoran de ellas y están dispuestos a dejarse engañar por su aparente inocencia, queda de manifiesto que no se trata de eso, que el director, arrebatado, se está dejando llevar por su pasión, y que filma a la actriz más, más de cerca y durante más tiempo que el exigido por la economía narrativa de la película.

Cuatro años después, la comedia de John Van Druten adaptada por Daniel Taradash hace de Kim Novak una bruja actual e inocente, que fascina a Stewart y que, por amor hacia un hombre corriente y bastante mayor que ella, renuncia a sus poderes y se convierte en una simple humana, librándole así de su ominosa e insoportable prometida. Pocas veces una película ha mimado tanto a su protagonista, descubriéndole encantos recónditos, no evidentes a primera vista, revelando como timidez y miedo a hacer daño su aparente frialdad, insinuando que bajo su falta de expresividad habitual se esconden un fuerte sentido del humor y una obstinada fuerza de voluntad, complaciéndose en contemplar y proclamar su belleza, comparando —en un plano memorable— sus ojos con los de su gato Paywacket. A Quine no le basta ya con admirar en privado a su amada, necesita compartir su hallazgo, divulgar las excelencias de Kim Novak, sentirse ratificado en su buen gusto y, por tanto, envidiado por los restantes espectadores.

Me enamoré de una bruja es, sin duda, su película más extática y feliz, la más armoniosa, la única que da la sensación de que ese amor deducible de la puesta en escena era correspondido por el objeto de sus entusiastas atenciones.

Un extraño en mi vida es otra canción, mucho más conmovedora y melancólica, una de las películas que más me emocionan cada vez que la veo, y van unas veinticinco. Nunca estuvo Kim Novak tan realmente humana, tan física y al mismo tiempo tan frágil, ni tan guapa, ni siquiera en Vértigo, donde aparecía siempre excesivamente alienada y distante, salvo quizá en la escena de la bata, en casa de Scottie (James Stewart), después de sacarla de la bahía de San Francisco. Hay pasión y despecho, violencia y sufrimiento en cada plano. Y, para colmo, es evidente que Quine no puede renunciar a Kim, que se le va la mirada detrás de ella, que trata esta vez no ya de darla a conocer, sino de indagar en sus razones, de comprender qué ha pasado, por qué ha fracasado en la empresa que más le importaba.

Es una película verdaderamente romántica, febril y angustiada, triste y patética, sin mucho humor —y el que queda está teñido de amargura, como el personaje del escritor insatisfecho y alcohólico que encarna espléndidamente Ernie Kovacs— y derrotada, pero apasionada, enamorada todavía. Y no sólo, eso es evidente, por la muy desconsolada y desconsoladora historia que relata manifiestamente, en su anchísima pantalla de Cinemascope, sino, sobre todo, por la que cabe seguir leyendo entre líneas, entre plano y plano, en las miradas temerosas o culpables y evasivas de la actriz a la cámara o, mejor, un poco a un lado y más allá del objetivo, hacia el director, y más aún que en el rostro de Kirk Douglas en la imagen que Quine nos transmite de Kim Novak a través de cada encuadre, cada leve panorámica de acercamiento, o esa rendida e impúdica dolly vertical que recorre su cuerpo a una cierta distancia, como si fuese ya inalcanzable pero siguiese siendo deseable y querido: es la apoteosis de Kim Novak, casi el último beso, ya desesperado y suicida, del director.

Publicado en el nº 2 de Nickel Odeon (primavera de 1996)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Castle Keep (1969)

"Europe is dying."

"No, Beckman, she's dead. That's why we're here. Don't you read the newspapers?"

#castle keep#american cinema#1969#Sydney Pollack#William Eastlake#Daniel Taradash#David Rayfiel#burt lancaster#patrick o'neal#jean pierre aumont#peter falk#astrid heeren#scott wilson#tony bill#al freeman jr.#james patterson#bruce dern#michael conrad#caterina boratto#olga bisera#michel legrand#oohoo reading the letterboxd reviews on this one and i can only say: opinions are Mixed. for my views see my painfully pretentious lb#review. but suffice it to say this film grabbed me by the chest and didn't let go for 100 plus minutes. Utterly beautiful and brutally ugly#all at once; more than most this film welcomes differing interpretations. for eg. i think you can rightfully make the argument that this is#a piously anti war film which shakes with rage at the pointlessness and loss and sheer waste of war; i think you could equally argue that#this is a film which declares that war is a sometime awful necessity. i think this film successfully argues both points whilst never once#suggesting they can coexist. It's a contradictory idea but it's a contradictory film#Falk is right to leave his unit and set up as a baker in an apocalyptic warzone; he would be right to remain just as he's right to leave#and to return to his men. war is madness and madness is war and everything's a goddamn circle baby#im getting pretentious again. this might be the best film I've seen in 2021. you might well hate it. such is life.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

A 'Picnic' with William Holden and Kim Novak on Criterion Channel

A ‘Picnic’ with William Holden and Kim Novak on Criterion Channel

The repressed desires and suppressed dreams of small town citizens bubble out of their confines in the late summer days of Picnic (1955).

William Holden is the hunky drifter who rides the rails into a small Midwest town with dreams of landing a “respectable” job with his rich college buddy (Cliff Robertson). Kim Novak is the small town beauty queen who is engaged to Robertson but falls for the…

View On WordPress

#1955#Arthur O&039;Connell#Betty Field#Blu-ray#Cliff Robertson#Criterion Channel#Daniel Taradash#DVD#Joshua Logan#Kim Novak#Nick Adams#Picnic#Rosalind Russell#Susan Strasberg#VOD#William Holden#William Inge

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

CASTLE KEEP: An Analysis

Few movies resonate as deeply with me as Castle Keep.

It is truly sui generis.

It’s a deceptively simple story:

In the waning days of WWII, eight walking wounded American soldiers occupy a castle in Belgium, a token sign of force as the war rages past them.

The castle belongs to a noble family who owned it for generations and stocked it with a vast collection of priceless rare and irreplaceable classical art.

The current count wants to keep his castle and his collection intact, but he also wants a son to carry on the family name and tradition.

He is, unfortunately, impotent.

And even more unfortunately, the castle is located in the Ardennes forest, on the road to Bastogne…

Now, those raw elements are more than enough to fuel a perfectly good run of the mill WWII movie, with plenty of bang-bang-shoot-em-up and some obligatory musings on the meaning of it all.

And I’m sure that’s the way they pitched Castle Keep.

But director Sydney Pollack and screenwriters Daniel Taradash and David Rayfiel (adapting the eponymous novel by William Eastlake) delivered something far more…well…phantasmagorical is as apt a way of describing it as any.

Because despite being solid grounded in a real time and a real place and a real event, Castle Keep moves out of the realm of mere history and into a much more magical place.

Not so much fact, as fable.

And as fable, it gets closer to the Truth.

. . .

Before we analyze the movie, let’s set the contextual stage.

First off, understand the impact WWII movies still had on audiences of the 1960s and early 70s.

For those who lived through the war years, it occurred scarcely more than 20 years earlier, a period that seems like forever to teenagers and young adults but flies past in the blink of an eye when one reaches middle age and beyond.

Not only were WWII movies popular, they were relatively easy to make. A lot of countries still used operational Allied and German equipment up through the 1960s (Spain’s air force stood in for the Luftwaffe in 1969’s The Battle Of Britain), and for low budget black and white films or pre-living color TV, ample archival and stock footage padded things out.

Most importantly, WWII was a shared experience insofar as younger audiences grew up hearing from their parents what it was like, and as a result there was some degree of relatability between the Greatest Generation and their children, the Boomers.

But the times, they were a’changin’ as Dylan sang, and the rise of the counter-culture in the 1960s and the civil rights, feminist, and ant-Vietnam War movements (and boy howdy, is that a hot of history crammed into one sentence but you’re just gonna hafta roll with me on this one, folks; we’ll examine that era in greater detail at some point in the future but not today, not today…) led to younger audiences looking at WWII with fresh eyes and to older film makers re-evaluating their own experiences.

So to focus on WWII films of the time, understand their were 3 main threads running through the era:

The epic re-enactment typified by The Longest Day (1961), The Battle Of The Bulge (1965), Patton (1970), and ending with A Bridge Too Far in 1977

The cynical revisionism of The Dirty Dozen (1967), Where Eagles Dare (1968), and Kelly’s Heroes (1970)*

The absurdity of How I Won The War (1967) and Catch-22 (1970)

Castle Keep brushes past all those sub-genres, though it comes closest to absurdity.

. . .

While released in 1969, Castle Keep started development as early as 1966 (the novel saw print in 1965). Burt Lancaster, attached early on as the star, requested Sydney Pollack as director.

Pollack, an established TV director, started making a name for himself in the mid-1960s with films like The Slender Thread and This Property Is Condemned; he and Lancaster worked together on The Scalphunters prior to Castle Keep.

While his first three films were well received, Pollack’s career really took off with his fifth movie, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? and after that it was a string of unbroken successes including Jeremiah Johnson, The Way We Were, The Three Days Of The Condor, Tootsie, Out Of Africa, and many, many more.

In fact, the only apparent dud in the barrel is Castle Keep, his fourth movie.

Castle Keep arrived at an…uh…interesting juncture in American (and worldwide) cinema history.

The old studio system that served Hollywood so well unraveled at the seams, the old way of doing business and making movies just didn’t seem to work anymore.

Conversely, the new style wasn’t winning that many fans, either.

For every big hit like Easy Rider there were dozens of films like Candy and Puzzle Of A Downfall Child and Play It As It Lays and Alex In Wonderland.

As I commented at the time, it seemed as if everybody in Hollywood had forgotten how to make movies.

It was a period rife with experimentation, but the thing about experiments is that they don’t always work. While there were some astonishingly good films in this era, by and large it’s difficult for modern audiences to fully appreciate what the experimental films of the era were trying to do -- and in no small part because when they succeeded, the experiments became part of the cinematic language, but when they failed…

Castle Keep is not a perfect film. As much as I love it, I need to acknowledge its flaws.

The Red Queen brothel sequences feel extraneous, not really worked into the film. Women are often treated like eye candy in male dominated war films, but this is exceptionally so. Brothels and prostitution certainly existed during WWII, servicing both sides and all comers, but the Red Queen’s ladies undercut points the film makes elsewhere.

Their participation in the penultimate battle shifts the film -- however briefly -- from the absurd to the ridiculous, and apparently negative audience testing resulted in a shot being inserted showing them alive and well and cheering despite a German tank blasting their establishment just a few moments earlier.

Likewise, an action sequence in the middle of the film where a German airplane is shot down also seems like studio pressure to add a little action to the first two-thirds of the movie.

Apparently unable to obtain a Luftwaffe fighter of the era, Pollack and the producers opted for an observation aircraft, then outfitted it with forward firing machine guns, something such aircraft never carried.

Once the airplane spotted the American soldiers at the castle, it would have flown away to avoid being shot down, not return again and again in futile strafing runs while they returned fire.

It’s action for the sake of action, and like the Red Queen scenes actually undercuts other points the film makes.

. . .

But when the film works, ah, it works gloriously…

Pollack used a style common in films of the late 1960s and early 70s: Jump cuts from one time and place to another, with no optical transition or establishing shot to signal the jump to the audience.

Star Wars brought the old school style of film making back in a big way, and ya know what? Old school works; it was lessons learned the hard way and by long experience.

Still, Pollack’s jump cuts add to Castle Keep’s dreamy, almost hallucinogenic ambiance, and that in turn reinforces the sense of fable that permeates the film.

For as historically accurate as Castle Keep is re the Battle of the Bulge, as noted above it is not operating in naturalism but rather the theater of myth and magic.

Pollack prefigures this early on with a dreamy slow motion sequence of cloaked riders galloping through the dead trees of the Ardennes forest, jumping a fence directly in front of the jeep carrying Major Falconer (Burt Lancaster) and his walking wounded squad.

It’s a sequence similar to one in Roger Vadim’s "Metzengerstein" segment of 1968’s Spirits Of The Dead, and while it’s unlikely Pollack found direct inspiration from Vadim, clearly both drew from the same mythic well.

The sequence serves as an introduction to the count (Jean-Pierre Aumont) and Therese his wife (? Niece? Sister? Nobody in the movie seems 100% sure what their relationship is, but she’s played by Astrid Heeren) and the fabulous Castle Maldorais.

The castle is fabulous in more ways than one. While the exterior was a free standing full scale outdoor set and some large interior sets were built, many of the most magnificent scenes were filmed in other real locations to show off genuine works of art found in other European castles.

This adds to the film’s somewhat disjointed feel, but that disjointed feel contributes to the dream-like quality of the story.

. . .

As mentioned, Maldorais is crammed to the gills with priceless art, and the count doesn’t care who prevails so long as the art is unmolested.

The same can’t be said about Therese, however, and as the film’s narrator and aspiring author, Private Allistair Piersall Benjamin (Al Freeman Jr.), notes “We occupied the castle. No one knows when the major occupied the countess.”

The count, as noted, is impotent. To keep Castle Maldorais intact for future generations, he needs an heir and is not fussy about how he obtains one. Therese’s function is to produce such an heir, and if the count isn’t particular about which side wins, neither is he particular about which side produces the next generation.

Despite being the narrator and (spoiler!) sole American survivor at the end of the film, Pvt. Benjamin is not the focal character of the film, nor -- surprise-surprise -- is Lancaster’s Maj. Falconer.

Falconer is evocative of Colonel Richard Cantwell in Ernest Hemingway’s Across The River And Into The Trees, in particular regarding his love affair with a woman many years his junior.

Falconer wears a patch over his right eye, the only visible sign of wounding among the GIs occupying the castle.

Several military movie buffs think they found a continuity error in Castle Keep insofar as Maj. Falconer first appears in standard issue officer fatigues of the era, but towards the end and particularly in the climactic battle wears an airborne officer’s combat uniform.

This isn’t an error, I think, but a clue as to Falconer’s personal history.

An airborne (i.e., paratrooper) officer who lost an eye is unfit for combat, and if well enough to serve would be assigned garrison duty, not a front line command.

Falconer figures out very early in Castle Keep the strategic importance of Castle Maldorais re the impending German attack and very consciously makes a decision to stand and fight rather than fall back to the relative safety of Bastogne.

Donning his old airborne uniform makes perfect sense under such circumstances.

If the count is impotent invisibly, Falconer is visibly impotent -- in both senses of the word -- and sees his chance to make one last heroic stand against the oncoming Nazi army as a surer way of restoring his symbolically lost manhood than in impregnating Therese.**

. . .

Before examining our focal character, a few words on the supporting cast.

Peter Falk is Sgt. Rossi, a baker. Sgt. Rossi’s exact wounding is never made clear, but it appears he suffers from some form of shell shock (as they called PTSD at the time).

He hears things, in particular a scream that only he hears three times during the movie.

The first time is after an opening montage of beautiful works of art being destroyed in a series of explosions. When a bird-like gargoyle is blow apart, a screech is heard on the soundtrack, and we abruptly jump cut to Maj. Falconer and Sgt. Rossi and the rest of the squad on their way to Castle Maldorais.

For a movie as profoundly philosophical as Castle Keep (more on that in a bit), Sgt. Rossi is the only actual philosopher in the group. His philosophy is of an earthy bent, and filtered through his own PTSD, but he’s clearly thinking.

Rossi briefly deserts the squad to take up with the local baker’s wife (Olga Bisera, identified only as Bisera in the credits). This is not adultery or cuckoldry; Rossi sees her bakery, knocks, and identifies himself as a baker.

“And I am a baker’s wife,” she says.

“Where’s the baker?”

“Gone.”

And with that Rossi moves in, fulfilling all the duties required of a baker (including, however briefly, standing in as a father figure for her son).

The baker’s wife is the only female character who displays any real personal agentry in the film, Therese and the Red Queen and her ladies are there simply to do the bidding of whichever male is present.

This is a problem with most male-oriented war films, and especially so for late 60s / early 70s cinema of any kind; for all the idealistic talk of equality and self-realization, female characters tended to be treated more cavalierly in films of that era than in previous generations. Olga Bisera’s character appears noteworthy only in comparison to the other female characters in the movie.

Pvt. Benjamin, our narrator and aspiring author, is African-American. There is virtually no reference made to his race in the film, certainly not as much as the references to a Native American character’s ethnicity.

Today this would be seen as an example of color blind casting; back in 1969 it was a pretty visually explicit point.

Again, it serves the mythic feel of the movie. At that time, African-American enlisted personnel would not be serving in an integrated unit.

While Castle Keep never brings the topic up, the film -- and Pvt. Benjamin’s narration -- indicates these eight men are bottom of the barrel scrapings, sent where they can do the least amount of damage, and otherwise forgotten by the powers that be.

With that reading, Benjamin’s presence is easy to understand. As the apparently third most educated member of the unit (Falconer and our focal character are the other two), he probably would not have been a smooth fit in any unit he’d been assigned to.

Whatever got him yanked out of his old company and placed under Maj. Falconer’s command probably was as much a relief to his superiors as it was to him.

Scott Wilson is Corporal Clearboy, a cowboy with a hatred of Army jeeps and an unholy love for Volkswagens.

Volkswagens actually appeared in Germany before the start of WWII but once Hitler came out swinging those factories were converted to military production. Nonetheless, the basic Beetle was around during the war, and commandeered and used by many Allied soldiers who found one.

Clearboy’s Volkswagen provides one of the funniest bits in the movie, and one that plays on the mythical / surreal / magic realism of the film. Clearboy’s obsession is oddly touching.

Tony Bill’s Lieutenant Amberjack tips us early on to the kind of cinematic experience we’re in for. Under the opening credits, Amberjack is asked if he ever studied for the ministry; Amberjack says he did.

“Then why aren’t you a chaplain?”

-- and Amberjack bursts out laughing.

Amberjack does not go with the others to the Red Queen -- “That’s for enlisted men” -- and while he enjoys playing the count’s organ, by that I mean he literally sits down at the keyboard and plays music.

But as we’ll see, Castle Keep is not the sort of movie to shy away from sly hints. Amberjack’s specific “wound” is never discussed, so it’s open to speculation as to why he’s assigned to Maj. Falconer’s squad.

(Siderbar: Following a successful acting career, Bill went on to produce and direct several motion pictures, sharing a Best Picture Oscar for The Sting with Michael and Julia Phillips.)

Elk, the token Native American character in every WWII squad movie, is played by James Patterson. Elk doesn’t get much to do in the film, though Patterson was an award winning Broadway actor. Tragically, he died of cancer a few years after making Castle Keep.

Another character with little to do is Michael Conrad’s Sergeant DeVaca. Most audiences today remember him for his role in Hill Street Blues.

Astrid Heeren (Therese) gets a typically thankless role for films of this type in that era. She possessed a beautiful face that’s so symmetrical it gives off an unearthly, almost frightening vibe. A fashion model in the 1960s, she appeared in only four movies -- this one, The Thomas Crown Affair, and two sleaze fests -- before quitting the business.

As noted above, no one is ever quite sure what her exact relationship to the count is. Towards the end it’s speculated she’s his sister and his wife, but since the count is impotent, does that really constitute incest?

Whatever she is, it’s clear the count considers her nothing more than an oven in which to bake a new heir, and in a very real sense she possesses less freedom and personal agentry than the ladies of the Red Queen.

At least she survives at the end of the film, pregnant with Falconer’s child, led to safety by Pvt. Benjamin.

Finally, Bruce Dern as Lieutenant Billy Byron Bix, a wigged out walking wounded who is not a member of Falconer’s squad.

Bix leads his own rag tag group of GIs, equally addled soldiers who proclaim their newly found evangelical fervor renders them conscientious objectors. They wander about, singing hymns and scrounging for survival, until the penultimate battle of the film.

Falconer, trying to recruit more defenders from the retreating American forces, dragoons Bix and his followers into singing a hymn in the hopes of luring some of the shell shocked GIs back to the keep.

Bix agrees -- and is almost immediately killed by a shell, not only thwarting Falconer’s plan but also raising the question of whether this was divine punishment for abandoning his pacifist ways, fate decreeing Falconer and his squad must stand alone, or pure random chance.

Dern, as always, is a delight to watch, and he and Falk get a funny scene where they argue about singing hymns at night.

. . .

So who is our focal character?

Patrick O’Neil was one of those journeymen actors who never get the big breakout role that makes them a star, but worked regularly and well.

He worked on Broadway, guest starred on TV a lot, starred in a couple of minor films (including the delightful sci-fi / spy comedy Matchless), but spent most of his movie career supporting other stars.

Castle Keep is his finest performance.

He’s supposed to be supporting Lancaster in Castle Keep, but dang, he’s the heart and soul of the film.

O’Neil plays Captain Lionel Beckman, Falconer’s second in command, a professor of art and literature whose name is well known enough to be recognized by the count.

Besides Falconer, Beckman is the only character explicitly acknowledged as having been wounded; this is revealed when Falconer mentions Beckman won the Bronze Star (the second highest award for bravery) and the Purple Heart.

Beckman is enthralled by Castle Maldorais; he and the count strike up a respectful if not friendly relationship.

He sees and appreciates the cultural significance of Castle Maldorais’ artistic treasures and futilely tries to share his love of same with the enlisted men.

He also understands how little Falconer can do at the castle to slow the German advance, and makes the entirely reasonable suggestion that perhaps it would be best for the squad and the castle to retreat and let the treasures remain intact.

Lancaster reportedly wanted to make Castle Keep a comment on the Vietnam War, but the reality is there’s no adequate comparison.

History shows the Nazis were a brutal, aggressive, racist force determined to conquer all they could and destroy the rest.

Beckman is not a fool for wanting to spare the castle and its art, and that’s why he’s vital as the film’s focal character.

He sees and feels for us the horror at what appears to be the senseless waste about to befall the men and the castle. His voice is necessary to express there are ideals worth fighting for, and there are times when not fighting is the best strategy.

But Maj. Falconer is shown as a good officer. While he maintains an aloof attitude of command, he’s interested in and concerned about the men under him, he’s willing to be lenient if circumstances permit, and he keeps them openly and honestly informed at all times of the situation facing them.

He figures out the meaning of the flares seen early in the film, anticipates what the German line of attack will be, but most importantly realizes more will die and more destruction will occur if the Nazis aren’t resisted.

He and Beckman’s difference of opinion is not simplistic good vs evil, brute vs beauty, but a deeper, and ultimately more ineffable one over applying value in our lives.

Falconer and Beckman represent two entirely different yet equally valid and equally human points of view of when and how we decide to act on those values.

Falconer by himself cannot tell the story of Castle Keep, he needs the sounding board of Beckman, and only Beckman can bridge the gap between those opposing values for the audience.

. . .

Before we go further, a brief compare & contrast on an earlier Burt Lancaster film, The Train (1964).

It touches on a theme similar to Castle Keep: As Allied armies advance on Paris, the Germans plan to move a vast collection of priceless art by rail from France to Germany. Lancaster, a member of a French resistance cell, doesn’t see the military value of stopping the train, but when other members of his cell decide to do so in order to save French culture, he reluctantly joins their efforts.

The film ends with the train stopped, the French hostages massacred, the art abandoned and strewn about by the fleeing Germans. Lancaster confronts and shoots the German officer responsible then leaves, dismayed and disgusted by the waste of human life over an abstract love of beauty.

The French resistance fighters who died trying to stop the train did so of their own fully informed consent; they knew the risks, we willing to take them, ad faced the consequences.

The civilian hostages massacred at the end had no knowledge, much less any say in the reason why their lives were risked. Lancaster, in successfully derailing the train to prevent it leaving France, also signs their death warrants when the vengeful Nazis turn on their victims.

The Train proved a critical success and did well at the box office, yet while it raises a lot of interesting points and issues, it ultimately isn’t as deep or as humane as Castle Keep.

The Train ends with a bitter sense of futility.

Castle Keep ends with a bittersweet sense of sacrifice.

. . .

All of which brings us to the screenplay of Castle Keep, written by Daniel Taradash and David Rayfiel off the novel by William Eastlake.

I read Eastlake’s book decades ago and remember it to be a good story.

The screenplay kept the basic plot but built wonderfully off the complexity of the novel, reinterpreting it for the screen.

It’s one of the few cinematic adaptations of a good literary work that actually improves on the original.

Taradash was a classic old school Hollywood screenwriter with a string of bona fide hits and classics to his credit including From Here To Eternity (1952), Picnic (1955), and Hawaii (1966). He also scripted the interesting misfire Morituri (1965), about an Allied double-agent attempting to sabotage a German freighter trying to get vital supplies back to the fatherland.

I suspect Taradash was the studio’s first choice for adapting the book, and as his credits show, an eminently suitable one.

But when Pollack came on as the director, he also brought along David Rayfiel, a frequent collaborator with him on other films.

Rayfiel’s career as a screenwriter was shorter than Tardash’s but more intense, vacillating between quality films and well crafted potboilers. Rayfiel and Pollack doubtlessly shaped the final form of the screenplay, and despite what appears to he studio interference, turned in a truly memorable piece of work.

As I said, Castle Keep is truly sui generis, but there are other films and screenplays that carry some of the same flavor.

The Stunt Man (1980; directed by Richard Rush, screenplay by Rush and Lawrence B. Marcus off the novel by Paul Brodeur) bears certain similarities in tone and approach to Castle Keep. It represents an evolution of the cinematic style originally found in Pollack’s film, now refined and polished to fit mainstream expectations.

True, it has the advantage of a story that hinges on sudden / swift / disorienting changes, but it still managed to pull those effects off more smoothly than the films of the late 1960s did.

As I said, some experiments work…

Castle Keep’s screenplay works more like Plato’s dialogs than a traditional film script.

Almost every line in it is a philosophical statement or question of some sort, and underlying everything in the film is each character’s quest for at least some kind of understanding if not actual meaning in life.

As noted, Sgt. Rossi is the most philosophical of these characters, though his philosophy is of a far earthier, more pragmatic variety than that of the count, Falconer, or Beckman.

All the major characters have some sort of philosophical bent, even if they’re not self-aware enough to recognize it in themselves.

The dialog is elliptical, less interested in baldly stating something that in getting the audience to tease out its own meanings.

Pollack directs the film in a way that forces the audience to fill in many blanks.

Early in the movie, Falconer and the count find themselves being stalked by a German patrol. They take refuge in a gazebo, duck as the Germans fire the first few shots --

-- then we abruptly jump to the aftermath of the firefight, with Falconer and the count standing over the bodies of four dead Germans.

Falconer, seeing they’re all enlisted men, realizes they wouldn’t come this far behind enemy lines without an officer.

There can be only one destination for the officer, one goal he seeks…

Pollack then visually cuts away from Falconer and the count to Therese in the castle, but keeps the two men’s dialog going as a voice over.

In the voice over, we heard Falconer stalk and kill the German officer as he approaches the castle…

…and without ever explicitly stating it, the audience comes to realize the count and Therese are not allies of the Americans, that they are playing only for their own side, and that their values are alien to those of both the Allies and the Germans.

The count is using Therese -- with or without her consent -- to produce an offspring for him, and if the Germans can’t do the job, let the Americans have a go at it…

This theme provides an undercurrent for Beckman’s interactions with the count. Beckman would like to believe the count’s desire to keep the war away from Castle Maldorais is just a desire to preserve the art and beauty in it, but the count’s motives are purely selfish.

He doesn’t desire to share his treasures with the world but keep them for his own private enjoyment.

The works of art are as good as gone once they pass through Castle Maldorais’ gate.

Later, at the start of the climactic battle for the castle, the count is seen guiding German troops into a secret tunnel that leads under the moat to the castle itself.

Falconer, having anticipated this, blows up the tunnel with the Germans in it. Through Falconer’s binoculars, we see the Germans shoot the count in the distance, his body collapsing soundlessly into the snow.

A conventional war film would show his death in satisfying close up, but Pollack puts him distantly removed from the Americans he sought to betray, and even the Germans he inadvertently betrayed.

It shows him going down, alone, in a cold and sterile and soundless environment, his greed for beauty scant comfort for his last breaths.

The film portrays the Germans as mostly faceless, seen only in death or at a distance, rushing and firing at the camera.

The one exception is a brief scene where Lt. Amberjack and Sgt. Rossi patrol the forest around the castle.

Amberjack, playing a flute he acquired at the castle, catches the attention of a German -- a former music student -- hiding in the nearby bushes.

The unseen German compliments Amberjack on his playing, but says if he’ll toss him the flute he’ll fix it so it plays better.

And the German is true to the word. Unseen in the bushes, he smooths out some of the holes on the flute and tosses it back to Amberjack.

Amberjack thanks him --

-- and Sgt. Rossi shoots him.

“Why did you kill him?”

Amberjack demands.

“It’s what we do for a living,”

says Rossi, ever the philosopher.

. . .

Castle Keep isn’t a film for everyone.

It offers no pat answers, no firm convictions, no unassailable truths.

It’s open to a wide variety of interpretations, and the audiences that saw it first in 1969 approached it from a far different worldview than we see it today.

It isn’t for everyone, but for the ones it is for, it will be a rich meal, not a popcorn snack.

Currently available on Amazon Prime.

© Buzz Dixon

* I’d include M*A*S*H (1970) in this group even thought (a) it’s set in the Korean War and (b) it’s really about Vietnam. Except for the helicopters, however, M*A*S*H uses the same uniforms / weapons / vehicles as WWII films; for today’s audiences there’s no discernable difference from a WWII-era film. It was a toss-up between putting this in the cynical revisionism or absurdity class, but in the end M*A*S*H is just too self-aware, too smirking to fit among the latter.

** Falconer’s relationship with Therese and (indirectly) the count and the castle also harkens back to a 1965 Charlton Heston film, The War Lord, arguably the finest medieval siege warfare movie ever made. Like Falconer, Heston’s Norman knight must defend a strategic Flemish keep against a Viking chieftain attacking to rescue his young son held hostage by the Normans; complicating matters is Heston’s knight taking undue advantage of his droit du seigneur over a local bride which leads to the locals -- whom the Normans are supposed to be protecting from the Vikings -- helping their former raiders. Life gets messy when you don’t keep your chain mail zipped.

#Castle Keep#Sydney Pollack#Burt Lancaster#war#World War II#movies#movie stars#philosophy#morality#ethics#art#beauty#Daniel Taradash#David Rayfiel#screenwriting#writing

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Desiree (1954)

Desiree by #HenryKoster starring #JeanSimmons and #MarlonBrando, "tasteful-to-the-point-of-tasteless melodrama overwhelms you with aesthetic beauty", Now reviewed on MyOldAddiction.com

HENRY KOSTER

Bil’s rating (out of 5): BB.5

USA, 1954. Twentieth Century Fox. Screenplay by Daniel Taradash, based on the book by Annemarie Selinko. Cinematography by Milton R. Krasner. Produced by Julian Blaustein. Music by Alex North. Production Design by Leland Fuller, Lyle R. Wheeler. Costume Design by Rene Hubert, Charles Le Maire. Film Editing by William Reynolds.

Films…

View On WordPress

#Academy Award 1954#Alan Napier#Alex North#Annemarie Selinko#Cameron Mitchell#Cathleen Nesbitt#Charles Le Maire#Charlotte Austin#Daniel Taradash#Elizabeth Sellars#Evelyn Varden#Henry Koster#Isobel Elsom#Jean Simmons#John Hoyt#Julian Blaustein#Leland Fuller#Lyle R. Wheeler#Marlon Brando#Merle Oberon#Michael Rennie#Milton R. Krasner#Rene Hubert#Twentieth Century Fox#William Reynolds

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Photo

Rancho Notorious

#rancho notorious#random richards#poetry#poem#poets on tumblr#haiku poem#haiku poetry#haiku#daily haiku#haiku on tumblr#marlene Dietrich#fritz lang#arthur kennedy#mel ferrer#Gloria Henry#william frawley#jack elam#george reeves#Daniel taradash#Silvia Richards#western

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mel Ferrer and Marlene Dietrich in Rancho Notorious (Fritz Lang, 1952)

Cast: Arthur Kennedy, Marlene Dietrich, Mel Ferrer, Gloria Henry, William Frawley, Lisa Ferraday, Jack Elam, George Reeves, Frank Ferguson, Francis McDonald, Dan Seymour, Lloyd Gough. Screenplay: Daniel Taradash, based on a story by Silvia Richards. Cinematography: Hal Mohr. Music: Emil Newman.

Arthur Kennedy was one of those reliably good Hollywood actors who never made it to the first rank of stardom though he received five Oscar nominations during his 50-year career on screen. He gives what is perhaps the most convincing performance in Fritz Lang's Rancho Notorious as Vern Haskell, the Wyoming cowboy who obsessively tracks down the man who raped and murdered his fiancée. But convincing acting perhaps isn't to the point when you're up against Marlene Dietrich, one of those larger-than-life movie stars who can upend a scene just by tossing back her shoulders, unleashing her familiar hooded gaze, and letting a famous leg slip from the slit in her skirt. The part of Vern Haskell needs a Gary Cooper or John Wayne just for balance. Nor does Mel Ferrer, his reliable blandness offset by frosted highlights in his hair, fare particularly well as Frenchy Fairmont, the current lover of Dietrich's equally absurdly named Altar Keane. But Lang keeps Rancho Notorious from steering too far into the direction of camp, offsetting its Western clichés with some well-staged action scenes and a steady pace that briskly ties up the plot in just under 90 minutes. Unfortunately, Rancho Notorious, which was originally titled Chuck-a-Luck, was tricked out with a narrative ballad accompaniment, "The Legend of Chuck-a-Luck" by Ken Darby, with the unsingable refrain, "Hate, murder, and revenge," that pops up every time you think you can keep a straight face. Still, the film is as watchable as it is incredible.

0 notes

Text

50 years ago tonight April 10th 1972 - Charlie Chaplin received and Honorary Academy Award - it brought him back to America after a 20 year exile.

The inscription read:

‘To Charles Chaplin, for the incalculable effect he has had in making motion pictures the art-form of this century’. Chaplin has become more than a name. It is a word in the vocabulary of films, and anyone who has ever seen a movie is in his debt.” - Daniel Taradash, President of the Academy (1970-1973).

These were the only words Charlie Chaplin could speak, the overwhelming reception he received brought tears to his eyes,…he got a 12 minute standing ovations, accolades and bravos.

“Oh, thank you so much. This is an emotional moment for me, and words seem so futile, so feeble. I can only say that… thank you for the honor of inviting me here, and, oh, you’re wonderful, sweet people. Thank you.”

10 notes

·

View notes