#Italian campaign

Text

"Finito Benito, Next Hirohito" B-25J of 12th Bomb Group. Italy, 1944

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon Bonaparte leading the charge at the Bridge of Arcole (details) by Horace Vernet

#napoléon#napoleon#bonaparte#arcole#battle of arcole#art#horace vernet#napoleon bonaparte#napoléon bonaparte#pont d'arcole#arcola#italy#france#french#italian campaign#history#napoleonic#french revolutionary wars#europe#european#northern italy

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nashorn 121, 131 et 231 du 525e Bataillon de chasseurs de chars lourds (Schwere Panzerjäger-Abteilung 525) – Bataille d'Anzio (Opération Shingle) – Campagne d'Italie – Anzio – Italie – 1944

#WWII#campagne d'italie#italian campaign#bataille d'Anzio#battle of Anzio#opération shingle#operation shingle#armée allemande#german army#heer#525e Bataillon de chasseurs de chars lourds#Schwere Panzerjäger-Abteilung 525#char#tanks#chasseur de chars lourd#heavy tank destroyer#nashorn#anzio#italie#italy#1944

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christmas dinner for Canadian soldiers while fighting in Italy - 1943

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

"USS Savannah (CL-42) afire immediately after she was hit by a German guided bomb during the Salerno Operation, on September 11, 1943. Smoke is pouring from the bomb's impact hole atop the ship's number three 6/47 gun turret."

NHHC: SC 243636

#USS Savannah (CL-42)#USS Savannah#Brooklyn Class#Light Cruiser#Cruiser#Warship#Ship#Allied invasion of Italy#Italian campaign#Salerno Operation#September#1943#World War II#World War 2#WWII#WW2#WWII History#History#United States Navy#U.S. Navy#US Navy#USN#Navy#my post

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Description of Napoleon:

« L'offensive est déterminée pour l'Italie; le commandant en chef de cette partie n'est pas encore connu : on a parlé de Beurnonville, puis d'un Corse terroriste, nommé Bonaparte, le bras droit de Barras et commandant de la force armée dans Paris et environs. » — « Un général qui n'a pas trente ans et nulle expérience de la guerre. . . » « Un petit bamboche à cheveux éparpillés, bàtard de Mandrin. »

Quotes from the letters of Mallet du Pan to the court of Vienna, 17 March, 14 May, 11 August 1796.

Approximate translation:

“The offensive is determined for Italy; the commander-in-chief of this part is not yet known: we have spoken of Beurnonville, then of a Corsican terrorist, named Bonaparte, Barras’ right-hand man and commander of the armed forces in Paris and the surrounding area.” — “A general who is not thirty years old and has no experience of war. . .” “A little child* with scattered hair, bastard of Mandrin.”

——-

*I’m not really sure what bamboche means. Some translations say child. I think it might be an archaic term that is no longer used? Idk

Mandrin is apparently like the French Robin Hood who lived during the 18th century.

An interesting thing about the writer, Mallet du Pan, is that the expression “the Revolution devours its children” is attributed to him.

Source: L'Europe et la Révolution française, V. 5, by Albert Sorel. Page 57.

#description of Napoleon#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#bonaparte#Mallet du Pan#Albert Sorel#Sorel#la révolution française#napoleonic era#napoleonic#first french empire#french revolution#directory#french empire#france#italian campaign#first Italian campaign#history#frev#L'Europe et la Révolution française#quotes#quote

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Édouard Detaille (1848-1912): General Bonaparte during the First Italian campaign

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bonaparte interrogates a fat Austrian prisoner. Direct translation! by Louis Bombled

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

06 June 2023

Wars of the Worlds

Canberra

06 June 2023

Note: The Author apologises for the lack of photography in this one. He will ensure that there are more in the next post, under pain of Field Punishment No. 3 (Being Made to Feel Really Bad about The Whole Thing.)

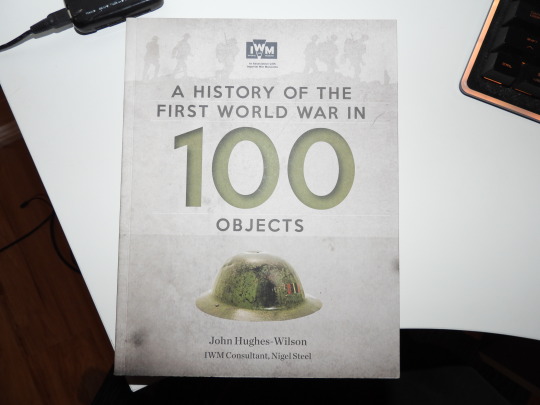

It’s nearly midnight, and I’m sitting in my room occupying that peculiar state where one is too tired to do much of substance, but too alert to sleep. I’d been reading the first volume of John C. McManus’ excellent series on the US Army in the Pacific War, but I’ve put that on hold - partially because I think it deserves more attention than I can give it before I travel, and partially because reading about Douglas MacArthur gives me a headache. I was scanning my books, seeing if there might be something I might read a chapter of section of, and my eyes fell on this.

This is the Imperial War Museum’s History of the First World War in 100 Objects by John Hughes-Wilson. I think it caught my eye because I’ll be there in two weeks. The book’s divided into six parts, so I thought I’d rifle through it and pick an object from each part that stood out particularly to me when I looked at the contents. It’s probably a strange way to do a book review, but to be fair I’m not aiming to review this. This, I think, is a bit more of a philosophical enterprise.

Part 1 is called Imperialism, Nationalism and the Road to War, and it’s fairly short, but it has some fairly choice artefacts. There’s George V’s crown, there’s a map of the European alliances, and there’s even the bloodstained tunic of Archduke Franz Ferdinand - but my eyes were drawn to a pen. This is on page 16, and it’s specifically ‘the pen that signed the Ulster Covenant.’ ‘This pen,’ the book tells us, ‘was used by Colonel Fred Crawford at the signing - reputedly in blood - of the Ulster Covenant, one of the totemic occasions in modern Irish history.’

The book highlights the pen (which forensic analysis has told us, disappointingly, was probably not dipped in blood) as an example of societal tension in both Britain and Ireland in the years leading up to the First World War. The chapter describes, for instance, industrial unrest being put down by troops in South Wales and Liverpool, the Suffragette movement, taxation issues created by welfare reform and the Anglo-German naval arms race, and principally the issue of Irish Home Rule. This brings us neatly back to the Ulster Covenant. It may surprise you, considering the hideous violence that overtook Ireland following the war, that Britain faced not a Catholic uprising in 1914, but a Protestant one. Unionists were alarmed at the Liberal government’s Home Rule Bill, which provided for a separate Irish parliament, and the prospect for the enfranchisement of the Catholic majority that it entailed. On Ulster Day (28 September) 1912, 80,000 Ulster Protestants gathered in Belfast to sign the Covenant, with Carson of course being the first to do so.

By March 1914, things had gotten, frankly, weird. The British Army faced the possibility of being sent in to crush the Ulster Volunteer Force, who were technically preparing to commit insurrection against the government so that they could remain attached to the government, ostensibly in support of an Irish Catholic majority, many of whom were anti-British republicans. To make things even more complicated, Anglo-Irish officers and Ulster sympathisers were overrepresented as officers in the British Army - Brigadier-General Hubert Gough (once again, remember that name) reported that the vast majority of his officers would refuse orders to enforce Home Rule. It was a mess from which it seemed Britain could not extract itself - and then Franz Ferdinand was shot, and the matter became moot as the First World War began.

So why the pen? I think there’s this idea that the First World War is the genesis of pretty much everything that happened afterwards. Yet here we can see the seeds of what would follow the war in Ireland being sown months and even years before the first shots were fired. The First World War didn’t create the Irish Civil War, or the Troubles, or anything like that. More broadly, it stands against the idea of a peaceful, golden Edwardian age that apparently existed before the war, or that there was a long uninterrupted peace between Waterloo and Sarajevo.

I’ll try to keep the other five a bit shorter.

Part 2 is The Shock of the New and there’s plenty of choices here, covering the course of the war through 1914. I was tempted to pick Admiral Souchon’s medals for their Gallipoli connection (I must remember to write a little about Souchon and Goeben before I get there) but my eyes were really caught by ‘the Imperial Eagle in Africa’ on page 88. This is a mosaic of the Imperial German eagle taken from Lome, the capital of German Togoland, by the British. In the late nineteenth century, Germany had joined the ‘Scramble for Africa,’ which had divided the continent between the various European powers. Like every other imperial power, their arrival caused great suffering to the people of their new colonies, most infamously the genocides they carried out against the Herero and Namaqua in Namibia. These Africans, so mistreated by their so-called superiors, were marched into battle when war broke out between Germany and Britain. Both sides used Africans as porters to carry supplies and as fighting troops - the Germans called them ‘askari.’ The East African Campaign, the longest of the African campaigns, cost 10,000 ‘British’ (mostly African), 2,000 ‘Germans’ (mostly African) and perhaps a hundred thousand civilians.

Naturally the vast majority of the historical attention on the African war goes to Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, the German commander in East Africa, who, in internet terminology, is often called a ‘badass.’ To be fair, he did apparently tell Adolf Hitler to go fuck himself (though he was still a bit of a nasty authoritarian himself.) Yet it does seem a bit unjust that the great ‘hero’ of this war was a white German man, and not one of the thousands and thousands of anonymous black dead.

The third part is Theatres of War, which roughly seems to cover 1915. I was drawn to an Italian trench helmet on page 112. Italy entered the war in May 1915, and primarily fought the Austro-Hungarians over the Alps. If there was anywhere on Earth more miserable than the Western Front, the Alpine Front might have been it. Here, men fought for mountaintops, caves and valleys, fighting not only the enemy but the elements. The eleven - eleven! - battles for the Isonzo River read like a parody of the supposed incompetence of leadership in the First World War. Luigi Cardorna - a general who combined pig-headed refusal to accept that constant assaults on the Isonzo were achieving nothing with a brutal, even cruel disciplinarian streak - often tops lists of the worst generals of the war.

(To give you an idea of what I mean by a disciplinarian streak, the man brought back the Roman ‘decimation,’ executing every tenth man in units that ‘weren’t performing well.’)

It’s the unit that this helmet belonged to that really caught my attention. An almost mediaeval affair, it was issued, often along with metal armour, to troops advancing ahead of the main assault force, tasked with cutting barbed wire. They called them Compagnie della morte - the Company of Death.

(As an aside, they tried to replicate this sort of thing in the video game Battlefield 1. It’s, uh… it’s not very realistic.)

Part 4, Mud and Blood, roughly covers 1916-17. The first was Private William Short’s Brodie Helmet, but I’d already done a helmet. The second was a Simplex locomotive. The third, which I went with, was a recovered life buoy from the battlecruiser HMS Indefatigable, lost at the Battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916. I picked this because it’s an example of the war on the sea.

The battlecruiser was the brainchild of Admiral John ‘Jacky’ Fisher, the First Lord of the Admiralty in the 1900s, and the concept was sound. A battlecruiser is not a battleship. Battleships are meant to slug it out, and have the armour to match that purpose. Battlecruisers have battleship guns, but they don’t have battleship armour. The idea is that they can ‘outrun what they can’t outfight, and outfight what they can’t outrun’ - basically, they take on smaller ships and raid commerce.

The battlecruiser idea is not a bad idea, but it ceases to work if their commanders forget they’re not actually in a battleship and engage in a full-scale battle. This is what happened to the British battlecruisers at Jutland. Admiral David Beatty, commanding the Battlecruiser Fleet, engaged his German equivalents in the so-called ‘Run to the South.’ Indefatigable was hit within the first twenty minutes of the engagement by the German battlecruiser Von Der Tann, and was blown in half by an ammunition explosion. Three of her 1,019 crew survived. Shortly thereafter, the Queen Mary exploded, and Beatty’s own flagship Lion nearly met the same fate. Later in the day, the very unfortunately named Invincible also exploded.

To be fair to Beatty, these losses weren’t just because of the weaker battlecruiser armour - the battlecruiser squadrons had taken to leaving the blast doors to the ammunition stowage open to facilitate faster reloading - this meant that when the stowage went up, there was nothing to stop the force of the explosion. To be less fair to Beatty, these unsafe ammunition practices were being implemented under his watch, and he promptly followed the German battlecruisers - who were in fact withdrawing in the direction of their own battleships - right into the main German fleet, and promptly had to race very quickly back north again.

Part 5, From Near-Defeat to Victory, covers 1918. I chose to look at a ‘wreath for Saladin.’ This was sent by Kaiser Wilhelm II to Damascus in the Ottoman Empire in 1898, to be laid on the tomb of the great Islamic warrior Saladin, who fought against the Third Crusade. On the 1st of October 1918, the Allies entered Damascus. The 10th Light Horse got there first, but the official entry was performed by Sherif Feisal’s Arabs - and alongside them, one T. E. Lawrence, today better known as Lawrence of Arabia.

The history of the Arabs after 1918 was one of betrayal and disappointment. They had assisted the British in hopes of ejecting the Ottomans and creating a new, unified Arab state. Instead, under the terms of the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement, Arabia was to be split between French and British mandates. Feisal was made king of Iraq as a consolation, but the seeds of conflict that continue to affect the Middle East were sown here. It’s controversial how much Lawrence knew about this and how much he told to Feisel, though it does seem to me that he supported Feisel’s ambitions for an Arabic state. Ultimately, it was an example of how, for many peoples, the deposal of an old master simply cleared the way for a new one - Ottomans for Englishmen, Tsars for Bolsheviks, and in parts of the southwest Pacific, Germans for Australians.

This has taken a lot longer than I thought it would, but we’re up to the last part, A New European Landscape. I’ve picked Augustus Agar’s boat on page 410. Lieutenant Augustus Agar, Royal Navy, used this torpedo boat to sneak into a Bolshevik flotilla off Finland and sink the cruiser Oleg. I’ll be as a blunt as I can; I chose this because it demonstrates that the First World War did not neatly end on the 11th of November 1918. Conflict was continuing across Eastern Europe, the Balkans, Turkey, the Caucasus, Siberia and China - there’s probably places I’m forgetting. The fact of the matter is that ‘peace’ was really only for the west. The war didn’t ‘end’ so much as it eventually petered out.

Well, that’s about it. I’ve very much moved into the ‘tired enough to sleep’ zone, so I’ll leave that there. Sorry it’s a bit wordy, but I thought it may be of interest. And of course, if you want to look at this book yourself and see the objects I didn’t share, this all came front A History of the First World War in 100 Objects, by John Hughes-Wilson.

A quick acknowledgement to Drachinifel, whose videos on Jutland I used to reorientate myself to the battle. They can be found here and here.

#first world war#ireland#british army#africa#togoland#east african campaign#italian campaign#battle of jutland#palestine campaign#russian civil war

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japanese American troops from the 552nd Field Artillery Battalion nap during combat in Italy, 1943

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

World War II Survivor

View On WordPress

#Christian inspirational#faith#Fascism#History#inspirational story#Italian campaign#Naples Italy#Survivor#War story#World War II#World War II survivor

1 note

·

View note

Text

A B-24 Liberator B Mk VI of No 37 Squadron RAF after being hit by a pair of 1000lb bombs dropped by another B-24 during a mission over Italy, 1945. Remarkably there were no serious injuries to the crew.

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon Bonaparte reviewing the Army of Italy in Nice on 27 March 1796 by Jacques Onfroy de Bréville

#napoleon bonaparte#napoléon bonaparte#armée d'italie#italian campaign#jacques onfroy de bréville#job#art#french revolutionary wars#france#french#nice#italy#history#europe#european#napoleon#napoléon#napoleonic#army#italian campaigns#soldiers#troops#inspection#general#command#bonaparte

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soldats américains sur un chasseur de chars Marder III détruit par les troupes françaises – Bataille de Monte Cassino – Campagne d'Italie – Esperia – Italie – 17 mai 1944

#WWII#campagne d'Italie#italian campaign#bataille de monte cassino#battle of monte cassino#la ligne Gustave#winter line#char#tanks#chasseur de chars#tank destroyer#marder III#esperia#italie#italy#17/05/1944#05/1944#1944

49 notes

·

View notes

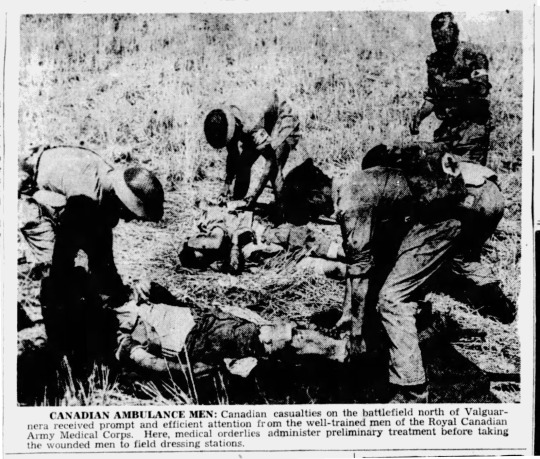

Text

"CANADIAN AMBULANCE MEN: Canadian casualties on the battlefield north of Valguarnera received prompt and efficient attention from the well-trained men of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps. Here, medical orderlies administer preliminary treatment before taking the wounded men to field dressing stations."

- from the Regina Leader-Post. August 17, 1943. Page 16.

#valguarnera#royal canadian army medical corps#medical orderlies#medical corps#italian campaign#world war ii#canadian military#battlefield casualties

0 notes

Text

1944 – Battle of Monte Cassino ends

Conclusion after seven days of the fourth battle as German paratroopers evacuate Monte Cassino.

#May.18.1944#Battle of Monte Cassino#German paratroopers#12th Podolian Uhlan Regiment#Italian Campaign#World War II#history today

0 notes