#Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Text

Cassini: Eight new propeller-like features within Saturn's A ring in what may be the propeller "hot zone" (August 20, 2005)

#cassini huygens#cassini#2005#2000s#krakenmare#astronomy#solar system#astrophotography#outer space#nasa jpl#jet propulsion laboratory#nasa#thank you nasa#space#saturn#saturn rings

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is Ethan Peck visiting JPL to take a look at the Europa Clipper, a spacecraft that will be launched in October towards the Jovian moon in hopes of exploring that strange new world!

Just look at how happy and nerdy he looks at JPL. Props to whoever invited him, because it's only logical to invite Mr. Spock to JPL. And props to Ethan for supporting science and exploration! I love this man 🖖🥹

#ethan peck#mr. spock#star trek#strange new worlds#Europa Clipper#JPL#Jet Propulsion Laboratory#NASA#space#the final frontier#europa#Jupiter#planets#solar system#space exploration#science#physics#astronomy#astrophysics#rocket science#spacecraft#satellite

163 notes

·

View notes

Text

NASA’s Echo 1 communications satellite - 1960.

#nasa#nasa photos#satellites#communication satellites#echo 1#technology#vintage tech#vintage technology#space#space exploration#project echo#space balloons#bell telephone laboratories#jet propulsion laboratory#mylar

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jupiter's moons, Europa and Io, as seen by the Cassini spacecraft rotating the gas giant in this time-lapse video.

#space#outer space#jupiter#video#videos#planets#cassini#europa#io#moons of jupiter#jupiter's moons#nature#nasa#nasa jpl#Jet Propulsion Laboratory#kevin m. gill#twitter

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

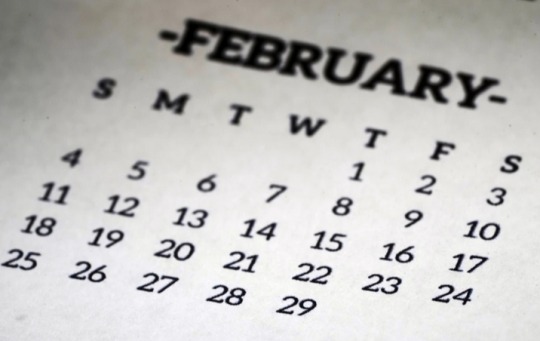

NEW YORK (AP) — Leap year. It’s a delight for the calendar and math nerds among us.

So how did it all begin and why?

Have a look at some of the numbers, history and lore behind the (not quite) every four year phenom that adds a 29th day to February.

BY THE NUMBERS

The math is mind-boggling in a layperson sort of way and down to fractions of days and minutes.

There’s even a leap second occasionally, but there’s no hullabaloo when that happens.

The thing to know is that leap year exists, in large part, to keep the months in sync with annual events, including equinoxes and solstices, according to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology.

It’s a correction to counter the fact that Earth’s orbit isn’t precisely 365 days a year.

The trip takes about six hours longer than that, NASA says.

Contrary to what some might believe, however, not every four years is a leaper.

Adding a leap day every four years would make the calendar longer by more than 44 minutes, according to the National Air & Space Museum.

Later, on a calendar yet to come (we’ll get to it), it was decreed that years divisible by 100 not follow the four-year leap day rule unless they are also divisible by 400, the JPL notes.

In the past 500 years, there was no leap day in 1700, 1800 and 1900, but 2000 had one.

In the next 500 years, if the practice is followed, there will be no leap day in 2100, 2200, 2300 and 2500.

The next leap years are 2028, 2032, and 2036.

WHAT WOULD HAPPEN WITHOUT A LEAP DAY?

Eventually, nothing good in terms of when major events fall, when farmers plant and how seasons align with the sun and the moon.

“Without the leap years, after a few hundred years we will have summer in November,” said Younas Khan, a physics instructor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“Christmas will be in summer. There will be no snow. There will be no feeling of Christmas.”

WHO CAME UP WITH LEAP YEAR?

The short answer: It evolved.

Ancient civilizations used the cosmos to plan their lives, and there are calendars dating back to the Bronze Age.

They were based on either the phases of the moon or the sun, as various calendars are today. Usually they were “lunisolar,” using both.

Now hop on over to the Roman Empire and Julius Caesar.

He was dealing with major seasonal drift on calendars used in his neck of the woods. They dealt badly with drift by adding months.

He was also navigating a vast array of calendars starting in a vast array of ways in the vast Roman Empire.

He introduced his Julian calendar in 46 BCE.

It was purely solar and counted a year at 365.25 days, so once every four years an extra day was added.

Before that, the Romans counted a year at 355 days, at least for a time.

But still, under Julius, there was drift. There were too many leap years.

"The solar year isn’t precisely 365.25 days. It’s 365.242 days," said Nick Eakes, an astronomy educator at the Morehead Planetarium and Science Center at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

Thomas Palaima, a classics professor at the University of Texas at Austin, said adding periods of time to a year to reflect variations in the lunar and solar cycles was done by the ancients.

The Athenian calendar, he said, was used in the fourth, fifth and sixth centuries with 12 lunar months.

That didn’t work for seasonal religious rites. The drift problem led to “intercalating” an extra month periodically to realign with lunar and solar cycles, Palaima said.

The Julian calendar was 0.0078 days (11 minutes and 14 seconds) longer than the tropical year, so errors in timekeeping still gradually accumulated, according to NASA. But stability increased, Palaima said.

The Julian calendar was the model used by the Western world for hundreds of years.

Enter Pope Gregory XIII, who calibrated further. His Gregorian calendar took effect in the late 16th century.

It remains in use today and, clearly, isn’t perfect or there would be no need for leap year. But it was a big improvement, reducing drift to mere seconds.

Why did he step in? Well, Easter.

It was coming later in the year over time, and he fretted that events related to Easter like the Pentecost might bump up against pagan festivals.

The pope wanted Easter to remain in the spring.

He eliminated some extra days accumulated on the Julian calendar and tweaked the rules on leap day.

It’s Pope Gregory and his advisers who came up with the really gnarly math on when there should or shouldn’t be a leap year.

“If the solar year was a perfect 365.25 then we wouldn’t have to worry about the tricky math involved,” Eakes said.

WHAT’S THE DEAL WITH LEAP YEAR AND MARRIAGE?

Bizarrely, leap day comes with lore about women popping the marriage question to men.

It was mostly benign fun, but it came with a bite that reinforced gender roles.

There’s distant European folklore.

"One story places the idea of women proposing in fifth-century Ireland, with St. Bridget appealing to St. Patrick to offer women the chance to ask men to marry them," according to historian Katherine Parkin in a 2012 paper in the Journal of Family History.

Nobody really knows where it all began.

In 1904, syndicated columnist Elizabeth Meriwether Gilmer, aka Dorothy Dix, summed up the tradition this way:

“Of course people will say ... that a woman’s leap year prerogative, like most of her liberties, is merely a glittering mockery.”

The pre-Sadie Hawkins tradition, however serious or tongue-in-cheek, could have empowered women but merely perpetuated stereotypes.

The proposals were to happen via postcard, but many such cards turned the tables and poked fun at women instead.

Advertising perpetuated the leap year marriage game. A 1916 ad by the American Industrial Bank and Trust Co. read thusly:

“This being Leap Year day, we suggest to every girl that she propose to her father to open a savings account in her name in our own bank.”

There was no breath of independence for women due to leap day.

SHOULD WE PITY THE LEAPLINGS?

Being born in a leap year on a leap day certainly is a talking point. But it can be kind of a pain from a paperwork perspective.

Some governments and others requiring forms to be filled out and birthdays to be stated stepped in to declare what date was used by leaplings for such things as drivers licenses, whether February 28 or March 1.

Technology has made it far easier for leap babies to jot down their February 29 milestones, though there can be glitches in terms of health systems, insurance policies, and with other businesses and organization that don’t have that date built in.

There are about 5 million people worldwide who share the leap birthday out of about 8 billion people on the planet.

Shelley Dean, 23, in Seattle, Washington, chooses a rosy attitude about being a leapling.

Growing up, she had normal birthday parties each year, but an extra special one when leap years rolled around.

Since, as an adult, she marks that non-leap period between February 28 and March 1 with a low-key “whew.”

This year is different.

“It will be the first birthday that I’m going to celebrate with my family in eight years, which is super exciting, because the last leap day I was on the other side of the country in New York for college,” she said. “It’s a very big year.”

#Leap Year#calendar#equinoxes#solstices#Jet Propulsion Laboratory#California Institute of Technology#NASA#National Air & Space Museum#Julius Caesar#julian calendar#Pope Gregory XIII#gregorian calendar#Elizabeth Meriwether Gilmer#Dorothy Dix#leaplings

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

OPPY DAYS

Opening in theaters this weekend; on Prime Video November 23...

Robots have been a mainstay in movies for most of the past century, and one of the recurrent themes of such tales is the question of whether they are conscious entities, with personality and agency. Good Night Oppy is the first film I know of on this subject that isn't science fiction.

This documentary chronicles the careers of Opportunity and Spirit, two robotic Mars Rovers launched by NASA in 2003 to explore the Martian surface in search of evidence that there was once water, and thus possibly life, on the Red Planet. The project followed a couple of embarrassing and expensive NASA failures, the Mars Polar Lander and the Mars Climate Orbiter in 1998, both of which were ignominiously lost, in one mortifying case through human error caused by confusion between American measurement and the metric system.

Spirit and Opportunity, by contrast, were overachievers. Brilliantly designed and engineered, both remained operational for many years longer than their projected mission duration of 90 "sols" (Martian days) and added greatly to human understanding of Martian geology and natural history.

But impressive and interesting as their discoveries were, this isn't really what Good Night Oppy is about. The dramatic core of the film is about the degree to which the scientists and engineers who built the robots, and who supervised their activities from the Mission Control at the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, California, anthropomorphized their creations, attributed personalities to them, worried and fretted about them and ultimately mourned them.

Directed by Ryan White and gravely narrated by Angela Bassett, the film alternates convincing simulations of the endearing robots on the Martian surface, created at Industrial Light & Magic, with actual footage of their controllers monitoring and guiding them back at JPL. We watch the beautiful nerds age with them, frowning at their struggles and grinning at their triumphs like soccer moms.

One of the designers notes that the robot he worked on was "just a box of wires" but admits that she took on a human persona for him. Another notes that the supposedly identical rovers had distinct personalities; that Spirit was "troublesome" while Opportunity was "Little Miss Perfect." One of the project leaders says that to compare their relationship to parenting would be to "trivialize parenthood," but there's no doubt that the relationship these people feel toward Spirit and "Oppy" is parental.

There was something highly satisfying about watching a bunch of top-flight scientific minds enter matter-of-factly into thoroughly sentimental projection. After a while it's hard not to wonder if it is projection, or perhaps a sensitivity to the beginnings of a rudimentary sentience; to wonder if, at some level, human beings are not ourselves just boxes of wires that somehow attained self-awareness.

It should be noted that the filmmakers do nothing to discourage this idea; they don't explain, for instance, that the rather Harold-Pinter-ish plainsong sentences from the rovers were human translations of transmitted data, not verbatim statements. Even so, the effect of the film was, for me, not only thought-provoking but deeply emotional.

The soundtrack is also worth mentioning; it draws on the wake-up songs that were played at Mission Control at the beginning of the robot's shifts. Selections range from "Roam" by the B-52s to "S.O.S." by ABBA, and they all seem to take on deeper meanings in context. It would make a pretty good mix-tape album.

#good night oppy#nasa#ryan white#angela bassett#industrial light and magic#mars#mars rover#jet propulsion laboratory

45 notes

·

View notes

Link

Venus is found to still have volcanic activity in a study by Robert Herrick of UAF, Scott Hensley of JPL, and more.

#venus#planet venus#planetary science#volcano#volcanoes in space#veritas#solar system#University of Alaska Fairbanks#Jet Propulsion Laboratory#astronomy#planets#volcanism#veritas mission#Venus Emissivity Radio science InSAR Topography And Spectroscopy#jpl#uaf#space#venusian volcano#planetary studies#venusian

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Solar cell

#solar panels#solar power#dawn space probe#dawn spacecraft#dawn probe#nasa#clean room#energy#nasa discovery program#jet propulsion laboratory#aerospace#wikipedia#wikipedia pictures#solar cells

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

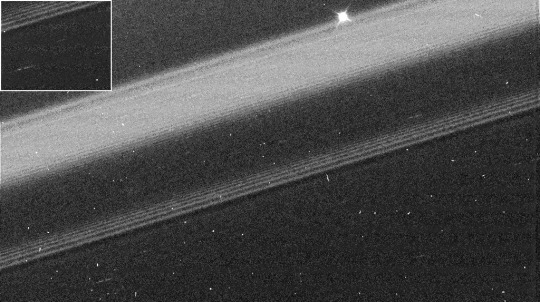

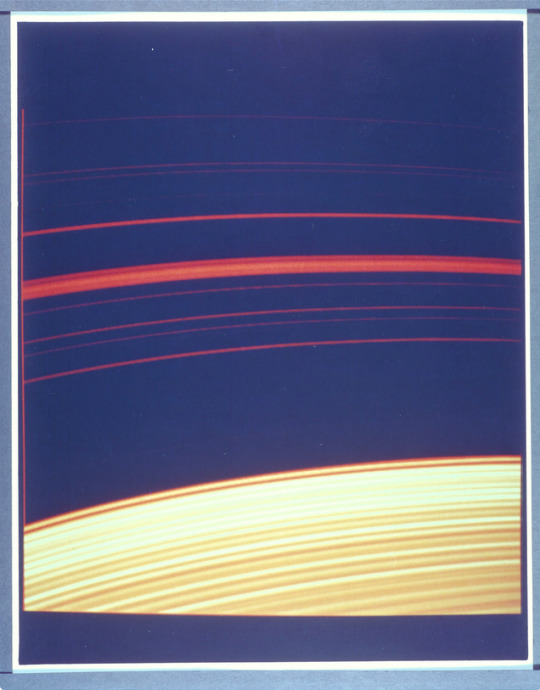

This computer generated photograph was created from a cross-section of Saturn's rings as measured by Voyager 2 photopolarimeter's occulation of the star Delta Scorpii. The region shown is near the inner edge of the Encke Division in the outer part of A-ring. (1981)

source

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

So long, Ingenuity!!! Perseverance loses a friend but you have us all invaluable data about the future of space travel.

1 note

·

View note

Text

JPL's Exoplanet Travel Bureau presents: Visions of the Future - MARS. Imagine a future time where humans are on Mars, and their history would revere the robotic pioneers that came first.

#nasa#nasa jpl#jpl#mars#visions of the future#future vision#travel posters#david delgado#illustration#lois kim#dan goods#invisible creature#imaginative travel destinations#jet propulsion laboratory

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

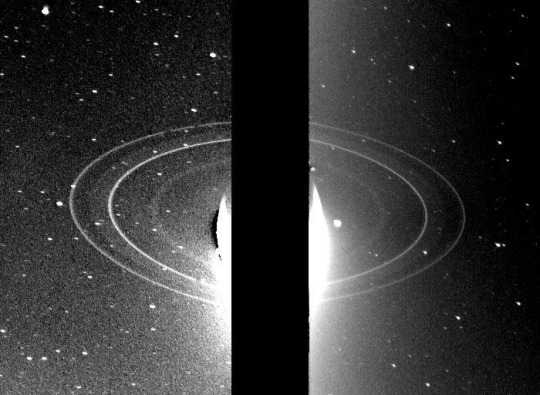

Voyager 2: Rings of Neptune (August 26, 1989)

#astronomy#krakenmare#astrophotography#solar system#nasa#jet propulsion laboratory#space#outer space#thank you nasa#neptune rings#neptune#voyager 2

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

doing some contract work with NASA and finally got to meet OPTIMISM and MAGGIE (earth testbed versions of Perseverance and Curiosity) thanks to Doug Ellison for showing me around :)

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

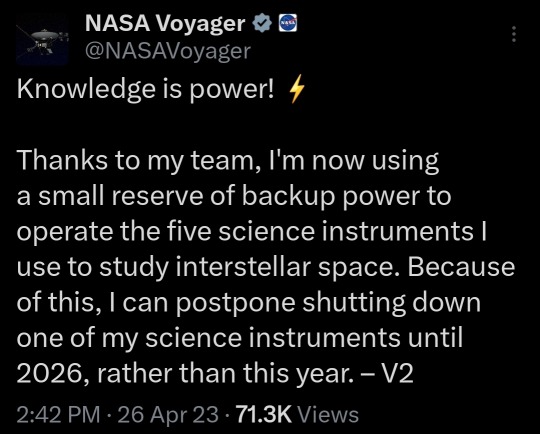

Y'all I'm so fucking happy rn - THREE MORE YEARS FOR MY FAVORITE MISSION! THREE MORE YEARS OF NEW INTERSTELLAR OBSERVATIONS!!!! 🤸🏿♀️

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

An image composite of Jupiter's moon, Europa, casting a shadow just over Jupiter's Great Red Spot from the Juno and Cassini spacecrafts.

#space#facts#outer space#nature#nature photography#space photography#astronomy#jupiter#great red spot#europa#europa moon#juno spacecraft#cassini#cassini spacecraft#nasa#nasa jpl#caltech#twitter#Jet Propulsion Laboratory

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

In the PBS kids’ show, Ready Jet Go! Jet Propulsion (voiced by Ashleigh Ball) is the main character and an alien from Borton 7. He relocates to Earth with his parents to study its customs. Once they settle in Washington state, Jet befriends Sydney, Sean, and Mindy. Jet has red hair and wears a blue puffy coat with blue pants and grey boots. To make his boots look a little more like they do on the show, you can wrap a red boot lace around them to give them their signature pop of color. Collect all the accessories of Jet Propulsion costume from Ready Jet Go! for Halloween and cosplay.

#pbs kids#ready jet go#borton 7#jet propulsion laboratory#jet propulsion#halloween cosplay#halloween costumes#findurfuture

4 notes

·

View notes