#Puma concolor couguar

Photo

(by Tom Littlejohns)

666 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cougar Puma concolor couguar

North Carolina Zoo — May 2022

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

meow

what are you top 3 cats

nya

1. Cougars

2. Sand cat

3. Ocelot

I really love cougars because their fur is so beautiful, and their babies are soooooooo smoochable! I love the earthy tone of them! That brown is sooooooooo prettyyyyy!

Sand cats are so tiny and they make me think of the fennec, one of my favorite animals! They dig holes, because they live in arid desert and in such heat it's necessary to stay underground, they have big ears, so they can hear rodents and snakes and such, they're cute little creatures!

Ocelots are mesmerizing, everything about them is eye-catching, and I could lose myself in their eyes for hours and hours! They have such a great coat that it's hard for me to look away when I see pictures of one, hahahah

Thank you so much for this question! <3<3<3

0 notes

Text

North American Cougar

Puma concolor couguar

Family: Felidae

Genus: Puma

Conservation Status: Least Concern

This feline stands out as one of the world's most versatile adaptors, thriving across diverse habitats in the Americas. Originally, multiple subspecies were designated due to this adaptability, but now only two remain valid: the North American and the larger South American variant.

Its fur displays variations based on habitat, becoming denser in colder regions and lighter in deserts or warmer zones. While not classified among the big cat species, it shares the closest kinship with the cheetah.

Cub cougars exhibit spots on their skin, providing camouflage, which gradually fade as they mature.

More information and awesome illustrations about animals? Here

No money? No problem.

Follows, likes and shares will help a lot too.

Quedamos QAP

#puma#cougar#north american cougar#felines#wild cats#cute animals drawing#illustration#drawing#scientific illustration#illo#wild animals#wildlife#animals#artist on tumblr#inforgraphics#conservation#animals in art

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Inktober 2019, Day 16: Wild.

Behold! One of Hope County’s most dangerous predators!

But right now, she’s taking a nap.

Peaches from Far Cry 5.

#inktober#inktober 2019#inktober2019#far cry 5#peaches#mountain lion#puma#cougar#couguar#puma concolor#hope county#ubisoft#nap#wild#my art#fan art#traditional art#peaches really is just a cat#I love her

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

About Mountain Lions

Mountain lions, also called cougars, may be found from the Canadian Yukon to the southern Andes of South America. They possess the largest territory of any wild mammal. Mountain lions are mostly solitary animals, preferring to hunt and sleep alone. A single male may require up to 175 square miles of territory for its home range.

Mountain lions are normally silent and nocturnal, preferring to hunt at night. They are extremely quick but have poor endurance. They kill their prey by biting the back of the neck to severe the spinal cord or the throat to crush the trachea. They will then drag the prey into the brush to consume. Any leftovers are covered with debris so the mountain lion can return later to finish its meal.

Mountain lions typically eat rodents, insects, racoons, birds, foxes, and deer.

Mountain Lion characteristics

Mountain lions have round heads with erect ears. They have five retractable claws on the front foot and four on the rear foot. The front feet are larger than the rear feet, useful for gripping prey. They range in height from 2-3 feet and are up to 8-feet long. They may weigh from 120 lbs. to 220 lbs. Males average about 150 lbs. Females weigh about 120 lbs.

Mountain lion color can vary widely from silvery-gray to reddish orange with light patches on the underbody, under the jaws, chin, and throat. Baby mountain lions are spotted with blue eyes and dark rings on their tails.

Mountain Lion tracking and signs

Tracks

To track a mountain lion, follow the traditional tracking method. Mountain lion tracks are roundish with diameters ranging from 2.75 to 3.75 inches. They show four toes, normally without claws. You can differentiate from the left and right track by the lead toe. The lead toe (2nd toe) sits further out than the other toes. The first toe next to it sits further back than all other toes. A lead toe on the left side indicates a right footprint.

Palm pads are trapezoid-shape with two lobes towards the front of the pad and three lobes toward the rear. The rear lobes, located at the base of the heel, may not show if the depression is not deep enough. The front tracks are larger, wider, and more asymmetrical than the hind tracks.

The mountain lion’s gait is typically an overstep walk (hind foot lands ahead of where the front foot had landed). The length varies from 15 to 30 inches.

The mountain lion may also direct register (hind feet step inside of where the front foot has landed), especially when moving through snow.

Like cats, the mountain lion will usually walk instead of run, making their tracks clean and undisturbed with an evenly distributed depression.

Scat

Mountain lion scat will be from 1 to 1 ½ inches in diameter. It will be formed into dense, blunted segments with a smooth surface and strong odor. It may contain meat remains but will almost never contain fruits, seeds, or nuts. The mountain lion may scrape the ground or cover scat with debris like a house cat.

Trails

Mountain lions prefer dense underbrush to use for stalking and unless moving toward water, may not follow a well-known animal trail.

Beds and lays

Mountain lions choose sleeping locations that help them avoid predators. They will often sleep on hard slopes near cliffs and outcrops and in dense plant cover. In snow, they well bed down on south-facing slopes.

Rubs

Mountain lions create marking signs to communicate with other cats. They may scrape the ground with their hind feet, then urinate over it. This marking is often found near kill sites. They will also occasionally scratch trees.

Misc Signs

Large dog tracks are often mistaken for cougar tracks. Dog tracks differ by their shape. They are usually symmetrical with no prominent lead toe. Dogs have a more triangular palm pad that is much smaller in relationship to the toes.

Groups and species

Argentine cougar (Puma concolor cabrerae) Pocock, 1940: includes the previous subspecies and synonyms hudsonii and puma (Marcelli, 1922)

Costa Rican cougar (P. c. costaricensis) Merriam, 1901

Eastern South American cougar (P. c. anthonyi) Nelson and Goldman, 1931: includes the previous subspecies and synonyms acrocodia, borbensis, capricornensis, concolor, greeni, and nigra

North American cougar (P. c. couguar) Kerr, 1792: includes the previous subspecies and synonyms arundivaga, aztecus, browni, californica, floridana, hippolestes, improcera, kaibabensis, mayensis, missoulensis, olympus, oregonensis, schorgeri, stanleyana, vancouverensis, and youngi

Northern South American cougar (P. c. concolor) Linnaeus, 1771: includes the previous subspecies and synonyms bangsi, incarum, osgoodi, soasoaranna, sussuarana, soderstromii, suçuaçuara, and wavula

Southern South American cougar (P. c. puma) Molina, 1782: includes the previous subspecies and synonyms araucanus, concolor, patagonica, pearsoni, and puma (Trouessart, 1904)

P. c. concolor in South America, possibly excluding the region northwest of the Andes, and

P. c. couguar in Central and North America, and possibly northwest South America.

Mountain lion tracks gallery

#gallery-0-4 { margin: auto; } #gallery-0-4 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-0-4 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-0-4 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */

How to identify Mountain Lion tracks and signs. About Mountain Lions Mountain lions, also called cougars, may be found from the Canadian Yukon to the southern Andes of South America.

1 note

·

View note

Text

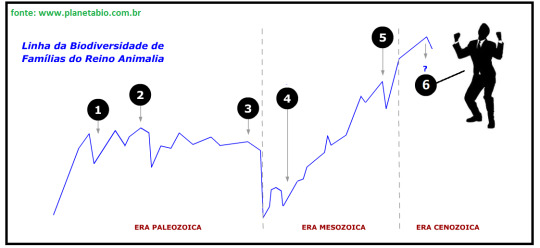

A Sexta Grande Onda de Extinção em Massa da História

À luz da ciência (muitas vezes distorcia por ideologias e teologias de botiquim), o planeta Terra foi formado há cerca de 4,6 bilhões de anos. Todo esse tempo é dividido pelos geólogos e paleontólogos em quatro grandes eras: pré-cambriano (de 4,6 bilhões a 542 milhões de anos atrás), paleozoica (de 542 a 251 milhões de anos atrás), mesozoica (de 251 a 65 milhões de anos atrás) e cenozoica (de 65 milhões de anos atrás até os tempos atuais). Sim, atualmente estamos atravessando a chamada Era Cenozoica. As primeiras formas de vida teriam surgido há aproximadamente 3,5 bilhões de anos.

Diversos estudos científicos, sustentados por um considerável registro fossilífero, mostram que durante todo esse tempo ocorreram 5 GRANDES EXTINÇÕES EM MASSA dos seres vivos.

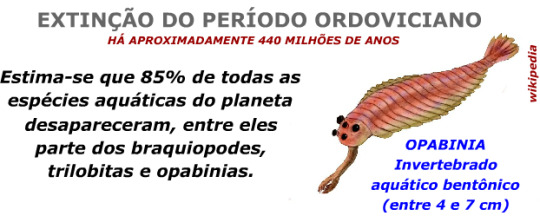

Extinção em Massa (1)- Era Paleozoica (Período Ordoviciano):

Extinção em Massa (2)- Era Paleozoica (Período Devoniano):

Extinção em Massa (3)- Era Paleozoica (Período Permiano):

Extinção em Massa (4)- Era Mesozoica (Período Triássico):

Extinção em Massa (5) - Era Mesozoica (Período Cretáceo):

Essas cinco extinções em massa foram consequências de eventos naturais, em um tempo que ainda não existia a espécie humana ou outros hominídeos. Mudanças climáticas e alterações geológicas (deriva continental) provocaram mudanças na paisagem terrestre e aquática, ao longo da história geológica da Terra, tendo como consequência, diversas alterações no meio, afetando diretamente o hábitat e os nichos ecológicos de milhares e milhares de espécies. Além disso, diversos processos de especiação (formação de novas espécies) ocorreram durante esses eventos.

As mudanças climáticas, as mudanças geológicas e os eventos de especiação são as causas naturais diretas e indiretas da extinção em massa de diversas espécies de animais e vegetais que viveram no passado.

Mas atualmente, na Era Cenozoica, possivelmente estamos presenciando a chamada SEXTA EXTINÇÃO EM MASSA, tendo o homem como principal protagonista causador desse processo. Bem mais que 322 espécies de vertebrados terrestres desapareceram do planeta nesses últimos 500 anos pela ação direta ou indireta do ser humano. Se formos levar em consideração os últimos 200 mil anos, tempo de existência aproximada do Homo sapiens, essa lista subirá para a casa do milhar. Desmatamento, poluição, tráfico de animais, tráfico de vegetais, introdução de espécies exóticas estão entre as principais ações humanas responsáveis pela grande onda de perda de biodiversidade mundial. “A culpa é dos “home”!

Entre as milhares de espécies consideradas extintas na lista vermelha da União Internacional para Conservação da Natureza (IUCN) está o lobo-da-tasmânia (‘Thylacinus cynocephalus’), marsupial nativo da Austrália e Nova Guiné. O último exemplar morreu em um zoológico australiano em 1936.

(foto: E.J. Keller/ Smithsonian Institution archives)

Diversas espécies estão consideradas em estado crítico ou praticamente extintas, dentre elas, espécies (ou subespécies) de rinocerontes, tigres, onça-pardas, aves, morcegos, anuros, primatas etc. O quadro é ainda mais complicado entre os invertebrados, com declínios de 45% na população de 2/3 das espécies examinadas.

Nos últimos 500 anos”, dizem diversos cientistas envolvidos com esse estudo que, “os humanos desencadearam uma onda de extinção, ameaça e declínio das populações locais de animais que pode ser comparada, tanto em velocidade quanto em magnitude, com as cinco extinções em massa anteriores da história da Terra”. O homem é um meteoro!

Nas escalas dos geólogos, 500 anos é realmente um piscar de olhos: nem sequer os efeitos do impacto de um meteorito têm uma duração tão curta, muito menos a formação do supercontinente Pangea.

Puma concolor couguar (Felis concolor couguar) do leste (América do Norte) é considerado oficialmente extinto

O desenvolvimento sustentável, uma nova lógica de consumo, a adoção de uma agricultura menos predatória, o reflorestamento e a preservação dos biomas naturais se fazem premissas básicas para que as espécies que ainda restam no planeta, sobretudo de vertebrados, consigam viver à ameaça humana e isso não é comunismo, é sobrevivência.

Fontes de consulta:

1- http://cienciahoje.org.br/coluna/a-caminho-de-uma-extincao-em-massa/

2- https://brasil.elpais.com/brasil/2014/07/24/sociedad/1406224017_140906.html

3- https://oglobo.globo.com/sociedade/sustentabilidade/puma-concolor-do-leste-considerado-oficialmente-extinto-16529108

4- Pough, F.H. A VIDA DOS VERTERBRADOS. São Paulo, Atheneu, 2003.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read the 2 articles; "Too Many Deer on the Road? Let Cougars Return, Study Says"

Read the 2 articles; “Too Many Deer on the Road? Let Cougars Return, Study Says”

Read the 2 articles; “Too Many Deer on the Road? Let Cougars Return, Study Says” and “Cougars in the wild in New York? Not yet, the state says” to consider two sides to the issue. Then use the PUMA CONCOLOR COUGUAR IN THE ADIRONDACK PARK: to inform the public about potential impacts of reintroducing cougars. Using these resources, write a response that summarizes the two arguments, presents…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Writer's Choice

Writer’s Choice

Read the 2 articles; “Too Many Deer on the Road? Let Cougars Return, Study Says” and “Cougars in the wild in New York? Not yet, the state says” to consider two sides to the issue. Then use the PUMA CONCOLOR COUGUAR IN THE ADIRONDACK PARK: to inform the public about potential impacts of reintroducing cougars. Using these resources, write a response that summarizes the two arguments, presents…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Vídeo mostra onças-pardas compartilhando presa; confira

Registro de hábitos alimentares do felino é relativamente raro; fora do Brasil o puma, como também é chamada a onça-parda, é foco do turismo de observação de onças. Biólogo especialista em felinos flagrou puma dividindo presa com filhotes

Um flagrante feito pelo biólogo Felipe Peters durante uma expedição no Chile mostra em detalhes uma relação curiosa e pouco comum entre as onças-pardas: a partilha da presa entre indivíduos da mesma espécie. No vídeo acima é possível identificar a presença de uma fêmea adulta e seu casal de filhotes dividindo um guanaco, mamífero nativo da América do Sul que chega a medir 1,30 metro de altura e pesar até 140 quilos.

“Interações sociais entre onças-pardas costumam ser mais associadas ao cuidado das mães com os filhotes. No entanto, estudos realizados no Parque Nacional Grand Teton (EUA) e no Parque Nacional Torres del Paine (Chile) demonstraram que interações entre adultos podem ser mais frequentes do que se imagina, sobretudo quando relacionados a períodos em que as presas estão agrupadas, ou em períodos de acasalamento”, comenta.

Fêmea foi clicada dividindo presa com dois filhotes

Felipe Peters/Arquivo Pessoal

O flagrante é pouco comum, não só pelos hábitos de caça solitários – típicos da espécie; mas também pela dificuldade em observar o comportamento de predação do felino na natureza. “O hábito furtivo e noturno das onças-pardas dificulta as observações diretas quanto à alimentação. A maior parte dos registros atuais está relacionada a estudos derivados de bases de dados indiretas, como análise de fezes e localização de presas recém abatidas”, explica Peters, biólogo do Instituto Pró-Carnívoros.

Carnívora, de médio a grande porte, a espécie ocorre nos mais variados habitat disponíveis, desde o extremo sul do Chile e Argentina até o noroeste dos Estados Unidos e Sul do Canadá. “O felino está adaptado as mais diversas condições ambientais, sejam elas relacionadas às planícies litorâneas ou às escarpas andinas, locais úmidos a nível do mar ou mesmo extremas nevascas e locais de altitudes que chegam até 5.800 metros”, comenta Marina Favarini, bióloga especialista em felinos (IPC).

“Essa grande área de distribuição geográfica reflete em diferentes hábitos e interações com culturas humanas, o que torna o puma uma das espécies mais icônicas entre os felídeos das Américas”, completa.

Indivíduo flagrado por armadilha fotográfica na Caatinga

Arquivo/Programa Amigos da Onça

A fácil adaptação aos mais diversos tipos de ambiente também é percebida no Brasil: a vasta área de ocorrência no País é comprovada, inclusive, na diversidade de nomes populares dados ao felino. “Os nomes nacionais comprovam a interação do animal em diferentes culturas locais, podendo ser popularmente conhecido por onça-parda, suçuarana, leão-baio, leão-da-montanha, onça-vermelha, ou simplesmente puma”, destaca Felipe.

Outro resultado da ampla distribuição geográfica é a existência de subespécies classificadas por Puma concolor concolor, na América do Sul, e Puma concolor couguar, na América do Norte e Central. “Tais variações morfológicas são notáveis ao longo da área de ocorrência, mas independente da condição sub-específica, indivíduos de maior porte geralmente estão associados a áreas montanhosas e sujeitas a neve. Já os de menor peso ocorrem em áreas de floresta tropical”, diz.

“Além das condições adversas de clima e relevo, os animais típicos de maiores latitudes possuem acesso a presas de maior porte, como os guanacos do extremo sul e os grandes cervos do extremo norte, situação que também exige uma maior potência e vigor físico para garantir o sucesso no abate”, completa Peters.

Indivíduos que ocorrem em maiores altitudes tendem a ser maiores e mais fortes graças à variabilidiade de grandes presas

Felipe Peters/Arquivo Pessoal

De maneira geral os machos adultos são maiores, pesando de 40 até 70 quilos, enquanto as fêmeas não ultrapassam os 50 quilos. “A coloração da pelagem é uniforme, com o ventre amarelo esbranquiçado e a parte dorsal que varia entre tons pardos ou avermelhados, independente da localidade”, comenta Marina.

Tido como “Vulnerável” na Lista Brasileira de Espécies Ameaçadas de Extinção, o felino é vítima da perda e fragmentação do habitat – resultado da expansão agrícola, industrial e urbana; assim como caça motivada por retaliação à predação de animais domésticos e atropelamentos nas estradas e rodovias de todo o País. “Estimativas da Oficina de Avaliação do Estado de Conservação dos Mamíferos Carnívoros do Brasil, realizada pelo ICMBio, apontam que o tamanho populacional da espécie possa ser menor do que 10 mil indivíduos para a Amazônia, menor que 2.500 indivíduos para o Cerrado e Caatinga, e menor que mil indivíduos para a Mata Atlântica e Pantanal, além de ser desconhecida para o Pampa”, reforça a bióloga.

Fêmeas são menores que os machos, pesando até 50 quilos

Felipe Peters/Arquivo Pessoal

Turismo de observação

O turismo de observação de onças-pintadas movimenta a economia local do Pantanal Brasileiro e, graças ao envolvimento da comunidade em proteger os animais, estimula a conservação da espécie. No entanto, a prática para observação de onças-pardas não é comum no País. “Esse tipo de turismo é internacionalmente reconhecido para algumas regiões do extremo sul da Argentina e do Chile, como por exemplo o Parque Nacional Torres del Paine e as propriedades privadas do entorno”, comenta o biólogo do Instituto Pró-Carnívoros, Fábio Mazim.

De acordo com o especialista em felinos, a densidade de onças-pardas no parque estimada – no fim da década de 90, já considerava cerca de seis indivíduos a cada 100 quilômetros quadrados. “No entanto, já era admitida a possibilidade das populações crescerem, devido às políticas de proteção às presas, proibição de caça e potencial turístico”, diz.

“Os pecuaristas chilenos vislumbraram que era financeiramente mais vantajoso manter pumas vivos, para o deleite de fotógrafos e amantes da natureza, mesmo com os ocasionais abates de ovinos”, completa.

Mesmo com o nome de ‘onça’, espécie se assemelha mais ao felino jaguarundi

Felipe Peters/Arquivo Pessoal

Prima da onça-pintada?

Por mais que as espécies carreguem ‘onça’ no nome popular, a onça-parda e a onça-pintada podem ser considerados parentes distantes dentro da família Felidae. Embora a onça-parda seja o segundo maior felídeo do Brasil, ela possui características evolutivas mais relacionadas às espécies de pequeno porte, como o jaguarundi e os gatos-do-mato, do que propriamente da onça-pintada.

A principal diferença evolutiva é a vocalização. Diferente da ‘rainha das florestas’ e de outros grandes felinos como leões, tigres e leopardos, a onça-parda não esturra, nem urra: o som emitido é similar a um miado.

Ágil, o felino é capaz de realizar grandes saltos tanto em distância quanto em altura, além de conseguir escalar árvores com facilidade, seja para alcançar uma presa ou fugir de ameaças.

A onça-parda é um dos felinos mais bem adaptados aos diferentes ambientes

Felipe Peters/Arquivo Pessoal

The post Vídeo mostra onças-pardas compartilhando presa; confira first appeared on Diario de Campinas.

from WordPress https://ift.tt/3eAmGDc

via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

(by savannahrosewildlife)

389 notes

·

View notes

Text

Several posts have been going across my dash in a short amount of time that are making an effort to use the species binomials for the animals they are talking about. This is great! I love it! Here’s how it works and why it matters.

Species binomials (or scientific names or Latin names) were created to standardize how we recognize and organize different groups of life and name each unique type. This naming systems is a way that can be recognized by the scientific community across multiple different cultures with different languages. For many species, it gives them the unique name when they have may not have one - either in the past grouped in with other species, the name may be lost with the loss of the Indigenous cultures and languages, or simply overlooked - and naming something gives them an identity to promote their inherent value. This population of life is unique. We recognize it. We want to preserve and protect it. It’s a Proper Noun instead of a generic noun.

(Without going too deep into the history of taxonomy, there is absolutely a discussion to be had about an international standard with European roots. The naming conventions are based on Latin script and language, which makes it inherently biased toward European languages. It has grown and matured since its 18th-century conception, and naming codes are more of a multicultural effort now. This standardization is much more recent than many people believe, with international standardization starting in the early 20th-century and constantly updating. For animals, we’re using the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) established in 1999. For plants, the most recent naming codes, the Shenzhen Code, is new as of 2018. It is, in essence, its own little language with an obscure paper trail, made up on the fly, including regional twists that may not be formally recognized and are always up for debate, ultimately made by people, flaws and all, and held to scientific rigor that demands we constantly examine and reexamine to reject that which is unsupported.)

Because these are names, and names are important, we made rules to recognize them. Much like how we capitalize people’s names, capitalization matters for species, too. The individual words of people names are often each capitalized: Keanu Charles Reeves, for example would look weird as Keanu charles reeves or keanu Charles reeves or Keanu Charles reeves, etc. (Tumblr, in particular, is a playground for language, and playing with these conventions to test effective communication styles is much more common here, so keanu charles reeves doesn’t look as weird here, but context matters.) These names can stand alone and still be meaningful, but that is not the case for species names.

The names of species have two words that are not independent of each other, unlike human names. We call ‘Keanu’ the first name and ‘Reeves’ the last or surname, but for species, the entire grouping of words is the name. As such, we only capitalize the first part of the name: Homo sapiens. We do not call humans Homo by itself, because that is the genus Homo sapiens belongs to. It stands alone as a grouping of closely related species. There are other species within that genus, and claiming that Homo sapiens reflects all of Homo erases our cousins, even if they are extinct. If we are talking about a species in Homo but we are not specifying which one, we say Homo sp., or Homo spp. for many species. It’s rare to talk about the genus as a whole simply because grouping traits are often fewer and less interesting than the distinguishing traits for each species and because exceptions may exist that we don’t know about and thus risk assuming. (This is super common in insects, where grouping ‘rules’ are more like ‘guidelines’ because bugs fucking love evolution.)

The ‘sapiens’ bit is called the epithet - it is the distinguishing part of the name to reflect the unique species in the genus. It is never capitalized as part of the name because it never stands alone. The epithet ‘sapiens’ doesn’t get reused except in fiction (which I think is an unspoken rule - oh the vanity of humans), but other epithets are commonly reused for many species . One redditor made a list of the most common epithets used in botany. Ironically, the most common epithet is ‘vulgaris’, which means ‘widespread’ or ‘common.’ It is often assigned to the most commonly found member of that genus: Beta vulgaris (beets, chard), Vespula vulgaris (European yellowjackets), Sturnus vulgaris (European starling), etc. There may be many species with the epithet ‘vulgaris’ but only one may have epithet per genus. Locations are often used as epithets - Canada, America, and Japan are common - but they are still not capitalized, i.e. Tsuga canadensis, Fraxinus americana, Camellia japonica.

Some populations are recognized to be “subspecies” or ‘varieties’ which is to say, a distinct population within the species that, given enough time and isolation, could to be on their way to becoming distinct species themselves. This is a whole Thing in taxonomy that gets complicated and has a nasty history of racism when white people attempted to applied the concept to humans. The easiest way of quickly summarizing this is that they are strings of epithets following the first, usually capping at one extra, but things can get weird the more obscure you go. An easy example is Puma concolor, the mountain lion found (historically) throughout most of continental Western Hemisphere, and its Eastern North American subspecies, Puma concolor couguar, which is mostly now only found in Florida and is endangered.

Species names are often italicized or underlined as a way of making them stand out in a block of text. That’s it. It’s an attempt to make the names more formal and static as opposed to the fluidity of casual language, and because some names are words we use in everyday language. I don’t see a lot of conversation about this, but I do wonder if it is something that will change over time, as many people in the scientific communication community cheer on the use of species scientific binomials instead of common names.

See, common names for organisms are interesting playgrounds of language. A single animal or plant might have dozens, hundreds even, of common names attributed to it. The mountain lion is a classic example, with 40 common names in English alone! It’s always fun to read through 19th-century scientific literature and find obscure common names. Manitises were once called “devil’s riding horse” in the Eastern US. The insects commonly called thrips (Thysanoptera) were once called twitters! There is a lot of fun and joy to be had in common names at the local level, but at the global scale, it gets messy.

Catch-all common names can muddy communication, and it is a major issue for regulating harvest of organisms that we use for food and utility, leading to overharvest and extinction. “Whitefish”, something you might find at your fishmonger, grocery, or restaurant menu, refers to at least seven different species of fish. A recent study found a disturbing amount of fraud regarding the species of fish sold mismatching the name they were sold under to consumers, something made easier because our common names apply to so many types. Commercial fishers are lying (either intentionally or unintentionally), skirting regulation, making it difficult to understand what is happening to the fish populations we use for food.

Wood is the other major area where common name confusion allows for overharvesting and fraud. There are easily 40 different species called “rosewood”: At least 20 some Dalbergia species are called “true rosewood” and an additional 20 species from other genera that look similar. A good number of the tree species called rosewood are overharvested and endangered. Good luck figuring out what species of tree composes your rosewood guitar! I’ve found it exceedingly difficult to track the sources of wooden materials, which emphasizes how challenging it is to have “perfect knowledge” of your buying power. Saying that “oh this is just whitefish” or “oh this is just rosewood” allows for rare species to be lumped in with common species, and the overharvest of those species can go unnoticed by the person requesting the order half-a-globe away. What regulations do exist appear to allow for this ambiguity or are otherwise infrequently enforced for smaller harvesting businesses. (I’ve asked a supply chain specialist how we can show support for wanting better international supply chain transparency, and the answer was a long sigh.)

There are racist and other gross attributions among common names, and it is an ongoing effort to get those formally changed, but because those names are frequently used everyday language, it’s more of an effort to get people to change habits and stop using them. Using their binomial is a great substitute for this, because it is clarifies communication across communities. It’s already more commonly done among gardeners, even if they don’t realize it: Common ornamentals like hydrangeas and viburnum are the genus-level names for those flowers!

The big reason I like using the species binomial over common names is that it gives those species recognition that can be universally appreciated. I started this long post with this concept, but recognizing the diversity of life on this planet is so important to our survival. Diversity is strength, and the recognition of the unique combinations of species that make up communities around the world makes those places special. The unique biota of every region of the planet contributed to the unique human cultures that developed there. They contributed to their food, their technology, their clothes, their architecture, their daily patterns, their language. Naming the species, communicating their unique identities, contributes to preserving those cultures. It gives these plants and animals the power of being appreciated by all.

Disclaimer: I’m an entomological and invasion ecologist, so not a specialist in taxonomy, human ecology, etc., but this is a simple guideline for utilizing taxonomic language and understanding where it intersects with society.

0 notes

Photo

Cougar Puma concolor 美洲狮 . . . . . . . . . . . . . #美洲狮 #puma #Pumaconcolor #山狮 #poema #pakawipark #olmensezoo #couguar #Silberlöwe #Berglöwe #Kuguar #liondemontagne(在 Pakawi park) https://www.instagram.com/p/CFabb9hqkBi/?igshid=1mapysg1ow75g

#美洲狮#puma#pumaconcolor#山狮#poema#pakawipark#olmensezoo#couguar#silberlöwe#berglöwe#kuguar#liondemontagne

0 notes

Photo

Name: Eastern cougar

Scientific Name: Puma concolor couguar

Diet: Carnivore

Date: Was declared extinct on 22nd January 2018.

Size: Adult cats average from 6 feet (females) to 8 feet (males) long, including their tail.

Weight: Males, at around 140 pounds, are larger than females at about 105 pounds.

Location: Northeastern North America

Additional Information: DNA testing in 2015 strengthened the theory that North American Cougars are a single subspecies.

Wildlife Service - http://www.fws.gov/nc-es/mammal/cougar.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17774416

0 notes

Photo

Florida Panther

The Florida panther is an endangered population of cougar (Puma concolor) that lives in forests and swamps of southern Florida. Florida panthers are usually found in pinelands, hardwood hammocks, and mix swamp forests. This population, the only unequivocal cougar representative in the eastern United States, currently occupies 5% of its historic range. In the 1970s, there were an estimated 20 Florida panthers in the wild, although their numbers have increased to an estimated 230 by 2017. In 1982, the Florida panther was chosen as the Florida state animal.

Florida panthers are mid-sized for the species, being smaller than cougars from Northern and Southern climes but larger than cougars from the neotropics. Adult female Florida panthers weigh 64–100 pounds whereas the larger males weigh 100–159 pounds. Total length is from 5.9 to 7.2 feet and shoulder height is 24–28 inches.

The Florida panther has long been considered a unique subspecies of cougar, under the trinomial Puma concolor coryi, one of thirty-two subspecies once recognized. The Florida panther has been protected from legal hunting since 1958, and in 1967 it was listed as endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; it was added to the state's endangered species list in 1973. A genetic study of cougar mitochondrial DNA has reported that many of the supposed subspecies are too similar to be recognized as distinct, suggesting a reclassification of the Florida panther and numerous other subspecies into a single North American cougar (Puma concolor couguar). Despite these findings it is still listed as subspecies Puma concolor coryi in research works, including those directly concerned with its conservation.

The Florida panther has a natural predator, the alligator. Humans also threaten it through poaching and wildlife control measures. Besides predation, the biggest threat to their survival is human encroachment. Historical persecution reduced this wide-ranging, large carnivore to a small area of south Florida. This created a tiny isolated population that became inbred (revealed by kinked tails, heart, and sperm problems).

The two highest causes of mortality for individual Florida panthers are automobile collisions and territorial aggression between panthers. Primary threats to the population as a whole include habitat loss, habitat degradation, and habitat fragmentation. Fragmentation by major roads has severely segmented the sexes of the Florida panther.

In a study done between the years of 1981 and 2004, it was seen that most panthers involved in car collisions were male. However, females are much more reluctant to cross roads. Therefore, roads separate habitat, and adult panthers. While young males wander over extremely large areas in search of an available territory, females occupy home ranges close to their mothers. For this reason, panthers are poor colonizers and expand their range slowly despite occurrences of males far away from the core population.

Of all the puma subspecies, the Florida panther has the lowest genetic diversity due to a variety of environmental and genetic factors. The lower genetic diversity and higher rates of inbreeding, led to the increased expression of deleterious traits in the populations, resulting in lower overall fitness of the Florida panther population. Specifically concerning the Florida panther, one of the morphological consequences of inbreeding was a high frequency of cowlicks and kinked tails. The frequency of exhibiting a cowlick in a Florida panther population was 94% compared to other pumas at 9% while the frequency of a kinked tail was 88% as opposed to 27% for other puma subspecies. A solution that was implemented to increase genetic diversity of the Florida panther was the introduction of eight Texas pumas to the Florida panther population in efforts to restore genetic diversity and promote the survival of the native population. The results indicated that the survival rates of hybrid kittens were three times higher than those of panthers without introduced genes.

209 notes

·

View notes

Photo

218) Puma wschodnia, eastern cougar, eastern puma (Puma concolor cougar) – podgatunek pumy, który żył we wschodnich stanach USA, został uznany za wymarły. Amerykanski urząd ochrony przyrody, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, po szczegółowych badaniach orzekł, że najprawdopodobniej wszystkie relacje o tym drapieżniku po 1930 r. były fałszywe lub dotyczyły pum południowoamerykańskich zbiegłych z niewoli, i przed tą datą Puma concolor couguar została wytępiona. Żyje jeszcze odrębny podgatunek na Florydzie, Puma concolor coryi (dziwnie i błędnie zwana tam "Florida panther"), ale jest tych pięknych kotów tylko 80-100 sztuk.

0 notes