#battle of austerlitz day

Text

Happy Julius Caesar gets stabbed day! Here’s a Les Mis take on the subject, courtesy of Grantaire’s Drunken Rambles:

Whom do you admire, the slain or the slayer, Cæsar or Brutus? Generally men are in favor of the slayer. Long live Brutus, he has slain! There lies the virtue. Virtue, granted, but madness also. There are queer spots on those great men. The Brutus who killed Cæsar was in love with the statue of a little boy. This statue was from the hand of the Greek sculptor Strongylion, who also carved that figure of an Amazon known as the Beautiful Leg, Eucnemos, which Nero carried with him in his travels. This Strongylion left but two statues which placed Nero and Brutus in accord. Brutus was in love with the one, Nero with the other. All history is nothing but wearisome repetition. One century is the plagiarist of the other. The battle of Marengo copies the battle of Pydna; the Tolbiac of Clovis and the Austerlitz of Napoleon are as like each other as two drops of water. I don’t attach much importance to victory. Nothing is so stupid as to conquer; true glory lies in convincing. But try to prove something! If you are content with success, what mediocrity, and with conquering, what wretchedness! Alas, vanity and cowardice everywhere. Everything obeys success, even grammar. Si volet usus, says Horace. Therefore I disdain the human race.

254 notes

·

View notes

Text

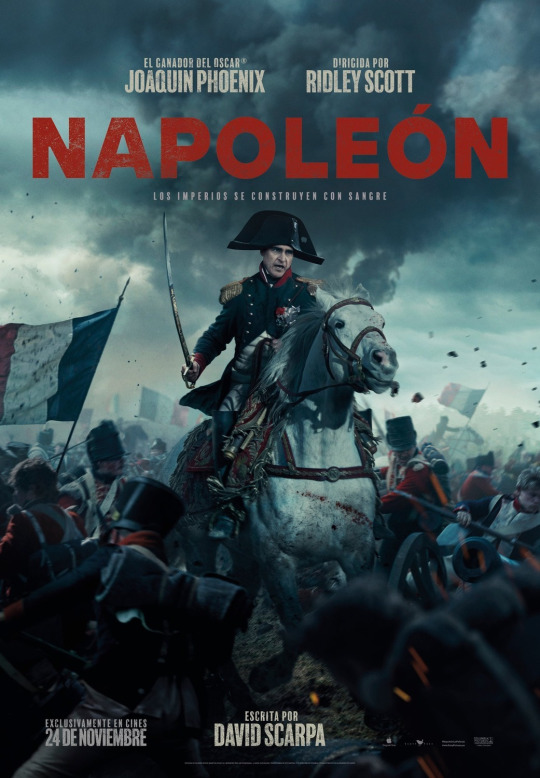

I’m just a defense analyst, so I’ll leave a proper critique of Ridley Scott’s new blockbuster biopic Napoleon to the many reviewers who have already disparaged it. I, for one, found it to be a lukewarm mélange of battle scenes and romantic vignettes, leaving me with neither a sense of the man Napoleon Bonaparte—the bicorne-hatted soldier-turned-emperor of the French—nor a feel for the age of upheaval he so much defined. For a grand piece of historical fiction from the director of such masterpieces as Blade Runner, Thelma & Louise, and Black Hawk Down, the film curiously fails to entertain.

My perspective on Napoleon is a different one. Scott’s film stands in a long line of movies, novels, and even history books that have given the world an entirely wrong view of how wars are fought—and even more importantly, how they are won. And that matters, because the mythical idea of war embedded in Napoleon and so many other works has become so widespread in our culture and discourse that it ends up informing actual decisions about actual wars.

Let’s call it the decisive battle myth. Napoleon, with its focus on famous battles such as those of Austerlitz and Waterloo, perpetuates the dangerous idea that wars are decided by great and bloody clashes. This obsession is as old as there have been written accounts of history, but in popular culture in the English-speaking world, the myth can be traced back to the 1851 publication of The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World: From Marathon to Waterloo, which helped kickstart an entire genre of works focusing on battles supposed to have singlehandedly changed the course of history. In film, think of The Longest Day, Midway, and Stalingrad; in books, the list of battle histories and battle fiction is too long to contemplate. The genre even plays in counterfactuals: The 1993 movie Gettysburg, based on Michael Shaara’s novel The Killer Angels, suggests that the South could have won the U.S. Civil War had the Battle of Gettysburg gone the other way.

No matter what these works have taught us to think, the decisive battle is a myth. Wars between major powers are not decided by great battles but by attrition of soldiers and materiel, which in turn is determined by such things as force size, logistics, production, and technology. Battles, large and small, are important only to the extent to which they accelerate attrition and wear down the other side. Yet the myth of the decisive battle—the idea that an adversary can be defeated in one big and bloody but short engagement—remains powerful. It’s also dangerous, because it affects not only ordinary moviegoers but military and political leaders as well. In other words, the very people deciding whether to start and how to fight a war.

Scott’s focus on battles is hardly surprising. Napoleon fought numerous campaigns culminating in big set-piece battles, after which the defeated side sought peace; at the Battle of Austerlitz, Napoleon defeated the allied armies of Austria and Russia, forcing the former to sue for peace and the latter to retreat home. But the French emperor’s most celebrated victory—exactly 218 years ago today—was only an episode in a long war that did not end until 10 years later, after attrition and mutual exhaustion.

The focus on decisive battles orchestrated by a brilliant military leader such as Napoleon has been poisoning Western military thinking for centuries by suggesting that great power wars can be short affairs. The idea that an adversary can be decisively beaten in just one or a few engagements has incentivized political and military gambling: Think of the German Schlieffen Plan that bet on a single, decisive encirclement of French forces and their quick annihilation or capitulation in 1914, with the disastrous result of condemning much of Europe to four years of attrition with millions of soldiers killed. The idea of a quick, decisive battle inspired then-Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein to invade Iran in 1980, which led to a horrifically bloody eight years of attrition.

More recently, Russian President Vladimir Putin thought one decisive push toward Kyiv in early 2022 would quickly and painlessly conquer Ukraine. Hundreds of thousands of deaths later, the grinding war goes on. For all the emphasis on Napoleon’s quick campaigns and decisive battles, his wars tell a similar story of long and painful attrition: More than 5 million European soldiers were killed or otherwise died during the Napoleonic wars, a level of carnage, relative to total population, on par with World War I. France alone lost around 860,000 soldiers, including 38 percent of all men born between 1790 and 1795.

That Napoleon is only a movie doesn’t make it better. There are documented cases of films influencing a policymaker’s decisions to go to war. In 1970, for example, then-U.S. President Richard Nixon repeatedly watched the film Patton during the decision-making process to expand the Vietnam War into Cambodia, taking inspiration from the movie general’s willpower and single-minded belief in U.S. military power. One academic study found that popular culture, including fictional films, can frame the way we think about a multitude of issues, and there is no reason to believe that military officers and policymakers are exempt from these effects. Movies can help prevent wars, too. Former U.S. President Ronald Reagan was inspired by the television film The Day After and Tom Clancy’s novel Red Storm Rising to push for nuclear arms control. But if decision-makers and military leaders are prone to fighting the wars of their imagination, then a popular culture that reinforces the idea that wars can be short and decisive may incentivize willingness to look for a quick military solution to a political problem.

There is much more in Napoleon that made me cringe as a military analyst. What you see on the screen has absolutely nothing to do with warfare in the age of Napoleon—as a matter of fact, the clouds of gunpowder from the era’s muzzle-loaded muskets meant you would not be able to see very much on a Napoleonic battlefield to begin with. The battle scenes are a Hollywood mishmash of medieval melees, meaningless cannonades, and World War I-style infantry advances.

One scene that stands out is the apocryphal depiction of Napoleon leading a cavalry charge into what are supposed to be the Russian lines at the Battle of Borodino. As a former artillery officer, of course, Napoleon never led a cavalry charge in his life. For all of Scott’s fixation on Napoleon’s battles, he seems curiously disinterested in how the real Napoleon fought them—and just as disinterested in the changing character of Napoleonic warfare. By 1812, Napoleon’s enemies had not only learned to adapt by emulating the French style of fighting, but the battles themselves had turned into meat grinders of such a scale that no individual could control them. The battles of Wagram (in 1809), Borodino (1812), and Leipzig (1813) each involved hundreds of thousands of troops and many hundreds of cannons. The idea that the commander of his country’s armies in an 1812 battle had the liberty to lead a horse charge is so preposterous that the scene makes Mel Gibson’s Braveheart—considered one of the most historically inaccurate films in recent decades—look like a paragon of historical realism.

Napoleon’s military genius was not just about individual heroism or skilled battle tactics, but more importantly his vision for structural reforms. Napoleon helped institutionalize the corps system, dividing up large armies into smaller ones as a way to enable more effective command and control, as well as greater speed and range. Key to this new corps system were Napoleon’s marshals, distinguished military officers who sometimes remained undefeated in battle and whose deaths Napoleon mourned deeply. It was the marshals and other officers to whom Napoleon delegated authority; they proved to be a major asset contributing to his victories. In the film, these colorful independent actors are relegated to the role of footmen.

The film’s wild inventions go much farther. The British Army, led by the Duke of Wellington, features prominently, even though it played only a minor role in battle. Rather than the fighting role, the British contribution to Napoleon’s defeat lay in the sea blockade and in financing the huge standing armies of Austria, Prussia, and Russia that bore the brunt of the fighting. The duke and Napoleon never met in person, another invention of the movie that could have been omitted without loss, since it is devoid of meaningful dialogue that might have helped the audience better understand Napoleon’s volatile and ruthless character. Scott could instead have depicted the heated argument between Napoleon and Austrian diplomat Prince Klemens von Metternich during their famous eight-hour encounter in Dresden, then the capital of the Kingdom of Saxony, in 1813. The meeting convinced Metternich of the French emperor’s troubling mental state and the impossibility of making peace as long as he reigned.

There is no reason to believe that the myth of the decisive battle will lose its power any time soon. As the historian Cathal J. Nolan writes in The Allure of Battle: “The idea of decisive battle will always be more alluring than winning by attrition—morally and aesthetically; to generals and theorists, and to publics hungry for war news.” Nolan might have added film directors to his list.

Let us hope that U.S. and NATO military strategists and force planners do not draw too deep an inspiration from Scott’s depiction of Napoleonic battle. It’s bad enough that the allure of the decisive battle is already shaping U.S. deliberations over how to fight a possible future war with China over Taiwan. Disregarding the likely attritional character and extended length of such a fight—and the requirements in manpower, weapons, ammunition, production capacity, and political constancy that would entail—could spell disaster for the United States and its allies. Focusing on long attrition instead of dramatic clashes would certainly make for a boring film experience, especially since one only has to look at Ukraine to see the long slog of attrition playing out in real life. Nonetheless, stripping Napoleon of the romanticism associated with epic battles decided by the archetypal hero on horseback would be a small first step in gaining a better understanding not only of past wars, but also of how future wars will be fought.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wait wait urrgggh I was reminded of another thing in Ridley Scott’s Napoleon I hated

After the “battle” of Borodino (all 40 seconds of it) there’s some text in screen saying 28.000 French dead. This is only done here.

There are arguably 6 battles in this movie (Toulon, 13 Vendémiaire, Pyramids, Austerlitz, Borodino, Waterloo).

Why is a text like this only shown during one of them?

Why does it only show French casualties? Why not the Russian numbers also (some 44k to 52k)?

Is it just to reflect Napoleon’s ‘butcher’s bill’, a tyrant feeding his own people into the grinder as Sir Scott would like to remind us? Because the mere 289 French killed/wounded at the battle of the Pyramids and 1288 at Austerlitz would throw that narrative into question too much to do this with any level of consistency over the course of the movie - even if it might in some distant way have helped provide the movie any kind of actual thematic throughline (“Napoleon sacrifices many French for his own ambitions”)

And Sir Scott was probably in an equally problematic dilemma when it came to adding Napoleon’s opponents’ losses because it would tragically, unintentionally reveal to the audience Napoleon was actually a very good general (enemy losses at the Pyramids, Austerlitz and Borodino were some 10.000, 15.000 (including wounded, and another 12000 prisoners) and 44.000), rather than it being ‘just a thing he sometimes did’ for unexplained reasons, in between having a bad relationship with Josephine. Scott already did his best to ignore Napoleon’s two most brilliant campaigns: The Italian Campaign and 1814 Six Days.

Just one more weird, inconsistent directing choice for this movie. Rant over.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mabeuf!!!

Mabeuf is hilarious. He's apolitical, although he respects those who are not, but he also happens to be growing the most political fruit in 1830s France: the pear. Although the connection to Louis-Philippe isn't made here, it does suggest that as much as one may want to remain distanced from politics, circumstances determine how much a person is able to maintain that distance, not the person themself. Mabeuf may have no political opinions, but that doesn't mean that politics don't affect him, or that others can't read politics into his actions (as I just did; he doesn't mean anything with those pears, but I can't see a pear without thinking of Louis-Philippe). More importantly to Mabeuf, only the truly fortunate can really escape politics:

"The Revolution of July brought a crisis to publishing. In a period of embarrassment, the first thing which does not sell is a Flora. The Flora of the Environs of Cauteretz stopped short. Weeks passed by without a single purchaser."

Mabeuf is poor in a similar way to Marius, where he's able to get by and even pay for some "luxuries" (as in, some simple enjoyments and/or a hobby), but his financial stability could disappear very quickly. The publishing crisis after the July Revolution caused just that. Without income from publishing, his situation became much more precarious, and while he still seems content and didn't suddenly become political, the consequences of politics on his life demonstrate the challenges of that position. It's nice that he's not prejudiced in the way Gillenormand is because of his "neutrality," but he's also not advocating for himself when these changes really do affect him. In a way, he's similar to Bishop Myriel, whose community efforts were great in every respect except the political. Mabeuf doesn't have that level of authority, but he shares many sentiments with the bishop: love of people (it's why he goes to church), respect for nature and knowledge, and a generally kind attitude. His lack of political beliefs hurts him more than it hurts his community, but it's still interesting to see this "flaw" repeated in a different way.

It's intriguing how Mabeuf's apolitical stance is linked to his distaste for violence as well. For instance, while he's friendly with several Bonapartists because he won't condemn their opinions, he's also extremely uncomfortable living at "Austerlitz," which shares the name of a famous battle during the Napoleonic Wars. Additionally, he flinches at all violence, with the example given being linked to the French Revolution. Weapons from the Invalides were used to storm the Bastille, so while Mabeuf is just avoiding a place because he dislikes cannons, he's also overlooking the way that politics is all around him because he detests violence. His stance on violence isn't wrong - we see a variety of justifiable positions on violence in the novel, with Valjean falling in the "no violence at all" camp as well - but the (a)political framing of his nonviolence is telling. It may be that he dislikes politics because he sees it as inherently violent (which is fair, given that he's lived through many violent moments in French history), which says as much about his experiences with politics as it does his personal feelings.

Even though Mabeuf's avoidance of politics is definitely a bad thing in a book with a very political message, I really love his character. He just loves books and plants! That's great for him, and it would be a pretty ideal way of life if he lived in a system that didn't place his livelihood at constant risk. He also has what is probably the best response to being asked about relationships that I've read:

"However, he had never succeeded in loving any woman as much as a tulip bulb, nor any man as much as an Elzevir. He had long passed sixty, when, one day, some one asked him: “Have you never been married?” “I have forgotten,” said he. When it sometimes happened to him—and to whom does it not happen?—to say: “Oh! if I were only rich!” it was not when ogling a pretty girl, as was the case with Father Gillenormand, but when contemplating an old book."

"I've forgotten" is definitely the funniest way to answer that question, and I love that books are his main motivation in everything. Hugo's a bit crueler about Mother Plutarque's similar avoidance of relationships, saying "None of her dreams had ever proceeded as far as man. She had never been able to get further than her cat." "Proceeded" implies that love of a man would be better than love for her cat, which also suggests that she should have gotten married. Granted, this is only implied here, but it does seem to be another instance of the strange tension between there being a lot of unmarried, somewhat sympathetic women in this book and Hugo thinking that marriage/motherhood is the ultimate goal for women. Mother Plutarque seems quite content with her cat, though, so if it weren't for the issue of poverty, she and Mabeuf would have been pretty happy with their very bookish lives.

#les mis letters#lm 3.5.4#mabeuf#mother plutarque#I think that Mabeuf and Mother Plutarque basically reached the pinnacle of the convent gardener lifestyle#before poverty caught up to them#and I really wish that he'd been able to keep being a bibliophile in peace#his story always makes me so sad#even if his words and his pears make me laugh

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soult’s plundering (part 1 of ?)

As so far I have been posting all the nice and kind things about marshal Soult … uh, yes. Those were the nice and kind things! … it’s about time we address the elephant in the room: the fact that Soult was considered one of the great plunderers among the marshals, together with Masséna.

Not even Nicole Gotteri in her biography denies that Soult was constantly trying to make money for himself, though she, and I think rightfully, points out that this was true for almost all of the marshals. It just does not get adressed in most other cases. As to Soult’s methods, I have the impression that he went about it in a very different – and more prudent - manner compared to people like Masséna, Ney or Mortier, who usually just demanded contributions from occupied towns and kept some of the extorted money for themselves. Only to be severely rebuked and punished whenever Napoleon felt like playing the generous ruler and defending the oppressed.

From what I have read so far, Soult did not overtly abuse the inhabitants of conquered countries. He abused the French army administration instead.

Already in Vienna in 1805, after the battle of Austerlitz, Austrian texts repeat that the French soldiers called marshal Soult greedy and the greatest plunderer.

To be noted: The French called him that.

Artillery officer Pion des Loches relates an incident that might explain how this worked. It involves a certain general Salligny (or Saligny), who during this campaign held the position of Soult’s chief-of-staff.

Setting out alone with colonel Demarçay on 28 Brumaire (19 November) for Unterwesternitz, I witnessed one of General Salligny's masterstrokes. [...] Towards midday, we arrived in a village where there was a castle of fairly good appearance and from which we saw carriages of wine being taken out by an officer to 5th Corps.

That would be Lannes’. Uh-hum. More reason for discord.

We entered and the intendant served us dinner. No sooner had we sat down to dinner when General Salligny entered with his entire staff; he reproaches in very harsh terms the colonel for having strayed from the army corps and asks the intendant what are these carriages of wine that he has met in the village; he has them detained under the pretext that Marshal Lannes cannot requisition provisions so close to the passage of Marshal Soult's army corps; he confiscates them for us, then sells them to the intendant, and we could distinctly hear the sound of coins being counted in the next room by one of the general's aides-de-camp.

During the five days that our march from Znaïm to Austerlitz lasted, General Salligny, at the head of his staff, requisitioned victuals from all the villages near which we passed, then sold them to the authorities who had supplied them, and one day the Vandamme division ran out of bread. I heard him accuse Salligny at the head of his division and even pass the blame on to Marshal Soult.

So, I guess the procedure is clear: requisition victuals for the soldiers, then sell those goods back and pocket the money.

To be fair, I am completely at a loss as to how the distribution of victuals in the French army worked (or rather: was supposed to work, as for the most time it seems to have not worked). The army was often spread out over huge distances. What happened if one unit managed to requisition large amounts of bread, or shoes, or alcohol? They could not share their booty with their comrades easily, even if they wanted to. Would the surplus then be sold to French army suppliers by one corps, in order to be sold to other corps by those? - In all seriousness, I do not know in how far selling (some of the) requisitioned goods may even have been part of standard procedure.

Selling them to the very people you had taken them from, however, and letting the soldiers starve, clearly was not. (It should also be added that, from what I have read, Soult usually was not known to be that careless towards the soldiers under his command.)

The incident of Vandamme – who, by the way, seems to have a long history of financial misappropriations himself, so he probably knew all the tricks - publicly accusing Saligny is well-documented, too. Gotteri cites some of the letter Soult wrote to Vandamme on that occasion in her book (I can try to find it and quote it if somebody’s interested).

Needless to say that general Saligny, for the campaign of 1805, is a key figure when it comes to financial shenanigans. He also seems to have been notoriously disliked by Soult’s aides, according to Petiet. After 1805, he will leave Soult’s service and enter that of … wait for it ... Joseph Bonaparte 😁. Who clearly appreciated guys with a knack for making money at least as much as Soult did. Saligny even received a title of nobility from Joseph and would later accompany him to Spain.

---

(Continued in Part 2)

#napoleon's marshals#jean de dieu soult#napoleon's generals#charles saligny de san germano#campaign of 1805#third coalition war#marshals'n'money

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon (2023) Review

Wow, Napoleon Bonaparte must have really peed off Ridley Scott. The man evidently despises the little fella.

Plot: A look at the military commander's origins and his swift, ruthless climb to emperor, viewed through the prism of his addictive and often volatile relationship with his wife and one true love, Josephine.

So, this is the second feature film to come out this year featuring Joaquin Phoenix playing a character that really needs to cum, excuse my ironic French. The first is Beau Is Afraid, but the second is with Napoleon. Phoenix is an uber-horny little dude in this! You may have read other reviews and reactions mentioning this, and it's true - Napoleon is a surprisingly funny film, at least regarding its titular Emperor. Joaquin Phoenix really emphasizes the pathetic man-child aspect of Napoleon, and there are some great lines he says involving boats and lamb chops that are hilarious. But he is also a sex freak. Director Ridley Scott seemingly continues his streak of staging over-the-top riotous sex scenes, with recently in House of Gucci where Lady Gaga and Adam Driver do it like it's nobody's business, but now in Napoleon also where Phoenix seems to be channeling a puppy humping a chair whilst his wife played by Vanessa Kirby is as stiff as the aforementioned chair. As such, this movie ends up being a comedic gold mine at times, which is not what I would have expected going into it.

It is really gratifying to see a big-budget historical epic gracing our screens. It's rare for Hollywood these days to release a movie of this caliber, with only certain directors like Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, Denis Villeneuve, Christopher Nolan, and Scott having that reputation and freedom to receive big budgets from studios and do what they want with it. Ridley Scott seems to be the primary pioneer for continuing to make historical epics such as The Last Duel and Exodus: Gods and Kings, and I really do wish that Hollywood will continue to allow this genre to continue and give them the budget they need, as seeing these major scale battle sequences on the big screen can be so much more exciting than a CGI superhero space fight. With Napoleon, Scott again impresses with the grand scope of the battles, from the sweeping shots to the intense close-ups, with some creative imagery throughout. The stand-out sequence for me was the Austerlitz battle on ice, and it stood out from both a cinematic and narrative point. On the one hand, it is the prime showcase of Napoleon's tactical mind and his impressive skills in planning traps to defeat his enemy, and on the other hand visually when the enemy ranks are attacked by surprise cannon fire and as they start sinking through the breaking ice and drowning, the collective colour of their blood mixing with the ice and water symbolizing the image of the French flag... I mean that is pure cinema right there! That is what makes Ridley Scott stand out as a director - he is a filmmaker driven by the old school and unwilling to fall into contemporary film constraints. The common phrase "they don't make them like this anymore" is prevalent here more than ever.

That being said, Napoleon is not without its problems. For one, I'm usually the first to complain if a movie is too long, however here I find the opposite. It's a near 3 hour-long movie and yet that is hardly enough time to deliver a satisfying recollection of Napoleon's life. That right there is the issue. Napoleon's life is filled with so many fascinating moments, that any one of them, whether it be his rise to power, his chaotic relationship with his wife Josephine, his invasion of Russia, or the detrimental Battle of Waterloo, any of these could have been enough for one film to tell, yet Scott tries to tell Napoleon's entire life. With also reading that Scott is saving a 4-hour cut for the movie's streaming debut on Apple next year, you can really tell that this theatrical version is stripped down with many chunks cut out, resulting in choppy editing, and no breathing room for the narrative to have any emotional resonance. The movie feels rushed and unfinished, so I'd be interested to see how that 4-hour version next year will pan out, and if it will be a similar situation to Scott's other epic Kingdom of Heaven, where the Director's Cut is an entirely different movie to the original.

The other major issue is the characterization of the titular character. I'm not judging Phoenix's performance; he, Vanessa Kirby and the entire cast play their parts well - it is more so the way the character of Napoleon is written/treated that is the concern. Writer David Scarpa and director Ridley Scott are evidently trying to deconstruct Napoleon, yet they are unsure about how to go about it. He feels all over the place, with on one side this calm and calculated general, on the other an angry child, and finally this sex freak. They really should have focused primarily on only one of these, as instead Phoenix is forced to jump back and forth from scene to scene, and it feels like he's got some sort of multi-personality disorder. The character is very inconsistent and messy, and as such is more a caricature of the real-life figure rather than an impersonation. Vanessa Kirby's Josephine stands as the more well-written and thought-through character, yet due to the movie's rushed pace we don't get to spend nearly enough time with her, and by the end of the film she vanishes into the shadows when the writers again get stuck with what to do with her.

Napoleon is a solidly entertaining historical epic that harkens back to the old days of Hollywood. With surprising amounts of humour and also some truly incredible battle sequences, it feels cinematic and bold. Yet due to leaving too much footage on the cutting floor and a script that struggles to juggle all the real-life events as well as its titular character's layers, the movie fails at reaching the highs of Ridley Scott's other directorial efforts. Again, once the 4-hour version premieres on Apple this movie may then turn out to be a masterpiece, but until then it's simply a passable historic affair, if with some historical inaccuracies. Though don't mention that last part to Ridley Scott, he'll start having his own manchild moment again screaming "Get a life!".

Overall score: 7/10

#napoleon#napoleon 2023#napoleon movie#napoleon bonaparte#ridley scott#joaquin phoenix#napoleon review#movie#film#movie reviews#film reviews#cinema#vanessa kirby#history#drama#war#action#david scarpa#2023#2023 in film#2023 films#apple#apple original films#rupert everett#josephine de beauharnais#france#napoleon 2023 review

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

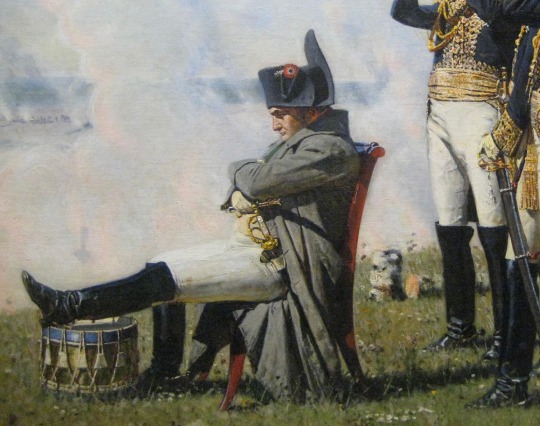

Recollections from Lejeune and Ségur on Napoleon’s uncharacteristic lack of energy, possibly a result of illness, at Borodino.

***

I was surprised that the Emperor had shown so little of the eager activity which had before so often ensured success. On the present occasion he had not mounted except to reach the battle field, and had remained seated below his Guard on a sloping mound, from which he could see everything. Several balls had passed over his head. Whenever I returned from the numerous errands on which I was sent, I found him still seated in the same attitude, following every movement with the aid of his pocket field-glass, and giving his orders with imperturbable composure. But we did not see him now, as so often before, galloping from point to point, and with his presence inspiring our troops wherever the struggle was prolonged and the issue seemed doubtful. We all agreed in wondering what had become of the eager, active commander of Marengo, Austerlitz, and elsewhere. We none of us knew that Napoleon was ill and suffering, quite unable to take a personal part in the great drama unfolded before his eyes, the sole aim of which was to add to his glory. In this terrible drama had been engaged Tartars from the confines of Asia, with the élite of the troops of some hundred European nations, for from the east and from the west, from the north and from the south, men had flocked to fight with desperate courage for or against Napoleon. The blood of some 80,000 Russians and Frenchmen had been shed to consolidate or to overturn his power, and he looked on with an appearance of absolute sang-froid at the awful vicissitudes of the terrible tragedy. We were all anything but satisfied with the way in which our leader had behaved, and passed very severe strictures on his conduct. Supper interrupted our discussion, and after it we were soon all wrapped in heavy slumber, whilst the chief, whom we had been accusing so severely, was watching and studying how best to resume the conflict the next morning.

—The Memoirs of Baron Lejeune, Vol II

***

Belliard then returned for the third time to the emperor, whose sufferings appeared to have increased. He mounted his horse with difficulty, and rode slowly along the heights of Semenowska. He found a field of battle imperfectly gained, as the enemy’s bullets, and even their musket-balls, still disputed the possession of it with us.

In the midst of these warlike noises, and the still burning ardour of Ney and Murat, he continued always in the same state, his gait desponding, and his voice languid. The sight of the Russians, however, and the noise of their continued firing, seemed again to inspire him; he went to take a nearer view of their last position, and even wished to drive them from it. But Murat, pointing to the scanty remains of our own troops, declared that it would require the guard to finish; on which, Bessières continuing to insist, as he always did, on the importance of this corps d’élite, objected “the distance the emperor was from his reinforcements; that Europe was between him and France; that it was indispensable to preserve, at least, that handful of soldiers, which was all that remained to answer for his safety.” And as it was then nearly five o’clock, Berthier added, “that it was too late; that the enemy was strengthening himself in his last position; and that it would require a sacrifice of several more thousands, without any adequate results.” Napoleon then thought of nothing but to recommend the victors to be prudent. Afterwards he returned, still at the same slow pace, to his tent, that had been erected behind that battery which was carried two days before, and in front of which he had remained ever since the morning, an almost motionless spectator of all the vicissitudes of that terrible day. (…)

After he had retired to his tent, great mental anguish was added to his previous physical dejection. He had seen the field of battle; places had spoken much more loudly than men; the victory which he had so eagerly pursued, and so dearly bought, was incomplete. Was this he who had always pushed his successes to the farthest possible limits, whom Fortune had just found cold and inactive, at a time when she was offering him her last favours? (…)

Murat then exclaimed, “That in this great day he had not recognized the genius of Napoleon!” The viceroy confessed “that he had no conception what could be the reason of the indecision which his adopted father had shown.” Ney, when he was called on for his opinion, was singularly obstinate in advising him to retreat.

Those alone who had never quitted his person, observed, that the conqueror of so many nations had been overcome by a burning fever, and above all by a fatal return of that painful malady which every violent movement, and all long and strong emotions excited in him. They then quoted the words which he himself had written in Italy fifteen years before: “Health is indispensable in war, and nothing can replace it;” and the exclamation, unfortunately prophetic, which he had uttered on the plains of Austerlitz: “Ordener is worn out. One is not always fit for war; I shall be good for six years longer, after which I must lie by.”

—General Philippe-Paul, Comte de Ségur, History Of The Expedition To Russia, Undertaken By The Emperor Napoleon, In The Year 1812

#Napoleon#Napoleon Bonaparte#Napoleonic wars#Louis-François Lejeune#Comte de Ségur#Borodino#1812#memoirs

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

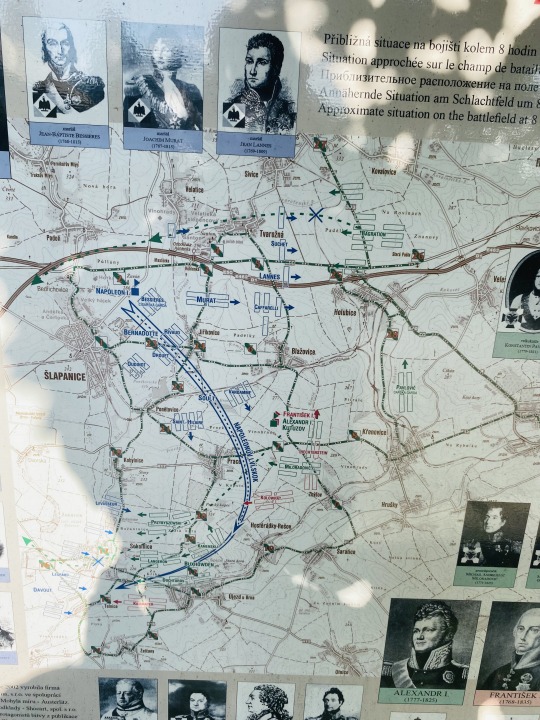

My Trip to Austerlitz (pt. 1)

The sequel to last week’s My Trip to Koniggratz! expect pictures of museums, fields, and heavy MilHist nerdery.

The battle of Austerlitz was fought near Slavkov in what is now the Czech Republic on 2 December 1805 between Napoleon’s French Grande Armée (c. 70,000 strong) and the allied forces of Russia and Austria (c. 90,000). It is generally considered Napoleon’s greatest victory.

The battlefield is big, stretching over thirteen kilometres and incorporating half-a-dozen villages. The main feature is a low ridgeline known as the Pratzen Heights, and the village of Pratzen itself, which sits at its base. There’s a museum on the heights dedicated to the battle.

Needless to say, it has the obligatory uniforms.

And the obligatory cannon. The battle is sometimes known as the battle of the three emperors after Napeoleon, the Russian Tsar Alexander, and the Austiran emperor, Francis II.

Outside is the Cairn of Peace, built in the early 20th century.

Napoleon’s army, outnumbered, had been withdrawing before the Russo-Austrian advance throughout late November 1805. Hoping to lure his enemies into a decisive battle, he deliberately abandoned a strong position on the Pratzen Heights, hoping to lure the Allies into taking it. They duly did.

Napoleon adopted a defensive stance along a stream known as the Goldbach. He deliberately weakened his right flank at the villages of Tilnitz and Sokolnitz, hoping the Allies would try and attack him there while knowing he had reinforcements marching from Vienna bound for that location.

While the Allies were lured off the heights they had first been lured onto, Napoleon would then strike at their weakened centre, taking the ridgeline.

The battle began early on 2 December with an Allied assault on the village of Tilnitz. This quickly spread to neighbouring Sokolnitz. Both locations were the scene of ferocious fighting throughout the day as they were taken and then retaken, possibly as many as five times.

These are barns in Sokolnitz that were using as strong points by both sides, and later as makeshift prisons for captured Russians.

Sokolnitz castle, another centre of the fighting in this southern sector of the battlefield. It’s now an old people’s home.

By mid-morning 3 of the 4 main Allied columns had moved down off Pratzen Heights to attack Tilnitz and Sokolnitz. The 4th was still on the heights however, as it had been disrupted by Allied cavalry who moved through it heading for the north of the battlefield.

General Kutuzov, a veteran Russian commander, didn’t want to leave Pratzen largely undefended, but the Russian Tsar, Alexander, ordered him down. Before he could, however, Napoleon struck.

This is the view from the highest point of the Pratzen heights looking out over Pratzen village towards the French centre. On the day of the battle there was a heavy fog, so it was impossible to see French forces massing for the masterstroke here.

The French advanced and, after overcoming their shock, the Allies scrambled forces to intercept and stop them seizing the ridgeline. Heavy fighting flared in Pratzen village itself, and along the slopes.

This is the view from the opposite side. Napoleon spent the morning on Zuran hill. Here we see what Napoleon would have looking towards the Allied centre on Pratzen Heights.

While all this was happening, fighting also flared in the northern sector of the battlefield, around the villages of Holubitz and Bosenitz. A ferocious cavalry engagement developed in these fields.

The deaths of an estimated 7,000 horses are commemorated here, on ground that now holds a functioning stable.

Both sides fought hard, but the French proved more adept at small-scale tactics, with proper support between infantry and cavalry, while the Allied cavalry tended to fight unsupported.

(There’s going to need to be a part 2 as I can only upload so many images to one post, thanks tumblr)

#austerlitz#battle of austerlitz#history#military history#napoleonic#napoleonic wars#19th century#napoleon

69 notes

·

View notes

Note

2 + 15 (protože jsem zvědavá!) + 4 for the history ask game?

History ask set

2. What is your country most famous for in history?

My first instinct is to say being a victim of the Munich Agreement (or being a victim in general lol) or the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich. But then I remembered the Christmas carol Good King Wenceslaus is supposedly based on Bohemian duke Saint Wenceslaus, so I'm gonna go with that.

Also the battle of Austerlitz took place in present-day Czechia and any Napoleon nerd gotta know that one.

15. Were the history classes teached in an interesting way in your school/ college/ university? What would you do to improve them if you were the teacher / lecturer?

In highschool it was a mixed bag. We had multiple teachers throughout the years. First one was focused on the dry theory, but he had good powerpoint presentations (those are always important) and iirc he liked to make interesting exam questions - like "Based on when they lived, could these two historical figures have met?" The second one loved to sprinkle in historical anecdotes (like the fact that one French prince was killed in the streets of Paris by a wild hog) and was overall a great narrator (he is a tour guide for Czech tourists in France as a second job), but I'll never forgivehim for the way he graded me on one particular exam. The last one had some great one-liners ("I've taken the first step in grading your exam papers: I found them.") and loved to add some personal stories when talking about the modern history. I was picked to dance with him on our maturita ball and he smelled of cologne and cigarettes, so that's a few points down, but overall a cool guy.

I study archivistics and medieaval latin, so pretty much all of my classes are history-ajacent. I have to highlight one of my History of Administration professors, who had a great way with words and would always spend the latter third of a class talking about a historical scandal or something from every-day life. Another cool one was my Bohemian Medieval History professor, who had a very captivating way of speaking, loved to sprinkle in some jokes and had good powerpoint presentations (yes, that is very important to me). And last but not least my Epigraphy professor was pretty much the biggest expert in his field and it showed tremendously (also for this class I got to make epigraphic descriptions of 15th century tombstones which to this day remains the coolest thing I've ever done for class).

4. My bachelor thesis is focused on 14th century charters from one monastery, so right now that's the era I think about the most. Other than that I have to go with 15th century, because that's the era my theatrical swordfighting group focuses on. Also the journal of Václav Šašek z Bířkova I read for one class was a pretty good read.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was tagged by @cadmusfly for this little ask game. It’s like 4AM in the morning here, but I can’t sleep, so this may go sideways. 😅

Last Song: Eternal Flame by Atom Music Radio

These lyrics can be generically heroic but my brain has insisted on applying it to dead heroic Frenchmen.

This flame we carry into battle

A fading memory

This light will conquer the darkness

Shining bright for all to see

We will be legendary

And from this moment on

We will not be forgotten

Our flame burns on and on

We′ll fight for all the glory, and hope that burns in all

And from the dark of the ashes, we will rise up and stand tall

Etc.

Currently Watching: Literally nothing except the dark void of my bedroom. More like, I should be watching the newest episodes of the Quantum Leap reboot and the new season of Halo. I’ll get to it eventually when my attention span returns from the war.

The last thing I watched was some reaction videos to The Expanse from Warp Reactor on YouTube. He’s got some great takes and he genuinely loves sci fi, and it amuses me endlessly. He’s going to be reacting to S1E04 soon, and it’s always fun to see how people new to the show react to that scene.

(If you've seen The Expanse, you know exactly what I mean.)

Three ships:

I’m a multishipper, so I have lots of ships in my head. At this hour of night, there’s these:

I love the sweetness of childhood friends to lovers in Murat/Bessières. There’s the angst and dysfunction potential it has towards their later years but they try anyway.

TBH, Bessières/Duroc is probably more psychologically healthy than Murat/Bessières, and I’m perfectly willing to ship them too. Duroc is very sweet and he deserves love too.

Augereau/Masséna has been on my brain a lot too, lately. These two guys are �� at minimum – morally grey on a good day, total bastards most other days. Literal partners in crime, they’re a lot of fun to just cut loose with.

There’s other ships in my head, like Booker and Nile from The Old Guard, and some OC ships in Star Trek I’d actually love to write about some day.

Favorite Color: I’m an old trad goth, so black has been a staple color for me for a very long time. But lately, as I get older, I’ve been finding that I’m – gasp – getting tired of black. I’ve been accumulating more and more accessories in pink.

Currently Consuming: Last thing eaten was some focaccia bread.

First Ship: OC/Pike from ElfQuest. It was a really long time ago and I don’t remember much about that one. The next one I remember clearly was Achilles/Patroclus. I shipped them before it was cool.

Relationship Status: I’m in a steady relationship with my cockatiel. Lately he has been trying to destroy me for getting too close to “his” nest, which is also my closet.

Last Movie: Austerlitz (1960), but I made it ⅓ of the way through before my stream crapped out on me. I’ll give it a try again later.

Currently Working On… this thing I last touched.

Tagging @scribblerinthestars, @sindirimba, @gaal-dornick, @flowwochair, @the-orion-scribe, and a whole bunch of other people whose names escape me because I should be sleeping.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I fell behind for the last four days or so and left Nikolay violently infatuated with his Tsar. Looking forward to catching up with them at the Battle of Austerlitz!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

MARSHAL SOULT

Marshal General Jean-de-Dieu Soult, 1st Duke of Dalmatia, (29th March, 1769 – 26th November, 1851) was a French general and statesman, named Marshal of the Empire in 1804, Soult was one of only six officers in French history to receive the distinction of Marshal General of France. The Duke also served three times as President of the Council of Ministers, or Prime Minister of France.

Soult played a key role as a corps commander in many of Napoleon's campaigns, most notably at Austerlitz, where his corps delivered the decisive attack that won the battle.

In May 1804, Soult was made one of the first eighteen Marshals of the Empire. He commanded a corps in the advance on Ulm, and at Austerlitz he led the decisive attack on the Allied centre.

Soult played a great part in many of the famous battles of the Grande Armée, including the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805 and the Battle of Jena in 1806. However, he was not present at the Battle of Friedland because on that same day he was capturing Königsberg.

After the conclusion of the Treaties of Tilsit, he returned to France and in 1808 was anointed by Napoleon as 1st Duke of Dalmatia (French: Duc de Dalmatie).

The awarding of this honour greatly displeased him, for he felt that his title should have been Duke of Austerlitz, a title which Napoleon had reserved for himself.

In the following year, Soult was appointed as commander of the II Corps with which Napoleon intended to conquer Spain. After winning the Battle of Gamonal, Soult was detailed by the emperor to pursue Lieutenant-General Sir John Moore's British army. At the Battle of Coruña, in which Moore was killed, Soult failed to prevent British forces escaping by sea.

Later, Soult's intrigues in the Peninsular War while occupying Portugal earned him the nickname, "King Nicolas", and while he was Napoleon's military governor of Andalusia, Soult looted 1.5 million francs worth of art. One historian called him "a plunderer in the world class."

He was defeated in his last offensives in Spain in the Battle of the Pyrenees (Sorauren) and by Freire's Spaniards at San Marcial. Soult was eventually pursued out of Spain and onto French soil, where he was maneuvered out of several positions at Nivelle, Nive, and Orthez, before the Battle of Toulouse.

Soult was also responsible for the creation of the French Foreign Legion on 9th March, 1831.

(Information From Wikipedia)

10 notes

·

View notes

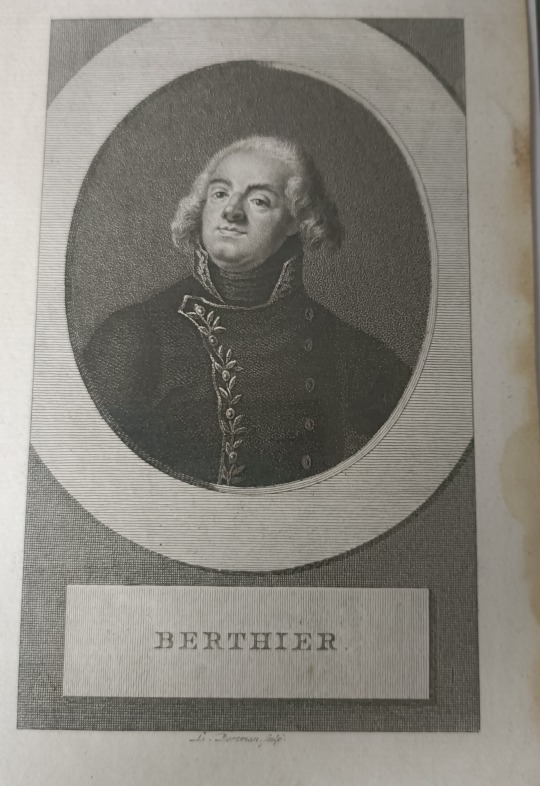

Photo

Marshal Berthier

Yesterday I found an engraving of Berthier from the Napoleonic era at an antiquariat in Amsterdam (the engraving was made by L.Portman and dates back to around 1806), I am very fortunate to have found this little piece of history so it inspired me to write a post about Berthier.

Louis-Alexandre Berthier was born on 20 November 1753 in Versailles. Berthier's father was a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Corps of Topographical Engineers, an officer, so the family somewhat led a life of nobility. Berthier was the eldest of five children, with three of his brothers also eventually joining the military. Berthier already enjoyed a career in the military before the French revolution. He was sent to North-America in 1780 and was stationed at various posts in Prussia. When the revolution started in 1789, Berthier was chief of staff of the Versailles national guard and even aided in the escape of the aunts of Louis XVI in 1791.

Being part of the 'high middle class' Berthier did not support the revolution. Nevertheless he was assigned as chief of the L'Armee du Nord but was charged with incivisme and went on inactive duty. The revolutionary years were rough as the threat of the guiliotine loomed over him but he remained a respected officer. In 1796 Berthier was made chief of staff and a general of division of the army of Italy under the command of Napoleon Bonaparte. This partnership would last until 1814, the first abdication of Napoleon.

Berthier quickly became Napoleon's most valued assistant because of his strong character and constitution. Berthier was able to work for days without sleep, was very experienced, accurate, quick and tenacious with his work. Here is a quote by Thiebault on Berthier in 1796:

"Quite apart from his specialist training as a topographical engineer, he had knowledge and experience of staff work and furthermore a remarkable grasp of everything to do with war. He had also, above all else, the gift of writing a complete order and transmitting it with the utmost speed and clarity…No one could have better suited General Bonaparte, who wanted a man capable of relieving him of all detailed work, to understand him instantly and to foresee what he would need."

After the Italy campaign, Berthier joined the Egypt campaign of 1798 and even assisted in the coup of 18 Brumaire. Berthier continued to be the chief of staff as he was also, according to some people, the only person who could read Napoleon's, often abysmal, handwriting and translate it into readable orders. You could virtually view Berthier as the operator who kept France's military machine running. If anyone thought that being the chief of staff was a relatively safe job, here is a description by officier Brossier on Berthier during the battle of Marengo in 1800:

"The General-in-Chief Berthier gave his orders with the precision of a consummate warrior, and at Marengo maintained the reputation that he so rightly acquired in Italy and in Egypt under the orders of Bonaparte. He himself was hit by a bullet in the arm. Two of his aides-de-camp, Dutaillis and La Borde, had their horses killed."

After the 1800 campaign, Berthier was employed in diplomatic business with a mission in Spain which eventually led to the Louisiana purchase. When Napoleon became emperor in 1804, Berthier was the very first one to be made a Marshal of the empire. He continued to be the chief of staff until 1814, taking part of many campaigns including the campaigns of Austerlitz, Jena, Friedland, Wagram, the Peninsular war and the infamous Russia campaign of 1812. Berthier was given the title of Prince of Wagram in 1809 and continued to serve in Germany (1813) and France (1814).

After Napoleon's first abdication in 1814, Berthier retired to his estate and made peace with king Louis XVIII, he even accompanied the king on his entry in Paris. The political situation changed drastically however when Napoleon returned to France in 1815. What exactly happened to Berthier is still a mystery to this day but on the first of june 1815, Berthier died as a result of a fall from an upstairs window. The big question remains, how and why did he fall out of a window? Some suggest that Berthier was assassinated while others suggest that Berthier suffered from PTSD as a result of the 1812 Russia campaign. The prospect of Russian troops marching to France could have literally pushed him over the edge.

Whatever the exact reason behind the fall was, the death of Berthier came as a blow to Napoleon as he later stated on St. Helena about Berthier's absence during the battle of Waterloo:

"If Berthier had been there, I would not have met this misfortune."

If you haven't watched the excellent documentary on youtube from Epic History TV about Napoleon's Marshals, Berthier has been ranked as number three in the countdown: https://youtu.be/YebUIUOCo94?t=160 (the video will give you a lot more information about the life of Berthier, definitely recommended.)

Here is a portrait by Pajou painted in 1808 and the engraving I found yesterday.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

There are honestly so many fundamental things about Ridley Scott's Napoleon I disliked, I hardly know where to start so here's just a couple things that popped into my head. All of the disappointed/angry reviews I saw really were on the money with their criticisms. Below the cut a bunch of things in no particular order

Apart from the scenes in Egypt and Elba (which are sepia-tinted) the entire movie is colorgraded with a blue-grey tone like the most painfully dreary wet day in late autumn. Just watching it I got hypothermia. Just take these two shots - the first from the 1970 waterloo movie (highly recommended, can be found for free on youtube), the second from 2023 - to see the difference.

Despite a massive budget and cgi available the battles actually felt incredibly small. The Waterloo scene in particular felt like it was taking place on a patch of grass that was a 100 meters square, with two thin lines of French infantry advancing towards a relatively small group of British infantry dispersed within a couple meters of trenches, with the tents of their camp only meters directly behind that. It gave the entire thing the sense like it was a large reenactment society of maybe 200 people giving it their all, rather than 140.000. The 1970 Waterloo might be 50 years old but showed vastly, vastly more impressive scenes of huge formations of men, offering awe-inspiring cinematography compared to Scott's tiny Waterloo skirmish. I'm perfectly willing to accept disgustingly bad historical accuracy as long as the pictures are sufficiently pretty. They were not.

As a note, in the movie the British infantry inexplicably decides to walk forwards out of their fortified trenchline on the slope (complete with spikes) and form squares in front of it, instead of simply staying inside of their trenches.

There's a fucking sniper at Waterloo. Like, an infantryman with a rifle with a scope on it. He blows a golfball-sized hole in Napoleon's hat.

The Marshals - each colorful, fascinating characters many of whom would individually be worthy of their own movie - are less than background characters; I don't think any were even mentioned by name, and there's only two or three that are regularly seen on screen. Marshal Ney, famous, brave, tragic Ney, who has a very distinctive redhead appearance, was rendered completely unrecognizable by adding a moustache.

Phoenix's Napoleon has no charismatic presence whatsoever. Anyone who wasn't already reasonably familiar with Napoleon before seeing this movie would be dumbfounded why so many people followed him at all, or why upon his return from Elba thousands of soldiers sent to stop him simply deserted to his cause as soon as he approached. If you want to create a movie to deconstruct Napoleon from a brilliant national hero to a flawed man there are infinite ways to do so, and they chose the most sub-par by just making him kinda odd and insecure.

Napoleon's military genius is underexplored if not entirely absent from the movie, and to a large extent it simply feels like events are just kinda happening to him, especially with the way short disparate scenes are quickly strung together. One second we're in the aftermath of Austerlitz (1805), and two or three 1-minute scenes we're at the invasion of Russia (1812). Some of Napoleon's finest moments as a general are omitted from the film such as the Italian campaign, Jena-Auerstedt, and the six-day campaign of 1814 where Napoleon so thoroughly outgeneralled his opponent his tiny 30K man army inflicted nearly 30K casualties on enemy forces twice his size over the course of four battles.

Meanwhile his crowning achievement at Austerlitz is reduced to yelling thrice for hidden units to attack and then the entire enemy army flees onto an ice lake fit for a fantasy movie (just check out the ice scene from the 2004 King Arthur) and gets sunk by cannon fire. If you've seen the trailer you've seen almost the entire battle.

Huge parts of the movie are devoted to his marriage to Josephine, which I personally don't find terribly interesting to begin with, and historical events are contorted to be related to his marriage (such as ditching his army in Egypt because she's cheating on him), but it often felt to me like this storyline, such as it was, was firing in certain directions only to abruptly cut them off or let them go nowhere, and the movie seemed unsure whether it was the A-plot or the B-plot or a secret third thing.

Before I forget... not once but twice Napoleon is charging into the thick of the melee on horseback!!! First where he is at the very front of a cavalry charge at Borodino (the 30 seconds of it that we got, which were all in the trailer) and second near the end of Waterloo before making a run for it. And it's so patently absurd! It's like a WW1 movie with Kaiser Wilhelm personally storming the trenches or Emperor Hirohito flying a plane at Pearl Harbor. Napoleon demonstrated plenty of bravery in his life (such as when he was wounded by a bayonet at Toulon, or attempted to lead a charge at the bridge at Arcole) but the Emperor of the French was not at the fucking forefront of a massed cavalry charge with sabre in hand scything down infantrymen.

The movie ends with a card with casualtyfigures from a bunch of battles as if it's a sobering statement at the end of a Holocaust movie, so the Brits can remind you Napoleon was actually Hitler.

#napoleon movie#I've seen bad movies in my life but I've never been so disappointed by one#I wanted it to be good. And it was the opposite.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Napoleon In A Good Humor

Volume 2: Cosette; Book 1: Waterloo; Chapter 7: Napoleon In A Good Humor

The Emperor, though ill and discommoded on horseback by a local trouble, had never been in a better humor than on that day. His impenetrability had been smiling ever since the morning. On the 18th of June, that profound soul masked by marble beamed blindly. The man who had been gloomy at Austerlitz was gay at Waterloo. The greatest favorites of destiny make mistakes. Our joys are composed of shadow. The supreme smile is God’s alone.

Ridet Cæsar, Pompeius flebit, said the legionaries of the Fulminatrix Legion. Pompey was not destined to weep on that occasion, but it is certain that Cæsar laughed. While exploring on horseback at one o’clock on the preceding night, in storm and rain, in company with Bertrand, the communes in the neighborhood of Rossomme, satisfied at the sight of the long line of the English camp-fires illuminating the whole horizon from Frischemont to Braine-l’Alleud, it had seemed to him that fate, to whom he had assigned a day on the field of Waterloo, was exact to the appointment; he stopped his horse, and remained for some time motionless, gazing at the lightning and listening to the thunder; and this fatalist was heard to cast into the darkness this mysterious saying, “We are in accord.” Napoleon was mistaken. They were no longer in accord.

He took not a moment for sleep; every instant of that night was marked by a joy for him. He traversed the line of the principal outposts, halting here and there to talk to the sentinels. At half-past two, near the wood of Hougomont, he heard the tread of a column on the march; he thought at the moment that it was a retreat on the part of Wellington. He said: “It is the rear-guard of the English getting under way for the purpose of decamping. I will take prisoners the six thousand English who have just arrived at Ostend.” He conversed expansively; he regained the animation which he had shown at his landing on the first of March, when he pointed out to the Grand-Marshal the enthusiastic peasant of the Gulf Juan, and cried, “Well, Bertrand, here is a reinforcement already!” On the night of the 17th to the 18th of June he rallied Wellington. “That little Englishman needs a lesson,” said Napoleon. The rain redoubled in violence; the thunder rolled while the Emperor was speaking.

At half-past three o’clock in the morning, he lost one illusion; officers who had been despatched to reconnoitre announced to him that the enemy was not making any movement. Nothing was stirring; not a bivouac-fire had been extinguished; the English army was asleep. The silence on earth was profound; the only noise was in the heavens. At four o’clock, a peasant was brought in to him by the scouts; this peasant had served as guide to a brigade of English cavalry, probably Vivian’s brigade, which was on its way to take up a position in the village of Ohain, at the extreme left. At five o’clock, two Belgian deserters reported to him that they had just quitted their regiment, and that the English army was ready for battle. “So much the better!” exclaimed Napoleon. “I prefer to overthrow them rather than to drive them back.”

In the morning he dismounted in the mud on the slope which forms an angle with the Plancenoit road, had a kitchen table and a peasant’s chair brought to him from the farm of Rossomme, seated himself, with a truss of straw for a carpet, and spread out on the table the chart of the battle-field, saying to Soult as he did so, “A pretty checker-board.”

In consequence of the rains during the night, the transports of provisions, embedded in the soft roads, had not been able to arrive by morning; the soldiers had had no sleep; they were wet and fasting. This did not prevent Napoleon from exclaiming cheerfully to Ney, “We have ninety chances out of a hundred.” At eight o’clock the Emperor’s breakfast was brought to him. He invited many generals to it. During breakfast, it was said that Wellington had been to a ball two nights before, in Brussels, at the Duchess of Richmond’s; and Soult, a rough man of war, with a face of an archbishop, said, “The ball takes place to-day.” The Emperor jested with Ney, who said, “Wellington will not be so simple as to wait for Your Majesty.” That was his way, however. “He was fond of jesting,” says Fleury de Chaboulon. “A merry humor was at the foundation of his character,” says Gourgaud. “He abounded in pleasantries, which were more peculiar than witty,” says Benjamin Constant. These gayeties of a giant are worthy of insistence. It was he who called his grenadiers “his grumblers”; he pinched their ears; he pulled their moustaches. “The Emperor did nothing but play pranks on us,” is the remark of one of them. During the mysterious trip from the island of Elba to France, on the 27th of February, on the open sea, the French brig of war, Le Zéphyr, having encountered the brig L’Inconstant, on which Napoleon was concealed, and having asked the news of Napoleon from L’Inconstant, the Emperor, who still wore in his hat the white and amaranthine cockade sown with bees, which he had adopted at the isle of Elba, laughingly seized the speaking-trumpet, and answered for himself, “The Emperor is well.” A man who laughs like that is on familiar terms with events. Napoleon indulged in many fits of this laughter during the breakfast at Waterloo. After breakfast he meditated for a quarter of an hour; then two generals seated themselves on the truss of straw, pen in hand and their paper on their knees, and the Emperor dictated to them the order of battle.

At nine o’clock, at the instant when the French army, ranged in echelons and set in motion in five columns, had deployed—the divisions in two lines, the artillery between the brigades, the music at their head; as they beat the march, with rolls on the drums and the blasts of trumpets, mighty, vast, joyous, a sea of casques, of sabres, and of bayonets on the horizon, the Emperor was touched, and twice exclaimed, “Magnificent! Magnificent!”

Between nine o’clock and half-past ten the whole army, incredible as it may appear, had taken up its position and ranged itself in six lines, forming, to repeat the Emperor’s expression, “the figure of six V’s.” A few moments after the formation of the battle-array, in the midst of that profound silence, like that which heralds the beginning of a storm, which precedes engagements, the Emperor tapped Haxo on the shoulder, as he beheld the three batteries of twelve-pounders, detached by his orders from the corps of Erlon, Reille, and Lobau, and destined to begin the action by taking Mont-Saint-Jean, which was situated at the intersection of the Nivelles and the Genappe roads, and said to him, “There are four and twenty handsome maids, General.”

Sure of the issue, he encouraged with a smile, as they passed before him, the company of sappers of the first corps, which he had appointed to barricade Mont-Saint-Jean as soon as the village should be carried. All this serenity had been traversed by but a single word of haughty pity; perceiving on his left, at a spot where there now stands a large tomb, those admirable Scotch Grays, with their superb horses, massing themselves, he said, “It is a pity.”

Then he mounted his horse, advanced beyond Rossomme, and selected for his post of observation a contracted elevation of turf to the right of the road from Genappe to Brussels, which was his second station during the battle. The third station, the one adopted at seven o’clock in the evening, between La Belle-Alliance and La Haie-Sainte, is formidable; it is a rather elevated knoll, which still exists, and behind which the guard was massed on a slope of the plain. Around this knoll the balls rebounded from the pavements of the road, up to Napoleon himself. As at Brienne, he had over his head the shriek of the bullets and of the heavy artillery. Mouldy cannon-balls, old sword-blades, and shapeless projectiles, eaten up with rust, were picked up at the spot where his horse’s feet stood. Scabra rubigine. A few years ago, a shell of sixty pounds, still charged, and with its fuse broken off level with the bomb, was unearthed. It was at this last post that the Emperor said to his guide, Lacoste, a hostile and terrified peasant, who was attached to the saddle of a hussar, and who turned round at every discharge of canister and tried to hide behind Napoleon: “Fool, it is shameful! You’ll get yourself killed with a ball in the back.” He who writes these lines has himself found, in the friable soil of this knoll, on turning over the sand, the remains of the neck of a bomb, disintegrated, by the oxidization of six and forty years, and old fragments of iron which parted like elder-twigs between the fingers.

Every one is aware that the variously inclined undulations of the plains, where the engagement between Napoleon and Wellington took place, are no longer what they were on June 18, 1815. By taking from this mournful field the wherewithal to make a monument to it, its real relief has been taken away, and history, disconcerted, no longer finds her bearings there. It has been disfigured for the sake of glorifying it. Wellington, when he beheld Waterloo once more, two years later, exclaimed, “They have altered my field of battle!” Where the great pyramid of earth, surmounted by the lion, rises to-day, there was a hillock which descended in an easy slope towards the Nivelles road, but which was almost an escarpment on the side of the highway to Genappe. The elevation of this escarpment can still be measured by the height of the two knolls of the two great sepulchres which enclose the road from Genappe to Brussels: one, the English tomb, is on the left; the other, the German tomb, is on the right. There is no French tomb. The whole of that plain is a sepulchre for France. Thanks to the thousands upon thousands of cartloads of earth employed in the hillock one hundred and fifty feet in height and half a mile in circumference, the plateau of Mont-Saint-Jean is now accessible by an easy slope. On the day of battle, particularly on the side of La Haie-Sainte, it was abrupt and difficult of approach. The slope there is so steep that the English cannon could not see the farm, situated in the bottom of the valley, which was the centre of the combat. On the 18th of June, 1815, the rains had still farther increased this acclivity, the mud complicated the problem of the ascent, and the men not only slipped back, but stuck fast in the mire. Along the crest of the plateau ran a sort of trench whose presence it was impossible for the distant observer to divine.

What was this trench? Let us explain. Braine-l’Alleud is a Belgian village; Ohain is another. These villages, both of them concealed in curves of the landscape, are connected by a road about a league and a half in length, which traverses the plain along its undulating level, and often enters and buries itself in the hills like a furrow, which makes a ravine of this road in some places. In 1815, as at the present day, this road cut the crest of the plateau of Mont-Saint-Jean between the two highways from Genappe and Nivelles; only, it is now on a level with the plain; it was then a hollow way. Its two slopes have been appropriated for the monumental hillock. This road was, and still is, a trench throughout the greater portion of its course; a hollow trench, sometimes a dozen feet in depth, and whose banks, being too steep, crumbled away here and there, particularly in winter, under driving rains. Accidents happened here. The road was so narrow at the Braine-l’Alleud entrance that a passer-by was crushed by a cart, as is proved by a stone cross which stands near the cemetery, and which gives the name of the dead, Monsieur Bernard Debrye, Merchant of Brussels, and the date of the accident, February, 1637.8 It was so deep on the table-land of Mont-Saint-Jean that a peasant, Mathieu Nicaise, was crushed there, in 1783, by a slide from the slope, as is stated on another stone cross, the top of which has disappeared in the process of clearing the ground, but whose overturned pedestal is still visible on the grassy slope to the left of the highway between La Haie-Sainte and the farm of Mont-Saint-Jean.

On the day of battle, this hollow road whose existence was in no way indicated, bordering the crest of Mont-Saint-Jean, a trench at the summit of the escarpment, a rut concealed in the soil, was invisible; that is to say, terrible.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le lion est malade…

In late November 1805, a short time before the battle of Austerlitz and after the Grande Armée had already marched into Moravia, Soult for some time suffered from ophtalmia that would still bother him on the day of the battle (he was wearing some sort of visor made from green taffetas in front of his eyes). But for his aides, their master’s ailment during their stay in the comfortable chateau at Austerlitz was not without advantages. As Petiet tells it:

Ever since Marshal Soult's ride across the plains of Pohrlitz and Unterwisterlitz, he had been complaining of ophthalmia, which progressively worsened and became so bad at Austerlitz that he had leeches applied to his temples and no longer left his room. The aide-de-camp on duty was to read to him all the dispatches and Lameth said to us with a laugh: "The lion is ill; that will give us some rest."

Just don't overdo the compassion, Lameth!

32 notes

·

View notes