#chanbara

Text

Zatoichi Challenged [座頭市血煙り街道] (1967)

Kenji Misumi

#zatoichi challenged#zatoichi#ichi#kenji misumi#mygifs#filmedit#gifset#chanbara#shintaro katsu#座頭市血煙り街道#samurai cinema

109 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Zatoichi TV Series

275 notes

·

View notes

Audio

At The Drive-In - Chanbara

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Demon samurai going down in a blaze of glory type beat 👺🔥

#alpha chrome yayo#synthesizer#1990s#dungeon synth#japanese folklore#samurai#jidaigeki#chanbara#shakuhachi#taishogoto#koto#samurai music

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

I cut together a music video / Bunta Sugawara fancam for my latest single

#electronic#music#synthesizer#electronic music#groove#downtempo#jidaigeki#bunta sugawara#sadao nakajima#chanbara#Youtube

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“I'm not dying yet.”

用心棒 (Yōjinbō - Yojimbo), 1961.

Dir. Akira Kurosawa | Writ. Ryūzō Kikushima, Akira Kurosawa & Hideo Oguni | DOP Kazuo Miyagawa

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recently Viewed: Death Shadows

[The following review contains MINOR SPOILERS; YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!]

The Criterion Channel’s synopsis of Hideo Gosha’s Death Shadow’s reads:

After their executions are faked by the authorities, three criminals are forced to become assassins under the command of the Shogun.

Technically, this is an accurate summary… of the film’s prologue. The actual story is significantly more convoluted—and I mean that as a compliment. The narrative is an intricately constructed puzzle that constantly reassembles, reconfigures, and recontextualizes itself; every scene introduces new characters, complications, and even entire subplots. If you ever find the subject matter objectionable or distasteful, just wait; the movie will be about something completely different within fifteen minutes.

This unconventional structure would be infuriatingly disjointed—were the central themes not so elegantly cohesive and clearly articulated. Like all of Gosha’s work in the chanbara genre, Death Shadows is staunchly antiauthoritarian, condemning any man that would abuse his power—including the secretive spymaster that “recruits” the eponymous assassins. After all, the corrupt clan officials, greedy merchants, and bloodthirsty gangsters that manipulate, exploit, and discard their subordinates deserve to be punished—but exceeding the limitations of the law in order to deliver “justice” is equally unethical (especially when this “necessary evil” is motivated by pragmatism rather than morality).

Beyond its deliberately puply premise, Death Shadows also represents the pinnacle of Gosha’s craftsmanship: this is the director’s style at its most economical, purposeful, and precise. He favors long, continuous, unbroken takes, repositioning the camera and performers to seamlessly transition from master shot to coverage (yes, this is very similar to Spielberg’s modus operandi)—a gracefully choreographed ballet that strikes a delicate balance between theatrical mise-en-scène and cinematic composition.

Gosha’s relatively restrained blocking and framing stand in stark contrast to the film’s unapologetically maximalist imagery. Much of the action unfolds on elaborately designed studio sets; hand-painted backdrops depict impressionistic sunsets and overcast skies, creating a surreal, hypnotic, dreamlike atmosphere—a dramatic departure from the grounded, gritty, naturalistic tone of the auteur’s earlier jidaigeki efforts (Three Outlaw Samurai, Sword of the Beast).

Thus, Death Shadows is a beautiful contradiction; serving as both the culmination of Gosha’s previous accomplishments in the industry and an evolution of his artistic vision, it resides comfortably at the intersection between avant-garde experimentation and popcorn entertainment.

#Death Shadows#Death Shadow#Hideo Gosha#chanbara#chambara#jidaigeki#jidai-geki#Japanese film#Japanese cinema#Criterion Channel#film#writing#movie review

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sword of the Beast / Kedamono no ken (1965, Hideo Gosha)

獣の剣 (五社英雄)

6/5/23

#Sword of the Beast#Kedamono no ken#Hideo Gosha#Mikijiro Hira#Shima Iwashita#Go Kato#Toshie Kimura#Kantaro Suga#Yoko Mihara#Kunie Tanaka#Eijiro Tono#Shigeru Amachi#60s#Japanese#drama#action#chanbara#samurai#jidaigeki#Japanese New Wave#gold#mountains#fugitives#gold prospecting#corruption#river#assassination#social commentary

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tetsuro Tanba, the hardest working man in Japanese film (it’s said he never turned down a role), as Tange Sazen in One-Eyed, One-Armed Swordsman (1963).

This film is yet another remake of The Million Ryo Pot, based on the first Tange Sazen novel (Sazen had previously appeared as a supporting - but very popular - character in another series of stories) and first filmed in 1935. This production managed to put its own spin on the oft-told tale.

The story always involves the Yagyu Clan, whose members were advisors and/or sword trainers to the shogun. This time, instead of just a guy who gets involved with the search for a valuable object belonging to the Yagyu (a sword this time, instead of a pot), Tange Sazen is revealed to be a long-lost member of the clan. No one recognizes him because of the loss of his eye and arm, and he doesn’t reveal his identity to them, preferring his life as a wandering ronin.

Tange Sazen films since 1935′s The Million Ryo Pot had a decidedly comedic side, with many of the characters mugging and playing for laughs. Ryutaro Otomo, the actor associated most with Tange Sazen after Denjiro Okochi, had played a softer, friendlier Sazen, who wasn’t afraid to get in on the fun.

Otomo-san’s long series of Tange Sazen films ended in 1962. New studio Shochiko and director Seiichiro Uchikawwa decided to try a more serious, darker tone with the character. This was a trend that was slowly taking hold of jidaigeki and chanbara films, and would continue throughout the decade. This isn’t to say there isn’t any humor, or that Tange Sazen is any less the heroic figure he has always been. However, the film is definitely a more dramatic turn for the series.

Tanba-san also provides a physically different appearance to Tange Sazen. The character had always been presented as having lost his right eye and arm; Tanba-san’s Sazen is missing his left eye and arm. There are theories regarding why this was done, from using the change to show filmgoers that this was a different Tange Sazen than they were used to seeing, to it being too difficult or production not having enough time to train Tanba-san to use his left arm for sword fighting (a skill he wasn’t known for).

This was not Tanba-san’s first time playing Tange Sazen. He had played the role for one season of a television series that ran from 1958 to 1959 on NTV. I have found very little information on that series. I assume, however, since it ran while Otomo-san’s films were being released, that Tanba-san portrayed a more traditional Tange Sazen - comedic and missing the right eye and arm.

One-Eyed, One-Armed Swordsman ended like a Zatoichi film, with our hero hitting the road after the climatic battle. This was definitely leaving the door open for a sequel (or sequels), but they never manifested.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

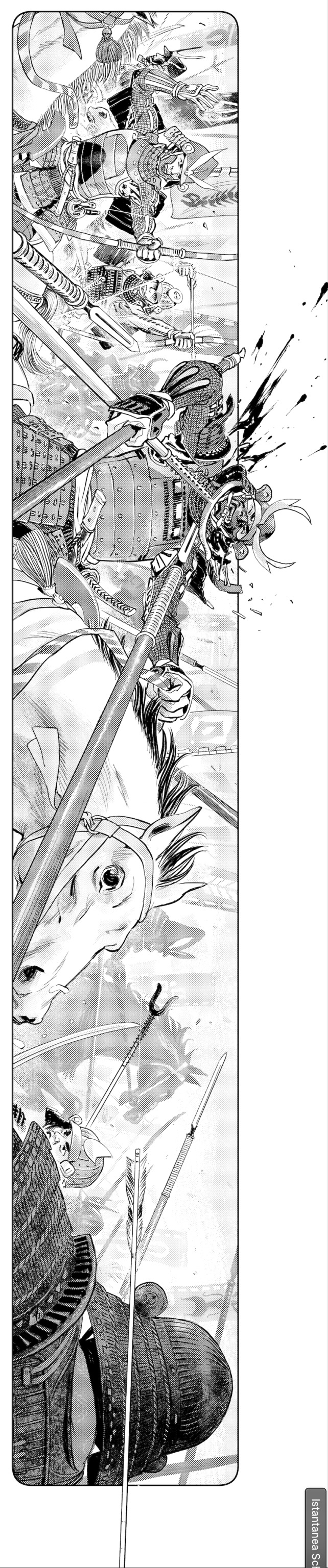

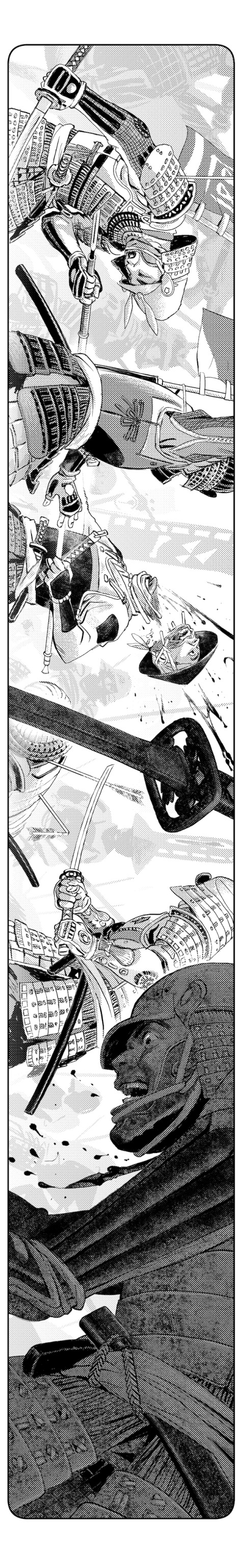

Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart in the Land of Demons (1973)

Kenji Misumi

389 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Zatoichi TV Series

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Made a new song and music video

youtube

#electronic#music#synthesizer#electronic music#youtube#groove#chanbara#jidaigeki#chambara#red peony gambler#hibotan bakuto#junko fuji

0 notes