#duc de nemours

Photo

Charles Philippe d’Orléans, Duc de Nemours (1905-1970).

#royaume de france#maison d'orleans#bourbon orleans#maison d'orléans#duc de nemours#nemours#charles philippe d'orléans

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anne of Austria and Mazarin: a more nuanced reading.

The question of the queen mother’s relationship with Mazarin has been the stuff of historical speculation since the mazarinades first spread notions of illicit sexual relations, secret marriage, and the cardinal’s ‘bewitching’ of the queen. Since then, slightly more decorous historical discussion has sought to establish the nature of the relationship, with the obvious underlying question of how emotionally dependent Anne was on Mazarin. Much of this relies on reading meanings into letters from Mazarin to Anne whose tone and expression could encompass the possibilities of frustrated physical passion, heightened seventeenth-century notions of sentiment and friendship, calculated emotional manipulation, and a great deal in between these three. The relevant question in this context is whether the queen mother could contemplate abandoning Mazarin and leaving him in permanent exile, either because the emotional ties were less strong than Mazarin wished to believe, or because Anne calculated, on behalf of her son, that the political price —or political risk— of restoring the cardinal was too high. Here the only real source, given the queen’s own silence, are the memoirs of contemporaries around her at court, and opinions in these are divided. If some of these writers assert that Anne would never abandon Mazarin, others were quite prepared to argue that the queen’s affections were conditional and perceptibly diminishing as Mazarin’s absence continued. A third group did not doubt Anne’s affection for the cardinal, but were more sceptical of her resolution and commitment to him in the face of persuasion and contrary arguments advanced by those in her entourage and in the council.

Some of the shrewdest commentary can be found in the memoirs of Marie d’Orléans, duchesse de Nemours, who was not an intimate of Anne like Mme de Motteville, but no enemy of the queen either. Nemours’ memoirs assert that commentators had been so obsessed with the notion that the queen was entirely controlled by Mazarin that they had failed to note just how little correspondence there was between the two of them, and the amount of mutual misunderstanding that grew up during Mazarin’s exile. The queen mother, she argued, had little taste for the work of government and little confidence that she could handle it well; despite this, Nemours adds, she had a good sense of political judgement based on scepticism about the motives of everyone. So it suited the queen to allow Mazarin to take responsibility for government, but when he was not present she was prepared to take the advice of others around her, even when this cut across the actions and policies that she had previously agreed with the cardinal. This interpretation of the queen’s motivation was not good news for Mazarin’s aim to shape Anne’s actions on the basis of his intermittent correspondence. And it was echoed by two of Mazarin’s strongest advocates at court: his nephew by marriage, the duc de Mercoeur, and his military ally, the maréchal du Plessis-Praslin. Both stressed that the queen was, in Mercoeur’s words, ‘susceptible to being pressured’ by those ministers and courtiers with whom she was more immediately in contact.

These pessimistic judgements were not fully accepted by Mazarin, but he was certainly concerned that Anne might get used to managing affairs of state without him. It was not possible to insulate the queen mother from those around her, and many of them were either his undeclared enemies or those who believed that Mazarin’s return would complicate an already precarious political situation. His response, as we have seen, was to keep his return as the unremitting focus of all his letters, while simultaneously expecting his allies and appointees in the council and at court to maintain the pressure on the queen by stressing the miseries of his exile and the benefits that would be brought by his presence.

All of this took its toll: Mazarin was prepared to confront the queen directly about the extent of her commitment to him, and his replies suggest that he received some written reassurances from Anne in return. But he was no less aware that even the most detailed and painstakingly written account of the political situation and the role she should play was less immediately influential than direct conversation with the queen. Unless he could count on those around Anne to remain ‘on message’, his letters could easily be forgotten; and many of these courtiers saw Mazarin’s stock as having fallen to the point where his concerns could be ignored with impunity. An additional hazard in trying to build up a group of cheerleaders around the queen came from Anne’s suspicions that Mazarin’s letters to others in the court circle may have offered different perspectives and information from those sent to her personally. The duc de Mercoeur explained in a letter to Mazarin that the queen insisted that all those at the court who received letters from Mazarin should read them out to her in her apartments. Mercoeur recognized that this had the potential to embarrass Mazarin, if not worse, and suggested that the cardinal should send information that he did not want disclosed to the queen in separate, additional notes that could be kept apart from the letter for public consumption.

David Parrott - 1652: The Cardinal, the Prince, and the Crisis of the Fronde

#xvii#david parrott#1652: the cardinal the prince and the crisis of the fronde#cardinal mazarin#anne d'autriche#marie d'orléans#madame de motteville#duc de mercoeur#maréchal du plessis-praslin

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On to 1845 -

Top: 1845 Vicomtesse Othenin d'Haussonville, née Louise-Albertine de Broglie by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (Frick Collection - New York City, New York, USA). From Wikimedia 4639X6500 @72 7Mj.

Second row left: 1845 Ekaterini Botzaris Caradja painted by Pietro Luchini (location ?). From Wikimedia; expanded to fit screen 1078XZ1400 @72 495kj.

Second row right: 1845 Henrietta Baillie (d.1856) by Margaret Sarah Carpenter (Royal College of Physicians - London, UK). From centuriespast.tumblr.com/post/178198887928/henrietta-baillie-d1856-margaret-sarah 984X1200 @72 188kj.

Third row: 1845 Prinzessin Auguste Ferdinande von Bayern, Erzherzogin von Österreich-Toskana by Joseph Karl Stieler (auctioned by Neumeister). From their Web site. removed spots & fixed one flaw with Photoshop 2782X3307 @300 1.1Mj.

Fourth row left: 1845 Emilia Karlovna Musina-Pushkina by Vladimir Ivanovich Hau (location ?) 3304X4112 @600 3.3Mj.

Fourth row right: 1845 Anna von Minarelli-Fitzgerald by Anton Einsle (National Gallery of Ireland - Dublin, Ireland). From their Web site; fixed obvious spots & flaws w Pshop 1987X2480 @300 2Mj.

Fifth row: 1845 Queen Marie-Amelie with the duc de Nemours' two sons by Franz Xaver Winterhalter (location ?). From the lost gallery's photostream on flickr 1346X2000 @180 872kj.

Sixth row left: 1845 Louise von Wertheimstein (Vienna 1813-1890), born Biedermann by Anton Einsle (location ?). From pinterest.se/bjornolofkihlbe/art-austrian-artists/anton-einsle/ 3445X4512@300 3.7Mj.

Sixth row right: ca. 1845-1850 Baronne X. Amazone en chapeau by Alfred de Dreux (Jean-François Heim - Basel, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland). From their Web site 1866X2493 @72 1.4Mj.

Bottom: 1844-1845 E. I. Ton by Alexey Vasilievich Tyranov (location ?). From deligent.livejournal.com/22455885.html; fixed cracks w Pshop 1000X1242 @120 339kj.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“ Jacques de Savoie, Duc de Nemours, c.1560-8.”

British Museum.

From Twitter.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The other day I had an ask about Sophie's marriage to Ferdinand d'Orléans. In the answer I quoted a fragment of an account of the wedding by Prince Hohenlohe-Schilling, which in turn was quoted in Erika Bestenreiner's book about Elisabeth and her siblings. Well I should have digged a bit deeper because it turns out that the Prince's memoirs from which said quote comes from had been translated to English, so we actually have his full account of the celebrations. You can read the whole thing here, which includes tons of biased descriptions of several of the royal guests, but also really bad smell in your guest room, someone looking at you like if you were a scorpion and a mediocre perfomance of one of Verdi's operas during Mass.

STARNBERG, September 28, 1868.

In obedience to the Royal command I came to this place to attend, as Minister of the Household, the marriage of the Duchess Sophie with the Duc d'Alençon, son of the Duc de Nemours. Prince Adalbert and Minister Pfretzschner were appointed to act as witnesses. As the latter preferred to spend the night at Starnberg, I decided to leave yesterday afternoon at half-past two. We arrived at four o'clock, took possession of our rooms at the Hotel am See, and then took a walk, dined at five o'clock and then went down again to the shore of the lake in hopes of seeing something of the illuminations which were to take place nominally in honour of the Czarina of Russia then staying at Berg. But it was nine o'clock, and as nothing happened we preferred not to wait about any longer, and soon got to bed. The fireworks and illuminations would seem to have been very fine, but very little could be seen here. It was Sunday, and consequently a numerous and beery contingent of the general public had taken post under our windows, and kept up a horrible din and shouting. At intervals they sang ''popular airs," but these almost immediately degenerated into mere brutish yells. However, I soon fell asleep, especially as a wholesome storm of rain dispersed the gang. This morning I went to the railway station to see the Empress of Russia depart. Tauffkirchen* was there too, to pay his respects to the Empress. The King accompanied the Empress and travelled some distance with her on the railway in the direction of Munich, but I do not know how far.

At ten we drove over to Possenhofen in my carriage, which I had had brought here yesterday. It was not eleven o'clock yet, so we were taken first to our rooms. In mine there was a villainous bad smell. Soon the time for the wedding ceremony arrived, which took place in a hall of the Castle transformed into a chapel. The guests assembled in the adjoining salon, where a grand piano further blocked the scanty space available. Pfretzschner and I hastened to get ourselves presented to all personages of rank. Besides the family of the Duke Max, Prince Adalbert and Prince Karl were there. The latter bowed to me across the room with a look such as one generally bestows upon a scorpion. Then Count and Countess Trani. The Hereditary Princess Taxis wore a mauve or violet dress trimmed with white. Others present were the Comte de Paris and his brother, the Duc de Chartres, two young and well-built princes, but who give the impression rather of Prussian than of French princes. The Duc de Nemours looked like a French dandy from the Cercle de l'Union. He wore the Order of St. Hubert, as did his son, the bridegroom. The Duc de Nemours recalls the portraits of Henri IV., yet he has a certain look of his own that makes you set him down as a pedant. The young Duc d'Alençon is a handsome young man of a fresh countenance. The Prince de Joinville and his son, the Duc de Penthièvre, have nothing very striking about them. The former is old-looking and bent, too old-looking for his age, dignified and courtly. The Duc de Penthièvre has a yellow, rather Jewish face, and speaks with a drawl, but was very kind and friendly to me. Duke August of Coburg is as tedious as ever. I was interested to become acquainted with his wife, the Princess Clementine, a clever, lively woman. The Princess Joinville, a Brazilian Princess, is rather mummified, with big rolling eyes in a long, pale, wrinkled face. Then there were two daughters of Nemours there too, one grown up, the other a little girl. The ladies were all in "high dresses." The bride in white silk, trimmed with orange blossom, with head-dress of orange blossom and a tulle veil. On the sleeves braids of satin, after the pattern of the Lifeguardsmen's stripes. A lady-in-waiting attached to the Nemours party wore a flame-coloured silk with straw-coloured trimmings. When all were assembled, we proceeded to the chapel. The bridal couple knelt before the altar. Behind them, on the left, Prince Adalbert, behind him we two Ministers, and then behind us the gentlemen of the House of Orleans. On the other side the Duc de Nemours and the Duchess, likewise all the Princesses. Hancberg began the ceremony with a suitable address. Nobody cried, but Duke Max looked rather like it once or twice. The bride appeared extremely self-possessed. Before the "affirmation" the bridegroom first made a bow to his father, and the bride did the same to her parents. The Duchess's "Yes" sounded very much as if she meant "Yes, for my own part," or "For aught I care." I don't wish to be spiteful, but it sounded like that to me. After the wedding, I kissed the Duchess's hand, and congratulated her. She seemed highly gratified and pleased. The pause between the wedding ceremony and the State dinner we spent in our room. I forgot, by-the-by, to say that during the Mass a military band played an accompaniment to the religious ceremony. It began with the overture to one of Verdi's operas, I don't know whether it was Traviata or Trovatore. It was but a mediocre performance, the sort of stuff you hear played at dinners.

The State dinner was held downstairs in two halls. In one sat all Royal personages and myself along with Pfretzchner, in the other the courtiers. The health of the bridal pair was drunk without speechmaking. I sat between the young Princess of Coburg and Duke Ludwig. The dinner was not particularly long, nor was it particularly good either. On rising from table there was some more standing about, and then all the company separated. The Orleans Princes took their departure at once, about half-past four, as did the other Princes. Only the Duc de Nemours stays on till the day after tomorrow with his children.

We drove back to Starnberg in one of the Ducal carriages, from whence we return to-day to Munich by the eight o'clock train.

At dinner the "Wedding Chorus" from Lohengrin was played. It must have been singularly agreeable to the King's ex-fiancée. Another odd coincidence was that the very evening before, the lake and mountains were illuminated (for the Czarina), and the King had to celebrate in this way his erstwhile fiancée's bridal eve.

The Comte de Paris spoke to me about war and peace, and maintains that popular feeling in France is opposed to war. But he said it was difficult to gauge public opinion in France, the Press is so wanting in independence.

He is a sensible, well-meaning man, who would make an excellent Constitutional King of France.

*Count Tauffkirchen was at that time Bavarian Minister at St Petersburg.

#chlodwig prince of hohenlohe-schilling#sophie in bavaria duchesse d'alençon#ferdinand d'orléans duke of alençon#prince louis d'orléans duke of nemours#and many more!#memoirs of prince chlowdig of hohenlohe-schillingsfuerst#house of wittelsbach#house of orléans

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

-THE COUSINS; QUEEN VICTORIA AND VICTOIRE, DUCHESS DE NEMOURS, BY FRANZ XAVER WINTERHALTER 1852- . Victoire, duchesse de Nemours (1822-1857), was first cousin to both the Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, the daughter of their uncle, Prince Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg. A childhood playmate of Prince Albert at Rosenau, Victoire was described by Queen Victoria as ‘like a dear sister to us’ (Benson and Esher 1908). She married Louis, duc de Nemours, second son of the King of France, in April 1840, only two months after the royal wedding in England. Eight years later she was forced into exile with the rest of the French royal family by the Revolution of 1848, living at Claremont House in Surrey. The Duchess was a frequent visitor to Buckingham Palace and it was there that ‘secret’ sittings took place for The Cousins: ‘Dear Victoire & Nemours came to luncheon, & remained til after 3, Vic sat to Winterhalter for the secret’ (Journal, 29 June, 1852). The sitters occupy a two seater ‘tête-a-tête’, in the style of Georges Jacob but not recognisably from the Royal Collection. The background landscape with hills and a river may be imaginary. Queen Victoria wrote that Prince Albert was ‘greatly pleased’ with the painting (Journal, 26 August, 1852). The duchesse de Nemours died in 1857 at Claremont at the age of thirty-five, after giving birth to her fourth child, Blanche. Soon after, Queen Victoria compiled a commemorative album which included a watercolour of the Duchess on her deathbed. She also commissioned three additional copies of The Cousins from William Corden, and a bust of Victoire from Marochetti. The Queen wrote of her cousin, ‘She was so dear, so good – one of those pure, virtuous, unobtrusive characters who make a home peaceful, cheerful and happy’. The picture was hung in the Queen’s Bedroom at Osborne. ______________________________ . Source : #royalcollectiontrust ______________________________ #queenvictoria #queen #victoria #victoire #duchessdenemours #royals #victorian #painting #cousins #victorianera #victoriaandalbert https://www.instagram.com/p/Cd6dQwTsR3f/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#royalcollectiontrust#queenvictoria#queen#victoria#victoire#duchessdenemours#royals#victorian#painting#cousins#victorianera#victoriaandalbert

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Henri II de Savoie, duc de Nemours. . Credit line: Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1953 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/393124

#aesthetic#art#abstract art#art museum#art history#The Metropolitan Museum of Art#museum#museum photography#museum aesthetic#dark academia

0 notes

Quote

The most severe critics of Henri III believed that they found evidence of his marginal tastes on the foundation of two passages from the journal of L'Estoile who alluded to his disguises:

-- Late September 1576 in Paris: 'Meanwhile, the king ran the carrousel [horse ballet] dressed as an Amazon, and did so during each new banquet.'

--February 1577 in Blois: 'Meanwhile, the king held tournaments, jousts, and ballets and many masquerades where he normally dressed as a woman, opened his doublet and uncovered his throat, wearing a pearl necklace and three linen collars, two ruffled and one folded over, like the ladies of the court wear.'

Despite malicious intent, L'Estoile well specified that these were fanciful tournaments and masquerade balls, both involving the wearing of costumes. Gentlemen of the court with perfectly orthodox love lives wore the same disguises, very en vogue during the time of the last Valois. Under François II, during a carrousel organized at the Château d'Amboise, the Grand Prior of France (a Guise) took part in this exercise dressed as an Egyptian woman, carrying a swaddled monkey disguised as a newborn. The Duc de Nemours (who served a century later as the model of the seducer in La Princesse de Clèves by Mme. de Lafayette) fought while dressed as a bourgeoise with a bougeoise's coiffure, a bunch of keys at his waist. The costume of the Amazon, symbol of chastity and courage, was very appreciated at court and the painter Antoine Caron produced a scene of a game of darts where the participants wore it. During the festivities at Bayonne (1565) at the occasion of a meeting between the young Queen of Spain Élisabeth de Valois and her family, the young Henri III, then fourteen years old and only obeying the will of his mother, participated in a fantasy combat with a troupe of young men dressed as Amazons, as the Duc de Nemours directed another troupe of knights disguised as women. As such, the habitual recordings made about the last Valois must be interpreted in light of the practices of the society of his time.

- Jacqueline Boucher, La cour de Henri III (p. 25-26)

#quotes#henri iii#valois#cross-dressing#court festivities#court life#myth busting#pierre de l'estoile#duc de nemours#françois de guise grand prior of france#guise#antoine caron#16th century#renaissance#french history#jacqueline boucher#la cour de henri iii#queue

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

And the last chara designs for La princesse de Clèves !

Here are Marie Stuart, le Duc de Nemours, and le Duc de Guise.

#Duc de Nemours#Duc de Guise#Marie Stuart#La Princesse de Clèves#Character Design#Character#Design#Illustration#Animation#madame de la fayette

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Louis-Philippe, accompagné de ses fils, sortant à cheval du Château de Versailles, par Horace Vernet, 1846

Château de Versailles

#Peinture#Louis-Philippe d'Orléans#Louis-Philippe I#Louis Philippe Ie#Louis Philippe#Ferdinand d'Orléans#Louis d'Orléans#François d'Orléans#Henri d'Orléans#Antoine d'Orléans#Roi des Français#Duc d'Orléans#Duc de Nemours#Prince de Joinville#Duc d'Aumale#Duc de Montpensier#1846#1840s#Monarchie de Juillet#19e siècle#xix century#France#Château de Versailles

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Prince Charles-Philippe of Orléans, Duc de Nemours.

#royaume de france#maison d'orleans#bourbon orleans#maison d'orléans#prince philippe d'orléans#duc de nemours#nemours#charles philippe d'orléans

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Princesse de Clèves, 4

La Princesse de Clèves, 4

Madame de La Fayette,gravure de 1840 d’après Desrochers.

We know the immediate historical background of the Princesse de Clèves, and I have suggested intertextuality. Marguerite de Navarre’s L’Heptaméron features intrigues and disloyalty at court. But the discourse on love takes us back to the ancient Roman poet Ovid’s Ars Amatoria, and it may have antecedents, such as extremely distant…

View On WordPress

#amour fatal#Background#Diane de Poitiers#Henri II#jealousy#La Princesse de Clèves#Le Duc de Nemours#Le Prince de Clèves

0 notes

Photo

A gold bracelet with a miniature portrait of Louis, duc de Nemours, originally from the collection of his wife, Victoria of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Unknown artist, circa 1845. [credit: Mallié-Arcelin, via Auction.fr]

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

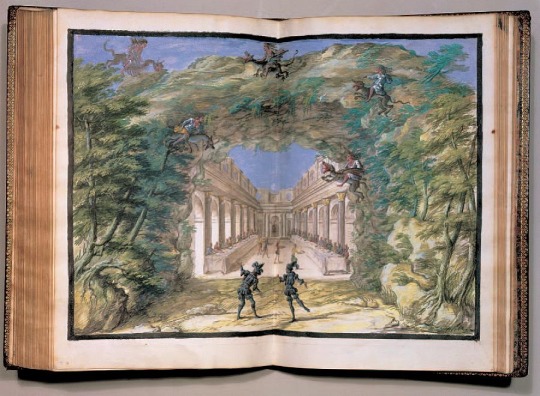

LE BALLET ROYAL DE LA NUIT

To mark the defeat of the Fronde, on 23 February 1653, a masque-like spectacle of dance and music was staged in the Salle du Petit-Bourbon in the Louvre in honor of the Queen regent, Anne d'Autriche, and her first minister, Cardinal Mazarin. Entitled the Ballet Royal de la Nuit, the piece was an epic, all-night production, commencing at 6:00 PM and concluding 13 hours later at 6:00 AM. Divided into four "watches," the performance comprised 45 entrées réparties, 3 ballets-within-the-ballet, numerous airs, and theatrical sketches. The 15-yr old Louis XIV, an accomplished dancer, appeared as several characters, including Le Sol Levant. When a paper backdrop caught fire during his performance, the young king kept calm to avert an audience panic, thus allowing the ballet to continue to its end. The ballet was performed 7 times over two weeks, and was revived several times in the later 17th and 18th centuries.

The subject and overall form of the ballet was conceived by Le Sieur Clément, intendant of the duc de Nemours. The concept called for the representation of gods and goddesses, allegorical figures, "low" scenes of gypsies, thieves, and peasants, and such "horreurs" as witches, werewolves and demons performing a Black Mass. The court poet Isaac de Bensérade wrote the texts, which were set to music by Jean de Cambefort, Jean-Baptiste Boësset, Michel Lambert and Louis de Mollier. The choreography, which is preserved in an early form of dance notation, is attributed to Mollier. The set designs by Italian scenographer Giacomo Torelli were engraved by Cochin and published in a lavish livre de fête. Drawings by Henri de Gissy made for a 1662 reprise of the ballet, record the original costumes designs.

Despite its arduous length and highly-artificial content, the Ballet Royal de la Nuit continues to be staged by modern dance companies.

158 notes

·

View notes

Photo

History Meme || 6 Objects/Organizations

↬ Twelve Peers of France

I. Archevêque-duc de Reims

• First: Guillaume de Champagne (1135 – 1202; r. 1200–1202)

• Last: Alexandre Angélique de Talleyrand-Périgord (1736 – 1821; r. 1777–1790)

II. Évêque-duc de Langres

• First: Gauthier de Bourgogne (fl. 12th century; r. 1179–1180)

• Last: César-Guillaume de La Luzerne (1738–1821; r. 1770–1790)

III. Évêque-duc de Laon

• First: Roger Rozoy (d. 1207; r. 1200–1207)

• Last: Louis Hector Honoré Maxime de Sabran (1739 – 1811; 1777–1790)

IV: Évêque-comte de Beauvais

• First: Philippe de Dreux (c. 1158– 1217; r. 1200–1217)

• Last: François-Joseph de La Rochefoucauld-Bayers (1727 – 1792; r. 1772–1790)

V. Évêque-comte de Châlons

• First: Rotrou du Perche (d. 1207; r. 1190–1200)

• Last: Anne-Antoine-Jules de Clermont-Tonnerre (1748 – 1830; r. 1781–1790)

VI. Évêque-comte de Noyons

• First: Étienne de Villebéon de Nemours (d. 1221; r. 1200–1221)

• Last: Louis-André de Grimaldi de Cagnes (1736 – 1808; r. 1777–1790)

VII. Duc de Normandie

• First: Rollon de Normandie, comte de Rouen (860 –930; r. 911—927)

• Last: Charles de France (1446 – 1472; r. 1465–1469)

VIII. Duc d’Aquitaine

• First: Ramnulf Ier, comte de Poitiers (d. 866; r. 854–866)

• Last: Charles de France (1446 – 1472; r. 1469–1472)

IX. Duc de Bourgogne

• First: Robert Ier, duc de Bourgogne (1011 – 1076; r. 1032–1076)

• Last: Charles “le Téméraire”, duc de Bourgogne (1433 – 1477; r. 1467–1477)

X. Comte de Flandre

• First: Baudouin Ier, marquis de Flandre (d. 879; r. 863–879)

• Last: Holy Roman Emperor Karl V (1500 – 1558; r. 1506–1526)

XI. Comte de Champagne

• First: Thibaut Ier, comte de Blois (913 – 975; r. 917–975)

• Last: Jehanne II de Navarre (1311 – 1349; r. 1316–1318)

XII. Comte de Toulouse

• First: Raimond Ier, comte de Toulouse (d. 865; r. 852–865)

• Last: Jehanne, comtesse de Toulouse (1220 – 1271; r. 1249–1271)

58 notes

·

View notes