#fallout analysis

Text

Norm is absolutely one of my favourite characters in the Fallout universe. The fact he loves his family and wants what's best for them being what drives him to look for the truth of what has happened to them and why is fantastic. The ultimate difference between him and Chet, too, is a great show of his character. It began with him choosing to help his sister find their father and ends with him coming to the same realisation as she has – their father was not the man he said he was and much of their life has been a lie. Watching him decide to take the hunt for the truth into his own hands, even when it could be the end of him, is incredibly compelling.

What makes Norm so enjoyable to watch, too, is just how human he is. All of the characters in the show are that way, which is part of what makes it great (yes, even the ghouls as they were at one time human). The distress he feels at seeing what happened to Vault 32 being swept under the rug, and the anger he feels towards Betty and the others for doing it seemingly out of a desire for control and power more than anything else is tangible. The fact it drives him to take the risk of sneaking into Vault 31 shows his bold and couregous side, and also that it's driven by not only his own curiosities but his desire for the truth. It’s a great parallel trait he shares with Lucy and, as she comes to find out, their mother. The anger he feels towards his father and also the desperation he feels to survive are a great contrast of his truth seeking and his baser humanity.

All things considered, Norm's competing feelings of a desire for truth, a desire for safety, curiosity, and a love for his family are what make him a great character. The fact he shares those traits with Lucy but expresses them in different ways creates a strong parallel narrative for their characters, and also does a great job showing the two sides of courage. The fact neither he or Lucy are impervious or shy away from moments of weakness and subsiming emotion latch onto the naivety from their upbringing and also their humanity. With them both now having to reckon with the truth about their father, a reunion between them will I'm sure be great and also remind them that not all of their family members are bad. Reckoning with the truth about their mother and Lucy's love for her being what compelled her to end her suffering before breaking down at the gravity of it is another layer of complexity to their family dynamics that both of them will need time to sit with. The contrasting feelings of how they knew their father versus what they've come to learn about him serve well to separate them from others like Chet; where he, their cousin, chooses to remain wilfully ignorant, they chose to put aside their fears and look for a truth they knew was out there.

Chet is a coward because he chooses to ignore the truth he has seen with his own eyes.

Lucy is brave because she is willing to go to any and all lengths to find her father and is then willing to end the suffering her mother is under because of him; she is openly emotional and driven by that and the love she feels for her family and is horrified and shattered by her father being a different man than the one she had always known.

Norm is brave because he is willing to do anything for his sister and father and, when faced with the choice to stay in blissful ignorance, because he chooses to seek out the truth even when it could hurt him; he, too, doesn't shy away from the pain the truth about his father causes him and, like Lucy, has to learn to live with the competing memories of their father and the reality of who and what he is.

Hank is a coward because, while he goes to the extremes to attempt to preserve himself and his family, he refuses to accept the fact his actions have consequences for the way his children (and, previously, their mother) had seen him and instead tries to force things to go back to the way they were before his children could learn of his ability to be selfish.

And Rose was brave because she loved her children so much that she would and did do everything for them, even when she had to put her love for their father aside and risk herself so that she and her children could have a chance to live in truth rather than lies. Her children share that with her, even though they didn't know it, just as much as they share her love, empathy, and desire for the truth even when living in wilful ignorance could have been easier.

Tl;dr – the entire MacLean family being driven by love for each other but expressing it in different ways that ultimately drive them apart is not only great at showcasing the different sides of courage and cowardice but showing the way Lucy and Norm are so similar and are driven by their love for their family just as much as their desire for the truth and that neither Lucy or Norm shy away from their emotional and impulsive reactions to it presents them as not only fully human but two sides of the same coin; they are both couregous even though they take two different paths to the truth.

#fallout#fallout on prime#fallout prime#fallout tv#fallout tv show#fallout tv series#fallout tv spoilers#fotv spoilers#fotv#lucy mclean#lucy maclean#norm maclean#hank maclean#rose maclean#chet maclean#lucy fallout#norm fallout#fallout analysis#fallout stuff#fallout show#fallout spoilers#fallout series#fallout things#fallout the series#fallout the show#fallout thoughts

155 notes

·

View notes

Text

One interesting thing about Caesar which I basically never see anybody talk about, right, is that his father was killed by raiders. I understand why nobody talks about it, because he's the world's biggest asshole, and the game itself only addresses it in a blink-and-you'll-miss-it line. But it's notable to me because it's basically the textbook example of a Freudian excuse, and in a lesser game likely would have been played up as such. His father gets killed by raiders in the NCR heartland, and fifty years later he's built an empire standing opposite the NCR that's noted for having basically eliminated raiding as a concept within its borders (part-and-parcel with the rest of the oppression.)

This is never directly presented as a contributing factor to Why He's Like That. It isn't presented as the fulfilment of some oath he swore on his murdered father's grave. In fact, it's almost the inverse- you only find out about this when he briefly mentions it as part of the extremely curated, self-aggrandizing backstory that he's giving you as part of an extended sales pitch. It's a curt mention- something that happened, an explanatory factor in how he and his mother wound up in the care of the Followers. A figure he has to account for in telling you his life story, because as an outsider you aren't going to fall for the "Son of Mars" routine. But not something terribly important besides that. Not something with a place in the mythology. Definitely not a loss or absence that's meaningfully impacted him in any way going forward, because the Mighty Caeser is of course totally above such petty concerns.

That digression aside, the point is this- it's comically easy to imagine the version of this story that leveraged these exact backstory details, unchanged, to paint a picture of Caesar as a brooding antihero, making the both-sidesing rampant in the fandom textual. There's probably some Conan-style grim-and-gritty sword-and-sorcery rise-of-a-king epics out there you could seamlessly slot him in as the protagonist of (the man himself reads Grognak comics.) There are the bones of an unironic self-satisfied ultramasculine power fantasy rattling around in there, the shrewd modern man who uses strength, guile and modernity to dominate his lessers, a hard-man-making-hard-choices, the whole process a masturbatory tract in favor of whatever ideology the infallible Great Man Protagonist chooses to embody. This is a kind of story, in science fiction, more often than not a grotesque one. And it's clearly the kind of story Caeser thinks he's the protagonist of. But Hank Morgan this fucker is not. And I'm intensely grateful that the narrative refuses to let him get away with pretending that he is. At the end of the day his army is wearing football gear.

#fallout#fallouot new vegas#fallout caesar#edward sallow#fnv#fonv#fallout: new vegas#thoughts#meta#caesars legion#fallout analysis

315 notes

·

View notes

Text

Boone takes off his hat when he gives you the quest.

Sure it’s kinda silly- he has two!

But. Him removing his hat is a sign of his vulnerability. He only does it when he’s asking you about the most important thing for him- Carla. He gives you his hat. He’s laying himself bare, in order to try to amend for his wrong-doings.

He canonically doesn’t like to take it off, and is distressed when you take it from him.

His hat is how he views his own identity. And it is so important to him. The fact he removes it shows how he is giving you a part of himself, in order to do what he thinks he already should have done

#Craig Boone#Boone#fallout new vegas#fnv#fallout nv#fallout#one for my baby#fallout companions#headcanon#fallout analysis

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just realized something I can’t believe I forgot to bring up when I discussed Harold’s vault in-depth a while back… if you haven’t seen it, you can read it here, but a big part of my analysis revolves around the character Diana, who took over Harold’s vault so she could pretend to be a nature god over the exclusively teenager-and-under inhabitants, when in actuality she was a human brain connected to a computer network.

The Van Buren design documents included a picture of what Diana would look like as she projected her “goddess” image to her cult, the Twin Mothers, obviously it’s just an edited photo as digital concept art and not meant to be the final design, but it gives us an idea of what the designers were going for:

Doesn’t the way she’s integrated into the trees remind you of something?

Ironically, when Harold’s mutation caused him to become rooted to the ground and create new life in the wasteland, he became the nature god that Diana so desperately wanted to be, except Harold was trapped in his state and had no desire to be worshipped!

It’s such a weirdly convenient bit of thematic paralleling that I can’t help but wonder if a Bethesda writer did this on purpose, except if that was what they were going for, wouldn’t they have had Harold reference this part of Van Buren to canonize it? I’m gonna have to chalk this up to a freak coincidence.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

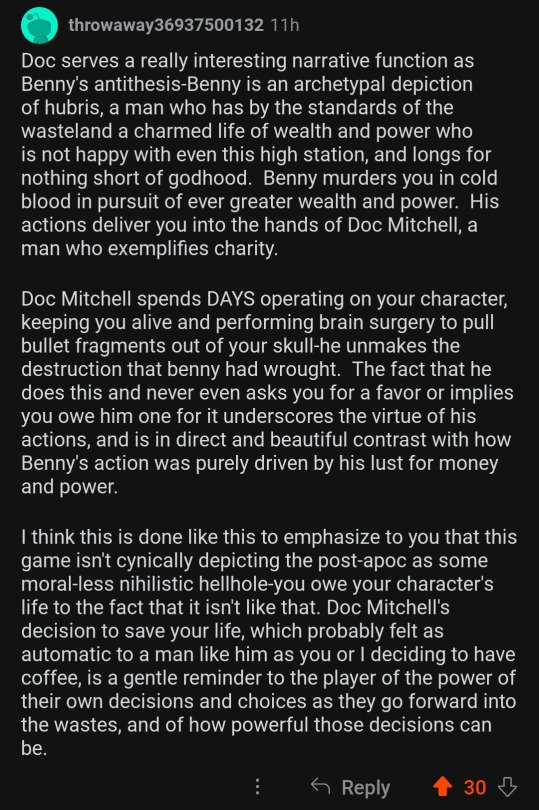

Sometimes Reddit has some gems, this was under someone asking why good old Doc is so good to the Courier (charges less for services etc) and this was the top answer.

I really like this take of Doc being the Anti-Benny and being a moral anchor for the player to make them think about their actions as the Courier.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

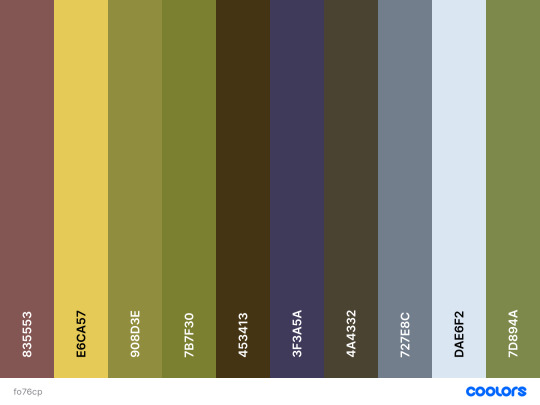

Fallout in ✨Colour✨

{Fallout 3}

{Fallout New Vegas}

{Fallout 4}

{Fallout 76}

since this post seems to be my most popular, check out Wasteland Weekly

#fallout#fallout 3#fallout new vegas#fo3#fonv#fo4#fallout nv#fallout 4#fallout 76#fo76#fallout aesthetic#fallout edit#fallout 4 aesthetic#fallout 76 aesthetic#fallout art#gaming art#colour palette#colour pallet challenge#colour aesthetic#colour analysis#medexfalloutedit

897 notes

·

View notes

Text

there’s something so brilliant in cooper howard’s costume design - it’s so much more than just a simple blue and gold cowboy fit.

at the beginning of the show, before the bombs dropped, cooper howard was a good person - always kind to others despite the circumstances or how he was feeling in the moment.

you could say… he was exemplifying the golden rule.

this is evident in his costuming - cooper is decked out in gold even when the bombs dropped. the golden rule is still so close to his heart - i mean come on - look at how tight that bandana is around his neck.

even in certain lighting, his hat looks gold.

cooper howard being a good person and living by the golden rule is what barb probably fell in love with (she has her own interesting character analysis and thought process which i would love to discuss later). because this trait is so admired by her and those around cooper, she probably saw him as who she would hope future generations would become as they grow up in the vaults. people like him are the better future she envisions - so it’s no coincidence that the vault suit is in his colors.

what does the blue symbolize?

well, to me, i think it’s the corporate presence in the world. there’s more blue in the suit than there is gold - hinting at vaultech’s corporate greed, capitalism, and evil machinations. (there was also blue in his old cowboy costume - i.e. the presence of the studio and how they use cooper to push a mccarthyism narrative. kinda in the same way vaultech will use him)

the blue in the suit - symbolizing vaultech’s overwhelming presence and the reason for such a bleak and cruel world - does not swallow up the gold - the small semblance of humanity’s capacity to do and be good. it’s the small hint at barb’s intentions (analogous to the road to hell being paved with good intentions).

yet the man who was an inspiration for vaultech’s workers - the man who they all wished they could be like, the man who symbolized all the “do good” ideas they pass down to their children but in the end have no intention of following them (wink wink, looking at you, hank) - was in the end stripped of all his humanity by the world vaultech created (wow, would you look at that? another analogy for capitalism!)

this man, once rich in morals now robbed of them all, wanders the wasteland a ghoul. everything has been taken from him - symbolized being devoid of layers of skin.

now, he’s nothing but the ghost of the man he once was - haunted by what has been done. everything he wears as the ghoul is frayed, tattered, and dark - symbolizing that cooper howard, that kind and caring man before the bombs is dead.

but wait - is that…

you don’t see it? Ok, i’ll zoom in some more

GOLD? (perhaps even the same shirt he was wearing during the bomb drop??)

perhaps the golden rule, those values that he once held so dearly, are still there just dormant - waiting to be awaken again.

maybe cooper howard can come back… that just maybe there’s still hope for the good in humanity…

#fallout#cooper howard#the ghoul#fallout amazon#fallout spoilers#ghoul x lucy#lucy x the ghoul#lucy maclean#maximus#fallout series#barb howard#hank maclean#fallout tv series#fallout show#fallout prime#maximus x lucy#mr. house#fallout 2024#cooper x lucy#cowboy#character analysis#costume design

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did anyone noticed this in their relationship development? Because omfg it starts and ends with the words "trust me" kill me

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Folks going "WHAT they made a show about the Fallout franchise?? I've been hearing people say Bethesda messed it up, but I haven't watched it myself, so I'm going to trust the word of other people -- some of which also haven't finished watching it" is driving me insane.

Being a hard core fan of something obviously brings with it a lot of passionate feelings when adaptations come into play. Of course, there's going to be people going "but in 8 episodes of the first ever season they made, they didn't explore Theme C or D, didn't introduce factions E and F and G, and because the source company is notorious for its scams, we and everyone else who's a TRUE fan should hate it".

The Amazon Original series Fallout follows the videogame franchise of the same name. It is a labour of love and you can tell by the attention to detail, the writing, the sets, and YES THE THEMES ARGUE WITH THE WALL. It's clearly fan service. I mean, the very characterisation of Lucy is a deadringer for someone playing a Fallout game for the first time. She embodies the innocent player whose expectations drastically change in a game that breaks your heart over and over again. Of course, she's also the vessel through which we explore a lot of themes, but I'll get to that.

There're some folks arguing that the show retcons the games, and I gotta say... for a website practically built on fandom culture, why are we so violently against the idea of someone basing an adaptation on a franchise that so easily lends itself to new and interesting interpretations? But to be frank, a lot of what AO's Fallout is not that new. We have: naive Vault dweller, sexy traumatised ghoul that people who aren't cowards will thirst over, and pathetic guy from a militaristic faction. We also have: total atomic annihilation, and literally in-world references to the games' lore and worldbuilding constantly (the way I was shaking my sister over seeing Grognark the Barbarian, Sugar Bombs, Cram, Stimpaks, and bags of RadAway was ridiculous). Oh, and the Red Rocket?? Best pal Dogmeat? I'm definitely outing myself as specifically a Fallout 4 player, but that's not the point you should be taking away from this.

The details, the references, and the new characters -- this show is practically SCREAMING "hey look, we did this for the fans, we hope you love it as much as we do". Who cares that the characters are new, they still hold the essence of ones we used to know! And they're still interesting, so goddamn bloody interesting. Their arcs mean so much to the story, and they're told in a genuinely intriguing way. This isn't just any videogame adaptation, this was gold. This sits near Netflix's Arcane: League of Legends level in videogame adaptation. Both series create new plots out of familiar worlds.

Of course, those who've done the work have already figured out AO's Fallout is not a retcon anyway. But even if it was, that shouldn't take away from the fact that this show is actually good. Not even just good, it's great.

Were some references a little shoe-horned in to the themes by the end of the show, such as with "War never changes"? Yes, I thought so. But I love how even with a new plot and characters, they're actually still exploring the same themes and staying true to the games. I've seen folks argue otherwise, but I truly disagree. The way capitalism poisons our world, represented primarily through The American Dream and the atomic age of the 45-50s that promoted the nuclear family dynamic -- it's there. If you think it's glorifying it by leaning so heavily into in the adaptation, I feel like you're not seeing it from the right angle. It's like saying Of Mice And Men by John Steinbeck glorifies the American Dream, when both this book and the Fallout franchise are criticisms of it. If you think about it, the post-apocalyptic world of Fallout is a graveyard to the American Dream. This criticism comes from the plots that are built into every Fallout story that I know of. The Vaults are literally constructed to be their own horror story just by their mere existence, what they stand for, what happens in each of them. The whole entire show is about the preservation of the wrong things leading to fucked up worlds and people. The missions of the Vaults are time and again proven to be fruitless, unethical, plain wrong. Lucy is our brainwashed character who believed in the veritable cult she lived in before she found out the truth.

So then consider the Brotherhood of Steel. I really don't think it exists in the story to glorify the military. We see just how much the Brotherhood has brainwashed people like Max (also, anything ominously named something like "the Brotherhood" should raise eyebrows). Personally, I don't like Max, but I am intrigued by his characterisation. I thought the end of his arc was rushed the way he "came good" basically, but [SPOILERS] having him embraced as a knight in the Brotherhood at the end against his will -- finally getting something he always wanted -- and him grimly accepting it from all that we can tell? Him having that destiny forced upon him now that he's swaying? After he defected? If his storyline is meant to be a tragedy, it wouldn't surprise me, because Fallout is rife with tragedies anyway. And a tragedy would also be a criticism of the military. That's what Max's entire arc is. It goes from the microcosm focusing on the cycle of bullying between soldiers to the macro-environment where Max is being forced to continue a cycle of violence against humanity he doesn't want to anymore because a world driven to extremes forces him to choose it to survive (not to mention what a cult and no family would do to his psyche). Let's not forget what the Brotherhood's rules are: humankind is supreme. Mutants, ghouls, synths, and robots are abominations to be hated and destroyed. If you can't draw the parallels to the real world, you need to retake history and literature classes. The Brotherhood is also about preserving the wrong things, like the Vaults (like the Enclave, really). They just came about through different method. The Enclave is capitalism and twisted greed in a world where money barely exists anymore. The Brotherhood is, well, fascism plain and simple.

Are these the only factions in the Fallout franchise? Hell no. But if you're mad about that -- that they're the main ones explored, apart from the NCR -- I think you're missing the point. These themes, these reminders, are highly relevant in the current climate. In fact, I almost think they always will be relevant unless we undergo drastic change. On the surface-level, Fallout seems like the American ideal complete with guns blazing that guys in their basements jerk off to. Under that surface, is a mind-fuck story about almost the entire opposite: it's a deconstruction of American ideals that are held so closely by some, and the way that key notion of freedom gets twisted, and you're shooting a guy in-game because it's more merciful than what the world had in store for him.

I mean, the ghoul's a fucking cowboy from the wild west character he used to play in Hollywood glam and his wife was one of the people who helped blow up America in the name of capitalism and "peace". There are so many layers of this to explore, I'd need several days to try and keep track and go through it all.

The Amazon Prime show is a testament to the Fallout franchise. The message, the themes? They were not messed up or muddled or anything of the sort, in my opinion.

As for Todd Howard, that Bethesda guy, I'm sure there's perfectly valid reasons to hate him. I mean, I've hated people for a lot less valid reasons, and that's valid. We all got our feelings. But the show is about more than just him. My advice is to keep that in mind when you're judging it.

#fallout series#amazon prime fallout#amazon prime video fallout#amazon fallout#prime fallout#fallout#besthesda#todd howard#fallout spoilers#some light analysis#the american dream#militarism#lucy mclean#maximus fallout#cooper howard#the ghoul#I know they're not planning a skyrim adaptation and that's fine#I prefer it remaining in its videogame medium while I write fanfics#so if they had to adapt any of their games I'm actually glad it was fallout#also please forgive me I wrote this very late at night so there's probably a bunch of mistakes#and I've played fallout for like six years and still don't know anywhere near as much as the hard core fans but I'm also not a newbie

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'd prefer if we never got to see the origin of Vault Boy and Vault Tec's branding in the same way I'd rather not get a canon answer of who started the War or how. That's the point of War Never Changes.

Vault Boy is a sinister figure in his cheerful embrace of Armageddon. Giving the Vault Tec brand a face and a name and a backstory feels so unimportant to what is actually interesting about Fallout. What's important to me is the big picture pre war, and the details of what comes after.

What is interesting to me is exploring how propaganda is designed to convince people how close they are to annihilation--or homelessness, unemployment, obscurity, or being The Other and therefore destined to suffer--in hell, in oppressions, being ostracized. Honestly insert any sort of marginalization or suffering here. Crony capitalism uses propaganda to market products designed to manipulate people into buying distance between themselves and that annihilation. Putting themselves "behind the thumb" of Vault Boy, so to speak. Buying a lifestyle. Vault Boy does it with a wink and a smile, inviting those who can afford it to buy their way to safety while using capital and fear to perpetuate the cycle. I don't need the specifics to understand this.

Some ghoulnaysis below the cut:

I'll admit, my initial reaction to pre-war Ghoulgins being the inspiration for Vault Boy was funny! Mr. Cooper Howard, washed up actor experiencing an existential crisis being shoehorned into corporate propaganda that then haunts him for the next 200+ years? Selling manifest destiny, racism, the Rugged Individual, the revisionist history that cowboys were a) white and b) more than a brief footnote in the history of the colonization of North America's west. The commodification of entertainers/creatives/public figures. Selling identities to be packaged into a product that will outlive them? Only to have that person live alongside that role they regret (?) playing... kinda tasty, if we have to give Vault Boy a backstory, though I didn't get a clear sense of his actual feelings about being used as a propaganda guy which I think is a failure of the show to commit to the narrative they set up, which happens with a lot of the show's (lack of) engagement with Fallout's larger themes anyway.

But The Ghoul (stupid name!!! weird and boring choice!!!) is just such an uncompelling and repellent character to me. I love a good bad guy or even anti-hero, but honestly he lacks any interiority. He's an evil karma character (eats people, waterboards and mutilates people, sells people to organ harvesters...like? that literally makes you evil in the games...) but the narrative pushes him as an antihero or someone with gray morality because he what..."likes" dogs? And isn't as decayed or unsettling looking as other ghouls (implying handsome=good or interesting). People aren't afraid of him because he is a ghoul, they're afraid of him because he's evil and will hurt them! Sometimes for no reason! I see the callback to the director telling him to shoot his co-star and Cooper saying he's "the good guy," but is that why he becomes so fucking evil post war? Really?

I don't know why he does what he does other than...the world sucked before and sucks now so he might as well represent the basest of human behavior? That seems to be the thesis of the show--unless kindness and community is engendered (by the vaults, by Management, by a civic government, by corporations) people will descend into chaos.

So why have this poorly executed anti-hero be the origin of Vault Boy? What are the narrative choices being made here? Is it just Rule of Cool?

Personally I would like a pathetic, rotting wet cat of a ghoul, some sort of carved out husk of a washed up movie star either trying to relive his glory days, or avoid them--having given up hope of finding his family after 200 years--being dragged into Lucy's orbit and being constantly reminded of his Vault Boy fame, that she is a walking Vault Girl with her Okey Dokey's and Golden Rule. He'd be a joke, a footnote of the old world. He'd be mean and snarky, even unpredictable and uncooperative--have a public persona of friendly curiosity and a private, cynical one.

Pathetic Ghoulgins would remind audiences of the cost of capitalism and imperialism without resorting to the thesis that war never changes means that people are inherently cruel and will resort to violence, rather than existent corporate and political power structures intentionally create the conditions in which people accept perpetual cycles of exploitation and harm for the sake of their own safety and comfort, despite knowing the cost of maintaining the status quo, and not seeing or believing that distance between the status quo and total annihilation is measured by the smiling thumbs up of a cartoon mascot.

I'm sure there are other ways The Ghoul could have been a successful character as well but.... That's satire. That's interesting. That's Fallout.

#fallout#fallout tv#fallout prime#fallout tv show#the ghoul#cooper howard#vault tec#“let people enjoy things” well i enjoy critical analysis#i dislike the big picture of the show but i love fallout enough to dig through the mess#fotv critical#fallout critical

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

Danse & Hancock's parallels are eating my sanity slowly so by God I will write them here

So. Usually incredibly shy about posting my feelings about characters and my interpretations of them, but I don't think I can sit idly by without addressing 1. how much I love this post about Danse and how his story ties back to the isolation and loneliness of autism, and 2. how much I need more content between Hancock & Danse to exist, because my god sometimes I forget they hate each other in-game. (I strongly suggest you read the post mentioned & linked, they do a fantastic job framing Danse in a way I don't think I could fully articulate)

Danse & Hancock both have stories filled with themes of intense loneliness. Despite their hard work, effort, and prowess in the things they love, it doesn't take good sight to realize that neither of them are very well liked. It's not that they aren't respected, but whether it's Danse's all-too-formal approach to speaking, or Hancock's combination of hard drug use & almost constant overbearing presence (on top of years of slander from bigger cities, but we'll get into that), people see them as a tool of success and a good asset to have around, but not much of a friend, so to speak. Especially in Hancock's case, many people he is overly-affectionate with are often more annoyed by his presence than anything else (even if they do like him).

For Hancock, despite how much he claims to not relate to the isolation of the common ghoul, he's likely over-exaggerating his charisma in an effort to make himself more easily approachable, mostly for his own peace of mind rather than for others. While he sounds quite passive about things many others would react strongly to, I feel it's a combination of him having replaced a layer of how he truly feels with an element of sass on top of the drug use that makes all the trauma more easily bearable (to mixed effect).

One of his lines that has always struck me as conflicting with how he portrays himself is a common generic line he has while traveling with Sole Survivor, praising them for "living out the day" when most others could not. Hancock has seen so many people die to the brutal hands of the Commonwealth; whether it be Vic and his boys gunning down innocent drifters, seeing people succumb to the elements, or, in this case, simply not surviving their travels with him, Hancock seems to have a track record of never properly establishing proper bonds with others before they either die, or decide he's too overbearing to deal with further. He's one of those characters who desperately wants to have a deeper connection with those he loves, but he has consistently lost the chance to do so before he was ever ready, and so he chooses to fill the void with meaningless sexual relationships and one-night stands- anything to make him temporarily forget how much he hates himself and his almost comical lack of social understanding. It's a train of thought that I, as an autistic person, can really understand and relate to-- the desire to know people, but always feeling like no matter how you portrayed yourself, no one seems to want to be around you if you don't provide them with what they desire. It's caused him to deeply undervalue both how much he's done for people (since he believes its expected of him to constantly bend over backwards for the needs of others), and himself, all at the same time.

I don't think Danse fully recognizes how lonely he feels, a lot. He's been so heavily indoctrinated by the Brotherhood of Steel into believing that this is how he should be treated, that his work is for the betterment of humanity, that his sacrifice is a necessary one. The way he speaks almost carelessly about late brothers and sisters in arms makes me think really hard about how rooted this idea of only existing for the "greater good" is. Individuality is questionable & almost taboo, being different is outright abominable. It's the reason why the rhetoric of "Us vs. Them" works-- the BoS as a collective believe that they are doing good for all of humanity, and any outlier to that "perfect" formula is a threat not only to the BoS, but to everything they know. Danse is expected to bend over backwards for people, and no longer questions his loneliness or isolation, as he has all but given up his sense of self for what he believes is right. Another thing that I and many of my autistic friends relate to; a sense of justice so strong that it's overpowering. Like us, Danse is willing to sacrifice anything to do what's right... including himself.

Knowing this, it's easy to understand why he hates Hancock, and that backwards mindset is the reason Hancock hates him. It's an especially vicious cycle that constantly feeds into itself if unchecked, and Hancock knows that he alone cannot convince Danse to break that cycle. Hancock knows he can't beat Danse in a fight; all he has are his words, and logic is useless against an enemy that heeds to no truths. Even after Danse discovers his true nature... you can't expect him to unravel the years of constant reassurance that what he was taught was right in a single night. "Rome wasn't built in a day," and no one gets over their trauma so quickly, either. It's traumatic to have an explanation as to why people hate you. A catch-all reason to people's fear and distaste to you, that is also something you can never, ever change. Danse would sooner hate himself for what he is than accept those he used to murder without a second thought. It's the difficult reality of anyone attempting to unlearn painful conservative narratives; the shame & guilt of hurting others that are more similar to you than you ever wanted to know is sometimes more painful than realizing what you really are.

Hancock, albeit not even close to "recovered" from his mental woes, is much further along the path of acceptance to Danse, but not far enough away that he wouldn't understand where Danse is coming from. For so long, he sat idly by and watched people get hurt, even during his time in Diamond City. The constant conditioning to accept other people's pain as long as it wasn't happening to you still eats at his consciousness; just like Danse, he knows it was wrong to accept it, but the guilt makes it harder to deal with. He, of all people, would understand what it feels like to try so, so hard to fit in, to be normal and accepted, but never quite hit the mark of understanding where he fits in society. That's the reason he is the way he is now; his signature, his "Hancock," is to be as loud and out-of-place as possible-- a constant rebellion against what people expect him to be, a rebellion of oppression and unfair treatment. Danse's sheer existence is an involuntary rebellion of all BoS values, and even if Hancock would be hesitant to become close to Danse for a long while, I think he would be impressed by him, in the end, and more importantly, understand where he's coming from.

Their combined interest in both protecting the people they care about as well as the collective societies those people come from, as well as how nerdy they both are about US history... I think, eventually, they will realize how similar their lives were, how similar they are to each other, and maybe even find some comfort in knowing that they aren't alone in all of the waves of shame, guilt, and loneliness. That there is an overarching group of people who understand them, and that they do have a place in this world. I think once they recognize that similar traumas can manifest in polar opposite conditions (ones that they used to have a narrow, black-and-white outlook on), they'll also find that there is no real reason to hate each other anymore; the world has told them that they must hate each other, but they no longer have any need to listen.

TL;DR autistic Danse & Hancock ftw

#fallout 4#john hancock#paladin danse#sorry for the long analysis im just rotting over them so hard#fo4#i think they deserve the world#and maybe also therapy#fuck you todd howard for not finishing Danse's arc i cry#ARGHHH i hope people understand my vision...

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

An aesthetic decision I really like about the Mad Max setting- focusing on Fury Road in particular here- is that the timeline and the setting deliberately defy coherence. Countless elements of our world have carried over- the guns, the vehicles, the musical instruments, the religious concepts, and nominally some of the actual people- but the world is geographically impossible, you don't see much contemporary architecture even in a ruined state, and there's no version of the timeline where this can be the same Max Rockatansky as the original films. But it is. The incongruities are deliberate. The setting is mythic, these are campfire tales told about Max, the King Arthur or the Omnipresent Jack figure of the new age. The world that was is swallowed in myth, the world that exists is borrowing some of the old world toys, and being up-front and bombastic with signifiers of the mythic and abstracted nature of the setting absolves you of the need to make the worldbuilding make sense- or rather, to make it make sense in the way you'd have to take a stab at if you had a year-by-year internal worldbuilding timeline of How Everything Went Down.

Fallout 1 is not exactly like this. It can't be, because you could kill a man with an overhead swing of the setting bible. But it's tapping into a similar impulse. People in the first game are using old world tech, but they don't really live in the old world; they live in settlements using materials scavenged from the old world, or in old world towns that were unimportant enough back then that their current identity totally overwrites whatever came before. They don't live in LA: They live in the Boneyard, which gives you a pretty good idea of how much of what we think of as "LA" would be recognizable as such if we were exploring the space in first-person perspective. When you encounter an area that has a direct, well-documented, and unambiguous connection to the old world, it's a Big Deal, and they're hard places to get to- places that the average person living their life in the wastes would die trying to access. Of particular note in this dynamic is The Brotherhood of Steel- for all their technical understanding of the knowledge they hoard, they've clearly seems to have undergone a few rounds of Canticle-style cultural telephone, mutating from Recognizably The American Military into a knightly order. Fallout 2 does this to a lesser extent- it has more settlements directly named after their pre-war counterparts- but it's also a game about a society that's starting to pull back together and form into something resembling the old world, for better or for worse. And it reproduces the trend of stuff with a direct, legible connection to the old world being inscrutable and dangerous to outsiders- specifically with the reveal that the Enclave consider themselves to be the direct continuation of the pre-war government, that they've just kept electing presidents out on that stupid little oil rig. I haven't really made up my mind on whether the timeframes of the games- 84 years followed by 164 years- actually work for the vibe they're going for, in particular it doesn't work with Arroyo- but on the whole, the vibe coheres.

You get into the 3d games, and it becomes much harder to continue to pull this off. One major tool that Fallouts 1 and 2 used to maintain that sense of abstraction was the overland travel map; you were visiting island of society in a vast sea of Nothing. You had encounter cells that consisted of burnt-out, looted shells of cities, maybe good for a camp site but not as anything else. Another important tool towards this end was the isometric camera angle. In a topdown worldspace you can scrub out a lot of environmental details that would be immediately recognizable to the player as artifacts of our present society if you were exploring the space in 1st person. The examine button can feed you vague, uncertain descriptions that convey enough detail to make the item recognizable while also conveying that there's been a level of information decay. Once you move into a 3d worldspace you lose both of these elements- the worldspace is what it is, I can walk across it in eleven minutes stripping it for loot as I go. I can read every sign on every still-standing building, and I've got eyeballs on every old-world bit-and-bobble with a handy interface description of what I'm looking at. And you hit random encounters in the 3d games at basically the same rate, in real-world time, that you did in the isometrics- but the isometrics could successfully abstract it out to represent that you were hitting something noteworthy every couple of weeks, while in the 3d games it's kinda inescapable that you keep getting jumped every single day walking back and forth up the same stretch of road. Not only is it recognizable, it's cramped.

I think that Fallout 3, to its credit, did a decent job of navigating this and trying to maintain the islands-in-a-sea-of-nothing vibe from the isometrics- most of the settlements are built slapdash in places that were obviously never intended for long-term human habitation (bomb craters, overpasses, suburbs), the landmark-heavy city proper is textually a difficult-to-navigate deathtrap, and the poison-sky green filter, memeworthy as it is, does help shore up the impression that you're inviting death by trying to move through the space. Fallout: New Vegas I think addresses this by going in the total opposite direction; It's set in an area of the country where the infrastructure was abnormally well preserved, and the pre-war culture was revived artificially, and from a thematic standpoint it's really interested in digging into the implications of those two things. The fact that the lonely-empty-decontextualized-void aesthetic isn't long for this world dovetails well with the cowboy themes. They have a fair number of future-imperfect context-collapse gags but they don't overdo it by any stretch of the imagination.

Fallout 4, from many directions, is sort of catching the worst of the heat here. The world is recognizable, aggressively so. In fairly-authentically recreating the suburban sprawl of the Northeast, Bethesda simply surrounded the inhabitants of the commonwealth with too much Boston for a sense of true distance from our world to be possible. Everyone still has the accents. They still know the names of all the old neighborhoods. They're still doing the "Park your car" bit. It's still Boston. And it's a busy Boston, too- you can't throw a rock without hitting a farming settlement that's doing well enough to attract tribute-seeking bandits. It's densely packed with points of interest, and those points of interest are packed to the brim with salvageable materials that, going off of the new crafting system, should be in enormous demand to the people who've been living in this area for 210 years. The game doesn't really advance a satisfying explanation, even an aesthetic explanation like fallout 3's poison sky, for why everything around you hasn't been stripped clean before you even came off the ice, why all these environmental storytelling tableaus are just waiting for you to find. It doesn't spend nearly enough time hammering out what the 200-year chronology of the most-livable area seen in a Fallout game looks like- Why don't you see something comparable to the NCR emerging? Something something CPG massacre (which is mentioned twice in the whole game, AFAICT.) And what's being lost here, right, is the ability to use the sands of time to smooth over rough spots in the worldbuilding, in the chronology. You can't hide behind the idea that the world you're experiencing is mythologized. It's presented as real, and it doesn't make much sense if it's real!

And to top it off- Fallout 4 probably has the highest density of characters who were actually there, by some means or another. The Vault Tec rep, Daisy, The Triggermen, Nick Valentine, Eddie Winter, the vault 118 inhabitants, Arlen Glass, Oswald, Kent Connolly, The whole of Cabot House, Captain Zao, The kid in the goddamn fridge and his goddamn parents, and uh. The big one. You. You, the player. Which is such a goddamn splinter under my skin, from a storytelling perspective. You were present in the before-times- but only nominally, only to the exact degree necessary to establish that that was the case. The ugly shit is alluded to, but not incorporated into the character's day-to-day in a way that's obvious to the player, you're there for like six minutes and it's pretty nifty if you overlook that bit at the end where everyone got nuked. Your ability to talk about the world before is always vague, vacuous, superficial. The dirty laundry you dig up on terminals around Boston never seems to meaningfully impact your character's worldview, their impressions of the then and the now. All of which combine to make this the simultaneously the most specific but also the most frustratingly vague game in the series. At its best, Fallout's love of juxtaposing the then and the now would make it a great setting for the Rip Van Winkle routine. But it requires a strong, strong understanding of what the world was like before and after, a willingness to use the protagonist to constantly grind the jagged edges of those things against each other, a protagonist with a better-defined outlook than Bethesda's open-ended-past approach allowed for- and it has to be in service of a greater point. And for Fallout 4 to do anything with any of that, the game would have to be about something instead of being something for you to do. Maddening. Maddening.

#fallout#fallout meta#thoughts#meta#fallout 4#fallout 3#fallout new vegas#fallout 1#fallout 2#fallout analysis

346 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another reason why I think Hancock would have a crush on the Sole Survivor besides the obvious fact that you're out here helping the people of the Commonwealth, or how he thought you were an innocent vault dweller who needed protecting, is the fact that he's finally got someone he can be emotionally vulnerable with. Being the mayor of such a dangerous place like Goodneighbor means he needs to keep up a reputation to match it. There's no room for him to be soft or emotional in a place like this.

He's happy when strangers know who he is for having reputation that precedes him for being deadly because it eliminates any chances of someone out there possibly getting the idea that he might actually have a sweeter, more caring side. That's one of the main reasons why he even killed Finn in the first place. But he WANTS to be able to express softness. The problem is just that Goodneighbor isn't the place to do it, and a lot of the kinds of people you find in the Commonwealth in general aren't really the greatest types to be emotionally open towards anyways. In a world like this, it's something that could very easily be held against him.

He tells you that it's lonely being mayor and that he's running out on the good things and people he's got. He tells you that he's always been the one telling others to keep the emotion out of relationships in the past, but here he is being open and emotional with you. He says that everyone is entitled to some softness, himself included… but after he opens up to you about running out on the good things in his life, he asks you not to tell anyone else. Not necessarily because of the fact that it's personal, but because of the fact that he's afraid of word spreading around about this more emotionally vulnerable side of him and that people will think he's crazy for it (and as a side note, let's be honest, we've all seen how society on a larger scale views emotionally vulnerable men as weak).

A lot (not all) of his contradicting ideals when you first meet him make so much more sense when you look at him through the lens of a man desperately trying to conceal and repress the more sensitive side to him. The way he just lets you get away with so much during The Big Dig questline, even if you take your time to do every little thing against him. It's obvious that he doesn't really care all too much about punishing you - he just likes knowing he still has the power to make people frantically scramble to please him, because it helps uphold his reputation.

If there's one thing Hancock hates being more than anything, it's being powerless and weak. His biggest traumas come from how he was unable to protect the ghouls in Diamond City from being exiled or protect the drifters in Goodneighbor from being abused by Vic. If people in the Commonwealth knew there was a softer side to him, a large majority of the more dangerous organizations, especially the ones operating in his town, would consider him weak. If Hancock was considered a weak leader, then he wouldn't be considered fit to protect the innocent people that he so sworn to protect.

It's always baffled everyone how Hancock doesn't show any sadness when it comes to the death of Fahrenheit or finding out his brother was replaced by a synth and killed years prior, but I'm starting to wonder if we've been looking at it the wrong way this entire time. Maybe Hancock's lack of being visibly upset over them had nothing to do with Bethesda making poor writing decisions (they kind of do tbh), but had everything to do with him repressing his emotions.

So when he gets to travel with YOU the player, who has no prior knowledge of him, his reputation or past (and you aren't just another citizen he has to put on a show for) he feels like he can let his walls down around you. He's allowed to be emotionally vulnerable because he doesn't have to pretend to BE someone for you, and in turn, he feels like he doesn't have to run anymore.

(That was a lot sorry but I tend to get my thoughts out better in the form of long ramblings. Honestly there's so many ways he can be interpreted though, but I guess this is just somewhat of an analysis/me theorizing a little)

#the way he immediately drops the deep tough guy voice once he's available to be your companion is very telling#And how he's always making jokes to hide his feelings#Or how when you romance him and then proceed to do bad things he tells you about how it's not easy to confront you about it#goodneighbor has not been good to his mental health#I don't care what anyone else says he needs a good cry whilst being tenderly held#This isn't me saying he's an uwu baby who can do no wrong but he just needs a healthy outlet to express himself better you know?#Hancock has emotional guy forced to repress deeper feelings due to trauma (and probably societal standards) vibes#fallout#fallout 4#hancock#ramblings#analysis/theory I guess?

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

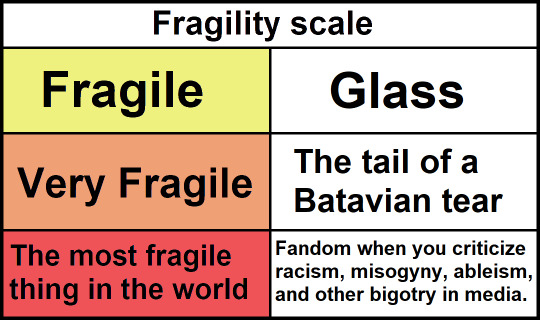

new meme format.

[ID: A chart labeled, "Fragility scale", with three colums down the side.

The first is labeled "Fragile" in yellow, and reads, "Glass".

Next is "Very Fragile" in orange, for "The tail of a Batavian tear".

Last is "The most fragile thing in the world" in red, for "Fandom when you criticize racism, misogyny, ableism, and other bigotry in media.".

End ID.]

Download the HD template from the internet archive here. The image description should be copied and pasted whenever you use the meme, just edit whichever parts you're changing. No credit is necessary as long as you make your post accessible.

#described images#describes memes#accessible memes#meme template#meme format#white fragility#fandom racism#fandom misogyny#fandom ableism#fandom bigotry#klandom#memes#new meme template#fragility scale meme#fragility meme#fandom fragility#bigoted fragility#media analysis#media criticism#anti-intellectualism#anti intellectualism#Fallout TV#Fallout show#Fallout TV show

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

As much crap as we like to give Fallout 2 for many of its writing choices, and deservedly so to an extent, it’s still impressive how much work the devs put into it and that it manages to stay mostly cohesive considering that they had only about a year to work on it, though some people have said they might have been working on it for only nine months. And I thought New Vegas’s dev time of 18 months was ridiculous!

Sure, Fallout 2 didn’t have as much going on with its 90′s engine/memory limitations, but when you factor in the different writing for various playstyles like a low INT run, that’s still a lot of text and programming that had to go on!

It feels kinda tragic, because there’s just enough good material in there for me to want to play through the game again, and it makes me wonder that if Black Isle had more time to work on it, then maybe cooler heads could have eventually prevailed and they could have fixed a lot of the writing issues that are in the final release like the overuse of stereotypes, the lackluster writing for most of the female characters, the out-of-place comedic moments, etc. (and of course put in some of the content that had to be cut due to deadlines).

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on The Ghoul

So I think all the characters in the Fallout show are spectacular, but I had some thoughts on The Ghoul/Cooper Howard in particular that I just wanted to put down. Owing to his 200+ years of history, he's a downright fascinating, dynamic character, and I can't wait to see what they do with him next.

Anyway, here's my thoughts/character analysis of The Ghoul:

One of the things I found most interesting on my second watch-through of the show was how everything The Ghoul does is motivated by ruthless pragmatism, not cruelty. It can appear like cruelty--sometimes it tips over into cruelty--but cruelty is not the point. The point is always survival. He must survive to find his family. That is his goal and his one guiding tenet. Nothing else matters, everything else is fluid. Whatever it takes to survive.

Getting rid of the three bounty hunters who dug him up? Survival. Two of those guys were already one twitch away from killing him on the spot for being a ghoul, and the other threatened to harm him if he didn't show enough gratitude. Coupled with some of the other things he was saying, it seemed possible he would double-cross or kill The Ghoul the moment it suited him. No doubt The Ghoul has worked with the type before, and knew trouble when he saw it.

In Filly, he only shot people who were shooting at him. Cooper loves dogs, but he stabbed CX-404 because she was actively trying to kill him. On the surface, he healed her for equally pragmatic reasons: she could lead him to Wilzig. But he also seemed to respect, too, that she clung to life despite her debilitating wound. She's not his dog Roosevelt, so he tries to maintain a cold detachment from her (at first), but he has a soft spot for dogs.

He was willing to shoot Lucy in Filly, but he hesitated--which is more than he did for any of the other people threatening his life. Possibly he wouldn't have killed her (she was armed with a non-lethal weapon) until Maximus showed up on the scene and changed the calculus (dispatch the girl and deal with the newer, bigger threat without having to worry about her finding a lethal weapon and killing him with it). He didn't kill Maximus when he had the chance, either. He didn't need to. Maximus had already shown himself to be incompetent with the power armor. It was simple enough to damage the power armor and watch him tuck tail and run.

When he meets Lucy again, he uses her with the same casual, indifferent efficiency as he would any other tool. The point of dunking her in the water was to lure the gulper. It had the unfortunate side effect of also being torturous for Lucy, but the cruelty wasn't the point. Getting the head back was. The head=caps, caps=meds, meds=survival, survival=eventually find family.

We don't know what The Ghoul would have done if they had retrieved the head from the gulper and his medicine hadn't been destroyed. Probably it would have depended on what Lucy did. If she seemed likely to come after him and the head, he probably would have killed her or incapacitated her and left her for dead. If she had explained she needed to trade it with Moldaver for her dad, Hank MacLean, hoooo boy, he would have beelined for Moldaver's with Lucy in tow. Whether Lucy came along as his partner or his captive/extra bargaining chip would also probably depend on Lucy's behavior.

But they lose the head and The Ghoul's medicine is destroyed. The math changes. He can come back for the head, but he needs meds now, which means he needs caps now, and the only thing of value he has on hand is this pampered girl from a fucking vault who seems patently unwilling to do the things that need to be done to survive in the Wasteland anyway, so if she's gonna die, he might as well profit from it. He needs meds to survive. He needs caps for meds. It's simple, brutal math.

While he's hauling her to the Super Duper Mart, though, he does several interesting things that are degrading for Lucy, yes, but are simultaneously teaching her how to survive the Wasteland, testing to see if she'll adapt. First, he mercy kills Roger and butchers him. It's important to note that The Ghoul didn't have to take a detour from his all-important mission to obtain medicine--he could hear it was Roger, he could tell Roger was going feral and didn't have any meds-- but he went anyway to help ease an old friend's passing. And he made sure Roger's last thoughts were pleasant, too.

Then, because this is the Wasteland and the one law is survival, he wastes no time switching gears. There's no waste in the Wasteland, and a fresh dead body presents an opportunity for those willing to seize it. The Ghoul, mind you, has had 200 years to learn that he can't be picky. Ghouls are unwelcome in most "civilized" parts of the Wasteland, barred from the simple comforts and safeties and securities that other people can enjoy if they reach those scattered, precious oases. The Ghoul has had to eat people. It sucks, but it's that or die.

But Lucy doesn't understand that. She arguably doesn't understand what a ghoul even is because nobody's taken the time to tell her. She doesn't know what the last 200 years have been like. She's appalled--and then she has the audacity to voice her disgust. The Ghoul hands her the knife to keep butchering Roger in part to humble her, to drag her down into the dirt with the rest of them, but he's also teaching her a stark reality of the Wasteland. It was a lesson and a skill that he had to learn the hard way. (Interestingly, while nearly everyone in the Wasteland is disgusted by cannibalism, it's also a known thing that happens all the time. The Ghoul and Lucy are in the interesting position of being some of the only people in the Wasteland who were raised in societies where cannibalism truly was unthinkable).

On the walk to the Super Duper Mart, he refuses to give her water. On a pragmatic level, there's no reason to waste water on the equivalent of a dead woman walking--he's leading her to get her organs harvested, after all. (He is pretty petty when he pours out the last drops instead of giving them to her, though). But also, whether he is actively intending to or not, he is teaching her to adapt to Wasteland conditions. The water in his canteen, in fact, was just as irradiated and gross as the standing water from which Lucy ultimately drinks; he refills his canteen from the same rusted-out vessel Lucy drinks from, and likely drew the previous canteen's worth of water from a similarly unpalatable source. This is water in the Wasteland. Drink it or die.

When she runs away shortly after, he lassos her (and, sidenote: can I just add how fucking cool it is that they actually carry through his lasso skills? Like, that is actually an extremely useful skill and the writers utilized it!), which leads to that pivotal scene where she bites his finger off and he takes hers.

This is interesting for multiple reasons. The Ghoul calls her a "little killer" and seems satisfied to see her finally fighting with the same savagery as a Wastelander. This could be either because a) he believes all people have a killer lurking beneath the facade of civility ("I'm you, sweetie. Just give it a little time...") and she's finally found that steely will to survive no matter what it takes, and/or b) he believes she's been faking her doe-eyed, good girl persona. He's the one who first finds Wilzig's body, after all. To him, it looks like Lucy lured the doctor off and ruthlessly chopped off his head before running off with it. Maybe she's just a really good actress, and in biting his finger off, she's let that mask slip.

Either way, he introduces her to another law of the Wasteland: don't dish it if you can't take it. She takes his finger, he takes hers. He doesn't kill her for it, in part because that would be disproportionate, in part because that would be a waste (he probably needs he alive to exchange her for caps). But also, from a practical standpoint, she just bit off his shooting finger. Unbeknownst to her, ghouls can reattach body parts, even ones that are not their own. He's harvesting his replacement from her. If he wanted to be cruel, he had ample opportunity to be cruel here. He could have taken more fingers. He could have hurt her in ways that wouldn't have affected her value to organ harvesters. He could have degraded her and called her all kinds of nasty names. But he doesn't. He's efficient. If anything, he seems almost proud of her for abandoning her hoity-toity principles and fighting back.

He still needs caps. He's feeling the effects of not having his medication. He's still committed to delivering her to the organ harvesters. In his mind, he has no choice. This is about survival. He has to survive to find his family. This is the option he has available to him. This is how he lives to see another day. He brings her to the Super Duper Mart and, drawing deep from that actor's well, he maintains the tough-guy routine long enough to intimidate her inside, then he succumbs.

He's still down when Lucy re-emerges, victorious, and he knows, he knows that he's dead. He tried to kill her, now she'll kill him. It's the smart thing to do, the practical thing to do. Another law of the Wasteland...

But she doesn't do it. She has all the power here, she knows he's a dangerous element, that she would probably be safer if she left him for dead or killed him herself. But she breaks all the rules. She gives him, freely, generously, with supreme dignity and a selfless kindness he had long forgot, an abundance of the thing he needs to survive, the thing he was willing to sell another human being for no questions asked. Just like that.

There's also something to be said here about how resource scarcity (and the removal of that scarcity) affects people. As soon as The Ghoul gains a cache of at least 2 months worth of medicine, it frees him from the basic math of mere survival. He has room to breathe and think long-term (at least by Wasteland standards). He can reflect on the momentous thing that just happened to him, too. As he watches himself on the TV in the Super Duper Mart, watches the man he once was unwillingly (and unwittingly) take the first step onto the path to what he has become, he remembers what it was like being Cooper Howard. Why he, Cooper Howard, hated the "feo, fuerte, y formal" scene so deeply.

Cooper Howard was a kind, moral, and dignified man who seldom said an unkind word. He was a loving husband who deeply respected his wife and absolutely adored his daughter. Though his naivety, privilege, and ignorance blinded him to the ugly realities of the pre-apocalypse world around him, he valued justice, freedom, and equality. He wanted the characters he played in the movies to reflect that belief in the power of the law and respect the innate humanity of all people, even the villains. And, when he began to see the cracks in the perfect picture of his charmed life, he is driven to know the truth behind the facade. His deep, defining belief in justice and truth would not let him leave it alone.

Cooper Howard learned the truth that Vault-Tec (and by extension, his wife) were willing to drive the world off a cliff, and it destroyed his marriage and deeply affected him. Even then, demoralized and hurt as he was, he found it in himself to be thoughtful and kind to his daughter and the people, both adults and children, at the birthday party he worked the day the bombs dropped. Fundamentally, he was still a kind, moral man. And that kind, moral man found himself in the middle of the most horrific nightmare anyone could ever imagine experiencing: the death of the planet under a rain of atomic bombs. Then he lived through it and had to contend with the harsh realities of surviving on the annihilated landscape left behind. Fortunately for him, he already had several handy skills to carry him through: having formerly been a real cowboy, he knew a thing or two about surviving in tough conditions; having formerly been a soldier, he knew what it took to kill a man and had the experience and fortitude to do it; and finally, having formerly been an actor, he had a built-in psychological coping mechanism to insulate him from the horrors of the things he needed to do to survive.

Cooper Howard used to put on and take off personas for a living. Sure, he played white hats, but he had an intuitive understanding of character and narrative tropes. He played opposite some of the best bad guys in 21st century Hollywood! It wouldn't be hard for him to pull the cloak of acting around himself to do what he initially needed to do to survive. But somewhere along the way, the tough, ruthless persona he adopted stopped being an act and he became his character. He embodied the answer to the question posed by The Man from Deadhorse: what happens when a good man is driven too far?

Cooper Howard adapted to survive. His actions reflect the realities of being a ghoul (again, a people generally reviled by everyone and cast out of safe havens because they are deemed threats). Pragmatic and efficient violence are necessities if a ghoul wants to live long, stay sane, and stay out from under the thumb of would-be enslavers. Still, beneath it all, Cooper Howard is still there, buried deep down beneath the character-persona of The Ghoul.

The Ghoul is drawn to Lucy (platonically, romantically, or some secret third thing), to her goodness and old-world manners just as much as he is disgusted/irritated by them. She's an echo of himself, of Cooper Howard, of who he used to be, and he knows EXACTLY where that gets a person. She's going to get herself killed if she doesn't wise up. With those high-and-mighty, anachronistic principles, that black-and-white worldview, her totally naive misunderstanding of the realities of the Wasteland, she won't last long. And initially he sees her as a pawn, like he was, only good for moving him one step closer to his goal. But then she shows him she can adapt and survive. Not only that, she can be true to her core principles in the process. She can conduct herself with dignity. Lucy reminds him what it was like being the white hat, and shows him that yes, even in this hellscape, there can be heroes. Over 200 yeas, his pragmatism and need to survive sanded away the nuance between Good and Bad. But Lucy makes him reconsider whether maybe there is right and wrong after all, and maybe it actually does matter.

Thus begins his transformation, but the change is not immediate, and this is still the Wasteland. He escapes from The Govermint and goes after Lucy. To do that, he needs to find Moldaver. He tracks down someone who might know where to find her, kills him and accidentally blows a hole through the letter with the key bit of information he needs to find Moldaver. So, he goes to that guy's family to find the man's younger brother, Tommy. When he gets the information he needs, he kills Tommy. He gives Tommy the opportunity to back down, but The Ghoul has a lot of experience and reads Tommy like a book. Tommy is not the kind of kid to let something like this go, and The Ghoul has clearly been burned by leaving vengeful people alive before. Tommy reaches for a gun to shoot The Ghoul, and The Ghoul doesn't hesitate. He blows a hole in the kid. It sucks, but again, this is a decision born from sheer practicality, not love of carnage.

Later, he comes across CX-404 trapped in a Nuka-Cola machine (left there by Thaddeus). The head is lost to both of them now; the dog cannot help The Ghoul with finding it. But he saves her anyway and dubs her Dogmeat. He lets sentimentality get to him for the first time in who knows how long and allows himself to bond with another living being. When he does reach The Observatory (where Moldaver, Lucy, and her dad are), he clearly stashes Dogmeat somewhere to keep her out of harm's way and goes in after Lucy.

After fighting his way through the Brotherhood of Steel, we come to that pivotal scene where Lucy finds out about her father's history. Cooper hangs back to observe and learns that his niggling, hare-brained hunch about Lucy and her last name was correct: she was the daughter of Henry MacLean, a man-out-of-time who presents the first real step in 200 years toward Cooper's ultimate goal: finding his family. (I think it's important to note, however, that he isn't 100% sure of her connection to Hank when follows her to Moldaver's--his reasons for going to the Observatory are either to get information from Moldaver or simply to back Lucy up, should she need help). He lets Hank get away so that he can follow him, and he's willing to follow him alone. But now there's Lucy, who is as wrapped up in this shit as Cooper is (even if she doesn't understand it yet), and he figures they both deserve answers. She's shown that she can adapt to survive, she just needs a teacher. In their first exchange since she left him at the Super Duper Mart, he treats her with new respect and offers her the opportunity to come with him, learn from him, and find out about who she really is and the legacy that has produced her. But perhaps he also knows deep down that he needs to learn from her too. He needs to remember what it was like to be good, to be human. He needs it so he can be it for his daughter when he finds her.

So, yeah, I don't know, it's just interesting how Cooper Howard became essentially lost in method acting a villain to survive the fucking awful conditions he found himself in, but even then he isn't cruel. Like, there are a lot worse things he could have done to Lucy. A LOT WORSE. As far as I can tell, he never looks at or touches her in a creepy, predatory way. Yeah, he drags her around on a leash and cuts her finger off when she bites his off, but that's pretty damn tame for the Wasteland. He secures her with rope, but otherwise is pretty hands off with her. If he objectifies her, it's in an extremely non-sexual way. More of a taking-the-cow-to-market kinda way. Which still sucks, but again, it's not needlessly cruel or wantonly violent, which is pretty impressive given general Wasteland behavior.

He's a damn interesting character, and I'm super stoked to see how he develops--and how he interacts with Lucy going forward.

#fallout show#cooper howard#the ghoul#lucy maclean#long post#character analysis#also#have you guys noticed#Cooper is wearing the same hat shirt and trousers he wore when the bomb dropped??#how has he NOT worn out those clothes after 200 years??#how does he take care of them??#Why does he wear them still?#...do you think it's so that when he does find his daughter#she'll be able to recognize *them* even if she doesn't recognize *him*?

36 notes

·

View notes