#green dye in the Victorian era was made of arsenic

Note

Oh yeah in the Victorian era they had wallpapers and dresses made using a dye called Scheele's Green and Paris green. Both beautiful colors. Both very popular. Both made with arsenic. One guest at the royal brittish palace even allegedly died because his room had been freshly wallpapered with the arsenic heavy wallpapers. Then it went downhill in popularity and now our green dye is made differently and much less toxic.

yes!!!! thank you, Anon!

58 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! How about 🌸 and 🙃 for the ask game?

Hello! <3

🙃 What’s a weird fact that you know?

Scheele's Green was a vibrant pigment that was made of an arsenic compound (cupric hydrogen arsenite) that became really popular in the Victorian era. It was used to paint walls, dye clothes, used in children toys, etc. It was really toxic.

🌸 Best compliment you ever received?

I answered this in another ask and it was hard enough to think up one compliment I got, I can't think of another :')

1 note

·

View note

Text

The synthetic revolution’s colour craze led to the exploitation of natural wonders, too, with some horrifying results. One of the exhibition’s curiosities is a necklace made from the heads of hummingbirds, whose iridescent plumage obsessed Victorians. Millions were killed to provide decorations for hats. “A minority realised [the trade’s] devastating impact and formed anti-plumage leagues,” says Winterbottom. “It was women mobilising other women.”

There was also, inevitably, a backlash against the mass adoption of bright clothing. “Outrageously crude [particularly] among shopkeepers’ wives,” sniffed one 1860s French visitor to England cited in the exhibition catalogue. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood critic John Ruskin praised instead “God-given” colours while William Morris talked up the faded beauty of expensive organic dyes and initiated a trend among the haute bourgeoisie for muted tones. Yet while the brotherhood themselves advocated natural pigments, the exhibition shows that even in their stridently medievalist works, they used chemical greens.

This tension between nature and artifice fuelled some intriguing cultural shifts, with later generations intentionally overturning traditional colour symbolism and embracing forbidden hues. Of all Victorian Britain’s colour fads, green was the most controversial. By the 1860s, new arsenic greens created toxic wallpaper and notoriously caused a young woman who worked with colourful silk flowers to produce green vomit before dying. Two decades later, however, this murky history made green the colour du jour for the decadents – writers and artists who rejected establishment values in favour of a pure aestheticism. Its infamous leading agent provocateur, Oscar Wilde, had a famed green-dyed carnation that cleverly inverted norms and became a queer symbol.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Belladonna in Green by Kelley Hensing

This piece is a reflection of the beautiful but deadly variety. It was inspired by some of the unusual practices of the Victorian era, conducted in the name of fashion and beauty. The first would be her lovely green dress. It may seem surprising, but one of the green dyes of that time era actually contained arsenic. (Poisonous to both the wearer and even more so the maker.) Another feature included are popular toxic plants used during that time, most notably the Belladonna flower. Also known as deadly nightshade, ladies would have used it to enlarge their pupils, which they felt made them more attractive. (Interestingly, this ingredient is still sometimes utilized by optometrists for eye exams.) In addition, arsenic and other toxins readily available back then became a devious method of using poisons against their foes. (Thus reflected in the shadowy eyes hiding in the dress folds.)

Medium: oil on wood panel

Frame: vintage, oval gold wood (has some minor chips/wear)

size: art 9.5 x 21, with frame 14 x 25 inches (last pic shows hand for scale)

VIEW DETAILS brought to you by Every Day Original

0 notes

Text

The dance of death: an au in which Phil and Kristin are two immortal grim reapers who really enjoy their jobs, and also adopt a few random kids along the way

#Imma talk about some historical notes now#because I’m a nerd#so the first one is Stuart#philza a plague doctor#because bird#Kristin is a noble women#the second one is victorian#Kristin is wearing black because so many people died that people were just constantly grieving#very fitting for grim reapers#phils wearing green#fun fact#green dye in the Victorian era was made of arsenic#3rd is 20s#4th is 50s#5th is 80s#6th is current obvi#I imagine they adopt techno some time during the French Revolution#and Wilbur in like the 1930s#tommy is just a random orphan from the 2000s#philza fanart#dsmp#dreamsmp#art#mcyt#mumza#philza#philza Minecraft seems like a double denim man#dod au

12K notes

·

View notes

Photo

I keep saying I’m going to make nice illustrations for my Portfolio, but I keep doing STUFF LIKE THIS.

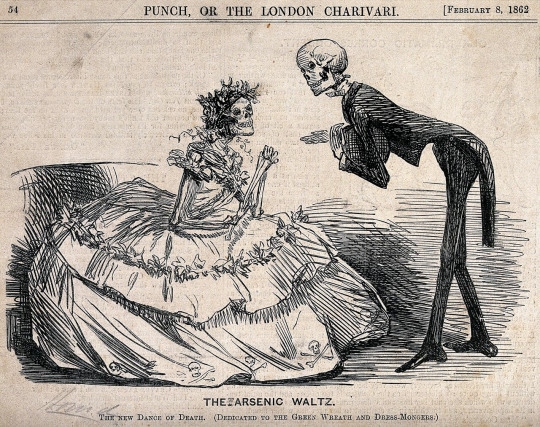

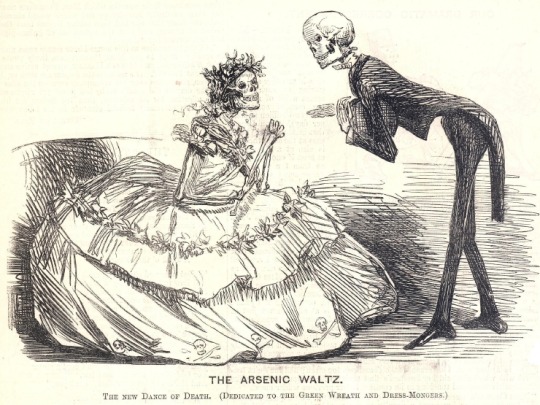

I was reading back up on the ‘Emerald Green’ Phase of the Victorian Era where the color green got super popular. However, because of poor worker conditions, a lot of people suffered from ARSENIC POISONING. Even people who bought green clothes or used green wallpaper would get really sick. One of the most renowned cases was the death of 19 year old Mary Shuerer whose job it was to apply the green dye to fake flowers. Her eye whites turned green, she vomited green and her last words were that ‘Everything Looked Green’ It was only after that that investigations were looked into these factories (as a lot of the women working there were just covered in Arsenic burns) and public awareness was made about how dangerous using things with this dye were with these fasinating ads often featuring skeletons

The color was known as ‘Arsenic Green’ (orginally called Scheele’s Green) and actually contributed to the death of Napoleon whose prison home on the isle of St Helena was painted on the inside, his favorite color; Green.

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Steampunk Ashido Mina this time! Based off the newest popularity poll

She’s an exterminator of….pests? People? Who can say. But all her clothes are dyed with arsenic and she is immune to most caustic materials. Watch out!

I’ll admit I don’t have as solid a role for her as a member of an airship crew but I knew I wanted her toting around caustic chemicals and wearing bright green. Paris green, a toxic dye made with arsenic, was all the rage in the Victorian era despite it’s pesky habit of causing lesions, paralysis, and death. This chartreuse is more toned down than most arsenic green stuff was, because it works better with the steampunk vibe, but the spirit of it is there!

Sero

140 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I really hate to disappoint everyone, but Victorians weren’t killing themselves by wearing green dresses made with arsenic-based dye. It’s one of the most persistent and annoying misconceptions about Victorian fashion and it was mentioned on this week’s My Favorite Murder.

Two very specific shades of green were made with arsenic-based pigments, apple green Scheele’s green and emerald green Paris green, seen above. So if you see an extant green Victorian dress, don’t just assume it’s arsenic. In fact, I haven’t been able to find a single extant green dress that’s confirmed to have been dyed with arsenic, so Pinterest is lying to you.

Secondly, you can’t kill yourself by wearing arsenic-based dye. The worst you can do is wear really really tight green gloves and give yourself blisters where the fabric rubs against the skin. Seriously that’s it.

HOWEVER, if you are working with this arsenic dye and putting your hands in it hundreds of times per day, day in and day out, that’s a different story. So we all know that it pretty much sucks to be an industrial worker in the Victorian era, and this is yet another iteration of it. Green dye’s toxic connotation is a result of the ill and often deadly effects that were felt by textile workers who worked with this dye, usually in the making of silk flower stems. Because of how bad it was for workers, the use of Scheele’s green and Paris green quickly went out of fashion and other non-toxic green dyes were used. Painters, however, continued to use both shades of green in their art, so most remaining examples of it comes from artist’s pigments.

606 notes

·

View notes

Text

still thinking about those victorian era green dresses made with arsenic dye

544 notes

·

View notes

Note

If it's not mercury making the Hatter loopy, it's got to be arsenic. He's got a bright green hat a green jacket. In the Victorian Era, the dye for those would have been made of arsenic and copper. It's possible there's lead chromate in his jacket, too, since it's more yellow.

Very, very likely.

Back in those days, chemical effects weren't as well known to the degree they are these days, and oh my geezy the stuff people breathed in and rubbed in thier skin will make your hair curl. And this was touted as cosmetic wonders!

And, oh, can you imagine what it was like back in those times when people didn't know what was happening there??

I just wasn't prepared for Disney to just drop that this familiar faced lovable loon-

- apparently tries to peel himself like a banana on a regular basis.

Ah, there's that good old underlying fridge horror of the classic Disney properties we've come to know and love.

Oh, you poor, funky little haberdasher

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

HISTORY OF MAKEUP

In order to understand the constantly changing trends in cosmetics, it is interesting to take a look at the evolution of makeup. Women and men have been wearing cosmetics for centuries, although the styles have certainly undergone some dramatic changes over time. Let’s take a look at how cosmetics evolved.

The earliest historical record of makeup comes from the 1st Dynasty of Egypt (c.3100-2907 BC). Tombs from this era have revealed unguent jars, which in later periods were scented. Unguent was a substance extensively used by men and women to keep their skin hydrated and supple and to avoid wrinkles from the dry heat. The women of Egypt also decorated their eyes by applying dark green color to the under lid and blackening the lashes and the upper lid with kohl, which was made from antimony (a metallic element) or soot. It is believed that the Jews adopted the use of makeup from the Egyptians, since references to the painting of faces appear in the New Testament section of the Bible.

Roman philosopher Plautus (254-184 BC) wrote, “A woman without paint is like food without salt.” Of course, Plautus was a dramatist, which would explain his preference for the look of a “painted woman” at that time.

Romans widely used cosmetics by the middle of the 1st century AD. Kohl was used for darkening eyelashes and eyelids, chalk was used for whitening the complexion, and rouge was worn on the cheek. Depilatories were utilized at that time and pumice was used for cleaning the teeth.

Women wore white lead and chalk on their faces in Greco-Roman society. Persian women used henna dyes to stain their hair and faces with the belief that these dyes enabled them to summon the majesty of the earth.

During the European middle ages, pale skin was a sign of wealth. Sixth century women sought drastic measures to achieve that look by bleeding themselves, although, in contrast, Spanish prostitutes wore pink makeup. Thirteenth century affluent women donned pink lipstick as proof they could afford synthetic makeup.

During the Italian Renaissance, lead pain was used to lighten the face, which was very damaging to the wearer. Aqua Toffana was a popular face powder named for its creator, Signora Toffana. Made from arsenic, Signora Toffana instructed her rich clientele to apply the makeup only when their husbands were around. It’s interesting to note that Tofana was executed some six hundred dead husbands later.

Cosmetics were seen as a health threat in Elizabethan England, although women wore egg whites over their faces for a glazed look.

During the reign of Charles II, heavy makeup began to surface as a means to contradict the pallor from being inside due to illness epidemics.

During the French Restoration in the 18th century, red rouge and lipstick were used to give the impression of a healthy, fun-loving spirit.

Eventually, people in other countries became repulsed by excessive makeup and claimed the “painted” French had something to hide.

During the Regency era, the most important item was rouge, which was used by most everyone. At that time, eyebrows were blackened and hair was dyed. To prevent a low hairline, a forehead bandage dipped in vinegar in which cats dung had been steeped was worn. Most of the country dwellers’ makeup recipes made use of herbs, flowers, fat, brandy, vegetables, spring water and, of course, crushed strawberries. During this era, white skin signified a life of leisure while skin exposed to the sun indicated a life of outdoor labor. In order to maintain a pale complexion, women wore bonnets, carried parasols, and covered all visible parts of their bodies with whiteners and blemish removers. Unfortunately, more than a few of these remedies were lethal.

The most dangerous beauty aids during this time were white lead and

mercury. They not only eventually ruined the skin but also caused hair loss, stomach problems, the shakes, and could even cause death. Although these dangers became known through the death of courtesan Kitty Fisher, the majority of women continued to use these deadly whiteners.

During the 1800’s, women would use belladonna to make their eyes appear more luminous, even though they were aware it was poisonous. Many cosmetics were made by local pharmacists, known as apothecaries in England, and common ingredients included mercury and nitric acid. Hair dye was made from coal tar, which is now illegal in America.

It might interest you to know that men wore makeup until the 1850’s. George IV spent a fortune on cold cream, powders, pastes, and scents. However, not all men wore makeup, as many looked upon a man with rouged cheeks as a dandy.

Here are some beauty-tip recipes utilized during the late 1800’s:

*For freckle removal: bruise and squeeze the juice out of chick-weed, add three times its quantity of soft water, then bathe the skin for five to ten minutes morning and evening.

*As a wash for the complexion: one teaspoon of flour of sulphur and a wine glassful of lime water, well shaken and mixed with half a wine-glass of glycerine and a wine-glass of rose-water. Rub on the face every night before going to bed.

*To keep hair from turning gray: four ounces of hulls of butternuts were infused with a quart of water, to which half an ounce of copperas was added. This was to be applied with a soft brush every two to three days.

*For wrinkle removal: melt one ounce of white wax, add two ounces of juice of lily-bulbs, two ounces of honey, two drams of rose-water, and a drop or two of ottar of roses and use twice a day.

Victorians abhorred makeup and associated its use with prostitutes and actresses (many considered them one and the same). Any visible hint of tampering with one’s natural color would be looked upon with disdain. At that time, a respectable woman would use home-prepared face masks, most of which were based on foods such as oatmeal, honey, and egg yolk. For cleansing, rosewater or scented vinegars were used. As a beauty regimen, a woman would pluck her eyebrows, massage castor oil into her eyelashes, use rice powder to dust her nose, and buff her nails to a shine. Lipstick was not used, but clear pomade would be applied to add sheen. However some of these products contained a dye to discretely enhance natural lip color. For a healthy look, red beet juice would be rubbed into the cheeks, or the cheeks would be pinched (out of sight, of course). For bright eyes, a drop of lemon juice in each eye would do the trick. When makeup began to resurface, full makeup was still seen as sinful, although natural tones were accepted to give a healthy, pink-cheek look.

The real evolution actually began during the 1910’s. By then, women made their own form of mascara by adding hot beads of wax to the tips of their eyelashes. Some women would use petroleum jelly for this purpose. The first mascara formulated was named after Mabel, the sister of its creator, T. L. Williams, who utilized this method. This mascara is known today as Maybelline. In 1914, Max Factor introduced his pancake makeup. Vogue featured Turkish women using henna to outline their eyes, and the movie industry immediately took interest. This technique made the eyes look larger, and the word “vamp” became associated with these women, vamp being short for vampire.

During this decade, the first pressed powders were introduced which included a mirror and puff for touchups. Pressed powder blush followed soon after. The lipstick metal case, invented by Maurice Levy, became popular. Also, during this time, lipstick was tattooed onto the lips by George Burchett, who was also known as the “Beauty Doctor”. This method did not always work, and you can imagine the terrible consequences.

The earliest version of an acid peel was utilized at this time, which was a combination of acid and electric currents applied to the skin. Also, a needle would be used to insert paraffin to the eye area and cheeks, although this, too, was not very successful. Nivea cream made its appearance in Germany, and companies, in order to compete, began creating creams consisting of Vaseline mixed with fragrance.

To help with sagging jowls and double-chins, women could purchase for wear a weird-looking contraption with chin straps, which obviously did not work.

However, the Victorian look remained in fashion until mass makeup marketing came about during the 1920’s. The newly emancipated woman of America began to display her independence by free use of red lipstick, which was often scented with cherry. By the late ’20’s, visible makeup was considered a must by rural women but was still frowned upon by the country girls. During this decade, lip gloss was introduced by Max Factor. New shades of red lipstick were developed, although were soap-based and very drying. The first eyelash curler came on the scene, called Kurlash. Even though it was expensive and difficult to use, this did not detract from its popularity. Mascara in cake and cream form was extremely vogue.

From the 1930’s through the 1950’s, various movie stars proved to be the models for current trends in makeup. Remember Audrey Hepburn’s deeply outlined cat eyes? With the ’60’s and the hippies came a more liberated makeup look, from white lips and Egyptian-lined eyes to painted images on faces. Heavily lined eyes continued through the ’70’s and ’80’s with a wide range of eye shadow colors. Today’s trend seems to have reverted to the more natural look with a blending of styles from the past.

In today’s world, a woman has literally hundreds of cosmetics to choose from, with a wide variety of colors and uses. For a younger look, the options available are as simple as skin hydrators and rejuvenators, advancing to chemical skin peels, the now-popular Botox, collagen injections, and ending with the more-drastic surgical facelift.

It is important to reflect on one’s inner beauty as the real beauty of a woman. Outer beauty will not remain forever, no matter what drastic measures are taken. We have all heard the saying, “The eyes are the windows to the soul”. Look into your own orbits, take stock of the woman inside, and be happy with who you are. This will reflect on your outlook on life, which will send a message to others, and will be returned to you through their reactions to the beautiful you.

0 notes

Video

(via https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=372LqnyuGaY)

Hey everybody! Video day! Today’s video is all about the deadly green dye made with arsenic during the Victorian era. Warning: if you do not like talk of open wounds or sores this may not be a good video for you. Be sure to like, comment, and subscribe!

#fun facts#arsenic dye#working conditions#victorian era#video#my video#deadly consequences#open wounds#sores#violent death#youtube video#like comment and subscribe

0 notes

Photo

Any of you lovers of green? In Victorian Era, vibrant greens were made using dyes, including arsenic. Owners of green were not at risk, but the fabric dyers, none of who wore protective anything at the time, were constantly absorbing arsenic through their skin. #omg #historicshoes #historicfashion #fashionvictims #fashionvictim #fashion #oldfashion #victorian #victorianfashion #greenfashion #arsenic #deathbyfashion #fashiondeath #deathbyarsenic #fashionisdangerous #arsenicisdangerous #arsenicispoisonous beautifulgreen #emeraldgreen #emerald #ilovegreen #museum #fashionmuseum #fashionhistorymuseum #shoemuseum #fashionanthropology (at Bata Shoe Museum)

#fashiondeath#greenfashion#arsenicisdangerous#fashionanthropology#shoemuseum#historicshoes#historicfashion#arsenic#fashionvictims#deathbyarsenic#emerald#ilovegreen#oldfashion#fashionmuseum#victorianfashion#omg#deathbyfashion#fashionhistorymuseum#fashionvictim#emeraldgreen#arsenicispoisonous#fashionisdangerous#museum#victorian#fashion

1 note

·

View note