#library at Herculaneum

Photo

Ancient Herculaneum Scrolls Blackened by Vesuvius are now Readable

X-ray scans can just tease out letters on the warped documents from a library at Herculaneum.

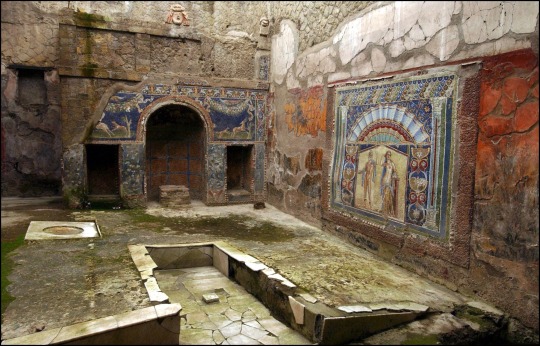

The lavish villa sat overlooking the Bay of Naples, offering bright ocean views to the well-heeled Romans who came from across the empire to study. The estate's library was stocked with texts by prominent thinkers of the day, in particular a wealth of volumes by the philosopher Philodemus, an instructor of the poet Virgil.

But the seaside library also sat in the shadow of a volcano that was about to make terrible history.

The 79 A.D. eruption of Mount Vesuvius is most famous for burying Pompeii, spectacularly preserving many artifacts—and residents—in that once bustling town south of Naples. The tumbling clouds of ash also entombed the nearby resort of Herculaneum, which is filled with its own wonders. During excavations there in 1752, diggers found a villa containing bundles of rolled scrolls, carbonized by the intense heat of the pyroclastic flows and preserved under layers of cement-like rock. Further digs showed that the scrolls were part of an extensive library, earning the structure the name Villa of the Papyri.

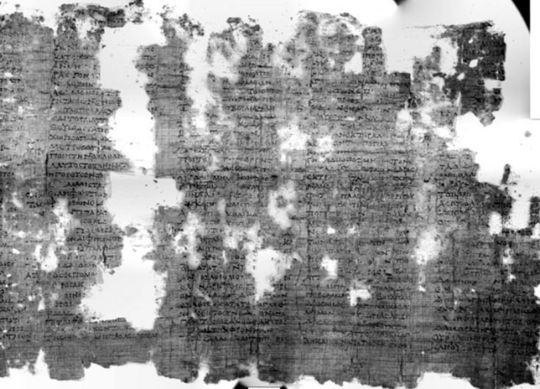

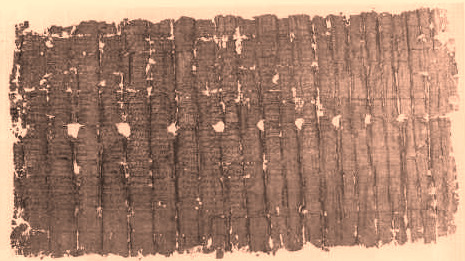

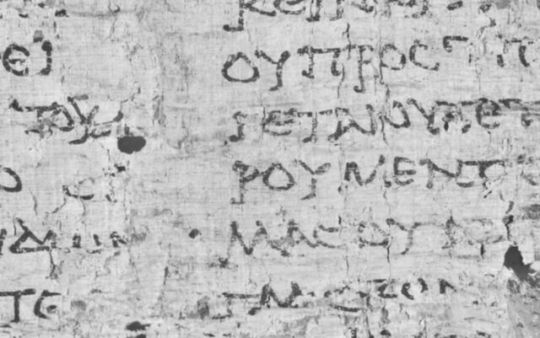

Blackened and warped by the volcanic event, the roughly 1,800 scrolls found so far have been a challenge to read. Some could be mechanically unrolled, but hundreds remain too fragile to make the attempt, looking like nothing more than clubs of charcoal. Now, more than 200 years later, archaeologists examining two of the scrolls have found a way to peer inside them with x-rays and read text that has been lost since antiquity.

"Anybody who focuses on the ancient world is always going to be excited to get even one paragraph, one chapter, more," says Roger Macfarlane, a classicist at Brigham Young University in Utah. "The prospect of getting hundreds of books more is staggering."

Most of the scrolls that have been unwrapped so far are Epicurean philosophical texts written by Philodemus—prose and poetry that had been lost to modern scholars until the library was found. Epicurus was a Greek philosopher who developed a school of thought in the third century B.C. that promoted pleasure as the main goal of life, but in the form of living modestly, foregoing fear of the afterlife and learning about the natural world. Born in the first century B.C. in what is now Jordan, Philodemus studied at the Epicurean school in Athens and became a prominent teacher and interpreter of the philosopher's ideas.

Modern scholars debate whether the scrolls were part of Philodemus' personal collection dating to his time period, or whether they were mostly copies made in the first century A.D. Figuring out their exact origins will be no small feat—in addition to the volcano, mechanical or chemical techniques for opening the scrolls did their share of damage, sometimes breaking the delicate objects into fragments or destroying them outright. And once a page was unveiled, readability suffered.

"Ironically, when someone opened up a scroll, they would write on a separate sheet what they could read, like a facsimile, and the original ink, once exposed to air, would start to fade," says Brent Seales, a computer scientist at the University of Kentucky who specializes in digital imaging. What's more, the brute-force techniques usually left some pages stuck together, trapping hidden layers and their precious contents.

From 2007 to 2012, Seales collaborated with Daniel Delattre at the French National Center for Scientific Research in Paris on a project to scan scrolls in the collections of the Institut de France—former treasures of Napoleon Bonaparte, who received them as a gift from the King of Naples in 1802. Micro-CT scans of two rolled scrolls revealed their interior structure—a mass of delicate whorls akin to a fingerprint. From that data the team estimated that the scrolls would be between 36 and 49 feet long if they could be fully unwound. But those scans weren't sensitive enough to detect any lettering.

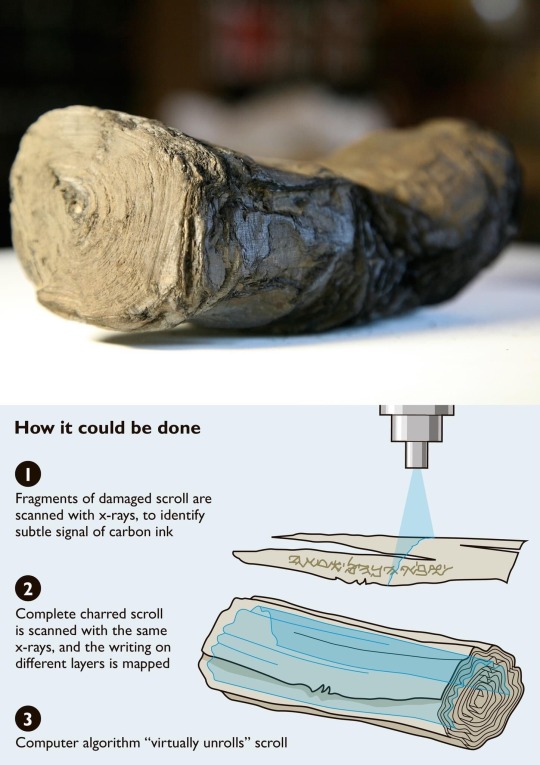

The trouble is that papyri at the time were written using a carbon-based ink, making it especially hard to digitally tease out the words on the carbonized scrolls. Traditional methods like CT scans blast a target with x-rays and look for patterns created as different materials absorb the radiation—this works very well when scanning for dense bone inside soft tissue (or for peering inside a famous violin), but the method fails at discerning carbon ink on blackened scrolls.

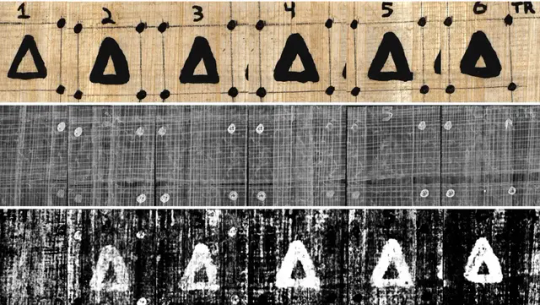

Now a team led by Vito Mocella of the Italian National Research Council has shown for the first time that it is possible to see letters in rolled scrolls using a twist on CT scanning called x-ray phase-contrast tomography, or XPCT. Mocella, Delattre and their colleagues obtained permission to take a fragment from an opened scroll and a whole rolled scroll from the Paris institute to the European Synchrotron in Grenoble. The particle collider was able to produce the high-energy beam of x-rays needed for the scans.

Rather than looking for absorption patterns, XPCT captures changes in the phase of the x-rays. The waves of x-rays move at different speeds as they pass through materials of various density. In medical imaging, rays moving through an air-filled organ like a lung travel faster then those penetrating thick muscle, creating contrast in the resulting images. Crucially, the carbon-based ink on the scrolls didn't soak into the papyrus—it sits on top of the fibers. The microscopic relief of a letter on the page proved to be just enough to create a noticeable phase contrast.

Reporting today in the journal Nature Communications, Mocella and his team show that they were able to make out two previously unreadable sequences of capital letters from a hidden layer of the unrolled scroll fragment. The team interprets them as Greek words: ΠΙΠΤΟΙΕ, meaning "would fall", and ΕΙΠΟΙ, meaning "would say". Even more exciting for scholars, the team was able to pick out writing on the still-rolled scroll, eventually finding all 24 letters of the Greek alphabet at various points on the tightly bundled document.

Even though the current scans are mostly a proof of concept, the work suggests that there will soon be a way to read the full works on the rolled scrolls, the team says. "We plan to improve the technique," says Mocella. "Next spring we have an allowance to spend more time at the Grenoble synchrotron, where we can test a number of approaches and try to discern the exact chemical composition of the ink. That will help us improve the energy setting of the beam for our scan."

"With the text now accessible by virtue of specialized images, we have the prospect of going inside the rolled scrolls, and that's really exciting," says Macfarlane. Seales agrees: "Their work is absolutely crucial, and I am delighted to see a way forward using phase contrast."

Seales is currently working on ways to help make sense of future scans. With support from the National Science Foundation and Google, Seales is developing software that can sort through the jumbled letters and figure out where they belong on the scroll. The program should be able to lump letters into words and fit words into passages. "It turns out there are grains of sand sprinkled all the way through the scrolls," says Seales. "You can see them twinkling in the scans, and that constellation is fixed." Using the sand grains like guide stars, the finished software should be able to orient the letters on the whorled pages and line up multiple scans to verify the imagery.

The projects offer hope for further excavations of the Herculaneum library. "They stopped excavating at some point for various reasons, and one was, Why should we keep pulling things out if they are so hard to read?" says Seales. But many believe there is a lower "wing" of the villa's collection still buried, and it may contain more 1st-century Latin texts, perhaps even early Christian writings that would offer new clues to Biblical times.

"Statistically speaking, if you open up a new scroll of papyrus from Herculaneum, it's most likely going to be a text from Philodemus," says MacFarlane. "But I'm more interested in the Latin ones, so I would not be unhappy at all to get more Latin texts that are not all banged up."

For Mocella, being able to read even one more scroll is crucial for understanding the library and the workings of a classical school of philosophy. "Regardless of the individual text, the library is a unique cultural treasure, as it is the only ancient library to survive almost entire together with its books," he says. "It is the library as whole that confers the status of exceptionality."

The scanning method could also be useful for texts beyond the Roman world, says Seales. Medieval books often cannibalized older texts to use as binding, and scans could help uncover interesting tidbits without ruining the preserved works. Also, letters and documents from the ill-fated Franklin expedition to the Northwest Passage in the 19th century have been recovered but are proving difficult to open without doing damage. "All that material could benefit from non-invasive treatment," says Seales.

By Victoria Jaggard.

#Ancient Herculaneum Scrolls Blackened by Vesuvius are now Readable#library at Herculaneum#Mount Vesuvius#The Villa of the Papyri#archeology#archeolgst#ancient scrolls#ancient artifacts#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman literature#long reads

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

Escapades in Italy

#dark academia#dark acadamia aesthetic#literature#light academia#academic#books and libraries#travel#travelling#travelblr#italytrip#southern italy#napels#aesthetic#herculaneum#roman mythology#ancient rome

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s so hard to articulate just how excited I am about the Herculaneum papyri. Like, if you’ve ever been there it’s a place that feels so fucking eerie. It’s incredibly well preserved and I loved seeing everything, but I also had to step out early because I was feeling so emotional just being there. The fact that we are going to be able to experience this collection is mind blowing and also just another reminder of the frozen state of a ghost town.

#like there are second floors mostly intact there it’s incredible#I stood on the path looking over the town and tbh I almost wept#it’s just a place that inspires such incredible emotion I cannot wait to see what was this person’s library#text#classics#Herculaneum papyri

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Herculaneum papyri are more than 1800 papyri that were carbonized by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius (79 CE), constituting the only surviving library from antiquity that exists in its entirety. Now using new x-ray technique, these scrolls are being read for the first time in millennia

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

Virtual reconstruction made by Virtual Archaeological Museum, and Comitato Cininnato Pompei.

Atrium. House of the Faun, Pompeii .

Library and peristyle of Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum.

House of the Labyrinth, Pompeii.

Beautiful

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

banana circle to summon texts from the herculaneum papyrus library

🍌🍌🍌🍌🍌🍌

🍌 🍌

🍌 euripides' antigone 🍌

🍌 🍌

🍌🍌🍌🍌🍌🍌🍌

530 notes

·

View notes

Text

shaking that guy who had the herculaneum library really really hard by the shoulders . please please please please please have a copy of all the things i personally want to read. youre nothing

418 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Herculaneum papyri, ancient scrolls housed in the library of a private villa near Pompeii, were buried and carbonized by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. For almost 2,000 years, this lone surviving library from antiquity was buried underground under 20 meters of volcanic mud. In the 1700s, they were excavated, and while they were in some ways preserved by the eruption, they were so fragile that they would turn to dust if mishandled. How do you read a scroll you can’t open? For hundreds of years, this question went unanswered.

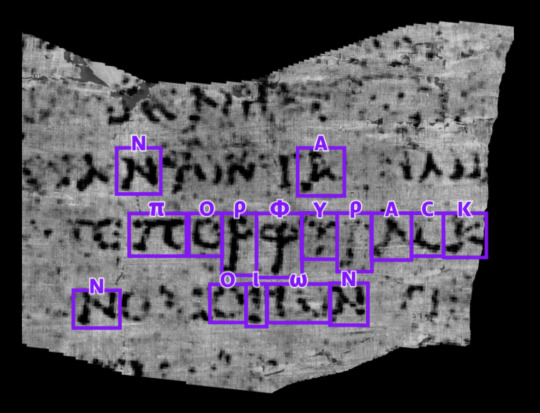

That is until Luke Farritor, a contestant of the Vesuvius Challenge, became the first person in two millennia to see an entire word from within an unopened scroll this August.

Shortly after that, another contestant, Youssef Nader, independently discovered the same word in the same area, with even clearer results — winning the second place prize of $10,000.

Indeed, the word held up to scrutiny. “Porphyras” is an exciting word: it means “purple” and is quite rare in ancient texts.

One papyrologist noted: “The sequence πορφυ̣ρ̣ας̣ may be πορφύ̣ρ̣ας̣ (noun, purple dye or cloths of purple) or πορφυ̣ρ̣ᾶς̣(adjective, purple). Due to the lack of context it is not possible to exclude πορφύ̣ρ̣α ς̣κ[ or πορφυ̣ρ̣ᾶ ς̣κ[.”

This is so cool, worth the read if you click through!

394 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Villa of the Papyri,” Herculaneum. The only library from the ancient world whose collection has survived to the present day.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tunneling into the Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum, location of the only library from the ancient world whose collection has survived into the present day.

411 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herculaneum Scrolls Reveal Plato's Burial Place

Researchers used AI to decipher an ancient papyrus that includes details about where Greek philosopher is buried.

The decipherment of an ancient scroll has revealed where the Greek philosopher Plato is buried, Italian researchers suggest.

Graziano Ranocchia, a philosopher at the University of Pisa, and colleagues used artificial intelligence (AI) to decipher text preserved on charred pieces of papyrus recovered in Herculaneum, an ancient Roman town located near Pompeii, according to a translated statement from Italy's National Research Council.

Like Pompeii, Herculaneum was destroyed in A.D. 79 when Mount Vesuvius erupted, cloaking the region in ash and pyroclastic flows.

One of the scrolls carbonized by the eruption includes the writings of Philodemus of Gadara (lived circa 110 to 30 B.C.), an Epicurean philosopher who studied in Athens and later lived in Italy. This text, known as the "History of the Academy," details the academy that Plato founded in the fourth century B.C. and gives details about Plato's life, including his burial place.

Historians already knew that Plato, the famous student of Socrates who wrote down his teacher's philosophies as well as his own, was buried at the Academy, which the Roman general Sulla destroyed in 86 B.C. But researchers weren't sure exactly where on the school's grounds that Plato, who died in Athens in 348 or 347 B.C., had been laid to rest.

However, with advances in technology, researchers were able to employ a variety of cutting-edge techniques including infrared and ultraviolet optical imaging, thermal imaging and tomography to read the ancient papyrus, which is now part of the collection at the National Library of Naples.

So far, researchers have identified 1,000 words, or roughly 30% of the text written by Philodemus.

"Among the most important news, we read that Plato was buried in the garden reserved for him (a private area intended for the Platonic school) of the Academy in Athens, near the so-called Museion or sacellum sacred to the Muses," researchers wrote in the statement. "Until now it was only known that he was buried generically in the Academy."

The text also detailed how Plato was "sold into slavery" sometime between 404 and 399 B.C. (It was previously thought that this occurred in 387 B.C.)

Another part of the translated text describes a dialogue between characters, in which Plato shows disdain for the musical and rhythmic abilities of a barbarian musician from Thrace, according to the statement.

This isn't the first time that researchers have used AI to read ancient scrolls that survived Mount Vesuvius's eruption. Earlier this year, researchers deciphered a different scroll that was charred during the volcanic eruption at a nearby villa that once belonged to Julius Caesar's father-in-law.

By Jennifer Nalewicki.

#Plato#Herculaneum Scrolls Reveal Plato's Burial Place#Herculaneum#Pompeii#Philodemus of Gadara#History of the Academy#The Academy#Plato's Academy#the Platonic Academy#the Academic School#athens greece#mount vesuvius#roman dictator sulla#ancient texts#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient greece#greek history#roman history#roman empire

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

800 new deciphered classical texts about to drop, thanks to volcano

So when Vesuvius erupted and buried Pompeii, it also buried the nearby town of Herculaneum, which contained a library of papyrus scrolls, about 800 of which were recovered. Being carbonised preserved them from the fragility papyrus normally exhibits anywhere wetter than Egypt, but also presented a new problem: You can't unroll them without disintegrating them, so how do you read them?

Well, these days we have Technology that emits Particles, and someone just won a prize for figuring out how to read the scrolls with CT scanning:

Youssef Nader, Luke Farritor, and Julian Schilliger demonstrated their technique by translating the end of one of the scrolls, which turned out to be an Epicurean discourse on material pleasures, words not read for almost 2,000 years:

...as too in the case of food, we do not right away believe things that are scarce to be absolutely more pleasant than those which are abundant[...]Such questions will be considered frequently.

In the closing section of the text our author takes a parting shot at his adversaries, who “have nothing to say about pleasure, either in general or in particular, when it is a question of definition.” Finally the scroll concludes: “… for we do [not] refrain from questioning some things, but understanding/remembering others. And may it be evident to us to say true things, as they might have often appeared evident!”

The process is currently time-consuming, hence the small amount of text translated now, but the organisers hope to improve its efficiency now they have a workable method, and aim to have mostly-complete translations of a handful of scrolls within the next year.

Safe to say everyone who works in a field with a holy-grail lost classical text they'd resigned themselves to never being able to read is crossing their fingers right now!

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Herculaneum papyri, ancient scrolls housed in the library of a private villa near Pompeii, were buried and carbonized by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. For almost 2,000 years, this lone surviving library from antiquity was buried underground under 20 meters of volcanic mud. In the 1700s, they were excavated, and while they were in some ways preserved by the eruption, they were so fragile that they would turn to dust if mishandled. How do you read a scroll you can’t open? For hundreds of years, this question went unanswered.

That is until Luke Farritor, a contestant of the Vesuvius Challenge, became the first person in two millennia to see an entire word from within an unopened scroll this August. For that, we are thrilled to award Luke a $40,000 First Letters Prize, which required contestants to find at least 10 letters in a 4 cm2 area in a scroll.

LET'S FUCKING GOOOOOOOO

Shortly after that, another contestant, Youssef Nader, independently discovered the same word in the same area, with even clearer results — winning the second place prize of $10,000.

The word is πορφύ̣ρ̣ας̣ (porphyras, meaning "purple").

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

i need to get so much better at reading greek and latin so that if they recover anything i'm desperate for from the herculaneum library i can read it without waiting for commentaries or translations or anything

#mod felix#tagamemnon#like okay yeah i *can* read greek and latin but it's slow and i'm frequently wrong

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

How do you read a scroll you can’t open?

With lasers!

In 79 AD, Mount Vesuvius erupts and buries the library of the Villa of the Papyri in hot mud and ash

The scrolls are carbonized by the heat of the volcanic debris. But they are also preserved. For centuries, as virtually every ancient text exposed to the air decays and disappears, the library of the Villa of the Papyri waits underground, intact

Then, in 1750, our story continues:

While digging a well, an Italian farm worker encounters a marble pavement. Excavations unearth beautiful statues and frescoes – and hundreds of scrolls. Carbonized and ashen, they are extremely fragile. But the temptation to open them is great; if read, they would more than double the corpus of literature we have from antiquity.

Early attempts to open the scrolls unfortunately destroy many of them. A few are painstakingly unrolled by an Italian monk over several decades, and they are found to contain philosophical texts written in Greek. More than six hundred remain unopened and unreadable.

Using X-ray tomography and computer vision, a team led by Dr. Brent Seales at the University of Kentucky reads the En-Gedi scroll without opening it. Discovered in the Dead Sea region of Israel, the scroll is found to contain text from the book of Leviticus.

This achievement shows that a carbonized scroll can be digitally unrolled and read without physically opening it.

But the Herculaneum Papyri prove more challenging: unlike the denser inks used in the En-Gedi scroll, the Herculaneum ink is carbon-based, affording no X-ray contrast against the underlying carbon-based papyrus.

To get X-rays at the highest possible resolution, the team uses a particle accelerator to scan two full scrolls and several fragments. At 4-8µm resolution, with 16 bits of density data per voxel, they believe machine learning models can pick up subtle surface patterns in the papyrus that indicate the presence of carbon-based ink

In early 2023 Dr. Seales’s lab achieves a breakthrough: their machine learning model successfully recognizes ink from the X-ray scans, demonstrating that it is possible to apply virtual unwrapping to the Herculaneum scrolls using the scans obtained in 2019, and even uncovering some characters in hidden layers of papyrus

On October 12th: the first words have been officially discovered in the unopened Herculaneum scroll! The computer scientists won 40,000 dollars for their work and have given hope that the 700,000 grand prize is within reach: to read an entire unwrapped scroll!

The grand prize: first team to read a scroll by December 31, 2023

#vesuvius#Vesuvius challenge#papyrus#ancient rome#ancient greece#x ray tomography#machine learning#computer vision

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two thousand years ago, a volcanic eruption buried an ancient library of papyrus scrolls now known as the Herculaneum Papyri.

In the 18th century the scrolls were discovered. More than 800 of them are now stored in a library in Naples, Italy; these lumps of carbonized ash cannot be opened without severely damaging them. But how can we read them if they remain rolled up?

On March 15th, 2023, Nat Friedman, Daniel Gross, and Brent Seales launched the Vesuvius Challenge to answer this question. Scrolls from the Institut de France were imaged at the Diamond Light Source particle accelerator near Oxford. We released these high-resolution CT scans of the scrolls, and we offered more than $1M in prizes, put forward by many generous donors.

A global community of competitors and collaborators assembled to crack the problem with computer vision, machine learning, and hard work.

Less than a year later, in December 2023, they succeeded. Finally, after 275 years, we can begin to read the scrolls.

Grand Prize

There was one submission that stood out clearly from the rest. Working independently, each member of our team of papyrologists recovered more text from this submission than any other. Remarkably, the entry achieved the criteria we set when announcing the Vesuvius Challenge in March: 4 passages of 140 characters each, with at least 85% of characters recoverable. This was not a given: most of us on the organizing team assigned a less than 30% probability of success when we announced these criteria! And in addition, the submission includes another 11 (!) columns of text — more than 2000 characters total.

The results of this review were clear and unanimous: the Vesuvius Challenge Grand Prize of $700,000 is awarded to a team of three for their excellent submission. Congratulations to Youssef Nader, Luke Farritor, and Julian Schilliger!

Runners up

Of the remaining submissions, the scores from our team of papyrologists identify a three-way tie for runner up. These entries show remarkably similar readability to each other, but still stand out from the rest by being significantly more readable. Congratulations to the following teams, each taking home $50,000!

Shao-Qian Mah. GitHub

Elian Rafael Dal Prá, Sean Johnson, Leonardo Scabini, Raí Fernando Dal Prá, João Vitor Brentigani Torezan, Daniel Baldin Franceschini, Bruno Pereira Kellm, Marcelo Soccol Gris, and Odemir Martinez Bruno. GitHub

Louis Schlessinger and Arefeh Sherafati. GitHub

What does the scroll say?

To date, our efforts have managed to unroll and read about 5% of the first scroll. Our eminent team of papyrologists has been hard at work and has achieved a preliminary transcription of all the revealed columns. We now know that this scroll is not a duplicate of an existing work; it contains never-before-seen text from antiquity. The papyrology team are preparing to deliver a comprehensive study as soon as they can. You all gave them a lot of work to do! Initial readings already provide glimpses into this philosophical text. From our scholars:

The general subject of the text is pleasure, which, properly understood, is the highest good in Epicurean philosophy. In these two snippets from two consecutive columns of the scroll, the author is concerned with whether and how the availability of goods, such as food, can affect the pleasure which they provide.

Do things that are available in lesser quantities afford more pleasure than those available in abundance? Our author thinks not: “as too in the case of food, we do not right away believe things that are scarce to be absolutely more pleasant than those which are abundant.” However, is it easier for us naturally to do without things that are plentiful? “Such questions will be considered frequently.”

Since this is the end of a scroll, this phrasing may suggest that more is coming in subsequent books of the same work. At the beginning of the first text, a certain Xenophantos is mentioned, perhaps the same man — presumably a musician — also mentioned by Philodemus in his work On Music.

Richard Janko writes:

“Is the author Epicurus' follower, the philosopher and poet Philodemus, the teacher of Vergil? It seems very likely.

Is he writing about the effect of music on the hearer, and comparing it to other pleasures like those of food and drink? Quite probably.

Does this text come from his four-part treatise on music, of which we know Book 4? Quite possibly: the title should soon become available to read.

Is the Xenophantus who is mentioned the celebrated flute-player, or the man famous in antiquity for being unable to control his laughter, or someone else entirely? So many questions! But improvements to the identification of the ink, which can be expected, will soon answer most of them. I can hardly wait.”

Scholars might call it a philosophical treatise. But it seems familiar to us, and we can’t escape the feeling that the first text we’ve uncovered is a 2000-year-old blog post about how to enjoy life. Is Philodemus throwing shade at the stoics in his closing paragraph, asserting that stoicism is an incomplete philosophy because it has “nothing to say about pleasure?” The questions he seems to discuss — life’s pleasures and what makes life worth living — are still on our minds today.

We can expect many more works from Philodemus in the current collection, once we’re able to scale up this technique. But there could be other text as well — an Aristotle dialog, a lost history of Livy, a lost Homeric epic work, a poem from Sappho — who knows what treasures are hidden in these lumps of ash.

50 notes

·

View notes