#rogue heroes

Text

Just learned that Major Mike Sadler died last week on the 4th at 103 years of age. He was the last surviving founding member of the SAS and the last survivor of the Long Range Desert Group. Rest In Peace, legendary sir.

Many of you may have been introduced to his story through Stephen Knight’s SAS: Rogue Heroes

#sad day losing these legends one by one#hardly any that I made friends with over the years remains#ww2#wwii#world war 2#sas: rogue heroes#rogue heroes#long range desert group#mike sadler#hbo war#tom glynn carney#band of brothers#hbo the pacific#the pacific

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

They are dead men...just awaiting confirmation. Like me.

- SAS: Rogue Heroes (2022) (insp.)

#sas rogue heroes#sas: rogue heroes#sasrh#sasrhedit#sasrhaes#myedit#sas aesthetic#my aesthetic#aesthetic edit#sas#rogue heroes#aesthetic#edit aesthetic#sas rogue heroes aesthetic#starkroqers#ladyeowyn

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paddy Mayne ~ In The Desert

#another one#paddy mayne#paddy x eoin#eoin mcgonigal#sas rogue heroes#rogue heroes#poetry#poetry webs

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sofia Boutella

108 notes

·

View notes

Text

This is a book for readers of second world war history who like the Boy’s Own version of the conflict. The cast of characters could have stepped straight from a comic strip story. Yet the men of the SAS were real flesh and blood, “rogue heroes” as the title suggests. The organisation now famous for its derring-do, and as famously secretive, has opened its archive to the historian and journalist Ben Macintyre, so that he can produce the first authorised history of what the SAS did in the war.

Macintyre has made the most of the opportunity. The history needs scarcely any embellishment, though he tells it with flair: the simple facts of SAS activity make the “ripping yarns” of comic book heroes pale by comparison. The organisation was the brainchild of two officers posted to the war in Egypt, David Stirling and John “Jock” Lewes. Stirling was an awkward soldier, hostile to spit-and-polish and authority, charming, fun-loving and irreverent (“layer upon layer of fossilised shit” was how he described military bureaucracy). Bored by life in Cairo, he discussed with the ascetic, hard-working, serious-minded Lewes, his complete opposite in personality, the possibility of creating a unit of awkward men like himself, who wanted action, few rules and adventure in small hit-and-run assaults behind enemy lines. Astonishingly, Stirling persuaded the high command in Cairo that he could achieve something significant at low cost in men and materials. The chief of British deception in the desert war, Dudley Clarke, gave the unit its name. Already fooling the Italians with a bogus parachute unit, the First Special Air Service Brigade, he lent the name to Stirling, and the organisation has borne it ever since.

Macintyre uses the SAS war diary as the backbone of his narrative, and is candid about failure as well as the hard-earned successes. The SAS was an irregular unit, its members drawn from an extraordinary range of backgrounds – a spectacles salesman, a textile merchant, a tomato farmer, amateur boxer, and so on – with a range of motives to match. Some wanted excitement, some liked killing and made no pretence about it, some were escaping from their past, some were too eccentric for the ranks; all had to be fit, alert, crafty, ruthless if required and dedicated to the mission. Stirling was also aware that his outfit did not meet with approval in conventional military circles, which saw war as face-to-face, not behind the back. Churchill liked the force, and would no doubt have joined it had it existed in his youth. But through the campaign in North Africa, then Italy and Germany, the SAS had always to prove itself, in order to stave off disbandment.

The new unit nevertheless made a disastrous start and indeed had mixed fortunes throughout the war. The first operation, code-named “Squatter”, carried out while the handful of volunteers were still feeling their way, could not have gone more wrong. Poorly trained as paratroopers, the group nevertheless flew off into a desert storm trying to land at pre-planned dropping zones well to the rear of the enemy. They landed in the worst places, faced a Saharan downpour of biblical proportions, lost some of the troop to injury as they hit the ground, and were then unable to retrieve the parachuted supplies. With explosives so soaked they were worthless, uncertain about their whereabouts, short of food and water, the remnants of the original units made their way back to Egypt. Out of 55 men, 34 were killed, injured, captured or missing without a single achievement.

Macintyre makes the point that this was by no means the end of a madcap idea. Stirling recruited the Long Range Desert Group to take the SAS teams by Jeep or truck rather than risk any further parachute drops, and the second set of raids in December 1941 resulted in the destruction or disabling of 60 enemy aircraft. But Operation Bigamy, a series of raids against Benghazi shortly before the battle of El Alamein, was another disaster. It featured one of the most bizarre figures to emerge from the story: a Belgian textile merchant, Robert Melot. Fluent in Arabic, keen to get at the Germans, he volunteered for the SAS aged 47 as an intelligence officer. He used his range of Libyan contacts to glean information needed for the raids, but in this case Melot miscalculated. An Arab double agent alerted the Germans and Italians and the raids were a disaster. Once again a forlorn, bearded, hungry and damaged band straggled back to Cairo. Melot carried on his SAS career regardless, and died not from his many scrapes in battle, but from a Jeep accident on his way to a party in Brussels late in 1944.

The SAS came of age in the campaign in Italy, where it was used as a more conventional raiding party, the Special Raiding Service, under the command of Paddy Mayne following Stirling’s capture in Tunisia in late 1942. The Italian campaign was a particularly grisly one, and the SRS (with its core of SAS men) found collaboration with the partisans and rivalry with the Special Operations Executive (SOE) a challenge (unlike the SAS, the SOE always linked up with local resistance). Macintyre spares none of the details; the SAS fought a dirty war against an enemy they regarded as every bit as dirty. Prisoners were rare, but in return Hitler condemned irregular commando units to death if they were caught. Not all were killed by any means, but many were, just as the Germans killed all the other irregular, partisan forces ranged against them.

In October 1945 the army wound up the SAS and it continued to exist by subterfuge, a unit of war crimes investigators searching for evidence across Europe that SAS members had been murdered. In 1947, to meet the many crises of empire, the SAS was revived. What it did then and since can be guessed at, but until the postwar unit diaries are revealed, like the wartime diary used by Macintyre, the exact details will not be known.

What in the end did the SAS achieve in the war? Macintyre does not really say, leaving the narrative to speak for itself. It did not, as some of the book’s publicity has suggested, turn the tide of war. Its overall accomplishment, set beside those of the Commandos, or the SOE, the Chindits or other partisan groups, was strategically modest, whatever its tactical successes. But the SAS did bring to life the plucky, maverick, individualist hero of the comic strip, a very British way of making war. SAS: Rogue Heroes is a great read of wartime adventuring, in a long, grim war of attrition where adventure was hard to find.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

been into paddy lately. i like him.

#paddy mayne#sas rogue heroes#rogue heroes#artists on tumblr#queer artist#sketch#art#new artist#my art#procreate#idk how to tag lmao

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pictured is my list for an upcoming Bolt Action tournament (Operation Shrike - we need a medic).

The list is a SAS reinforced platoon at 1136 points (the tournament maximum).

Headquarters: 1st Lt with a two man team. x2 smg and a rifle. Free medic for the tournament.

Blitz buggy with extra twin-vickers.

x4 jeeps: x2 with HMG and LMGs, x2 with twin-vickers and MMGs

X3 transports: x1 ford chevy with mmg, x2 jeeps with twin-vickers

X2 infantry sections: x4 smg and a medic with rifle.

X2 demo teams: 2 man with rifles and Lewis bombs.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Digital drawing of Conner Swindells as David Stirling an SAS Rogue Heroes!

Instagram | Redbubble

#sas rogue heroes#rogue heroes#connor swindells#david stirling#fanart#rogue heroes bbc#digital art#digital drawing#digital portrait#digital painting

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

So far we are still a pretty well behaved little community, we watch Paddy’s obsession with lanky, dark haired lads and keep to ourselves.

#You know what scene im talking about#I was expecting them to start “wrestling naked in the sand” at any moment#sas rogue heroes#rogue heroes#paddy mayne#eoin mcgonigal#augustin jordan#i hope i spelled that right#sas: rogue heroes

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

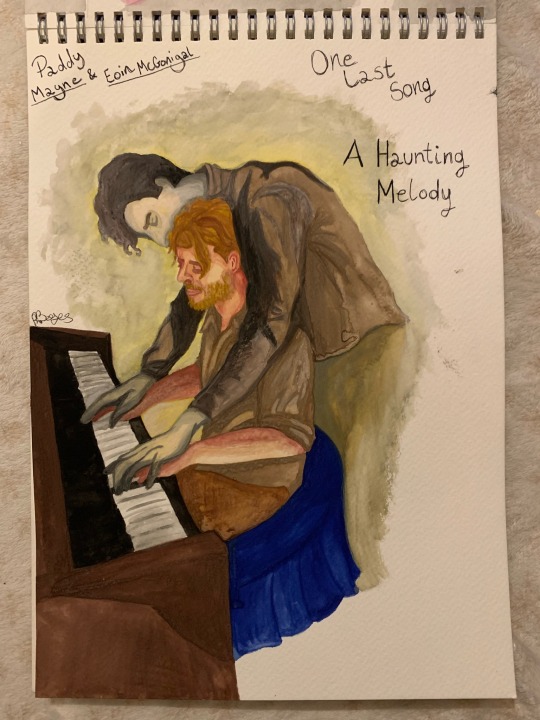

And herein lies proof of my latest obsession with SAS: Rogue Heroes. Paddy and Eoin’s relationship was so tragically beautiful.

#ignore me while I ramble#sas rogue heroes#rogue heroes#paddy mayne#eoin mcgonigal#paddon#paddy x eoin#eoin x paddy#fan art#my fan art#art#artists of tumblr#sas: rogue heroes

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

« Yes, it’s Cairo. But we are British. »

Rogue Heroes, 1.02

Tom Shankland (D), Steven Knight (S), 30/10/22

34 notes

·

View notes

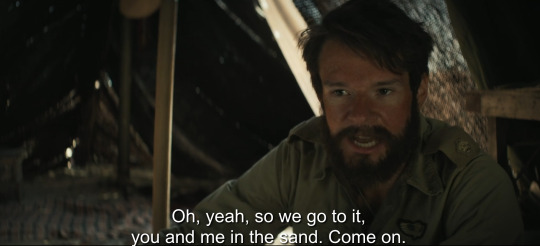

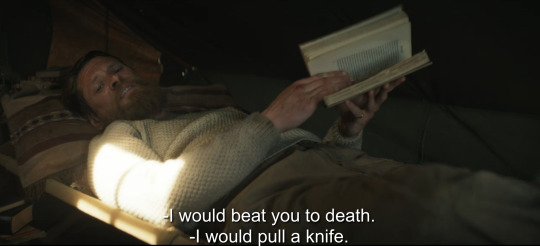

Photo

SAS: Rogue Heroes 1.05

#sas: rogue heroes#rogue heroes#jack o'connell#connor swindells#get you a friend who will force feed your balls down your jacobean throat

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

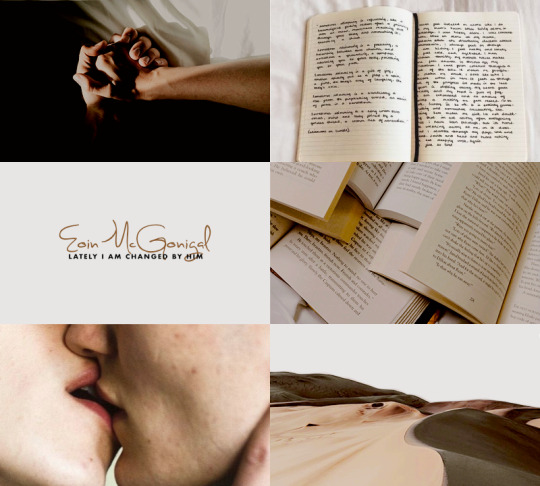

AESTHETIC EDITS [6/?] SAS: ROGUE HEROES : P A D D Y M A Y N E x E O I N M C G O N I G A L

"There's a fellow here I knew in Ulster. Eoin McGonigal. He's from the other side, but we don't talk religion. If I sit up barking and howling at night, as I sometimes do, he takes me for a walk and throws a stick for me. When I find myself become a devil, he reminds me that underneath I am a poet."

#paddy mayne#eoin mcgonigal#paddon#paddy x eoin#sas rogue heroes#sas: rogue heroes#sasrh#rogue heroes#sas#sasrhedit#sasrhaes#myedit#jack oconnell#jack o'connell#donal finn#dónal finn#myaes#my aesthetic#aesthetic edit#sas aesthetic#rogue heroes aesthetic#aesthetic#edit aesthetic#sas rogue heroes aesthetic#starkroqers#ladyeowyn

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paddy Mayne and Eoin McGonigal: Touch

sources:

touch me / Plato / The Song Of Achilles

#sprinkling some greek literature references for the gays#i feel unnormal about them#webbing#web weaving#poetry#poetry webs#rogue heroes#sas rogue heroes#paddy x eoin#paddy mayne#eoin mcgonigal#art webs#touch

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sofia Boutella as Eve in SAS: Rogue Heroes

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

the fandom within a fandom is so small i want to make edits fanarts and fanfics all at once for *checks notes* 5 people

28 notes

·

View notes