#the stalin epigram

Text

The Stalin Epigram

Our lives no longer feel ground under them.

At ten paces you can’t hear our words.

But whenever there’s a snatch of talk

it turns to the Kremlin mountaineer,

the ten thick worms his fingers,

his words like measures of weight,

the huge laughing cockroaches on his top lip,

the glitter of his boot-rims.

Ringed with a scum of chicken-necked bosses

he toys with the tributes of half-men.

One whistles, another meows, a third snivels.

He pokes out his finger and he alone goes boom.

He forges decrees in a line like horseshoes,

One for the groin, one the forehead, temple, eye.

He rolls the executions on his tongue like berries.

He wishes he could hug them like big friends from home.

-Osip Mandelstam

translation by W.S. Merwin & Clarence Brown

#poetry#poem#poets on tumblr#poems on tumblr#writers and poets#writers on tumblr#poetscommunity#dead poets society#poetry on tumblr#poetrycommunity#poetry writing#original poetry#poems and poetry#poetry blog#poetry corner#prose poetry#tumblr poetry#poems#words words words

0 notes

Text

Knight of Swords. Weiser Waite Smith Tarot

An armored knight with a sword in his hand sits on his horse, ready for battle.

The Knight of Swords uses his words to fight his battle. He is forthright and dedicated but exists entirely in the present tense. There is no sense of history for the Knight of Swords and no image of what the future might bring. These individuals are dedicated to the task at hand because it is required of them.

Osip Mandelstam recited his protest poetry against the brutal Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin in public, knowing that he was inviting danger, but he did it because Stalin was the dragon. He died in a prison camp.

Swords are words and thoughts, and the Knight of Swords knows how to use his words as weapons. It’s not simply about saying “No!” or heckling power from the crowd. It’s about using your ability to put thoughts and words into action, to sway others, and to encourage dissent. One doesn’t simply slay the dragon by waving weapons around and making noises to scare it off. One has to know where to strike and where vulnerability lies, but also how to get others on your side; to get them to see the dragon as a dragon.

That does not mean the Knight of Swords is always able to distinguish the dragon from the not-dragon themselves.

When working with the energy of the Knight of Swords, you have to be sure that your eyes are clear and your intentions are pure. The brain can play tricks. Logic can lead us down black holes. Which master are you serving? Is that a dragon or a maiden you are slaying with your sword? These are important questions to ask when this card turns up. Be sure you are not plowing your weapon into an innocent’s heart.

RECOMMENDED MATERIALS

“The Stalin Epigram,” poem by Osip Mandelstam

Jessa Crispin

0 notes

Text

Our lives no longer feel ground under them. At ten paces you can't hear our words.

But whenever there's a snatch of talk it turns to the Kremlin mountaineer,

the ten thick worms his fingers, his words like measures of weight,

the huge laughing cockroaches on his top lip, the glitter of his boot-rims.

Ringed with a scum of chicken-necked bosses he toys with the tributes of half-men.

One whistles, another meows, a third snivels. He pokes out his finger and he alone goes boom.

He forges decrees in a line like horseshoes, One for the groin, one the forehead, temple, eye.

He rolls the executions on his tongue like berries. He wishes he could hug them like big friends from home.

-The Stalin Epigram, Osip Mandelstam

0 notes

Text

we built these walls with our own fair hands

(/rp)

///

an ode to l’manberg by beetlebug // screenshot // what happened to goodbye by sarah dessen // humans are creatures of habit by @/isolatedphenomenon // l’manberg national anthem (extended) by kanaya // eret, dream smp // screenshot // morning in the burned house by margaret atwood // a memory on the eve of the return of the u.s. military to subic bay by patrick rosal // screenshot from nathan for you // the stalin epigram by osip mandelstam // jschlatt, dream smp // taking L’s by quackity // wilbur soot, dream smp // screenshot // excerpt from my diary, 6-9-2021 // humans are creatures of habit by @/isolatedphenomenon // nihachu, dream smp // undertale by toby fox // screenshot // bye l’manberg by dream

#mcyt#dream smp#web weaving#shit how do i tag this one#uhhhhhhh#lmanberg#lmanburg#manberg#manburg#l'manberg#l'manburg#whatever i give up anyway i became a sap and made this in like two hours bc i read my diary and saw that#is it cheating to use my own diary in a web weave. like. what.

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Stalin Epigram

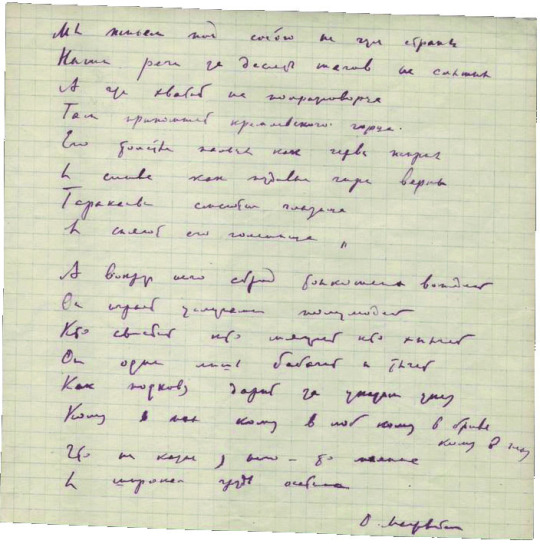

Some of you might know that my husband and I run a little free library on our front yard. The biggest reward of running a little free library is that from time to time, you get absolutely astonishing, wonderful books. Today somebody donated the most unexpected book to our community library - The Stalin Epigram . The book is about the life and fate of Osip Mandelstam, perhaps the greatest Russian poet of the twentieth century. His epigram on Stalin “Мы живём под собою не чуя страны” costed him his freedom and, then, life. There were bitter jokes that in Russia, poetry is a serious business, so much so, that one can get killed for a poem.

Here is the famous Stalin epigram:

Мы живём, под собою не чуя страны,

Наши речи за десять шагов не слышны,

А где хватит на полразговорца,

Там припомнят кремлёвского горца.

Его толстые пальцы, как черви, жирны,

И слова, как пудовые гири, верны,

Тараканьи смеются глазища

И сияют его голенища.

А вокруг него сброд тонкошеих вождей,

Он играет услугами полулюдей.

Кто свистит, кто мяучит, кто хнычет,

Он один лишь бабачит и тычет,

Как подкову, кует за указом указ:

Кому в пах, кому в лоб, кому в бровь, кому в глаз.

Что ни казнь у него — то малина,

И широкая грудь осетина.

Осип Мандельштам. Ноябрь, 1933.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

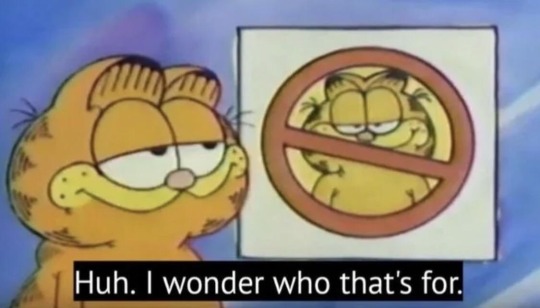

Yagoda reading the stanza of Mandelstam’s Stalin Epigram that very clearly attacks Stalin’s inner circle of bureaucrats, which he was a member of:

#I think he only liked this poem so much bc it calls stalin ugly which is objectively funny#no self awareness just caught up in the rush of reading lines abt stalin's 'fat wormlike fingers' to bukharin

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

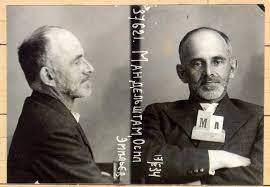

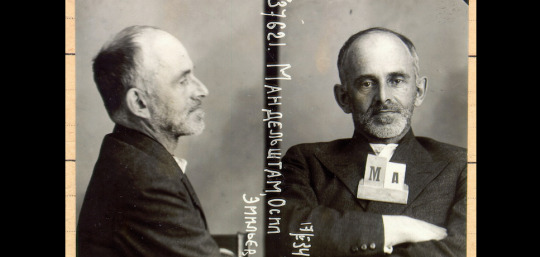

TODAY: In 1933 Joseph Stalin orders the NKVD to "preserve but isolate" Osip Mandelstam, after having been informed of the "Stalin Epigram"; Mandelstam is then arrested. A protest by literary figures, including Anna Akhmatova and Boris Pasternak, prompts Stalin to declare that he might "review the case" (he never will). https://lithub.com/tag/osip-mandelstam/

1 note

·

View note

Link

April 6–7 in NYC:

Teaching Translation and Interpreting Conference

April 6-7, 2019

Hunter College of the City University of New York

Hunter West, 8th Floor

Organized by Margarit T. Ordukhanyan (Hunter College)

Co-sponsored by American Translation and Interpreting Studies Association,

with the participation of the National Language Service

With a growing demand for professionals in the language support services, teaching translation and interpretation is quickly becoming an educational imperative. By bringing together representatives of the industry and the academe, the conference aims to bridge the gap between the way translation is taught and the way it is practiced outside academic institutions. The conference addressed the need for new and innovative approaches to teach aspects of translation and interpretation at all levels of the undergraduate and graduate curriculum. While addressing various perspective and methodologies, the conference seeks to elevate the profile of translation pedagogy as an independent academic discipline and explore its impact on other professional fields.

Saturday, April 6, 2019

9:00-10:15

Opening Remarks

Robert Cowan (Hunter College)

Keynote Address

“Emerging Contexts In Translation Pedagogy: Challenges and Opportunities”

Brian J. Baer (Kent State University)

Location: Faculty Dining Room, Hunter West 8th floor

*Coffee and light refreshments provided starting 8:45

10:30 – 12:00

Translation Curriculum: What the Profession Needs

Chair: Margarit Ordukhanyan (Hunter College)

“Teaching Translation and Interpretation: What the Profession Needs”

Caitilin Walsh (American Translators Association)

“Training Translators to Work for International Organizations”

Mekki Elbardi (United Nations)

“Cultural Mistranslation and the Big Business of Faith-Based Non-Profits in the USA”

Adrian Izquierdo (Baruch College)

12:00– 13:00

Lunch Break

*Lunch served in Faculty Dining Room

1:00-2:30

Panel II: Intercultural Communication in Translation

Chair: Margarit Ordukhanyan (Hunter College)

"Crossing Cultural Borders in a Digital World"

Annalisa Nash Fernandez (Because Culture LLC)

"Teaching Culture and Intercultural Communication to Future Translators and Interpreters"

Monique Roske (University of Maryland)

1:00-2:300

Workshop: Russian Translation Assessment

Facilitated by Annie Fisher (University of Wisconsin-Milwakee)

The workshop uses actual student assignments to discuss effective feedback, codification of errors, and other aspects of teaching Russian-language translation courses.

Location: Hunter West B126

2:45-4:30

Panel III: Translation and Technology

Chair: Annie Fisher (University of Wisconsin-Milwakee)

"Gauging and Establishing "Best" Practices in Online Translation Course Design

Andrew Tucker (Kent State University) and Erik Angelone (Kent State University)

“Leveraging Technology to Deliver Feedback in the Online Translation Course”

Annie Fisher (University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee)

"Enhancing Localization Graduate Employability Through Skill-Driven Curricula"

Loubna Bilali (Kent State University)

"Using and Integrating Large Institutional Websites in Translation Courses"

Françoise Herrmann (University of Maryland)

4:45-6:15

Translation, Community, Integration

Moderated by Julie Van Peteghem (Hunter College)

“The impact of interpreting education on the psychological effects of language brokering”

Aida Martinez Gomez (John Jay College)

The presentation is followed by a round-table by Hunter College students

6:30-9:00

Keynote and Reception

“Translation, the Liberal Arts and Global Humanities”

Aron Aji (University of Iowa)

Sunday, April 7

KEYNOTE SPEAKERS

Brian James Baer is Professor of Russian and Translation Studies at Kent State University. He is the author of the monographs Other Russias (2009) and Translation and the Making of Modern Russian Literature (2016), as well as the editor of several collected volumes, including Beyond the Ivory Tower: Re-thinking Translation Pedagogy with Geoffrey Koby (2003), Contexts, Subtexts, Pretexts: Literary Translation in Eastern Europe and Russia (2011), Researching Translation and Interpreting, with Claudia Angelelli (2015), Translation in Russian Contexts, with Susanna Witt (2018), and Queering Translation, Translating the Queer, with Klaus Kaindl (2018). He is founding editor of the journal Translation and Interpreting Studies and co-editor of the Bloomsbury book series Literatures, Cultures, Translation. He is also the translator of Juri Lotman's final monograph, The Unpredictable Workings of Culture (2013), and a forthcoming collection of essays by Lotman on cultural memory. He is the current president of the American Translation and Interpreting Studies Association.

8:45-10:30

Panel 1: Bringing Translation to the Classroom

Chair: Margarit Ordukhanyan (Hunter College)

"Starting from Scratch: Developing an Introduction to Translation and Interpreting Courses"

Garrett Bradford (University of Maryland)

"Pre- and Post-Translation Tasks in Translation Pedagogy"

Laura Ramirez Polo (Rutgers University)

“Community Engagement in Translation and Interpreting Courses”

Cristiano Mazzei (University of Massachusetts, Amherst)

“Teaching Translation as Situated Learning: Benefits of Engaging Translation Students with Refugee Communities”

Laurence Jay-Rayon Ibrahim Aibo (University of Massachusetts, Amherst)

Coffee and light refreshments served starting 8:30

10:30-12:15

Panel IIA: Serving Spanish-Speaking Communities

Chair: TBD

“Serving Low-Vision Spanish-Speaking Community in the US”

María José García-Vizcaíno (Montclair State University)

“Spanish Translation for Community Based Organizations"

E. Diana Biagioli (Independent Professional)

“Designing a Concentration in Translation for a Four-Year College”

Reyes Lazaro (Smith College)

10:30-12:15

Panel IIB: Teaching Russian Through Translation

Chair: Brian J. Baer

"Cultural Mediation: Teaching Russian Poetry to Russian Heritage Students"

Julia Trubikhina (Hunter College) and Christopher Czubay (Hunter College)

"Teaching Translation as an Advanced Language Course"

Ainsley Morse (Pomona College)

"Bridging the Divide: Anton Chekhov’s “Sleepy” and the Challenges and Rewards of Literary Transposition"

Nadya Peterson (Hunter College)

12:15-1:00

Lunch Break

1:00-2:30

Panel III: Bringing Translation to Non-Translation Classrooms

Chair: Esther Allen (Baruch College)

"Teaching Translation from All Languages: Evaluation, Integration, and Relevant Readings (for the Professor Who Knows Only Some of Them)"

Sibelan Forrester (Swarthmore College)

“Possibility of the Impossible: Comparing Translations of Osip Mandelstam’s Epigram to Stalin”

Ian Probstein (Touro College)

“Comparative Translations in the Intermediate Hindi Classroom”

Jason Grunebaum (University of Chicago)

2:45-4:15

Panel IV: Roundtable – Reading like a Translator

Chair/Discussant: Julie Van Peteghem (Hunter College)

Karen Emmerich (Princeton University)

Anne Janusch (University of Chicago)

Jennifer Zoble (New York University)

4:30-5:30

Panel V: Issues of Inclusivity, Gender, and Diversity in Translation

Chair: Esther Allen (Baruch College)

“Teaching Translation through Gender Topics: Adapting the Instructional Design of an Introductory Translation Course”

Iván Villanueva-Jordán (Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas)

“The Gender Gap in Translation: Translator Advocacy and Curricular Applications”

Margaret Carson (Borough of Manhattan Community College)

5:45-6:00

Continuing Conversations: Looking Ahead

Margarit Ordukhanyan (Hunter College)

Aron Aji is the Director of MFA in Literary Translation at University of Iowa. A native of Turkey, he has translated works by Bilge Karasu, Murathan Mungan, Elif Shafak, LatifeTekin, and other Turkish writers, including three book-length works by Karasu: Death in Troy; The Garden of Departed Cats, (2004 National Translation Award); and A Long Day’s Evening, (NEA Literature Fellowship, and short-listed for the 2013 PEN Translation Prize). He also edited, Milan Kundera and the Art of Fiction. Aji leads the Translation Workshop, and teaches courses on retranslation, poetry and translation; theory, and contemporary Turkish literature. He is also the president of The American Literary Translators Association.

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

We live, deaf to the land beneath us,

Ten steps away no one hears our speeches,

Osip Mandelstam (Russian, 1891–1938), from “Epigram Against Stalin” (translated from Russian by Nancy K. Anderson), in “The Word That Causes Death’s Defeat. Poems of Memory.”

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi! so i saw like a billion years ago that you posted something about wise blood, and i was just wondering how you experienced the book as a jewish person; i know i related a lot to the trying-to-escape-christ narrative b/c of how i've experienced christianity, so i was just curious for your perspective i guess? idk if this is worded in a weird/offensive way i really really do not mean it to be i just love how you talk about books so i wanted to ask

Thisis such a fantastic question—you know, I’ve always had a reflexive and visceraladoration for Flannery O’Connor but it never actually occurredto me to look for a subjective point of contact.

Theeasy answer is that the Christian themes of redemption and transformation in her work are rooted in Judaism, so I recognize and respond to that with thesame secular reverence that makes me weep at Matthäus-Passion.

Thecomplicated answer is that there is nothing more Russian than autopsying a culturethat’s allowed hypocrisy and guilt to metastasize to the point where even faith has becomegrotesque. The ugliness in our past is not as simple as a funeral or as clean as resurrection, and the obligation to reckon with it is a terrible sort of birthright.

In other words, there’s a grim rejoinder to Mandelstam’s Stalin Epigram:

Later he saw Jesus move from tree to tree inthe back of his mind, a wild ragged figure motioning him to turn around andcome off into the dark where he might be walking on the water and not know itand then suddenly know it and drown.

#''it is bitter—bitter'' he answered#''but i like it because it is bitter. and because it is my heart.''#i'm still sick so there are better than even odds this makes less sense than i would like#but also this was such a good ask that waiting for the dayquil to wear off was out of the question#brb trembling under the fearsome auspices of stalin/southern gothic jesus#also hazel motes is ivan karamazov but in an itchier hat#flannery o'connor#osip mandelstam#wise blood#i read much of the night and go south in the winter#toska#anonymous#assbox

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Stalin Epigram, also known as The Kremlin Highlander (Russian: Кремлёвский горец) is a satirical poem by the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, written in November 1933. The poem describes the climate of fear in the Soviet Union.[1]

Mandelstam read the poem only to a few friends, including Boris Pasternak and Anna Akhmatova. The poem played a role in his own arrest and the arrests of Akhmatova's son and husband, Lev Gumilev and Nikolay Punin.[2]

The poem was almost the first case Genrikh Yagoda dealt with after becoming NKVD boss. Bukharin visited Yagoda to intercede for Mandelstam, unaware of the nature of his "offense". According to Mandelstam's widow: "Yagoda liked M.'s poem so much that he even learned it by heart - he recited it to Bukharin - but he would not have hesitated to destroy the whole of literature, past, present and future, if he had thought it to his advantage. For people of this extraordinary type, human blood is like water."[3]

We are living, but can’t feel the land where we stay,

More than ten steps away you can’t hear what we say.

But if people would talk on occasion,

They should mention the Kremlin Caucasian.

His thick fingers are bulky and fat like live-baits,

And his accurate words are as heavy as weights.

Cucaracha’s moustaches are screaming,

And his boot-tops are shining and gleaming.

But around him a crowd of thin-necked henchmen,

And he plays with the services of these half-men.

Some are whistling, some meowing, some sniffing,

He’s alone booming, poking and whiffing.

He is forging his rules and decrees like horseshoes –

Into groins, into foreheads, in eyes, and eyebrows.

Every killing for him is delight,

And Ossetian torso is wide.

The phrase "Ossetian torso" in the final line refers to the ethnicity of Stalin, whose paternal grandfather was possibly an ethnic Ossetian.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stalin_Epigram

0 notes

Photo

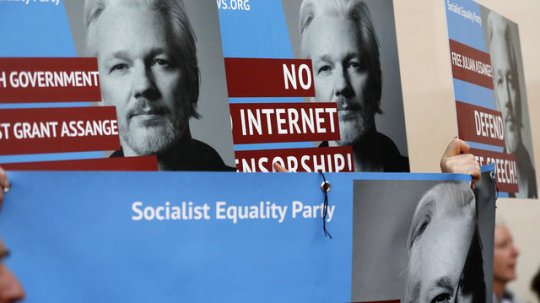

Julian Assange Vows To Fight Extradition To The United States May 2, 2019

“Two more hearings were reportedly scheduled for May 30 and June 12, after Assange's lawyers receive the full contents of the U.S. extradition request. The judge predicted the case will take "many months."

READ MORE https://www.npr.org/2019/05/02/719435175/julian-assange-vows-to-fight-extradition-to-the-united-states

“ As CNN explained, to extradite Assange, a court must agree that his alleged violations would also constitute criminal conduct in the UK. Afterward, the UK’s home secretary would still have final say on whether Assange is handed over.” READ MORE https://theantimedia.com/julian-assange-vows-fight-charges/

Top Comments

I am reminded of Osip Mandelshtam, imprisoned for writing of Joseph Stalin, particularly this:

from Poems of the Thirties: 286 [The Stalin Epigram]

By Osip Mandelstam

Translated by Clarence Brown and W. S. Merwin

Our lives no longer feel ground under them.

At ten paces you can’t hear our words.

But whenever there’s a snatch of talk

it turns to the Kremlin mountaineer,

the ten thick worms his fingers,

his words like measures of weight,

the huge laughing cockroaches on his top lip,

the glitter of his boot-rims.

Ringed with a scum of chicken-necked bosses

he toys with the tributes of half-men.

One whistles, another meouws, a third snivels.

He pokes out his finger and he alone goes boom.

He forges decrees in a line like horseshoes,

One for the groin, one the forehead, temple, eye.

He rolls the executions on his tongue like berries.

He wishes he could hug them like big friends from home.

0 notes

Text

[The Stalin Epigram]

“Our lives no longer feel ground under them

At ten paces you can’t hear our words.

But wherever there’s a snatch of talk

it turns to the Kremlin mountaineer,

the thick ten worms of his fingers

his words like measures of weight,

the huge laughing cockroaches on his top lip,

the glitter of his boot-rims....”

This is an excerpt from a poem by the extraordinary Russian poet, Osip Mandelstam, about Joseph Stalin. Because of this poem, Mandelstam was arrested, exiled and eventually deported to a labor camp, where he continued to manage to write but eventually met his death. This man died because he wrote a poem. This man died because he offended the leader of his country wit his words . This man died because he didn’t have the right to free speech.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Richard Pipes, Historian of Russia and Reagan Aide, Dies at 94

Richard Pipes, the author of a monumental, sharply polemical series of historical works on Russia, the Russian Revolution and the Bolshevik regime, and a top adviser to the Reagan administration on Soviet and Eastern European policy, died on Thursday at a nursing home near his home in Cambridge, Mass. He was 94.

His son Daniel confirmed the death.

Professor Pipes, who spent his entire academic career at Harvard, took his place in the front rank of Russian historians with the publication of “Russia Under the Old Regime” in 1974. But he achieved much wider renown as a public intellectual deeply skeptical about the American policy of détente with the Soviet Union.

In 1976, he led a group of military and foreign-policy experts, known as Team B, in an ultimately pessimistic analysis of the Soviet Union’s military strategy and foreign policy and the threats they posed to the United States.

The group’s report, commissioned by the Central Intelligence Agency as a counterweight to an analysis that had been generated by the C.I.A.’s own experts — Team A — helped galvanize conservative opposition to arms-control talks and accommodation with the Soviet Union. And it set the stage for Ronald Reagan’s policy of challenging Soviet foreign policy and seeking to undermine its hold over Eastern Europe.

While writing ambitious histories of the Russian Revolution and the Bolshevik regime, Professor Pipes continued his campaign for a tougher foreign policy toward the Soviet Union in the late 1970s as a member of the neoconservative Committee on the Present Danger and as director of Eastern European and Soviet affairs for President Reagan’s National Security Council.

Despite this public role, he regarded himself, first and foremost, as a historian of Russian history, politics and culture — a field in which he performed with great distinction. A forceful, stylish writer with a sweeping view of history, Professor Pipes covered nearly 600 years of the Russian past in “Russia Under the Old Regime,” abandoning chronology and treating his subject by themes, such as the peasantry, the church, the machinery of state and the intelligentsia.

One of his most original contributions was to locate many of Russia’s woes in its failure to evolve beyond its status as a patrimonial state, a term he borrowed from the German sociologist Max Weber to characterize Russian absolutism, in which the czar not only ruled but also owned his domain and its inhabitants, nullifying the concepts of private property and individual freedom.

With “The Russian Revolution” (1990), Professor Pipes mounted a frontal assault on many of the premises and long-held convictions of mainstream Western specialists on the Bolshevik seizure of power. That book, which began with the simple Russian epigram “To the victims,” took a prosecutorial stance toward the Bolsheviks and their leader, Vladimir Lenin, who still commanded a certain respect and sympathy among Western historians.

Professor Pipes, a moralist shaped by his experiences as a Jew who had fled the Nazi occupation of Poland, would have none of it. He presented the Bolshevik Party as a conspiratorial, deeply unpopular clique rather than the spearhead of a mass movement. He shed new and harsh light on the Bolshevik campaign against the peasantry, which, he argued, Lenin had sought to destroy as a reactionary class. He also accused Lenin of laying the foundation of the terrorist state that his successor, Joseph Stalin, perfected.

“I felt and feel to this day that I have been spared not to waste my life on self-indulgence and self-aggrandizement but to spread a moral message by showing, using examples from history, how evil ideas lead to evil consequences,” Professor Pipes wrote in a memoir. “Since scholars have written enough on the Holocaust, I thought it my mission to demonstrate this truth using the example of communism.”

The British historian Ronald Hingley wrote of “The Russian Revolution” in The New York Times Book Review that “no single volume known to me even begins to cater so adequately to those who want to work through 842 intellectually challenging pages in order to discover what really happened to Russia in and around 1917.”

Other reviewers found Professor Pipes intemperate and, on occasion, blinded by his zeal to redress moral wrongs.

William G. Rosenberg, writing in The Nation, praised Professor Pipes’s “remarkable intellectual range, crystalline style and capacity to muster an extraordinary mass of evidential detail” but complained of “scholarship distorted by passion.”

“Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime,” which was published in 1994 and covered the period from the Russian Civil War to the death of Lenin in 1924, also met with a divided response.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, however, Professor Pipes emerged as an esteemed Western historian in Russia — a novel experience for a man who had been reviled by Soviet historians throughout his career.

By this time, he had long been prominent as a leading critic of détente and arms-control talks with the Soviet Union, and a loathed figure on the left. “Those who called me a cold warrior apparently expected me to cringe,” he wrote in “Vixi: Memoirs of a Non-Belonger” (2003). “In fact, I accepted the title proudly.”

Mr. Pipes joined the recently formed Committee on the Present Danger in 1977. (The group had borrowed its name from a similar, though unrelated, group that had sought to counter Soviet expansion in the immediate postwar years.) The committee was composed of neoconservatives who opposed nuclear-arms talks — “hollow rituals,” as Professor Pipes called them — and supported increased spending on weapons programs.

Perhaps his most public role in challenging American policies toward the Soviet Union came in 1976 under President Gerald R. Ford.

At the time, conservative critics had for several years been attacking the C.I.A.’s National Intelligence Estimate, an annual assessment of the Soviet threat, calling it overly optimistic about Soviet foreign-policy intentions and blind to what they believed to be a dangerous military buildup.

In response, the C.I.A., under pressure from the president’s Foreign Policy Advisory Board, conducted an in-house review of its performance in analyzing Soviet strategic doctrine and military capabilities over the previous decade.

But the resulting report by the C.I.A.’s experts — the so-called Team A — was found to be so deficient that President Ford asked the C.I.A. director, George H. W. Bush, to order a competitive analysis, pitting the agency experts against a team of outsiders.

Professor Pipes, who had been serving as an adviser to Senator Henry M. Jackson of Washington, a Democrat who was a harsh critic of détente, was appointed to lead Team B.

Its conclusion — that the C.I.A. had badly underestimated the “intensity, scope and implicit threat” of Soviet military objectives — later gave ammunition to Ronald Reagan as he took to the campaign trail for the 1980 presidential election espousing a hard line against Moscow.

With Reagan’s victory over President Jimmy Carter in the election, Professor Pipes, taking a leave from Harvard, was appointed director of Eastern European and Soviet affairs at the National Security Council. He again became a lightning rod for the left, which regarded him as a sinister influence on Soviet policy.

He went on to play a pivotal role in drafting National Security Decision Directive 75, which set forth the Reagan administration’s policy toward the Soviet Union. It called for the government to shift the emphasis away from punishing Soviet misbehavior after the fact and to concentrate instead on pursuing policies that would change the nature of the regime.

But by Professor Pipes’s own account, the State Department, headed by Alexander M. Haig, shut the N.S.C. out of most important decisions, and Professor Pipes’s relative inexperience in Washington infighting was seen to have blunted his effectiveness. He left the post after two years, the maximum number Harvard allowed.

Ryszard Edgar Pipes was born on July 11, 1923, in Cieszyn, Poland, where his father, Marek, ran a chocolate factory. His mother, Sara Sofia (Haskelberg) Pipes, who went by Zosia, was a homemaker. The family, which later moved to Krakow and Warsaw, spoke German at home and Polish on the street.

In 1939, soon after German troops entered Warsaw, the Pipeses fled to Italy on forged passports. They reached the United States a year later, settling in Elmira, N.Y.

To further his education, Professor Pipes set about compiling a random list of 100 American colleges from the advertising pages of “Who’s Who,” then sent off postcards to them asking for financial aid and part-time work. Muskingum College in Ohio (now Muskingum University) replied with offers for both.

In 1942, in his junior year, he was drafted into the Army Air Corps and sent to study Russian at Cornell, where he met his future wife, Irene Roth, who survives him.

Besides her and his son Daniel, he is survived by another son, Steven, and four grandchildren. He had homes in Cambridge and in Harrisville, N.H.

After receiving a bachelor’s degree from Cornell in 1946, he earned a doctorate in history at Harvard in 1950. His dissertation, on Bolshevik nationality theory, became the basis of his first book, “The Formation of the Soviet Union: Communism and Nationalism, 1917-1923” (1954).

He later wrote a two-volume biography of the liberal politician Peter Struve, “Struve: Liberal on the Left, 1870-1905” (1970) and “Struve: Liberal on the Right, 1905-1944” (1980), as well as two books on Soviet-American relations, “U.S.-Soviet Relations in the Era of Détente” (1981) and “Survival Is Not Enough: Soviet Realities and America’s Future” (1984).

As a historian, Professor Pipes defended his polemical approach. In “The Russian Revolution,” he wrote:

“The Russian Revolution was made neither by the forces of nature nor by anonymous masses but by identifiable men pursuing their own advantages. Although it has spontaneous aspects, in the main it was the result of deliberate action. As such it is very properly subject to value judgment.”

In the writing of history, he went on, “fundamental philosophical and moral questions can never end.”

“For the dispute is not only over what has happened in the past,” he wrote, “but also over what may happen in the future.”

Daniel E. Slotnik contributed reporting.

A version of this article appears in print on , on Page B14 of the New York edition with the headline: Richard Pipes, Historian Of Russia and Adviser To Reagan, Dies at 94. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

The post Richard Pipes, Historian of Russia and Reagan Aide, Dies at 94 appeared first on World The News.

from World The News https://ift.tt/2GvlZrG

via Breaking News

0 notes

Text

Richard Pipes, Historian of Russia and Reagan Aide, Dies at 94

Richard Pipes, the author of a monumental, sharply polemical series of historical works on Russia, the Russian Revolution and the Bolshevik regime, and a top adviser to the Reagan administration on Soviet and Eastern European policy, died on Thursday at a nursing home near his home in Cambridge, Mass. He was 94.

His son Daniel confirmed the death.

Professor Pipes, who spent his entire academic career at Harvard, took his place in the front rank of Russian historians with the publication of “Russia Under the Old Regime” in 1974. But he achieved much wider renown as a public intellectual deeply skeptical about the American policy of détente with the Soviet Union.

In 1976, he led a group of military and foreign-policy experts, known as Team B, in an ultimately pessimistic analysis of the Soviet Union’s military strategy and foreign policy and the threats they posed to the United States.

The group’s report, commissioned by the Central Intelligence Agency as a counterweight to an analysis that had been generated by the C.I.A.’s own experts — Team A — helped galvanize conservative opposition to arms-control talks and accommodation with the Soviet Union. And it set the stage for Ronald Reagan’s policy of challenging Soviet foreign policy and seeking to undermine its hold over Eastern Europe.

While writing ambitious histories of the Russian Revolution and the Bolshevik regime, Professor Pipes continued his campaign for a tougher foreign policy toward the Soviet Union in the late 1970s as a member of the neoconservative Committee on the Present Danger and as director of Eastern European and Soviet affairs for President Reagan’s National Security Council.

Despite this public role, he regarded himself, first and foremost, as a historian of Russian history, politics and culture — a field in which he performed with great distinction. A forceful, stylish writer with a sweeping view of history, Professor Pipes covered nearly 600 years of the Russian past in “Russia Under the Old Regime,” abandoning chronology and treating his subject by themes, such as the peasantry, the church, the machinery of state and the intelligentsia.

One of his most original contributions was to locate many of Russia’s woes in its failure to evolve beyond its status as a patrimonial state, a term he borrowed from the German sociologist Max Weber to characterize Russian absolutism, in which the czar not only ruled but also owned his domain and its inhabitants, nullifying the concepts of private property and individual freedom.

With “The Russian Revolution” (1990), Professor Pipes mounted a frontal assault on many of the premises and long-held convictions of mainstream Western specialists on the Bolshevik seizure of power. That book, which began with the simple Russian epigram “To the victims,” took a prosecutorial stance toward the Bolsheviks and their leader, Vladimir Lenin, who still commanded a certain respect and sympathy among Western historians.

Professor Pipes, a moralist shaped by his experiences as a Jew who had fled the Nazi occupation of Poland, would have none of it. He presented the Bolshevik Party as a conspiratorial, deeply unpopular clique rather than the spearhead of a mass movement. He shed new and harsh light on the Bolshevik campaign against the peasantry, which, he argued, Lenin had sought to destroy as a reactionary class. He also accused Lenin of laying the foundation of the terrorist state that his successor, Joseph Stalin, perfected.

“I felt and feel to this day that I have been spared not to waste my life on self-indulgence and self-aggrandizement but to spread a moral message by showing, using examples from history, how evil ideas lead to evil consequences,” Professor Pipes wrote in a memoir. “Since scholars have written enough on the Holocaust, I thought it my mission to demonstrate this truth using the example of communism.”

The British historian Ronald Hingley wrote of “The Russian Revolution” in The New York Times Book Review that “no single volume known to me even begins to cater so adequately to those who want to work through 842 intellectually challenging pages in order to discover what really happened to Russia in and around 1917.”

Other reviewers found Professor Pipes intemperate and, on occasion, blinded by his zeal to redress moral wrongs.

William G. Rosenberg, writing in The Nation, praised Professor Pipes’s “remarkable intellectual range, crystalline style and capacity to muster an extraordinary mass of evidential detail” but complained of “scholarship distorted by passion.”

“Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime,” which was published in 1994 and covered the period from the Russian Civil War to the death of Lenin in 1924, also met with a divided response.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, however, Professor Pipes emerged as an esteemed Western historian in Russia — a novel experience for a man who had been reviled by Soviet historians throughout his career.

By this time, he had long been prominent as a leading critic of détente and arms-control talks with the Soviet Union, and a loathed figure on the left. “Those who called me a cold warrior apparently expected me to cringe,” he wrote in “Vixi: Memoirs of a Non-Belonger” (2003). “In fact, I accepted the title proudly.”

Mr. Pipes joined the recently formed Committee on the Present Danger in 1977. (The group had borrowed its name from a similar, though unrelated, group that had sought to counter Soviet expansion in the immediate postwar years.) The committee was composed of neoconservatives who opposed nuclear-arms talks — “hollow rituals,” as Professor Pipes called them — and supported increased spending on weapons programs.

Perhaps his most public role in challenging American policies toward the Soviet Union came in 1976 under President Gerald R. Ford.

At the time, conservative critics had for several years been attacking the C.I.A.’s National Intelligence Estimate, an annual assessment of the Soviet threat, calling it overly optimistic about Soviet foreign-policy intentions and blind to what they believed to be a dangerous military buildup.

In response, the C.I.A., under pressure from the president’s Foreign Policy Advisory Board, conducted an in-house review of its performance in analyzing Soviet strategic doctrine and military capabilities over the previous decade.

But the resulting report by the C.I.A.’s experts — the so-called Team A — was found to be so deficient that President Ford asked the C.I.A. director, George H. W. Bush, to order a competitive analysis, pitting the agency experts against a team of outsiders.

Professor Pipes, who had been serving as an adviser to Senator Henry M. Jackson of Washington, a Democrat who was a harsh critic of détente, was appointed to lead Team B.

Its conclusion — that the C.I.A. had badly underestimated the “intensity, scope and implicit threat” of Soviet military objectives — later gave ammunition to Ronald Reagan as he took to the campaign trail for the 1980 presidential election espousing a hard line against Moscow.

With Reagan’s victory over President Jimmy Carter in the election, Professor Pipes, taking a leave from Harvard, was appointed director of Eastern European and Soviet affairs at the National Security Council. He again became a lightning rod for the left, which regarded him as a sinister influence on Soviet policy.

He went on to play a pivotal role in drafting National Security Decision Directive 75, which set forth the Reagan administration’s policy toward the Soviet Union. It called for the government to shift the emphasis away from punishing Soviet misbehavior after the fact and to concentrate instead on pursuing policies that would change the nature of the regime.

But by Professor Pipes’s own account, the State Department, headed by Alexander M. Haig, shut the N.S.C. out of most important decisions, and Professor Pipes’s relative inexperience in Washington infighting was seen to have blunted his effectiveness. He left the post after two years, the maximum number Harvard allowed.

Ryszard Edgar Pipes was born on July 11, 1923, in Cieszyn, Poland, where his father, Marek, ran a chocolate factory. His mother, Sara Sofia (Haskelberg) Pipes, who went by Zosia, was a homemaker. The family, which later moved to Krakow and Warsaw, spoke German at home and Polish on the street.

In 1939, soon after German troops entered Warsaw, the Pipeses fled to Italy on forged passports. They reached the United States a year later, settling in Elmira, N.Y.

To further his education, Professor Pipes set about compiling a random list of 100 American colleges from the advertising pages of “Who’s Who,” then sent off postcards to them asking for financial aid and part-time work. Muskingum College in Ohio (now Muskingum University) replied with offers for both.

In 1942, in his junior year, he was drafted into the Army Air Corps and sent to study Russian at Cornell, where he met his future wife, Irene Roth, who survives him.

Besides her and his son Daniel, he is survived by another son, Steven, and four grandchildren. He had homes in Cambridge and in Harrisville, N.H.

After receiving a bachelor’s degree from Cornell in 1946, he earned a doctorate in history at Harvard in 1950. His dissertation, on Bolshevik nationality theory, became the basis of his first book, “The Formation of the Soviet Union: Communism and Nationalism, 1917-1923” (1954).

He later wrote a two-volume biography of the liberal politician Peter Struve, “Struve: Liberal on the Left, 1870-1905” (1970) and “Struve: Liberal on the Right, 1905-1944” (1980), as well as two books on Soviet-American relations, “U.S.-Soviet Relations in the Era of Détente” (1981) and “Survival Is Not Enough: Soviet Realities and America’s Future” (1984).

As a historian, Professor Pipes defended his polemical approach. In “The Russian Revolution,” he wrote:

“The Russian Revolution was made neither by the forces of nature nor by anonymous masses but by identifiable men pursuing their own advantages. Although it has spontaneous aspects, in the main it was the result of deliberate action. As such it is very properly subject to value judgment.”

In the writing of history, he went on, “fundamental philosophical and moral questions can never end.”

“For the dispute is not only over what has happened in the past,” he wrote, “but also over what may happen in the future.”

Daniel E. Slotnik contributed reporting.

A version of this article appears in print on , on Page B14 of the New York edition with the headline: Richard Pipes, Historian Of Russia and Adviser To Reagan, Dies at 94. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe

The post Richard Pipes, Historian of Russia and Reagan Aide, Dies at 94 appeared first on World The News.

from World The News https://ift.tt/2GvlZrG

via Everyday News

0 notes