Text

The Power of Why

“One thing I have been asked a few times is this: ‘Does writing about bad experiences make you feel worse?’

I understand why people ask the question, but for me the answer is a profound ‘No’.

I discovered this years ago. When I was very ill, at the lowest of the low, when I could hardly speak, I wrote down what I was feeling. One day I wrote down the words ‘invisible weight’. Another day I wrote ‘I wish I could claw into my head and take out the part of my brain that makes me feel like this’. There were even darker things I put down. But writing down darkness didn’t make me feel dark. I already felt dark. Writing things down brought that inner darkness into external light.

Nowadays, I sometimes write about what I want. The key to this is honesty. Be brutally, humiliatingly honest. I recommend this.

For instance, you could write, ‘I want a six-pack’.

And seeing that wish on the page might automatically make you realise something about it. It might make you feel silly for having it. You might already be awakening to another part of you that helps you diminish the craving. But either way, it is good to ask a single-word question after it. ‘Why?’ Why do I want a six-pack? Then to be entirely honest in your answer. ‘I want to look good.’ And again: ‘Why?’ ‘For myself.’ And then you might stare at that answer for a while and feel you weren’t being entirely honest. So you add, ‘To impress other people.’ And then, like some incessant Socrates, ask it again: ‘Why?’ ‘Because I want their approval.’ ‘Why?’ ‘Because I want to belong.’ ‘Why?’ And you can keep going, deeper and deeper, through the tunnel of why's, until you reach the light of realisation. And the realisation may be that wanting the six-pack wasn’t really about the six-pack. It wasn’t about your body. It wasn’t even about health or strength or fitness. It was about something else entirely. Something that wouldn’t be fundamentally addressed or solved by gaining the six-pack.

Writing, then, is a kind of seeing. A way to see your insecurities more clearly. A way to shine a light on doubts and dreams and realise what they are actually about. It can dissolve a whole puddle of worries in the bright light of truth.”

- Matt Haig, The Comfort Book, pp.36-37

0 notes

Text

Waking up to life

An Introduction to the book of Ecclesiastes

I always love the start of the year. December is done. Christmas is done. The year before is done. And now we get a whole new one! And as a measure of generosity, it even seems to start at a much slower pace than the year just past ended.

With the start of a new year comes an opportunity to pause. It is in some ways a trick; what makes the last day of December any different from the first day of January? The sun rises just the same. Your organs and cells and all the rest of you continue the same basic processes. You still need to eat and go the toilet. It’s all more or less the same. But sometimes we need an excuse to look at our lives again. To think about how we live. To make decisions about our lives. It’s entirely easy to continue going through the motions. To live unreflective lives. To take anything and everything for granted.

Let’s say we did that. We can, if we really want to. We can sleepwalk through our lives. And we do. Sometimes for long stretches of our lives. It’s like we’re in the passenger seat of a car that someone else is driving. While they drive we rest our eyes a little. We’re cosy, comfortable. Eventually we drift into our slumber.

Imagine then the sound of screeching tires and then being jolted from your sleep as you lurch forward into your seatbelt unexpectedly. Consciousness! Shocking consciousness! Your rub your face and try and make sense of the situation. Some idiot is standing in front of your car with their arms stretched out before you forcing you to come to a sudden stop. You’re angry and confused. You want to yell at the mad fool before you. But there’s something unsettling about them. An intensity. A wildness. They demand to be taken seriously.

Who is this reckless figure standing before your vehicle? Well, and this will sound strange, but it’s a reasonably unknowable figure that some have called the Teacher. Or the Preacher. Or even the Sage. Some imagine Solomon, but that doesn’t quite fit. The most common name for this mysterious figure is Qohelet. Qohelet is the wild one bringing our car to a screeching halt.

Anyone who has read the book of Ecclesiastes might write Qohelet off as a pessimistic, burnt-out oddball who just hasn’t been able to grasp the bigger picture. His thesis is missing some key elements that offer us the perspective and hope that later revelation offers us: things like the incarnation and resurrection, some clues about life after death, that sort of thing. And so a lot of people bypass Ecclesiastes. In other words, their car might be brought to a halt, temporarily, but they quickly swerve around this strange figure and get on their way, easing back into a nice, comfortable dreamland once again. And so we miss the wisdom of Qohelet. The wisdom of the fool. We miss the surprising opportunity to really wake up to life.

Say what you like about Qohelet but Qohelet is someone who values life. So much so that Qohelet is a passionate critic of how our car ride generally, or eventually, plays out. What Qohelet knows is that our car ride won’t simply go on forever, no matter how much we might wish it were so. The sun and the wind and rivers will continue to go round and around but you and I won’t. We are here today, gone tomorrow. Time and chance comes to us all. What feels like a shocking intrusion of reality is actually a kindness. Qohelet is urging us to take nothing for granted. Qohelet is waking us up, or perhaps more accurately, Qohelet is wake-ing us up.

What does is mean to live our lives in light of the fact that some day - and who knows when - people will indeed gather around our coffin and farewell us as we shuffle off this mortal coil?

Qohelet is giving us the chance ahead of time to live and love our lives starting now. That’s what real wisdom teachers do. That’s what Ecclesiastes does, albeit in surprising ways.

So, the Teacher is standing before your car. The choice is yours. Swerve if you like and go on your way. Or perhaps invite Qohelet in. You might want to buckle yourself in though. Happy new year.

Practice:

End of Year Examen

Whether you’re reading this at the end of the old or the start of a brand new year or any time at all, a helpful place to start might be with an exercise to examine your life. You can do this just by prayerfully sitting with some key reflective questions as your review the last year.

Here is a guided Ignation examen with music and prayerful prompts if you like (click here).

Here are some questions you might ask yourself as you review the last year -

What have been the biggest happenings this year? What memories from this year immediately come to mind as I think about the year?

What has my heart been most attached to and focused on this year? Where did a lot of my best energies and attention go?

What new has come into my life this year? How have I been surprised this year?

How have I grown this year? How am I different because of the things that have taken place this year?

How have I experienced the presence of God this year?

What were some of the bigger themes of the year?

Experiences of Desolation

What have been the places of struggle or great challenge?

What has made me feel especially stressed, worried or vulnerable?

What have I lost this year? What have I had to let go of?

Welcome divine light into these experiences of desolation.

Experiences of Consolation

What have been the gifts from this year?

What am I most grateful for?

What have been my richest experiences of joy, strength, comfort, hope, meaning, peace and love?

Where have I noticed beauty?

Give thanks for these sources of consolation.

Looking Ahead

What do I want to carry into this year ahead?

What do I want to let go of?

What are my hopes for the year ahead?

You might like to finish your end of year examen by reading this blessing by John O'Donohue:

At the end of the year

The particular mind of the ocean

Filling the coastline’s longing

With such brief harvest

Of elegant, vanishing waves

Is like the mind of time

Opening the shapes of days.

As this year draws to its end,

We give thanks for the gifts it brought

And how they became inlaid within

Where neither time nor tide can touch them.

The days when the veil lifted

And the soul could see delight;

When a quiver caressed the heart

In the sheer exuberance of being here.

Surprises that came awake

In forgotten corners of old fields

Where expectation seemed to have quenched.

The slow, brooding times

When all was awkward

And the wave in the mind

Pierced every sore with salt.

The darkened days that stopped

The confidence of the dawn.

*

Days when beloved faces shone brighter

With light from beyond themselves;

And from the granite of some secret sorrow

A stream of buried tears loosened.

We bless this year for all we learned,

For all we loved and lost

And for the quiet way it brought us

Nearer to our invisible destination.

(John O'Donohue in Benedictus: A Book Of Blessings)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Spring

You and I have known the winter months –

The company of rain, the diminished light,

the sight of our breath before us when the air is cold.

And perhaps you have known the impulse to withdraw into yourself –

as if a part of yourself wants to hibernate,

wants to go underground.

Winter is a time for waiting, resting, conserving, even for enduring.

And with waiting and resting comes trusting –

trusting that a new season is on the way;

a season of renewal and rebirth where we come to appreciate

just how much life has been truly dormant within us –

gifts of creativity, stores of hope and wonder,

among the many unrealised realities of our lives.

The Loving and Creative Presence of God

sweeps across these dormant parts of us this day.

Come, let’s open our lives to a season of surprise,

that might include the wonders of spring

arising from winter’s hardships.

Come and be, just as you are.

0 notes

Text

The Things That Make for Peace

LUKE 19:28-40

If you listen carefully there is a beat,

a rhythm, a melody;

creation is singing!

The stones cry out (Luke 19:40),

the mountains dance (Ps. 114:6),

The sun and the moon both praise (Ps.148:3).

The stars shine while the trees sway

and clap their hands in time (Is.55:12).

Do you hear creation sing,

singing the song of jubilee?

This is the music of Creator

that sets all the captives free

On a trip to the zoo with my son a while ago we came across an aviary featuring a number of Australian birds. I looked at the names of the resident birds with casual interest until I noticed that this aviary included the regent honey eater – one of Australia’s most critically endangered birds.

Once you could observe flocks of hundreds of the Australian songbirds across south-eastern Australia. Now the numbers have dwindled to only a few hundred in the wild. Here we were, up close with a creature on the brink. I’m not sure what the feeling was. It was something like a brush with fame wrapped within a larger blanket of grief.

The tale of the regent honeyeaters endangered status features familiar storylines about human devastation of natural habitats. They’ve also been coming off worse for wear on the competition front with the larger, more aggressive nectivores (noisy friarbirds, red wattlebirds, noisy miners etc). The challenge of competition has been exacerbated by the strategy of imitation. These striking yellow and black birds have been mimicking the calls of neighbouring bird species – possibly as a ploy to avoid getting “their heads beaten in as much.”[1]

While mimicry may help the regent honeyeater to avoid some scraps with other bird species it is doing little to help them with prospective mates. The females are not interested in impressions of the friarbird, the currawong, or the cuckooshrike. And with populations of regent honeyeaters so low the young males are not getting a chance to learn mating calls from other regent honeyeater adults. They are forgetting their own love song. The females are listening out for the old familiar love call but it cannot be heard. It is this loss of their own melody and song, according to recent studies[2], that is contributing to the endangering of the regent honeyeater.

* * *

In another time and place a young Jewish rabbi stirs the hopes and imaginations of a beleaguered people. They dare to believe that they could be on the cusp of a new revolutionary moment in history. As he journeys with his followers towards Jerusalem this young Nazarene has been sparking Exodus dreams. His liberating presence and teaching have awoken deep memories in a people. It’s as if they’re hearing with fresh ears a forgotten composition written especially for them that reverberates with cadences of freedom and peace and restoration.

As they approach Jerusalem a crowd has gathered. They fix their hopes on the one who enters Jerusalem on a young donkey, a lowly beast, just how the ancient texts said the Messiah would come (Zech. 9:9). This was the moment they have been waiting for - a royal occasion to confirm the people’s hopes!

As Jesus passed through the crowd the people spread their cloaks (their symbols of status) on the road before him and began joyfully praising,

“Blessed is the king who comes in the name of the Lord!”

“Peace in heaven and glory in the highest!”

These were songs reserved for those who carried the nation’s hopes, for royal figures who would bring heaven’s peace to earth. Jesus doesn’t shy away from the magnitude of the claims, the people are singing in tune: Jesus is king! Jesus is God’s special representative, the salvation-bringer! The dreams of the people are going to come true!

The occasion is not lost on the Pharisees in attendance. The old-guard leadership don’t have the same ear for the song. They try and get the disciples to quit with the royal procession:

“Teacher, order your disciples to stop.” (v39)

The Pharisees won’t stand for these dangerous and provocative assertions. They won’t dance for Jesus. N.T. Wright writes,

‘They were looking for a singer to sing the song they had been humming for a long time, but he was the composer, bringing them a new song to which the old songs they knew would form, at best, the background music.’[3]

His lowly disciples know the tune but the people of stature are given headaches. There is nothing they can do to halt proceedings now though. Even if the orchestra of disciples were silenced the stones themselves would cry out (v40). They are too late in their efforts to drown out this movement with their old-time music.

In the midst of the celebration, however, Jesus seems to be the only person who knows the next verse. The people sing and cheer but Jesus will weep. As he sets his eyes on the city that rejects him and remains blind to the ‘things that make for peace’ his heart will break with divine love and grief.

The dreams of the people were indeed coming true, but not in the way they had imagined. After all, Jesus is a different kind of king, the type of king who makes a spectacle of violence and power by riding into Jerusalem on a donkey instead of a mighty war horse, the kind of king who will disarm and expose the tyrants not with the might of the sword but with the humble obedience of the cross.

If the world has known such a song it has been long forgotten. The predicament of the regent honeyeater is the predicament of God’s own people. They have forgotten their love song. They are out of tune with the divine symphony. They have instead learnt the songs of their surrounding neighbours. They no longer know the things that make for peace (v42).

But Jesus knows this freedom song intimately. Jesus is the conductor of the song. His being and selfhood is bound up in profound solidarity with the composer. Jesus sounds the call that resounds with liberating promise and hope for all.

When I think about what it really means to be human, to be most fully alive, or however else we might describe these things, I think it has everything to do with somehow singing in tune and moving in time with this song about peace; a peace which is also about justice, and wholeness, integrity, the dignity of all, grace, and of course profound love.

As much as we might find ourselves humming along to rival songs regularly, I think it’s the mysterious song playing all the time in the most sacred parts of every human being. And you can be playing right along in perfect pitch and not have a clue that you’re doing it. But sometimes we do. Maybe it’s a moment, an interaction, an activity, and on some level you know you are playing in rhythm, singing in tune with the Creator’s love song.

I can think of at least a couple of times where I was at least conscious of that in some way this week: moments where I listened in a way that reminded others of their strength and helped them to find their joy at a time when they needed it. I could see a spark in their eye and a lightness in them, at least a small moment of grace that came through our connection.

Or there was this other time this week where I watched someone fully embrace the contribution that they could make in stuffy places that needed the kind of creativity and joy that they could bring as an artist. And as I was paying attention to the way that they seemed to be playing in tune with Creator’s song in such a beautiful way I could see how some of the ways I’d been able to walk with her along the way had captured something of the melody of this beautiful divine song that brings us alive and makes the world hum with goodness and light.

Scan your week reflecting on times where you’ve noticed caught yourself humming that old love song in your words, your actions, in your relationships.

We’re all human here so you don’t have to worry about those times you messed up a line here or there or sang out of tune, but just take a moment to reflect.

To come back to Jesus in our Palm Sunday story, and as we ourselves prepare our hearts for Easter, we know that as the story moves along that the song of the Creator is going to involve devastating sorrow. Jesus knows the next verse won’t sound right to the crowds, that it will cause great heartache and confusion for a time. But when the song plays right through all will be made right and beautiful. Weeping will turn to joy and the great love song that changes the world will carry on.

Best of all this song can be heard if we have ears to hear. Jesus still leads us and stretches his hand out towards us from among the crowds. Jesus is the songbird who carries the melody of our forgotten love song. He is the one who come into our midst, teaching us this song of jubilee. He invites us to take our own place in the anthem, to raise our voices, to dance for justice, to be caught up in the freedom journey that brings new life and marches towards peace for all.

I don’t know how it’s all going to happen exactly, but I trust and hope that this song will keep changing lives. And it should because it’s a beautiful song. It’s for everyone. And it’s a love song that transforms us from the inside out.

May we have ears to hear the divine symphony - right through to the end. Lord, help us to sing and dance along.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/mar/17/how-an-endangered-australian-songbird-regent-honeyeater-is-forgetting-its-love-songs

[2] https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2021.0225

[3] Simply Jesus: A New Vision of Who He Was, What He Did, and Why He Matters (N. T. Wright), p.5

1 note

·

View note

Video

https://theopentable.tumblr.com/post/43838609160/a-battleground-of-desire

Luke 13:31-35

Someone go and tell that Jesus

It’s not safe runnin’ that kingdom business

Leave this place and go to somewhere else

‘Cause Herod’s huffing, And Herod’s blowing

If you know what’s good, yeah you’ll get going

Leave this place and go to somewhere else

But he just dug in his heels

He’s got demons to cast, and people to heal you see

Go and tell that fox to find a hole

I’m not leaving until I reach my goal

O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, you who kill the truth and can’t believe

O how I’ve longed to gather all the kids together

Like a hen caught in the fire

I’d keep you safe but you don’t desire

You don’t desire me

You don’t desire peace

But one day, you’ll say

Blessed is he

that comes in the name of the Lord

0 notes

Text

Jubilee Vision

Luke 4:14-21

In January this year Oxfam released a fresh report on global inequality that charts the way inequality has worsened during the pandemic pushing over 160 million people into poverty.[1]

However, this isn’t the case for everyone with the last year being described as the best year on record for the super-rich.

· Over the past two years, the wealth of Australia's 47 billionaires has doubled to $255 billion.

· That is more wealth in the hands of 47 people than about 7.7 million Australians.

· Globally, the world's 10 richest men have more than doubled their fortunes to $1.9 trillion, at a rate of $1.6 billion a day – that is more wealth than that of two-thirds of humanity.

· The highest 20 per cent of the wealthiest people in Australia are earning 90 times more than those at the lowest 20 per cent.

· Meanwhile, the bottom 40 per cent are hanging on by a thread.

· The report states that, based on its findings and "conservative estimates", inequality is contributing to the deaths of at least 21,300 people each day.

Oxfam is urging governments to consider a 99 per cent, one-off windfall tax on the COVID-19 wealth gains, calling the inequality a form of "economic violence".

The report indicates that inequality kills. There are very real deaths as a consequence of our inability to more effectively distribute the benefit of our economies.

What is not commonly well known is that the overall health and wellbeing of a population is determined not by a country’s wealth but by how evenly that wealth is distributed. In other words, it benefits everyone to live in a more equal society, not just the poor.

Why? It’s not just to do with a lack of access to things like healthcare or the way poorer communities rely more on things like fast food. The most significant factor is the stressful psychological experience and political instability of being disempowered and marginalised.

Inequality erodes social trust, cohesion and solidarity. What comes with significantly unequal societies is higher levels of violence, often as a result of people feeling disrespected and powerless, along with higher rates of mental illness, crime, alcoholism, addiction, homicide, and incarceration.[2]

A healthy society rises together.

A healthy society doesn’t leave some behind while others get ahead.

A healthy society gets that our collective wellbeing is tied up in our shared destiny.

How does all this research and all these reports speak into Luke’s passage?

In our text from Luke 4 Jesus reads from a scroll handed to him in his home town synagogue and declares that he is the anointed one – God in flesh, the long-awaited Messiah who is coming good on the great hopes of the worlds troubled people –

the poor,

the blind,

those locked up behind bars,

the oppressed.

Jesus states that he is initiating a great movement of liberty and restoration; this is what Jesus is about.

When Jesus announces the year of the Lord’s favour he is identifying his messianic role with some of the most electric and challenging themes found in the Hebrew scriptures, memories and measures that promise great social and spiritual upheaval: Jubilee.

Jubilee prescribed a social, political, and economic blueprint for the people of God that ensured that natural, human and financial resources could not be controlled by a small minority.

In seven year cycles land was given a vacation from endless cycles of reaping and sowing, slaves were released and debts cancelled.

The biggest shake-up was reserved for the fiftieth year: all land was returned to those who originally owned the land.

This is institutionalised grace to counter human greed, mandated generosity to defend and protect the helpless!

The jubilee mandates presume that bad luck and misfortune are going to part of the story but it’s what happens after that is instructive.

Without these jubilee mandates it can be assumed self-interest will call the shots.

Another’s loss is my gain.

Perhaps, we rationalise, we were smarter, worked harder, therefore we are entitled to the benefits that come our way.

Of course, if you entrench these opportunities and disadvantages over long enough the gap between the rich and poor, the lucky and the unlucky, those who inherit and the disinherited becomes far wider.

The jubilee mandates tell us to expect these kinds of gaps to form and for this kind of entitlement and hard-heartedness to creep into our human experience.

So jubilee comes and it breaks the cycle and wipes the deficits, the debts, the disadvantage. Everyone gets a fresh start.

Even those who have destroyed their lives through poor choices get a fresh start.

And no one gets so far ahead that they’re wealthy beyond what they would ever need.

This was incredibly good news to those who came upon hard times; there were rhythms that would see them back on their feet.

When Jubilee happens compassion is the order of the day.

Structures that generate inequality are dismantled and freedom reigns.

You could argue that jubilee insists that we are all in this together; and when one is experiencing some kind of lack then it is a community issue that needs to be corrected. Jubilee imagines that those with extra will be part of the solution.

According to economic anthropologist Jason Hickel, the cost of bringing everyone in the world above the poverty line of $7.40 per day and to provide universal healthcare for every person in the global South is $10 trillion. While it sounds like a lot of money, it’s only half the annual income of the richest 1%. Hickel says,

“By shifting $10 trillion of excess annual income from the richest 1% to the global poor, we could end poverty in a stroke, and boost life expectancy in the global South to eighty years – eliminating the global health gap. And the richest 1% would still be left with an average annual household income of more than a quarter million dollars: more than anyone could ever reasonably need, and nearly eight times higher than the median household income in Britain. And that’s just income; we haven’t even touched wealth. The richest 1% have accumulated wealth worth $158 trillion, which amounts to nearly half of the world’s total.”[3]

Jubilee also prescribes a spiritual blueprint that draws people into freedom through forgiveness and healing relationships.

Jesus knows that our hearts can become like prisons, that we carry deep wounds from the ways we both hurt and have been hurt and dehumanised by others, that we can find ourselves trapped in our own bitterness, fear, guilt, shame, and insecurities.

These things colour the way we see ourselves, the way we see God, the world around us.

We need release and restoration here too.

We need to know that God is for us, that we can rest in God’s favour and kindness.

This is what Jesus does.

‘He cuts the chains of sin. Our eyes open. The handcuffs of evil drop off. This is true liberation. We repent and turn back to the garden, rekindling harmony with God—finding a place once more in God’s family’[4]

With this reignited Jubilee vision Jesus is ushering in a new age of grace – a world without poverty and injustice, where people are drawn into wholeness and freedom with God, with others and within themselves, where all things are restored to their original state.

And not just for the insiders. Jesus announces that this good news knows no socially determined barriers (much to the ire of the hometown crowd).

Jubilee for everyone! Grace for all! God is always better than people imagine. This is grace that ruins us; grace that turns our world upside-down.

Grace received is to become grace shared: communities of people forgiving as we’ve been forgiven, practicing generosity, releasing the captives, giving the land rest, experiencing wholeness – this is Jesus’ Jubilee vision.

May we have such a compelling experience of grace that we are ruined for good – literally, ruined to such an extent that we have only goodness and generosity to share with others, that it’s only natural to take part in the same forgiving, including, sharing, blessing that we know so well.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/jan/19/millionaires-call-on-governments-worldwide-to-tax-us-now?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

[2] See Jeremy Lent, The Web of Meaning: Integrating Science and Traditional Wisdom to Find our Place in the Universe (New Society Publishers, 2021), pp.224-226 and Jason Hickel, Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World (William Heinemann, 2020), pp.178-179

[3] Jason Hickel, Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World (William Heinemann, 2020), pp.191-192

[4] Donald Kraybill, The Upside-Down Kingdom (Herald Press, 2018), p.93

0 notes

Text

Living Creatively and Sustainably in a Pandemic

BAPTISM OF THE LORD

LUKE 3

Three thoughts, three poems, and a Nouwen quote for a wilderness people who are baptised in love (Luke 3).

As we begin this third year in a pandemic, how do we live sustainably and creatively with uncertainty?

1. We need places to name our experience.

John leads people a people longing for more into the wilderness. Here they can name their experience and express their sorrow, their fear, and uncertainty. Our tears, as the 14th century Sufi mystic Hafiz described, bring life to the fields we will one day walk in:

It is not possible to complete yourself without sorrow.

So endure sadness the best you can when its season comes.

Meanwhile, unbeknowst to you a sun takes birth in a sky you will one day know

and the tears that fall from your eyes bring life to a field you will someday walk in.

2. We can find ways to let the beauty we love be what we do – even in the face of fear, uncertainty, despair, and disappointment

Hailing from the priestly class, John turns his back on the security, privilege, and rewards that the old order would have held for him. Despite his credentialled assessment of the failings and limitations of the old order and the wilderness reality he is immersed in, John gets on with playing his own part in bringing forth the new world on the way.

Rumi, another Sufi mystic of old, offered these words:

Today, like every other day, we wake up empty and frightened.

Don’t open the door to the study and begin reading.

Take down a musical instrument.

Let the beauty we love be what we do.

There are hundreds of ways to kneel and kiss the ground.

3. We find our centre in the sacred voice of love

John speaks of two baptisms – a baptism of water and of fire. John points to the way we find our centre through encountering the sacred voice of love. It is this inner experience of love that offers the stability we need even when we are a wilderness people. Here is one final Hafiz poem:

Friends, understand this:

In the ledger of the world each of us is already marked eternal;

each of us already carries that brand.

You may refuse and avoid that title now,

but on the final day it will be revealed in you.

So why wait until then to learn what can be discovered in the here and now?

When you know who you really are you can work outside the system; against the grain of conformity and convention. You can march to the beat of a different drum. You don’t have to fear the voices of traditional power in the same way. You are marked eternal. Which means you can live transparently. You can be bold and creative, letting the beauty you love be what you do.

Or, as Henri Nouwen wrote in his book, Spiritual Formation: Following the Movements of the Spirit,

“If you believe that you are beloved before you were born, and will be beloved after you die, you can realise your mission in life. You are sent here just for a little bit—for twenty, thirty, forty, fifty, or sixty years. The time doesn’t matter. You are sent into this world to help your brothers and sisters know that they are as beloved as you are and that we all belong together in God’s family.

We are sent into this world to be people of reconciliation. We are sent to teach and heal, to break down the walls that divide people into different categories of value. Young, old, black, white, gay, straight—whatever divisions you can come up with—Serb, Croat, Muslim, Jew, Catholic, Protestant, Hindu, Buddhist—beyond all those distinctions that separate us, there is a greater unity. Out of that essential unity you can live and proclaim the truth that every human being belongs to God’s heart, which beats from eternity to eternity. The mystery of God’s love is that when you know in your heart that you are chosen and blessed, you also know that others are chosen and blessed, and you cannot do other than embrace all humanity as God’s beloved. Precisely as we confront life and death in all its many facets, we can finally say to God: “I love you, too.””

Though we may wake up, or start the year, feeling empty and frightened we can be a people who confront life and death in all its many facets.

We can say to God, "I love you, too."

We can let the beauty we love be what we do.

We can kneel and kiss the ground in hundreds of ways.

What is the beauty you love? How might this become what you do despite the temptations you feel to hide or numb yourself in distraction?

What will be your creative act in the face of your wilderness experience?

What are the ways you might kneel and kiss the ground?

#hafiz#rumi#the gospel of luke#john the baptist#baptism of the lord#Year C#uncertainty#love#henri nouwen#pandemic#creativity#beauty

0 notes

Text

A World of Meaning

SECOND SUNDAY AFTER CHRISTMAS DAY

Year C

January 2, 2022

John 1:(1-9), 10-18

Is there a logic that orders the universe?

Does the universe exist, as some say, according to the logic of rivalry where only the strongest survive?

Or perhaps according to the logic of compliance in which our job is to learn the rules and appease the powerful and those in the 'inner circle'?

Is the universe one big machine governed by the logic of meaningless mechanism where we live our lives according to whatever pleasure, power, or security we can lay our hands upon?

John tells us that the cosmos is made sense of in the logic, meaning, wisdom, and pattern found in the life of a poor man -

Jesus,

the logos,

the word made flesh,

a life-light shining in darkness

- who wandered across the land with a band of students and friends,

telling stories,

confronting injustice,

helping people in need with profound compassion and costly love.

Could it be that this logic of creativity, goodness and love embodied in Christ is what ultimately governs and orders the cosmos? [1]

And if so, what might this mean if we allowed this logos of love to be the pattern for our lives?

(Adapted from Brian McLaren's book We Make the Road by Walking: A Year-Long Quest for Spiritual Formation, Reorientation and Activation)

[1] As we ponder this notion we might consider the way that our nomadic hunter-gatherer ancestors saw nature as a 'giving parent' and how many Indigenous people today see living beings as part of a vast extended family.

Similarly, in traditional Chinese thought, the universe was understood to be an interconnected web with the ultimate human goal to attune with the harmonic web in which we are all embedded.

Insights from cellular biology reveal that through symbiosis, species have co-created ecosystems in which the whole is far greater than the sum of the parts.

In other words, science is revealing that life advances (mutually flourishes) not by combat, but rather by networking, cooperation, reciprocity, and gratitude.

Dare we call this love? (See Jeremy Lent's book, The Web of Meaning, 2021).

0 notes

Text

But Not So Among You: Becoming an Alternative to the Politics of Domination

Mark 10:32-45

The Zebedee brothers come to Jesus trying to arrange positions of great honour and status in the coming cabinet reshuffle within the new government:

35 James and John, the sons of Zebedee, came forward to him and said to him, “Teacher, we want you to do for us whatever we ask of you.” 36 And he said to them, “What is it you want me to do for you?” 37 And they said to him, “Grant us to sit, one at your right hand and one at your left, in your glory.”

They like the themes of a new order emerging but they haven’t grasped the repeated hints that this is a different kind of order. Throughout Mark’s gospel Jesus has been engaged in a struggle against the politics of domination represented by the social structures and groups that perpetuated the oppressive symbolic orders and dominant ideologies at work within the world of Jesus and his contemporaries (i.e. the Jewish temple state and the Roman imperial hegemony).

James and John think that the old guard is simply going to be replaced by a fresh new cohort. But Jesus’ program has never simply been about fresh faces. Jesus is calling people to an alternative way of exercising power – a departure from the ways rulers use their strength to dominate (“power over”). That’s how the Gentile rulers exercise their power. But not so among you.

In Mark’s gospel we are brought face to face with a leader who comes not to be served, but rather to serve and give his life as a ransom for many (10:45) – a clear redefinition of the triumphalist expectations of glory and dominion expressed in the request of the sons of Zebedee for positions of power by Christ’s side (Mark 10:35-40).

Jesus’ practices and presence amount to a vastly different operation of power. As Warren Carter articulates,

‘He forbids followers to imitate imperial “power over” (10:42-43) and urges an alternative identity of being slaves, of using “power with and for” the benefit of others (10:43-44). He himself commits to being a fellow slave rather than a master and performs this identity in his death. It is “for many” in that it models the alternative way of life that contests, resists, and suffers at the hands of imperial structures of power.’[1]

Jesus advances entirely new political and economic practices – a “revolution from below” - that is both subversive and constructive, a new order centred around the community of discipleship which is guided by the what Ched Myers describes as the politics of servanthood and the ideology of receptivity.[2]

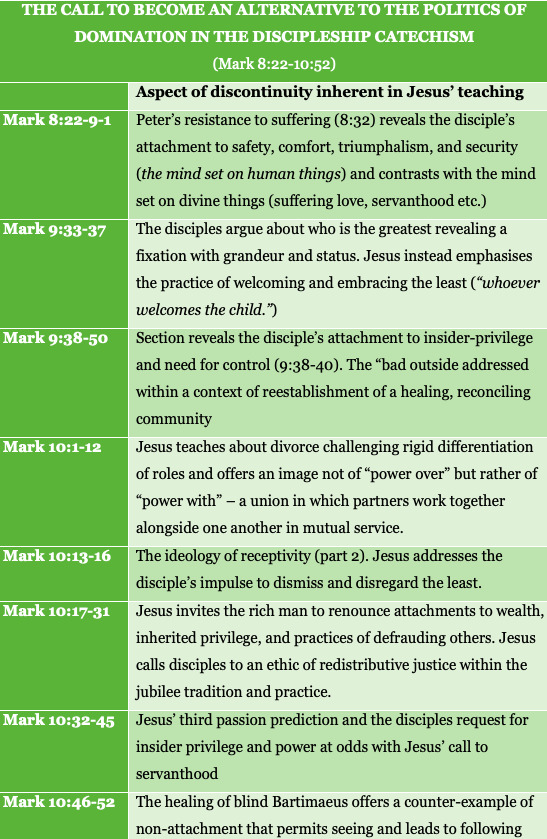

What’s clear throughout Mark’s discipleship catechism (Mark 8:22-10:52) is that the disciples repeatedly fail to grasp and embody Jesus’ politics of servanthood:

Jesus’ disciples aren’t the only ones who have an unhelpful relationship with power. We regularly reproduce and cling to “power over” forms of leadership in our own spheres.

Brené Brown talks about how power over leadership[3] is guided by a belief that power is finite. This kind of power uses fear to protect and hoard power. Fear is leveraged to divide, destabilise, and to devalue. This kind of power looks for others to blame and shame (scapegoat) for their own discomfort as a way of maintaining power. The dangerous consequence is located in an ever-increasing capacity for dehumanising cruelty and bullying, for inciting hatred and violence – especially towards those who are most vulnerable.

In contrast, leadership that works from a position of power with/to/within believes that power becomes infinite and expands when shared with others. In place of fear, this kind of power leverages empathy, respect, and connection as tools for uniting and stabilising. This kind of leadership is able to recognise that discomfort is part of the human experience and, rather than shaming and blaming, moves towards transparency, accountability, and vulnerability.

Leadership as power with is understood as a responsibility to be in service of others rather than to be served by others – Jesus’ own understanding of his vocation and the very heart of the politics of servanthood.

The challenge for the Zebedee brothers remains the challenge for all of us – we cannot resist the politics of domination while reproducing the very same patterns in our lives. We must form communities of discontinuity who take seriously the ways we must continually lay aside our attachments to the practices and politics of domination. In the process we will need to find new ways to relate to our own vulnerability, our insecurities, our own smallness. Unless we find a way to do this we will be driven by our need to compensate, to have power over. We must become a people who can make peace with our discomfort, to allow God to meet us here, to attend to our own wounds. That’s where we can discover power within. Only then will we be able to welcome the vulnerable one into our midst as Jesus calls us – to be become servant communities who are genuinely receptive, compassionate, and inclusive – communities given to the common good.

[1] Warren Carter, Mark: Wisdom Commentary (2019), p.294

[2] Ched Myers, Binding the Strong Man

[3] https://brenebrown.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Brene-Brown-on-Power-and-Leadership-10-26-20.pdf

#Gospel of Mark#discipleship#Year B#Politics of domination#Politics of servanthood#revolution from below#power within#power with#power over

0 notes

Text

A Future Not Our Own

In the movie Horton Hear’s a Who, Horton has been desperately trying to keep a tiny little speck on a flower safe because the speck is actually a whole world called Whoville with lots of tiny people on it, including a mayor who has 96 kids.

The problem is that no one believes Horton – he’s the only one able to hear the cries of the tiny people on the speck (because of his big ears).

So everyone around Horton becomes convinced that Horton is both mad and a bad influence.

The unhearing, disbelieving mob back Horton against a wall to try and destroy the speck to end Horton’s madness once and for all.

But Horton won’t give up no matter how dangerous things became for him personally. Horton had an ache for justice.

Horton knew that a person is a person, no matter how small – he knew we need those with a voice to stand up for the little guys so that those hard-of-hearing can learn to hear.

In a last-ditch effort Horton urges all the Who's in Whoville to raise their voices to save their lives.

Ultimately it is the addition of the mayor of Whoville’s son's voice that pierces the sound barrier so that the mob can begin to hear.

One voice can change the world. One courageous and stubborn elephant, or person, can change the world.

Imagine what kind of world would be possible if we all used our voices, and indeed our whole lives, together to make the world a better place.

But it takes a willingness to go out on a limb. It needs people willing to raise their voices.

Our story about Horton and Who’s on Whoville might sound a bit crazy but there’s similar stories playing out all the time.

One of those stories is about the planet itself. Lots of our best scientists are saying the planet is in danger if we don’t find some better ways of caring for the earth.

But just like Horton the crowds all around haven’t been great at hearing the voices saying “we are here, we are here, we are here!”

So today, at the end of the service, we’re going to make as much noise as we can about how we’ve all got a job to do together to protect God’s wonderful creation.

We’re going to stand up for the planet so that those hard-of-hearing can learn to hear.

* * *

It helps now and then to step back and take a long view.

The Kingdom is not only beyond our efforts,

it is beyond our vision.

We accomplish in our lifetime only a fraction

of the magnificent enterprise that is God's work.

Nothing we do is complete, which is another way of

saying that the kingdom always lies beyond us.

No statement says all that could be said.

No prayer fully expresses our faith. No confession

brings perfection, no pastoral visit brings wholeness.

No program accomplishes the Church's mission.

No set of goals and objectives include everything.

This is what we are about. We plant the seeds that one

day will grow. We water the seeds already planted

knowing that they hold future promise.

We lay foundations that will need further development.

We provide yeast that produces effects

far beyond our capabilities.

We cannot do everything, and there is a sense of

liberation in realizing this.

This enables us to do something, and to do it very well.

It may be incomplete, but it is a beginning,

a step along the way, an opportunity for the Lord's

grace to enter and do the rest.

We may never see the end results, but that is the

difference between the master builder and the worker.

We are workers, not master builders, ministers, not

messiahs. We are prophets of a future not our own.

- A Future Not Our Own (Attributed to Oscar Romero)

LEGACY

We’ve come to the end of our Tree of Life series and we’re left with this notion of legacy.

We’ve allowed the biblical imagination to shape our own self-understanding –

We are a tree people.

We are invited to eat from the Tree of Life – drawing from God’s own life and wisdom to nourish our beings.

Jesus himself emerges from the stump of Israel as a new shoot that brings hope and life – transforming the cursed tree of the cross into a tree that brings healing to the nations.

Jesus is the great tree, the peace tree – the true vine – and when we’re connected to Jesus we bear fruit.

And the kingdom of God itself emerges from a tiny seed to become a wonderful tree where all the diverse bird populations can come and make their home among the branches.

And so we’ve reflected on what kind of tree this community is.

We’ve reflected on what kind of fruit it has produced.

And today we will plant a physical tree in the soil just outside these walls.

We plant it as a way of recognising and honouring what has gone before – the history of this place, the significant people and influences that have shaped this community at Para Hills.

We will plant it conscious of the values that have embodied by those past and present.

When we invited the young ones to stomp the clay a couple of weeks ago we sought to learn about and honour the toil of those who have gone before us and who are still among us, allowing them to draw us into a bigger story.

This is legacy work. And it continues today.

The tree we plant today is already established in some ways – it’s off and away, it already has a history.

But it has much more growth to go.

So as we plant this tree we stake a claim in the future.

We envision a time when the tree will bear fruit – something delicious, something with rich vitamins and minerals that boost the healing capacities of not just our lives, but hopefully our neighbours also.

The tree is located between the building here and the community. Perhaps people from the community might reach and eat from the tree. Perhaps our fruit might be a blessing for our neighbours.

It might look like a humble tangelo tree but it is a symbol of who have been and who we are called to be.

From little things, big things grow, as Paul Kelly and Jesus remind us.

The reading we heard earlier was attributed to Oscar Romero who was a priest in El Salvador speaking out about injustices there.

He was shot in 1980 while celebrating mass.

His words remind us that we are not messiahs but simple workers in our communities who may not even see the results of our work in our lifetime. Our work is beyond our vision.

But we participate nonetheless, with patience and hope.

From little things, big things grow.

We are a tree people who want to stake a claim in the future.

Because we take legacy seriously

* * *

So we will get to planting the tree later today as we conclude our time in here.

But alongside our local legacy story here today there is also a global legacy story that we need to pay attention to.

I want you to imagine for a moment that we had built a train and on that train was a bomb that was set to explode some way off in the future.

Now we don’t know exactly when it will go off but we know in no uncertain terms that the train leaving our station will create future devastation.

In an oversimplified way this is our current climate situation.

We’ve recently been handed the most recent IPCC report which, as part of its review of over 14,000 scientific articles, has found that climate change and its impact are undeniably accelerating.

Heatwaves, droughts, floods, heavy downpours and other extreme weather events are getting worse, driven by the burning of coal, oil and gas.

Ultimately, the report finds that our decisions this decade will be the difference between a liveable future for today’s young people, and a future that is incompatible with well-functioning human societies.

The report explains to us that the decisions we make now will resonate for centuries or millennia.

Professor Will Steffen says that,

“The right choices will be measured in lives, livelihoods, species and ecosystems saved. The benefits of stronger action will be particularly important for our children and grandchildren.”

He adds,

“Some long-term impacts cannot be avoided, particularly rises in ocean temperature and sea level. Importantly, however, strong and sustained emission reductions this decade can slow these trends, stave off much worse, and protect so much of what we cherish.”

Professor Will Steffen highlights, the report is unequivocal about the urgency of climate action. He says,

“No political leader or decision maker reading this landmark report will be able to claim they were unaware of the profound threat we face.”

And of course, we ourselves have to wrestle with these confronting realities. As earth system scientist Johan Rockström describes,

“We are the first generation to know that we face unprecedented global environmental risks, but at the same time we are the last generation with a significant change to do something about it.”

* * *

In the Uniting Church we have already affirmed that we need to make firm commitments. At the 15th Assembly we acknowledged that God calls us into a particular relationship with the rest of creation – a relationship of mutuality and interdependence which seeks the reconciliation of all creation with God.

And with this came a range of acknowledgments and commitments including urging the government to divest from fossil fuels and to accelerate the transition to renewable energy.

In the words of the 2018 Assembly proposal, we affirmed that ‘for the whole of Creation, the time for action is now.’

This is legacy work.

For our children. For our grandchildren. For the whole creation.

This planet is the only one we’ve got.

And it just happens to be our life support system.

And unfortunately we’ve set a train in motion that is loaded with a bomb that is set to go off creating all kinds of devastation unless we act now to mitigate the future impact that will come.

The whole creation is groaning.

The creation groaning, and waiting.

What is creation waiting for according to Romans 8?

All of creation is waiting with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God (Romans 8:9, 22).

Creation is waiting for us to be who we are.

To be God’s people.

To love the created order like God does – laying down our lives, becoming faithful stewards, loving our neighbours.

And just who is our neighbour we ask?

Do we dare to include our neighbours in the pacific oceans whose low-lying islands will become swallowed up by rising seas?

Do we dare to include our neighbours who are just starting out their journey on this planet?

Perhaps our answer rests in our ability to hear the pain of the world.

Do we hear the warnings of the scientists?

Can we hear creation groaning?

Are we noticing the extinction of the species all around us?

What does it mean to us that our catastrophic fire days are far more frequent?

How do we make sense of the coral bleaching events taking place far more regularly on our Great Barrier Reef?

What can you hear?

Not everyone can hear the sounds. Not everyone wants to.

Some will think you are crazy.

Others will think you are a bad influence.

Horton’s courageous and stubborn efforts made him unpopular.

But he knew that a person is a person, no matter how small.

And he knew that those with a voice needed to stand up for the little guys so that those hard-of-hearing could learn to hear.

And he trusted that our voices can change the world.

That our actions can change the world.

So in a moment that’s what we’re going to go and do – we’re going to plant a tree and we’re going to make a noise.

Because we’re a tree people who want to stake a claim in the future.

And we take legacy seriously – locally and globally.

And because God loves the whole world in a profoundly costly way.

It while our actions and the noise we make might only be a small thing we do so knowing we will be joining faith communities all around the world making a shared sound together.

And maybe, just maybe, we’ll change the world.

#IPCC Report#climate change#ecology#Oscar Romero#Tree of Life#Faiths4Climate#SacredPeopleSacredEarth#KillingThePlanetIsAgainstMyReligion#Green Faith

0 notes

Text

https://radicaldiscipleship.net/2021/10/06/reading-jesus-and-the-rich-man-on-indigenous-peoples-day-redistributive-justice-and-a-discipleship-of-decolonization/?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=facebook&fbclid=IwAR2r4u3z4dNeUK7z9r3emT7yU7fQ95Em9Y-s0RWTWUSHFWbmeTXgGb2Yj0s

#gospel of mark#year b#redistribution#justice#repentance#reparation#wealth#dispossession#Ched Myers#jubilee#discipleship#decolonisation

0 notes

Text

Reimagining Power

PENTECOST 22

MARK 10:1-16

Jesus’ teaching about relationships within the household needs some context for our modern ears. In the ancient world the structures and roles of the household were understood as a microcosm of the larger society. The major voices of figures such as Aristotle proposed that ideal households were hierarchical, patriarchal and centred on male interests. Women, children, and slaves were subjected to patterns of domination which included rigid gender differentiation, hierarchy and privileging of male power and status. This is an important part of the context we need to keep in mind when approaching Jesus’ teaching in Mark 10, which, as Warren Carter writes,

‘seeks to shape, in a society saturated by male domination and “power over” structures”, an alternative community that much more embodies “power for and with.”[1]

Within this context we can understand the query of the Pharisees centring around a male “power over” practice within the context of marriage and divorce (10:2). Divorce was a profoundly demeaning reality for women in a first century context which rendered them extremely vulnerable socially, politically and economically. Jesus’ strong teaching here can be understood in one sense as restraining male power that widely assumed the ease and right of a male to divorce a wife.

Jesus knew from Deuteronomy that male-initiated divorce was lawful with some prohibiting circumstances (Deut 24:1-13; 22:13-21). Jesus draws the conversation away from what is lawful and centres the discussion around what God always intended in marriage. Moses offered concessions for hard-heartedness thus permitting divorce. Jesus instead focuses the conversation on God’s original intention in Genesis whereby marriage results in “one flesh” – a whole new creation (Gen 1:27; 2:24). In Jesus’ teaching it is not the male who is the lord of marriage, but rather God. “Therefore,” Jesus teaches, “what God has joined together, let no one separate” (Mark 10:9).

Inherent in this “one flesh” teaching is a view of marriage that sees it is a reflection of the covenant between God and humanity – a union marked by the kind of divine faithfulness that God has upheld with God’s people despite Israel’s own unfaithfulness (see Hos 14:4-7; Ezek 16:62-63; Mal 2:14).

Jesus grounds the ultimate purpose of marriage in the character of God. Marriage here is not a legal arrangement but rather a deeply committed bond of faithfulness. [2]

Another important insight us that Jesus’ words rendered as “joined together” are more literally translated “yoked together.” Brownson (2013) explains that the image is of a dual yoke, as in pulling a wagon or plough:

‘The focus falls, therefore, on shared productive labour and service. The “one-flesh” union of marriage is not just about mutual satisfaction but about shared service and ministry: childbearing, mutual care, hospitality, and service to the wider community.’[3]

Finally, we have another scene in which the disciples seek to dismiss those bringing children to Jesus to be blessed (10:13-16). The disciple’s impulse to dismiss and disregard the least (10:13-16) reflects their desire for the kind of power and status reflective of the rulers who tyrannise with coercive/ dominating/ hierarchical forms of power (vv35-45). Jesus once again redefines power. He refuses to send the vulnerable and the powerless away and instead affirms that the kingdom belongs to the little children (which would have included children as well as slaves, women, the poor, and the sick) – another affront to the normal structure and nature of households shaped by “power over.”

Understanding Jesus’ teaching about marriage fits within a larger context in which Jesus reimagine and redeploys power in a world where the politics of domination are the norm. Jesus restrains male power. He locates marriage within a bond of loving faithfulness. He challenges rigid differentiation of roles and offers an image not of “power over” but rather of “power with” – a union in which partners work together alongside one another in mutual service. Jesus reminds his audience that marriage is ultimately located in the character of divine love and givenness - a kind of givenness and servanthood that ultimately draws the powerless and vulnerable into communities of belonging defined by divine faithfulness and blessing.

[1] Carter, W. Wisdom Commentary: Mark (2010), p.265

[2] The later traditions we find in Matthew 19 and 1 Cor 7:10-15 help us to recognise that the essential purpose of God needs to be met with pastoral discernment and sensitivity for the many difficult and complex situations people experience in marriage which include can include great hurt, brokenness and oppression.

[3] James V. Brownson. Bible, Gender, Sexuality: Reframing the Church's Debate on Same-Sex Relationships (2013), p.99

0 notes

Text

The Good Outside and the Evil Within

PENTECOST 21

Mark 9:38-50

A few years ago I was serving in my first parish placement in a regional town. What I didn’t know at the time was that we were situated on a theological fault line and the ground between us was about to shake as wider conversations within the denomination about same-sex marriage took place. These tremors uncovered bitter and harsh realities I’d never experienced in church life. Some of it was really ugly and painful. At the same time my other work in a Christian organisation was imploding in its own messy way. It’s always hard pinpointing exact causes but it’s enough to say that in both contexts matters of power, control, status, and security were seismic features of the earthquakes that hit. All of this was combined with homelife that included being neck deep in nappies and renovations. This was an exhausting, stressful and uncertain time.

Part of the fall-out was that I ended up resigning from my parish ministry. The differences between us had become unhelpful and this was the best way of honouring each other. These various tremors landed me in a drug and alcohol rehabilitation centre. Not as a resident, but rather as a drug and alcohol counsellor. I became a member of a therapeutic community centred around recovery.

I hadn’t landed at the rehab by design but the work was genuinely interesting and it gave me a bit of space to make sense of my experiences in the church and the Christian organisation I’d been working for. I didn’t quite know what to do with that fact that the church had been a wounding place. I must admit it was helpful being where Christians largely were not – these more marginal places of vulnerability and struggle that the church often seeks to be insulated from – the bad out there.

That story (the “bad out there”) didn’t really hold water in the rehab. A truer story was that the rehab was a place of resilience and recovery – a place where people took drastic action to get their lives back from the clutches of addiction, trauma, and pain. The rehab was a place of raw honesty, genuine community support, and immense courage. There was no room for pretending in the rehab. And you didn’t need to either. Everyone was in the same boat, with the same yearning for restoration. The rehab was a healing place.

* * *

In Mark’s passage we have a scene where the disciple John comes to Jesus distressed. The disciples have witnessed others casting out demons in Jesus’ name and they try to stop them because these others were not following them (v38). Despite their own ineffectiveness on the liberation front (vv14-19) they want to fix walls around compassionate ministry. They are captive to their in-group bias and narratives about their own specialness. They think of themselves as the good guys, the stars of the show, the heroes. But Jesus isn’t interested in these status, power, and control games:

“Do not stop him; for no one who does a deed of power in my name will be able soon afterward to speak evil of me. Whoever is not against us is for us.” (vv39-40)

Jesus welcomes all who embody mercy, kindness, and justice. He affirms the good out there. He honours and celebrates the healing places.

Having affirmed the good that comes from outside the community the text then narrows in on the bad within the discipleship community – the various ways members might cause other vulnerable followers to stumble or fall away from the path of discipleship. Jesus has already spoke previously about the way some will fall away when tribulation or persecution comes (4:17).[1] Now he turns his attention to the stumbling blocks that can come from within – the problematic hands, feet, and eyes that need to be cut out for the sake of the kingdom (9:43-48).

The language and imagery Jesus uses is drastic. Ched Myers invites us to approach this passage in terms of a community of disciples in recovery. To be in recovery is to be vulnerable; it is to become a “little one” (v42) in need of protection from the lures of addictive habits. I remember one time in the rehab a resident left after a couple of weeks into their time. They weren’t ready for the demands of recovery this time. We wished them well only to discover that they were returning at night trying to sell drugs over the fence to current residents in rehab! Residents had taken drastic action to cut themselves off from the temptations of their old lives and yet here their vulnerability was being exploited by someone who had previously belonged to the healing community. They were causing others to stumble.

Recovery work is hard work. Severance to old attachments is for the most part the drastic kind of action required – like a ‘surgical operation in which a diseased limb is sacrificed in order to save the whole body.’[2] This is the image Mark holds before us in this passage.

To make our way on the discipleship journey is to discontinue the old journeys that bring about a kind of hell on earth. To sustain a new journey requires joining a community of discontinuity.

Myers writes,

‘In this community disciples support one another in their struggle to resist the dominant culture and to practice alternatives. According to Mark’s narrative, such maintenance work is indeed demanding – disciples are forever reverting rather than converting!’[3]

Widening the context, we see that this passage lands within a broader teaching on discipleship (Mark 8:22-10:46) in which the disciples continually demonstrate that their own minds are set on human things rather than divine things. Jesus at three points (8:31; 9:30-32; 10:32-34) points to his own vocation to suffer and serve while the disciples (and other would-be disciples) reveal their own attachments to safety, comfort, triumphalism, and security (8:22-9:1); to grandeur and status (9:33-37; 10:1-16); and to insider-privilege and control (9:38-50; 10:32-45).

What this discipleship catechism offers us is a mini-map of what needs to be cut out for the greater good. As followers of Jesus we are in recovery from our unhealthy attachments to power and control, from status and self-obsession. Jesus has come to save us from our fixations with safety and survival. He has come to liberate us from privilege, wealth and our over-identification with our own group.

Jesus wants to help us to kick the addictions of the domination system. These are the things that cause us to stumble. These are the matters we must take seriously as healing communities.

Our recovery will require great honesty, genuine community support, and immense courage. All of us in the same boat, all with the same vulnerabilities and also the same yearning for restoration.

Jesus’ teaching concludes with words about how everyone will be salted with fire (v49). Some think this might be a reference to the use of salt and fire to close amputated wounds.

The text seems to suggest that wound care is a painful but necessary measure in healing communities, that healing is a hard-won, uncomfortable reality.

Jesus also calls for disciples to have salt in themselves and to be at peace with one another (v50). Some say this points to Old Testament references in which salt is a symbol of the covenant (Lev 2:13; Num 18:19; 2 Chr 13:5; Ezra 4:14). The idea is that to share salt with someone is to share fellowship with them, to remain in committed relationship. Does Jesus here refer to those who have caused others to stumble? Is he saying there has to be a way back into relationship for those who have made mistakes that have brought potential harm to others? In this wider context of exploring the problems within a discipleship community Jesus seems to be calling those in the discipleship community to work for healing, forgiveness, reconciliation, and reintegration back into the community despite the wounds that have been opened up. Wound care involves a relational dimension also. A wounding place must once again become a healing place for all.

[1] “When tribulation or persecution arises on account of the world they immediately fall away” (Mark 4:17, skandalizontai).

[2] Brendan Byrne, A Costly Freedom: A Theological Reading of Mark’s Gospel, p.155

[3] Ched Myers, Who Will Roll Away the Stone? p.175

0 notes

Text

Life without Ladders

PENTECOST 20

Mark 9:30-37

This passage is one of those episodes that is easy enough to understand but so challenging that rarely have followers of Jesus taken it as seriously as it demands.

Jesus has literally been talking about how he must suffer and die; he’s on the way to the cross to embody his vocation as the servant who suffers and die for the Greater Good.

The disciples don’t understand what Jesus is talking about and they’re too scared to ask.

In fairness, Jesus is often a bit cryptic. I can see how you might not be sure about a lot of what Jesus says. Although here he’s saying it pretty straight out:

“The Son of Man is going to be delivered into the hands of men. They will kill him, and after three days he will rise.” (v31)

You know that one’s going to produce a lightbulb moment down the track.

Meanwhile, Jesus’ own disciples, on the way, start arguing about who among them is greatest!

They’ve still got this big idea dominating their thinking that Jesus is going to come in power, knock off all of God’s assumed opponents and establish a new government under his reign.

They of course begin jockeying for high positions in the cabinet of the new government (who could imagine that?)

They put forward their best case for their own special-ness – front row- seats to Jesus’ healings, or his transfiguration. Anything that explains why they are so important and most deserving of special positions or titles.

Eventually they make their way to Capernaum and Jesus casually asks, “So what were you all arguing about back there?”

All of a sudden the disciples become awkward and then Jesus names it:

“Anyone who wants to be first must be the very last, and the servant of all.”

Jesus’ new government is a serving movement. It’s not a race to the top; it’s a way of climbing down. It’s a way of humility.

Jesus then produces a little child, as you do, and the placing the child in his arms he says to them,

“Whoever welcomes one of these little children in my name welcomes me; and whoever welcomes me does not welcome me but the one who sent me.” (v37)

This serving movement isn’t about having friends in high places; it’s about having friends in low places!

And in Jesus’ time a child, far more than in our own time, was bottom of the rung.

They had no place.

They were considered a non-entity. They were useless.

They couldn’t help you with your career ambitions.

They were terrible back-up in a fight. Horrible dinner guests. They were never good for a loan.

Bottom of the rung.

But Jesus’ movement is a movement of welcome; a movement of embrace.

Jesus wants his people to welcome the nobodies, the folk who have nothing to bring to the table.

In Jesus’ new government you are embraced not for what you have or what you’ve achieved. You are simply embraced as you are. There’s no worthiness requirement.

Are you part of the human race? You’re in. You’re worthy. You’re a full member of Jesus’ New World Order.

Oh but here’s the one condition:

If you want to welcome the divine life into your own experience, if you want to welcome God into your life, it involves offering that same welcome to those on the bottom of the rung.

Where is God? You’ll find God at the bottom of the ladder, which is a way of saying, you’ll find God everywhere – in all people, in all places, at all times.

It’s a movement of humility and service, a welcoming movement, a movement that discovers that as you embrace others without condition that you welcome and receive the very Source of Life, the Ground of our Being.

This Jesus movement is a way of living without ladders, a way that rejects any notion that I am better than you or you are better than me.

It’s a way of meeting each other that recognises we’re all just like that child – we’re all children of God.

0 notes

Text

Field Trip to Sin City

MARK 8:27-38

PENTECOST 19

Jesus went on with his disciples. He is leading them onward. He is taking them on a field trip some forty kilometres beyond their home base in Galilee. And on the way he will ask them the all-important question regarding who he really is. These two activities – the leading onward and the unveiling of Jesus’ identity and vocation are thoroughly interrelated.

We start with where Jesus is taking his students. Caesarea Philippi was a regional centre of the Roman Empire, a city built upon a dramatic cliff face. From the base of this cliff emerged a spring which the ancients regarded as a kind of gate to the underworld – the Gates of Hades.

The site was a well-known centre for the worship of the Canaanite god Baal and later for the Greek fertility god Pan.

Pan, whose appearance was half-man, half-goat, was also the god of forests and deserted places, of shepherds and flocks. He was credited with helping the Greeks in their victory at Marathon by using his special ability to generate ‘pan-ic’ in an opposing army. He was said to be so ugly that his own parents abandoned him.

Various maidens would also reject his regular advances. John Francis Wilson writes,

‘Thus rejected, he turned to the grossest kinds of sexual adventures, forcing himself indiscriminately on maidens, young boys and even animals with amoral abandon. He is commonly depicted as a leering, bestial freak, though often in the company of beautiful forest nymphs.’[1]

One can presumably imagine the kinds of unseemly and exploitative sexual acts demanded of worshippers in order to ensure good harvest and fertility.

As Jesus leads his disciples into Caesarea Philippi, they would have been confronted by elaborate niches carved into the side of the cliff filled by worshipers with idols and statues of gods.

They would have also taken in the nearby temple built by Herod to honour the Roman Emperor Augustus.

This tour also involved venturing into a location known to be a site where invading armies affiliated with Alexander the Great took the region for the Greek Empire.

Jesus takes his followers here – a place described as ‘the most pagan place in all of Palestine’[2] that good Jews avoided because of its connection with idolatry, bestiality and prostitution. This is a trip into sin-city.

He leads them into a place saturated with religious infidelity and shocking immorality.

He guides them into a site both enamoured with empire and haunted by devastating military defeat.

He has taken them to the abode of the dead – a location textured with violence, pain, suffering and need.

Brian McLaren writes,

‘Imagine what it would be like to enter Caesar-ville with Jesus and his team. Today we might imagine a Jewish leader bringing his followers to Auschwitz, a Japanese leader to Hiroshima, a Native American leader to Wounded Knee, or a Palestinian leader to the wall of separation. There, in the shadow of the cliff face with its idols set into their finely carved niches, in the presence of all these terrible associations, Jesus asks his disciples a carefully crafted question: ‘Who do people say the Son of Man is?’’[3]

This Son of Man reference is no small thing. The Son of Man was a loaded political image from the book of Daniel which anticipated a figure who would gloriously defeat God’s enemies and liberate the exiles from their oppression and captivity (see Daniel 7).

Nor are the stakes low when it comes to Peter’s confident claim that Jesus is the Christ – the Messiah. To speak of the Christ is to speak in dangerously political terms of the liberating king who will upend the Caesar’s of the world and restore the proper balance in terms of God’s desired ends.

The thrill of the revelation for Peter, however, is short-lived. Peter would be in good company if he imagined that the next part involved marching into Jerusalem in glory and power to overthrow God’s enemy as part of the overall plan to establish a new Messianic order. But this notion of a suffering Messiah as revealed by Jesus was unimaginably scandalous and shocking.

But of course, this is Jesus’ field trip and he is guiding his followers forward in ways that defy what they can see and comprehend. Jesus knows his followers are setting their minds not on divine things but rather on human things (v33). They don’t understand the divine heart, the divine program.

Intriguingly this whole scene follows on from an episode about a man who is born blind (Mark 8:22-27). In this story Jesus heals this man in stages. At first the man sees in an unclear way and is only able to see clearly after further application from Jesus. Different scholars have suggested that Mark is using one narrative to interpret the other. Peter too, sees partially, but will require further application from Jesus in order to truly understand who he is and what it means to be the Messiah.

Learning to set a mind on divine things takes time. It happens gradually. Vision is transformed slowly by the one who masterfully guides us into new places despite our own resistance and denial.

Thy kindgdom come does not come without shock or surprise. This is a strange, counter-intuitive story that includes leaving behind the normal comforts and security of home as well as those human yearnings for power and domination over others. This is an upside-down kind of kingdom that involves entering into the kinds of places that are like hell on earth – places of despair, violence, and immorality. This is where Jesus confirms God’s liberating presence.

No place is God-forsaken. God is here in the midst of the death and the decay of the world. Here, in this place, God is liberating, healing. Here Jesus draws his followers forward.