#1650

Text

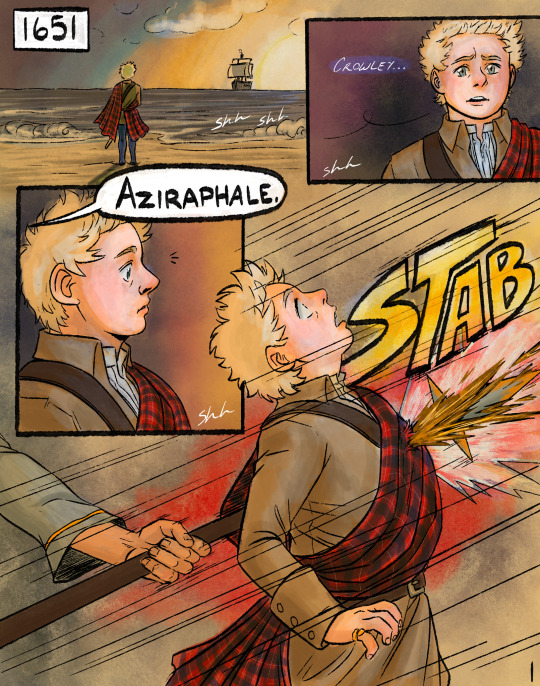

Sins of the Fallen - final angst story

@goodomensafterdark

Based off of the story being made with @kotias called Down the Path of Sin.

#good omens#crowley#aziraphale#michael sheen#neil gaiman#david tennant#good omens fanart#comic#1650#English and Scottish war#good omens after dark angst war#ineffable angst war#angst war#angst comic#down the path of sin

754 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Double Portrait, English School, 1650

773 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think we will see 1650 in Season 3

We've seen 1793...

And 1941...

We can understand why Aziraphale may have done the apology dance in 1793 and 1941, but we have no information about the very first apology dance.

I'm going to assume Aziraphale & Crowley had already taken up residence in England by 1650. We see them in London in 1601 and Aziraphale is living in England in 1793 with plans to open a bookshop, and Crowley referring to England as "home", so it's not a huge stretch to imagine they largely remained in England during this period.

So what happened in England during 1650?

The start of the Third Civil War/Anglo-Scottish war (1650–1652) when England invaded Scotland.

New legislation (The Commonwealth (Adultery) Act) meant the death penalty for incest and adultery.

William III is born.

Anne Greene, a domestic servant, is hanged at Oxford Castle for infanticide, having hidden having a stillbirth. The following day she is found still alive, recovers, and is pardoned as "the Hand of God had saved her".

There could be some really interesting flashbacks for the Ineffable Husbands with these events, or who knows, maybe something else happened in 1650 to prompt the birth of the apology dance?

The shift from 'having the Arrangement but we pretend not to care about each other's wellbeing' to 'you worried/upset me so much that we invented a dance to say sorry' is HUGE. What happened to cause that shift in their relationship?

Let me know your thoughts 😊

Season 3 will likely flashback to parts of Aziracrow's history in order to help us understand their present, as it did in S1 & S2. I have so many questions as to what those flashbacks could be and why it's significant to S3!! I think we'll likely get 2 or 3 flashbacks, and my money is on 1650 and 1941 (Blitz part 3) and given that there's speculation that 1941 had a huge shift in relationship to cause the "you go too fast for me, Crowley" line in the '60s, I would expect a 1650 flashback to be just as intense. How many times have their feelings nearly tumbled out over the centuries? Perhaps one of them was a little too honest, maybe they got too close, maybe they almost or did kiss. God I have so many questions

#good omens#crowley#aziraphale#ineffable husbands#aziracrow#good omens s3#apology dance#good omens meta#1650#1941#1793

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

The way Crowley and Aziraphale talk about the apology dance makes it sound like Crowley's never done it before. If that's the case, it means Crowley came up with it.

[Somehwere in 1650] A: "I'm sorry, Crowley, I truly am."

C: "Hmph. Not good enough."

A: "Please, what do I have to do for you to forgive me?"

C: "...Dance."

A: "What?"

C: "Dancing is the only way to get my forgiveness, Angel. Do you want it or not?"

A: "No! Not like this."

C: "Suit yourself."

A: "Hmph."

[ Spoiler alert: He did the dance. ]

#good omens#crowley#aziraphale#aziracrow#gomens2#crowley x aziraphale#ineffable husbands#1650#apology dance

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

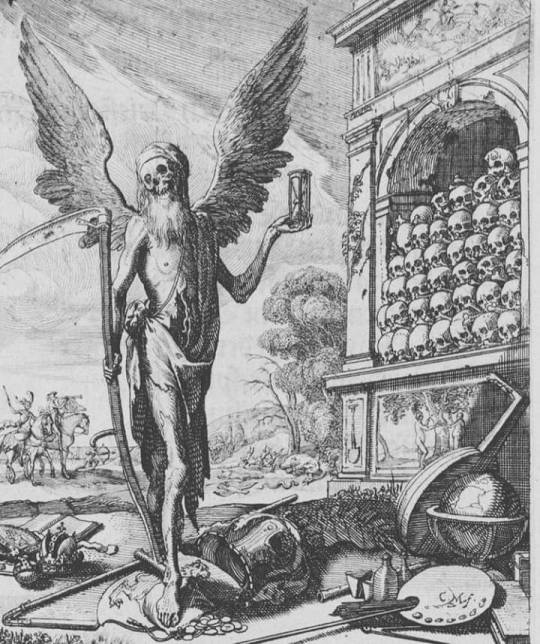

𝔗𝔥𝔢 𝔗𝔯𝔦𝔲𝔪𝔭𝔥 𝔬𝔣 𝔇𝔢𝔞𝔱𝔥. ℜ𝔲𝔡𝔬𝔩𝔣 𝔐𝔢𝔶𝔢𝔯, յճՏօ.

#The Triumph of Death#1650#Rudolf Meyer#dead#death#memento mori#grim reaper#art#illustrations#skulls#skeletons

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Education of the Virgin, (1650)

by Georges de La Tour

oil on canvas

#education of the virgin#georges de la tour#17th century#oil painting#the virgin mary#1650#religion#christianity#light symbolism#:enlightenment#:purity#young mary

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

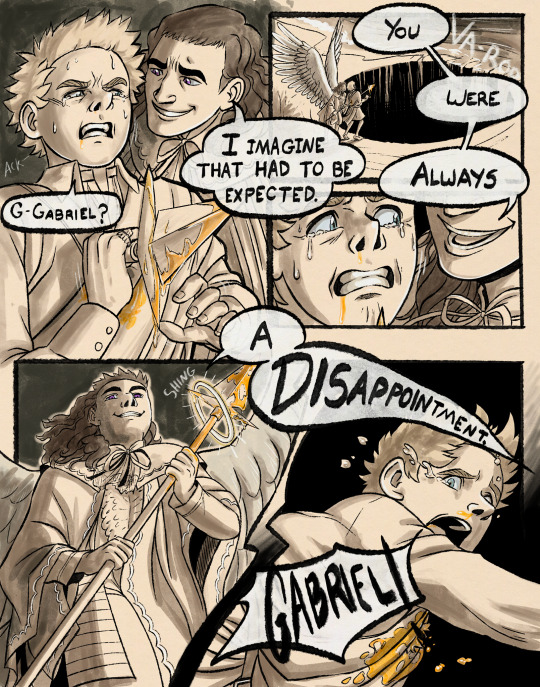

apology dance (1650's version)

for my dear @lillioba. thanks for inspiring me to write this!

6k words of blood, sweat, tears, two mental breakdowns, and tons of historical research. i might be starting the whole "i was wrong dance" series. i've got plans.

we could have lived this dance forever by kayjaye (T)

“You know,” Aziraphale said, hushed tone drawing the demon’s gaze, “in regards to forbidden things, well, there’s always the…underground scene.”

“Underground,” repeated Crowley. “Sounds hellish.”

“No, not like—” Aziraphale glanced around them, aware of his voice resuming normal volume, then fell back into a whisper. “Not like Hell.”

“Aziraphale, are you enlisting me to engage in an illegal theatrical gathering?”

“I was simply asking if you’d care to join me for a show, dear.”

*

Or 1650 presents...Underground theater, the Adultery Act, and an apology dance.

Starring:

- Aziraphale “the Puritans made me do it” Fell

AND

- Anthony J“who said lust was my specialty?” Crowley

read on ao3 or here!

*****

“Are you even listening to me, Crowley?”

Crowley took a swig of his drink—or it could’ve been Aziraphale’s drink for all he knew. It was alcoholic (that was what mattered), tasting distinctly of fruit, but unlike any wine or sherry he’d known Aziraphale to frequent.

He scolded the smile off his face, hiding its stubborn remains behind the rim of the beaker. “By default, certainly not the one doing the talking right now.”

Aziraphale fixed him with a disapproving glare before folding, unfolding, and folding his hands on the table. The pub was at half capacity, but no one paid much attention to the copious number of beverages served in their direction.

Crowley didn’t plan on running into Aziraphale in London. In fact, Crowley tried very hard not to make a habit of planning on the angel at all, but the shreds of hope were tolerable and, more importantly, excusable. He wouldn’t be too let down, and they wouldn’t have to recognize the blatant defiance against their respective sides that came with scheduling meetings. Coincidence was safer.

Poetic, even.

“Those damn Puritans,” mumbled Aziraphale.

Crowley’s eyebrows shot up. “Rather blasphemous,” he mused. “Are they? Damned?”

“You— I mean, theaters, Crowley, really? What’s the point in shutting down entertainment? And during war? Sometimes, it’s as if they want to be as miserable as humanly possible.” Aziraphale searched the table for a moment, spotted the cup in Crowley’s hands, and slumped forward. “It’s not—”

“Fair?”

Aziraphale sighed. “What’s not fair is you polishing off the rest of my drink.”

“It was on me anyway,” Crowley said. “I’ll get you another.”

“No, it’s quite alright.”

Staring at the being in front of him, Crowley pointedly set the cup down. “Seems you’ve got plenty of dramatics to make up for the lack thereof,” he said, not as successful at hiding his amusement this time.

Crowley knew Aziraphale’s grievances were partly rooted in the simple pleasure of having someone to tell them to. As soon as he received news about the Puritan ban on public stage plays, the likelihood of a vexed angel appearing increased tenfold. Not that he kept track of the events he was sure Aziraphale would have words for, but when they did happen to run into each other, he was extremely pleased with the accuracy of his subconscious guesses to the real thing. Wasn’t very demonic of him to take pride in how well he knew an angel, but he could blame the snake in him for wanting to see just how unangelic he could make said angel as he registered his complaints.

“It’s been years!” Aziraphale threw his hands up, finally attracting the eyes of a few patrons across the pub.

“No need to lose your head about it, angel. Would hate to see you end up like ex-King Charlie,” Crowley said as he stretched his arms and collapsed back against the chair. “And it’s been eight years. We’ve been around for—”

“So you’re counting too.”

A snort escaped him as he lounged deeper. “Only because in 1642, you stormed in to fuss about good ol’ Willy’s forced retirement.”

“I did not storm—”

“Oh, it was a great storm. Plenty of lightning.”

“Or fuss—”

“I would’ve argued he stepped down in 1616, you know, when he—”

“Good Lord.”

“Careful,” warned Crowley. “She might actually answer you one day.”

He was afraid he’d taken it too far when Aziraphale didn’t respond with some version of quick-witted chastisement. If Crowley blinked more often, he would’ve missed the once-over from Aziraphale, as though the angel were just now realizing they were in each other’s company. He was about to say something—not of any comprehensive language, maybe an indecipherable noise caught in the back of his throat he could play off as a change in conversation—but Aziraphale wore this loaded expression on his face, and Crowley refrained from interrupting, keen on hearing whatever thought had Aziraphale’s jaw set in such a way.

Then he shook his head. “You are insufferable,” Aziraphale said.

Crowley nudged the empty cup lightly across the table, humming, “You must be fond of suffering, then.”

…And that was his cue, a sign that he’d had too much and needed to call it a day—a night—how long had they been here? The sun dipped lower without him noticing, light collecting in a slim orange line at the bottom of the nearest window. Thank Someone, Crowley had yet to reach the point of drunkenness that loosened his tongue and left him completely oblivious to it. So far, just the former, and he could work with that.

“Not of suffering, no,” came Aziraphale’s rebuttal.

Crowley’s mouth twitched at the carefully placed denial, and he wondered if it had been purposefully crafted to sound more like a confession instead. With that statement, Aziraphale seemed to lay something out on the table, but when Crowley looked down, there was nothing except the angel’s hands, still folded far too prim and proper for someone who’d drunk his fair share tonight.

But like every time Aziraphale waved this olive branch in front of him, doubt swallowed Crowley. He could be mistaken. It could be any other plant-based stem. He was undeniably selfish when it came to this particular temptation, and even so, Crowley could not bring himself to reach out and take it, in diametric contradiction to his nature, concerned with doing the “right” thing (not by Her standards, mind you; by a mostly rule-following bastard, if anyone) and remaining complacent in speaking with words capable of passing undetected.

If not that, angel, what are you fond of?

It was a question that could not receive an answer, he knew that.

Hesitant to end the night but equally at a loss for excuses to prolong it, Crowley sat up and gestured for their cups to be retrieved. By the time the table was cleared and Crowley had slipped back into his jacket, Aziraphale worked up the nerve to say what he’d conceivably been trying to say all evening.

“You know,” Aziraphale said, hushed tone drawing the demon’s gaze, “in regards to forbidden things, well, there’s always the…underground scene.”

“Underground,” repeated Crowley. “Sounds hellish.”

“No, not like—” Aziraphale glanced around them, aware of his voice resuming normal volume, then fell back into a whisper. “Not like Hell.”

Crowley took his time inhaling, well-practiced at feigning impassivity, for the sake of testing whether Aziraphale had it in him to address a request directly. He leaned forward, elbow propped on the table, chin in hand, and cocked his head, fully committed to just as much dramatic flair as his counterpart.

“Aziraphale, are you enlisting me to engage in an illegal theatrical gathering?”

Aziraphale smiled, and his hands finally unclasped. “I was simply asking if you’d care to join me for a show, dear.”

Thank Someone for his glasses; Crowley didn’t want to think about how his eyes lit up at the mere suggestion. His reply was the same as it had been since Rome, even if Crowley tacked on, “Because it’d be a shame to miss an angel partaking in unlawful activity,” in the interest of saving some face.

Following Aziraphale out, Crowley nodded his thanks as he ducked past the angel holding the door for him. They walked in step, the evening quiet blurring into the background.

With an excited, tipsy lilt, though sober enough to avoid stumbling when he walked, Aziraphale recounted how he knew the venue host. A noise of acknowledgement forced itself from the demon’s throat, but he couldn’t recite the name of the English nobleman funding the illicit show or explain how Aziraphale obtained access to such private affairs if prompted. Crowley’s attention waned in favor of watching Aziraphale slip his fingers beneath his shirt collar, tugging the fabric to rub his neck. Crowley swallowed, told himself it was the stitching that was admirable and nothing else.

The outside certainly didn’t look like any theater Crowley had ever attended, granted he didn’t usually note the architecture of the places Aziraphale coerced him into. Unlike the Globe, this one promised a complete roof. Initially mistaken for any regular tavern or pub, a brick arch preceded the pillar-lined entryway suitable for a respectable manor. Aziraphale led them through a maze of hallways, and Crowley blankly surrendered to either requiring Aziraphale’s assistance or a literal miracle if he intended to leave this labyrinth. Finally, they came across a young man standing guard outside a pair of ajar ballroom doors.

If you considered his thin frame and fidgety disposition guard-worthy characteristics, that is.

“Mr. Fell, glad to see you could make it,” he addressed the angel.

“As am I, Walter,” said Aziraphale, cheery as ever.

The man turned to Crowley, suddenly apprehensive. “And you, sir…?”

“Oh, yes,” Aziraphale cut in, leaning forward as if to tell a secret. Crowley half expected to see the angel’s giddy wiggle at anything remotely sneaky. “He’s with me.”

That, though…that was not what he was expecting.

Despite his best efforts, Crowley fought a losing battle in the struggle to maintain a stoically cool expression. Shock? Or satisfying pride? At least his jaw didn’t hit the floor. It was strikingly far from He’s not my friend. We’ve never met before. We don’t know each other.

And it was altogether so easy to misconstrue:

He’s with me. We’re together. How silly to think otherwise.

A pregnant pause before Crowley noticed Aziraphale looking at him, waiting for…ah, yes. He extended a hand blindly in Walter’s direction and forcibly dragged his heavy gaze away from the angel.

Not quick enough to avoid narrowing blue.

“A friend of Mr. Fell’s,” he said matter-of-factly, and perhaps a bit indulgently. “Anonymity is essential at these types of things, is it not?”

Walter smiled and shook his hand. Something about that little human gesture always tickled Crowley when he was on the other end of it. A deal with…well, not the devil, but by association, sure. His returning smile was more amused than pleased to meet, and Aziraphale knew exactly why. If the admonishing eye-roll, accompanied by a soft laugh, pivoting into a muffled cough, and then an attempt to clear his throat, was any indication.

While Aziraphale exchanged pleasantries with Walter, Crowley took the opportunity to peek into what he assumed was the house, surprised to find a large audience already sitting. A candle-lit chandelier hung from the ceiling, casting overhead light along with the sconces on the walls, punctuating each row of seats. The stage itself appeared brighter, most likely the work of reflectors.

Crowley was impressed, not only with the set design but also with the number of people willing to face fines for attending clandestine performances.

Hell probably loved all the rule-breaking.

Likewise, Heaven probably loved the Puritan devotion to having no fun.

The ghost of Aziraphale’s hand appeared, hovering just above the small of Crowley’s back, not touching but burning all the same. “Ready?” Aziraphale whispered behind him.

Crowley bit down, his focus solely on resisting the urge to lean back and close the distance, forgo dancing flames and feel the fire firsthand. Such an effort required utmost concentration, so if the noise Crowley made sounded strained, it was purely because he’d forgotten to breathe.

As they settled in their seats, the ambient murmur of conversation gradually tapered off, drowned out by the resonant thud of the closing doors echoing through the theater. Crowley folded his glasses into his pocket, now concealed in dim darkness where attention would undoubtedly be centered on the stage. An anticipatory silence enveloped the room, broken as an actor dashed into view, waving a letter in his hands and declaring word from Don Pedro.

One of the funny ones, then. Crowley was just relieved it wasn’t a tragedy.

The play progressed smoothly into its second act with practiced precision, succeeding yet again at impressing the demon. Periodically, he observed Aziraphale’s reactions to the parts that elicited laughter from the crowd, and he was met with the same angel delight present during the premiere some 40 years ago.

That is, until the abrupt scene change. He’d heard of improv before, but introducing a completely new character seemed like a stretch.

“Oi, Thomas!”

A man emerged on stage.

Crowley leaned forward for a better look at the newcomer striding across the floor, and next to him, Aziraphale straightened as well.

“Is there a Thomas in this one?” Crowley whispered, glancing at Aziraphale, but the confusion was obvious in creased white-blond eyebrows, too. He could’ve sworn this was Much Ado About Nothing. Like the actor evidently named Thomas, Aziraphale shook his head in puzzled bewilderment.

Benedick-now-Thomas took a step back, managing a shaky, “Henry?” before the advancing man reached his target and responded with a rough shove against the actor’s shoulders.

“You knave! You slept with Catherine.”

A murmur rippled through the audience.

“I don’t remember this part,” Aziraphale said.

Crowley spared another glimpse at the angel focused on the unfolding scene, an uncertain crowd waiting for things to make sense. It was a familiar feeling—trouble brewing, boiling under the surface; he was used to being the cause of it, however. Crowley crossed his arms and relaxed back into his seat.

They came for a show. A show it would be.

“Catherine?” Thomas said. “Your wife? By God, Henry, I didn’t—”

“You may be on a stage, but don’t act daft,” said Henry. Balled fists were enough of a threat to send Thomas knocking into props. “Just last night, I saw you and that bedswerver enter the Star Inn together.”

The other actors stood awkwardly, some peeking offstage for further instruction but ultimately conflicted on how to react to the sudden intrusion. Crowley saw several audience members whispering to each other.

“I didn’t sleep with her,” Thomas insisted.

Henry glared at the man with a curled lip so ugly, Crowley could make out the sneer from where he was sitting. “I ought to have this place shut down,” said Henry, “but I’m sure you’re aware of the price of adultery these days, fitting as it is.”

Commotion buzzed through the audience again.

“You’d have them execute your own wife?!”

“She ceased to be that the moment you had her.”

“I haven’t, Henry, I wouldn’t—”

Crowley turned toward Aziraphale, ready to make a comment about drama writing itself, a callback to the world being a stage or the world being an oyster (oysters were a touchy subject for Crowley…as in they kindled a stifling desire for touch), but the angel had gone stock-still. No more craning his neck for a better view, just frozen silence pulling the ends of his mouth down.

“Angel?”

Aziraphale stared straight ahead, but Crowley suspected he wasn’t actually looking at anything anymore, rather thinking with his eyes open. “It was me,” Aziraphale said, barely audible.

“What was you?”

“I was the one who met with her.”

Crowley blanched. Snakes are cold-blooded creatures, but the ice flowing through his veins was an entirely new sensation.

“You” —think of a different word, think of a better word, there are so many other words— “fucked her?”

It was almost comical, the seconds between the time it took Aziraphale to register Crowley’s question. His distracted stupor morphed into panic as he zeroed in on the demon, and Crowley received a pair of wide eyes mirroring his own. He witnessed the angel’s frantic grapple for words that hit a blockade and went down the wrong pipe. Even in the low lighting, the rosy hue of flushed cheeks and burnt ears stood out as Aziraphale choked on his reply.

Meanwhile, Crowley was busy trying to wrap his head around the image of Aziraphale engaging in…ngk, let’s not go there.

To Aziraphale’s mouth, currently agape in alarm, but reminiscent of what else those lips might part for. To Aziraphale’s fingers slithering farther than just his shirt collar. To Aziraphale’s hands and their branding heat. To Aziraphale’s insatiable hunger for food that must surely translate to other mortal appetites.

And even worse, the softer fantasies. The love wafting off in waves. The “my dear” pressed into bare skin. The assurance of never hitting the ground again. Arms so safe they could make a demon forget what falling feels like.

Had he ever really stopped? Was he still plummeting through layers of ozone and dirt? Did the stomach-sinking, wings-burning, halo-shattering ache ever disappear, or was he merely used to the eternal descent?

Used to being dropped.

And there it was at its core—yearning to be held. Crowley didn’t know how he knew, but unforgivable as he was, damned and disowned, he knew.

Aziraphale would hold and hold and hold.

He was probably that kind of lover; he was an angel, after all.

An angel.

Holy fuck. He was an angel who made an effort—

“No!” hissed Aziraphale.

Most of the audience had resorted to shifting in their seats, peering around the room and filling the space with growing chatter after Henry marched off stage and Thomas darted in the other direction. The remaining actors floundered until someone announced a brief interlude.

Aziraphale floundered too before grabbing Crowley’s wrist. “Come on,” he said, and they filed out of the theater with a few other deserters.

Crowley kept his thoughts to himself as Aziraphale hauled them outside where the temperature had noticeably dipped. The angel halted, surveyed the area, too paranoid to be inconspicuous, then walked farther down the street to turn the corner with Crowley in tow.

Now alone, the atmosphere felt as surreptitious as public stage plays.

“I didn’t—” Aziraphale said, finally releasing his grip on Crowley.

The demon waited.

Aziraphale crumbled into a pout. “...with her. I didn’t—We didn’t do that.”

“So you didn’t fuck her?”

“Really, there’s no need to be crass.” Aziraphale took a breath. “Mrs. Beckford and I met at the Star Inn to talk about the play. Like I told you before” —when Crowley was definitely paying attention; the pinnacle of an avid listener at all times, him, obviously— “her husband affords the theater. He makes the whole thing possible.” Suddenly, the brick wall behind Crowley became curiously fascinating as Aziraphale averted his eyes and said, “I wanted—well, you liked this one back in 1612, so I just asked if…”

Without the weight of his glasses, Crowley couldn’t discern how successful he was at disguising the toss-and-turn in his head. Shock expired, spoiling into bitterness, soon replaced by awe. He couldn’t decide which was more embarrassing: that he only enjoyed Much Ado About Nothing because Aziraphale loved it so much, or that Aziraphale took it upon himself to request a show he thought Crowley would appreciate.

“So I suppose it’s my fault for the misunderstanding?” Crowley quipped, prepared to brush past the admission.

“Well, isn’t it?”

Crowley frowned. “I was joking.”

“It won’t be funny when Catherine gets killed for something she didn’t do,” Aziraphale said. “And Thomas, wrongly accused.”

“So what? You’ll tell them it was you instead?” Aziraphale seemed to actually consider it, which made Crowley groan, “Mr. Beckford—Henry, or whatever—sounded pretty convinced of what went down.” Satan knows they never believe the women. Witches, all of them. “Angel, you’d be ki—discorporated. You know they execute the woman AND her lover, right?”

Aziraphale started to place his hands on his hips, then thought better of it and crossed them over his chest. “Yes, well, you would know, wouldn’t you?”

Crowley’s frustration narrowed into a glare. “What’s that mean?”

“You’re the reason for this awful adultery law, aren’t you?” said Aziraphale, assertive even in his flustered state.

“Sorry?”

“Did you want me to forgive you?”

Crowley almost flinched. “I meant, what are you on about? I didn’t start the law,” he said. “Adultery is one of your side’s Big Ten.”

“Not killing people is also a commandment,” Aziraphale stated.

Crowley bristled at the angel’s disdainful tone. “She’s always been rather hypocritical when it comes to violence. Bit of an oxymoron, holy war,” he said hotly.

“Either Hell assigned the Adultery Act to you,” Aziraphale said, steering back to the original point, “or you just…”

“I just what?”

“Or you’re just the Serpent of Eden!”

The fight knocked clean out of him.

Aziraphale shrugged in exasperated defeat, and all Crowley could do was stare. “Tempted Eve and doomed them both,” he continued. “A test of faith and irrevocable punishment sounds right up your alley.”

Crowley refused to call it betrayal, so he chalked it up to the consequences of mixing low expectations with hope. Aziraphale felt guilty about Catherine and Thomas, he knew that, but Crowley had been labeled guilty for a long time.

“Test of faith and irrevocable punishment,” Crowley echoed. “I think you’ve got it wrong, Aziraphale. You know who that does sound like?”

He looked up at the sky.

Aziraphale didn’t respond.

“And I am the serpent,” said Crowley, forcefully venomous. Then softer, “You were there, remember?”

Neither of them spoke, but the demon offered a single lingering opening that went untouched. He turned and walked away.

The angel let him.

———————

Crowley woke up hungover, something he didn’t usually allow. The light pouring through the inn window was far too bright, but no matter how hard he tried to miracle the shutters closed, he couldn’t escape the splitting headache of being awake. He reluctantly sobered up, exerting most of his energy toward the endeavor and rolling his eyes at the realization he’d no doubt get plastered again in a few hours. It was already late afternoon when he coaxed himself out of bed.

At least he’d been too drunk to dream. He did not need to see the angel anytime soon.

Serpent of Eden.

Her book loved to paint him as some vile creature instigating the fall. Every translation since man managed to hold a pen, the depiction of deceit.

True, he did tempt Eve. He liked Eve, though. She never quite forgave him outright for the apple, but it couldn’t be helped. He’d stuck around after the garden, known her as they lived out their separate retributions. In his opinion, he reckoned knowledge made her all the more likable. Except for that infuriating habit of pointing out when a certain guardian of the general eastern direction was looking. She’d teased him until his face was redder than forbidden fruit, and then she’d teased him about that, too.

Crowley’s aforementioned statement turned out to be false; he hadn’t expected to see Aziraphale, but when he set foot in the pub that evening to find the angel waiting for him, it was definitely something close to need. Godawful hope ruining his stony front yet again.

He should’ve picked a different pub. He should’ve started drinking earlier. He was too sober for another argument. And damn it all, he should’ve left London last night, but he couldn’t. Not when the angel would’ve turned himself in, the absolute martyr. Could give Her son a run for His money.

Of course, Crowley couldn’t step in for Him, but he could do something about the angel. He’d be damned (again) before he let Aziraphale ridiculously, needlessly, discorporate himself. Even if he was mad.

Once Crowley begrudgingly made his way to their table, and let it be known the idea of hightailing it out of the establishment did cross his mind, Aziraphale wasted no time asking the question awaiting its exhaled release.

“What did you do?”

Crowley practically fell into his seat. “Can I get drunk first?”

Aziraphale shook his head incredulously but didn’t stop Crowley from ordering a dram of whiskey. “I went by the Beckford estate this morning to speak to Catherine—to confess to her husband,” Aziraphale said, “and she told me the strangest thing.”

Crowley threw back his drink and willed the alcohol to kick in sooner.

“She said the accusation of adultery wouldn’t hold up in court because, miraculously, no record of her marriage to a Mr. Henry Beckford existed.”

“Well, you know the courts,” said Crowley. “Dreadfully hesitant to rule irrevocable punishment without proof. Funny isn’t it, how most marriages in England are unregistered?”

“Crowley.”

He aimed for indifference— “I do believe I fixed your problem” —and landed somewhere between smug and stressed.

Aziraphale’s expression softened. Crowley debated a refill.

“Don’t,” the demon said. “I performed a slew of demonic miracles last night. Can’t be held responsible for what I may or may not have miracled. Did you know they were out of whiskey here?” He waved his cup in distracted demonstration. “Restocked the whole town.”

Like the prior night, the pub was relatively vacant. An absence of clinking silverware and subdued tavern talk saddled the air with uncomfortable tension.

For Crowley, anyhow. Aziraphale seemed content to tough it out.

“Ok,” Crowley conceded impatiently, “so I made a couple documents disappear. Big deal. Call it wily, angel. Were you or were you not on your way to untimely discorporation?”

Aziraphale looked relieved and somehow even more guilty. “You didn’t have to do that,” he said. “Thank you.”

Politeness was second nature for an angel, but they both grasped the absurdity of it directed at a demon.

“I don’t have to do anything,” Crowley corrected. “‘M a demon. Can do whatever I want.” He pushed his glasses higher up on the bridge of his nose for good measure. “You think I haven’t been twisting the fine print of that law since they wrote it? I was the one who added the bloody clause about not including women whose husbands were absent for three or more years. They wanted to start chopping off heads left and right.”

As if Aziraphale encountered a new version of Crowley every time he opened his mouth, the angel looked on the cusp of several routes to take. Crowley almost wanted the angel to pick up where he left last night, call him a snake, and remind him how foolish this entire arrangement had been. Not the Arrangement, but the messy web spun full of unspoken-rules and uncrossable-lines. Though he’d been privy to their creation and placement, Crowley was prone to forgetting the location of these silk strand glue droplets and stepping on them like landmines, unraveling the whole thing. He could never seem to find his footing without setting off explosive repercussions.

Crowley wasn’t sure if he was a spider caught in a web of its own making, or a fly in Aziraphale’s.

“I’m sorry, Crowley.”

Perhaps it was the famine of the word that made Crowley go slack, but the apology dropped into the pit of his stomach and rubbed in the starvation he’d so skillfully ignored.

“I shouldn’t have assumed you were behind the act,” Aziraphale said. “I actually, uh, checked in with Gabriel and the others.” Crowley raised an eyebrow, and Aziraphale cast his gaze on the ground. “Turns out they sanctioned it. For the noble cause of Puritanism.”

“I take it they were also fans of putting a pause on ‘lascivious mirth and levity’?”

Aziraphale pulled a face. “They see value in banning the plays as well, yes.”

“Yeah, well, for what it’s worth,” Crowley said, words slightly bitter with a burned edge, probably from the whiskey, “Hell enjoys the blatant sexism of the Adultery Act, too.” He tilted his cup and watched the last few drops pool to one side of the bottom. “Heaven. Hell. Two sides of the same coin.”

If Aziraphale disagreed, he held his tongue, opting for a pinched expression of pain or worry that Crowley figured was due to something more. “But I should’ve— Hell is one thing,” Aziraphale huffed. “What I’m trying to say is I know you.”

You do not know me, a faint memory of Crowley’s objected. Something doused in suspicion, mixed with a hint of a challenge, and drowned out by bleating goats. Something he would’ve said back then, and something he couldn’t bring himself to say now.

“Do you?” he asked. Because it wasn’t total denial, and temptation did happen to be his job, and maybe he just wanted to feel less unknown.

Aziraphale looked at him, saw straight through the act, and with such conviction, spoke more words than what he actually said.

“Yes.”

Crowley stared back, as though Aziraphale might rescind his statement, but the angel’s determination never faltered. Upstairs and Downstairs might read it as Yes, I know you well enough to thwart any wiles you may throw my way. But Crowley, well-versed in silent tongues, saw it for what it was:

Yes, I know you’re doing this on purpose. Asking questions to see if they’ll get you in trouble once more because everything is a test of faith with us, isn’t it? I know you miss the unicorns. I know you have a tendency to criticize living things—those poor, terrified plants—but you like to see them grow anyhow. I know you in spite of whatever lead balloon comes crashing down, and yes, I know you well enough to also know the Serpent of Eden was just as shy as he was sly. Because I was there.

If the public ever found out that Crowley could never stay mad at Aziraphale for long, it would surely ruin his demonic reputation. He hummed in thoughtful acceptance.

“I’m sorry,” Aziraphale said again.

Though he wasn’t mad, he could still make the angel squirm. “Did you want me to forgive you?” Crowley mimicked in his best posh accent.

Aziraphale cringed. “I suppose that would be nice, yes,” he said, equal parts hopeful and sheepish.

“Demon. Not nice,” Crowley growled, this time setting his glass down to point a finger between the two of them. “And forgiveness from me would just cancel out or something.”

Aziraphale considered this, shoulders sagging and hands unsure of what else to do other than grab onto each other. He tried to keep his expression neutral, but the disappointment bled right through.

A merciful demon? No, Crowley just couldn’t stand to see Aziraphale sad for very long either.

“I’ll tell you what you could do, though,” he said.

Aziraphale perked up.

“Dance.”

A furrowed brow lifted into pink surprise as the angel tilted his head. “Uh, with you?”

Yes. “No,” Crowley said a bit too fast. “Give us a little jig, y’know, a song and dance. You like the theater. They say emotion is best expressed through art.” He attempted to reason his way out of this one. “Show me how sorry you are, angel.”

“I…don’t dance.”

“And I’m not nice,” Crowley said, but he was smiling now. “Unorthodox apology for unorthodox forgiveness sounds like a fair trade to me.”

A beat passed between them, and Crowley almost thought Aziraphale wouldn’t do it. He wasn’t exactly serious about it either; it was just the first thing that popped into his head and out of his mouth.

But then Aziraphale stopped chewing on his lip, made a decisive noise, and stood up from the table. Crowley’s speechlessness was remedied only by the screaming voice in his head that this might be the best accidental idea he’d ever had.

Aziraphale took a small step backward, looking over his shoulder once before realizing he’d rather not make eye contact with anyone, which was an unheard prayer because Crowley slid his glasses down far enough to peer over them, settling yellow eyes right on him.

“Go on,” said Crowley. “Really sell it.”

Aziraphale shook his head at the demon, but took a deep breath to fuel his singsong tone.

One hand on his hip, the other palm up, “You were right,” both arms outstretched, “you were right,” a graceless spin, “I was wrong,” and a clumsy curtsy to top it all off, “you were right.”

Aziraphale lifted his chin but stayed stiff in his pose, waiting for approval.

A dancing angel, Crowley figured, would be something along the lines of embarrassing. Like watching a child try to take its first steps. The never-before-seen aspect completely captivated him, and it suddenly hit him that this was for his eyes only. It was embarrassingly silly. Turns out, silly really does it for him.

Or maybe that was just Aziraphale.

“Right, then.” Crowley nodded with a coughed-out laugh. “That’ll do it.”

“Oh, good,” Aziraphale exhaled in exhausted relief and straightened finally. He plopped back down into his seat with a forest fire ravaging his cheeks. “Thank you.”

“The pleasure was all mine, I assure you,” Crowley practically purred.

Aziraphale’s frown failed to be anything less than fond, and then switched to contemplative. The blush didn’t seem to be dying down anytime soon. Not that Crowley was complaining, but he grew more concerned with each shade of red that he’d have to find a water bucket to cool the angel off.

Aziraphale cleared his throat. “It’s certainly not an excuse for blaming you, and obviously I know you didn’t do it,” Aziraphale said, “but truthfully, I just figured you would’ve had something to do with a law dealing with lust.”

Crowley squinted at him from behind his glasses.

Aziraphale fretted in the silence, then tried to clarify, “Adultery is often associated with lust, as I understand it.”

“Aziraphale,” began Crowley, and he couldn’t believe he was about to say this, “I’m not an incubus.”

“Of course, I know that,” Aziraphale said hurriedly. “I just thought because you’re so…you know. I thought—” He gestured to all of Crowley, wildly searching for the correct term. “You and lust,” he said, like it was clear as day.

The pieces weren’t clicking. Crowley let out a punched, “Wot?”

“Nevermind it,” Aziraphale said, waving off the conversation. “It’s over now. I appreciate what you did, despite what I said that night.”

Crowley grunted, positive his face was just as flushed now. “Would’ve been unfortunate if that Thomas lad got dragged into something he wasn’t involved in, let alone sentenced for it.”

“Ah, yes, well,” and Aziraphale spoke the next part very slowly, “they are in love.”

“Who?”

“Thomas and Catherine.”

“But I thought—”

“Yes, I know you organized the document mishap,” Aziraphale said, raising his eyebrows in a little nod that usually meant Crowley was supposed to listen carefully, “but a nonexistent marriage might as well be the case. Catherine was so unhappy—had been for a long while. Frankly, I was surprised her husband made such an outburst, especially considering the rumors of his own infidelity.” He looked as though he wanted to say more about Mr. Beckford’s trysts, but did not. “During my conversation with Catherine, we discussed the theater, but she also confessed she’d fallen in love with Sir Thomas. Nothing like an arrangement— I mean, her arranged marriage. Something real, Crowley. But she was afraid of what might happen. The Adultery Act was the reason they never… Thomas isn’t a liar. Catherine wouldn’t lay with him because she couldn’t bring herself to condemn them both, I suppose.” Aziraphale paused, suddenly remembering himself, then added, “At least, that’s what she told me.”

Crowley was silent. The risk of spouting idiocy, loaded like bullets on his tongue, waiting for the slightest tremble to set off his hair-trigger self-control—that was too much, even though he was fairly certain the alcohol hadn’t taken effect yet.

Did she want to though?

I think I’ve heard this story before.

Oh, now you’re not even trying, angel.

You know I’m already condemned.

So he clamped his mouth shut because the recoil would’ve sent him reeling, and it could only ever end in someone bleeding out.

“Well,” Crowley said, “drink, then?” Before Aziraphale could even nod in agreement, the demon was already in the process of flagging down the tavern keeper. “What’d you have last night, angel?”

Aziraphale broke into a grin. “You drank mine, and you didn’t even know what it was?”

“Obviously wasn’t whiskey,” Crowley grumbled, but he was immensely glad to hear the angel laugh.

Don’t stare too long. There’ll be stars in his eyes when he opens them.

But Crowley was not a saint by any means; he couldn’t deny himself the view. And there were. Stars. A twinkle in shining blue that sent a thrill up Crowley’s spine. A relic of a past life and what it meant to create entire galaxies all wrapped up in a celestial being’s eyes.

“Cider, dear,” Aziraphale said. “I thought you would’ve known.”

Crowley could’ve sworn he was going blind as the angel had the audacity to fucking beam.

“There’s just something so remarkably alluring about apples, wouldn’t you say?”

*****

i now know too much about the Adultery Act of 1650, theater terminology, the Little Ice Age and alcoholic cider, 17th century lighting and candle reflectors, and the Anglo-Scottish wars.

i’m not kidding, i watched an entire 30-minute YouTube video recapping the English Civil Wars.

well, there’s my take on 1650, hope i did it justice, and thanks for reading!

#good omens#good omens fic#writing#my fic#ineffable husbands#apology dance#i was wrong dance#1650#kayjaye writes

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

▪︎ Charles I.

Artist: After an engraving of by Wenceslaus Hollar (Bohemian, Prague 1607–1677 London)

Date: 1650-1670

Culture: British

Medium: Silk and metal thread on silk

#art#portrait#miniature#Miniature portrait#miniature painting#charles I#17th century art#17th century#Bohemian#1670#1650

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meekness

Eustache Le Sueur

Oil on Panel, 1650

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Still life with fruits, c.1650 by anonimous

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eustache Le Sueur - Meekness (1650)

Eustache Le Sueur - Une Béatitude : La Justice - 1650

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bronze Vase with Roses, Pedro de Camprobin, 1640-60

#bronze vase with roses#Pedro de camprobin#camprobin#1640#1650#1660#1640s#1650s#1660s#1600s#17th century#still life#painting#flowers#roses#art

358 notes

·

View notes

Text

Workshop: Letter, oder: Objekte, die lassen

Wenn, wie Rudolf Jhering 1865 in seiner Arbeit über den Geist des römischen Rechts auf den verschiedenen Stufen seiner Entwicklung nahe legt, der Letter (kleinster Teil des Alphabets) der einfache Bestandteil des Rechts und damit einer der Bausteine des Rechts ist, dann muss der Letter nicht das sein, was dem Recht eigen ist. Dann muss den Letter nicht auszeichnen, was nur im und am Recht vorkommt, ohne Recht oder außerhalb des Rechts aber nicht vorkommt. Es kann dann nämlich sein, und davon wollen wir ausgehen, dass der Letter dann nicht nur ein minoren Objekt ist, dem juristisch oder juristisch alles weitere aufsitzt, sondern dass der Letter dann auch ein Grenzobjekt ist, also ein solches Objekt, an dem und durch das ein juristisches Wissen teilbar wird und geteilt werden muss. Der Letter ist dann ein Objekt, an dem das juristische Wissen zwar an seine Grenzen kommt, aber dennoch nicht aufhört, Effekt zu sein und Effekte zu haben. Referenz, Resonanz, Mimesis und Rekursion werden ab da entweder exzessiv, sie leihern dann eventuell aus oder sie biegen sich auf eine Weise, die die jeweils mitlaufende Assoziation nicht mehr 'artig', nicht mehr 'züchtig', nicht mehr homogen, nicht mehr generisch angemessen erscheinen lässt, wie das der Fall ist, an dem erkennbar wird, dass der Mensch auch von niederem Wesen als dem Menschen abstammt, dass in seinem Bestand nicht nur organisches Material vorkommt und dass noch in Wort und Begriff Sprachlosigkeit und Übertönung stecken. Letter ist dann das, an dem ein Zeichen in das übergeht, dem es aufgezeichnet ist, an dem ein Schreibens ins Bild übergeht, am dem die Sichtung ins Tasten übergreift und der Körper zur Fläche wird, an dem das Sprechen verstummt oder 'verkracht' und alle diese Übergänge auch in der gegenläufigen Richtung funktionieren.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

source: @lcrdbyron

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Juan de Pareja (1650)

Diego Velázquez, Retrato de Juan de Pareja (1650)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

ℜ𝔲𝔡𝔬𝔩𝔣 𝔞𝔫𝔡 ℭ𝔬𝔫𝔯𝔞𝔡 𝔐𝔢𝔶𝔢𝔯, յճՏօ.

#Rudolf and Conrad Meyer#1650#art#painting#artwork#illustrations#grim reaper#reaper#creatures#aggressive#illustration

10 notes

·

View notes