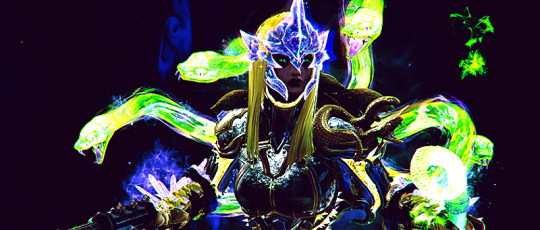

#Camélia Nightingale

Photo

Bursting from the green halo

the hex is roaming like

a numbing force for a sullen core.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Introducing a storyless OC: Janice

Meet one of my dearest and most secret children: Janice or as her friends call her: Jan (pronounced Jen)

Since I love her very much and have carried her around in my brain for some time, I have now decided to share her with you all! Please treat her kindly, she is more fragile than she wants you to think!

basic information

full name: Janice Fiordiligi Ardizzone

orientation: cis girl (she/her), biromantic demisexual

age: currently 22

birthday: December 7 1998

nationality: british-swiss-italian

occupation: aspiring prima ballerina, instagram cosplayer

height: c. 5’2 (160 cm)

weight: 41 kg

eyes: dark blue

hair: black, curly, chest length

rough biography

was shoved off to a dancing school at age 3 bc her parents were always busy. Little did they know what would come of it

went to school in Naples until she was 7, afterwards moved to Paris w her parents

Stayed there until she was 13, studied at the Paris Opera Ballet School as one of the exceptional talents of the school (danced the part of young Clara in The Nutcracker when she was 12)

then moved to Moscow, was accepted into the Moscow State Academy of Choreography (the Bolshoi Ballet Academy)

taught by famous ex-prima ballerina Sonia Lyutenkova who also became her tutor and sort of new mother since her parents were constantly travelling around the world bc of her father’s job (whatever that may be)

her first bigger role was one of the little swans in Swan Lake when she was 17 and had to step in for an older ballerina who got sick

was noticed by the company and given bigger roles, her breakthrough being the part of Marguerite Gautier in a junior production of La Dame Aux Camélias

a ballerina at the Bolshoi since June 2019

personal information

the snarkiest person in the room. Literally and always.

very dark humour, sometimes even a bit inappropriate

doesn’t get along with her mum, they are both girlbosses™

loves her father even though they don’t see each other much

always has to take care of her cousin Amadeo who is two years older and a complete disaster (alcohol, drugs and so on). Granted, his mother died when he was 10 (also from alcohol poisoning) and he never knew his father, lived with his and Janice’s grandparents in Sicily now

does cosplays on Instagram, mostly historical personalities and makes all the costumes herself

super invested in her career, even if it doesn’t look like it

very good at hiding her feelings, seems almost indifferent at times

describes her style as “gay cowboy witch”

strong marxist and atheist tendencies (got that from Sonia Lyutenkova who is a committed communist)

sometimes says very (unintentionally) unsettling things like for example loves to talk about mummies and corpses at the dinner table

is the bro friend

really and she means really really doesn’t want to be in a relationship bc she is afraid of losing her independence

except sometimes she wants to be in a relationship. Or actually all the time secretly. the only thing is that she hates people except some and she finds them stupid and immature

sometimes she just really wants to marry some old classy rich dude who is more like her guardian and who’s just sweet and funny, then dies and leaves her everything

and sometimes she wants to run away with a stylish assassin or thief and be a super cool moll

oh also she would have had a little sister but she was born dead and that’s something that has traumatised her till this day

so all in all yes. She has issues™️

sorry for this very long intro, I just love her very much and now you know about her :)))))))))))

taglist under the cut (ask to be +/-)

general taglist: @wherewindysurgeswend @nightingale-keats @bookphobe @write-gallagher @sadsentinel @aphaimaniis @tragediesoftory @ortolon @euphoniouspandemonium

#not some shameless self insert right here not at all noooo#c: janice#oc intro#oc introduction#my writing#writing#writeblr#writblr#amwriting

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

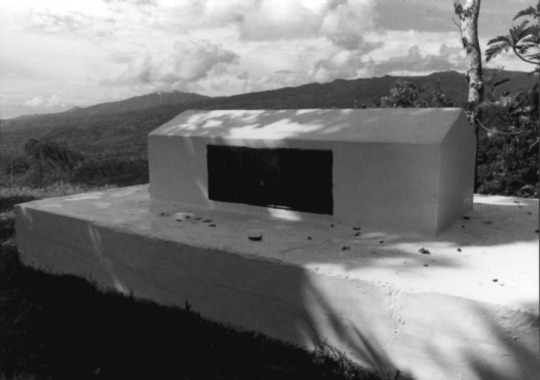

David M. Morens, At the Deathbed of Consumptive Art, 8 Emerg Infect Dis 1353 (2002)

Robert Louis Stevenson's sarcophagus, on top of Mount Vaea, Upolu, Western Samoa. Photo courtesy of David Morens.

Under the wide and starry sky,

Dig the grave and let me lie.

-- R. L. Stevenson, “Requiem”

For more than a century, readers have pondered the strange beginning to one of the most haunting poems in the English language, “Requiem.” Who has not wondered how a poet can seem to welcome his own death? Scotsman Robert Louis Stevenson died of a disease so poorly understood in his day that over a few decades its preferred name changed three times, from "phthisis" to "consumption" to "tuberculosis.” A century later, we have reliable scientific facts on this "old" poet-killing disease—we know for one that Mycobacterium tuberculosis now infects 1.9 billion people, nearly a third of the world’s population (nearly 2 million deaths each year). But human suffering is still difficult to quantify.

Two million deaths each year. How can we grasp such statistics of misery? Reduced to numbers stacked up in columns and cut up in pie charts, tuberculosis patients don’t seem like us. They live in faraway places, come from obscure cultures, speak incomprehensible languages, have disreputable comorbid disease, or exhibit antisocial behavior. They are “the other.” Maybe they do not even exist.

To grasp the human suffering perpetrated by tuberculosis, we may need to recall the past when, incurable and incomprehensible, the disease had to be deciphered by metaphors—metaphors that changed as societal views of the disease changed over time. We may need to recall the lives of dying artists and the work they created and let art paint their faces, sculpt their shapes and contours, and compose leitmotivs. Perhaps such past images will help fix the gazes of today’s victims, whose faces we do not seem to be able to see.

The arts (the novel, the play, the poem, the musical composition, the operatic production) have always helped us understand, given us perspective, invoked compassion, and argued a purpose and meaning for life. We listened to the molto adagio of Barber’s string quartet (opus 11), and came together at President Roosevelt’s death. We read the poems of Walt Whitman and taught our children about the soldier's sacrifice. We studied the works of Petrarcha and Guillaume de Machaut and revisited the terror of Black Death, 700 years ago. Now, we must turn to art again to grasp human suffering because scientific knowledge of the disease seems to have displaced our interest in the patient.

Tuberculosis and the Arts

Poetry

In his modest room, a 25-year-old "lapsed" medical student in 1820s Great Britain wakes from a sudden fevered sweat and finds a single drop of blood on the sheet. He has known many patients who spit such bright blood. “It’s arterial blood…that blood is my death warrant, I must die,” he confides to a friend. One of England’s greatest poets, the medical student John Keats, never wrote specifically about phthisis. But his life and his works became a metaphor for generations of patients, a metaphor that helped transform the physical disease phthisis” into its spiritual offspring, consumption.

Keats’ life was defined by tuberculosis. At 14, he nursed his mother as she died of phthisis. A few years later he watched his brother die of phthisis, and by age 23, he had symptoms of this “hereditary ailment” himself. Yet, as the best remedies (bleeding, diet, red wine, opium) failed, as his work was savaged by critics and his love was languishing (he could not marry because of the disease), Keats feverishly wrote his greatest poems: Ode to a Nightingale, Ode on a Grecian Urn, Ode on Melancholy.

He died only months after he first spit blood. Autopsy found his lungs completely destroyed. He was 26. To be dead himself within the year, Percy Bysshe Shelley, another young poet with phthisis, compared Keats to “a pale flower by some sad maiden cherished,/And fed with true-love tears, instead of dew/The bloom, whose petals nipped before they blew/Died on the promise of the fruit, is waste;/The broken lily lies—the storm is overpast.”

Shelley’s tribute expressed what would become the central metaphor of consumption in the 19th century, the idea that the phthisic body is consumed from within by its passions, “the bloom…Died on the promise of the fruit.” Shelley also likened Keats to an eagle that “outsoared the shadow of our night,” and “could scale Heaven, and could nourish in the sun’s domain.” These romantic notions contrasted sharply with the actual demise of tuberculosis patients, poets or not. As death neared, Keats himself contradicted his friend. In “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles” (published posthumously), Keats wrote, “My spirit is too weak—mortality/Weighs heavily upon me like unwilling sleep,/And each imagin’d pinnacle and steep/Of godlike hardship, tells me I must die/Like a sick Eagle looking at the sky.”

In succeeding decades, Keats’ illness came to exemplify spes phthisica, a condition believed peculiar to consumptives in which physical wasting led to euphoric flowering of the passionate and creative aspects of the soul. The prosaic human, it was said, became poetic as the body expired from consumption, genius bursting forth from the fevered combustion of ordinary talent, the body burning so that the creative soul could be released. Keats’ great poetic output during his last year was considered a direct consequence of consumption.

Spes phthisica, which sought to make sense of the senseless and give purpose to purposeless suffering and death, came to be viewed as a prerequisite for creative genius. French author Alexandre Dumas fils wrote, “It was the fashion to suffer from the lungs; everybody was consumptive, poets especially; it was good form to spit blood after any emotion that was at all sensational, and to die before reaching the age of thirty.” Dumas’ colleague, the poet Théophile Gautier, wrote, “…I could not have accepted as a lyrical poet anyone weighing more than ninety-nine pounds.” A subsequent alleged decline in the arts was even blamed on decline in tuberculosis incidence.

Opera and the Novel

In the 19th century, it seemed as if everyone was slowly dying of consumption. Without explanation, the good and the bad, the young and the old, all shared the consumptive fate. Consumption came to be viewed not in medical terms (medicine had little to offer anyway), but in popular terms, first as romantic redemption, then as reflection of societal ills. The consumptive prostitute, for example, could be a moral deviant redeemed by suffering and death. Redemption occurred not in the confessional, nor in the "last rites," but in consumption’s physical sacrifice. Alternatively, the prostitute could be merely a woman victimized by a corrupt society.

Opera perhaps provides the most powerful examples of romantic redemption through tuberculosis. The pallor and wasting, the burning sunken eyes, the perspiration-anointed skin—all hallmarks of the disease—came to represent haunted feminine beauty, romantic passion, and fevered sexuality, notions reinforced by the excess of consumption deaths in young women. Of several operas that deal explicitly with consumption, three (written within a 6-year interval but produced successively over the last half of the 19th century) show the evolution in thinking about the disease.

Verdi’s La traviata[The Straying One] is based on La dameaux camélias [The Lady of the Camellias], Dumas’ tale chronicling the life of Parisian beauty Rose Alphonsine Plessis (also known as Marie Duplessis, 1824–1847). Violetta, the heroine, is a courtesan whose loveliness is stereotypically enhanced and made unforgettable by progressive consumption. So strong was the expectation that women dying of consumption be beautiful ghosts that, at La traviata's 1853 premiere, the audience broke out laughing when Violetta, played by the ample soprano Fanny Salvini-Donatelli, was told she had only hours to live.

The plot of La traviata develops around the consequences of Violetta’s scandalous past, which prevents her marriage to an honorable man whose family objects. In the libretto (by Francesco Maria Piave), Violetta links Alfredo’s acceptance to a cure for her consumption. Referring to their separation, she asks, “Do you know the fatal ill, That attacks my life—to kill? That already draws the end? And you’d part me from my friend!”

Eventually realizing that redemption is possible only through death, Violetta withdraws to her former world to suffer and die for love: “If he knew the sacrifice Whereby love I atone—Knew that to my last breath I loved just him alone…." In taking her life, consumption also serves as a vehicle for atonement. Violetta dies redeemed in the eyes of Alfredo and his father, her labored breaths fading as she pleads: “Look at me! I breathe for you still.”

Produced only 28 years later (1881; the year before Robert Koch’s "discovery" of Mycobacterium tuberculosis), Les contes d’Hoffmann [Tales of Hoffmann] exhibits an important shift in thinking about consumption. In Hoffmann, the beautiful consumptive Antonia is treated by the charlatan physician Dr. Miracle. At the time of Keats’ death, in 1821, little could be done to treat phthisis; the physician's role was in prognosis. By 1881, the “medicalization” of consumption was in full swing, with diets, nostrums, regimens, and activity lists (all of little or no benefit).

By portraying Antonia as a victim of quackery, Hoffmann satirizes medical impotence. Further, the opera links Antonia’s consumption to her mother’s. Heredity as a possible cause of consumption (a popular concept before Koch’s discovery) appealed to the opera’s audience because it absolved the patient from guilt or shame. Heredity as cause may have also appealed to the opera’s composer Jacques Offenbach—both he and his son were consumptive. The libretto (by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré) seems also to presage a new medical concept, a mycobacterial neurotoxin postulated as the cause of spes phthisica after Koch’s discovery.

In Hoffmann, Dr. Miracle asks, “Well, this trouble she inherited From her mother? Still progressing. We’ll cure her.” As he forces her to sing, in what amounts to a musical exorcism, he notes, “The pulse is unequal and fast, bad symptom [sic]. Sing.” The ghost of Antonia’s mother, conjured by Dr. Miracle, calls to her, and she sings frantically, an artistic representation of her consumptive decline. Nearing death, she asks, “What ardor draws and devours me? I give way to a transport that maddens. What flame is it dazzles my eyes. A single moment to live, And my soul flies to Heaven.” Antonia is merely a victim, not burdened by sins that need to be atoned for. Unlike Violetta, she dies maddened by disease, without comprehending why and without making any moral choice.

By 1896, the cause of consumption had been discovered. Tuberculosis or TB (as the disease was now known to everyone) had also been definitively linked to poverty and industrial blight, child labor, and sweatshops. A contagious disease and shameful indicator of class, it was no longer easily romanticized in conventional or artistic terms. Public health efforts to isolate the infected and control their behavior were everywhere.

Giacomo Puccini’s La bohème (1896) presents tuberculosis as social commentary and features characters new to opera, street artists living with poverty and disease. The opera was fashioned from Bohemians of the Latin Quarter by Louis-Henri Murger, a young writer who also died of tuberculosis. The heroine, Mimì, is based on Murger’s friend Lucille Louvet. A poor seamstress portrayed as a fevered beauty whose allure is heightened by physical decline, Mimì loves a poor poet named Rodolfo. He first loves her in return but then abandons her, fearing he cannot provide for her and (possibly) fearing contagion.

In the libretto (by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica), Mimì tells Rodolfo, “My story is brief. I embroider silk and satin at home or outside. I love all things that have gentle magic, that talk of love, of spring…the things called poetry. Do you understand me? They call me Mimì. I don’t know why. I live all by myself and I eat alone. I look at the roofs and the sky. But when spring comes the sun’s first rays are mine. April’s first kiss is mine, is mine! A rose blooms in my vase, I breathe its perfume, petal by petal.”

Later, in the winter cold, Mimì is reconciled with Rodolfo and dies beside him. In one of opera’s most enduring scenes, there is no attempt at metaphorical understanding. Mimì dies literally. No one is saved, no one is redeemed, and no larger point is made. Opera and tuberculosis have entered a new era, recognizable today, in which tragedy is seen as experiencing loss but is not understood in an artistic or philosophical sense. In the moments before her death, Rodolfo tells Mimì that she is “beautiful as the dawn.” “You’ve mistaken the image:” she corrects him, “You should have said, beautiful as the sunset.” Mimì dies surrounded by a philosopher, a poet, a painter, a musician, and a singer—the arts had become powerless against tuberculosis.

Even though new, La bohème’s approach of pointing the finger at society as the cause of human suffering was not unprecedented. An earlier example from literature is Victor Hugo’s Les misérables [The Outcasts], published in 1862. In the novel, the hounded protagonist (Jean Valjean) finds redemption in the child of a dying woman (Fantine) who had been forced by poverty into prostitution. Like Mimì’s in La bohème, Fantine’s death from consumption is portrayed as a consequence of social ills. Society, Hugo says, victimizes good people by putting them in hopeless circumstances.

Of Fantine’s death Hugo writes with a simple beauty that is eloquent even in translation. Like the “afterthought” the world had regarded the poor woman’s entire life, the paragraph describing her death is inserted almost randomly, in retrospect: “We all have one mother—the earth. Fantine was restored to this mother. [She] was buried in the common grave of the cemetery, which is for everybody and for all, and in which the poor are lost. Happily, God knows where to find the soul. Fantine was laid away in the darkness with bodies which had no name; she suffered the promiscuity of dust. She was thrown into the public pit. Her tomb was like her bed.”

In the same romantic context is Hugo’s earlier novel Notre-Dame de Paris(1831), which featured the grotesque and deformed “hunchback” Quasimodo. In those days, the principal cause of severe spinal deformity was Pott’s disease, tuberculosis of the spine. What Hugo knew of this condition can only be speculated, but as a leading poet, he would unquestionably have been familiar with the life of one of England’s greatest poets, Alexander Pope (1688–1744), a hunchback severely deformed in childhood by Pott’s disease. Bent to a height of 4½ feet, at age 47, Pope famously described “this long disease, my life” in “An Epistlefrom Mr. Pope, to Dr. Arbuthnot.” Quasimodo’s physical “otherness” is Hugo’s device for insisting we recognize his humanity, without judgment, in all its dimensions, good and ill.

Notre-Dame de Paris carries a simple message, one expunged from many films and operas made of the book. Hugo writes that long after the events depicted in the novel, workmen discovered two entwined skeletons, one of a young woman, the other of a man with a twisted spine. After La Esmeralda’s execution, the reader surmises, Quasimodo had gone to end his life beside the woman who had found him so repugnant. In death, his disfigurement and her beauty alike were dissolved in dust. All of Quasimodo’s actions, misunderstood by everyone else, are explained by love, as pure in the deformed, slow-witted bell-ringer as in the beautiful saint.

Operatic and literary examples show the romantic transformation of tuberculosis. Only rarely in the period before Koch's discovery was the disease portrayed realistically in artistic works. The most powerful example of realistic portrayal may be Tolstoy's Anna Karénina (1877). Apparently based on Tolstoy's own brother Nikolai, the novel’s character Nikolai Levin suffers an agonizing and vividly depicted death. "A desire for his death was now felt by everyone who saw him; by the hotel servants and the proprietor…by Maria Nikolayevna, Levin, and Kitty. [I]n rare moments, when opium made him find momentary oblivion…[he] expressed what he felt more intensely in his heart than all the others: ‘Oh, if only it was all over!’ or ‘When will this end?’ There was no position in which he could lie without pain, there was not a moment in which he could forget…And that was why all his desires were merged into one—a desire to get rid of all the sufferings and their source, the body." Unlike the prostitute whose death provided Jean Valjean's redemption, Maria was rescued from prostitution by Nikolai and nursed him when he was abandoned. As Nikolai entered the long descent into suffering and death, Maria's love was his only human connection.

Go to:

Science and Public Health

The Romantic Era of Consumption (1821–1881)

At the beginning of this period, the stethoscope was invented and used to diagnose phthisis, and statistics were compiled by population-oriented proto-epidemiologists (e.g., Louis-François Benoiston de Châteauneuf) and by clinical proto-epidemiologists (e.g., Pierre-Charles-Alexandre Louis). In the 1820s, contagion was beginning to coalesce into a modern concept, although it was not imagined in chronic conditions like phthisis. Science was beginning to understand the disease clinically and epidemiologically (not yet etiologically). It was left to the arts to make sense of misery and death in ways that turned otherwise senseless suffering into human dignity and hope, allowing consumption to reveal the innate worth even of prostitutes, the impoverished, and the socially outcast.

Discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (1882–1952)

At the end of the 19th century, romantic notions about tuberculosis were replaced by scientific ideas and products: vaccines and therapies, rest cures, tonics, lobectomies, pneumonectomies, thoracoplasties, “artificial” pneumothoracies, phrenic nerve crushings, plombage, pneumatic cabinet treatments, and antiseptic injections into the pleural spaces. Surgeons packed the pleural cavity with fat, paraffin, and even Ping-Pong balls. In contrast to the arts, science and medicine were unapologetically prosaic.

Over a 70-year span, tuberculosis literally transformed Western society. Tuberculosis patients were excluded from many occupations. Married patients had to sleep in separate beds from uninfected spouses and were counseled to avoid sex and especially to not have children. Public health nurses visited door to door, sanatoria were built by the hundreds, and hospitals added tuberculosis wings. Cold water hydrotherapy, alcohol massages, and brisk rubdowns with coarse towels were prescribed. Millions of spittoons and cuspidors were placed in homes and public places. Patients’ bed linens were changed daily and were boiled and laundered separately. Handkerchiefs (for those who could afford them—cut-up pieces of muslin for the rest) were stuffed in pockets before leaving home, then disinfected or burned at night. Japanese “paper handkerchiefs” became popular, leading eventually to the modern “facial tissue.” Tuberculous women had to forego corsets and brassieres in favor of loose-fitting clothes. Life insurance policies added clauses canceling benefits for the tubercular, and hotels and landlords refused to serve them. Compulsory registration, immigration bans, and even interstate travel restrictions were debated. Suicides in towns with sanatoria increased.

Prevention efforts were put in place. National antituberculosis programs were led by U.S. presidents. Ubiquitous “ad campaigns” featured catchy tunes some called “jingles.” Architects designed alcoves to hide concealed spittoons in middle-class homes. Babies were no longer allowed to play on the floor, and mothers were told not to kiss children on the mouth. Some churches abandoned the “common” communion cup. "TB" and “x-ray” became household words. Streets were watered down before sweeping to prevent aerosols. Long “trailing” dresses went out of fashion because they dragged on the ground and picked up potentially infectious dust. Store candies and bakery loaves had to be wrapped; public libraries and their books were regularly disinfected.

Modern Times (1952–2002)

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, a truck cycled through neighborhoods to administer chest x-rays, and schools provided “tine tests.” Patients sat in big sunrooms off hospital wards, semi-erect in lounge chairs, wrapped like mummies on an ocean cruise. Family members disappeared for long periods—off to sanatoria for “rest cures.” People bought Christmas Seals, and spoke in a slight hush when they mentioned “TB.” As a medical student in the 1960s, I remember the second patient I ever examined. Born in 1879, she had undergone a right phrenic nerve crush, sometime around 1910, surviving tuberculosis to the age of 90.

The 1950s represented the cusp of a new era in which drug treatment would end tuberculosis visibility in industrialized countries. People still read Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain(1924), which was set in the real-life sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland, but less to learn about tuberculosis and more to understand the “Sanatorium Movement.” The modern tuberculosis era began around 1952 with antituberculosis chemotherapy, but more die of the disease today than in the 19th century. Medicine and public health have answers but lack the will to apply them. Tragedy now derives not from unknown evils out of our control but from known evils we do not control.

Art is redemptive. Even in modern times, when artistic expression seems to have moved to other causes of human suffering, occasionally dramatic irony sneaks backstage to comment on the empty theater of tuberculosis progress. In 1967, a woman born in India, acclaimed a great actress in such roles as Anna Karénina and Scarlett O’Hara (Gone with the Wind), died of tuberculosis. Starring at the time in a long-running play, Vivian Hartley (stage name Vivian Leigh) began to experience cough, then fever. Within a few months she was dead. The accidental irony was pure “theater.” The play was Chekhov’s Ivanov. Vivian Leigh, a wealthy woman dying of tuberculosis, was starring in a play about a wealthy woman dying of tuberculosis, written by a wealthy physician dying of tuberculosis. One may imagine that when art fails to imitate life, life may have no recourse but to imitate art.

Odysseys

In the early 1980s, I realized a boyhood dream, to climb an isolated peak called Mount Vaea, on the remote South Pacific island of Upolu, in what is now Western Samoa. Around that time, one of my patients, born on a Pacific island and admitted to my American hospital for tuberculosis, had walked up to the nursing station for some trivial purpose and in the middle of a conversation with the nurse, had suddenly opened his mouth to an explosion of arterial blood that shot across the room, overflowed like a waterfall to the linoleum floor, and caught him in its plumes as he sank downward and died—suffocated or drowned.

A century earlier, in 1880, coughing blood and dying more slowly, Robert Louis Stevenson fled his consumptive sentence. He escaped to Davos, to rugged sea-swept Speyside, and to sunny Marseille. All the while, he worked on the great books we still read all over the world, Treasure Island,Kidnapped—novels of escape.

Surviving a succession of hemorrhages, Stevenson climbed hills and sailed oceans, following the medical advice of his time. In New York, he stayed at Saranac Lake, America’s most famous sanatorium. In San Francisco, he was farther from home than he had ever been. Still the hemorrhages and wasting continued. Escaping ever farther, he went to Hawaii, lived in a grass hut, and told stories to the King and Queen. He went on to Sydney, Australia, where he had additional hemorrhages, and at last to Upolu. Tuberculosis nevertheless continued to consume him. He wrote every day, suffering sudden hemorrhages, waiting to be “weaned from the passion of life.”

The doctors said it was a stroke that felled him in December 1894. The 44-year-old Stevenson was placed on a bed in the middle of the room. Family and friends beside him, his Samoan “family” kneeling in a circle all around, the great Tusitala, “teller of tales,” took a last breath. A council of chiefs was called, appointing 40 strong men to carry out Stevenson’s final wish. They carried his body up to the top of the highest mountain and buried him in the place he had chosen.

Although I have visited the place several times—once dragging a famous epidemiologist barefoot up the mountain—it was the first time, 20 years ago, that I remember most clearly. I reflected then that in 1891, when Stevenson had escaped to Upolu, tuberculosis was still a disease of wealthy industrial nations. To run from it, Stevenson had to leave behind everything else in his life: family, friends, mother country, home, comfort. He fled to the very end of the earth.

Now, more than a century later, tuberculosis has escaped to the places where its victims once sought refuge, the one-time colonies of Western nations. The disease destroys the poor and underprivileged as it once destroyed the wealthy—95% of cases and 98% of deaths occur in the developing world. Its ravages are worst in the Pacific Islands. I wonder if the victims, who are too often beyond the reach of Western cures, have their own operas, poems, or plays to explain their predicament. I wonder where they escape. Do their escapes, like Stevenson's, lead only to resignation and surrender?

On top of Mount Vaea, at 1,500 feet, a small promontory shows the blue Pacific in a broad sweep. Facing “Magic Mountain” half a world away, you see a blue curtain above and below the horizon. At night, the sky is indeed wide and starry. The Southern Cross sparkles wildly, too low and too close to be celestial. The sarcophagus, placed at the highest point, is of white plaster, like the walls of the European hospitals and sanatoria Stevenson had fled. The plaque is of shiny brass, so that even in the moonlight, sometimes even in the tropical starlight alone, it is possible to read the words engraved on the side of the tomb. It is Stevenson’s “Requiem,” the poetry of his last resigned step in a long but unsuccessful flight.

Under the wide and starry sky,

Dig the grave and let me lie.

Glad did I live and gladly die,

And I laid me down with a will.

This be the verse you grave for me:

“Here he lies where he longed to be;

Home is the sailor, home from the sea,

And the hunter home from the hill.”

Sources

Barber S. Quartet, strings, Op. 11, B minor [musical score]. New York: G. Schirmer; 1939.

Barbier J, Carré M. Les contes d’Hoffmann, opéra en quatres actes [libretto]. Paris: Calmann Lévy; 1853.

Barnes DS. The making of a social disease: tuberculosis in nineteenth-century France. Berkeley (CA): University of California Press; 1995.

Bates B. Bargaining for life: a social history of tuberculosis, 1876–1938. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1992.

Benoiston de Châteauneuf L-F. De l'influence de certaines professions sur le développement de la phthisie pulmonaire. Annales d'hygiène publique et de médecine légale 1831;6:5–49.

Bushnell OA. The gifts of civilization: germs and genocide in Hawaii. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press; 1993.

Chekhov AP. Five plays [English translation]. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1997.

Coleridge ST, Shelley PB, Keats J. The poetical works of Coleridge, Shelley, and Keats, complete in one volume. Philadelphia: J. Grigg; 1831.

Dubos R, Dubos J. The white plague: tuberculosis, man and society. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.; 1952.

Dumas A (fils). La dame aux camélias. Paris: D. Giraud et J. Dagneau; 1852. Giacosa G, Illica L. La Bohème (Scène de la vie de Bohème de Henry Murger) [libretto]. Milano: Ricordi; 1896.

Guillaume de Machaut. Jugement deu roy de Navarre. In: Guillaume de Machaut. Les œuvres de Guillaume de Machault. Paris: Techener; 1849.

Hoffmann ETA. Rath Krespel. In: Hoffmann ETA. Die Serapion-brüder. Berlin:G. Reimer; 1821.

Hugo V-M. Notre-Dame de Paris. Paris: J. Olaye; 1831.

Hugo V-M. Les misérables. Paris: Pagnerre; 1862.

Hugo V-M. Les misérables [English translation]. New York: G.W. Carleton and Co.; 1880.

Hunt L. Lord Byron and some of his contemporaries: with recollections of the author’s life, and of his visit to Italy. 2nd ed. London: H. Colburn; 1828.

Jacobson AC. Genius: some revaluations. New York: Greenberg; 1926.

Keats J. The poetical works. New edition. London: E. Moxon; 1846.

Keats J. Letters of John Keats to Fanny Brawne, written in the years MDC- CCXIX and MDCCCXX and now given from the original manuscripts with introduction and notes by Harry Buxton Forman. London: Reeves and Turner; 1878.

Keers RY. Pulmonary tuberculosis: a journey down the centuries. London: Ballière Tindall; 1978.

Knopf SA. Tuberculosis. In: Stedman TL, editor. Twentieth century practice: an international encyclopedia of modern medical science by leading authorities of Europe and America. Vol. XX. Tuberculosis, yellow fever, and miscellaneous. General index. New York: William Wood and Co.; 1900. p. 3–396

Knopf SA. The social aspects of tuberculosis [pamphlet]. Publisher not indicated; 1908.

Koch R. Die Aetiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, begründet auf die Entwick- lungsgeschichte des Bacillus Anthracis. Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen 1876;2:277–310,11 figures.

Louis P-C-A. Recherches anatomico-pathologiques sur la phthisie. Précédées du rapport fait à l'Académie royale de médecine par. MM. Bourdois, Royer- Collard et Chomel. Paris: Gabon et Cie; 1825.

MacMurray JM, editor. The book of 101 opera librettos. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal; 1996.

Main PA. The origin and history of tuberculosis. In: Covacevich J, Pearn J, Case D, Chapple I, Phillips G, editors. History, heritage and health: proceedings of the Fourth Conference of the Australian Society of the History of Medicine; 1995 July 2–9, Norfolk Island. Brisbane: The Society; 1996. p. 149–51.

Mann T. Der zauberberg. Berlin: S. Fischer; 1924.

Mikelova L. La Traviata and the New York Times, 1859 to 1985. Opera reviews and the cultural response to tuberculosis. In: Cruse P, editor. The proceedings of the Annual History of Medicine Days, Faculty of Medicine, University of Calgary. Calgary: University of Calgary; 1998. p. 229–36.

Mitchell M. Gone with the wind. New York: MacMillan; 1936.

Moorman LJ. Tuberculosis and genius. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1940.

Morse MM. Through the opera glass: a critical analysis of tuberculosis as presented in opera. Pharos 1998;61:11–14.

Murger L-H. Scènes de la [vie de] Bohême. Paris: Michel Lévy frères; 1851. Ott K. Fevered lives: tuberculosis in American culture since 1870. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1997.

Petrarcá F. Opera del preclarissimo poeta miser Francesco Petrarcha con li comenti sopra li Triumphi: Soneti: & Canzone historiate & nouamente corette per Miser Nicolo Perozone co molte acute & excellente additione. Milano: I. A. Scinzenzeler; 1512.

Piave FM [libretto], Verdi G [score]. La traviata; opera tragica [piano-vocal score]. Napoli: Stapilimento musicale Partenopeo; 1853.

Pope A. The works of Alexander Pope, esq. Edinburgh: J. Balfour; 1764. Reibman J. Phthisis and the arts. In: Rom WM, Garay SM, editors. Tuberculosis. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co.; 1996:21–34.

Rosenktantz BG, editor. From consumption to tuberculosis. New York: Garland Publishing; 1994.

Rothman SM. Living in the shadow of death: tuberculosis and the social experience of illness in American history. New York: Basic Books; 1994.

Ryan F. The forgotten plague: how the battle against tuberculosis was won— and lost. Boston: Little, Brown & Co.;1992.

Shelley PB. The poetical works of Percy Bysshe Shelley. In four volumes. London: Edward Moxon;1839

Sontag S. Illness as metaphor. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux; 1978.

Stevenson RL. Ordered South. MacMillan’s Magazine. Volume XXX. 30 May 1874. p. 68–73.

Stevenson RL. Kidnapped, being memoirs of the adventures of David Balfour in the year 1751. London: Cassell; 1886.

Stevenson RL. Treasure Island. London: Cassell; 1883.

Stevenson RL. Underwoods. Book I. In English. London: Chatto and Winders; 1887.

Tolstoy LN. Anna Karénina [English translation]. New York: T.Y. Crowell & Co.; 1886.

Tolstoy LN. Anna Karenina. New York: Penguin Books; 1961.

Tomes N. The gospel of germs: men, women, and the microbe in the American life. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1998.

Virchow R. Einige Bemerkungen über die von Herrn Dr. Hartsen aufgeworfene Frage über die Zulässigkeit des Geschlechtsgenusses bei Phthisiskern. Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medicin 1870;49:577–9.

Whitman W. Leaves of grass. Philadelphia: David McKay; 1884.

#consumption#tuberculosis#infectious disease#disease#illness#medicine#disease and culture#art#literature#tragedy#robert louis stevenson#opera#suffering#culture

0 notes

Photo

Aurene’s magic hadn’t conflicted with Camélia’s powers. People always assumed that dark and light were opposites; it wasn’t true, they were part of each other. White light and purple void. It was balance. Destiny, one might even say.

55 notes

·

View notes

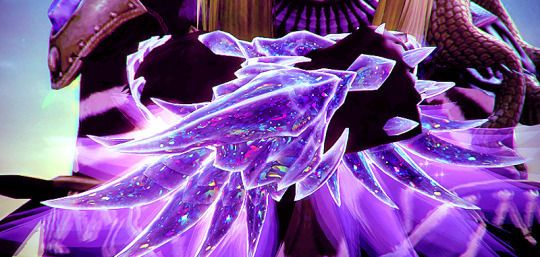

Photo

Serpentine Prism

#guild wars 2#gw2#Camélia Nightingale#Human (♢)#half-alien#holy shit she REALLY looks like a space captain now im in love /cries

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Camélia's hex was an unstoppable force against her. Forced to kill every member of her bloody cult, she relentlessly followed an unconventional redemption. It was a devastating and straightforward path. But that changed when the last person she had to kill died abruptly. Absorbed by the young Aurene, Joko was gone before the hex could be dispelled. Freedom came despite it. So did a crystalline resonance. A link between Aurene and Cámelia was established: from ancient magic, bloomed a brand, slowly manifesting on her body.

Seeker Camélia Nightingale, the Terror of Xhersgla, the Consumer of Galaxies, Blighted Nightingale, Serpent of Taleia'Mar, daughter of the last Void Blessed Empress.

Amidst chaos, rebirth called.

Herald of Aurene.

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

she's a reformed antagonist, she's a universe saving heroine. need i say more? happy pride month

#guild wars 2#gw2#Camélia Nightingale#Human (♢)#half-alien#Yassa'Luza#Monoceri (♢)#unicorn#alien#my art#lesbian

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Starlit storms calling across galaxies—

The universe is a deeply mysterious expanse and many secrets are held together within it. One of them is a traveling starship by the name of Tempest’s Gaze. Its Captain, [Camélia Nightingale] of mixed human and alien heritage, is a former galaxy conqueror. After an arduous redemption that took her over three hundred years she found another path in her life.

During this time connections blossomed from the promising soil of second chances, and the crew of the Tempest’s Gaze was built: Navigator [Lemonade Comet], Chief Engineer [Althea Alma], Tempest’s AI [the Starlight Queen], Archangel [Val Ima Astre], and Xenobiologist [Zaturnu]. Little by little, among the ancient stars, they became home to each other. A tale that has lasted over two centuries.

When the intense magical energy in the world of Tyria pinged on the Tempest’s Gaze sensors, they found themselves on a planet with a turbulent fate. But perhaps they were all along meant to step on it, as so many threads of their pasts are intertwined with this strange place.

#guild wars 2#gw2#Camélia Nightingale#Althea Alma#Human (♢)#half-alien#cambion#the Starlight Queen#Android (♢)#AI#Zaturnu#Astral (♢)#Lemonade Comet#Lumen (♢)#fanlore#tempest's gaze

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Two thousand and sixty five years ago in a distant galaxy

Camélia and Val Ima Astre stepped through the empty corridors of the Faro palace. Tall cogs in the shape of winged chimeras were whirring ever so softly on their right; white light was shining from their left, illuminating the angular faces of the creatures. Camélia's eyes lingered a little too long on the passing sights. Sometimes because of how bizarre the contrast of her presence was to everythingand everyone—around her.

The translucent curtains had no ending or beginning; it was just a constant of formless shimmery veils, beneath them glitter danced around the minimalist archways. The walls and floors were like mirrors, occasionally the pulsating plasma could be seen reflected on the surfaces.

All the colors were comforting. Light cold blues and celestial silvers felt like a home you had forgotten. Even if you had no home at all.

Holographic birds on the windows were the only sound that could be immediately perceived. Like the most pleasant wind chimes on a stormy day. Leaving behind trails of feathers and incandescent dust.

It was both alien and angelic. The silence in-between their heels clicking on the floor—and the delight of a vision almost unreal—made it all feel like a deity's paradise.

And paradise wasn't for Camélia.

"There's no reprieve for people like me. I think I get it now. Or I'm starting to let myself get it." Her voice echoed through the hall. It was weird to hear her words coming back to her.

"Do you think you'd still have done it? If they hadn't forced you to kill your cult." Val Ima Astre's eyes glowed in the dim light.

"No. I would have kept going." Camélia looked at the floor. Her reflection stared at her. A somber judgement. "I'm only here because I was forced to change."

Val Ima Astre hummed at her response. As if dismissing her thoughts.

Camélia sighed to herself.

There was a silver touch everywhere. It wasn't moral purity, but it was the purest world she had ever seen. The seraphim were neat to a point that made Camélia uneasy. She couldn't look anywhere without being reminded of who she was.

Past to present. A grim telltale of the massacres she caused were carved into her very bones.

"I hope you aren't going soft. Still have to kill me at some point," Camélia said matter of factly. A little too matter of factly.

"I dunno." She snorted.

"Archangel. Death is the only punishment for me." Camélia slowed down until she stood still. She never liked when Val Ima Astre didn't seem to get the calamity of what she had done.

"No, it isn't." She stopped a few feet further away from Camélia. "Not if one has been dead for centuries."

"I'm very much alive. Thank you." She rolled her eyes.

"Only technically. Your heart was withered like a dying opal flower." Val Ima Astre turned around. Her gaze was piercing. The seraphim were in their own right terrifying as the all consuming light. "Is death not a comforting embrace then?"

Camélia didn't comment. She stared at the floor again. Between forced destiny and no choice. Maiming for justice. Or was it revenge? She didn't know where the astrals stood in the balance.

Maybe both. Maybe neither. They stopped her for good though.

"Now… life. Life is a much harder challenge. The true atonement comes from living through the misery you created," she said in an almost jokingly tone.

"I'm tired of this." Camélia breathed hard through her nose and turned to face the massive windows. "I bet the astrals are too."

"Zaturnu isn't." Her wings twitched.

"C'mon! Zaturnu is just…" She rubbed her temples. "Just too stubborn."

"I think she just likes you," Val Ima Astre said.

"Astre. Don't." Camélia tensed up.

"Huh uh." She ignored Camélia's tone and continued. "The reeeal question is: If your hex was lifted right now. What would you do?" Irritating, Camélia thought

"Hopefully never talk with you again." She snarled.

"That's not what you said last evening while dancing in the plaza with me." Val Ima Astre waved her left wing in Camélia's face, slapping her playfully with the luminous feathers.

Talking with Val Ima Astre never failed to make Camélia feel too old; even if by all means they were both immortal. Yet, they were facing eternity in completely different ways.

Camélia couldn't help to be a little jealous. She had no idea what was like to indulge in life.

"I didn't have a choice," she finally blurted out while trying to push the wing away.

"You did. You can still choose to be distant. Chaotic. Severe. Unwelcoming." Val Ima Astre reached out for Camélia's hand. Camélia flinched, eyes still stuck on the nothingness of the landscape outside.

The silver desert. Glowing with life despite how harsh the winds could be.

"Do you want to keep relying on the bones beneath your feet? Or do you want to learn to live a little bit?"

Choices while chained. Camélia moved her yellow snake eyes to the corner of her vision. She could see Val Ima Astre's argent hair. And a glimpse of her smile.

Bothersome.

"I think I'm starving now." Camélia finally said.

Val Ima Astre wheezed. "Aight, Dear Camélia. Let's us dine."

"I hope you choke on your food, Astre." She grinned, baring her fangs without a care.

"You wish." Her smile widened.

#under the readmore is a introduction of sorts for the character! i hope you enjoy the story :)#guild wars 2#gw2#Val Ima Astre#Seraphim (♢)#seraphim#also featuring in the story:#Camélia Nightingale#my writing#fanlore#stories

96 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Camélia was the first person the Starlight Queen came in contact after being deactivated for eons on a dead planet. Somehow she thought Camélia was a prophetic sign, and does treat her like a chosen one to this day.

What she is chosen to do? Well, Starlight can’t access her data core, so she thinks Camélia will lead her to the last living person of her people who will unlock it. Call it a cyber hunch. (For Camélia’s displeasure.)

But hey it doesn’t change anything, Starlight is still the Tempest’s Gaze AI whether her belief is true or not.

I like to think how the characters of my crew met, so here’s one!

Inspired by the song “Chosen by TheFatRat & Anna Yvette & Laura Brehm“.

#guild wars 2#gw2#my art#Camélia Nightingale#Human (♢)#half-alien#the Starlight Queen#Android (♢)#android#tempest's gaze

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#guild wars 2#gw2#Camélia Nightingale#Human (♢)#half-alien#i finally figured out what was really bothering me#she looked too much like a drow and not enough snake#the hair did it thank u brain today you worked

63 notes

·

View notes

Photo

We’re going down, down, down (unless you have wings)

Nights on Amnoon were always busy. The streets became packed with visitors and locals as dusk arrived. The mingling of smells was intoxicating—incense and cigarettes filled people's nostrils almost instantly. For some it was too much and coughing fits were common. A sharp sound in the midst of pouring crowds.

The chatter of the evening was often animated and vivacious. Much more now that the Grand Sahil Casino was throwing a coin hunt; people laughed and stumbled over each other. The air was thick with life.

But unfortunately it was not a feeling shared by everyone.

Camélia was leaning against one of the walls at the back of the casino, her eyes followed the trails of smoke. Sometimes she wondered why she even bothered trying to be social at all. Her off-hand responses and her spacing out were always met with an accusation of "superiority complex", when in truth it was just hard for her to gather enough words in a world of too many sensations. Most that she had avoided for over four hundred years.

Losing touch. She bit her lip.

"Hey, Mélia, you hiding or something?" Val Ima Astre's voice cut her thoughts short. For better or for worse.

"I'm standing against a wall. That's hardly hiding." Camélia pressed her lips together and huffed.

"Bitey. Why are you so sour?" She intruded right into Camélia's personal space. Val Ima Astre's eyes could be a little unsettling at times, especially if she was trying to figure something out.

"I am always like this," Camélia simply said. She wasn't the biggest fan of Astre's obsessive moods.

"Yeah, but there's like. A surly note in that voice." She tapped her fingers against her legs.

"I had no idea you were an expert on my behavior." She frowned.

Val Ima Astre rubbed her chin. "It's part of an archangel's job to document things."

"You're a lightbearer, not a fucking scientist." She wrinkled her nose and pushed Astre back. "Or were. Whatever happened to your position since you just decided to leave. Again."

"I've been there for… Blessed Light knows how long." Val Ima Astre lamented almost comically. "They don't need me on duty to save the universe. All the time."

Camélia snorted. "I thought you wanted to be one of the fancy senate leaders of the intergalactic-kiss-ass-union?"

It was almost instant. The change of posture. The change of tone. Camélia knew all too well about the weight on Astre's shoulders and yet for some reason she still prodded it.

Perhaps they were both obsessive in their own way.

"I tried it, but it was just empty." Val Ima Astre's wings dropped lower. "It's an important job. An honor even. Mirea Fai Meda hated my brilliant strategic mind, I'm just prefacing that, but she was right. I'm too much of an egocentric weirdo for the job."

Val Ima Astre was now leaning against the wall too, her shoulders somewhat slumped. The silence within the deafening noise of the casino was a cutthroat meeting; a turbulent rise of words skipping between smiles and surly whispers. Between understanding and disagreeing. Between different languages and different flavors.

Out of place. Sugar and spice.

"The best years of my life were making your life hell." Val Ima Astre's gaze was fixated on the ceiling. A salacious smile creeping up on her face.

A weirdo, indeed.

Camélia threw her head back in uproarious laughter, but she hit the wall a little too hard. She cursed herself for being so awkwardly clumsy at times—maybe she, too, ended up being a weirdo. All the finesse and pretense were a long gone song. "Hrgh. Seems like you're still making my life hell, angel." She rubbed the back of her skull.

Val Ima Astre guffawed. She pushed herself off the wall and flapped her wings. "Ohhhh fuck. Do you need some healing?"

"You're not a healer, you stupid divine smiter." Camélia glared.

"Are you insulting the archangels' training in medical prowess?" Val Ima Astre placed a hand over her heart and gasped.

"You clearly failed that course," Camélia retorted.

"Are you still mad I cut your arm off?"

"Imagine if that was my head." Camélia was thankful that medicine at large was far more advanced than what you'd find in Tyria. Or else her arm would have been a goner. "No regenerator could put that back together."

"Oh c'mon. I'm not gonna vaporize your head!!" Val Ima Astre gestured a bit too wildly. Her wings dusting off the floor.

"No is no," Camélia said.

"Can I kiss it better then? I promise I won't poke the crystals on your face."

Camélia let out a deep breath through her nose. Despite her ticked off scales she nodded with a rather silly eye roll. "Fine."

Val Ima Astre cupped her face gently and for a few moments Camélia was petrified. The silence dragged longer than it was necessary; something about Astre's silent presence always made her rattled. In a strange pleasant way. It was not because she disliked the woman's tangents. (Not that Camélia would ever admit it.) But it was unusual. The moments she had seen her dead serious left her somewhat curious for more.

Unlike the empty silence of discomfort, this one felt like a conversation. A soul searching gaze. Camélia fought the urge to look away.

Soulmates. Of some twisted fate.

The Archangel's argent halo glowed against the purple hues of the Captain's brand. A reminder of how much things had changed.

"You still know what a head is, right?" Camélia finally said.

But all she was met with were supple lips against her own. Light and darkness always crossing paths despite everything. As sure as the suns dying out in forgotten galaxies. As sure as the six thousand years behind them both.

Camélia pushed forward and deepened the kiss, earning a soft gasp from Val Ima Astre. Her sharp fangs grazed against her lips. Silver blood glowed so familiarly.

They always ended up stepping on each other's toes. And with their tongues in each other's mouths.

"That's… not my head."

Soft fingers intertwined.

"I know."

Foreheads touched.

"You're insane."

As sure as the stars in the night sky. They would meet again and again. Until the end. If there was ever to be one.

#guild wars 2#gw2#Camélia Nightingale#Human (♢)#half-alien#Val Ima Astre#Seraphim (♢)#my writing#fanlore#stories

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

tempest’s gaze!

#guild wars 2#gw2#Camélia Nightingale#Human (♢)#half-alien#Val Ima Astre#Seraphim (♢)#Zaturnu#Astral (♢)#Althea Alma#cambion#the Starlight Queen#Android (♢)#Zisa'Sunna#Monoceri (♢)#tempest's gaze#my art

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Serpent of Space

#guild wars 2#gw2#Camélia Nightingale#Human (♢)#human#half-alien#AAAAAA I totally forgot I had other photoset of her queued#I changed her look yesterday gbvbvvvvvvgvv#have this

74 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Maybe! Maybe! It’s fate?” Anktauya beamed. “Getting here and finding out something so…” She titled her head and pondered the best way to approach the grim subject.

“Can we just drop this?” Camélia pressed her lips together.

“It’s like a redemption arc. I like those. In the books anyhow,” she quipped.

“You must be joking.” Camélia sneered. “I didn’t kill my lineage only to find out one little piece of the puzzle was still out there causing havoc. In a mist shrouded self-sustained multiverse.”

Anktauya blinked once. Anktauya blinked twice. Maybe thrice too. “You what.” Her mouth was somewhat open. Dazed, almost.

“I what, what?”

“Killed your lineage? Why? What happened?” She bent over to get closer to Camélia. Far closer than the Captain liked.

“If you go to Elona, you can have a whiff of the imperialism. At least that’s done.” She shuddered at what she had witnessed. Part of herself felt guilty. She had a lingering feeling that was one ugly mess she should help with. Even if it was over.

“I’m piecing things together from your nonchalant answers. If I am correct your long living family has been doing this to other planets. Or quadrants.” Anktauya stared at Camélia. Not even once blinking her eyes.

And Camélia thought she was intimidating. Clearly not to this woman.

“You guess correctly, four eared girl.” She grimaced. This was ridiculous, but Camélia was trying to be as nice as possible. Although she was quickly regretting it.

“How have you been alive for so long? Not that it’s unusual but…” Anktauya continued.

“Short version: it’s a pact. Not all of us are strictly biological family. But all of us possess devastating necromantic powers,” she said solemnly, as if recalling something blood curling. “Well… was a pact anyhow. No one’s left.”

“You are,” Anktauya deadpanned.

“So I am,” Camélia said.

“Are you gonna do anything about it?”

Camélia stopped in her tracks. This was not a course of conversation she was expecting from. A tall. Funny speaking woman. With a lot of ears. And a fluffy tail. “Excuse me?”

“What makes you think you’re better than your family?” Anktauya’s heterochromia became less endearing and more like a warning. The colors danced. Strange magic, Camélia noticed.

“We have just met. I don’t even know what are YOU.” She took a step back and frowned in annoyance. What was this? An interrogation? Camélia fumed.

“I’m an Auloni. From generations of lost norn. Offspring of Hya. Blessed by the moon. We’re sort of space explorers. Except I haven’t had the chance.” She straightened her shoulders. “I am a summoner, though. The last of my kind.”

“That’s nice.” Camélia was struck with a feeling she had just become this woman’s new interest. For whatever hellish reason. “I’m just in Tyria to help Zaturnu. The moment she’s done with her quest. I’m off. Or we’re both off. Whichever.”

“Not before you tell me a story or two about some obscure galaxies.” She grinned. Fangs sharp and ears upright. And Camélia didn’t like the look of that at all.

“Why would I do that?” She raised an eyebrow, trying to look unaffected.

“You’re a bard.”

“The non-intimidating way of describing it, yes.”

“What is the intimidating version?” Anktauya stepped in front of Camélia, raising her hands in excitement.

Camélia had the unfortunate span of two seconds to decide how to handle this situation. A) be completely honest or B) wave it off. Somehow she came to the conclusion that both answers would lead to the exact same result. “You’d be a thrall by now.”

“You are like… a space siren!” Anktauya pointed at her. “Can you sing?”

Camélia ran her hands down her face. “Agan'Amhali hold this thought.”

“Who is Agana Mhali? And why are they holding your thought?”

Camélia just walked faster.

#guild wars 2#gw2#Camélia Nightingale#Human (♢)#human#half-alien#Anktauya#Norn (♢)#norn#auloni#my writing#I'm sticking this headpiece on Camélia#stories

44 notes

·

View notes