#Elton t. morrow

Text

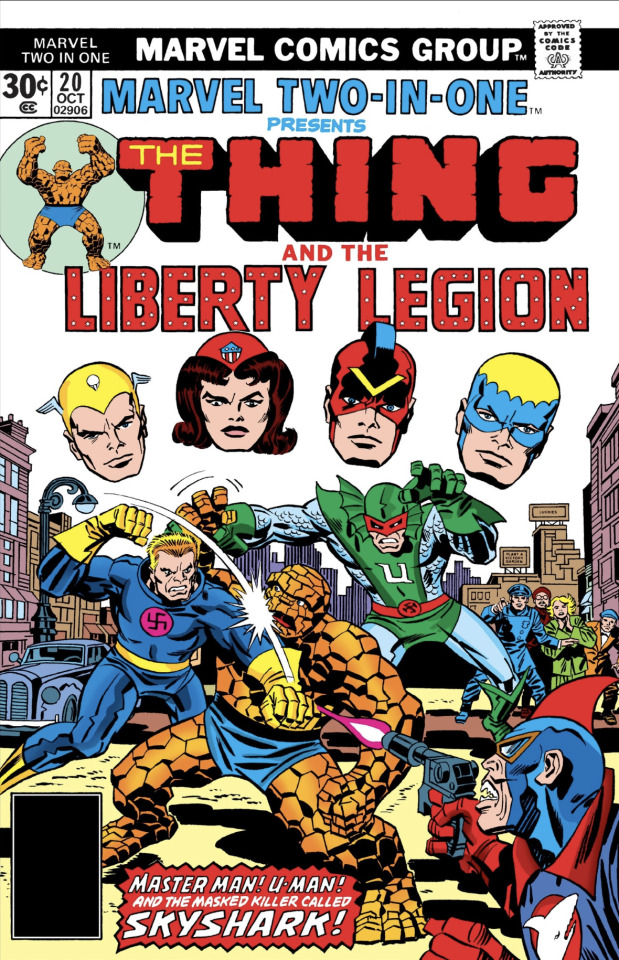

Marvel Two-in-One #20

#marvel two-in-one#the thing#ben grimm#master man#sky shark#u-man#whizzer#robert frank#miss America#Madeline Joyce#red raven#blue diamond#Elton T. Morrow#world war two#time travel#liberty legion#team up#jack kirby#marvel comics#comics#70s comics#bronze age comics

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

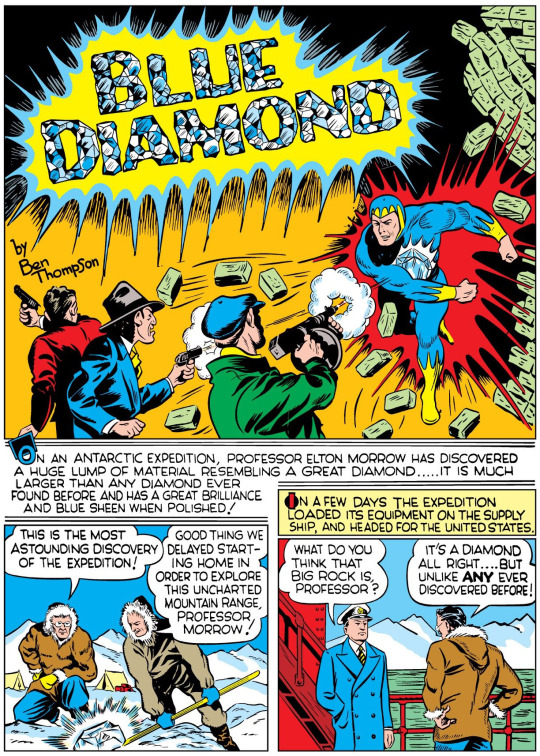

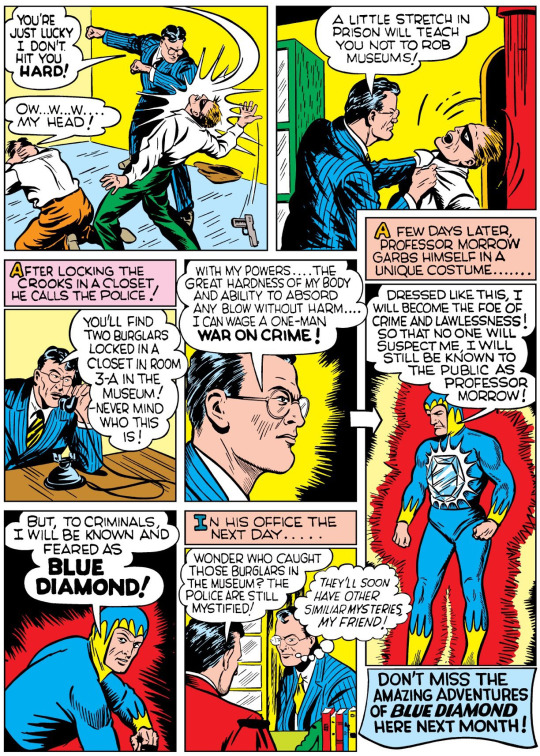

Blue Diamond / Blue Diamond The Bullet-Proof Man

Creator(s): Ben Thompson

Alias(es): Elton T Morrow

1st Issue w/Uniform: Daring Mystery Comics #7

Year/Month of Publication: 1941/04

marvel.fandom.com/wiki/Elton_Morrow_(Earth-616)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friday, 15th July: Emma calls on Miss Fairfax

Read the post and comment on WordPress

Read: Vol. 3, ch. 16 [52]; pp. 296–303 (“Now Emma could, indeed” to “‘good bye’”).

Context

Emma visits Jane Fairfax; they are joined by Mrs. Elton. Emma returns to Hartfield, where she presumes she will find Mr. Knightley. She reconciles with Jane on her way out.

We know that “to-morrow” is “Saturday” (p. 300); previous events mark this as the third week of July.

Readings and Interpretations

Calling on Miss Fairfax

Susan Morgan writes that Jane Fairfax, “dark, quiet, and apart,” is fascinating to readers of Emma; she always seems to be on the “outside” of the narrative, “not part of Emma’s domain”; she has an “independent sense of herself which Emma cannot absorb” (p. 41). “[W]e are kept ignorant” of Jane’s “mind” and “heart” throughout most of the novel, only for the denouement to be just as mystifying:

Finally, at the end of the story, the secret engagement is revealed and Jane is free to be candid and unreserved. And what happens? Jane goes off in a carriage with Mrs. Weston and does open her heart. But the curious reader is not allowed to be present and is given only the briefest account. The last opportunity for getting acquainted with Jane comes when a chastened Emma goes to her home to offer apologies, friendship, and intimacy. And there sits Mrs. Elton, whose presence effectively destroys any hope of speaking freely with Jane. The reader’s disappointment is as great as Emma’s. The single unreserved moment she, or the reader, is allowed with Jane is that hurried expression of apology and good feeling in the hall. It is just enough to be assured of Jane’s natural warmth and charm, but not enough to allow us to know her. (pp. 44–5)

For Morgan, Emma’s disappointment has been caused by her own behavior:

Emma has deprived herself, and the reader, of knowing Jane. Knowing Emma is a delight but the external world, beyond Emma, must also have its allure. When the secret of the engagement comes out near the end of the story one has the sense of emerging from the mind into the area of events. Jane exists outside where acts have consequences, and Emma’s games have caused her real pain. […] We learn that there is no escape into imagination. But we also learn something even more important. Jane’s world, that place outside Emma’s control, is not so very dull after all. Things do happen in idyllic Highbury, even in Miss Bates’s tiny, drab rooms. One need not make up stories for life to be interesting. Emma need not fear that involvement in the world of other people would stultify her. […] How much more interesting it would be to have had Jane’s confidence than Harriet’s. And by the end of the story Emma would probably even admit that matchmaking cannot compare as entertainment to falling in love. (p. 45)

Thus not only is Jane “proof that Emma cannot structure human relations according to her own fancies”; she is also the only character who “provides a worthy alternative to Emma’s imaginings” (ibid.). The novel is not a didactic one that champions the chastening of (female) imagination: rather, “[i]t is about the powers of the individual mind, the powers of sympathy and imagination, and about how these powers can find their proper objects in the world outside the mind,” represented in large part by Jane Fairfax (p. 46). “Emma’s isolating manipulations are wrong not just because they are dangerous or vain or thoughtless or untrue, but because of what she will miss” (p. 45).

Cisely Havely notes that “[i]n the closing chapters of Emma secrecy and disclosure are foregrounded”:

Emma’s own engagement remains secret for a while, and keeping Jane Fairfax in the dark is a ‘secret satisfaction’ [p. 297] which briefly places Emma in a moral position comparable to that previously occupied by Frank and Jane. When Emma has at last pressed Jane into revealing something of her future plans her final outburst is, to say the least, ironic: ‘“Oh! if you knew how much I love everything that is decided and open!” (418) This, coming after Mr. Knightley’s ‘beauty of truth and sincerity’ could suggest that the author herself feels a pang of conscience about her own methods. But like Emma, she has been unable to resist the pleasures of a secret. In the same episode (Emma’s visit to Jane) Mrs. Elton with her hints and ambiguities has effectively been parodying Jane Austen’s part. She knows Jane’s secret and wants to score a few more points off Emma by hinting at her superior knowledge and yet withholding it […]. Although this is wonderfully comic, the sterner reader will acknowledge that Mrs. Elton's behaviour is very reprehensible. Yet it is only a cruder version of Jane Austen’s own narrational strategies. An odd pun — ‘ridicule’ for ‘reticule’ — at a moment of complex knowing and not knowing underlines the doubleness of language at this juncture. (pp. 233–4)

Havely makes, therefore, the common point that Austen (or her narrator) allows herself literary freedom which the characters are denied.

Miss Bates’s speech is at times as ambiguous as Mrs. Elton’s, but less intentionally so. Thus Kathleen Steele:

Miss Bates, head full of her niece’s engagement, cannot help herself from talking about “Jane’s prospects,” their “happy little circle” at home, and the “charming” and “very friendly” Frank. Unsure of who knows what information and wanting desperately to share this important and celebratory news, Miss Bates expresses a number of incomplete thoughts, illustrated by the thirteen dashes that mark this passage. In an effort to maintain secrecy, she erases the grammatical subject of intonation units 12–14 [“‘Charming young man!—that is—so very friendly’”], praising Frank without mentioning him by name; in unit 15 she pretends that she had been talking about their doctor, Mr. Perry, though both Emma and the reader know the truth. Still, she obeys the two main discourse constraints. Perhaps the surety of Jane’s upcoming marriage allows her to better control her speech. Tasked with an important, but not emotionally distressing responsibility—being the bearer of a happy secret—Miss Bates finds she is at the center of the Highbury circle. Yet this time, she is not the object of disdain; the excitement she feels still has a cognitive effect on her language, and requires effort to control, but here that effort is less wearying, less anxiety-ridden. (n.p.)

Quoting and Misquoting

Bharat Tandon notes that, in Emma, Austen repeatedly turns allusions and quotations “to creative, and sometimes distinct, comic ends” (p. 30). In this section, when Mrs. Elton attempts to quote two lines from a poem in reference to Frank and Jane, her “literary tactlessness produces [an] unintended effect on which Austen seizes”:

Once the news of Jane and Frank’s secret engagement begins to be revealed, Mrs Elton, typically, attempts to score points off Emma on the mistaken assumption that she is out of that particular loop […] and makes some unsuccessfully ‘coded’ remarks to Jane: ‘Let us be discreet—quite on our good behaviour.—Hush!—You remember those lines—I forget the poem at this moment: “For when a lady’s in the case, / You know all other things give place.”’ What is surprising about this moment is not that Mrs Elton is misquoting yet again, but the specific pitch and context of the poem that she misquotes. John Gay’s animal fable of ‘The Hare and Many Friends’, first published in 1727, is primarily an emblem for the perils of inoffensiveness. The hare of the title assumes she has secured the loyalty of all the other animals by being superficially polite to them (‘Her care was, never to offend, / And ev’ry creature was her friend’ 25 ), only to find that, when the hunt arrives, those same animals are too keen on their own affairs to offer any practical assistance, as demonstrated by the bull:

Love calls me hence; a fav’rite cow

Expects me near yon barley mow:

And when a lady’s in the case,

You know, all other things give place.

So, in effect, Mrs Elton has compared the two young lovers, whose happiness she is supposedly promoting, to a pair of cattle in the breeding season; nevertheless, her tactless allusion is then brought in line with the novel’s meditations on what goes to make up true and false friendship (‘You have been no friend to Harriet Smith, Emma’ (p. 66)). (pp. 31–2)

Gabrielle White notes the misquoting, writing that “[r]eplacing what a ‘stately bull’ pleads as excuse with the word ‘For’ could intend a mean jibe by Mrs Elton at the secret engagement; though perhaps it is all just a muddling through. That in itself, however, is hardly the frame of mind one looks for in someone giving assurances and purporting to lead society’s attitudes” (p. 67). For White, the reference to this fable retrospectively casts doubt on Mrs. Elton’s “claim that her brother-in-law ‘was always rather a friend to the abolition’”: “In the case of both Emma and Mrs Elton we have seen that being a friend can involve making blunders and injuring the interests of the person purportedly being helped” (p. 67).

Lesbi-Honest

Tiffany Potter argues that a “tone of sexual tension, often unrecognized in the Emma-Jane relationship even when noted in Emma’s friendship with Harriet,” runs throughout the novel and culminates in this scene:

Although early in the novel Emma huffs, “I must be more in want of a friend, or an agreeable companion, than I have yet been, to take the trouble of conquering any body’s reserve to procure one. Intimacy between Miss Fairfax and me is quite out of the question” [vol. 2, ch. 6 [24]; p. 132], she does indeed set out to “conquer” Jane to gain a “companion” capable of “intimacy”: “It was a more pressing concern to show attention to Jane Fairfax . . . and with Emma it was grown into a first wish […]” [vol. 3, ch. 9 [45]; p. 255]. Even more tellingly, Emma’s language in reference to Jane soon becomes very much like the terms she earlier used to describe her attraction to Harriet. Her desire is demonstrated in that “she was longing to see her” [p. 297] and refers to her as looking “so well, Emma tells the blushing Jane, “Had you not been surrounded by other friends, I might have been tempted to introduce a subject, to ask questions, to speak more openly than might have been strictly correct. — I feel that I should certainly have been impertinent” [p. 302]. Jane’s response that she “had always a part to act” [ibid.] appears to refer, as do Emma’s suggestions, simply to Jane’s clandestine engagement to Frank Churchill. Once again, however, the homoerotic undertone perceived by the reader is clear and must be considered to understand the full sexual and social implications of Austen’s work. (pp. 192–3)

Potter argues that “[s]upport for the existence of this tone […] can be drawn from some helpful comparisons between the discourse of women in Lister’s I Know my own Heart and in Emma’s final conversation with Jane”; for example, “the repeated use of Emma’s chosen word ‘impertinent’ in Lister, where the word is always used in a flirtatious or sexually suggestive context between pairs of women” (p. 193). The relationship, however, seems doomed to non-consummation:

Yet the obvious attraction between the two women never moves beyond the most cursory of female relationships during the novel, and there is no indication that anything more will develop after the heroines’ respective marriages […]. Until the end of the novel, Emma posits her attraction as jealousy and dislike. She is jealous of Jane Fairfax in much the same way that Mr. Knightley is jealous of Frank Churchill: each of the newcomers threatens the incumbent’s position as most desirable person of his or her gender. Thus, even after Emma eventually appears to come to terms with her attraction for Jane, the two women can never have a purely female relationship, since the compulsory heterosexuality and marriage dictated by their community has placed them in social competition. Both women are also, of course, being manipulated by Frank Churchill so that Emma sees the suggestion of Jane’s attractiveness to Mr. Knightley while Jane sees her fiancé flirting outrageously with Emma, his decoy, who, he in turn suggests, “never gave [him] the idea of a young woman likely to be attached” [vol. 3, ch. 14 [50]; p. 287], at least to a man. Ironically, it is Churchill’s perceptive recognition of Emma’s interest in relationships with women that prevents her from establishing one with Jane Fairfax. (p. 194)

Similary, Susan Korba writes that “Austen reserves the truly charged and sexually ambiguous moments for the reconciliation between Emma and Jane Fairfax”; the novel’s ending, with both Jane and Emma heterosexually paired off, represents a “denial of [Emma’s] sexuality” (p. 159).

Dark Mirrors

Many scholars point out that Jane Fairfax would have been a more typical choice of heroine than Emma Woodhouse. Susan Morgan writes:

In terms of fictional conventions, we would most expect Jane Fairfax to be the heroine of Emma. We know, on the unimpeachable authority of Emma’s jealousy, that Jane is elegant, accomplished, intelligent, and beautiful. Her charm is marred only by a reserve which turns out to be more than excusable because of the secret she has been suffering under. Jane comes from the external world, the big world of real events, to the idyllic isolation of Highbury. […] Jane is poor. She arrives in Highbury with real burdens, real conflicts, real feelings. Her situation is such that her acts, her decisions, and the acts of others unaware of her situation, will have real and lifelong consequences for her. Unlike anyone else, Jane is introduced at the moment of the crisis of her life—she is the person for whom internal attitudes have corresponding external effects, she is at the point where events will bring her permanent happiness or despair, and she has the superior intelligence and the emotional sensitivity to be aware of her situation.

[...] Emma has gone about making up her own heroine, even providing her with a series of romances. Harriet, after all, is a storybook girl: fair, sweet, and seventeen, with “those soft blue eyes and all those natural graces” (p. 23) and an unexplained past. Yet Jane is the dark realistic heroine whose history most fulfills Emma’s fancies, and Emma misses all the romantic intrigue that is actually going on. (pp. 40, 45)

Why, then, are Jane’s confidence and consciousness avoided throughout the course of the narrative? For Wayne Booth, avoiding Jane’s point of view is essential in allowing the reader to form sympathy for Emma:

Sympathy for Emma can be heightened by withholding inside views of others as well as by granting them of her. The author knew for example that it would be fatal to grant any extended inside view of Jane Fairfax. […] It is not only that the slightest glance inside Jane’s mind would be fatal to all of the author’s plans for mystification about Frank Churchill, though this is important. The major problem is that any extended view of her would reveal her as a more sympathetic person than Emma herself. (p. 100)

This does not, however, touch on why Emma must be the focal point for narrative and for sympathy. For Paul Fry, who argues that “[m]any rejected plots linger in the plot of Emma, as if pointing to their own unsuitability,” it is a matter of narrative ethos:

The pining away of the first Mrs. Weston, the death of Lieutenant Fairfax, and the pining away of his wife—these are Interpolated Tales summarily dismissed in matter-of-fact prose. They are tales not told precisely because they are “interesting” in Mr. Elton’s sense of the word, and from this sort of affectivism the narrator recoils with ironic disrelish: “Human nature is so well disposed towards those who are in interesting situations, that a young person, who either marries or dies, is sure to be kindly spoken of” [vol. 2, ch. 4 [22]; p. 116]. (p. 131)

“Jane Fairfax’s false choice, her decision for a secret engagement, forces her to appear in the attitude of a Heroine”; but “Romance” is something which the moral world of Emma dismisses as being akin to “[s]ham” (ibid.). Characters of “Lachrymose Interest” (such as the first Mrs. Weston) must remain “peripheral, on the border of things in space and time,” because “[t]o remain in Highbury is to belong to the main plot in ethos as well as in circumstance” (p. 133). Frank Churchill and Jane Fairfax, “for all the restitution the finale allows them, can never live in Highbury”; they are “threats against the cognitive property of the community,” and therefore subject to “banishment” (ibid.).

Indeed, abjuring the conventional choice of heroine—including her in the narrative, but in such a way as to flaunt her peripheral status and make her non-inclusion notable—seems a part of the narrative experiment of Emma. Elizabeth Sabiston writes that Emma is “highly experimental”; before George Eliot or Henry James, Jane Austen “conceived the notion of dispensing with plot and creating a heroine so vital, irrepressible and imaginative that the entire novel comprises the dialectic of her limited point of view and Austen’s discreet, subtle corrections” (p. 139).1

Footnotes

On Emma as experimental see also Mullan (2015).

Discussion Questions

What gives this section its emotional register? How is the reader ‘meant’ to feel upon Emma and Jane’s reconciliation?

What is the point of Mrs. Elton’s (mis)quotation? Is it merely a jibe at her pretensions to literariness, or does it have further-reaching implications on the presentation of friendship in Emma? Is it an intentional insult on Mrs. Elton’s part?

Why has Austen steered clear of the most typical subjects for novels and romances in Emma?

Bibliography

Austen, Jane. Emma (Norton Critical Edition). 3rd ed. Ed. Stephen M. Parrish. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, [1815] 2000.

Korba, Susan M. “‘Improper and Dangerous Distinctions’: Female Relationships and Erotic Domination in Emma,” Studies in the Novel 29.2 (1997), pp. 139–63.

Morgan, Susan J. “Emma Woodhouse and the Charms of Imagination.” Studies in the Novel 7.1 (Spring 1975), pp. 33–48.

Mullan, John. “How Jane Austen’s Emma Changed the Course of Fiction.” The Guardian (5 December 2015).

Potter, Tiffany F. “‘A Low but Very Feeling Tone’: The Lesbian Continuum and Power Relations in Jane Austen’s Emma.” English Studies in Canada 20.2 (June 1994), pp. 187-203. DOI: 10.1353/esc.1994.0034.

Sabiston, Elizabeth Jean. The Prison of Womanhood: Four Provincial Heroines in Nineteenth-Century Fiction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1987.

Steele, Kathleen. “‘Even Miss Bates Has a Mind’: A Cognitive Historicist Reading of Emma’s Miss Bates.” Persuasions On-Line 39.1 (2018).

Tandon, Bharat. “The Literary Context.” In The Cambridge Companion to Emma, ed. Peter Sabor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2015), pp. 17–35.

White, Gabrielle D.V. “Emma: Autonomy and Abolition.” In Jane Austen in the Context of Abolition: ‘A Fling at the Slave Trade’. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan (2006), pp. 52–72. DOI: 10.1057/9780230506138_3.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watch my days of mercy online free

WATCH MY DAYS OF MERCY ONLINE FREE HOW TO

WATCH MY DAYS OF MERCY ONLINE FREE DRIVER

so which movies COULD she be talking about? Marilyn Monroe biopic star Ana De Armas slams NC-17 rating from Netflix and says other films on streaming giant are 'more explicit'. Venice Film Festival 2022: Georgina Rodriguez puts on a VERY leggy display in a backless black dress with a daring thigh-high split

WATCH MY DAYS OF MERCY ONLINE FREE DRIVER

Pure feel-good escapism! From George Clooney and Julia Roberts to hilarious dialogue and a stunning setting, here's why we're all going to LOVE hit new comedy Ticket to Paradiseįormula 1 driver Lando Norris splits from model girlfriend Luisinha Oliveira - just two weeks after their romantic trip to Ibiza while Daddy finishes work! Carrie Johnson takes son Wilfred to wildlife park as Boris spends his last days as PM Rocket Maaaan! David Walliams delights pals Elizabeth Hurley and Elton John as he leaps off yacht into the water in the South of France Olivia Wilde pictured for the first time after tension exposed on the set of her Don't Worry Darling as she wears crop top in LA

WATCH MY DAYS OF MERCY ONLINE FREE HOW TO

Love Island's Amber Gill looks in high spirits as she dons a tiny bikini and sips on cocktails during a boozy Mykonos boat trip after her 'coming out' tweetĬost of living on your mind? Here's how to take control of your money and make it work for you 'It's very peculiar': Melinda Messenger, 51, hits back at 'anti-ageing' reaction to snap of her natural grey hair after she ditched her trademark blonde locks Moment shirtless Tommy Fury 'swings punches at his brother Roman as a man stands between them in raucous 4am fight' on Manchester night out Venice Film Festival 2022: Cate Blanchett turns heads in a velvet jumpsuit while Julianne Moore takes the plunge in a VERY low-cut black gown at the Tár premiere South African Lion King composer 'does not remember' discussing Nelson Mandela with Meghan Markle at Lion King premiere The song was recorded as a new take on his 1971 classic hit, Tiny Dancer. She has since teamed up with Elton John to release her first song since the end of her legal arrangement - a track called Hold Me Closer. Spears regained control of her life last November after her 13-year conservatorship was terminated. In the shot, which she later deleted, Spears donned a long-sleeved floral top with white shorts and sunglasses with white rims. !!!' as she was also pictured Monday posing in a garage alongside an electric bike. Spears later updated the caption, writing, 'Psss found my bike y'all. 'And my one outing a week to therapy driving 20 mph to get there… life goes on … not a big deal AT ALL … I mean AT ALL !!! Just want to send my love and remembrance to those who cleverly TOOK CARE OF ME BUT ALSO HAD ME IN A CHAIR WORKING FOR THEM for 10 hours a mother f**king day !!! I’m just saying … stay gold folks !!! It’s a s**t race people !!! Life comes fast if and if you don’t move fast, you might just miss it !!!' "Sensitively etched by Ellen Page (now Elliot Page) and Kate Mara.Smiling: Spears was also pictured Monday posing in a garage alongside an electric bike, as she donned a long-sleeved floral top with white shorts and sunglasses with white rims Can Lucy and Mercy overcome their intense differences, or will these differences consume them? But eventually Lucy must confess her reasons for getting involved in the cause: her own father was convicted of murder and now waits on death row. Their relationship grows from hostility to curiosity to intense, physical passion. Lucy and Mercy could be bitter enemies, yet they share an undeniable connection. Mercy is there to celebrate justice served. At one such event, Lucy spots Mercy, daughter of a police officer whose partner was killed by a man about to receive a lethal injection. Sisters Lucy and Martha Morrow are regular attendees at state executions across the Midwest, where they demonstrate in favor of abolishing the death penalty.

0 notes

Photo

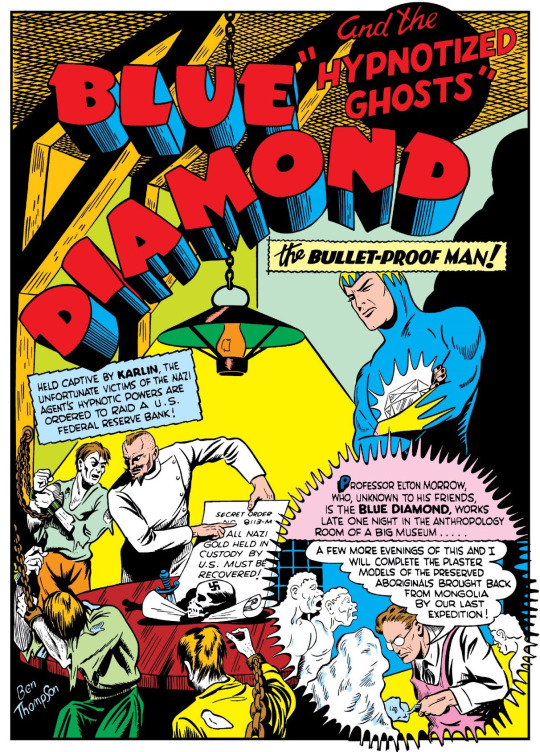

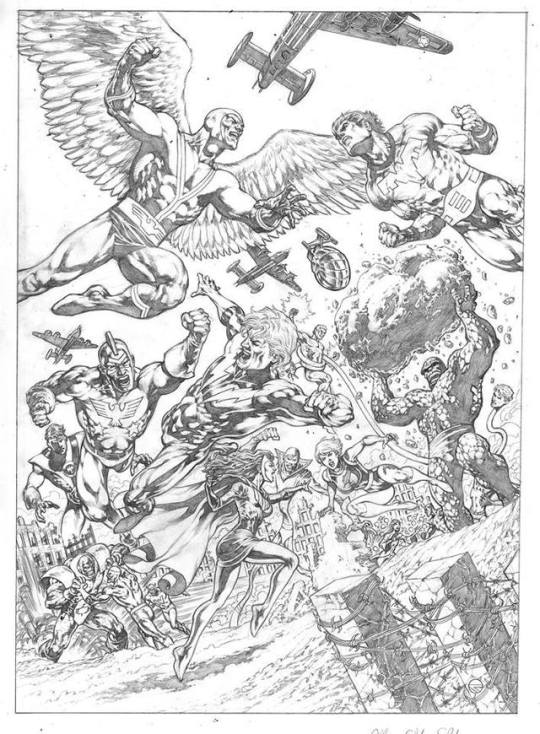

There’s a story with this latest commission I have from Allan Goldman...

Our story opens with the FF’s ever-lovin' blue-eyed Thing having traveled back in time to the year 1942 to prevent the Nazi's from taking advantage of one half of a cylinder of Vibranium that was accidentally sent back in time and teaming up with the Liberty Legion (see Marvel Two-In-One Annual Vol 1 1, Jun ‘76). The Liberty Legion consists of the Whizzer, Miss America, Patriot, Thin Man. Jack Frost, Red Raven and Blue Diamond. But this has caused a time anomaly to occur and triggered an alarm on the Mission Monitor Board of the Legion of Super-Heroes in the 30th Century.

Brainiac 5 was on monitor duty at the time and realizes that this could alter the time stream and cause the Legion to have never been formed. Fearing the worst, Brainiac 5 assembles a team go back in time to prevent this from happening. He has the following: Quislet, Chameleon Boy, Light Lass, Ultra Boy, White Witch, Lightning Lad, Blok, Colossal Boy and Legion Reservist Jimmy Olsen as Elastic Lad report and take a Time Bubble back in Earth’s history to the year 1942 to investigate. Unbeknownst to neither Brainiac 5 nor the Legionnaires assigned this was a trick of the Time Trapper. They have been sent to an alternate dimension, the Marvel 616 Universe, hoping for their demise. Of course when two super powered teams who have never met before and assume the other is the enemy meet for the first time the result is…

Legion vs Legion!!!

#Allan Goldman#Art Commission#commissioned art#Liberty Legion#The Whizzer#Whizzer#Robert Frank#Avengers#Invaders#All-Winners Squad#Miss America#Madeline Joyce#Red Raven#Sky Island#Jack Frost#Blue Diamond#Elton T Morrow#Crazy Sues#Lifestone Tree#Patriot#Jeffrey Mace#Daily Bugle#Captain America#Thin Man#Bruce Dickson#New Invaders#Kalahia#The Thing#Thing#Ben Grimm

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

for the music lover:

Hello!

This is a blog I will be writing as I discover new (and old) music. If you like discovering music, like reading random people’s thoughts, or just like following people for no reason, feel free to follow this blog!

Below are some albums I’ve already listened too, albums I plan too listen to (which is a list that is always growing) and a bit of information about me.

Here are some albums I have listened too already, as well as the ratings I have given them:

Marvin Gaye What's Going On (9/10)

The Beach Boys Pet Sounds (9/10)

Childish Gambino Awaken, My Love! (9/10)

Sufjan Stevens Carrie & Lowell (9/10)

Talking Heads Remain In Light (9.5/10)

Kendrick Lamar good kid m.A.A.d city (8/10)

Bob Dylan Highway 61 Revisited (8/10)

Frank Ocean Blonde (8/10)

Bon Iver 22, A Million (8/10)

Kendrick Lamar untitled unmastered (8/10)

Kanye West 808s and Heartbreak (8.5/10)

A Tribe Called Quest We Got It From Here… (8.5/10)

Kanye West My Beautiful Dark Twisted… (7.5/10)

Born Joy Dead Stones In My Shoe EP (7.5/10)

Childish Gambino because the internet (6/10)

George Harrison All Things Must Pass (6.5/10)

Kanye West The Life of Pablo (5/10)

Arcade Fire Funeral (5/10)

Metallica Hardwired…To Self Destruct (4/10)

CRX New Skin (3/10)

Neutral Milk Hotel In An Aeroplane Over The Sea (3.5/10)

And here are some albums I plan to listen too in the near future:

The Velvet Underground The Velvet Underground & Nico

The Clash London Calling

The Pixies Dolittle

Bob Dylan Blonde on Blonde

David Crosby Lighthouse

The Smiths The Queen Is Dead

The Doors s/t

U2 The Joshua Tree

Television Marquee Moon

Sigur Ros Ágætis Byrjun

Sigur Ros Kveikur

David Lee Roth Skyscraper

Elliott Smith From A Basement On The Hill

Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds Skeleton Tree

Lady Gaga Joanne

Chance the Rapper Coloring Book

Bon Iver Bon Iver

Kemba Negus

Kimbra The Golden Echo

U2 Achtung Baby

U2 All That You Can’t Leave Behind

Eminem The Eminem Show

Elton John Honky Chateau

Frank Ocean channel ORANGE

David Bowie Low

The 1975 The 1975

Maroon 5 Songs About Jane

The Shins Port of Morrow

Catfish and The Bottlemen The Ride

As for why my opinion is one that even matters...I’m an 18 year old musician (I play drums and sing in my band, but I also play guitar, bass and keys). I have been playing music since I was around 5, and I have recently decided ignoring the wealth of music I have access too is really dumb. So here I am!

If you got through all of that, you’re pretty cool. Thanks for reading!

0 notes

Text

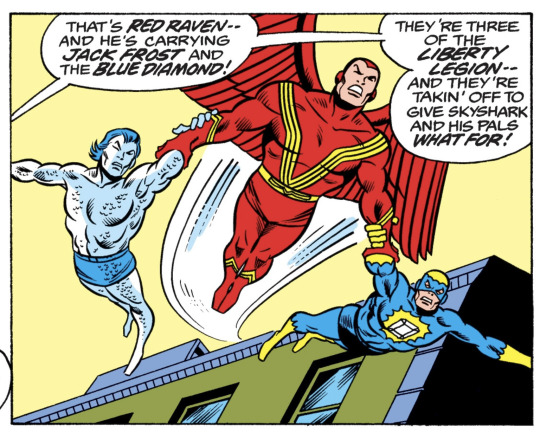

They’re three of the Liberty Legion

#marvel two-in-one#liberty legion#red raven#jack frost#blue diamond#Elton T. Morrow#sky shark#time travel#world war two#team up#roy thomas#sal buscema#marvel comics#comics#70s comics#bronze age comics#the red raven#the Liberty legion

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

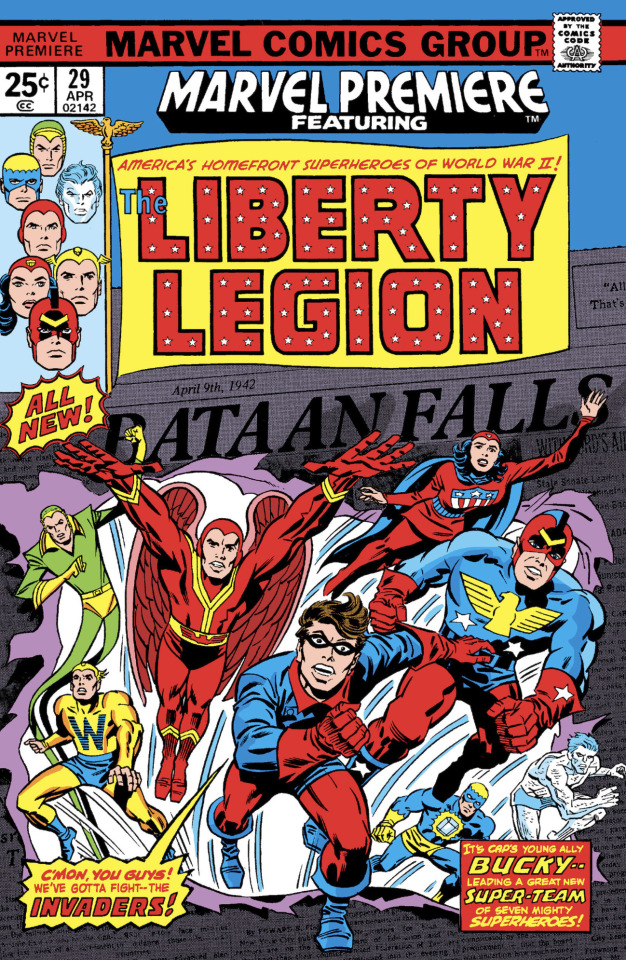

Marvel Premiere #29

#marvel premiere#the Liberty legion#bucky#james buchanan bucky barnes#the patriot#jeffrey mace#the blue diamond#Elton t. morrow#the whizzer#Robert l. frank#miss america#Madeline Joyce#the thin man#bruce Dickson#the red raven#jack frost#world war two#jack kirby#marvel comics#comics#70s comics#bronze age comics

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marvel Premiere #30

#marvel premiere#the invaders#the Liberty legion#the red skull#captain america#steve rogers#namor mckenzie#namor#namor the sub mariner#prince namor#the blue diamond#Elton t. morrow#jack frost#the patriot#jeffrey mace#miss america#Madeline Joyce#the thin man#the red raven#the whizzer#Robert l. frank#bruce Dickson#world war two#jack kirby#comics#marvel comics#70s comics#bronze age comics

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

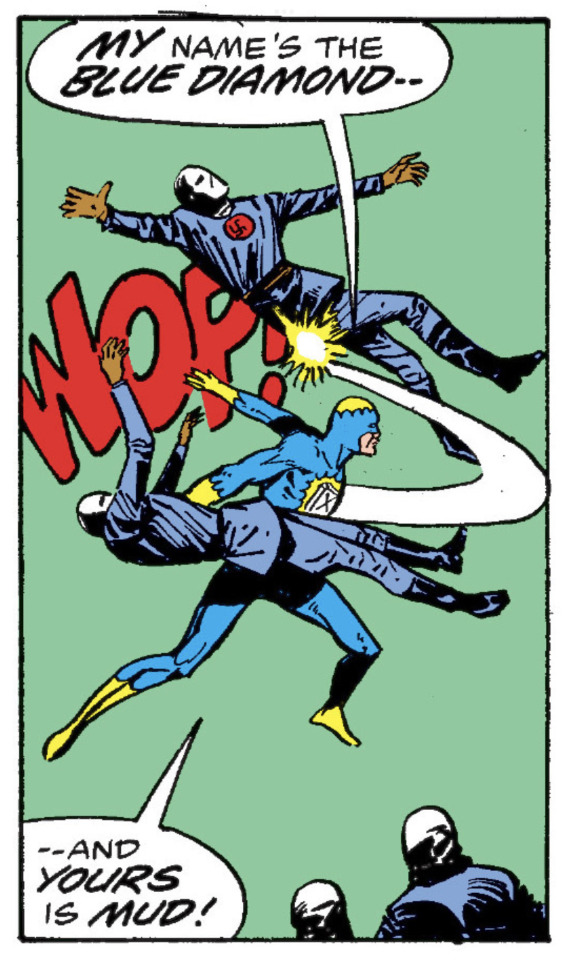

Let’s see if I can remember my tough-guy lines…

#marvel premiere#the Liberty legion#the blue diamond#Elton t. morrow#tough guy#reveal#nazis#world war two#roy thomas#don heck#marvel comics#comics#70s comics#bronze age comics

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

And we’re not quittin’ ‘till the sign of the swastika—falls before this living V for victory—the Liberty Legion!

#the invaders#the Liberty legion#bucky#james buchanan bucky barnes#the blue diamond#Elton t. morrow#the patriot#jeffrey mace#miss america#Madeline Joyce#the thin man#Bruce Dickson#the red raven#the whizzer#Robert l. frank#jack frost#first appearance#world war two#Nazis#swastika#roy thomas#frank robbins#marvel comics#comics#70s comics#bronze age comics

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

My name’s the Blue Diamond

#marvel premiere#the Liberty legion#the blue diamond#Elton t. morrow#your name is mud#uh oh#world war two#roy thomas#don heck#marvel comics#comics#70s comics#bronze age comics#nazis

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saturday, 25th December (Christmas Day): The weather is not favourable

Read and comment on WordPress

Read: Vol. 1, ch. 16; pp. 90–91 (“Emma got up on the morrow” through to “a most honourable prisoner”).

Context

Emma wakes determined to be cheerful. The party at Hartfield is detained from attending church services by the weather.

Readings and Interpretations

Very Cheering Thoughts

Roger Gard reads Emma’s “[getting] up on the morrow more disposed for comfort than she had gone to bed” as a discouraging sign after her “first long, important day of self-accusation”: “This is a small, partial, aganorisis, or recognition, including a small newly acknowledged sense of Mr. Knightley’s wisdom. But it is swiftly recovered from and ignored in a new morning and with the alacrity of youthful spirits bolstered by her intuition of Elton’s not really being in love” (p. 163). Similarly, Edgar Shannon reads this as evidence that Emma’s “complacence has been pricked, but the lesson has not been assimilated” (p. 639).

Everything in its Season

Lionel Trilling, interpreting the world of Highbury as the world of the idyll (a non-realist genre that presents humanity in a state of innocence and harmony), writes that “[t]he weather plays a great part in Emma: in no other novel of Jane Austen’s is the succession of the seasons, and cold and heat, of such consequence, as if to make the point which the pastoral idyll characteristically makes, that the only hardships that man should properly endure are meteorological” (p. 57).

Indeed, the weather has been gradually encroaching throughout the first volume, achieving a larger and larger narrative presence with the intrusion of winter into the activities of the characters. During the fall, considerations of weather are mentioned only to be dismissed (“‘Dirty, sir! Look at my shoes. Not a speck on them’”; vol. 1, ch. 1; p. 4) or as distractions from other topics (“‘What does Weston think of the weather; shall we have rain?’”; vol. 1, ch. 5; p. 25). Weather is mentioned in its threatening capacity to prevent outdoor activity, at least for Emma and Harriet, in late fall (“Though now the middle of December, there had yet been no weather to prevent the young ladies from tolerably regular exercise”; vol. 1, ch. 10; p. 54). The debacle of the snow at the Randalls dinner in early winter culminates now in the fulfillment of that threat.

Shannon mentions the mood created by the inclement weather during and after Elton’s proposal: “His insincere, fruitless proposal vents itself not only in the confined dark of the carriage but on a bleak, snowy December night. Darkness, coldness, and confinement reflect the unpropitiousness and, for Emma, the distastefulness of the incident.” But the implications here may be deeper than setting a mood, or contriving something convenient for the sake of the plot. Paul H. Fry mentions “the seasonal quality of Georgic” (a genre involving “the teaching of useful and sociable skills against the backdrop of a farm”) in Emma—”that is, the fitness of things in season” (pp. 141, 129). If, as Shannon writes, the “novelist parallels increasing social activity [in volumes 2 and 3] with the advancing seasons conducive to it in a rural community,” then it seems fitting that the poor “sociable skills” revealed by the failed social connection between Emma and Mr. Elton come to a head during a time when physical motion as well is threatened and then disallowed.1

Filial Duty

I am also interested in how Emma in this section turns Mr. Woodhouse’s fretfulness to account, or at least coincidentally benefits from it: “Mr. Woodhouse would have been miserable had his daughter attempted [going to church], and she was therefore safe from either exciting or receiving unpleasant and most unsuitable ideas” (vol. 1, ch. 16; p. 91).

Laura Mooneyham implies that Emma’s isolation in deference to her father may be self-imposed: she proposes “Emma and her father enjoy a symbiotic relationship” that

makes Emma’s love for her father a less than selfless proposition. Significantly, each major crisis precipitated by Emma’s errors of imagination is followed by a period of retreat to the changeless and deathlike safety of her father’s company. After the debacle of Mr. Elton’s proposal, the bad weather aids Emma in this retreat […]. (p. 110)

Footnotes

On the sequence of the seasons in Emma see also Kaufmann (pp. 55–70); Stovel (n.p.).

Discussion Questions

Does Emma’s relative cheerfulness upon waking indicate youth and optimism, or a failure to learn a lesson?

To what narrative or thematic purposes is weather put throughout Emma?

Bibliography

Austen, Jane. Emma (Norton Critical Edition). 3rd ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, [1815] 2000.

Fry, George. “Georgic Comedy: The Fictive Territory of Jane Austen’s Emma.” Studies in the Novel 11.2 (Summer 1979), pp. 129–46.

Gard, Roger. “Emma’s Choices.” In Jane Austen’s Novels: The Art of Clarity. Avon: Yale University Press (1992), pp. 155–81.

Kaufmann, Ruta Baublyté. “Changing Seasons: The Cyclical and the Linear.” In The Architecture of Space-Time in the Novels of Jane Austen. Palgrave Macmillan (2018), pp. 19–79. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-90011-7_2.

Mooneyham, Laura G. “The Double Education of Emma.” In Romance, Language and Education in Jane Austen’s Novels. Houndmills: Macmillan Press (1988), pp. 107–145.

Shannon, Edgar F. “Emma: Character and Construction.” PMLA 71.4 (September 1956), pp. 637–50. DOI:10.2307/460635.

Stovel, Bruce. “The New Emma in Emma.” Persuasions On-Line 28.1 (Winter 2007).

20 notes

·

View notes