#Taiaiake Alfred

Text

0 notes

Quote

From the perspective of the state, marginal losses of control are the trade-off for the ultimate preservation of the framework of dominance.

Taiaiake Alfred, Peace, Power, and Righteousness, p. 71

#Taiaiake Alfred#Peace power and Righteousness#reading#books#bookworm#book quotes#the state#Framework of dominance

1 note

·

View note

Text

Nearly fifty years ago, Congress extinguished Alaska Native tribal autonomy over hunting and fishing through a land claims settlement. In the past five years, the position of Kuskokwim River tribes in relation to the federal government has advanced through the establishment of the Kuskokwim River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (KRITFC) and the formalization of a “co-management” partnership between tribes and the USFWS. [...] While, by many accounts, the formalization of a “collaborative” partnership between KRITFC tribes and the USFWS marked an important step taken toward Alaska Native self-determination, this relationship has not translated to greater tribal autonomy. Alaska Native tribes still cannot adjudicate on matters related to fish [...].

In recent years, subsistence fishing for Chinook salmon has been restricted under federal management to sporadic temporal allotments -- typically six-, twelve-, or twenty-four-hours in length. While both the USFWS and the KRITFC manage for “escapement” -- for a specific number of salmon to return to their spawning grounds each year -- with the stated goal of sustaining the Chinook salmon population, this management strategy is hardly unified. [...]

Each tribes’ allocation of Chinook salmon would account for escapement goals, and fishing would not be limited to sporadic blocks of time. When I asked people why federal fishery managers are resistant to implementing an allocation system, people explained the issue as one of trust: “They don’t think we can count our own fish.”

This lack of trust is thinly veiled, perhaps, when federal fishery managers make overtures of incorporating Indigenous “traditional knowledge” into management decisions. Indigenous knowledge about salmon is often represented as if using it to inform management decisions embodies Indigenous self-determination. But “Indigenous thought is not just about social relations and philosophical anecdotes,” as Métis feminist scholar Zoe Todd [...] writes.

In short, “cherry-picking” Indigenous thought is a hollow form of recognition that falls short of honoring tribal sovereignty. [...]

People in Naknaq know this: often, as a fishing partner would motor his boat away from the village to his traditional fishing grounds during a fishing opener, he would proclaim, cynically, “See! I’m exercising my sovereignty!”

There is a sense in which, if one must announce one’s sovereignty, it is not really sovereignty.

Despite the making of a “co-management” agreement between KRITFC tribes and the USFWS, the management partnership has, thus far, revealed how [...], drawing upon Mohawk political scientist Taiaiake Alfred and Anishinaabe feminist scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, “contemporary colonialism works through rather than entirely against freedom.” Kuskokwim River tribes have good reason to believe that the federal government continues to conceive of Indigenous peoples’ relationships with Chinook salmon as threats not only to the survival of Chinook salmon, to say nothing of the survival of the settler economies that depend on salmon, but also to the very legitimacy of federal management itself.

---

William Voinot-Baron. “Inescapable Temporalities: Chinook Salmon and the Non-Sovereignty of Co-Management in Southwest Alaska.” July 2019.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

just so you know, that canadian quote is kinda wrong it's actually kanata + satien = kanatiens not kehne ian according to taiaiake alfred (a mohawk professor) so same meaning just different words

Oh okay! Thank you!

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Taiaiake Alfred and I #wearewarriors #waw2019 #csfs #keepingupwithkia #amplife (at Prince George, British Columbia) https://www.instagram.com/p/Bvz2Z0Zh3QE/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=ljex7m5h36pm

0 notes

Text

My 15 favorite books

I made a Top 15 of my favorite books and explained why. They are listed as they came to my mind.

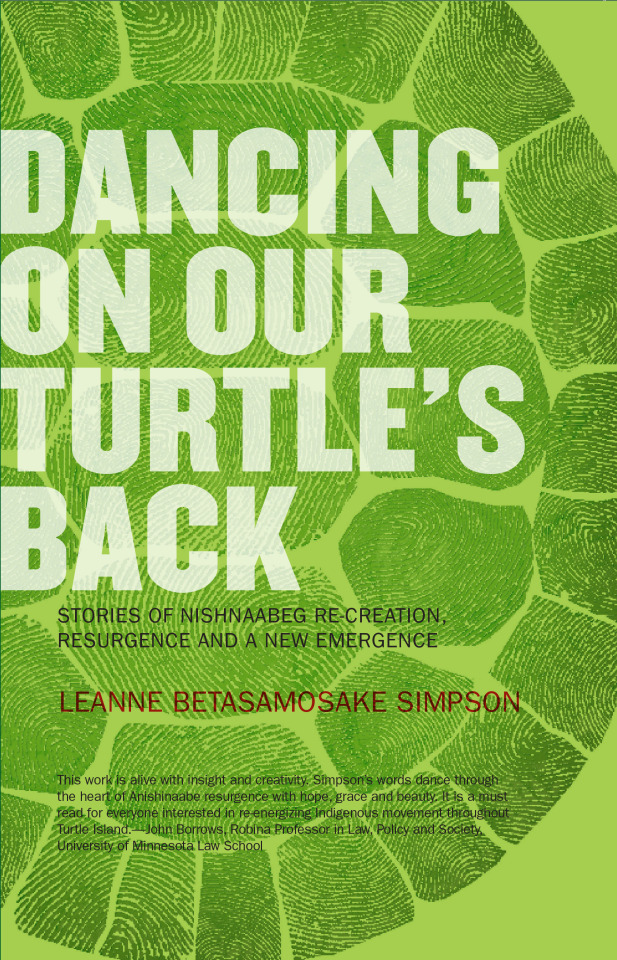

1. Dancing on our Turtle's Back (Leanne Simpson, 2011)

With this book, Leanne Simpson shows a path towards an Indigenous resurgence. She does it by exploring the philosophical thoughts and sociopolitical theories of her people, for instance, through the study of the etymology and epistemology behind words, intergenerational meanings associated with Creation stories and systems of governance such as breastfeeding as a treaty, that I quoted in my earlier post Allaiter, un acte de résurgence. This book got me into thinking about how can we (e.g. Les Québécois) resurge? How are we infected by colonialism? How do we clean ourselves from it? How do we update and live our ancestors’ ways of seeing and being in the world? This is the reason why I started to focus more on my positionality and on my own family story. It’s something I’ve been reflecting on after reading the impacting article Decolonization is not a metaphor and Vine Deloria Jr’s Custer Died for your Sins.

2. A People's History of the United States [Une Histoire Populaire des États-Unis] (Howard Zinn, 1980)

Take a look at this video, and you’ll get why it came right away. It’s inspiring as it exposes the development of settler colonialism and imperialism in the US.

youtube

I simultaneously read Zinn’s short autobiography You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times. He is such an inspiration for me as a person, as an engaged researcher, an organic professor, and a militant.

3. Les Damnés de la Terre [The Wretched of the Earth, Los condenados de la tierra] (Frantz Fanon, 1961)

I highly recommend this book to activists and engaged researchers. He’s the heart of national liberation or decolonizing thinking. Frantz Fanon is a psychiatrist from Martinique who participated in the National Liberation Front of Algeria at the of the 1950′s. He died from Leukemia in 1961. He left a great legacy as an analyst of the pervasive grips of colonialism on our minds and of its traps as it intertwines with nationalism (fabricated by the national bourgeoisie). He also exposes results from his work with patients who’s colonial violence experiences are reflected in their tensed and muscular dreams. If there is something i always recall from that book, is that according to Fanon, you see people’s decolonization as they recreate themselves, through arts for instance. I see it as the beginning of the resurgence process. Like me, Fanon was very skeptical of the uses of history in national liberation processes.

4. Settler Sovereignty (Lisa Ford, 2010)

Comparing “settler colonialism” in Georgia and New South Wales, Lisa Ford reflects on how settlers (I would also say colonizers) consolidate their sovereignty on the Indigenous lands and peoples through state building. It’s close to what I have been researching in Uruguay by putting together colonialism, capitalism, and nationalism.

5. Red Skin, White Mask (Glenn Coulthard, 2014)

I have to say I was first attracted by the title but was rapidly aligned with Coulthard. In his work, he focuses on colonialism and capitalism as interdependent socioeconomic phenomenon. He also takes a look at the “Identity Politics” in Canada by exploring the relationships between his people, the Diné, and the government of Canada.

6. Peau noire, masque blanc [Black Skin White Masks, Piel negra, máscara blanca] (Frantz Fanon, 1952)

Here Fanon explores how colonial thought influences relationships, intimacy and interbreeding among people who’s gender and skin color vary. He takes his own experiences in Martinique as a sample, then in France as he was studying to become a psychiatrist. He suddenly realized how Black people were “surdéterminés de l’extérieur” (”overdetermination from the outside”).

7. The Autobiography of Malcolm X [L'autobiographie de Malcolm X] (1992)

Malcolm X or Malek El-Shabazz deeply impacted the Black Power Movement with its incisive critiques of US colonialism, racism, and imperialism. He made me conscious of the importance to be open-minded and humble so to change my perspectives and ways of being since it is necessary for becoming “righteous” or coherent with our vision of the world. I like X because he not only puts emphasis on decolonization as a public struggle but also as an inner collective and personal process.

8. Thérèse Raquin (Émile Zola, 1867)

It’s funny how we sometimes refuse to do something because we “have to”, no? We’ll I’m a bit like that. I had to read this book in College (Cégep) in a Literature class, but only read it completely years later. Zola impulses naturalism as a literary movement. He not only shows how the ambiance is or feels like but also how people’s mind is distorted and what they are willing to do for freedom and love. I can re-read this book on and on.

9. The Dispossessed [Les Dépossédés, Los desposeÃdos] (Ursula K. Le Guin, 1974)

I was introduced to Le Guin at the ls Librairie lâInsoumise, an anarchist bookstore on Saint-Laurent in Montréal. I was looking for a political science fiction book. In The Dispossessed, she shows us what an anarchist setting could look like and she sometimes highlights it through its interaction with a capitalist one. Sheâll make you dream and think of âdecolonial loveâ, relationships and knowledge. This is the kind of book that impacts your political walk of life, how you will, later on, deal with decision making and relationships.

10. The Caves of Steel [Les Cavernes d'acier, Las bóvedas de acero] (Isaac Asimov, 1954)

Asimov and his série Foundation is about human relationships with robots. The Caves of Steel is about the necessary filiation of a human from the earth and a robot detective to investigate the murder of a detective on a planet where professionals once got to migrate in order to save their lives. I like this book because he made me think of our relationships with technological developments and to go beyond appearance.

11. Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation (Silvia Federici, 2004)

I met Silvia Federici at the 2017 Anarchist Bookfair in Montréal. It was love at first sight. But I first got to know her through a Charrua friend who dug the relationships of Indigenous women and colonialism. Federici explores how capitalism separated men and women as a subaltern unit and dispossessed women from their political power in order to commodify land and work. To do this, she investigates witch hunting in Europe. It was quite relevant to me as most Charrua women I met during my fieldwork were descendants of midwives and healers... and I descend from voodoo and tarot practitioners. Her work associates well with the Indigenous feminism movement and its stance on colonial traditionalism.

youtube

12. Wasáse. Indigenous Pathways of Action and Freedom (Taiaiake Alfred, 2005)

Alfred introduced me with Peace, Power, and Righteousness to the Indigenous resurgence movement and how to contribute as an âorganic intellectualâ to remove consent to the system that oppresses us. I like Wasáse, the warriorâs dance because it offers us a path to a resurgence that works through cleaning our inner self, reconsolidating relationships within our collective and confronting oppressive external powers according to our own philosophical principles and as a political unity. Itâs quite similar to what Malcolm X was advocating for. Alfred does so by exploring individualsâ path to resurgence and the possibilities of being autonomous towards colonial powers.

13. Los dones étnicos de la Nación (Diego Escolar, 2007)

This one can to my mind because Escolar shows how settler colonialism and nationalism affect our settler and Indigenous minds in seeing and living an Indigenous present.Escolar does so by exposing Indigenous oral histories and settler colonial archives in the light of the return of supposed Indigenous extinct groups in Argentina.

14. Roots of Resistance. A history of Land Tenure in New Mexico (Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, 1980)

This is a brilliant book if you want to know the history of the south of the United States, you know where Trump is building his fence. Dunbar-Ortiz looks at an Indigenous territory that has been colonized by multiple interests and empires through time and how its Indigenous peoples were used to protect foreign sovereignties, but also how they resisted to colonialism.

15. Little Red Book, Petit livre rouge, Libro Rojo] (Mao Tsedong, 1964)

I think Mao ended up here because I had the Black Panthers Party in mind. Iâm not a Maoist, but I am curious. This book, along with The Wretched of the Earth, put up the table for national liberation movements in the 1960â²s by advocating for an armed and cultural revolution. The 1960â²s are the golden era of activism.

#settler colonialism#frantz fanon#malcolm x#settler#sovereignty#zinn#united states#history#land tenure#indigenous#resurgence#decolonizing#decolonization#colonialism#colonization#literature#national libertion#nationalism#bourgeoisie#books#top 15#science fiction#anthropology#classic literature#classics#mao#maoism#realism#naturalism#revolution

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

At the confluence of colonialism and a "Big Two-Hearted River": a congruent path to recovery

At the confluence of colonialism and a “Big Two-Hearted River”: a congruent path to recovery

In “Big Two-Hearted River”, a story by Ernest Hemingway, Nick Adams hikes to a remote and isolated river and fishes it. The hike, the work to set up his camp, and the time spent fishing the river seems to restore him. The story ends on a positive note. There is work to be done on his path to recovery, but Adams seems to think he will manage it. I recently reread Hemingway’s first forty-nine short…

View On WordPress

#A Farewell to Arms#Big Two-Hearted River#Colonialism#Ernest Hemingway#Gerald Taiaiake Alfred#Movement#Nick Adams#Sterling Lynch#The Nick Adam Stories

0 notes

Text

WOAH

Haven’t been here in a while. (Who am I even writing this too?) I am doing well in life, I must say! I have #161 days of continuous clean and sober time. That is over five months; beating my first round of recovery - I believe that was 132 days? It’s hard getting back into the swing of university studies but I am trying at least. In Human Rights class, we are learning about water security. In my spare time, I am usually found reading books by Mohawk scholar, Taiaiake Alfred. He is a genius and I hope to someday meet him. He was at Carleton University last spring, so I am hoping that he comes back during my time here; however long that is. I highly recommend searching for his videos on Youtube about European colonization and Indigenous resurgence, especially if you want to know why Indigenous people are struggling socially; if you look him up, you’ll be able to defend us in conversation against the white settler-colonialists haters that be. Well, back to it. Lol. Why am I writing this?

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The white élite undertook to manufacture a Native élite. They picked promising youths, they made them drink the fire- water principles of capitalism and of Western culture; they educated the Indian out of them, and their heads were filled and their mouths were stuffed with smart-sounding hypocrisies, grand greedy words that stuck in their throats but which they spit out nonetheless. After a short stay in the university they were sent home to their reserves or unleashed in the cities, whitewashed. These walking lies had nothing to say to their brothers and sisters that did not sound false, ugly, and harmful; they only mimicked their masters. From buildings in Toronto, from Montréal, from Vancouver, businessmen would utter the words, 'Development! Progress!' and somewhere on a reserve lips would open '. . . opment! . . . gress!' The Natives were complacent and compliant; it was a rich time for the white élite.

Then things changed. The mouths of Natives started opening by themselves; brown voices still spoke of the whites’ law, democracy, and liberal humanism, but only to reproach them for their unfairness and inhumanity. White élites listened without displeasure to these polite statements of resentment and reproach, these pleas for reconciliation, with apparent satisfaction. “See? Just like we taught them, they are able to talk in proper English without the help of a priest or of an anthropologist. Just look at what we have made of the backward savages—they sound like lawyers!” Whites did not doubt that the Natives would accept their ideals, since the Natives accused the whites of not being faithful to them. Settlers could still believe in the sanctity of their divine civilizing mission; they had Europeanized the Natives, they had created a new kind of Native, the assimilated Aboriginal. The white élites took this all in and whispered, quiet between themselves over dinner, as good progressive persons of the (post)modern world: 'Let them cry and complain; it’s just therapy and worth the expense. It’s better than giving the land back!'

Taiaiake Alfred, ‘Forward’ in Glen Sean Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition

0 notes

Text

for its maker trusts in what has been made, though the product is only an idol that cannot speak

In late April and May, I had some tomatillos from the Port Credit Seed Library growing along side some Chadwick cherry tomato seedlings.

I hope to explore the history of these two plants some time in a post here, because they have a fascinating and somewhat intertwined history, and there’s quite an interesting story of global botanical exchanges behind the tomato itself, something that only arrived in Europe after Spanish colonizers encountered it in Latin America.

Anyways in May, I transplanted these sprouting friends of mine into an existing bed in my family’s backyard.

Not a proper vegetable bed, and not quite adequately spaced or exposed to sunlight, but hopefully a few of them will survive. I did not read extensively on best practices, nor did I follow the little that I did read, because I’m only borrowing space in a backyard that’s not really my own. Yet it’s not really my parents’ own either, in an important sense.

This process of transplanting seedlings into the land last month prompted me to think a little more about the history of this land. I often hear language along the lines of ‘look how far we’ve come’, as people discuss the vanishing of farmland in the areas surrounding my neighbourhood, because there is a very particular idea of progress presumed by most people who live where I live.

Machine as Metaphor

I last discussed on here Terry Eagleton’s suggestion that modernity’s ideology of progress does not know what to do with death, as death does not fit within its linear ‘upward’ narrative. Modernity’s fixation on ‘progress’ however is not only implicated in our collective repression of death, but also in the functioning of power and the way our species (particularly under ideologies like imperialism) asserts power over other species within the ecosystems we inhabit. Modernity is paradoxically emblematic of the sort of perverse romanticism that Haraway brought into doubt when she said the cyborg knows of no Edenic dust to return to. Wendell Berry’s “Unsettling of America” speaks of this attempt of modernity to recover Eden by way of the machine:

“having thus usurped the whole Chain of Being, conceiving itself, in effect, both creature and creator, humanity set itself a goal that in those circumstances was fairly predictable: it would make an Earthly Paradise. This projected Paradise was no longer that of legend: the lost garden… This new Paradise was to be invented and built by human intelligence and industry. And by machines. For the agent of our escape from our place in the order of Creation, and of our godlike ambition to make a Paradise, was the machine-not only as instrument, but even more powerfully as metaphor. Once, the governing human metaphor was pastoral or agricultural, and it clarified, and so preserved in human care, the natural cycles of birth, growth, death, and decay. But modern humanity's governing metaphor is that of the machine. Having placed ourselves in charge of Creation, we began to mechanize both the Creation itself and our conception of it. We began to see the whole Creation merely as raw material, to be transformed by machines into a manufactured Paradise.

And so the machine did away with mystery on the one hand and multiplicity on the other. The Modern World would respect the Creation only insofar as it could be used by humans. Henceforth, by definition, by principle, we would be unable to leave anything as it was. The usable would be used; the useless would be sacrificed in the use of something else. By means of the machine metaphor we have eliminated any fear or awe or reverence or humility or delight or joy that might have restrained us in our use of the world. We have indeed learned to act as if our sovereignty were unlimited and as if our intelligence were equal to the universe.”

Berry’s comments resemble the way Ivan Illich speaks of our addiction to machines and how it harbours within it an old addiction to slavery. Yet I find Berry here most resembling a theme that recurs a lot in various indigenous thought, particularly the intellectual Vine Deloria Jr’s work. Deloria, in a talk on Native American religious freedom said that:

“The vast majority of Indian tribes (and I don’t know off hand of any that would not hold this view), the vast majority knew, saw, felt, and experienced the universe as a living entity.

...And for thousands of years, living in the North American continent, traditional people, medicine people... were able to communicate with other forms of life, whether they were rocks, or trees, or birds, or other kinds of animals. They were able to communicate with areas of the land itself.

…Now our continent was invaded by your ancestors. A lot of them came over here seeking religious freedom, but they also came over here with a European form of the Michelangelo virus. And that was the belief that the universe operated like a machine. And that has proven immensely useful in science, but I’ve seen a great rebellion among the younger generation of scientists, that the analogy of the machine does not adequately describe the physical world. And if you treat the physical world as if it was a machine, from time to time it’s going to break down.”

Deloria, in “The Metaphysics of Modern Existence”, quotes Alvin Toffler in order to explain the prevalence of the machine as metaphor:

“we all learn from our environment, scanning it constantly—though perhaps unconsciously— for models to emulate. These models are... are, increasingly, machines. By their presence, we are subtly conditioned to think along certain lines. It has been observed for example, that the clock came along before the Newtonian image of the world as a great clocklike mechanism, a philosophical notion that has had the utmost impact on man’s intellectual development...Then we used the analogy of a clock to prove the presence of an absolute time within the universe, which was conceived to operate in the absolute manner we had been taught to expect.”

Deloria goes on to discuss Paul Tillich’s critique of the machine metaphor:

“Tillich suggested that the “man who transforms the world into a universal machine serving his purposes has to adapt himself to the laws of the machine. The mechanized world of things draws man into itself and makes him a cog, driven by the mechanical necessities of the whole. The personality that deprives nature of its power in order to elevate itself above it becomes a powerless part of its own creation.”

Or, in the words of Karl Barth (from Vol 3, Part 4 of his Church Dogmatics):

“the power that exceeds our real necessities of life, the power of technology — which basically has its own rationale and purpose, and which, in order to survive and be able to improve itself, must call forth ever new problems to solve — this had to become the monster that it largely is today, and ultimately, absurd though it is, it had to become a technology of disruption and destruction.”

So what is the problem that the institutions of power have constructed here in this land I live on now?

The Problem

Machines stand in for modern ideas of progress, because we have too often defined progress as the ability to increasingly instrumentalize the world around us, to increase its productivity according to the exclusive interest of ‘us’ humans, or more accurately humans with the most power in a ‘free’ market economy (i.e. humans with the most money).

The arrogant ideology of modernization is the same one that the indigenous intellectual Taiaiake Alfred references in his work. He believes Canada’s government policy regarding indigenous issues is perpetually misframed as a solution to a particular ‘problem’, that ‘problem’ being the lack of economic development in indigenous communities – a failure on the part of these communities to adequately ‘keep up’ with modern progress or to accommodate the liberal democratic state. This has historically been called the ‘Indian problem’.

An example: Duncan Campbell Scott was a bureaucrat in the Department of Indian Affairs for two decades (1913 to 1932), while also maintaining a reputable literary stature. Northrop Frye once wrote glowingly of Scott’s ability to write on subjects ranging from “a starving squaw baiting a fish-hook with her own flesh” to “the music of Debussy”. Frye, however, never mentioned how Scott, in many ways, perpetuated the ‘cultural genocide’ of indigenous communities. Scott once wrote:

“I want to get rid of the Indian Problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone… Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill.”

This aggressive integrationist model is behind all government policy that locates the problem of indigenous issues as one of ‘development’. This is a way the Canadian nation-state has acted as if it were God, and to make indigenous nations into its own image: ‘modernized’ and ‘developed’.

Taiaiake Alfred instead insists that Rosalee Tizya was right when she said the main issue and root problem is and has always been that indigenous land was stolen. The issue is not economic development nor even access to institutional state power. It was and is dispossession.

People Who Dwell at The Mouth of a Large River

Planting vegetables this summer, I am unavoidably planting vegetables on stolen land. Not only stolen, but also utterly ruined. The destruction of this land and its intricate ecological systems of interdependence was vital to its theft.

The the Anishinaabe academic, artist, and activist Leanne Simpson posed this question: “Why did my ancestors sign treaties after we lost the political power to have agency? They signed them because they were starving and they wanted me at the very least to be alive.”

Poverty in indigenous communities at the time of ‘treaty signing’ was not so much an issue of development, as much as it was about a tapestry of ecological connections that were torn apart, and a bounty of food that consequently disappeared. Survival and hunger (from a land stolen and destroyed) was the context of coercion that those treaties emerged from.

One of the most important food resources that disappeared in the 19th century was the abundance of salmon that once populated the area. In a footnote in “Dancing on our Turtle’s Back”, Leanne Simpson explains Mississauga’s etymology in this way:

“Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg means the Nishnaabeg people who live or dwell at the mouth of a large river. Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg Elder Doug Williams explained to me that this is the way his Elders referred to themselves. Peterborough, ON, October 26, 2010. This is similar to Basil Johnston's Mizhi-zaugeek, Anishinaubae Thesaurus, Michigan State University Press, East Lansing, MI, 2006, 14. Michi Saagiig or "Mizhi-zaugeek" people live at the eastern doorway of the Nishnaabeg nation, located in what is now known as eastern Ontario. According to Doug Williams, the word "Mississauga" is an anglicized version of Michi Saagiig or Mizhi-zaugeek.”

Leanne Simpson has also said that her people, the Michi Saagig, were salmon people. That was what they survived on. People have relied on the fish of the Missinihe river long before White settlers arrived. One of the most significant ‘pre-contact’ archaeological sites found in Mississauga (often called the Scott O’Brien site) is located around where the QEW highway intersects with the Missinihe (Credit River). The photo below (from “Mississauga: The First 10,0000 Years”) is a small sample of the 124 notched stone netsinkers found at the site, once used to catch fish in the Missinihe, back when the native species of salmon abundantly populated the river.

These netsinkers were found in two different caches on the site, one of them dating to the Middle Woodland period (~400 BCE to ~900 CE), conservatively over a thousand years old. People have evidently relied on the fish in the Missinihe for a long time, and within a century or two, these fish completely disappeared from the river.

What happened to the salmon? How did ‘the machine as metaphor’ shape the way 19th century White settlers treated the Missinihe river? And for what purposes and to what ends did they do so? Was it ‘worth it’? I hope to examine some of these questions in my next post here.

0 notes

Text

Indigenous Elitism

Within academia there’s been a rise in prominent Indigenous scholars, in particular Taiaiake Alfred, Glen Coulthard, Daniel Justice, and Leanne Simpson, the four horsemen (aka Indian Horsemen) of an intellectual apocalypse--drudging a teleological facade unimpeded by skeptical inquiry. Careers built on perpetuating a utopian decolonial occupation where inherent rights reign supreme. These delusional constructs defy any basis in reason, rationality, or logic and are fed to undergraduates as doctrine. The pedestal of Indigenous elitism must be obliterated with seasoned skepticism, their ideas buried in the existential graveyard with Jesus, Buddha, and Nanabush. This cadre of political academics tyrannizes the scope of Indigenous scholarship, idolizing a lost and forgotten cultural identity that no longer exists, the headdresses are gone and deer flaps aren’t in fashion.

These metaphorical connotations towards a complete decolonization is riddled with paradox. While I agree with Taiaiake’s criticisms against the settler-colonial stronghold on Indigenous soveriegnty (see Alfred & Tomkins 2011, pg.3), I disagree with the necessity that “...fishing, hunting, or picking medicines...”(Alfred & Tomkins 2011, pg. 15) is the proper initiation to Indigenous identity. A postmodern analysis of reality indicates a trend towards diversity in identity politics wherein outdated mechanisms of survival and passage are blasphemous. The Indian Horsemen’s feeble attempt to resuscitate tribal identities in bona fide fashion depicts sustained ignorance in the face of actuality.

0 notes

Quote

Its methods may have become more subtle and devious, but the state's goal is still clear: to assimilate Native people.

Taiaiake Alfred, Peace, Power, and Righteousness, p. 154

#Taiaiake Alfred#Peace power and Righteousness#reading#books#bookworm#book quotes#assimilation#Indigenous manifesto

0 notes

Text

book review: “Kanaka ʻōiwi methodologies : moʻolelo and metaphor” (part one)

Kanaka ʻōiwi methodologies, edited by Katrina-Ann R Kapāʻanaokalāokeola Nākoa Oliveira and Erin Kahunawaikaʻala Wright, is the fourth volume in the Hawaiʻinuiākea monograph series, a series produced by Hawaiʻinuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge:

The Hawaiʻinuiākea Monograph is the first publishing project under the new Hawaiʻinuiākea Publishing initiative. The peer-reviewed series, co-published with University of Hawaiʻi Press, is a venue for scholars, leaders–as well as practitioners–in the Hawaiian community.

rather than providing summaries and my opinions, i’ll instead be sharing some of the notes i made as i was reading each chapter.

Reproducing the Ropes of Resistance: Hawaiian Studies Methodologies by Noelani Goodyear-Ka’opua

this chapter begins with the following:

I am slyly

reproductive: ideas

books, history

politics, reproducing

the rope of resistance

for unborn generations.

by Haunani-Kay Trask, from her poem “Sons”

it also includes a quote from “the great physician, health researcher, and hawaiian independence advocate Lekuni Akana Blaisdell”: “Our ancestors are always with us as long as we think of them, talk to them, engage them in our thinking and planning and beliefs and actions.”

she writes a short history of the current resurgence of hawaiian studies - an important and valuable contribution.

the main section of this chapter sets out the “central commitments and lines of inquiry” of hawaiian studies:

lahui (collective identity and self-definition)

ea (sovereignty, leadership, breath, life, rising up, emergence)

kuleana (responsibility, privilege, obligations, positionality)

pono (balance, harmonious relationships, justice, and healing)

Goodyear-Ka’opua writes “Kanaka Maoli are defined by our ancestry. This is who we are. Hawaiian studies research fleshes out this assertion. At the same time, the confident articulation of who we are is held in productive tension with the question, Who are we?”

She argues that this dual approach is “a practice of ‘Oiwi survivance. As Anishinaabe author and cultural critic, Gerald Vizenor writes, ‘Survivance is the continuance of stories, not a mere reaction, however pertinent.’ Survivance is about our lahui’s ‘renewal and continuity into the future...through welcoming unpredictable cultural reorientations.’ i hadn’t heard of survivance before, so i’ll have to read gerald vizenor.

on ea: “ea is an active state of being. Like breathing, ea cannot be achieved or possessed; it requires constant action day after day, generation after generation.”

“the health/breath of the people is directly linked to the health/breath of the land.”

she quotes Kumu ‘Imaikalani Winchester, an educator who restores lo’i kalo (taro ponds):

“For a sixteen-year-old kid who knows nothing else other than living downtown some place, if they can get out and experience some different things, return to their past, they can actually breathe that life - that ea - into our culture and traditions again. ... Hawaiian education is carrying the heavy kuleana of introducing collectivist ideas into a very individualist world, where private property, capitalism, and the free market runs or guides most decision making and policies.”

a few scholar she quotes whose work i’ll have to investigate:

Robert Allen Warrior

Taiaiake Alfred

Leanne Simpson

Linda Tuhiwai Smith (author of Decolonizing Methodologies)

Jeff Corntassel

Lilikala Kame’eleihiwa (author of Native Lands and Foreign Desires: Pehea la e pono ai?)

Ua Noho Au A Kupa I Ke Alo by R. Keawe Lopes Jr.

Lopes uses the words of a mele (chant) to explore concepts that have been central to his research.

noho:

“In conducting research within our communities, building relationships with mentors is vital to acquiring information. The quality of knowledge shared and gained is dependent on the depth of the relationship. The first two lines of the mele state ‘ua noho au a kupa i ke alo, akama’aina la i ka leo,’ which means ‘I have sat, inhabited, and tarried here until I have become accustomed to you in your presence and familiar with your voice.’”

noho is ‘“to live, reside, inhabit, occupy (as land), dwell, stay, tarry, marry, sit” and has the connotation of establishing oneself in a certain place or with a particular person... Historically, to noho was to express humbleness and respect...” i think this reflects a culture of learning that’s based on a master/mentor-student relationship, or an apprentice relationship. something that in western culture one might associate with learning a skilled craft or art. i really like the idea of approaching people with noho. it puts the would-be student into the right frame of mind to learn.

kupa:

“to identify oneself as a kupa, one must be a longtime resident, possessing personal and lasting relationships with the people and the mo’olelo of that place, both ancient and modern.

The term ‘kupa’ further implies that the commitment to our mentors is a lifelong investment.”

in describing his studies of mele and hula with his mentor, Lopes writes:

“Often the real in-depth learning of contextual information related to mele and hula began after our regular class sessions were done. Sometimes it continued for hours in the parking lot. In such moments exciting mo’olelo of mele and hula exponents of the past were shared. This experience taught me that, to persevere in a lasting relationship with our mentors, we must be truly passionate and extremely patient. These qualities will enable us to endure both good times-days of great epiphany and hours of captivating conversations-and bad. True patience considers the cost and makes the necessary sacrifices to always be ready and available for learning, no matter the time or place.”

kama’aina:

“’kama’aina’ reinforces the importance of investment; moreover it implies the idea of being embraced geneologically... ‘kama’ means ‘descendant’ or ‘child.’ It also means to be bound or tied to something. The term ‘’aina’ means ‘land.’ ‘Kama’aina’ therefore are genealogical descendants of the land, bound and secured to it and who benefit from a reciprocal relationship with her. As a result, kama’aina care for the well-being of the land while maintaining a mutual relationship with her.

This type of reciprocation is seen in student-mentor relationships as well.”

alo:

“The ‘alo’ is the front, face, or presence of a Person (Pukui 1983, p.21). It tells us where our attention is directed and where our interests lie. It is my belief that if we turn our alo toward our mentors and keep our interest faced in their direction, they will know that we truly have a vested interest in gaining knowledge and value the relationship we have with them. When our mentors decide to turn their attention to us, it is then that we realize that we are just as important to them. It is when our alo and the alo of our mentors are attentive to each other that the most effective teaching and learning opportunities occur. This type of experience is known as ‘he alo a he alo’ or ‘face to face’ (Pukui 1983, p.21).

He alo a he alo is the way in which relationships are built and the way knowledge is transmitted, communicated, and received. There is no clearer way to be in a relationship or in communion with another person than he alo a he alo.”

Leo: engagement of the Voiced

“In an oral-based society, the leo (voice) is an important tool of expert orators who keep our people connected to the past by reciting our ancient mele and mo’olelo... They enlighten us with insight that becomes embedded in our memory. The leo is the eternal link between our people past and present. It transcends place and time and is audible even beyond the physical.” (i believe this is referring to the way that you can picture a family member telling you something they always told you even after they’ve passed away)

also, if you teach with all the love that you’ve been taught by a beloved elder, if you’ve done right by them, then you may find your students sounding just like the elder. this is another way that you can hear the ancestors’ voice after they’re gone.

---

here’s a great saying: “Hilihewa kahi mana’o ke ‘ole ke kukakuka” (”ideas run wild without discussion”) (Pukui 1983, p. 106) “As Pukui explains, to learn and be aware of the specifics of any knowledge, it is necessary to be personally involved (p.24).

This involvement is necessary for learning the mana’o (thoughts, intentions, beliefs) of our mentors (Pukui and Elbert 1986, p. 236). Pukui explains that the mana’o is not something that is readily seen: It is concealed in a number of layers of interpretations. As it is said, 'He ana ka mana’o o ke kanaka, ‘a’ole ‘oe e ‘ike ia loko,’ which means that ‘the thoughts of man are like caves whose interiors one cannot see’ (Pukui 1983, p. 64).”

---

“As explained, by being in constant contact with our mentors’ alo and leo we are able to experience their intentions, thoughts, and beliefs. This is when we are allowed access to the ‘waihona.’ A waihona, according to Pukui and Elbert, is a ‘depository, closet, cabinet, vault, file, receptacle, savings, or a place for laying up thing in safe-keeping’ (1986, p. 378). A waihona could also be a person, as expressed in the saying ‘Ka waihona o ka na’auao,’ which is a reference to a person who is a repository of knowledge and is considered to be learned (Pukui 1983, p. 178).

The location of this waihona to which Kalakaua’s mele refers is ‘i’ane’i’ (right here) within our reach. It is a waihona that contains aloha or that has been cared for by aloha or is in the possession of aloha.”

“I have heard kupuna share that the term ‘aloha’ is made up of two words - alo (presence) and ha (breath) - and its meaning is so much more than a kind disposition. Aloha is that which births in all of us the patience to endure, the courage to hold fast to our traditions, and the strength to face any adversity. Pilahi Paki, a renowned kupuna, explained that each of the letters that make up the word ‘aloha’ have meaning that comprises its overall significance:

Akahai, meaning kindness to be expressed with tenderness;

Lokahi, meaning unity, to be expressed with harmony;

‘Olu’olu, meaning agreeable, to be expressed with pleasantness;

Ha’aha’a, meaning humility, to be expressed with modesty;

Ahonui, meaning patience, to be expressed with perseverance.”

“Paki encouraged us ‘to hear what is not said, to see what cannot be seen and to know the unknowable.’ I find this very true for those of us who invest in relationships and experience the alo and leo of our mentors, who that even when things are not said there is something to listen for, when there is nothing to see there is something to notice, and when the unforeseen arises we rest assured of what we have already been taught.”

He Lei Aloha ‘Aina by Mehana Blaich Vaughan

This chapter is about lei, both actual lei and lei as a metaphor. It also includes bits from the author’s personal history and how this history has shaped her approach to research, and discussion of an education/research/conservation trip to Lumaha’i Valley on Kaua’i.

It begins with these two sayings:

“He lei pa’iniu no Kilauea. (A lei of pa’iniu, signifying that the wearer has visited Kilauea Crater.)

He lei pahapaha no Polihale. (A lei of pahapaha limu, signifying that the wearer has visited Polihale, Kaua’i.)

Throughout Hawai’i, lei symbolize certain places and show that the wearer has experienced them. Lei offer a way to see and know a landscape because each lei is unique to the place where it is made.”

“My Tutu, Amelia Ana Ka’opua Bailey, taught me to pay attention to ‘aina, with a focus on what type of lei could be made from each place. Riding with Tutu in the car was an adventure because she was always looking out the window, her eyes tracing the trees, the bank along the side of the road, even the median strip of the freeway. I remember waiting in the car as she darted across four lanes of H-1 to pick salmon-colored bougainvillea, a Times supermarket grocery bag trailing behind her. Whether driving the saddle road on Hawai’i Island or the streets of her own Manoa Valley, Tutu was watching for flowers. To her, every landscape offered a tantalizing vision of its own lei just waiting to be made.

I have a similar craving to weave stories of certain landscapes. Since I was a child, everywhere I went, I remember wondering, Who are the people of this place? What did it look like before? What parts of it (plants, views, fish, rock, walls) are still here? Will they be here in the future?”

In the discussion of the trip to Lumaha’i Valley:

“When the sound of the helicopter trailed off, our group offered oli komo, asking to enter. We also addressed Laka, all around us in the dwarf lehua, flowering ‘ie’ie, and three different vining maile sisters. As we gave our lei and ho’okupu, I was reminded of one community member’s question as we were getting input for the trip: ‘If you believe in Laka, why go? You don’t believe she can handle the forest on her own?’ To me, our offerings, our presence in that place were a means of ho’omana, giving strength to Laka, just as she gave strength to our efforts. Still, each step in the bog felt tender, and no matter how carefully we walked, we stomped on the moss, leaving indentations for mosquito puddles. Each sling load that brought tents, cereal boxes, coolers, the work, and our other gear further flattened uluhe under the weight, sound, and wind of the chopper.”

“This trip, unlike many conservation and environmental research efforts in Hawai’i, incorporated means of acknowledging the sacredness of our ‘work site’ and asking its guidance; of accessing people’s stories and connection to this place, however tentative and distant; and of reconnecting the place to community by training younger generations descended from the area to take care of it. These three threads gleaned from our trip continue to shape my attempts at ‘aina-based research: ‘aina as source, ‘aina as people, and ‘aina as ongoing connection and care.”

“We stand facing the lunging water, teeth chattering, and find our voices...This oli asks permission of this place, of the wai, the water itself, for our work. We explain the purpose of our study, why the water will be used, and how. May we take just a small sample from its home in the kahawai, the stream? Just as a pohaku, rock, needs to know the function for which it is being selected so that it may lend its mana to the effort, wai should be asked to come along too.”

“Once removed, these aspects of ‘aina must continue to be treated with respect.”

“...’Aina should be not only subject but also partner, source, inspiration, and guide.”

“...it is rarely easy to identiy the community of people with connections to a place; this community is often unseen. However, every place in Hawai’i has people attached to it who care about and hold deep wisdom of it. These people [are] worth seeking...”

There’s an excellent story about fisherpeople who were involved in community planning for their fishery: “The fishermen wanted to extend our study to understand where fish from the area ended up. We worked together to track what fish they caught, who they gave them to, and where. This work revealed a network of families connected to Ha’ena’s coast by receiving gifted mahele, or shares of fish, even though they lived on the other side of the island or even on the mainland. Most of these fish recipients had ancestral ties to the area...” This illustrates the point that “People’s connections to places are often built through use.”

"s much as possible, I attend regularly scheduled community meetings and workdays to get feedback on research progress and share preliminary findings. These sessions usually include food and informal discussion, often yielding valuable insight into whether our findings ring true, potential explanations for them, and future directions for research. I also hold formal community presentations to share research in forms that can be utilized to support community efforts. ...my research emphasizes helping people add to in-depth knowledge of places where they have kuleana, responsibility.”

“My research often comes together in mo’olelo, storytelling, and in poetry, avenues our kupuna used, like lei, to make beloved places seen and felt.”

“In my environmental research, I am guided by Tutu’s informal, mostly unspoken, instruction in gathering for lei. Oli first: Ask and explain the purpose for your gathering. Look. Listen. Take only what you need. Clean your materials before you depart, leaving as much as you can with the plants to rejuvenate and replenish. When the process is complete, and the lei dries, bring it back to this spot or return it to some other ‘aina to bring growth.”

The author concludes with a poem composed of “individual bits of material gathered from the area where I grew up.”

“Research, like lei, should bring growth along with beauty, should weave disparate elements together in a way that shows new perspective and creates new life.”

Here is the poem. I love it because it includes all kinds of good things to know about a place. This is my kind of knowledge.

Pu’unahele

WAO NAHELE - UPLAND FOREST, 140 ACRES, TMK #13-531

Name lost

Bird catchers' camp

Where orange lehua once bloomed

Branch coral laid gently on an altar

The place where hte hungting dogs froze

Road launching power lines over the mountain

Straightest guava branches for kala'au

The spot the Pleiades first crest the ridge

In October's crisping dusk.

KULA - FLATLANDS, 10.2 ACRES, TMK #13-45

Below Pu'u Maheu, hill-raking winds

wet soil for growing 'uala

Sunset view meditation spot

Place to check surf at "Wires"

Night path of the spirits returning from shore

Where we kids used to ride our bikes

The first gated driveway that we'd ever seen

Former route of the sugar cane train

Field #45, best yield per acre

State land-use classification...Ag.

KAHAWAI - RIPARIAN ZONE, 1.4 ACRES, TMK #13-172

A taro patch called Nahiku

'Auwai with 'o'opu mouths big as a fist

First place to flood, now so much less water

Where the cousin on crystal meth hides

Rocks the women scrubbed clothing clean on

Roof dropped there by the tsunami

Perch for the child scaring rice birds

Stand up paddle right out to the beach

Option to construct two ADU's (ed: additional dwelling unit)

Vacation rentals with kitchenettes

KAHAKAI - COASTAL LANDS, 0.2 ACRES, TMK #13-890

Kamakau, the long curving hook

Line of shells swept up by first swell

The hill used to kilo (ed: spot fish), direct them to moi

The space to spread nets out to dry

Two turtle eggs hatching one March morning

Outflow of bagasse from the mill

Shearwater flyway that stopped power lines

Where the sand departs from in the fall

'Aholehole caught for baby's lu'au

Eel circling the spot Uncle cleaned them

Those 'champagne pools' the guidebook named

Six visitors swept away this last winter

Private beach view, price $2.7 million dollars

Right where the fishing trail used to descend

continue to part 2!

0 notes

Quote

Of course, indigenous peoples have a right to a standard of living equal to that of others. But to stop there and continue to deny their nationhood is to accept the European genocide of five hundred years. Attempting to right historical wrongs by equalizing our material conditions is not enough. To accept the simple equality offered lately would be to forget what indigenous nations were before those wrongs began.

Taiaiake Alfred, Peace, Power, Righteousness: An Indigenous Manifesto

0 notes

Photo

Working together to know our family history

Mamie and I in our little home in Beauharnois in 1990. We are making our family history together. I have managed to go up to 10 generations so far, thanks to her memory and archives. I believe it’s by knowing where we are from and our position as of our privileges that we can truly start to decolonize ourselves in order to resurge as free beings. I thank Frantz Fanon, Malcolm X, Leanne Simpson and Taiaiake Alfred for teaching me that through their books and my Indigenous, activist and intellectual friends who honor me of their friendship. Philosophying with you is emancipatory.

#childhood#resurgence#oldpic#decolonizeyourself#autoethnography#settler colonialism#in memory of frantz fanon#ma grand-maman#decolonize yourself!#working class#white settlers#Anthropology#anthropologist#ExploringMontreal#SubletiesofMTL#DiscoverMontreal#HistoryofMTL#PopularHistory

0 notes

Quote

Taiaiake Alfred’s work unpacks the ways in which the state institutional and discursive fields within and against which Indigenous demands for recognition are made and adjudicated can come to shape the self-understandings of the Indigenous claimants involved. The problem for Alfred is that these fields are by no means neutral: they are profoundly hierarchical and as such have the ability to asymmetrically govern how Indigenous subjects think and act not only in relation to the recognition claim at hand, but also in relation to themselves, to others, and the land. This is what I take Alfred to mean when he suggests, echoing Fanon, that the dominance of the legal approach to self-determination has over time helped produce a class of Aboriginal ‘citizens’ whose rights and identities have become defined more in relation to the colonial state and its legal apparatus than the history and traditions of Indigenous nations themselves. Similarly, strategies that have sought independence via capitalist economic development have already facilitated the creation of an emergent Aboriginal bourgeoisie whose thirst for profit has come to outweigh their ancestral obligations to the land and to others. Whatever the method, the point here is that these strategies threaten to erode the most egalitarian, nonauthoritarian, and sustainable characteristics of traditional Indigenous cultural practices and forms of social organization

Glen Sean Coulthard, Red Skin White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition pg. 42

#coulthard#glen sean coulthard#red skin white masks#alfred#taiaiake alfred#state#institutional#discursive#fields#indigenous#demands#recognition#adjudication#claimants#neutral#hierarchical#hierarchy#asymmetrical#govern#subjects#think#act#action#agency#land#others#fanon#legal#self-determination#aboriginal

0 notes