#Unryū

Text

instagram

The Iron Tiger Forge Cloud Dragon Katana features in brilliant detail the Unryū sky dragon among an elevated koshirae setting and a lacquered rayskin saya scabbard. The blade is hand forged from 1095 high carbon steel and has been differentially tempered using the traditional clay tempered technique, as evident by its genuine hamon which was carefully shaped into the form of billowing clouds along the length of the blade edge. A fine finishing polish to the blade highlights the natural beauty of this hamon of hardened steel and its genuine geometric tip yokote.

In stock and available to order now

#Kult of Athena#KultOfAthena#Iron Tiger Forge#Cloud Dragon Katana with Rayskin Scabbard#Cloud Dragon Katana#katana#katanas#sword#swords#weapon#weapons#blade#blades#Japanese Swords#Japanese Weapons#Asian Swords#Asian Weapons#Unryū#Unryu#dragon#dragons#Instagram#videos

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The capsized Japanese Aircraft Carrier Amagi (天城, Mount Amagi) at the Kure Naval Arsenal, Japan.

Date: October 8, 1945

NNAM.1996.488.037.007

#Japanese Aircraft Carrier Amagi#Amagi#Unryū Class#Unryu Class#Japanese Aircraft Carrier#Aircraft Carrier#Carrier#Warship#Ship#Capsized#Kure Naval Arsenal#Japan#Kure#October#1945#postwar#post war#Imperial Japanese Navy#IJN#battle damage#sink#my post

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

who do you think the JP anniversary UR is gonna be?

yeah. just take a wild guess.

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Unryū-in is a sub-temple of Sennyū-ji in Kyoto, Japan. Photography by うさだだぬき ⛩usadanu.eth

@usalica

234 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (66): Fusube-chanoyu [フスベ茶湯] -- a Tea Gathering Held Out-of-doors.

66) With respect to the expression fusube-chanoyu [smoky-chanoyu], this is a slang term¹. This [name] refers to [the practice of] no-gake [which means hanging up a kama in the field]². Purity of mind, as well as in a physical sense, is its guiding principal³.

At Daizenji-yama [south of Fukuoka], and also in the pine-barrens at Hakozaki in Chikuzen [now within the confines of Fukuoka City], [Ri]kyū improvised -- since [these chakai] were [being staged] in the shade of the pines -- by raking up pine-needles [as fuel for the fire], which seemed [to him] a very natural way to boil [the kama]⁴. When the boiling [water] raised its voice in the pine-wind[-sound], the smoke, rising upward like a column, was very interesting⁵! Since after that his highness, when indulging himself with an outing [for such purposes as hawking], often called for [Ri]kyū, [Sumiyoshi-ya] Sōmu [宗無], or else [Tennōji-ya] Sōkyū [宗及], [to perform] this “fusube-chanoyu,” everybody started referring to it as smoky-chanoyu⁶.

At Daizenji-yama, a one-chō [square] on the south side of the lower [post] road [was secured for Rikyū’s fusube-chanoyu]; while at Hakozaki, in a direction north-east of the Ebisu-dō [惠比須堂], four or five chō were cordoned off as the tea area. The unryū-gama was hung from a pine tree, and a tea-box was opened [to reveal the utensils]. [These details] are also [described] in [Ri]kyū's oboe-gaki [覺書]⁷.

On [another] occasion at the Tadasu[-no-mori], on the middle path leading to the [Lower Kamo] Shrine, [Rikyū hosted a fusube-chanoyu] beside the stream that flows through that small grove of pines⁸. Up until that time, when there were no pine trees, the kama was suspended from three lengths of bamboo [bound together at the top to form a tripod]. And when water was [flowing] nearby, so that the mizusashi could be dispensed with, the chakin would then be placed on the lid of the kama [throughout the temae]. When a certain person asked about the thinking behind this one gathering, with respect to doing that kind of thing, [he wondered whether] things should have been done that way? 〚[To which came this reply:] “in this particular gathering, with respect to the matter of purifying [the utensils] through rinsing [them], it was not only the things that were used to prepare tea [that were so purified]⁹.”〛

When doing something with one’s whole heart, no action is ever trivial. And as soon as we achieve mastery, we should immediately look back to assess our own capabilities [honestly] -- this is what has been handed down¹⁰. 〚The hearts of the people should not be sullied; and to be ignorant of this is a grave disgrace¹¹. Even if it were placed on the ground, we might expect it not to be dirtied -- if the heart has been purified. The mind of a single nen [念] is difficult to comprehend, so it is said. But if [we] say that it is difficult for us to understand this one gathering, [we must not forget that] it is extraordinary when even a group of great monks are all moved to admiration by the same thing -- and so the other people had best keep [their opinions] to themselves¹²!〛

The understanding of this monk -- as well as [that of] many other [people] -- is exceedingly shallow. So it cannot help [me to comprehend this matter]¹³.

_________________________

◎ This text appears to be an Edo period effort to expand Rikyū’s comments on the way to host an outdoor tea gathering in Book One* to encompass the sort of “philosophical tea” that was being promoted by the Sen family during the first century of the Edo period (in the wake of Takuan Sōhō’s influence).

The different versions of this entry are more or less the same†, though there are some differences -- the most important of these is that Shibayama Fugen’s toku-shu shahon [特殊写本] and Tanaka Senshō’s “genpon” [原本] texts add some important information near the end of the passage. I have attempted to incorporate these ideas into the translation, enclosed in doubled brackets, as always.

And finally, in addition to the text and its variants, I decided to translate Tanaka’s comments (on the last section of the entry, the section that deviates from the Enkaku-ji version) in full, in an appendix (that will be found at the end of this post) -- because I believe the modern practitioner of chanoyu will find his insights both amusing and enlightening.

___________

*See the posts entitled Nampō Roku, Book 1 (31): No-gake [野懸け]¹ -- the Daizen-ji Mountain Chakai, and Nampō Roku, Book 1 (32): No-gake (part 2) -- the One Path of Tea. The URLs for those posts are:

○ Nampō Roku, Book 1 (31): No-gake [野懸け]¹ -- the Daizen-ji Mountain Chakai:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/176889262939/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-1-31-no-gake-%E9%87%8E%E6%87%B8%E3%81%91%C2%B9-part-1

○ Nampō Roku, Book 1 (32): No-gake (part 2) -- the One Path of Tea:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/177035199937/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-1-32-no-gake-part-2-cha

†So much so, apparently, that Tanaka only bothered quoting the very end of the passage, where the additional information is found (cf., footnotes 9, 11, and 12, below). As a result, I will not be able to discuss any earlier variants in his genpon text -- as I will be able to do, in the footnotes, with Shibayama’s toku-shu shahon material.

¹Fusube-chanoyu to iu-koto ha zoku-myō nari [フスベ茶湯ト云コトハ俗名也].

Fusuberu [燻べる] means to fill a space with smoke, so fusube-chanoyu [燻べ茶の湯] means smoky-chanoyu, chanoyu being performed in a smoke-filled space (the smoke tends to buffer or isolate the gathering from the surrounding expanse of nature, much as the walls of a tearoom do, creating a unique sensory experience).

The charcoal used for chanoyu is carefully selected precisely so that it does not produce any smoke as it burns. Here, creating a fire using the slightly damp pine needles that are found naturally in the spot, produces quite the opposite effect -- creating a misty sort of situation that is enhanced by the pine trees (which seem to hold in the smoke, keeping it from rising or dissipating quickly). Furthermore, the smoke is perfumed with the smell of pine resin, making it less offensive than would be the smoke from imperfectly carbonized charcoal.

Zoku-myō [俗名] means a popular name -- the word seems to include the nuance that said term is a little slangy or lowbrow.

Here Shibayama Fugen’s toku-shu shahon has: fusube-chanoyu to iu-koto ha, zoku ni iu na nari [フスベ茶湯ト云コトハ、俗ニ云フ名ナリ]. This means “when we speak about ‘fusube-chanoyu,’ it can be said that this is a rather vulgar epithet.”

²No-gake no koto nari [野ガケノコト也].

No-gake [野懸け, 野掛け] means to hang (the kama) up in the field.

In other words, this is the more polite or cultured designation for the practice.

In chanoyu it was not uncommon for the crude usages of servants and laborers to be incorporated into the lexicons of the different schools during the Edo period* -- perhaps this was a reflection of the general tendency toward secrecy and dissimulation that began to pervade the practice after its division into a number of competing schools (each of which was intent on keeping their ways of doing things secret from the competition).

___________

*Two well-known examples are the terms tsukubai [蹲踞] and nijiri-agari [躙り口].

Tsukubai was appropriated from son-kyo [蹲踞] (the same kanji, albeit read with a different pronunciation), the formal crouch assumed by the participants in a sumo match -- apparently the gardeners likened the attitude assumed by the guests when rinsing their hands and mouths at the low chōzu-bachi [手水鉢] to the son-kyo, but used this alternate pronunciation (which actually derives from the first kanji) as a way to disguise their jibe.

Likewise, nijiru [躙る], which means to shuffle, was a way to jokingly describe the awkward way that the guests have to wriggle in slowly, moving their knees forward little by little, through the nijiri-guchi. The nijiri-guchi itself appears to have been preferred by the machi-shū followers of Imai Sōkyū, and become standard (even in the larger rooms) under Sōtan. (Rikyū’s rooms with nijiri-guchi were all rebuilt in this style during the Edo period -- despite the propaganda, spread by the Sen family, which argued that they were authentic. The sliding doors in the seawall that were Rikyū’s inspiration were stepped through, as in Rikyū’s naka-kuguri [中潜り] located between the inner and outer roji, not passed through on one’s knees.)

Let us entertain a brief digression here.

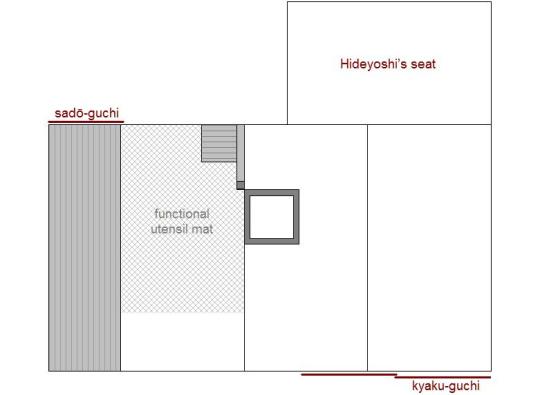

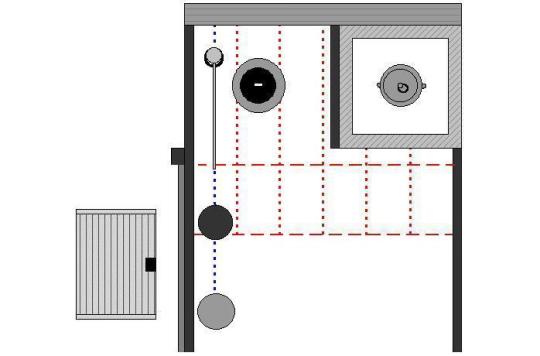

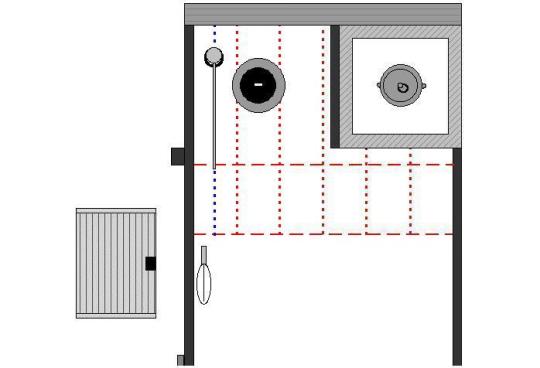

As an aside, Jōō’s and Rikyū’s small rooms had the guests enter through a pair of shōji panels which, while not full size, were still significantly higher than even the highest of the “classical” nijiri-guchi (which is the one installed in the Tai-an) -- meaning that there was no need to shuffle through the entrance in this way, nor any danger of accidentally elevating the torso too soon (and so hit the back of one’s head on the lintel of the door). The configuration of Rikyū’s actual Tai-an [待庵] is shown above.

Regarding the nijiri-guchi found on the Tai-an today, this was originally Rikyū’s naka-kuguri [中潜り], the sliding wooden door through which the guests stepped when passing into the fully enclosed inner-roji. In Rikyū’s rooms, the inner-roji was a small courtyard containing the chōzu-bachi and a roofed-over platform-like veranda (sometimes little more than a bench, though occasionally as large as one-mat in size) on which the guests sat during the naka-dachi (and by means of which they entered the tearoom by passing through the shōji that adjoined it).

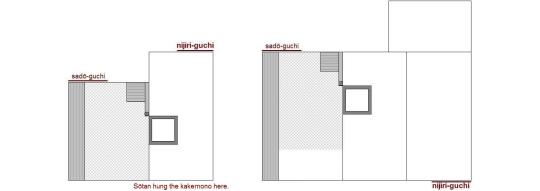

The naka-kuguri was installed as the nijiri-guchi by Sōtan’s son Kōshin Sōsa, when he remodeled the Tai-an so that it would more closely resemble Sōtan’s Fushin-an [不審庵] (shown above, on the left). Kōshin’s modifications to Rikyū’s Tai-an are shown on the right, with the way it was derived from Rikyū’s room is documented in the drawing below.

While Kōshin retained Rikyū’s original three-mat configuration, he reduced the width of the ita-datami onto which the original sadō-guchi opened, from Rikyū’s 1-shaku 8-sun 5-bu to the present 8-sun -- since this was the width of the ita-datami in Sōtan’s Fushin-an (even though the Fushin-an was, at that time, a 1-mat daime room). Reducing the width of the ita-datami necessitated a corresponding reduction of the width of the toko (in order to retain the same spatial configuration of the preparation area that functioned as the room’s mizuya), with its depth adjusted accordingly in order to maintain the Sen family’s preferred proportions.

The complete repudiation of the original utensil mat, effected by erecting a pair of fusuma between the naka-bashira and the lower end of the mat, thereby turning Rikyū’s 3-mat room (that was used like a 2-mat daime) into the current 2-mat format, incorporating a sumi-ro of non-standard size (the ro that was used was the one that was supposed to be used in an inakama room, which tends to belie the argument that the person responsible for these changes was an expert in the Nampō Roku, as he claimed), occurred during the nineteenth century -- with the intention of making the room appear different from Omotesenke’s Fushin-an (primarily because the person who effected the changes had an intense personal animosity toward Omotesenke).

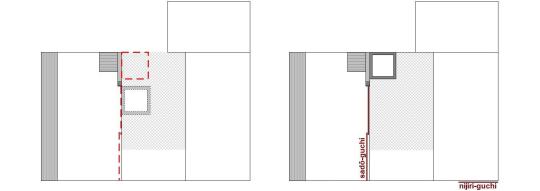

The only authentic portion of the present Tai-an is the tsuri-dana, and the sode-kabe (the wall on the right side of the photo) to which it is attached.

Rikyū’s tsuri-dana (the Tai-an was the first daime room that featured a tsuri-dana) had only a single shelf, as seen here; the tsuri-dana with two shelves was proposed (several years later) by Furuta Sōshitsu, while the one with three shelves was subsequently devised by Kobori Masakazu early in the seventeenth century. Rikyū’s sode-kabe lacked the fenestration at the bottom of the wall (this was another of Oribe’s creations, and one that is considered an important feature of the arrangement today). The wall on the far side of the tsuri-dana (to which the tsuri-dana is not attached) seems to have been replastered when the sadō-guchi was moved closer to the tsuri-dana (this became necessary when Kōshin Sōsa reduced the width of the ita-datami to 8-sun: the original sadō-guchi had opened fully onto the ita-datami, which Rikyū used as a sort of runway by means of which he walked to the lower end of the utensil mat, from where he bowed and greeted Hideyoshi at the beginning of his temae).

The rest of the room has been changed completely from anything that Rikyū himself would have recognized.

That said, if you search through the literature, you will find innumerable tomes by famous scholars that explain how Rikyū created and used the 2-mat room with its 1-shaku 3-sun sumi-ro [隅爐] (in other words, the room as it exists today, which is how it was reconstructed in the nineteenth century), all of whom will be very happy to discredit me and what I have written above with a red-faced vehemence. I first arrived at these conclusions, nevertheless, after a very, very careful and multi-yeared study of the measurements of the Tai-an -- since the wall between the sumi-ro and the tsuri-dana can only be interpreted as a sode-kabe, according to Rikyū’s own teachings on these measurements. Many years later, I also found the same argument made by the eminent Japanese art historian and scholar Ōkōchi Nobutake [大河内信威; 1902 ~ 1990] (in cultural matters, he is also known as Ōkōchi Fūsenshi [大河内風船子]), who carefully explored the evolution of this room in his own writings.

I decided to mention all of this here, even though it has nothing to do with the no-gaki no chakai, because it is an example that the reader should always keep in mind when listening to, or reading, the explanations of classical matters as interpreted by the modern schools and their affiliated scholars: the evidence in support of their assertions will usually be mountainous (yet a careful look will generally reveal that most of those books were written by the same small circle of proponents); but even if everyone is intent on arguing that a certain thing is true, that does not mean that it is necessarily historically factual. The schools, for all the arguments that they frame in such a way so as to suggest the contrary, are businesses; and, because chanoyu is a traditional activity, the way they strive to enlist new students is by claiming that they -- and they alone -- are the true and authentic representatives of the tradition. This is why, on the one hand, they burn incense to Rikyū, and swear by the veracity of the Nampō Roku (when something -- usually something in Book Seven -- supports their claims), and then zealously disavow his (historically authenticable) teachings as lies and fabrications (when they conflict with that school’s preferred way of doing something), on the other. The first six books of the Nampō Roku are largely true; and Book Seven is largely spurious.

³Seijō-keppaku wo moto to su [淸淨潔白ヲモトヽス].

Seijō-keppaku [淸淨潔白] means something like (be) pure in thought and deed*. It is a Buddhist aphorism, of the sort that became popular during the Edo period (the phrase is found in a text known as the Yo-ji juku-go [四字熟語], which was being used in the temple-schools to teach students to read kanji†).

Here it means that this idea of purity in mind and body is central (or, as it says, the fundamental principal -- moto [本]) to the no-gake. Perhaps because, historically speaking, no-asobi [野遊] seems to have not infrequently degenerated into a licentious sort of escapade (given that the area was usually surrounded by curtains -- rather like a boudoir -- and protected by a company of guards who all faced outward).

__________

*Kotobank (jp) explains the phrase in this way:

kokoro ga utsukushiku, okonai ni ushiro kurai-tokoro ga nai koto

[心が美しく、行いにうしろ暗いところがないこと].

This means “be noble and pure in heart, and have nothing dark in anything that you do.” Kurai-tokoro [暗い所] literally means a dark place (and could be understood in a similar way to the modern idiom “being in a dark place”). In a Buddhist context, this darkness usually suggests ignorance (of the True Way), being misguided, being deluded; a state of intellectual morbidity, rather than evilness of purpose. In other words, it is the antithesis of the clear-eyed state of enlightenment.

That said, in the context of the present entry, the expression seijō-keppaku is being used in a more mundane sense -- that is, when participating in a no-gake no chakai, we should keep our mind focused on what is pure, rather than allowing ourselves to be distracted by carnal thoughts or desires (as discussed in the second paragraph).

†I have been unable to find any reference to when this particular text was first used in Japan.

Books of this sort had been used in Korea since at least the Goryeo period, and remained popular tools (especially in the clan-based schools that were set up on the grounds of their Ancestor shrines) well past the middle of the 20th century. Many books of this sort (that show the influence of the Korean neo-Confucian-infused Buddhism) began to arrive in Japan beginning in the early Edo period (starting with Taku-an Sōhō [澤庵宗彭; 1573 ~ 1645], who arrived in Japan in 1603 -- according to Kanshū oshō, who was his direct descendant), though the book could have been brought to Japan earlier.

Taku-an’s intention was apparently nothing less than to undertake the reformation of Japanese Buddhism.

⁴Daizenji-yama, mata ha Chikuzen no Hakozaki-matsubara ni te Kyū no hataraki ni, matsukage naru-yue matsuba wo kaki-yose sawa-sawa to yu wo wakashi [大善寺山、又ハ筑前ノ箱崎松原ニテ休ノハタラキニ、松陰ナルユヘ松葉ヲカキヨセサハ〰ト湯ヲワカシ].

Daizenji-yama [大善寺山] is an area south of Fukuoka City, between the central mountains and pine barrens of the Chikugo river delta and the coast of the Ariake bay (or sea). The name suggests that, at some point in the past, a famous temple had existed in the region; but all physical traces of this institution have long been lost (the actual site of the temple complex seems to have been unknown in Rikyū’s day; and remains so today as well). The area had been under cultivation since ancient times (since the area had been part of the Gaya kingdom -- perhaps the original rice fields had been established by the Daizen-ji, or were being farmed under its purview), though apparently it had returned to the condition of a moorland by the time (in 1586~7) that Hideyoshi was prosecuting his campaign against the clans of Kyūshū -- in his efforts to incorporate the island into the Japanese nation.

Chikuzen no Hakozaki-matsubara [筑前の箱崎松原] refers to an area, now part of Fukuoka City north-east of the central business and political districts, that had originally been part of the extensive grounds of the Hakozaki-gū [筥崎宮], the important Shintō shrine dedicated to the God Yawata-no-kami [八幡神]*, the apotheosis of the semi-mythical emperor Ōjin [應神天皇].

Kyū no hataraki ni [休の働きに] means the subsequently related details (of raking the pine-needles into a mound that was then set ablaze and used to heat the kama) were Rikyū’s original idea.

Matsukage naru-yue matsuba wo kaki-yose [松陰なるゆえ松葉を掻寄せ] means because the site (selected by Rikyū for this more-or-less impromptu chakai) was in dappled shade beneath the pines, pine-needles were raked up.... The dappled shade implies that the area was forested with pine trees, under which would naturally be found a deep layer of pine-needles covering the ground. Wherefore it was perfectly natural for Rikyū to use them as fuel†, rather than charcoal.

Sawa-sawa to yu wo wakashi [爽々と湯を沸かし]: sawa-sawa to [爽々と]‡ means understandably, logically; yu wo wakashi [湯を沸かし] means to boil the hot water.

Though Shibayama’s text writes matsukage [松陰] as matsukage [松蔭], and wakashi [ワカシ = 沸カシ] as wakashi [湧シ], these are simply alternate ways of writing the same kanji-compounds. The sentences themselves are identical.

__________

*Now his name is usually pronounced Hachiman-jin [八幡神].

†By raking the needles into a mound, Rikyū exposed the damp ground in a circle around the fire. Doing so helped to prevent the fire from spreading out of control.

‡Sawa-sawa [爽々] is also used to mean refreshing, and also to mean clearly, unambiguously. While it seems that many commentators lean toward refreshing (because the text is describing an outdoor chakai), the context seems to demand understandably, intelligibly, or logically -- the idea to simply rake up a pile of pine-needles to use as fuel would follow naturally from the fact that the ground under the pine trees would be thick with pine needles.

⁵Waki-tatetaru shōfu no hito-koe, keburi no tachi-noboru-tei omoshiroshi-tote [ワキ立タル松風ノ一聲、烟ノ立ノボルテイ思白シトテ].

Waki-tatetaru shōfu no hito-koe [沸き立てたる松風の一聲] means when the boiling water raises its voice in the pine-wind(-sound)....

Kemuri no tachi-noboru-tei [烟の立ち上る躰]: kemuri [烟] means smoke, fumes (because only the top layer of pine needles are completely dry, the incorporated moisture will color the smoke white or pale-gray); tachi-noboru [立ち上る] means (the smoke) rises straight up; tachi-noboru-tei [立ち上る躰] means the smoke appears to rise like a pillar*.

Omoshiroshi [思白シ] appears to be either a miscopying, or one of those weird Edo period usages (where unexpected kanji were used as a way to confuse the uninitiated). The word should be omoshiroshi [面白シ] -- which would be omoshiroi [面白い] (“very interesting” or “very amusing”) today.

Shibayama’s version, other than exhibiting the same sort of kanji variants mentioned in the previous footnote, is identical to what is found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript.

__________

*This is all poetically fanciful.

Beneath pine trees, the smoke tends to spread out like a light mist, since the bows of the trees themselves create a very stable microclimate of still air. This is what shōfū [松風], “pine wind,” actually means: the air on the ground (and, indeed, up to the upper branches of the pine trees) is completely still and silent, so that one hears the wind blowing across the tops of the pines from a distance (which is a completely different sensual experience from being within the blowing wind itself).

⁶Denka sono-nochi no-asobi no on-toki ha, tabi-tabi, Kyū ni mo, Sōmu, Sōkyū ni mo, ka no fusube-chanoyu wo dashi-sōre to ōserare-shi yori, mina-hito fusube-chanoyu to iu-koto nari [殿下其ノチ野遊ノ御時ハ、タビ〰、休ニモ、宗無、宗及ニモ、カノフスベ茶ノ湯ヲ出シ候ヘト被仰シヨリ、皆人フスベ茶湯ト云コト也].

Denka [殿下] means “his highness” -- that is, Hideyoshi.

Denka sono-nochi no-asobi no on-toki ha [殿下その後野遊の御時は] means “after that his highness, on subsequent occasions when he was indulging in an outing (into the wilds)....”

Kyū ni mo, Sōmu, Sōkyū ni mo [休にも、宗無、宗及にも] names three of Hideyoshi's sadō [茶頭], tea officials, who appear to have attended upon him during excursions of this sort. In addition to Rikyū, these were Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu [住吉屋宗無; ? ~ 1595]* and Tennōji-ya Sōkyū [天王寺屋宗及; ? ~ 1591]. All three men were prominent machi-shū chajin from Sakai.

Tabi-tabi...ka no fusube-chanoyu wo dashi-sōroe to ōserare-shi yori [度々...かの燻べ茶の湯を出し候えと仰せられしより] means “from time to time... this kind of ‘smoky chanoyu’ would be performed† when called for‡....”

The phrase ka no fusube-chanoyu [かの燻べ茶の湯] is important, because it means that Hideyoshi was requesting them to perform exactly the same kind of tea service that Rikyū spontaneously improvised on the earlier occasion -- that is, heating the kama by means of burning a mound of pine needles (rather than charcoal) underneath.

This suggests that it was Hideyoshi who either coined, or else was responsible for popularizing, the expression “fusube-chanoyu.”

Mina-hito [皆人] means all of the people, everyone. This expression appears to have been somewhat antiquated (at least by the eighteenth century).

Mina-hito fusube-chanoyu to iu-koto nari [皆人燻べ茶の湯と云うことなり] means “(based on that,) everyone started to call (no-gake) fusube-chanoyu.”

Here Shibayama's version has several very minor changes: denka sono nochi no-asobi-tō no seki ni te ha, tabi-tabi Kyū ni mo, sono-hoka Sōmu, Sōkyū ni mo, ka no fusube-chanoyu wo dashi-sōroe to ōserare-shi yori, hito mina fusube-chanoyu to iu nari [殿下其後野遊等ノサキニテハ、度〻休ニモ、其外宗無、宗及ニモ、カノフスベ茶湯ヲ出シ候ヘト被仰シヨリ、人皆フスベ茶ノ湯ト云フナリ].

Denka sono-nochi no-asobi-tō no seki ni te ha, tabi-tabi Kyū ni mo, sono-hoka Sōmu, Sōkyū ni mo, ka no fusube-chanoyu wo dashi-sōroe to ōserare-shi [殿下そののち野遊等の席にては、度〻休にも、その外宗無、宗及にも、かの燻べ茶の湯を出し候へと仰せられし] means “afterward, when his highness was indulging in pastimes such as outings, in those places he occasionally called out for [Ri]kyū, or the others -- Sōmu and Sōkyū -- to please bring out ‘that fusube-chanoyu.’” This qualifies that when Hideyoshi was calling out for fusube-chanoyu, his intention was that it be served on the spot, wherever he was (rather than having the party move to some other location that had been prepared beforehand).

Hito mina [人皆] (which reverses the two kanji so that we have “the people, all of whom...”) produces the same meaning. To iu [と云う] means “(they) said,” “(they) called (it);” to iu-koto [と云うこと] (as found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript) means “the situation where (they) said,” “the case where (they) called (it)....”

These changes will not have any impact on the meaning in English.

__________

*With respect to Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu, his family business was the brewing of sake; and he had been initiated into the practice of chanoyu by Jōō (even though he was said to have been six or seven years younger than Rikyū).

He trained in Zen under Shun-oku Sōen [春屋宗園; 1529 ~ 1611].

†Dashi-sōroe [出し候え] more literally means “please bring out and do” (as in something that is brought out from one’s “bag of tricks”) -- something that is being held in readiness, so it can be enjoyed on the spur of the moment.

‡Ōserare-shi [仰せられし] means to call upon, or order (an underling) to please do something. In other words, on those occasions when Hideyoshi, spending the day hawking, or indulging in some other such pastime, he would occasionally order Rikyū, Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu, or Tennōji-ya Sōkyū (whichever of these men were attending on him at that time -- all three were members of the group of eight chajin referred to as o-sadō hachi-nin-shū [御茶頭八人衆], whose function was to take charge of all tea-related matters on behalf of Hideyoshi) to serve tea in this way. (Which is why they would always have to be prepared -- since to have to send back to the base camp outside of Hakata for tea and utensils would have offended Hideyoshi severely.)

The o-sadō hachi-nin-shū [御茶頭八人衆] consisted of Imai Sōkyū [今井宗久], Tennōji-ya Sōkyū [天王寺屋宗及], Sen no Rikyū [千利休], Yama-no-ue Sōji [山上宗二], Jū Sōho [重宗甫], Sumiyoshi-ya Sōmu [住吉屋宗無], Mozu-ya Sōan [萬代屋宗安], and Sen no Dōan [千道安; who was also referred to as Shōan or Jōan, 紹安].

⁷Daizenji-yama ni te ha, shimo-michi no minami itchō-bakari, Hakozaki ni te ha Ebisu-dō no tō-hoku yon・go-chō, o-chasho wo kamae, matsu ni unryū-gama wo tsuri, chabako wo hiraku to Kyū no oboe-gaki ni mo ari [大善寺山ニテハ、下道ノ南一町バカリ、箱崎ニテハヱビス堂ノ東北四・五丁、御茶所ヲカマヘ、松ニ雲龍釜ヲツリ、茶箱ヲヒラクト休ノヲホヘ書ニモアリ].

Daizenji-yama ni te ha, shimo-michi no minami itchō-bakari [大善寺山にては、下道の南一町ばかり]: Daizenji-yama ni te [大善寺山にて] means in the (region of) Daizenji-yama; shimo-michi [下道の南一町ばかり] refers to lower of the two the ancient post roads that connected Daizaifu [太宰封] (the ancient capital of Gaya) with the port on the Bay of Ariake -- many years ago I was told that the modern Tenjin-Omuta Line basically follows the course of that road (while the shinkansen follows the upper road); shimo-michi no minami itchō-bakari [下道の南一町ばかり] means 1-chō (a measure of distance of around 109 meters, so a square of roughly that size would have been curtained off) south of the post road*.

Hakozaki ni te ha Ebisu-dō no tō-hoku yon・go chō [箱崎にては惠比須堂の東北四・五町] means an area of 4- or 5-chō to the north-east of the Ebisu-dō† -- this is a reference to the Tamatori Ebisu-jinja [玉取恵比須神社], one of the shrines within the greater Hakozaki-gū: it was located on the north-eastern edge of the complex. In Rikyū’s day, the entire area surrounding the Hakozaki-gū was covered by an ancient pine-barren, so what this means is that an area of some 4- or 5-chō (roughly half a kilometer square) was enclosed by curtains, to establish Hideyoshi’s tea-drinking area.

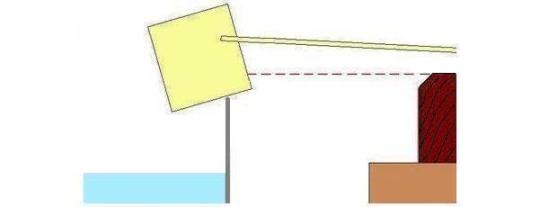

O-chasho wo kamae [御茶所を構え] means (Hideyoshi's) place for (drinking) tea was enclosed in the manner shown in the photo, below‡ -- in other words, areas of the sizes mentioned in the above descriptions were enclosed by hanging red and white striped curtains around the periphery (with guards stationed on the outside, to provide security).

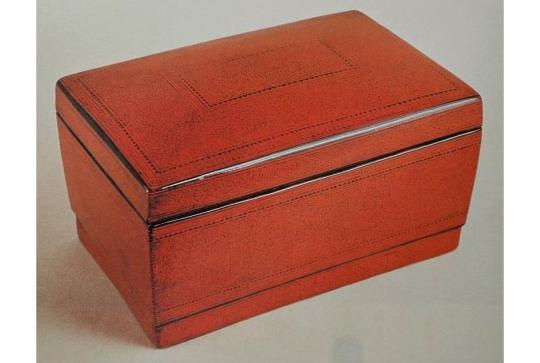

Matsu ni unryū-gama wo tsuri, chabako wo hiraku to [松に雲龍釜を釣り、茶箱を開くと] means the unryū-gama was hung from a pine tree, and a tea-box was opened (to reveal the utensils it contained).

Rikyū’s cha-bako is shown below.

This box measures approximately 8-sun by 5-sun, and is 4-sun 5-bu high. It appears to have been made in Thailand. It would have been imported for use as a te-bako [手箱] (a box small enough to be carried in the hands, in which people like courtiers -- both men and women -- carried their cosmetics, and other small items that they might need throughout the day when on court duty). When used for serving tea, the box (which contained the chawan, prepared with chakin, chasen, and chashaku already arranged in it, together with the chaire, tied in its shifuku) was simply opened, and the utensils it contained lifted out and arranged on thin pieces of wood that were spread out on the ground to receive them. There was nothing resembling a modern cha-bako temae; and tea would have been served in the usual way.

If a stream flowed through the enclosure (as there was, at least, in the Daizenji-yama o-chasho), the kama would be filled directly from the stream -- which would also take the place of a mizusashi (and koboshi)**.

Kyū no oboe-gaki ni mo ari [休の覺書にもあり] means that a discussion of the fusube-chanoyu will also be found in the Book One of the Nampō Roku -- the Oboe-gaki [覺書] book that memorializes some of Rikyū’s stories and teachings††. This reference, however, is a little confusing, since it implies that the Oboe-gaki book was written by Rikyū, where it is actually a record of Nambō Sōkei’s recollections -- while most of the things discussed in Book One are related to Rikyu and his teachings, this is not true of everything.

For the last part of this sentence, Shibayama’s toku-shu shahon has matsu ni kusari ni te unryu-gama wo tsuri, chabako wo hiraku to, Kyū no oboe-gaki ni mo ari [松ニクサリニテ雲龍釜ヲツリ、茶箱ヲヒラクト、休ノ覺書ニモアリ].

The only difference is that this version qualifies that the unryū-gama was suspended from the pine tree on a chain (kusari [鏁]) -- which would be much easier to carry than a take-jizai [竹自在] (even though it would be “less wabi” than the latter).

__________

*The old post road ran roughly east to west in this area. The most likely location would have been on the bank of the Hiro-kawa [廣川], or one of its tributaries (since this would have eliminated the need for a mizusashi).

As this gathering was completely impromptu, Rikyū, Hideyoshi, and the other members of their party, would have squatted down on the ground, and prepared and drunk tea in that way.

†Ebisu [惠比須] was the Shintō god of fishing and commerce (enterprises that took place on the open ocean). As such he was of great importance to the townsmen of both Sakai and Hakata.

Ebisu [夷], as it is written in Shibayama's toku-shu shahon, is one of several hentai-gana ways to render the name of this God.

‡This was done by hanging red and white striped curtains (called kō-haku no maku [紅白の幕]) around the periphery. A phalanx of Hideyoshi's personal guards would have been stationed on the outside of these curtains, to provide the occupants with security. (Remember, Nobunaga met his untimely end because he did not have adequate security surrounding the Honnō-ji when indulging in chanoyu.)

**The host’s seat would be oriented so that, crouching down near the ground, he would be facing upstream, on the bank of the river. Cold water would be dipped directly from the river using a hishaku -- and used water would be poured into the river, too (which is why the host’s orientation was so important).

††Please refer to the two posts that were cited (and linked) in the first sub-note under my introductory remarks, immediately following the translation.

⁸Tadasu ni te no toki ha, yashiro [h]e mairu naka-michi, ko-matsubara no ryū no atari nari [タヾスニテノ時ハ、社ヘ參ル中道、小松原ノ流ノ邊也].

Tadasu [糺] is a reference to Tadasu no mori [糺森] (the Grove of Rectification), a wooded area located just north of the confluence of the Takano and the Kamo rivers, within the precincts of the Lower Kamo Shrine (Shimo-gamo-jinja [下鴨神社]), in Kyōto, where a no-gake chakai was hosted by Rikyū in 1587.

Tadasu ni te no toki [糺にての時は] means on the occasion when (the chakai was hosted) in the Tadasu(-no-mori)....

Yashiro [h]e mairu naka-michi, ko-matsubara no ryū no atari nari [社へ參る中道、小松原の流の邊なり] means on the middle of the paths leading to the shrine, (Rikyū served tea) beside the small stream that flows through the grove. This rill (ryū [流]) is seen in the photo*.

This is referring to a chakai that Rikyu hosted at dusk on the last day of the Sixth Lunar Month of Tenshō 15 [天正十五年六月晦日]† (August 3, 1587), which was the 29th day of that month, the day of preparation for the Kamo festival.

__________

*It was probably because of the small size of the stream, and the fact that the stream flows first through the shrine itself (with many people having been passing through the grounds on that day of preparation), that Rikyū chose to bring water in a sugi te-oke [杉手桶], rather than dip it straight from the stream. (The fact that the chakai would take place in the evening may have also figured into his calculations, since exposed water was said to become poisonous after dark.)

†Please see the post entitled Nampō Roku, Book 2 (42): (1587) Sixth Month, the Last Day, Evening for illustrations of the various utensils that Rikyū used, as well as other details of that occasion. The URL for that post is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/183858107433/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-2-42-1587-sixth-month-the

This gathering was likely cited here (as a way to give veracity to his assertioins) because the author of this entry had no other information regarding Rikyū’s activities -- but what could be found in the Nampō Roku itself.

⁹Sono-toki made ha matsu mo nashi, san-bon take ni te kama-kakerare, mizu-chikaki yue, mizusashi nashi ni hataraki tamau nari, chakin kama no futa ni okare-shi-koto wo, aru hito toi-keru ni, kono ichi-e no kokoro ha sayō no koto ni te ha nashi [其時マデハ松モナシ、三本竹ニテ釜カケラル、水近キユヘ、水サシナシニハタラキ玉フ也、茶巾釜ノフタニヲカレシコトヲ、アル人問ケルニ、コノ一會ノ心ハサヤウノコトニテハナシ].

Though it would have been easy to divide this very long sentence into several separate footnotes, I hope my reasons for dealing with it as a unit will become clear as you read the commentary.

Sono-toki made ha matsu mo nashi [その時なでは松もなし] means “up to that time, if there were no pine trees (from which the kama could be suspended)....”

San-bon take ni te kama-kakerare [三本竹にて釜懸けらる] means “the kama may be hung from three lengths of bamboo.”

A structure like this had been used since ancient times to create stands for kagari-bi [篝火] (garden lights -- the word is sometimes translated garden torches or garden flares -- consisting of a metal basket filled with burning brushwood). While this basket was placed in the crotch above the three poles, here the kama was suspended below them, with the fire kindled in the middle of the tripod. This was probably the first way that the kama was arranged for no-gake (hence its name) -- with the kama being suspended from a pine tree appearing much later (it is certainly possible that the episode at Daizenji-yama mentioned above was the first such occasion for this arrangement).

Mizu-chikaki yue, mizusashi nashi ni hataraki tamau nari [水近いゆえ、水指なしに働き給うなり] means if water (is flowing) nearby, it is said that you can do things without a mizusashi....”

Chakin kama no futa ni okare-shi-koto wo [茶巾釜の蓋に置かれしことを] means “...in which case the chakin should be placed on the lid of the kama.”

Aru hito toi-keru ni, kono ichi-e no kokoro ha sayō no koto ni te ha nashi [ある人問けるに、この一會の心業ようのことにてはなし] means “when a certain person asked about this, (questioning) the thinking behind the way things were done at this one gathering, with respect to that (matter)*, (he suggested that) it should not have been done.”

In other words, this person has taken offense, since he believed that placing the chakin on the lid of the kama was something that should only be done when that chakin would not be used again (in other words, when the chakin was being “thrown away” -- as per the arguments made in entry 64). Yet on this occasion, when there was no mizusashi, Rikyū placed the chakin on the lid of the kama over the course of the whole temae. That is, the quisitor is implying that Rikyū either made a foolish mistake, or was being disrespectful of the proprieties. In the Enkaku-ji version of this story, Rikyū does not actually make any reply.

Shibayama’s text is the same except for the final phrase in this sentence. His toku-shu shahon ends the sentence: aru-hito toi-keru ni, kono ichi-e ni oite ha susugi-kiyomuru-koto cha-gu nomi narazu [或人問ケルニ、此一會ニ於テハスヽキ淸ムルコト茶具ノミナラズ]. So, rather than questioning why the chakin could be placed on the lid of the kama throughout the temae, here his interlocutor seems to be asking about the matter of purifying the utensils (the chawan, chakin, and chasen) by rinsing them in water. To this comes the reply (whether from Sōkei or Rikyū is not clear in this version): “it is not only the utensils that should be rinsed so they are pure†.” (Implying that the idea of purity extends also the the mind of the host and his guests.)

However, here Tanaka’s genpon text developes this idea even further. The whole sentence that we are considering in this footnote is given as follows: sono-toki made ha matsu mo nashi, san-bon take ni kama kakeraru, mizu chikaki yue ni, mizusashi nakereba, chakin wo kama[-no-]futa no ue ni oku wo tori-mama kama no futa ni okaruru, sono shisai toi-bito ari, Kyū no iu, kono ichi-e ni oite, susugi-kiyomuru-koto, chagu nomi narazu [其時マデハ松モナシ、三本竹ニテ釜カケラル、水近キ故ニ、水指ナケレバ、茶巾ヲ釜蓋ノ上ニヲクヲ取マヽ釜ノフタニヲカルヽ、其子細問人アリ、休ノ云、コノ一會ニ於テ、スヽキ淸ムル事、茶具ノミナラズ].

This means: “if, on that occasion, there were no pine trees, the kama would be hung from three lengths of bamboo; and if, because [flowing] water is [available] nearby, and so a mizusashi has been dispensed with, the chakin is placed on the lid of the kama, used as it is‡, and then put back on the lid of the kama [afterward]. Someone asked about the details of this, to which [Ri]kyū replied: ‘in this particular gathering, with respect to the matter of purifying [the utensils] through rinsing [them], it was not only the things that were used to prepare tea [that were so purified].’”

Rikyū’s explanation seems to be that it is not only the utensils that should have been cleaned, but also the minds of the host and guests as well. When their minds have been purified, they are no longer contaminated by the dust of the world. So, being pure, they perceive the world as pure -- thus, for such people, the question of purity and defilement ceases to exist. The lid of the mizusashi is not especially pure, nor is the lid of the kama unclean**. Both are extensions of this pure world, so the lid of the kama will be as pure as everything else.

__________

*The reference seems to be to using water dipped from the stream, in place of a mizusashi.

The actual thinking is unclear, but the author appears to have been misinformed about Rikyū’s evening chakai in the Tadashi-no-mori, if that is the fusube-chakai to which he is referring -- because, for whatever reason, Rikyū chose to bring the water in a sugi-teoke, rather than dipping it out of the stream, and so used the sugi-teoki as his mizusashi during that gathering.

As explained in the previous footnote, this stream is rather small, and flows through the shrine before passing through the Tadasu-no-mori (and eventually being discharged into the Kamo River at the end of the little peninsula on which the shrine is located). Thus, Rikyū may have felt that the water in the stream would not be especially pure (in that time it was not unusual for men to urinate freely into any stream or gutter when necessary, which is why residences in Kyōto erected arching bamboo grates along their street-facing walls -- to keep men a safe distance away -- since urine would cause the plaster to break down).

Furthermore, as was also mentioned above, he may have felt that exposed water becomes charged with poisons after dark, making it unsafe to use regardless of the civic-mindedness of the local population. (The water in the sugi-teoke would have been drawn at dawn; and the cryptomeria wood from which the bucket was fabricated was understood to be purifying of the contents as well.)

That all being said, the point appears to be that the author of this entry imagined that Rikyū did not use a mizusashi on that occasion, and so placed the chakin on the lid of the kama throughout the whole temae -- and it was this behavior that the quisitor was rejecting (phrasing his objection as a question).

†Implying that the purity of the utensils should be our least concern (even though they should be spotlessly pure as a matter of course). The importance of a pure heart is one of the central themes in writings about chanoyu theory, an aspect of chanoyu that was being emphasized during the first half of the Edo period, in the wake of Taku-an Sōhō’s teachings on the relationship between Tea and Zen.

At this point in his commentary, Shibayama directs our attention to the text of the original entry (cited above under the introductory notes) in Book One, which reads, in part: shu-kyaku no kokoro mo sei-jō keppaku wo dai-ichi to su iu-iu [主客ノ心モ淸淨潔白ヲ第一トス云〻]. This means “with respect to the hearts of both the host and (his) guests, it is said that they should be pure in both thoughts and deeds” (please refer to the discussion of sei-jō keppaku [淸淨潔白] in footnote 3, above).

Furthermore, he goes on, in entry 19 in the Sumibiki no uchinuki-gaki・tsuika [墨引之内拔書・追加], it says: chakin, chasen ika ni mo mizuke no sawa-sawa to miyuru-yō ni shite iu-iu [茶巾、茶筌イカニモ水ケノサハサハト見ユル様ニシテ云〻]. This means “as for the chakin and chasen, always make them appear fresh and clean [by rinsing them] with water -- so it has been said.”

‡More literally, tori-mama kama-no-futa ni okareru [取りまま釜の蓋に置かれる] would mean taken up as it is, and (then) placed on the lid of the kama (afterward). In other words, in the absence of a mizusashi, the chakin is placed on the lid of the kama at the very beginning of the temae (when the host is emptying the chawan of the chasen and chakin, in preparation for the first rinsing and chasen-tōshi), and then taken up from there (when it is needed to dry the chawan) and returned there afterward.

Again, this is describing the temae in Sen family terms (where the lid was handled with the bare fingers). In Rikyū’s temae, as has been explained before, the chakin was used to protect the fingers when lifting off the hot lid, and then rested on the lid immediately.

But this would then raise the question of what to do with the chakin when the lid of the kama was closed (during the chasen-tōshi) so as to heat the water fully in anticipation of the preparation of koicha. Of course, in the case of the evening chakai in the Tadashi-no-mori that is cited as an example, Rikyū used a sugi-teoki as his mizusashi (rendering this question moot); but in the absence of a mizusashi -- such as when Rikyū was called upon to spontaneously spontaneously serve tea during Hideyoshi's outing to Daizenji-yama -- perhaps Rikyū only served usucha (which would make the closing and reopening of the lid of the kama unnecessary). Indeed, during such an outing (which was probably for hawking, one of Hideyoshi’s favorite outdoor activities), koicha would have been inappropriate, since the idea was to quench Hideyoshi’s thirst -- which would account for Hideyoshi’s impressed surprise at the way Rikyū chose to do things (and why he subsequently called out for “fusube-chanoyu” on other occasions of the sort).

**This idea that the lid of the kama is inherently unclean appears to be unique to the machi-shū tradition espoused by the Sen family (I have heard it said there, but it is not included in the teachings of those schools that do not have such a connection). As was explained in entry 64, Rikyū used the chakin to protect his fingers when opening the lid of the kama, and it remained resting on the lid until it was time to close it again. This was the gokushin way of doing things -- and this established the precedent that he used on occasions when there was no mizusashi.

¹⁰Isshin no sho-i ni shite, te-waza no shōji ni arazu, mazu yoku-tanren no ue, monjin-serare-yo to no tamau [一心ノ所爲ニシテ、手ワザノ小事ニアラズ、先能煆煉ノ上、問訊セラレヨトノ玉フ].

Sho-i [所爲] means an action, a deed. So isshin no sho-i ni shite [一心の所爲にして] means to do something with one’s whole heart*.

Te-waza no shōji ni arazu [手業の小事にあらず]: te-waza [手業] means something that is done with one’s own hands (i.e., a physical effort); shōji [小事] means trivial, insignificant. So, “what we do with our own hands is not unimportant.”

When we do something wholeheartedly, our actions can never be trivial: even the most insignificant gesture will be full of power.

Mazu yoku-tanren† no ue, monjin-serare-yo to no tamau [先ずよく鍛練の上、問訊せられよとの給う]: mazu [先ず] means first, right away; yoku-tanren no ue [よく鍛練の上] means advanced beyond a state of mastery‡; monjin-serare-yo [問訊せられよ] means (you) should question (your own capabilities); to no tamau [との給う] means (this teaching) has been handed down (to us).

Here, Shibayama’s and Tanaka’s texts include only the first phrase (isshin no sho-i ni shite [一心ノ所爲ニシテ]), after which they launch off in a different direction (their version -- which is discussed in footnotes 11 and 12 -- has been included in the translation of the entry, enclosed in doubled brackets).

__________

*Shibayama argues that this is the main idea that underpins the (successful) staging of a no-gake no chakai.

Here he again quotes from entry 32 in Book One to support this contention: shutsuri no hito ni arazu shite ha nari-gatakaru-beshi [出離ノ人ニアラズシテハ成ガタカルベシ] -- which means, “if one is not [like] a person who has renounced the world, aspiring to [stage a no-gake no chakai] should be all but impossible.” This reflects the state of chanoyu theory (which developed in response to Takuan Sōhō’s teachings, as discussed above) that was popular among the machi-shū followers of the Sen family around the end of the seventeenth century.

†In the entries that were written by the author of the present section (who appears to have been affiliated with the Sen family’s machi-shū tradition of chanoyu), tanren [鍛練], which refers to training or discipline (in the sense of one’s level of skill or mastery of the practice), is invariably written tanren [煆煉]. The reader should be careful, therefore, when approaching the original texts, because this unrecognized variant may prove confusing (since most dictionaries do not recognize the equivalency between these two written forms).

‡In other words, once we have mastered everything (at least at our level), we should immediately look back and reflect on our attainments, questioning whether we truly understand.

This reflection and self-criticism was considered especially important around the time that this entry was written (in the late seventeenth century).

¹¹Hito-bito no kokoro tomo ni aka ha aru-majiki ni, sono fushin dai-no-kegare nari [人〻ノ心共ニ垢ハアルマシキニ、其不審大ノケガレナリ].

This and the following sentences (footnote 12) are found only in the toku-shu shahon and genpon versions of the text.

Hito-bito no kokoro tomo ni aka ha aru-majiki [人々の心ともに垢は有るまじき] means the hearts of all people should not be sullied.

Sono fushin [その不審] means to be ignorant of that (principal)....

Dai no kegare nari [大の穢れなり] means (this ignorance is) a grave disgrace.

¹²Ji ni okite mo kegare ha naki hazu no shōjō-shin ni nari-sōrō ha de ha, kono ichi-nen no kokoro ha satori muzukashigaru-beshi to iu-iu [地ニ置テモケガレハナキ筈ノ淸淨心ニナリ候ハデハ、此一念ノ心ハ悟リ難カルベシト云〻].

Again, this sentence is found only in the toku-shu shahon and genpon texts. However, these two versions differ in their second phrases.

Ji ni okite mo kegare ha naki hazu no shōjō-shin ni nari sōrō ha [地に置きても穢れはなき筈の清浄心になり候は]: ji ni okite [地に置きても] means even if (it)* is placed onto the ground; kegare ha naki hazu [穢れはなき筈] means it will not be expected to become sullied; shōjō-shin ni nari-sōrō [清浄心になり候] means if the heart has been purified†.

De ha [では] means then, therefore, to my mind, in my opinion, as for, in which case, and so forth. In other words, the second phrase derives from, or is an exposition of, the first.

Shibayama’s version continues: ono ichinen no kokoro wa satori nan karubeshi to iu-iu [この一念の心は悟り難かるべしと云〻], which means “the mind of this single nen [念]‡ is difficult to comprehend.”

As suggested abover, Tanaka’s genpon text differs in the second phrase of this sentence, which reads: [コノ一會ノ心ハ悟リガタカルベシト云也、大和尚モ一座感心不斜、同人口ヲツグム].

Kono ichi-e no kokoro ha satori-gatakaru-beshi to iu nari [この一會の心は悟り難かるべしと云うなり] means the mind of this one gathering is difficult to understand, so it is said. (This is because, as argued above, only a man of pure mind will be able to stage a no-gake no chakai successfully**.)

Dai-oshō mo ichi-za kanshin naname-narazu [大和尚も一座感心斜めならず] means it is extraordinary when even a group of great monks are all moved to admire (something). In other words, even people who are supposed to be enlightened will not be uniformly impressed by something, regardless of how moving it might be to others of them.

Dō-jin kuchi wo tsugumu [同人口を噤む]: here, dō-jin [同人] seems to mean the other people (whether the other monks, or the other guests if there were any) should keep quiet.

The guests should not argue among themselves. They should accept the host’s arrangements in the spirit in which they were done.

__________

*Whether the author intended this “it” to refer to the utensils, or to the heart of the host, is unclear.

†Perhaps more literally, “if the purified heart has come into being.”

It appears that the argument being made here is that only a person who is profoundly enlightened will be able to stage a no-gake no chakai with any hope of success. And it is only persons of the same sort who will be able to appreciate the host’s efforts fully.

This is a manifestation of the Edo period mentality that chanoyu was so mysterious that it was simply beyond the imagination of mere mortals -- hence the need for careful and deliberate guidance from the professional masters, who were the living embodiment of Rikyū’s spirit.

‡In Buddhist theory, a nen [念] is a single unit of thought. Our perception is based on our interpreting the series of nen that continue to flow incessantly (perception requires that the original nen is observed, and then analyzed; and it is this analysis that we understand to be experience -- even though it is two nen removed from actuality). For this reason, it is said that it is impossible to comprehend a single nen. And if that is so, how much more difficult will it be for us to fully understand something so long in time as a full chakai?

According to this way of thinking, samadhi is the direct experience of the flow of nen -- without the intervening analysis.

**Though the reason is not really explained in this entry, it is because this kind of gathering is performed out-of-doors. Since there are no physical walls to keep the minds or attention of the guests from wandering, it is exceptionally difficult to maintain the sort of tension that holds an ordinary gathering together.

Modern chajin occasionally use the kō-haku no maku (the red-and-white striped curtains that are hung up on the periphery of the area where the chakai will be staged) in an effort to create a sort of chaseki, but this was really not their original purpose. Rather, their purpose was to close off a large area (at Daizenji-yama, the enclosed area was the same length as, but somewhat wider than, a regulation soccer pitch or football field; while in the pine barrens at Hakozaki, it was 4 to 5 times larger -- and the curtains would be all but out of sight of the guests who were participating in the chakai), so that anyone who was not associated with the gathering would be unable to approach (whether out of curiosity, or for more nefarious purposes).

This is why, for example, in entry 31 of Book One, Rikyū is quoted as saying:

keiki ubawarete chakai shimanu-mono nari, besshite kyaku no kokoro motomaru-yō ni suru hon-i nari, sore-yue, dōgu mo besshite hizō-no-chaire nado yoshi

[景氣ニウバヽレテ茶會シマヌモノ也、別而客ノ心モトマルヤウニスル本意也、夫故、道具モ別而秘藏ノ茶入ナドヨシ].

This means “if the [beauty of the] scenery is overpowering, the chakai will be unable to maintain its grip [on the guests’ interest]. Therefore [the host] should make an especial [effort] to try to catch the guests’ attention -- this is the real reason [for everything that the host attempts to do]. Consequently, with respect to the utensils, it is better to [use] a greatly treasured chaire, or other things of that sort”.

¹³Asa-asashiku kono-bō nado no e-toku ni te tsukamatsuru-beki koto ni arazu [淺〻シクコノ坊ナドノ會得ニテ仕ルベキコトニアラズ].

Asa-asashiku [淺〻しく] means extremely shallow (in this case, referring to the Nambō Sōkei’s understanding).

Kono-bō nado [この坊など] would be translated “this monk, and the others...,” “this monk, among other people...,” or perhaps “this monk, as well as the other people....”

The unnamed “others” being the expected readers of the book (those with enough experience of chanoyu that they would be able to begin to doubt their own level of competence -- as discussed in footnote 10).

Consequently, asa-asashiku kono-bō nado no e-toku ni te [淺〻しくこの坊などの會得にて] means “in the case of the understanding of this monk, and others....

Tsukamatsuru-beki koto ni arazu [仕るべきことに非ず] means “(it) will not serve (to allow us to stage a no-gake no chakai -- at least without assistance).”

Of course the point is to discourage “ordinary people” (including those who had gotten all of their menjō [免状]) from attempting to do so, especially by themselves. It was from this time that the practice of asking one’s teacher, or his or her senior disciple, to help in the katte began to become common -- since no one could presume to do things by himself. Indeed, the training offered by the modern schools dictates that a tea gathering -- whether for a small group of guests, or an ō-yose-chakai where a number of separate seki will be held over the course of a day (or longer) -- must always be a group effort. The host (no matter how experienced) should never attempt to do it completely without assistance.

==============================================

❖ Appendix: Tanaka Senshō’s Thoughts on this Entry.

“In the preceding entry, the issue of discarding or not discarding the chakin [by placing it on the lid of the kama] was raised. This is something connected with the worldly practices associated with the daisu. But, following from [the idea of] cha-zen ichi-mi [茶禪一味]¹⁴, we must realize that this world [of wabi no chanoyu] is [inherently] pure and unsullied.

“[To say] the top of the lid of the mizusashi is clean, and the lid of the kama is unclean, this is a reflection of relativistic thinking¹⁵. The entire roji [including the setchin] is uniformly pure. Isn't it like Ikkyū oshō’s saying: ‘exposing the crack of your buttocks in the bath, how can we speak of clean or dirty?¹⁶’ -- isn’t this so?

“In the roji, we handle the zōri that we wore on our feet [with out bare hands¹⁷]. We put our hands on the surface of the tatami when we perform our bows. And then we pick up the chakin with the same hands, and [with those same hands] we prepare the tea.

“In this pure world [of the roji and tearoom] there is nothing that is unclean. Yet the mind that thinks about impurity -- isn’t that mind already defiled? The heart of that person who asked [about the propriety of placing the chakin on the lid of the kama when serving tea out-of-doors without a mizusashi]: is this not evidence that dust was already clinging to his heart? Rikyū's stern reply¹⁸ impressed everyone who was present; but as for the quisitor, he should have kept his mouth shut.

“A very interesting story, isn’t it¹⁹?”

_________________________

¹⁴Cha-zen ichi-mi [茶禪一味] means both tea and zen have the same flavor. In other words, in essence, they are the same.

¹⁵Ni-ken [二見] is a Buddhist term that refers to contrasting or dualistic ideas: transience versus permanence, existance versus non-existance, purity versus impurity, and so forth.

¹⁶People often quote Ikkyū as saying “nothing is pure, nothing is dirty” (or words to that effect), but here the words are put into their original context.

¹⁷Today a piece of kaishi is held between the fingers and the strap of the zōri, but it seems that this practice arose only during the early 20th century, at the time when chanoyu was being codified in minute detail -- in anticipation of the arrival of hoards of young women who would be forced into the practice by their parents (to make them “more marriageable”). Since one of the rules they were being taught was to always be clean, the traditional way of handling the zōri with the bare fingers begged to be “corrected.” Hence the idea of using a piece of kaishi, for protection (since the hands cannot be washed afterward, because the person is at that moment entering the tearoom).

¹⁸This is referring to footnote 9, where the genpon text reads (in translation): “if, on that occasion, there were no pine trees, the kama would be hung from three lengths of bamboo; and if, because [flowing] water is [available] nearby, and so a mizusashi has been dispensed with, the chakin is placed on the lid of the kama, used as it is, and then put back on the lid of the kama [afterward]. Someone asked about the details of this, to which [Ri]kyū replied: ‘in this particular gathering, with respect to the matter of purifying [the utensils] through rinsing [them], it was not only the things that were used to prepare tea [that were so purified].’”

As explained under that footnote, the idea seems to be that it is not only the chawan, chakin and chasen that have been rinsed clean, but also the kama and its lid, too*. That is why the chakin can be placed on the lid with impunity, and why it can be used and returned (and used again later) without the host having to continually refold it.

__________

*Though here Tanaka seems to be considering purity as less a physical state than an intellectual one. In other words, he implies that the lid of the kama is pure in the same way as the entirety of the roji is pure (including the toilet) -- whether or not the host has specifically rinsed it.

While it was usually the custom not not wet bronze lids (because, depending on the pH and/or mineral content of the water, it could sometimes cause the bronze to become discolored, leaving spots or corrupting its color or patina), the small unryū-gama that Rikyū was carrying around with him had an iron lid, and this lid was rinsed along with the kama when it was being prepared for use.

¹⁹The complete text of his comments is as follows:

Zen-jō ni oite, chakin wo sutsuru-sutenu no mondai ga atta. Kore ha seken-teki no daisu shikkō no koto de aru. Shikaru ni, sude ni cha-zen ichi-mi no ue ni oite ha, shōjō-muku no sekai wo satoraneba naranu. Mizusashi no futa no ue ga sei-ketsu ja no, kama-futa no ue ha fuketsu ja no to ni-ken ni watarite ha naranu. Ichi-yō no haku-roji de aru. Ikkyū oshō no ‘shiriatama wakete miyokashi furo no naka, kiyoshi kitanashi iu koto mo nashi’ de ha nai ka. Roji de ha, ashi ni haku-zōri wo sashi de tsumu. Tatami no ue ni te wo tsuite o-jigi wo suru. Sono-te de chakin wo tsumi, cha wo tateru. Kono seijō-sekai ni fu-jō ha nai hazu ja. Fu-jō nari to omou-kokoro ga, sude ni kokoro no kegare de ha nai ka. Sa-yō na shitsu-mon wo suru hito no kokoro ha, sude ni hokori ga fuchaku-shite-iru shōko ja to, Rikyū no te-kibishii kotae ni, ichi-za mina kanshin shita. Toi-sha mo mata, kuchi wo kanshita to. Omoshiroi hanashi de ha nai ka.

[前条に於て、茶巾を捨つる捨てぬの問題があつた。是は世間的の台子執行の事である。然るに、既に茶禅一味の上に於ては、清浄無垢の世界を悟らねばならぬ。水指の蓋の上が清潔ぢやの、釜蓋の上は不潔ぢやのと二見に渉りてはならぬ。一様の白露地である。一休和尚の「臀頭分けでみよかし風呂の中、清し汚し云うこともなし」ではないか。露地では、足に履く草履を指で摘む。畳の上に手をつぃて御辞儀をする。其手で茶巾を摘み、茶を点てる。此清浄世界に不浄は無い筈ぢや。不浄なりと思ふ心が、既に心の污れではないか。左様な質問をする人の心は、既に塵埃が付着して居る証拠じゃと、利休の手厳しい答えに、一座皆感心した。問者も亦、口を緘したと。面白い話ではないか].

0 notes

Link

Nishinoumi Kajirō II (西ノ海 嘉治郎, February 6, 1880 – January 27, 1931) was a sumo wrestler. He was the sport's 25th yokozuna.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Unryū-in 雲龍院 by Patrick Vierthaler

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

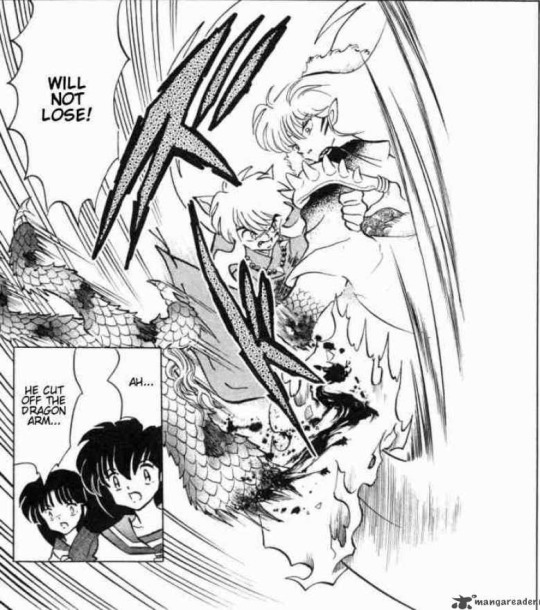

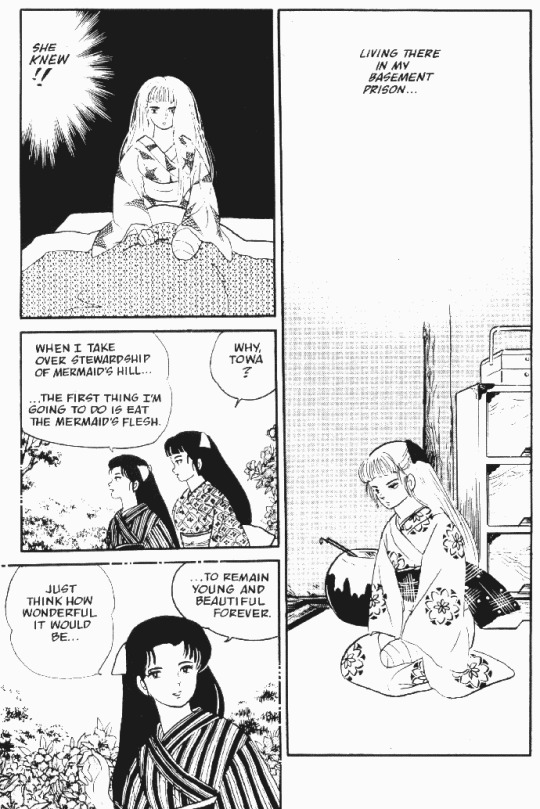

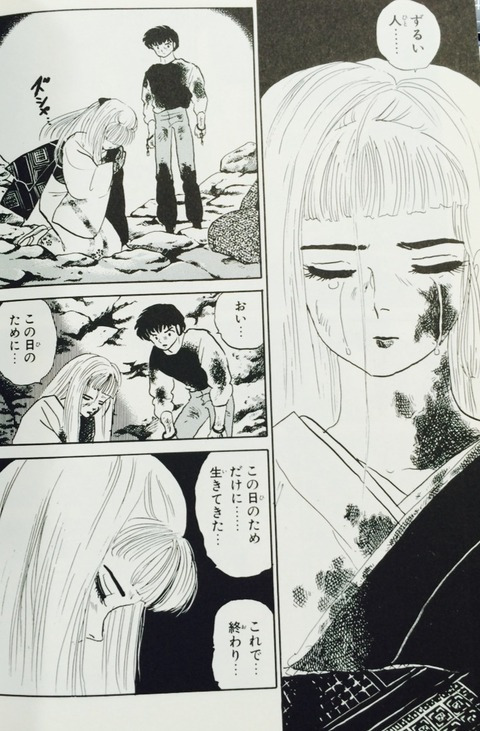

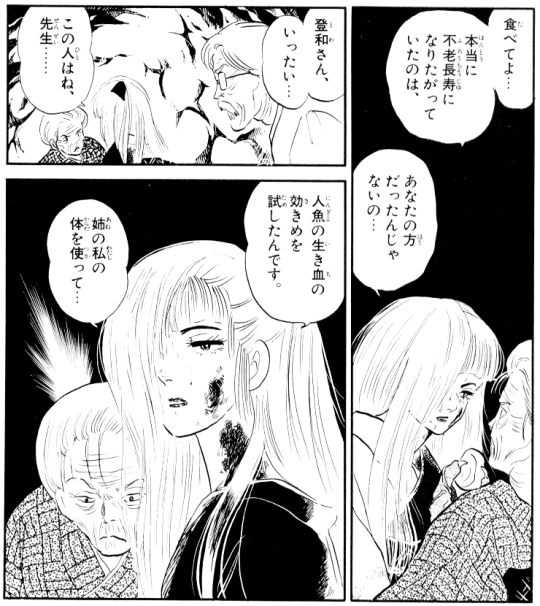

‘Tōwa,’ & Rumiko Takahashi’s Twin Sets

Tōwa

I shalln't spill the beans on everything I have in mind with regards to this topic, such as headcanon, theories, or my fanfic outline. However I wanted to try and being among, if not the very first, to throw this discussion topic out there and go through it.

Just as InuYasha’s animation company Borrowed the Name of Ayame from another of Rumiko Takahashi’s Work Kyōkai-no-Rinne, “Ayame Sakaki,” too is Sunrise utilizing another name-sake here “Tōwa Kannagi,” from the Mermaid Saga’s Mermaid Forest for their ‘YashaHime Tōwa’/‘Tōwa Higurashi,’ in the fan-titled/fan-renamed/fan-dubbed ‘YashaHime FanFic.’

[[ Skipping of the Kanna rōmaji and humanoid likenesses between Kannagi and InuYasha’s Kanna, which I will not deny and fully point to this in a whole other matter for which I can placate on.]]

[[ And Yes, I am quite openly acknowledging that there is a very commonly distinguished ‘character mold' problem particularly common in most long-term companies, corporations, and franchises, which produce a high number of animations or characters. Both Rumiko Takahashi’s character designs and many mainstream works out there have their similarities and differences. Such a Mermaid Saga’s universal likeness between Mana of both anime and manga toward manga Kagome Higurashi, anime and manga Kikyō, and the fourth movie’s character ‘exclusive,’ Kikyō Clone of HōraiJima. This can easily be compared to the concept of the long term Barbie Mold, or Disney Princesses (especially pre-3D, [however, in some instances this also applies far more to the 3D Princesses than to some openly out-going character designs that aim for unique looks of individuals such as Pixar]).

I also have my own plots regarding this type of thing with a similar line of connections to the Series of Rumiko and the Feudal Era in the openly approved “Disney [Princess(es(’))] Connection Theory.”]]

Kannagi already had some slight likenesses to the Inu in the original stories. They both start out as a white haired individuals, of which we also see YashaHime’s Tōwa predominantly Shares the majority of the time whence in her HanYōkai form.

However, Tōwa Kannagi’s character development also includes her becoming a supernatural being referred to as a ‘Deformed One,’/‘Lost Soul,’ which including immortality to compare to Sesshōmaru’s longevity. This is also followed by the mutation of an abominable right arm as the highlighted parallel between these too, as Sesshōmaru lost his left arm and has on at least one location had a green arm with talons used for a duration ahead of ‘succumbing,’ to a mortal arm in order to wield a certain anti-full-breed/anti-full-fledged Yōkai sword intended to protect humans/mortals.

IF memories serve, just a Kannagi’s finger count varies depending upon the iteration- Manga being three fingered, animations with five; so too, I believe, was Sesshōmaru’s finger count for that particular arm he temporarily acquired from another, Being 3 fingers in the manga and having actually remained consistent to this in animation more so than Mermaid Saga’s.

Carry the lot of this on over to the small collection of likenesses when comparing Tōwa Kannagi to YashaHime’s Tōwa, and we will see that they both have a primarily human/mortal character mold, and both are twins to an “S,” begining and “a,” ending. Tōwa Kannagi twin to Sawa and YashaHime’s Tōwa twin to Setsuna. In Mermaid Forest, Tōwa is seen originally with dark hair in her ‘human,’ state-- relating that her change to the supernatural, like YashaHime’s also is the cause of whiter hair.

[[Perhaps there is a good reason to begin mentioning how things could have influenced eachother. Such as the Tokyo Ghoul Twins Kurona and Nashiro, where the latter also turned into a white hair twin in the change, while the former remains dark haired.

Or Haji of Blood+, who upon having the Chiropteran Queen Blood of Saya becomes a Chevalier with his right hand also transformed like Mermaid Forest’s Tōwa?

How Mermaid Forest’s Tōwa has her path chosen for her by her sister, just as Shizuka Hiō has her future determined in a betrothal to Rido Kuran, and they share “Hime,” hair-cut style and traditional simplistic Kisode / Kimono attire. ]]

[Update: I also just realized Akari Unryū has the hair stripes in the likeness to these Inu Twins, especially Setsuna’s! ]

#First Post#First Note#First Tumble#Rumiko Takahashi#Sunrise#Anime Company#Sunrise Studio#Anime Company Sunrise#Name Borrowing#Name-Borrowing#Character Comparison#YashaHime#Mermaid Saga#Mermaid Forest#Sesshomaru#Towa Kannagi#Towa Higurashi#Sesshoumaru#Touwa Kannagi#Touwa Higurashi#Sesshomaru Sotokai-Taisho#Towa Taisho#Towa Sotokai-Taisho#Sesshoumaru Taishou#Touwa Taishou#Sesshoumaru Soutoukai-Taishou#Touwa Soutoukai-Taishou#Twins#Long Post#Mermaid

26 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kinryū & Unryū | © Manabe Hisanori

#japan#nature#autumn#fall#adventure#scenery#photography#dragon#forest#landscape#garden#kyoto#asia#nihon#hky#beautiful#pretty#pastel#maple#leaves#lake#river#aesthetic#grunge#indie#hipster#boho#inner dialogue: damn that photography skills. beautiful shots!

94 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Panneaux “Unryū-zu” - Dragon and clouds de

Soga Shōhaku 曾我蕭白 (1730 - 1781).

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

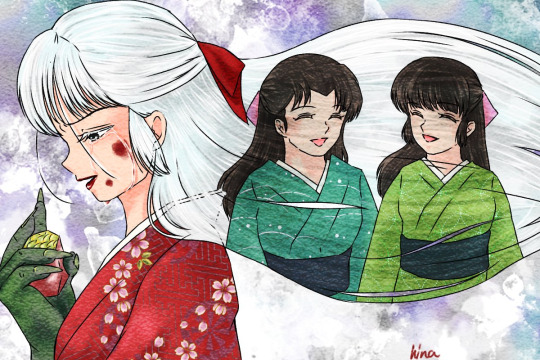

Iron Tiger Forge – Cloud Dragon Katana with Rayskin Scabbard

The Iron Tiger Forge Cloud Dragon Katana features in brilliant detail the Unryū sky dragon among an elevated koshirae setting and a lacquered rayskin saya scabbard. The blade is hand forged from 1095 high carbon steel and has been differentially tempered using the traditional clay tempered technique, as evident by its genuine hamon which was carefully shaped into the form of billowing clouds along the length of the blade edge. A fine finishing polish to the blade highlights the natural beauty of this hamon of hardened steel and its genuine geometric tip yokote.

The finely cast tsuba, fuchi and kashira hilt components are crafted from antiqued brass, with detailing picked out in gold and silver. The habaki is brass and its surmounted seppa are fine copper. The wooden tsuka grip is inlaid with panels of genuine rayskin which is bound in well-knotted tsuka ito cord. The companion saya scabbard to the sword is carved from wood and overlaid thoroughly in high quality samegawa rayskin. Its speckled effect was created by filling in the low portions of the rayskin with a glossy black lacquer, and the polishing the raised rayskin flush with the lacquer for a unique appearance which is painstaking to achieve, but a beauty of traditional craftsmanship. The quality of this saya work is matched with a koiguchi, kurigata and kojiri of polished buffalo horn. A sageo cord of black and red-flecked silk completes the saya.

Included with the sword is a brocade-bound display and gift box which comes complete with a traditional wood-boxed sword maintenance kit. A cloth sword bag is also included.

Please Note: The design and color of the brocade cloth of the display / gift box may vary.

#Kult of Athena#KultOfAthena#New Item Wednesday#Iron Tiger Forge#Cloud Dragon Katana with Rayskin Scabbard#Cloud Dragon Katana#katana#katanas#sword#swords#weapon#weapons#blade#blades#Japanese Swords#Japanese Weapons#Asian Swords#Asian Weapons#Unryū#Unryu#dragon#dragons#new item#new items

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

20190408 Wolkendrachen (unryū) (hier: Japan) https://www.instagram.com/nobbie.weber/p/Bv_J9ETlqiV/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=9wfo3dq1zrod

0 notes

Video

Unryū-in 雲龍院 by Patrick Vierthaler

#Herbst#Herbstlaub#Higashiyama#Japan#Kyoto#Sennnyuu-ji#Sennyu-ji#Sennyuu-ji#Tempel#Temple#Unryu-in#Unryuu-in#Zen#autumn#fall#foliage#momiji#momiji 2018#京都#紅葉#Unryū-in#雲龍院#もみじ#泉涌寺#秋

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some Random Thoughts on the Practice of Chanoyu (13): the Use of the Ro during the Furo Season (Part 2).

The host picks up the chawan, turns toward the shōkyaku, and places the chawan down in front of his own knees (still facing toward himself).

The chawan is then offered to the guest by first placing the dashi-bukusa [出しフクサ] (or ko-bukusa [小フクサ or 古フクサ]³¹) out on the mat that adjoins the utensil mat, and then (after turning the chawan so that it faces toward the guest) resting the chawan on top of the fukusa.

After the shōkyaku takes the first sip, the host should ask him about the taste of the tea.

Since this is the furo-season, the kama remains open from this point on to the end of the temae³², so the host simply backs up slightly and waits for the shōkyaku to finish drinking.

According to Rikyū, the shōkyaku should pick up the chawan and fukusa together and, without turning the chawan at all, drinks all of the koicha. And after inspecting the bowl, he returns the chawan to the host by placing it in the same spot as before (and still facing toward himself³³).

When the guest has finished inspecting the chawan (after drinking), he should put it down (on top of the fukusa) in the same place where the host offered it to him. The host then picks up the chawan, smelling to cha-no-ato [茶の跡] that remains in the chawan to judge the taste, and then he and the shōkyaku exchange words about the tea, and the chawan.

Placing the chawan in front of his knees, the host picks up the hishaku, performs a yu-gaeshi, and then dips a hishaku of hot water from the kama. He pours some (around a quarter of the amount -- enough for 2 sips of tea) into the chawan, and returns the rest to the kama.

Picking up the chasen, the host whisks the hot water with the cha-no-ato into a thin usucha (cleaning both the sides of the chawan and the tines of the chasen in the process). After returning the chasen to the mat, the host picks up the chawan and, turning slightly towards his left, he drinks the contents of the bowl (so the tea will not be wasted³⁴).

Then, after returning the chawan to the mat, he picks up the hishaku and adds a hishaku of cold water to the kama. Following a yu-gaeshi, he dips half of a hishaku of hot water out and pours it into the chawan. Taking another hishaku of cold water from the mizusashi, he pours half into the chawan, and the rest into the kama.

Picking up the chawan, and holding it above the koboshi, the host uses his right thumb to clean any remaining koicha from the sides of the bowl, rotating the bowl through four quarter-turns. Then this water is discarded.

After putting the chawan down on the mat in front of his knees, the host adds a half hishaku of hot water to the bowl, then a full hishaku of cold water to the kama, followed by a yu-gaeshi³⁵. After picking up the chawan, it is rotated above the koboshi three times, and then the water is discarded.

Then the host adds a quarter hishaku of hot water to the chawan (followed by the addition of a full hishaku of cold water to the kama, and another yu-gaeshi). After rotating the chawan three times above the koboshi, this water, too, is discarded³⁶.

After the chawan has been dried with the chakin in the same way described above, the host prepares another bowl of koicha for the remaining guests³⁷.

After the chawan has been returned, it is cleaned in the same way as above -- first with the host drinking the cha-no-ato, and then with the thumb (using a mixture of hot and cold water), and then rinsing two times with hot water. After adding the quarter hishaku of hot water to the chawan, if the host feels it is necessary to refold the chakin, it should be done at this time (then the water is discarded and the bowl dried with the chakin).

In the unryū-gama temae, each time hot water is taken from the kama, it should immediately be replaced by adding one hishaku of cold water to the kama. This is why the largest mizusashi possible (even a kiji-tsurube) was preferred -- even if the host will only be serving tea to two or three guests.

In Rikyū’s temae, once all of the guests had drunk koicha, he served them usucha using the tea remaining in the chaire³⁸. The procedure for cleaning the chawan in between is similar, though there is no drinking of the cha-no-ato after serving usucha, and no cleaning with the thumb at that time either. As a result, the chakin will easily become stained green when serving usucha; and if that is the case, it should be wrung out and refolded before it is used again (each time, if necessary).

When the service of tea is finished, and the chawan has been returned to the host for the last time, he begins by rinsing it using a half hishaku of hot water (followed, as always in this temae, by the addition of another hishaku of cold water to the kama, and a yu-gaeshi).

Then, since no more tea will be made, rather than a quarter hishaku of hot water, the host adds a half-hishaku of cold water to the chawan (pouring the rest into the kama -- cold water should always taken as a hishaku-full -- followed by a yu-gaeshi).

The host then cleans the chasen by means of a second chasen-tōshi -- after which (assuming that the tines of the chasen are actually clean) the chasen is stood on the right side of the mat, as in the beginning.

After the water has been discarded, the chawan should be dried with the chakin, as usual. The chakin should be wrung out at this time, but not refolded (since it will not be used again). It is put directly into the bottom of the chawan, and the chasen rested on top of it.

Then the host cleans the chashaku with his fukusa, taps the fukusa over the koboshi to remove any matcha before returning it to his futokoro, and then rests the chashaku across the rim of the chawan (facing downward). Next he moves the chawan toward the far end of the mat, so that the back side of its foot touches the front edge of the yū-yo.

The host then picks up the chaire and, after taking out his fukusa, cleans it. Then the fukusa is returned to the host’s futokoro, and the chaire placed on the mat in front of the mizusashi, as at the beginning of the temae. The chawan is then picked up and moved to the left of the chaire.

Then the host picks up the hishaku, and dips one or two hishaku of hot water from the kama, which he discards directly into the koboshi (being careful not to drip water on the mat during the long trip from kama to koboshi³⁹).

While holding the hishaku above his left knee (kagami-bishaku once again), the host closes the lid of the kama fully (the lid is now cold, so there is no need to protect his fingers), after which he rests the hishaku on the futaoki. Finally the lid of the mizusashi is closed (after which it is wiped with the fukusa as previously). The utensil mat will now look like what is shown in the above drawing.

It is at this point that the shōkyaku will ask the host for haiken⁴⁰.

After acknowledging the shōkyaku’s request, the host will move the chawan to the lower left-hand corner of the temae-za. Then, picking up the hishaku (and holding it horizontally above his knee line), the host moves the koboshi backwards, and then immediately rests the hishaku on top of it (the cup of the hishaku should not rest on the rim of the koboboshi; rather, it should project beyond the koboshi’s rim as shown). Then the futaoki is picked up and placed in between the chawan and the koboshi⁴¹.

The host then picks up the chaire and moves it onto the adjoining mat. Then he picks up the shifuku, and, together with the chashaku, moves them to rest beside the chaire.