#character analysis of mrs dalloway

Text

i think shippers and romantics are too hated on by normal society because what’s the shame in loving love so much?

i’m so sorry i believe in love and see love and want to write about love and read about love and experience love i should try and be more of a miserable fuck next time like a real clever person

#do i think the dumbing down of romantic love is sexist?#yes i do#i very much do#why is believing characters can love each other always wrong?#why am i not allowed to believe love comes in many forms?#yes this post is about septimus and rezia in mrs dalloway#i cannot fuckign believe other people haven’t made this analysis either#some fucking genuises the lot of you nerds are to not notice colour imagery

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mrs Dalloway Summary, Mrs. Dalloway is a novel by Virginia Woolf published on 14 May 1925. It details a day in the life of Clarissa Dalloway, a fictional upper-class woman in post-First World War England. It is one of Woolf's best-known novels.

#mrs dalloway short summary#mrs dalloway summary#mrs dalloway sparknotes#mrs dalloway analysis#virginia woolf mrs dalloway summary#mrs dalloway plot#mrs dalloway critical analysis#mrs dalloway character analysis#mrs dalloway summary and analysis#mrs dalloway summary pdf#clarissa dalloway character analysis#mrs dalloway synopsis#clarissa and septimus analysis#virginia woolf mrs dalloway analysis#mrs dalloway analysis pdf#mrs dalloway plot summary#mrs dalloway summary and analysis pdf#mrs dalloway chapter summary#summary of the novel mrs dalloway#mrs dalloway cliff notes#mrs dalloway chapter wise summary#critical analysis of mrs dalloway#mrs dalloway critical analysis pdf#mrs dalloway in bond street summary#mrs dalloway said she would buy the flowers analysis#mrs dalloway detailed summary#character analysis of mrs dalloway#virginia woolf mrs dalloway sparknotes#summary of mrs dalloway novel#mrs dalloway book summary

0 notes

Note

If you were to teach a lesson in a creative writing course, what advice would you offer to help writers differentiate literature from stories that seem primed for adaptation into film and television, or from the prevalent cinematic writing style that's hard to avoid? How does a writer encourage a reader to choose books over screens?

I believe you touched upon this in a previous discussion, possibly in reference to your hopes for Major Arcana. I also have a vague recollection of a piece by James Wood on Flaubert, where he highlighted how Flaubert pioneered a particular style of descriptive writing that veered away from traditional literature and leaned more towards the visual. My memory on this is a bit hazy, though.

Yes, in Wood's "Half Against Flaubert" (in The Broken Estate) he criticizes Flaubert for developing of style of pregnantly chosen visual detail that easily coarsens into mannerism (in literary fiction) or formula (in pulp fiction) and that looks forward to film.

I don't think fiction needs to be wholly purified of the cinematic or the dramatic. The novel is always generically impure; trying to purify it can lead to tediously programmatic avant-gardism (cf. the gradual subtraction of the entirety of the world over the course of Beckett's oeuvre). But it can do many things unavailable to cinema and should generally be doing at least one of these:

—fiction can depend for its effect on the style, voice, or character of the narrator as much as or more than even what the narrator describes (novel as performance of voice: Huckleberry Finn, True Grit; novel as unreliable narration: Ishiguro's early books; novel as both: Lolita)

—fiction can compress, telescope, summarize, and therefore proliferate tales beyond what visual media can usually accomplish (Balzac, Kafka, Borges, Singer, Bolaño)

—fiction can dramatize the inner workings of subjectivity and consciousness (Ulysses, Mrs. Dalloway, Herzog, A Single Man, Beloved)

—fiction can be discursive or essayistic, in narrative or in dialogue, and therefore convey many more ideas than visual media can (novel as essay or analysis: The Scarlet Letter, Billy Budd, Death in Venice; novel as Platonic dialogue: Dostoevsky, Mann, Lawrence, Murdoch)

—fiction can encompass every type of verbal media into a stylistic collage that takes on much of the culture or creates an air of authenticity or provokes parodic humor (Dracula, Ulysses, Pale Fire, Possession, Cloud Atlas)

—fiction can offer, even in the midst of visual description, all the pleasures of language itself, whether figuration (metaphor, metonymy) or sound (alliteration, rhythm, even rhyme), and can even be a pure exercise of verbal style (early Joyce, Hemingway, Faulkner, Bellow, Didion, McCarthy, DeLillo)

It's probably at this point less about competing with screens—a lot of people now read on screens anyway—than about setting up feedback loops between screen cultures and literary cultures: for example, what we're doing here.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm not just trauma. I'm also academics.

Zach Reynolds

Dr. Nancy Chase

December 2, 2010

Engl 3040

Analyzing the Tragedy of Septimus Smith

Captured in Mrs. Dalloway there is a reflection of the socioeconomic structure of early 20th century England, as well as the patriarchal class and imperial ideologies that marked this era in British history. The burden a civilization informed by these ideologies puts on its constituents, both its lower and upper class members included, is of focal importance to the novel, because despite its celebrated achievements in psychology and temporal analysis, “it nevertheless incarnates a critique of Empire and the war, taking the state as the embodiment of patriarchal power, and the upholder of what even Richard Dalloway calls ‘our detestable social system’” (Tambling 58; Woolf 116). Central to this critique is the tragedy of the character Septimus Smith, a literary-minded veteran who survives the war only to succumb to the more subtle violence of imperial social ‘justice.’

The portrayal of Septimus’ ambitions, military service, and mental collapse provokes a sharp Marxist criticism of the classist and imperialistic tendencies of early 20th century England, and creates through its criticism an interpretation of this moment in history that is defined by the opposite discourses of Septimus and the aristocracy that drives him to suicide.

When Septimus is first introduced to the reader, he is described as “pale-faced, beak-nosed . . . with hazel eyes which had that look of apprehension in them which makes complete strangers apprehensive too” (Woolf 14). One cannot help but to label him a lunatic immediately following the passage detailing his hallucination of a sparrow chirping his name and singing in Greek, or his vision of “the dead . . . assembling,” with an unknown man, “Evans . . . behind the railings!” (24-25). In the passage that falls between pages 84 and 86, however, a brief biography is given of Septimus Smith, which informs the reader of his disposition before the war. Here, Septimus is made un-extraordinary as one of “millions of young men called Smith” (84), and characterized in his youth as a typical middle class idealist. He is “on the whole, a border case, neither one thing nor the other, might end with a house at Purley and a motor car, or continue renting apartments in back streets all his life . . .” (84). His experiences are summed up satirically in botanical terms, with Woolf imagining that were a gardener to voyeuristically look on Septimus at this early phase in his life, he would say that the young man, consumed with “such a fire as burns only once in a lifetime” with his love for “Miss Isabel Pole, lecturing . . . upon Shakespeare,” and his passion for “Antony and Cleopatra . . . Shakespeare, Darwin, The History of Civilization, and Bernard Shaw”(85) was flowering into a man ardently moved by his reverence for English society and the legacy of art of which his love Miss Pole was the beautiful embodiment.

So, when it came to war, it’s no surprise that “Septimus was one of the first to volunteer. He went to France to save an England which consisted almost entirely of Shakespeare’s plays and Miss Isabel Pole in a green dress walking in a square” (86). The war changes Septimus though. He faces the traumatizing experience of watching his friend die in front of him, yet he stoically does not mourn his friend, Evans, and is rewarded with a wife, a promising promotion in his career in England, and honors for his military service. Yet these things bring Septimus no contentment; the effects of the war on his personality begin to emerge, and he finds upon opening Shakespeare again that what mattered to him before the war, the “business of the intoxication of language – Antony and Cleopatra – had shriveled utterly” (88). Septimus exits the war with his idealism atrophied; but even worse, his connection to civilization is severed:

“He looked at people outside; happy they seemed, collecting in the middle of the street, shouting, laughing, squabbling over nothing. But he could not taste, he could not feel. In the tea-shop among the tables and the chattering waiters the appalling fear came over him – he could not feel” (87-88).

So disillusioned does Septimus become that he no longer can make the association of beautiful Miss Pole to the arts; rather he finds “the message hidden in the beauty of words . . . is loathing, hatred, despair” (88); and “human beings,” he observes, “have neither kindness, nor faith, nor charity . . . They hunt in packs . . . scour the desert and vanish screaming into the wilderness. They desert the fallen” (89). Compared to the idealistic youth who fell in love with Miss Pole, the post-war Septimus is a different person entirely, and suddenly there is an explanation for the lunatic introduced to the reader several pages earlier in the novel with his hallucinations of a man named “Evans.”

Following the detailed deterioration of Septimus’ mind comes his interaction with two different doctors, each a member of the English aristocracy; they are Dr. Holmes and Sir William Bradshaw. Septimus meets with these men at the request of his wife to receive diagnosis and treatment for his nervous breakdown. Coming from the proletariat places Septimus immediately in a position that is submissive to the bourgeoisie doctors Holmes and Bradshaw; it also puts his mental collapse into a context that allows for a Marxist interpretation of how his role in society has caused his neurosis to develop. In Dr. Holmes, Septimus first encounters the discourse of the English aristocracy, and finds to his disgust that it is a language informed by oppressive classist and patriarchal values that are ignorant of or deny the basic emotional needs that, not being met, are at the heart of Septimus’ mental breakdown.

In the passage written from Holmes’ point of view, the Smith’s are portrayed in condescending language that serves to communicate their lesser social rank and Dr. Holmes supposed superiority as a member of the bourgeois. He speaks down to his patient as one would to a child, and invokes the privilege of his rank as a doctor and aristocrat to force his way into the Smith’s home when his entry is refused by Septimus: “Did he indeed?” said Dr. Holmes, smiling agreeably. Really he had to give that charming little lady, Mrs. Smith, a friendly push before he could get past her into her husband’s bedroom” (91-92). In another example, Dr. Holmes belittles Septimus’ illness by telling him that “there [is] nothing whatever the matter” (90) with him, and suggests hobbies he could take up to distract himself, rather than offering any real medical advice. Patronizing Septimus’ illness as mere neuroticism is Dr. Holmes first step to establishing his superiority to Smith. In his second visit, a response to the patient’s talk of suicide, he invokes the patriarchal mores of male programming, and scolds Septimus for giving his wife “a very odd idea of English husbands” (91), implicating him as guilty of failing in both his duties to stoicism and patriotism as a male and a veteran.

In his failure to conform to typical male programming, Erika Baldt sees an applicability of Julia Kristeva’s definition of abjection to Septimus’ situation. Kristeva defines abjection as “the ambivalent, the border where exact limits between same and other, subject and object, and even beyond these, between inside and outside, [are] disappearing—hence an Object of fear and fascination" (qtd. in Baldt 14). Kristeva goes on to say that “at the limit, if someone personifies abjection without assurance of purification, it is a woman, ‘any woman’” (qtd. 14). Therefore, Septimus, for suffering from shell-shock, a form of hysteria, which was considered a feminine “extreme of emotion,” is seen as deviant because he does not comply with the “exact limits” of masculinity, and thus is deemed a “traitor to [his] sex” (Baldt 14). Just from his encounter with Dr. Holmes, then, Septimus is labeled as a deviant and potential threat to society. In addition, implied through the portrayal of traditionally feminine qualities in a male character, there is in the text a discourse of opposition to the biological essentialism that defined gender roles at the turn of the 19th century conflicting directly with a misogynistic and patriarchal discourse that is part of the discourse of the British Empire.

Further critique of the Empire comes out of Septimus’ encounter with Dr. Holmes in regard to the injustice of the war. It is, in fact, the callousness of his society that, internalized in Septimus, has caused his mental collapse – his interior monologue in reaction to Holmes’ insistence that nothing is wrong with him reveals this plainly: “So there was no excuse; nothing whatever the matter, except the sin for which human nature had condemned him to death; that he did not feel. He had not cared when Evans was killed; that was worst . . .” (91). It is this lack of remorse, which, because it is felt at the core of Septimus’ society and has been instilled in him through honors, through decoration as a war hero, that he has his nervous breakdown. This drives his guilt and drives him to condemn himself, and by extension, condemn the society that has instilled in him such callousness. As one critic aptly points out in his analysis, “This kind of satire on the author's part surely reveals the point of the outstanding irony in Smith's continuous self-condemnation of himself for his inability to feel. For it is precisely because he can feel that he is in such difficulty, and at such odds with society” (Samuelson 66). Having witnessed the devastation of war, in particular Evans’ death, places Septimus in the difficult and isolating position of knowing the truth of the war that is denied by the bellicose rationalization of leaders (embodied in Dr. Holmes, and later Bradshaw) who never saw the front line and dictated the terms of the war from the relative safety of their homes. Thus, “Septimus, appalled and revolted by the patriotic lies by which his fellow Londoners transform collective murder into "pleasurable . . . emotion" and himself into a war hero, is diagnosed as mad” (Froula 147).

At his encounter with Sir William Bradshaw, Septimus has worked up to his most vehement critique of his society. “Once you fall,” he says to himself, “human nature is on you. Holmes and Bradshaw are on you. They scour the desert . . . The rack and thumbscrew are applied. Human nature is remorseless” (Woolf 98). Indeed, the conflict between imperial discourse and humane discourse is at its most vehement in this encounter too. It is also worth nothing that the narrator sympathizes strongly with Septimus Smith when, for instance, she criticizes the real motivation behind Bradshaw’s socially celebrated benevolence:

“Sir William would travel sixty miles or more down into the country to visit the rich, the afflicted, who could afford the very large fee which Sir William very properly charged for his advice . . . Her ladyship waited [in the car] with the rugs about her knees . . . thinking . . . of the wall of gold mounting minute by minute while she waited . . .” (94).

The portrayal of Sir William that follows in the remainder of the passage is equally satirizing, invoking Septimus’ discourse of anti-classism and overall cynicism. This becomes apparent again especially when Sir William says that “he never spoke of ‘madness’; he called it not having a sense of proportion” (96). After which he invokes his power as a doctor and knight and makes Septimus’ case a matter of law, ‘prescribing’ him rest and isolation, as per the norm of the medicalized society of early 20th century Britain, when this is actually equivalent to a death sentence for Septimus. For Bradshaw, however, the rest cure – or isolation and quarantine to put it more plainly – is the only recourse for deviant cases such as the Smith case. Though it is disguised, this is actually a reaction of fear; “The discourse of the lunatics, who lack what Sir Bradshaw euphemistically refers to as a sense of proportion, threatens to undermine the strength of the British Empire, already in danger at the historical moment of the novel . . . the insane threaten to contaminate the "sane" who uphold and submit to the order of the Empire” (Smith 18). In other words, the discourse of the “insane” Septimus, who recognizes the impersonal treatment of Evans as a crime, must be suppressed.

Thus, Bradshaw, “worshipping proportion . . . not only prospered himself but made England prosper, secluded her lunatics, forbade childbirth, penalised despair, made it impossible for the unfit to propagate their views until they, too, shared his sense of proportion” (Woolf 99). Just as Septimus views the rest cure as a sentence rather than a treatment, so apparently does the narrator. It is a means used to silence the unruly “lunatic” who questions the established social order and the callousness of his society. This more violent side of proportion the narrator embodies as its sister: “Conversion is her name and she feasts on the wills of the weakly, loving to impress, to impose, adoring her own features stamped on the face of the populace” (100). Calling to mind images of colonialism in Africa, in India, and around the world, the word “conversion” finally sums up Septimus’ and the narrator’s view of imperial England. Through criticizing the figures in the novel who most symbolize the top of the power structure in England, the policies of the English state are criticized, both for their brutality within the country and without.

Ironically, Septimus is condemned by Bradshaw and Holmes not because he cannot feel, but because he feels too much. While the socially prescribed norm values stoicism and blind patriotism, he nevertheless can’t help but to feel repulsed by the lack of humanity in such values. Indeed, “Septimus is in many ways more sane than the "civilized" society to which he returns” (Henry 233). Septimus is not the only character in the novel to recognize his society is insane, however. Speaking of Mrs. Dalloway, Woolf herself states in the introduction to one of the early editions of her novel that “Septimus, who later is intended to be her double, had no existence; and that Mrs. Dalloway was originally to kill herself, or perhaps merely to die at the end of the party” (qtd. in Samuelson 60). Though the two characters never meet, it can be observed that Clarissa does share some of the same emotional qualities that Septimus has, if only to a lesser extent. She knows nothing of the war, and the trauma that it has inflicted on Septimus’ mind, for example, but she shares in his oppression by the patriarchal ideology of imperial England. She expresses her awareness of being so oppressed most keenly with her intense dislike of Sir Bradshaw, judging him “a great doctor yet to her obscurely evil, without sex or lust . . . but capable of some indescribably outrage – forcing your soul, that was it –“ (Woolf 184-85).

Most importantly, Clarissa Dalloway becomes the receiving vessel of Septimus’ message in her empathetic vision of his suicide and death. Faced with confinement, Septimus finally throws himself out of a window before the approaching Holmes can deliver him to Bradshaw for conversion into a yielding imperial pawn through the abuses of the rest treatment. “Lone witness of a reality that everyone around him denies, Septimus . . . suffers, owns, and tries to bear witness to his civilization's "appalling crime" but is finally forced to reenact it through a death that he expects to be read--a death that he offers as a gift, and that the narrative insulates from dismissal as madness” (Froula 149-50). Though he is “pushed” to suicide, Septimus also “jumps” (150). His final act is an act of defiance that through her empathetic vision Clarissa is capable of reading into, and even fantasizing about, before withdrawing back into the insulating world of her upper class marriage and submissive status as Richard Dalloway’s wife. Ultimately, Clarissa can’t die because as a part of the bourgeois, her life is valued more and thus insulated, doubly so because she is a female and deemed feeble by her patriarchal society.

Septimus, on the other hand, is born into the proletariat and is expendable. Even so, the meaning of Septimus’ life is not lost on Clarissa, and more importantly, can not be overlooked by the reader:

“If Clarissa's elegy for Septimus is inadequate to arraign the world before the truths it brands madness, Mrs. Dalloway captures his message within its fictional bounds for the world beyond them. Not Clarissa but we readers receive (or not) the message of Septimus's death, the costs of the war he names a "crime," the measure of what his life means to him, the infinite possibilities of his unfurling days” (151).

Thus, though Septimus exists in an isolated world apart from the superficial reality that every other character in the novel except for him resides in, his tragedy affects them all. Clarissa recognizes how in death, Septimus has preserved through his suicide “a thing . . . that mattered; a thing, wreathed about with chatter, defaced, obscured in her own life, let drop every day in corruption, lies, chatter” (Woolf 184). This thing may be his individuality, which he is unwilling to compromise to the tune of Bradshaw’s idols “Proportion” and “Conversion,” or it may be his message to a future generation to “resist,” to “defy.” Either way, Septimus’ conflict with the society that expels him represents the turmoil of his society as it quietly grieves the catastrophe of the war while stoically denying that it has taken any injury. The discourse of Septimus’ “madness” pitted against that of Dr. Holmes and Sir William Bradshaw in Mrs. Dalloway captures the tension between the patriarchal force of the dying imperial empire and the rising class discontent and interest in socialism in the early 20th century. His tragedy, in addition to questioning the established classifications of sanity and insanity, helps new historians to understand how some of the traditional and subversive discourses of this age in England interacted.

Works Cited

Baldt, Erika. "Abjection as Deviance in Mrs. Dalloway." Virginia Woolf Miscellany 70.(2006): 13-15. MLA International Bibliography. EBSCO. Web. 14 Nov. 2010.

Froula, Christine. “Mrs. Dalloway’s Postwar Elegy: Women, War, and the Art of Mourning.” Modernism/Modernity 9.1 (2002): 125-163. Project Muse. 14 November 2010. Web.

Henry, Holly. "Woolf & The War." English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920 44.2 (2001): 231-235. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 2 Dec. 2010.

Samuelson, Ralph. “The Theme of Mrs. Dalloway.” Chicago Review 11.4 (Winter, 1958): 57-76. JSTOR. Web. 02 Dec. 2010

Smith, Amy. "Bad Religion: The Irrational in Mrs. Dalloway." Virginia Woolf Miscellany 70.(2006): 17-18. MLA International Bibliography. EBSCO. Web. 15 Nov. 2010

Tambling, Jeremy. “Repression in Mrs Dalloway’s London.” Essays in Criticism 39 (April 1989): 137-155. Print Copy

Woolf, Virginia. Mrs. Dalloway. London: Harcourt, Inc., 1925. Print.

#ptsd#trauma#marxism#imperialism#united kingdom#mrs dalloway#virginia woolf#essay#essay writing#research#student#academics#war#shell shocked#complex ptsd#suicide#mental health#New Historianism#literature#literary criticism

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Female Voices in Literature: Celebrating Empowering Women Authors Every Student Should Read

In the rich tapestry of literature, female voices have contributed significantly, offering unique perspectives, compelling narratives, and profound insights. Students need to explore the works of empowering women authors whose words resonate with strength, resilience, and a celebration of womanhood. This article delves into the literary realm, highlighting women authors whose contributions have left an indelible mark on the literary landscape.

Introduction

A. The Importance of Female Voices

The literary world is enriched by its diverse voices, and female authors bring a distinct perspective that deserves recognition. Celebrating these voices is an acknowledgement of their talent and an exploration of the various narratives that shape our understanding of the world.

B. Empowerment Through Literature

The power of literature lies in its ability to empower and inspire. Through their works, female authors empower readers by addressing societal norms, challenging stereotypes, and offering narratives that resonate with women's experiences.

Empowering Women Authors, Every Student Should Read

A. Maya Angelou

Autobiography of a Diverse Life

Maya Angelou's autobiographical works, including "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings," provide a poignant exploration of race, identity, and resilience. Her prose and poetry illuminate the complexities of being a woman of color in America.

B. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Feminism and African Identity

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, with novels like "Half of a Yellow Sun" and "Purple Hibiscus," explores the intersection of feminism and African identity. Her narratives challenge stereotypes while offering a nuanced portrayal of the female experience.

C. Toni Morrison

Unraveling the African American Experience

Toni Morrison's masterpieces, such as "Beloved" and "Song of Solomon," delve into the African American experience, weaving tales of strength, resilience, and the impact of historical injustices on women. Her prose is both lyrical and powerful.

D. Virginia Woolf

Stream of Consciousness and Feminist Perspectives

Virginia Woolf's innovative use of stream-of-consciousness writing in works like "Mrs. Dalloway" and "To the Lighthouse" explores the inner lives of women. Her feminist perspectives and literary experimentation make her a key figure in modernist literature.

E. Jane Austen

Social Commentary and Feminine Agency

Jane Austen's novels, including "Pride and Prejudice" and "Emma," provide insightful social commentary and depict women exercising agency in a society that often limited their choices. Her wit and satire continue to resonate with readers.

F. J.K. Rowling

Empowering Through Fantasy

J.K. Rowling, with the "Harry Potter" series, not only captivates with magical storytelling but also empowers through themes of friendship, courage, and the strength of the female characters like Hermione Granger.

The Impact of Female Voices on Literary Canon

A. Shaping Cultural Narratives

The works of these empowering women authors have played a crucial role in shaping cultural narratives, challenging societal norms, and fostering a deeper understanding of the diverse experiences of women.

B. Expanding Perspectives

Students gain a broader perspective on the human experience by including female voices in the literary canon. Exposure to varied narratives contributes to empathy, tolerance, and a more inclusive worldview.

Integrating Female Authors into Educational Curricula

A. Diverse Reading Lists

Educational curricula should embrace diversity by incorporating works by female authors from different backgrounds and periods. Diverse reading lists contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of literature.

B. Encouraging Critical Analysis

Students should be encouraged to critically analyse the themes, characters, and societal commentary present in the works of female authors. This fosters a deeper appreciation for the impact of diverse voices on literature.

Conclusion

A. The Continued Relevance of Female Voices

In conclusion, celebrating empowering women authors in literature is a nod to their historical significance and an acknowledgement of their continued relevance. These voices continue to inspire, challenge, and shape the literary landscape for future generations.

B. Empowering Readers Through Words

Empowering women authors contributes not only to literature but also to readers' empowerment. Their words have the potential to instil a sense of strength, resilience, and understanding, making them essential reads for every student.

Publish your book now at www.bookalooza.com/newbook

0 notes

Note

thoughts on modernism vs postcolonialism?

tysm for the ask!! so this analysis is primarily derived from the two novels i was talking about, Chronicle of a Death Foretold and Mrs Dalloway, but from what i've read, it seems to be a larger pattern. modernism & post-colonialism are both concerned with both the human condition and the society it's operating in. both genres are very much responding to their historical context. however, modernism's approach is far more aloof – it seeks to eschew typical victorian ideas of characters and plot. it almost seems to be trying to photograph, in its own way, the human condition, or at least a case of it, and developing new experimental styles and forms to do so in the industrial age (not to be confused with traditional realism, however).

conversely, post-colonialism seems to operate with far more urgency. postcolonial literature rarely allows for detachment on behalf of the reader – not to say they necessary bludgeon characters with a hardline moral or message, but rather weave more intrinsic questions / problems / paradoxes into their text which are in a sense placed in the lap of the reader as if to say – you grapple with this social issue.

modernism conversely is primarily concerned with realistically representing society, often through surreal forms (connected to their opinion that the rapidly industrializing world they lived in was itself surreal in many ways – note postcolonial authors have similar concerns of representing a world that is truly surreal in a sense, citation: Gabriel García Márquez's nobel prize speech). however, while modernist literature is more explicitly self-aware and self-conscious (including its characters, who are deeply introspective, and whose thoughts are made explicit alongside imagery and description), post-colonialism is deeply concerned with change and specifically interaction with the reader, rather than the static representation of photography.

this is also why i feel clarice lispector has almost modernist tendencies. as one of the better literary critics on lispector, earl e. fitz, points out, lispector's characters often grapple with language as a means to self-actualize, and often fail, falling into some sort of silence. her novels often follow similar structures – grappling with the form of language in an attempt to represent reality (which also leads to her prose being quite experimental). the novel's failure to do so, to reach that actualization of a reality, is in fact the point of them. fitz points out that lispector's works often (paraphrasing here) focus on positing the world and reflecting on reality as it is.

in comparison, post-colonialism is rarely content to be static. for example, in CoDF, there is a constant paradox the narrator, the town, and the reader are simultaneously grappling with. the paradox isn't resolved, but is enough of a focal point, and has enough direction and a concrete enough form that is explored in the novel, to not simply conclude with a generalized "failure" to resolve the problem.

#02#lit#mira.mp3#disclaimer my thoughts not fact etc#im sorry this is so long-winded i'd edit it down but i'm too lazy so you get 500 words containing 50 words' worth of info <3#i added paragraph breaks thats it#annotations

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books I’ve Read: 2006-2019

Alexie, Sherman - Flight

Anderson, Joan - A Second Journey

- An Unfinished Marriage

- A Walk on the Beach

- A Year By The Sea

Anshaw, Carol - Carry the One

Auden, W.H. - The Selected Poems of W.H. Auden

Austen, Jane - Pride and Prejudice

Bach, Richard - Jonathan Livingston Seagull

Bear, Donald R - Words Their Way

Berg, Elizabeth - Open House

Bly, Nellie - Ten Days in a Madhouse

Bradbury, Ray - Fahrenheit 451

- The Martian Chronicles

Brooks, David - The Road to Character

Brooks, Geraldine - Caleb’s Crossing

Brown, Dan - The Da Vinci Code

Bryson, Bill - The Lost Continent

Burnett, Frances Hodgson - The Secret Garden

Buscaglia, Leo - Bus 9 to Paradise

- Living, Loving & Learning

- Personhood

- Seven Stories of Christmas Love

Byrne, Rhonda - The Secret

Carlson, Richard - Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff

Carson, Rachel - The Sense of Wonder

- Silent Spring

Cervantes, Miguel de - Don Quixote

Cherry, Lynne - The Greek Kapok Tree

Chopin, Karen - The Awakening

Clurman, Harold - The Fervent Years: The Group Theatre & the 30s

Coelho, Paulo - Adultery

The Alchemist

Conklin, Tara - The Last Romantics

Conroy, Pat - Beach Music

- The Death of Santini: The Story of a Father and His Son

- The Great Santini

- The Lords of Discipline

- The Prince of Tides

- The Water is Wide

Corelli, Marie - A Romance of Two Worlds

Delderfield, R.F. - To Serve Them All My Days

Dempsey, Janet - Washington’s Last Contonment: High Time for a Peace

Dewey, John - Experience and Education

Dickens, Charles - A Christmas Carol

- Great Expectations

- A Tale of Two Cities

Didion, Joan - The Year of Magical Thinking

Disraeli, Benjamin - Sybil

Doctorow, E.L. - Andrew’s Brain

- Ragtime

Doerr, Anthony - All the Light We Cannot See

Dreiser, Theodore - Sister Carrie

Dyer, Wayne - Change Your Thoughts, Change Your Life

- The Power of Intention

- Your Erroneous Zones

Edwards, Kim - The Memory Keeper’s Daughter

Ellis, Joseph J. - His Excellency: George Washington

Ellison, Ralph - The Invisible Man

Emerson, Ralph Waldo - Essays and Lectures

Felkner, Donald W. - Building Positive Self Concepts

Fergus, Jim - One Thousand White Women

Flynn, Gillian - Gone Girl

Follett, Ken - Pillars of the Earth

Frank, Anne - The Diary of a Young Girl

Freud, Sigmund - The Interpretation of Dreams

Frey, James - A Million Little Pieces

Fromm, Erich - The Art of Loving

- Escape from Freedom

Fulghum, Robert - All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten

Fuller, Alexandra - Leaving Before the Rains Come

Garield, David - The Actors Studion: A Player’s Place

Gates, Melinda - The Moment of Lift

Gibran, Kahlil - The Prophet

Gilbert, Elizabeth - Eat, Pray, Love

- The Last American Man

- The Signature of All Things

Ginsburg, Ruth Bader - My Own Words

Girzone, Joseph F, - Joshua

- Joshua and the Children

Gladwell, Malcom - Blink

- David and Goliath

- Outliers

- The Tipping Point

- Talking to Strangers

Glass, Julia - Three Junes

Goodall, Jane - Reason for Hope

Goodwin, Doris Kearnes - Team of Rivals

Graham, Steve - Best Practices in Writing Instruction

Gray, John - Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus

Groom, Winston - Forrest Gump

Gruen, Sarah - Water for Elephants

Hannah, Kristin - The Great Alone

- The Nightingale

Harvey, Stephanie and Anne Goudvis - Strategies That Work

Hawkins, Paula - The Girl on the Train

Hedges, Chris - Empire of Illusion

Hellman, Lillian - Maybe

- Pentimento

Hemingway - Ernest - A Moveable Feast

Hendrix, Harville - Getting the Love You Want

Hesse, Hermann - Demian

- Narcissus and Goldmund

- Peter Camenzind

- Siddhartha

- Steppenwolf

Hilderbrand, Elin - The Beach Club

Hitchens, Christopher - God is Not Great

Hoffman, Abbie - Soon to be a Major Motion Picture

- Steal This Book

Holt, John - How Children Fail

- How Children Learn

- Learning All the Time

- Never Too Late

Hopkins, Joseph - The American Transcendentalist

Horney, Karen - Feminine Psychology

- Neurosis and Human Growth

- The Neurotic Personality of Our Time

- New Ways in Psychoanalysis

- Our Inner Conflicts

- Self Analysis

Hosseini, Khaled - The Kite Runner

Hoover, John J, Leonard M. Baca, Janette K. Klingner - Why Do English Learners Struggle with Reading?

Janouch, Gustav - Conversations with Kafka

Jefferson, Thomas - Crusade Against Ignorance

Jong, Erica - Fear of Dying

Joyce, Rachel - The Love Song of Miss Queenie Hennessy

- The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry

Kafka, Franz - Amerika

- Metamophosis

- The Trial

Kallos, Stephanie - Broken For You

Kazantzakis, Nikos - Zorba the Greek

Keaton, Diane - Then Again

Kelly, Martha Hall - The Lilac Girls

Keyes, Daniel - Flowers for Algernon

King, Steven - On Writing

Kornfield, Jack - Bringing Home the Dharma

Kraft, Herbert - The Indians of Lenapehoking - The Lenape or Delaware Indians: The Original People of NJ, Southeastern New York State, Eastern Pennsylvania, Northern Delaware and Parts of Western Connecticut

Kundera, Milan - The Unbearable Lightness of Being

Lacayo, Richard - Native Son

Lamott, Anne - Bird by Bird

Word by Word

L’Engle, Madeleine - A Wrinkle in Time

Lahiri, Jhumpa - The Namesake

Lappe, Frances Moore - Diet for a Small Planet

Lee, Harper - To Kill a Mockingbird

Lems, Kristin et al - Building Literacy with English Language Learners

Lewis, Sinclair - Main Street

London, Jack - The Call of the Wild

Lowry, Lois - The Giver

Mander, Jerry - Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television

Marks, John D. - The Search for the Manchurian Candidate: The CIA and Mind Control

Martel, Yann - Life of Pi

Maslow, Abraham - The Farther Reaches of Human Nature

- Motivation and Personality

- Religions, Values, and Peak Experiences

- Toward a Psychology of Being

Maugham. W. Somerset - Of Human Bondage

- Christmas Holiday

Maurier, Daphne du - Rebecca

Mayes, Frances - Under the Tuscan Sun

Mayle, Peter - A Year in Provence

McCourt, Frank - Angela’s Ashes

- Teacher man

McCullough, David - 1776

- Brave Companions

McEwan, Ian - Atonement

- Saturday

McLaughlin, Emma - The Nanny Diaries

McLuhan, Marshall - Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man

Meissner, Susan - The Fall of Marigolds

Millman, Dan - Way of the Peaceful Warrior

Moehringer, J.R. - The Tender Bar

Moon, Elizabeth - The Speed of Dark

Moriarty, Liane - The Husband’s Sister

- The Last Anniversary

- What Alice Forgot

Mortenson, Greg - Three Cups of Tea

Moyes, Jo Jo - One Plus One

- Me Before You

Ng, Celeste - Little Fires Everywhere

Neill, A.S. - Summerhill

Noah, Trevor - Born a Crime

O’Dell, Scott - Island of the Blue Dolphins

Offerman, Nick - Gumption

O’Neill, Eugene - Long Day’s Journey Into Night

A Touch of the Poet

Orwell, George - Animal Farm

Owens, Delia - Where the Crawdads Sing

Paulus, Trina - Hope for the Flowers

Pausch, Randy - The Last Lecture

Patchett, Ann - The Dutch House

Peck, Scott M. - The Road Less Traveled

- The Road Less Traveled and Beyond

Paterson, Katherine - Bridge to Teribithia

Picoult, Jodi - My Sister’s Keeper

Pirsig, Robert - Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Puzo, Mario - The Godfather

Quindlen, Anna - Black and Blue

Radish, Kris - Annie Freeman’s Fabulous Traveling Funeral

Redfield, James - The Celestine Prophecy

Rickert, Mary - The Memory Garden

Rogers, Carl - On Becoming a Person

Ruiz, Miguel - The Fifth Agreement

- The Four Agreements

- The Mastery of Love

Rum, Etaf - A Woman is No Man

Saint-Exupery, Antoine de - The Little Prince

Salinger, J.D. - Catcher in the Rye

Schumacher, E.F. - Small is Beautiful

Sebold, Alice - The Almost Moon

- The Lovely Bones

Shaffer, Mary Ann and Anne Barrows - The Gurnsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society

Shakespeare, William - Alls Well That Ends Well

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Romeo and Juliet

- The Sonnets

- The Taming of the Shrew

- Twelfth Night

- Two Gentlemen of Verona

Sides, Hampton - Hellhound on his Trail: The Stalking of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the International Hunt for His Assassin

Silverstein, Shel - The Giving Tree

Skinner, B.F. - About Behaviorism

Smith, Betty - A Tree Grows in Brooklyn

Snyder, Zilpha Keatley - The Velvet Room

Spinelli, Jerry - Loser

Spolin, Viola - Improvisation for the Theater

Stanislavski, Constantin - An Actor Prepares

Stedman, M.L. - The Light Between Oceans

Steinbeck, John - Travels with Charley

Steiner, Peter - The Terrorist

Stockett, Kathryn - The Help

Strayer, Cheryl - Wild

Streatfeild, Dominic - Brainwash

Strout, Elizabeth - My Name is Lucy Barton

Tartt, Donna - The Goldfinch

Taylor, Kathleen - Brainwashing: The Science of Thought Control

Thomas, Matthew - We Are Not Ourselves

Thoreau, Henry David - Walden

Tolle, Eckhart - A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose

- The Power of Now

Towles, Amor - A Gentleman in Moscow

- Rules of Civility

Tracey, Diane and Lesley Morrow - Lenses on Reading

Traub, Nina - Recipe for Reading

Tzu, Lao - Tao Te Ching

United States Congress - Project MKULTRA, the CIA's program of research in behavioral modification: Joint hearing before the Select Committee on Intelligence and the ... Congress, first session, August 3, 1977

Van Allsburg, Chris - Just a Dream

- Polar Express

- Sweet Dreams

- Stranger

- Two Bad Ants

Walker, Alice - The Color Purple

Waller, Robert James - Bridges of Madison County

Warren, Elizabeth - A Fighting Chance

Waugh, Evelyn - Brideshead Revisited

Weir, Andy - The Martian

Weinstein, Harvey M. - Father, Son and CIA

Welles, Rebecca - The Divine Secrets of the Ya Ya Sisterhood

Westover, Tara - Educated

White, E.B. - Charlotte’s Web

Wilde, Oscar - The Picture of Dorien Gray

Wolfe, Tom - I Am Charlotte Simmons

Wolitzer, Meg - The Female Persuasion

Woolf, Virginia - Mrs. Dalloway

Zevin, Gabrielle - The Storied Life of A.J. Fikry

Zusak, Marcus - The Book Thief

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Intertwined Stories on Homosexual Issues

The Hours is a drama film directed by Stephen Daldry. The movie was released in United States on December 18, 2002, and won Oscar Award in the same year. It tells the inextricable connection between three women in different eras. To be honest, it is a deeply depressing and shocked Montage movie, which shows the different reaction made by three heroines, Virginia Woolf, Laura Brown, and Clarissa Vaughan, when facing same social and psychology pressure brought by gay and lesbian issues. By showing those stories, The Hours shows audiences how different people make their choice when facing death problems on homosexual issues: Escaping through death, meekly accepting, or getting rid of the pass. Although The Hours’s major concerns do not maintain colored gays or lesbian groups, it is a good movie which using Montage structure to guide its audiences to a broader real-life concept.

Virginia Woolf is a talented author, lived in a countryside in Britain in 1920s. She used to live in London, but finally settled down in the countryside in order to cure her illness. Virginia herself cannot stand for such a quiet life; she is eager for living in a busy city. This repressed country life made Virginia breathless, and her homosexual identity gradually revealed: she kissed her sister in her house. Being gay or lesbian was actually illegal in England at that time (Caitlin, 2015). I consider this kiss as the way Virginia recognizes and expresses herself in her repressed daily life, which is similar with the “coming out” process in homophile movement throughout the 1950 and into the 1960, when “the individual realization that one was homosexual, and the acknowledgment of this sexual identity to other gay people.”(Gross, 2002) Virginia’s self-conscious also start the plot that she persuaded her husband to move back to London latter in the movie. A plot at the beginning of Virginia’s story shows her fight ended in failure: She drowned herself into the river in the countryside. Perhaps Virginia’s homosexual identity isn’t recognized by the society, in the following years, she went back to the quiet countryside and suicide in despair.

Laura is a typical housewife with a lovely son. She lived in the Los Angeles in 1950s, shortly after the end of World War II, when men returned to ordinary life with the honor in battlefield. Unlike others, Laura seems to be laden with anxiety; she was trapped in her dully life. It was Virginia’s novel, Mrs. Dalloway, resonated her to yearn for a new life style. When Laura’s friend came to visit her, she imitated Virginia and kiss her female friend. Her friend avoided contact with Laura latter on since homophobia, which makes Laura totally disappointed. She threw the unfinished birthday cake she made for her husband into the garbage can and wanted to give up her life as well. Laura wanted to suicide just like the story in Mrs. Dalloway. But in the end, she gave up and returned to her normal life. Laura has an intersectionality identity, not only as a white middle class lesbian, but also as a tender mother and a virtuous wife. In the heteronormativity concept in the society, Laura cannot only live for herself, she needs to be responsible for her family and fix into the family role, although they are contrary to her sexual orientation and personal willingness. Warner once stated how heterosexuality social mainstream shapes personal living way, “Het culture thinks of itself as the elemental form of human association, as the very model of intergender relations, as the indivisible basis of all community, and as the means of reproduction without which society wouldn't exist”, “Materialist thinking about society has in many cases reinforced these tendencies, inherent in heterosexual ideology, toward a totalized view of the social.” (Warner, 1993) Laura cannot ignore her child and husband’s expectation for her. Finally, Laura remade the birthday cake, celebrated birthday night with her husband, and continued her dully and hopeless life.

Relatively speaking, Clarissa Vaughan’s story is the best among three heroines. Clarissa is an editor who felt in love with Richard Brown, a gay writer with AIDS. Clarissa took good care of Richard every day, and considered that her life is meaningful only by staying around Richard. Richard, on the other hand, suffered from AIDS, disliked and scared by all his friends except Clarissa due to his disease. The only reason for him to keep alive is Clarissa. This type of living style is not what Clarissa and Relatively wanted, they just created cages for each other. The audiences can see how Clarissa wanted to get rid of it and started a new life, from the plot she cried alone in the kitchen. Finally, Richard jumped out of the window to stop Clarissa spending more time on him, and force Clarissa to start her new life. Although Clarissa was in heartbreaking sadness, she finally got rid of the past and started her new life.

Besides of the story, there are a lot of details and metaphors among the movie in order to make the it more lively and real to audiences. For example, Virginia’s sustained anxiety state and her unconscious action of biting the bottom of the pen when writing; Laura’s confused and unconfident mental state as well as the birthday ceremony cake she made twice; Clarissa’s messy hairstyle and her anger when Richard giving up himself. Although The Hours organized in Montage way, which lenses frequently switch form plots to plots, it brings a smooth viewing experience since the emotion between plots are identical and well organized. Those stories focused on the life of heroines, rather than any specific queer issues, which also claimed by Goltz et al, “‘To come out as me and not to highlight his sexuality, preferring to ‘talk about me, about my life, not about my queer life” (Goltz et al, 2016).

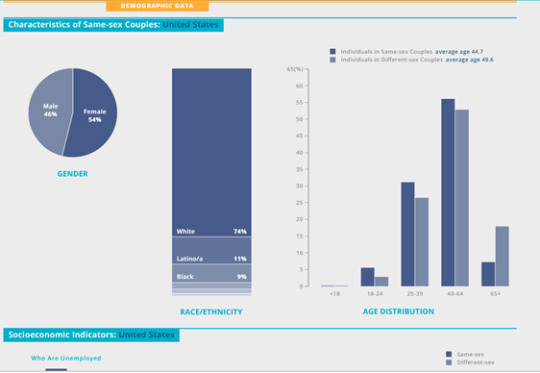

Although The Hours tells a great story of the death problems that queer people are facing among different period of time, it seems that its major concerns are all white people. The Hours failed to represent any living situation of black gay and lesbian people. While according to the report of UCLA, African-American take up about 12% of LGBTQ group nowadays. (The Williams Institute, 2019). The public’s losing attracted on colored skin people may cause them faced misrepresentative and misunderstanding. According to Ludmila Leiva’s words, “As a queer person who is also a person of color, watching television is a fraught experience for me. Constantly, I find myself searching for characters whose stories mirror my own and, repeatedly, I come up empty-handed. I am forced to accept the few, tiny fragments reflecting my own lived experiences that I can find scattered across today’s TV offerings, but I am tired. I long desperately for television writers, producers, and networks to prioritize the centering of human experiences beyond the conventional, and I know I am not alone.” (Ludmila, 2017)

Obviously, the experience of queer people in color is different than the white, but only a few people notice it in TV and film industry. Existing media works cannot represent them in the correct way, which will create unfair treatment toward those minority groups. The phenomenon of lacking colored queer concepts in The Hours and other media projects still need time to improve.

As a Chinese citizen, I must say that this movie shocked me a lot. CPC is harmonizing Chinese online environment, concepts like LGBTQ rarely appeared in Chinese public view. It is scary how many Chinese male and female actually living their daily life just like Virginia Woolf, Laura Brown, or Clarissa Vaughan. From my personal perspective, the most desperate story in The Hours is Laura’s one, she cannot ignore her child and husband’s expectation for her, thus she needs to keep living along with dull and hopeless life in the rest of her life. Happened to know that from Chinese perspective, Confucianism create a great heteronormativity for both man and woman to obey their role.

In general, I think The Hours is a great film to appreciation and analysis. Montage itself is a great way to guide the audience's mood and enlighten them to think more. By using Montage, the director maximizing the tension while guaranteed the integrity of his film. Moreover, the juxtaposition and intersection of Virginia Woolf, Laura Brown, and Clarissa Vaughan’s stories cause tension suspense throughout the entire film, and shows the relationship between each character in different places and different time period when facing the similar problem. In the end of the film when all three stories come to the end, the sense of shock comes continuously to force me think more outside the movie’s concept into the reality.

Works Cited

Gallagher, C. (2019). Was It Illegal to Be Gay In 1920s England Or Is Thomas Barrow's Struggle On 'Downton' Just About Cultural Pressure?. [online] Bustle. Available at: https://www.bustle.com/articles/62849-was-it-illegal-to-be-gay-in-1920s-england-or-is-thomas-barrows-struggle-on-downton [Accessed 27 Oct. 2019].

Gross, L. P. (2002). Up from invisibility: lesbians, gay men, and the media in America. New York: Columbia University Press.

Goltz, D. B., Zingsheim, J., Mastin, T., & Murphy, A. G. (2016). Discursive negotiations of Kenyan LGBTI identities: Cautions in cultural humility. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 9(2).

Leiva, L. (2019). TV Is Getting More Progressive, But It's Still Failing Queer People of Color. [online] Bustle. Available at: https://www.bustle.com/p/tv-is-getting-more-progressive-but-its-still-failing-queer-people-of-color-64520 [Accessed 25 Oct. 2019].

Warner, M. (Ed.). (1993). Fear of a queer planet: Queer politics and social theory (Vol. 6). U of Minnesota Press.

Williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu. (2019). The Williams Institute. [online] Available at: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/visualization/lgbt-stats/?topic=SS#demographic [Accessed 30 Oct. 2019].

#QueerMedia#The Hours#coming out#heteronormativity#intersectionality identity#AIDS#Virginia Woolf#Laura Brown#Clarissa Vaughan#social mainstream

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm going to be starting college in 2019 and I've always loved to read. I know you majored in English and I was wondering what you liked about it, what you didn't like about it and what I should expect. I'm nervous about declaring a major, but I think English would be the best fit for me.

oh goodness ! first of all, congratulations on thinking ahead about college. second of all, congratulations on thinking about your major. third of all, congratulations on thinking about english literature!

english literature is, obviously, very near and dear to my heart. books and words have always resonated with me in some way, and getting to spend four-ish years studying them and becoming well-versed in their history and impact was the best thing. but, english literature as a major and college as a whole are not quite what i had expected. so in the most concise possible way, i will attempt to avoid rambling whilst trying to tell you about my experience.

i think the first thing i should say is this: if you declare english literature as your major, do not let people around you question that decision. you’ve probably already heard it, but the biggest thing that happens to english majors are people in their life or even strangers making that face and saying, “what are you going to do with that?” before immediately assuming you’re going to be a high school english teacher. english as a degree is extremely versatile, making its own arsenal of skills and tools that would benefit almost any employer. do not let people make you feel bad for your declared major, and do not think that you only have to teach.

that all being said, there is no shame in teaching either (in fact, i’m applying for grad school to get my masters in english so i can teach). teaching english is so valued and so needed. the benefits of literature on the minds of children and adults are endless and not simply limited to ‘read “to kill a mockingbird” and tell me your favorite character, next’

another important thing to remember, i think, is that just because you delcare a major does not mean you have to stick with it. there is no shame in discovering something new about yourself and declaring a new major. you can still love books and words, but not want to study them every waking moment. be open to change. luckily for me, literature was everything i needed in my life. i knew it was right for me every day i was in school. but i had a friend who was a psychology major her first year, an english major her second year, and finally declared early childhood education her third year and fell in love. it’s different for every person out there and it may take time. or it may be perfect for you from the start. just pay attention to your mind and where it veers, and pay attention to your heart and what it wants. you’ll figure it out.

now, as for the major itself, this may sound obvious but: be prepared to read and write a lot. when i say a lot, i mean 211 books in 3 1/2 years. when i say a lot, i mean 200-300 pages worth of essays a semester (this is if you take 3+ english classes a semester, however). it is time consuming, it is frustrating, and it is so rewarding all at once. you will finish a class and be so proud of yourself that your heart sings. and you will finish another class and run out the door and never ever look back. you will get around to reading classics and find that you love every word on the page (pride and prejudice, anna karenina, lolita, on the road, mrs. dalloway, etc.) and you will get around to reading classics that you despise and will question their popularity always (wuthering heights, pamela, the old man and the sea, the art of war, wuthering fucking heights). you will read books you’ve never heard of in your life, you will learn things about history that will blow your mind, you will learn that nothing has ever really changed in the world, it’s just a lot smaller.

you won’t have a lot of time to read and/or write for fun, and when you do have the time, you won’t want to because it’s all you’ve been doing for five months straight and you would like to not stare at a word document or a page of a book for another year, thanks. you will also feel guilty for not reading and writing in your free time and you’ll try, but often your mind will be so exhausted of words that you’ll end up watching law & order svu reruns for six hours instead.

you will come across some of the most pompous and self-absorbed english majors in the world. you will find people who only read james joyce and can list a million reasons why there hasn’t been a book of worth published since 1974. you will find people who will compare everything to their own writing and end up telling the class about their superior writing style and process. you will find people who think they like books, but they just really loved the harry potter series as a kid and don’t read anything else. you will find pearl-clutchers that will throw a fit about reading lolita and flowers in the attic or books with any blatant sex scene because that’s “not what they wanted to learn about in literature.” you will find that uncomforable topics can lead to some of the best discussions in a classroom because it’s topics like these that are all throughout our history yet no one talks about them.

you will come across professors that want you to look at books with a detached analysis. you will come across professors who are passionate it makes you passionate. you will come across professors that struggle to separate their own love of a topic or book or author from your possibly different look at the same thing. again, it is frustrating, but it can be so rewarding too.

i think the worst part of college for me, however, was taking the classes that were not english. i loved my literature classes so much and saw very little use in my other classes that i grew really jaded with the entire concept of undergraduate degrees. i was the first in my family to go to college, and so i didn’t know exactly what to expect. what i thought college was is more of what graduate degrees are; where you take classes only pertaining to the subject of your choice and you become an expert on it. i found that every class i struggled with made me angry even moreso by it not being an english class. i would look at my math classes or environmental science and go ‘this isn’t even close to what i want to do with my life, what does it matter?’ so when you have an english class that you really enjoy, make certain you spend as much time ejoying it as possible. it’s not always easy to do that.

most importantly, don’t feel like you have to adhere to any specific timeline. things will happen for you on terms that are different than they are for other people. breathe, and remember you are more than your grades and your future career is not going to be destroyed by one bad grade or two or three. you are fine and you will excel in ways that you may least expect.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any book recommendations?

I DO actually but you’ll find out I’m a pretty boring person who only reads very angsty and sad books,,

anyway!!! here we go!!!!

Artemisia by Anna Banti

(This one is actually one of my favorite books)

“Artemisia is a book about the process of artistic creation.Much in Gentileschi’s life marked her out as a victim – rape at the age of 18, a forced marriage to a man she did not love and, a powerful, patriarchal father, Orazio Gentileschi, who failed to value her artistic genius. But Gentileschi did not accept the status of victim, in the years between 1610 and 1650, she produced over 50 paintings that have established her as one of the great painters of all time.She gave up everything – “all tenderness, all claim to feminine virtues” to dedicate herself solely to painting. Sacrifices that Anna Banti, herself an artist, fully understands and captures in this amazing novel.”

Letter to a Child Never Born by Oriana Fallaci

(Big tears over this one)

“It is written as a letter by a young professional woman (presumably Fallaci herself) to the fetus she carries in utero; it details the woman's struggle to choose between a career she loves and an unexpected pregnancy, explaining how life works with examples of her childhood, and warning him/her about the unfairness of the world.”

The Death of Ivan Ilyich by Leo Tolstoj

(I’m a slut for Russian literature :/ )

“One of the finest novellas ever written[2], The Death of Ivan Ilyich tells the story of a high-court judge in 19th-century Russia and his sufferings and death from a terminal illness.”

The Kreutzer Sonata by Leo Tolstoj

(A slut, as I said)

“The work is an argument for the ideal of sexual abstinence and an in-depth first-person description of jealous rage. The main character, Pozdnyshev, relates the events leading up to his killing of his wife: in his analysis, the root causes for the deed were the "animal excesses" and "swinish connection" governing the relation between the sexes.”

Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

(tbh it is a little boring, unless you’re already bored more than the book itself if that makes any sense)

“The novel addresses Clarissa's preparations for a party she will host that evening. With an interior perspective, the story travels forward and back in time and in and out of the characters' minds to construct an image of Clarissa's life and of the inter-war social structure.”

These are the ‘Books I had to read for my academic preparation but that actually turned out to be compelling’.

If you actually wanted to read something a little happier or at least not so angsty you asked the wrong person because I’m a masochist this is all I can think at the moment:

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

(Yes, I know, but the book is actually so good I couldn’t stop reading!!)

The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller

(Actually, this will make you cry too, but it’s oh so good)

“Set in Greece, tells the story of a love affair between Achilles and Patroclus.[4] Miller was inspired by the account of the two men from Homer's Iliad and said she wanted to explore who Patroclus was and what he meant to Achilles.”

Red, White & Royal Blue by Casey McQuinston

(This is all fluff and happy things and you’ll fall in love with every scene I swear)

“Red, White & Royal Blue follows Alex, a fictionalized First Son who finds himself in a fight with Henry, an English prince, and is forced to befriend him for PR reasons, developing romantic feelings for him along the way.”

Thank you for the ask, anon!!! Hope you’ll find something you enjoy<3

#this ask made me realise i only read depressing books oh my god that explains a LOT about my mental health rn :/#im so sorry anon for real#i was SO excited about this ask and then was like.. i only read sad books#replies#me#artemisia gentileschi#leo tolstoy#virginia woolf#mrs dalloway#pride and prejudice#jane austen#the song of achilles#red white and royal blue#books recommendations

0 notes

Text

I was tagged by @onbanksofanamelessriver. Thank you!

1. Which book has been on your shelves the longest?

I have no idea. Probably some children’s book that’s falling/fallen apart... Pelle Svanslös maybe, or something by Richard Scarry?

If we’re talking my current shelf, I think it’d be Harry Potter.

2. What is your current read, your last read and the book you’ll read next?

My current reads are Viipurin Kaunotar (the Beauty of Vyborg) by Kaari Utrio, which is a historical romance I read when I’m outside with my cat, and Iso suomen kielioppi (Big book of Finnish grammar) which I’m reading for an exam.

My last read was poetry collection by Wisława Szymborska. I read it for uni poetry analysis course, but I really liked it and I can recommend it.

I haven’t decided what I’m going to read next, but possibly Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf or All the Light We Cannot see by Anthony Doerr. Or I could start my Wheel of Time re-read. Idk.

3. Which book does everyone like and you hated?

The Wind in the Willows is irritating drivel. Also I have never been able to force myself through more that two Narnia books, and even that was a struggle.

4. Which book do you keep telling yourself you’ll read, but you probably won’t?

Shakespeare’s plays. I really should (and I think I’m going to have to read Hamlet for my literature course) but I also well and truly hate reading anything in play format, so...

5. Which book are you saving for “retirement?”

I don’t understand the concept of planning that far ahead.

6. Last page: read it first or wait till the end?

I usually wait till the end, but sometimes I get impatient and take a quick glance and hope that I see nothing too spoilery.

7. Acknowledgements: waste of ink and paper or interesting aside?

Usually waste of ink and paper, but if I ever help anyone with their book I’ll sure as hell demand to be acknowledged .

8. Which book character would you switch places with?

I read way too much fantasy/historical fiction for this question, I’m not planning on giving up modern medicine or running water any day soon. It would be nice to visit Middle Earth though, especially Second Age Khazad-dûm and Rivendell.

9. Do you have a book that reminds you of something specific in your life (a person, a place, a time)?

Well, the Order of the Phoenix reminds me of trying no to cry - and failing that, trying not to cry noticeably - while sitting in a car with my dad and little sister on a family holiday in Denmark.

Also the general concept of Jack and the Beanstalk reminds me of the agony I put my grandfather and great aunt through, because I demanded that the story be read to me, twice a day or more if possible, every time I was visiting when I was little. I knew the story by heart, so they couldn’t get away with trying to skip even a single word, and I didn’t care for suggestions that we might choose a different book every once in a while.

I think they were both very happy when I learned to read.

10. Name a book you acquired in some interesting way.

I got a cookbook printed in 1943 from my grandma when I asked her for a slightly older gingerbread recipe (which would have all the spices listed separately, as opposed to just ‘gingerbread spice mix’). That was slightly older, all right.

11. Have you ever given away a book for a special reason to a special person?

I gave my copy of the Philosopher’s Stone to my cousin so that she could practice reading English. Also I threw out my copy of the Hobbit because my cat peed on it and I decided I don’t like it that much. Do those count?

12. Which book has been with you to the most places?

I don’t carry around a lot of books these days, and definitely not the same book, so I think we are talking something of a Nummelan Ponitalli variety. (It’s a series of Finnish horse-y books with about a million parts that I used to read when I was younger.)

13. Any “required reading” you hated in high school that wasn’t so bad ten years later?

Nope. Häräntappoase (’an Ox-killing weapon’, a youth novel by Anna-Leena Härkönen) and Pojat (’Boys’, a WWII story featuring teen boys by Paavo Rintala) are still utter garbage. Also it’s ten years later for me now and Coetzee’s Boyhood is still virtually unreadable. What he got his Nobel prize for I’ll never understand.

14. What is the strangest item you’ve ever found in a book?

Shop receipts older than I am.

15. Used or brand new?

Whichever is cheaper.

16. Stephen King: Literary genius or opiate of the masses?

Can’t he be both?

I haven’t read much King though, I don’t really care for horror. (Read = I’m a wimp.) But I still have the Dark Tower-series on my list of future reading. I’ve read the first two and I liked them, but somehow I never got around to finishing the series.

17. Have you ever seen a movie you liked better than the book?

Agatha Christie’s works as a rule are better as a play/TV-series/movie, and same goes for Sherlock Holmes. Though it should probably be mentioned that I have negative interest in reading any detective stuff, and that might influence my opinion somewhat.

Also the Hobbit book and the Hobbit movies both have some glaring flaws, but on balance, I think I might prefer the movies.

18. Conversely, which book should NEVER have been introduced to celluloid?

They never ever ever should’ve made the 2007 Beowulf. I can’t even remember what happened in it, I just remember the terrifying uncanny valley Polar Express from hell -style it was shot with. Unwatchable. Also Eragon the book was a horrifying mistake, and Eragon the movie was even worse.

And it’s not that they shouldn’t have been filmed, but unfortunately the Harry Potter movies were grossly underwhelming at best. Same goes for the film adaptations of Täällä Pohjantähden alla (Under the North Star) by Väinö Linna.

19. Have you ever read a book that’s made you hungry, cookbooks being excluded from this question?

Even thinking about Enid Blyton’s the Famous Five still makes me crave tomatoes. Otherwise, not really.

20. Who is the person whose book advice you’ll always take?

I rarely get book advice, and tend to forget about it almost immediately if I do.

Tagging @heartoferebor @cestpasfaux24601 @mainecoon76 @miseryrun @alkonjonossa if you feel like doing this

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Psychoanalytic Dualism of Mrs. Dalloway´s characters

José Garrido

Geraldine Lara

Virginia Woolf’s ‘‘Mrs. Dalloway’’ portrays an interesting post World War I society in which characters are being constantly influenced by the consequences of this historical event. Not only are the changes imposed by governments shaping our characters’ minds and personalities, but also the development of their own internal world. How they metabolize the direct or indirect exposition to death of that period is going to be an important process to the self of the beings. As we have to deal with these factors of the conscious and unconscious of the mind, it results wise to psychoanalyze the characters’ behaviour in order to comprehend and illustrate more profoundly certain interpretations. Through Freud’s ‘‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’’ we are going to understand the instinctive drives manifested in Clarissa Dalloway and Septimus Warren, which represent a relationship of dualism that clarifies the Freudian notions of Thanatos and Eros....

Through years, different types of criticism has been created in order to analyse literature in an effective way, this is to say, avoiding fallacies. One important school is Psychoanalysis that maintains the main characteristics that Freud has studied. Psychoanalytic literary criticism is understood as a tool that helps us discover and understand the reflection of the author’s most hidden desires and anxieties that are repressed by the conscious mind, inside a particular text. Freud, at first, bonded all human behaviour to the sexual instinct (‘‘Eros’’), but he realised that there was also another human natural instinct as a counterpart of the previous: the death drive (‘‘Thanatos’’). This way, the dichotomy between self-preservation and self-destruction is proposed as a constant identity struggle that, in literature, commonly ends with one of the two sides triumphing.

Jacques Lacan also refers to this idea that postulated Freud, but he centres the idea of psychoanalysis in four different perspectives: The Drive, the Unconscious, Repetition Compulsion and Transference. For our essay, the different conceptions of drive are important, thus are necessary to clarify. The notion of drive differs from Freud’s, in that Lacan’s drive is not a mean to accomplish satisfaction but to circle round the object, creating a repetitive enjoyable movement. Furthermore, Lacan’s drive presents a dual bond between the symbolic and the imaginary and not in opposition, both belonging to the same type of drive. As to Lacan drive is excessive and repetitive, all drives are destructive, so part of the Thanatos.

The death drive (Thanatos) pursues the self returning to an inorganic state, and as Julia Kristeva implies in her work ‘‘Black Sun’’, ‘‘he [Freud] considers the death drive as an intrapsychic manifestation of a phylogenetic going back to inorganic matter. Nevertheless… it is possible to note… the strength of the disintegration of bonds within several psychic structures and manifestations. Furthermore, the presence of masochism, the presence of negative therapeutic reaction… prompt one to accept the idea of a death drive that, … would destroy movements and bonds’’ (Kristeva 16-17). Here we notice that this perception indicates that there are two different death drives, one in the psyche manifested to the outside as a violent instinct, and the other manifested to the inner self, self-destructive. This last one can result in an accumulation and cultivation of death drive, and Kristeva questions if this process could be erotized by the self, being implicitly part of the pleasure principle and leading to a constant change of the satisfaction object.

Freud’s concepts of Thanatos and Eros are present in the characters of ‘‘Mrs. Dalloway’’ since they behave according to inner forces that propel them to do so. In the case of Septimus Warren Smith, it is important to say that he is a veteran soldier that is shell-shocked by the impact of World War I because one friend of his, Evans, was killed there and Septimus saw it. Before the war, he was a normal person and he liked poetry. But after that he became a numb person. Moreover he is becoming mad and has different kinds of hallucinations. At the time of the story, Septimus and his wife Lucrezia are waiting for a doctor in an apartment, who is going to treat Septimus’ problems. They both pass through a very lovely moment but then Septimus throws himself out the window and dies.

First, Freud’s Thanatos is highly related to the death instinct and to the self-destruction of the person. This is explicitly clear at the end of the work with Septimus death. Second, this sudden personality change after war is related to the Unconscious mind, proposed by Lacan, in which the repressed feelings change the way in which a person behaves. Also this is shown in the form of automatic thoughts that are the ones that appear without any apparent cause, which are represented by the desire of death at the end of the story. Moreover, the Lacan’s Repetition Compulsion concept is also present since, as the name says, Septimus repeated in his mind several things that happened in the war that made him feel distressed to the point he turns mad and suffers hallucinations which are also an important behavioural characteristic of this kind of phenomenon. This character present an extreme case of cultivation of death drive, and Kristeva’s notion of erotization of it seems possible as Septimus is always looking for the pleasure and liberation of death, re-encountering with his dead friend.

In the case of Clarissa Dalloway, Freud’s Eros is dominant. She had a strong relation with the life instinct. It has to do with solidarity and true love. Also she tries to relate people with each other because it is a pleasure for her, and this can be seen in the fact that she is giving a party to a high number of people.

“Every time she gave a party she had this feeling of being something not herself, and that everyone was unreal in one way; much more real in another. It was, she thought, partly their clothes, partly being taken out of their ordinary ways, partly the background, it was possible to say things you couldn't say anyhow else, things that needed an effort; possible to go much deeper” (Virginia Woolf, 134).

However, Clarissa is also affected by the World War I since she saw her sister being killed, so two of the Four fundamental principles of Lacan are present: Transference and the Drive Theory. The first is related to the reproduction of emotions related to past events since she constantly sees the changes that the war brings to society, and more importantly, she every now and then thinks about her sister. The second one is related to a negative state of tension created when some psychological needs are not satisfied. This is shown in the work through the Clarissa’s pessimistic way of seeing things because she is mostly interested in her own social gratification.