#ghost tale in yotsuya

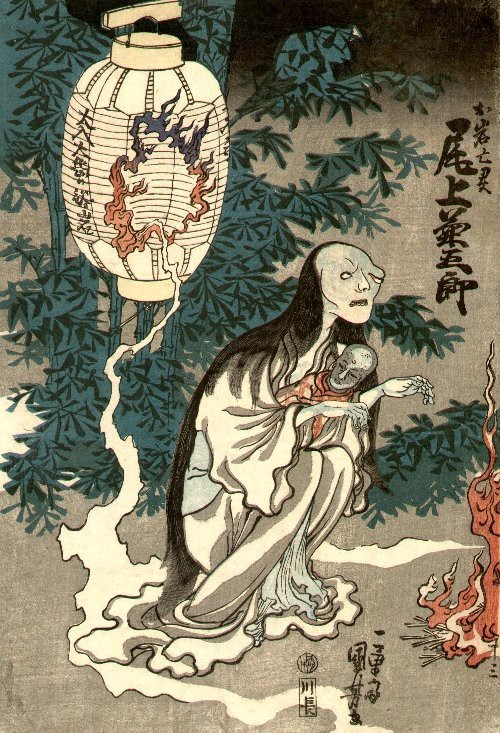

Photo

Onoe Matsusuke as the Ghost of the Murdered Wife Oiwa, in "A Tale of Horror from the Yotsuya Station on the Tokaido Road". 1812. Credit line: Gift of Louis V. Ledoux, 1927 https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45290

#aesthetic#art#abstract art#art museum#art history#The Metropolitan Museum of Art#museum#museum photography#museum aesthetic#dark academia

94 notes

·

View notes

Note

(this is spacekrakens lmao) dude idk anything about like 1950s Japanese cinema, do you have any recommendations? looking for stuff to toss on the watchlist now that I'm a bit burned out on horror (unless you have some horror recs)

Hey! If you’re curious about Japanese cinema (particularly 1950s), there’s a lot of avenues to explore! Musicals, crime, horror, historical—it all depends on what mood you’re in. (Putting this under a read more because I'm DEFINITELY going to be long posting about this!!!) Hope this is useful to you lol.

(Also noting if anybody wants to add to this list with their own recommendations feel free!!)

With old school Japanese cinema, I’ll always recommend Akira Kurosawa (obviously). He’s made some of the best Japanese movies (and arguably, the best movies of all time imo) and I feel like his work is a good gateway. It’s readily available on physical media/streaming too.

Specifically ‘50s stuff; Hidden Fortress (1958) is a good adventure flick whose structure was swiped for Star Wars, Throne of Blood (1957) is Japanese Macbeth if you like Shakespeare, and if you don’t mind a longer movie Seven Samurai (1954) includes Toshiro Mifune acting like this;

Gotta admit, though—my personal favorites from Kurosawa don’t come from the 1950s; Drunken Angel (1948) and Yojimbo (1961). One has a pathetic gangster as the main lead, the other is just a solid, breezy proto-action film (also has my beloved Unosuke but that's besides the point)

Some personal favorites of mine from the 1950s:

Life of a Horse Trader (1951) is a bittersweet story about a man trying to be a good single father to his son in the backdrop of Hokkaido. He tends not to be great at it. Stars Toshiro Mifune, the most famous face of Japanese cinema and for good reason!

Conflagration/Enjo (1958) is a single Buddhist acolyte’s fall into quiet insanity. Raizo Ichikawa is another amazing actor who I love! Also includes Tatsuya Nakadai who is the GOAT (in my heart).

Godzilla (1954) is AMAZING! If you liked Gozilla Minus One, it took a lot of familiar cues from this movie. It also technically counts as horror, depending on your definition.

Japanese horror from the 1950s:

Ugetsu (1951) (Not one I’ve seen personally, but it’s on Criterion)

The Beast Shall Die (1958) (American Psycho, but in Showa Japan. Tatsuya Nakadai is terrifying in this and absolutely despicable—stylish movie tho!)

Ghost of Yotsuya (1959) (Old-school Japanese ghost story. Honestly, there are so many different versions of this story on film that you can pick which version to watch and go from there—I’m partial to the 1965 version myself, because of the rubber rats and Tatsuya Nakadai playing a crazy person).

The Lady Vampire (1959) is the OG western-style vampire movie from Japan. Plays around with the mythos a lot, but hey our Dracula looks like this;

Misc movies that I think are neat or good gateway movies:

The Samurai Trilogy by Hiroshi Inagaki, which stars Toshiro Mifune as Miyamoto Musashi. Found that people otherwise uninterested in Japanese cinema really enjoyed this!

You Can Succeed, Too (1964) is one of my favorites from the ‘60s, also directed by Eizō Sugawa. A fun satire on the corporate world that's super colorful with catchy songs.

The Sword of Doom (1966) is also another favorite of mine, starring my beloved Tatsuya Nakadai as another bastard man (seriously though Ryunosuke is FASCINATING to me--). Fun gore effects and action scenes!

Kwaidan (1964) is an anthology of Japanese folk tales, labeled a horror film but in that kinda sorta old-school way. Beautifully shot by my favorite Japanese director Masaki Kobayashi (who, if you like this you should seriously check out his other work!)

#thanks for the ask!#akira kurosawa#tatsuya nakadai#toshiro mifune#raizo ichikawa#japan#film#godzilla#hidden fortress#seven samurai#drunken angel#yojimbo#enjo#sword of doom#kwaidan#you can succeed too#samurai trilogy#the lady vampire#ghost of yotsuya#ugetsu#life of a horse trader#throne of blood#ask

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Yotsuya Kaidan, the story of Oiwa and Tamiya Iemon, is a tale of betrayal, murder and ghostly revenge. Arguably the most famous Japanese ghost story of all time, it has been adapted for film over 30 times and continues to be an influence on Japanese horror today. Wikipedia

447 notes

·

View notes

Text

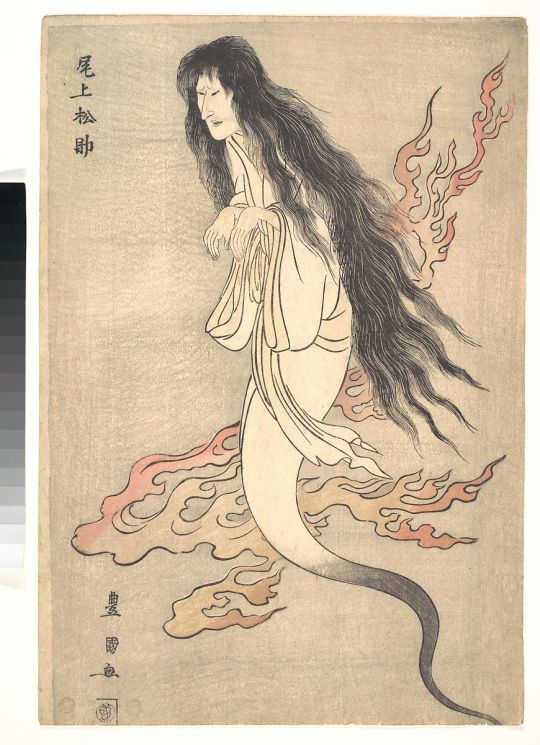

Yotsuya Kaidan (四谷怪談), ukiyo-e by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

The story of Oiwa and Tamiya Iemon is a tale of betrayal, murder and ghostly revenge. Arguably the most famous Japanese ghost story of all time, it has been adapted for film over 30 times and continues to be an influence on Japanese horror today. Written in 1825 by Tsuruya Nanboku IV as a kabuki play, the original title was Tōkaidō Yotsuya Kaidan (東海道四谷怪談, Ghost Story of Yotsuya in Tokaido). It is now generally shortened, and loosely translates as Ghost Story of Yotsuya.

First staged in July 1825, Yotsuya Kaidan appeared at the Nakamuraza Theater in Edo (the former name of present-day Tokyo) as a double-feature with the immensely popular Kanadehon Chushingura. Normally, with a Kabuki double-feature, the first play is staged in its entirety, followed by the second play. However, in the case of Yotsuya Kaidan it was decided to interweave the two dramas, with a full staging on two days: the first day started with Kanadehon Chushingura from Act I to Act VI, followed by Tōkaidō Yotsuya Kaidan from Act I to Act III. The following day started with the Onbo canal scene, followed by Kanadehon Chushingura from Act VII to Act XI, then came Act IV and Act V of Tōkaidō Yotsuya Kaidan to conclude the program.

The play was incredibly successful, and forced the producers to schedule extra out-of-season performances to meet demand. The story tapped into people’s fears by bringing the ghosts of Japan out of the temples and aristocrats' mansions and into the home of common people, the exact type of people who were the audience of his theater.

source

#yotsuya kaidan#ghost story#japanese folklore#japanese ghost story#ukiyo-e#kabuki#utagawa kuniyoshi#japan art#japan#japanology

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ghost of the Murdered Wife Oiwa, in "A Tale of Horror from the Yotsuya Station on the Tokaido Road", 1812

Utagawa Toyokuni I

woodblock print

Metropolitan Museum of Art

#ghost#japanese horror#japanese art#japanese 1800s art#1800s art#horror illustration#yurei#japanese folktale#japanese folklore#metropolitan museum of art

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

Onryō

In Japanese traditional beliefs and literature, onryō refers to a ghost believed to be capable of causing harm in the world of the living, injuring or killing enemies, or even causing natural disasters to exact vengeance to "redress" the wrongs it received while alive, then taking their spirits from their dying bodies. Onryō ghosts are often wronged women, who are traumatized by what happened during life and exact revenge in death.

Pic by Manzanedo on DeviantArt

While the origin of onryō is unclear, belief in their existence can be traced back to the 8th century and was based on the idea that powerful and enraged souls of the dead could influence, harm, and kill the living. The earliest onryō cult that developed was around Prince Nagaya who died in 729; and the first record of possession by the onryō spirit affecting health is found in the chronicle Shoku Nihongi (797), which states that "Fujiwara Hirotsugu (藤原広嗣)'s soul harmed Genbō to death" (Hirotsugu having died in a failed insurrection, named the "Fujiwara no Hirotsugu Rebellion", after failing to remove his rival, the priest Genbō, from power). Emperor Antoku (December 22, 1178 – April 25, 1185) and Emperor Daigo (February 6, 885 – October 23, 930) in Japanese history were believed to have been onryōs.

According to the belief of Ikiryō, a person's soul or spirit exists naturally when it is stable or in balance. When too much hatred or resentment brews, it can become separated from the body, resulting in the spirit becoming an onryō. This can allegedly also occur in individuals who died an untimely death.

Traditionally in Japan, onryō driven by vengeance were thought capable of causing not only their enemy's death, as in the case of Hirotsugu's vengeful spirit held responsible for killing the priest Genbō, but causing natural disasters such as earthquakes, fires, storms, drought, famine and pestilence, as in the case of Prince Sawara's spirit embittered against his brother, the Emperor Kanmu. In common parlance, such vengeance exacted by supernatural beings or forces is termed tatari.

The Emperor Kanmu had accused his brother Sawara, possibly falsely, of plotting to remove him from the throne. Sawara was then exiled, and died by fasting. According to a number of scholars, the reason that the Emperor moved the capital to Nagaoka-kyō thence to Kyoto was an attempt to avoid the wrath of his brother's spirit, according to a number of scholars. This not succeeding entirely, the emperor tried to lift the curse by appeasing his brother's ghost, by performing Buddhist rites to pay respect, and granting Prince Sawara the posthumous title of emperor.

A well-known example of appeasement of the onryō spirit is the case of Sugawara no Michizane, who had been politically disgraced and died in exile. It was believed to cause the death of his calumniators in quick succession, as well as catastrophes (especially lightning damage), and the court tried to appease the wrathful spirit by restoring Michizane's old rank and position. Michizane became deified in the cult of the Tenjin, with Tenman-gū shrines erected around him.

Possibly the most famous onryō is Oiwa, from the Yotsuya Kaidan. In this story the husband remains unharmed; however, he is the target of the onryō’s vengeance. Oiwa's vengeance on him isn't physical retribution, but rather psychological torment.

Other examples include:

How a Man's Wife Became a Vengeful Ghost and How Her Malignity Was Diverted by a Master of Divination

In this tale from the medieval collection Konjaku Monogatarishū, an abandoned wife is found dead with a full head of hair intact and her bones still attached. The husband, fearing retribution from her spirit, asks a diviner for aid. The husband must endure while grabbing her hair and riding astride her corpse. She complains of the heavy load and leaves the house to "go looking" (presumably for her husband), but after a day she gives up and returns, after which the diviner is able to complete her exorcism with an incantation.

Of a Promise Broken

In this tale from the Izumo area recorded by Lafcadio Hearn, a samurai vows to his dying wife never to remarry. He soon breaks this promise, and the ghost of the deceased wife murders her husbands new young bride, ripping her head off. A watchman chases down the apparition, and while slashing his sword recites a Buddhist prayer, destroying the ghost of the dead wife.

44 notes

·

View notes

Video

While things have been a mess between the state of the world and personal life, I've still been spending as much free time between work as I could to finish the remaining scenes for my God Machine animation. I finished one of the more significant dialogue scenes for the film back in May. One of the many influences on the original plotline for The God Machine was old Japanese folk tales, most specifically how they were adapted in 60s horror films like Kwaidan and The Ghost of Yotsuya. That specific influence shows in the sequences involving the chancellor's priest henchman and the subsequent scenes of the chancellor experiencing paranoid hallucinations of the priest's ghost. In the 2021 Egregore workprint this sequence was just a few lines of text, now it's close to being fully sequenced.

For more posts about the making of my animation:

- My Twitter (where I sometimes give live updates on the film’s production)

- Trailer

- Violent Reincarnation

- Atrocity Driver

- The Putrified Ascetic

- Cemetery Metamorphosis

- March 2022 Production Log (Has a crap-ton of images from the film)

- Atrocities of War Painting

- Part-Time Death (Dialogue Scene)

- Prologue Scene

- Bits of the animation’s soundtrack

#guro#Guro Art#artist#horror art#horror animation#independent animation#macabre#animation#my art#artists on tumblr#horror

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ken Uehara and Kinuyo Tanaka in Yotsuya Kaidan (Keisuke Kinoshita, 1949)

Cast: Kinuyo Tanaka, Ken Uehara, Osamu Takizawa, Keiji Sada, Hisako Yamane, Jukichi Uno, Aizo Tamashima, Choko Iida. Screenplay: Eijiro Hisaita, Masaki Kobayashi, based on a play by Nanboku Tsuruya. Cinematography: Hiroshi Kusuda. Production design: Isamu Motoki.

Yotsuya Kaidan is one of the most famous Japanese ghost stories, put in classic form in the kabuki drama written by Nanboku Tsuruya in 1825. But in adapting the tale of a ronin, a masterless samurai, pursued by the vengeful phantom of the wife he murdered, Keisuke Kinoshita and his screenwriters, Eijiro Hisaita and the uncredited Masaki Kobayashi, jettisoned the supernatural elements to turn it into a psychological drama with overtones of Shakespeare tragedy: the ambition of Macbeth and the jealousy of Othello, abetted by an Iago-like villain. The ronin of Kinoshita's film, Iemon Tamiya (Ken Uehara), was dismissed by his former master for failing to guard the storehouse from a thief; he now ekes out a living with his wife, Oiwa (Kinuyo Tanaka), making and selling umbrellas. But while drowning his sorrows in sake one evening, he is approached by Naosuke (Osamu Takizawa), who plants in him the idea of wooing the wealthy Oume (Hisako Yamane), whose father has the connections that would enable him to find a master and restore his status as a samurai. Naosuke also plots with Kohei (Keiji Sada), with whom he served some jail time, to woo Oiwa, with whom Kohei has been infatuated since the days when she worked in a teahouse. Kohei's attentions to Oiwa arouse Iemon's jealousy, which Naosuke plays upon. As the prospect of marrying Oume becomes more likely, Iemon is given a poison to use on Oiwa, but he's initially reluctant to go that far. When Oiwa accidentally scalds her face, producing a horrible disfigurement, Naosuke provides an "ointment" that puts her in terrible pain and Iemon administers the poison. In the turmoil that follows Oiwa's death, Naosuke also kills Kohei. Freed to marry Oume, Iemon finds himself tormented by a guilty conscience, and when he learns that Naosuke was the one who robbed the storehouse that led to Iemon's dismissal by his former master, he turns on the conspirator. A fiery conclusion results. Kinoshita released the film in two parts, the first running for 85 minutes, the second for 73 minutes. Part I is more tightly controlled, efficiently introducing its characters -- there are lots of secondary ones, including Oiwa's sister, Osode (also played by Tanaka), and her husband, Yomoshichi (Jukichi Uno), who provide a kind of grounding in normal life. Kinoshita is not as successful at marshaling all of the secondary plots in Part II, and I tend to blame the director's tendency to sentimentalize, including the search of Kohei's mother for her son, for the weaknesses in the later parts of the film. But he gives his characters depth -- there is more sympathy for Iemon in the film than in more traditional versions of the story, which has been filmed many times.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recently Viewed: Kenji Misumi’s Yotsuya Kaidan (1959)

[The following review contains MAJOR SPOILERS; YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!]

Yotsuya Kaidan is Japan’s most popular and frequently adapted ghost story. While the core premise is basically consistent from version to version—penniless ronin Tamiya Iemon falsely accuses his wife of adultery as a pretext to divorce her and marry a wealthier woman, culminating in violence, regret, and vengeance from beyond the grave—the precise details of the narrative vary wildly between cinematic interpretations.

Shintoho’s 1959 film (helmed by Jigoku director Nobuo Nakagawa), for example, is a relentlessly dark (albeit vibrantly colorful) and bleakly cynical morality play; the protagonist is casually cruel and unrepentantly vile, with his grisly fate framed as karmic justice that the audience is intended to enthusiastically applaud. Keisuke Kinoshita’s 1949 duology, on the other hand, depicts Tamiya far more sympathetically; despite his (thoroughly reluctant) complicity in the terrible crimes committed against his spouse, he’s motivated primarily by economic factors beyond his control and the corruptive influence of his slimy, manipulative, verminous “friend,” Naosuke. Indeed, it is implied that the “haunting” is merely psychological—a subconscious manifestation of the central character’s guilty conscience. (Ironically, this “social realism” makes Kinoshita’s movie feel more subversive and revolutionary than Nakagawa’s comparatively lurid and gory effort.)

Kenji Misumi’s radically revisionist spin on the classic tale, however, probably takes the most liberties with the surprisingly malleable source material. Here, Tamiya (played by megastar Kazuo Hasegawa—which goes a long way towards explaining the particular “quirks” in his portrayal) is borderline heroic—an archetypal gruff-yet-chivalrous swordsman cut from the same cloth as Zatoichi and Tange Sazen. He’s also so passive and devoid of agency that he resembles the eponymous “specter” in Hammer’s The Phantom of the Opera, remaining virtually blameless for the (unnecessarily convoluted) series of events that result in his tragic downfall. He’s totally unaware of Naosuke’s devious conspiracy to humiliate, defame, and ultimately murder his wife, and although he still participates in an extramarital affair, the relationship appears to be purely transactional (and may not be overtly sexual; the extent of the “lovers’” physical intimacy is left deliberately ambiguous)—driven to desperation by poverty, he only indulges his mistress’ affections in exchange for money and lavish gifts. The editing, in fact, at one point explicitly juxtaposes his infidelity with that of his sister-in-law, who works part-time as a “waitress” at a “bathhouse” in order to supplement her husband’s meager income. Naturally, Tamiya’s relative “innocence” completely recontextualizes the story’s climax and denouement; whereas the character usually suffers an appropriately shameful, pathetic, undignified demise, Misumi allows him to achieve a measure of redemption via his glorious, honorable, beautiful death—sprawled at the feet of a bronze Buddha statue, wrapped in his wife’s favorite kimono, bathed in heavenly sunlight.

Pulpy, unsubtle, and unapologetically melodramatic even by Daiei’s standards, Yotsuya Kaidan isn’t the “best” adaptation of the original kabuki production, but Misumi’s various audacious departures from the “traditional” formula certainly distinguish it as one of the most interesting, unique, and undeniably compelling. For fans of chanbara and J-horror alike, it is essential viewing.

#Yotsuya Kaidan#Yotsuya Kwaidan#Ghost Story of Yotsuya#Kenji Misumi#Kazuo Hasegawa#Daiei#Japanese film#Japanese cinema#Japanese horror#J-horror#J horror#chanbara#Film Forum#chambara#film#writing#movie review

0 notes

Text

Ronin + folklore + ghost stuff

Compilation of a Twitter thread I did a couple days ago:

Here by popular demand, it’s time to talk Japanese folklore and ghosts in #StarWarsVisions RONIN! I’m going to keep it spoiler-lite, but there will be some vague references to characters, world, and themes.

One of the first things I did upon being offered this project was sit down and start listing folkloric entities and concepts that I wanted to see translated into Star Wars.

For example, my eternal favorite, Yamamba/Yama-uba the mountain hag, a ravenous old ogre woman known for devouring travelers and their wagons alike. Conversely, she’s also the doting adoptive mother of Kintarou, the golden boy, a child of the forest who grows up wrestling animals and eventually becomes Sakata no Kintoki, a loyal retainer to Minamoto no Yorimitsu.

Kintarou exists in a kind of historical-folkloric gray space, similar to Benkei, a warrior monk who I also deeply wanted to use but couldn’t ultimately find room for.

Benkei is famous for taking issue with samurai—these jerks and their swords, forever betraying their moral responsibilities! He vowed to duel and overcome 1,000 samurai, taking their swords as his trophies. He reached 999 before he met Minamoto no Yoshitsune and (you guessed it), became his loyal retainer, having been awed by his martial prowess and moral resilience.

You can see how Benkei’s whole deal kind of shows up in one of the RONIN cast members, though I idly headcanon that there’s a Benkei equivalent out there in the RONIN universe, beating up Jedi and Sith alike…

Now for an entity that DID show up: kitsune. Fox spirits in China and Korea are more consistently wicked and untrustworthy, but they’re more likely to be ambiguous or even straight-up benevolent in Japanese tales. Notably, kitsune may still possess a person and drive them cuckoo bananas, or maliciously trick them, but they’re also associated with Inari, a Shinto deity of harvest and good fortune.

As masters of illusion and shapeshifting, they can also be somewhat gender ambiguous. A kitsune may appear as a man, a woman, or…? Which is to say that I knew right off the bat that a kitsune character would be either nb or genderfluid.

Another one I wanted to bring in but couldn’t find room for: GASHADOKURO. Giant skeletons! “Gashadokuro mech” is somewhere in my notes and I’m still sad that I couldn’t figure it out. Gotta wait until THE ARCHIVE UNDYING for giant bone mecha I guess. There’s a famous triptych of Takiyasha, a rebel princess, summoning a gashadokuro in an act of girlboss witchcraft to come eat the emperor’s loyal vassals, who are begging her to stop rebelling, please.

Speaking of women becoming ungovernable, onryo, vengeful spirits, are kind of curse-like in their existence. The J-Horror “The Grudge” is just “Onryo” in JP, if that gives you a sense of how sticky these hauntings can get. Onryo are usually women, and they often share some visual features—think of that omnipresent Japanese ghost hair, long and wild, creeping everywhere… (Or ask my wife what it’s like to share a living space w/me when my hair’s long.)

Probably the most famous onryo in classic literature is Oiwa of Yotsuya Kaidan, a kabuki play about a woman wronged by a samurai, whose yearning for vengeance haunts him until his dying day…

Ghosts aren’t solely vicious, frightening entities, however! Obon is the yearly ghost festival where we welcome the dead back to our homes, rejoice in their arrival, and strive to send them back on their way. There’s dancing, festival foods, and lots and lots of light—lanterns, bonfires, the works—all to help guide the spirits of the beloved lost on their way to where they belong.

As for where else spirits and so forth belong…mountains. Strange things happen in the mountains, you know! As a mountainous archipelago you’d think that means strange things happen EVERYWHERE, but, well. There is the village, and there’s what lies beyond the boundary. Look for the points of transition. Torii shrine gates, stairs, bridges…

That’s all for now. Enjoy digging through Ronin’s secrets—and if you need more folklore, check out Tono Monogatari, Hyakki Yagyo, and Bakemono no e!

Extra: I just remembered that I thought about the cross-section of tsukumogami and droids. Household items that have been around for one hundred years may become tsukumogami—a sort of animate inanimate object. Frequently depicted as umbrellas or sandals or lanterns, etc.

57 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Ghost of Oiwa, Katsushika Hokusai, c. 1831-1832, Minneapolis Institute of Art: Japanese and Korean Art

Ghost tale of Iwa is a famous story based on the real event, known as "Yotsuya Kaidan (Ghost Tale in Yotsuya)", later had been made a Kabuki play by Tsuruya Nanboku. An unemployed samurai, Iemon married Iwa, a daughter of a warrior family looking for a man who can succeed their family name. After the marriage, he poisoned and killed his wife, and was haunted by the ghost of his wife.

Size: 10 3/8 × 7 7/16 in. (26.3 × 18.9 cm) (image, sheet, vertical chūban)

Medium: Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/65717/

32 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I don't really see/know about anything related to this but... I saw an amazing MAD of a song by Symag and after getting super interested and some searching I found the anime was called Mononoke and the main character was called Medicine Seller. So, um, can you please introduce me a little bit to this anime? Is there a manga? Is it available in YouTube? Thank you so much. And I hope I am not taking your time. <3

Hello! Thank you for stopping by my inbox! I never mind answering questions, especially from new fans! I saw this yesterday morning and meant to answer it in the afternoon but my head is a sieve at that hour, so whoops!

Let's see. Mononoke follows the adventures of the nameless immortal Medicine Seller as he tracks down mononoke, chuthulian creatures that prey on negative human emotions like loss, hurt, greed and desire, in urban Edo era Japan. Only after discovering the mononoke's Form, Truth and Reason will his demon slaying sword be unlocked and his true power released.

So some background. In 2006, Toei released a series called Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales. It was an anthology series with three different arcs based on traditional Japanese horror, each produced by a different set of staff in three very different styles. The first arc was an adaptation of the famous ghost story Yotsuya Kaidan with character designs by Yoshitaka Amano (eps 1-4), the second was based on a play called Tenshu Monogatari (eps 5-8), and the third is the Bakeneko arc and the first appearance of Kusuriuri (eps 9-11). That arc was so popular the team was given the greenlight to create Mononoke in 2007 and it received extensive praise for its storytelling and visual style which used a lot of technology that was groundbreaking at the time.

Although it didn't receive a lot of popular attention outside Japan, it was still big enough to get a manga adaptation with art by Ninagawa Yaeko from 2007-2008 and 2013~2016. Unfortunately the manga hasn't been licensed outside Japan and only the first two volumes or so have been fan translated ┻┻︵ヽ(`Д´)ノ︵┻┻

As of writing this, high quality fan subs of Ayakashi and Mononoke are currently available on YouTube thanks to Stormy Night and TINAW (shoutout to both of you!) although they're not difficult to find on most free anime streaming sites either (tho as always I recommend a good firewall and a secure browser like Brave). Both are also licensed and have DVD releases and may be available on Crunchyroll or whoever is streaming anime officially these days although I don't bother with them. Personally I'm not a fan of the licensed subs, I think they portray the Medicine Seller as a colder character than the fansubs and don't capture the nuance of a lot of the dialogue well and don't come with notes to explain some of the details.

And that's a thing about Mononoke. There's a LOT of detail going on under the surface. It's incredibly visually rich and there's a lot of subtext you're going to miss the first or even second or third times watching it. It can be an intimidating series to watch, especially if you're not familiar with Japanese history or culture or folklore or theatrical traditions because it draws very heavily from all of them. But honestly that's probably one of the reasons I love it so much, it's incredibly rewarding to come back to and catch something I missed or forgot about or learned about since watching it the last time. I saw it a few months after it first came out and have been researching everything I can about it since then so to me it's been very inspiring.

I know this is a Lot and I'm not sure I've been clear since I'm running on hunger brain rn but I hope I at least answered most of your questions! If not, my inbox is always open and I'm always happy to answer questions (provided I don't forget about them, sorry to everyone whose asks I've not addressed! (;ŏ﹏ŏ)) Anyways, I hope you enjoy the show and decide to stay for the blogs! Happy watching and safe travels!

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Utagawa Toyokuni. Onoe Matsusuke as the Ghost of the Murdered Wife Oiwa, in A Tale of Horror from the Yotsuya Station on the Tokaido Road. 1812.

#utagawa toyokuni#onoe matsusuke as the ghost of the murdered wife oiwa#tale of horror from the yotsuya tation on the tokaido road#edo period#19th century#ukiyo-e#japanese woodblock print#metropolitan museum of art#magictransistor#alejandromerola#1812

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan Onoe Matsusuke as the Ghost of the Murdered Wife Oiwa, in "A Tale of Horror from the Yotsuya Station on the Tokaido Road"

1812

Utagawa Toyokuni I Japanese

The Met

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

The myth of Oiwa - the paper lantern ghost

The myth of Oiwa - the paper lantern ghost is one of the most known #ghost stories in #japan. Click to have a read! :D #paranormal #haunted #moonmausoleum.

The ghost of Oiwa manifesting herself as a lantern obake. From the series One Hundred Tales (Hyaku monogatari). From the classic ghost story Yotsuya kaidan. Print by Katsushika Hokusai. 1830

Once upon a time, there was a beautiful young woman who died. She went on a murderous rampage and she forever haunts the place of Yotsuya. The end.

A common enough beginning. Might even be a common…

View On WordPress

#a ghost story#asia#curse#darkdreamsbooks#featured#Ghost#haunted#haunting#hungry ghost#japanese#japanese ghost story#lantern#macbeth#moonmausoleum#murder#oiwa#onryo#poison#revenge#ronin#samurai#scourned wife#the ghost story of yotsuya#vengance#yotsuya kaidan

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Regina watches Over Your Dead Body (2014)

Shibasaki Ko’s second Takashi Miike-directed horror film, after One Missed Call (aka Chakushin Ari).

If you want to watch this you’d do well to understand that it explores, in gory detail, issues with reproduction, and contains, in addition to jumpscares, blood, and violence, scenes of cannibalism, rape, and self-mutilation. There’s a good bit of mind screw, as well.

Summary of the film: On the set of a stage adaptation of Yotsuya Kaidan, the lives of the players start to merge with the events of the play.

Here are my short reactions as I watched, with spoilers:

- one minute in and you can always count on Japanese media to have super-realistic sex sounds... oh look you can't actually see anything but SK's jawline, that's nice

(It’s a bit brain-breaking to realize that at this moment, I have both this film and Scoop! on my hard drive, and that both begin with sex scenes featuring Shibasaki Ko and Fukuyama Masaharu. Way to branch out, both of you.)

- SK's character, Miyuki, seems to be affected deeply with ennui...

- I'd be more bothered by this creepy music if I actually thought something bad was going to happen, but it's too early for that

- twelve minutes in... this is so... artistically... slow...

- the set pieces are very pretty, if also disturbing in subtle ways

- rivalry between Miyuki and a debutante character, subtext being the young woman will try to surpass her idol and/or steal her man

- creepy doll is crying yikes

- I don't think that counts as a jumpscare, but that was... unexpected

- took forty-five minutes in before any weird stuff started happening, hah

- Miyuki wears a lot of metaphorical masks

- waiting for the inevitable jumpscare gosh

- and there's the jumpscare

- a break to look at the Wikipedia entry and IMDB... oh, Takashi Miike also directed Chakushin Ari, but that moved much faster; at least I kind of know exactly what to expect though in terms of the horror

- she covered her entire apartment in plastic for the inevitable blood splatter, how perfectly rational

- there are some incredibly subtle details in this film that up the horror significantly, with one major example being the repeated motif of insects: huge murals of centipede-like patterns and a very large cricket covering a lantern

- at about twenty minutes from the end, youngest was interrupting me a lot and I was trying to figure out what was going on, but I think I figured it out:

Miyuki was possessed by the ghost of the tale that is being adapted to the stage play she's performing in, leading her to take revenge on her lover, both in the play and in real life.

I wish I could have more astute commentary on SK's propensity to star in films like these, but all I can say is that it's interesting to watch the monstrous women she likes to portray and how they grab power for themselves through violent means. Perhaps it says more about Takashi Miike's desire to show these women on screen, because this is the second film of his I've watched where horror is the vehicle for this kind of power. In both Chakushin Ari and this film, the women succeed in their ultimate goals. Miyuki literally has her lover's severed head under her foot in the final scene of Over Your Dead Body and it's a compelling and succinct image to end on, and definitely hammers home the theme.

#regina watches#over your dead body (2014)#shibasaki ko#film#horror cw#stylistically this was much better than chakushin ari but japanese horror is not my thing at all#gif set forthcoming

1 note

·

View note