#peter biskind

Text

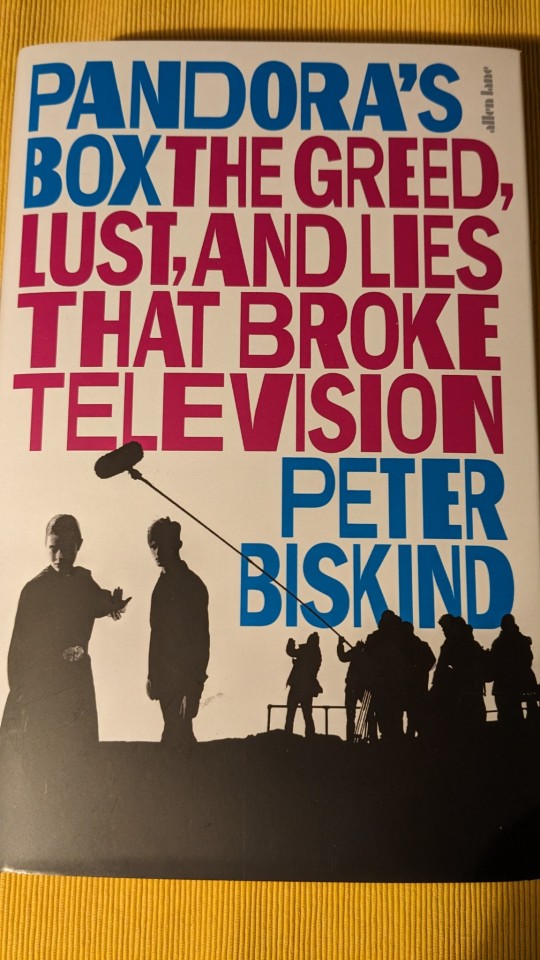

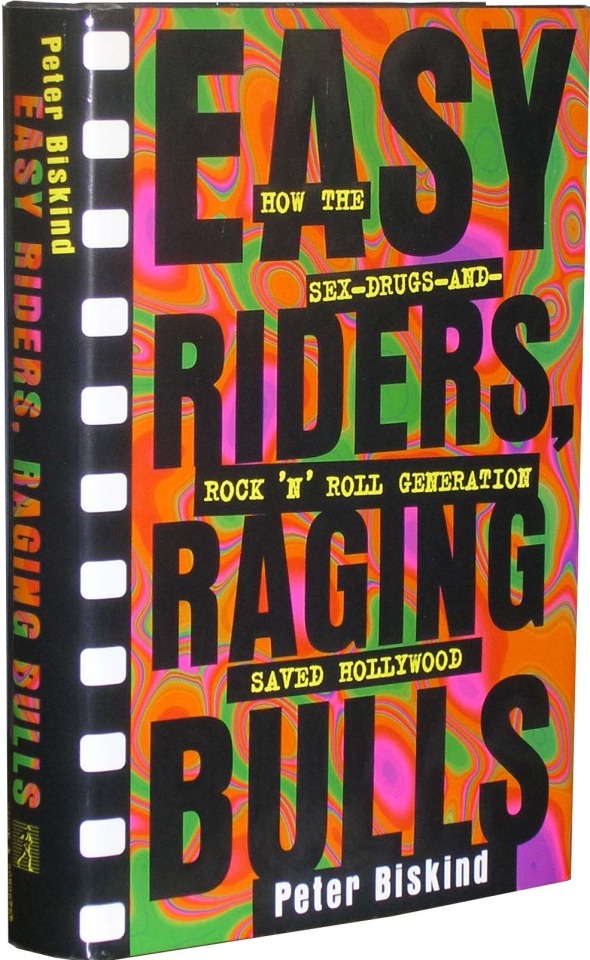

When it comes to Hollywood historians or cultural critics, Peter Biskind is in a class by himself. Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock 'N Roll Generation Saved Hollywood was a fucking joy to read. So I am very much looking forward to diving into this.

@gotankgo You in? 😂

#peter biskind#pandora's box: the greed lust and lies that broke television#hollywood#hollywood history#streaming#tv#tv shows#cultural criticism#books#reading

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stone Raids Wall Street

Once upon a time Oliver Stone was best known for his scabrous screenplays for films such as Scarface and Year of the Dragon. Then his 1986 films, Platoon and Salvador, racked up a slew of Academy Award nominations, and Platoon collected Oscars for direction, editing, sound, and Best Picture. Stone was honored not for safe, Masterpiece Theatre-type films that make Academy members feel good about themselves, but for violent, unpleasant films on subjects considered until recently to be box-office poison—Central America and Vietnam. In one short year, he has emerged as the most interesting and important director in Hollywood. Nevertheless, as no one knows better than Stone, the winds of celebrity are fickle, and when we spoke with him in August, he was anticipating a more qualified reaction to his forthcoming film, Wall Street.

Q: How did you get the idea for Wall Street?

A: The story first came to me while I was writing Scarface. Its get-rich-quick Miami mentality had certain parallels in New York, where an acquaintance of mine was making a fortune in the market. He was like some crazed coke dealer, nervously on the phone nights trading with Hong Kong and Lon- don, checking the telex, talking about enor- mous sums of money to be won or lost on a daily basis. His lifestyle was Scarface North. He had two huge Gatsby-like houses on the beach in Long Island (he couldn’t decide which one to live in), several dune buggies, cars, Jeeps, a private seaplane company, an art collection, and a townhouse in Manhattan. Then he took a giant fall; his empire came crashing down around him. He was suspended from trading; he lost millions and spent millions more in legal fees clearing his name, which he finally did. It made him a different, stronger person as a result, and it was partly this tale of seduction, corruption, loss, and redemption (as well as other stories we heard on the street, among them that of David Brown, a broker convicted for insider trading who served as an adviser on the film) that was the basis of Charlie Sheen’s character in our script.

Q: Wasn’t your father a broker?

A: Yes, he was on Wall Street for 50 years or so. My father’s world was very intimidating to me; I viewed it from an Orson Welles perspective out of The Magnificent Ambersons. | remember the staircases and mirrors. I remember looking down through banisters at Mom’s parties, at the rich people, the sophisticated people, women from Europe with accents, Belafonte or Sinatra on the phonograph singing ‘50s songs. Then they’d go out in packs like in La Dolce Vita to faraway places like El Morocco.

Dad would take me to the movies (how rare to be alone with him)—Dr. Strangelove, Paths of Glory, Seven Days in May—the ones with the ideas, and inevitably he’d come out of the movie and say, "Well, we could've done it better, Huckleberry,” and he’d tell me all the reasons why this plot was silly or illogical. It would make me think, which is one of the things a father is supposed to do. And he’d always say they never did intelligent pictures about businessmen; businessmen were always satirized or were stereotypical bad guys.

Dad believed very strongly in capitalism. Yet the irony of it all was that he never really benefited from it. All his life money was an overriding con- cern. But he never owned a single thing; every- thing was rented, right down to the cars, the apart- ments, and if it had been possible, the furniture. There was an insecurity at the heart of our family existence. I began to resent money as the criterion by which to judge all things, and there grew to be a raging battle between my father and me about it. I found ways to throw away everything I had, which pissed my father off. | went to Yale but dropped out, and he lost the tuition.

We reconciled before he died [in 1985], but by then I had moved away from it all. I didn’t want to go to an office every day from nine to five. I didn’t understand Wall Street. “Going into movies is crazy,” he would say. “You aren’t going to make a dime.”

When I was working on Wall Street, I felt my dad was sort of around in a ghostlike form, watching over me and laughing, because here is the idiot son who doesn’t know anything about the stock market, who can barely add and subtract, doing a film with the grandiose title Wall Street.

I always hated New York, which is what made it so special returning some 25 years later with a crew of professionals, a self-contained artillery unit. (I even got to cast Hal Holbrook, who is everybody’s dream of a father, as my father.) And suddenly | got a glimpse of a mysterious world I'd only scratched the surface of as a child—the adult world, New York in its power, glory, and greed.

Q: You're not dealing with war and revolution in Wall Street, as you were in Platoon and Salvador. It’s a less weighty film.

A: It appealed to me precisely because it is a lesser statement. There is only so much you can say about yuppies. I knew if I sat around for two or three years doing a Hamlet number - should I give the world another film? - I would really drive myself crazy. I would rather turn something out fast, get it over with, give the gold crown to somebody else so I can get on with doing things that I really care about, which are ideas. I’m ready to take a fall. I'm not expecting the same critical praise or the same box office that I got for Platoon.

I think I have always been identified with “‘lowercase”’ films that take people by surprise. It is strange suddenly to be in a front-runner position with Wall Street. I like being a dark horse. Celebrity can hurt the creative process if you let it go to your head. You start weighing your image of yourself instead of somehow keeping your head low down to the ground like a bulldog, telling a good story, and not letting your ego stand in your way.

Q: How did you get a producer for Wall Street?

A: Initially, I brought the script to John Daly at Hemdale. But he didn’t think the audience would go for a movie about people who were making millions of dollars. On the other hand, Ed Pressman and Twentieth Century Fox loved the idea, which was fine with me, because Wall Street was going to have to be shot in New York, and consequently it was going to be expensive. Hemdale is not really into $15 million movies; it would have been a big risk for them and more pressure for me, whereas for Fox it is a medium-budget movie.

Q: Did you get any cooperation from Wall Street?

A: Initially, no. They felt Stanley Weiser (the co- writer) and I were going to trash the Street. Then after the success of Platoon, people started coming out of the woodwork. We hired Ken Lipper, who was formerly the deputy mayor of New York City and was managing director of Salomon Brothers, and we consulted with people such as John Gutfreund of Salomon, and Carl Icahn.

Q: How did the consultants help you?

A: Ken Lipper put Charlie Sheen and Michael Douglas inside Salomon Brothers. He also got us into places like The 21 Club, Le Cirque, and, most important, the New York Stock Exchange, which was a first. No film had ever been done there. We actually shot on the floor while they were trading. A lot of the older traders were upset because they were trying to make money and we were creating a disturbance, but there were many more Vietnam veterans on the floor than I had imagined, and they had seen Platoon.

Ken was also on the set. He helped us with details: how brokers deal with sales, how they write up orders, their body language—how they hold a telephone, what is the pace of the conversation. I had no clue how these things are really done.

Q: What was it like to shoot in New York?

A: Sixty-ninth Street and Madison was a fucking mess. Michael Douglas was shaking hands all day. Bill Murray came by, actors, businessmen, kings, diplomats—it was a constant stream of Hi Daryl [Hannah], Hi Michael, Hi Charlie. We'd try to shoot a scene and there would literally be a thousand people coming to look. It was impossible to work under those conditions. So | hired about 200 extras and filled the sidewalk with them so we could control the streets. If anybody walked onto that sidewalk they would see all these people standing stock still waiting for the cue for action. It was so bizarre, they would skirt the sidewalk and walk away.

And here’s an example of how unions can fuck up reality. | wanted real derelicts, but there’s a law in New York that the first 125 extras in major feature films have to be union. We made up the extras, but they never looked real. So if I need a real bum in a scene it has to be the 126th man. I just threw up my hands in disgust. My derelicts will have to go in my next picture

Q: Why did you cast Charlie Sheen in the lead role?

A: | thought that he could do a good job of playing a bad boy, showing the negative side of Wall Street. There is a devilish side to Charlie that didn’t come out in Platoon, where he was more of an idealized figure. I think he’s been in trouble, and that shows in his personality, a strong streak of rebelliousness combined with an inner grace passed on from his father, Martin Sheen, who plays his father in the film. Charlie is only 22, which made him much younger than the brokers being busted on Wall Street, but we aged him with good suits, a haircut, and he gained a little weight from the good life in New York; his face is a little jowlier than normal. He invested his own money in the market, hung out with the young brokers at Bear Stearns and Salomon Brothers, drank with them at the South Street Seaport, kids just out of college who have to pull $100,000 in the first or second year just to occupy a space on the floor. Gone are the days of my father, when people were brought along slowly; there seems to be less mercy in the system, and as always the corruption is subtle, almost undetectable in a black and white sense. The corruption of all flesh—needing more and more, until like fat bugs we pop and bleed all over the page.

Q: I understand Charlie’s character was Jewish in the first draft of the script. Why did you change it?

A: His name was Freddie Goldsmith, but that would have necessitated a different kind of actor. I would never have believed Charlie as Jewish; he doesn’t have that kind of quickness, the mannerisms, the nerviness. He is more of a laid-back type; at best he could play a Catholic, Protestant out of Queens. I also wanted to drop the Jewish angle because I think that too many people think that Wall Street is run by Jews and that they are all corrupt, a bunch of gangsters. I just didn’t want to give them any more fuel. My father— who was Jewish, I’m half Jewish— always warned me that I would probably see a pogrom in the United States in my lifetime. I didn’t believe him when I was a kid. I believe it now.

Q: Did you have Daryl Hannah in mind from the beginning?

A: I've loved Daryl from way back. She’s an admirable person with a real passion for left-wing causes. And she looks beautiful on film. She’s the kind of girl a guy like Charlie would go after. She would be the type of girl who is pretty enough to be around the big money guys. Daryl had problems with her character because it wasn’t a character she particularly liked. She was scared by it. She is a natural, simple girl, and here was a character who was totally artificial. She had a major problem trying to learn that language. She went to a voice coach in New York and tried to change her flat Southern California/Chicago accent into something more nasal, more New York, upper class, and affected. I was tough with her. I beat her up, in a metaphoric sense, and in the early stages I am sure she wanted to quit. I think I made her cry a few times, but I wasn't really pleased with her wanness and passiveness, which were difficult to get through. She needs a very, very strong director. I am not sure I succeeded.

Q: Weren't you taking a chance using someone like Michael Douglas, who’s never played a bad guy?

A: I was sort of worried about him because | had been warned by a highly placed studio executive that he would be in his trailer all day reading scripts and on the phone to Los Angeles. But he was always on time, never one minute late in the whole shoot, and very easy to work with as well. He seemed to be aware that it was a big role for him. He told me at one point that his dad had implied that he was finally about to become a real actor; that he had always played wimps, and that this was a role where he could play more toward his father, who could do a heel as well as a hero. Michael loved that idea.

I was amazed, for an actor who has done so many movies, how nervous he was in the beginning. He couldn’t believe it when on the first day I gave him three pages of monologue, like something out of Paddy Chayefsky. He'd never had speeches like that in his life. And then the second day I stuck a hand-held camera in his face about six inches from his eyeballs—he was on a plane, so I wanted to create a sense of movement. He said it was very difficult for him to act, to concentrate and remember his lines, staring at the camera. Then he hit his stride, and by the time we got to the scenes in his office, he was on top of his game.

Q: How do you prepare the actors?

A: In the rehearsal period I try to outline the context of the characters, what their inner life is about, what their backstory is. I try to help the actors suggest things and then let them run with those ideas. Then we have readings; you can see the way an actor is interpreting a role. Once we start filming, we relive what we did in rehearsal seven or eight weeks before. Often it comes out differently; nuances emerge because the material has been marinating in the actor's subconscious. I clear the set except for the actors, so that we keep it quiet. The rehearsal itself can take anywhere from 30 minutes to six hours, in the course of which it should become clear what everybody is looking for in the scene and how to play it. Whether they succeed doesn’t interest me; in fact, I'd rather that they didn’t do it and not spoil themselves emotionally before the cameras go on. Too often you have a good rehearsal and it never comes back.

Q: Do you improvise?

A: I always try to encourage spontaneity. I like to be surprised. Astonish me! It is easy to play a scene predictably; a director falls into that because he has to complete the film in a limited period of time. He can clock out all the spontaneity and all the truth. That is the hardest thing a director has to face; he has to stay fresh.

Q: What do you do when a scene isn't working?

A: I often deal with it by rewriting extensively on the spot. Part of that process includes listening to the actors. Some actors just can’t say certain words, or they will feel uncomfortable with a speech. They will say, “Gee, Oliver, do I have to say that line? Can’t I just do a look?”

Or I try to use the camera to respond to a mistake. You shoot the scene in such a way that you can cover the blemish. You change the angle, you move the camera. We did enormous amounts of moving camera in this film because we are making a movie about sharks, about feeding frenzies, so we wanted the camera to become a predator. There is no letup until you get to the fixed world of Charlie’s father, where the stationary camera gives you a sense of immutable values.

I generally work fast. | did Salvador in 50 days. I did Platoon in 54 days. | did Wall Street in 53 days. I came in seven days ahead of schedule and close to $2 million under budget. We never wasted an hour. If it rained, we made it a rain scene: Charlie goes to the beach in the rain. I hate waste. When I read about directors shooting a million feet, it makes me sick. They say film is cheap, but how can you sit there in the editing room and have to go through 30 or 60 or 95 takes? Ultimately, take 30 doesn’t look that much different from take 7. Usually after six or seven takes, I let it go. The most I ever did was nineteen takes.

Q: Do you relax in the editing room?

A: Hell, no. I tend to shoot three-hour movies and cut them down to two hours. My scripts are long; I blow a lot of my time shooting scenes that never get into the movie. We had 80 speaking parts in Wall Street. | will probably cut twenty of them. Editing to me is like a tremendous retreat, a march back from Moscow, a rout. When you are writing and directing, you feel like you’re on a perimeter, expanding. When you are editing you are withdrawing your perimeter as quickly as possible and trying to maintain the CP, the command position, because it is about to go under. Philosophically, it always seems to be that movies are about limitation. Every time I make a movie my original concept shrinks. It is a truth about movies that less is more, that sometimes when you try to do too much you get scrambled, you get killed.

Q: How would you describe the theme of Wall Street?

A: I wanted to concentrate on the ethics of the characters and see where they lose their way, where they lose their sense of values, where net worth starts to equal self-worth. I think Wall Street is really about the urban culture of the ’80s. The pressure is enormous on these young guys to produce. | think they are perverted right off the bat. Why would someone who is making $100 million have to make another $20 million? Because he has to stay ahead of the next guy. Money is a way of keeping score. A line in the script says it all: “How many boats can you water-ski behind?’ Ultimately, not about money, it’s about power.

There is something patently unhealthy in using money just to make money rather than to create value. How can you justify threatening to take over a company, then selling it back and making $40 million, meanwhile forcing the company to spin off its assets and lay off employees?

Q: Is there a remedy for insider trading?

A: Probably not. There is no question that outsiders don’t do as well as insiders. I have invested in the stock market now off and on for 30 years, and I never made any money at it. It is a privileged club, an oligarchical institution in which the rich talk to the rich. They don’t talk to the poor. A guy goes to La Céte Basque for lunch. He sees a CEO from some other company and tells him some piece of information about a company that’s going into semiconductors or something, and he is going to buy into it. That’s the way the system works. You read about these kids who are making a million bucks, two million bucks a year—it demoralizes the person making $40,000 a year. All of a sudden everybody needs a Porsche or a VCR or a fishing boat. And this is what fuels America, more and more greed. We deal with these issues by staying inside a very small story, one fish in one Wall Street aquarium and what happens to that fish. #

-Peter Biskind, "Stone Raids Wall Street," Premiere, Dec 1987 (Vol 1 Issue 4)

#oliver stone#peter biskind#premiere#wall street#charlie sheen#michael douglas#daryl hannah#judaism#new york#filmmaking#filming#editing

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Biskind’s take is less ambivalent: he gives us the sense that these are the guys who can really do it. That it is not a quirk of history that some Difficult Men made some great television, but that there is a link between the hard-driving, self-loathing, capricious, sometimes dictatorial approaches that some of that generation took and the quality of the shows.

This muddles correlation with causation. Making a big TV show, and making it good, is always going to involve some friction and pain. But it’s not the friction and pain that make it good. If you think it is, you are in danger of venerating the difficult and painful parts, rather than seeking to ameliorate and address them.

Who runs the show?

#jesse armstrong#peter biskind#tv#showrunner#review#Pandora’s Box: The Greed Lust and Lies That Broke Television

0 notes

Note

Hello! Is there a like… “old movies for dummies” guide you’d recommend? Film history for people who know next to nothing about anything? Extra points for emphasis on how film, American history, feminist history, and/or gay history co-evolved.

i haven’t read these ones so i can’t like technically recommend it, but the story of film by mark cousins seems to be a big one. film history: an introduction is written by david bordwell (RIP) and kristin thompson and their other book film art: an introduction (which i can recommend) is often the first book film students are assigned in class…. the thing about film history is that it’s so long and complex and you’re probably not going to find a catch-all one stop shop. i can say that you should pick up hollywood: the oral history by jeanine basinger and sam wasson, honestly ANY BOOK by jeanine basinger, the parade’s gone by by kevin brownlow, easy riders raging bulls by peter biskind, hollywood black by donald bogle. david thomson has a huge biographical dictionary on film that’s a fun read.

to answer your extra question…. again, i’m not thinking of anything that combines this all into a one stop shop, but you should absolutely read from reverence to rape by molly haskell, pretty much anything by judith mayne, and laura mulvey’s visual pleasure and narrative cinema essay for some feminist history (JSTOR has a great reading list here) and the celluloid closet by vito russo for gay history in film.

#asks#i hope this is helpful!#bordwell + thompson are probably a great place to start tbh#and once you know more about the periods of history that interest you most you can branch out from there

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

On November 21th, the @criterioncollection is releasing Mean Street on 4K UHD blu-ray!

DIRECTOR-APPROVED 4K UHD + BLU-RAY SPECIAL EDITION FEATURES

New 4K digital restoration, approved by director Martin Scorsese and editor Thelma Schoonmaker, with uncompressed monaural soundtrack

One 4K UHD disc of the film presented in Dolby Vision HDR and one Blu-ray with the film and special features

Excerpted conversation between Scorsese and filmmaker Richard Linklater from a 2011 Directors Guild of America event

Selected-scene audio commentary featuring Scorsese and actor Amy Robinson

New video essay by author Imogen Sara Smith about the film’s physicality and portrayal of brotherhood

Interview with director of photography Kent Wakeford

Excerpt from the documentary Mardik: Baghdad to Hollywood (2008) featuring Mean Streets cowriter Mardik Martin as well as Scorsese, journalist Peter Biskind, and filmmaker Amy Heckerling

Martin Scorsese: Back on the Block (1973), a promotional video featuring Scorsese on the streets of New York City’s Little Italy neighborhood

Trailer

English subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing

PLUS: An essay by critic Lucy Sante

New cover by Drusilla Adeline/Sister Hyde Design

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daniele Faraotti - Calano I Colli

Da venerdì 1° marzo 2024 sarà in rotazione radiofonica “Calano i colli”, il nuovo singolo di Daniele Faraotti già disponibile sulle piattaforme digitali dal 21 dicembre 2023.“Calano i colli” è un brano ispirato dalla risposta di Wells a Peter Biskind riguardo al collo che si rilassa con l’età, una metafora che si intreccia con la società moderna, la quale offre soluzioni preconfezionate a ogni…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

BOOK CLUB

2023 TOP TEN (ish)

Fiction

All The Sinners Bleed by S.A. Cosby

Small Mercies by Dennis Lehane

Trespasses by Louise Kennedy

I Have Some Questions for You by Rebecca Makkai

Tom Lake by Ann Patchett

Flags On The Bayou by James Lee Burke

Non-Fiction

Rough Sleepers by Tracey Kidder

Poverty, By America by Matthew Desmond

Women We Buried, Women We Burned by Rachel Louise Snyder

The Best Minds by Jonathan Rosen

Pandora's Box by Peter Biskind

0 notes

Text

Hugo Rifkind on Peter Biskind’s new book. There’s a parable for brand owners here.

0 notes

Text

Building a New Ben

Sick of Affleck? Our Five-Point Plan to Revive The World's Most Over-Exposed Actor

By: GQ.com

April 11, 2013 2003

Dear Ben Affleck,

So it's been a rough year. Girl problems. Work problems. Goatee problems.

Buck up, ya big poufy-haired lug! It may look hopeless now, but your career hasn't yet plunged into Jared Leto-ville. You're not waiting for a callback for Beethoven's 5th. Hardly anyone calls you "Casey Affleck's big brother." Paycheck? Don't worry—nobody saw it! Gigli? In theaters an hour and a half. And you're not the first fiancé to eat a $1.2 million pink-diamond engagement ring and a $350,000 Bentley. Tell it to David Gest, brother!

But the truth hurts: People are starting to not like you, Ben. You're polling lower than Dennis Kucinich. You're too chatty, too tan, too everywhere. The other night, we found you on Access Hollywood, Entertainment Tonight, E!, MTV, Animal Planet and the Jakarta Cricket Channel. You're so overexposed, you could walk into the White House with Iraqi WMD's under one arm and Osama bin Laden under the other and the public reaction would be: Not another friggin' Ben Affleck story. By the way, the Mars rover says they're sick of you up there, too (and they hated Daredevil).

We're frustrated because we know you have more to offer, Ben. You've done some good films—Chasing Amy, Shakespeare in Love, Changing Lanes... Pearl Harbor (just seeing if you're still paying attention, bro!). You've got that Oscar for Good Will Hunting. You can be shrewd and funny; you made the unwatchable _Project Greenlight _semiwatchable, and your quotes practically stole Peter Biskind's best-selling book, Down and Dirty Pictures: Miramax, Sundance and the Rise of the Independent Film. (At least you didn't kiss Harvey's big ass. And comparing yourself and Matt Damon to Saturday Night Live's Ambiguously Gay Duo—v. rich!) You _can _be likeable and real; you're not one of those capital-A actor types like Russell Crowe, who is probably still droning on somewhere about how he learned the violin for Master and Commander.

So it's time to get the Affleck act together. Before Byron Allen starts calling—and you answer. Before you're phoning Alec Baldwin for advice ("Kid, dump the Tom Clancy movies—they're never gonna make any money!"). Take our instructions, cut them out, stick them to the Sub-Zero in the Ben-chelor pad and read them every day before your private step aerobics-karate-Tai Chi class.

1. Go Away

Get out of Hollywood. Go someplace quiet and uninteresting. No, not the new John Sayles movie. Stay out of cinema, period. Go someplace the paparazzi won't dream of going. No, not Chris O'Donnell's house. Find someplace where you can think. And then, when you think of a reason you made Reindeer Games, keep thinking. Hard.

2. Shut the Hell Up

Kind of goes hand in hand with no. 1, but we want to make sure. Ben, you like to talk more than a bathroom full of I-bankers on a Friday night. So no more jibber-jabbering on Jay Leno, Conan O'Brien, Pat O'Brien, _Celebrity Poker Showdown _or Dinner for Twelve, or whatever it's called. In fact, stop talking to Jon Favreau for, like, ever. Most important: STOP TALKING TO DIANE SAWYER.

3. Do A Movie No one Expects

This one is tough. The big-ticket actor making the smart indie film is a cliché these days. We kind of cringe when we think of you playing a developmentally disabled person to get some James Lipton brownie points. At the very least, you should make a movie with—how's this?—a script! No more blockbusters, superheroes or sci-fi for eighteen months.

4. Fix the Look

No more baseball caps, and lose the goatee—we told you that four issues ago. And enough with the synthetic tans. You showed up at the Gigli premiere, looking like an overcooked Oompa-Loompa.

5. Find A Nice Girl

We can't fault you for Jennifer Lopez. Not even Carson Kressley would have said no. But you need to find yourself a woman who won't make you run out to the corner store for a Lamborghini. We have a couple of very nice editorial assistants here who'd be more than happy with a few cranberry vodkas and a ticket to the Shins.

We have some other suggestions, Ben. You might want to get fat. Not too fat—but maybe a little roly-poly, enough to punch and impress the Sunday-afternoon football crowd. You might want to speak with an accent. You might want to wear a cape. Finally, we have seven words for you if all else fails: Good Will Hunting II: Gooder and Huntinger.

Ben, we didn't vote you Actor of Our Generation, and Lord knows you didn't ask for this. But we're stuck with each other for a couple of decades, and we may as well make it work. You seem like a good enough guy, and besides, we don't see anyone else on the horizon. Unless Chris O'Donnell's making a John Sayles movie.

Go get 'em, kid!

Love,

Your friends at The Verge

0 notes

Link

#heath ledger#heathledger#vanity fair#michelle williams#terry gilliam#the dark knight#the imaginarium of doctor parnassus#the last of heath

1 note

·

View note

Text

I’m about two thirds of the way through Peter Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock 'N Roll Generation Saved Hollywood. Absolutely loving it and all the behind the scenes shenanigans concerning how movie making changed as the sixties gave way to the seventies while also illuminating the specifics of several productions. The oral histories are warts and all, putting a spotlight on some decidedly bad behavior among those directors highlighted within

#Easy Riders Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock 'N Roll Generation Saved Hollywood#read a book#book#Peter Biskind

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book 7, 2019: 'Down and Dirty' by Peter Biskind.

Miramax, Sundance and the rise of independent film.

Indie. Filmmakers. The other world of film business. Carnage. Controversy. The Weinstein brothers. Quentin Tarantino. Steve Soderbergh. Robert Redford. Prizes. Production. Film Festival.

Weltanschauung!

#bookporn#fiilm#harvey weinstein#weinstein#sundance film festival#sundance festival#redford#robert redford#done and dirty#peter biskind

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

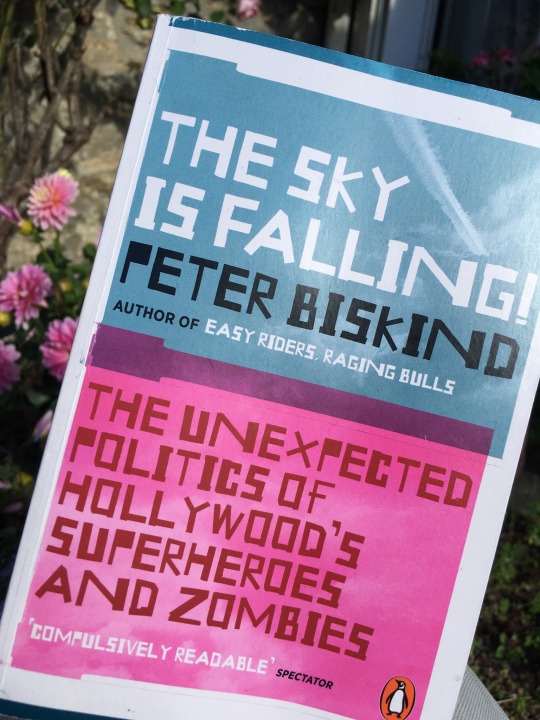

After skillfully analysing the US film industry of the 1970s (subversive New Hollywood) and the 1980s (where I learnt everything I need to know about Harvey Weinstein, a decade before the #MeToo movement) Biskind turns to today's connection between mainstream culture and world politics.

In a tiny nutshell, he draws a line - albeit blurry - between "extremist"/leftwing culture (diversity and acceptance) and rightwing/mainstream culture (traditional family values).

Just like his previous books, this is engrossing, insightful and entertaining.

Highly recommended to anyone with an interest in the movies! 🎬

0 notes

Text

In light of current events, I feel compelled to share this story about Alison Brantley, the former director of acquisitions of Miramax.

Working day to day with the Weinsteins in New York had gotten to Brantley, as it had to the others, and she had begged Harvey to let her operate out of the London office, an elegant townhouse on Redburn Street in Chelsea, between the river and Kings Road. One of her jobs was to babysit Day-Lewis, who became fond of her. His attitude was, She’s the normal person in this crazy company. Harvey would never have gotten through Granada’s doors had she not opened them, and he had somehow neglected to reward her with a bonus. She had never been to the Oscars and figured he owed her. After some prodding, he finally agreed to fly her to L.A. and pay for her hotel room, but he said, “Alie, I just can’t get you a ticket.” She replied, “Harvey, don’t worry. I’ll get one myself.” No sooner said than Day-Lewis gave her his extra ticket. When she arrived in L.A. the day before the ceremony, she got a call from Miramax publicist Christina Kounelias, who told her, “Uh, Harvey wants to talk to you.” Brantley, who had been astonished to see that the ticket was for the front row, next to Day-Lewis, couldn’t help recalling that Harvey had refused to let her sit next to Soderbergh at the closing ceremony in Cannes and understood right away he wanted to sit with the nominee. She replied, “I will be damned if he’s gonna get this ticket.” But she had indiscreetly disclosed Harvey’s intention to My Left Foot producer Noel Pearson, which Harvey discovered. It made him look bad, and he was furious. There was a meeting of Miramax staffers at the Beverly Hills Hotel at noon the next day. Harvey called her, bellowed, “You get yourself over here right now, down to this meeting.” She thought, Oh, shit, I’m in for it. I am not walking into that meeting with this ticket in my bag. I’m going to go to my hotel and lock it up. She imagined him pawing through her purse going, “Where is that ticket?”

Twenty minutes later Brantley walked into the Miramax suite. To her chagrin she realized that everybody of any importance at the company was there. She had expected a one on one, never imagining that they would drag her in front of the whole place. She thought, He’s just trying to spook me. Bob came over to her, put his arm around her, and said, “That was really dumb what you said to Noel. You must have either been stupid or disloyal. Which one was it?” She thought, This is like the Mafia. But not wanting to get herself into any more trouble, she said, in a small voice, “Oh, I guess I was really stupid.” Just then, the phone rang. It was Tom Pollock, head of Universal. Harvey took the call, put on his I’m-talking-to-somebody-important voice, and after he hung up, he looked at her and said, “People at Universal would get fired for less than this.” Bob put his arm around her again and walked her to the door. He was terrifying when he was being sweet. She thought, This is utterly creepy, and fully expected to hear him say, “Alie, you’re finished.” He didn’t, but she recalls, “In my heart I knew my days were numbered. You don’t stand up to Harvey.” None of the people in the room said a word in her defense. “They sat there watching like in a circus,” she adds. “Looking back on it, I wish I had said, ‘Fuck you!’ and walked out. The thing about working for them for me was, we weren’t raised to be like that. We were southern.” She never did give him the ticket. “I went, and I sat next to Daniel, and it was great.”

In 1990, Daniel Day-Lewis was nominated for Best Actor award for the first time. He could have brought anyone with him to the Oscars. His mother, his sister, his family, Isabelle Adjani, or any of those beautiful women he was linked with. Instead, he brought an employee of Miramax, who has been constantly bullied by her employer, the Weinstein brothers. DDL didn’t give her a lesser seat, but a front row ticket seating next to him, the very seat her boss was desperate to have. That’s DDL sending a “fuck you” message to Harvey.

I don’t know if he knew or how much he knew but you see, DDL didn’t make empty statements. He acted. And his action was subtle and as harmless as possible and the one that made the victim feels like the winner. What made this story more sweet, DDL did win (as the youngest actor ever won Best Actor at the time) and she got to celebrate the win next to him.

#daniel day lewis#alison brantley#harvey weinstein#oscars 1990#ddl story#peter biskind#down and dirty pictures#*#he's the knight in shining armor#i thought he went alone#he didn't kiss anyone when they announced his name#and he is the kissing machine#also she didn't get fired for this ok#and i'm sick of talking about harvey#so this is probably the last one

100 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Down and Dirty Pictures

1 note

·

View note

Text

What Our Extremist Politics Owe to Batman and Captain America

What Our Extremist Politics Owe to Batman and Captain America

Author: Patton Oswalt / Source: New York Times

THE SKY IS FALLING

How Vampires, Zombies, Androids, and Superheroes Made America Great for Extremism

By Peter Biskind

252 pp. The New Press. $26.99.

It’s too soon for this book is the problem. Peter Biskind has previously explored pop culture and film history in fizzy, captivating works, including “Easy Riders, Raging Bulls” and “Down and Dirty…

View On WordPress

#Batman#Bela Lugosi#Captain America#Christopher Nolan#extremism#Frances Dade#Peter Biskind#politics#The New Press#Universal Pictures

0 notes