#prisons are US slave plantations

Text

#african/black experience#war on afrikans#afrikan#terrorism#protest#revolutionary#racial profiling#violence#freedom#RUCHELL CINQUE MAGEE#Marin County Courthouse Rebellion#Afrikan abolitionist#13th Amendment to the US Constitution legalizes US slavery#prisons are US slave plantations

0 notes

Text

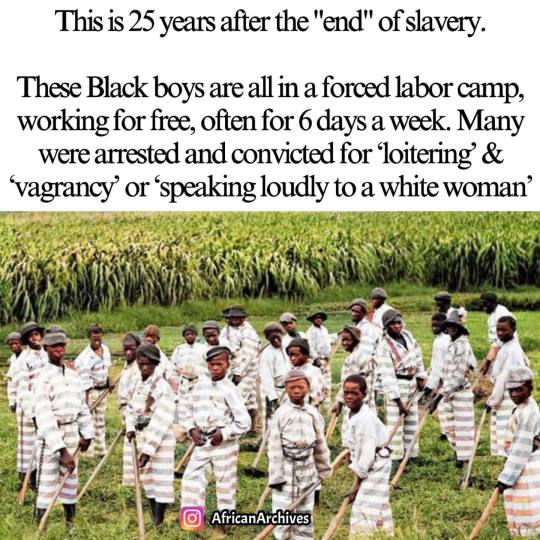

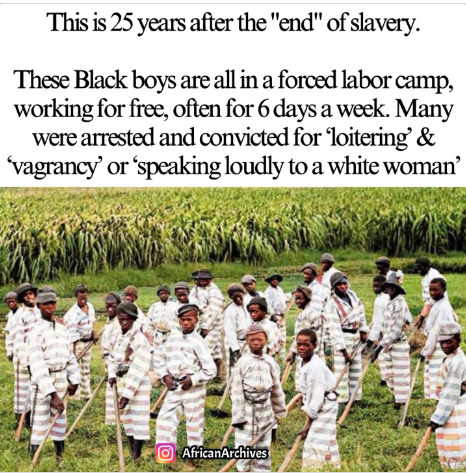

In 1865, enslaved people in Texas were notified by Union Civil War soldiers about the abolition of slavery. This was 2.5 years after the final Emancipation Proclamation which freed all enslaved Black Americans.

But Slavery Continued… In 1866, a year after the amendment was ratified, Alabama, Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, Florida, Tennessee, and South Carolina began to lease out convicts for labor.

This made the business of arresting black people very lucrative, thus hundreds of white men were hired by these states as police officers.

Their primary responsibility being to search out and arrest black peoples who were in violation of ‘Black Codes’

Basically, black codes were a series of laws criminalizing legal activity for black people. Through the enforcement of these laws, they could be imprisoned.

Once arrested, these men, women & children would be leased to plantations or they would be leased to work at coal mines, or railroad companies. The owners of these businesses would pay the state for every prisoner who worked for them; prison labor.

It’s believed that after the passing of the 13th Amendment, more than 800,000 Black people were part of that system of re-enslavement through the prison system.

The 13th Amendment declared that "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

Lawmakers used this phrase to make petty offenses crimes. When Blacks were found guilty of committing these crimes, they were imprisoned and then leased out to the same businesses that lost slaves after the passing of the 13th Amendment.

The majority of White Southern farmers and business owners hated the 13th Amendment because it took away slave labor. As a way to appease them, the federal government turned a blind eye when southern states used this clause in the 13th Amendment to establish the Black Codes.

#slavery#emancipation proclamation#black americans#convict leasing#black codes#13th amendment#involuntary servitude#prison labor#re-enslavement#southern states#racial discrimination

661 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1865, enslaved people in Texas were notified by Union Civil War soldiers about the abolition of slavery. This was 2.5 years after the final Emancipation Proclamation which freed all enslaved Black Americans.

But Slavery Continued… In 1866, a year after the amendment was ratified, Alabama, Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, Florida, Tennessee, and South Carolina began to lease out convicts for labor.

This made the business of arresting black people very lucrative, thus hundreds of white men were hired by these states as police officers.

Their primary responsibility being to search out and arrest black peoples who were in violation of ‘Black Codes’

Basically, black codes were a series of laws criminalizing legal activity for black people. Through the enforcement of these laws, they could be imprisoned.

Once arrested, these men, women & children would be leased to plantations or they would be leased to work at coal mines, or railroad companies. The owners of these businesses would pay the state for every prisoner who worked for them; prison labor.

It’s believed that after the passing of the 13th Amendment, more than 800,000 Black people were part of that system of re-enslavement through the prison system.

The 13th Amendment declared that "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

Lawmakers used this phrase to make petty offenses crimes. When Blacks were found guilty of committing these crimes, they were imprisoned and then leased out to the same businesses that lost slaves after the passing of the 13th Amendment.

The majority of White Southern farmers and business owners hated the 13th Amendment because it took away slave labor. As a way to appease them, the federal government turned a blind eye when southern states used this clause in the 13th Amendment to establish the Black Codes.

This is more American History that Republicans do not want taught in school.

Republicans cannot rewrite history. They are fools if they think they can.

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

IF YOU DIDN'T KNOW THIS YESTERDAY THEN TODAY WOULD BE A GOOD DAY TO LEARN THIS.... "All stories don't have a happy ending"

In 1866, one year after the 13 Amendment was ratified (the amendment that ended slavery), Alabama, Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, Florida, Tennessee, and South Carolina began to lease out convicts for labor (peonage). This made the business of arresting Blacks very lucrative, which is why hundreds of White men were hired by these states as police officers. Their primary responsibility was to search out and arrest Blacks who were in violation of Black Codes. Once arrested, these men, women and children would be leased to plantations where they would harvest cotton, tobacco, sugar cane. Or they would be leased to work at coal mines, or railroad companies. The owners of these businesses would pay the state for every prisoner who worked for them; prison labor.

It is believed that after the passing of the 13th Amendment, more than 800,000 Blacks were part of the system of peonage, or re-enslavement through the prison system. Peonage didn’t end until after World War II began, around 1940.

This is how it happened.

The 13th Amendment declared that "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction." (Ratified in 1865)

Did you catch that? It says, “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude could occur except as a punishment for a crime". Lawmakers used this phrase to make petty offenses crimes. When Blacks were found guilty of committing these crimes, they were imprisoned and then leased out to the same businesses that lost slaves after the passing of the 13th Amendment. This system of convict labor is called peonage.

The majority of White Southern farmers and business owners hated the 13th Amendment because it took away slave labor. As a way to appease them, the federal government turned a blind eye when southern states used this clause in the 13th Amendment to establish laws called Black Codes. Here are some examples of Black Codes:

In Louisiana, it was illegal for a Black man to preach to Black congregations without special permission in writing from the president of the police. If caught, he could be arrested and fined. If he could not pay the fines, which were unbelievably high, he would be forced to work for an individual, or go to jail or prison where he would work until his debt was paid off.

If a Black person did not have a job, he or she could be arrested and imprisoned on the charge of vagrancy or loitering.

This next Black Code will make you cringe. In South Carolina, if the parent of a Black child was considered vagrant, the judicial system allowed the police and/or other government agencies to “apprentice” the child to an "employer". Males could be held until the age of 21, and females could be held until they were 18. Their owner had the legal right to inflict punishment on the child for disobedience, and to recapture them if they ran away.

This (peonage) is an example of systemic racism - Racism established and perpetuated by government systems. Slavery was made legal by the U.S. Government. Segregation, Black Codes, Jim Crow and peonage were all made legal by the government, and upheld by the judicial system. These acts of racism were built into the system, which is where the term “Systemic Racism” is derived.

This is the part of "Black History" that most of us were never told about.

401 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Abolition forgery":

So, observers and historians have, for a long time, since the first abolition campaigns, talked and written a lot about how Britain and the United States sought to improve their image and optics in the early nineteenth century by endorsing the formal legal abolition of chattel slavery, while the British and US states and their businesses/corporations meanwhile used this legal abolition as a cloak to receive credit for being nice, benevolent liberal democracies while they actually replaced the lost “productivity” of slave laborers by expanding the use of indentured laborers and prison laborers, achieved by passing laws to criminalize poverty, vagabondage, loitering, etc., to capture and imprison laborers. Like, this was explicit; we can read about these plans in the journals and letters of statesmen and politicians from that time. Many "abolitionist" politicians were extremely anxious about how to replace the lost labor. This use of indentured labor and prison labor has been extensively explored in study/discussion fields (discourse on Revolutionary Atlantic, the Black Atlantic, the Caribbean, the American South, prisons, etc.), Basic stuff at this point. Both slavery-based plantation operations and contemporary prisons are concerned with mobility and immobility, how to control and restrict the movement of people, especially Black people. After the “official” abolition of slavery, Europe and the United States then disguised their continued use of forced labor with the language of freedom, liberation, etc. And this isn't merely historical revisionism; critics and observers from that time (during the Haitian Revolution around 1800 or in the 1830s in London, for example) were conscious of how governments were actively trying to replicate this system of servitude..

And recently I came across this term that I liked, from scholar Ndubueze Mbah.

He calls this “abolition forgery.”

Mbah uses this term to describe how Europe and the US disguised ongoing forced labor, how these states “fake” liberation, making a “forgery” of justice.

But Mbah then also uses “abolition forgery” in a dramatically different, ironic counterpoint: to describe how the dispossessed, the poor, found ways to confront the ongoing state violence by forging documents, faking paperwork, piracy, evasion, etc. They find ways to remain mobile, to avoid surveillance.

And this reminds me quite a bit of Sylvia Wynter’s now-famous kinda double-meaning and definition of “plot” when discussing the plantation environment. If you’re unfamiliar:

Wynter uses “plot” to describe the literal plantation plots, where slaves were forced to work in these enclosed industrialized spaces of hyper-efficient agriculture, as in plots of crops, soil, and enclosed private land. However, then Wynter expands the use of the term “plot” to show the agency of the enslaved and imprisoned, by highlighting how the victims of forced labor “plot” against the prison, the plantation overseer, the state. They make subversive “plots” and plan escapes and subterfuge, and in doing so, they build lives for themselves despite the violence. And in this way, they also extend the “plot” of their own stories, their own narratives. So by promoting the plot of their own narratives, in opposition to the “official” narratives and “official” discourses of imperial states which try to determine what counts as “legitimate” and try to define the course of history, people instead create counter-histories, liberated narratives. This allows an “escape”. Not just a literal escape from the physical confines of the plantation or the carceral state, an escape from the walls and the fences, but also an escape from the official narratives endorsed by empires, creating different futures.

(National borders also function in this way, to prevent mobility and therefore compel people to subject themselves to local work environments.)

Katherine McKittrick also expands on Wynter's ideas about plots and plantations, describing how contemporary cities restrict mobility of laborers.

So Mbah seems to be playing in this space with two different definitions of “abolition forgery.”

Mbah authored a paper titled ‘“Where There is Freedom, There Is No State”: Abolition as a Forgery’. He discussed the paper at American Historical Association’s “Mobility and Labor in the Post-Abolition Atlantic World” symposium held on 6 January 2023. Here’s an abstract published online at AHA’s site: This paper outlines the geography and networks of indentured labor recruitment, conditions of plantation and lumbering labor, and property repatriation practices of Nigerian British-subjects inveigled into “unfree” migrant “wage-labor” in Spanish Fernando Po and French Gabon in the first half of the twentieth century. [...] Their agencies and experiences clarify how abolitionism expanded forced labor and unfreedom, and broaden our understanding of global Black unfreedom after the end of trans-Atlantic slavery. Because monopolies and forced labor [...] underpinned European imperialism in post-abolition West Africa, Africans interfaced with colonial states through forgery and illicit mobilities [...] to survive and thrive.

---

Also. Here’s a look at another talk he gave in April 2023.

[Excerpt:]

Ndubueze L. Mbah, an associate professor of history and global gender studies at the University at Buffalo, discussed the theory and implications of “abolition forgery” in a seminar [...]. In the lecture, Mbah — a West African Atlantic historian — defined his core concept of “abolition forgery” as a combination of two interwoven processes. He first discussed the usage of abolition forgery as “the use of free labor discourse to disguise forced labor” in European imperialism in Africa throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Later in the lecture, Mbah provided a counterpoint to this definition of abolition forgery, using the term to describe the ways Africans trapped in a system of forced labor faked documents to promote their mobility across the continent. [...]

Mbah began the webinar by discussing the story of Jampawo, an African British subject who petitioned the British colonial governor in 1900. In his appeal, Jampawo cited the physical punishment he and nine African men endured when they refused to sign a Spanish labor contract that differed significantly from the English language contract they signed at recruitment and constituted terms they deemed to be akin to slavery. Because of the men’s consent in the initial English language contract, however, the governor determined that “they were not victims of forced labor, but willful beneficiaries of free labor,” Mbah said.

Mbah transitioned from this anecdote describing an instance of coerced contract labor to a discussion of different modes of resistance employed by Africans who experienced similar conditions under British imperialism. “Africans like Jampawo resisted by voting with their feet, walking away or running away, or by calling out abolition as a hoax,” Mbah said.

Mbah introduced the concept of African hypermobility, through which “coerced migrants challenged the capacity of colonial borders and contracts to keep them within sites of exploitation,” he said.] [...] Mbah also discussed how the stipulations of forced labor contracts imposed constricting gender hierarchies [...]. To conclude, Mbah gestured toward how the system of forced labor persists in Africa today, yet it “continues to be masked by neoliberal discourses of democracy and of development.” [...] “The so-called greening of Africa [...] continues to rely on forced labor that remains invisible.” [End of excerpt.]

---

This text excerpt from: Emily R. Willrich and Nicole Y. Lu. “Harvard Radcliffe Fellow Discusses Theory of ‘Abolition Forgery’ in Webinar.” The Harvard Crimson. 13 April 2023. [Published online. Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

609 notes

·

View notes

Text

Denazification, truth and reconciliation, and the story of Germany's story

Germany is the “world champion in remembrance,” celebrated for its post-Holocaust policies of ensuring that every German never forgot what had been done in their names, and in holding themselves and future generations accountable for the Nazis’ crimes.

All my life, the Germans have been a counterexample to other nations, where the order of the day was to officially forget the sins that stained the land. “Least said, soonest mended,” was the Canadian and American approach to the genocide of First Nations people and the theft of their land. It was, famously, how America, especially the American south, dealt with the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow.

Silence begets forgetting, which begets revisionism. The founding crimes of our nations receded into the mists of time and acquired a gauzy, romantic veneer. Plantations — slave labor camps where work was obtained through torture, maiming and murder — were recast as the tragiromantic settings of Gone With the Wind. The deliberate extinction of indigenous peoples was revised as the “taming of the New World.” The American Civil War was retold as “The Lost Cause,” fought over states’ rights, not over the right of the ultra-wealthy to terrorize kidnapped Africans and their descendants into working to death.

This wasn’t how they did it in Germany. Nazi symbols and historical revisionism were banned (even the Berlin production of “The Producers” had to be performed without swastikas). The criminals were tried and executed. Every student learned what had been done. Cash reparations were paid — to Jews, and to the people whom the Nazis had conquered and brutalized. Having given in to ghastly barbarism on an terrifyingly industrial scale, the Germans had remade themselves with characteristic efficiency, rooting out the fascist rot and ensuring that it never took hold again.

But Germany’s storied reformation was always oversold. As neo-Nazi movements sprang up and organized political parties — like the far-right Alternative für Deutschland — fielded fascist candidates, they also took to the streets in violent mobs. Worse, top German security officials turned out to be allied with AfD:

https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2018/08/04/germ-a04.html

Neofascists in Germany had fat bankrolls, thanks to generous, secret donations from some of the country’s wealthiest billionaires:

https://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/billionaire-backing-may-have-helped-launch-afd-a-1241029.html

And they broadened their reach by marrying their existing conspiratorial beliefs with Qanon, which made their numbers surge:

https://www.thedailybeast.com/how-fringe-groups-are-using-qanon-to-amplify-their-wild-messages

Today, the far right is surging around Europe, with the rot spreading from Hungary and Poland to Italy and France. In an interview with Jacobin’s David Broder, Tommaso Speccher a researcher based in Berlin, explores the failure of Germany’s storied memory:

https://jacobin.com/2023/07/germany-nazism-holocaust-federal-republic-memory-culture/

Speccher is at pains to remind us that Germany’s truth and reconciliation proceeded in fits and starts, and involved compromises that were seldom discussed, even though they left some of the Reich’s most vicious criminals untouched by any accountability for their crimes, and denied some victims any justice — or even an apology.

You may know that many queer people who were sent to Nazi concentration camps were immediately re-imprisoned after the camps were liberated. Both Nazi Germany and post-Nazi Germany made homosexuality a crime:

https://time.com/5953047/lgbtq-holocaust-stories/

But while there’s been some recent historical grappling with this jaw-dropping injustice, there’s been far less attention given to the plight of the communists, labor organizers, social democrats and other leftists whom the Nazis imprisoned and murdered. These political prisoners (and their survivors) struggled mightily to get the reparations they were due.

Not only was the process punitively complex, but it was administered by bureaucrats who had served in the Reich — the people who had sent them to the camps were in charge of deciding whether they were due compensation.

This is part of a wider pattern. The business-leaders who abetted the Reich through their firms — Siemens, BMW, Hugo Boss, IG Farben, Volkswagon — were largely spared any punishment for their role in the the Holocaust. Many got to keep the riches they acquired through their part on an act of genocide.

Meanwhile, historians grappling with the war through the “Historikerstreit” drew invidious comparisons between communism and fascism, equating the two ideologies and tacitly excusing the torture and killing of political prisoners (this tale is still told today — in America! My kid’s AP history course made this exact point last year).

The refusal to consider that extreme wealth, inequality, and the lust for profits — not blood — provided the Nazis with the budget, materiel and backing they needed to seize control in Germany is of a piece with the decision not to hold Germany’s Nazi-enabling plutocrats to account.

The impunity for business leaders who collaborated with the Nazis on exploiting slave labor is hard to believe. Take IG Farben, a company still doing a merry business today. Farben ran a rubber factory on Auschwitz slave labor, but its executives were frustrated by the delays occasioned by the daily 4.5m forced march from the death-camp to its factory:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/06/02/plunderers/#farben

So Farben built Monowitz, its own, private-sector concentration camp. IG Farben purchased 25,000 slaves from the Reich, among them as many children as possible (the Reich charged less for child slaves).

Even by the standards of Nazi death camps, Monowitz was a charnel house. Monowitz’s inmates were worked to death in just three months. The conditions were so brutal that the SS guards sent official complaints to Berlin. Among their complaints: Farben refused to fund extra hospital beds for the slaves who were beaten so badly they required immediate medical attention.

Farben broke the historical orthodoxy about slavery: until Monowitz, historians widely believed that enslavers would — at the very least — seek to maintain the health of their slaves, simply as a matter of economic efficiency. But the Reich’s rock-bottom rates for fresh slaves liberated Farben from the need to preserve their slaves’ ability to work. Instead, the slaves of Monowitz became disposable, and the bloodless logic of profit maximization dictated that more work could be attained at lower prices by working them to death over twelve short weeks.

Few of us know about Monowitz today, but in the last years of the war, it shocked the world. Joseph Borkin — a US antitrust lawyer who was sent to Germany after the war as part of the legal team overseeing the denazification program — wrote a seminal history of IG Farben, “The Crime and Punishment of I.G. Farben”:

https://www.scribd.com/document/517797736/The-Crime-and-Punishment-of-I-G-Farben

Borkin’s book was a bestseller, which enraged America’s business lobby. The book made the connection between Farben’s commercial strategies and the rise of the Reich (Farben helped manipulate global commodity prices in the runup to the war, which let the Reich fund its war preparations). He argued that big business constituted a danger to democracy and human rights, because its leaders would always sideline both in service to profits.

US companies like Standard Oil and Dow Chemicals poured resources into discrediting the book and smearing Borkin, forcing him into retirement and obscurity in 1945, the same year his publisher withdrew his book from stores.

When we speak of Germany’s denazification effort, it’s as a German program, but of course that’s not right. Denazification was initiated, designed and overseen by the war’s winners — in West Germany, that was the USA.

Those US prosecutors and bureaucrats wanted justice, but not too much of it. For them, denazification had to be balanced against anticommunism, and the imperatives of American business. Nazi war criminals must go on trial — but not if they were rocket scientists, especially not if the USSR might make use of them:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wernher_von_Braun

Recall that in the USA, the bizarre epithet “premature antifascist” was used to condemn Americans who opposed Nazism (and fascism elsewhere in Europe) too soon, because these antifascists opposed the authoritarian politics of big business in America, too:

https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/premature-antifascist-and-proudly-so/

When 24 Farben executives were tried at Nuremberg for the slaughter at Monowitz, then argued that they had no choice but to pursue slave labor — it was their duty to their shareholders. The judges agreed: 19 of those executives walked.

Anticommunism hamstrung denazification. There was no question that German elites and its largest businesses were complicit in Nazi crimes — not mere suppliers, but active collaborators. Antifacism wasn’t formally integrated into the denazification framework until the 1980s with “constitutional patriotism,” which took until the 1990s to take firm root.

The requirement for a denazification program that didn’t condemn capitalism meant that there would always be holes in Germany’s truth and reconciliation process. The newly formed Federal Republic set aside Article 10 of the Nuremberg Charter, which would hold all members of the Nazi Party and SS responsible for their crimes. But Article 10 didn’t survive contact with the Federal Republic: immediately upon taking office, Konrad Adenauer suspended Article 10, sparing 10 million war criminals.

While those spared included many rank-and-file order-followers, it also included many of the Reich’s most notorious criminals. The Nazi judge who sent Erika von Brockdorff to her death for her leftist politics was given a judge’s pension after the war, and lived out his days in a luxurious mansion.

Not every Nazi was pensioned off — many continued to serve in the post-war West German government. Even as Willy Brandt was demonstrating historic remorse for Germany’s crimes, his foreign ministry was riddled with ex-Nazi bureaucrats who’d served in Hitler’s foreign ministry. We still remember Brandt’s brilliant 1973 UN speech on the Holocaust:

https://www.willy-brandt-biography.com/historical-sources/videos/speech-uno-new-york-1973/

But recollections of Brandt’s speech are seldom accompanied by historian Götz Aly’s observation that Brandt couldn’t have given that speech in Germany without serious blowback from the country’s still numerous and emboldened antisemites (Brandt donated his Nobel prize money to restore Venice’s Scuola Grande Tedesca synagogue, but ensured that this was kept secret until after his death).

All this to say that Germany’s reputation as “world champions of memory” is based on acts undertaken decades after the war. Some of Germany’s best-known Holocaust memorials are very recent, like the Wannsee Conference House (1992), the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (2005), and the Topography of Terror Museum in (2010).

Germany’s remembering includes an explicit act of forgetting — forgetting the role Germany’s business leaders and elites played in Hitler’s rise to power and the Nazi crimes that followed. For Speccher, the rise of neofacist movements in Germany can’t be separated from this selective memory, weighed down by anticommunist fervor.

And in East Germany, there was a different kind of incomplete rememberance. While the DDR’s historians and teachings emphasized the role of business in the rise of fascism, they excluded all the elements of Nazism rooted in bigotry: antisemitism, homophobia, sectarianism, and racism. For East German historians, Nazism wasn’t about these, it was solely “the ultimate end point of the history of capitalism.”

Neither is sufficient to prevent authoritarianism and repression, obviously. But the DDR is dust, and the anticommunism-tainted version of denazification is triumphant. Today, Europe’s wealthiest families and largest businesses are funneling vast sums into far-right “populist” parties that trade in antisemitic “Great Replacement” tropes and Holocaust denial:

https://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/Europe%E2%80%99s%20two-faced%20authoritarian%20right%20FINAL_1.pdf

And Germany’s coddled aristocratic families and their wealthy benefactors — whose Nazi ties were quietly forgiven after the war — conspire to overthrow the government and install a far-right autocracy:

https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/25-suspected-members-german-far-right-group-arrested-raids-prosecutors-office-2022-12-07/

In recent years, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about denazification. For all the flaws in Germany’s remembrance, it stands apart as one of the brightest lights in national reckonings with unforgivable crimes. Compare this with, say, Spain, where the remains of fascist dictator Francisco Franco were housed in a hero’s monument, amidst his victims’ bones, until 2019:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pedro_S%C3%A1nchez#Domestic_policy

What do you do with the losers of a just war? “Least said soonest mended” was never a plausible answer, and has been a historical failure — as the fields of fluttering Confederate flags across the American south can attest (to say nothing of the failure of American de-ba’athification in Iraq):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De-Ba%27athification

But on the other hand, people who lose the war aren’t going to dig a hole, climb in and pull the dirt down on top of themselves. Just because I think Germany’s denazification was hobbled by the decision to lets its architects and perpetrators walk free, I don’t know that I would have supported prison for all ten million people captured by Article 10.

And it’s not clear that an explicit antifascism from the start would have patched the holes in German denazification. As Speccher points out, Italy’s postwar constitution was explicitly antifascist, the nation “steeped in institutional anti-fascism.” Postwar Italian governments included prominent resistance fighters who’d fought Mussolini and his brownshirts.

But in the 1990s, “the end of the First Republic” saw constitutional reforms that removed antifascism — reforms that preceded the rise of the corrupt authoritarian Silvio Berlusconi — and there’s a line from him to the neofascists in today’s ruling Italian coalition.

Is there any hope for creating a durable, democratic, anti-authoritarian state out of a world run by the descendants of plunderers and killers? Can any revolution — political, military or technological — hope to reckon with (let alone make peace with!) the people who have brought us to this terrifying juncture?

[Image ID: The Tor Books cover for ‘The Lost Cause,’ designed by Will Staehle, featuring the head of the snake on the Gadsen ‘Don’t Tread on Me’ flag, shedding a tear.]

Like I say, this is something I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about — not just how we might get out of this current mess, but how we’ll stay out of it. As is my wont, I’ve worked out my anxieties on the page. My next novel, The Lost Cause, comes out from Tor Books and Head of Zeus in November:

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250865939/the-lost-cause

Lost Cause is a post-GND utopian novel about a near-future world where the climate emergency is finally being treated with the seriousness and urgency it warrants. It’s a world wracked by fire, flood, scorching heat, mass extinctions and rolling refugee crises — but it’s also a world where we’re doing something about all this. It’s not an optimistic book, but it is a hopeful one. As Kim Stanley Robison says:

This book looks like our future and feels like our present — it’s an unforgettable vision of what could be. Even a partly good future will require wicked political battles and steadfast solidarity among those fighting for a better world, and here I lived it along with Brooks, Ana Lucía, Phuong, and their comrades in the struggle. Along with the rush of adrenaline I felt a solid surge of hope. May it go like this.

The Lost Cause is a hopeful book, but it’s also a worried one. The book is set during a counter-reformation, where an unholy alliance of seagoing anarcho-capitalist wreckers and white nationalist militias are trying to seize power, snatching defeat from the jaws of the fragile climate victory. It’s a book about the need for truth and reconciliation — and its limits.

As Bill McKibben says:

The first great YIMBY novel, this chronicle of mutual aid is politically perceptive, scientifically sound, and extraordinarily hopeful even amidst the smoke. Forget the Silicon Valley bros — these are the California techsters we need rebuilding our world, one solar panel and prefab insulated wall at a time.

We’re currently in the midst of a decidedly unjust war — the war to continue roasting the planet, a war waged in the name of continuing enrichment of the world’s already-obscenely-rich oligarchs. That war requires increasingly authoritarian measures, increasing violence and repression.

I believe we can win this war and secure a habitable planet for all of us — hell, I believe we can build a world of comfort and abundance out of its ashes, far better than this one:

https://tinyletter.com/metafoundry/letters/metafoundry-75-resilience-abundance-decentralization

But even if that world comes to being, there will be millions of people who hate it, a counter-revolution in waiting. These are our friends, our relatives, our neighbors. Figuring out how to make peace with them — and how to hold their most culpable, most powerful leaders to account — is a project that’s as important, and gigantic, and uncertain, as a just transition is.

Next weekend, I’ll be at San Diego Comic-Con:

Thu, Jul 20 16h: Signing, Tor Books booth #2802 (free advance copies of The Lost Cause— Nov 2023 — to the first 50 people!)

Fri, Jul 21 1030h: Wish They All Could be CA MCs, room 24ABC (panel)

Fri, Jul 21 12h: Signing, AA09

Sat, Jul 22 15h: The Worlds We Return To, room 23ABC (panel)

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this thread to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/07/19/stolpersteine/#truth-and-reconciliation

[Image ID: Three 'stumbling stones' ('stolpersteine') set into the sidewalk in the Mitte, in Berlin; they memorialize Jews who lived nearby until they were deported to Auschwitz and murdered.]

#pluralistic#stolpersteine#historians' dispute#Historikerstreit#nazis#godwin's law#mussolini#berlusconi#italy#antifa#fascism#history#truth and reconciliation#the lost cause#denazification

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marcel is a Mikaelson. He does not have to call himself a Mikaelson as he is fully within his rights to denounce the very toxic family but he is one.

I hate the way the show treated him, I hate the way the characters treated him, and I hate that he is involved with Rebekah. I hate the way he and Hope are only kinda sorta siblings.

1. The show:

So we know Julie Plec is very much a white liberal. We know this. We know she has sexism issues, we know she has racism issues (black women will save us all, really Julie????). I don't know which of her multitude of biases made her (and the rest of the writers) think that the way they wrote Marcel and the Mikaelson's relationships with him, was normal (or like normal in the context of the show). But boy howdy.

The plantation house. We're just going to have the Mikaelsons move into the house where Marcel was owned as a slave????? That's what we're gonna do?????? And where his abusive biological father lived and y'know, abused him. Fucking what the fuck?? I feel like this just epitomises the way the show treats Marcel.

2. The characters:

The family never treats him as part of the family unless they want something from him.

They did not raise him as a son and it is weird and terrible and he was a child!!!!! Why did you adopt him if you didn't want a child???

Why is Klaus so scared of having Hope if he's already had a child?

Why does Klaus treat Marcel the exact same way Mikael treated him just because they're not blood related?? (if they actually explored this it could have been interesting but no they just only half treat Marcel as a Mikaelson).

YOU'RE TELLING ME THEY DIDN'T CHECK?? THEY DIDN'T CHECK HE WAS DEAD????? Not once in the 80+ years did Klaus or Elijah go back to New Orleans or even send someone to fucking check that his SON was really dead??? Didn't think to do that???? No???

3. Rebekah:

Oh my god what do I even say about Rebekah?

They could have at least made her be daggered for the time when he was a child and only meet him when he was already an adult and a vampire because that way she's only technically his aunt and not a full fucking adult who saw him grow up!!!!!!!!

Hope:

Idk man, they were siblings. Let them be siblings. The whole thing in Legacies where the Mikaelsons just kind of left Hope alone? Weird. Bonkers. Batshit. I know it's because they couldn't get the actors but maybe think about that before writing your fucking show my guy.

Or in TO where Hope was just left alone and Klaus was not there as a dad for like 5(?) years.

Hayley was the only good parent on The Originals or Legacies canon, fight me.

(side note, you're telling me Caroline would leave Alaric, Alaric, an alcoholic, vampire-hating, weirdo (Caroline and Alaric being romantically involved briefly WAS WEIRD GUYS, WHAT THE ACTUAL FUCK HE USED TO BE HER FUCKING TEACHER) in charge of the school for supernatural children??

You're telling me she left him in charge of parenting Lizzie and Josie?? Yeah okay sure.

And look how well that turned out. Locking teenagers in goddamn prison worlds, excellent headmastering there Alaric well done. And just swell parenting of the twins. Favouring Hope over them at all times and letting them bully each other weirdly for years and allowing your mentally ill children to just get more mentally ill from your parenting. Great moves. Very good.

Okay Legacies rant over)

Yeah okay my whole rant is over I think.

TL;DR: Marcel deserved better.

(and so did the kids on Legacies.)

Also PSA, the only reason I have so many feelings about this is because I like the freaking shows okay? I like the characters (except Alaric and Damon and the ones we're supposed to dislike like Mikael and Esther).

#the originals#legacies#the vampire diaries#TO#tvd#marcel gerard#marcel mikaelson#klaus mikaelson#rebekah mikaelson#hope mikaelson#hayley marshall#hayley mikaelson#alaric saltzman#caroline forbes#lizzie saltzman#josie saltzman#anti-klaus#a bit I guess#anti-alaric#rant#long post

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

@ellakas I'm so glad you asked!

Zachary Taylor is one of those presidents that no one talks about in history class. But the thing is, in the 1840s, everyone was talking about him. He was the war hero of the Mexican-American War. The war itself (a blatant land grab by President Polk) was unpopular, but Taylor emerged as a beloved hero, because was a really good military commander, and because stories emerged about how humanely he treated Mexican prisoners.

Taylor was so popular that both political parties asked him to be their candidate in the next presidential election. He had never held political office. Never shown interest in politics. He had never even voted in a presidential election before! (His reasoning was that, as a military man, he didn't want to serve a commander-in-chief that he had voted against). Yet he was eventually persuaded to run--and win--as the Whig Party candidate.

(Fun fact! His wife, who had no interest in being a politician's wife, prayed that he'd lose the election. Taylor also showed his religious convictions by refusing to be sworn in on a Sunday, so his inauguration was delayed by a day, leaving the US president-less for twenty-four hours).

Even after he was president, Taylor had no interest in playing politics. He wanted to serve the country, not the party. He refused to play political games, purposely not appointing some of the big names of the party to his Cabinet so he could have more diverse voices representing a wider swath of the country. Still in the military mindset of "I give orders and people obey", he was frustrated that he was constantly questioned by Congress, and was very much at odds with them.

The big issue of his presidency was the fact that the US had just gained a ton of land from Mexico, and they had to decide if they'd enter the Union as slave or free states. Since Taylor was a slave-owning Southerner, the Southern Democrats hoped he'd side with them. But Taylor didn't want to expand slavery. First, because it's dumb--it's not like we can grow cotton or sugar in New Mexico or Arizona, so why would we even need plantations? But also because he was coming under the influence of some of the most vocal anti-slavery New York Whigs. To the great anger of the Democrats, Taylor said he wanted California to enter immediately as a free state, and would prefer all the territories to be free states. Before the issue could be resolved, he died. He got violently ill after Fourth of July celebrations in 1850 (because the White House water was still contaminated by human feces), and died five days later, after only a year and a half in office.

A year and a half isn't much time to make an impact. But I'm still fascinated by this president. He was a wonderful mess of contradictions. He was a Southern slave-owner who joined the Northern anti-slavery party. He was against all talk of secession--on the grounds of "I spent forty years serving this country and I want it to stay in one piece"--even though his son-in-law was (I'm not kidding) future president of the Confederacy Jefferson Davis. As a slave-owner and US military leader in the 1800s, he logically can't be a totally good guy, yet I get the sense that he was genuinely trying to be, in the context of his time. And he was showing signs of further character development. If he had lived, who's to say what he could have become, what he could have done?

But we'll never know, because his death left the country in the hands of Millard Fillmore, possibly the most aggressively mediocre man ever to become president (though I have high hopes for Chester Arthur). He actually has a pretty amazing origin story. He was the son of a dirt-poor farmer who apprenticed him to a cloth-maker in what became an indentured servitude situation. He scraped up enough money to buy his freedom and return home. Growing up, the only book he had to read was the Bible, until he turned 17 and bought himself a dictionary. At 20, he started taking adult classes to finally get the education he'd been denied; his teacher was a woman two years older than him who he eventually married. He became a lawyer, and then went into politics, serving in the New York State Legislature. He authored no significant bills. Made no big impact. The main traits people noticed about him were "tall" and "good-looking" (Queen Victoria did later call him the most handsome man she'd ever met). He was just kind of... there.

He was picked as Taylor's vice president for much the same reason Taylor was recruited as presidential candidate--he was moderate enough to appeal to both sides of the polarized political spectrum. New York was the home of the most vocal anti-slavery Whigs, but Fillmore was moderate on the slavery issue. As vice president presiding over the Senate, people mentioned he was "very fair" in how he let both sides speak. And that's like...the best people can say about him.

The question of the slave states eventually produced a bill that came to be known as the Compromise of 1850. Taylor--the enemy of compromise--was against it. Fillmore, a few days before Taylor's death, stated he would support it. After Taylor died, his entire Cabinet resigned rather than serve under a president who supported the Compromise. When the bill passed, Fillmore signed it into law.

The Compromise stated 1) California would enter the union as a free state; 2) the slave trade would end in Washington D.C.; 3) The other territories would decide for themselves if they wanted to allow slaves or not. Most importantly, it put the Fugitive Slave Act into effect, requiring all citizens, even in Northern states, to help return runaway slaves to their owners. The North was outraged over the Fugitive Slave Act; they wanted nothing to do with the practice of slavery and now the government was forcing even free states to support the institution. This law was meant to bring together both sides and prevent war, but it probably had the opposite effect, deepening the divide and hastening the plunge toward armed conflict.

This has led historians to speculate--if the more forceful, principle-driven Taylor had lived, could the path to Civil War at least have been delayed? No way to say, of course; maybe Taylor's solution would have made things worse. But the contrast between these two presidents is so fascinating. In Taylor, you have the apolitical war hero who sticks to his guns--the increasingly anti-slavery slave owner. Meanwhile, Fillmore is a bland politician from the most anti-slavery state who refused to speak against slavery--a man who never really achieved anything because he never really stood for anything. They're such complex characters, full of irony and contradictions, and I'm outraged that my history classes completely skipped over them on the way to Lincoln.

#history is awesome#answered asks#ellakas#my reaction to the taylor episode was outrage i'd never known any of this#the only thing animaniacs taught me about him was he 'liked to smoke his breath killed friends whenever he spoke'#(which is a tidbit the podcast failed to mention)#i feel like there should have been *something* about this guy's ridiculously colorful life worth mentioning#now i'll have to fight the urge to track down my brother again to tell him i forgot to mention the jefferson davis thing#talk about irony!#presidential talk

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

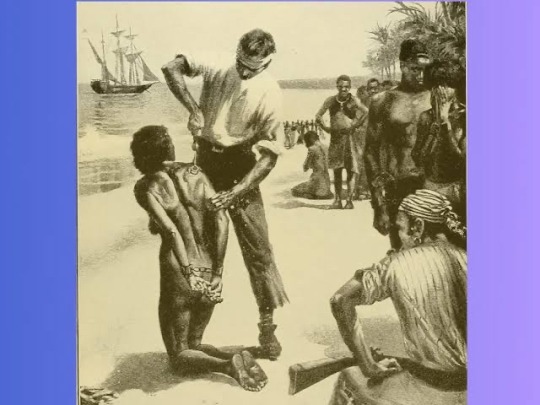

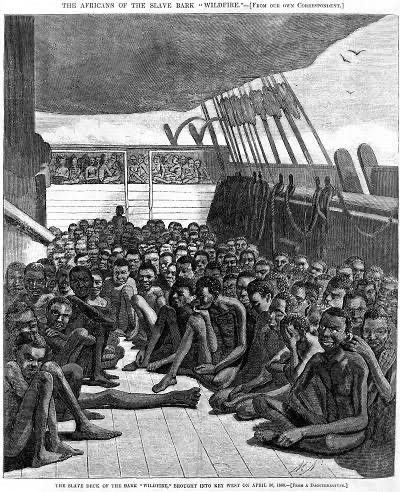

The Harsh Reality of Historical Slave Trade: Africans' Involvement in Selling Their Own

This is a message for my black brothers and sisters

Because of our greed and hatred for our race

We sold ourselves to slavery

The transatlantic slave trade remains one of the darkest chapters in human history, leaving a lasting legacy of suffering, oppression, and discrimination. It is a topic that must be approached with sensitivity and nuance, recognizing the profound impact it had on African communities and the deep scars it has left on the collective conscience of humanity. One aspect that often sparks debate and discomfort is the historical involvement of some Africans in selling their own people to European slave traders. This article aims to shed light on this complex aspect of history while emphasizing the importance of understanding the broader context in which these events occurred.

The Origins of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

The transatlantic slave trade emerged in the 15th century as European powers explored new trade routes and sought to exploit the labor needed to establish and maintain their colonies in the New World. European traders, primarily from Portugal, Spain, England, France, and the Netherlands, sought to acquire laborers from Africa to work on plantations, mines, and other industries in the Americas.

The Role of African Middlemen

It is essential to understand that not all Africans participated in the slave trade, and it is inaccurate to generalize that "blacks sold blacks to the whites." Rather, some African tribes and kingdoms engaged in the business of capturing and selling prisoners of war from rival tribes, criminals, and those deemed outsiders or unwanted in their communities. These captives were then traded to European slave traders for a variety of goods, including textiles, weapons, and other commodities.

It is crucial to acknowledge that the African continent is diverse, comprising numerous ethnic groups, cultures, and societies with varying practices and histories. While some African societies did engage in capturing and trading slaves, others actively resisted the slave trade, viewing it as a deeply harmful and inhumane practice.

Factors Influencing African Participation

Several factors influenced African participation in the slave trade. These include economic incentives, inter-tribal conflicts, and pressure from European powers. The slave trade disrupted existing power dynamics and social structures in Africa, leading to increased conflict and instability in some regions.

Economic motivations were undoubtedly a significant driver. The exchange of slaves for valuable goods provided some African tribes with access to resources they could use to strengthen their position or defend themselves against rival groups. Additionally, some African leaders believed that by trading prisoners of war to European traders, they could avoid becoming victims of the slave trade themselves.

Consequences and Long-Term Impact

The transatlantic slave trade had devastating consequences for African societies. Apart from the immediate loss of human lives and the breakdown of communities caused by forced displacement, the slave trade perpetuated a cycle of violence and disruption that reverberated throughout the continent.

Furthermore, the trade in human beings perpetuated harmful racial stereotypes and discriminatory practices that continue to affect people of African descent to this day. It is essential to recognize the historical roots of racism and the systemic inequalities that have persisted over centuries as a result of the slave trade and colonialism.

Conclusion

The historical involvement of some Africans in the transatlantic slave trade is a deeply troubling and complex aspect of human history. However, it is crucial to avoid oversimplification and instead seek a nuanced understanding of the broader historical context in which these events occurred.

Acknowledging this painful part of history allows us to confront the legacy of slavery and its impact on contemporary society. By understanding the full scope of the transatlantic slave trade, we can work towards building a more just and equitable future, one that respects the dignity and humanity of all individuals, regardless of their race or ethnicity.

#life#animals#culture#aesthetic#black history#history#blm blacklivesmatter#anime and manga#architecture

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

A hidden path to America’s dinner tables begins here, at an unlikely source – a former Southern slave plantation that is now the country’s largest maximum-security prison.

Unmarked trucks packed with prison-raised cattle roll out of the Louisiana State Penitentiary, where men are sentenced to hard labor and forced to work, for pennies an hour or sometimes nothing at all. After rumbling down a country road to an auction house, the cows are bought by a local rancher and then followed by The Associated Press another 600 miles to a Texas slaughterhouse that feeds into the supply chains of giants like McDonald’s, Walmart and Cargill.

Intricate, invisible webs, just like this one, link some of the world’s largest food companies and most popular brands to jobs performed by U.S. prisoners nationwide, according to a sweeping two-year AP investigation into prison labor that tied hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of agricultural products to goods sold on the open market.

They are among America’s most vulnerable laborers. If they refuse to work, some can jeopardize their chances of parole or face punishment like being sent to solitary confinement. They also are often excluded from protections guaranteed to almost all other full-time workers, even when they are seriously injured or killed on the job.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Posted on June 17, 2021 by Anonymous FW

The Industrial Workers of the World is one of the few unions that has always understood the importance of organizing Black workers to prevent capitalist abuse of all workers, vowing in its earliest days to never charter a segregated Branch or Local. The IWW has long fought to organize Black labor against being used as expendable and underpaid scabs, as well as for the abolition of all impediments to Black liberation.

Black liberation is the struggle for freedom and equality for Black people; a continuous fight against the attitudes and institutions that dehumanize Black people in order to propagate and maintain white supremacy. The Black Liberation Movement is most often associated with the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, but has actually existed for hundreds of years. Its history spans from the slave revolts on the shores of West Africa from where we were stolen to the protests still taking place today. A key focus of this current phase of the movement is the need to liberate Black people from the dual oppression of police and of capitalism, just as the IWW seeks to liberate the entire working class from those very same clutches.

Whenever I am asked about the history of unions and the labor movement and how they intersect with Black history, I’m always sure to talk about the Industrial Workers of the World. From Lucy Parsons, a Black woman and founding member of the Union, to Maritime Worker Ben Fletcher’s efforts to establish one of the most diverse institutions of its time, Black Wobblies shaped the IWW and its commitment to the struggle for Black liberation from the very beginning. Additionally, I emphasize this Union’s dedication to organizing workers of color over 100 years ago when Samuel Gompers’ American Federation of Labor would, at best, organize segregated unions if they engaged with Black labor at all.

One event I typically recount occurred in May 1912 in Alexandria, Louisiana, as William D. “Big Bill” Haywood stood before the Brotherhood of Timber Workers. The Brotherhood was a national union of lumberjacks and millworkers with members in Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana, which had a large population of both Black and white workers. The organization had been ignored by other unions and chose to affiliate with the IWW instead. Haywood was puzzled as he looked out at the entirely white audience of timber workers, and he inquired why there were no Black workers at the meeting. In 1912, racially desegregated meetings were illegal everywhere in the state of Louisiana, and Haywood was informed that the rest of the workers were meeting elsewhere.

“You work in the same mills together. Sometimes a Black man and a white man may chop down the same tree together […] This can’t be done intelligently by passing resolutions here and then sending them out to another room for the Black men to act upon. Why not be sensible about this and call the Negroes into this convention?” Haywood continued: “If it is against the law, this is one time when the law should be broken.” Following this, the Black timbermen joined the suddenly desegregated meeting and, in the election of delegates, both Black and white members were elected to represent the Brotherhood of Timber Workers at their 1912 convention.

The IWW’s present-day commitment to Black liberation is perhaps best evidenced by the recent work of the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC). This rank-and-file union of the IWW seeks to abolish prison slavery and improve conditions within prisons, jails, and detention centers through direct action. Prison slavery is one of the most perverse systems of worker exploitation and white supremacy in this nation today. Many incarcerated workers find themselves working on plantations and roadcrews, and engaging in all manner of work tasks necessary for the prison to operate. These workers also manufacture products and provide services for private corporations, thereby generating their captor’s wealth while receiving mere pennies per hour for their labor if they are even compensated at all.

Furthermore, these incarcerated comrades are subjected to unsafe and inhumane living conditions. The prison-industrial complex is a system that affects all working class people but disproportionately targets and exploits Black people. In order to fight this system, IWOC has participated in organizing several actions including the 2016 and 2018 U.S. prison strikes. These demonstrations, such as work stoppages and hunger strikes organized in solidarity with incarcerated workers at many prisons across the United States in an attempt to win specific demands and recognitions that included improvements to prison conditions, paying incarcerated workers prevailing wage for their labor, and bring an immediate end to racially biased judicial overreach, such as overcharging, over-sentencing, and baseless denials of parole for Black and Brown people.

The IWW has several chartered IWOC branches and continues to provide support through initiatives such as the case reader program where IWW members assist in getting cases overturned and prisoners released. Building committees among the currently and formerly incarcerated workers in the struggle brings awareness to the public about conditions these workers face and provides resources for them to advocate for themselves through direct action within the system that enslaves them. The IWW’s fight for prison abolition is just one example of our One Big Union’s continued commitment to the liberation of Black people in North America and around the world.

The Industrial Workers of the World has always been and continues to be the most important union when it comes to the struggle for Black liberation in the workplace. I encourage every Wobbly to learn and understand what is meant by –and necessary for– true Black liberation, for without this understanding, it will be impossible to liberate all working people from the repression and subjugation of race and class. And to all Black workers who are not yet Wobblies, I call on you to join the One Big Union. It is the only union that has been consistently fighting alongside Black labor for the liberation of our people since the beginning of the 20th century.

.

Fellow Worker Alki, an at-large member affiliated with IU660, describes himself as a Black Anarchist Wobbly, as well as an essayist, historian, and media creator focused on organized labor and other radical movements from an historical perspective.

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

The stories of Beenadick Thundersnatch paying reparations for slavery in Barbados especially because his family was heavily compensated for losing their slaves when slavery was abolished in 1834 is fun and all. (Though inaccurate)

But need I remind you slavery was abolished in America in 1865 and American slave owners were also compensated for their slaves being freed?

Not to mention the freed slaves were promised reparations in the form of land, which never came.

And the lack of resources forces recently freed slaves to continue to work the plantations they were on.

Not to mention Neo-Slavery. Which is a mix of "freed" slaves being put into camps which are essentially the same houses that they were kept in as slaves because the union soldiers didn't know what to do with all of these recently freed people that had no education, no money, no way to care for themselves, etc.

And anti-vagrancy laws that allowed them to be arrested and forced back into slavery because the 13th amendment says "unless punishment for a crime".

Black people continued being kept as slaves as late as 1963 in rural areas because no one caught it and the slaves were so uneducated that they couldn't read whatever knews was sent that they were free.

(Legit. Imagine fighting for desegregation completely unwitting to the fact that slavery was still happening.)

And modern day slavery in the US prison system using that 13th amendment loophole I mentioned earlier.

So maybe instead of applauding at attempts to force Beenadick Slaverbatch to pay reparations. Maybe we should work on ending slavery in the states and working on reparations here, yes?

-fae

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“The history of the transatlantic slave trade and chattel slavery looms large in contemporary trafficking conversations – often in the form of claims, subtle or not, that modern trafficking is worse than chattel slavery. Politicians and police officers meet to tell each other that ‘there are more slaves now than at any previous point in human history’; a UK former government minister insists that ‘we are facing a new slave trade, whose victims are tortured, terrified East European girls rather than Africans’. Matteo Renzi, then prime minister of Italy, wrote in 2015 that ‘human traffickers are the slave traders of the twenty-first century’. The Vatican claimed that ‘modern slavery’, specifically prostitution, is ‘worse than the slavery of those … who were taken from Africa’. A senior British police officer remarked that ‘the cotton plantations and sugar plantations of the eighteenth and nineteenth century … wouldn’t be as bad as what some victims [today] go through’.

A 2012 anti-trafficking ‘documentary’ that was screened for politicians and policymakers around the world, including in Washington, London, Edinburgh, and at the UN buildings in New York, proclaims: ‘In 1809 the cost of a slave was thirty thousand dollars. In 2009, the cost of a slave is ninety dollars.’ White people co-opting the history of chattel slavery as rhetoric is grim, not least because the term slavery names a specific legal institution created, enforced and protected by the state, which is nowhere near synonymous with contemporary ideas of trafficking. Indeed, the direct modern descendant of chattel slavery in the US is not prostitution but the prison system. Slavery was not abolished but explicitly retained in the US Constitution as punishment for crime in the Thirteenth Amendment of the Bill of Rights, which states that ‘neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction’ (emphasis ours).

The Thirteenth Amendment isn’t just a vestigial hangover. In 2016, the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee released a statement condemning inmates’ treatment in the prison work system:

Overseers watch over our every move, and if we do not perform our appointed tasks to their liking, we are punished. They may have replaced the whip with pepper spray, but many of the other torments remain: isolation, restraint positions, stripping off our clothes and investigating our bodies as though we are animals.

There are more Black men in the US prison system now than were enslaved in 1850. Seeking to ‘end slavery’ through increased policing and incarceration is a bitterly ironic proposition.

White people in Britain and North America have been very successful at ducking any real reckoning with the legacies of the slave trade. Historian Nick Draper writes, ‘We privilege abolition … If you say to somebody ‘tell me about Britain and slavery’, the instinctive response of most people is Wilberforce and abolition. Those 200 years of slavery beforehand have been elided – we just haven’t wanted to think about it.’ By rhetorically intertwining modern trafficking with chattel slavery, governments and campaigners have been able to hide punitive policies targeting irregular migration behind seemingly uncomplicated righteous outrage.

Men of colour become ‘modern enslavers’ who deserve prosecution or worse. Their ‘human cargo’, figured as being transported against their will, are owed nothing more than ‘humanitarian return’, and the racist trope of border invasion is given a progressive sheen through collective shared horror at the villainy of the perpetrators. Meanwhile, in crackdowns and deportations, European governments position themselves as re-enacting and re-writing the history of anti-slavery movements to make themselves both victims and heroes. Of course, these actions by European governments do harm. For example, their policy of confiscating or destroying smuggling boats has not ‘rescued’ anyone, only induced smugglers to send migrants in less valuable – and less seaworthy – boats, leading to many more deaths. This policy continued for years, despite clear evidence that it was causing deaths. But, faced with twenty-first century ‘enslavers’, there is little need for white reflection. Instead, Renzi later wrote that European nations ‘need to free ourselves from a sense of guilt’ and reject any notion of a ‘moral duty’ to welcome arrivals. At the time of writing, the Italian government’s ‘solution’ to the migrant crisis is to pay for migrants to be incarcerated, stranded in dangerous, disease-ridden detention centres in Libya. As Robyn Maynard writes,

By hijacking the terminology of slavery, even widely referring to themselves as ‘abolitionists’, anti–sex work campaigners … in pushing for criminalization … are often undermining those most harmed by the legacy of slavery. As Black persons across the Americas are literally fighting for our lives, it is urgent to examine the actions and goals of any mostly white and conservative movement who [claim] to be the rightful inheritors of an ‘anti-slavery’ mission which aims to abolish prostitution but both ignores and indirectly facilitates brutalities waged against Black communities.

What does the fight to save people from ‘modern slavery’ look like on the ground? In 2017, police in North Yorkshire told journalists that they were fighting to rescue ‘sex slaves’ and asked members of the public to call in with tips, adding that the ‘sex slaves’ themselves ‘are prepared to do it [sell sex], they believe there is nothing wrong in it … We have just got to … educate them that they are victims of human trafficking.’ It seems fairly obvious that women who are ‘prepared to do it’ and ‘believe there is nothing wrong with it’ will not particularly benefit from being ‘educated’ about the fact that they are victims of trafficking – which in England and Wales means a forty-five-day ‘respite period’ (frequently disregarded) followed by a ‘humanitarian’ deportation.”]

molly smith, juno mac, from revolting prostitutes: the fight for sex workers’ rights, 2018

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Capitalism and Confederate Gold, or: I Develop Brainworms about One Specific Line in the Showdown Scene of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly.

There's one line in the showdown scene that has confused me for awhile.

"200,000 dollars is a lot of money. We're gonna have to earn it."

What is he talking about!!!

"We," he says, as he forces them into an uneven three-way standoff, already knowing that he's going to psyche out Angel Eyes by splitting his focus two ways and then take half the money and tie up Tuco until he's out of reach.

Moreover it seems weird to me because out of nowhere this extremely good old-fashioned American hard-working capitalist sentiment comes out, that they'll have to earn this money. When in fact they are three random dudes swooping in like pirates to snatch up some unattended money that none of them actually earned. 200,000 would be a large sum of money even by today's standards! Adjusting for inflation, this is a near-inconcievable fortune. This was (confederate) government money. Very few civilians would have had anywhere near this much money: the 1%ers at the time, similar to today, were not people who had somehow earned all of that money by themselves; they were factory owners whose earnings were generated by hosts of poor factory workers, plantation owners with slaves working their fields. Powerful men who owned land or businesses worked by others. This isn't the kind of money one guy just ends up with, without exploiting a huge amount of power.

The oddest thing about this to me is that if any one single man out of the trio could be said to have "earned" that money, it would be Angel Eyes. Whereas Blondie and Tuco stumbled accidentally into the quest for the gold and managed to keep an advantage through desperate ad-libbing, grit, and firepower, Angel Eyes did research. He worked at this long term. He found out about the gold through his job (which already had him a "small business owner," if you will; ie the leader of a gang who did a bulk of his dirty work for him) and quickly discovered all the information about it which he could, eliminated his competition for it and went on the hunt. Angel Eyes did detective work! He looked up the half-soldier for information, he found Jackson's old lover and beat her up on the worst day of her life for information, when nothing else worked he got a position in a prison camp where he'd be around large numbers of confederate soldiers and had, statistically, a better chance than anywhere else of finding Jackson or any more information about the gold. And then he set up a racket of beating up and interrogating soldiers and stealing their valuables to keep making money in the meantime! A real entrepreneur if you will, where Blondie was just a scammer.

Blondie and Tuco's entire adventure was one lucky break after another. It was pure chance, perhaps influenced by something supernatural (see "carriage of the spirits,") that brought them into the story at all. But by the time Angel Eyes found them in the camp, he'd put in a lot of work by himself tracking down leads about the gold. Tuco and Blondie showing up right on his doorstep was his first lucky break: everything else he'd done himself. And, being Angel Eyes, he was in a very good position to take advantage of his luck. He'd prepared for this, he was used to secretly moving around prisoners, he had his gang nearby ready to go.

When Blondie says they'll have to earn the money I almost see it as a subtle mockery of Angel Eyes. That Angel Eyes doesn't deserve the money because he's a bad person. Maybe he "earned" it by the rules of the game, but a man who plays like that doesn't "deserve" nice things, even if that's just how the world works. And Blondie, a man just as ruthless and cunning, enough to stand up to him as his equal, is going to take it away from him.

"We're gonna have to earn it," says Blondie about an unthinkably huge sum of money which could not under normal circumstances have been earned by one man, mocking the man who came closest to "earning" it, and whom Blondie already knows he is going to cheat. (Angel Eye's "How?" is pretty funny with this interpretation.)

Now, maybe I'm overthinking this and Blondie considers that he's earned the money by being smarter than Angel Eyes and tough enough not to die in the desert. Maybe the ending is meant to be a fairy story about how, just this one time, the lesser evil ended up with the money instead of the worse guy; the winner actually was someone who, morally, "deserved" it more. Maybe it's literally not that deep: Blondie is starting his mind games that will give him a psychological advantage in the upcoming standoff. He wants them confused. What the fuck is he talking about? Why "we?" Is he cooperating? Is he not? Is he going to shoot me? wtf is he talking about? He doesn't know either and he doesn't want you to know!

I don't think any of this is necessarily an intended reading, just something that's been bouncing around in my head and needs out. Anyone else have thoughts?

#is this profound? is the autism making me fixate too much on things that are not meant to be taken that literally? I can't tell!#long post#the good the bad and the ugly#personal (ok to rb)#meta ?

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Click here to listen to a podcast of this highlight.

The feed is located here if you would like to subscribe.

The Slave Experience of the Holidays

American slaves experienced the Christmas holidays in many different ways. Joy, hope, and celebration were naturally a part of the season for many. For other slaves, these holidays conjured up visions of freedom and even the opportunity to bring about that freedom. Still others saw it as yet another burden to be endured. This month, Documenting the American South considers the Christmas holidays as they were experienced by enslaved Americans.

The prosperity and relaxed discipline associated with Christmas often enabled slaves to interact in ways that they could not during the rest of the year. They customarily received material goods from their masters: perhaps the slave's yearly allotment of clothing, an edible delicacy, or a present above and beyond what he or she needed to survive and work on the plantation. For this reason, among others, slaves frequently married during the Christmas season. When Dice, a female slave in Nina Hill Robinson's Aunt Dice, came to her master "one Christmas eve, and asked his consent to her marriage with Caesar," her master allowed the ceremony, and a "great feast was spread" (pp. 24-25). Dice and Caesar were married in "the mistress's own parlor . . . before the white minister" (pp. 25-26). More than any other time of year, Christmas provided slaves with the latitude and prosperity that made a formal wedding possible.

On the plantation, the transfer of Christmas gifts from master to slave was often accompanied by a curious ritual. On Christmas day, "it was always customary in those days to catch peoples Christmas gifts and they would give you something." Slaves and children would lie in wait for those with the means to provide presents and capture them, crying 'Christmas gift' and refusing to release their prisoners until they received a gift in return (p. 22). This ironic annual inversion of power occasionally allowed slaves to acquire real power. Henry, a slave whose tragic life and death is recounted in Martha Griffith Browne's Autobiography of a Female Slave, saved "Christmas gifts in money" to buy his freedom (p. 311).

Some slaves saw Christmas as an opportunity to escape. They took advantage of relaxed work schedules and the holiday travels of slaveholders, who were too far away to stop them. While some slaveholders presumably treated the holiday as any other workday, numerous authors record a variety of holiday traditions, including the suspension of work for celebration and family visits. Because many slaves had spouses, children, and family who were owned by different masters and who lived on other properties, slaves often requested passes to travel and visit family during this time. Some slaves used the passes to explain their presence on the road and delay the discovery of their escape through their masters' expectation that they would soon return from their "family visit." Jermain Loguen plotted a Christmas escape, stockpiling supplies and waiting for travel passes, knowing the cover of the holidays was essential for success: "Lord speed the day!--freedom begins with the holidays!" (p. 262). These plans turned out to be wise, as Loguen and his companions are almost caught crossing a river into Ohio, but were left alone because the white men thought they were free men "who have been to Kentucky to spend the Holidays with their friends" (p. 303).

Harriet Tubman helped her brothers escape at Christmas. Their master intended to sell them after Christmas but was delayed by the holiday. The brothers were expected to spend the day with their elderly mother but met Tubman in secret. She helped them travel north, gaining a head start on the master who did not discover their disappearance until the end of the holidays. Likewise, William and Ellen Crafts escaped together at Christmastime. They took advantage of passes that were clearly meant for temporary use. Ellen "obtained a pass from her mistress, allowing her to be away for a few days. The cabinet-maker with whom I worked gave me a similar paper, but said that he needed my services very much, and wished me to return as soon as the time granted was up. I thanked him kindly; but somehow I have not been able to make it convenient to return yet; and, as the free air of good old England agrees so well with my wife and our dear little ones, as well as with myself, it is not at all likely we shall return at present to the 'peculiar institution' of chains and stripes" (pp. 303-304).

Christmas could represent not only physical freedom, but spiritual freedom, as well as the hope for better things to come. The main protagonist of Martha Griffin Browne's Autobiography of a Female Slave, Ann, found little positive value in the slaveholder's version of Christmas—equating it with "all sorts of culinary preparations" and extensive house cleaning rituals—but she saw the possibility for a better future in the story of the life of Christ: "This same Jesus, whom the civilized world now worship as their Lord, was once lowly, outcast, and despised; born of the most hated people of the world . . . laid in the manger of a stable at Bethlehem . . . this Jesus is worshipped now" (p. 203, 47-48). For Ann, Christmas symbolized the birth of the very hope she used to survive her captivity.

Not all enslaved African Americans viewed the holidays as a time of celebration and hope. Rather, Christmas served only to highlight their lack of freedom. As a young boy, Louis Hughes was bought in December and introduced to his new household on Christmas Eve "as a Christmas gift to the madam" (p. 13). When Peter Bruner tried to claim a Christmas gift from his master, "he took me and threw me in the tan vat and nearly drowned me. Every time I made an attempt to get out he would kick me back in again until I was almost dead" (p. 22).