#which i had found fascinating narratively but also kind of paradoxical

Text

okay so i've been thinking about ralsei lately and i have a new theory on what he is and what his role is and his relationship with kris! for all i know somebody has already said this but idk i just wanted to put this out there. thank you if you read through this whole spiel, as it's rather long...!

so what i'm proposing that ralsei is kind of like... a coping mechanism for kris? in that that he's designed to be there for kris and comfort them and make them happy - he's all of the soft, warm, cozy things that can make a bad day better. what's debatable is whether kris wants ralsei as that kind of coping mechanism... maybe they don't want to be told everything will be sunshine and rainbows...

ralsei is very much a people-pleaser; he's unoffensive and soft and trusting. he's always there for you if you want a cake, or a hug, or whatever; he seems to have endless motivation to help and to heal (why, he has healing powers!), especially in terms of kris. in fact, ralsei seems to have a special connection to kris, always wanting to be around them and make them happy. he clearly wants to be there for kris and to comfort them, even if that means ignoring some of the actual terrible stuff happening around them.

this whole notion is bolstered by ralsei's dialogue after the spamton fight in chapter 2, in which he says to kris that it was nothing, and that they shouldn't worry, and that they instead should think of something they like - something warm and soft etc. he's clearly insinuating that he is the thing kris should think of to get their mind off of the spamton fight - which confirms that a) his role is to be a coping mechanism for kris and that b) he wants kris to utilize him as that coping mechanism. he's kind of subtly forcing himself into that position by saying this, by saying that he's something kris likes.

now i should take a step back and talk about kris in relation to ralsei. kris is dealing with the existential horrors of being controlled by some higher being, the soul; to cope with that, they often rip out the soul in their chest and brandish a knife, which they thrust into the ground to make another doorway into the dark world. this is what kris has been using as their coping mechanism. it's violent and seemingly harmful, but it's also incredibly cathartic.

ralsei is the opposite kind of coping mechanism - he doesn't let you hate people or things, he doesn't let you think about the bad stuff that's happened to you (even if it's really horrible messed up bad stuff that needs addressing), and he certainly doesn't let you have anger, nevermind release it. he's the opposite of catharsis; he's pacification.

he wants kris to accept him; he's been waiting in a corner of their mind, ready with cakes and hugs and nostalgic photographs to soothe kris's aching heart. he wants kris to be happy; to him that means kris has to be his friend, kris has to hug him, love him, eat his cakes, be his chosen one and close the fountains caused by their desire for catharsis.

after all, the soul is what's glowing when kris is about to close a fountain; kris only closed it because of us, and we only made them close it because of ralsei. and ralsei told us that hating people and feeling angry is wrong. the fountains represent everything ralsei is against, and so he has us close them.

kris probably doesn't like ralsei as much as we think; i don't think kris hates him, but their reaction to the ralsei tea (as well as their inherent conflicts of interest mentioned above) shows that they certainly have some gripes with the guy.

i think between chapters 1 and 2 things start getting really messy, if they weren't messy already - in chapter 1, as the soul, we couldn't actually make kris kill anyone. in this sense we were narratively doing exactly what ralsei wanted - which in this case is good, as, y'know, that meant we were abstaining from literal murder. in chapter 2, however, we can most certainly kill people, via noelle - notably when ralsei is absent. as the soul we can do whatever we want; ralsei has just been trying to guide us into guiding kris into making the right decision (which ultimately involves closing the fountains - and of course, no matter our opinion in this coping mechanism discourse, we'd want to close the fountains, as then we can progress and play more of the game; we are the player, after all). how much we do follow or diverge from ralsei's advice and how much we should will certainly fluctuate as the chapters progress.

and no, ralsei certainly isn't malicious, and definitely has had a positive impact in many ways; for one thing, he wants the best for kris, and for another, he has actively prevented kris (read: the player) and susie from killing innocent darkners. he's right in thinking that murder is wrong and that you should try to see the best in people; he just overdoes the whole "sunshine and rainbows" spiel because he's naïve. kris and susie are literally the first people he's ever interacted with. ralsei is just naïve. knowing about the player - and by extension knowing any piece of information he really shouldn't - doesn't mean he knows everything or is knowingly witholding information from us/kris. and that certainly doesn't mean he's socially/emotionaly mature.

i don't know if this theory makes complete sense (there are likely certain details i've forgotten or misremembered), but at least to me it explains a lot - for one thing, why ralsei looks so much like asriel, something that has bugged us all since day one: it's because he thinks that's something kris would find comfort in.

okey dokey, so there you go! i hope you like my theory, and thank you for reading! have a lovely day :)

tl;dr - ralsei is a slightly unhealthy coping mechanism <3

#melonposting#long post#deltarune#deltarune chapter 2#deltarune ralsei#ralsei#deltarune kris#kris#kin#y'know i had seen the theory at some point that ralsei's lightner object counterpart is the knife kris uses#which i had found fascinating narratively but also kind of paradoxical#as his appearance and personality are practically the antithesis of a knife#so i suppose in this theory yeah... ralsei really is the antithesis of that knife huh#anyway <3 coping mechanism ralsei my beloved#i hope you like him and not hate him please trust me i do not want any of you to look at this and say 'hm i guess ralsei sucks'#he is just naïve </3 rest in peace to every naïve person ever signed ralsei deltarune#deltarune theory#deltarune headcanon

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 528

On games I've been playing...

Crime O’Clock is a hidden object game where you’re playing as a time detective, your job is to prevent paradoxes that could collapse the timeline or change it from the “True Timeline”. The game visually speaking has a cartoony art style like Hidden Through Time and Windpeaks, but uses the black and white with splashes of colour to highlight things found like cat hidden object games.

It also has a storyline and minigames, making it more similar to the narrative hidden object games like Mystery Case Files. Especially because that storyline was very well written.

But what makes this hidden object game unique, is that time travel isn’t just a story plot, it is a game mechanic. The way the levels are designed is that it is a single huge hidden object scene that the player can zoom in and move around in. However, this scene has 10 points (ticks) in the game where time moves. Every ‘tick’ is a different moment in time, and as the story progresses you are moved forwards and backwards in order to track down suspects or figure out what has happened. This makes the scenes come to live, as every single person in that scene will move and go about their life.

And honestly, this is probably the strongest quality of Crime O’Clock, because the artist(s) involved made these scenes burst with life. It is fascinating to see all the little things these people do that make you want to follow them. Even if their stories aren’t important to the main storyline, and will never even be followed in the Fulcrum Stories side quest.

By the way, fun side note, whoever makes up the Bad Seed studio are all clearly pop culture enthusiasts. All of these scenes are brimming with characters inspired from all sorts of shows, comics, and manga. It was a delight to see references to things like John Wick, Naruto, One Piece, Rick and Morty, and so much more. I played through some of the Fulcrum Stories just so I could follow these people to find out how they fit into this world.

I quite enjoyed Crime O’Clock, the story was well written in a way that I felt the stakes involved. It was a story I wanted to follow, which is always good when you have a narrative based hidden object game. However, I will admit the game may have outstayed its welcome.

While the game had hints for the primary quests, at certain points of the game where tensions are high you get no hints at all. This can be frustrating when you just want to move on with the story, and can’t find what you’re looking for. I actually had to use walkthrough guides because I was getting really stuck, and kind of over the game to a certain degree. I still wanted to know how it ended but I sort of had enough.

This might be more due to the fact I’m not used to hidden object games being this long. I hadn’t even completed all the Fulcrum Stories and I had already played for 19 hours. I’m not the fastest or best person at hidden object games, and I also was taking notes so I wouldn’t forget shit, so your times may vary, but most hidden object games I’ve played are like 3 hours long. So this had taken longer than I wanted.

I still liked it, and it’s still on my computer because I would like to do the side quests at some point. It's very different from what I’m used to, but I do recommend it.

#hidden object games#hidden object#crime o'clock#indie game#indie games#hide and find game#hidden object game

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey, if you don't mind, i want your advice: i'm going to be running a chronicle set in chicago (i am using the chicago by night 5e book) for players who are new to vampire for the most part in a few days and i can't For The Life of Me to come up with an interesting chronicle hook (yeah i have read the hooks in the book). any ideas/suggestions/general advice?

Hiya! I could talk your ears off on how I write my chronicles- so hopefully I have taken all my processes and reduced it down to a lovely World of Darkness jam.

Here are two good hooks I just came up with- feel free to use them! The third is what I got for my first chronicle, and I just think its a narrative that works very well for new players.

>Option 1: Guilty Until Proven Innocent

”Chicago is a series of paradoxes and transitions, of ever changing paradigms and whimsy,” (CbN 47). Have your coterie be newbies to the city. Ask why they have come to Chicago. Power? A new start? Perhaps this is a political arrangement between the clan of one city with another. Whatever their reason, they have arrived right when a Primogen vanishes- and guess who is first on the suspect list? The fresh faces on the streets >:) The coterie, having barely settled, has to suddenly prove their innocence. And finding evidence lets them uncover something much more sinister....

This one is ideal for new players as it sets everyone on an equal footing. Even if they create a character that has been a vampire for 50+ years and has amassed several dots of influence, herd, status- whatever, they are still new to the city. And being new means you have to start all over again. (This may be frustrating to a player that invested all those points at character creation- but it is on you as the ST to make sure they have opportunities to use those dots and on them as a player to think cleverly.)

Starting the tale off with defending their innocence is actually a very engaging questline. It effectively sets the stage for the political powerhouses. It lets new players know there are rules- and those in power are watching. It also sets the consequences for failure. Understand that the Camarilla probably isnt going to outright kill the coterie if they fail- always make the punishment just harsh and grueling enough to make final death feel like a mercy. Failure isn’t the end of the story.

For new players- I would be lenient with the time it takes for them to find evidence. But within reason. Think like your Prince and Seneschal. Do you really want this coterie running around for a full week, unsupervised, making more messes? No. You don’t. (You might wanna send an npc with them to watch and keep em out of trouble. Your npc is also able to vouch for them.)

This story lends itself to be a Camarilla Chronicle very easily. You can go Anarch, but an Anarch leader suddenly vanishing and blaming the newbies is much more quickly going to end with blood spilled. Thank your local sweeper.

> Option 2: Containment Breach

Blacksite 24 (Loresheet on page 264) was temporarily occupied by Operation Firstlight. It has now been transformed into a medical research facility. While most kindred of Chicago know of Blacksite 24, they have zero clue what happens inside other than bad news for them- the less they know the safer they are. The chronicle opens with a car crash. The captured soon-to-be coterie was in transit to this feared medical facility. The crash did kill the driver and the agent in charge of transporting them. The crash did not fully break their restraints, but it did enough damage that first responders are freaking out. They are all at hunger 3. The chronicle is a hunt. The coterie should have some knowledge of what had happened to them and how lucky they are to have escaped. Operatives are already on their way to recapture them. They must hide in this city- and do their best to survive and stay out of sight.

The point of this story is to invoke dread. I highly recommend one player either being a thin-blood (or an npc) with the Daydrinker merit, or a player to have a ghoul. If they decide to not have a daywatch, they increase their chance of being found.

This story also sets up a feeling of desperation. They would be willing to take shelter from anyone- anyone. Eventually the other kindred will catch on that these guys are on the run from something. Any sane kindred would toss them out to protect themselves. A compassionate kindred who takes them in will suffer the final death as a compassionate fool- or join them in captivity.

This story lends itself to be an Anarch Chronicle much more easily. This is the time the Camarilla will likely be a bit more paranoid and bloody. While they might not outright kill the coterie- they will send them somewhere that is a death trap. They wont dirty their hands with this. After all, you do not want any evidence to fall into the hands of the SI if you hired the hit.

This story is ideal for newbies without background merits. No allies, no influence, no herd. Let them take more mythic merits such as bloodhound and unbondable (Consider finding some from V20 too! There are some really awesome supernatural merits!). These powers would certainly be more fascinating for a medical team to study- not how many instagram followers they have. This kind of story also lets your players feel more powerful- but out of the loop. It lends itself to them forging alliances and getting caught in one-sided favors a lot more quickly.

The challenging aspect of this story is that is starts with a masquerade breach. New players may not know how to handle such a blatant breach and thats okay. I would let the crash slide- and the Camarilla in the background handles it. Breaches after the crash need to be handled with proper consequences.

> Option 3: New Blood

This is what my storyteller did to me and my first time players (and its also very close to the plot of CoNY). We were shovelheads. Embraced to make a huge mess for the Camarilla and die quick deaths. We were all thin-bloods.

The last thing the pcs remember is the sweet rush of ecstasy washing over them, before clawing out of the earth and driven mad by an insatiable hunger. The thrill of the hunt, and the sweet, warm blood on their tongue, nothing was going to be better. All three will awake next to each other, surrounded by the corpses they drank dry in their frenzy. What a way to play the name game! The players have three nights were they figure out their new condition or coverup their tracks (if they think to do it). They contend with their hunger and hatred of sunlight, wrestle with accidentally drinking their family member dry. After three nights, the Scourge comes knocking. Rather than outright killed, they are dragged to Elysium. For some reason, they are adopted by an upstanding member of the Camarilla- or the Prince orders a political rival care for them (hoping they fail). The players are the errand childer of this kindred, and slowly they figure out what they have been gathering through all these errands....

This one lets the characters all have the moments where they discover their disciplines and powers- and bestial tendencies. It naturally flows to allow players to slowly discover the rules and mechanics as well. All players must play fledglings for this tale.

This story is much more a personal tale than a political one. Eventually politics makes its way in...but it does not have to be a focus.

This story has less of a hook and more of a “Figure it Out” survival mode until the errands begin. The story is how the character’s react to their condition. It very quickly lends itself to a narrative of finding your own path in the night, rather than mindlessly obeying.

So here are a few questions that I ask myself when crafting a chronicle story:

1. What kind of story do you want to tell? Not asking for a plot hook, I’m asking for a general concept. Is it a tale of good triumphing over evil? (Not necessarily a wrong answer, but if you wanna play good guys...vampire is not the best game for that). Is this a chase? Is this a race against time?

2. How do you want your story to make your players feel? Do you want to tell a story that invokes as much dread as possible in your players? Do you want them to feel ultra powerful? Vampire is both a power fantasy and a dread inducing game- it can do both.

3. If you don’t know what kind of story you want to tell, switch gears to worldbuilding. CbN has so many NPCs with the rumors already written for you. Its your setting, perhaps switch two rumors around with prominent NPCs. Decide which ones are true in your setting- Maybe Primogen Annabell did kill her predecessor. Perhaps the Lasombra are attempting to infiltrate the Camarilla as everyone fears- but no one is able to prove it or stop it. Deciding what is true, false, and undetermined usually blossoms into hooks and stories worth investigating.

4. What is a historical event of the city that the Vampires would have endured/ scars would have remained? For example, in my chronicle set in Richmond, the tale of the Richmond Vampire is true. Depending on who you ask, it is the Camarilla’s best or sloppiest cover up. Have the chronicle coincide with the events and the coterie live through them. No one said this must take place in 2021- you can do 2015, 2008, -hell go back the 1990s. Its actually super fun if you set your chronicle in the 90s and your Malkavian is using phrases from 2020.

5. One of my things I do when writing scenes and moments is play Dread by myself. Dread is a role playing game played with jenga. There are no dice rolls, if you want to attempt something, you have to pull pieces from the tower. If the tower falls, you die. If there is a moment where I really really really dont want to pull from the tower, though the reward for succeeding is so so sweet- I keep the moment. If its really easy to shrug and go eh, I can live without performing that action- go back and rewrite it. If you have no incentive to pull from the tower, why would they?

6. Examine your player’s desires and ambitions- and do not neglect them in your chronicle. The plot wont magically allow all of them to achieve their ambitions. However, provide opportunities for them through the plot. Its on them to strive for what their character wants- its on you to make them struggle but have the path to get there. For example, if a player wants to become a Baron, provide a political opening. Perhaps then by announcing their power, they have made a bigger name for themselves and it has become harder to hide. Perhaps by doing this, the kindred they owe a favor is suddenly much more vocal about it.

Here are some suggestions for handling new players:

> You are going to have to handhold them through some things. New players to vtm won’t be able to see the cascading political web and how the consequences of their actions will ripple into waves. I like to use Wits+Insight and call it Common Sense. Common Sense was a merit in V20- and damn is it WONDERFUL. All they need is just 1 success (they can take half) to have you explain how whatever plan they just thought of is actually a TERRIBLE idea.

> Do your RPG consent list. Know what is safe to discuss and what is off the table. I highly recommend utilizing something my Storyteller used for my first chronicle, and subsequently I use for all my ttrpgs now: Invoking the Veil. The metaphor is that you are slowly lessening the intensity of a scene- as if raising the opacity or looking through layers of fabric. Eventually, there is too much fabric and you can no longer see the scene. If something is too intense, the ST or the player may announce they are invoking the veil. Reduce the scene by lowering music, speaking in third person, or avoiding heavy descriptors. You can reduce it further to just dice rolls. Role play stops, and the consequences of the scene are solely dictated by the dice. Or fade to black. If a player is repeatedly fading to black on something- ask to talk to them about it. Clearly something is too intense and they are not having as much fun as they can. Debriefing after a session is also a good idea. Do something silly! Share and check all the memes in the discord chat. Its important to make sure you and your players know that at the end of the night- its all just a game.

> I find the sabbat and new players don’t tend to mix well. You may absolutely still use the sabbat in your chronicle! But the dogma and philosophical ideals of the sabbat can be offputting and downright upsetting to a first time player. You may absolutely build to it- that’s what I did to my players. And in the moment of the truth, they chose to cling to humanity.

> The taking half mechanic is your friend! V5 says players may announce how many dice they are rolling- and if the dividend is greater than the DC- they auto succeed. This streamlines play. Of course, you as the Storyteller may say this is a roll they are not allowed to take half on. Usually these are contested rolls (combat).

> The three turns and out rule keeps combat intense but not too lengthy. It actually streamlines encounters super super well.

> My ST used a phrase, “The quickest way to kill Cthulhu is to give it a healthbar.” If Methuselahs and Elders are involved in your game- avoid giving them stat blocks. This cultivates a conflict that new players must find a way to overcome without brute force combat. It makes them think critically and defy these super old antagonists through narrative means. This also gets the notion out of your and their heads, “if they die, its over.” Its never that easy. Never.

#steph answers questions#thanks for asking!#vtm#vampire the masquerade#vamp tag#storyteller vibes#ghostravens

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

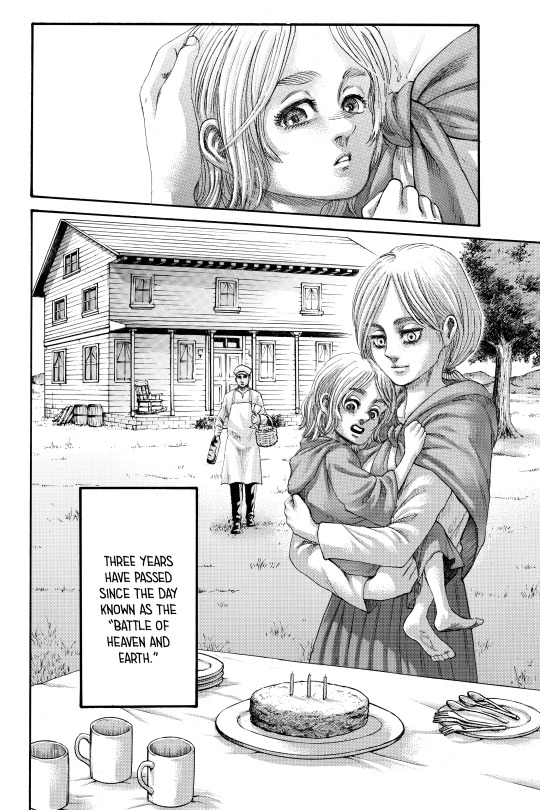

I am so very sick and tired of the toxicity that’s been poisoning the snk fandom as of the last couple years. I gave myself time to digest the ending and my feelings on it, before embarking in a journey to debunk many misconceptions and critiques I’ve seen floating in the fandom.

By the way, by no means I think this ending is perfect. I think this is textbook execution by Isayama to tie together every loose end left behind in an orderly manner, and I think that it was a bit rushed and oversimplified. I would’ve wanted more of Eren and Armin’s conversation, more of the squad realizing what his true goal had been, and some narrative choices I don’t 100% agree with. But still, what I saw in other fans’ critiques post 139 frankly appalled me, so I feel the need to make this. Also, this obviously are my own interpretations, I am not Isayama himself lol

“Ew, so Eren did pull a Lelouch after all”

No, Eren did not pull a Lelouch. While his action and the final result may seem similar, I find very different nuances between the two. Lelouch wanted for the whole world to be united in fighting against him, and thus he made himself the world’s greatest enemy. His will to turn himself into a monster was selfless. Eren didn’t give a damn about the world, he had no noble intentions whatsoever. He said it in chapter 122, his goal was to protect Paradis and, more specifically, his closest friends. He turned himself into a monster, killed 80% of human population, and endangered the lives of those very friends he wanted to protect, so that by stopping him, those friends could be safe. Eren had no intentions to break out of the cycle of hatred or unite the world against himself, he just wanted to give his friends a chance to survive, and that is not selfless, it’s selfish. Eren’s goal was incredibly selfish, and biased, and driven by his feelings instead of rationality. Nothing like Lelouch!

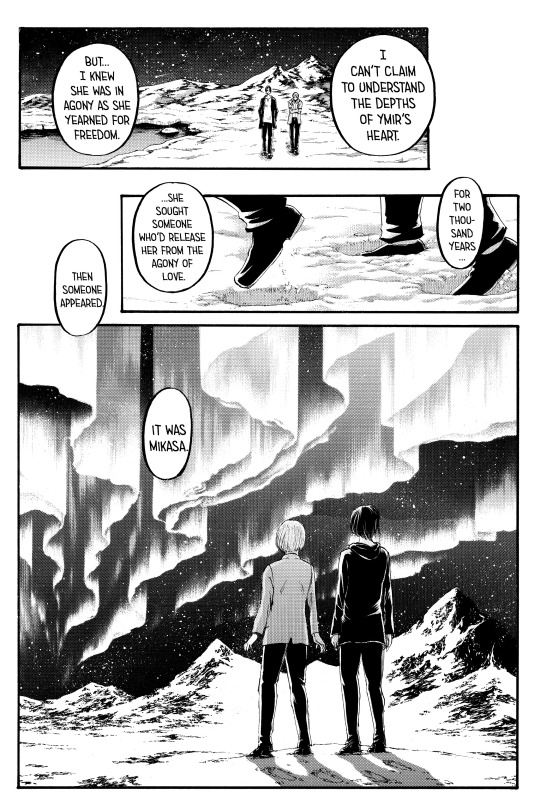

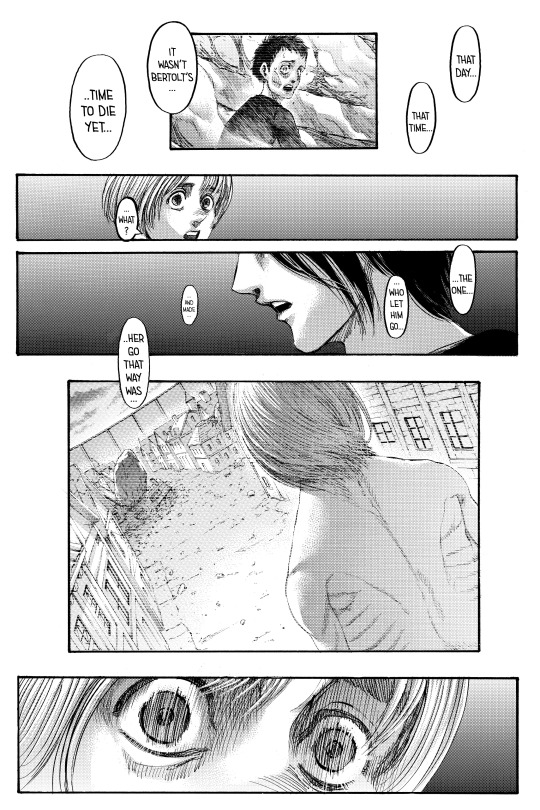

Now this, this I myself am not the greatest fan of. I feel like it makes that great scene in chapter 122 loose a bit of its strength, Ymir obeying the king for 2000 years just because she loved him. Honestly, I always thought there was a bit of Stockholm Syndrome going on, but I didn’t think it would be the only reason. However, like it or not, it’s undeniable that it makes perfect sense in the narrative that aot has always strived to tell. Love has been a theme strongly woven in the story, and it also draws a great parallel between Karl Fritz/Ymir and Eren/Mikasa. Ymir was a slave to her love for King Fritz, just like Mikasa was a slave to her love for Eren, in that she struggled to accept reality until the very end despite the atrocities that Eren committed. Ymir stayed bound by her love for King Fritz, until she saw Mikasa break from her own poisoned love, aknwoledge it, and kill Eren despite of it, or maybe because of it. Only Ymir knows that one, heh. But the point is, Mikasa showed Ymir that she could break free of a toxic love, she was that someone that Ymir had been waiting for to finally free her of her burden.

“What? But that makes no sense!”

Now, on my first read, I simply thought that Eren had ordered Dina to avoid eating Berthold, and that he had made her walk down that road unaware that his mother was trapped (because we know that the Attack Titan’s future memories aren’t infallible, there are still gaps), killing her indirectly. I’ve since then read some theories stating that Eren willingly killed his own mum in orther to give kid himself a reason to feel enough hatred to kickstart the whole story. Honestly, I like this version maybe more! But let me explain to you why this is not a plothole, like many people think. In this same chapter, we have Eren explaining how the Founder’s power works in synergy with the Attack’s: “There’s no past or future, they all exist at once”. This means that time travel in aot doesn’t work in a manner where Eren extracts himself from time and space, and from a separate realm he operates on the past. The way I understood it, the mechanics works kind of like Tokyo Revengers’ time travel. MInd you, I only watched episode one, so my understanding might be jackshit.

Spoilers for Tokyo Revengers’ episode one. In the show, the main character loses consciousness and finds himself reliving his past. He interacts with someone in this “new” past, and when he wakes up again in the present, past events had been over-written by the changes he made. I think this is how aot timetravel works, with the exception that, since past and future (and present, of course) all happen at once, side by side, there is no old past to be rewritten, neither a future to return to, and present Eren wouldn’t be aware of the changes that his future self would make. It creates sort of a time paradox, yes, in the sense that there’s a loop where present Eren’s mom has been eaten because future Eren, in the future, operated on the past by causing past Eren’s mom to be eaten, but all these Erens are one and the same, as all timelines exist at once.

“Boo-hoo they ruined Eren’s character, he’s such a wimp!”

I have to confess (isn’t this appalling, that this is a thing that I have to confess, what the actual fuck), I am an Eren stan. I absolutely do not consider myself a Jaegerist, I think Eren’s option was better than Zeke’s, yes, but it was morally wrong and awful and he absolutely was not only in the wrong, but also if he wasn’t dead I’d want him to be punished for his crimes. I didn’t particularly enjoy him pre-timeskip, and I started to like him because I found his evolution fascinating. I wanted to understand his motives, what was going on in his head, he was a puzzle that I wanted to solve. Maybe because I’m a psychologist, who knows. Anyways, if you’re an Eren stan only because he acted like a chad and now you cry his character was ruined, I’m sorry to say, you never understood him. Eren was not a god, he was not a strategist playing 5d chess with perfect rationality, Eren was the same he has always been. He was a young man spun along by his passions. Eren feels things with burning intensity, he lets himself be driven by his emotions. He almost flattened the world because he was disappointed that he and his friends weren’t the only human beings inhabiting it, for fuck’s sake, he’s always been irrational, selfish, and immature. Of course he doesn’t wanna die, of course he want’s to live with all of them. You really expected a 15 year old hot-headed brat to become Thanos after he suddenly found out he killed his own mum and all his dreams had been crushed? Of course he felt conflicted, of course he suffered, of course he wanted to live, “because he was born in this world”. Honestly, when I read his meltdown, I felt relieved that his character hadn’t been turned on its head, it was heartbreaking to see that he really was the same brat he’d always been, that he’d tried to steel himself to do horrible shit for his friends’ sake and that he felt bad about it! It made me appreciate his character a lot more, I felt nostalgic towards the times when I was irritated by his screaming and pouting. Suffice to say, this is also my answer to all those people that believe his internal monologue to convince himself the Rumbling was what he really wanted were bullshit since he “pulled a Lelouch”. How can it be bullshit? Maybe he planned to be stopped, but he also said that he thought he would’ve still done it if they hadn’t. He also said that killing a majority of the population was something that he wanted to do, not a byproduct of the alliance not stopping him early enough, because with the world’s militaries in shambles Paradis would’ve had time to prepare accordingly. Anyways, of course he needed to convince himself to do this awful thing even if he knew he wasn’t gonna succeed completely, can you imagine how horrible it would be to know your only chance is to kill thousands?

I also maybe think it was because of the spine centipede thingy? When Eren says “I don’t know why I did it, I wanted to, I had to”, he gets this faraway look on his face and we get a zoom in on one of his eyes, which is drawn very interestingly and kinda looks like the Reiss’ eyes when they were bound by the War Renounce Pact? So maybe it was also the centipede’s drive to survive and multiplicate that forced Eren to do the Rumbling so that its life wouldn’t be endangered. I don’t know how much I like this, I feel like it takes some agency away from Eren and also makes it feel like he’s not as responsible for the genocide he committed that we initially though, which mhhh maybe not, let’s have him take full responsibility for this. As I said, I’m not defending Isayama blindly, I do have some issues myself with what went down.

“What the fuck, did he say thank you for the genocide?”

Guys c’mon, this is like,, reading comprehension. Yes, it was poorly worded and a bit rushed, but by now you should have full context to make an educated guess on the fact that no, he didn’t thank him for committing a genocide what the fuck you guys. Armin started bringing up the idea that maybe they should have Eren eaten because he was doing morally questionable things ever since the Marley Arc, which for manga readers was like what, 2018? Isayama has been showing for three years how not okay Armin was with Eren’s actions, how could it make sense for him to thank him for a genocide? You see some poorly worded stuff, and your first instinct is to ignore eleven years’ worth of consistent characterization to jump to the worst interpretation possible? Let’s go over this sentences and reconstruct what they mean.

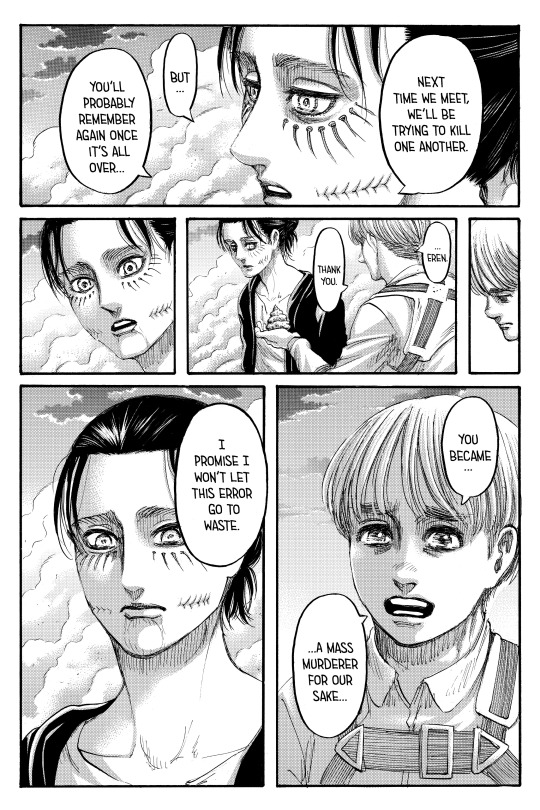

“Eren, thank you. You became a mass murdere for our sake. I won’t let this error go to waste”. Armin recognizes that Eren had no other choice, but does not condone it. He clearly calls it an error, which feels like an euphemism but for all we know the japanese original term used could’ve been harsher. Point is, he clearly states he think what Eren did was wrong. But he recognizes that Eren’s awful doing opened up a path for Paradis to break out of the cycle of hatred. Not a certainty, but an opportunity. He thanks Eren for giving them this chance, and promises not to waste it, even if it was born out of an atrocity. He thanks Eren for sacrificing himself for their sake, even if he doesn’t agree with the fruit of his labor, so to speak. He’s thanking Eren for the opportunity that his actions gave them, not for the actions themselves! Where the hell do you read “thank you for the genocide” guys, sheesh. I’m mad at y’all.

“How could Eren send MIkasa memories if she’s an Ackerman and an Asian, and their memories can’t be manipulated by the Founder? I call plothole!”

Now, here we’re going into speculation territory, so you’ve been warned. I don’t think that that information they gave us was true, about Ackermans being immune to memory manipulation. We know at least that the clan is in some way subject to the Founder’s power, or Mikasa and Levi wouldn’t have been called in the Paths by Eren multiple times. Stories never being entirely true or false, or relativity, better said, has been a strong theme in the story, we know this by Marley’s and Eldia’s different accounts of history compared to the actual Ymir backstory we got. So who’s to say that the belief that Ackermans aren’t manipulable is the truth? Maybe they’re just hard to control, not impossible. We know that by the Founder’s ability Eren experienced past and future happening simultaneously, so he could’ve very well been trying to send those memories into Mikasa’s head ever since the beginning of the story, only just succeeding in chapter 138. It would at least explain Ackerman’s headaches as Eren trying to manipulate their memories and failing. Of course, we’d need Levi side of thing to know for certain, as he had headaches too and we weren’t shown in the chapter if Eren spoke to him in paths like he did with the rest of the squad. We know he didn’t talk to Pieck, but he even went and spoke to Annie who he basically hadn’t seen since Stohess, so I hope he spoke to Levi too. Who knows, maybe he even spoke with Hanji, but she died before she could remember. I wish we were shown that, honestly, I’m sad that it was skipped, especially after Levi said in an earlier chapter that “there was so much he wanted to tell Eren”. Fingers crossed for the anime to expand on it.

“So Historia’s pregnancy was useless”

What? No, it wasn’t useless! Eren told her to get pregnant to save her life, so that she wouldn’t be turned into the Beast Titan. If she became the Beast Titan, then Eren would’ve had to enact the plan with her instead of Zeke, and yeah, Ymir brought the power of the titans with her, so theoretically Titan Shifter Historia would’ve had her time limit removed, but we saw that the only way for the Alliance to stop the Rumbling was killing Zeke, so Historia would’ve had to die. Useless to say, when Eren talked to her about his plan, she was very vocally against it, so I don’t think she would’ve helped Eren with his plan. It was Zeke or nothing, and the only way for Zeke to keep his titan was for Historia to be unable to be turned, hence the pregnancy. Did y’all read the same thing I read? Anyways, she could’ve definitely been handled better, but she wasn’t necessary to the plot anymore, and her being removed from it in such a way was sad, yes, but it made sense.

“They massacred Reiner!”

Yeah, can’t really say anything about this. I definitely understand the sentiment behind this scene, which I appreciate. It’s to show that thanks to his Titan being removed and the times of peace approaching, Reiner was finally able to shed the weight he bore on his shoulders and “regress” to his more carefree persona he had when he thought he was a soldier, instead of a warrior. I am very happy for him, and I think it’s a nice conclusion to his arc, that he’s finally happy, but it could’ve been portrayed in a less comic relief-y way. It just sledgehammers all his characterization. Feels surreal that we saw him attempt suicide a couple month ago in the anime and now he’s sniffing Historia’s handwriting.

Guys, this absolutely sends me. There are people who unironically believe Eren actually reincarnated in a bird? Guys. It makes no sense, it violates every rule that Isayama established for his universe’s power system. How could he even reincarnate in a bird? Guys, c’mon, this is symbolical! Birds have been heavily used in aot to portray freedom, and this is a nice, poetic, symbolic way to show that Eren who lived his whole life chasing freedom and never actually got it, is finally free, like a bird, now that he’s dead. It’s also a pretty explicit nod to Odin, I think. Aot is heavily inspired by Norse Mithology, and I think there were some pretty clear parallels between Eren and Odin/Loki in the later arcs of the story. Eren has been shown to “communicate” through birds like with Falco in chapter 81, or with Armin in chapter 131. Emphasis on “communicate” because again, this is symbolic, I don’t think he actually spoke through the birds, he simply talked to them via paths, but birds are associated with Eren’s character (see also the wings of freedom, y’know?) and the shots were framed so to give the impression that he was talking through the birds, but he wasn’t. Symbolism. Anyway, I really think they were supposed to be a nod to Odin’s crows.

Aaaaand that should be it! Even though I most definitely forgot some other criticism on the chapter, it’s crazy the amount of negativity floating around. Hope I didn’t bore you!

#attack on titan#aot#shingeki no kyojin#snk#snk manga#aot manga#aot spoilers#chapter 139#aot ending#eren jaeger#mikasa ackerman#armin arlert#aot 139

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philip Purser-Hallard Q&A

Our final Q&A is with Forgotten Lives’ editor Philip Purser-Hallard. His story for the book, ‘House of Images’, features the Robert Banks Stewart Doctor, and opens like this:

‘The usual dreadful creaking and bellowing from the rooms above the dusty office informed me that the Doctor would soon be coming down to check on my progress. I really don’t know what he does up there to make that racket. If you asked me, I’d have to guess that he’s trying to invent a mechanical walrus, and enjoying some success.

‘Honestly, Auntie, I wouldn’t put it past him. My employer is a strange man, with obsessive interests and a deeply peculiar sense of humour.’

FL: Tell us a little about yourself.

PPH: I’m a middle-aged writer, editor and Doctor Who fan; also a husband, father, vegetarian, cat-lover, beer-drinker and board games geek.

A couple of decades ago I wrote stories for some of the earliest Doctor Who charity ‘fanthologies’, Perfect Timing 2 and Walking in Eternity (whose co-editor, Jay Eales, has contributed to Forgotten Lives). These led directly to my published work in multiple Doctor Who spinoff and tie-in series, starting with Faction Paradox.

Since then, among other things, I’ve written a trilogy of urban fantasy political thrillers for Snowbooks, and two Sherlock Holmes novels for Titan Books. I’ve also edited six volumes of fiction for Obverse Books, in the City of the Saved and Iris Wildthyme series. And I founded, coedit, and have written two-and-a-half books for, The Black Archive, Obverse’s series of critical monographs on individual Doctor Who stories. (Mine are on Battlefield, Human Nature / The Family of Blood and Dark Water / Death in Heaven.)

But those two anthologies are where it all started.

FL: How did you conceive this project?

PPH: I’m fascinated by unconventional approaches to Doctor Who, an interest fostered by three decades spent reading the Virgin New Adventures, the BBC Eighth Doctor Adventures and such experimental spinoffs as Faction Paradox and Iris Wildthyme. (Again, I’m glad to have worked with alumni of those series, including Simon Bucher-Jones and Lance Parkin, on Forgotten Lives.) I love the Doctor Who extended universe when it’s at its most radical, questioning, deconstructive and subversive. The Morbius Doctors, standing outside the canon with a foot in the door, are a great vehicle for exploring that.

Once I had the idea for the anthology, the charitable cause followed naturally. These are the lives that the later Doctors have forgotten, and that loss of identity and memory could only put me in mind of the experience of my grandmother, who lived with Alzheimer’s for many years before her death. Gran was a shrewd, intelligent woman, and it was deeply upsetting to see her faculties steadily deserting her. All charities are going through straitened times at the moment, of course, and all of them are in need of extra support, but I felt Alzheimer’s Research UK was particularly worth my time and effort.

FL: Each story in the book features a different incarnation of the Doctor. Tell us about yours.

PPH: As I’ve written him, the Robert Banks Stewart Doctor is a grumpy, ebullient name-dropper with quietly brilliant detective skills and a penchant for deniable meddling. So far, so quintessentially Doctorish, but this incarnation also has an unusual interest in magic and alchemy, a long-term mission on Earth, and an old nemesis demanding his attention.

FL: These Doctors only exist in a couple of photos. How did you approach the characterisation of your incarnation?

PPH: The photo of scriptwriter Robert Banks Stewart that appears onscreen in The Brain of Morbius has a grim look on his face, but there’s another where he seems to be having a lot more fun in the costume. I played with that contrast by making his Doctor a man of excessive, rather theatrical moods, curmudgeonly and charming by turns. With his fur collar, there’s something rather bearlike about him, which made me envisage as quite physically large.

I also love Paul Hanley’s artwork for the character, where he elaborates on the costume to portray this Doctor as a kind of renaissance alchemist – Paul says ‘I like the idea that this is the Doctor who was most interested in “magic”, psychic phenomena, etc.,’ and I certainly leaned into that.

Banks Stewart’s own persona comes through in the Doctor’s Scottish accent and in some of the story choices. Both the Doctor Who scripts he wrote are set in contemporary Britain, so this Doctor’s story is a ‘contemporary’ one – though the timeframe I was envisaging for these forgotten Doctors means that works out as the 1940s. Banks Stewart created the TV detective series Bergerac and Shoestring, and so this Doctor fancies himself as a detective. And he also wrote for The Avengers (and for the Doctor and Sarah rather as if they were appearing in The Avengers), so there’s a flavour of that in the action, the whimsy, and the relationship between the Doctor and his secretary, Miss Weston.

FL: What's your story about?

PPH: The Doctor is in early-1940s London, observing the geopolitical progress of World War II on behalf of the mysterious power he represents, when he’s distracted by a burglary carried out by men bearing a close resemblance to the comedy duo Laurel and Hardy. This brings him into conflict with a figure from his past, a sorcerer known as ‘the Magus’, who represents another cosmic faction with its own agenda.

FL: The stories are intended to represent a ‘prehistory’ of Doctor Who before 1963. How did that affect your approach?

PPH: Since the eight forgotten Doctors are supposedly the incarnations preceding Hartnell, it was part of the concept from the first that these stories would reconstruct – thematically and narratively, though not in terms of TV production values – Doctor Who as it ‘would have been’ in the 1940s, 50s and early 60s. In one sense that’s a very conservative approach, but it also highlights the ways in which Doctor Who in reality has been a product of its various times.

For my own story I drew on two mid-20th-century influences – Charles Williams, a friend of CS Lewis and JRR Tolkien, who before his death in 1945 wrote occult thrillers infused with his own very eccentric brand of Christianity; and the Basil Rathbone Sherlock Holmes films set during World War II. Between them they led me to this story of a magicianly Doctor doing detective work and getting involved with affairs of state during the Blitz, and to provide him with his very own sorcerous Moriarty.

FL: Who would be your ideal casting for a pre-Hartnell Doctor?

PPH: The other authors have given most of the good answers already – Margaret Rutherford, Alec Guinness, Waris Hussein or Verity Lambert, Peter Cushing – so I’ll say either Boris Karloff or a young Mary Morris, depending on taste.

FL: What other projects are you working on at present?

PPH: I’ve got a short story and a novel for Sherlock Holmes in the works; plus another Holmes novel partly written, with a more unusual premise, that I’m trying to persuade someone to publish. I’m editing the next batch of Black Archives, of course, and writing our book on the Jodie Whittaker story The Haunting of Villa Diodati, which is due out in December 2021. And I have further ideas for original novels that I really need to devote more of my time to. One of them’s got vampires in.

#philip purser-hallard#forgotten lives#obverse books#robert banks stewart#the banks stewart doctor#morbius doctors#the brain of morbius#doctor who#dr who#doctorwho#drwho#fanthologies#paul hanley

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

a glass bell

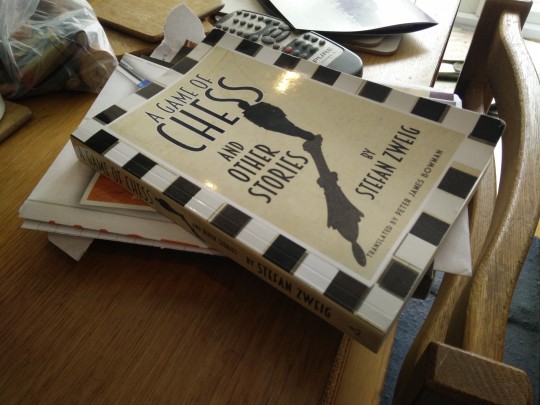

This book is a short collection of stories by Stefan Zweig. There are only four of them collected here. I’ll describe each one in turn.

The Invisible Collection describes a visit to the home of an old blind man by an antiques dealer. The dealer arrives expecting to get a look at a set of valuable prints at the home of an old customer. But when he arrives, he finds himself complicit in a sort of ruse with the blind man’s family. The prints have been sold long ago. The pages in the folios still so lovingly turned by the owner’s hands are blank. The story has the subtitle ‘An Anecdote from the Years of Inflation in Germany’ — on that level, the metaphor is perhaps a little too direct. Like money, those pages have a value which essentially depends on a sort of collective delusion as to their worth. The story has that heightened quality of anguish that is common to Zweig’s work. It is essentially an overwritten, over-dramatised rendition of a poetic image; but the image is haunting regardless.

Twenty-Four Hours in a Woman’s Life is a little more developed. It is tempting to call it cinematic, given that it is so driven with the power of a direct, silent image — in this case a figure glimpsed repeatedly from across a street, or across a room. That said, as with all the stories in this collection it uses a frame narrative. After a minor scandal in a country hotel, an older woman recounts to the narrator an event from years ago. She tried to help a man, a gambler, who had lost a huge amount of money; she ended up falling for him; he ran away; she couldn’t stop him gambling. As a conventional story it is perhaps the most complete thing here. It is also madly overwrought. Zweig was popular in his lifetime but he was not always well-liked, and in this story it’s easy to see why. Every emotion is heightened to breaking point.

Incident on Lake Geneva is comparatively slight, and highly restrained. It is not much more than ten pages long. In the year 1918, a naked man is found by a fisherman, clinging to a set of broken spars; when he is brought ashore, only the ex-manager of the local hotel can speak to him in his native Russian. He is a nameless conscripted soldier who somehow became separated from his regiment, and is entirely lost. It is unclear how exactly he came to be on Lake Geneva — it seems he picked west when he should have wandered east. At any rate he is stranded in neutral Switzerland — he cannot leave without traversing other non-neutral countries. He is distraught and, in the end, he drowns himself in the lake. The story is a bleak, minimal thing. It concludes on a stark image: ‘…a cheap wooden cross was placed on his grave, one of those little crosses marking the fate of nameless men that cover our continent from end to end.’

A Game of Chess is perhaps one of Zweig’s most famous stories. (Oddly, it has had various titles in English under various translators: ‘The Royal Game’, ’A Chess Story’, ‘Chess: a Novel’ or sometimes simply ‘Chess’.) The narrator is on a ship bound for Buenos Aires when he discovers that a famous chess grandmaster named Czentovic is on board. Czentovic’s story is well-known: he was the uneducated son of a poor peasant when his matchless talent for the game became apparent. The narrator is fascinated by this imposing, uncouth figure, and in an effort to draw him into a game he falls in with an arrogant passenger wealthy enough to put up enough cash to draw Czentovic’s attention. The two of them challenge him as a team, and they are almost beaten when they draw the attention of a third — a nervous stranger named Dr B who has his own uncanny gift for the game. He claims not to have played for twenty-five years, and his advice seems to come from a place of desperation, but he seems like the only one capable of defeating Czentovic. Soon enough he tells his own story.

Dr B was resident in Austria when the Nazis annexed that country. He was taken prisoner by the Gestapo, who believed he was keeping information from them regarding the old Austrian monarchy; being an otherwise respectable middle-class citizen, he was kept under arrest in the relative comfort of a hotel room. But with nobody to talk to and nothing to read or watch or do, his solitary confinement became tortuous. It is a haunting picture of isolation:

‘I lived like a diver in a glass bell in the black ocean of silence, a diver who guesses that the cable connecting him with the world above is severed and he will never be drawn back up from the soundless deep.’

The most affecting image here is not the darkness or the silence — if those can be called images — but the glass bell. The thing which, in spite of everything around it, keeps us aware that there is some distinction between the self and the void. It is from the awareness of this distinction that the pain arrives.

One day Dr B finds solace. He steals a book from the coat pocket of an officer which turns out to be a book of chess problems. At first he is disappointed, not having any pieces or a board, but eventually he becomes fully proficient in playing the game entirely in his head. For a while he becomes happy and mentally stronger — but he cannot rid himself of his unspoken obsession with chess. The 150 problems in the book soon become exhausted, and to maintain his interest he is forced to play against himself.

‘If black and white are one and the same person, a preposterous situation is produced in which a single mind is supposed both to know something and not to know it, so that its white self should, by self-command, forget all the aims and intentions of its black self a minute earlier. The premise for such dual thinking is a totally split consciousness, with the brain’s functions being switched on and off like a mechanical apparatus. Wanting to play chess against oneself is thus as much of a paradox as wanting to jump over one’s own shadow.’

Dr B describes the effect as akin to a split personality. But it is not simply a duality — to compute every one of the many alternative moves effectively requires a multiplication into countless simultaneous selves. The strain becomes too much. After a violent attack on a guard, he ends up in a hospital. Eventually, with some help from a benevolent doctor, he is released. He leaves Austria and tries to forget about chess entirely.

A Game of Chess was the last story Zweig ever wrote. He and his wife had been living in exile in South America during the second world war; a day after posting the manuscript to his publishers, they committed suicide. It is hard to avoid thinking about this while reading this story. At first it seems much like most of his other stories — the format is the same, with the heart of the matter being framed as an encounter with a stranger in some marginal travelling space. But where the drama should be is only a terrible void. There are no questions of shame or moral or ethical responsibility; there is only a man kept in a room forever, slowly losing his mind.

The coda of the story is, as you might expect, a match between Dr B and Czentovic. The latter finds a weakness in B’s otherwise impregnable approach — B must play quickly. He works to the speed of his own brain, and so any kind of forced delay in between moves becomes intolerable. And so Czentovic begins to take longer and longer to move until B begins to become confused. Errors are forced from his opponent. He loses. And in this, we glimpse something uniquely cruel. It is not so much that Czentovic behaved in an underhand way because he couldn’t find a way to win on his own terms — that much might be expected from any cunning sportsman. The cruelty comes from the spectacle of a man finding another man’s weak point and pressing down on it with all his strength. It is a uniquely horrific sort of exploitation. But this is what competition does to us. Perhaps society relies on men like Czentovic in order to go on functioning.

The chess games that went on in Dr B’s head were sustained by the idea of constant, total multiplicity: given that both sides were always ultimately B’s side, there could be no real process of elimination — no winners and losers. There could only be an endless selection of moves, categorised as ideal, optimal or otherwise. The confusion would become total, but he could never really defeat himself when the only opponent was his own expectations. But every game of chess that happens in the world outside B’s head must result in the ultimate submission of an individual. Czentovic understands this, and places B in a situation which he cannot survive. It is not sufficient to calculate the perfect move from every given variation when you suddenly find you have forgotten the rules.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Serious non-troll: What if you like the cop-outs and the scrambled bullshit plots and the nonsense towers of half-constructed ideas? I agree that for example Nomura is a goddamn crazy person but I find his convulsions fascinating and want to see more of them.

i mean, you’re entirely within your rights to do that. it’s just frustrating that there’s visibly no effort put into any of it, and he’s just writing for the sake of what makes the trailer look good, and that’s been 100% to the detriment of the story ever since he’s started doing it

i’m not even inherently opposed to ridiculous convoluted bullshit. i’m one of those pretentious fuckheads that unironically likes End of Evangelion and thinks it made perfect sense, obviously, duh, with all its absolute nonsense of adam and lilith and rei being a god-analogue from absorbing both the white and black seeds and allowing shinji to dictate the ultimate outcome of third impact in the culmination of a couple of really fucking long and extremely obtuse character arcs. i mean, hell, i’m 38 chapters into a fic that is running off nothing but weird high-concept ideas of how reality and parallel universes work and abstract metaphor andsleep deprivation. in any other circumstances, i’m fine with convoluted batshit nonsense.

i think the best way to explain the heart of the issue is to look at what happened to the matrix trilogy. or actually wait this is tumblr, everyone’s in high school and would’ve been foetuses or something when Revolutions came out. homestuck, then. we’ll look at homestuck.

okay so homestuck. remember when that was as big as it was? initially, the big stumbling block was the slow pace of act 1 where john just kind of fucks around throwing glass at clown dolls for a while and if you weren’t into that kind of humour that was where the comic immediately lost you, but what ultimately got the ball rolling was [S] WV: Ascend. the general metric back then was if you weren’t hooked by that one, you wouldn’t like homestuck at all, and for many people that was the point of no return. the reason WV: Ascend was as big of a deal as it was is that we’ve been seeing a bunch of disconnected nonsense happening all over the place, and this is the first time we see our first major time loop actually closed, with the promise of a few more being set up. all that supposed joke nonsense we’d been watching the whole time? it actually mattered, surprise! from there, the narrative spends a lot of time introducing a lot of new concepts – we have captchaloguing and paradox slime, and time travel, and doomed timelines, and exiles and future versions of planets from a parallel universe the metanarrative being perpetuated by the author being diagetic and fuck knows what other things i’m forgetting about. and then, to throw you for a loop twelve whole other characters show up on top of that. so then the narrative needs to spend time establishing who these people are and what their relevance to the story is – which it does, by having them be active participants in the first arc as things go on. this ultimately culminates in [S] Cascade, where we see all these different concepts eventually tie into one another because they were deliberately set up to, and it’s at that point that you figure, well shit we’ve hit a point where all the time travel stuff has finally come to a head. and with it, you’d expect it to also bring all the character stuff to a head too, but instead hussie has an entire extra act to go so we can’t have that resolve yet.

so in the meantime, here are 20-ish whole other characters doing some other things. but we don’t have time to establish what’s effectively the silmarillion by now, so we have to speed past it, meaning we aren’t given a chance to care about these new people. but we can’t have a chance to care about them either, because we still have to tie all this into 5 whole previous acts that are meant to feed into this. at this point, homestuck is visibly collapsing under its own weight. character arcs are forced to fart around in circles because the status quo can’t change because we still need to make it to endgame with these character dynamics more or less intact. but that’s boring to read so we’ll do this entire “what if” thing and then retcon it all out of existence, and then have the fact that you can retcon things suddenly become vital to the resolution of the coming in place of anything we’ve already established previously – not the time travel, not the parallel universe with the trolls, not even the whole thing with the Scratch leading to the alpha kids being here in the first place – when the mechanic was only introduced in the first place to sloppily patch a story together that had long since devolved into infodumps that served to paint hussie further and further into a corner as he was forced to define his lore to get the plot to keep moving forward despite the fact that the narrative wasn’t focusing properly on the people that could make that happen anymore because the story had since switched focus from those people almost entirely.

and in the meantime the damn thing got eaten up by filler, and suddenly characters from that filler are showing up like they were totally relevant to the main story the whole time even though literally nothing they did in their own subplot had any direct bearing on the story at large, unlike the initial 12 trolls. why yes, Alternate Universe Calliope was a completely necessary addition to the story! didn’t you see our important sidestory thing where they do Stuff, and then her showing up in the climax to resolve some other things that are sorta disconnected from the main plot anyway?

not to mention the shipping. nothing ruins a story faster than throwing in a love triangle or eight, and then immediately invalidating all the character growth that happened on top of that anyway by having it literally never happen. not that it would’ve mattered anyway, because remember, we never actually got to have any of this really developed to begin with.

by the time we hit end of act 6, there’s been so many new concepts haphazardly stapled onto the story and so many threads brought up and discarded entirely when we already established back with [S] Cascade that the story works best when they actually do this and it is doable, that it stops being merely complicated and off the wall, and starts being spread too thin, incomprehensible, and ultimately no longer part of a whole narrative deliberately comprised of interlocking storylines. shit’s just kinda happening at you, and rather than getting to see parts of a text interacting as a result of them coming from somewhere for the express purpose of then going to somewhere, you’re just being asked to accept that, yup, that’s a thing that’s going on right now. neato. sure is some stuff happening and whatnot. and in the end, for all that posturing, it didn’t even do anything. in pre-cascade homestuck that wouldn’t have even been a full flash. a bunch of nonsense happens, and then They Fightan Good, and then it’s over and there’s not a single time paradox or meta-interaction to be found. none of the stuff they built up to over all these years mattered, and neither did any of the stuff they just threw in, either.

i’m sure you see what i’m getting at with this.

(also he treats the women in his stories like shit and quite frankly i’m sick of it and even more sick that people keep giving him a pass for it because it’s practically reached parody levels at this point , so there’s that)

i have no problem with convoluted twisty bullshit in and of itself. but it has to accomplish something aside from just existing, and nomura doesn’t do that. by his own admission, kingdom hearts wasn’t planned, and it shows really badly. characters and entire story mechanics and plot lines are introduced solely for the sake of introducing them. they don’t go anywhere or build to anything, because they can’t, because fuck we have to stall for kh3 shhhh just keep adding more soras and hopefully no one will notice. i think the last time any of this actually mattered was kh2, and even that had a lot of the issues i’ve mentioned here. as a result of all of this, the character arcs suffer a lot, and you’re left with nothing but a big ball of plot twists that goes nowhere, and a bunch of characters that only somewhat have anything to do with any of it.

i don’t feel like it’s overly nitpicky to find this kinda gross and seriously insulting of the audience’s intelligence. it’s just lazy time-stalling. i get that people sometimes really don’t care about stuff like narrative and character development and are just here to see riku punching mike wazowski in the teeth or whatever, but i think it’s disingenuous to pretend that these aren’t nonetheless important parts of a game’s construction – especially a studio that used to openly pride itself on selling games with a focus on story.

and the genuinely frustrating part is, no one cares. people are gushing all over everything square puts out because it’s square, so they know they don’t have to put effort into their stories. i’m well aware i’m in the minority for saying that these games are bad. but i also thought we were done with treating, “it’s just a video game, bro! why do you care so much about the story having quality as a narrative? this isn’t an english class!” as a valid rebuttal.

maybe i should’ve used the matrix trilogy instead. most people hate movies 2 and 3 for the weird “YOU’VE ALREADY MADE THE CHOICE/EVERYTHING THAT HAS A BEGINNING HAS AN END NEO” shit and the bonkers christ-allegory ending. i hate it because neo is about as interesting as the rock that cracked goofy’s skull open.

#asks#kangdan horfs#do i put this in the discourse tag even though its's not vii?#squid alienates kh fans#that's a tag now#hamsteak#Anonymous

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear Evan Hansen

So I developed an interest in this musical during my semi-recent Groundhog Day obsession, when thanks to following everything posted about GhD on Tumblr, I ended up on the periphery of the general Broadway/Tony discourse. Everyone was talking about Dear Evan Hansen, either how good it was or how overrated it was, and I stumbled across some post suggesting it involved teens with issues and suicide, at which of course my ears perked up because I am me.

I listened to the soundtrack and read a basic plot summary on Wikipedia. The songs weren't amazingly up my personal musical alley for the most part, but still pretty good, and I was quite intrigued by the character work in them - the increasingly obvious wish-fulfillment of Evan's story in For Forever, culminating in the choked-up repetition of "He's coming to get me", suggesting without having to say directly that actually no one came to get him; the repeated "falling in a forest" motif never quite saying he let go but making it clear this moment was more meaningful than one would expect long before the plot summary indicated we'd find out he'd been suicidal; Zoe's subtle denial in Requiem; the tragic irony of Evan inspiring everyone with a speech about how you will be found when he knows better than anyone that sometimes you won't. This was good shit! I wanted to try to see it on the same trip as Groundhog Day, but the tickets were all well sold out, and ultimately I more or less gave up on the possibility. (I'd actually missed that there was a lottery for the show, but we tried it when we were in New York and didn't win.)

It just wouldn't quite leave me alone, though, so with no prospects for being able to see it legitimately at any point in the foreseeable future, I ended up giving up and watching a bootleg.

(Excessive overcritical rambling about characterization, subtlety, etc. under the cut! It is very critical, so by all means scroll on by if that’s not your jam.)

After all the mental buildup, I ended up sort of underwhelmed by the actual show, unfortunately. When I listened to the soundtrack I'd filled in blanks, imagining all the rich development that might be happening in between the songs - Evan slowly growing closer to Connor's dad before To Break In a Glove, say. But actually watching it, it felt like there was a lot less development than I'd imagined. There isn't really anything about Evan growing closer to Connor's dad other than the song itself, or a lot of development for Connor's dad at all outside of it. Zoe's conflicted feelings about Connor, legitimate fear and hatred coupled with a strange, paradoxical longing for him to really have had a better side to him that actually loved her, are fascinating, but aren't really explored outside of what I'd already heard in Requiem and If I Could Tell Her - Zoe's role ends up being mostly about being the target of Evan's dubiously ethical romantic interest, without really tackling the things about her that were actually interesting.

When I first listened to the soundtrack, I didn't actually pick up on Jared or Alana existing as characters. I'm not great at discerning voices on a first listen, so while for example Sincerely, Me was a bit confusing, I parsed it just as a dialogue between Evan and the imaginary Connor in his head, with "Connor" making the sardonic suggestions to ridicule Evan's pathetic efforts in between theatrically reading out what Evan was typing. They were in the plot summary, though, so I figured it out eventually, and the Tumblr fandom was full of posts about Jared and Alana - how complex they were, how much people related to them, everyone shipping Evan with Jared (of course). So I looked forward to seeing more of these characters that the soundtrack didn't really show off.

As it turned out, though, they weren't much in the way of characters, really. There are a couple of lines about Alana's anxiety and how she also feels like she's alone and doesn't matter - but they're ultimately throwaways. Alana is mostly just a plot point, as the person who's invested enough in the Connor Project to care but still detached enough to start to notice and question the discrepancies in Evan's story. Her dialogue is almost entirely either pure plot advancement or jokes; she may be secretly troubled and anxious, and eventually she spells out that she originally latched onto the Connor Project because of that, but the show just keeps kind of making fun of her - the most prominent characterization she gets is the running gag where she acts like she was so totally close to Connor while making it obvious she actually barely knew he existed - and she doesn't really get to act out the complexity the show wants to imply. We never see the Connor Project affecting her life, or get a real sense that it's giving her meaning that she was lacking before; it's told and not shown. That makes sense for a minor character who's mostly there to play a role in the plot, but the fandom had made me expect a lot more, and I really think she could have been done a lot more interestingly if they'd just spent less time making jokes about her.

And Jared... is desperately unlikeable. A lot of people on Tumblr were criticizing the play for not punishing Evan enough for his actions - but at the same time everyone was in love with Jared. This is baffling, because as far as I can see, it's pretty much Jared who ropes Evan into this in the first place. Evan originally tries to tell the Murphys that Connor didn't actually write the 'suicide note', but they dismiss him and Cynthia acts extremely upset, and Evan is too timid to try to be firm and argue with these grieving parents in order to explain to them that actually their dead son had no friends. After this he's panicking and anxious about having to clear up the misunderstanding, but it's Jared who convinces him he absolutely can't tell them the truth and has to just smile and nod and keep up the pretense. After this, Jared relentlessly mocks and bullies Evan as the lie spirals out of control, makes a silly attempt to insert himself into it, gets mad when Evan says they must stick to the established story where Jared necessarily wasn't involved, then gets hurt and complains when Evan stops hanging out with him once he's got something else to do and other people who like him. Obviously Evan is in no way an innocent party here - he does start to latch onto the fantasy of this imaginary friendship with Connor and this doting family that wants and likes him, and soon he's clearly keeping up the charade for himself and not to make Connor's family feel better. But none of this would have happened if it weren't for Jared convincing him he absolutely needed to keep up the lie, yet what Jared says when it's all gotten out of hand isn't "Look, I'm sorry, this is wrong, I was wrong, you should have told them the truth from the start", but "You should remember who your friends are." Maybe Evan would remember who his friends are if you'd ever been anything resembling an actual friend to him, Jared! I gather stage directions and cut songs and so on show that Jared actually has a very low self-esteem and is covering up his insecurities with sarcasm and bullying behaviour, which is great, but I wish any of that really got through in the actual play, because in the actual play Jared is just intensely unsympathetic. As it stands, his narrative function is to show how friendless Evan is (the best he's got is this guy, who freely tells him he only hangs out with him because he's literally being paid for it) and to be the person who's callous enough to think lying to a grieving family about being friends with their dead son to save face is okay, because Evan is actually better than that and wouldn't have done it otherwise. Like with Alana, I'm sure there's something interesting there, in theory, that the actor taps into while playing him. But within the actual show, the way he acts by and large isn't interestingly informed by his insecurity; he's just being a mean-spirited, bullying, opportunistic asshole. He has no real redeeming qualities and then just kind of vanishes abruptly from the story towards the end, before he gets the chance to even react to the lie being (partly) exposed (which could have been a nice opportunity to show him being a non-dick for once).

I was also sad to discover that in the actual play, things that were subtle and interesting on the soundtrack are just spelled out. Evan explains in so many words near the very beginning, before we even hear For Forever, that he broke his arm because he fell out of a tree and the funny thing is nobody came to get him so he was just lying on the ground alone for a while. That beautiful, emotional repetition in the song - And I see him coming to get me. He's coming to get me. And everything's okay. - isn't using Evan's emotion as he makes up a false wish-fulfillment narrative to implicitly tell you about something that really happened; it's just a straightforward lie contradicting something established explicitly earlier on. There's nothing wrong with that, but man, I thought it was something sublime. Even stuff like To Break In a Glove - on the soundtrack, Evan says, "Connor was really lucky to have a dad who... who cared so much, about... taking care of stuff," and it establishes nicely, implicitly, that Evan's own dad never cared and never played baseball with him, which Connor's dad clearly understands in the pause that follows even though he doesn't remark on it directly and just reiterates his instructions about the glove. But in the actual thing, they spell it out. A moment that wasn't a big crowning moment of subtlety or anything but still nicely understated, trusting the listener to get the implied meaning without stating it outright, isn't even that. That's a bit disappointing.

I wonder if in some previous iteration of the story it used to be subtler, but they later made it more explicit to make it easier to follow. That or, you know, I extrapolated subtlety simply from having incomplete information. One of the two. (If it's the latter, though, I'm amused at how coincidentally good that incomplete information is.)