#'first they suffer because of napoleon then they suffer from the revolution then they suffer from the aftermath of the revolution!'

Text

My father went on a rant about Russian literature yesterday and it was most entertaining to listen to

#'they always suffer! all they know is suffering!'#'first they suffer because of napoleon then they suffer from the revolution then they suffer from the aftermath of the revolution!'#'look at mumu. is that your russian literature? do you think the man who wrote mumu knew how to be happy?'#'bulgakov was the only normal one there anyway.'#of course half of it was in jest but still dhfgdhdjd#txt

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Now I'm curious: what happened to Tallien to consider him a worse loser than Barras? I only know his involvement in Thermidor and the fact that Theresia left him after all the mess he did to go with a richer banker... Did he embarrass himself in other ways?

How much time do we have? Look, I don't know a lot about Barras, but nothing - nothing - can be as embarrassing as Jean-Lambert Tallien. He is the biggest loser both in terms of "a flop" and "who lost during the revolution" (and he lost more than many people who ended up guillotined, imo).

And I don't even know how/why it happened! He started out okay - he had modest skills but seemed honest about the revolution. Then Bordeaux happened. Thermidor and months after were Jean-Lambert's five minutes of fame, but then it dissolved quickly, both in his professional and in private life.

The Quiberon Invasion mess in 1795 is one of the first examples, when he and Hoche (well, Tallien mostly because it was his orders) executed 750 royalists even after promising they'd be treated like prisoners of war. Yes, those were royalists who made an invasion on France so it's not surprising that they died, but 1) Hoche I think promised they'd be spared but Tallien ordered the execution, 2) Tallien was the one who ran his mouth so much after Thermidor about sparing people and now he executed in one day half of the number of people that were executed in the entire Great Terror, and 3) Seems like Tallien had some pro-royalist dealings/conversations with foreign powers (Spain mostly) and wanted to do a cover-up (? - will need to look into this further).

In his private life, Theresia wanted to leave him as early as 1796 and was reportedly banging Barras, but Tallien begged her to give him another chance. She said yes, and 9 months later she gave birth to a stillborn boy. We are not sure if the baby was Barras' or Tallien's.

Life in the Directoire was not great for Jean-Lambert and he was struggling with money, so he joined Napoleon's expedition to Egypt. It was horrible; he was miserable and suffered health problems. He wrote clingy letters to Theresia ("Care for our daughter and be faithful to me, my love!") (Spoiler: She was already on kid number two by the banker). The letters were intercepted by the enemy and read publicly. On his way from Egypt, Tallien was arrested and spent some time with the enemy but was released. Coming back from France must have been horrible, though, because Theresia asked for a divorce (and by the time it was done, she was already pregnant with banker's baby number 3). Because the kids were technically conceived while she was married to Tallien, they later successfully asked to have Tallien as their last name and were known as "Tallien bastards" in the family.

After, it was just a series of bad circumstances and decisions. Theresia remarried, to a Belgian prince, and we have a letter where Tallien begged her not to do that. Fouché tried to help him and found him a job in Alicante. But it was horrible because the whole town was infected by the Yellow Fever. Tallien contracted it and lost one eye. It is also possible that this is where he got leprosy (?)

When he got back to France, he was a ruin. He supported Napoleon in 1815, hoping to get some influence (I assume), but then Waterloo happened so another bad call for Jean-Lambert. He lived in poverty and only escaped banishment during the Bourbon restoration because of his poor health. He died at 53 of leprosy (at least wiki claims so - I could never verify it but we know he suffered poor health for years).

And on top of that - on top of that! - his magnum opus, his legacy, the thing that lives on for 200+ years, is not associated with him. Nobody knows of Jean-Lambert Tallien and his most crowning achievement: the invention of the Terror and evil mastermind Robespierre. Sure, he wasn't the only one involved in that, but he did play a crucial role and, arguably, it is the most historically important thing that he did. And nobody knows it was him! So many people hate Robespierre for 200+ years, but nobody knows who is responsible for forging that smear campaign. (Yes, I am aware that it's the point: if people knew it was constructed, and by specific people, they wouldn't view it in the same way, because the main thing about the Terror how it's seen is that it's an objective thing that happened just as described. But allow me this Tallien rant).

So.. yeah.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Before beginning this critique, as I have not finished reading the books, I would like to thank aedesluminis for the references she recommended. Without them, I wouldn't even have been able to place Madame de Stael. This is a personal opinion about her, so I allow myself some deviations that should not be present in a historical analysis. At the moment, my initial impression of her has proven to be justified. First of all, the two million livres that Necker advanced as collateral on his personal fortune. Personally, I wouldn't blame the Treasury for not repaying it because we must remember two things:

Necker amused himself with others in obstructing Turgot, who was much more competent than him. If Turgot had not proposed his austerity plan and had not played the "villain", Necker wouldn't have been able to borrow at all (I acknowledge the limitations of Turgot's economy, but I prefer the austerity plans advocated by Lindet and others at the time of 1793; however, Turgot was much more competent than Necker). Necker wanted this position at any cost, and now he must bear the consequences.

By constantly borrowing, playing the image of the false friend of the people denounced by Marat, and especially hiding the realities of the deficit, Necker would have done better to donate 2 million livres to try to redeem himself (even without these 2 million livres, his situation is much better than that of the vast majority of French people at that time). But let's get back to the subject of Germaine de Stael. As the daughter, she is a privileged witness of 1789. She becomes friends with people like Talleyrand and especially Lameth. She is attached to a moderate revolution of 1791 and does not like that the power of the King (executive) is diminished when he still has significant powers such as the right of veto. She suffers insults from the ultra-royalists, but she doesn't like the republicans much either. Contrary to some legends, Manon Roland is quite different from Madame de Stael. Moreover, the grinding of teeth that I would have against Stael is the fact that she approves of the shooting on the Champ de Mars while citizens were signing a petition for the deposition of the king following the flight to Varennes (thus a justified opinion) in the face of the lie of the National Assembly. With this phrase in 1793, "The Terror, he writes, was nothing but arbitrary pushed to the extreme." In her moral double standard, she will later approve of the repression of April 1, 1795, led by the army, the Muscadins. Not to mention the execution of the last Montagnards. Without any consideration for the economic context, namely the abolition of the maximum and the poor harvests of 1794 which pushed the last sans-culottes to rebel (even if I totally disapprove of the macabre assassination of Féraud), Madame de Stael approves once again. In conclusion, if it is republicans from the extreme left wing of 1791 - who were Girondins and some Montagnards -, Jacobins, Cordeliers or sans-culottes demanding repressive measures, they are awful arbitrary actions, but if it is the opposite camp, it can allow killings according to Germaine de Stael. These double standards should never be tolerated. I am exaggerating, but this is how I feel. The guillotine cannot be used against Madame Stael's friends but can be used against people like Charles Gilbert Romme according to her (I am exaggerating again, but you see where I am going with this).

Moreover, she quickly forgot Barras' role, which was one of the bloodiest of the revolution, to curry favor with him (hypocrisy or political calculation, I will be kind and grant her the second option). Furthermore, she who disapproved of the demonstration of April 1, 1795, by the sans-culottes or the petition demanded by the Cordeliers among others following the King's flight, will approve of a coup d'état which is an even more serious and unconstitutional act (because it comes from the army) on the part of Napoleon. Is she aware of her history? In the absence of following the predictions of a Marat, other Cordeliers, Jacobins, and others who believed that the army should never meddle in the affairs of the country, did she follow the excesses of the Janissaries in the Ottoman Empire? Or simply of Roman history? Quality education doesn't guarantee everything... And yes, Madame de Stael was initially a fervent admirer of Napoleon but later became his opponent due to authoritarian abuses. However, I am against in her biographies the fact of exonerating her from her mistake by saying that many people at the time admired Napoleon and supported the coup d'état. It's untrue; Kleber made a report against Napoleon (although he died before the 18th Brumaire), Prieur de la Marne was against Napoleon, Prieur de la Côte d'Or never accepted anything from Napoleon... So no, this excuse doesn't hold. Let's not forget that Germaine Stael made a dubious comparison between Robespierre and Napoleon; Robespierre surely had flaws but not that of being a dictator, and wouldn't sending armed force against the Convention unlike Napoleon. I acknowledge Madame de Stael for being anti-slavery and for having a good opinion of the consequences of the Hundred Days regarding Napoleon, but I must note that she did not suffer (at least not much) unlike other opponents of Napoleon, namely the Belair couple (Charles and Sanité Belair) who were executed, Jean-Baptiste Antoine le Franc (we must not forget that deportation could be worse than death), and even Simone Evrard who was interrogated (I think Napoleon and his governement wouldn't have arrested her too much time and even less deported her because even he would have realized that it would have been hell to pay if he did that against someone considered the widow of Marat) or even Marie Anne Babeuf watched by Napoleon's police and denounced, etc... But I will continue to read the books; I hope that thanks to these books, my opinion of her will evolve.

Source thank you again aedesluminis

Jean Denis Bredin Une singulière famille

Michel Winock Madame de Stael

Gislaine de Diesbach Madame de Stael

#frev#french revolution#madame de stael#napoleon#barras#romme charles gilbert#robespierre#necker#turgot

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

i had to reread Animal Farm this month for book group. it’s been almost ... fourteen years? since I first read it. coincidentally I also relatively recently read the first volume of Animal Castle by Xavier Dorison, back in November, which is a direct response to Animal Farm. returning to Farm as an adult and with that in the back of my mind made for a really, really interesting contrast.

first of all I simply love Animal Castle. it’s exquisite, one of the most beautiful animal fantasies I’ve seen illustrated in a long time. Felix Delep’s forms and gestures are so weighty, so fluid, & his designs evoke realism and character in equal measure, which is a hard line to walk in animal fantasy. every character is distinct and recognizable with resorting to caricature — an equally artful character design sensibility, but incorrect for the tone of this book. (can’t help but compare w/ Joe Sutphin’s recent graphic novel adaptation of Watership Down, which similarly wanted a realist sensibility and was genuinely a joy to read but suffered from all the bunnies looking the same, much like real bunnies.) and every panel is a treat to look at! Delep’s backgrounds are sooo detailed, the sense of place is really fantastic, not to mention his handling of light. pick this one up in hard copy if you can, it’s so worth seeing in person.

textually, storywise, it is equally excellent. Dorison is doing something different from Orwell: Farm is allegorical, a fable, which by necessity makes simplifications and operates with broad strokes, relying on archetype. Orwell is not particularly interested in the inner lives or personal relationships of any of the animals, which is fine for a fable. but I think it has a major failing, which is that basically all of Orwell’s working class characters areeeee... dead stupid. The working animals are, with the exception of Benjamin the donkey (who is cynical and apathetic), ignorant, illiterate, incapable of becoming literate, and without agency. This is even true of their descendants! (I do not think I am personally quite as pro-revolution as Jones Manoel, but I find his critique of Farm on this basis very compelling. This isn’t the only theme or moral you can pull from Animal Farm, but it is easy to read one of the main themes as “dictators are inevitable because regular people are stupid and gullible and cannot be educated,” which is ... I do not endorse this.)

Castle, on the other hand, is an entirely character-driven story. Miss B, our beloved Miss B, may not the smartest or strongest or best-positioned individual, but she has a will, she has a personality, she has opinions, she has family and friends and material interests and incentives, and Castle cares very much about all of these things. it also is far more interested in the small, mundane details of resistance against authoritarianism; no glorious revolution (yet? the story is still in progress & I need to read the first 3 issues of vol. 2, but I doubt it), but the small acts of rebellion and community building that are no less important. it is also, of course, very relevant that Dorison’s protagonist is a single mother. Dorison is interested in the ways women manage in authoritarian regimes — the hens whose reproductive labor is exploited are a much bigger part of the book, and the ewes (some of the sheep are ewes!) are not brainless sycophants but people who are realistically cowardly and reluctant to make waves, plus there are also rabbits in Castle and iirc they’re doing some sex work — and this also includes those who cozy up to the government. Orwell, known misogynist, very briefly mentions a female dog and a couple of sows, but only as vehicles to produce Napoleon’s guard dogs and more pigs; Dorison sketches out the ox dictator’s consort and the wife of the chief guard dog as minor but fully considered characters with concerns and incentives of their own.

Castle also has a much less hypercompetent authoritarian government. Metatextually, neither Napoleon nor Snowball are actually superhumanly competent compared to an average person, but the rest of the animals are so stupid that the bar for competence is on the floor. Castle knows & shows that dictators are not actually head and shoulders above working class people in terms of competence, only in terms of the amount of force they can bring to bear.

i don’t think Castle is necessarily strictly better than Farm, they have different concerns (Farm, by Orwell’s own admission, is much more immediately about revolutions failing, and Castle is more about existing under authoritarianism afterwards) and are also fully different forms (the allegorical novella vs. the serialized graphic novel), but... my edition of Farm (Signet Classics 1996) has a quote from the NYT on the back, reading, “A wise, compassionate, and illuminating fable for our times.” illuminating? yes. compassionate? no, I don’t think so. Orwell does sympathize with his characters (except Mollie, justice for Mollie) and wants you to sympathize as well (weren’t we all traumatized by Boxer’s death in high school?) but still, he is distinctly in contempt of the common man and women generally. I prefer Castle.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

General Soult and d’Espinchal in Spain

No, "general" is not a mistake, this snippet is mostly about Pierre Benoit, younger sibling of Marshal Soult, a soldier who spent most of his career under immediate orders of his brother, first as his aide-de-camp and later as his cavalry commander. While Joseph Bonaparte in his reports to Clarke and Napoleon was pretty vicious about Pierre’s military talents (or lack thereof), d’Espinchal who served in the cavalry under his command, seems to have esteemed him greatly.

In this case, the two of them took it upon them to try and save the life of a French émigré serving in the army of the Spanish insurgents. After the Armée du Midi had evacuated Andalusia and chased Wellington from Madrid and back to Portugal, Joseph had designated the region of Tolédo as their winter quarters. On 9 December 1812, a small detachment of the advance guard, under d’Espinchal’s command, surprised a Spanish outpost there and took a handful of prisoners, among them one officer.

And this officer seemed oddly familiar to d’Espinchal. As it turned out, he was the son of a French émigré who after the Revolution had found a new home at the Spanish court. The son had joined the Spanish army somewhat against his will, had even written letters to French officers in order to be allowed to return to France - but be that as it may, taken up arms against France he had.

On a sidenote, Frédéric Masson in the preface gushes about how very truthful and reliable d’Espinchal’s account is. At least in this incident I cannot agree, because the story d’Espinchal has the arrested officer "Alfred de M." tell about his life seems to be utter bullshit. But the author may have had reasons to conceal the real story and the true identity of the man. In the end it does not matter. What matters: He had a captured Frenchman at his hand who was guilty of fighting against his old fatherland.

Which would earn him the death penalty. Period.

The young man pleaded for his life, and begged d’Espinchal to do something for him if he could. D’Espinchal decided this was a little too hot for him on his own, and went to see his commanding general about the matter.

And, giving him a hundred francs for his first needs, I left him and went to see the general.

"So what's so interesting that you're leaving the outposts? You would be well and truly seized," he said to me, smiling, "if they were attacked."

"You know, my general," I replied, "that we have taken prisoner five dragoons and an officer; it is for the latter that I have come to claim your protection."

"Well then," he replied, "we are going to send them to France; you know very well that we only shoot brigands caught red-handed."

"I know that, General, but I am also aware that a French emigrant would suffer the same fate, and that is what I would like to avoid for my prisoner."

Then, recounting to him the life of this young man in the colours most likely to move his generous soul, supported above all by the letters he had written to General Grouchy and Count Lynch, I pleaded for his support.

"Devil! but this is becoming very romantic," he said; "I must absolutely report it to my brother, and I don't really know how it will turn out; anyhow, you are a clever fellow, in making me a confidant of so serious a fact. However, I'm going to write to the Marshal, and if he gets too worked up, we'll have your protégé escape. Please recommend to him the utmost silence on everything that concerns him; may he trust in my desire to please you and my intention not to allow a compatriot who has gone astray to perish miserably. Return to your outposts and guard us well."

What I dare already say, judging from this conversation alone, is that Pierre had a very different tone with his subordinates than his older brother. But with regards to his brother I specifically love the phrasing "s’il se fache trop", if he gets too upset about it. Obviously Pierre was not in doubt that Jean-de-dieu would indeed get his knickers in a twist, it was just a matter of degree.

And if Monsieur le Maréchal is not on board, we’ll just take care of this matter on our own.

As it turned out, Monsieur le Maréchal was on board. But when d’Espinchal received word of this, he had been wounded in yet another skirmish and was still lying in bed.

Eight days after these various events, General Soult arrived from Daymiel, with the 5th and 10th Chasseurs, to [...] carry out a strong reconnaissance, and honoured me with a visit. He found me still weak from the amount of blood I had lost, but with the hope of returning to duty soon. He told me that our young prisoner Alfred had inspired great interest in his brother, that he had left for France with a convoy, and that, according to all appearances, he would be employed on the staff of the Grande Armée, having formally declared that he would rather suffer the consequences of his position than bear arms against Spain. This dignified and honourable conduct and his energetic refusal, far from harming him in the mind of the Duke of Dalmatia, had determined the Duke, on the contrary, to grant him his protection.

Unfortunately, this seems to be the end of Alfred’s story, I could not find any further reference.

#napoleon's marshals#jean-de-dieu soult#napoleon's generals#pierre benoit soult#hippolyte d'espinchal#peninsular war#spain 1812

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Amidst the unforeseen difficulties, beautiful memories shine Takarazuka Flower Troupe performance "Years of Pilgrimage~The Wandering Soul of Franz Liszt" "Fashionable Empire"

(Just relocating an old translation I did over here)

Source:Enbu

Flower Troupe performance: Musical “Years of Pilgrimage~ The Wandering Soul of Franz Liszt” Show Groove “Fahsionable Empire led by Yuzuka Rei will embrace Senshuuraku on September 4 in the Tokyo Takarazuka Theatre performance.

Musical “Years of Pilgrimage~ The Wandering Soul of Franz Liszt” talks about the “Piano Magician”, pianist Franz Liszt who accumulates the immense popularity in the early 19th century Europe. This is a original production written by Ikuta Hirokazu on his dynamic life. Starting with the protagonist Liszt, he boldly recreates a musical based on the lives of the artistes who were also born in the same era.

【STORY】

1832, Paris.

France was in a long turmoil of revolution, terror politics, the first monarchy of Napoleon, a reinstatement in monarchy after his fall, and the July revolution. It was dominated by the aristocrats that held power and the bourgeoisie.

Among these Parisian socialites, there is a pianist that drives the women fervent. His name is Franz Liszt (Yuzuka Rei). With extraordinary beauty, he hurls the Parisian salons by storm with his superior techniques, and his popularity is now at the peak. But, the more this star performer is enjoying these compliments, the farther his music is going astray from the original path. Similarly a pianist and composer Frederick Chopin (Minami Maito) shows Liszt a critique commentary on his recital. The criticisms, under the pseudonym of Daniel Stern, writes against the norm of praising Liszt’s performance, but records how (Liszt) lives and betrays his soul, thus feeling this “Sorrow of the Arlequin”.

Unconsciously avoiding these, and by identifying how his heart suffers from this discrepancy and gap between his introspective music and this artificial image of star performer as “Franz Liszt”, Liszt recalls his days of anguish from childhood times till now. He was expected as a talent in music in his homeland Hungary, and he went to Vienna with his father, and travelled to Paris. But his standalone talent in his homeland could not overpower others in this city of music. Then, because of this great setback, his father passed away bitterly, leaving Liszt alone. To live as an artiste embraced by the aristocratic society, he never stopped honing himself until he is Favourite of the Times.

Why can (Daniel Stern) see this emptiness that he was never able to admit to? The one who criticizes Liszt is Daniel Stern, the wife of Count D’Agoult (Hiryuu Tsukasa), Countess Marie d’Agoult (Hoshikaze Madoka). To find out more about her, he followed her closely to her mansion.

At first, Marie is puzzled by Liszt’s sudden visit, but she cut ties with her cold husband and wants to live her own life. She wants to give up the aristocratic society’s way of thinking and pursue her meaning in life under a male pseudonym to find her own style. “When I realize my heart is mirroring to yours, I’m actually speaking what my heart says.” Liszt truly believes that for the first time he meets a woman that they share empathy, so he elopes with Marie in order to find his true self again. They go far away from Paris to Geneva in Switzerland, creating and winding a music of his own, his “Years of Pilgrimage”, not to be performed to anyone else. But, the female author who wears man’s clothing and is in good terms with Liszt, George Sand (Towaki Sea), together with Chopin and the artistes from the beginning, go after Liszt and the gears of Fate begins to turn again…

Heralded as the “Piano Magician” is the pianist, composer, maestro and music teacher Franz Liszt, his life was full of vibrant colours and many stories. On one hand, apart from Liszt being the “piano virtuouso” (with extraordinary technique”, he was also a debonair man and he had the popularity of celebrity if we speak in modern terms – his charisma overflowing, charming many women. on the other hand, he established a music institute in hungary and later concentrated his time to teach many amaters students. In terms of piano, he was very enthusiastically advocating the development of piano. He started holding charity recitals for places plagued by natural disasters. He used his best efforts to create his first opera premiere, despite the dim achievements accomplished on the night. He made precedence as a “music ambassador” in european history and continued to do so in his latter life, despite the surprise that it was seldom discussed.

Perhaps that is the reason affecting this “Years of Pilgrimage – The Wandering Soul of Franz Liszt” performance. Ikuta began the story with a key point which started from the surprising relationship between him and George Sand, then we see how he enjoyed the fame in his star performances, how he encountered Countess Marie d’Agoult, and how they held hands to step forward on this pilgrimage to pursue their wandering soul. This is a fast-paced musical that you would not be bored.

But the setting of this production is perhaps when Sand is jealous and starts challenging and provoking Liszt, that he leaves Marie to once again be the star performer, and because he later starts aligning himself parallel to the aristocrats. It’s really difficult to build this storyline up. In particular, Liszt has the complexity of living as an artiste but also embracing himself to be demanded by the aristocrats. He’s so insistent in getting an aristocratic title, but because he leaves Marie alone, who also was an aristocrat, from intense start to the last, she joins the June Riots that tears down and destroys the aristocratic society. Yet, it’s painful having things progress too fast.

Of course Ikuta also knew about that, he tried making use of this spiritual world of dreams that doesn’t specify time and space, and he also said this in the author’s note in the programme, that he attempted creating an encounter of Liszt, Chopin and Sand that didn’t happen in reality. I fully understand that. But the question is not to think whether Ikuta has failed writing historical figures faithfully in his bold direction. There’s no one alive during that time who knows about these things. What remains is the truth from the various documents, it’s not difficult to determine which are false. But because of that, it’s not about adding the fictional elements, but about how should the charms of the protagonist be depicted?

This is because the stage of Takarazuka Revue productions is the only stage that still cherish the noble traditions of preserving the “Star Acting” (i.e. focusing on the protagonist). Of course the protagonist can still be tattered, or foolish. Sometimes, he can be selfish or arrogant. But in the ends of his life, he should try and preserve what he can achieve, be it the smallest fragment, of something beautiful, inside his heart, in his hands. In the production however, it’s a pity to see this process being rushed through. Simply said, rather than putting it as Liszt having a “a soul exuding distorted rays”, he continues to actively state that this is a modern Liszt. Current leading Japanese pianist Kaneko Miyuji also said the same in the performance programme interview that he was dazzled by this image of Liszt and for an author/director of Takarazuka Revue, the core theme is what he definitely wants to thinks about again. In these continuing difficult times, as Takarazuka Revue reaches its landmark of 110th anniversary, Ikuta Hirokazu is definitely a creator that bears great expectations.

But…the regrettable part is there’s some distorted balance in this production, yet Yuzuka Rei has the ability to turn it back right. I only have admiration for that. Thinking again how difficult it is to carry that golden hairstyle but Yuzuka totally made it like her own when she acts as Liszt. The shining parts in dancing as a trickster (note: should be about S13 when Liszt dances to Hungarian Rhapsody in the acoladement ceremony) and the process of meeting with the destined love are given, but even for those confused, jealous, how she’s sometimes madly drown in ambition, how she proudly dances and turns, I’d say I’m nothing but surprised for how beautiful all these reflected (in her performances). It’s really Yuzuka’s strength to be capable both the deep acting and also the perfect visual. I want to thank her for being this leading role as Liszt portrayed in “Years of Pilgrimage”. Seeing how great of a star she is becoming, I will be amazed by the infinite possibilities of Yuzuka.

Becoming as Yuzuka’s partner, Hoshikaze has become even more radiant and she plays a difficult role clearly by adding a core spirit into it. Thanks to Hoshikaze’s cultivation in her (Takarazuka) career, she makes it possible to act as a countess that’s troubled by self-actualisation and because of how happy it was in the scene where she was playing hide-and-seek with Liszt in their white costumes, that her solo really cuts through when she sings about “Why Have You Let Go of My Hand” as Liszt leaves her. As mentioned above about a rushed through process, even in the last scene, because of this vibe created by the Top Combi between Yuzuka and Hoshikaze, it’s great respect to see how time has passed, reflected in Hoshikaze’s expressions.

“Piano Poet” Frederick Chopin, played by Minami Maito, specialised and only demonstrated his talent in piano pieces, such as Chopin’s “12 Etudes, Op.10”. This was a set of piano suits that Liszt couldn’t play at first glance…with that story, Liszt met this talent which he couldn’t surpass in his life. Responding to Chopin’s position in the musical, who was Liszt’s great friend and also rival, (Minami) creates a Chopin image in new frontiers, with someone that’s easygoing and calm and also he who can see the truth. Speaking of Minami, the first that comes to mind is her specialty in dancing ability. With that sealed away and focusing as a silent flame (of stimulation in this performance) is a great source of inspiration to Minami in the future.

Towaki Sea plays George Sand, Chopin’s lover and as we already know, a female author that wears man’s clothing. She acts as the role responsible for the key passion in the production. Although I was shocked by the lover relationship she had with Liszt from the star, this later became a great driving force which made me want to watch more of the complicated relationships with Liszt, Marie, Chopin and Sand. It’s natural for her to act as a woman, her transition from low to high vocals in singing are seamless so I was surprisngly pleased about that. I feel like this is another person with great strength and glamour.

Also, while deciding among his companions, which artists, friends, journalists should be featured, because there are so many historic figures, Takarazuka considered protecting its theory. Such as the chief editors in the news publishing company Emile de Jiradin, played by Seino Asuka, is a role that is both friends with Marie, the anonymous writer and the female author, Sand. He’s a fighter committed to eradicating the wealth disparity after the revolution. In “Paris in the Winter Fog”, we can trust in and rely on her to continue that strength as a strong-minded otokoyaku. His wife Delphine is played by Hoshizora Misaki. Even though she’s not always on stage apart from ensemble scenes, Hoshizora stands out with her radiance, I feel like she’s gone through great improvement. The little acting scene between these two without any lines is also interesting. Rossini, played by Ichinose Kouki, who wrote many operas such as “The Barber in Seville” and “William Tell”. In this musical, Miyahime Koko plays as his fiancee Olympe and you can really enjoy their nice atmosphere and how happy of a couple they can be. Among these members is the literary giant Victor Hugo, the author of “Les Miserables”, is surprisingly played by Flower Troupe’s former kumichou Takashou Mizuki. Adding a little tenderness into the atmosphere, it’s definitely more interesting to add some colour into this gathering of artistes. Kazumi Shou who plays as commentator Saint-Beuve, Serina Ei who plays as novelist Balzac (Note: The article mistakenly wrote Balzac as a “painter”), Yuki Daiya who plays as painter Delacroix, Kinami Raito who plays as composer Berlioz and more, it’s really amazing to see only these characters combined together, a great assembly of these ever glorious artistes. On the other hand, there is Marquise le Vayer played by Mikaze Maira, the landmark figure of the socialites renowned in hosting events. Liszt’s father in the throwback scene, played by Wataru Hibiki. Boy Liszt played by Misora Maru really stands out. Liszt’s mother played by Haruhi Urara. Patroness Countess Esterhazy played by Kaga Ririka and more. I hope you would cherish these beautiful musumeyaku that succeeds the tradition of “Hanamusume”. Among those, Marie’s maid Adele Ryusand, played by Mihane Ai, her devotion of love is really adorably portrayed.

Also, deciding on graduating in this musical is Oto Kurisu who plays Countess Laprunaréde, she presented herself as Liszt’s patroness and a strong essentialist in the Parisian socialites and it’s wonderful seeing how she affirmedly establishes this acting spirit as a role to be disliked. Even with the great support from Senka, she still created a role that wasn’t strange at all. It’s a pity for Oto to graduate in this year/ken. The same could be said for Hiryuu Tsukasa who plays as Count d’Agoult. It’s very normal for a male aristocrat to have lovers, but she really showed frustration when his wife (Marie) retorts against him and the mature feeling of trying to listen to others. She has been a newcomers’ performance lead role (Note: Yamataikoku), recently in “Ginchan’s love” acting as Yasu was her first time going beyond the pureness of the “handsome roles” (二枚目) and showing a dynamic acting ability. Once again, it’s quite a pity to graduate from here. I want to applaud for their unique characters and their important strength given to Flower Troupe.

Continuing from this musical is Show Groove “Fashionable Empire” written by Inaba Daichi. The stage of an Empire where all the top-notch fashionistas gather, with Yuzuka’s Emperor as the centre, this is an interesting show that shows various sides of an empire. Starting with modern outfits from the stars, sometimes cool, sometimes hot, there are various scenes connected little by little to create this good composition. The movement of equipment and change of clothings is also very efficient and quick.

Among those, with Yuzuka Rei at the start, to Hoshikaze, Minami, Towaki and Seino that play a great role in Flower Troupe in the important scenes, there’s also stylish scenes that have all of Flower Troupe which adds vibrant colours (to the show) without difficulty. Especially Yuzuka’s specialty is really allowing you feel her freedom and passion in many ways, that every one from Flower Troupe is certainly breathing from that, no matter which scene it is from the farmost ends, you can feel the full release of energy from all these members. Their wonderful smiles is when “Ah, that’s the place where the audience would directly feel their appeal” and so on. It’s such a show with so much dancing, I feel if my eyes aren’t sufficient to take it all in. Such as Minami in a dashing suit, coupled with Hozumi with an onnayaku image. “Is this a continuation of her female role in the musical” when I look at Towaki in a dress, which in a breath, transformed into an otokoyaku; besides her female role accent is pretty good for an otokoyaku playing as one. Hiryuu (Tsukasa) has a dark, passionate and deep otokoyaku image; Oto (Kurisu)’s soprano; Serina (Ei)’s coquettish charm. Wakakusa (Moeka)’s amazing vocals as an Etoile - I was also looking over the graduates.

Rather than Top Combi Yuzuka and Hoshikaze dancing, it’s much more than just a dance, it’s really fresh to see this duet dance becoming like a conversation in acting. This is a show that there are many various scenes from the opening, that you’d feel so many features all at once.

Besides, Kōhei Ueguchi is the first time producing the choreography for this musical, also a musical actor himself. The effect of this innovative feeling goes back to the connections Ikuta cultivated while he was still working on “Don Juan”. How much higher heights can this musical achieve if it was given more days to be performed? Above all, when I think of the graduating members, it hurts not able to fight anyone or anywere against this regret that no one could avoid. All of these feelings from the cast, the orchestra, the staff and from the audiences are indescribable. But because of that, in this unforeseen difficulties, that the memories of these shining moments on stage will never be forgotten. Even though for instance we cannot feel the same space altogether, through the livestreams, there are still feelings engraved from the people who delivered their feelings from afar. One day this day will come. I can’t laugh now, but I can say that this day will come. I think about this believing that we can embrace Senshuuraku. When people who love Takarazuka continue to believe, a dawn of hope will surely arrive.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

M. Myriel

Volume 1: Fantine; Book 1: A Just Man; Chapter 1: M. Myriel

In 1815, M. Charles-François-Bienvenu Myriel was Bishop of Digne. He was an old man of about seventy-five years of age; he had occupied the see of Digne since 1806.

Although this detail has no connection whatever with the real substance of what we are about to relate, it will not be superfluous, if merely for the sake of exactness in all points, to mention here the various rumors and remarks which had been in circulation about him from the very moment when he arrived in the diocese. True or false, that which is said of men often occupies as important a place in their lives, and above all in their destinies, as that which they do. M. Myriel was the son of a councillor of the Parliament of Aix; hence he belonged to the nobility of the bar. It was said that his father, destining him to be the heir of his own post, had married him at a very early age, eighteen or twenty, in accordance with a custom which is rather widely prevalent in parliamentary families. In spite of this marriage, however, it was said that Charles Myriel created a great deal of talk. He was well formed, though rather short in stature, elegant, graceful, intelligent; the whole of the first portion of his life had been devoted to the world and to gallantry.

The Revolution came; events succeeded each other with precipitation; the parliamentary families, decimated, pursued, hunted down, were dispersed. M. Charles Myriel emigrated to Italy at the very beginning of the Revolution. There his wife died of a malady of the chest, from which she had long suffered. He had no children. What took place next in the fate of M. Myriel? The ruin of the French society of the olden days, the fall of his own family, the tragic spectacles of ’93, which were, perhaps, even more alarming to the emigrants who viewed them from a distance, with the magnifying powers of terror,—did these cause the ideas of renunciation and solitude to germinate in him? Was he, in the midst of these distractions, these affections which absorbed his life, suddenly smitten with one of those mysterious and terrible blows which sometimes overwhelm, by striking to his heart, a man whom public catastrophes would not shake, by striking at his existence and his fortune? No one could have told: all that was known was, that when he returned from Italy he was a priest.

In 1804, M. Myriel was the Curé of Brignolles. He was already advanced in years, and lived in a very retired manner.

About the epoch of the coronation, some petty affair connected with his curacy—just what, is not precisely known—took him to Paris. Among other powerful persons to whom he went to solicit aid for his parishioners was M. le Cardinal Fesch. One day, when the Emperor had come to visit his uncle, the worthy Curé, who was waiting in the anteroom, found himself present when His Majesty passed. Napoleon, on finding himself observed with a certain curiosity by this old man, turned round and said abruptly:—

“Who is this good man who is staring at me?”

“Sire,” said M. Myriel, “you are looking at a good man, and I at a great man. Each of us can profit by it.”

That very evening, the Emperor asked the Cardinal the name of the Curé, and some time afterwards M. Myriel was utterly astonished to learn that he had been appointed Bishop of Digne.

What truth was there, after all, in the stories which were invented as to the early portion of M. Myriel’s life? No one knew. Very few families had been acquainted with the Myriel family before the Revolution.

M. Myriel had to undergo the fate of every newcomer in a little town, where there are many mouths which talk, and very few heads which think. He was obliged to undergo it although he was a bishop, and because he was a bishop. But after all, the rumors with which his name was connected were rumors only,—noise, sayings, words; less than words—palabres, as the energetic language of the South expresses it.

However that may be, after nine years of episcopal power and of residence in Digne, all the stories and subjects of conversation which engross petty towns and petty people at the outset had fallen into profound oblivion. No one would have dared to mention them; no one would have dared to recall them.

M. Myriel had arrived at Digne accompanied by an elderly spinster, Mademoiselle Baptistine, who was his sister, and ten years his junior.

Their only domestic was a female servant of the same age as Mademoiselle Baptistine, and named Madame Magloire, who, after having been the servant of M. le Curé, now assumed the double title of maid to Mademoiselle and housekeeper to Monseigneur.

Mademoiselle Baptistine was a long, pale, thin, gentle creature; she realized the ideal expressed by the word “respectable”; for it seems that a woman must needs be a mother in order to be venerable. She had never been pretty; her whole life, which had been nothing but a succession of holy deeds, had finally conferred upon her a sort of pallor and transparency; and as she advanced in years she had acquired what may be called the beauty of goodness. What had been leanness in her youth had become transparency in her maturity; and this diaphaneity allowed the angel to be seen. She was a soul rather than a virgin. Her person seemed made of a shadow; there was hardly sufficient body to provide for sex; a little matter enclosing a light; large eyes forever drooping;—a mere pretext for a soul’s remaining on the earth.

Madame Magloire was a little, fat, white old woman, corpulent and bustling; always out of breath,—in the first place, because of her activity, and in the next, because of her asthma.

On his arrival, M. Myriel was installed in the episcopal palace with the honors required by the Imperial decrees, which class a bishop immediately after a major-general. The mayor and the president paid the first call on him, and he, in turn, paid the first call on the general and the prefect.

The installation over, the town waited to see its bishop at work.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The comeback

The next day, after the human visiting the farm, the vision about the pigs for the human was completely changed. Now, they were treated like real neighborhoods, not just animals that do not think. The relationship between them was every day stronger, and this resulted in a bigger repression on the other animals.

With all of this happening, Mr.Jones saw the opportunity to get back to the farm. The pigs, very excited with this, accepted him to stay. Squealer's told the animals that Mr.Jones had changed, and would never do the things he used to do again. When he used to do this, it was because he was drunk, and didn’t mean to do it. After all, two legs it’s better than four.

In the first month, the pigs and Mr. Jones were sleeping in the house, while the animals were staying in the stable, as always. Every night, the animals could hear the pigs and Mr. Jones was very happy with their lives, drinking and eating until they couldn't anymore. For them, there was no problem in what was going on. As for the animals… The confidence wasn’t strong, and they were always doubting the decisions made by the man and his henchmen.

Every day, a different thing happened. The missing of some animals became very frequent. At first, it was just the eggs of the hen, and also the milk of the cow, but that always happened. But now, with Mr.Jones in the cockpit, it was not just eggs and milks, but now the cows and the hens too. Every night, one of the animals disappears, but in the morning, they gave more and more food for breakfast, so we were getting stronger. But, without the pigs, it was impossible to make a revolution.

They were blind with the situation, they were just a little bothered with the animals leaving and not coming back. Clover, the only one that was really worried, had an idea that would help everybody. He sent a delivery card to Snowball, who was expelled from the farm by Napoleon. The letter was a help message, saying that they were in dangerous in Mr.Jones hands, and if nobody help them, they would be sold to some place and Mr. Jones would get the money to buy foods and beers, as he already did before.

Days had passed, and nothing of Snowball. More animals were starting to disappear. Some of the animals, like Clover, were suffering a lot with the situation. Otherwise, the other ones, like sheep, were very happy with this model, for receiving more food. Clover tried to warn them about what was going on in the farm, but they didn’t care.

The message sent to Snowball was extremely secret. But inside the animals, one of the sheeps, told Napoleon that Clover was against the population, and was planning a revolution. The message arrived to Snowball, but arrived to Napoleon as well. With this information in hand, the pigs and Mr Jones decided to sell Clover to another farm, and in his speech, Squealer said that Clover ran away from the farm.

The despair took the farm, and like an angel, Snowball appeared hired in the stable. Some animals celebrated a lot, but very quiet to not wake up the pigs an Mr. Jones. Snowball told the animals everything he knew, and also told all the secrets about Napoleon. So, the whole night, they were planning how to get back to power, and obviously, Snowball, the smarter, was the leader.

The plan was simple: steal the weapons, tie them all up, have their hands out of the throne, and throw them out of the farm. In the morning they were all set up and aware, just the sheeps didn’t know because Snowball couldn’t convince them.

When the night came, the animals prepared to execute the plan, while Mr Jones and the pigs were sleeping in the house, Snowball and the other animals snitched in and started to tie them up. They did that very carefully and because they were drunk none of them really woke up. While they were putting them out, the pigs and Mr Jones woke up, without any option in that situation. They tried to convince the animals that it was all a huge mistake, but the animals continued the plan anyway, throwing them out of the farm to regain the traditional Animal Farm and the daily bases. The happiness was back in the farm, and together, they brought back equality.

0 notes

Text

The Farm Runner

Synopsis: What if animal farm was a prison that everyone thought was a safe place, however, all of them who entered it had their memories erased and did not receive information of the outside World. If an unexpected situation happened which one of the animals found a way out to save everyone's freedom.

Fan Fiction text:

And everything faded to black.

I knew the pain was spreading through my entire body and the last memory I had was me leaving the farm, when someone called my name: “Mollie”. I remember all the years I spent in this place and the feeling of anguish invades my mind. I never thought one of my “comrades” could do this to us.

Now that I'm on the outside world my only goal is to get my family out of there, but for that to be possible I need to understand my past first. I have no memory of my life before arriving at the farm, as no one who entered could know what was going on outside that place. We didn't know what was happening outside, and I used to think I was free until I discovered everything.

Before that we used to live in harmony, each one of us had our functions. We worked long hours to get the least amount of food. However, the division of production was uneven, but no animal would dare to question Napoleon's command, and it is only now that I realize how manipulated we were. Some of us suffered the results of this, many ended up dead. The last one we lost was Boxer, the horse who worked harder than any other animal on the farm.

I wonder how this change happened so fast. A moment before I was still in this prison and then I was out here, thinking about what would really happen after my release. I wanted to try to warn them, to get them out of a place where I hardly knew why they were working. I learned that some of my species were no longer the same, I couldn't tell humans from pigs, and that just annoys me. I left there due to that, I ran away as soon as possible, however, that wasn't as good as I expected. I was alone in a place that had a minimal amount of knowledge, with people that until then, I considered my home. However, that ended up changing, the moment I realized that they were starting to persecute me for not supporting such injustice. I was judged, dumped and even known for wanting my existence to be annihilated.

The moment I was looking for my ribbons and accidentally found that passage that pointed to my salvation, I felt terrified of abandoning my new life. However, the thought of being able to regain all the privileges that we wanted to achieve in our first revolution spoke louder in my mind. It was at this moment that I made my decision to act, I fled without even looking back.

What shocks me the most is that my “comrades” went after me. Not because they miss me, but because I discovered the truth about their totalitarian thinking.When I was resting under a tree, in the middle of the forest, I heard them coming after me. And a feeling of anguish was replaced by something even worse, anger. But luckily they didn't find me. This only showed me that I had to help the helpless out of that place. I started to make plans to communicate with the people inside, I tried to send crows to pass a message to my colleagues, but I only discovered that this would not be possible, as the new Animal Farm system did not allow this communication.

And here at this moment I find myself, going to look for a new way to warn my comrades, a way to tell them the great risk they are in. Many of us don't even remember how we used to live our lives with Mr. Jones. Surely it wasn't in surprising conditions, but nowadays it has become much worse. We receive less food and work harder than at that time.

But something so unexpected happens, I thought I was hallucinating, that could never be true. He was dead, he had to be dead. I saw the truck taking him to its final destination. Only if… no, Boxer wouldn't do that, he worked hard, but he was there in the present and now. And those eyes eventually found mine. I watched my entire life pass before his gaze as he held an unfamiliar object towards me, and with just a bang, a single thought came to my mind. Truth does not bring you power, it only attracts death.

0 notes

Text

Anonymous asked: I enjoyed reading your posts about Napoleon’s death and it’s quite timely given its the 200th anniversary of his death this year in May. I was wondering, because you know a lot about military history (your served right? That’s cool to fly combat helicopters) and you live in France but aren’t French, what your take was on Napoleon and how do the French view him? Do they hail him as a hero or do they like others see him like a Hitler or a Stalin? Do you see him as a hero or a villain of history?

5 May 1821 was a memorable date because Napoleon, one of the most iconic figures in world history, died while in bitter exile on a remote island in the South Atlantic Ocean. Napoleon Bonaparte, as you know rose from obscure soldier to a kind of new Caesar, and yet he remains a uniquely controversial figure to this day especially in France. You raise interesting questions about Napoleon and his legacy. If I may reframe your questions in another way. Should we think of him as a flawed but essentially heroic visionary who changed Europe for the better? Or was he simply a military dictator, whose cult of personality and lust for power set a template for the likes of Hitler?

However one chooses to answer this question can we just - to get this out of the way - simply and definitively say that Napoleon was not Hitler. Not even close. No offence intended to you but this is just dumb ahistorical thinking and it’s a lazy lie. This comparison was made by some in the horrid aftermath of the Second World War but only held little currency for only a short time thereafter. Obviously that view didn’t exist before Hitler in the 19th Century and these days I don’t know any serious historian who takes that comparison seriously.

I confess I don’t have a definitive answer if he was a hero or a villain one way or the other because Napoleon has really left a very complicated legacy. It really depends on where you’re coming from.

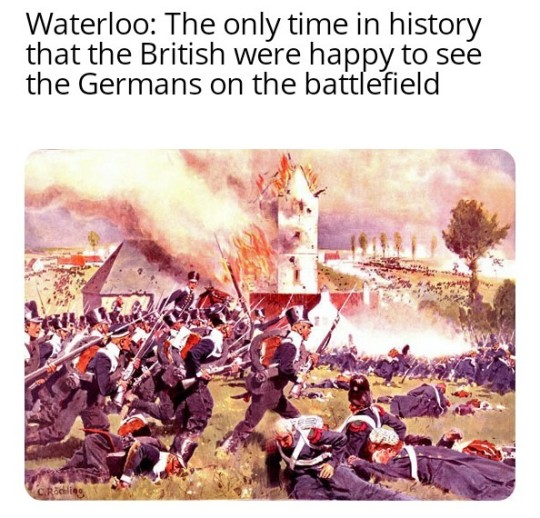

As a staunch Brit I do take pride in Britain’s victorious war against Napoleonic France - and in a good natured way rubbing it in the noses of French friends at every opportunity I get because it’s in our cultural DNA and it’s bloody good fun (why else would we make Waterloo train station the London terminus of the Eurostar international rail service from its opening in 1994? Or why hang a huge gilded portrait of the Duke of Wellington as the first thing that greets any visitor to the residence of the British ambassador at the British Embassy?). On a personal level I take special pride in knowing my family ancestors did their bit on the battlefield to fight against Napoleon during those tumultuous times. However, as an ex-combat veteran who studied Napoleonic warfare with fan girl enthusiasm, I have huge respect for Napoleon as a brilliant military commander. And to makes things more weird, as a Francophile resident of who loves living and working in France (and my partner is French) I have a grudging but growing regard for Napoleon’s political and cultural legacy, especially when I consider the current dross of political mediocrity on both the political left and the right. So for me it’s a complicated issue how I feel about Napoleon, the man, the soldier, and the political leader.

If it’s not so straightforward for me to answer the for/against Napoleon question then it It’s especially true for the French, who even after 200 years, still have fiercely divided opinions about Napoleon and his legacy - but intriguingly, not always in clear cut ways.

I only have to think about my French neighbours in my apartment building to see how divisive Napoleon the man and his legacy is. Over the past year or so of the Covid lockdown we’ve all gotten to know each other better and we help each other. Over the Covid year we’ve gathered in the inner courtyard for a buffet and just lifted each other spirits up.

One of my neighbours, a crusty old ex-general in the army who has an enviable collection of military history books that I steal, liberate, borrow, often discuss military figures in history like Napoleon over our regular games of chess and a glass of wine. He is from very old aristocracy of the ancien regime and whose family suffered at the hands of ‘madame guillotine’ during the French Revolution. They lost everything. He has mixed emotions about Napoleon himself as an old fashioned monarchist. As a military man he naturally admires the man and the military genius but he despises the secularisation that the French Revolution ushered in as well as the rise of the haute bourgeois as middle managers and bureaucrats by the displacement of the aristocracy.

Another retired widowed neighbour I am close to, and with whom I cook with often and discuss art, is an active arts patron and ex-art gallery owner from a very wealthy family that came from the new Napoleonic aristocracy - ie the aristocracy of the Napoleonic era that Napoleon put in place - but she is dismissive of such titles and baubles. She’s a staunch Republican but is happy to concede she is grateful for Napoleon in bringing order out of chaos. She recognises her own ambivalence when she says she dislikes him for reintroducing slavery in the French colonies but also praises him for firmly supporting Paris’s famed Comédie-Française of which she was a past patron.

Another French neighbour, a senior civil servant in the Elysée, is quite dismissive of Napoleon as a war monger but is grudgingly grateful for civil institutions and schools that Napoleon established and which remain in place today.

My other neighbours - whether they be French families or foreign expats like myself - have similarly divisive and complicated attitudes towards Napoleon.

In 2010 an opinion poll in France asked who was the most important man in French history. Napoleon came second, behind General Charles de Gaulle, who led France from exile during the German occupation in World War II and served as a postwar president.

The split in French opinion is closely mirrored in political circles. The divide is generally down political party lines. On the left, there's the 'black legend' of Bonaparte as an ogre. On the right, there is the 'golden legend' of a strong leader who created durable institutions.

Jacques-Olivier Boudon, a history professor at Paris-Sorbonne University and president of the Napoléon Institute, once explained at a talk I attended that French public opinion has always remained deeply divided over Napoleon, with, on the one hand, those who admire the great man, the conqueror, the military leader and, on the other, those who see him as a bloodthirsty tyrant, the gravedigger of the revolution. Politicians in France, Boudon observed, rarely refer to Napoleon for fear of being accused of authoritarian temptations, or not being good Republicans.

On the left-wing of French politics, former prime minister Lionel Jospin penned a controversial best selling book entitled “the Napoleonic Evil” in which he accused the emperor of “perverting the ideas of the Revolution” and imposing “a form of extreme domination”, “despotism” and “a police state” on the French people. He wrote Napoleon was "an obvious failure" - bad for France and the rest of Europe. When he was booted out into final exile, France was isolated, beaten, occupied, dominated, hated and smaller than before. What's more, Napoleon smothered the forces of emancipation awakened by the French and American revolutions and enabled the survival and restoration of monarchies. Some of the legacies with which Napoleon is credited, including the Civil Code, the comprehensive legal system replacing a hodgepodge of feudal laws, were proposed during the revolution, Jospin argued, though he acknowledges that Napoleon actually delivered them, but up to a point, "He guaranteed some principles of the revolution and, at the same time, changed its course, finished it and betrayed it," For instance, Napoleon reintroduced slavery in French colonies, revived a system that allowed the rich to dodge conscription in the military and did nothing to advance gender equality.

At the other end of the spectrum have been former right-wing prime minister Dominique de Villepin, an aristocrat who was once fancied as a future President, a passionate collector of Napoleonic memorabilia, and author of several works on the subject. As a Napoleonic enthusiast he tells a different story. Napoleon was a saviour of France. If there had been no Napoleon, the Republic would not have survived. Advocates like de Villepin point to Napoleon’s undoubted achievements: the Civil Code, the Council of State, the Bank of France, the National Audit office, a centralised and coherent administrative system, lycées, universities, centres of advanced learning known as école normale, chambers of commerce, the metric system, and an honours system based on merit (which France has to this day). He restored the Catholic faith as the state faith but allowed for the freedom of religion for other faiths including Protestantism and Judaism. These were ambitions unachieved during the chaos of the revolution. As it is, these Napoleonic institutions continue to function and underpin French society. Indeed, many were copied in countries conquered by Napoleon, such as Italy, Germany and Poland, and laid the foundations for the modern state.

Back in 2014, French politicians and institutions in particular were nervous in marking the 200th anniversary of Napoleon's exile. My neighbours and other French friends remember that the commemorations centred around the Chateau de Fontainebleau, the traditional home of the kings of France and was the scene where Napoleon said farewell to the Old Guard in the "White Horse Courtyard" (la cour du Cheval Blanc) at the Palace of Fontainebleau. (The courtyard has since been renamed the "Courtyard of Goodbyes".) By all accounts the occasion was very moving. The 1814 Treaty of Fontainebleau stripped Napoleon of his powers (but not his title as Emperor of the French) and sent him into exile on Elba. The cost of the Fontainebleau "farewell" and scores of related events over those three weekends was shouldered not by the central government in Paris but by the local château, a historic monument and UNESCO World Heritage site, and the town of Fontainebleau.

While the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution that toppled the monarchy and delivered thousands to death by guillotine was officially celebrated in 1989, Napoleonic anniversaries are neither officially marked nor celebrated. For example, over a decade ago, the president and prime minister - at the time, Jacques Chirac and Dominque de Villepin - boycotted a ceremony marking the 200th anniversary of the battle of Austerlitz, Napoleon's greatest military victory. Both men were known admirers of Napoleon and yet political calculation and optics (as media spin doctors say) stopped them from fully honouring Napoleon’s crowning military glory.

Optics is everything. The division of opinion in France is perhaps best reflected in the fact that, in a city not shy of naming squares and streets after historical figures, there is not a single “Boulevard Napoleon” or “Place Napoleon” in Paris. On the streets of Paris, there are just two statues of Napoleon. One stands beneath the clock tower at Les Invalides (a military hospital), the other atop a column in the Place Vendôme. Napoleon's red marble tomb, in a crypt under the Invalides dome, is magnificent, perhaps because his remains were interred there during France's Second Empire, when his nephew, Napoleon III, was on the throne.

There are no squares, nor places, nor boulevards named for Napoleon but as far as I know there is one narrow street, the rue Bonaparte, running from the Luxembourg Gardens to the River Seine in the old Latin Quarter. And, that, too, is thanks to Napoleon III. For many, and I include myself, it’s a poor return by the city to the man who commissioned some of its most famous monuments, including the Arc de Triomphe and the Pont des Arts over the River Seine.

It's almost as if Napoleon Bonaparte is not part of the national story.

How Napoleon fits into that national story is something historians, French and non-French, have been grappling with ever since Napoleon died. The plain fact is Napoleon divides historians, what precisely he represents is deeply ambiguous and his political character is the subject of heated controversy. It’s hard for historians to sift through archival documents to make informed judgements and still struggle to separate the man from the myth.

One proof of this myth is in his immortality. After Hitler’s death, there was mostly an embarrassed silence; after Stalin’s, little but denunciation. But when Napoleon died on St Helena in 1821, much of Europe and the Americas could not help thinking of itself as a post-Napoleonic generation. His presence haunts the pages of Stendhal and Alfred de Vigny. In a striking and prescient phrase, Chateaubriand prophesied the “despotism of his memory”, a despotism of the fantastical that in many ways made Romanticism possible and that continues to this day.

The raw material for the future Napoleon myth was provided by one of his St Helena confidants, the Comte de las Cases, whose account of conversations with the great man came out shortly after his death and ran in repeated editions throughout the century. De las Cases somehow metamorphosed the erstwhile dictator into a herald of liberty, the emperor into a slayer of dynasties rather than the founder of his own. To the “great man” school of history Napoleon was grist to their mill, and his meteoric rise redefined the meaning of heroism in the modern world.

The Marxists, for all their dislike of great men, grappled endlessly with the meaning of the 18th Brumaire; indeed one of France’s most eminent Marxist historians, George Lefebvre, wrote what arguably remains the finest of all biographies of him.

It was on this already vast Napoleon literature, a rich terrain for the scholar of ideas, that the great Dutch historian Pieter Geyl was lecturing in 1940 when he was arrested and sent to Buchenwald. There he composed what became one of the classics of historiography, a seminal book entitled Napoleon: For and Against, which charted how generations of intellectuals had happily served up one Napoleon after another. Like those poor souls who crowded the lunatic asylums of mid-19th century France convinced that they were Napoleon, generations of historians and novelists simply could not get him out of their head.

The debate runs on today no less intensely than in the past. Post-Second World War Marxists would argue that he was not, in fact, revolutionary at all. Eric Hobsbawm, a notable British Marxist historian, argued that ‘Most-perhaps all- of his ideas were anticipated by the Revolution’ and that Napoleon’s sole legacy was to twist the ideals of the French Revolution, and make them ‘more conservative, hierarchical and authoritarian’.

This contrasts deeply with the view William Doyle holds of Napoleon. Doyle described Bonaparte as ‘the Revolution incarnate’ and saw Bonaparte’s humbling of Europe’s other powers, the ‘Ancien Regimes’, as a necessary precondition for the birth of the modern world. Whatever one thinks of Napoleon’s character, his sharp intellect is difficult to deny. Even Paul Schroeder, one of Napoleon’s most scathing critics, who condemned his conduct of foreign policy as a ‘criminal enterprise’ never denied Napoleon’s intellect. Schroder concluded that Bonaparte ‘had an extraordinary capacity for planning, decision making, memory, work, mastery of detail and leadership’. The question of whether Napoleon used his genius for the betterment or the detriment of the world, is the heart of the debate which surrounds him.

France's foremost Napoleonic scholar, Jean Tulard, put forward the thesis that Bonaparte was the architect of modern France. "And I would say also pâtissier [a cake and pastry maker] because of the administrative millefeuille that we inherited." Oddly enough, in North America the multilayered mille-feuille cake is called ‘a napoleon.’ Tulard’s works are essential reading of how French historians have come to tackle the question of Napoleon’s legacy. He takes the view that if Napoleon had not crushed a Royalist rebellion and seized power in 1799, the French monarchy and feudalism would have returned, Tulard has written. "Like Cincinnatus in ancient Rome, Napoleon wanted a dictatorship of public salvation. He gets all the power, and, when the project is finished, he returns to his plough." In the event, the old order was never restored in France. When Louis XVIII became emperor in 1814, he served as a constitutional monarch.

In England, until recently the views on Napoleon have traditionally less charitable and more cynical. Professor Christopher Clark, the notable Cambridge University European historian, has written. "Napoleon was not a French patriot - he was first a Corsican and later an imperial figure, a journey in which he bypassed any deep affiliation with the French nation," Clark believed Napoleon’s relationship with the French Revolution is deeply ambivalent.

Did he stabilise the revolutionary state or shut it down mercilessly? Clark believes Napoleon seems to have done both. Napoleon rejected democracy, he suffocated the representative dimension of politics, and he created a culture of courtly display. A month before crowning himself emperor, Napoleon sought approval for establishing an empire from the French in a plebiscite; 3,572,329 voted in favour, 2,567 against. If that landslide resembles an election in North Korea, well, this was no secret ballot. Each ‘yes’ or ‘no’ was recorded, along with the name and address of the voter. Evidently, an overwhelming majority knew which side their baguette was buttered on.

His extravagant coronation in Notre Dame in December 1804 cost 8.5 million francs (€6.5 million or $8.5 million in today's money). He made his brothers, sisters and stepchildren kings, queens, princes and princesses and created a Napoleonic aristocracy numbering 3,500. By any measure, it was a bizarre progression for someone often described as ‘a child of the Revolution.’ By crowning himself emperor, the genuine European kings who surrounded him were not convinced. Always a warrior first, he tried to represent himself as a Caesar, and he wears a Roman toga on the bas-reliefs in his tomb. His coronation crown, a laurel wreath made of gold, sent the same message. His icon, the eagle, was also borrowed from Rome. But Caesar's legitimacy depended on military victories. Ultimately, Napoleon suffered too many defeats.

These days Napoleon the man and his times remain very much in fashion and we are living through something of a new golden age of Napoleonic literature. Those historians who over the past decade or so have had fun denouncing him as the first totalitarian dictator seem to have it all wrong: no angel, to be sure, he ended up doing far more at far less cost than any modern despot. In his widely praised 2014 biography, Napoleon the Great, Andrew Roberts writes: “The ideas that underpin our modern world - meritocracy, equality before the law, property rights, religious toleration, modern secular education, sound finances, and so on - were championed, consolidated, codified and geographically extended by Napoleon. To them he added a rational and efficient local administration, an end to rural banditry, the encouragement of science and the arts, the abolition of feudalism and the greatest codification of laws since the fall of the Roman empire.”

Roberts partly bases his historical judgement on newly released historical documents about Napoleon that were only available in the past decade and has proved to be a boon for all Napoleonic scholars. Newly released 33,000 letters Napoleon wrote that still survive are now used extensively to illustrate the astonishing capacity that Napoleon had for compartmentalising his mind - he laid down the rules for a girls’ boarding school on the eve of the battle of Borodino, for example, and the regulations for Paris’s Comédie-Française while camped in the Kremlin. They also show Napoleon’s extraordinary capacity for micromanaging his empire: he would write to the prefect of Genoa telling him not to allow his mistress into his box at the theatre, and to a corporal of the 13th Line regiment warning him not to drink so much.

For me to have my own perspective on Napoleon is tough. The problem is that nothing with Napoleon is simple, and almost every aspect of his personality is a maddening paradox. He was a military genius who led disastrous campaigns. He was a liberal progressive who reinstated slavery in the French colonies. And take the French Revolution, which came just before Napoleon’s rise to power, his relationship with the French Revolution is deeply ambivalent. Did he stabilise it or shut it down? I agree with those British and French historians who now believe Napoleon seems to have done both.

On the one hand, Napoleon did bring order to a nation that had been drenched in blood in the years after the Revolution. The French people had endured the crackdown known as the 'Reign of Terror', which saw so many marched to the guillotine, as well as political instability, corruption, riots and general violence. Napoleon’s iron will managed to calm the chaos. But he also rubbished some of the core principles of the Revolution. A nation which had boldly brought down the monarchy had to watch as Napoleon crowned himself Emperor, with more power and pageantry than Louis XVI ever had. He also installed his relatives as royals across Europe, creating a new aristocracy. In the words of French politician and author Lionel Jospin, 'He guaranteed some principles of the Revolution and at the same time, changed its course, finished it and betrayed it.'

He also had a feared henchman in the form of Joseph Fouché, who ran a secret police network which instilled dread in the population. Napoleon’s spies were everywhere, stifling political opposition. Dozens of newspapers were suppressed or shut down. Books had to be submitted for approval to the Commission of Revision, which sounds like something straight out of George Orwell. Some would argue Hitler and Stalin followed this playbook perfectly.

But here come the contradictions. Napoleon also championed education for all, founding a network of schools. He championed the rights of the Jews. In the territories conquered by Napoleon, laws which kept Jews cooped up in ghettos were abolished. 'I will never accept any proposals that will obligate the Jewish people to leave France,' he once said, 'because to me the Jews are the same as any other citizen in our country.'

He also, crucially, developed the Napoleonic Code, a set of laws which replaced the messy, outdated feudal laws that had been used before. The Napoleonic Code clearly laid out civil laws and due processes, establishing a society based on merit and hard work, rather than privilege. It was rolled out far beyond France, and indisputably helped to modernise Europe. While it certainly had its flaws – women were ignored by its reforms, and were essentially regarded as the property of men – the Napoleonic Code is often brandished as the key evidence for Napoleon’s progressive credentials. In the words of historian Andrew Roberts, author of Napoleon the Great, 'the ideas that underpin our modern world… were championed by Napoleon'.

What about Napoleon’s battlefield exploits? If anything earns comparisons with Hitler, it’s Bonaparte’s apparent appetite for conquest. His forces tore down republics across Europe, and plundered works of art, much like the Nazis would later do. A rampant imperialist, Napoleon gleefully grabbed some of the greatest masterpieces of the Renaissance, and allegedly boasted, 'the whole of Rome is in Paris.'

Napoleon has long enjoyed a stellar reputation as a field commander – his capacities as a military strategist, his ability to read a battle, the painstaking detail with which he made sure that he cold muster a larger force than his adversary or took maximum advantage of the lie of the land – these are stuff of the military legend that has built up around him. It is not without its critics, of course, especially among those who have worked intensively on the later imperial campaigns, in the Peninsula, in Russia, or in the final days of the Empire at Waterloo.

Doubts about his judgment, and allegations of rashness, have been raised in the context of some of his victories, too, most notably, perhaps, at Marengo. But overall his reputation remains largely intact, and his military campaigns have been taught in the curricula of military academies from Saint-Cyr to Sandhurst, alongside such great tacticians as Alexander the Great and Hannibal.