#(the 'j' is less pronounced but if its not there it does it like english so)

Note

Hello! I recently saw your art of Ghali, Drephl and Rleiph, and decided to finally try out making wiki pages! I plan on making all three of them before adding them, but I have a few questions on about them. (Im pretty sure that you wrote the fic, but please correct me if I’m wrong)

first off, the fic is AMAZING, I cried multiple times while reading it, and everything goes together so perfectly there’s too much to talk about so I’ll stop here before it gets too long.

1) On Ghali, I wanted to double check that she took the last name Shims, because at some point it refers to the family as “the shims”

2) on Frihl, does he keep the last name Shims, or take his husband’s name?

3) can I say that Rleiph has pale speckles in her physical description?

4) could you give me more insight on Ghali’s , Drephl’s and Rleiph’s personalities? I personally struggle with describing those myself.

5) are there names for Drephl and Frihl’s parents, as I would like for them to be in the relationships category.

6) same for Rleiph’s girlfriend. Also, does she have a physical appearance? I’d love to draw the two of them together.

7) WEREWOLF CENTAUR. Amazing idea. What does the kid look like? I know that they’re described as a foal, but WHAT IS THEY JUST HAD A WOLF HALF INSTEAD OF A HORSE HALF, OR A WOLF HALF DURING FULL MOONS. I would love to know things like their skin tones and hair color too. (And coat) also thank you for all these centaurs, there isn’t even a catagory on the wiki for them yet.

8) what kind of clothes does everyone wear?

9) I know that Drephl and Ghali probably just went to a courtroom and signed some papers, but I really want to draw Drephl standing on a stool with her under an arch, where they just hug. This is also so I can mess around with possible wedding traditional clothing during that time period.

10) what is the name of Drephl and Ghali’s grandchild? The werewolf one?

Thank you for this amazing fic! Loved the art you made, and this will be very embarrassing if you didn’t write the fic!

Putting this under read more;;

Ok first of all. omg??? that's so cool what the hell!!! i'm so happy you liked my fic so much???

1) Yeah, she becomes a Shims

2) I think he takes his husband's name (which i don't have yet)

3) I forgot to give her some white in her coat in the art lol, but i decided to work that in; she's born with just a brown coat, but some white speckles start appearing as she grows older :3

4) They honestly don't have much, yet; the style i wrote in makes it really hard to add Character and Personality other than just stated facts like "she likes hiking" and "she's a computer programmer", sorry

5) Not yet, sorry

6)

7/10) I want to give them at least 2-3 kids so i can actually make them all different, though i imagine they probably have 5-8 year age differences cus raising just one is chaotic and hard enough lol. someone made really good art of their kid!!! (i've come up w the names Phil, Lei, and Majil so far) (j pronounced like (consonant) y)

8) currently i've just been drawing them in some clothes from our time cus i haven't had the motivation&energy necessary to figure out the Fashion of their time, but i can say that the blanket??? dress?? things the centaurs wear is like. actual clothing they wear in their time period&place

9) I love that so much. also, it honestly makes a lot of sense for them to hold an actual celebration; your wedding is basically the only time in your life where you have an excuse to gather every single person you're close to in one place for a big party (aside from your funeral but uh. yeah.) their marriage was meant as the point where they no longer cared what anyone else thought bc they were so secure in their meaning to each other, so i love the idea of them going all out and then just hugging.

also behold! look what i found from way back when i was writing the fic :)

#sezijasks#this is. whattttttt i didnt know ppl cared abt my fic ???#i was like "oo ive got a new tablet maybe ill finally draw the Fam''#and then out of the floorboards oozed fanart and asks and reblogs of excitement and i was like !?!?!?!??!#its made me write some additional scenes to flesh out their personalities#idk if i'll release them yet they're just lil blurps but who knows#asks#i named zir 'nail' and it took me like 10 minutes to realize thats an actual english word lmao. its pronounced more.. finnish-like#put 'najiil' in finnish google translate and make it sound it out and uve got it#(the 'j' is less pronounced but if its not there it does it like english so)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I cannot stop thinking about the implications of the Kerch alphabet on canon. I know I’m the only person who cares, but hear me out!

1. The show itself made a mistake with its own made-up language.

2. Wylan is a foreign name or he’s a Tragedeigh child.

Explanation below:

Daddy

Right before Jesper and Wylan meet Alby Rollins, Jesper finds a child's drawing labelled “Daddy.” In Kerch the word uses 3 distinct D letters, one of which is attached to the vowel. And bizarrely at the end of the word, the letter J/Y. The English translation is literally labelled beneath it so we know exactly what it says.

But according to the two alphabet charts here, there is no Y vowel in the Kerch language. The Y is given a J sound, (as in Jan Van Eck pronounced as Yan Van Eck) which makes sense given the Dutch influence on Ketterdam.

So Alby’s drawing says, “Daddya.” Daddy in Dutch is Papa, according to my nifty translation app. Where does Daddya come from? Either Daddya is a Kaelish pronunciation given the Rollins' Kaelish heritage despite it being spelled in Kerch, or the show made a mistake.

I think the J/Y letter may have been used to keep the same number of letters to make the connection between Kerch Daddy and English Daddy the same for the audience to quickly make the connection.

However, in Kerch the word Daddy should be spelled as “Daddee” with the hard E vowel attached to the last D consonant.

(When ranting about this to my husband, he listened to this entire spiel, then asked quite confused, “Who’s calling who Daddy in this show? That sounds more like a fanfic thing rather than something from canon...” 🤣 Saints, I love that man.)

2. Now let’s talk about Wylan’s name because it fascinates me.

There is no hard I vowel in the Kerch language. It just doesn’t exist. There is a hard A, E, and O, but no hard I. The name Wylan (pronounced Why-lan) cannot be written in Kerch.

Matthias’s name cannot be spelled in Kerch either. But that’s ok because he’s not from Kerch. He’s from Fjerda, where presumably, he can spell his name in his native language. Because it would be very silly to give someone a name that is unpronounceable in their native linguistic system. Right?!?

Except Wylan is as Kerch as Kerch gets. His family is old money with strong roots to the country and culture.

So what happened?

Maybe the name Wylan comes from one of the other cultures, Fjerdian or Kaelish. We don’t know much about Marya Hendricks/Van Eck and her family/cultural roots, but we do know that book Wylan inherited her red hair. So maybe somewhere in her family tree there’s Kaelish ancestry. Or she just really liked a Kaelish or Fjerdian name enough to give it to her son.

This explanation makes the most sense, but at the same time, I can’t imagine Jan Van Eck, a man so concerned with family legacy, not choosing a Kerch name for his oh-so-important heir.

So consider this alternative explanation: Jan Van Eck just sucks as a human being and gave his son a Tragedeigh name. AKA a name that is spelled and or pronounced nonsensically enough it makes you want to pat the kid on the back and legally help them change their name to something less awful.

For the record, I think Wylan is a lovely name. But it doesn't make sense as a Kerch name given how it uses sounds/letters not in the language.

Wylan’s name could still be pronounced as Why-lan and still written as Way-lan in Kerch. Or Will-lan, or even Wee-lan. We don’t know because we didn’t get to see it in show. There’s no hard I and some vowel needs to be used!

So Wylan was that kid who spent his entire life correcting everyone on how to say his name. Because his name was spelled one way but pronounced another. It’s simultaneously hilarious and tragic. The idea that his family was so wealthy that they gave him a special, nonsensical rich person name. And because Wylan can’t read he has no way of knowing why everyone says his name wrong if they see it written first. Ghezen, he'd be exhausted correcting everyone who met him.

Absolutely headcanoning that Jan Van Eck tried yet another way to screw Wylan by giving him a ridiculous name that can't even be written in Kerch.

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

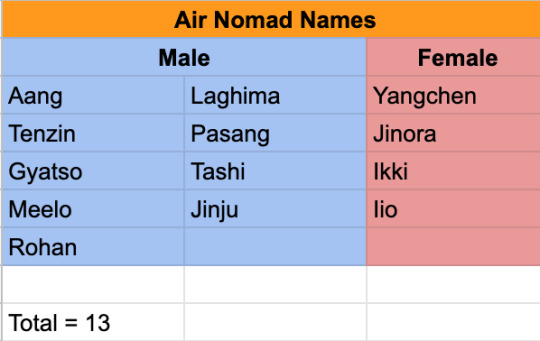

Patterns in Given Names in the World of Avatar

Or, Naming Your Avatar OC’s: Beyond Baby Name Lists

Naming an original character in any fantasy setting can be a tricky business. Do you use a real name? Do you make one up? Either way, it has to sound like it fits into the established world - but you don’t want it to sound too similar to the names of canon characters, either. In this post, I will offer an analysis of canon names of major and minor characters in Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Legend of Korra, looking for discernible patterns in the names of each of the fictional cultures of that world, and offer some suggestions based on my own experience for how to choose or create names for original characters in that world.

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with using a “baby name list” for inspiration or even taking a real name from one of the cultures the show is based on and using it. But since the fictional cultures of the show are not complete carbon copies of real cultures, just picking a name from a list of Inuit or Japanese names won’t always give you one that actually fits in with the Avatar world. And maybe you’ve seen enough Water Tribe OC’s named Nanook (I’m guilty of this one myself) and want to get a little more creative. In that case, welcome to the advanced OC naming class.

And yes, there will be color coded spreadsheets.

Methods and Goals

To get a feel for what sort of names will sound like they fit into the world of Avatar, we of course have to look at the names of canon characters. For our purposes, I chose to exclude characters who only appear in spin-off material such as the comics or Kyoshi novels, and only look at the given names of characters from the two shows, Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Legend of Korra. I have sorted the characters by nation, as well as into cultural subdivisions where applicable. LoK characters from the United Republic of Nations have their own category, since in most cases we do not technically know the specific cultural origin of those characters’ names - though based on the patterns below and other context clues, we can make a reasonable guess for many of them. Characters whose names appear to be nicknames or pseudonyms (such as Longshot and Lightning Bolt Zolt) have also been left out.

The aim of this analysis is to look for phonetic and other patterns in the names of each cultural group within the world of Avatar. We will be looking at the names as spelled using the Latin alphabet, since this is how most fan fiction is written, and how the character names are given in official material, but keep in mind that within the world of the show, all nations use the Han Chinese writing system, so names or syllables spelled differently in the Latin alphabet might be represented by the same character in-universe, or vice versa.

Finally, my guidelines and suggestions for how to choose or create OC names are just that: guidelines and suggestions. These are not rules. It’s your OC, you do what you want.

Without further ado, let’s start looking at some names.

The Water Tribes.

We don’t have quite the sample size for Water Tribe characters that we’ll see for some of the other nations, but 28 names is still plenty to look at. Notably, we have far more male (18) than female (10) names, a pattern we will see repeated without exception. Draw your own conclusions.

Water Tribe names appear to mostly be two or three syllables long, with most of the one syllable names being from the Foggy Swamp Tribe. Hahn from the Northern Water Tribe is the only other one syllable name. Two syllable names are the most common with 19 names, which is about two-thirds of the total. Three syllable names account for 5 out of the total 28, or less than one fifth - still, this makes them more common than names of the same length in any other nation, and more common than one syllable names in the Water Tribes, especially if you exclude the Foggy Swamp. If you’re looking to use an authentic Inuit or other Arctic indigenous name for your Water Tribe OC, I would be wary of names longer than three syllables, though, as we have none of these in canon.

Consistent with Inuit names, we do have a lot of /k/ and /g/ sounds. The letters K and Q are pronounced the same in Water Tribe names, though in Inuit they represent different sounds. 18 out of the 28 names have at least one of these sounds, with /k/ being far more common than /g/ (17 vs. 2 names). Of course, having the letter K in your Water Tribe OC’s name is by no means necessary, and especially if you are creating a lot of Water Tribe characters, you probably want some variation.

The digraphic consonant sounds /ch/, /sh/, and /th/ are almost totally absent, with the exception of one name from the Foggy Swamp, Tho. The /r/ sound is also never found at the beginning of a name, and the /j/, /l/, /w/, and /f/ sounds are totally absent. The /v/ sound is absent from all given names, but notably appears in the surname Varrick not included above.

Regarding gender differences, both male and female names can end in -a, but this is much more common for female names, with 3 male names compared to 8 female names having this ending. Notably, this accounts for all but two of the female names, and all of the female names end in a vowel. Consonant endings appear to be exclusively masculine, with final /k/ sounds being common, whether spelled with K or Q (8 out of 18 male names), though masculine names can also end in vowel sounds.

There do not appear to be major differences between the Northern and Southern Water Tribe names, however the three names we have from the Foggy Swamp Tribe are definitely distinct - all one syllable, and all open syllables ending in vowels. These sound more like Earth Kingdom names, as we’ll see, which makes sense given the location of the Foggy Swamp.

To my knowledge, only handful of the Water Tribe names are authentic Inuit names, and they are all characters from LoK: Desna, Yakone, Noatak, Unalaq, and Tonraq, or 5 out of the 28 total names. Yue is an authentic name, but a Chinese one. The main Water Tribe characters such as Katara, Sokka, and Korra all have invented names. So yes, you can pick from an Inuit baby names list (and Nanook does fit the patterns we see above), but you are by no means limited to this.

The Earth Kingdom

Since the Earth Kingdom is the largest of the nations, it makes sense that we have the most names to look at here, with 79 names total, including 56 male names and 23 female names. I’ve included Jet with a question mark, because he may be using a pseudonym like the rest of the Freedom Fighters do, but his name is also plausible as the one his parents gave him. Macmu-Ling, the name of the haiku master in Ba Sing Se, may also be a surname, but this is unclear given the limited information on the character.

One syllable names are much more common in the Earth Kingdom, accounting for 30 out of 56 male names and 10 out of 23 female names. This is roughly half of all Earth Kingdom names, or 40 out of 79. Two syllable names account for 34 out of the 79, or about 43%, with three syllable names being rare overall, just 5 names or 6%. Overall, Earth Kingdom names tend to be shorter, which is consistent with a basis in Chinese, Korean, or Vietnamese names.

Unlike with Water Tribe names, there do not appear to be specific sounds that stand out as distinctively Earth Kingdom. Notably, nearly all names begin with consonants, with only 6 names beginning with a vowel, and always A or O. All of the consonant sounds found in English are represented in at least one name. The /ch/, /sh/, and /th/ digraphic sounds are all present, though not abundantly common. The Earth Kingdom being large and diverse, this greater diversity in names also makes sense.

There is evidence of unisex names in the Earth Kingdom. Wu is used by both a male and female character (Prince Wu and Aunt Wu), and the name Song which is listed as female above we will see again as the name of a male earthbender in Republic City. Other names could also be unisex, but as most are only used by one character, we have no way to know. The only noticeable gendered pattern seems to be that several female characters have English names, which I separated into the fifth column above. This seems to be exclusive or near-exclusive to Earth Kingdom women. Jet could also be interpreted as an English name, but as previously mentioned, this is possibly a pseudonym anyway.

The few named characters we have from Kyoshi Island all have authentic Japanese names, or at least names taken from the Japanese language - oyaji is an affectionate term meaning “old man” or “father”. Kyoshi is distinct from the rest of the Earth Kingdom in many other ways, including a history of isolationism which Japan also has. As for the sandbenders, we only have two names, but Ghashiun stands out as rather distinct in its spelling. Visually, the sandbenders resemble the Tuareg people of the Sahara region, so that might be the direction you want to go if you’re looking for authentic names to use for your sandbender OC’s.

The curious name Macmu-Ling is based on the surname of the writer for the episode she appeared in, Lauren MacMullan.

Fire Nation

We have 13 female names and 33 male names, for a total of 46 known Fire Nation names.

Two syllable names are most common, with 20 male and 6 female names, accounting for 26 out of the total 46, which is more than half. 15 names have one syllable, which is about one third of the total. Only 5 names have three syllables, or just one tenth, and once again there are no names longer than that.

The letter Z stands out as appearing in 8 names, while it’s much more rare in the other nations - though notably the Z in Zhao is pronounced differently than in the other names. Also worth noting is that all the names with Z other than Zhao - that is, all the names where Z is pronounced as it would be in English - are names of members of the royal family, with the exception of Kuzon. The digraphic sounds /ch/ and /sh/ are both present, but /th/ is not. Other absent sounds include /v/ and /w/.

The Fire Nation gives us our only example of gendered variants on the same name with Azulon and Azula. This implies that the -a ending is generally feminine, though we only have two female names that use it. Ilah ends with the same sound, albeit spelled with a silent H. There is also one masculine name, Yon Rha, that ends in -a, though with a different pronunciation (/ah/ vs. /uh/). The -on ending may also be masculine or generally masculine, but again, only two names use it. Female names are also more likely to end in the /ee/ sound, whether spelled -i or -ee, with 6 of the 13 female names ending this way. Only two male names end with this sound, and one of them, Li, is unisex.

In terms of basis in real world cultures, the Fire Nation often gets heavily identified with Japan in fanon, because they are an island nation with a history of imperialism, but what we see in canon is much more of a blend of Asian cultures, like the other nations. Some names, like Izumi and Roku are Japanese in origin, but some are also Chinese or Chinese-based such as Chan and Lu Ten. And as with the Water Tribes, the main characters like Zuko, Azula, Iroh, and Ozai, tend to have invented names. (Zuko especially would be odd as a Japanese name, since the -ko suffix in Japanese is feminine.) The name Ursa, curiously, is Latin - the feminine form of the word for “bear”. So while you certainly can use Japanese names for your Fire Nation OC’s, as with Inuit names in the Water Tribe, you’re not limited to that by any means. In fact, based on what we see in canon, I would say that if you’re creating several Fire Nation OC’s, you should have about an even mix of Japanese, Chinese, and invented names.

Air Nomads

With only 13 names, of which 9 are male and 4 are female, this is the smallest sample we have for any of the nations - understandably, since the Air Nomads are all but extinct for most of both shows. We’re even technically assuming that all of Tenzin’s children have Air Nomad names, but this is probably a safe assumption.

Two syllable names are still most common, with 9 of the 13, or about three fourths of the total. There are three names with three syllables, or a little less than one fourth. Aang has the only one syllable name.

With so few names, it’s hard to draw firm conclusions about phonetic patterns. The -a ending is seen on one name for each gender, as is the -i ending, and the -o ending appears on two male names and one female name. The -u ending only appears on one male name, but given the small sample size this doesn’t necessarily indicate a female Air Nomad name couldn’t have the same ending.

We do have clear and distinct real world basis for several Air Nomad names. Tenzin and Gyatso are both taken from the religious name of the current Dalai Lama. Rohan is an Indian name, and Laghima is a Hindu term for the spiritual power of becoming weightless. (Coincidentally, Rohan is also a French surname, but it was presumably the Indian name that the show meant to reference.) Pasang is a Nepali name, though a female one as far as I can tell, whereas it is used for a male Air Nomad. Tibetan, Nepalese, and Sanskrit names would thus all be good places to look for inspiration for your Air Nomad OC’s - though again, don’t feel limited to that. Chinese inspired names would also fit in, and Aang, like all the main characters, has an invented name.

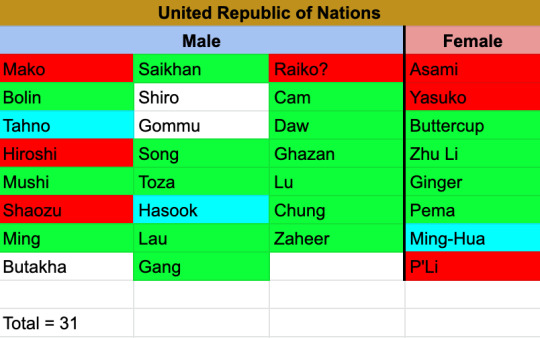

United Republic of Nations

This group of character names, all from The Legend of Korra obviously, has to be considered differently. While we can make educated guesses as to the fictional ethnicity of most of these names, the fact is that many of these characters may be of mixed heritage and we can’t say for sure what the origins of their names are. In the chart below, I have color coded the names according to my best guess for nation of origin, rather than by gender. Names left in white, in my opinion, could be either Earth Kingdom or Fire Nation, and nothing about those characters gives us further clues.

With 31 names, we do have a decent sample size. Presumably Mako is a Fire Nation name and Bolin is Earth Kingdom, and based on the sound they do seem to fit in with those nations respectively. Raiko has a question mark because it is unclear if this is a given name or surname, but it does seem to follow the Zuko and Mako pattern and thus be most likely Fire Nation in origin. We also have the name Yasuko, for a character who is supposed to be of Fire Nation descent, using the -ko suffix on a feminine name.

Ginger and Buttercup I have designated as most likely Earth Kingdom because they are English names, and as we previously saw, only Earth Kingdom women seem to have names of this variety. Pema is presumably of at least partial Earth Kingdom descent based on her green eyes - this is also a real Bhutanese name. Characters like Lu, Gang, Daw, and Chung are all shown wearing green, and have one syllable names of the kind which are most common in the Earth Kingdom.

Hasook has a very distinctively Water Tribe name, and is of course a waterbender. Tahno and Ming-Hua are both waterbenders as well, though their names are less distinctively Water Tribe. These could simply be less typical names from one of the two polar tribes, or they may have Foggy Swamp Tribe heritage. (I believe this was a popular headcanon for Tahno, at least.) The possibility also exists that they have mixed heritage and may have Earth Kingdom or even Fire Nation names in spite of being waterbenders.

Conclusion

Like everything else in the world of Avatar, the names of the characters are inspired by and based on many real world cultures, primarily Asian, but no one fictional nation in the Avatar world corresponds exactly to a real world culture. When we look for or create names for original characters in this world, we want to respect the real world basis of these fictional cultures, but simply picking a Chinese, Japanese, or Inuit name from a list may not always jive with what we see in canon, in addition to running the risk of being a bit stereotypical.

With the canon patterns outlined above, fan fiction writers and fan artists should feel free to expand their search for names to other Asian, Arctic, or North African cultures, such as Thai, Burmese, Nepalese, Yupik, Aleut, or Berber names. Baby name lists can be helpful, but are often dubiously reliable, especially for non-Western cultures. Personally, when I want to give an OC an authentic name, I prefer to use Wikipedia to find real people from the culture or cultures I’m drawing on. I’ve joked about my own tendency to pick names of Japanese, Chinese, and Korean saints for my fan fiction, but searching for Wikipedia lists or categories of artists, philosophers, or scientists from a given culture can also be useful.

Wherever one chooses to look, name lists are best treated as a starting place - a name from a given real culture won’t necessarily fit into a given Avatar culture, and a name from a certain Avatar culture does not have to come from any particular real world culture. Fans should also feel free to invent names of their own, as the creators of Avatar did. Of the 20 major OC’s in my story Fate Deferred, half of them have real names or variations on real names, and the other half are invented.

And if you want to have a female Earth Kingdom OC named something like Jasmine or Crystal - these are also perfectly in line with canon.

#avatar the last airbender#legend of korra#atla#atla meta#fan fiction#catie writes things#y'all wanted it now here it is

554 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shaman King - Name Games

I didn’t really intend to expand this accidental series of Bleach posts outside one series, but I was looking back at Shaman King, what with the new anime having been announced, and to be honest there’s not a lot to pick at in this particular regard --a lot of the names are pretty straight forward, or just not Japanese, and the O.S. are all similarly named, predominantly in English or with pretty straight forward Japanese epithets.

Like, for example Amidamaru’s name is just written as Amida[阿弥陀] as in the Japanese name for the Buddha, Amitabha, and -maru[丸] super common super generic suffix for boys’ names. All his attack names are accordingly Buddha themed. There’s no real obscure or obtuse kind of references or anything that isn’t really self explanatory. It does tie into Yoh’s general attitude and personal philosophies being zen influenced, which I guess takes a bit of a leap if you’re not familiar, but again it’s pretty obvious.

Then his Over Soul names are all things like:

阿弥陀丸 = “Amidamaru”

スピリット・オブ・ソード = “SUPIRITTO OBU SOODO” = “Spirit of Sword”

...白鵠 = “...Byakko ” = 白:“White,” 鵠:”Swan”

Really straight forward. English readers really weren’t missing much.�� Or at least if they were reading Mankin Triad’s scanlations. (I’ll be honest, I never read all the Viz prints front to back.)

But you know what are some fun kanji readings that TOTALLY get missed in English? The actual names of the main character. And granted, a lot of characters in the series aren’t Japanese so they don’t all get fun clever names, but the Asakura family is like one big running joke...

So, in-world, the family itself starts in Japan in the 900s with an orphan child named Asaha(麻葉) Douji(童子) whose names read as “Hemp”+”Leaf” and “Child(implicitly a boy)” but also an archaic reading meaning “Scholar" or depending on context “Sorcerer.“

For a little context, despite Japan having rather notorious modern marijuana policing, hemp was actually a widespread and integral crop in Japan for hundreds of years so it’s not an uncommon component of names in the first place. It’s also the basis of a very common pattern in traditional Japanese fabric printing (and you’d probably seen it before in period settings in anime, manga, J-dramas, or film) it’s called Asanoha(麻の葉) and you’ll notice is the exact same kanji as the name Asaha.

The boy, Asaha, grows up to be a powerful onmyoji and changes his name to Asakura(麻倉) Hao(葉王) meaning “Hemp“+”Storehouse/Warehouse/Treasury“ and “Leaf“+”King.” Considering the name “leaf” clearly refers back to the family name’s, “hemp” I really hate to admit it, but Hao’s name is basically “Weed Lord” of the family “Weed Stash.“ If it wasn’t clear this is also why Takei draws a lot of cannabis leaves in association with Yoh(葉) whose name is just written with the same kanji as Hao’s for “Leaf” but with an alternate reading.

Yoh’s super chill and laid back personality and his ever present headphones for relaxing to are all part of this theme in his name. This theme is also why he’s a fan of Soul Bob (aka totally-not-just-Bob-Marley) and why Soul Bob posters are everywhere in the background of Shaman King. The Asakura family crest, adapted from the Onmyodo five-path star, also resembles a leaf not unintentionally --I don’t remember if they openly refer to that fact in-world or not.

But as we follow the rest of the family tree from there we get the ancestor Yohken(葉賢) from 500 years ago, Yoh’s grandparents Yohmei(葉明) and Kino(木乃), his mother Keiko(茎子) and father Mikihisa(幹久), and eventually his son Hana(花). Also the branch family’s Yohkyo(葉虚), and his kids Ruka(路菓) and Yohane(葉羽). And you’ll probably already notice a lot of those names use the same Yoh/Ha(葉) that is the basis of both Yoh and Hao’s names.

So the rest of the family’s names go...

Yohken(葉賢) = “Leaf”+”Wisdom” which, at face value, is just naming him as a wise shaman. But it’s also basically a cheeky euphemism for “stoner logic.”

Yohmei(葉明) = “Leaf”+”Insight” synonymous with Yohken’s reading.

Kino(木乃) = “Tree”+”From/<posessive indicator>,” so “Hemp Tree” basically

Keiko(茎子) = “Stalk/Stem”+”Child” but keeping in mind that -ko(子) is just a super common suffix for girls’ names, so it’s not like she’s being called explicitly child-like or anything, her name is basically just “Stem Girl”

Mikihisa(幹久) = “Stem”+”Longtime” but I’ll come back to him...

Hana(花) = “Flower” but also a phonetic play on ha(葉) + na(ナ) from his parents’ names

Yohkyo(葉虚) = “Leaf”+”Void/Empty” (haha that’s the same “Hollow” used for Hollows in Bleach) As the head of the disgraced branch family of the Asakura house, his name reflects that he’s not part of the family, despite the family surname, by basically just calling him “No Leaf.” Technically it could also read “Fruitless Leaf” which kinda sticks to the plant imagery better, but makes a little less sense when he has kids...

Ruka(路菓) = “Way/Path/Road” + “Fruit” I assume this is meant as “Way of Fruit” like a metaphor for the fact that she’s been tasked with leading the branch family to success, and not “Road Fruit” as in fruit you’d find on the road, or by the side of the road. Although that does kind of fit in its own way.

Yohane(葉羽) = “Leaf“ + “Feather“ which I think is a play on the fact that when traced back to Jodai era(700s CE) etymology both words shared a common root word, reflecting the fact that he’s got the same ancestor as the core family, but has developed differently but in parallel.

So I said I’d come back to Yoh’s dad, Mikihisa, because as an outsider who married into the Asakura family he has an original family name other than Asakura. His full name is Miki(真木) Mikihisa(幹久) which read as “Truth“+”Tree” and “Trunk/Stem“+”Long Time“ which has some nuance to it. Obviously “Long Time Trunk” and “Tree (of) Truth“ evoke the image of an old and venerable tree with a thick and many ringed trunk. That image plays into Miki’s role as a Shugenja --there is a whole lot going on with the history of the religion, more than I can reasonably summarize, but the thing to know here is that the popular image of Shugenja in media leans into them being ascetic monks, living in the wilderness, generally forest mountains, with an association with Tengu.(Tengu are frequently dressed in Shugendo attire.)

So, the forest man is named after a big tree, pretty straight forward... The clever bit here is how once he takes the Asakura name his name can be read to match his wife’s, as the (幹) in Mikihisa and (茎) in Keiko can both read as “Stem.”

Unrelated to anything, but it’s always super weird to me that English translators insist on calling him “Mickey” (they did the same with Kaoru Miki in Revolutionary Girl Utena....)

And while I’m talking about outsiders, I’ll bring in Anna as well. Her given name is actually just written in katakana as An’na(アンナ) so, unlike Mikihisa, her name in English is untouched. But her family name Kyoyama (恐山) is written “Fear/Dread/Awe“+”Mountain“ which is both a description of her character as an imposing figure in Yoh’s teen life, but also a reference to Mt.Osore(恐山) where she first meets Yoh, which is both home to a famous Buddhist temple and a mythological location of the gate to the underworld. It is of course written with the same kanji as her family name but pronounced differently, as you can see.

The American, Alumi(アルミ) Numbirch(ニウムバーチ) is obviously named after Aluminum, as all the Patch are named after metals. I’m not really sure why the “-birch” part is in there? It might be an obtuse play on the fact that the Japanese White Birch is also called the Siberian Silver Birch, and her dad is Silva? It feels like a bit of a stretch, but I can’t think of another way “birch” would be relevant to her name. But otherwise she’s not really related to the family theme.

And not at all related to the Asakura’s, but beautiful androgynous British boy detective, Lyserg Diethel is named after the hallucinogenic compound Lysergic acid diethylamide. (aka LSD/Acid) The drug themes is part of why his spirit is named Morphine. She is a nature spirit of (of course) a poppy flower. The other reason she’s named Morphine is because Sherlock Holmes --from whom Lyserg gets his inverness cape aesthetic-- infamously used recreational morphine (and cocaine) to alleviate himself of the lethargy of being without a case to solve.

190 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rating the letters of the alphabet

I feel like part of my style of comedy is just rambling about shit and making loose connections between things as part of an overall bit. I think. I’m no expert on myself, unfortunately.

The inspiration for the following absolute load of shite is trying to search Tiermaker for nothing. Like, no characters in the search bar. Didn’t come up with anything. Did a search for just a space. No dice. What about just a? Surely that’ll bring up everything with an A in the title. But it didn’t, and I was somewhat disappointed.

Then my head started writing bits about letters and that’s how we got here. This is probably really stupid, but maybe it’ll at least be fun. Wordplay is cool, though maybe not my strong suit? Anyway.

A: A is one of the two letters that’s also just a word, as you’ve just seen, giving it a necessary promotion in rank. Not a lot of things get to double up like that, though with the “an” ligature maybe it’s actually a double or nothing. But because of the confusing common connection crossing contexts for the character, it gets somewhat awkward to talk about the letter in conversation. An A, in my opinion, A does not get. 4/5.

B: B is also just a word letter but unlike A when you write it out you have to stick a few extra letters on to make it work, making it not as good. But B’s association with bees isn’t enough, because in the year of our lord, like, 2019 or something, it would become inextrixably linked with shite memes as the B emoji became king. And I just don’t respect that. It’s otherwise a fine letter, dragged down by its company. 2/5.

C: Oh come on now, the word doesn’t even have a C in it anymore! You can sea the see without any of our tertiary letter’s involvement whatsoever. Not to mention how its two main sounds are just copies from other letters wholesale. C must be confusing to non-english speakers, I’d imagine. C as a grade gets what C as a grade typically entails for many a schoolchild. 3/5.

D: It would be remiss of me not to give a sterling grade to the D. Why, none of us would be here without it. While many a youth may find the D to be quite a humourous subject, I assure you I’m taking it with the gravest of sincerity when I say the D has got to be one of the best letters of all.

And by D I mean deity, of course. Wait, what did you think I meant? 5/5.

E: The absolute absurdity that is the E meme elevates E efficiently enough to excel beyond many another vowel. However, it is also the single most common letter in the English language, going so far as to open the damn name. It’s to the point where someone made a point of writing an entire book without using it, and I think Gadsby is cool but mayhaps avoiding fifth uncial was a bit showy. I can’t help but mark it down for the sake of hipster cred. 3/5.

F: F is for Fuck. I like the word Fuck. F is for paying respects. I think the military-industrial complex has poisoned our cultural landscape to the point that a reference to one of its most prized productions’ awkward moments has become one of the most colloquially used meme letters in existence, And That’s Terrible. 3/5, I’m conflicted.

G: Man literally who the fuck cares about G. What is it even good for. Just an absolute waste of a letter, total shithouse. It’s NATO equivalent is Golf, the Worst Sport, too. Who asked for any of this? Just use a J instead, it’s cooler. 1/5.

H: I’ve seen “Hhh” used enough times in written forms of pornography to not consider it a Horny Letter. That and it, being short for Hentai, is often used to denote adult material in Japan. Basically what im saying is, I think this gets worse the less sex-positive you are. 6/9.

I: I think I’ve said enough about letter words already, but I is another high-tier one because like A I is just it’s own thing. It can also, however, be a bit confusing, looking just like an l a lot of the time, and having to constantly capitalise it is a pain in the ass. I also don’t have a particularly high opinion of myself, so a high opinion of I seems disingenuous. 3/5.

J: Clearly the best letter, hands down. I’m definitely not biased. There are so few letters as underappreciated by J- a fact many a person who’s had to do that “assign yourself an alliterative adjective” icebreaker game has had to reckon with. Because it appears to be a lot more popular with names than with words, and that just kind of sucks. 6/5.

K: K has in some circles managed to bump off its partner to become yet another letter word, though in a very informal abbreviated sense. However, when you’re looking into scientific fields, eventually said partner returns, having lost some weight on the trip down to absolute zero. This all makes complete sense in my head, and I’m sure is a lot less funny to anyone who doesn’t live there. 4/5.

L: I’d argue that L doesn’t cop its namesake. It’s a really useful letter, loads of words use it, especially in pairs, and my ADHD-brain thought it was fun to just say LLLLLLLLLLL for a bit while I was thinking about this so I guess that’s staying in now. Put me down as an L Lobbyist. 4/5.

M: Mmmmmm. M&Ms. But also it’s kind of a pain to write. Hmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm. 3/5.

N: I’d like to fight whoever decided we should have two letters that sound so similar right bloody next to each other in the alphabet. Actually, who the fuck even decided the alphabet’s order to begin with? Maybe it should go M to N, that’ll bloody show you. 2/5.

O: Our fourth vowel, and perhaps one of the underappreciated ones. O is similarly a letter word, but a much more common one considering its use as an interjection. It’s also one half of a very powerful letter combo, as we’ll see. 4/5.

P: There’s the other half. Many a joke involves OP as a phrase, whether it mean overpowered or original poster, and the letters’ adjacency is a lovely bit of serendipity. Whenever I say P out loud, on its own, I have to resist the urge to do some incredibly shitty beatboxing, which may or may not be a good sign. 4/5.

Q: I was going to write some very harsh words about Q, and its dependency on U, but then I realised that that is probably hate speech against the disabled. It still sucks, though. 0/5.

R: R is the one I am most struggling to think of things to say about. R is another letter that’s just kinda there. I’m sure the Roberts and Rachels of the world would disagree with me, though. It’s also the name of a program that I know has traumatised a lot of young biologist wannabes, slapping us with a whole pile of maths and statistics when we just wanted to look at cool plants and shit. Or in my case, cool cells and shit. 2/5.

S: The most overrated consonant, but also the thing that makes plurals not a pain in the ass. However I’m going to lean towards giving S a positive rating, if only because it’s associated with snakesssss (and serpentine characters who can talk) and I like those. 3/5.

T: I don’t think T gets enough credit as one of the pillars of the English language. A lot of very common words feature it, and yet it feels like it never gets the same level of credit as big shots like S or half of the vowels. T is like the character actor of the alphabet, is basically what I’m saying. 4/5.

U: Ah, the letter Americans hate for some reason. I think this is actually commentary on the history of American politics. Because throughout history, America has been extremely selfish and self-centered, while attempting to present a positive image that people are finally seeing past. They only entered WWI and WWII when it was convenient for them, they started wars and initiated coups in even their allies for petty ideological reasons, and they’ve gone to war with several countries and funded wars with several others seeming just for shits and giggles. Because apparently if you’re not an American, then you’re not one of them, and that means they hate U. 4/5.

V: I actually think V is underrated. It’s a fun sound. That’s it, no joke here. It’s neat, I like it. 4/5.

W: This may come as a shock to you, but double-u over here is actually two Vs! unless you’re writing in cursive, but fuck cursive. The French actually have it right on this one, naming it double-v (pronounced doobleh-vay). Add in the fact that it’s literally just M upside down, and you’ve got a pretty shite letter. 1/5.

X: There’s a reason literally every “A is for Apple” thing you see made for kids uses Xylophone for X, and that’s because there are no commonly used words that start with it. Seriously, it’s all just scientific terms- I’d argue X-Ray is more common than Xylophone in common parlance, but also, who wants to explain imaging to a kid. It doesn’t even get a second page of words on Dictionary.com. X also has implications as a letter word, that I’d rather avoid at the moment. 2/5.

Y: Ah, Ygreck, everyone’s favourite “what the fuck, France?” moment. Between that and being sorta kinda not really a vowel, Y prompts its own question more often than I’d care to admit. 2/5.

Z: As a (technical) member of the generation associated with this letter- on the one hand, I’m sorry, on the other, y’all have it coming. The final letter of the alphabet, one of the other ones worth 10 in scrabble (and yet X isn’t???), and one we probably got pretty sick of in the early 00s when it was everywhere- ironically, when most of the generation was getting born. 2/5.

And that’s the lot of them. I hope this didn’t alienate any non-English speakers too hard. It’s probably fine.

Join me for more bullshit next time I have another stupid idea. I mean, tomorrow.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Cinematic Legacy of Lupin: Arsène Lupin’s Live-Action Filmography

https://ift.tt/2ToNPSY

When Netflix premiered the first season of Lupin last January, 70 million sheltered-in-place households ravenously binged it, making the series the most-watched non-English show for its premiere month on the streamer so far. Lupin steals a page from French literature. The hero of Lupin, Assane Diop (Omar Sy) is inspired by France’s iconic ‘Gentleman Thief’ Arsène Lupin, a fictional figure created by French writer Maurice Leblanc in 1905.

Lupin was the subject of some two dozen books by Leblanc, who continued adding into his literary franchise until well into the 1930s. Akin to Robin Hood, Lupin stole from the rich, and often did good deeds despite his thieving capers. He was a master of deception and disguise, a lady killer who always operated with a classy panache. With a legacy spanning more than a century, there have been plenty of live-action depictions in film and TV.

The First Lupin Films are Over a Hundred Years Old

The earliest cinematic portrayals of Lupin were in black and white, and many have been lost. One of the very first was a U.S. production, a short film titled The Gentleman Burglar in 1908. William Ranows, a veteran of over sixty films, played Lupin. It was directed by one of the first film directors ever, Edwin Porter, who worked for Edison.

Leblanc was a contemporary of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes. Consequently, Holmes appears in a few Lupin stories. Doyle took legal action against Leblanc, forcing the name change in Lupin stories to the thinly disguised ‘Herlock Sholmes.’ As Holmes is loved by the British, Lupin is cherished by the French, and both characters became global icons. Consequently, among the many film and TV adaptations, several that depicted their rivalry regardless of copyright issues. In 1910, a German film serial titled Arsène Lupin contra Sherlock Holmes starred Paul Otto as Lupin and Viggo Larsen as Holmes (Larsen also served as director.) There were allegedly five installments in the series, but they’ve all been lost.

France produced Arsène Lupin contre Ganimard in 1914 with Georges Tréville as Lupin (Inspector Ganimard was constantly on Lupin’s trail). The silent film Arsène Lupin came out of Britain in 1916 with Gerald Ames in the titular role, followed by more U.S. productions: Arsène Lupin (1917) starring Earle Williams, The Teeth of the Tiger (1919) with David Powell, which is also lost, and 813 starring Wedgwood Nowell. 813 was the title of Leblanc’s fourth Lupin book.

Lupin and the Barrymore Clan of Actors

The legendary thespian John Barrymore played Lupin in 1932’s Arsène Lupin. He took on the role under one of Lupin’s aliases, the Duke of Charmerace. His brother, Lionel Barrymore, played another Lupin nemesis, Detective Guerchard. Given the illustrious cast, this is a standout Lupin film, although there isn’t a shred of Frenchness in Barrymore’s interpretation. Coincidentally, John Barrymore also played Holmes in Sherlock Holmes a decade earlier. He is also the grandfather of Drew Barrymore.

Barrymore’s Arsène Lupin revolved around the theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre. Historically, the Da Vinci masterpiece was stolen in 1911 and recovered in 1913. This inspired a Lupin short story, a parody akin to early fanfiction that was not written by Leblanc. In 1912, mystery writer Carolyn Wells published The Adventure Of The Mona Lisa which imagined Holmes and Lupin to be part of the International Society of Infallible Detectives alongside A. J. Raffles, Monsieur Lecoq, and other crime-solving luminaries. Barrymore’s Arsène Lupin does not retell this tale, but the theft of the Mona Lisa comes up again in other Lupin films because it’s France so robbing the Louvre is a common plot point. Netflix’s Lupin begins with Diop’s heist of the Queen’s necklace from the Louvre, an Easter egg referring to Leblanc’s original Lupin short story, ‘The Queen’s Necklace’ published in 1906.

The ‘30s delivered two more Lupin films. The French-made Arsène Lupin detective (1937) starred Jules Berry as Lupin and the American-made Arsène Lupin Returns (1938) with Melvyn Douglas who was credited under another Lupin alias Rene Farrand (Lupin has a lot of aliases). Despite being a completely different production, Douglas’ film was an attempt to capitalize on the success of Barrymore’s film as both films were from MGM. Universal Studios entered the fray soon after with their version Enter Arsène Lupin (1944) starring Charles Korvin. The following year, the Mexican-made Arsenio Lupin (1945) featured Ramón Pereda as the French thief. That film also starred José Baviera as Sherlock.

The Early Japanese Lupin Adaptations

Lupin captured the hearts of the Japanese. Ironically, Japanese speakers have a difficult time pronouncing ‘L’s so Lupin is usually renamed as ‘Rupan’ or ‘Wolf’ (Lupine means wolf-like – remember Remus Lupin from Harry Potter). As early as 1923, Japan also delivered a silent version of 813, retitled Hachi Ichi San, starring Komei Minami as the renamed Lupin character of Akira Naruse.

In the ‘50s, Japan produced 3 films that credit Leblanc: Nanatsu-no Houseki (1950) with Keiji Sada, Tora no-Kiba (1951) with Ken Uehara, and Kao-no Nai Otoko (1955) with Eiji Okada. However, post-WWII Japan has obscured most of the details on these films. Like Hachi Ichi San, these Japanese versions laid the foundations for the Lupin III, which debuted as a manga in 1967 and spawned a major manga and anime franchise. In karmic retribution for Leblanc poaching Sherlock, Japan stole Lupin. Lupin III was Arsène Lupin’s grandson.

Notably, the second Lupin III feature film, The Castle of Cagliostro, marked the directorial debut of famed animator Hayao Miyazaki and is considered a groundbreaking classic that inspired Pixar and Disney (Disney’s The Great Mouse Detective (1986) pilfered the finale clockwork fight from The Castle of Cagliostro). In the wake of the anime Lupin III Part I (1971), Japan produced some anime films that were more loyal to Leblanc, notably Kaitō Lupin: 813 no Nazo (1979) and Lupin tai Holmes (1981). However, this article is focused upon live-action adaptations. Lupin III is another topic entirely.

In the late ‘50s and into the ‘70s, France reclaimed her celebrated son. Robert Lamoureux became Lupin for two films, Les aventures d’Arsène Lupin (1957) and Signé Arsène Lupin (1959). A comedy version pitted rival sons of Lupin against each other in Arsène Lupin contre Arsène Lupin (1962). Playing the Lupin brothers were Jean-Pierre Cassel and Jean-Claude Brialy.

Lupin on the Small Screen

Read more

TV

From Lupin III to Inspector Gadget: Examining the Heirs of Arsène Lupin

By Natalie Zutter

France also delivered several TV series. Arsène Lupin ran from 1971 to 1974 and starred Georges Descrières. It encompassed 26 60-minute episodes. L’Île aux trente cercueils (1979) is often included in Lupin filmographies because it is based on a Leblanc novel published in 1919 in which Lupin makes a guest appearance. However, he was omitted from this six-episode miniseries, so it doesn’t quite count. Arsène Lupin joue et perd (1980) was another six-episode miniseries loosely based on ‘813’ with Jean-Claude Brialy from the 1962 comedy.

One more French TV show, Le Retour d’Arsène Lupin, was televised in two seasons, 1989-1990 and 1995-1996. These were 90-minute episodes with 12 in season 1 and eight in season 2. François Dunoyer starred as Lupin.

And in 2007, the largest Lupin TV show ran for a whopping 96 episodes plus one special. Lupin was made in the Philippines no less, starring Richard Gutierrez as André Lupin

Lupin in the Last Decade

In 2011, Japan delivered one more live-action film Lupin no Kiganjo starring Kōichi Yamadera. Based on Leblanc’s 3rd Lupin book, L’aiguille Creuse, the film is reset in modern Japan.

In the strangest permutation of Japanese Lupins, Daughter of Lupin was a TV series that is an odd hybrid of Lupin III and Leblanc’s work. A campy sitcom in the tradition of Romeo and Juliet, Hana (Kyoko Fukada) comes from a family of thieves known as the L clan who are inspired by Lupin. Her lover, Kazuma (Koji Seto), is from a family of cops. When in thief mode, Hana wears a carnival mask and a velvet catsuit. It’s goofy, sort of a live action version of anime. It ran for two seasons in 2019 and 2020.

The Lupin Adaptation You Should See

The strongest modern adaptation of Leblanc’s iconic burglar is the period film Arsène Lupin (2004). It’s an actioner, a creation story for Lupin, starting from his childhood and moving rapidly to him becoming a master gentleman thief. Romain Duris plays the titular role, and the film is in French. Backing Duris are veteran actresses Kristin Scott Thomas as Comtesse de Cagliostro and Eva Green as Clarisse de Dreux-Soubise. The story is absurd, like a mash-up between a superhero film and the DaVinci code, and it gets a bit muddled in the telling. However, it’s shot on location (including the Louvre) and encapsulates the spirit of Leblanc’s character in an updated fashion. It’s a perfect primer for Lupin Season 2.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

Lupin seasons 1 and 2 are available to stream on Netflix now.

The post The Cinematic Legacy of Lupin: Arsène Lupin’s Live-Action Filmography appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/2U0px1N

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letters of the American English Alphabet Rated by ME

A - The classic. 7/10 Not much to say here, it's usually a soft letter, good in making words sound less abrasive. Good at the beginning of a phrase/name but not very appealing. It is a vowel and starting phrased with a vowel feels weird. I gave it one extra point for being the first letter of the words ass, apple, angel, and anguish.

B - Meh 4/10 Less than average. It has terrible vibes. It’s almost uncanny. I can’t really explain it but I associate it with words like blubbery, bloat, baluga, balloon, berry(ies), and they all have a lumpy, rubbery and round look that all make me slightly uncomfortable.

C - 5/10 This letter is the bane of my existence in school. I associate it with feelings of failure even though it is not terrible to get a C. I associate it with words like: cool, clean, cock, cucumber, and conception and those are all pretty fun words which cancel out the overall negative feelings so it earns a nice average rating.

D - AW YEAH BOOOY 7/10 D is an interesting letter. I think it looks good at the beginning of words/phrases because the hump faces the way we read. One could argue the flat back is a block and makes it hard to start the word but I argue the opposite. It acts more like a gate that doesn't let you turn back, encouraging you to read further. However I am deducting 2 points from my original rating because the lowercase D is the worst letter for someone with dyslexia. I often confuse it for B and P and that is no good.

E - 6/10 A very versatile letter able to make a bunch of cool noises like E and eh and ey as well as it sounding different in different accents languages. It's the second vowel on this list meaning you can pronounce it without using anything in your mouth. The letter E is full of joke material like the meme E and puns like Eggciting. Despite this it's still a boring vowel that's hard to write in uppercase.

F - 2/10 Stupid. Fuck you. FFFFFF is such a dumb sound. And that’s the hex code for pure white which is the color of Apple™ and I hate them. F is also a boring letter that just looks like a broken E.

G - 5.5/10 Not much to say here again. I associate this letter with pirates though, and that’s cool so I’m giving it .5 points above my original rating.

H - 7.5/10 H is like the eboy of letters. If I was drawing humanized letters, H would absolutely be a scrawny white eboy, mayhaps even a Tumblr sexy man. Cool letter. I don’t ADORE it, but I like it. Hell yeah.

I - 1/10 Bane of my existence. Between I and lowercase L… This vowel is only good in words, never the beginning of words. Ice? Igloo? Insane? Stupid looking words. Terrible design.

J - 5/10 No thoughts. The only good thing about this letter that's above average is that I like writing it in cursive, that is all.

K - 3/10 I just don’t care about this letter, everything it does can be done with a C or an X. We as a society have moved the need for K.

L - 5.3/10 Just barely above average because I associate it with lovecore and I fuck heavily with it. I also enjoy how smooth of a sound it is.

M - 5/10 Smooth sounding and that's all i care about.

N - 3/10 Nothing interesting fuck you.

O - 7/10 DONUT

P - -2/10 It’s a nerdy looking letter. Pronouncing it is like trying to speak with marshmallows in one's mouth. It’s massively unimpressive and looks terrible in the front of a phrase. It feels like a fucked up vowel rather than a usable letter.

Q - 0/10 Useless letter. Can almost never be used without having a U or CK next to it. Just use C or CK, It’s so ridiculous and a waste of time. It’s also a dyslexic nightmare letter often being confused with P.

R - 6/10 I don’t know what to say I just like to rrrrrrrrrrr, but that’s it.

S - 10/10 Slithery goodness. A flexible letter that can be written in so many ways before it’s confusing! I associate it with sky, snake, slithery, soup, serendipitous, serenity, soothe and I just think these are some nice words. Drawing S’s out also makes me feel like an evil snake or a creeper.

T - 6/10 Testosterone

U - 3/10 Helpful but ugly. This letter NEVER looks good or sounds cool in anything. Unique is a dumb looking word. Unicorn is too. (No hate to those funky horses)

V - 5/10 No thoughts but fun to use as an arrow pointing down!

W - 7/10 Double U? You mean double V? Despite the stupid name for this letter I think it deserves some appreciation because without out I wouldn’t be able to express as much confusion as I can now.

X - 8/10 TWO LINES and also reminds me of pirates but for a much more obvious reason. I like pirates!

Y - 8.5/10 No thoughts, just think its stupid in a fun way.

Z - 9/10 only because it’s a super uncommon letter and when I see it I get excited.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pre-Dawn Carbonara

Sometimes One goes out One's head / Sometimes One goes mad / Sometimes One makes good with that with which One should make bad

I don't want to alarm you, pre-dawn wanderers, but I think I accidentally invented the Reverse Breakfast Asparagus Carbonara.

There was I, just picture it (and only picture it, if you please), at a simple first attempt toward carbonara. However, as you may well know of me, there is no more complexity as to how simple I can become when issued (even by self) a simple task.

(To wit: I over-complicate. Seeming to be clever, but reilly a twit, to wit (And that's all there's to it).)

Distracted by myself, as I always am, I cooked everything in reverse order, separated and beat my whites, only to scramble them back into their yolks, and throughout the pasta water, accidentally turned my sauce into eggs leavened to high heaven. The capocollo I was thawin' in a broken microwave and fryin' in a pan like I was tryin' to double-rei-cure it from dyin'. I went far past al dente with the pasta part of my repast, saving with a quick bake on a plate, dedicated to reverse-desiccate it to a past, more palatial, palate (pronounced, here, "pal-ATE") for One to eat (pronounced, here, "ATE").

I don't even remember sautéing the peppers, though they ring a bell.

As for the asparagus (as for us, I guess), it could not have turned out finer; Out-of-sight, in oven-bounds not bemoaning this One diner. Thankfully (and with one onion, on one's way) out-of-sight.

To whet, to spare us (to wit: not embarrass): breakfast was served, although be it last night.

#reversebreakfastasparaguscarbonara

Today is National Chocolate Eclair Day and National Onion Rings Day

It is NOT Discovery Day, finally. Good goddammit.

And good morning.

~

* * *

In lieu of a poem (for you, dearest reader (the only one still reading at this point)), I have especially offered here the first three chapters from a book I never finished writing entitled: How to Read: A Comprehensive Guide.

So, if you would like to spend your pre-dawn learning how to read a bit, you may do so now.

Or not. I know it's early.

~

How to Read: A comprehensive guide

First Unit

The Letters

Letter One of Twenty-Six (A a)

Pronunciation

[fig. 1], [fig. 2] As in the A in "this is how to pronounce the letter A."

[fig.3] As in "I can never remember if tall & large are the same thing when ordering coffee. Also, grande."

[fig. 4] As in the word "chat," which is the French word for "cat" and whose vowel is pronounced as that in "chat," which is the English word for "chat."

[fig. 5], [fig. 6] As in, uh, something.

~

Any alliteration assigns an author as amateurish and asinine. Also: an asshole.

~

A is a wholly unique member of the Alphabet. Not only is it the only letter whose position in the Alphabet is the same as its position in the word "Alphabet" (i.e. first and fifth), but it also begins the majority of single-letter English articles.

The primary nature of A is itself a lesson on the importance of starting things at their beginning. You will find, as you embark upon your quest for literacy, that one of the imperative strategies for reading is to read the beginning of the word first. This is key. In this spirit, our exploration of the Alphabet will commence with the first letter, A, which we have just covered.

Chapter A Exercises

1. Using what you learned in this section, complete the Alphabet:

__ B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

2. Compile a list of everyone you know whose first initial is A. Then, make a list of people whose last initial is A. Compare the lists. Doesn't the term "last initial" seem odd? I think it does.

Letter Two of Twenty-Six (B b)

Pronunciation

Like "be" without the "e" (see E).

~

B was first discovered by early etymologists 45 billion years ago (previously known as 45 illion years ago), sparking a heated fissure that created the rogue, fringe group of ex-classical etymologists, known as "ontologists."

~

There are no other facts about the letter B. This chapter is over.~Chapter B

Chapter B Exercises

1. Write a short story using the letter B as a main character. Get it published in every literary magazine in the western world. Forget your dreams of becoming literate. Revel in your fame. Recieve an offer for a movie version of the story. Make a solid bundle. Move to a house made of strong, bare wood with a grand veranda that faces west. The house is on a cool, placid lake. There is a very large bed with very fine linens. Wake each morning in it with different, multiple sex companions who show earnest interest in your story, but know only the details of the film version. Watch less and less television as you see more and more commercials for fast-food figurine toys of the characters from the movie and spend less and less time online as you notice more and more internet ads for the book-on-mp3 version of the novelization of the movie (read by the actor who played B). Wake each morning with people who know nothing of your work nor any literature, really. Begin drinking first thing in the morning. Duck calls from your publisher, from the movie people. Curse the sunset from the veranda. Throw empty liquor bottles at the lake. Fall down your hard, wooden staircase and wake hours later, bleeding, in a small pool of vomit. Wonder how it has come to this. Buy a yacht and set fire to it. Cry every day, all day, in a soft and slow way. Breathe. Dig a shallow hole in the backyard, near the water, near the ashes, and sit in it. Hug the shovel and wait for rain that will not come. Do not shiver in the cool night that beaches itself in from the lake. Breathe. Think of another story, a longer one. One about a man who has nothing and is happy. He dies at the end, in a slow and terrible way and he regrets his happiness. He denies it and then he dies. Do not commit this story to paper or memory. Forget quickly its nuance. Make a mental note to buy a gun. Breathe.

Letter Three of Twenty-Six (C c)

Pronunciation

C is pronounced like S (see ch. 19) or K (see ch. 11), as in "civic" and "coelacanth."

When C is paired with H (see ch. 8) it can have a pronunciation as in "lichen" and "chronometer."

~

While C is often referred to as the "bronze medal letter," its third-string placement in the Alphabet belies the integral role it plays in the world. Without C one couldn't comprehend. One couldn't compose. One couldn't couldn't. Without C the chaste would stop abstaining, in haste. It would be chaos, which would be haos, which is so absurd that this hapter is over.

Chapter C Exercises

1. Try to write an entire phrase without using this segment's letter. You will find that it is impossible.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Heeding the Call: Cthulhu and Japan

Depending on your interests, the name Cthulhu may stir feelings of some strange familiarity, or an excited, nearly existential sense of horror to come. Despite the fiction that birthed much of the “Cthulhu Mythos” being moderately popular, the cosmic horrors introduced by H.P. Lovecraft have morphed into a life of their own thanks to the work of his protege, August Derleth, leaving future generations to encounter the unknowable in various forms spanning video games, tv shows, movies, and perhaps the most popular forms, table-top roleplaying and board game experiences. Perhaps less well known, though, is the fact that the Cthulhu Mythos is exceedingly popular in Japan, and has a wide and exciting history of adaptations, works, and impact upon many of the genres we love in Japan to this day. Today, we’ll be taking a look and exploring that history!

The history of Cthulhu in Japan is a bit more diverse than you might initially think, and isn’t as unified as it might seem! The first bits of spreading horror came from translations of H.P. Lovecraft’s original works into Japanese in the 1940s, appearing in the horror publication Hakaba (or Graveyard) Magazine, translated by Nishio Tadashi. These early translations would prove vastly popular, and over the years ended up leading to numerous Japanese adaptations and inspirations based on Lovecraft’s original works.

Anime and manga fans are likely somewhat familiar with Kaoru Kurimoto, creator of Guin Saga, Hideyuki Kikuchi, creator of Vampire Hunter D, fan favorite horror author Junji Ito, and legendary mangaka Shigeru Mizuki, who all claimed Lovecraft as a direct influence on their works at some point. That existential, cosmic, unknowable horror is certainly present in Ito’s works like Uzumaki, and Mizuki’s interest in folklore and yokai make an attraction to the Cthulu Mythos a lot more understandable. Mizuki actually drew an adaptation of the classic story The Dunwich Horror under the title Chitei no Ashioto, simply moving the story and characters to Mizuki’s beloved setting of rural Japan.

Perhaps one of the most influential Lovecraft inspired creators in anime though is Chiaki J. Konaka, likely best known to many for his work on series like Serial Experiments Lain, Digimon Tamers, and Big O, as well as other series like Armitage III (which takes its name from a Lovecraft character!), RaXephon and Texnolyze among many others. Konaka’s career extends into the Tokusatsu side of things as well, having worked on numerous Ultraman series ranging from Tiga, Gaia, Max, and more, as well as many other series. Konaka worked in references to the Cthulhu Mythos into many of his projects, and even wrote his own short fiction; one of them, Terror Rate, was even published in English, and was even a guest of honor at the HP Lovecraft Film Festival in 2018!

Much of the spread and popularity of Cthulhu fiction in Japan is owed to a few people, one of the most notable being Ken Asamatsu. Asamatsu has spent much of his career translating and spreading Lovecraft’s works in Japan, running fanzines and other publications in order to spread his love of the existential dread universe. While Asamatsu has worked on a few manga himself, he isn’t exactly an anime or manga creator, but without his input and dedication, it is unlikely that these works would ever be as popular as they are today!

Existential, creeping, unknowable horror translates well to other mediums as well, so it should come as little surprise that video games share various callbacks and influences from the Cthulhu Mythos as well. Atlus’s Shin Megami Tensei series and its many spin-offs feature numerous callbacks to Cthulhu Mythos characters and creatures, with some of the most obvious being Nyarlathotep’s direct role in Shin Megami Tensei: Persona and Persona 2. Many of the other titles reference things like the Necronomicon, with that same text being the initial persona of Persona 5’s Futaba Sakura.

Aside from Shin Megami Tensei, there are less obvious, but somewhat hard to miss, references to many of the tropes and unique style of horror in the Cthulhu Mythos in From Software’s Demon’s Souls, Dark Souls, and most directly Bloodborne games. Demon’s Souls in particular draws heavily on the existential, unknowable horror that is descending upon the kingdom of Boletaria and the secrets behind its true collapse, and the Dark Souls games similarly feature somewhat Lovecraftian ideas and monsters. Of the three, Bloodborne is the most direct with its inspirations, with characters routinely discussing the fact that seeing more of the truth may drive one mad, cosmic entities controlling, mutating, and destroying humanity, fish people (a staple of Lovecraft’s works), and humongous, tentacle-faced monsters (here known as Amygdala).

Ironically, however, there is actually another reason for the popularity of Cthulhu Mythos in Japanese media that helped spread its flavorful influence amongst various genres, and it actually has little to do with Lovecraft’s actual writings themselves. Instead, many Japanese fans encounter Lovecraft’s elder gods through the table-top role-playing game Call of Cthulhu, first published in Japan 1986, and the explosion in popularity was not only a staggering success, but it continues to this day! Although many Western fans might assume that TTRPG games like Dungeons and Dragons are popular in Japan due to some of their influences in fantasy anime, Call of Cthulhu reigns supreme as the most popular TTRPG in Japan, and its popularity likely helped introduce many Japanese to the TTRPG genre in the first place!

Call of Cthulhu is, essentially, a group mystery adventure game, and that seems to have really hit big with Japanese audiences far and wide, because the game has remained in print since its initial introduction in the nineties, and has fans of all ages and genders playing in groups, to the point that some places will find their rooms for group meetings rented out to play games of Call of Cthulhu! Recently, the game even got some favorable air time in an NHK news segment, talking about the game itself and the fun that can be had with it! With this popularity came the growth of a somewhat unique phenomenon: Replays, essentially narrative, semi-novelized versions of Call of Cthulhu campaigns collected and printed for other people to read, similar to today’s popular “actual play” podcasts and videos such as Critical Role or The Adventure Zone. Even today, Call of Cthulhu replays are extremely popular, with new versions being printed all the time, sometimes even adorned with amazing, cute anime styled art and other interesting little design choices, like semi-doujinshi level works featuring Touhou characters, and more! These Replays became so popular that they soon spread to other types of TTRPGs, and are the inspiration behind anime such as Record of Lodoss War, Slayers, and many others!

If one were to search Cthulhu on Amazon.jp, you’d actually find that most of the results are these colorful and interesting Replay books, almost more so than you’d even find the original novels and stories by Lovecraft himself! There are many other fascinating fan inspired books about the Cthulhu Mythos, including a personal favorite of Cthulhu monsters arranged in a book similar to those of Kaiju and Tokusatsu stylings (even featuring a cartoon Lovecraft on the cover doing the famous Ultraman pose). There are other small Cthulhu publications in Japanese, include a manga anthology called Zone of Cthulhu and numerous adaptations, and Gou Tanabe’s versions are even being translated into English, with The Hound and Other Stories already available, and At the Mountains of Madness coming later this year.

Of course the Cthulhu love isn’t limited to just print media; many anime have featured some nods and callbacks to the mythos, such as in the visual novel and anime of the same name Demonbane, which is even set in Lovecraft’s beloved Arkham. Main character Kuro Daijuji works with Al Azif, the living personification of the Necronomicon, to defeat the nefarious Black Lodge (a very probable nod to David Lynch’s Twin Peaks here). As mentioned above, numerous works by Chiaki J. Konaka draw from the Cthulhu Mythos, but Digimon Tamers might be the most surprising, with callbacks to Miskatonic University and Shaggai, as well as a computer AI that seems to have more in common with the Great Old Ones than it does Skynet! Another example is a fairly popular series, Bungo Stray Dogs, where one of the characters... is actually named Lovecraft! But that's not all! His "The Great Old Ones" ability is a reference to Cthulhu's origins. Probably one of the most famous examples is Nyaruko: Another Crawling Chaos, where the monsters of Lovecraft’s works are revealed to actually be aliens, but still very weird! The anime is a comedy featuring numerous Mythos characters repurposed or slightly renamed, such as Nyarlathotep as Nyaruko, the Yellow King Hastur, and more. The series of novels proved popular enough to spawn 3 anime seasons and other spin offs, proving that even if you take the horror out of the Mythos, people will still find it entertaining and… cute?

Speaking of cute, this brings us to a few interesting final tidbits about the Cthulhu Mythos and Japan. Aside from the direct popularity, the language change and differences have led to a few running gags in Japan about the series, one of which has to do with the somewhat infamous Cthulhu cultist chant, “Ia Ia Cthulhu Ftaghn,” with “Ia Ia” being pronounced very similar to the Japanese expression “iya iya”, which has a few various uses in casual Japanese, either meaning something similar to “um” or “no” depending on how and where it is used. The second comes from the fact that Japanese, being a syllabic language, actually has an easier time pronouncing the supposedly “unpronouncable” names of the Cthulu Mythos creatures, with Cthulhu being translated as クトゥルフ, or “Kutourufu”, which is not only a lot easier to actually say, but sounds oddly cute for the sinister elder god!

Cthulhu mania seems as popular as ever both outside and inside of Japan, with new games, movies, comics, and more drawing inspiration from the titles. Although Lovecraft’s own works are less popular than when the fascination started, the current passion for his ideas stems from the attractive allure of the unknown, the potential darkness lingering in shadows and dark pools of water. Whatever the reason people flock to the Cthulhu Mythos, it seems like we can look forward to numerous adaptations, inspirations, and callbacks for years to come… until perhaps even Cthulhu awakens! Until then, it’s best to keep your wits about you and stock up on your esoteric lore… You never know where the elder gods might pop up next during your next anime, manga, or video game binge!

Have any secret and mysterious ancient Cthulhu influences we didn’t mention? Know of any other influences on Japan you’d like us to cover? Let us know in the comments!

----

Nicole is a features and a social video script writer for Crunchyroll. Known for punching dudes in Yakuza games on her Twitch channel while professing her love for Majima. She also has a blog, Figuratively Speaking. Follow her on Twitter: @ellyberries

Do you love writing? Do you love anime? If you have an idea for a features story, pitch it to Crunchyroll Features!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

fuck what youve been taught, the way we write our language has NOTHING to do with the language itself. it doesnt matter and isnt in and of itself important to uphold.

fac wat jūv ben tot, ða wej wī rajt awr lāŋgwiǧ hāz NAÞIŊ ta dū wiþ ð’ lāŋgwiǧ itsélf. it daznt mātr ānd iznt in ānd av itsélf impórtnt t’ aphóld

ooooookay so i just did this because i wanted to try coming up with my own spelling reform. going full International Phonetic Alphabet isnt practical, so i came up with this.

English has a lot of vowels, so here’s how i broke them down:

a = butt, cup

ā = bat, cap

e = bet, crept

ē = bait, day

i = bit, skip

ī = beat, keep

o = bought, cop (uhhhh sooooo this vowel is the same in my dialect. cot and caught are pronounced the same. uhhhh i never remember which is which sooooo uhhhh this is something i might wanna change. ooooorr i might make this alphabet more catered to my dialect because theres nothing wrong with different dialects having different spellings)

ō = boat, cope

u = book, put

ū = boot, coop

aj = bite, climb

oj = boy, coy

aw = cow, bow (like taking a bow and bowing, not like the thing you use to fire arrows)