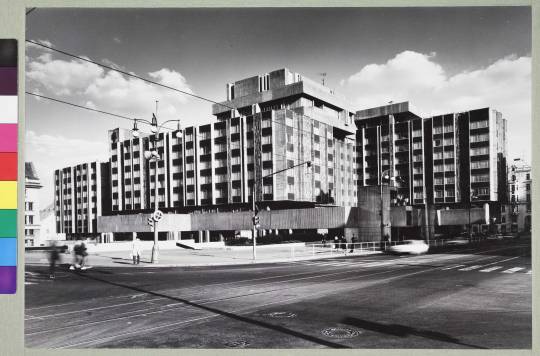

#1960's 1970's era architecture

Text

1970's era apartment building. Fully occupied. Rozelle.

#vintage#1970's#apartments#streetscape#flying balconies#facade#1960's 70's era architecture#street scene#skyline#affordable housing#inner west sydney

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Classic Rock Songs

Classic rock songs are a cherished part of music history, known for their timeless appeal and enduring popularity. Here's a brief overview of the history of classic rock songs:

Origins: Classic rock as a genre emerged in the mid-1960s and reached its zenith through the 1970s. It evolved from the rock and roll genre of the late 1940s and early 1950s, characterized by a fusion of various musical elements, including blues, R&B, and country.

The 1970s Golden Era: The 1970s witnessed a classic rock explosion with the rise of bands like Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, and Queen. Their albums and singles became anthems of a generation, defining the classic rock sound.

Subgenres: Classic rock is not limited to a single style; it encompasses a wide range of subgenres, from blues rock (e.g., Eric Clapton) to progressive rock (e.g., Yes) and folk rock (e.g., Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young).

Top Artists and their hits: Classic rock boasts a rich history of iconic bands and timeless hits. Here are some of the top classic rock bands and a selection of their most famous hits:

The Beatles: The Beatles were a British rock group that left an indelible mark on the music industry. Formed in Liverpool, England, in 1960, the band consisted of four principal members:

John Lennon

Paul McCartney

George Harrison

Ringo Starr

The Beatles grew out of a shared enthusiasm for American rock and roll. They started as a skiffle group called "The Quarrymen" and went through various name changes, including "The Beatals," before settling on "The Beatles."

Some of their hits:-

"Let It Be"

"Yesterday"

"Hey Jude"

"Come Together"

Led Zeppelin: Led Zeppelin, one of the most iconic rock bands in history, was formed in London in 1968. The group consisted of:

Robert Plant (vocalist)

Jimmy Page (guitarist)

John Paul Jones (bassist and keyboardist)

John Bonham (drummer)

The band initially came together as the New Yardbirds, with Jimmy Page being the final lead guitarist for the British blues band, The Yardbirds. However, they quickly changed their name to Led Zeppelin.

Some Of their Hits are:-

"Stairway to Heaven"

"Whole Lotta Love"

"Kashmir"

"Immigrant Song"

Pink Floyd: Pink Floyd is an iconic English rock band that was formed in London in 1965. The band gained an early following as one of the first British psychedelic groups, and they went on to become a seminal force in the world of rock music.

The original members of Pink Floyd included:

Roger Waters

Nick Mason

Richard Wright

Syd Barrett

They initially met while studying architecture at the London Polytechnic in Regent Street, London. The band's early years were marked by the leadership of Syd Barrett, who played a pivotal role in shaping their psychedelic sound. However, due to Barrett's deteriorating mental health, David Gilmour was brought in to replace him.

Pink Floyd's music journey saw them pioneer the concept album, achieving significant success in the 1970s with albums like "The Dark Side of the Moon" and "The Wall." These albums remain classics in the rock genre and are celebrated for their progressive and experimental approach to music.

Some of their greatest hits are:-

"Comfortably Numb"

"Wish You Were Here"

"Another Brick in the Wall"

"Time"

Queen: Queen is a renowned British rock band formed in London in 1970. The band was founded by Freddie Mercury (lead vocals, piano), Brian May (guitar, vocals), Roger Taylor (drums, vocals), and John Deacon (bass).

Throughout their illustrious career, Queen became known for their eclectic and dynamic musical style, blending rock, pop, and opera elements. Their music was characterized by powerful vocals from Freddie Mercury and the distinctive guitar work of Brian May.

Some of Queen's most famous songs include "Bohemian Rhapsody," "We Will Rock You," "We Are the Champions," "Another One Bites the Dust," and "Radio Ga Ga." Their 1975 album "A Night at the Opera" features the iconic track "Bohemian Rhapsody," which is often considered one of the greatest rock songs ever recorded.

Some of their greatest hits are:-

"Bohemian Rhapsody"

"We Will Rock You"

"Somebody to Love"

"Radio Ga Ga"

The Eagles: The Eagles are an iconic American rock band formed in Los Angeles in 1971. The band's founding members included Glenn Frey (guitars, vocals), Don Henley (drums, vocals), Bernie Leadon (guitars, vocals), and Randy Meisner (bass). Over the years, the lineup evolved, with members like Joe Walsh and Timothy B. Schmit joining the group.

Some of their greatest hits are:-

"Hotel California"

"Take It Easy"

"Desperado"

"Life in the Fast Lane"

These classic rock bands and their hits have left an indelible mark on the music industry and continue to be celebrated by music enthusiasts around the world. Their songs are considered classics and are frequently played on classic rock radio stations.

Check out more rock songs hits on https://musicfreak.in/classic-rock-songs-playlist/

Influence: Classic rock has left an indelible mark on the music industry and inspired subsequent generations of musicians. It remains a touchstone for artists in various genres, and its influence can be heard in contemporary rock music.

Modern Relevance: Classic rock's appeal endures in the 21st century, with new generations discovering and appreciating the genre's iconic songs. Classic rock radio stations and music festivals keep the spirit alive.

Classic rock songs are more than just music; they are a cultural phenomenon, a bridge between eras, and a testament to the timelessness of great artistry.

For More Playlists Visit our website:- https://musicfreak.in/

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pelé Will Live Forever

Pelé once confessed that he had long been troubled by a conundrum, one he’d only be able to crack when he met God, face-to-face, and could demand an explanation.

What plagued him was a feeling of dual identity: There was “Pelé,” the world’s greatest living sports legend of the 20th century, but also “Edson Arantes do Nascimento,” the ordinary guy whose job it was to watch over Pelé, shouldering the weight of his quasi-supernatural existence.

Pelé, who passed away on Thursday at the age of 82, felt, perhaps with some humor, that he was due some kind of answer as to why he had been given this double fate, upholding a godlike status in the world’s eyes, yet still feeling all too human. At his death, he wondered, who would die, given that both the incarnate demigod and the simplest of creatures coexisted inside him?

Anyone who saw him play will have no doubt God really did owe him an explanation. Pelé, the most consummate, luminous figure of perfection to ever grace a soccer field, was swept into fame at a very young age, unaware in the beginning of his own exceptionality. According to him, his most personal aim was to achieve the unrealized greatness he glimpsed in his father, who’d been an admirable but obscure player, to redeem him from a failed soccer career. Before he knew it, he was the top idol of the most popular sport on the planet, making his thunderous arrival at the 1958 World Cup, at the age of 17.

All this belongs to a bygone era of sports innocence. Soccer games were broadcast on the radio, immediately turning them into oral storytelling, steeped in legend and myth. Pelé’s career relied first on the radio and then television, cementing his fame there in 1970, when the Brazilian team captured the country’s third World Cup title. There is no visual record of much of his career, including some of his greatest goals. But throughout the 1960s, Pelé was unanimously known as the King of Soccer, bolstering his majesty with the natural nobility of someone who understood the value of his celebrity for every peasant with whom he identified.

No one else combined his speed and dribbling skills, the ability to shoot with both feet, his precise and devastating ground and aerial play, a magical sense of timing with the ball, an instantaneous understanding of what was going on around him, all grounded in a robust and rigorously balanced athleticism. Even so, the Pelé-effect isn’t just a sum, unique it may be, of quantifiable skills.

A poet once remarked that Pelé seemed to drag the field with him toward the opposing goal, like an extension of his own skin. A philosopher conceded, playfully, the possibility of glimpsing flickers of the Absolute in him. The beauty and intelligence of his body in action, plus his eagle eye and the unpredictability of his tricks, made Pelé appear to be operating on a different frequency from the other players, watching in slow motion the same game he was participating in at high speed, while others around him seemed to be doing the reverse.

The phenom was quickly discovered and embraced on every continent, long before the introduction of large-scale marketing campaigns. It’s because his existence connects with the world through a symbolic alignment of a different nature. Beyond being recognized and revered in the traditional circles of European football, this affable Black man, ambassador of a peripheral country and performing in a nonverbal language, was perceived, celebrated and loved in the most diverse corners of the world as the eloquent assertion of a grandeur greater than any political and economic supremacy.

In Brazil, Pelé’s arrival on the world stage coincided with that of the nation’s new capital, Brasília, founded in 1960, and its innovative architecture, and the success of bossa nova music. It’s been said that a goal by Pelé, one of Oscar Niemeyer’s curves or a Tom Jobim tune sung by João Gilberto were like a “promise of joy” from an exotic marginal country that seemed to be offering the world a smooth if profound passage from popular vernacular to modern art, without the costs of the Industrial Revolution. The dictatorship that followed, beginning in 1964, gave signs, recurring and persisting to this day, that this path wasn’t so direct or so simple, to say the least.

Behaving in accordance with the dictates of traditional Brazilian cordial sociability, masking insidious structural racism and social inequality, Pelé did not adopt Muhammad Ali’s swaggering rebelliousness, or the passionate, political zigzags of Argentina’s Diego Maradona, nor did he pursue the carnivalesque style and tragic arc of Garrincha, the other great Brazilian star of his generation. Instead he remained a tacit and grandiose witness of Blackness in action.

More Dionysian, politicized and mercurial than Pelé, Maradona never ceased to be Maradona, at the cost of being consumed by the flames of his glory and his downfall. By dispensing with questioning God, Maradona made himself God and his own writhing demons. Garrincha and Maradona rose and fell without ever being able to separate themselves from the experience.

Pelé, meanwhile, had Edson. Among the geniuses of our time, he is safeguarded by his double, who takes on life’s contingencies and personal dramas on a lessened scale. Even if younger generations never got the chance to go head-to-head with his magnificent, indescribable appearance on the field, thanks to his guardian angel, Pelé is spared from ruin, remaining immortal in life.

Maybe God, if He exists, will reveal this to him.

By José Miguel Wisnik (The New York Times)

#edson arantes do nascimento#Pelé#Brazil NT#seleção brasileira#Santos FC#football#fussball#fußball#foot#fodbod#futbol#futebol#soccer#calcio#José Miguel Wisnik#The New York Times#NYT

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

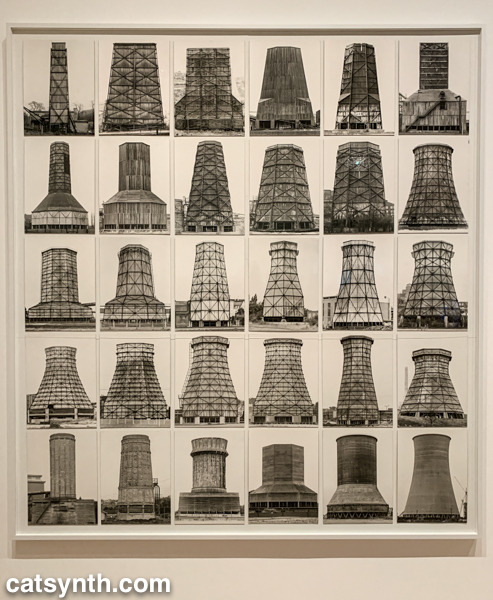

Demolitions

for Czechoslovakia’s architectures between 1960s–1980s is a controversial subject. The public may still regard it negatively, owing to a lack of information or an adverse experience with the country’s regime before the Velvet Revolution.

Omnipol Building by Zdeněk Kuna, Zdeněk Stupka, Milan Valenta, Josef Zdražil, Ladislav Vrátník (1974–1979) | Photo © Kamil Warta, National Gallery Prague

youtube

Erosion of Transgas (2020) by NGP/Loom on the Moon

Helena Doudová, the curator of the exhibition NO DEMOLITIONS! Forms of Brutalism in Prague, presents Brutalism buildings in Prague that prominently enter the urban scene. The nearly two hundred and fifty original architectural plans, photographs and models come mostly from the Architecture Collection of the National Gallery Prague. The examples of the most progressive architecture works feature the Kotva Department Store, the former Central Telecommunications Building at Žižkov (marked for demolition), the former Federal Assembly, Hotel Intercontinental and Barrandov Bridge and the recently demolished Transgas complex.

“No Demolitions!” is a quite straightforward title for an exhibition. What is happening in Prague and the Czech Republic, that led you to organize this exhibition and choose this title?

With the exhibition we intended to highlight the values of late modern and brutalist architecture in Prague that becomes either demolished or refurbished beyond the point of recognition. Some of the buildings ceased to exist throughout the one year since we started working on the topic. We intended to show that the buildings by the architects like Karel Prager, Karel Filsak, the husband-and-wife team Machoninovi and Šrámkovi have built edifices, which are comparable with the most prestigious architecture production of the former Western Europe and the US.

Center of Home Design by Věra Machoninová, Vladimír Machonin (1971–1981) | | Photo © Kamil Wartha, National Gallery Prague

The Trade Fair Palace is an exclusive choice for an architectural exhibition; why did you choose this location?

It is a building with strong symbolic meaning, a real jewel of functionalist architecture but at the same time it is difficult to present an exhibition due to technical parameters as light because paper plans and photography are very sensitive to it. The gallery floor plan worked quite well in a sequence, so the exhibition concept fit quite well. Ondřej Císler created vitrines with colored large plans and prints from the architecture collection of the National Gallery in Prague. Plans are contrasted with the photography of the deteriorated state of the buildings by Olja Triaška Stefanović.

In many countries of the former East Bloc, protecting Late Modern architecture creates a specific challenge, as these buildings are widely associated with the negative perception of the political era they were created in. This can very easily lead to iconoclastic gestures, as we have seen in the case of Skopje 2014. What can art history, museology and the wider profession do against this phenomenon?

The negative public opinion toward these buildings is a cluster of multiple problems. One general problem not only in the Central or Eastern Europe is the poor long term maintenance, which makes the buildings appear even more brutal than intended in the architecture design. As the exhibition shows, the architects were thinking of the public space around these buildings, inserted artworks and parks, as a number of designs show.

Secondly, the political associations are difficult, but also controversial to me. I very much think that the socialist state invested into large public buildings before 1989 and did provide socially accessible culture programs, sports, etc. So to me the brutalist buildings are valuable and authentic through their aim to belong to the community but also undercover propaganda. One can’t change people's memories or their experience with communism, but it’s not the fault of buildings that were ironically planned in the golden sixties in the time of the political détente in Czechoslovakia.

The exhibition | Photo © Katarína Hudačinová, the National Gallery Prague

In comparison, no large public building in Prague has been built since 30 years, what shows the shift of the capital flow with privatization. Nowadays, the real estate investors misuse the negative public opinion to demolish high quality buildings to acquire lucrative plots in the city centre for private investment. In many cases it would have been possible to reuse the brutalist buildings at a lower expense, like for example the Embassy of CZ in Berlin.

The National Gallery seems to be a prestigious place for the exhibition about the architecture of an era that is widely disputed and is also a strong institutional statement; how are Czech academics and professionals reacting to the events around the architecture of the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s?

I very much believe in the power of the exhibition as a tool for mediation and education, but also bringing up controversial or uncomfortable topics. That is the position the National Gallery has. Its architecture collection is centred around post-1945 architecture so it is logical to present it in an innovative perspective. Brutalism has received international acclaim in architecture history since 2010s, so we have had many academic discussions, but to me it is important to bring the phenomenon to the public. It is interesting that the expression is the same in former East and West, the only difference is that in the former West the buildings like the MET Breuer are celebrated, while in the former East these buildings are admired by the professionals and despised by the wide public.

In most of our countries we see the profession and the public speaking out to protect some of these buildings, in Hungary this happened by the proposed demolition of Zoltán Gulyás’ Chemolimpx office building in the early 2010s, and more recently when the government announced the demolition of Csaba Virág’s soc-hi-tech Electric Power Distribution Center. There are similar stories in Czechia and Poland - how do you explain the public being so involved in these cases?

Yes, there is an entire movement of active architecture historians, architects and interested public. David Crowley, the head of arts department of the NCAD in Dublin, is a great observer of these shifts, which demonstrate a renewal of the consciousness for public sphere and public spaces in general. So far the protests have been unsuccessful in confrontation with the investment pressures, a culmination point was the demolition of the Transgas building, public protests accompanied the demolition of Hotel Praha, and eventually rescued railway station in Havířov. Crowley says this a unique trait in Central Europe as he has not seen such engagement in the UK or Ireland. In Germany, the heritage protection of post-war buildings is really advanced by now, but there are not such strong public initiatives to me...

Transgas Complex by Ivo Loos, Jindřich Malátek, Václav Aulický, Jiří Eisenreich, Jiří Kozák, Jan Fišer (1966–1978) | Photo © Kamil Wartha, National Gallery Prague

Why did you choose brutalism as a specific style to sum up these buildings? Strictly speaking, the term is quite well defined and confined to a specific group of mostly British and American buildings, what is brutalism in your definition?

The usual association is béton brut, with the main inspiration of Le Corbusier. At the same time, I took at hand Rayner Banham, who speaks about three criteria, in short – the figure, the revealed construction and authenticity of material, which would better comply with the notion of brutalism in variety. Also brutalism has been changing from the expression of the Smithson's Hunstanton school, to let's say Paul Rudolph. In such way brutalism became an international expression with multiple specifics.

Hotel Intercontinental by Karel Filsak, Karel Bubeníček, Jiří Louda, Jaroslav Švec a kol. (1968–1974) | Photo © Kamil Wartha, National Gallery Prague

The notion of brutalism has been a subject of a dispute in the curatorial team with Petr Vorlík, Klára Brůhová (CTU Prague) and Radomíra Sedláková (NG Prague). We assumed the Czech architecture was influenced by brutalism, to a smaller or larger extent depending on every architect. Architecture of late modernism in Czech shows finer handling of material such as glass, mosaics, of wooden cladding, a variety of bright colours, that do not particularly express the notion of brutalism associated with rough concrete. The houses do in a way respect the scale of the surrounding city, are most often broken down in a composition of smaller volumes, reference bay windows of surrounding houses, etc.

PZO Centrotex Building – Václav Hilský, Otakar Jurenka (1972–1978) | Photo © Kamil Wartha, National Gallery Prague

At the same time the label brutalism is in public drawn to all kinds of buildings, which have with little or nothing to do with late modernism, actually, are clad in stone. So as architecture historians we strived to differentiate and raise public awareness on the topic.

Is there a specific Czech brutalism? Are there any national or regional characteristics in this era?

This is not an easy question. Brutalism was a global and a local phenomenon. Interestingly, in the Czechoslovak architecture we see magazines that iconic brutalist buildings were published, like La Tourette, or the architecture by Stirling in the 1960s and 1970s. So the information iron curtain was more semi-penetrable in terms of architecture knowledge and expression, like Ákos Moravánszky says. The regional specifics construction processes, the quality and variability of materials, which was lower in the former Eastern block, and also the public opinion which incorrectly associates the buildings with state socialism.

We are talking about the architectural production of an era that produced an incredible amount of buildings. How is it possible to create a canon for such a recent past and what do you think about the monumental protection regarding these buildings? What should be protected and how? Can you also name a few example, interesting buildings (and interiors) from Czechia?

A unique example is the already heritage protected Kotva Department Store by architect's team Věra and Vladimír Machoninovi.

Kotva department store in Prague. | Photo © Olja Triaška Stefanović

The former Federal Assembly is another iconic example of a daring construction originally intended for bridges. It encloses the former classical modernist stock exchange building and complements the ensemble anew. Interiors have unfortunately been refurbished and only very few items are present in the museums.

Former Federal Assembly Building Prague. | Photo © Olja Triaška Stefanović

A unique example is the Czech embassy in Berlin with intact interiors. A contested interior reconstruction is currently Hotel Thermal by Machoninovi in Karlovy Vary. At least five outstanding buildings have been demolished in Prague, countless have been refurbished. Only two above-named brutalist buildings are heritage protected, other like Hotel Intercontinental by Filsak, or Centrotex by Hiský, Motokov by Kuna should become protected as unique works of art and architecture.

___

Interview by Dániel Kovács and first published in Epiteszforum.

Photo © Jan Faukner

Helena Doudová is curator of the Architecture Collection of the National Gallery Prague. She gained curatorial and museum experience as research and curatorial fellow of the International Museum Program in the German Museum of Books and Writing in Leipzig in collaboration with the University of Erfurt and the German Federal Cultural Foundation 2016/2017, as a Robert Bosch Fellow at Architecture Museum of the TU Munich – Pinakothek der Moderne (2011–2012) and as an intern in the German Architecture Centre DAZ in Berlin (2013–2014). She initiated and curated NO DEMOLITIONS! Forms of Brutalism in Prague, Baugruppe ist super!, Image Factories: Infographics 1920-1945: Fritz Kahn, Otto Neurath. She is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Art History of the University of Zurich. She was awarded DAAD research scholarship and Aktion Österreich scholarship.

***

NO DEMOLITIONS! Forms of Brutalism in Prague

From 6.3.2020 to 22.11.2020 at the Trade Fair Palace – 3rd floor

Dukelských hrdinů 47, 170 00 Praha 7 Map

Curator: Helena Doudová

Collaborating experts / co-curators: Klára Brůhová (FA CTU in Prague), Radomíra Sedláková (NGP), Petr Vorlík (FA CTU in Prague)

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here are some of my takeaways from the Lecture 1 in Brief Introduction to Software Development.

Colossus, 1994

World’s first programmable, electronic digital computer.

Programmed by switches and plugs not by stored program.

Prototype Colossus Mark 1, was shown to be working in December 1943, was in used of Bletchley Park early 1944.

It is also used in WWII to decipher codes from Germans.

Made by British.

In today’s software it is called the encryption/ decryption utility program.

ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer)

First programmable general purpose digital computer, 1946.

It can program to work in many functionality.

Jon Von Neumann (machine)

Architecture of today’s computer

Stored programs

Smartphone

Architecture is based on John Von

Supercomputer

Parallel computers

FORTRAN

Use to create simply programs

1st successful programming language

FORmula TRANSlation- designed by JOHN BACKUS in 1956

It took 18 years to finish

The resulting compiler remained to be the best optimizing compiler for many years.

FORTRAN I- FORTRAN IV, FORTRAN 66, FORTRAN 77, FORTRAN 90, FORTRAN 95

Intended for engineer and scientific

John W. Backus

1953

IBM

Altair Computer

1st personal computer

N. Wirth

1950’s period essential to era of computing

Invented the POSAD

Microcomputers first appeared on the market in 1975 (Commodore, Tandy, and Apple; much later, IBM entered the market)

Software

Interface between computer systems and the humans. Consists of programming instructions and data that tell the computer how to execute various task.

Today, higher- level languages are written for easier to human programmers converted into low- level machine code that computer understand.

First piece of software was written by computer scientist Tom Kilburn on June 21, 1948.

Kilburn & Freddie Williams built one of the earliest computer, the Manchester Small- Scale Experimental Machine (SSEM) (“baby), SSEM was programmed to perform Mathematical Calculations using machine code instructions.

Computers were programmed with punch cards in which holes denoted specific machine code instructions.

Fortran, one of the very first higher- level programming language, published 1957.

Statistician JOHN TUKEY coined the term “software” in the article about computer programming.

Other programming language FORTRAN, COBOL, Basic Pascal, and C arrived over the next decade.

Personal Computer Era

1970’s and 1980’s software hit the big time with the arrival of personal computers.

Apple released the Apple II, its revolutionary product to the public April 1977.

Visicals/ Spreadsheets software for personal computing, was wildly popular and known as the Apple Killer App. Software was written in specialized assembly language and appeared, 1979.

IBM entered the market with computers used as IBM pc, launched 1981.

Open Source Software, major innovation in the history of software development, first entered the mainstream 1990’s, used by the Internet.

Linux kernel, the basis for the open source, Linux OS, 1991.

Interest in open- source software spiked in the late 1990s, after the 1998 publication of the source code for the Netscape Navigator browser, mainly written in C and C++.

Noteworthy is the release of Java Bean Sun Microsystem in 1995.

Software Development Today

Software Engineering

Term “programming” commonly use through the mid- 1960’s and referred essentially to the task of coding a computer.

“Software engineering”- referring to the highly disciplined, systematic approach to software development and maintenance- NATO- sponsored conference, 1968.

In the conference, the difficulties and pitfalls of designing complex systems were explored in depth. The prominent tools were languages reflecting procedural, modular and object- oriented styles of programming.

Software History

Martin Campbell- kelly

So here are all the notes that I jotdown.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hey! I am a Volturi S T A N and I really enjoy how cultured they are. They’ve had enough time to study every era in art intensively, and I wonder what their favorite would be. From Ancient to Romanticism, what era in art is the favorite of each Volturi guard?

Welcome fellow stan! Sorry this took longer than expected! I’ve taken a lot of art history courses so I probably gave this more thought than necessary! Also I went more with art styles rather than time periods, because that just seemed to make more sense to me. Hope that’s okay!

Aro - You’re asking Aro to choose just one art style? Not going to happen. He’s collected art from everywhere and everywhen will insist that all of it has equal artistic merit. Yes even that broken new-age art mobile made of paper mache and plastic straws stuffed in the corner behind one of Botticelli’s angel paintings.

Marcus - Without Didyme, he’s got a maudlin streak. So he’s quite into vanitas paintings, and Gothic Architecture. Mostly, he prefers history to art, however.

Caius - He prefers art that is technically impressive and realistic as possible. For this reason, Realism has a strong appeal. Scientific drawings also fascinate him. He’s got a large collection of “undiscovered” Michelangelo’s. He also prefers technically impressive Baroque music. And minimalist architecture. But he has absolutely no understanding of or interest in heavily abstracted styles, like Impressionism, Cubism, and thinks most modern art is a phenomenal waste of time. It’s his most common argument with Aro, outside of official business.

Sulpicia - Has a strong preference for female artists, especially those who depicted women being violent. Style isn’t especially important. Her favorites include Minoan bullfighters, a lot of angry women in the 1970s/1960s and Artemesia Gentileschi. She’s also big into fashion and makeup. A choker of pearls, blood-red lipstick and eyeliner sharp enough to kill a man are her go-tos.

Athenodora - She’s more into poetry than pictures and sculptures. She especially likes poetry that’s flowery, but has a rigid structure. Free-form poetry is for the weak. Haikus, Greek Dramas, and iambic pentameter are where it’s at. She’s also got a fondness for plays, Shakespeare, of course, but also Opera, Kabuki theater, and modern musicals. She drags Caius along whenever she can, and he not-so-secretly enjoys it.

Didyme - (She’s still alive, dammit). Art to her is about emotion. If it doesn’t make her feel something, why make it? She especially loves the colors in Impressionism. But also has a fondness for abstract geometric patterns and loud, splashy Modernist art. Like her brother, her tastes clash horribly, and any room decorated by her is an absolute eyesore. Marcus (who thinks it’s kind of adorable) is good-natured about it. And he’s a bit less grim with her around.

Alec - That picture of George Washington riding a T-Rex and wielding a light-saber while wearing 3-D glasses just about sums up what Alec likes. He’s 12, so add enough flames, guns, robots and lasers and he’ll love it.

Jane - Medieval art. It’s what she grew up with. But it’s also pretty grotesque at times (we’ve all seen those medieval art memes, right), and strikingly pretty on other occasions. Which suits her. Also, all the paintings/tapestries depicting witch burnings are good motivation.

Heidi - She’s got a sense of humor, so she likes the Rococo Era. Not so much the architecture styles, or the dresses–that’s more Aro’s speed–but she likes how most people look at the paintings (like this one) from the era and just see a bunch of fancily dressed people and completely miss all the innuendos. They certainly go over Felix and Demetri’s heads, and that’s the way she likes it.

Demetri - Art Deco. It’s clean, sharp, angular, stylish. He loves it as an art style, as an architecture style, and if he could get away with it, he’d wear 1920s tuxes all the time too.

Felix - Roman art and especially Roman Architecture is Felix’s favorite. So stately and strong–like he is. He kind of wishes the Volturi fortress was built a little bit more like a Roman temple than a labyrinth of sewers, but he gets why it has to be that way.

Renata - Music is more her forte than painting or sculpture. And, while it’s hard to compete with Aro, who can learn new instruments just by touching a virtuoso, she’s gained proficiency in the harp, the flute, the cello, and the piano. She also sings. But never anywhere she thinks someone else can hear her. Of course, thanks to super-vampire hearing, they all can. And they think her singing voice is lovely. But they know she would die of embarrassment if they admitted they could hear, so they never tell her.

Corin - Prefers embroidery and hand-sewing to most other arts. She also took up knitting and crochet. And prefers to make things with flowers on them. She also likes literature, especially those by women authors, like the The Tale of Genji, the works of Jane Austen, Eileen Chang, and many anonymous women writers.

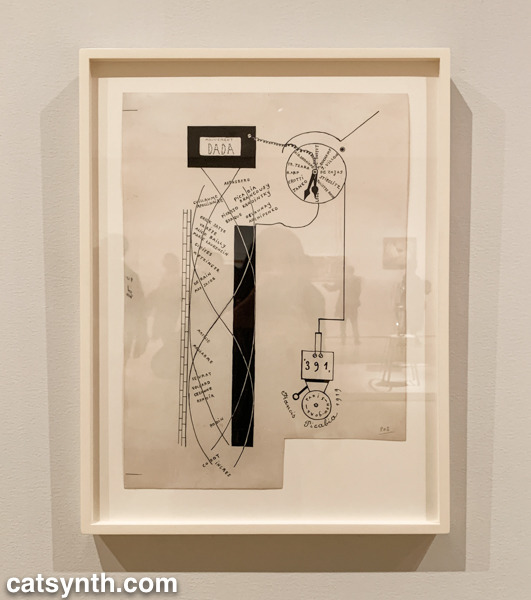

Santiago - Dadaism, Surealism and especially Salvador Dali, whose political paintings greatly influenced his country while he was human.

Chelsea - Art has never been the reason why she’s part of the guard. To her it’s eh… okay. Which was always a source of frustration for Aro when he tried to pamper her with gifts. “What do you mean you ‘don’t like paintings’? You cannot simply dislike all paintings?” But it got even worse when Afton arrived.

Afton - Doesn’t understand art at all, and it’s one of the many reasons Aro hates him. You see, Afton was born after the invention of the camera and thinks realistic art is a waste of time (why not just take a picture?) and abstract art is just pointless splatters that any child could replicate. Oh, and cartoons are only for children. All of which he’s managed to get Chelsea to believe too.

Yeah….

He does appreciate practical art like pottery. But he refuses to call it “art” and insists it’s like furniture, which he claims is somehow different. (hint: it’s not!)

#volturi#volturi headcanons#twilight#twilight saga#the whole gang is here#aro volturi#marcus volturi#Caius Volturi#afton volturi

68 notes

·

View notes

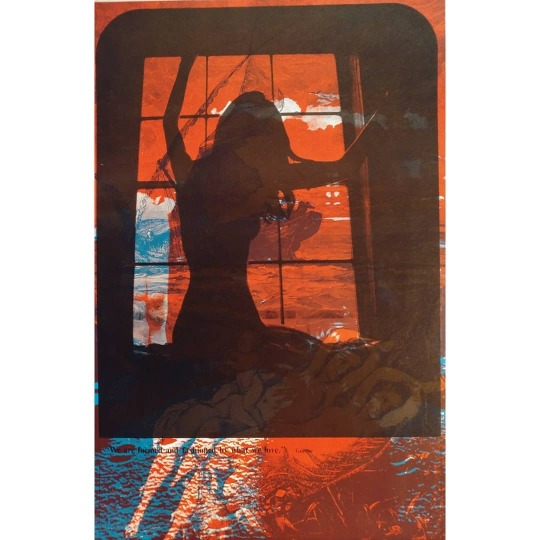

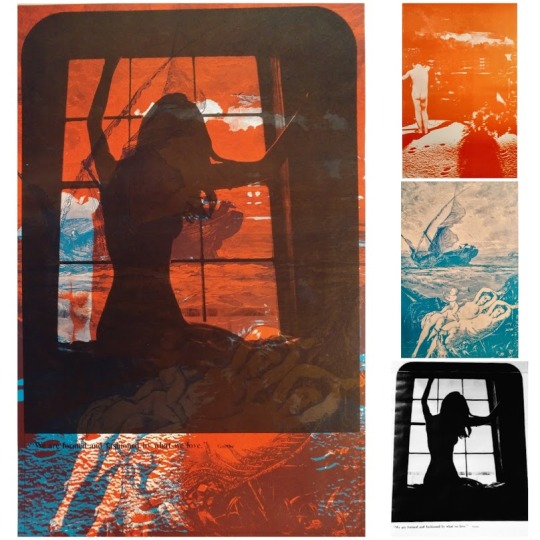

Photo

Original 1970 offset lithograph from artist Sätty printed over photo of Nude Woman In Window by Mike Powers, designed by Dale Smith above quote from Goethe: "We are formed and fashioned by what we love." Celestial Arts CA86 Orbit Graphic Arts, a poster printing company based out of San Francisco during the 1960s/1970s, distributed this overprinting by Sätty who was famous for creating mind-blowing and now highly collectible collages, having been exhibited at the MoMA, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, San Francisco Museum of Art and several other major museums listed below. If you look at the last photo, you'll see two of the base images (both available for purchase if interested) over which he would print layers of other illustrations. www.etsy.com/shop/BillsArchives One of the better-known poster artists when the psychedelic era was in full flower in the 60's, Wilfried (Wilfred) Podriech, also known as Sätty, was as much a part of the scene as Dr. Hip or the Grateful Dead. For a few years, his life had been one long summer of love. He staged huge parties where socialites and hippies mingled, in a subterranean basement of the pre-earthquake building where he lived on. He was schooled in architecture, engineering and design, and spent some time working in Brasilia before he settled in San Francisco in the early 60's. It was the threshold of the psychedelic era, and Sätty soon began making posters, developing an extraordinary collage technique that brought together both the technological and surreal sides of his background. Drawing from his enormous collection of 19th-century illustrations, and using his knowledge of overprinting, collage, overlays, paints and offset lithography, Sätty superimposed and juxtaposed images to create layered compositions of such wildness, density and subtle detail that they speak more tellingly than any static visual records of the time could do. His transformations of the original materials range from the discreet addition of a few whimsical oddities in the foreground of an etching, to the full-out hallucinations of an opium den or a ballroom swirling with romantic delirium. And the fact that these are all 19th-century images, radically revised by a 20th-century eye, gives one the eerie sense of shifting back and forth in time, space and perception. There's a startling sardonic humor in Sätty's visionary history, but there is love as well for the reckless, plunging voracity of those early days. EXHIBITIONS One Man Shows: • Moore Gallery, San Francisco; 1968. • Berkeley Gallery, San Francisco; 1970. • Goethe Center, San Francisco; 1971. Group Shows: • San Francisco Museum of Art; 1967. • Moore Gallery, "Second Joint Show", San Francisco; 1968. • Museum of New York City; 1969. • Boston Museum of Fine Arts; 1969. • Sun Gallery, San Francisco; 1969-1971 • National Museum of Art, Belgrade, Yugoslavia; 1970. • National Museum, Warsaw, Poland; 1970. • Gary Standiford Gallery, San Francisco; 1970-1971. • Richmond Art Center, California; 1971. • Museum of Modern Art, New York; 1971. • Arts and industry exhibition, San Francisco; 1971. • Dr. Reidar Wennesland Art Collection (public Exhibition), San Francisco; 1971. • Gallery: The Poster (with David singer), Los Angeles; 1972. • Kristiansand Art Association, Norway; 1972. • The Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco; April-June 1975. GUEST LECTURES • The artist's studio, San Francisco; 1970. Lecture for members of the Society for the Encouragement for Contemporary Art concerning "Art and the Electronic Media". • Berkeley Gallery, San Francisco; 1971. Lecture about the artist' work for members of the San Francisco Museum of Art. • San Francisco Art Institute; 1971 and 1974. Two lectures in printmaking and one lecture for students at the artist's studio. • College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland; 1974. Lectures on "Photo and Printmaking" with slide show. • San Francisco State University, Art Department; 1974. "Imagination vs. Media" with slide show. • San Francisco Museum of Art; 1974. "Media and Poster Art" with slide show. • San Francisco State University, Literature Department; 1975. "Composition" with slide show. PUBLISHED ILLUSTRATIONS Washington Post (Book World- syndicated Sunday supplement) 1973-1975- nine illustrations. • Rolling Stone (26 issues) 1969-1975. • Berkeley Barb, 1969. • East Village Other, 1969. • Organ (7), 1970. • Oz Magazine, England (3 issues), 1971-1974. • Clear Creek (10), 1971-1972. • KPFA folio, 1971-1972. • Ramparts (4), 1972. • Communication Arts Magazine (2), 1972. • Sunday Paper (illustrated in collaboration with David Singer), 1972. • Equilibrium (5), 1973. • Video City- Radical software (2), 1973. • Living Daylights, Australia (2 illustrations from "Time Zone", 1974. • Village voice, 1975. COVER ART • Washington Post (book World syndicated Sunday supplement, 1973-1975: The Sovereign State of ITT, by Anthony Sampson. Gravity's Rainbow, by Thomas Pynchon. Through Russian Eyes, by Anatolii Gromyko. Richie, by Thomas Thompson. Before Civilization, by Colin Renfrew. The Clockwork Testament, by Anthony Burgess. • California Living, Los Angeles, 1969. Two color posters as part of cover. • The East Village Other, New York, 1969. • Berkeley Barb, Berkeley, 1969. Two covers • KPFA Folio, Berkeley 1972. • Publisher's Weekly, New York, April 1975. • The San Francisco Sunday Examiner And Chronicle, 1975. RECORD ALBUM COVERS • "GHANDARVA", Beaver and Kraus; Warner Bros., 1971. Five color cover with David Singer. • "The Occult", United Artists, 1973. A variety of interviews and music. Color cover and back plus 1 color and 12 black and white illustrations in booklet explaining the album. • "The Miraculous Hump Returns from the Moon", The Sopwith Camel, Warner Bros, 1973. • "Feel", George duke, MPS Records, 1974. Separate European release, MPS Records , 1975. • "The Aura Will Prevail", George duke, HPS Records, 1975. BOOKS • The Cosmic Bicycle: Straight Arrow Books, San Francisco, 1971. Limited hardbound edition, regular softbound edition. 160 9"x 12" pages. 79 black and white and 8 four color illustrations. Four color cover and back. • Time Zone: Straight Arrow Books, San Francisco, 1973. 9" x 12" softbound edition, 160 pages, 84 black and white illustrations. Three color cover and back. ISBN: 0879320281 0879320672 (pbk.) BOOK ILLUSTRATIONS AND COVERS • Biafra Good-bye, 1970 • Rolling Stone Book of Days, 1970-71 • One Eighty Five, 1973 • The Axis of Eros, 1973 • Madness Network News Reader, 1974 • Monsters, 1974 • The Index of Possibilities-Energy and Power, 1974 • The Rainbow Book, 1975 • The Annotated Dracula, 1975 • The Hashish Eater, 1975 • The Illustrated Edgar Allan Poe 1976

#Satty#Mike Powers#Dale Smith#Celestial Arts#Orbit Graphic Arts#Goethe#Psychedelic Posters#PsychedelicArt#lithograph#collage#Wilfried Podriech#Wilfred Podriech#Sätty#museum collection#museum collections

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Corfu old town.Ionian sea,Corfu island.Greece.

Contax RTS II,Carl Zeiss lenses T*,Sony A 900,Sony lenses,Sony RX10

Powered by Dell

Corfu or Kerkyra Greek: Κέρκυρα, Ancient Greek: Κόρκυρα,Latin: Corcyra; Italian: Corfù) is a city and a former municipality on the island of Corfu, Ionian Islands, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it is part of the municipality of Corfu island. It is the capital of the island and of the Corfu regional unit. The city also serves as a capital for the region of the Ionian Islands. The city (population 24,838 in 2011) is a major tourist attraction, and has played an important role since antiquity.

The ancient city of Corfu, known as Korkyra, took part in the Battle of Sybota which was a catalyst for the Peloponnesian War, and, according to Thucydides, the largest naval battle between Greek city states until that time. Thucydides also reports that Korkyra was one of the three great naval powers of fifth century BC Greece, along with Athens and Corinth. Medieval castles punctuating strategic locations across the city are a legacy of struggles in the Middle Ages against invasions by pirates and the Ottomans. The city has become known since the Middle Ages as Kastropolis (Castle City) because of its two castles.

From 1386 to 1797, Corfu was ruled by Venetian nobility; much of the city reflects this era when the island belonged to the Republic of Venice, with multi-storied buildings on narrow lanes. The Old Town of Corfu has clear Venetian influence. The city was subjected to four notable sieges in 1537, 1571, 1573 and 1716, in which the strength of the city defenses asserted itself time after time, mainly because of the effectiveness of the powerful Venetian fortifications. Will Durant claimed that Corfu owed to the Republic of Venice the fact that it was the only part of Greece never conquered by the Ottomans.

In 2007, the old town of the city was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The municipal unit of Corfu city has a land area of 41.905 km2 (16.180 sq mi) and a total population of 39,674 inhabitants.

The old fortifications of the town, formerly so extensive as to require a force of from 10,000 to 20,000 troops to man them, were in great part thrown down by the British in the 19th century. In several parts of the town may be found houses of the Venetian time, with some traces of past splendour. The Palace of St. Michael and St. George, built in 1815 by Sir Thomas Maitland (1759–1824; Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands) is a large structure of white Maltese stone. Near Gasturi stands the Pompeian style Achilleion, the palace built for the Empress Elizabeth of Austria, and purchased in 1907 by the German emperor, William II.

Of the thirty-seven Greek churches the most important are the cathedral, dedicated to Our Lady of the Cave; St. Spiridon's, with the tomb of the patron saint of the island; and the suburban church of St Jason and St Sosipater, reputedly the oldest in the island. The city is the seat of a Greek and a Roman Catholic archbishop; and it possesses a gymnasium, a theatre, an agricultural and industrial society, and a library and museum preserved in the buildings formerly devoted to the university, which was founded by Frederick North, 5th Earl of Guilford (1766–1827, himself the first chancellor in 1824) in 1823, but disestablished on the cessation of the British protectorate.

Based on the ICOMOS evaluation of the old town of Corfu,it was inscribed on the World Heritage List. The ICOMOS experts have noted that "about 70% of the pre-20th century buildings date from the British period" and that "whole blocks were destroyed" in the Old Town by the German World War II blitzes; these were "replaced by new constructions in the 1960s and 1970s". The urban fabric was classified as being predominantly of the Neoclassical period "without special architectural features for which it could be distinguished".

The town of Corfu stands on the broad part of a peninsula, whose termination in the Venetian citadel (Greek: Παλαιό Φρούριο) is cut off from it by an artificial fosse formed in a natural gully, with a salt-water ditch at the bottom, that serves also as a kind of marina known as Contra-Fossa. The old city having grown up within fortifications, where every metre of ground was precious, is a labyrinth of narrow streets paved with cobblestones, sometimes tortuous but mostly pleasant, colourful and sparkling clean. These streets are called "kantounia" (καντούνια) and the older ones sometimes follow the gentle irregularities of the ground while many of them are too narrow for vehicular traffic. There is promenade by the seashore towards the bay of Garitsa (Γαρίτσα), and also an esplanade between the town and the citadel called Liston (Λιστόν) where upscale restaurants and European style bistros abound. The origin of the name Liston has several explanations: many former Venetian cities have a square of that name, coming from a Venetian word meaning evening promenade, but it can also refer to the closed-list aspect of an up-scale area reserved to the nobility registered in the Libro d'Oro.

The citadel was depicted on the reverse of the Greek 500 drachmas banknote of 1983-2001.

The city of Corfu has a long tradition in the fine arts. The Philharmonic Society of Corfu is part of that tradition. The Museum of the Philharmonic Society of Corfu presents in detail the musical heritage of the island .

#Corfu Island#corfu old town#medieval#historical#culture#angevins#italy#great britain#ottomans#music#philarmonics#castles#fortresses#urban exploration#island#greece#ionian sea#french#russians#old city#architectural#architecture#gardens#palaces#ancient greece#byzantines#photography#architectural photography#sonyphotography#dell

1 note

·

View note

Text

Lecture 1: What is Contemporary Art?

The outcomes for this lecture were to: understand the term ‘contemporary’ in the art world, what factors can be linked with contemporary artwork and finally to explore some practitioners and movements within contemporary art.

According to Tate, the term means: “...contemporary art is loosely used to refer to art of the present day and of the relatively recent past, of an innovatory or avant-garde nature.” However, my take on the subject is that at one point in time, all works of art were once contemporary. It is generally agreed that Contemporary Art started around the 1960s and included many movements within.

A Timeline of Movements:

· Early 1950’s- Word Art

· Mid 1950’s- Pop Art

· Late 1950’s- Minimalism

· 1960- Fluxus Movement

· 1960’s- Conceptualism

· 1960’s- Photo- Realism

· 1960’s- Installation

· 1960’s- Body Art

· Late 1960’s- Feminist Art

· 1965- Video Installation

· 1966- Supports/ Surfaces

· 1966- Post- Minimalism

· 1967- Arte Povera

· 1969- Projection Art

· 1960’s-1970’s- Earthworks

· Early 1970’s- Contemporary Realism

· 1970’s- Graffiti Art

· 1970’s- Performance

· 1976- School of London

· Late 1970’s- Transavanguardia

· 1980- Contemporary Photography

· Early 1980’s- Neo- Expressionism

· Early 1980’s- Computer Art (Digital)

· 1980’s- Neo- Pop

· 1988- Young British Artists (Britart)

· Late 1980’s- Deconstructivism

· 1990’s- Cynical Realism

· 1990’s New Leipzig School

· 1999- Stuckism

After reading Smith’s ‘What is Contemporary Art?’, I have come to my own conclusion that there is in fact no actual answer as it is so fluid, includes so much different media, more about the concept and you can never be wrong.

I came into the session with a pessimistic attitude since I am not the biggest fan of Contemporary Art, however, after researching about Ryan Gander, I have started to change my opinion. Since 2003, Gander has produced an immense amount of work in multiple forms: sculpture, writing, painting, architecture, clothing, installation and performance. The artist also curates’ exhibitions and presented television shows for the BBC. He is described as a conceptual artist but rejects the term as he sees himself as more of a ‘Proper-Gander-ist’. My favourite piece by Gander is ‘I…I…I…’ which is an animatronic mouse with his head poking through a wall. Scattered along the floor are pieces of plaster and dust. When near the mouse, you can hear him trying to say a speech; it is his 9-year-old daughter who did not really know what to say. I like this installation as it is an interactive piece and you can feel like part of the artwork, I also enjoy how Gander does not take himself or his art too seriously and wants the audience to have just as much fun as he is having.

This introductory lecture presented so many eras of art that I had no idea were influenced and incorporated within contemporary art, all the way from the ‘50s to the ‘90s. Alongside researching Ryan Gander, this discovery of new movements completely altered my opinion of Contemporary art to something more positive as now I know how much influence it has had on art overall.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Designer George Nelson: Well Ahead of the Parade

"You don't think your way to creative work. You work your way to creative thinking.” --George Nelson

George Nelson’s Early Years

George Nelson was born on May 28, 1908 to Simeon Nelson and Lillian Canterow Nelson in Hartford, Connecticut, where his parents owned and operated a drug store.(1) His early childhood was uneventful. As a young man, Nelson sought “refuge in Yale’s architecture school during a rainstorm, he quickly found himself entranced by the student work on display” Nelson then decided to study architecture at Yale University. He began his studies in 1924 and “graduated with a degree in architecture [in 1928]. In 1929, Nelson was hired as a Teacher's Assistant while pursuing his second bachelor's degree [in Fine Arts] at Yale” (1). He earned that degree in 1931.(2)

George Nelson Goes Abroad

The following year, “Nelson competed for and was awarded a Rome Prize, which provided a two-year stipend to study at the American Academy in Rome, where he lived from 1932–34” (3). During his studies in Europe Nelson had the opportunity to interview Europe’s leading architects, including Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and Walter Gropius among others. During his interview with Mies van der Rohe, the architect asked Nelson for his thoughts on Frank Lloyd Wright’s work. Nelson was embarrassed to admit that he was not familiar with Wright. (1)

During his stay in Rome, George Nelson married Francis Hollister. The couple returned to the United States in 1935. (1) “By [then] Nelson was an associate editor of the magazines Architecture Forum and Fortune, and the next year he was running his own architectural practice in New York with William Hamby” (3). Nelson and Hamby collaborated on a home for “inventor and industrialist Sherman Fairchild, [which] was one of the first modernist townhouses in New York” (2). The structure is set off from the other brownstones around it by its modernist façade, and it features an innovative floor plan. Nelson and Hamby’s firm closed in 1942 at the start of World War II. For the duration of the War, Nelson continued to write about architecture and design. (1)

Nelson’s writing brought him into contact with the innovative designers Eliot Noyes, Charles Eames, and Walter B. Ford.(1) During the war Nelson taught architecture at Columbia University in New York City. In 1941 he became a “member of the Architecture Committee of the Museum of Modern Art [in] New York” (4). Nelson and architect Henry Wright collaborated on the Storagewall concept and in the same year published the book Tomorrow’s House.(4) In 1942 Nelson originated the concept of “Grass of Main Street” that eventually “evolved into the [open-air] pedestrian mall” (2).

George Nelson Joins Herman Miller

Nelson’s articles on design “came to the attention of D.J. De Pree, president of the Michigan-based furniture manufacturer Herman Miller” (3). Nelson designed his first collection for the firm in 1945 and was named their design director in 1947. De Pree referred to Nelson as “as someone ‘thinking well ahead of the parade’” (3). While at Herman Miller Nelson not only was responsible for designing many of the firm’s most popular furniture he, also recruited some of the most outstanding design talents of his time, “including Charles and Ray Eames, Alexander Girard, Isamu Noguchi” (2) and Harry Bertoia. (1) Nelson’s most iconic work for Herman Miller was the Platform Bench (1947), the Bubble Lamp (1952), the Marshmallow Sofa (1956), and the Swaged-Leg furniture line (1958). (2)

George Nelson, Platform Bench (1947). Image source.

George Nelson Associates is Established

With money earned at Herman Miller, Nelson opened a design studio in New York City in 1947.(1,2) In 1955, Nelson “incorporated it into George Nelson Associates, Inc.” (1), and although Nelson had by this time left Herman Miller, his design firm continued to consult with the company. During this time Nelson was also “regularly [serving] as an editor for Interiors” (2). At his own firm, as he had done at Herman Miller, Nelson continued to employ the top designers of the era, “Irving Harper, George Mulhauser, Don Chadwick, Bill Renwick, and John Pile” (1) among many others. George Nelson Associates took a pioneering holistic approach to design with the “the practice of corporate image management, graphic programs, and signage” (1). An excellent example of this approach is the work the firm did for the pharmaceuticals manufacturer Abbott during the mid-1950s.(2) The company continues to use the original corporate logo today, and it looks as contemporary as ever.

George Nelson, Bubble Lamp (1947). Image source.

Nelson’s Bubble Lamp

In 1947 Nelson became obsessed with a spherical Swedish lamp he had seen. He badly wanted one for his design studio, but the $125 price tag was too dear. He set about designing a spherical lamp of this own. He recalled seeing “a newspaper photograph...a fleet of ships being sprayed with a self-webbing plastic for preservation during storage” (5). What if he could design a metal frame onto which this plastic material could be sprayed? By the next day, “he had crafted a spherical metal frame and tracked down the maker of that spiderweb-like plastic” (5). In 1952 Bill Renwick a designer working for George Nelson Associates refined the lamp design which was manufactured by the Howard Miller Clock Company (not to be confused with Herman Miller). In 2016, Herman Miller obtained the rights to sell the Bubble Lamp, and it remains popular as well as affordable. Designer Johnathan Adler said of the Bubble Lamp, “It’s an atomic take on a Japanese paper lantern” (5).

American National Exhibition in Moscow

Nelson was commissioned by the United States in 1959 to design a pavilion for the American National Exhibition in Moscow. The pavilion incorporated one of the earliest uses of large multi-screen presentations. The pavilion, however, became historic not so much for Nelson’s forward-thinking designs, but for being the site of Richard Nixon and Nikita Khrushchev’s ''kitchen debate'' (4).

Having divorced Frances Hollister, that same year George Nelson married Jacqueline Griffiths in 1960.(2) Not much is known about the circumstances surrounding the disintegration of the marriage to his first wife, nor are there details regarding his relationship with Ms. Griffiths.

George Nelson and Robert Propst, Action Office 1 Credenza with shelves (1964). Image source.

George Nelson and the Action Office

“In 1960 Herman Miller created the Herman Miller Research Corporation under the direction of Robert Propst, and the supervision of George Nelson” (1). The purpose of the research firm was to study changes in the workplace that had taken place in the Twentieth Century and in particular how the use of office furniture evolved with these changes. “After consulting with experts in psychology, anthropology, and various other fields, Propst created the Action Office I line which was executed by” (1) George Nelson Associates. The Action Office I line was introduced in 1964, but was not successful.(6)

Nelson and Propst disagreed on the best environment to “best suit a corporate office worker” (6), so “Nelson was removed from the project” (1). Nelson’s departure allowed Propst to explore his concepts of an office space that could be modified without costly renovations. “Action Office II was based around the mobile wall unit that defines space” (6); it has become commonly known as “the cubicle” (1,6). Unlike Action Office I, the subsequent line was a resounding success. Nelson, however, always renounced the project. In 1970, he sent a letter to Herman Miller's then Vice-President for Corporate Design and Communication, Robert Blaich, deriding the dehumanizing effect of the Action Office II, which allows the office planner to pack the greatest numbers of employees in the smallest amount of space.(5)

A desk inspired by George Nelson and Robert Propst’s Action Office I Collection for Herman Miller (left) used in a set from Stanley Kubrick’s film, “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968). Image source.

George Nelson’s Influence and Legacy

In addition to George Nelson’s iconic, innovative furniture designs, he had the ability to recognize and nurture great talent in other designers. As mentioned earlier, he collaborated with designers Charles and Ray Eames at Herman Miller, and after Nelson opened his own studio, hired many designers whose work for George Nelson Associates would become iconic. Nelson’s “skill as a writer helped legitimize and stimulate the field of industrial design by contributing to the creation of Industrial Design Magazine in 1953” (1). Nelson also served as editor-in-chief of Design Journal from 1968 to 1973.(2) In 1977, he published the groundbreaking book How to See. Designer “Ralph Caplan, said, ‘He was quickly identified by all industrial designers who could read and write that he was better able than anybody to express what they did for a living and why it was important’”(4).

George Nelson Associates, Inc. for Herman Miller, attributed to Irving Harper, Marshmallow Sofa (1956). Image source.

Accolades for George Nelson

George Nelson was “named a fellow of the Industrial Designers Society of America” (2) in 1966 and made a member of the organization’s board in 1969. The following year Nelson became an Honorary Fellow of the American Institute of Interior Design. He also served as a visiting lecturer at Harvard University in Boston and as a visiting professor at the School of Architecture, at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NY.(2)

George Nelson retired and closed George Nelson Associates in 1984. The same year he became a scholar in residence at the Cooper-Hewitt Museum.(1,2) He died in New York City in 1986.(4) In 2008, the Vitra Design Museum held a retrospective of George Nelson’s work to commemorate the 100th anniversary of his birth.(2)

References

Wikipedia.com (2 June, 2021). George Nelson (designer). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Nelson_(designer)

George Nelson Foundation, (2012). Introduction. http://www.georgenelsonfoundation.org/george-nelson/index.html

George Nelson (1908-1986), USA: Biography and more. http://www.georgenelson.org/biographymore.html

Slesin, S., (6 March, 1986). George H. Nelson, Designer of Modernist Furniture, Dies. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/03/06/obituaries/george-h-nelson-designer-of-modernist-furniture-dies.html

Martin, H., (16 November, 2016). The Story Behind George Nelson's Iconic Bubble Lamp. https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/the-story-behind-george-nelsons-iconic-bubble-lamp

Wikipedia.com (April 9, 2021). Action Office. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Action_Office

0 notes

Text

1970's-era mixed housing with some apartments rent-controlled for low income earners. Newtown.

#vintage#1970's#apartment block#affordable housing#social housing#1960's 1970's era architecture#streetscape#rent control#low rent#facade#skyline#inner west sydney

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

FOMA 9: Radical Open Architecture

Our ninth edition of Forgotten Masterpieces focuses on two Dutch architects from the period between 1950’s until the 1970’s, Herman Haan and Frank van Klingeren, which are relatively unknown outside the Netherlands. Although they differ in their architecture, what connects them is their position towards an open society, which was – sometimes quite literally – realized in their work. Besides that, they were both media (television mainly) personalities in an era when this was not common among architects.

Materiality of the Haan’s House. | Photo by Violette Cornelius

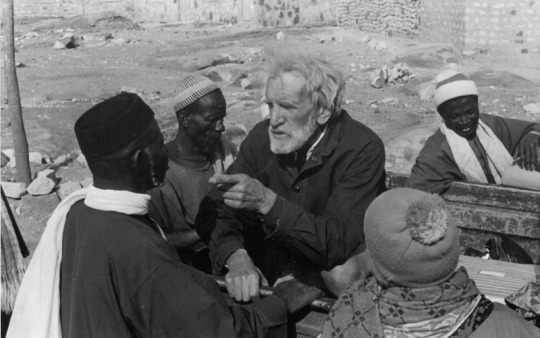

Herman Haan (1914-1996), a typical architect’s architect, was admired among colleagues, but hardly known by the general public. In his case it must be noted that he was very well-known in the 1960’s outside the profession because of the media attention (television, newspapers, books) he received for his travels and explorations in and around the Sahara and Mali. In Mali he documented the life and artefacts of the Dogon people and he was leader and initiator of an expedition that discovered the remains of the forefathers of the Dogon: the Tellem people. In fact, he had travelled to Africa on a yearly basis (mainly in and around the Sahara) since he was a young boy, and one could say that he lived two full lives; one of an adventurer/ explorer/ archaeologist and another life as an architect in the Netherlands. He was a sort of an architect Indiana Jones.

Herman Haan among the Dogon. | Source via Partners Pays-Dogon

As an architect he was one of the incidental participants of the Team 10 family and he brought Aldo van Eyck into contact with the Dogon people. He was also one of the Team 10 members that attended the famous CIAM meeting in Otterlo (NL) in 1959, that caused CIAM to break up definitely. His work consists mainly of private houses. It is very much within the post-war, modernist tradition of Team 10, but with a special open brutality and a humanist twist. He was one of the first modern architects that re-used building materials in his designs.

Herman Haan’s house in Rotterdam, 1951-53. | Photo by Violette Cornelius

Haan build the radically open house for himself and his wife Hansje on a piece of land at the edge of Rotterdam, where the debris of the demolished city centre during a bombardment in 1940 was collected. It consists of two elongated volumes: an elevated, floating open volume with the living room above and a small architect’s studio underneath half of this volume, and a second, closed volume with garage and two small bedrooms. In-between is a double height open space that connects both volumes as an entrance lobby.

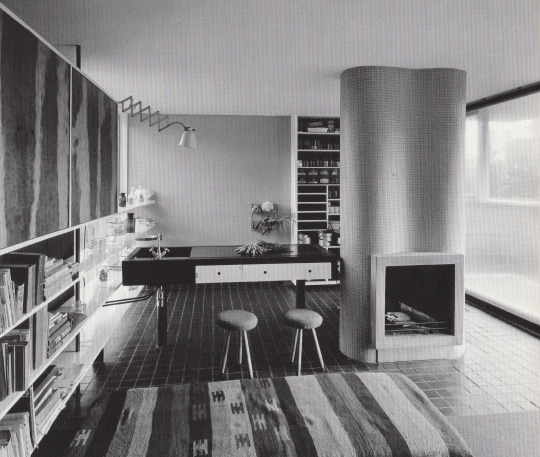

The main feature of the living room volume is the set of four glass sliding doors, that can all be opened at the same time, thus literally opening the living room to the outdoors and the view over one of the main entrance roads of the city (and Haan did not believe in the use of curtains either). Another feature is the open kitchen, if not one of the first in architecture, then certainly of one the most radical open kitchens ever. It consists of a simple, small cooking table with a floating kitchen sink that stands in the middle of the living room and is connected to the open fire chimney only. Cooking is a social activity, so Haan had learned in Africa.

Open space and open kitchen. | Photo by Violette Cornelius

The bricks of the closed bedroom volume used in the interior are re-used pavement bricks from the quays of the Rotterdam harbor. An old poplar tree that stood on the site was cut into veneer and used as a finishing layer of cupboards all around the house. Parts of the stone flooring was salvaged from the rubble heap on which the house is build. The house is still standing, but the radical openness proved to be too much for the current owners. It is today surrounded by a wall of conifers, and parts of the glass facades are closed off.

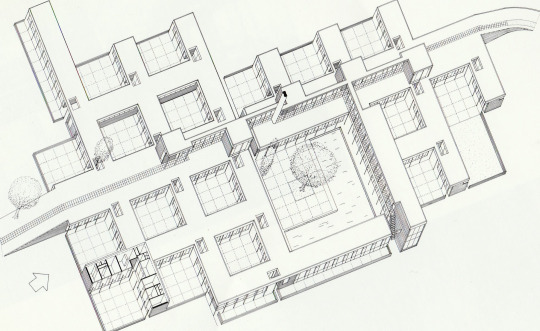

Patio Student Housing, Drienerlo Enschede, 1964-65. | Source Rijksdient voor het Cultureel Erfgoed

Herman Haan was asked by his mentor Willem Van Tijen (a first generation functionalist modernist) to build a batch of student housing for the campus of a new technical university in Enschede. It is unquestionably his most African project. The concept was based on the Matmata cave dwellings of southern Tunesia, famous for being the home of Luke Skywalker in Star Wars IV. It is also his most structuralist design, a so called mat-building based on a continuous square configuration, that was also one of the Team 10 tropes. The design consists of seventeen square units, joined in a larger configuration. Each unit consists of a patio with student rooms on two sides. Eight students live in such a patio unit (six one-person rooms, one two-person). Access to the rooms is from the patio, so each student room has his own front-door. Access to these patio’s themselves is mainly from the roof of the one - storey complex. A foot-path and bicycle road crosses the roof of the complex. The roof itself was one of the first green roofs in the Netherlands, sowed in with grasses. In the middle of the complex a larger central square and pool serves as a meeting place for the student community. The same pavement bricks from the quays of Rotterdam harbor, that he used in his own house and other projects, were used extensively in this one too. The project was recently fully restored and established as a National Monument of post-war architecture.

Frank van Klingeren selling his open architecture. | Source via Nieuwlanderfgoed

Frank van Klingeren (1919-1999), a Provo in a business suit was, unlike Herman Haan, a real outsider in the Dutch architecture scene of the 1960’s and 1970’s. Trained as a construction engineer, he was a self-taught architect that kept away from architecture gatherings or cliques. He was more at home among people from avant-garde theatre of the period, than among ‘Forum’ architects like Van Eyck, Bakema and Hertzberger, although he shared a lot of his ideas with the latter. They even received the Fritz-Schumacher-Preis in 1974 together, Hertzberger for his Centraal Beheer office in Apeldoorn, and Van Klingeren for ‘t Karregat in Eindhoven. Both buildings celebrating multi-functionality and an openness towards change.

Although Van Klingeren was quite productive as an architect from the late ‘50’s to the mid ‘70’s, his main claim to fame was established with the design of three consecutive multi-cultural community buildings or Agora as he called them; De Meerpaal in Dronten, Agora in Lelystad and ‘t Karregat in Eindhoven. But his media presence was broader than that. Especially after finishing De Meerpaal, he evolved towards a counterculture societal critic and television personality, while keeping his distance from direct involvement in flower power, hippie or provo movements. He was in that sense a Provo(cateur) in a business suit.

De Meerpaal, Dronten, 1965-1967 | Photo by Jan Versnel

Asked for a simple multipurpose community building with provisions for amateur theatre and music, sports and a small café for new inhabitants of the pioneer-village Dronten that was being built in the new polder Flevoland, Van Klingeren did much more than that, and in a sense also much less. He gave more space, more functionalities and more possibilities, but less stuff (walls, floors) and in a way less architecture. Van Klingeren was inspired by the village squares or agora of the Mediterranean that functioned as meeting places, open-air theaters and playground, while showing a generic, in fact absent, architecture. In this sense his agora can be seen as a sort of architectural urbanism.

De Meerpaal is in fact nothing more than a covered village square, protected from the northern climate by glass walls. It is a large glass-and-steel box measuring 50x70 meters with a couple of smaller brick boxes (some art and exhibition rooms, a tilted box with restaurant/ café, and a small staff office) added along the edges. In the middle of the covered space an oval open-air theatre - soon dubbed ‘The Egg’ - is the main architectural gesture. There are hardly any walls inside, neither are there many spaces for any specific function. All functions mix, sometimes causing hindrance. According to Van Klingeren, hindrance leads to conversation and mutual understanding. De Meerpaal was used for many different functions; the weekly market, agricultural exhibitions, sports, parties, large scale meetings etcetera. The oval theatre with its central stage (the setting of audience and use could be changed easily, anything was possible except a traditional proscenium set-up), became a place where alternative theatre groups loved to perform.

De Meerpaal was also the main stage for large size, live national television productions and games, until large-scale studios were built in Hilversum. Besides this television attention for Dronten, it was also equipped with a (rotating) film screen on which, besides normal movies, live television could be screened of the so-called Eidophor technique. Thus, the whole village could watch the news or football matches together from the indoor terrace of the café. De Meerpaal has, with some merit, been compared to Cedric Prices (unbuild) Fun Factory of the same time. But while Fun Factory can be called a machine for multi functionality, full of specific intentionality, De Meerpaal is more like a generic square where the intentionality of use and meeting is not outspoken, but nevertheless - maybe more so than in Fun Factory - more open to chance and unpredictable uses.

Agora Lelystad, 1966-1972 | Photo by Jan Versnel

While construction work for De Meerpaal was still going on, Van Klingeren was commissioned to design a similar multifunctional building for Lelystad, the second new town to be built in Flevoland. It was planned to become the largest city and capital of the new polder province. The first design elaborated further on the open concept and mix of functions of De Meerpaal. In this case the scale was larger and Van Klingeren managed to lure in the churches (three different denominations) into the collective. Although each church would have its own space, it was to be open like the open-air theatre and - as Van Klingeren argued - since these spaces would only be used on Sundays, they could double as extra theatre and meeting spaces for the rest of the week.

Meanwhile it was decided that not Lelystad but a newer town Almere to be built closer to Amsterdam would be more important and bigger, and construction of Lelystad was delayed. This meant that the scale and budget of Van Klingeren’s Lelystad Agora diminished too. Instead Van Klingeren proposed the opposite; to enlarge the program with shops and housing facilities (hotel, boarding house), but to do this within the limited budget (to do more with less, was one of his favorite slogans). He proposed a U-shaped steel post-and-beam structure of three storeys, to be left open and to be colonized over time by the people and by entrepreneurs. The ground floor would still be like De Meerpaal, only a swimming pool was added. This open ground floor would be connected to the adjoining park so that Van Klingeren started to title the different zones in the lay-out as if they were landscapes: theatre landscape, youth-cave, swimming and undressing landscape. All in an open ‘wall-less’ setting. While De Meerpaal could be called urbanism (realised with architectural means), this last design for Lelystad would have been a landscape design instead, growing over time. The proposal proved to be too radical for Lelystad and a toned down. Conventional Agora was built in the city centre by one of Van Klingeren former employees.

‘t Karregat Eindhoven, 1970-1973 | Photo by Jan Versnel

Van Klingerens attention had already shifted towards Eindhoven. There he was given the opportunity to build another multifunctional community building for a new experimental housing project. This time it would include – besides the cultural and sports facilities – a small shopping mall (bakery, greengrocer, a small supermarket) and a health facility with general practice (the café serving as a waiting room) and a pharmacy. But the real experiment was the inclusion of two elementary schools and a nursery school. These too would be built without any internal walls to speak of, one organic whole with the rest of the spaces and facilities, a field of communal activity. Children, according to Van Klingeren, would learn their arithmetic next to the supermarket cash desk, mothers could meet each other at the café bar after bringing their kids to school.

The one storey building (or rather the enclosed and climate controlled landscape) is situated underneath a flat roof with an open steel structure, that is supported by steel umbrellas; pyramid shaped skylights on open steel columns. All services (air-conditioning, electricity, rainwater drainage and ventilation) are positioned in sight within the steel roof structure, and can be accessed (and changed when the floor configuration is changed) from below. The perimeter facade is built-up out of off-the-rack components (mainly from the glass-house industry). In general, there is a certain high-tech feel to the architecture, albeit with the informal sloppiness of a self-built community house. Named ‘t Karregat (cart-sink after the shopping carts that would gather there) it was opened in 1973 without hardly any change in the original concept. After a couple of years, the schools without walls proved to be too much for the teachers, that went into the experiment without any primary experience whatsoever in new schooling methods. Glass partitions were applied, but besides that the openness was maintained and ‘t Karregat became an overnight success, also because the community ran the cultural facilities for themselves.

Afterlife

Both De Meerpaal and ‘t Karregat were highly successful until the 1990’s. When De Meerpaal, formerly publicly owned, was privatized in the 1980’s the open space was divided into smaller areas, and finally plans were made to demolish it around the year 2000. Protests from the architecture community and the State Architect managed to save the structure, especially the roof and The Egg. But several theatre spaces and a public library (all very much enclosed) were added so that the new Meerpaal can hardly be called open anymore, at least not in the sense that it was open in the 1960’s, both architecturally and functionally. More or less the same fate came over ‘t Karregat. After a successful period of a couple of decades, plans for demolishment were halted, and it is now restored; but a smooth false ceiling has killed the informal sloppiness of the original, partition walls have been added, patios are cut into the roof. Operation succeeded, patient died.

One may wonder whether this open architecture of De Meerpaal and ‘t Karregat was not so much geared towards it’s own time, and so much part of the open society, that it failed to be open towards societal change in the 1990’s. It very well may be the case, but then so is the architecture of the renewal. One of the protesting architects against demolishing De Meerpaal, Kas Oosterhuis, proposed to wrap the building up in plastic and to wait until society and technology would have been advanced towards a new phase fitting the original intentions of De Meerpaal. This would actually have been a great solution, and one has the feeling that now, only fifteen years after, the new Meerpaal feels old, and the old Meerpaal would fit much better in our current times, which are media driven, semi-virtual, but also with a longing for the open society of 50 years ago. The plastic could have been wrapped of already.

---

#FOMA 9: Piet Vollaard