#Paoli Massacre

Photo

The Battle of Paoli (also known as the Battle of Paoli Tavern or the Paoli Massacre) was a battle in the Philadelphia campaign of the American Revolutionary War fought on September 20, 1777.

#Paoli Massacre Monument#Battle of Paoli#Battle of Paoli Tavern#Malvern#Paoli Massacre#Philadelphia campaign#20 September 1777#US history#245th anniversary#American Revolutionary War#tourist attraction#landmark#free admission#American War of Independence#Paoli Battlefield Site and Parade Grounds#Paoli Massacre obelisk#landscape#countryside#original photography#summer 2016#flora#woods#forest#lawn#snake fence

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

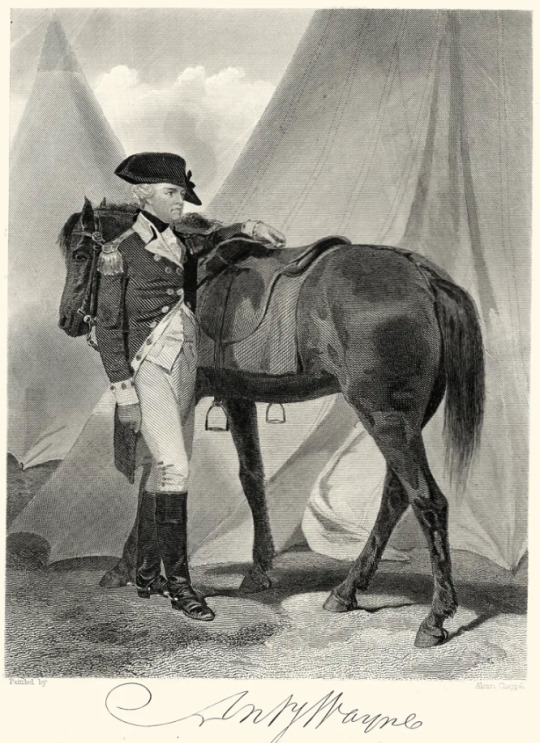

The Ghost of General ‘Mad Anthony’ Wayne and his Missing Bones

Photos provided by: UnchartedLancaster.com

“Anthony Wayne was an American soldier, officer, and statesman during the Revolutionary War. His daring military exploits and fiery personality quickly earned him a promotion to brigadier general and the nickname “Mad Anthony.”

Wayne is probably the second most frequently sighted ghost on the East Coast. Second only to Abraham Lincoln. He is also the only Pennsylvanian known to have two separate graves, with body parts in both."

"George Washington considered Wayne to be one of the best tactical commanders and military strategists of the Revolution.

Wayne was born on January 1, 1745, near Paoli in Chester county. He received an excellent education and worked as a surveyor for Benjamin Franklin. When the Revolutionary War began, he assembled a militia and became colonel of the 4th Regiment in Pennsylvania. Wayne aided Benedict Arnold and saved Washington’s troops from a massacre at the Battle of Brandywine in September 1777.

Wayne was at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-1778, where the Continental Army recouped and rested. Wayne led men to more victories when fighting resumed, including a decisive battle at Stony Point along the Hudson River.

After the war, Wayne settled in Georgia on land granted to him for his military service. He briefly represented Georgia in the House of Representatives before returning to the Army to accept command of U.S. forces in the Northwest Indian War. His forces defeated the Western Confederacy, an alliance of several Native American tribes, at the 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers, and he masterminded the Treaty of Greenville, which ended the war.

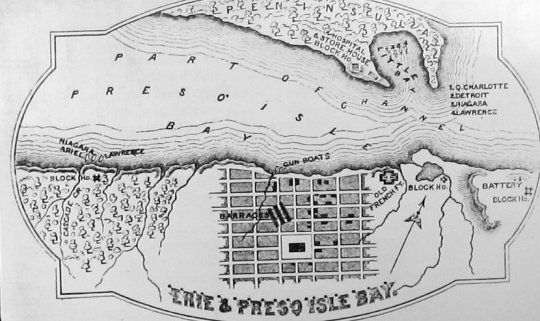

Photo provided by: HistoryLink

Two years later, Wayne died on December 15, 1796, in Erie, Pennsylvania, at Fort Presque Isle while on active duty. He was 51.

Following his wishes, Wayne, wearing his uniform, was buried two days after his death in a plain wooden coffin at the foot of the flagstaff of the post’s blockhouse. The top of the coffin bore his initials, age, and the year of his death in brass tacks.

Had it not been for a strange twist of fate, “Mad Anthony” Wayne would have laid there in peace for eternity.

For 12 years, the remains of Wayne remained undisturbed in a plain grave. However, some thought his burial was not fitting for such a great war hero, and in 1809 Wayne’s family decided to bring him home to rest in St. David’s Church Cemetery closer to his home in Radnor Township, not far from Valley Forge.

When Wayne’s son Colonel Isaac Wayne had the coffin opened in Erie, everyone was shocked! Instead of a crumbling pile of bones, they found a body in an excellent state of preservation.

Isaac had come ill-prepared to move an entire body across the state.

A local physician, Dr. James Wallace, came up with a remedy. He suggested they put Wayne’s body in a large vat and boil it to separate the flesh from the bone.

The general’s flesh and clothing were reinterred beneath the blockhouse. Meanwhile, Isaac took his father’s bones in the back of a wagon and made the long 400-mile journey across the state along what is now U.S. Route 322.

This may be hard to believe, but Pennsylvanian roads were even worse in the early 1800s. They were bumpy paths full of rocks, ruts, and tree stumps.

When Isaac finally arrived at the gravesite and attempted to reassemble the skeleton, the family discovered to their horror that several of the bones were missing. It appeared that some of the bones had fallen out of the wagon while making the arduous trip across the commonwealth.

Isaac was greatly distressed by this turn of events and regretted his decision to disinter his father for the rest of his life.

After that, stories began to surface that every New Year’s morning, General “Mad Anthony” Wayne’s birthday, his ghost rises and begins the long journey on horseback from St. David’s to Erie and back in search of his missing bones. People along that route have insisted that a man clad in Colonial garb has been seen riding a horse and stopping if searching for something.

“Mad Anthony’s” ghost has been seen throughout Pennsylvania, including along Route 1 near Chadd’s Ford, where the Battle of Brandywine occurred and at Valley Forge National Park. There have also been sightings in New Jersey, New York, Virginia, and Canada.

Sometimes Wayne is astride his trusty steed Nab, described as possessing fire-flashing hoofs.

Whether alone or on horseback, Wayne’s ghost looks fierce and determined, as though he is still waging battles against the British and Germans.”

Story provided by: UnchartedLancaster.com

1 note

·

View note

Photo

British light infantry of the 40th Foot assaulting American rebels during the battle of Paoli, September 20 1777. The engagement earned them the nickname “the Bloodhounds,” while the Pennsylvanian brigades they had savaged swore revenge. The light infantry subsequently wore red feathers in their hats, partly as a mark of pride in their victory, partly ‘to prevent anyone not engaged in the action from suffering on their account.’

Detail from A Dreadful Scene of Havoc by Xavier della Gatta, 1782.

#history#military history#revwar#american war of independence#18th century#british army#paoli#paoli's tavern#paoli massacre#battle of paoli#light infantry#british light infantry#american revolution

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quick Thought – Tuesday, September 21, 2021: Don't Leave Room for Sin

Quick Thought – Tuesday, September 21, 2021: Don’t Leave Room for Sin

Read

Philippians 4:10-20

Not that I am speaking of being in need, for I have learned in whatever situation I am to be content.

Philippians 4:11

Reflect

America has had its share of sad stories, but few are as sadly tragic as the rise and fall of our country’s first traitor — Benedict Arnold. Born into privilege, Arnold initially grew up with education and opportunities, but his father’s…

View On WordPress

#American#battle#bayonet#Bible#bible study#blessing#British#children#devotion#generation#heritage#history#Israel#massacre#paoli#prosperity#Quick Thought#revolution#sword#teach#worship

0 notes

Text

Napoléon and La Fayette in 1791

I have gone through all of the 15 volumes of Napoléon Bonaparte - Correspondance générale, published by the Fondation Napoléon in search of any letter related to La Fayette - I think I found Napoléon’s first every reference to La Fayette. In a letter to Matteo Buttafoco, dated January 25, 1791 he wrote:

Un roi qui ne désire jamais que le bonheur de ses compatriotes, éclairé par M. La Fayette, ce constant ami de la liberté, put dissiper les intrigues d’un ministre perfide que la vengeance inspira toujours à vous nuire.

My translation:

A king who desires nothing but the happiness of his compatriots, enlightened by M. La Fayette, the constant friend of liberty, was able to dispel the intrigues of a perfidious minister whom revenge always inspired to harm one.

And, still in the same letter but a bit further down:

Ô Lameth! Ô Robespierre! Ô Pétion! Ô Volney! Ô Mirabeau! Ô Barnave! Ô Bailly! Ô La Fayette! voilà l’homme qui ose s’asseoir à côté de vous! Tout dégouttant du sang de ses frères, souillé par des crimes de toute espèce, il se présente avec confiance sous une veste de général, inique récompense de ses forfaits! Il ose se dire représentant de la nation, lui qui la vendit, et vous le souffrez! Il ose lever les yeux, prêter les oreilles à vos discours et vos le souffrez!

My translation:

O Lameth! O Robespierre! O Pétion! O Volney! O Mirabeau! O Barnave! O Bailly! O La Fayette! here is the man [Pascal/Pasquale Paoli] who dares to sit next to you all! All dripping with the blood of his brothers, soiled by crimes of all kinds, he presents himself confidently under a general's jacket, iniquitous reward for his crimes! He dares to call himself a representative of the nation, he who sold it, and you suffer it! He dares to raise his eyes, lend his ears to your speeches and your suffer it!

A little bit of background to this letter. It was written in early 1791 - La Fayette’s popularity had lessened a bit after its peak at the Fête de la Fédération but we also have not yet reached the bottom-mark after the Champ de Mars massacres. Napoléon called La Fayette a “constant friend of liberty” and generally expressed a great deal of respect and admiration for the Marquis. Ironically, it was exactly this love for liberty that would set La Fayette and Napoléon at odds with each other later on. It would not be too long until this friendly tone would cease.

Pasquale Paoli was a Corsican politician and military leader. He was later forced to go into exile in England where he became seriously pro-British and even received a pension from George III. When an amnesty was passed during the French Revolution, he returned to Corsica and participated again in the islands politics. He was greatly admired because nobody really knew about his pro-British sentiments. He participated in the French Revolution and sided with the Royalists. Still, he was greatly admired. When Napoléon attempted to write the history of Corsica, he reached out to Paoli to get his help and opinion. The differences between the two men became quickly obvious. Paoli would later part from the Revolution after the trial of the King, would manipulate the war between Britain and France in favour of the British and finally go into a second exile in England. The recipient of the letter, Matteo Buttafoco, was one of Paoli’s greatest political opponents.

#lafayette#la fayette#marquis de lafayette#general lafayette#historical lafayette#napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#1791#french revolution#french history#england#france#british history#history#pasquale paoli#matteo buttafoco#corsica#george iii#letters

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

John, if you don't mind me asking, what was the scariest battle you fought in? ( in your opinion that is:3)

I've only been in three, if you count the raid we did to get revenge for the Paoli Massacre. Of those, Germantown was the one I came closest to death with, and that scared me, but the raid I was in was the bloodiest and most needlessly violent, and I'm sure I'll have nightmares of it.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

American Revolutionary War battles

Recently they did work on history, wrote an essay on the theme of revolutionary wars in America. A lot of blood has been shed on our land, war is evil. It begins in offices and ends there, but hundreds of thousands of young people die. Here is a list of battles, sorted by chronology.

Battle Date Colony/State Outcome

Powder Alarm

* September 1, 1774 Massachusetts British soldiers remove military supplies

Storming of Fort William and Mary

* December 14, 1774 New Hampshire Patriots seize powder and shot after brief skirmish.

Battles of Lexington and Concord

April 19, 1775 Massachusetts Patriot victory: British forces raiding Concord driven back into Boston with heavy losses.

Siege of Boston

April 19, 1775 –

March 17, 1776 Massachusetts Patriot victory: British eventually evacuate Boston after Patriots fortify Dorchester heights

Gunpowder Incident

* April 20, 1775 Virginia Virginia governor Lord Dunmore removes powder to a Royal Navy ship, standoff is resolved peacefully

Capture of Fort Ticonderoga

May 10, 1775 New York Patriot victory: Patriots capture British posts at Ticonderoga and Crown point

Battle of Chelsea Creek

May 27–28, 1775 Massachusetts Patriots victory: Patriots capture British ship Diana

Battle of Machias

June 11–12, 1775 Massachusetts Patriot forces capture the HM schooner Margaretta

Battle of Bunker Hill

June 17, 1775 Massachusetts British victory: British drive Patriot army from the Charlestown peninsula near Boston but suffer heavy losses

Battle of Gloucester

August 8, 1775 Massachusetts Patriot victory

Siege of Fort St. Jean

September 17 –

November 3, 1775 Quebec Patriot victory: Patriots capture British force and subsequently overrun Montreal and much of Quebec

Burning of Falmouth

October 18, 1775 Massachusetts British burn Falmouth

Battle of Kemp's Landing

November 14, 1775 Virginia British victory

Siege of Savage's Old Fields

November 19–21, 1775 South Carolina Patriot victory: Patriots defeat loyalist force

Battle of Great Bridge

December 9, 1775 Virginia Patriot victory: Lord Dunmore's loyalist force is defeated

Snow Campaign

December 1775 South Carolina Patriot campaign against loyalists in South Carolina

Battle of Quebec

December 31, 1775 Quebec British victory: British repulse Patriot assault on Quebec city

Burning of Norfolk

January 1, 1776 Virginia British bombard Norfolk and Patriots destroy what they see as a loyalist stronghold

Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge

February 27, 1776 North Carolina Patriot victory: loyalist force of Regulators and Highlanders defeated

Battle of the Rice Boats

March 2–3, 1776 Georgia British victory

Battle of Nassau

March 3–4, 1776 Bahamas Patriots raid against the Bahamas to obtain supplies

Battle of Saint-Pierre

March 25, 1776 Quebec Patriot victory

Battle of Block Island

April 6, 1776 Rhode Island British victory

Battle of The Cedars

May 18–27, 1776 Quebec British victory

Battle of Trois-Rivières

June 8, 1776 Quebec British victory: Patriots forced to evacuate Quebec

Battle of Sullivan's Island

June 28, 1776 South Carolina Patriot victory: British attack on Charleston is repulsed

Battle of Turtle Gut Inlet

June 29, 1776 New Jersey Patriot victory

Battle of Lindley's Fort

July 15, 1776 South Carolina Patriot victory: Native Americans attack repulsed

Battle of Long Island

August 27, 1776 New York British victory: in the largest battle of the war the Patriot army is outflanked and routed on Long Island but later manages to evacuate to Manhattan

Landing at Kip's Bay

September 15, 1776 New York British victory: British capture New York City

Battle of Harlem Heights

September 16, 1776 New York Patriot victory: Patriots repulse British attack on Manhattan

Battle of Valcour Island

October 11, 1776 New York British victory: British defeat Patriot naval force on Lake Champlain, but victory comes too late to press the offensive against the Hudson valley

Battle of White Plains

October 28, 1776 New York British victory

Battle of Fort Cumberland

November 10–29, 1776 Nova Scotia British victory

Battle of Fort Washington

November 16, 1776 New York British victory: British capture 3,000 Patriots on Manhattan in one of the most devastating Patriot defeats of the war

Battle of Fort Lee

November 20, 1776 New Jersey British victory: Patriots begin general retreat

Ambush of Geary

December 14, 1776 New Jersey Patriot victory

Battle of Iron Works Hill

December 22–23, 1776 New Jersey British victory

Battle of Trenton

December 26, 1776 New Jersey Patriot victory: Patriots capture Hessian detachment at Trenton

Second Battle of Trenton

January 2, 1777 New Jersey Patriot victory

Battle of Princeton

January 3, 1777 New Jersey Patriot victory: Patriots defeat a small British force, the British decide to evacuate New Jersey

Battle of Millstone

January 20, 1777 New Jersey Patriot victory

Forage War

January–March 1777 New Jersey Patriots harass remaining British forces in New Jersey

Battle of Punk Hill

March 8, 1777 New Jersey Patriot victory

Battle of Bound Brook

April 13, 1777 New Jersey British victory

Battle of Ridgefield

April 27, 1777 Connecticut British victory

Battle of Thomas Creek

May 17, 1777 East Florida British victory

Meigs Raid

May 24, 1777 New York Patriot victory

Battle of Short Hills

June 26, 1777 New Jersey British victory

Siege of Fort Ticonderoga

July 5–6, 1777 New York British victory

Battle of Hubbardton

July 7, 1777 Vermont British victory

Battle of Fort Ann

July 8, 1777 New York British victory

Siege of Fort Stanwix

August 2–23, 1777 New York Patriot victory: British fail to take Fort Stanwix

Battle of Oriskany

August 6, 1777 New York British victory

Second Battle of Machias

August 13–14, 1777 Massachusetts British victory

Battle of Bennington

August 16, 1777 New York Patriot victory

Battle of Staten Island

August 22, 1777 New York British victory

Battle of Setauket

August 22, 1777 New York British victory

First Siege of Fort Henry

September 1 or 21, 1777 Virginia Patriot victory

Battle of Cooch's Bridge

September 3, 1777 Delaware British victory

Battle of Brandywine

September 11, 1777 Pennsylvania British victory

Battle of the Clouds

September 16, 1777 Pennsylvania Battle called off due to rain

Battle of Freeman's Farm

September 19, 1777 New York British tactical victory: First of the two

Battles of Saratoga

Battle of Paoli

September 21, 1777 Pennsylvania British victory

Siege of Fort Mifflin

September 26 –

November 15, 1777 Pennsylvania British victory

Battle of Germantown

October 4, 1777 Pennsylvania British victory

Battle of Forts Clinton and Montgomery

October 6, 1777 New York British victory

Battle of Bemis Heights

October 7, 1777 New York Patriot victory: Second of the two

Battles of Saratoga

, British under Burgoyne driven back and forced to surrender 10 days later

Battle of Red Bank

October 22, 1777 New Jersey Patriot victory

Battle of Gloucester

November 25, 1777 New Jersey Patriot victory

Battle of White Marsh

December 5–8, 1777 Pennsylvania Patriot victory

Battle of Matson's Ford

December 11, 1777 Pennsylvania British victory

Battle of Barbados

March 7, 1778 Barbados British victory

Battle of Quinton's Bridge

March 18, 1778 New Jersey British victory

North Channel Naval Duel

April 24, 1778 Great Britain Patriot victory

Battle of Crooked Billet

May 1, 1778 Pennsylvania British victory

Battle of Barren Hill

May 20, 1778 Pennsylvania Indecisive

Mount Hope Bay raids

May 25–30, 1778 Rhode Island British victory

Battle of Cobleskill

May 30, 1778 New York British-Iroquois victory

Battle of Monmouth

June 28, 1778 New Jersey Draw: British break off engagement and continue retreat to New York

Battle of Alligator Bridge

June 30, 1778 East Florida British victory

Wyoming Massacre

July 3, 1778 Pennsylvania British-Iroquois victory

First Battle of Ushant

July 27, 1778 Bay of Biscay Indecisive

Siege of Pondicherry

August 21–October 19, 1778 India British victory

Battle of Newport

August 29, 1778 Rhode Island British victory

Grey's raid

September 5–17, 1778 Massachusetts British victory

Invasion of Dominica

September 7, 1778 Dominica French victory

Siege of Boonesborough

September 7, 1778 Virginia Patriot victory

Attack on German Flatts

September 17, 1778 New York British-Iroquois victory

Baylor Massacre

September 27, 1778 New Jersey British victory

Raid on Unadilla and Onaquaga

October 2–16, 1778 Indian Reserve Patriot victory

Battle of Chestnut Neck

October 6, 1778 New Jersey British victory

Little Egg Harbor massacre

October 16, 1778 New Jersey British victory

Carleton's Raid

October 24-November 14, 1778 Vermont British victory

Cherry Valley Massacre

November 11, 1778 New York British-Iroquois victory

Battle of St. Lucia

December 15, 1778 St. Lucia British victory

Capture of St. Lucia

December 18–28, 1778 St. Lucia British victory

Capture of Savannah

December 29, 1778 Georgia British victory

Battle of Beaufort

February 3, 1779 South Carolina Patriot victory

Battle of Kettle Creek

February 14, 1779 Georgia Patriot victory

Siege of Fort Vincennes

February 23–25, 1779 Indiana Patriot victory

Battle of Brier Creek

March 3, 1779 Georgia British victory

Battle of Chillicothe

May 1779 Quebec Patriot victory

Chesapeake raid

May 10–24, 1779 Virginia British victory

Capture of Saint Vincent

June 16–18, 1779 St. Vincent French victory

Battle of Stono Ferry

June 20, 1779 South Carolina British victory

Great Siege of Gibraltar

June 24, 1779 – February 7, 1783 Gibraltar British victory

Capture of Grenada

July 2, 1779 Grenada French victory

Tryon's raid

July 5–14, 1779 Connecticut British victory

Battle of Grenada

July 6, 1779 Grenada French victory

Battle of Stony Point

July 16, 1779 New York Patriot victory

Battle of Minisink

July 22, 1779 New York British-Iroquois victory

Penobscot Expedition

July 24-August 29, 1779 Massachusetts British victory

Battle of Paulus Hook

August 19, 1779 New Jersey Patriot victory

Battle of Newtown

August 29, 1779 Indian Reserve Patriot victory

Capture of Fort Bute

September 7, 1779 West Florida Patriot-Spanish victory

Battle of Lake Pontchartrain

September 10, 1779 West Florida Patriot victory

Boyd and Parker ambush

September 13, 1779 Indian Reserve British-Iroquois victory

Action of 14 September 1779

September 14, 1779 Azores British victory

Siege of Savannah

September 16-October 18, 1779 Georgia British victory

Battle of Baton Rouge

September 20–21, 1779 West Florida Patriot-Spanish victory

Battle of Flamborough Head

September 23, 1779 Great Britain Patriot victory

Battle of San Fernando de Omoa

October 16-November 29, 1779 Guatemala British victory

Action of 11 November 1779

November 11, 1779 Portugal British victory

First Battle of Martinique

December 18, 1779 Martinique British victory

Action of 8 January 1780

January 8, 1780 Spain British victory

Battle of Cape St. Vincent

January 16, 1780 Portugal British victory

Battle of Young's House

February 3, 1780 New York British victory

San Juan Expedition

March–November, 1780 Guatemala Patriot-Spanish victory

Battle of Fort Charlotte

March 2–14, 1780 West Florida Patriot-Spanish victory

Siege of Charleston

March 29-May 12, 1780 South Carolina British victory: British recapture South Carolina following the battle

Battle of Monck's Corner

April 14, 1780 South Carolina British victory

Second Battle of Martinique

April 17, 1780 Martinique Patriot victory

Battle of Lenud's Ferry

May 6, 1780 South Carolina British victory

Bird's invasion of Kentucky

May 25-August 4, 1780 Virginia British victory

Battle of St. Louis

May 25, 1780 Louisiana Patriot-Spanish victory

Battle of Waxhaws

May 29, 1780 South Carolina British victory

Battle of Connecticut Farms

June 7, 1780 New Jersey British victory

Battle of Mobley's Meeting House

June 10–12, 1780 South Carolina Patriot victory

Battle of Ramsour's Mill

June 20, 1780 North Carolina Patriot victory

Battle of Springfield

June 23, 1780 New Jersey Patriot victory

Huck's Defeat

July 12, 1780 South Carolina Patriot victory

Battle of Bull's Ferry

July 20–21, 1780 New Jersey Loyalist victory

Battle of Colson's Mill

July 21, 1780 North Carolina Patriot victory

Battle of Rocky Mount

August 1, 1780 South Carolina Loyalist victory

Battle of Hanging Rock

August 6, 1780 South Carolina Patriot victory

Battle of Pekowee

August 8, 1780 Quebec Patriot victory

Action of 9 August 1780

August 9, 1780 Atlantic Spanish victory

Battle of Camden

August 16, 1780 South Carolina British victory

Battle of Fishing Creek

August 18, 1780 South Carolina British victory

Battle of Musgrove Mill

August 18, 1780 South Carolina Patriot victory

Battle of Black Mingo

August 28, 1780 South Carolina Patriot victory

Battle of Wahab's Plantation

September 20, 1780 South Carolina Patriot victory

Battle of Charlotte

September 26, 1780 North Carolina British victory

Battle of Kings Mountain

October 7, 1780 South Carolina Patriot victory: halts first British invasion of North Carolina

Royalton Raid

October 16, 1780 Vermont British victory

Battle of Klock's Field

October 19, 1780 New York Patriot victory

La Balme's Defeat

November 5, 1780 Quebec British-Iroquois victory

Battle of Fishdam Ford

November 9, 1780 South Carolina Patriot victory

Battle of Blackstock's Farm

November 20, 1780 South Carolina Patriot victory

Battle of Fort St. George

November 23, 1780 New York Patriot victory

Battle of Jersey

January 6, 1781 Jersey British victory

Battle of Mobile

January 7, 1781 West Florida Patriot-Spanish victory

Battle of Cowpens

January 17, 1781 South Carolina Patriot victory

Battle of Cowan's Ford

February 1, 1781 North Carolina British victory

Capture of Sint Eustatius

February 3, 1781 Sint Eustatius British victory

Battle of Haw River

February 25, 1781 North Carolina Patriot victory

Battle of Wetzell's Mill

March 6, 1781 North Carolina British victory

Siege of Pensacola

March 9-May 8, 1781 West Florida Patriot-Spanish victory

Battle of Guilford Court House

March 15, 1781 North Carolina British victory

Battle of Cape Henry

March 16, 1781 Virginia British victory

Siege of Fort Watson

April 15–23, 1781 South Carolina Patriot victory

Battle of Porto Praya

April 15, 1781 Cape Verde Draw

Battle of Blandford

April 25, 1781 Virginia British victory

Battle of Hobkirk's Hill

April 25, 1781 South Carolina British victory

Battle of Fort Royal

April 29, 1781 Martinique French victory

Action of 1 May 1781

May 1, 1781 France British victory

Battle of Fort Motte

May 8–12, 1781 South Carolina Patriot victory

Siege of Augusta

May 22-June 6, 1781 Georgia Patriot victory

Siege of Ninety-Six

May 22-June 6, 1781 South Carolina British victory

Invasion of Tobago

May 24-June 2, 1781 Tobago French victory

Action of 30 May 1781

May 30, 1781 Barbary Coast British victory

Battle of Spencer's Ordinary

June 26, 1781 Virginia British victory

Francisco's Fight

July 1781 Virginia Patriot victory

Battle of Green Spring

July 6, 1781 Virginia British victory

Naval battle of Louisbourg

July 21, 1781 Nova Scotia Franco-Patriot victory

Battle of Dogger Bank

August 5, 1781 North Sea British victory

Invasion of Minorca

August 19, 1781 – February 5, 1782 Minorca Franco-Spanish victory

Lochry's Defeat

August 24, 1781 Quebec British-Iroquois victory

Battle of the Chesapeake

September 5, 1781 Virginia French victory

Battle of Groton Heights

September 6, 1781 Connecticut British victory

Battle of Eutaw Springs

September 8, 1781 South Carolina British victory

Battle of Lindley's Mill

September 13, 1781 North Carolina Patriot victory

Long Run Massacre

September 13, 1781 Virginia British-Iroquois victory

Siege of Yorktown

September 28-October 19, 1781 Virginia Franco-Patriot victory: Cornwallis surrenders his force of over 7,000

Battle of Fort Slongo

October 3, 1781 New York Patriot victory

Siege of Negapatam

October 21-November 11, 1781 India British victory

Battle of Johnstown

October 25, 1781 New York Patriot victory

Second Battle of Ushant

December 12, 1781 Bay of Biscay British victory

Battle of Videau's Bridge

January 2, 1782 South Carolina British victory

Siege of Brimstone Hill

January 11-February 13, 1782 St. Christopher Franco-Patriot victory

Capture of Trincomalee

January 11, 1782 Ceylon British victory

Capture of Demerara and Essequibo

January 22-February 5, 1782 Demerara and Essequibo Franco-Patriot victory

Battle of Saint Kitts

January 25–26, 1782 St. Christopher British victory

Battle of Sadras

February 17, 1782 India French victory

Capture of Montserrat

February 22, 1782 Montserrat French victory

Battle of Wambaw

February 24, 1782 South Carolina British victory

Gnadenhütten massacre

March 8, 1782 Ohio

Battle of Roatán

March 16, 1782 Guatemala Patriot-Spanish victory

Action of 16 March 1782

March 16, 1782 Strait of Gibraltar British victory

Battle of Little Mountain

March 22, 1782 Virginia British-Iroquois victory

Battle of Delaware Bay

April 8, 1782 New Jersey Patriot victory

Battle of the Saintes

April 9–12, 1782 Dominica British victory

Battle of Providien

April 12, 1782 Ceylon French victory

Battle of the Black River

April–August, 1782 Guatemala British victory

Battle of the Mona Passage

April 19, 1782 Mona passage British victory

Action of 20–21 April 1782

April 20–21, 1782 Bay of Biscay British victory

Capture of the Bahamas

May 6, 1782 Bahamas Patriot-Spanish victory

Crawford expedition

May 25-June 12, 1782 Quebec British-Iroquois victory

Naval battle off Halifax

May 28–29, 1782 Nova Scotia British victory

Raid on Lunenburg

July 1, 1782 Nova Scotia Patriot victory

Battle of Negapatam

July 6, 1782 Ceylon British victory

Hudson Bay Expedition

August 8, 1782 Rupert's Land Franco-Patriot victory

Siege of Bryan Station

August 15–17, 1782 Virginia Patriot victory

Battle of Blue Licks

August 19, 1782 Virginia British-Iroquois victory

Battle of the Combahee River

August 26, 1782 South Carolina British victory

Battle of Trincomalee

August 25-September 3, 1782 Ceylon French victory

Siege of Fort Henry

September 11–13, 1782 Virginia Patriot victory

Grand Assault on Gibraltar

September 13, 1782 Gibraltar British victory

Action of 18 October 1782

October 18, 1782 Hispaniola British victory

Action of 6 December 1782

December 6, 1782 Martinique British victory

Action of 22 January 1783

January 22, 1783 Virginia British victory

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This Day in History: The Paoli Massacre precedes Valley Forge

On this day in 1777, the British launch an attack that would be known as the Paoli Massacre. Some considered the action to be cold-blooded murder, not war.

These events occurred as George Washington was trying to protect Philadelphia from the British. The American army had narrowly avoided disaster at the Battle of the Clouds, but it had bounced back and was now working to slowly encircle British General William Howe’s men. Historian Thomas J. McGuire reports the comments of one American: “We shall be able to be totally round them. . . . Howe has brought himself into a fine Predicament.”

In the midst of this situation, Washington sent roughly 2,000 men under Anthony Wayne to attack the British rear guard.

Wayne decided to camp first near Paoli Tavern, then near Warren Tavern, as he waited for reinforcements. He thought that Howe had no idea where he was.

Or at least that’s what he thought at first. Possibly, he received last minute information warning him of the potential for an attack on the 21st.

Either way, the attack perhaps came earlier than anticipated. British intelligence was better than the Americans realized. Howe knew where Wayne was, and he ordered British General Charles Grey to lead an attack on Wayne’s forces on the night of September 20.

Grey had a plan. What was it? The story concludes at the link in the comments.

#tdih#otd#this day in history#on this day#history#history blog#war of independence#today i learned#george washington#sharethehistory

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

How you doin', Alex? I figure you're lost in the memorysauce whenever you start to post in bursts on your other blog. So I thought I'd check in

Awww, so sweet of you to keep an eye on my other blog and check in!

Well, a couple of things.

First there’s a family thing going on right now, which I discussed in my last post.

But here’s what’s affecting my memory right now:

The 20th-21st was the anniversary of the Paoli massacre, which, I’m not sure if you’ve read about it, but it was,,, not fun. I wasn’t personally there, but I WAS there when General Wayne (not yet Mad Anthony, that came in 79 I believe, this was 77) got back into camp. No one in Washington’s headquarters was up yet. He had left what remained of his men into the center of camp and come to find Washington. We weren’t at Valley Forge yet so this was a different headquarters. Laurens’ and I’s bedroom was on the second floor (by that I mean the third), and we heard the knocking below us. We came out onto the stairs landing and saw Wayne at Washington’s door, hair muddy, coat in shreds, soaked in blood.

Wayne’s 1,500 men had been ambushed in the night by 1,200 redcoats led by General Charles Grey. Wayne lost hundreds, and 71 were taken captive, 40 of whom were so wounded they ended up being left behind on the way. The British lost 4 with 7 (minorly) wounded. Some call it the Battle of Paoli, but I will not. This was no battle. It was a massacre. The British were there killing just to kill.

It was most likely their attempt at revenge for the surprise attack we’d launched at Trenton the previous winter. But that’s bullshit. We only took captives at Trenton. That advance was so successful shots hardly needed fired. There were no British casualties at Trenton.

So even though I wasn’t personally there, I had to deal with the aftermath. I personally wrote up the list of dead, wounded, and missing. Five times. We always kept multiple copies. One for Washington, one for Wayne, one to send to Congress, and two spares.

The court martials to deal with the massacre were awful. The Geneva Conventions, of course, wouldn’t be in place to define war crimes for a long while yet, but there were rules of war in place, and this broke them. 12 redcoats had surrounded one of our soldiers and stabbed him to death. A physician’s examination showed he had been pierced by bayonets 46 times. 46. Paoli was certainly not a battle. Not a fair one, and I hesitate to call anything unfair a “battle.” Both sides should be of equal dispositions in a battle. This was not it.

So there’s that. Also in two days is the anniversary of when we watched the British take Philadelphia. And the anniversary of Germantown is fast approaching.

Thanks for checking in, love. I appreciate it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

#MorningMonarchy: September 20, 2021

#MorningMonarchy MP3: #September20 w/#Geopolitiks + #ThisDayInHistory & #TruthMusic by #AngryNorth!

https://mediamonarchy.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/20210920_MorningMonarchy.mp3

Download MP3

Keystone kops, corrupt California and big announcements + this day in history w/the Paoli massacre and our song of the day by Angry North on your #MorningMonarchy for September 20, 2021.

Notes/Links:

Elizabeth Warren Threatens Amazon For Selling Books Containing Misinformation; Perhaps Forgetting The…

View On WordPress

#alternative news#Angry North#geopolitiks#media monarchy#Morning Monarchy#mp3#podcast#Songs Of The Day#This Day In History

0 notes

Text

The Battle of Paoli (also known as the Battle of Paoli Tavern or the Paoli Massacre) was a battle in the Philadelphia campaign of the American Revolutionary War fought on September 20, 1777,

#Battle of Paoli#Battle of Paoli Tavern#Battle of Paoli Tavern or the Paoli Massacre#Paoli Massacre#20 September 1777#American Revolutionary War#American War of Independence#Paoli Battlefield Site and Parade Grounds#Mid-Atlantic region#Chester County#Chesco#Paoli Massacre obelisk#Malvern#Philadelphia campaign#Pennsylvania#summer 2019#free admission

1 note

·

View note

Text

Redcoats kill sleeping Americans in Paoli Massacre:

Redcoats kill sleeping Americans in Paoli Massacre:

On the evening of September 20, 1777, near Paoli, Pennsylvania, General Charles Grey and nearly 5,000 British soldiers launch a surprise attack on a small regiment of Patriot troops commanded by General Anthony Wayne in what becomes known as the Paoli Massacre. Not wanting to lose the element of surprise, Grey ordered his troops to empty their muskets and to use only bayonets or swords to attack…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Paoli Massacre

The redcoated soldiers stalk through the rainy night as silent as predators.

And predators they are, bristling with sharp claws - bayonets, the principal weapon of the European infantryman.

Their quarry is a contingent of about 1,500 American troops under the command of Gen. Anthony Wayne, camped on a farm a few miles away from the Paoli Tavern.

The date is Sept. 21, 1777. It is shortly before 1 a.m.

In a few minutes the Redcoats will attack the American camp and the formal dance that is 18th-century warfare - a minuet of fifes and drums, battles fought by soldiers arrayed in stiff lines, and letters between opposing generals who sign themselves "your obedient servant" - will turn primal.

When the sun comes up, it will find about 150 Americans dead, wounded or captured. The rest of Wayne's troops are routed. The British suffer only a handful of casualties. The soldiers of the Continental Army will call this night's British rampage through their camp a massacre - the Paoli Massacre.

In the 10 days since British and American troops pummeled one another along the Brandywine Creek on Sept. 11, the two armies have feinted and jabbed across Chester County and nearly fought another major battle.

The British, who outflanked the Americans and drove the Continental Army from the field at Brandywine, paused five days before resuming their march on Philadelphia. Gen. George Washington, the American commander in chief, has been trying since then to keep his force between Gen. Sir William Howe and the city.

Philadelphia is Howe's objective. The British commander believes that if he seizes Philadelphia, loyalists in Pennsylvania will rally to the cause of King George III, and the rebellion will begin to wither away. (Sometimes, it seems as if Howe may be right. John Adams, preparing with other members of Congress to flee Philadelphia, has been referring bitterly to the city as "that Mass of Cowardice and Toryism.")

But there are other ways to take Philadelphia than by marching straight at it and into the face of Washington's determined army of defenders.

Howe moves north through Chester County on a line that will allow him either to march on the city or go after Washington's supply bases at Valley Forge and Reading. Since Washington does not want to lose either the city or his supplies, he must fight Howe again.

On Sept. 15, Washington writes to John Hancock, the president of Congress, that he is moving the Continental Army "to get between the Enemy and the Swedes Ford [Bridgeport]," where the British might cross the Schuylkill.

The following day, the two armies run into each other on the south ridge of the Great Valley, between the White Horse Tavern and Boot Road (near what is now Immaculata College), but what shapes up in the beginning as a major battle gets rained out.

Capt. Johann Ewald, a Hessian mercenary serving with Howe's army, writes in his journal that "about five o'clock in the afternoon, an extraordinary thunderstorm occurred, combined with the heaviest downpour in this world. The army halted.

"The terrible rain caused the roads to become so bottomless that not one wagon, much less a gun, could get through, and continued until toward afternoon on the 17th, which gave the enemy time to cross the Schuylkill River with bag and baggage."

With his ammunition soaked and useless, Washington moves his bedraggled army across the muddy roads of the Great Valley to Yellow Springs, then to Reading Furnace. The retreat is exhausting. "The rain fell in torrents for eighteen hours," writes Lt. James McMichael of the 13th Pennsylvania Regiment. "This march for excessive fatigue, surpassed all I have ever experienced."

But not all of Washington's forces have gone to Yellow Springs. Wayne and two brigades remain close to the British army. On Sept. 18, Washington tells Wayne of reports that "the Enemy have turn'd down that Road from the White Horse which leads to Swedesford on Schuylkill." Washington directs Wayne to harass the British rear. The commander in chief says he will follow as quickly as possible with the main body of the army. "The cutting of the Enemys Baggage would be a great matter," Washington tells Wayne, but he cautions Wayne to "take care of Ambuscades."

Wayne thinks the British, who have camped at Tredyffrin, do not know he is behind them as he encamps two miles southwest of Paoli, not far from his home, Waynesborough. "I believe [Howe] knows Nothing of my situation," he writes on Sept. 19.

Wayne is wrong.

"Intelligence having been received of the situation of General Wayne and his design for attacking our Rear, a plan was concerted for surprising him, and the execution entrusted to Major General [Charles] Grey," British Maj. John André writes in his diary.

Grey attacks with two regiments. He leads one personally, and Col. Thomas Musgrave leads the other. Grey's detachment leaves at 10 p.m., Musgrave's at 11 p.m.

Secrecy is essential.

The soldiers are ordered to unload their weapons or to take out the flints so their muskets cannot fire accidentally and alert the Americans. They won't need to fire their weapons anyway. This is going to be a bayonet attack.

In order to keep anyone from warning the Americans, the British "took every inhabitant with them as they passed along," André writes.

After marching about three miles along the Swede's Ford Road, the British arrive at the Admiral Warren Tavern, only a mile from Wayne's camp. With information "forced" from a local blacksmith, the British fall on the American pickets.

The British charge into the camp, where they find the Americans backlit by their own campfires, making them easy targets. Any American who stands and fights is instantly cut down by swords and bayonets. André describes the scene: "... the Light Infantry being ordered to form to the front, rushed along the line putting to the bayonet all they came up with, and, overtaking the main herd of the fugitives, stabbed great numbers and pressed on their rear until it was thought prudent to order them to desist."

Howe is anxious to move his entire army across the Schuylkill, so once the bloody night's work is done, Grey's troops rejoin the main British army.

A subordinate later accuses Wayne of failing to act on information that could have prevented the attack. Wayne demands a court-martial to clear his name and is exonerated.

American soldiers consider the clash at Paoli a display of savagery, dubbing the British light infantry "Bloodhounds." A "Scene of Butchery," one American officer calls it. William Hutchinson, a teenage Chester County militiaman whose unit was not at Paoli, recalls years later encountering a survivor two days after the attack who had been tortured by British soldiers. The Redcoats "formed a cordon around him and... every one of them in sport had indulged their brutal ferocity by stabbing him in different parts of his body and limbs... ."

When they meet the British again, the Americans will remember Paoli.

SOURCE

#battle of paoli#paoli's tavern#paoli massacre#history#military history#american revolution#revwar#american war of independence#british army

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quick Thought – Monday, September 20, 2021: Forgotten History

Quick Thought – Monday, September 20, 2021: Forgotten History

Read

Deuteronomy 32:1-9

Remember the days of old;

consider the years of many generations;

ask your father, and he will show you,

your elders, and they will tell you.

Deuteronomy 32:7

Reflect

As a child I lived in Pennsylvania for a couple of years. We used to take field trips to historic sites such as Valley Forge and the Liberty Bell, and I remember thinking that those trips literally…

View On WordPress

#American#battle#bayonet#Bible#bible study#blessing#British#children#devotion#generation#heritage#history#Israel#massacre#paoli#prosperity#Quick Thought#revolution#sword#teach#worship

0 notes

Note

Hey, I want to start reading SOA but I have no idea where to start. I noticed that you have both chapters and ficlets and I was wondering if there was a concrete order it's all meant to be read in (in regards to the ficlets)

If you want to read everything in chronological order, most of the ficlets on the compilation post have some instructions for when they happen.

The first chapter is John’s prologue, then through “Prelude” and “Gentleman” by @adhd-ahamilton, all the ficlets follow Alex’s timeline before ch 2.

Then read straight through ch 2 and 3

“Polish and Pursue” comes sometime before the party in 4.

You can read “Almost Something” after 5 or once you get to the part where they hear about the Paoli Massacre. It happens in parallel to the scene in the tent.

Follow the instructions for “Comfort”, in 7 when Alex leaves the tent.

“Ficlet 1″ goes before John joins the other aides in the parlor in 9.

“Special Succors” explains what Alex is doing between 9 and 10, then the whole Albany series happens while John’s experiencing 10 and 11 so you should read those chapters then the ficlets before you get to 12.

“Ficlet 2″ happens while Alex and Lafayette are in Washington’s office in 12 after John and Alex argue about keeping secrets from him.

You’ll understand what all this means as you go, but hopefully that helps.

It’s not actually imperative that you read everything in order either. A lot of people have said it’s been helpful for them to reread things and I like to think the ficlets kinda unlock parts of the story as we go, showing what Alex was doing in parallel.

31 notes

·

View notes

Quote

On the evening of September 20, 1777, near Paoli, Pennsylvania, General Charles Grey and nearly 5,000 British soldiers launch a surprise attack on a small regiment of Patriot troops commanded by General Anthony Wayne in what becomes known as the Paoli Massacre. Not wanting to lose the element of surprise, Grey ordered his troops to empty their muskets and to use only bayonets or swords to attack the sleeping Americans under the cover of darkness.

With the help of a Loyalist spy who provided a secret password and led them to the camp, General Grey and the British launched the successful attack on the unsuspecting men of the Pennsylvania regiment, stabbing them to death as they slept. It was also alleged that the British soldiers took no prisoners during the attack, stabbing or setting fire to those who tried to surrender. Before it was over, nearly 200 Americans were killed or wounded. The Paoli Massacre became a rallying cry for the Americans against British atrocities for the rest of the Revolutionary War.

Less than two years later, Wayne became known as "Mad Anthony" for his bravery leading an impressive Patriot assault on British cliff-side fortifications at Stony Point on the Hudson River, 12 miles from West Point. Like Grey's attack at Paoli, Wayne's men only used bayonets in the 30-minute night attack, which resulted in 94 dead and 472 captured British soldiers.

History.com

3 notes

·

View notes