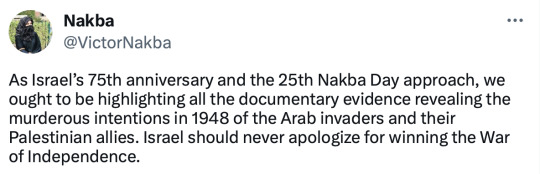

#war of independence

Text

WHY ARE THERE LIKE NO SHOWS OR MOVIES ON THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION LIKE ALL WE GET IS TURN, 1776, HAMILTON AND LIBERTY'S KIDS???

#amrev#American revolution#revolutionary war#liberty's kids#hamilton#1776 musical#turn washington's spies#american revolutionary war#war of independence

324 notes

·

View notes

Text

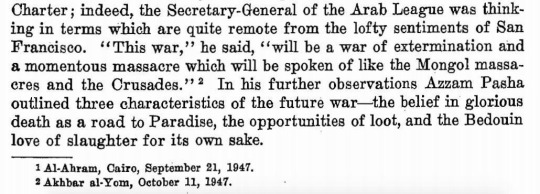

Letter from John Adams to the President of Congress

Record Group 360: Records of the Continental and Confederation Congresses and the Constitutional ConventionSeries: Papers of the Continental CongressFile Unit: Letters from John Adams

Passy Decr 6. 1778 [29 in upper right corner] Sir I have had the Honour to inclose to Congress, the speech at the opening of the British Parliament, by several opportunities: But as it opens the Intentions of the Ennemy, and warns us to be prepared, for all the Evils, which are in their Power to inflict and not in our Power to prevent, I inclose it again in another form. I have the Honour to be, with the highest Respect Sir your most obedient, and most humble servant [signed] John Adams. President of Congress.

#archivesgov#December 6#1778#american revolution#war of independence#continental congress#john adams#18th century

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 1920 – IRA members and brothers Patrick and Harry Loughnane were abducted and killed by Black and Tan Auxiliaries at Kinvara, Co Galway.

County Galway saw its share of controversial incidents during the War of Independence. Most of these incidents were carried out by Crown Forces, specifically the RIC and a new force, the Auxiliaries, created in order to help the RIC in dealing with militant republicanism.

Patrick Loughnane (aged 29) was a local IRA leader and Sinn Féin secretary, he was also active in the local GAA. Harry (aged…

View On WordPress

#Auxiliaries#Co. Galway#England#Harry Loughnane#IRA#Ireland#Irish History#Patrick Loughnane#RIC#Shanaglish#War of Independence

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Are any of my followers familiar with Native American terms and terminology? Or know someone who is?

I'm from the UK and currently doing some research on a Welsh play from 1777 in which a character representing England is talking to a character representing a native group from Philadelphia. The play itself is possibly a satire on the American War of Independence. I'm aware of these historical events, but as I grew up in the UK I lack the cultural knowledge of these events. In Welsh, the character representing the native groups in Philadelphia calls her lands Caea (pronounced in Welsh phonetically as kai-ah). In Welsh the word 'cae' means field, perhaps this is relevant somehow?

Given that the text is from 1777, is in Welsh and seems to be making light of the atrocities of settlers towards native groups in America, it could just be a made up group name from some Welshman nearly 250 years ago. But I don't know nearly enough about Native American languages to connect the dots between any term or place.

I know enough to know that if there is a group being referred to here, they're likely speaking an Algonquin language. But I will be the first to say this is slightly out of my wheelhouse and would appreciate any help with this!

#I am also aware enough to know that Native American isn't the preferred term for every group#but I have used it here for consistency#Native American languages#algonquin#perhaps?#war of independence#native languages#indigenous languages#Philadelphia#pennsylvania#linguistics

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Malasaña and his daughter fight against the French in one of the streets leading down from the park to San Bernardo. 2 May 1808

by Eugenio Álvarez Dumont

The painting pays homage to two of the heroes who achieved the most legendary glory in the struggle of the people of Madrid against the French troops during the War of Independence. Thus, it illustrates the moment in which the guerrilla Juan Malasaña kills the French dragoon that has just murdered his daughter, the embroiderer Manuela Malasaña, who supplied her father with rifle cartridges to fight the French troops from her home, during the assault on the Monteleón park.

#eugenio álvarez dumont#prado museum#museo del prado#madrid#spain#spanish#art#painting#history#europe#european#france#french#napoleonic wars#peninsular war#iberia#war of independence#malasaña

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

September - Jonathan Groff as King George III

I’m taking an American history class, and Hamilton had already helped me so much 😅

September 3 - Treaty of Paris was signed

September 6 - Lafayette’s birthday

September 14 - Aaron Burr’s death

September 28 - Battle of Yorktown began

#calendar#september#2022#september 2022#jonathan groff#king george iii#hamilton#alexander hamilton#lin manuel miranda#aaron burr#leslie odom jr#marquis de lafayette#lafayette#daveed diggs#hamilton the musical#broadway#America#american history#war of independence#revolutionary war

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Outlander (2014-) Singapore

S7E5

At Ticonderoga, Jamie and Claire prepare for an imminent British assault. Roger compiles information about time travel while Brianna earns the respect of her coworkers.

*Rachel: You saved our lives. I don't know how to thank thee.

William: You can thank that rotten stew that I awoke to such terrible pain in my stomach.

#Outlander#2023 episode#Singapore#S7E5#Ticonderoga#drama#fantasy#romance#war of Independence#US#William#Rachel#Charles Vandervaart#Izzy Meikle-Small#tv series#period drama#based on a book#just watched

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

My mum: So he was this great irish hero who went down in history for-

Me: fighting the british?

My mum: fighting the british!

#ireland#irish#irish history#caramelfantic#colonisation#british empire#1916#easter rising#war of independence#oliver cromwell

6 notes

·

View notes

Link

I’ll just put this here for anyone else in today’s ten thousand.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is the 12 th of February

A very important day for Kahramanmaraş and Türkiye

About 100 years before, in 1920. The citizen fought for their independence against the French occupation, many people died but they were successful.

2023

Kahramanmaraş was shook by a devastating earthquake. Many lost their lives and their homes. But we need to stay strong. The story of the heroic city is still going on!

Happy Anniversary Kahramanmaraş, the beautiful and strong heroic city!

Stay strong like your citizen!

Ümitsizliğin ardında nice ümitler var ...

Karanlığın ardında nice güneşler var ...

There is hope after despair and many suns after darkness!

#12 şubat#war of independence#turkish independence#kahramanmaraş#Turkey#Türkiye#deprem#kahramanmaras depremi#earthquake#turkey earthquake#earthquake turkey

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Basics Of American Revolutionary War Uniforms:

Basic descriptions I wrote of each layer of a Continental Army soldier's uniform in order of what you'd put on first to what you'd put on last, starting with:

Shirts:

In the 18th century, a man with a shirt was considered naked, so the shirt was a part of every outfit (although it was often covered in other layers of clothing). The shirts worn by the soldiers in the revolution were designed to be as comfortable as humanly possible, so they were very long, often stopping mid-thigh or just below the knee, loose and flowy, and had lots of ruffles at the top. Shirts also had long, puffy sleeves. The shirts were so comfortable that they would function as nightgowns too. All a man had to do to get ready for bed was take off all of the other layers of his uniform. The shirts were plain white or a yellowish colour, depending on how many times they'd been worn. Collars were high but not as high as collars in the 1790s, and sleeve cuffs were either closed by cuff links (little button things) or they'd just have cute lace at the end. Contrary to some ridiculous but funny assumptions I've heard from people who don't study historical fashion, shirts were not hard to put on, and they were simply pulled over the wearer's head like you would put on any other shirt. Shirts were closed together using buttons (a favourite of mine), linen, thread ties, or different combinations of the forementioned. Buttons tended to be small and made out of either thread, horn, leather, or even leather. Because the shirts were made out of soft, thin materials such as linen, cotton, and light flannel and were worn all the time, they were usually the first clothing items to wear out and break. Due to supply problems, there were periods of time during the revolution where men had to wear their breaking shirts and couldn't replace them. Another thing about shirts that I read somewhere (can not find the source for the life of me) is that Washington told his soldiers to wear hunting shirts because he felt that they were practical in every kind of weather. However, the site did say that they only wore them towards the start of the war and in certain regiments.

Neck accessories (for lack of a better term):

Like I briefly mentioned with the shirts, people in the 18th century had a really weird idea of what counts as naked, and they believed that a man without any kind of neck covering over his shirt was still naked. Cravats and neck stocks were two commonly worn neck garments during the revolution. Cravats were made out of silk, linen, or cotton and could be put on in a range of different ways. When they were untied, they were simply long strips of fabric. There are many ways to tie a cravat. I'm not very good at explaining things, so if you need to figure out how to tie an 18th-century cravat, I recommend looking up a YouTube tutorial. Cravats could also be accessorised with cute brooches and such. There were two different, commonly worn in the continental army, types of neckstock in the 18th century. Number 1 was made of the same materials and had the same colour as a cravat, but number 2 was dark in colour and made of leather. The biggest difference between neckstocks and cravats is how you put them on. Neckstocks aren't meant to be tied like cravats; they have a buckle on one end, so they're meant to be put on more like a belt. Oh, and in case you're wondering, the buckle always goes at the back.

Stockings:

Oh my god, I could talk about revolutionary war stockings forever. They're actually so adorable and cutesy, and I just love them. So the stockings are the pretty little white tights that the 18th century seems to be known for, and they were mainly made via knitting and were made out of either wool, cotton, linen, silk, or a fabric blend of any of the aforementioned. Stockings were usually made using knitting machines, but there were still plenty of people who made them by hand. Stockings in the 18th century were not at all short either; they went above the knee (so basically thigh highs). One of my favourite parts about 18th-century stockings is the garters that secure them into place. The garters were belt things that would wrap around their legs to make sure the stockings wouldn't fall down, and they were usually made out of leather, cloth, lace, or a ribbon tied into a bow. I physically cannot speak of these things without saying aww in my mind.

Culottes:

Also known as knee-breeches, but lets be honest, culottes sound cooler. The culottes worn by 18th-century soldiers were a bit different; instead of having a line of visible buttons at the crotch area to put the culottes on like jeans, they had fewer buttons—usually about 1 or 2—at the top of the culottes, and those buttons would be hidden by the waistcoat. Culottes in the Revolutionary War had a much higher waistband; most culottes in the 18th century had a low waistband, but culottes of the Continental Army had a waistband that went just above the soldiers actual waist. And culottes never stopped lower than the shinbone (to show off the stockings). Culottes were white or off white and were made of either buckskin, elk, sheepskin, wool, linen, velvet, silk, or fabric blends of any of the aforementioned. Culottes were very tight because they were worn so that when the soldiers were riding their horses, which they did a lot, the horse needed to feel every movement of the leg so that it could understand what the rider wanted it to do, and that was much harder if the rider was wearing super loose, flowy pants. Culottes were closed at the side of the knee with more small buttons or ties. Buttons on culottes were usually made of either metal, leather, or horn and covered in cloth or wrapped in thread.

Waistcoats:

Although waistcoats with sleeves did exist in the 18th century, they weren't as popular as waistcoats without sleeves. Going back to the weird 18th century undestanding of what is nude, a man wearing breeches, a shirt, a cravat or neckstock, and an unsleeved waistcoat would still be counted as naked. This is one of the things I see a lot of period dramas get wrong. I understand the overcoat-less look looks cool and attractive, but in the 18th century, that would be like a man going outside wearing no clothes. Oh, and another thing that a lot of period dramas mess up on is that men did not show their shirt sleeves in public; that was considered crude and abnormal; it wasn't illegal, just something you'd get judged for. There were two sub-types of waistcoats: double-breasted and single-breasted. These sub-types actually have nothing to do with breasts at all. In fact, the sub-types are about buttons. Double-breasted means a waistcoat with two rows of buttons, and single-breasted means a waistcoat with one row of buttons. Back to the uniform of the continental army, at the start of the revolution, soldiers wore single-breasted waistcoats in the most popular style of the 1750s and 1760s, but by the end of the revolution, they'd switched to wearing the 1770s style waistcoat, just going by a general pattern I've seen in changes to parts of the uniform. I'm assuming that the switch would have happened in 1779. In case you're wondering, the difference between the 1750s–1760s style and the 1770s style is their length; the former stopped mid-thigh, the latter stopped just below the hip. Waistcoats were usually made of linen, wool, velvet, silk, or a fabric blend of any of the aforementioned. They were made with all different colours and patterns, but in the continental army, they wore beige and off-white waistcoats. The waistcoat buttons were made of horn, metal, or leather and were sometimes wrapped in thread or fabric to make them the same colour as the waistcoat.

Sashes:

Sashes are a detail of the continental army uniform that I see a lot of people (and sites explaining the layers of the uniform) skip over. Continental army sashes were very important because they showed the wearer's position in the army. Green means the wearer is an aide-de-camp or brigade major; pink means the wearer is a brigadier general or a major general; and finally, blue means the wearer is a commander-in-chief. This system was made by Washington in 1775 and was used by the army throughout the war. The sashes were likely made using silk or wool. There was another, separate system with sashes; colonels, lieutenant colonels, majors, captains, sub-alterns, serjeants, and corporals could wear a red sash around their waist. However, this system was likely an optional thing because I've seen many portraits of men in those ranks from 1775–1779—they ditched the system in 1779—and I've seen only one of them where the person is wearing one of the red waist sashes.

Overcoats:

At this point, you are no longer considered naked; congratulations. So there were two kinds of overcoats in the 18th century: frock coats and dress coats. Dress coats were for super-rich people, and frock coats were for everyone else. Dress coats didn't have functional pockets, and the only reason why people thought that they were better than a frock coat was that they were expensive and sometimes prettier. Frock coats had a double-breasted front (same definition as with the waistcoats), functional pockets, and a high, round neckline. You can probably guess what kind of coat the soldiers of the Continental Army wore. They wore blue wool and linen frock coats with large gold or silver metal buttons on the cuffs and facings. George Washington and his officers wore buff-coloured facings with thick buff-coloured cuffs, and most other officers wore red facings with red cuffs. The coats had coattails and stopped midthigh, but the whole button and facing thing stopped just below the hip. The overcoats had this interesting triangle coat tail design thing at the back that I tried to figure out how to describe, but I couldn't. Here's a picture of what I mean by the two different kinds of frock coats worn by the soldiers that I mentioned in this paragraph: the one on the left is the one worn by Washington and his officers, and the one on the right is the other one:

[image credit, Samson Historical and Common Threads: Army]

I have just been told the name of the triangle things, they're called vents and they're to make sure the soldiers could ride horses without messing up their uniform. :)

Epaulettes:

The epaulettes serve the same purpose as the sashes: to declare the wearers rank; however, epaulettes are much more confusing because the epaulette system changed halfway through the war. So, the epaulette system for 1776–1779 goes like this: commanders, major-generals, brigadier generals, colonels, lieutenant-colonels, and majors wore a gold epaulette on each shoulder; captains wore a single gold epaulette on their right shoulder; sub-alterns wore a single gold epaulette on their left shoulder; serjeants wore a red epaulette made of cloth on their right shoulder; and corporals wore a green epaulette made of cloth on their left shoulder. The system from 1779-1784 goes like this, commanders wore a gold epaulette on each shoulder with 3 silver stars, major-generals wore a gold epaulette on each shoulder with 2 silver stars, brigadier-generals wore a gold epaulette on each shoulder with 1 silver star, colonels, lieutenant colonels and majors wore a gold epaulette with no stars on each shoulder, captains wore a gold epaulette on their right shoulder, sub-alterns wore an epaulette on their left shoulder, senior non-commisioned officers wore a red epaulette made of cloth and adorned with a crescent moon shape made of brass on each shoulder, sergeants wore a red epaulette made of cloth on the right shoulder, corporals wore a green epaulette made of cloth on their right shoulder and lastly, privates wore no epaulettes.

Hats:

Tricorn, bicorn and round were a must. Round hats were hats that were cocked on one side, bicorn hats were hats that were cocked on two sides and tricorn hats were hats that were cocked on three sides. Most of the time Continental army soldiers pinned them and folded them on the sides. Soldiers carrying muskets wore the hat in a different way to normal civillians, civillians would have the hat the normal way, center point forward but when carrying a musket over their shoulder, soldiers would turn their hat so that the left part was facing forward. In this position, the two sides of the hat would be almost flat so they could sling their muskets over their shoulders without having to worry about knocking their hat off. The hats white edges were made using worsted wool braid and the hat itself if expensive was made of beaver felt or camel's down painted black and if it was cheap it was just made of black wool felt. Hats were not always worn, I'd say they were more of a formality because I have seen very few portraits of soldiers wearing them.

Hat Cockades:

Hat cockades were made of ribbon or wool and were a sort of decoration to be pinned to the wearer's hat. They were like sashes and epaulettes; they indicated the wearer's rank in the continental army. And the system changed in 1779. So the system before 1779 worked like this: subalterns wore a green hat cockade, captains wore a yellow hat cockade, majors and brigade majors wore a red hat cockade, colonels wore a pink hat cockade, and lieutenant colonels wore a green hat cockade. In 1779, they changed it to honour and celebrate America's military alliance with France, so the colourful insignia were removed, and instead every soldier, regardless of rank, wore a plain black and white hat cockade. French soldiers had a cockade with black in the middle, surrounded by white, and American soldiers had a cockade with white in the middle, surrounded by black. Later on, in 1783, the black and white cockades were named the union cockades and were to be worn on the left breast, close to the heart.

Shoes:

There were actually a few periods of time during the war where some of the soldiers didn't have shoes, such as during the Christmas Day crossing and the winter of 1777–1778. But when they were supplied with shoes (most of the time they were), they wore one of two styles. The classic 'little lad' shoes, as I call them, and riding boots 'Little lad' shoes were shoes made with black leather and secured with a buckle. Little lad shoes had a small heel bit at the bottom, likely meant to make the wearer look taller because, despite tall people being considered the most attractive, most people in the 18th century were very short. Riding boots had an even higher heel and a part at the top of the boots that could be rolled down to fit the wearer. When rolled down, they just look like normal riding boots but with brown cuffs at the top. Interesting shoe-related fact that I thought would be cool to put here: in the 18th century, they didn't make right or left shoes; they made what they called straights, and you were meant to switch which foot you wore them on every day to 'wear them off evenly'. Riding boots were made with leather and were black on the outside and brown on the inside. Riding boots were very tall (they went under soldiers' kneecaps) and worn for the same reason as culottes, to make horse riding easier. It's meant to prevent saddle pinching, have a sturdy toe to protect feet while on the ground, and have a big heel to prevent slipping through stirrups.

Hair:

Originally I planned on not mentioning it on this list because it's not something that you can wear but there were uniform rules about hair in the continental army so I guess it is technically part of the uniform. In the 18th century they viewed men with facial hair was considered wrong and unusual in normal day-to-day life so if course it wasn't acceptable in a military setting. In the continental army they had a rule that men needed to shave every three days. They went against this rule a few times but only when they were desperate. Now on the topic of hair as in, not facial hair, the hair on their head was usually tied into a low ponytail with a blue ribbon or - for some men - cut short. 18th century men LOVED their long hair and did not want to cut their hair short even though they were told it should prevent lice. Wigs and hair powder were fashionable in the 18th century but not many men could afford wigs and it's not like they had a ridiculous supply of hair powder so most of the time they had their natural hair colour showing.

It's important to note that this is just the standard uniform that most men wore; each regiment had its own unique uniform, so if your project has anything to do with a specific regiment, either do your own research or ask me about it in the comments or my asks. This is also post-1775 because 1775 had no uniform. If I have gotten anything wrong, please do not feel afraid to correct me in the comments, and I'll edit the post.

Sources:

https://historyofmassachusetts.org/uniforms-revolutionary-war-soldiers/

https://www.srcalifornia.com/flags/revuniforms1.htm

https://www.bostonteapartyship.com/uniforms-of-the-american-revolution

https://ufpro.com/blog/american-revolutionary-war-study-military-uniforms-across-battlefield

https://www.washingtoncrossingpark.org/continental-army-clothing/#:~:text=Over%20their%20shirts%2C%20soldiers%20would,unit%20a%20soldier%20belonged%20to.

https://www.crazycrow.com/site/tricorn-hat-history/

https://www.si.edu/object/george-washingtons-uniform%3Anmah_434863#:~:text=This%20blue%20wool%20coat%20is,buff%20wool%2C%20with%20gilt%20buttons.

http://www.colonialuniforms.com/revolutionary-war-coats.html

https://www.berkleyhistorical.org/revolutionary-war-uniform

https://www.samsonhistorical.com/en-ca/products/mens-riding-boots

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Riding_boot

#american revolution#american revolutionary war#amrev#american history#revolutionary war#history#historical fashion#fashion history#18th century#18th century fashion#continental army#military history#military uniforms#war history#war of independence#On-partiality's rambles

124 notes

·

View notes

Link

Israel is celebrating 74 years of independence on May 5 this year. The passage of time and the solemn black-and-white photos of the period lend a feeling that the historic events and the nascent country’s first footsteps were orderly, well-thought-out affairs.

But in reality, things couldn’t be more different: the country’s very name was hotly debated, the Declaration of Independence was far from ready on time and a state emblem was yet to be found.

Read More: Israel21c

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 1920 – Court-martial of Terence MacSwiney, Lord Mayor of Cork for possession of seditious articles and documents.

‘One armed man cannot resist a multitude, nor one army conquer countless legions; but not all the armies of all the empires of earth can crush the spirit of one true man. And that one man will prevail’. –Terence MacSwiney

Lord Mayor, Terence MacSwiney is under court-martial over which Colonel James, Staffordshire Regiment, presided, assembled at Victoria Barracks, Cork, under the following…

View On WordPress

#Brixton Prison#court-martial#England#Hunger Strike#Ireland#Lord Mayor#Lord Mayor of Cork#Portrait of Terence MacSwiney#RIC#Sinn Fein#Terence MacCurtain#Terence MacSwiney#War of Independence

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 4: Knight and Princess

Narrated by Jax.

~Content Warning: mention of death~

Narrator: With each step, I approached Yuka. Her tears ruined her makeup, and she had a helpless look in her eyes.

Jax: This kind of magazine doesn’t deserve you.

Yuka: Jax...

Narrator: The judges looked at me blankly, but I didn’t bother to look at them.

Jax: Why are you crying? Designing isn’t something you don’t have just because someone says you don’t.

Narrator: When the judges heard what I said, they grunted several times.

Editor: Ahem... Excuse me...

Narrator: I turned my head and glanced in the direction of the speaker.

Jax: Sitting there with a smile, watching a girl cry.

Jax: I wonder who here has a fake smile.

Roca: I’m telling the truth!

Jax: The truth? What is the truth?

Roca: You...

Narrator: I didn’t want to talk to them anymore and I whispered in Yuka’s ear...

Jax: I know you’re not lying. You don’t lie.

Narrator: I took Yuka by the hand and walked out of the audition room, leaving the people to look at each other.

Jax: When I release my album, I’ll put you on the cover.

Narrator: Yuka smiled when she heard this. I sighed and wiped away her tears. Then I handed her a helmet.

Narrator: Princess, let’s go home.

Narrator: Yuka put on the helmet and held tightly onto my waist.

Narrator: We left behind everything in this city.

Narrator: Yuka had calmed herself when we got home. She was too tired to speak. She fell asleep without hugging the bunny.

Narrator: The bunny was a little disappointed and it looked at me expectantly.

Jax: Hey, I’m not going to hug you.

Narrator: What? Is there something you want to ask me?

Choose “Why do you and Yuka look alike?”

You: What on earth is going on? Why do you have Yuka’s face?

Narrator: That’s a long story. Where should I start?

Narrator: Do you see this bunny?

Choose either “I did see it” or “Why ask?”

If “see,” ...

You: Of course I do.

Narrator: You can see it because we are in Yuka’s memories.

If “ask,” ...

You: Why did you ask all of a sudden?

Narrator: Because this bunny exists only in Yuka’s memories...

--

Narrator: Fluffy did grow up with Yuka, but it died when she was a child.

Narrator: Yuka didn’t want to believe it. So, she kept Fluffy in her memories.

Narrator: Did she ever tell you about her father?

Narrator: She must have told you that her dad worked in a shipping company and was always on a business trip.

Narrator: In fact, her father left for the War of Independence and never came back.

Narrator: When she was 18, Yuka received a very important letter that summer. As she opened it with joy, she found that it was...

Narrator: A rejection letter.

Narrator: But in Yuka’s memories, she received an acceptance letter, but she was not ready for a long journey.

Choose either “How do you know all this?!” or “Are you part of Yuka’s imagination, too?!”

If “know,” ...

You: So all this is her imagination? But what does it have to do with you?

Narrator: I am Yuka...

If “imagination,” ...

You: Are you trying to say... you are also a figment of Yuka’s imagination?!

Narrator: I’m another personality of hers.

--

Narrator: I seal away all the painful memories Yuka doesn’t need. To protect her and her fairy tales. That’s what I’m here for.

Narrator: Things such as hypocrisy or truth are not for others to see.

Narrator: It doesn’t matter if you don’t want to accept the so-called reality.

Narrator: Yuka works hard to find happiness in the fairy tale world she created. I have to protect that world.

Narrator: Now... Do you get it?

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

#yuka and jax#shining nikki#ssr designer#chapter 4#ninir#jax#yuka#memories#knight and princess#transcript#did/osdd#trauma#happy ending#protector#model#war of independence#apple independence war#death

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

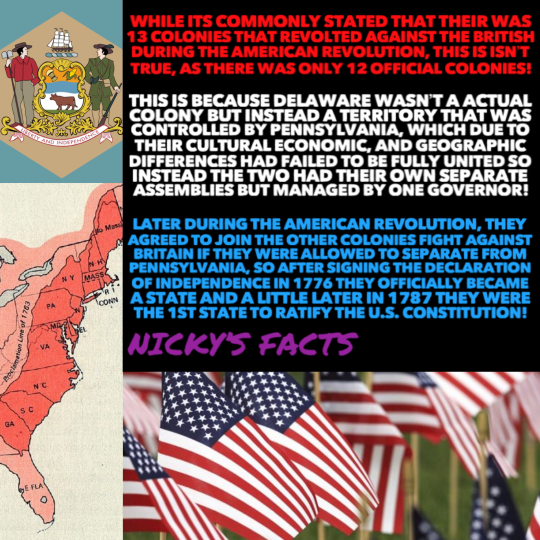

For Delaware the American Revolution was a fight for their independence on the agreement that they will be granted their independence!

🇺🇸

#history#delaware#united states#american revolution#american colonies#us constitution#4th of july#american history#war of independence#12 colonies#13 colonies#usa#fourth of july#declaration of independence#red white and blue#pennsylvania#delaware history#states#british colonies#patriots#american flag#independence day#nickys facts

3 notes

·

View notes