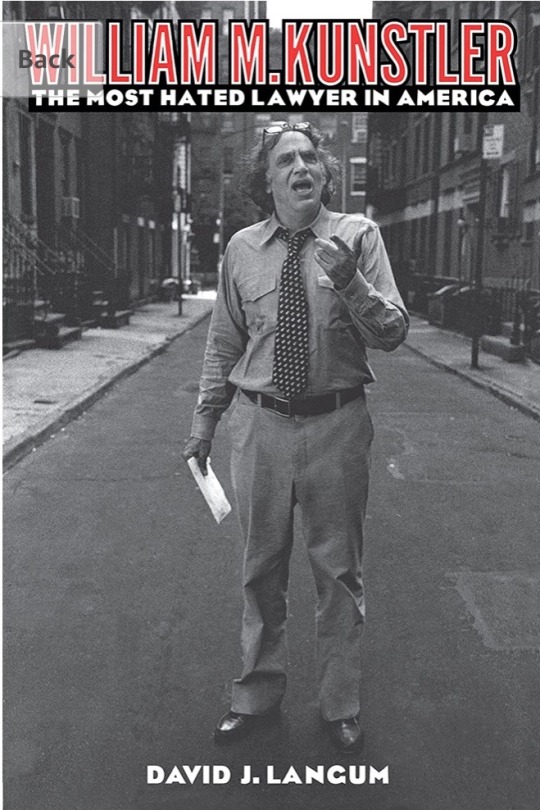

#William Kunstler

Text

Breaking news! 10,000 teens have the worst summer vacation ever in Chicago

#1968#chicago 1968#abbie hoffman#jerry rubin#phil ochs#dave dellinger#rennie davis#william kunstler#john froines#lee weiner#tom hayden

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Waterplace and WaterFire, pt. 2

This tiny park sits at the new confluence of the Woonasquatucket and Moshassuck rivers forms the Providence River. The old confluence was under the old post office. (Photo by author)

This post reprints the second half of Chapter 21, “Waterplace and WaterFire,” from Lost Providence. The Waterplace design by Bill Warner was so good that many experts were confused. It reminded me of the what several…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

The small town of Attica in upstate New York may appear quaint and subdued today. But it became infamous in 1971 — when the Attica prison riot exploded into the bloodiest prison uprising in U.S. history.

The four-day revolt began on September 9, 1971, and saw more than half of Attica's prison population take up improvised arms. At that point, their calls for improved living conditions had gone unanswered for months. So, 1,281 inmates decided to take matters into their own hands. They took 39 prison guards and employees hostage, hoping to negotiate with state politicians.

At first, it seemed like authorities were willing to cooperate. But when negotiations stalled, police made the fateful decision to launch a raid on September 13. On that day, a helicopter dropped tear gas from the sky — as state police rushed the yard and fired 3,000 rounds — killing 10 hostages and 29 inmates. By the time the uprising was over, 43 people were dead.

These 33 images capture the historic chaos of the Attica prison riot — and how it helped galvanize the prisoners' rights movement.

Meant to hold 1,600 inmates, the Attica Correctional Facility held around 2,200 at the time of the uprising — which led to overcrowding and the harried rationing of essential supplies. Many prisoners were limited to just one roll of toilet paper per month and one shower per week.

As one historian later wrote, "Prisoners spent 14 to 16 hours a day in their cells, their mail was read, their reading material restricted, their visits from families conducted through a mesh screen, their medical care disgraceful, their parole system inequitable, racism everywhere."

It was only a matter of time before tensions boiled over — and that's exactly what happened in September 1971. The riot began shortly after dawn on September 9, when inmates were supposed to be on their way to breakfast.

A small group of prisoners overpowered the nearby guards before charging through a shoddy gate and reaching "Times Square" — a central hub in the prison. Within moments, the initially small band of rioters swelled to 1,281 participants. They quickly began attacking prison officers with homemade shivs and clubs — and it was clear that the Attica prison riot had begun.

After burning down the prison chapel and taking over three cell blocks, the inmates encountered state police wielding tear gas and machine guns. While the authorities soon managed to regain control of the cell blocks, the rioters had already taken 39 prison guards and employees hostage outside.

At around 10:30 a.m., the prisoners settled in an exercise yard, blindfolded the hostages, and dug trenches into the soil. Drawing up their demands, they began delegating duties. Some prisoners would serve as security or medics. Others would serve as representatives to demand negotiations.

Titled The Attica Liberation Faction Manifesto of Demands, the prisoners' proposal listed 33 requests, including better medical treatment, more religious freedoms, "an end of physical abuse for basic necessities" like daily showers, and more than one monthly roll of toilet paper.

The five inmates elected to wield negotiation power called for outside observers to aid in the talks. These included lawyer William Kunstler, New York Times columnist Tom Wicker, Minister Louis Farrakhan, and Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale. While some like Farrakhan declined the invitation, others like Seale agreed to meet with the prisoners.

New York Commissioner of Corrections Russell Oswald eventually agreed to 28 of the demands. Though negotiations moved forward, the prisoners' demand for amnesty for the uprising — and some other requests — proved a bridge too far. On the night of September 12, both Oswald and Governor Nelson Rockefeller decided that force was needed to retake the prison.

How The Police Took Attica Back By Force

Santi Visalli Inc./Getty ImagesThe aftermath of the Attica prison riot on September 14, 1971.

It was 8:25 a.m. on September 13 when Oswald delivered the prisoners a final written warning. It demanded their full surrender — but instead saw them put their blades against their hostages' throats. State Police and National Guard troops lined up outside the gates while the inmates dug into their trenches. Helicopters soon appeared at 9:46 a.m.

With tear gas flooding the yard, hundreds of State Police troopers, Attica correctional officers, sheriff's deputies, and park police officers rushed the field. Brandishing shotguns loaded with buckshot and Geneva Convention-violating unjacketed ammunition, they laid waste to the prisoners.

Thousands of rounds were fired into the yard, killing 10 hostages and 29 inmates and wounding 89 others. One emergency technician witnessed a state trooper shoot a wounded prisoner lying on the ground in the head. Another inmate was shot seven times and then ordered to keep crawling.

By 10:05 a.m., it was all over. "On a much smaller scale, I think I have some feeling of now of how Truman must have felt when he decided to drop the A-bomb," reflected Oswald after the massacre.

Both Oswald and Rockefeller initially claimed that all 10 dead hostages had been killed by the inmates, but autopsies quickly showed that the state had recklessly gunned them down. The death of one prison guard had been correctly attributed to the prisoners — as well as the deaths of three other inmates — but those deaths had happened early on in the uprising.

Ultimately, the Attica prison riot led to nationwide demonstrations in support of prisoners' rights. It also spawned a congressional investigation and a $2.8 billion class-action lawsuit that represented the inmates involved.

Decades later, an $8 million settlement was to be split among just 502 inmates who were involved in the uprising. A further $12 million would be paid out to prison guards and their families in 2005.

Despite the notoriety of the uprising, it did not make nearly as much of an impact on the U.S. prison system as some activists were hoping. Though it did lead to some changes in regard to prison reform — most notably more religious freedom behind bars — many of the inmates' demands for better conditions were either ignored or put into place and later reversed due to the "tough on crime" era of the 1980s and 1990s.

It's little wonder why many prisoners and prisoners' rights activists are still fighting for many of the same things today — such as better wages for prison work and better medical treatment — as they did decades ago.

#attica prison#attica massacre#prisoners in america#american prisoner treatment#new york#prisoner rights#33 Pictures Of The Bloody Attica Prison Riot That Left 43 People Dead#How The Attica Prison Riot Exploded In 1971#new york state troopers

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

#The Trial of the Chicago 7#Aaron Sorkin#Eddie Redmayne#Yahya Abdul Mateen II#movies#movie review#movie#film review#film#movie critic#film critic#film criticism#movie criticism#Tom Hayden#Mark Rylance#William Kunstler#Sasha Baron Cohen#Abbie Hoffman#abbie hoffman

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Politically impotent, but highly entertaining courtroom drama

(Review of ‘Trial of the Chicago 7’)

*Warning: contains minor spoilers*

To say that the autumn release of Aaron Sorkin’s ‘The Trial of the Chicago 7’ felt timely following a summer of numerous instances of police brutality against peaceful #BlackLivesMatter protesters would be an understatement. To say that Sorkin’s high speed courtroom drama is revolutionary in any way whether as a film or a contribution to a political debate would - on the other hand - be a serious overstatement. From the sharply constructed and fast paced opening sequence where all our main characters are introduced with fast editing, upbeat music and brilliantly written shifting dialogue, Sorkin’s main mission (or ultimate fate) is clear: ‘Trial’ should above all be entertaining filmmaking.

Its story does not seem as the obvious fit for an entertaining story, however. In the shadows of the Vietnam War’s growing number of fatalities, various protest groups plan to come to Chicago in 1968 for the Democratic Party Convention to voice their contempt towards the US’ involvement in the war and the military service procedures. The protests, however, end in violent confrontations with the Chicago police. In the aftermath of these confrontations the leaders of the different protest groups are prosecuted for inciting riot and breaking various other laws. It is the battle between the Nixon administration and their oppositions represented by Students for a Democratic Society, the Yippies, several smaller figures and for some reason Bobby Seale and the Black Panthers (actually making it the Chicago 8), although they did not take part in the protests. The film follows their trial at the hands of eccentric and controversial Judge Hoffman combined with flashbacks to the events of the protest.

The film won the SAG ensemble award and that stands perhaps as one of the single least surprising awards of this awards season. ‘Trial’ is - as hinted at by the title - an ensemble piece if there ever was one. The film has no real lead, although Eddie Redmayne as Tom Hayden (SDS), Sacha Baron Cohen as Abbie Hoffman (Yippies) and Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Richard Shultz (Prosecutor) might be at the centre of attention. All involved actors have clearly had a good time with their roles portraying them with great enthusiasm, but for most parts also some degree of limitations.

Redmayne’s Hayden is the typical “good guy” who forgets to stay seated when the group protests the judge and continues to argue with Abbie about their political opinions and especially the manner in which they want them implemented. Redmayne does a decent job, but Hayden never really unfolds as a fully fleshed character to me. I do not feel that Redmayne ever really becomes his character and that is main reason why I never fully connected with him. Baron Cohen has run away with most attention for his portrayal of Abbie Hoffman, which I think partially is down to the fact that he is a somewhat unusually dramatic role for the Borat-actor. Cohen is without a doubt a better actor than he might be acknowledged as, and Abbie allows him a chance to show that. It is, however, still in combination with his classical sarcasm and wit that Cohen fully succeeds with his character. Through a returning stand-up routine throughout the film, Cohen’s Hoffman functions in some ways as a narrator and might be the closest we get to a leading role. He also gets to deliver the most touching lines of dialogue in my opinion as he takes the chair towards the end. Finally Gordon-Levitt tries his best to convey the mixed emotions and increasing doubt as Schultz faces the choice between blind loyalty and his devotion to the law. While I always love to see Gordon-Levitt on the screen, I cannot help but feel that Schultz as a character feels highly constructed and I had a hard time believing him to be that sympathetic towards the Chicago 7.

In many ways, I found Mark Strong as Jerry Rubin, John Carroll Lynch as Dave Dellinger and Mark Rylance as the defendants’ attorney, William Kunstler, to be more fascinating characters than both Hayden and Schultz in particular. Mark Strong continues to be more and more interesting and his Jerry Rubin is easily the most enjoyable character along with Cohen’s Hoffman. Strong, too, manages to balance the vulnerability of the sometimes blue-eyed Yippies with their sarcastic distancing and humour-driven protests in the courtroom. I actually believed in his character, when both the protests and the juridical proceedings become too overwhelming for him and he snaps in various ways. Carroll Lynch is an almost criminally underused actor and here I, too, would have liked to explore his character more as he feels so different from the remaining defendants. With the limited material he gets, he manages to create a sympathetic character. The same can be said about Rylance, who uses all of his theatricality as be battles with Frank Langella’s overdone Judge Hoffman. Langella gives it everything and then some to make Hoffman as unscrupulous, derailed and amoral as possible, which ultimately cooled my resentment towards him. He ended up feeling like a caricature more than an actual character and for that, way less scarier.

How come - despite all the characters’ flaws and limitations - that the film is still entertaining, then? Well, the main answer is Aaron Sorkin. While he is still to fully proof himself as a director (Molly’s Game also had some issues), he still is one hell of a writer. You can accuse him (rightly so) of over-writing his stuff, taking to many freedoms with his source material and balancing on the edge of using too much pathos, but it is hard to resist his razor sharp dialogues and tongue-in-cheek one-liners. He is no stranger to courtroom dramas and it is clear that he is on home-turf with all of these juridical and political exchanges of beliefs. For this reason, alone, ‘Trial’ never feels dull or slow. Additionally, this is aided by an often fast-paced editing and the fact, that it never dwells to long on one point before moving on to the next.

This, however, also stands as the main reason as to why the film never feels anything other than impotent as a political work. It never gets too dangerous or too controversial. It gets most dangerous, when it comes to the inclusion and portrayal of Bobby Seale and the Black Panthers. As Seale, extremely talented Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, is highly forgettable mainly down to the fact that Seale is reduced to a prop in the overall story. During the film, the court is accused of including Seale in the trial in order to scare the jury with a black man; adding a layer of racial injustice to the story. But in reality, it also feels as if Seale’s story line has been added to the film to “tick off” the race box; Fred Hampton is also thrown in there as Seale’s legal counsellor with his untimely death just briefly touched upon. The story of Seale, Hampton and the Panthers deserve more time, more attention and more gravity than given here; an initial opinion of mine that was only made clearer after watching ‘Judas and the Black Messiah’.

Ultimately, ‘The Trial of the Chicago 7’ is a highly flawed film and as a political work it stands as oddly harmless and undaring considering its timing and topic. However, thanks to another fast paced and sharp script by Aaron Sorkin, inspired performances from its all-star ensemble lead by Baron Cohen and Jeremy Strong and interesting plot it ends up as a highly entertaining courtroom film. A well-looking, satisfying meal, although it does not last for too long and leaves a somewhat questionable taste in the very back of my mouth.

4/5

#Film#Movie#Film Review#Movie Review#The Oscars#Oscars 2021#Oscars Warm Up#The Trial of the Chicago 7#Aaron Sorkin#Sacha Baron Cohen#Abbie Hoffman#Eddie Redmayne#Tom Hayden#Joseph Gordon-Levitt#Richard Schultz#Jeremy Strong#Jerry Rubin#John Carroll Lynch#Mark Rylance#William Kunstler#Frank Langella#Judge Hoffman#Yahya Abdul Mateen II#Bobby Seale#Best Picture#Best Actor in a Supporting Role#Best Cinematography#Best Film Editing#Best Original Song#Dave Dellinger

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

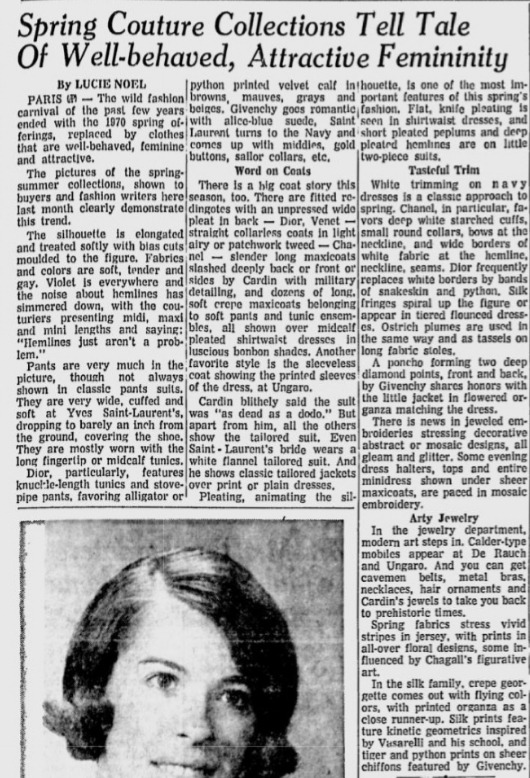

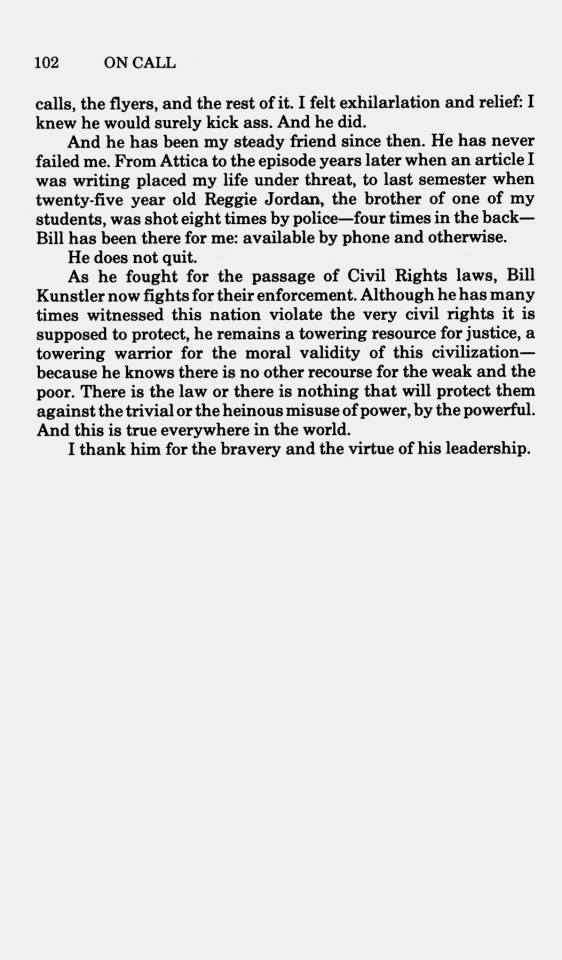

June Jordan, Black People and the Law: A tribute to William Kunstler, March, 1985; in On Call. Political Essays, South End Press, Boston, MA, 1985, 99-102

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

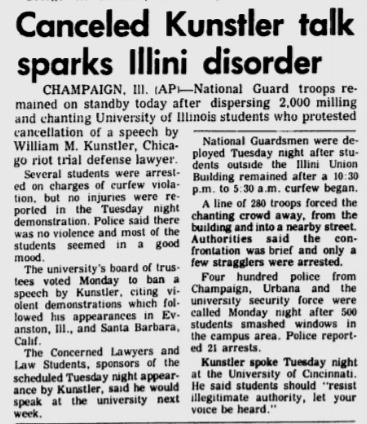

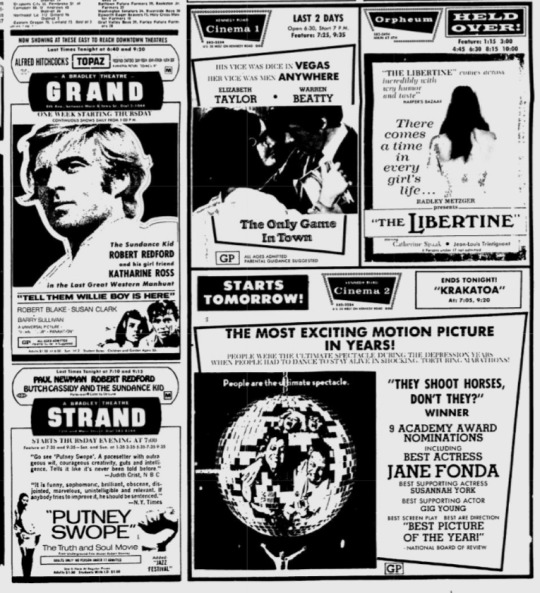

March 4, 1970

#1970#vietnam war#laos#pat nixon#ted kennedy#william kunstler#black panthers#black panther party#polish jokes#movie ads#civil rights#spiro agnew#ireland#puerto rico

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

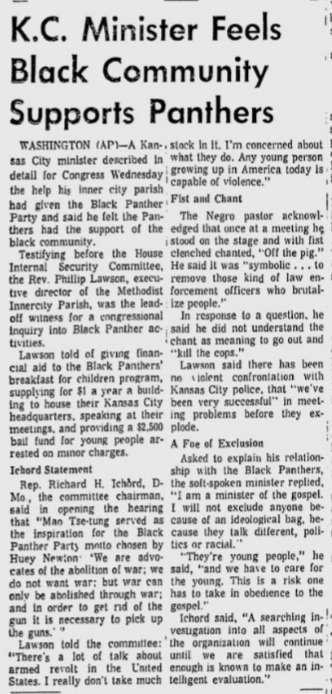

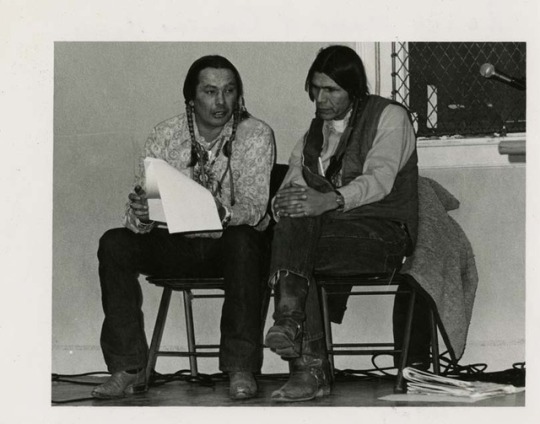

American Indian Movement (AIM) co-founder Dennis Banks recently passed away in Minnesota. An American Indian teacher, leader, and activist, he visited the Macalester College campus twice in the 1970s.

Top: Banks visited campus in September 1974 in support of students who took over an administrative building to protest cuts to the college’s Expanded Educational Opportunities program.

Photo by Paul Shambroom, Class of 1978

Bottom: Banks (right) and Russell Means (left), another prominent AIM member, visited campus in March 1974. Along with William Kunstler, the lawyer representing them at the Wounded Knee trial, the three spoke in the Mac gym about land, treaty rights, and conspiracy laws.

Photo by Gary Rubin, Class of 1974

#heymac#macalester#aim#american indian movement#dennis banks#russell means#william kunstler#expanded educational opportunities#eeo#protest#takeover

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Goodbye Paul Krassner

Paul Krassner, editor of The Realist and a co-founder of the Yippies, died yesterday at 87. There are undoubtedly many detailed obits on other sites, so I’ll confine myself here to a brief recollection of the single hour I spent interviewing him in 1978. It was at the American Heroes Conference in Sun Valley, Idaho, which was sponsored (I believe) by the producers of the godawful, and deservedly…

View On WordPress

#American Heroes Conference#BSU Arbiter#God#John F. Kennedy#Lyndon Johnson#Mike Hughes#One nation under god#Paul Krassner#The Realist#Timothy Leary#William Kunstler#Yippees

0 notes

Text

“Higher Education” or “Lowered Education” through the magic of “Distance Learning”

Higher education committed suicide with its dual racketeering model. First was the college loan racket, in which schools colluded with the federal government to jam too many “customers” through the pipeline who didn’t belong there, and who buried themselves under a lifetime debt obligation they could never escape. The second was the intellectual racket of creating sham fields of study that contaminated all the other “humanities” with poisonous bullshit theory, and eventually even invaded the STEM disciplines. Covid-19 screwed the pooch on all that, scotching the four-year party-hearty in-residence part of the deal. For now, who needs an online class in Contemporary Sexual Transgression ($2000-a-credit) when you can just click on Porn-hub for free? Hundreds of colleges and universities will be going out of business in the years ahead.

https://kunstler.com/clusterfuck-nation/things-going-by/#more-12866'

0 notes

Text

the law of attraction: de minimis

a quackity x reader law school au

part one, chapter one

[PREV] | [NEXT]

.

The first myth about law school is that everyone is the same.

In movies, in TV shows, in books- everyone in law school is a certain type of person. Dangerously smart, hardworking to a fault, and absolutely cutthroat.

Now, that is true. To get this far, to get into a competitive law school and make it to your final year, you have to be all of the above. Smart, hardworking, and just a little cunning. It’s impossible to get a leg up unless you’re standing on someone else’s knee.

Or neck.

However, the fact that everyone here has to have a certain few traits in order to survive does not mean that they cannot have other traits.

Some are louder, exuberant, and competitive- the type to yell out the answer to a question before raising their hand, the type to go back and forth with the professor when they’re sure they’re right (and they’re not). There’s the introverts, the sly ones you never see coming, who you barely notice next to you all year until you glance over at the grade on their final and it’s a 110%, somehow.

Of course, there’s also the in-between. The respectable ones, the students that are just there to get through the classes they need and get a respectable job at a respectable law firm and make something nice out of their lives.

Or the hero type, the ones that are convinced they can fix any injustice they perceive in the world- the environmental lawyers, the criminal defense lawyers, the civil rights lawyers. They might be right, too, which is why it seems like a never-ending flow of them are pouring into the school at each orientation.

It’s not always as simple as that, of course. You, like many students, are a mix of a few types. You lie somewhere between the exuberant and introverted sides, not shy about answering questions in lectures, but not jumping the gun to cause discourse, either. A bit of a hero type, you must admit, but you do pride yourself on being reasonable when it comes to your life’s expectations. You don’t expect to become some William Kunstler. You work hard, you get shit done, and like law school has a tendency to do, it seems to become your whole entire life.

The type of person you never quite got a read on is Alex.

He’s been sitting next to you in your upper level criminal procedure class for the entire semester. A whole semester’s worth of lectures means you have plenty of time to observe and analyze the people in your classes- its not like there’s anything else to do when the professor is going over voir dire for the third hour that week.

You pegged the kid in the third row as a die-hard businessman. He’s not going into law to help people, he’s going into law to make the most profit off of the most vulnerable clients he can find. The girl in row six, however, is definitely the hero type, judging by her “save the oceans” stickers on her giant re-usable coffee cups.

Alex, though, you can’t read. He dresses down compared to the other students. They dress up to hide their shortcomings, like their fancy coats can stop them from feeling bad about their less-than-adequate qualifications for the internship they just applied for. Others just like to lean into the New York City aesthetic and dress like they’re already lawyers, even despite failing their last midterm. You fall into that category- you can’t help it, it’s a fun look- but hey, you definitely didn’t fail your midterm, and you’ve lived in New York your whole life, so you think you have the right to dress like that.

Alex dresses like he has nothing to hide. He dresses like the young, high-level professor who is always cracked out on Redbull and hasn’t graded a paper in his life; like the cute, fascinating barista at the local hipster coffee shop you can barely afford. He dresses like that one guy you’d see on the subway one day and never manage to forget because of how his eyes met yours for a split second.

To be fair, that is kind of how it’s gone. It’s not exactly like the two of you met on the subway, and you’ve definitely interacted more than just a passing glance, but goddammit is Alex stuck in your head.

You convince yourself it’s just because he’s such a mystery. It’s not because he has really sweet brown eyes, or the most charming, unruly hair you’ve seen this side of the Midwest. It’s not because he whispers a joke under his breath whenever your professor says something stupid, or because he bumps your ankles together and shares an amused glance with you when that one really annoying kid pipes up with an opinion no one wanted.

It’s just because you don’t know why he’s here, and you don’t know what he wants, and you don’t know how to read him.

It bugs you. It gets under your skin- not like an itch, more like a hum. He’s on the back of your mind constantly, like you’re trying to subconsciously figure out what’s up with him, but to this day you’ve had no success.

It’s not like you think about anything substantial in regards to him- every time your traitorous brain brings him up, you put it down quicker than it came up. Getting attached to people is dangerous in the best of circumstances, but getting attached to the absolute enigma of a guy in your criminal procedure class who you can’t even confidently say is named Alex would be equivalent to signing up for heartbreak.

“Don’t date law boys,” your roommate had lamented after she had done just that, laid across her rose-pink bedspread with a sleeve of crackers clutched in one hand and a tissue in the other. She had then blown her nose unattractively. “Lawyers have a reputation for being soulless for a reason. They’re only here for themselves. Fuck them.”

Despite that, you find yourself friends with Alex. As if you’d be able to resist the self-satisfied grins he flashes at you when the professor praises him for a particularly poignant answer, or the way he holds his hand out under the table for a high-five after you nail the answer to a cold call. You barely know anything about him, and yet, you know enough to decide he’s a good person.

“Alex”, whose name you’re only about 80% sure of- maybe it’s short for Alexander, but you thought you’d heard someone he was on the phone with call him Q, so maybe he’s a Quinn or a Quentin?

“Alex”, who shows up looking more comfortable than you’ve been in your entire life, and still manages to hold an air of confidence around him that you’d not be able to master even in your finest long coat and shirt.

“Alex”, who seems determined to wiggle his way into your heart in any way he can.

“Alex”, who you seem to be powerless to resist.

.

This growing attachment to Alex of yours is only strengthened with each lecture. You share this class three times a week, two hours each on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. It’s a focus class, meaning that anyone who wants to go into criminal work should take this course. It’s challenging, it’s competitive, and it’s cutthroat.

And it’s only February.

A cold Monday morning in February, in fact, with the clock above your professor’s desk ticking obnoxiously as the big hand nears the 8. Outside, it’s downright miserable: windy and foggy. The outside of the paneled windows of the classroom are glazed in a sticky frost, reducing the figures of passing students to dull blobs as they hurry through the whipping wind to get to their classes.

The big doors at the back of the classroom close with a bang that reverberates throughout the lecture hall, cutting through the murmuring chatter of the students who are already here. Out of the corner of your eye you catch a flash of green- as you suspect, it’s Alex. He always takes the seat on the very end of the row, and you the one immediately to his right. You look up at him with what you hope is a casual smile, but the one he returns is so bright it could probably melt the frost off of the windows.

“Hey!” he says, too awake for 8 in the morning, and sets his binder down on the desk with a clatter. The whoosh of air rustles the paper of your notebook, which you smooth back down habitually. You watch Alex longer than you should, only tearing your gaze away after you notice the smattering of tiny snowflakes that have gathered atop the beanie he’s wearing.

You stifle a little laugh. This guy wears a beanie to law school.

Out of the corner of your eye, you watch as he settles into his seat. He shrugs off his hunter green jacket, leaving him in just a gray hoodie, dotted with darker spots from melting snowflakes that’d been blown into him. He drops his outer jacket across his lap just as the room goes silent, your professor walking up to his desk.

As the last tails of conversations die off, you turn to Alex, unable to help yourself, “You have… snowflakes, on your head.”

He glances at you, a little huff of laughter escaping him as he brings up a hand to smooth over the beanie. The snowflakes are swiped off, melting on the heat of his hand- you wonder how it would feel held in yours, probably warm, he looks like he runs hot- and you pry your eyes away as he straightens out his beanie and tucks his hair up into the brim of it. He misses a strand, and the black swoop stands out sharply against the frost-paled skin of his face.

“Happy February,” your professor begins, his microphone crackling to life. “The month of love, is it not? Just two weeks until Valentines day.”

He swings his bag up onto the stool next to him, the sound echoing through the microphone. He turns to face the lecture hall, arms spread as if welcoming you all to a talk show.

“I’m about to ruin all of your Valentines Day plans. Welcome to the start of your final project: the mock trial.”

.

#quackity#alex quackity#quackity x reader#quackity x you#quackity x y/n#quackity imagine#quackity fanfiction#quackity headcanon#quackity fluff#mcyt#mcyt x reader#mcyt fanfiction#sage vs the law of attraction#sage vs the law of attraction qxr#sage vs quackity#law school#lawyer#law school au#quackity au

386 notes

·

View notes

Text

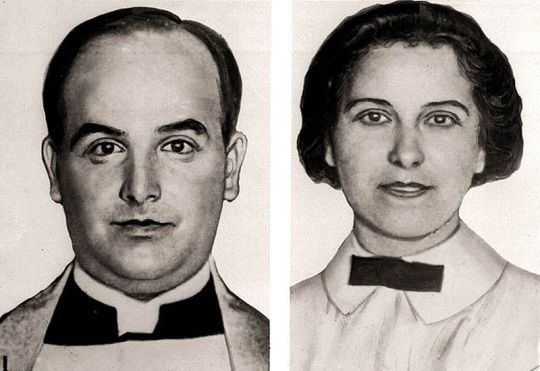

The Hall-Mills Murders

July 02, 2021

Edward Wheeler Hall was born in 1881 in New Brunswick and became a Episcopal priest. Edward was having an affair with a woman named Eleanor Mills, born in 1888, who was the wife of James E. Mills.

Eleanor Reinhardt was married to James E. Mills. They lived at 49 Carman Street in New Brunswick, New Jersey. The couple had two children, Charlotte and Daniel Mills.

Edward Wheeler Hall married Frances Noel Stevens on July 20, 1911. He was raised in Brooklyn, New York, receiving his theological degree in Manhattan. After graduation, he moved from New York to Basking Ridge, New Jersey, then to St. John the Evangelist Episcopal Church in New Brunswick. Edward was living at 23 Nichol Avenue in New Brunswick at the time of the murder.

On September 16, 1922, both the bodies of Edward and Eleanor were found in a field near a farm. Both of them were found on their backs, had been positioned side by side after they had been shot in the head with a .32 caliber pistol. Edward had only been shot once though, and Eleanor had been shot three times. Both of them had their feet pointing towards a crab apple tree. Edward had a hat covering his face and his calling card was placed at his feet. There were also torn up love letters placed between their bodies.

Eleanor was found wearing a blue dress with red polka dots, black silk stockings, and brown shoes. Her blue velvet hat was found on the ground near her body and her brown silk scarf was wrapped around her neck. She had a bruise on her arm and a tiny cut on her lip. Her left hand had been positioned to touch Edward’s right thigh. Four years after the murder an autopsy revealed her tongue had been cut out.

Edward was positioned in a way in which his right arm was touching Eleanor’s neck. He was wearing a pair of sunglasses and his hat was covering the gunshot wound on his head. He had a small bruise on the tip of his ear and abrasions on his left little finger and right index finger. There was also a wound 5 inches below his kneecap on the calf of his right leg. He was missing his watch and there were coins found in his pocket.

The bullet had entered Edward’s head over his right ear and exited through the back of his neck, while Eleanor had been shot under her right eye, over her right temple and over her right ear. Eleanor’s throat had also been severed with maggots already in the wound. The death had occurred at least 24 hours earlier.

The investigation became difficult, as it occurred. near the Middlesex County and Somerset County border. The New Brunswick (Middlesex County) police arrived at the scene first, but because the crime scene was in Franklin Township (Somerset County) these officers also showed up. While authorities tried to decide what county police should take over, many on-lookers came upon the crime scene and took souvenirs. They also passed around Edward’s calling card, thus contaminating the scene.

The main suspects were Edward’s wife, Frances Noel Stevens, her two brothers, Henry Hewgill Stevens and William “Willie” Carpender Stevens, and her cousin, Henry de la Bruyere Carpender. The 1922 investigation led to no indictments.

There was a second investigation ordered in 1926 after comments made by a man associated with one of Frances housekeepers came to light. Henry Carpender won a bid to be tried separately from the others and was ultimately never tried.

The trial began on November 3, 1926 in Somerville, New Jersey. It lasted about 30 days and gained national attention, largely because Frances’ family was quite wealthy.

A key witness named Jane Gibson came forward. She was a pig farmer and her property was where the bodies of Edward and Eleanor were found. The defense portrayed her as crazy and her story varied. Jane had given a different story to the police, the newspapers and at the trial.

Jane had told investigators that her dog had been barking loudly around 9pm on the night of the murder. Jane had gone outside and saw a man standing in her cornfield. She went to approach the man and as she got closer she claimed she saw 4 people standing near a crab apple tree. She then heard gunshots and one of the people fell to the ground. She heard a woman scream “Don’t!” three times. She said at that point she turned around and went back to her house, hearing more gunshots. She looked back at the tree and saw a second person fall to the ground. She testified that she heard a woman shout “Henry.”

There was not enough evidence to convict Frances and the others despite Frances having a motive for the killings. Many believe that she knew of her husband’s infidelity. The prosecution believed that Frances brother, Henry, was the one who fired the shots, though Henry claimed he was fishing miles away at the time of the murder and there were three witnesses who supported his alibi.

Frances’ cousin, Willie Carpender, owned a .32 caliber pistol, exactly like the one that was used to kill Edward and Eleanor. However, the firing mechanism on his pistol was apparently supposed to have been filed down so that he would not be able to hurt himself with it. The prosecution said that his fingerprint was found on Edward’s calling card.

Willie was unable to hold a job and he spent most of his time hanging out at the firehouse. It is believed now that Willie most likely was autistic, though no official diagnosis was ever made.

The case got so much media attention, and had been the most reported case in New Jersey history until the Lindbergh baby kidnapping happened in 1932.

An attorney and liberal activist named William Kunstler published a book titled “The Minister and the Choir Singer” in 1964 which he then re-released with more material in 1980 as “The Hall-Mills Murders.” In the book, he had his own theory that the Ku Klux Klan was responsible for the murders, based off the fact that the KKK was very active in New Jersey in the 1920′s. William acknowledged that they had not previously killed anyone in New Jersey and his reasons for thinking they would kill this couple were not very evidence-based.

Still to this day, the true identity of the killer is unknown and is likely to stay at that way as everyone involved in the case has since passed on.

#UNSOLVED MYSTERIES#unsolved#unsolved murder#unsolved true crime#true crime#Crime#murder#infedility#affair#couple#new jeresy

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books, January - February 2021

The Office of Historical Corrections - Danielle Evans *

Band Sinister - KJ Charles [mortifying certainty that the reason I like this one so much is because I want someone to tell me I’m lovely and then suggest some nice, affirming debauchery] *

The Dark is Rising - Susan Cooper *

The Once and Future Witches - Alix E. Harrow

Get a Life, Chloe Brown - Talia Hibbert

The Times I Knew I Was Gay - Eleanor Crewes

The Privileged Poor: How Elite Colleges are Failing Disadvantaged Students - Anthony Abraham Jack

Emotionally Weird - Kate Atkinson *

Well Met - Jen DeLuca [much like a Ren Faire, shamelessly enjoyable with only occasional moments of horrified second-hand embarrassment! (95% delightful; 5% the reenactors’ version of a kiss cam: hard no)]

The Knocker on Death’s Door - Ellis Peters

Rose Daughter - Robin McKinley

Kenda Mũiyũru = The Perfect Nine: The Epic of Gĩkũyũ and Mũmbi - Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

An Intimate Economy: Enslaved Women, Work, and America’s Domestic Slave Trade - Alexandra J. Finley

Unfit to Print - KJ Charles

How Much of These Hills is Gold - C. Pam Zhang

The World Only Spins Forward: The Ascent of Angels in America - Isaac Butler and Dan Kois [what I learned from this book: I have never, not once, not even for a single day of my life, been well-rested enough to handle Tony Kushner; the man sounds exhausting]

Plain Bad Heroines - emily m. danforth

Death to the Landlords - Ellis Peters

Well Played - Jen DeLuca [NO, STACEY, DUMP HIS ASS, OR AT LEAST TAKE A MORE SUBSTANTIAL PAUSE FOR SOME SERIOUS CONVERSATIONS ABOUT ETHICS (also, overall a very Second Book book: the world feels insubstantial, because it’s coasting on the settings and characters established in the first)]

Such a Fun Age - Kiley Reid [that last sentence, holy shit]

The King at the Edge of the World - Arthur Phillips

Take a Hint, Dani Brown - Talia Hibbert [awwwwwww <3]

Arctic Dreams: Imagination and Desire in a Northern Landscape - Barry Lopez [I kept thinking about what this book would be like if it had been written today, with the benefit of almost 40 more years of indigenous scholarship and decolonizing methodologies: you can feel it almost getting there...but not quite. And then there’s the accumulated data about climate change; it is wild to read a book about the Arctic where the presence of ice is assumed to be permanent, and the primary environmental concerns are very localized questions about the possibility of industry changing habitat. But then there are phrases like this: “The individual’s dream, whether it be so private a wish as that the joyful determination of nesting arctic birds might infuse a distant friend weary of life...”]

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue - V. E. Schwab [manic pixie dream boy; AO3 house style; dnf]

In Winter’s Shadow - Gillian Bradshaw

Borrower of the Night - Elizabeth Peters

Dragonsbane - Barbara Hambly

A Memory Called Empire - Arkady Martine [on rereading: my very favorite details are the nicknames, maybe Map most of all (Map!!)] *

Glass Town: The Imaginary World of the Brontës - Isabel Greenberg

Second Nature: A Gardener’s Education - Michael Pollan

World Made By Hand - James Howard Kunstler [White Men And Their Problems (Post-Oil Edition); very bad, not entertainingly; dnf]

The Liar’s Dictionary - Eley Williams *

A Taste of Honey - Rose Lerner [look, all I’m saying is that if you’re going to use your commercial kitchen implements in such a fashion, you’d better have made that a dedicated pegging pestle]

On Looking: Eleven Walks with Expert Eyes - Alexandra Horowitz

City of Gold and Shadows - Ellis Peters

Temporary - Hilary Leichter

Bitter Orange - Claire Fuller

All or Nothing - Rose Lerner

Busman’s Honeymoon - Dorothy L. Sayers

Interior Chinatown - Charles Yu

The Gentle Art of Fortune Hunting - KJ Charles

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

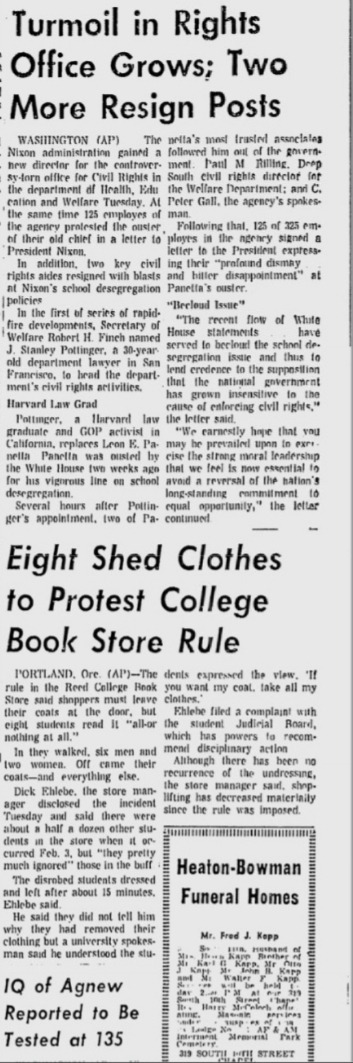

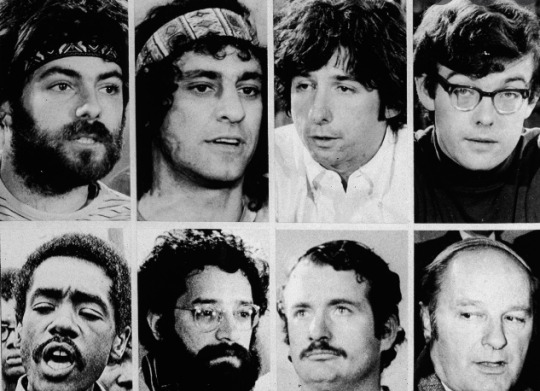

There are so many similarities from 1968 and 2020 when it comes to protesting for civil rights and the disparities between color within the judicial system. Read and research the information and come to your own conclusions.

Also consider how then and now all roads lead to the political government system and what ever happen to judge Julius Hoffman for his racist behavior- Nothing ! not a damn thing, and what was horrible and sad was and still is, he stayed on the bench with his racist view of the law and when judging exemplified the very definition to the word Kangaroo Court.

Court in which the principles of law and justice are disregarded or perverted 2: a court characterized by irresponsible, unauthorized, or irregular status or procedures 3. An unfair, biased, or hasty judicial proceeding that ends in a harsh punishment; an unauthorized trial conducted by individuals who have taken the law into their own hands, such as those put on by vigilantes or prison inmates; a proceeding and its leaders who are considered sham, corrupt, and without regard for the law.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago is most-remembered for what happened on the streets outside of it, “One day in Grant Park somebody took down a flag and the police used that as an excuse to go through the crowd beating people with nightsticks,” recalls John Froines, who helped organize the DNC anti-war demonstrations with Rennie Davis of the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam.

“Rennie Davis and I were hit on the head with night sticks.”Froines, who is now a professor emeritus of the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, wasn’t arrested that day. But a year later, the U.S. government accused him, Davis and six other men of conspiring to incite a riot at the DNC. The others were Bobby Seale, co-founder of the Black Panther Party; David Dellinger, a longtime anti-war activist; Tom Hayden, cofounder of Students for a Democratic Society; Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, founders of the Youth International Party (whose members were called “yippies”); and Lee Weiner, who had volunteered as a marshal for the DNC demonstrations to help with crowd control.

The evidence against the Chicago Eight, as they became known, was always slim. None were convicted of conspiracy, and although five of them were convicted of inciting a riot, an appellate court dismissed the charges because it found that the judge had been biased against them. Fifty years later, here’s why the Chicago Eight trial that opened on September 24, 1969 was such a big deal.

1. The Chicago Eight were the first people tried under the first federal anti-riot law.Anti-riot laws were all at the local or state level until the passage of the 1968 Civil Rights Act, which included a provision making it illegal to cross state lines to incite a riot.

2. Prominent voices challenged the legitimacy of the anti-riot law The New York Review of Books arguing that the anti-riot law set a dangerous precedent. “The effect of this ‘anti-riot’ act is to subvert the first Amendment guarantee of free assembly by equating organized political protest with organized violence,” It read. “Potentially, this law is the foundation for a police state in America.

There was a clear cultural clash between the judge and the defendants. Judge Julius Hoffman,. In one instance, they showed up to court wearing judicial robes to protest Judge Julius Hoffman’s decision to revoke Dellinger’s bail. When the judge demanded they remove their robes, they took them off and stomped on them. Underneath, they were wearing Chicago police uniforms.

Another time, Hoffman unfurled a National Liberation Front (aka “Viet Cong”) flag on the defense table, and engaged in a tug-of-war over it with a court marshal who tried to remove it. Sharman says the media tended to emphasize moments like these because they were so unusual. However, he thinks it’s important to understand these incidents in the context of the judge’s behavior toward the defendants. “Even on the first day, Tom Hayden gave a fist salute to the jury and he was given a contempt of court citation,” he says. “It was like nothing could be done without the judge sort of stamping on them, so that sort of encouraged them to do it, I think.” By the end of the trial, the judge had charged all of the Chicago Eight as well as defense attorneys William Kunstler and Leonard Weinglass with contempt of court.

4. The judge ordered Bobby Seale to be chained and gagged in court. Courtroom drawing of Bobby Seale bound and gagged during the trial, by argues Hoffman and Rubin’s robe incident “was basically a minor disruption,” and that “the main event in terms of disruption was Bobby Seale being chained and gagged. Seale—the sole black defendant—called him a racist, and continued his attempts to represent himself in court. On October 29, about a month after the trial started, the judge became irate and ordered staffers to chain Seale to his chair and gag him so he couldn’t speak anymore.

A week after Judge Hoffman first chained and gagged Seale in court, the judge sentenced Seale to four years in prison for contempt of court. He also declared a mistrial in Seale’s case and removed him from the trial, turning the Chicago Eight into the Chicago Seven. Judge Hoffman intended to try Seale separately for conspiracy in a new trial next year. However, after a jury failed to convict the Chicago Seven of conspiracy, the U.S. attorney in Chicago told Judge Hoffman that “it would be inappropriate to try Seale alone on a conspiracy charge,” and the judge dropped Seale’s charges

6 To make this point, the defense called over 100 witnesses, many of whom had been in Chicago during the protests. At the time, a lot of prominent writers and performers were involved with the anti-war movement, and the witness list reflected this. The court heard testimony from comedian Dick Gregory,

7. The conservative judge’s disdain for the defendants helped overturn the convictions. Portrait of the Chicago Seven and their lawyers as they raise their fists in unison outside the courthouse where they were on trial for conspiracy and inciting a riot during the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Illinois, 1969. Judge Hoffman sentenced the five convicted men to five years in prison and gave each a $5,000 fine .

Two years later, an appellate court threw out all of the convictions and the sentences Judge Hoffman had handed down—including Seale’s four years for contempt—citing the fact that the judge had been obviously biased against the defendants. At one point, Judge Hoffman even prevented former attorney general Ramsey Clark from testifying in front of the jury in favor of the defense, arguing that Clark had nothing useful to say.

Excerpts from History.com

Part 1

Black Paraphernalia Disclaimer - Images from Google

7 notes

·

View notes