#but then to have it a concept deeply rooted in jewish identity and history is uuuuh antisemitic

Text

hey. you. yeah you. if you think every and all zionists are inherently evil and the jewish people have no ties to the levant then the posts about antisemitism are about you.

#antisemitism#jewish#jumblr#i am TIRED of seeing people reblog my posts about antisemitism#with their previous post or following post being 'death to zionists'#or 'all israelis are settler colonialists who deserve to die'#define zionism for me#every definition of all forms of zionism#which is something i cannot do so i am sure you cannot do#so to claim you hate all versions of a concept you do not know is extremist to begin with#but then to have it a concept deeply rooted in jewish identity and history is uuuuh antisemitic#now tell me the history of the land of israel#and the connections between jewish holidays and the land#you can't do that either because then you'll need to admit that jews also belong in the land huh

402 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Pete Peterson and Jack Miller

Published: Jan 22, 2024

The shocking scenes of college students, faculty, and staff defending Hamas’s October 7th massacre of Israeli civilians as a “legitimate act of resistance” have rightly been called antisemitism.

Our father’s antisemitism was the centuries-old hatred of Jews just because they were Jews, different in their beliefs and customs. But this new form of antisemitism is different, and there are reasons why we’re seeing it revealed on our college campuses today. It’s an antisemitism based on an ideology of the oppressed versus the oppressors, which is also being used against people of other races and ethnicities. Because Israel is seen as strong it is viewed as the oppressor, and Hamas, because it is weaker, is seen as the oppressed.

As two Americans (one Jewish, the other Christian) who are deeply concerned about the future of our country, along with our cherished institutions of higher education, this ideological antisemitism has implications for America as a whole. The antisemitic outbursts at our nation’s colleges and universities are the canary in the coal mine, a warning sign of how this radical worldview regards America, and the West more broadly.

In his book Defending Identity, the legendary Soviet dissident, human rights activist, and Israeli politician Natan Sharansky wrote, “Anti-Semitism has had a unique and astounding staying power, metamorphosing from one epoch to another, one period to another, emerging in different forms to influence different places with different cultural lives.” He concluded by noting, “In each case anti-Semitism has been directed against that conception of identity, of how people defined who and what they are.”

How right Sharansky was. Look at America today, torn apart over which identity group is the most oppressed. But the American motto is “E pluribus Unum” – out of many, one. Instead of bringing us together, this ideological view of the oppressed against the oppressors is tearing our nation apart.

A recent Harvard-Harris poll showed that two-thirds of voters between the ages of 18 and 24 agree that “Jews as a class are oppressors and should be treated as oppressors.” This demonstrates the extent to which this extreme worldview has taken hold in our country. These young people have just recently been through our educational system, which has played a key role in shaping how they think.

We see a strong connection between the ideological capture of K-12 and higher education and the decline in teaching our nation’s founding principles and history in a non-ideological way. American civics and history, rightly taught, is a powerful tool for fighting all “isms,” including antisemitism.

As America approaches its 250th anniversary a growing number of organizations, including the Jack Miller Center and the Pepperdine School of Public Policy, are stepping forward to put a greater emphasis on quality, non-ideological civics and history education. We are seeing some successes with rapidly growing programs that give high school social studies teachers more content through lectures and seminars, as well as the recent launch of civics institutes at a number of public universities, from the University of Florida’s Hamilton Center to the University of Texas’s new Civitas Institute, among others.

Civics education rightly understood counters this new form of antisemitism, and all identitarian philosophies, as it promotes an American “unum” through a non-ideological (yet still critical) teaching of the American project.

Sharansky thoughtfully surmised that, at its root, this is a battle over identity – who we are as American citizens and the future of the American experiment. He wrote in the aforementioned book that “a society without a strong identity is also a society imperiled. The free world’s shield against its enemies is its own identity, vigorously asserted and framed by a commitment to a democratic life.”

The anti-Israel, antisemitic demonstrations on college campuses and in the streets of our cities should be a wake-up call for all Americans. This ideological concept of oppressed versus oppressors that underlies these protests, which brokers no disagreement, is being used against America’s very principles and ideals. Only through a civics education that encourages debate, even as it celebrates the country grounded in the freedom to do so, can we win this battle.

#Pete Peterson#Jack Miller#antisemitism#civics#pro hamas#pro palestine#pro terrorism#islamic terrorism#jihad#islamic jihad#ideological capture#ideological corruption#corruption of education#religion is a mental illness

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

**Title: Zionism and Judaism: Understanding the Differences and Connections**

**Introduction**

Zionism and Judaism are two terms often intertwined, yet they represent distinct concepts in the realms of ideology, culture, and politics. While Judaism is a millennia-old religious tradition, Zionism is a relatively modern political movement. This essay explores the differences between Zionism and Judaism, shedding light on their unique aspects and the connections that bind them.

**Judaism: A Religious Heritage**

Judaism is one of the world's oldest monotheistic religions, with roots dating back thousands of years. It encompasses a rich tapestry of beliefs, rituals, and ethical teachings, emphasizing the worship of one God and the importance of moral conduct. Jewish identity is deeply rooted in religious customs, traditions, and scriptures, including the Torah, Talmud, and other sacred texts.

**Zionism: A Political Movement**

Zionism, on the other hand, emerged in the late 19th century as a response to rising anti-Semitism and Jewish persecution in Europe. The Zionist movement, led by figures like Theodor Herzl, advocated for the establishment of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, which was then under Ottoman rule. Zionism aimed to address the Jewish diaspora by creating a national homeland where Jews could live independently and without fear of persecution.

**Key Differences**

1. **Nature:**

- **Judaism** is a religious faith and cultural heritage followed by Jewish people worldwide.

- **Zionism** is a political ideology advocating for the establishment and support of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, which eventually became the modern state of Israel.

2. **Scope:**

- **Judaism** encompasses a wide range of religious practices, beliefs, and traditions, emphasizing spiritual connection with God and adherence to religious laws.

- **Zionism** specifically focuses on the political goal of establishing and maintaining a Jewish homeland, emphasizing national identity and self-determination.

3. **Beliefs:**

- **Judaism** includes diverse religious beliefs and practices, with various sects such as Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, and Reconstructionist Judaism.

- **Zionism** does not prescribe religious beliefs but rather advocates for a political solution to address the Jewish diaspora.

**Connections Between Zionism and Judaism**

While distinct, Zionism and Judaism are interconnected in several ways:

1. **Historical Context:**

- The foundation of the state of Israel in 1948 fulfilled the aspirations of many Zionists, providing a homeland for Jewish people, thereby intertwining the concept of Zionism with Jewish identity.

2. **Cultural and National Identity:**

- For many Jewish people, especially those in Israel, Zionism has become an integral part of their cultural and national identity, reinforcing a sense of belonging and historical continuity.

3. **Religious Significance:**

- Some religious interpretations within Judaism view the establishment of Israel as a fulfillment of biblical prophecies, adding a religious dimension to the Zionist endeavor for certain believers.

**Conclusion**

In summary, while Judaism is a multifaceted religious tradition with deep historical roots, Zionism is a modern political movement that seeks to address the Jewish diaspora through the establishment of a homeland. While they have different objectives and scopes, the historical and cultural ties between Zionism and Judaism have created a complex and multifaceted relationship, shaping the course of history and the lives of millions of people around the world.

0 notes

Text

Jewish Traditions

Jewish Traditions refers to the set of beliefs, customs, and practices that have been passed down through generations of Jewish people. These traditions are deeply rooted in the history and culture of the Jewish people, and play an important role in shaping their identity and way of life.

Some of the key elements of Jewish tradition include:

Monotheism: Jews believe in one God who created the universe and continues to be actively involved in the world.

Torah: The Torah is the central text of Judaism, consisting of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. It contains the core teachings and commandments of Judaism.

Mitzvot: Mitzvot are the commandments or laws that are derived from the Torah and other Jewish texts. They cover a wide range of areas, including prayer, charity, dietary restrictions, and ethical behavior.

Shabbat: Shabbat is the weekly day of rest and spiritual rejuvenation that begins on Friday evening and ends on Saturday evening. It is a time for families and communities to come together and celebrate their faith.

Holidays: Jewish tradition includes a calendar of holidays and festivals that commemorate important events in Jewish history, such as Passover, Hanukkah, and Yom Kippur.

Synagogue: The synagogue is the central gathering place for Jewish worship and community life. It is where Jews come together to pray, study, and celebrate.

Tzedakah: Tzedakah is the Jewish concept of charitable giving, and is seen as an important part of Jewish tradition. It is considered a mitzvah, or a commandment, to give to those in need.

Overall, Jewish tradition is a rich and complex system of beliefs and practices that has evolved over thousands of years. It continues to be a source of inspiration and guidance for millions of Jews around the world.

0 notes

Note

as a nonbinary lesbian, i was curious how you navigate your faith whilst being queer - if that's something that's even a thing for you.

(thank you for the additional message about this!! i do identify as a nonbinary lesbian but the lesbian aspect is still something im learning about for myself x)

it's a huge thing! my queerness and my faith are completely interrelated and i dont think one would exist without the other- they are mutually enhanced by each other, but admittedly its very difficult in spaces where frequently the community of faith rejects or undermines my queerness, and honestly? the queer community frequently also rejects and undermines my faith. its weird! but i also know that the profundity of my identity mirrors the profundity of God's own- as much as people struggle to understand the depths of who God is and how he loves, i feel like queer people experience the same thing- the struggle of the hegemony to understand how they love and who they are. we refer to God as a he and we call jesus his son, but lesser known is the fact that shekinah, the spirit which is said to have covered mary at the immaculate conception, the force with allowed her body to carry a god, is written of in the original hebrew using feminine pronouns. which is such a small way of acknowledging how synonymous queer identity- particularly nonbinary or trans identity- is with the idea of God's identity.

in terms of navigating homophobia in the church and in faith, i think a lot of it is born out of ignorance and a long history of misinterpretation of the bible. many rabbis teach that the sins of sodom were not homosexuality, but economic injustice: the sexual element to the sin told in genesis was that the men of sodom wanted to have sex with angels, a grave sin rooted in ancient jewish mysticism. it was never about men having sex with men: it was about men having sex with angels, which is incidentally also the impetus in the jewish flood narrative for the destruction of humanity. and jonathan and david- i love, so deeply, how 1 samuel talks about their relationship, that jonathan loved david as his own soul, his own nephesh, a word that has no direct translation in english but in hebrew encompasses means life, self, person, desire, passion, appetite, emotion. psyche, sentience, breath. it is that which passed from God into man and made him alive. its a deep profundity of love, and it is between two people of the same gender, and to say that homosexual love exists in scripture in some capacity does not at all seem at odds with a god who is written in in a multitude of gender expressions. so that's the biblical foundation for navigating my faith and my identity: there is nothing in scripture at odds with me. and i'm sure there will be a christian who comes trotting into my inbox citing leviticus 18. leviticus 18 should be of no concern to christians. it is jewish law. you are not jewish: you are christian.

in terms of the church, i will not lie! i went for a job interview to be a children's minister and was passed over for the job because the church did not support inclusion. i am often scared of being blackballed because of my identity. i am privileged in that i pass as cis: trans is not a term i would ever apply to myself. and i've chosen to be single so i can focus on school, so my sexuality doesn't come up often. but i'm out to my school chaplain, and she's been incredibly supportive and encouraging. i am also fortunate that i live in a very liberal city and attend an anglican school, so i have never encountered direct homophobia or transphobia in terms of my schooling. in fact ive felt supported and loved by my peers- even in places that i think people don't expect to see it, like classes where there's three women, me, and twenty priests-in-training. and i am lucky and, i think, unusually lucky. i spent time as a child in spaces that were intensely homophobic- people who, when i expressed my joy at the legalization of gay marriage in the us, were horrified and said i would go to hell for my support. and as a young lesbian, as someone who knew i was different from my peers but couldn't quite figure out what, it was an awful experience that set my development back exponentially. i'm not going to say that the church as a monolith is a safe place for queer people. it's not. but God is profound love: God loves us. and there are many, growing places- as there have always been- in the church where queerness is not at odds with the practice of faith. so i carry my identity close to me, i don't advertise it, but i know that where humanity does not have the capacity to love me for who i am, God's profound love is capable of far more than i could ever imagine. and that comforts me a lot.

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello, I was reading your meta about how Darth Vader is a lich (it’s excellent btw) and I was wondering if you could expand more on the classical meaning and uses of the terms “phylactery” and “lich.” I know that phylactery has long refered to the boxes attached to tefilum used in jewish prayer (I’m jewish) and I know the root of the word is derived from Ancient Greek but prior to reading your meta I had heard that the modern use of the “phylactery”/“lich” mythology came from D&D in the 70s. Is there an earlier record of this mythology? Thank you.

The paired terminology lich and phylactery absolutely did enter the modern popular imagination through DnD and other fantasy literature in the middle of the 20th century. I think it’s modern mythology, using extant archetypes to create something new.

The pairing of an undead magician and an object containing their soul/anchor to life are both evocative of earlier mythological elements but not identical. It draws on the ancient idea of magic being a kind of binding and the very ancient concept of the soul. BUT, the words were not linked before the 20th century, and come from distinct heritages.

In DnD, a lich is corporeal, gaunt and skeletal, with points of light burning in place of decomposed eyes. Their soul (life-force? identity?) is stored in an object that binds the soul to the mortal world and prevents it from traveling to the Outer Planes after death. The phylactery itself is usually an amulet in the shape of a small box, but it can take the form of any object with an interior space in which arcane sigils of naming, binding, immortality, and dark magic are scribed in silver. The magician’s soul persists inside the box.

Since about the Middle Ages, the word phylactery’s meaning was specifically fixed to tefilum (small boxes containing scrolls of parchment inscribed with verses of the Torah), but before that, back in antiquity, it meant something more general like amulet or charm—small objects worn for magical/supernatural protective power.

The word comes from the verb φῠλᾰ́σσω (phulássō, “to protect”), and meant a fortified garrison, and then over time the meaning was adopted and changed into a protective amulet. The Jewish usage is a specific continuation of a long-standing tradition, one that Christians (I think) moved away from as ‘superstition’ and a legacy of paganism.

In antiquity, phylacteries were created using binding spells, engraving, and inscription (spells/magic words, invocations of supernatural beings like minor gods, naming, etc). They were usually tied around the body, either strings/bands, or strips of metal/papyrus was inscribed and then rolled up or folded and carried in a pouch or tubular container. The container itself was not the φυλακτήριον, the inscribed/magical contents provided the power. They were thus not conceptually hollow and did not provide a vessel for a soul or anything like that.

There was no specific association between φυλακτήριον and preservation from death. They affected things like social relationships, brought prosperity, warded off the evil eye, that sort of thing. There was a great deal of paranoia in antiquity about binding spells/curses like defixiones cast by other people, and amulets/phylacteries were more about that and general protection from them and other misfortune than preservation of the life force.

I know that by the Middle Ages, Christians had phylacteries that contained relics (e.g. the finger of Marie of Oignies in the 13th century was placed in a phylactery). So, what was contained inside the phylactery and powered the protection was no longer something inscribed, but a magical token related to death. Christians, though, did not have any desire to keep their souls alive and away from God (based on my understanding of Christian doctrine, the idea of trying to bind the soul to keep it away from God is incredibly deeply sinful?). Those phylacteries then were also good luck charms within the context of having a good, safe, and happy life.

Why then did 20th century fantasy writers decide to use the word phylactery to describe a magic vessel protecting the soul? I hope the lingering Christian fingers-in-a-box and general magical-safekeeping-amulet meanings of phylactery were in the minds when they paired the term with lich, but it may very well have been a direct appropriation of the Jewish (common, modern, recognized) meaning of the word, I honestly do not know.

In terms of the vocabulary, lich (from Old English lic, corpse), is borrowing resonance from something called a ‘lich gate’ which stood at the lowest end of the cemetery where the coffin and funerary procession usually entered. Fantasy authors were probably trying to draw both on the corporeal/physical (i.e. not a ghost) undead figure, and the idea of transition and liminality that the lich exists inside, both dead and alive. Liches refuse the final transition, essentially, to go through the gate.

I think it’s a mash up of ancient ideas��by pairing these words, the writers in the 20th century created a modern sort of undead creature. There is no history of lich/phylactery before the 20th century, but both words are very evocative and conceptually related to magic (phylactery) and the narrative undead villains in stories (lich) through the ages, which is perfect for fantasy stories and games that tell stories in those worlds. I think the use of Old English too evokes Tolkien’s contributions to the fantasy genre.

By making it specifically a magician (intellectual) who chooses this transformation for themselves, as opposed to a creature animated by something else’s power, it is reminiscent of the concept hubris, especially nerds who seek to know too much and have too much power through technology/human knowledge. Naming it after something Greek also seems to evoke that it is esoteric and something learned from study, while lich is very idk Anglo-Saxon and old in a primeval way.

The whole concept seems very modern to me also to externalize and concretize a soul into something that can be stored like an object (is it from external memory—computers?). It’s a very secular and materialist appropriation of a magic/sacred concept, aka the bread and butter of fantasy lit.

Corpses reanimated by supernatural forces are present in almost every belief system in the world, as well as the idea of souls (ghosts) that persist without bodies. What is interesting is the mechanics of how these creatures are reanimated, how they stay reanimated, and how they are destroyed. That is a whole other subject tbh, a whole book could be written about this.

Tl;dr—the combo of lich/phylactery is modern, but evocative of older things both through name and through mechanics.

#this is a ramble sorry#the role of immortality#in mythology#and the various undead revenanat#draugr etc#is huge#but liches are new#classics#essie007#i studied ancient magic#i am not an expert by any means#phylacteries are very old

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

2020 is shaping up to be the Worst Year Ever (the title of a podcast about primarily US politics you should follow for November) for political reasons and I’ve heard a lot of folks say “being ‘apolitical’ is political” or “not choosing is a choice” and they’re right, but I rarely hear exactly WHY they’re right so if you’ll pardon me for a moment:

For LGBTQ+ people, the consistent rolling back of our rights by Republicans and their conservative justices (many of whom including a SCOTUS justice Mitch McConnell deliberately delayed letting Obama fill) isn’t “just political,” it’s our lives, our ability to function in our communities on every level from using the appropriate bathroom to serving in the military (which if you’re LGBTQ+ I strongly advise against for reasons I’ll get to).

For people of color, an increasingly militarized police force, thoroughly infiltrated by white nationalists and abusers (domestic abuse is between 200-400% more prevalent among families of police), is a threat to the safety and security owed to all citizens by their government and, if you’re a bleeding-heart liberal like me, to all residents regardless of “lawfulness.” But there’s also that one of his first pardons was Joe Arpaio, who reinstituted chain gangs (prison industrial slavery is the latest in the US’s long lineage of enslaving and literally disenfranchising Americans of color) and targeted Mexican Americans.

For women, when DJT says regularly at his rallies that “he won the women” but the majority of only white women voted for him, it should be enough for all women to understand that as a self-admitted nationalist, his conception of women is narrow and excludes many of our sisters of color.

For our Jewish and Muslim siblings, his close ties to white evangelicals should be especially troubling since their churches are deeply rooted in white nationalism and antisemitism. Within a week of calling himself a nationalist the worst antisemitic attack in US history was committed. He proposed, regardless of its narrower ultimate product, a ban of “all Muslims” from entering the US. Having a Jewish son-in-law and supporting the government of Israel are screens to hide the ugly nationalism of his supporters.

But even ignoring all that, which you shouldn’t, isn’t it a little convenient that the parts of our identity under constant attack are all “political” if we speak up about them? Conservatives get to be aloof and call us hyper-partisan because they’ve succeeded in pushing the narrative that we’re the only ones being political and that centrism and apathy are somehow intellectual instead of uninformed. It’s the fatal flaw, a myopia really, in the Democratic Party: they’ve bought into the narrative that conservatism in any other country is “common sense” in the US, while any degree of leftism is radical, so they stick closer to the center and, by extension, closer to conservatism. The data rather clearly shows that, as Republicans become more and more conservative, sprinting toward the fascism at their end of the spectrum, Democrats either center themselves or don’t dare go left toward the basic welfare of their people to avoid being called “socialist,” though they’re far short of that extreme, communism. It’s why the ahistorical “fascism is of the left” fantasy is popular among conservatives, because to them they can’t be fascists because they can’t be extremists. It’s why Republicans get to elect DJT but the Democratic establishment is getting all worked up about “electability.” It’s why Republicans get to send two TV personalities to the White House but Democrats are just “Hollywood elites.” They get to be extreme, but we have to settle for moderates. The narrative that the right is “traditional” and “rational” and “common sense” and “facts over feelings” has made it impossible for them to look political even as they buttress a fascist regime, but we’re whiny socialists for resisting, for existing in spheres they’ve labeled extreme. As we look toward 2020, we need to call out bullshit, come out of our various closets, and resist. If DJT gets elected again because we choose a moderate or one of his worshipers kills his opponent because they think the US is at stake, we need to be prepared to not hide anymore, or, at the very least, to PLEASE learn something.

286 notes

·

View notes

Link

I guess in light of this, I should explain just how horrific Critical Theory is with regard to Jews and thus anti-Semitism. It's almost impossible to convey the full, crazy depth of this, so I'll have to leave out huge parts, too, like Islamophobia.

To only briefly touch upon the "Islamophobia" aspect, both Critical Race Theory and Postcolonial Theory are deeply invested in the support for Palestine, by which is more specifically meant the utter destruction of Israel and anti-Zionism.

Even the Queer Theorists are in on this.That very practicable side of Theory sees that the existence of Israel at all is a colonial conquest of Palestine, thus a last lingering full-blown move of Western colonialism into "brown" and Eastern (read: Islamic) territory, thus intolerable. The Jew-hate is insane on this.

Theory across the board protects Islamist anti-Seminism (and other horrors, like Muslim grooming gangs that target white women for sex abuses), because it would be "racist" and "colonialist" to denounce these horrors because that requires a "white, Western" perspective.

That's the part I'm going to ignore, though. I want to talk mostly about Critical Race Theory, whiteness, and anti-Semitism. I think you'll be shocked at how deep the rot goes and how vile and dangerous the ideology is. Another Holocaust could result, not being hyperbolic.

Light-skinned (and often other) Jews are Theorized as having been granted the status of "whiteness," with this being extremely obvious with Jews whose skin is actually quite pale. This means that Jews, in CRT, have an intolerable privilege they need to check.

Here's the problem, though. Jews have quite the incredible history of super legitimate oppression, including imperial destruction, diaspora, enslavement, and a literal genocide in the Holocaust. They're really huge victims historically, including of "the West."

As with the related concept of "brown privilege," which assigns to "brown" people a very uncomfortable position of being Theoretically "anti-Black" and yet "not white," Jews are Theoretically assigned whiteness with a HUGE, defensible claim on legitimate systemic oppression.

This combination is intolerable to CRT. CRT would demand that Jews atone of their whiteness by recognizing it and critiquing it and submitting to CRT, which identifies them indelibly as white (including by success), yet their legitimate claim to systemic oppression prevents it.

Jewish people therefore fall into a very dangerous spot within Theory: they have a legitimate reason not to "do the work" while "enjoying the benefits" of whiteness, in many respects more than most other people. This is an intolerable contradiction that will demand resolution.

Theory cannot find a resolution to this situation, especially so long as Israel exists and is "oppressing Palestine" by its very existence, which is another problem that is nearly impossible to solve. Lacking resolutions to major Theoretical contradictions rarely remains stable.

The Critical Whiteness aspect of CRT holds that Jews have been granted Whiteness by whites but bc they retain their historical victimhood statuses, they enjoy an even further privilege of getting a kind of "false" victimhood status as well. This is obviously the stuff of horrors.

This set of contradictions has also led some (fringe) elements within Social Justice to begin to deny the Holocaust entirely, which cannot be seen as a welcome development, especially in a broader context where the far right has been doing the same and muddying those waters.

More commonly, it has led Theorists to say things (as went quite viral earlier this year) that Anne Frank is only relevant because of her Whiteness and wouldn't be an interesting story (or part of the Western canon) if she hadn't been white. This is unhealthy stuff.

So, add in the stuff where they elevate Muslims to a highly protected status and their protectionism for Palestine, they also tend to see Zionism as a colonialist movement (at best) that has been literally infected with (literal) Nazi ideology (at worst), and it's truly scary.

The anti-Semitism in Critical Race Theory isn't an accident. It's what happens when terrible identity-based Theory rooted in victimhood can't resolve real-world contradictions, and it currently bears every unmistakable sign of being a real threat to Jews everywhere.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books You May Want to Read

This is my first post to tumblr and I thought I’d cover a topic I’ve been asked about quite a bit over the last few months: What are some books you’d recommend reading related to Black life in America, racism, inequality, social justice, etc.?

In the wake of social uprisings in response to George Floyd’s murder (and persisting systemic racism and inequity), I’ve received this question primarily time and again from coworkers and friends.

Here is a list of reads that I’ve felt help provide understanding on the history of racism, it’s bridge to modern social/economic inequities, the simultaneous devaluing of Black life vs the fetishism of Black entertainment, the Black experience in America, and how embedded some of these concepts are into the fabric of society. There are of course a plethora of written works by talented Black (and non-black) authors that collectively works to encapsulate Black life in America. And it should be known that Black life, thought and existence is varied, nuanced and diverse - just like the life of non-black people. This short list is a selection that I feel best exposes elements of society that I’ve experienced in my own life.

1) Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, (Ibram X. KendI):

I read this book about three years ago and have yet to come across a more informative read that investigates the origins of our modern society’s current racial caste. Told from the perspective of four prominent figures in America history, this extremely well-researched and written book draws a bright line through six centuries of this country’s (or more accurately - this continent’s) past and perfectly connects it to modern-day socioeconomic outcomes.

2) Between the World and Me, (Ta-Nehisi Coates):

Told in way that reminds one of James Baldwin’s - The Fire Next Time, this letter from the author to his son is ripe with passion and reflection of his own upbringing and journey to adulthood as a Black man in America. Sprinkled with really honest personal anecdotes, this is a great read that will challenge you to reconcile how Black life, specifically Black bodies have been viewed, owned and valued in America.

3) Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?: And Other Conversations about Race, (Beverly Daniel Tatum):

Written by a psychologist/researcher, this read is particular poignant in its focus on racial identity for many races, with a particular focus on the development of that identity for Black and white people. This book takes more of a scientific approach, through empirical studies, focus groups, and conversations with individuals of different races. If you’ve ever looked around at your friend group and wondered “Why does it seem that I only tend to hang out with people who look just like me?”; If you’ve had period of your life were you’ve had a closer circle of more diverse individuals, and no longer do; If you have found that racial identity has always been complex for you...this would be a good one to pick up.

4) Forty Million Dollar Slaves, (William C. Rhoden):

One of the most understated sports books of all time - this is not only reserved for sports fans. I personally struggle with modern society’s affinity for seeing and championing Black athletes, and entertainers, propensity to perform and create at an elite level, while simultaneously dismissing their humanity at the same time. As such, I’ve deemed myself a ‘reluctant sports fan’. Learning more about the history of this dynamic was for me very compelling. This book delves deep into the history of the American Black athlete, examining the impact Black athletes have had on American society, and their own communities as well. Similar to Ibram Kendi - it stretches into modern times and brings to light gripping issues such as the concept of a Black ‘sellout’, white approval, white ownership and the remanence of racism transferred therein.

5) The Cooking Gene (Michael W. Twitty):

This book is aptly:

- one part story of one man’s search for his ancestral roots,

- one part cookbook, and

- one part history lesson of life in the American south for Black people throughout the 400 year history of the Black struggle in America.

“Twitty,” a Black Jewish chef who showcases ancestral cooking through reenactments on Southern plantations, recounts his deeply personal, painstaking and detailed journey to finding as much of his ancestors (Black, white, and everything in between) as he’s able to. With food as a central character (specifically its ingredients) you are taken on a reverse Triangular Trade route of sorts, from the rice fields of Louisiana, the plantations of Virginia and the Carolinas back across the ocean to Africa and even to England as Twitty searches for the answer many people still grapple with: Who am I?

6) The Warmth of Other Sons (Isabel Wilkerson):

Told through the eyes of three black Americans - this is the story of the ‘Great Migration’ - the movement of 6 million African Americans out of the rural Southern United States to the urban Northeast, Midwest, and West that occurred between 1916 and 1970.

Wilkerson paints a vivid picture of the journey, successes and hardships black Americans faced as the moved from rural communities in the Jim Crow south, to cities and suburbs of coasts and midwest. As the stories weave through multiple generations, this book answers a lot of questions about structural racism and institutionalized obstacles facing black people such as redlining, white flight, job discrimination, over-policing, police brutality/violence (and more) and how these impediments resulted in decades of setbacks.

I come from a West-Indian family, a part of black America that melds an ‘immigrant story’ with the black experience in America. This one spoke to me.

7) Barracoon: The Story of the Last "Black Cargo" (Zora Neale Hurston): If you need a reminder that the enslavement of black people in America was not that long ago, look no further than this book. Barracoon, based upon the first-person account (interviews Hurston herself conducted) of a survivor of the last slave ship to transport enslaved black Africans to the United States. A full 50 years after the “trafficking” (but of course, not the enslavement) of African peoples was outlawed by the United States, a ship named the Clotilda pulled into Mobile Bay, carrying “Black Cargo” - over 100 enslaved Africans, one of which was “Cudjo”, a former-slave, and Middle-Passage survivor. From their 1930 interviews, Cudjo opens up to Hurston about everything - he has a rich memory about live in Africa, his kidnapping and trafficking, enslavement in America ,and life in the era of ‘Reconstruction’. A recommended read that can promise above all else - a perspective like no other.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I know I haven’t really updated on here. Fatherhood can be really tiring and time consuming as it is a blessing and will change who you are for the better, at least for me. I’ve been away from a lot of the subjects I used to normally post about until recently, that’s because I picked up the energy and interest for science journalism again.

To say I went off to have a long waited talk with nature is to minimize greatly the kind of transformations I’ve undergone. The mysteries she’s shown me far greater than any cosmic unknown that I could have ever imagined of. I know a lot of the folks who used to follow this blog might be surprised to know that within that journey I’ve seen, experienced and have been in communion with some really influential spirits of old. Nature’s hidden variables. Whatever you want to call it. Something occurred when I decided to take more seriously the religions and spirituality of my ancestors. Something that only reinvigorated my love for science and the unknown, physics, art, and expression of these things for beneficial communal use.

I’m from Quisqueya, the first testing grounds for colonialism and subsequently the evolution of neo-colonialism. Not too long after and we become one of the first pit stop for the trans-Atlantic slave trading markets to proliferate and spin the rest of the world off into the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy hell branch of a reality we know of today. Our little island has undergone so many transformations and inclusion of peoples, cultures, so many I only recently found out of like how Haitians took in Jewish refugees during the time of Hitler’s nazism.

Because I still deal with mental health issues and depression being one I’ve had since childhood, I sometimes don’t have near enough energy to convey how have things been going since my last big update here. My spiritual and religious journey, finding comfort in myself and closure in ways I no longer adhere to. That said I found it beyond amazing how earlier today on October the 14th ‘Indigenous Peoples Day‘ I was drumming away to Tainx music without realizing what day today was without looking at my social media feeds yet. Here I was normally thinking I’m so tired, down and out of trying to keep these cultures alive and I was already doing so instinctively in the truest way I know how.

Like I mentioned, I decided to take more seriously my Afro-Indigenous roots and what it meant to be a Black Dominican Haitian Taino American. It took me on the wildest ride with the unlikeliest subject ranging from seeing quantum entanglement examples right before my eyes, seeing living breathing afrofuturism through my Vodun, Catholic, Christian roots and the functionality of Vodun to incorporate so many ancient parts of being Black into what intuitively led me down a road of self and outward knowledge on the cosmos around me.

To then blend these epigenetically installed formulas of spirituality embededd in me by history and nature, incorporate them into my expression of art and self which is one has been like achieving a life long dream I didn’t even know I had. I did so much intuitive shit that was so clearly linked to my identity as an Afro-Indigenx American immigrant along the way that I had erected an altar without knowing it was an altar. I would section and compartmentalize this prototype altar so beautifully and had no clue I was paying respects to my ancestors and spirits of the world until more recently a few months back. When I realized this, it was like a Cambrian explosion occurred in me.

I don’t want to get into the details of the abilities it brought out that I already had in me due to prying eyes (ahem surveillance capitalist patriarchy is still outchea at large) but to simply meditate and think on my folks has given me such a renewed and strengthened sense of intuition and appreciation for the past and future that I never knew existed. Sometimes I’ll legit write and prophesize shit out the ass like it’s a normal day it’s wild, shit I never believed in but the science seems to check out with quantum physics and what not. That’d be an explanation for another time.

The altar has now evolved to a place I can really go to and express but at the same time it’s something I’ve learned to keep within my own self so that it’s not the altar that’s important, rather the changes I’ve gone through to get to such a place. I write, dream, visualize, laugh, act, improvise, predict based on science, meditate, heal, rehabilitate myself there. But conversely the world speaks to me there, the spirits of old, new, those to be. I know it sounds type wild but it’s gotten normal for me to experience something my old science nerd ass self woulda made fun of me for.

But when you get into a connection with ya ancestors like I have and reach the conclusions and deductions I have on the systems that control the planet it gets clearer to see that the Indigenous were right all along on colonialism, it’s gotto go. There’s no place for it in the future if we’re to survive a planet seemingly becoming another Venus. I’d like to think we not gone be fighting each other while some catastrophe bop our asses one time like they did the dinos. That’s one of the main messages they keep tellin me and it’s hard to refute.

I’ll try and continue this update on another day as there’s so much in between and concepts and ideas I wanna share about how to move forward on activism and using art to get our ideas about those movements across. The above images span from months, just small droplets of the cool ass journey I been on just trying to maintain some normalcy while playing my part in not helping oppressors of any kind continue proliferating their systems of domination and subjugation.

So this first image is from the week not too long ago when I had 2 honey bees flying in and checking out the altar. Then I left an old jar of honey that still had some and they’d return and eat some for like a good week or so. At one point, this matrix-like moment happens when one of them goes into the jar and makes this cool sound I never heard before. The bee had gone in there before many times and never made that specific sound, it was like a lower frequency conch shell or something. When I checked the time it was like 1:23pm or 1:11pm one of those. I was like..... get Neo!! shit was so cool.

This next image is really a culmination of my search to learn more about my Afro-Indigenousness which led me to learn more about my Haitianness and the spirituality and religion. From painting Papa Legba paintings before I even knew him, to giving respects to all types of 21 division spirits and Vodun loa before ever even knowing of them. It was as if each part of these religions was trying to show me how much of them was in me in how intuitively I’d gravitate towards these religions despite being still very devoted to science and scientific literacy worldwide. Idk it’s just been a really cool blending of a lot of things I never thought could come together. I found this moth around the time I was reading and thinking deeply on the creator entity in Vodun and some African religions, Gran Maitrex. I’ve always had an interest in creator stories and beings so when this Golden Moth popped up in the altar (right on the mat I have laid in front of it, facing it, as if it came there to spend its last moments) I was like a little kid. To me it reminds me of those mysteries we’ve yet to discover that can help us in our path to heal ourselves and others if we chose to.

The following two are from my walking meditating sessions by the river. They have slightly deeper stories to em about relaxation, overcoming obstacles, predictions I made that day about the sky that I wont get into on here cause it’s exhausting lol. The next image with the wooden branch I brought in from a forest walk is of one of the bees I spoke of flying around the Afro-Indigenx/ Ancient Egypt/ West Africa section of the altar. It did this several times enough for me to note that it liked that particular area. Following non repeating image is of the portrait I did a while back for the Heath Gallery in Harlem on Rein-visioning Brown and Black Bodies in Scifi: Story of 4 Tainx sisters calling for their descendants to help them from the demonic wrath of colonialism.

This picture I took when I finally got to take my ass out to jog after a whole day of being a dad. I found a neat tree to try and climb at night and found this beautiful bright green grasshopper right by the branch I picked. Grasshoppers always remind me of giant leaps I could be taking forward. The following image I took during another forest walk when I looked up and saw this cool cross shape juxstapositioned among the trees.

Last image I took during the Medieval festival they hold at Fort Tryon every year. It’s where I sold my awesome Medieval chicken paintings (which have now taken place at altar where I give em much love) last year dressed as Obi Wan Kenobi. This year I decided to just enjoy it with bae and did so dressed as Jedi Jesus posing as a Dominican Fryer. More pics on that to come. Just wanted to update yall on the spiritual in case anyone could use these words to benefit em. Yall take care. - Ken

21 notes

·

View notes

Link

By Barry Grey

26 September 2019

On Monday night, the New York Metropolitan Opera opened its 2019-2020 season with a new production of George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess. This production has a particular distinction in that it is the first ever based on a critically researched and authoritative performance edition of Gershwin’s score, the product of 20 years of work led by musicologist Wayne Shirley, who is currently at the University of Michigan’s Gershwin Initiative.

There is no doubt that the poignant love story of the crippled beggar Porgy and the beautiful but abused and addicted Bess, and the suffering and struggle of the African American working class community of Charleston’s Catfish Row, is among the world’s most beloved operas and Gershwin’s masterpiece.

Yet the fact that the current production is the first in 29 years to be staged by the country’s most prestigious opera house is indicative of the trials and tribulations that have confronted the work since it premiered on Broadway in October 1935. These have come not from the broad public, which has embraced the opera (and many of its numbers) since its inception, thrilled by its glorious and complex music and moved by its deeply democratic ethos, but from within certain more privileged constituencies—the American classical music establishment, academia, sections of the black professional upper-middle class, including certain African American artists, composers, writers and actors.

Gershwin, the prolific composer—along with his lyricist brother Ira—of hit Broadway musicals and dozens of memorable songs that have become part of the Great American Songbook, rejected the artificial separation of popular music from “serious” or “classical” music. He wrote concert classics that incorporated elements of jazz such as Rhapsody in Blue, the Concerto in F and An American in Paris, which have become part of the symphonic repertoire the world over. He called his Porgy a “folk opera” and deliberately had it debut on Broadway in order to appeal to a broader audience. But what he wrote was a musically dense and dramatically powerful opera in the full sense of the word.

One example of the dismissal of Porgy by much of the American music establishment was a savage review of a production at the New York City Opera written in March of 1965 by the then-music critic of the New York Times Harold C. Schonberg. He wrote:

“Porgy and Bess”—Gershwin, you know—seems to have taken root as an American classic, and everybody accepts it as a kind of masterpiece. It turned up last night as given by the New York City Opera Company. All I can say is that it is a wonder that anybody can take it seriously.

It is not a good opera, it is not a good anything, though it has a half-dozen or so pretty tunes in it: and in light of recent developments it is embarrassing. “Porgy and Bess” contains as many stereotypes in its way as “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

In more recent decades, with the domination of racial and identity politics on the campuses and within what passes for the American intelligentsia, its promotion by the Democratic Party and elevation as an ideological bulwark of bourgeois rule, the opera has been repeatedly accused of denigrating and exploiting black people. It is, according to the terminology of African American Studies departments and a well-funded industry that—with the aid of pseudo-left organizations—churns out racialist propaganda, a prime example of “cultural appropriation.”

We will deal with the retrograde concept of “cultural appropriation” further on. First let us examine how this racialist approach to Porgy and Bess is reflected in the media reception to the new Met production.

The table was set, so to speak, by the New York Times, which led its Sunday arts section with a full-page photo of the two leads, Eric Owens and Angel Blue, and the headline “The Complex History and Uneasy Present of ‘Porgy and Bess.’”

Taking pains to raise the standard racialist arguments against the opera and its composer, while simultaneously acknowledging the greatness of the work, the author, Michael Cooper, wrote:

More urgently, is “Porgy” a sensitive portrayal of the lives and struggles of a segregated African-American community in Charleston, SC? (Maya Angelou, who as a young dancer performed in a touring production that brought it to the Teatro alla Scala in Milan in 1955, later praised it as “great art” and “a human truth.”)

Or does it perpetuate degrading stereotypes about black people, told in wince-inducing dialect? (Harry Belafonte turned down an offer to star in the film version because he found it “racially demeaning.”)

Is it a triumph of melting-pot American art, teaming up George and Ira Gershwin (the sons of Russian Jewish immigrants) with DuBose Heyward (the scion of a prominent white South Carolina family) and his Ohio-born wife, Dorothy, to tell a uniquely African-American story? Or is it cultural appropriation?...

Or is the answer to all these questions yes?

The first wave of reviews published Tuesday (the WSWS will publish its own review of the Met production at a later date) have generally been highly favorable. All of the reviewers, however, feel obliged to qualify their enthusiasm for the performance by cataloging the opera’s supposed “baggage,” viewed from the standpoint of race. It seems they allow themselves to be moved by the piece only reluctantly, and sense its humanity and truth despite themselves.

George Grella, for example, writes in New York Classical Review:

Since its debut, Porgy and Bess has been consistently hectored by two questions: is it an opera and is it some combination of condescension and racial exploitation (lately termed cultural appropriation)?

The debut of a new production of Porgy and Bess, which opened the season at the Metropolitan Opera Monday night, could leave no objective listener with any doubt as to the answer to the first question. And based on the excited responses from the audience during the performance, and the rapturous applause and shouts at the end—from the kind of patron mix one sees in everyday life in New York City but rarely in a classical music venue—the work has gone quite a ways toward settling the latter in a heartening and beneficent way.

There are charges of stereotyping and caricature of the inhabitants of Catfish Row, but the real problem of the opera, the irredeemable original sin of Porgy and Bess that every reviewer is duty-bound to raise, is the fact that its creators were white. (Even worse, three of the four—George and Ira Gershwin and Dubose Heyward—were men.)

Thus, the Washington Post ’s Anne Midgette writes: “Like so many operas, ‘Porgy’ is dated: written by white men and rife with stereotypes of its time.”

Anthony Tommasini of the New York Times writes: “But ever since its premiere in 1935, the work has divided opinion, and the debate lingers. … ‘Porgy’ was created, after all, by white people. … That ‘Porgy and Bess’ is a portrait of a black community by white artists may limit the work.”

Justin Davidson of Vulture.com notes: “True, the only depiction of African-American life that makes it to the opera stage with any regularity was written by three white guys.”

The very fact that the race, gender or nationality of the artist is today uncritically presented as a central issue in evaluating a work testifies to the degeneration of bourgeois thought in general and the terrible damage inflicted over many years by identity and racial politics. The use of such criteria in past periods was associated with the political right, which employed them to promote anti-democratic and racist agendas.

While today the attack on Porgy and Bess on grounds of the “whiteness” of its creators is cloaked in the supposedly “left” trappings of Democratic Party politics and post-modernist (that is, anti-Marxist) criticism, the earlier practitioners of such an approach were more frank in giving vent to its ugly sources and implications.

Reviewing the premiere of Porgy and Bess in 1935, the prominent American composer and music critic Virgil Thomson wrote:

The material is straight from the melting pot. At best it is a piquant but highly unsavory stirring-up together of Israel, Africa and the Gaelic Isles. … [Gershwin’s] lack of understanding of all the major problems of form, of continuity, and of serious or direct musical expression is not surprising in view of the impurity of his musical sources. … I do not like fake folklore, nor fidgety accompaniments, nor bittersweet harmony, nor six-part choruses, nor gefilte fish orchestration.

Most critics and professors who attack the opera for the “whiteness” of its authors are not anti-Semites, but, whether they like it or not, there is an objective link between their approach and that of Richard Wagner, one of the pioneers of anti-Semitism in the field of music. In 1850, he authored the infamous tract “Das Judentum in der Musik” (“Jewishness and Music”), in which he denounced Jewish composers in general and Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer in particular.

A racial approach to art has a definite logic. It leads in the end to abominations such as the Nazis' Aryan art, with its book burning and banning of Jewish- and black-infected “degenerate art.”

It is a historical fact that the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants who fled tsarist persecution composed an opera that expressed in a powerful and beautiful way both the poverty and oppression of blacks in the segregated South and their nobility of spirit and burning desire for genuine freedom and equality. What is so strange or problematic about that?

George Gershwin was a genius and without doubt the greatest American composer of his time. That is an important factor to reckon with. There were and are many talented black composers—Duke Ellington and William Grant Still, to name just two—who produced great music, but none has to date produced a musical piece about the black experience in America that compares to Porgy. Unfortunately, in the attacks on the opera by some black artists—initially including Ellington, although the great jazz composer later changed his opinion—there was an element of jealousy. The same applies to composers of the academy who dismissed Gershwin’s work as technically deficient and low-brow.

How many jazz greats have performed and improvised on Gershwin tunes, including his opera? Miles Davis produced an entire album based on it. The list includes Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holliday and many more. It also includes country and pop artists such as Willie Nelson and Brian Wilson.

More than 80 years after its premiere, history itself has demonstrated the universality of Porgy and Bess. It is about black people, but, more fundamentally, it is about the human condition. Its basic themes are universal. It is a love story. It is a story about oppression, community, struggle, loss and the will to fight.

Do not songs such as “Summertime,” “I Got Plenty of Nothing” and the exquisite love duet “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” express the most profound and universal of human aspirations and emotions? Those who attack the opera for its “whiteness” generally avoid discussing the music.

Nor can there be any doubt that Gershwin’s own background, in the context of the convulsive social and political conditions of the Depression 1930s—the spread of fascism in Europe, revolutionary upheavals internationally and mass struggles of the American working class, and the approach of the Second World War—played a significant role in inspiring him to write Porgy.

During the summer of 1934, Gershwin stayed on Folly Beach, located on a barrier island near Charleston, South Carolina, collecting material and ideas for his opera and visiting revival meetings of the Gullah blacks who lived on adjacent James Island. He wrote to a friend: “We sit out at night gazing at the stars, smoking our pipes. The three of us, Harry [Botkin], Paul [Mueller] and myself discuss our two favorite subjects, Hitler’s Germany and God’s women.”

Dubose Heyward, who spent part of the summer with Gershwin on Folly Beach, published an article in 1935 in Stage magazine in which he described Gershwin’s interaction with the people who became the prototypes for the characters of his opera. “To George it was more like a homecoming than an exploration,” he wrote. “The quality in him which had produced the Rhapsody in Blue in the most sophisticated city in America, found its counterpart in the impulse behind the music and bodily rhythms of the simple Negro peasant of the South.

“The Gullah Negro prides himself on what he calls ‘shouting.’ This is a complicated rhythmic pattern beaten out by feet and hands as an accompaniment to the spirituals, and is indubitably an African survival. I shall never forget the night when at a Negro meeting on a remote sea-island, George started ‘shouting’ with them. And eventually, to their huge delight stole the show from their champion ‘shouter.’ I think that he is probably the only white man in America who could have done it.”

Gershwin himself was not overtly political, at least in his public life, but his sympathies and associations were with the liberal and socialist left. He penned Broadway shows of a broadly anti-war and socially dissident character, such as Strike Up the Band, Of Thee I Sing and Let ’Em Eat Cake. The impact of the Russian Revolution, only 18 years prior to the debut of Porgy, contributed to the generally optimistic and democratic impulse behind his music. The sister of Ira Gershwin’s wife Leonore, Rose Strunsky, translated Leon Trotsky’s Literature and Revolution into English.

The singers who worked closely with Gershwin on Porgy, including the original Porgy and Bess, Todd Duncan and Anne Brown, spoke with affection of their interactions with the composer, insisting he never evinced the slightest prejudice or condescension. They were always among the most ardent defenders of the opera.

The Gershwins insisted that the singing roles go only to black performers, in part because they wanted to break down the exclusion of African American artists from the concert hall and because they did not want the opera to be performed in blackface.

As for the element of caricature in Porgy and Bess, what opera does not have caricatures? The vengeful dwarf in Rigoletto, the seductive gypsy in Carmen, the tubercular seamstress in La Boheme, the rascally but clever servant in The Marriage of Figaro. One could go on and on. The issue is: Do the inhabitants of Catfish Row transcend their “types” and express genuine humanity? The opera’s audiences all over the world have answered in the affirmative.

And what of the charge of “cultural appropriation?” Could there be a more banal, reactionary and anti-artistic concept? What is art, if not the interaction of multiple influences of many origins, conditioned by social and historical development and distilled in the creative imagination of the artist to produce works that have universal significance?

Should we denounce Shakespeare, a male, for inventing Ophelia? Should we reject Verdi for writing operas about Egyptians? Should we ban blacks from playing white characters? What about that racist Mark Twain who had the impertinence to create the escaped slave Jim?

The balkanization of art is the end of art.

Here is how Gershwin, who aspired to create a genuine American idiom, described his own development. In an article titled “Jazz is the Voice of the American Soul,” published in 1926, he wrote:

Old music and new music, forgotten melodies and the craze of the moment, bits of opera, Russian folk songs, Spanish ballads, chansons, ragtime ditties combined in a mighty chorus in my inner ear. And through and over it all I heard, faint at first, loud at last, the soul of this great America of ours.

And what is the voice of the American soul? It is jazz developed out of ragtime, jazz that is the plantation song improved and transformed into finer, bigger harmonies. …

I do not assert that the American soul is Negroid. But it is a combination that includes the wail, the whine, and the exultant note of the old “mammy” songs of the South. It is black and white. It is all colors and all souls unified in the great melting pot of the world. …

But to be true music it must repeat the thoughts and aspirations of the people and the time. My people are Americans. My time is today.

#wsws#porgy and bess#opera#american opera#gershwin#george gershwin#wagner#broadway#broadway musicals#identity politics#racism#racialism#cultural appropriation#gullah

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi Yejide. Recently, I've been feeling a calling to explore root workin' and ancestral veneration. I've been raised Baptist and still maintain a relationship with Christ, but lately I've just been feeling this internal pull to honor my ancestors. I don't know exactly how or where to start. My entire life, I've been raised to believe that doing any kind of root work is witchcraft and inherently evil. How did you decolonize your mind and break out of that fear?

Hi anon (: Welcome to the struggle! I’m happy for you that you’re feeling the ancestral call, and I hope some of this very long response (+1.4k words, I counted lmao) is helpful in one way or another.

First off, I want to emphasize a couple different things. For one, hoodoo/rootwork is NOT the same as witchcraft at all. It can be overlapped with witchcraft and/or it can be referred to as a form of witchcraft by black folks who wish to call it that, which is a perfectly valid, personal terminology choice. However, historically, rootwork/hoodoo derives from the various ATRs (African traditional religions) that were practiced by black slaves brought to the US.

ATRs are not witchcraft either, they are traditional religions practiced by peoples indigenous to Africa that deserve the same amount of respect as any other religion in the world. The negative stereotypes about them are based on racism and attempts to dehumanize African peoples and their descendants in the diaspora who practiced their ancestral traditions. Any time you start to slip into that way of thinking about ATRs, remind yourself that they are religions as deserving of respect as any other religion.

Most African slaves in the US were forced to practice various denominations of Protestant Christianity and abandon their traditional religions or face severe punishments - even death. Hoodoo/rootwork is largely the result of many different practices and beliefs from ATRs combined together and syncretized with Christianity. It is a folk magic tradition that was developed not only during slavery but also largely within the black church. The ties between hoodoo and Christianity are very deep. You don’t have to be Christian to practice rootwork, but it’s not at all un-Christian to practice it either if that’s something you’re interested in doing. (Since you mentioned you still maintain a relationship with Jesus, I figured that might be something you’d wanna look into.)

The majority of traditional rootworkers in the US have always been and still are Protestant Christian. It’s traditional in hoodoo to pray to Jesus during workings, and it’s said that Moses himself was the very first rootworker in history. Why? Because the original Christian rootworkers viewed rootwork as powerful prayers, asking for the help of God to heal, protect, and sometimes issue divine judgment. Hoodoo wasn’t traditionally seen as witchcraft at all, and in fact, has long been used as a method for fighting against witchcraft. Many of the most respected and famous rootworkers in history were also preachers and pastors. Some consider being a good church-going Christian as a pre-requisite to being a rootworker. The Bible itself, especially the Book of Psalms, is traditionally viewed as a powerful source of hoodoo magic.

Now, I’m not sure if you were already aware of any of this or if this information is helpful to you, but I think it’s important for anyone studying hoodoo to understand this side of its history whether you want to connect with these aspects of it or not. If you’re curious at all about my personal journeys of dealing with Christian views on witchcraft and also decolonization within my magic and religious practices, see the mini-novel I ended up writing at 3 am for this ask under the read more line below 😂😂😂

[ Ask me anything ] [ Buy me a coffee ] [ Spirit Roots Shop ] [ About Me ]

It took me about a solid ten years to get to where I am now with decolonizing my mind and breaking out of Christianity-related fears around magic practices. I’ll still always be in the process of decolonization for the rest of my life, but within the past few years, I’ve made some big strides that I’m very proud of for myself. As I hope most of my followers know, I’m not a witch and don’t identify as one for personal and historical + cultural reasons within the context of Africana traditions. BUT that being said, for much of my life I did identify as a witch and actively study witchcraft for a very long time.

I declared myself a Wiccan at the age of thirteen, which was inspired by watching Charmed, yes, but that didn’t lessen the seriousness of it for me as being an actual religious path and practice I wanted to commit myself to. Being an only child who told my very liberal parents everything, I quickly confessed this to them expecting acceptance and happiness for me. Unfortunately, their Christian knee-jerk reaction alongside concerns about a thirteen-year-old learning about witchcraft, fertility rites, and sex-related rituals was enough for them to give me an ultimatum to stop being both a Wiccan and a witch.

That sent me deep into secrecy about it for around a solid 8 years or so - essentially all the way through high school until I had more independence in college. During that whole time, I always felt like I was genuinely a witch and Wiccan and no other religion fit me, but I was too scared to practice because of my parents’ reaction and them having “banned” it. I remember that constant longing mixed with fear of being a witch in my heart while feeling like it would never actually be accepted by anyone in my life.

During college, I finally realized that I could practice it more actively without worrying about my parents anymore. I remember going through all the stages of testing the waters with that, the ex-Christian pangs of guilt and intrigue, the concerns about what Drew and my friends would think and then being the cool and edgy witchy friend after finally mustering the courage to tell them. It was like I could finally be who I always knew that I was inside, but it had required a long process of unraveling the shame and the guilt and the fear, too.

Now, to be totally honest with you, I wouldn’t consider ANY of that decolonization. That was really just my journey of breaking away from a mostly Christian upbringing (my Jewish roots didn’t really play an anti-witchcraft role at all tbh) and finding the freedom to more openly be a witch and deepen my practice of witchcraft and of Wicca. Beginning to decolonize for me was a whole other journey that started soon afterward.

Fast forward to after I started studying Wicca in enough depth as a college student that I realized it really wasn’t for me and ended up converting to Buddhism instead. In a roundabout way, it was converting to Buddhism that sent me down a very different path. I was and still am a very devout Buddhist, but even though the buddha dharma is universal, Buddhism as a religion is deeply rooted in Asian cultures which is not a part of my heritage. As my Buddhist practice deepened over time, so did my longing for ancestral traditions and practices. This is what got me started with ancestor work and studying hoodoo, which is what eventually led me to an interest in ATRs and Ifá in particular. Even reconnecting with my Jewish heritage and identity was a part of this journey to tap back into my ancestral practices and spirituality.

The more I learned about these Africana traditions, the further away I got from Eurocentric ways of thinking about spirituality and magic. Converting to Buddhism from Wicca began my big push away from Eurocentric frameworks, and getting involved with hoodoo and Ifá only cemented that even further for me. Yes, witchcraft can be defined in whatever way one wants so I’m not saying people can’t practice completely non-Eurocentric witchcraft - some people absolutely do that. But for me personally, leaving the concept of “witchcraft” and the identity of “witch” behind completely was even more liberating than reconnecting with it in the first place had ever been. This was a huge part of my personal decolonization process for many different reasons.

That’s all a very long story and explanation, but that’s essentially my point. It can literally take decades to undergo the personal journeys necessary for unraveling and growing beyond what you were raised to believe and what society impresses upon you. Growing up in a very Christian household and in a Western society that enmeshes you in Eurocentric ways of thinking makes it extremely difficult because that’s all your surrounded by for most of your life.

Unfortunately, there’s no handbook or manual guide for all this. It’s very challenging and difficult. One thing I wish I had had more of through all of it was support from role models and mentors to understand better where I was going and where I wanted to end up. Maybe if I had, these journeys might have been a bit shorter and smoother. If you can, find communities and mentors who can help you grow, but also always listen to your instincts and your own intuition. I wish you the best of luck on your way

#ask#personal#witchcraft#christianity#hoodoo#rootwork#conjure#psalms#buddhism#eurocentric#eutradtattoo#wicca#atr#ifa#aboutme#slavery#blackhistory

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

European Project, Baltic Dream, Paths Forward Where American Dream Falters

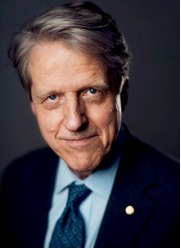

Robert J. Shiller, Sterling Professor of Economics at Yale University, 2013 Nobel Laureate, and kin to four Lithuanian grandparents, addressed attendees at the Baltic Boston Conference on November 24, 2018, commemorating the Baltic centennials.

Professor Shiller spoke about the evolution of “The American Dream,” a notion that was coined and lauded in 1931; and compared it to the European Project and the “Baltic Dream”.

Using search tools Ngram and Proquest, Schiller traced the American Dream origins to the nation’s founding thinkers, including Thomas Paine, who challenged the logic of hereditary advantage in Common Sense (1776); and Ben Franklin, who in 1782 France published the pamphlet, Information for those Who would Remove to America.

“Don’t come to America if you think you will impress people with title and money,” Franklin wrote. “Come if you can do something. Americans say, ‘God Almighty is a mechanic.’” Franklin claimed the humble husbandman (farmer) would be respected in America.

A sister concept to the American Dream was portrayed by Israel Zangwill in his 1908 play, “The Melting Pot,” wherein a Jewish man marries a Christian woman. President Teddy Roosevelt applauded the play, making assimilation, the coming together of different nationalities and cultures, the preferred face of the nation (rather than, for example, the Jim Crow laws of the day*).

In 1930, “The American Dream” was advertising copy for a box spring mattress. (It cost $13.50).

In 1931, “The American Dream” was coined by historian James Truslow Adams in his book, Epic of America. (So named because Adams’s publisher said a book entitled The American Dream wouldn’t sell.) With that phrase, Adams was defining a hopefulness that he admired in American culture.

"…that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone (emphasis added), with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement. … It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of social order in which each man and each woman (ahead of his time, Prof. Shiller points out, Adams specified both genders) shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position."

“Ideas are contagious,” explained Shiller, “like viruses, thoughts change and mutate over time, their popularity goes in and out.” In the depths of the Great Depression, the hopeful idea of the American Dream was born, its roots already established in the nation’s consciousness, and the notion went viral.

Immigrants came to America because of the American Dream, some aspiring to own farms – one version of the Dream. America attracted hardworking people. Every young activist thought of the United States as a bastion of freedom and democracy.

Continuing the etiology, in 1931 and 1961, respectively, playwrights George O’Neill and Edward Albee* used the title with irony, dealing with the disintegration of the American Dream.

The American Dream doesn’t mean today what it meant in 1931.

1950 real estate ads painted the American Dream as home ownership: Man marries and children arrive. Man gives them a place to call their own. The ideal was a suburban home, where couples could entertain using their stylish wedding gifts. The concept had lost its idealistic and intellectual tenor since 1931, even neglecting the original idea of inclusion.

The American Dream further mutated by1980, when homes became thought of as investments. Prof. Shiller pointed to the shift in public attention from land prices to home prices, among other proofs.

Today, suburban home ownership no longer represents the American Dream. Walkable cities offering art, community space, and eateries, make life meaningful to young people.

In 2018, Frank Rich wrote in New York magazine, “That loose civic concept known as the American Dream … has been shattered. No longer is lip service paid to the credo, however sentimental, that a vast country, for all its racial and sectarian divides, might somewhere in its DNA have a shared core of values that could pull it out of any mess.”

The American Dream is history*.

Across the Atlantic, the counterpart to the American Dream is often referred to as the European Project. In contrasting the two mindsets, Jeremy Rifkin explains:

For Americans, freedom is associated with autonomy, which requires amassing wealth. One is free by becoming self-reliant, an island unto oneself — and with exclusivity comes security.