#epic iii

Text

youtube

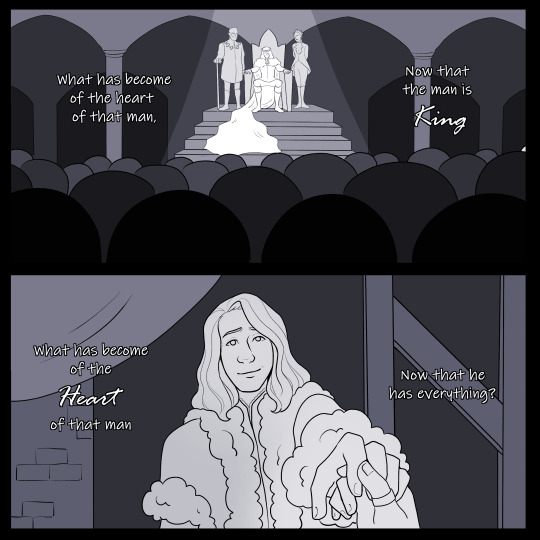

a little reunion animatic

#art#animatic#tagamemnon#the odyssey#odyssey#odysseus#penelope#greek mythology#epic iii#hadestown#so I skipped some steps haha#with the whole her tricking him thing#this is fully inspired by that one passed in the Odysseys where Penelope runs down to meet Odysseus (though not at the bed) and finds him s#eyes on the ground#waiting for her to react#which.#devastating thanks homer#also a funny visual#but mostly heartbreaking#Youtube

812 notes

·

View notes

Text

"'Cause here's the thing,

to know how it ends,

and still begin to sing it anyway,

as if it might turn out different this time."

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hermes: And Hades and Persephone, they took each other's hands – and brother, you know what they did?

Me, sobbing: tHeY dANcEd

#hadestown#hadestown the musical#hermes#hades#persephone#epic iii#andre de shields#anaïs mitchell#patrick page#amber gray#reeve carney#eva noblezada#broadway#musical theatre#not me randomly getting emotional over my favorite musical again

711 notes

·

View notes

Photo

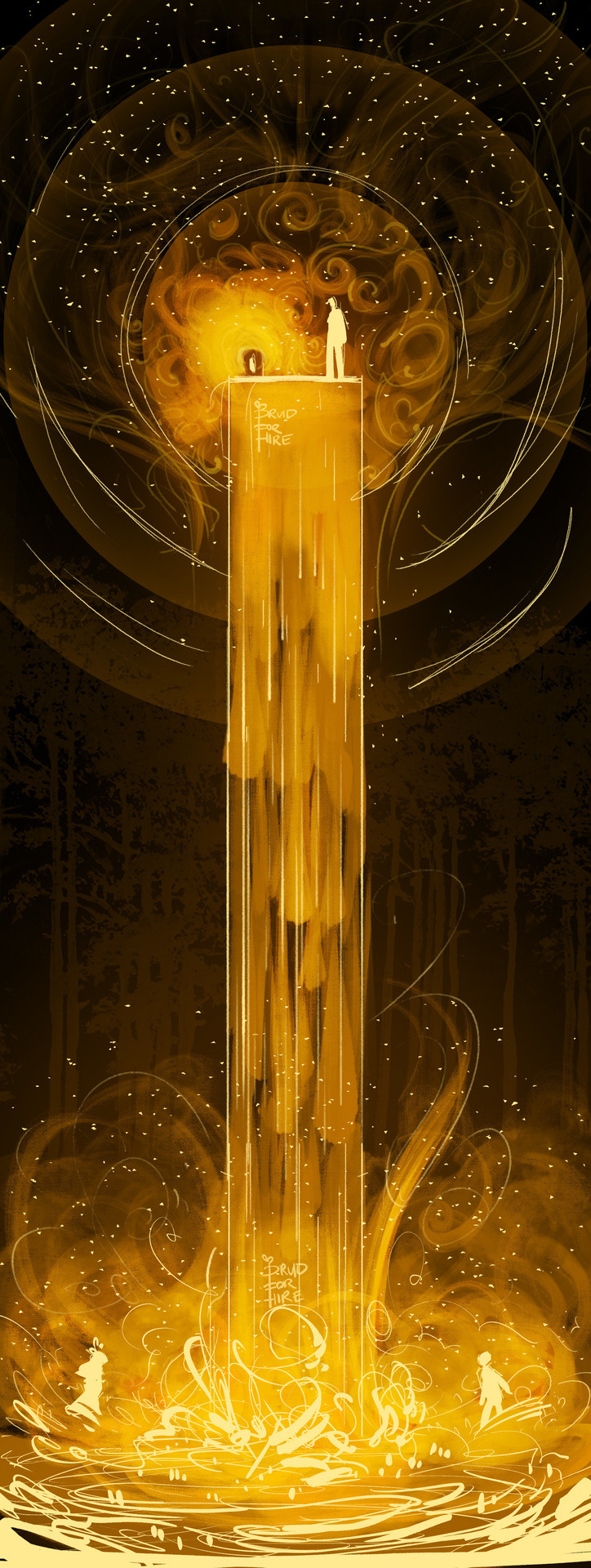

epic iii by @druid-for-hire

#hadestown#orpheus and eurydice#epic iii#orpheus#eurydice#hades#persephone#greek myth#art#reeve carney#eva noblezada#patrick page#amber gray#epic iii art#hadestown nytw#hadestown broadway

722 notes

·

View notes

Text

I saw Hadestown last night.

I may have really liked it.

#epic III#you know?#the part where Hermes goes#and brother do you know what they did#they danced#yeah that#probably no one will see this or care#but I thought I’d post it anyway because#I think it turned out nice#and I was experimenting too#🥺#I don’t actually ship these two#I just think they fit these roles nicely#hadestown#springtrap#ballora#springtrap x ballora#fnaf#five nights at freddy's#fnaf sl#fnaf sister location#fnaf 3#springtrap fanart#ballora fanart#what other tags…#none?#none

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

Musical Theatre Song Contest: Round Five

youtube

youtube

Submitter’s propaganda under the cut

If I Were A Rich Man

I’m learning the melody on the flute! Very fun song!

"I realise of course that it’s no shame to be poor, but it’s no great honour either"

No propaganda submitted for Epic III

#musicaltheatresongs#song polls#round five#if I were a rich man#fiddler on the roof#hadestown#epic iii#Youtube

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

So about that new Epic III verse, eh?

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

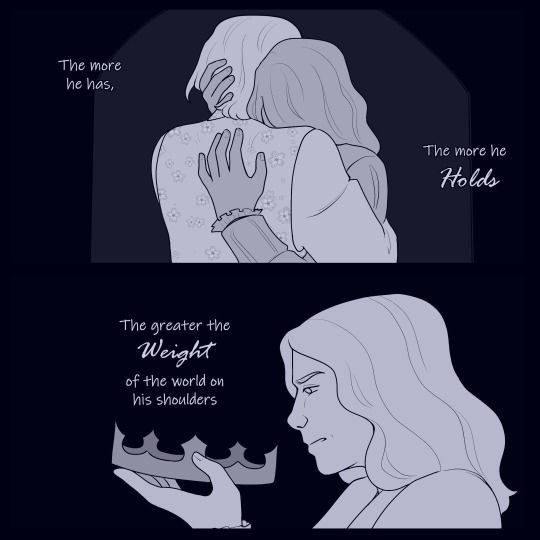

Full context for each beneath the cut, because the poll options have character limits and the Epics are LONG:

King of diamonds, king of spades / Hades was king of a kingdom of dirt / Miners of mines, diggers of graves / They bowed down to Hades who gave them work / And they bowed down to Hades who made them sweat/Who paid them their wages and set them about / Digging / And dredging / And dragging the depths of the earth / To turn its insides out (Vermont, Concept Album, NYTW)

And he bowed down to no one, below or above / 'Til the arrow of Eros struck him in the heart / And the king of the underworld fell in love / With a woman who walked in a garden (London)

And the earth warmed over in the dead of winter / The stillborn spring lay cold beneath / Summer gave a stormy sermon / Autumn walked in its wake like a wreath / And the people moved like weather patterns / Looking for shelter, looking for warmth / Helter-skelter, the four winds scattered / The scavengers over the ravaged earth (Vermont)

And a million feet that fell in line / And stepped in time with Hades' step / And a million minds that were just one mind / Like stones in a row / As stone by stone / Row by row / The river rose up (Concept Album, NYTW)

Hades is king of the scythe and the sword / He covers the world in the color of rust / He scrapes the sky and scars the earth / And he comes down heavy and hard on us (Concept Album, NYTW)

And the sun rose and fell in his chest as he held her / He felt the earth moving without and within / And there were no words for the way that he felt / So he opened his mouth and he started to sing (London)

The heart of the king is a tinderbox / That he has to keep under lock and key / That it not catch fire inside of his chest / 'Cause a lover's desire is a mutiny / A lover's desire is a wilderness (Vermont)

In the dark of the mine, he is trying to fill / The hole that his lover has left in his arms / With the silver and gold / He can have and hold / Not half, but whole / All to himself (Broadway previews, with some lines from Vermont)

(Source: Anaïs Mitchell, Working on a Song)

#tumblr polls#hadestown#anaïs mitchell#hadestown nytw#hadestown broadway#working on a song#epic i#epic ii#epic iii

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

The West End lyric change for Epic III seems to (in part) be pushing more and more for Orpheus and Eurydice to mirror Hades and Persephone. Not only does Orpheus "know how it was" to fall in love, but now he knows "how it is" to be left alone like Hades. There's that new hole of doubt that is there in his mind as he tries to take Eurydice home.

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi. Recent fan. I don't know if you're still involved with the Hades and Persephone Vegebul AU, BUT!

Hadestown Epic III, (Live recording. Not the official track on broadway), the first half of the song. When Vegeta meets Bulma because:

But even that hardest of hearts unhardened

Suddenly, when he saw her there

Persephone in her mother’s garden

Sun on her shoulders, wind in her hair

The smell of the flowers she held in her hand

And the pollen that fell from her fingertips

And suddenly Hades was only a man

With a taste of nectar upon his lips, singing:

La la la la la la la…

I just think it would be lovely.

so i loved your question so... i listened to it and now it's my head ;-;!!! Good choice!

#vegeta#bulma#vegebul#vegeta hades#bulma persephone#hades#hadestown#persephone#dragonballsuper#dragon ball#dragon ball z#epic iii

337 notes

·

View notes

Text

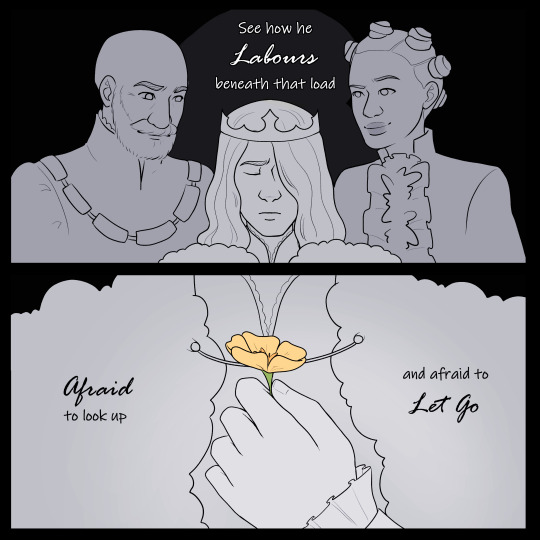

First Hadestown comic!!! I’m afraid Hades is broken😔

#hadestown#hadestown memes#hadestown fanart#hades#persephone#orpheus#hades x persephone#epic iii#hadestown broadway#I made Orpheus’ arms so skinny😭😭#I apologize😔#My art

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just really love this show and I’m so happy to see it hit five years on Broadway

#artists on tumblr#hadestown#hadestown fanart#epic iii#hades#Persephone#animation#this took a whole dang week#animating is deeply fulfilling but it’s no joke

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

HAPPY SECOND BIRTHDAY TO EPIC III !!

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I’ve seen that a lot of people like the off broadway version of epic iii more, and I totally agree. /but even that hardest of hearts/ is one of my favourite lines in the whole musical

But i think the change that I personally dislike the most is taking out Persephone’s monologue in Chant ii. Like cmon the parallels

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

epic iii but in a cathedral

do yourself a favor and listen

#hadestown#hadestown nytw#orpheus and eurydice#orpheus#eurydice#epic iii#hadestown art#hadestown edit#goldsong vomits

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Musical Theatre Song Contest: Round Three C

youtube

youtube

Submitter’s propaganda under the cut

All You Wanna Do

Deeper symbolism, catchy pop that reflects characters and gut wrenching lyrics and dance symbolism. As well as in one version she didn’t stop weeping after her head was cut off.

It's catchy and fun but also really sad and just. Very well done. Especially the live version where she sobs at the end

This song was mindblowing the first time I heard it. It lures you in with a catchy beat, then slowly, you start realizing how deeply fucked Katherine's story is and how disturbing the song is. It's amazing.

A really upbeat peppy song that makes you sympathize with the protagonist but simultaneously makes you feel murderous

The way the chorus gradually changes from boasting about how men want to sleep with her to despair that that’s all they want is just so

#musicaltheatresongs#song polls#round three#round 3 c#all you wanna do#six#epic iii#hadestown#Youtube

22 notes

·

View notes