#forensic genealogy

Note

DEATH TW and mentions of murder so if that is triggering for you don’t read, but if it’s not then i’d like to ask if you’ve heard of forensic genealogy? while i am uneasy at the prospect of using it to find suspects, it can also be used to find the identities of unidentified decedents, who die of accidental causes or are murdered, and often it’s the only hope to identify those who have been unidentified for decades. the dna doe project is a nonprofit that’s mostly volunteer run, and i think that your research skills could be useful there or somewhere like there. i know this is kind of a random ask to receive, identification of unidentified remains is my special interest but i don’t have the time or training to get better at researching beyond a few tricks here and there.

I feel like we've read the same articles recently; did you see the tumblr post (and linked articles) about Joseph Augustus Zarelli, the Boy in the Box?

Which is to say, yes, I am aware of forensic genealogy and the DNA Doe Project, because like many white American women, I'm a true crime junkie.* My big Thing is investigative procedure tho, so I'm also deeply interested in plane & train crash investigations, medical mysteries, archaeology, anthropology... basically 'what happened, and by which processes and methods do we figure out what happened?'

So far as getting into the game myself, I dunno. I assume there's probably some sort of required formal training, along with the expectation of reliability and sustained effort, and I'm a chronically ill autodidact with ADHD. I'm the research equivalent of a sprinter; investigative genealogy requires a marathoner, because there's so much exhausting, grinding work involved.

Something I've never seen brought up before in any investigation is how many extant family trees are just wrong. Genealogical sites make it too easy to crib notes from other users, and all it takes is one person deciding 'eh that's probably the right guy' for dozens of other amateur researchers to make the same mistake, and then somebody ties that erroneous information to their DNA profile. I don't know how the forensic genealogists deal with that.

You also have to take into account how many people throughout history have just gone missing, or otherwise fallen off the historical record. Just because someone's date of death is absent doesn't mean something nefarious happened to them. (Just because someone's date of death is present doesn't mean it's correct.) People emigrate. They marry. They change their names. They die alone and unknown in a ditch**, or they die somewhere that doesn't make those records public***. Paper records can burn or flood out, and family stories rarely make it down more than one or two generations. History is messy.

I've only done serious research into my family background for two years, in fits and starts interrupted by illness flare ups. Half the time it feels like I find more questions to ask than I get answers. I've found a pair of illegitimate daughters and a handful of adoptees. I've found some two dozen 'missing persons' who may as well have disappeared into thin air, for how suddenly they dropped out of the historical record. I've found a murder victim and a (maybe) would-be murderess.

And four months ago, I found the answer to another family's 150 year old missing person case, and it changed everything I thought I knew about my mother's family.

This is how.

Five months ago, I thought I knew everything there was that could be known about John Robert McDowell.

I knew he was born July 1st of either 1868 or 1869, in Belfast, Northern Ireland. According to his naturalization petition, he came to the United States in April of 1883, when the absolute oldest he could have been was fourteen, and at the time of his naturalization in 1896 he claimed his nationality was English, presumably due to anti-Irish sentiments at the time.

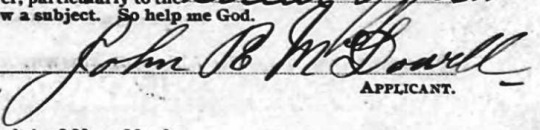

I knew John's handwriting was idiosyncratic: he wrote the J in his name with a rightward upper loop that scooped up again before curving back around the center staff, and his uppercase R was a mess of curlicues. I've never seen the like before or since.

I knew that despite living in America for ten years longer than he'd lived outside it, John still had an accent in 1908 when his second son was born. Spelling is incredibly inconsistent across historical records because up until very recently, it was the practice of the record keepers to write down their best guess at what they heard, and in 1908 a midwife heard and recorded John's surname as McDoul.

John's life was actually remarkably well-documented, in comparison to his contemporaries. I bought myself access to Newspapers.com along with my Ancestry subscription, and he made semi-regular appearances in the Newport News Daily Press for the better part of thirty years as a Navy veteran, successful entrepreneur, and president of a labor union that later became the United Steelworkers Local 8888. (A seemingly throwaway notice in the Daily Press was the only record I've yet been able to find for his divorce, which eventually led me to find out whatever happened to his wife, which is another saga entirely. Pauline, you dirty rotten cheater.)

I knew that John was in and out of the hospital with thyroid cancer, but he was such a tough old bastard it took the better part of fifteen years to kill him, and he died in 1954 at the age of 86.****

According to John's death certificate (and the U.S. Government records at the VA hospital where he died), his parents' names were Thomas McDowell and Isabell Rabb (or possibly Robb, the Accent strikes again.)

This is the only record linked to either of them on Ancestry.com at all.

I have most of a history degree, so I wasn't surprised. There are next to no records of the 1890 census of the United States, and that was down to a fire in the National Archives. Ireland was dragged backwards through hell by the ankles for centuries by a succession of British monarchs and governments, and Belfast was in the prime of especially conflicted territory for much of it. No census records from John's lifetime were kept, and the likelihood his parents would show up in the surviving fragments from 1841 and 1851 was slim to none.

There were transcribed indexes from birth and marriage records available, at least, and I scoured them through, looking for a John McDowell, and there wasn't a single damn one born to a Thomas or Isabelle McDowell in a decade on either side of 1868. There wasn't any record I could find at all of a Thomas McDowell marrying an Isabelle Rabb until well after John left Ireland.

Five months ago, as far as I knew, John Robert McDowell was probably a bastard, who'd either been left out of whatever records were taken at the time, or he was one of the unfortunate ones whose birth record had been lost.

Four months ago, I realized that the record indexes on Ancestry included film numbers, which meant there were pictures of those records to be found somewhere. If they were organized chronologically, I could try to find his birth registration that way. Googling "ireland civil registration records" brought me to the Civil Records search page of a genealogy site run by, of all things, the Irish government's tourism department.

Once again, there wasn't a John McDowell born to the right parents during the right time period, so I went looking for his parents' marriage. And found it.

If they married in 1872, John would probably still technically be a bastard, but I had a point to start from. Once I clicked into the actual scan of the record I nearly snapped myself in half sitting upright in attention, because Thomas McDowell's father's name was Duncan, John named his eldest son Duncan, Isabella's father's name was John, I had to have the right two people, this couldn't be a coincidence.

And then I noticed Isabella was a widow. Isabella was a widow.

Who was your husband, and when did he die, Isabella? I searched again, and found her marriage to a Thomas Logan July 30th, 1866. No men named Thomas Logan died in Belfast between 1866 and 1870, which meant he was probably still alive when John was born. It meant I had been looking in the wrong direction the entire time.

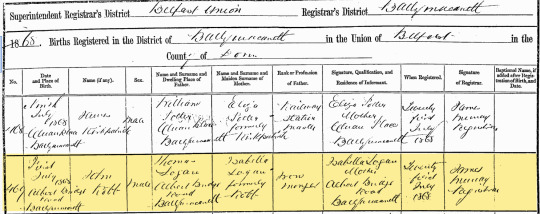

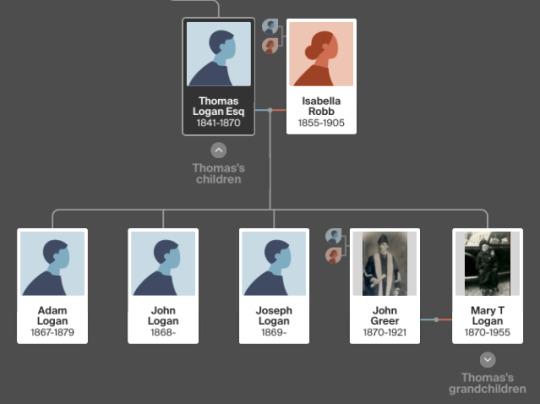

John Robb Logan came into the world on July 1st, 1868, in the Ballymacarrett district of Belfast, the second child of four born to Thomas Logan and Isabella Robb. Once I knew what I was looking for the rest came easy.

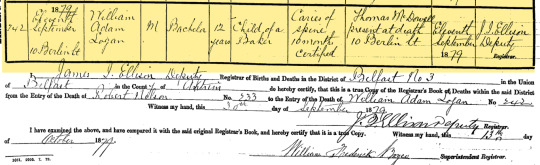

John's early life was riddled with tragedies. His younger brother Joseph was six months old when he died in March of 1870. His father died of smallpox in December of the same year, exactly one month after the birth of his sister Mary. Three months before his fifth birthday, his first half-sibling Bella died, at just five months old. And in 1879, his older brother William died after a long, miserably drawn-out illness from spinal tuberculosis.

(As an aside, god, poor Isabella. She had four children with Thomas Logan, and a further nine with Thomas McDowell, and before her early death from a long respiratory illness she buried a husband, two sons, and two daughters. How do you go on after that, how are you not forever shattered?)

If I hadn't been sure I'd found the right family, I was after William died. Thomas McDowell was the person who reported William's death to the registrar's office after sitting by his deathbed. The registrar recorded William as a "child of [the] baker" that Thomas was by profession; Thomas McDowell claimed his stepson as his own.

Duncan McDowell, John's step-grandfather, had a family burial plot in Ballygowan, and he named William Adam Logan as his grandson, with no qualifiers, when they buried him.

All the evidence suggests that the McDowells loved John Robb Logan and his siblings, and he loved them back every bit as much. You don't choose to take on the surname of people you hate, and it seems very much the case that John chose to go by McDowell when he came to America. I'm honestly not sure there was a way for Thomas McDowell to bequeath his name to his stepchildren, given John's brother William died a Logan and his sister Mary married as one.

John Robb Logan disappeared from history after his baptism, and John Robert McDowell made his first confirmed appearance in the historical record in 1883, but I was certain they were one and the same. The problem was proving it to my mother, because McDowell was her family name. She'd grown up with it, as had her sisters and her dozens of cousins and her father and his siblings and her father's father; I only had a paper trail arguing the name she knew didn't belong to any of them by blood.

So I went for blood.

I refuse to give my DNA to Ancestry.com on a principle born from paranoia and ethics concerns. It's absolutely not happening, ever, like hell do I expect a corporation to do the right thing with my genetic material. My mother doesn't share my concerns, either now or four years ago, when she bought an Ancestry DNA kit and then did absolutely nothing with her results besides marvel at the unexpected Swedish heritage in her 'Ethnicity Estimate' because doing anything else looked like too much work.

It took a few days to figure out how to hook my mother's DNA results into the tree I've built, and a few more for all the features to populate, but all told it took less than a week between learning the truth about my great-great-grandfather's parentage and proving it irrefutably with DNA, via several descendants of his full-blooded sister Mary and a grandson of his half-brother Wallace.

Ancestry doesn't tell you when new DNA matches are found, or when someone adds you to their tree (and thank god for that, my mother has somewhere in the neighborhood of twenty thousand matches). To those descendants of Mary Thomasina Logan, the handful of John's descendants who've shelled out for Ancestry DNA kits could be any random person. Frequently the relationships between matches aren't clear, because of all the folks like my mom who never add a tree to their results, or those who don't try to go any further back than their grandparents.

As far as Mary Logan's descendants know, the sons of Thomas Logan dead-ended his line, and when I do find John in their trees there's never more than a birth year and a blank space where there would usually be a year of death. (They all have the wrong Isabella Robb too, but I don't really blame them; apparently Isabella was one of the most popular names for girls for well over a century, and Robbs weren't exactly thin on the ground.)

Someday soon, I'm going to reach out. People who study genealogy do it because they're looking for something: long lost relatives, answers to questions asked too late, or even a better, more personal understanding of history by learning about the people who were there when it happened. Every family has its mysteries and this one, at least, could be solved.

John's story doesn't end here. Here is where it begins.

~

*I'm aware of the problematic nature of White Lady True Crime Brain Poisoning, but I'm gonna have to pull the 'I'm not like other girls' card. I'm incredibly discerning about my crime shows, I hate the fucking cops, and I'm realistic about how unbelievably low my chances are of ever being the victim of a violent crime. I'm white, I'm broke as shit, I'm built like a running back and walk like the Terminator, and most importantly, I'm single and planning to stay that way for the rest of my life. The only way I'm getting murdered is if I happen to get caught in a random mass shooting, which isn't outside the realm of possibility because America.

**In case anyone's gotten this far and is still interested, there's strong evidence that the mystery of the Somerton Man was finally solved last year. At some point I'd like to take a look at the tree the forensic genealogists built tho, because I have some Doubts. There was only one person in that family that fell off the map in the 40's? Just one? I was lightning-strike kinds of lucky enough to find John's real parentage, but I dug up more unanswered questions with it, because two of his half-brothers dropped out of the records after 1901. Completely setting aside the possibility of infidelity in the Webb family and how common inbreeding has been (both historically and in recent memory) in populations of European descent, I have a hard time buying that Carl Webb was the only person who could be the Somerton Man. It's still cool as shit that they have a strong possibility tho.

***Maryland and Kansas specifically can blow me, if somebody died in either of those states I have to find an obituary or a tombstone to get the mcfrickin' date, and I have to either pay money and prove a relationship to see a death certificate, or show up to an archive in person to search on their intranet, MARYLAND WHY DO YOU NOT WANT ME TO KNOW WHEN MY GREAT-GRANDMOTHER DIED. (Being fair, I don't know if she died in Maryland, that's just a great-uncle's best guess, because she ran away from her family in 1949 and nobody ever saw her again after the early 60's. Helen, where the hell did you go?)

****One of the big reasons why I got into genealogy in the first place was to see if I could find how far back the predisposition to early deaths and autoimmune disease went in my family. What I hadn't expected to find was a predisposition for extreme longevity on all sides. Longevity as in 'skewing the life expectancy bell curve' kinds of longevity. As long as someone didn't come down with a freak illness or make a looooooooong string of poor life choices, they were apparently immune to death, which honestly explains a few things about Crazy Grandma, god damn.

#genealogy#forensic genealogy#research throwdown#storytime with stella#long post#I'm seriously not kidding it's a long goddamn post#image heavy#all images described in alt text#I don't think I did a particularly great job communicating why I shouldn't get into this professionally#this took a long goddamn time to figure out#I think most people want answers quicker than *checks back of hand* seven-ish months?#fwiw my mother took it remarkably well#our big family mystery has always been What Happened to Helen?#that was probably the central question of my grandfather's life: not knowing what happened to his mother#so that was my mom's big question too#and luckily we had other weird familial circumstances as precedent#me: 'heyyyyyyyy uh so great news yr great-grandfather wasn't a criminal on the lam OR a bastard child. he was kind of adopted?'#mom: 'adopted??? huh. like your grandpa with the mudds?'#me: '....actually. yeah. almost *exactly* like that. but like if grandpa changed his last name and then never told you he'd done it'#tho I still have no idea why john changed 'robb' to 'robert'#my theory for a long time was that he was just REALLY leaning into the scottish heritage; the guy named his sons duncan & bruce#then I learned about irish naming conventions and while that answered some questions it just wound up leaving me with MORE questions#I went through all 8 stages of grief a year ago when I figured out john's presbyterian funeral meant the fam married into catholicism LATER#and thus were probably scots colonizers to the plantation of ulster instead of former gallowglasses#I don't love the idea of my ancestors being unionist kiss-asses#which the naming scheme kinda supports#but john was a LABOR UNION ORGANIZER#he left well before the clearances in the 20's but labor activism was synonymous with catholicism & nationalism for aaaaaaaages#he had to have picked that up from a parent. two of his half brothers (who also emigrated to the states) were union members too

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unlocking the Past: The Power of Forensic Genealogy in Modern Crime Solving

In the world of criminal investigation, where every piece of evidence counts, a remarkable tool has emerged in recent years that has transformed the way crimes are solved.

#Forensicgenealogy #forensicscience #forensicfield #dna #crime #crimescene

Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book review: THE DESK FROM HOBOKEN

I love a good mystery, and have been gravitating towards cozy mysteries lately. The Desk From Hoboken by ML Condike one doesn’t quite have the quirky, lightheartedness that would make me categorize it as a “cozy”, though. Instead, The Desk From Hoboken is a quiet, thoughtful mystery that offers excellent twists and turns and emotions – not at all what I expected, but so much more! Read on to…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Australia's First Forensic Genealogy Breakthrough: How Police are Solving Cold Cases

More than four decades ago, a teenager named Andrew Bennett stumbled upon a grim discovery that would remain shrouded in mystery for years in the heart of the Kangaroo Island bush. As he and a friend ventured away from their local tennis courts, they stumbled upon the skeletal remains of a man mere meters from a main road. Little did they know that this discovery would kickstart a journey toward…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Quote

I did not know it at the time (although I have certainly learned it since), but solving really challenging DNA cases or crimes often seems to require a random twist of fate— a moment when something unprecedented happens that defies probability and ends up being just the thing you need to keep going. When that happens it feels as if the universe is nudging the case along. A document that was believed destroyed is found; a person who refused to do a DNA test has a change of heart; information that once appeared completely inaccessible no longer is. I have referred to these lucky happenings as my guardian angel.

Barbara Rae-Venter, I Know Who You Are: How an Amateur DNA Sleuth Unmasked the Golden State Killer and Changed Crime Fighting Forever

1 note

·

View note

Link

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mystery of Somerton Man SOLVED after 73 years as DNA finally identifies body

For decades, authorities, academics and the public alike have traded theories about the identity of the mysterious Somerton Man, whose body was found on a beach outside of Adelaide, Australia, on December 1, 1948. He was a Russian spy. A jilted lover poisoned by his paramour. A smuggler!?

The truth, however, is seemingly more mundane. A new DNA analysis suggests the Somerton Man is Carl “Charles” Webb, an electrical engineer from Melbourne who vanished from the public record in April 1947.

Colleen Fitzpatrick, a forensic genealogist who specializes in using DNA to solve cold cases, identified the Somerton Man using hairs caught in his death mask. To narrow down the pool of potential candidates, Fitzpatrick plugged the Somerton man’s DNA into the genealogical research database GEDmatch. After finding a match to a distant cousin, the researchers constructed a family tree of some 4,000 people. They then used archival records to search for individuals whose biographies mirrored what was known about the Somerton Man. Webb, who was born in the Australian state of Victoria in 1905, fit the bill.

On the matter of how he died city coroner said; “There was no indication of violence, and I am compelled to the finding that death resulted from poison, But I cannot say whether it was administered by the deceased himself or by some other person.”

Authorities in Adelaide exhumed the Somerton Man’s body last May and are currently conducting genetic testing on the remains. The last mention of Webb in the historical record dates to April 1947, when he left his wife. In October 1951, three years after the Somerton Man’s death, Dorothy placed a notice in the Age newspaper stating that she had begun divorce proceedings against Webb on the grounds of desertion. By then, Dorothy had moved from Melbourne to Bute, a town 89 miles northeast of Adelaide.

Records showed that Webb enjoyed reading and writing poetry, as well as betting on horse races. He had a sister who lived in Melbourne and was married to a man named Thomas Keane—likely the T. Keane whose name appears on the clothing in the Somerton Man’s suitcase. (As for the American origins of the attire, Abbott speculates that Keane bought the clothing second-hand from a G.I. stationed in Australia.)

Plenty of questions surrounding the case remain: Why did Webb come to Somerton Beach? What was his cause of death? Did he die by suicide? Was he murdered? These answers still remain and being looked into still.

There’s almost a sequel film here, not of ‘who is Somerton man?’, but now it’s ‘the mysterious case of Charles Webb’.”

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another month, another book review coming weeks after I finished the book! Which is absolutely because I wanted to be sure this was the best thing I read this month, and not because I procrastinated and then forgot….

Lay Them to Rest by Laurah Norton is about Doe cases, specifically about one Doe case which the author and her friends work to solve, with asides into forensic techniques and other topics related to Does. (Does being unidentified remains, for the true crime uninitiated.)

I found it engaging and enlightening, for all that I already knew a fair bit about the techniques and the complications of Doe cases. The case was intriguing, one of those almost impossible mysteries, and following Norton as she shadows the scientists and other crime-adjacent folks was really interesting. There's an anthropologist, a dentist, a sketch artist, and a genetic genealogy lab, among others, and Norton takes care to show their day-to-day, what their workload is like, their personalities, all of that. For instance, the anthropologist isn't just looking into this Doe case; she's got a handful of others, which also get discussed as further examples of what unidentified remains can be like.

Norton talks pretty fairly too about why cases go unsolved. I'm so used to the true crime podcast polarizations—either the police are fantastic, or the police are at best incompetent—that having someone point out that it's actually really hard to solve a crime when all you have is, say, a decapitated head at a dump site, was refreshing, or at least injected a bit of perspective. There's not much you can do to solve a case with scant evidence, no matter how much you want to, especially in the days before DNA.

(This was also kind of a sad book, for that reason. I kept running up against reasons why this, and other, cases went cold, and wanting the same resolution for them as Norton does, while knowing why that wasn't likely to happen. And worrying about the families of Does, who're missing people and may never know they've been found.)

Lay Them to Rest isn't a dry book, despite the science, or a dark book, despite the subject matter, which is certainly gruesome in places. It feels very much like a thoughtful, caring, self-deprecating memoir with science added in to illuminate it, though it's clear explaining the science was one of Norton's goals. If you're interested in Does and missing persons, or in citizen detective work, and you're okay with some disturbing details and implications, I'd certainly recommend looking into this book.

And yes, I've now followed both Norton's podcasts, and her compassion, humour, and victim-focused perspective definitely carry over between those and the book.

#books#booklr#bookblr#book reviews#true crime#non-fiction#memoirs#lay them to rest#laurah norton#read in 2023#my photos

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

anyway blood spatter evidence is scientifically useless as is bite mark evidence. DNA tests have gotten so sensitive as to render DNA evidence effectively useless. polygraphs are legally inadmissible in court in almost all jurisdictions and have no bearing on someone's guilt or innocence. witness statements are usually extremely unreliable. forensic genealogy violates the right to privacy not only for your immediate family but for your ENTIRE FAMILY TREE, living or dead, up to fifth cousins once removed. forensic science is generally pseudoscience in a detective costume and test results are regularly fudged and mischaracterized to achieve a conviction. cops are only ever nice to you for a reason and that reason is usually fucking you over.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mystery of Somerton Man SOLVED after 73 years as DNA finally identifies body

For decades, authorities, academics and the public alike have traded theories about the identity of the mysterious Somerton Man, whose body was found on a beach outside of Adelaide, Australia, on December 1, 1948. He was a Russian spy. A jilted lover poisoned by his paramour. A smuggler!?

The truth, however, is seemingly more mundane. A new DNA analysis suggests the Somerton Man is Carl “Charles” Webb, an electrical engineer from Melbourne who vanished from the public record in April 1947.

Colleen Fitzpatrick, a forensic genealogist who specializes in using DNA to solve cold cases, identified the Somerton Man using hairs caught in his death mask. To narrow down the pool of potential candidates, Fitzpatrick plugged the Somerton man’s DNA into the genealogical research database GEDmatch. After finding a match to a distant cousin, the researchers constructed a family tree of some 4,000 people. They then used archival records to search for individuals whose biographies mirrored what was known about the Somerton Man. Webb, who was born in the Australian state of Victoria in 1905, fit the bill.

On the matter of how he died city coroner said; “There was no indication of violence, and I am compelled to the finding that death resulted from poison, But I cannot say whether it was administered by the deceased himself or by some other person.”

Authorities in Adelaide exhumed the Somerton Man’s body last May and are currently conducting genetic testing on the remains. The last mention of Webb in the historical record dates to April 1947, when he left his wife. In October 1951, three years after the Somerton Man’s death, Dorothy placed a notice in the Age newspaper stating that she had begun divorce proceedings against Webb on the grounds of desertion. By then, Dorothy had moved from Melbourne to Bute, a town 89 miles northeast of Adelaide.

Records showed that Webb enjoyed reading and writing poetry, as well as betting on horse races. He had a sister who lived in Melbourne and was married to a man named Thomas Keane—likely the T. Keane whose name appears on the clothing in the Somerton Man’s suitcase. (As for the American origins of the attire, Abbott speculates that Keane bought the clothing second-hand from a G.I. stationed in Australia.)

Plenty of questions surrounding the case remain: Why did Webb come to Somerton Beach? What was his cause of death? Did he die by suicide? Was he murdered? These answers still remain and being looked into still.

There’s almost a sequel film here, not of ‘who is Somerton man?’, but now it’s ‘the mysterious case of Charles Webb’.”

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

CeCe Moore, an actress and director-turned-genetic genealogist, stood behind a lectern at New Jersey’s Ramapo College in late July. Propelled onto the national stage by the popular PBS show “Finding Your Roots,” Moore was delivering the keynote address for the inaugural conference of forensic genetic genealogists at Ramapo, one of only two institutions of higher education in the U.S. that offer instruction in the field. It was a new era, Moore told the audience, a turning point for solving crime, and they were in on the ground floor. “We’ve created this tool that can accomplish so much,” she said.

Genealogists like Moore hunt for relatives and build family trees just as traditional genealogists do, but with a twist: They work with law enforcement agencies and use commercial DNA databases to search for people who can help them identify unknown human remains or perpetrators who left DNA at a crime scene.

The field exploded in 2018 after the arrest of Joseph James DeAngelo as the notorious Golden State Killer, responsible for more than a dozen murders across California. DNA evidence collected from a 1980 double murder was analyzed and uploaded to a commercial database; a hit to a distant relative helped a genetic genealogist build an elaborate family tree that ultimately coalesced on DeAngelo. Since then, hundreds of cold cases have been solved using the technique. Moore, among the field’s biggest evangelists, boasts of having personally helped close more than 200 cases.

The practice is not without controversy. It involves combing through the genetic information of hundreds of thousands of innocent people in search of a perpetrator. And its practitioners operate without meaningful guardrails, save for “interim” guidance published by the Department of Justice in 2019.

The last five years have been like the “Wild West,” Moore acknowledged, but she was proud to be among the founding members of the Investigative Genetic Genealogy Accreditation Board, which is developing professional standards for practitioners. “With this incredibly powerful tool comes immense responsibility,” she solemnly told the audience. The practice relies on public trust to convince people not only to upload their private genetic information to commercial databases, but also to allow police to rifle through that information. If you’re doing something you wouldn’t want blasted on the front page of the New York Times, Moore said, you should probably rethink what you’re doing. “If we lose public trust, we will lose this tool.”

Despite those words of caution, Moore is one of several high-profile genetic genealogists who exploited a loophole in a commercial database called GEDmatch, allowing them to search the DNA of individuals who explicitly opted out of sharing their genetic information with police.

The loophole, which a source demonstrated for The Intercept, allows genealogists working with police to manipulate search fields within a DNA comparison tool to trick the system into showing opted-out profiles. In records of communications reviewed by The Intercept, Moore and two other forensic genetic genealogists discussed the loophole and how to trigger it. In a separate communication, one of the genealogists described hiding the fact that her organization had made an identification using an opted-out profile.

The communications are a disturbing example of how genetic genealogists and their law enforcement partners, in their zeal to close criminal cases, skirt privacy rules put in place by DNA database companies to protect their customers. How common these practices are remains unknown, in part because police and prosecutors have fought to keep details of genetic investigations from being turned over to criminal defendants. As commercial DNA databases grow, and the use of forensic genetic genealogy as a crime-fighting tool expands, experts say the genetic privacy of millions of Americans is in jeopardy.

Moore did not respond to The Intercept’s requests for comment.

“If we can’t trust these practitioners, we certainly cannot trust law enforcement.”

To Tiffany Roy, a DNA expert and lawyer, the fact that genetic genealogists have accessed private profiles — while simultaneously preaching about ethics — is troubling. “If we can’t trust these practitioners, we certainly cannot trust law enforcement,” she said. “These investigations have serious consequences; they involve people who have never been suspected of a crime.” At the very least, law enforcement actors should have a warrant to conduct a genetic genealogy search, she said. “Anything less is a serious violation of privacy.”

CeCe Moore appears as a guest on “Megyn Kelly Today” on Aug. 14, 2018.

Photo: Zach Pagano/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images

The Wild West

Forensic genetic genealogy evolved from the direct-to-consumer DNA testing craze that took hold roughly a decade ago. Companies like 23andMe and Ancestry offered DNA analysis and a database where results could be uploaded and searched against millions of other profiles, offering consumers a powerful new tool to dig into their heritage through genetics.

It wasn’t long before entrepreneurial genealogists realized this information could also be used to solve criminal cases, especially those that had gone cold. While the arrest of the Golden State Killer captured national attention, it was not the first case solved by forensic genetic genealogy. Two weeks earlier, genetic genealogists Margaret Press and Colleen Fitzpatrick joined officials in Ohio to announce that “groundbreaking work” had allowed authorities to identify a young woman whose body was found by the side of a road back in 1981. Formerly known as “Buckskin Girl” for the handmade pullover she wore, Marcia King was given her name back through genetic genealogy. “Everyone said it couldn’t be done,” Press said.

The type of consumer DNA information used in forensic genetic genealogy is far different from that uploaded to the Combined DNA Index System, or CODIS, a decades-old network administered by the FBI. The DNA entered in CODIS comes from individuals convicted of or arrested for serious crimes and is often referred to as “junk” DNA: short pieces of unique genetic code that don’t carry any individual health or trait information. “It’s not telling us how the person looks. It’s not telling us about their heritage or their phenotypic traits,” Roy said. “It’s a string of numbers, like a telephone number.”

In contrast, the DNA testing offered by direct-to-consumer companies is “as sensitive as it gets,” Roy said. “It tells you about your origins. It tells you about your relatives and your parentage, and it tells you about your disease propensity.” And it has serious reach: While CODIS searches the DNA of people already identified by the criminal justice system, the commercial databases have the potential to search through the DNA of everyone else.

Individuals can upload their test results to any number of databases; at present, there are five main commercial portals. Ancestry and 23andMe are the biggest players in the field, with databases containing roughly 23 million and 14 million profiles. Individuals must test with the companies to gain access to their databases; neither allow DNA results obtained from a different testing service. Both Ancestry and 23andMe forbid police, and the genetic genealogists who work with them, from accessing their data for crime-fighting purposes. “We do not allow law enforcement to use Ancestry’s service to investigate crimes or to identify human remains” absent a valid court order, Ancestry’s privacy policy notes. The two companies provide regular transparency reports documenting law enforcement requests for user information.

MyHeritage, home to some 7 million DNA profiles, similarly bars law enforcement searches, but it does allow individuals to upload DNA results obtained from other sources.

And then there are FamilyTreeDNA and GEDmatch, which grant police access but give users the choice of opting in or out. Both allow anyone to upload their DNA results and have upward of 1.8 million profiles. But neither company routinely publicizes the number of customers who have opted in, said Leah Larkin, a veteran genetic genealogist and privacy advocate from California. Larkin writes about issues in the field — including forensic genetic genealogy, which she does not practice — on her website the DNA Geek. Larkin estimates that roughly 700,000 GEDmatch profiles are opted in. She suspects that even more are opted in on FamilyTreeDNA; opting in is the default for the company’s U.S. customers and “it’s not obvious how to opt out.”

But even opting out of law enforcement searches doesn’t guarantee that a profile won’t be accessed: A loophole in GEDmatch offers users working with law enforcement agencies a back door to accessing protected profiles. A source showed The Intercept how to exploit the loophole; it was not an obvious weakness or one that could be triggered mistakenly. Rather, it was a back door that required experience with the platform’s various tools to open.

GEDmatch’s parent company, Verogen, did not respond to a request for comment.

Law enforcement officials leave the home of accused serial killer Joseph James DeAngelo in Citrus Heights, Calif., on April 24, 2018.

Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

An Open Secret

In forensic genetic genealogy circles, the GEDmatch loophole had long been an open secret, sources told The Intercept, one that finally surfaced publicly during the Ramapo College conference in late July.

Roy, the DNA expert, was giving a presentation titled “In the Hot Seat,” a primer for genealogists on what to expect if called to testify in a criminal case. There was a clear and simple theme: “Do not lie,” Roy said. “The minute you’re caught in a lie is the minute that it’s going to be difficult for people to use your work.”

As part of the session, David Gurney, a professor of law and society at Ramapo and director of the college’s nascent Investigative Genetic Genealogy Center, joined Roy for a mock questioning of Cairenn Binder, a genealogist who heads up the center’s certificate program.

Gurney, simulating direct examination, walked Binder through a series of friendly questions. Did she have access to DNA evidence or genetic code during her investigations? No, she replied. Could she see everyone who’d uploaded DNA to the databases? No, she said, only those who’d opted in to law enforcement searches.

Roy, playing the part of opposing counsel, was pointed in her cross-examination: Was Binder aware of the GEDmatch loophole? And had she used it? Yes, Binder said. “How many times?” Roy asked.

“A handful,” Binder replied. “Maybe up to a dozen.”

Binder’s answers quickly made their way into a private Facebook group for genetic genealogy enthusiasts, prompting a response from the DNA Doe Project, a volunteer-driven organization led by Press, one of the women who identified the Buckskin Girl. Before joining Ramapo College, Binder had worked for the DNA Doe Project.

In a statement posted to the Facebook group, Pam Lauritzen, the project’s communications director, said the loophole was an artifact of changes GEDmatch implemented in 2019, when it made opting out the default for all profiles. “While we knew that the intent of the change was to make opted-out users unavailable, some volunteers with the DNA Doe Project continued to use the reports that allowed access to profiles that were opted out,” she wrote. That use was neither “encouraged nor discouraged,” she continued. Still, she claimed the access was somehow “in compliance” with GEDmatch’s terms of service — which at the time promised that DNA uploaded for law enforcement purposes would only be matched with customers who’d opted in — and that the loophole was closed “years ago.”

It was a curious statement, particularly given that Press, the group’s co-founder, was among the genealogists who discussed the GEDmatch loophole in communications reviewed by The Intercept. In 2020, she described the DNA Doe Project using an opted-out profile to make an identification — and devising a way to keep that quiet.

Press referred The Intercept’s questions to the DNA Doe Project, which declined to comment.

In July 2020, GEDmatch was hacked, which resulted in all 1.45 million profiles then contained in the database to be briefly opted in to law enforcement matching; at the time, BuzzFeed News reported, just 280,000 profiles had opted in. GEDmatch was taken offline “until such time that we can be absolutely sure that user data is protected against potential attacks,” Verogen wrote on Facebook.

In the wake of the hack, a genetic genealogist named Joan Hanlon was asked by Verogen to beta test a new version of the site. According to records of a conversation reviewed by The Intercept, Press and Moore, the featured speaker at the Ramapo conference, discussed with Hanlon their tricks to access opted-out profiles and whether the new website had plugged all backdoor access. It hadn’t. It’s unclear if anyone told Verogen; as of this month, the back door was still open.

Hanlon did not respond to The Intercept’s requests for comment.

In January 2021, GEDmatch changed its terms of service to opt everyone in for searches involving unidentified human remains, making the back door irrelevant for genealogists who only worked on Doe cases, but not those working with authorities to identify perpetrators of violent crimes.

Undisclosed Methods

Exploitation of the GEDmatch loophole isn’t the only example of genetic genealogists and their law enforcement partners playing fast and loose with the rules.

Law enforcement officers have used genetic genealogy to solve crimes that aren’t eligible for genetic investigation per company terms of service and Justice Department guidelines, which say the practice should be reserved for violent crimes like rape and murder only when all other “reasonable” avenues of investigation have failed. In May, CNN reported on a U.S. marshal who used genetic genealogy to solve a decades-old prison break in Nebraska. There is no prison break exception to the eligibility rules, Larkin noted in a post on her website. “This case should never have used forensic genetic genealogy in the first place.”

“This case should never have used forensic genetic genealogy in the first place.”

A month later, Larkin wrote about another violation, this time in a California case. The FBI and the Riverside County Regional Cold Case Homicide Team had identified the victim of a 1996 homicide using the MyHeritage database — an explicit violation of the company’s terms of service, which make clear that using the database for law enforcement purposes is “strictly prohibited” absent a court order.

“The case presents an example of ‘noble cause bias,’” Larkin wrote, “in which the investigators seem to feel that their objective is so worthy that they can break the rules in place to protect others.”

MyHeritage did not respond to a request for comment. The Riverside County Sheriff’s Office referred questions to the Riverside district attorney’s office, which declined to comment on an ongoing investigation. The FBI also declined to comment.

Violations have even come from inside the DNA testing companies. Back in 2019, GEDmatch co-founder Curtis Rogers unilaterally made an exception to the terms of service, without notifying the site’s users, to allow police to search for someone suspected of assault in Utah. It was a tough call, Rogers told BuzzFeed News, but the case in question “was as close to a homicide as you can get.”

It appears that violations have also spread to Ancestry, which prohibits the use of its DNA data for law enforcement purposes unless the company is legally compelled to provide access. Genetic genealogists told The Intercept that they are aware of examples in which genealogists working with police have provided AncestryDNA testing kits to the possible relatives of suspects — what’s known as “target testing” — or asked customers for access to preexisting accounts as a way to unlock the off-limits data.

A spokesperson for Ancestry did not answer The Intercept’s questions about efforts to unlock DNA data for law enforcement purposes via a third party. Instead, in a statement, the company reiterated its commitment to maintaining the privacy of its users. “Protecting our customers’ privacy and being good stewards of their data is Ancestry’s highest priority,” it read. The company did not respond to follow-up questions.

As it turns out, the genetic genealogy work in the Golden State Killer case was also questionable: The break that led to DeAngelo came after genealogist Barbara Rae-Venter uploaded DNA from the double murder to MyHeritage, according to the Los Angeles Times. Rae-Venter told the Times that she didn’t notify the company about what she was doing but that her actions were approved by Steve Kramer, the FBI’s Los Angeles division counsel at the time. “In his opinion, law enforcement is entitled to go where the public goes,” Rae-Venter told the paper.

Just how prevalent these practices are may never fully be known, in part because police and prosecutors regularly seek to shield genetic investigations from being vetted in court. They argue that what they obtain from forensic genetic genealogy is merely a tip, like information provided by an informant, and is exempt from disclosure to criminal defendants.

That’s exactly what’s happening in Idaho, where Bryan Kohberger is awaiting trial for the 2022 murder of four university students. For months, the state failed to disclose that it had used forensic genetic genealogy to identify Kohberger as a suspect. A probable cause statement methodically laying out the evidence that led cops to his door conspicuously omitted any mention of genetic genealogy. Kohberger’s defense team has asked to see documents related to the genealogy work as it prepares for an October trial, but the state has refused, saying the defense has no right to any information about the genetic genealogy it used to crack the case.

Prosecutors said it was the FBI that did the genetic genealogy work, and few records were created in the process, leaving little to turn over. But the state also argued that it couldn’t turn over information because the family tree the FBI created was extensive — including “the names and personal information of … hundreds of innocent relatives” — and the privacy of those individuals needed to be maintained. According to the state, it shouldn’t even have to say which genetic database — or databases — it used.

Kohberger’s attorneys argue that the state’s position is preposterous and keeps them from ensuring that the work undertaken to find Kohberger was above board. “It would appear that the state is acknowledging that the companies are providing personal information to the state and that those companies and the government would suffer if the public were to realize it,” one of Kohberger’s attorneys wrote. “The statement by the government implies that the databases searched may be ones that law enforcement is specifically barred from, which explains why they do not want to disclose their methods.”

A hearing on the issue is scheduled for August 18.

An AncestryDNA user points to his family tree on Ancestry.com on June 24, 2016.

Photo: RJ Sangosti/The Denver Post via Getty Images

“A Search of All of Us”

Natalie Ram, a law professor at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law and an expert in genetic privacy, believes forensic genetic genealogy is a giant fishing expedition that fails the particularity requirement of the Fourth Amendment: that law enforcement searches be targeted and based on individualized suspicion. Finding a match to crime scene DNA by searching through millions of genetic profiles is the opposite of targeted. Forensic genetic genealogy, according to Ram, “is fundamentally a search of all of us every time they do it.”

While proponents of forensic genetic genealogy say the individuals they’re searching have willingly uploaded their genetic information and opted in to law enforcement access, Ram and others aren’t so sure that’s the case, even when practitioners adhere to terms of service. If the consent is truly informed and voluntary, “then I think that it would be ethical, lawful, permissible for law enforcement to use that DNA … to identify those individuals who did the volunteering,” Ram said. But that’s not who is being identified in these cases. Instead, it’s relatives — and sometimes very distant relatives. “Our genetic associations are involuntary. They’re profoundly involuntary. They’re involuntary in a way that almost nothing else is. And they’re also immutable,” she said. “I can estrange myself from my family and my siblings and deprive them of information about what I’m doing in my life. And yet their DNA is informative on me.”

Jennifer Lynch, general counsel at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, agrees. “We’re putting other people’s privacy on the line when we’re trying to upload our own genetic information,” she said. “You can’t consent for another person. And there’s just not an argument that you have consented for your genetic information to be in a database when it’s your brother who’s uploaded the information, or when it’s somebody you don’t even know who is related to you.”

To date, efforts to rein in the practice as a violation of the Fourth Amendment have presented some problems. A person whose arrest was built on a foundation of genetic genealogy, for example, might have been harmed by the genealogical fishing expedition but lack standing to bring a case; in the strictest sense, it wasn’t their DNA that was searched. In contrast, a third cousin whose DNA was used to identify a suspect could have standing to bring a suit, but they might be hard-pressed to prove they were harmed by the search.

If police are getting hits to suspects by violating companies’ terms of service — using databases that bar police searching — that “raises some serious Fourth Amendment questions” because no expectation of privacy has been waived, Ram said. Of course, ferreting out such violations would require that the information be disclosed in court, which isn’t happening.

At present, the only real regulators of the practice are the database owners: private companies that can change hands or terms of service with little notice. GEDmatch, which has at least once bent its terms to accommodate police, was started by two genealogy hobbyists and then sold to the biotech company Verogen, which in turn was acquired last winter by another biotech company, Qiagen. Experts like Ram and Lynch worry about the implications of so much sensitive information held in for-profit hands — and readily exploited by police. The “platforms right now are the most powerful regulators we have for most Americans,” Ram said. Police regulate “after a fashion, in a fashion, by what they do. They tell us what they’re willing to do by what they actually do,” she added. “But by the way, that’s like law enforcement making rules for itself, so not exactly a diverse group of stakeholders.”

For now, Ram said, the best way to regulate forensic genetic genealogy is by statute. In 2021, Maryland lawmakers passed a comprehensive law to restrain the practice. It requires police to obtain a warrant before conducting a genetic genealogy search — certifying that the case is an eligible violent felony and that all other reasonable avenues of investigation have failed — and notify the court before gathering DNA evidence to confirm the suspect identified via genetic genealogy is, in fact, the likely perpetrator. Currently, police use surreptitious methods to collect DNA without judicial oversight: mining a person’s garbage, for example, for items expected to contain biological evidence. In the Golden State Killer case, DeAngelo was implicated by DNA on a discarded tissue.

The Maryland law also requires police to obtain consent from any third party whose DNA might help solve a crime. In the Kohberger case, police searched his parents’ garbage, collecting trash with DNA on it that the lab believed belonged to Kohberger’s father. In a notorious Florida case, police lied to a suspect’s parents to get a DNA sample from the mother, telling her they were trying to identify a person found dead whom they believed was her relative. Those methods are barred under the Maryland law.

Montana and Utah have also passed laws governing forensic genetic genealogy, though neither is as strict as Maryland’s.

MyHeritage DNA kits are displayed at the RootsTech conference in Salt Lake City on Feb. 9, 2017.

Photo: George Frey/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Solving Crime Before It Happens

The rise of direct-to-consumer DNA testing and forensic genetic genealogy raises another issue: the looming reality of a de facto national DNA database that can identify large swaths of the U.S. population, regardless of whether those individuals have uploaded their genetic information. In 2018, researchers led by the former chief science officer at MyHeritage predicted that a database of roughly 3 million people could identify nearly 100 percent of U.S. citizens of European descent. “Such a database scale is foreseeable for some third-party websites in the near future,” they concluded.

“All of a sudden, we have a national DNA database, and we didn’t ever have any kind of debate about whether we wanted that in our society.”

“All of a sudden, we have a national DNA database,” said Lynch, “and we didn’t ever have any kind of debate about whether we wanted that in our society.” A national database in “private hands,” she added.

By the time people started worrying about this as a policy issue, it was “too late,” Moore said during her address at the Ramapo conference. “By the time the vast majority of the public learned about genetic genealogy, we’d been quietly building this incredibly powerful tool for human identification behind the scenes,” she said. “People sort of laughed, like, ‘Oh, hobbyists … you do your genealogy, you do your adoption,’ and we were allowed to build this tool without interference.”

Moore advocated for involving forensic genetic genealogy earlier in the investigative process. Doing so, she argued, could focus police on guilty parties more quickly and save innocent people from needless law enforcement scrutiny. In fact, she told the audience, she believes that forensic genetic genealogy can help to eradicate crime. “We can stop criminals in their tracks,” she said. “I really believe we can stop serial killers from existing, stop serial rapists from existing.”

“We are an army. We can do this! So repeat after me,” Moore said, before leading the audience in a chant. “No more serial killers!”

Update: August 18, 2023, 3:55 p.m. ET

After this article was published, Margaret Press, founder of the DNA Doe Project, released a statement in response to The Intercept’s findings. Press acknowledged that between May 2019 and January 2021, the organization’s leadership and volunteers made use of GEDmatch tools that provided access to DNA profiles that were opted out of law enforcement searches, which she described as “a bug in the software.” Press stated:

We have always been committed to abide by the Terms of Service for the databases we used, and take our responsibility to our law enforcement and medical examiner partner agencies extremely seriously. In hindsight, it’s clear we failed to consider the critically important need for the public to be able to trust that their DNA data will only be shared and used with their permission and under the restrictions they choose. We should have reported these bugs to GEDmatch and stopped using the affected reports until the bugs were fixed. Instead, on that first day when we found that all of the profiles were set to opt-out, I discouraged our team from reporting them at all. I now know I was wrong and I regret my words and actions.

#Police Are Getting DNA Data From People Who Think They Opted Out#stolen dna#end qualified immunity#thugs with badges and guns#stealing dna with a badge and gun

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forensic Science E-Magazine (Aug-Sept 2023)

We proudly present the Aug-Sept issue (Vol 17) of your favorite magazine, Forensic Science E-Magazine. As usual, the magazine's current issue has helpful content related to forensic science.

---------

#forensicsciencemagazine #forensicfield #crimescene

Continue reading Untitled

View On WordPress

#Ancient DNA: how do you extract it?#Areas Of Competence For Specialists In Forensic Medicine#forensic field magazine#forensic magazine#Forensic science#forensic science magazine#Gunpowder#Kempamma – The Cyanide Queen#List Of Materials Commonly Collected for DNA Analysis#magazine#magazine of forensic#Postmortem Lividity Discoloration#Rifled Injuries#Technology in Questioned Document Examination#Uses Of Different Types Of Chromatography In Forensic Science. Unlocking the Past: The power of Forensic Genealogy in Modern Crime Solving

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

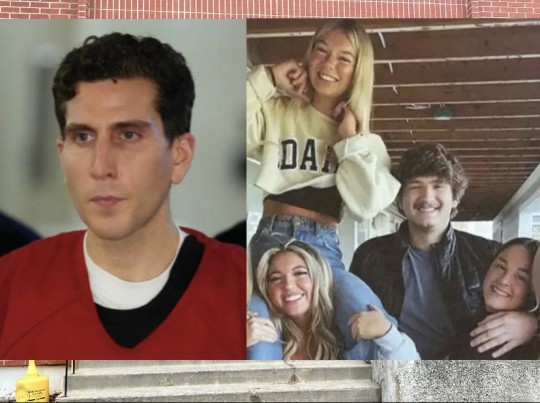

The Idaho murders: what we know so far

SAN ANTONIO – On Nov. 13, 2022 in Moscow, Idaho, at around 11:58 a.m., a 9-1-1 call was made to the Moscow Police Department for an “unconscious person.”

Bryan Kohberger, the suspect in Idaho’s quadruple homicide case, is being held at Latah County jail awaiting trial after being charged with four counts of first-degree murder and one count of felony burglary.

Officers would then encounter a gruesome scene consisting of the lifeless bodies of four University of Idaho students who reportedly suffered multiple stab wounds.

Right to left, Madison Mogen, 21, Kaylee Goncalves, 21, Ethan Chapin, 20, and Xana Kernodle, 20.

The stuents were, Madison Mogen, 21, Kaylee Goncalves, 21, Ethan Chapin, 20, and Xana Kernodle, 20.

More than six weeks after the incident, on Dec. 30, police arrested Bryan Kohberger, a 28-year-old criminology Ph.D. student at Washington State University.

Since then, court documents and an 18-page affidavit consisting of evidence against Kohberger have been released, and the case is still unfolding.

Police said Chapin and his girlfriend, Kernodle, were seen at a fraternity party at the Sigma Chi House the same night.

At 1:40 a.m., Goncalves and Mogen were seen on surveillance footage at a food truck, later arriving home at 1:45 a.m., the same time both Chapin and Kernodle returned to the residence.

According to court documents, the murders took place between 4 a.m. and 4:25 a.m.

The off-campus residence on King Road had no signs of forced entry, an unlocked door and the two surviving roommates who were at the home during the murders were unharmed, according to the authorities.

In the affidavit, a “tan leather knife sheath” was found on the bed next to Mogen’s right side.

After the sheath was processed, the Idaho State Lab located a single source of male DNA that was then traced back to the suspect through genetic genealogy.

A security camera would then pick up four sightings of a 2011 - 2013 white Hyundai Elantra circling around the home, then driving off after the murders had occurred.

Investigators also recovered a latent shoe print processed by the ISP Forensic Team.

The FBI tracked Kohberger from Washington and Pennsylvania and requested that the Indiana cops perform a routine traffic stop so that they could capture footage or photos of his hands.

According to NBC, Kohberger was pulled over twice, and TMZ had released footage of one of the first traffic stops.

Kohberger was arrested Dec. 30 at his parents’ home in Effort, Pennsylvania. Monroe County, and authorities seized the car of the same make and model like that of the white Hyundai Elantra.

Pennsylvania Public Defender Jason LaBar told CNN that Kohberger was "shocked a little bit" by the accusations.

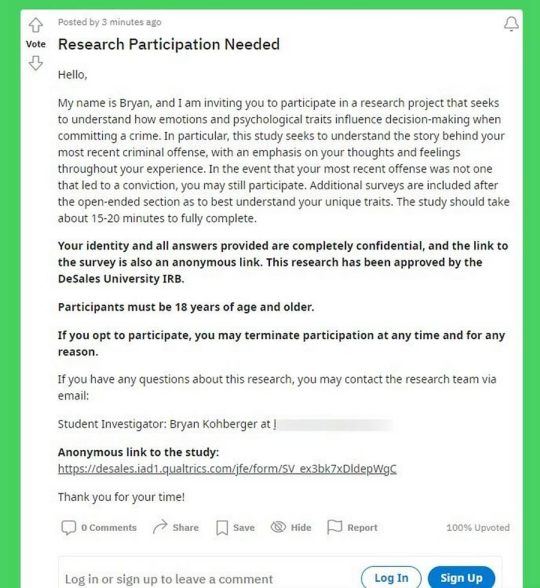

DeSales University confirmed that Kohberger had received a masters degree in Criminal Justice.

According to one of his DeSales classmates, Kohberger had a massive interest in serial killers and true crime and was passionate about theorizing why and how crimes took place.

Kohberger was not only a graduate student, but he was also a teacher assistant who helped teach students about criminal justice and criminology.

Reddit survey post made by Bryan Kohberger a while before the murders had occurred.

Kohberger allegedly even sent out a survey before the murders, to a select group of people asking questions about committing a crime.

One of the questions in the survey was “why did you choose that victim or target over others?” Kohberger wrote.

Our Lady of The Lake University (OLLU) student Julissa Casas has been following the case through social media since January, and said that hearing all the details slowly come out had been a crazy experience.

Casas lives in the Lakeview apartments on campus.

The apartments were made to create more residences for those who do not commute to the university, and it can be said that the Lakeview apartments are similar to the King road residence that the victims had lived in near the University of Idaho.

“The story made me even more scared and hyper aware of my surroundings,” Casas said.

Although she’s taken her own appropriate safety precautions, such as sharing her location with her parents via Life 360, with some of her close friends, and pepper spray, she still feels that since the Idaho murders, it could happen to anyone.

“I used to feel safe, but now It’s now engraved in my brain,” Casas said.

Casas also said that she does not feel safe walking alone, but safer walking with a group of friends.

“It’s terrifying knowing that there are people that find joy in hurting others. It’s terrifying knowing that he was a Criminal Justice grad student teaching other young students about the science behind committing these violent crimes,” Casas said.

Casas’ dream job used to be becoming an FBI Behavioral Analyst and said that after knowing many cases, this case has been one of the most terrifying to see unravel because of the gruesomeness of it.

“It is so sad to know that Kaylee [Goncalves] was spending one last night in the house she loved with her best friends before she moved to Texas the next day to start her new job,” Casas said.

Casas prays for the victims’ families everyday, and for Kohbergers’ as-well.

“They had no idea what a monster he was, and now have to deal with the repercussions of what their child has done for the rest of their lives” Casas said.

Kohberger waived his extradition in March and has denied the allegations on four counts of murder and one count of burglary.

Investigators believe Kohberger broke in "with the intent to commit murder," Bill Thompson, a prosecutor in Latah County, Idaho, said during a press conference in January.

LaBar, the Chief Public Defender of Monroe County, Pennsylvania represented Kohberger in his extradition, but will not be his defender in the murder case.

According to Today, on Jan. 3, LaBar stated that his client believes he will be exonerated.

“Mr. Kohberger is eager to be exonerated of these charges and looks forward to resolving these matters as promptly as possible,” LaBar said.

As each day passes, more details continue to come out.

As of Feb. 20th, what is known and confirmed by sources is that Kernodle and Chapin were found by Chapins best friend, surviving roommate Dylan Mortenson was the one who made the 9-1-1 call, and an unidentified friend of the four victims checked their pulses’ before calling.

Kohbergers attorney, Anne Taylor, asked to delay her clients’ preliminary hearing, and is now expected to attend trial June 26. At 9 a.m.

Judge Megan Marshall expects the trial to last for five days.

Until then, Kohberger remains in Latah County Jail in Idaho held without bond, and has not yet entered a plea.

Feb.20.2023

#article#articles#mywriting#mywork#idahomurders#journalist#journalism#student#truecrime#moscow idaho#truecrimecommunity

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Breakthrough in Cold Case: DNA from Cigarette Butts Leads to Arrest in 2003 Homicide

Hamilton County Prosecutor Melissa Powers made a groundbreaking announcement on October 2, 2023, regarding the indictment of Robert Stewart for the murder of Herman Brown back in 2003.

Background:Robert Stewart, born on March 28, 1959, now faces two counts of murder and one count of felonious assault, carrying the potential of a life sentence if convicted.

The case dates back to February 15,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

After an exhumation of "The Boy in the Box" in 2019, police have apparently identified him around 65 years later. It's been reported that the name will be released soon, but it hasn't as of yet.

This is... Amazing. Forensic cases like this - solved YEARS after they happened - are why I'm getting into this field. This little boy died unknown and abandoned, becoming a famously unsolved case, and can now hopefully find peace.

Some sources have even claimed that criminal charges may still be filed.

Forensic genealogy is incredible.

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/philadelphia-boy-in-box-identified-b2238086.html

https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/us-news/boy-box-victim-mystery-murder-28632926

#TW: murder#TW: crime#stuff like this makes me so emotional#you'll get your name back soon sweetheart#Caitlin rambles

6 notes

·

View notes