#hernan cortes

Text

Mysterious skeleton found in Hernán Cortés' palace revealed to be Indigenous woman, not Spanish monk

A skeleton visible within a burial at the entrance of the palace of Hernán Cortés —the Spanish conquistador who caused the fall of the Aztec Empire — is not the remains of a Spanish monk as was long thought. Instead, a new analysis reveals that the bones belonged to a middle-aged Indigenous woman.

When a powerful magnitude 7.1 earthquake rattled the Mexican states of Puebla and Morelos as well as Mexico City in 2017, buildings collapsed and thousands of people were injured. The Palace of Cortés, which was built by 1535 and now serves as a museum, was severely damaged, requiring extensive repair work that was completed in early 2023. During this work, researchers took stock of all objects within the museum, including an open burial exhibited at the entrance to the palace. Read more.

377 notes

·

View notes

Text

#hernán cortés#hernan cortes#cortes#conquistador#conquistadors#conquest#spain#spanish#art#aztec empire#aztec#aztecs#americas#history#europe#european#armour#knights#knight#warriors#cortés#mexico#explorers#exploration#tlascalan#horses#america#age of discovery#age of exploration#new world

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1520, Spanish conquistadors lost 8 tons of gold as they fled the Aztec capital. Known as Montezuma’s Treasure, fortune hunters have been looking for it ever since.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The conquistadors are too “pagan” for the Church and most Christians to accept — they wanted glory, power, wealth, dominion over space. At the same time, they were too deeply Catholic to be picked up by neopagans, and too White for progressives. They exist in a strange limbo".

- Alaric the Barbarian, The Dissident Review.

#conquistadores#age of exploration#explorers#europe#european expansion#spaniards#spain#conquista#paganism#catholiscism#extremadura#Castile#traditions#traditionalism#european values#columbus#pizarro#hernan cortes#visigoths#germanism#castilla#church

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finished Fifth Sun by Camilla Townsend and wanted to check out the reviews on Goodreads to see what other people thought of it. There I encountered this white supremacist and homophobic garbage of a reviewer who has his head shoved so far up Hernan Cortes's arse I'm surprised he can read in the dark.

Dude, no one is saying the ancient Mexica were perfect angels, but stop uwuing Hernan like he did no wrong.

The biggest hilarity in his review (to me, anyway) is where he says the section on homosexuality can't be true because wikipedia says the Aztecs tortured homosexuals. If you check that particular citation, the source is from the Spanish, who were actually the ones torturing who they considered "deviants." The source in Camilla Townsend's book is from the writings of Indigenous peoples displaced by the Spanish.

But sure, dude. A culture that had two whole gods of homosexuality* tortured gay people, sure.

*Huēhuecoyōtl and Xōchipilli

Serves me right for reading Goodreads I guess.

11 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Nahuatl Language

The Aztec Empire fell to Hernán Cortés and the Spanish invaders by 1521, leading to its sharp decline and subjugation to Spanish rule. Although the conquest physically occurred hundreds of years ago, it continues on a different front today—in modern-day Mexico, Spanish, the language of the civilization’s conquerors, is effacing Nahuatl, once the language of the Aztecs. Though many English speakers may know little of Nahuatl, many use words each day that originally stem from it, for example, “chocolate,” “avocado,” and “tomato”—an infinitesimally small example of the value that the culture and language have brought to the world. Unfortunately, the language and identity of Nahuatl speakers is endangered by a lasting discrimination that is damaging on human, linguistic, and cultural levels.

Decline of Nahuatl

Despite currently being spoken by over one million people in Mexico, Nahuatl is still very much on the decline. Several factors have contributed to this decline, which has its roots in the colonization and oppression of indigenous peoples. After 1821, following the Mexican Revolution, indigenous groups were minimized, seen as getting in the way of progress. Leaders desired to form a Mexican identity that included both European and Aztec roots, all the while denigrating indigenous peoples. The discrepancy in education was already evident, with Mexican education following the principle of “direct teaching,” meaning that, regardless of one’s native language, school was taught in Spanish. For most of the 1900s in a time known as the Indigenismo period, the main intent of bilingual education was not to preserve indigenous languages, or even to establish competency in Spanish without abandoning one’s native language, but instead to assimilate native peoples at the cost of their own languages and cultures.

Over time, bilingual education in Mexico experienced some improvements. Some factors in that improvement included pressure from the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN), a guerrilla organization in support of indigenous peoples, and the international community increasingly frowning upon assimilation. However, in modern Mexican society, indigenous peoples are still subjected to prejudice and unequal opportunities that make the preservation of languages like Nahuatl more difficult.

The challenges of passing on the language within Nahuatl-speaking communities have also contributed to its decline, continually leading to fewer speakers. Spelling is not always standardized, literature in the language is hard to come by, and the resources that do exist are often to facilitate switching to and promoting Spanish, rather than protecting Nahuatl.

Challenges to Bilingual Education

Nahuatl bilingual education faces several challenges, which can also contribute to the decline of the language. Firstly, beliefs in the superiority of the Spanish language and culture stemming from a long history of discrimination can be damaging to the desire to spread or even just maintain the language. An example is diminishing Nahuatl by calling it a “dialecto” instead of a language in its own right. In reality, considering languages to hold a superior or inferior status in relation to one another has no linguistic basis. Spanish and Nahuatl are instead quite distinct and members of two completely separate language families, the former Indo-European and the latter Uto-Aztecan. In addition, to those who do not speak Nahuatl, the language possesses characteristics that may seem unfamiliar and complicated. For example, it is an agglutinating language, conveying a good deal of meaning in one word by adding to that word; “I am a woman” is “nicihuatl” in Nahuatl. Since many Mexicans are mestizos, or mixed-race, speaking an indigenous language is often used as a discriminatory factor; this distinction based on language is purely societal, and is not supported linguistically.

Furthermore, in some cases, indigenous people may not even want to participate in bilingual education, again often because of the negative associations society has placed upon indigenous languages. Often education has been premised on the idea that students are held back by their native language and way of life, adding to this perception. Maintaining indigenous languages also may not seem useful to those in the community; as Mexico’s majority language, Spanish is the most practical language for work.

Other challenges include finding a way to avoid possible detrimental impacts to the indigenous communities in question, while still providing sufficient education. For example, students might end up less connected and involved in their cultures due to the amount of time spent in the school. Of course, similar fears exist outside of educational situations: constant exposure to the Spanish language has also resulted in some change to Nahuatl, both in vocabulary and structure, to more closely resemble Spanish. Although changes resulting from language contact are natural —this language mixing can breed resentment and a sense of loss of identity, due to the respective status of the language in society.

Efforts in Bilingual Education and Language Preservation

Providing education that incorporates Nahuatl to those that speak the language is absolutely crucial not only to general linguistic preservation, but also to the individual learner and each community. A significant factor in the disparity of illiteracy of indigenous communities is the lack of availability of quality education in indigenous languages.

Initiatives have been put in place within Mexico to support indigenous languages and improve education in indigenous communities. One example is the National Institute of Indigenous Languages (INALI); created in 2003, the organization seeks to advocate for indigenous languages. One of its recent services is providing information on its website about the ongoing coronavirus pandemic in several indigenous languages, including Nahuatl. However, more widespread work remains to be done in targeting issues such as improving education in indigenous languages, and the issue of standardized tests requiring good knowledge of Spanish, which can be exclusionary.

Another example is the Bilingual Literacy for Life Programme/MEVyT (Modelo Educación para la Vida y el Trabajo) Indígena Bilingüe (BLLP/MIB). The purpose of this initiative is to increase literacy in both Spanish and indigenous languages, teach useful skills, and encourage viewing one’s culture as valuable. The initiative does suffer from lack of funding, and some potential students have no desire to join as Spanish is more useful for finding work. And involving Nahuatl specifically, at the Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, students who speak it can participate directly in the preservation of their language, for example in helping make a dictionary of the language.

Moving Forward

What poses the most danger to the Nahuatl language and the culture of those who speak it—what most thoroughly undermines the most genuine and dedicated efforts in bilingual education—is the pervasive prejudice that seeks to ingrain beliefs that the cultures and languages of indigenous peoples are inferior, not worth maintaining or appreciating, but best replaced by the way of life of the majority. The decline of Nahuatl is the slow destruction of a culture and history stretching back hundreds of years, a forced loss engineered by a history of colonialism and discrimination that remains today.

#🇲🇽#indigenous#native#mexico#nahua#nahuatl#colonization#aztec#colonialism#imperialism#history#mexican history#europe#spain#hernan cortes#spanish#english#usa#united states#mexican revolution#Zapatista Army of National Liberation#EZLN#racism#National Institute of Indigenous Languages#INALI#coronavirus#covid-19#Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

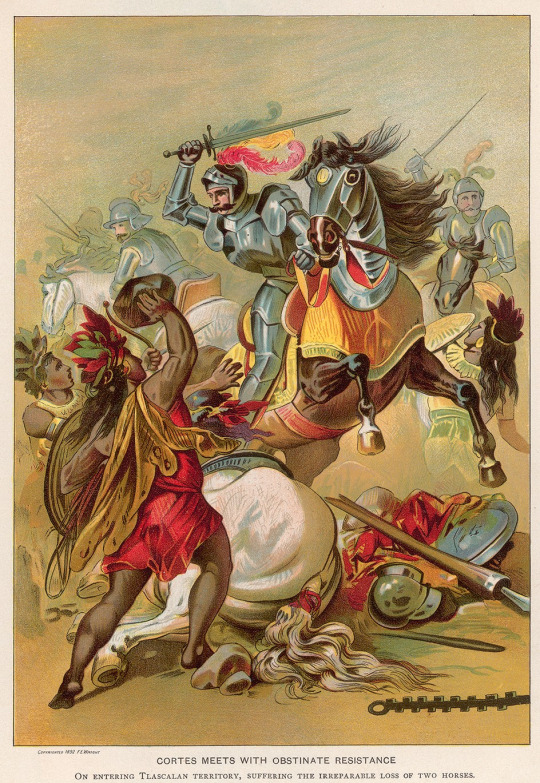

El día 7 de julio de 1520 tuvo lugar la que tal vez fue la batalla más importante de toda la conquista española.Ese día, los restos del ejercito de Cortés, con poco más de 500 soldados europeos, 16 caballos y cerca de 4000 indígenas tlaxcaltecas, fueron interceptados por el grueso del ejército mexica.

Hernán Cortés y sus tropas venían huyendo de Tenochtitlán, donde habían pasado por lo que conocemos como la Noche Triste, y buscaba rodear el sistema de lagos de la cuenca para llegar a Tlaxcala y poder reorganizarse.

Por su parte, los mexicas venían a marchas forzadas desde lo que hoy es Morelos, su ejército era de al menos 20,000 hombres, para el imperio azteca era ganar o morir.

El encuentro se dio en los alrededores de lo que hoy es Otumba en el Estado de México, y el resultado fue una derrota terrible para los mexicas.

Los guerreros aztecas tenían prácticamente la victoria asegurada, habían rodeado los invasores y los estaban separando en pequeños grupos para eliminarlos.

Cortés valientemente y en solitario, hábilmente dirigió el ataque con el resto de su caballería al líder de los mexicas, lo mataron y tomaron su estandarte y a partir de este momento, y de acuerdo a las costumbres y forma de ver la guerra, para sorpresa de los conquistadores, aún con la ventaja estratégica, los soldados mexicas abandonaron el campo de batalla.

Seguramente el proceso de conquista, por la diferencia en tecnología y recursos era inevitable, pero si hubieran sido derrotados los europeos en esta batalla, el proceso hubiera sido mucho más largo.

El sitio de la gran Tenochtitlán, debido a la viruela traída por el invasor, se convirtió en una guerra total de desgaste, donde los guerreros mexicas dieron prueba de valor, pero al final, como ellos lo interpretaron fueron abandonados por sus dioses, pero en realidad el imperio azteca no tenía ninguna posibilidad de victoria.

Atrás quedaba el imperio azteca, con sus luces muy brillantes y sombras muy oscuras, iniciaba una nueva época, y con el mestizaje nació lo que hoy conocemos como México, resultado de los dos más grandes imperios de esos continentes.

#hernan cortes#nuevo mundo#aztecas#mexicas#mexico#conquista#españa#imperio#tenochtitlán#historia#sobre la marcha#guerreros

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

501st anniversary of the fall of Tenochtitlan and the surrender of Cuauhtémoc, last independent ruler of the Mexica, to Cortés and the Tlaxcaltecas.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

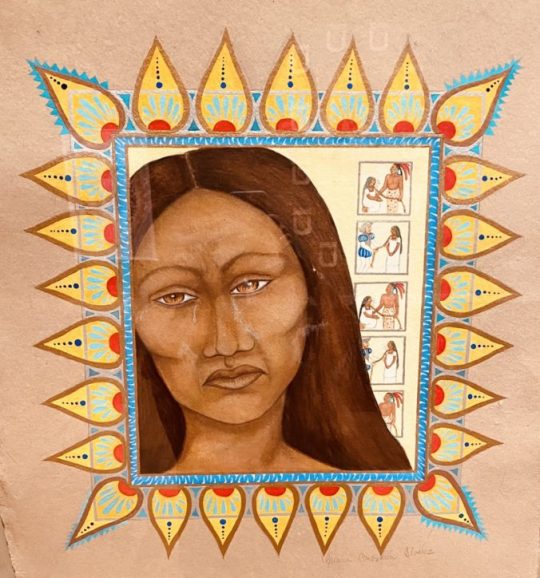

La Malinche: Mexico's Mestizo Origins

La Malinche: Mexico’s Mestizo Origins

For those who don’t know, La Malinche was the young woman-child and slave sold to Hernan Cortes on the Maya coast of Mexico in 1521. She was traded by the Chontal Maya along with 19 other 12-year olds. Her narrative is complex and formidable. An exhibit at the Albuquerque Museum examines her role as survivor, interpretor, and companion. In viewing the exhibit and knowing of her story, I continue…

View On WordPress

#Albuquerque Museum#Dance of the Feather#Dance of the Matachines#Doña Marina#feminism#Hernan Cortes#La Malinche#Mexico#New Mexico#Oaxaca#Spanish conquest#violence against women

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Triple Alliance: An Empire of Obsidian and Blood

"They make a desert and call it peace." -Calgacus

When the Spanish arrived on the shores of what today is Veracruz, they heard rumors of a great capital city of gold, full of fearsome warriors that required victims for the bloody altars of their hungry gods. History has come to call this polity that ruled much of what today is Mexico the Triple Alliance. What was the structure of this empire? How did it rule and what did it value? Can we even call it an empire at all?

As is often the case in history, the rise of a new, great power requires the fall of an older power. Before the rise of the Mexica and their city of Tenochtitlan, the dominating political force was a city called Azcapotzalco. As the great regional power, Azcapotzalco in effect ruled the valley, and demanded tribute and fealty from the other city-states in the area. After years of wandering and working as hired soldiers for more established nations, the Mexica had founded their city Tenochtitlan on an island in Lake Texcoco. Tenochtitlan was still a relatively new city, seeking more to stay safe rather than to dominate. Persuaded to align with a more established city-state, Texcoco, and another nearby kingdom, Tlacopan, Tenochtitlan and the others rose to fight a war to overthrow Azcapotzalco as the hegemon of the Valley of Mexico. It was a great gamble, because to lose would mean at best enslavement and at worst annihilation. Politics in ancient Mesoamerica was never a gentle sport. But the Three T's won, overthrew Azcapotzalco, and became the great power in the region the Spanish would encounter when they arrived by boat from Cuba in 1519.

In her excellent book, Fifth Sun, Camilla Townsend writes a new account of the history of the Mexica people (Aztecs). The great question is: How exactly did the Triple Alliance of these three Nahuatl kingdoms work? Was it even an empire by our Western definition? Townsend does a better job explaining it than I ever could, so I will quote her in full:

"The kings of Tenochtitlan (of the Mexica people), Texocco (of the Acolhua people), and Tlacopan (Of the Tepanec people) now ruled the valley as an unofficial triumvirate. There was no formal statement to that effect. Later generations would say they intiated a Triple Alliance, even though in a literal sense there was no institution. In a de facto sense, however, there most certainly was what we might call a lowercase triple alliance. No one moved in the central valley without at least one of these three kings being aware of it, and beyond the mountains that surrounded them, in the lands they gradually conquered, they had many eyes. They worked together to bring down their enemies; they divided the resulting tribute payments judiciously between them. The Mexica, with the largest population and having played the most important role in the war, got the largest share, but they were careful not to engeder resentment among their closest allies by taking too much (46)."

Conquered towns and cities were allowed to maintain some level of local self-government, as long as they paid tribute, and sent able bodied men to participate in public works, such as building roads or great temples. Many empires often seek to impose their culture, language, or religion on people assimilated into their empire (there is a reason much of Europe speaks Latin-based languages today). Was the Triple Alliance interested in "civilizing" or changing its conquered people, like the Spanish Empire that would in turn conquer them? Not so, Townsend writes:

"'This was no Rome,' one historian has commented succinctly, meaning that the Mexica had no interest in acculturating those they conquered, no desire to teach them their language, or to draw them into their capital or military hierarchy (47)."

In this sense, we could say the Triple Alliance were more like the Mongols, accepting of other gods, languages, and ways of life, as long as their overarching soverignty was acknowledged and their taxes paid. Like all successful empires, the Triple Alliance recognized good ideas when they encountered them, culturally borrowing (or stealing) ideas and practices from their neighbors and conquered peoples. The Mexica were in awe of the Olmecs and Toltecs and other long past civilizations of the region, and incorporated their religion and arcitecture. The Mexica considered the Maya to the south to be a political and cultural force in decline. But the Mexica admired the accomplishments made during their Golden Age and borrowed their writing system and based their calendar on Maya astronomy. Like the Romans, the Triple Alliance would wipe out rebellious towns and "call it peace", but they would rather these people be alive, paying taxes, and worshipping whatever gods they wished.

In fact, it was in part this relatively loose empirical arrangement that allowed the Spanish to conquer the Triple Alliance and siege Tenochtitlan. The Spanish were able to back a different rival prince for the throne of Texoco, Ixtlilxochitl, and divided the Triple Alliance against its self. Monster though he was, Hernán Cortés knew how to play different groups against each other for his own benefit.

#triple alliance#mexican history#historia mexicana#tenochitlan#La Triple Alianza#Hernan Cortes#Hernán Cortés#empire#history of empire#roman empire#romanempire#Mongols#Mongol Empire

0 notes

Text

The Mexica people of the Aztec Empire did not mistake Hernán Cortés and his landing party for gods during Cortés' conquest of the empire. This myth came from Francisco López de Gómara, who never went to Mexico and concocted the myth while working for the retired Cortés in Spain years after the conquest.[288]

1 note

·

View note

Text

La unica razon por la que Mexico existe porque Cortes accidentalmente le dio viruela al imperio azteca entero y eso es muy gracioso

0 notes

Photo

Para los que os gusta leer en PDF ya está disponible mi nuevo libro La Historia Verdadera de los Hijos del Sol en este enlace: https://chicosanchez.com/libros/ols/products/xn--la-historia-verdadera-de-los-hijos-del-sol-de-chico-snchez-bzexn---versin-digital-pdf-rcc Los libros en papel estarán pronto también a la venta y os pasaré los enlaces. Si te gustaron los anteriores te aseguro que este los supera a todos. Gracias por compartir.

#libros #chicosanchez #historia #fotografía #viajes #mitología

#libros#guadalupe#religión#mexico#españa#guatemala#belice#roma#historia#antropología#mitologia#mayas#mexicas#conquista#hernan cortes#bernal diaz del castillo#chico sanchez#atlantida#babilonia#pueblos antiguos#quetzalcóatl#kukulkan#ehecatl

1 note

·

View note

Text

In a strange twist of history being revised, a burial at Palacio de Cortés in Mexico has been relabeled as an indigenous Aztec woman, having been denoted a Spanish monk for 50 years!

For decades, visitors to the Palacio de Cortés glimpsed a mysterious burial through an archaeological window, believed to be that of a Spanish monk. But recent research has just turned this story on its head.

A meticulous study by the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) has revealed that the skeleton is actually that of a Tlahuica woman, an Aztec tribe native to the region. This revelation comes post the restructuring of the palace following the 2017 earthquake.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The armor, the pikes, the Toledo steel blades, the discipline and know-how from decades of fighting the Moor [...]. And above all, bravery and daring [...]. Once conquests were made, he never stopped".

-BAP on Pedro de Alvarado.

#Pedro de Alvarado#Alvarado#hernan cortes#pizarro#age of exploration#conquistadors#Spaniards#frontier#wild west#conquest#Europeans#Europe#moors#mayans#aztecs#toledo steel#castile#castilians

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Video Resources of the Indigenous People of Pre-Hispanic Mexico

When viewing my tumblr blog the first thing people see is my pinned post which has resources and information people can read concerning the indigenous people of what would become Mexico.

This post will do the same, but like the title says you’ll be able to watch videos with information rather than having to read about it. And just like my pinned post, more video resources will slowly be added to this post too.

So here are the links and hope you enjoy!

The Way People Talk about Indigenous People and its Impact

The Equinox at Chichen Itza and El Caracol

The Maya, Aztec, and Mesoamerica - Part 1

The Maya, Aztec and Mesoamerica - Part 2 (FINAL)

#🇲🇽#indigenous#native#mexico#aztec#zapotec#maya#colonization#mexican history#europe#spain#history#history 📚#mesoamerica#hernan cortes#imperialism#colonialism#olmec

5 notes

·

View notes