Text

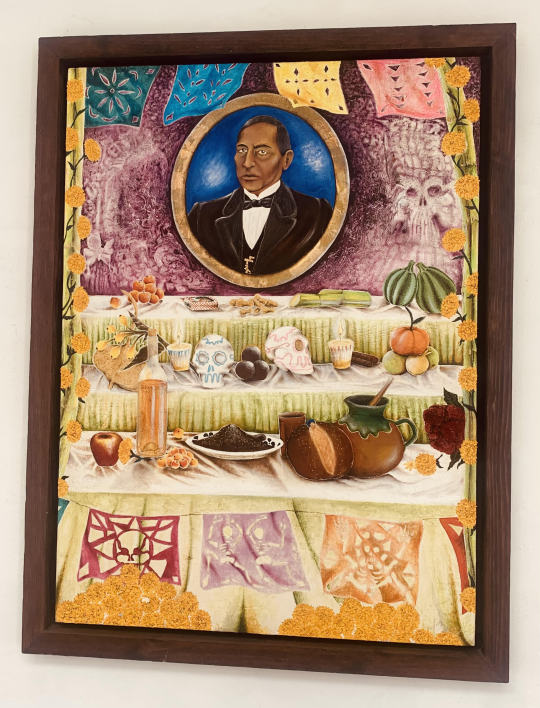

Benito Juárez: Hero of Oaxaca

"Men are nothing. Principles are everything." -Benito Juárez

When I was in Oaxaca, I noticed that many places and streets were named after two native sons of the state: Benito Juárez and Porfirio Díaz. Díaz is, at best, a complicated figure in retrospect, a bloody dictator that did much to modernize Mexico and bind it together into a modern nation-state, but who's rule was so oppressive it brought about the Mexican Revolution. Benito Juárez, on the other hand, is almost universally admired and celebrated. In the complex and divisive nature of Mexican history and politics, this is no small feat. Today is a national holiday celebrating his birthday. I did not have to work, so I thought I would write about Benny, “The Meritorious of the Americas”.

From the U.S. perspective, it is helpful to try and draw a similar analgous figure for Juárez to understand his importance to the development of Mexico. Being a liberal with progressive ideas and a desire to have a firm seperation between church and state, Benito is in many ways a Mexican Thomas Jefferson. In that he steered the country through an incredibly complex and violent time period, Juárez resembles Abraham Lincoln.

Benito was born in Oaxaca on the twenty-first of March 1806 to Zapotec parents. Being born to indigenous parents in a country that often downplayed indigenous identity may have instilled young Benito with a sense of service whereas other politicians had motivations of gold or glory. "As a son of the people," he once said, "I could never forget that my only goal should be their greater prosperity." He was orphaned at the age of three. As a young man, Juárez considered entering the preisthood but instead studied to become a lawyer, and eventually became involved in local and national politics, culminating in being elected govenor of Oaxaca in 1847. As govenor, he doubled the number of schools in Oaxaca from 50 to 100. Both in local and national office, Benito Juárez was hardworking and honest, and never personally profited from being in politics.

Benito Juárez became a critic of the Santa Anna government, which had just ceded a large tract of land to the United States in the Treaty of Hidalgo. When the Conservatives took power again, Juárez was forced to go north into exile. He worked at a cigarette factory in New Orleans in semipoverty.

Juárez was both a progressive and a modernizer. He believed that the only thing that could help Mexico and her poor would be to update the national economy, and that meant freeing the means of production from the Catholic Church and the landed aristocracy. Politically, Benito was a liberal, in that he believed Mexico needed a constitution that guaranteed certain individual rights and a federal system that granted individual states within Mexico some autonomy.

The moment came for Juárez to put his dreams into action when the liberals took control of the national government in 1855, and Benito joined as the minister for justice. As minister, he worked tirelessly to bring about the permanent seperation of church and state. Church property was nationalized, exempting only those buildings actually used for worship and instruction. To weaken the powerful Catholic clergy that meddled in Mexican politics, Juárez also nationalized the cemeteries and put birth registrations and marriages under government authority.

In 1861, Juárez officially became president of Mexico. There was no honeymood period of peace and calm, because there were several major issues that threatened the new president: Conservative forces that were against the reforms of Benito Juárez were still organized and politically dangerous, the new Congress distrusted the president, and the national treasury was basically empty. At the time of Juárez's inauguration, Mexico was deeply in debt to several European nations. Sensing an opportunity to recreate the French dream of an empire in the Americas, Napoleon III invaded Mexico in 1862. His plan was to indirectly rule Mexico through a puppet ruler, Archduke Maximilian of Austria. The Mexican forces had a great victory on May 5, 1862, but with reinforcements the French army was able to occupy the capital of Mexico City the following year, allowing the Austrian archduke to sit upon his throne.

These were difficult times for Benito Juárez and his forces. They were fighting a strong and determined enemy, but they too were equally determined to fight because the future of the Mexican state depended on them. To survive to fight another day meant that the war was not over, and that hope was still alive. After retreating all the way north to the United States border (to a place that would later be renamed Juárez), the tide began to turn in the favor of the Mexican forces. Due to international pressure and Mexican resistance, Napleon III withdrew his troops from Mexico. Maximilian, the foreigner who tried to claim the throne of Mexico, was caught, tried, and shot. Benito Juárez was president again.

There is much more that could be said about this great man. This was not meant to be an exhaustive list of the life and times of the first indigenous president of modern Mexico. I am sure books have been written about short periods of his life. HIs liberal ideas, economic reforms and calls for federal and constitutional government were progressive and forward thinking, and Mexico would eventually embrace and live out these ideas to the present day. His wisdom and lack of personal corruption made him one of the rarest things: A poltician it is easy to admire. His leadership and courage against the French made him a national hero.

On this day, we remember and honor Benito Juárez and his service and sacrifice for the people of Mexico. May we have politicians like him at all times in all places.

#21marzo#march21#historiamexicana#mexicanhistory#benitojuárez#heroesofmexico#mexicanhero#historia#historiademéxico#méxico#travelgram

0 notes

Text

The Triple Alliance: An Empire of Obsidian and Blood

"They make a desert and call it peace." -Calgacus

When the Spanish arrived on the shores of what today is Veracruz, they heard rumors of a great capital city of gold, full of fearsome warriors that required victims for the bloody altars of their hungry gods. History has come to call this polity that ruled much of what today is Mexico the Triple Alliance. What was the structure of this empire? How did it rule and what did it value? Can we even call it an empire at all?

As is often the case in history, the rise of a new, great power requires the fall of an older power. Before the rise of the Mexica and their city of Tenochtitlan, the dominating political force was a city called Azcapotzalco. As the great regional power, Azcapotzalco in effect ruled the valley, and demanded tribute and fealty from the other city-states in the area. After years of wandering and working as hired soldiers for more established nations, the Mexica had founded their city Tenochtitlan on an island in Lake Texcoco. Tenochtitlan was still a relatively new city, seeking more to stay safe rather than to dominate. Persuaded to align with a more established city-state, Texcoco, and another nearby kingdom, Tlacopan, Tenochtitlan and the others rose to fight a war to overthrow Azcapotzalco as the hegemon of the Valley of Mexico. It was a great gamble, because to lose would mean at best enslavement and at worst annihilation. Politics in ancient Mesoamerica was never a gentle sport. But the Three T's won, overthrew Azcapotzalco, and became the great power in the region the Spanish would encounter when they arrived by boat from Cuba in 1519.

In her excellent book, Fifth Sun, Camilla Townsend writes a new account of the history of the Mexica people (Aztecs). The great question is: How exactly did the Triple Alliance of these three Nahuatl kingdoms work? Was it even an empire by our Western definition? Townsend does a better job explaining it than I ever could, so I will quote her in full:

"The kings of Tenochtitlan (of the Mexica people), Texocco (of the Acolhua people), and Tlacopan (Of the Tepanec people) now ruled the valley as an unofficial triumvirate. There was no formal statement to that effect. Later generations would say they intiated a Triple Alliance, even though in a literal sense there was no institution. In a de facto sense, however, there most certainly was what we might call a lowercase triple alliance. No one moved in the central valley without at least one of these three kings being aware of it, and beyond the mountains that surrounded them, in the lands they gradually conquered, they had many eyes. They worked together to bring down their enemies; they divided the resulting tribute payments judiciously between them. The Mexica, with the largest population and having played the most important role in the war, got the largest share, but they were careful not to engeder resentment among their closest allies by taking too much (46)."

Conquered towns and cities were allowed to maintain some level of local self-government, as long as they paid tribute, and sent able bodied men to participate in public works, such as building roads or great temples. Many empires often seek to impose their culture, language, or religion on people assimilated into their empire (there is a reason much of Europe speaks Latin-based languages today). Was the Triple Alliance interested in "civilizing" or changing its conquered people, like the Spanish Empire that would in turn conquer them? Not so, Townsend writes:

"'This was no Rome,' one historian has commented succinctly, meaning that the Mexica had no interest in acculturating those they conquered, no desire to teach them their language, or to draw them into their capital or military hierarchy (47)."

In this sense, we could say the Triple Alliance were more like the Mongols, accepting of other gods, languages, and ways of life, as long as their overarching soverignty was acknowledged and their taxes paid. Like all successful empires, the Triple Alliance recognized good ideas when they encountered them, culturally borrowing (or stealing) ideas and practices from their neighbors and conquered peoples. The Mexica were in awe of the Olmecs and Toltecs and other long past civilizations of the region, and incorporated their religion and arcitecture. The Mexica considered the Maya to the south to be a political and cultural force in decline. But the Mexica admired the accomplishments made during their Golden Age and borrowed their writing system and based their calendar on Maya astronomy. Like the Romans, the Triple Alliance would wipe out rebellious towns and "call it peace", but they would rather these people be alive, paying taxes, and worshipping whatever gods they wished.

In fact, it was in part this relatively loose empirical arrangement that allowed the Spanish to conquer the Triple Alliance and siege Tenochtitlan. The Spanish were able to back a different rival prince for the throne of Texoco, Ixtlilxochitl, and divided the Triple Alliance against its self. Monster though he was, Hernán Cortés knew how to play different groups against each other for his own benefit.

#triple alliance#mexican history#historia mexicana#tenochitlan#La Triple Alianza#Hernan Cortes#Hernán Cortés#empire#history of empire#roman empire#romanempire#Mongols#Mongol Empire

0 notes

Text

More Virgins of Guadelope

I wrote previously of the cultural signficance of La Virgen de Guadelope, La Reina de México. Perhaps unsurprisingly, she was well represented in Oaxaca, so I thought I would share some photos.

#travelgram#mexico#cdmx#cdmx photos#virgen de guadalupe#catholicism#religion#folklore#mexico city#oaxacacity#oaxacadejuarez

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

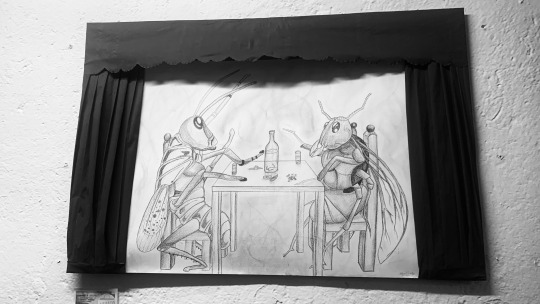

The Grasshoppers of Oaxaca

I have always been interested in the connection between food, history, and culture. I previously wrote about how the food of today can be a road map of past migration and cultural fusion, and how it can explain the evolution of a place like modern Mexico. Like communion in the Catholic Church, food can be a connection to our ancestors, a process and ritual that transcends time and generations. Food can be a bridge to the past…if we can find it.

Unfortunately we do not know a whole lot about what was eaten in Mesoamerica before the arrival of the Spanish. This is due in part to the great devastation brought by war, genocide, and disease during the Spanish Conquest, and approximately 90% of the population died by 1530. So much cultural knowledge and insight was lost. Another factor is that much of what the Spanish brought with them to the New World became common and integral to contemporary Mexican cuisine: Lime, honey, meat, and cheese.

We do have a few Spanish sources that wrote about what the Mexica ate before the Conquest. Hernán Cortés wrote in letters that Emperor Moctezuma’s feasts could be all day affairs, and Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote in his book, The Conquest of New Spain, the following: “Every day they cooked fowls, turkeys, local partridges, quail, tame and wild duck, venison, boar, marsh birds, pigeons, hares and rabbits, also many other kinds of birds and beasts native to their country, so numerous that I cannot quickly name them all.” But this is of course describing how the most powerful man in the Triple Alliance ate on special occasions. The Great Speaker was hardly the common man. While Moctezuma may have eaten well, people had to do their best catching wild game like duck or raising the only two domesticated animals, turkeys and chihuahuas (which were considered food). How did the common people get enough protein to survive?

On a recent trip to Oaxaca, I was shocked by how common it was to eat grasshoppers (in Mexican Spanish chapulin, which comes from the Nahua word chapollin). They would sell them in large quantities on the street, or you could order them in dishes like quesadillas and omelets. From the U.S. perspective, eating insects seems strange, but is common in many parts of the world. They are quite common in a warm place like Oaxaca and not hard to find. People enjoy the crunch they provide, like one would from a potato chip. In Mexico City, you can order guacamole with chapulines. Many Mexicans are proud of the cultural heritage this food provides, and there is a sense it connects them to their culture and history and land. It may seem like a bizarre food to a foreigner, but it has some merits.

While eating grasshoppers in Mexico is both a thing of the past and the present, it may well be a thing of the future. Insects are a bountiful natural resource of animal protein in the world today, in part because there are a lot more insects than people. They do not have the carbon footprint of cows, chickens, and pigs, and do not require the time, space, or resources those animals require. In his collection of short stories Brief Encounters with Che Guevara, Ben Fountain writes the story of a PHD student that came to the jungles of Colombia to study a rare colony of parrots only to be kidnapped by a Marxist rebel force clearly based on FARC. At one point, the graduate student, John Blair, makes the case to his captors that eating insects is the future, because they are affordable and sustainable. The heavily armed rebels laugh in his sunburnt face. “We are not fighting for the revolution to eat bugs, cabrón,” they say dismissively.

And yet, here in Mexico, the future may already be here.

#grasshoppers#mexicanfood#mexicanhistory#mexico#mexicocity#oaxaca#cuidaddeoaxaca#travelgram#culturamexicana#mexicanculture#mexicancuisine#cdmx#comidaprehispanica

0 notes

Text

More Corny Photos, Oaxaca Edition

In a previous post I wrote about how corn greatly influenced Mesoamerican civilization, mainly that the nutrition of cultivated corn and other crops allowed civilization to begin by settling down and leaving behind the nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle. Corn and human have had a symbiotic relationship, consideirng how humans had changed corn, breeding it to be larger and yielding more food, but corn as well has impacted humans and how they live. As the saying goes "there is no country without corn", corn has found its way into art and many human expressions in Mexico. The photos below are from Oaxaca.

Pictured above is Pitao Cozobi, the Zapotec Goddess of Corn. Perhaps because it was seen as the earth was "giving birth" to crops, the dieties of corn and agriculture in Mesoamerica were almost always female.

#elote#corn#hardcorecorn#cornagraphy#maize#mexicanhistory#mexicanart#artemexicano#historicamexicana#civilizaciónmexicana

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Land of the White Leadtree

In the heart of Mesoamerica sits three great valleys. They are large and expansive, ringed by mountains. These mountains protect the valleys from the worst storms and hurricanes that may drift over from the Pacific Ocean. Seven thousand years ago, these lands were inhabited by hunter-gatherers, tribes of people who would roam, following the good weather or potentially groups of white-tailed deer or other game. Over time, people began to realize they could grow more food than they could hunt or search for, and people began to settle down in permanent homes and farm the land. Corn, beans, and other crops were cultivated and the population began to grow. With the time allowed by sedentary life, art, music, and culture began to develop.

Different ethnic groups, whose languages are still spoken in the region, settled and developed complex societies: Zapotec, Mazatec, Chinantec, and Mixé. A distinct warrior culture developed in the valleys. The hilltop fortress city of Monte Alban became the capital of Zapotec culture, and ruled the neighborhood for four hundred years. After 1200 CE, the Zapotecs came under the growing influence of the Mixtec, a group that had come down into the valleys from the northwest. Both the Mixtecs and Zapotecs were conquered by the Mexica-led Triple Alliance in the 15th and 16th centuries. The new conquerors from Tenochitlan built a fort on a mountainside to collect tribute and oversee trade routes. The Mexica (Aztecs) called the valleys "Huaxyacac", after a tree that grows there. Today we would call that plant the white leadtree or river tamarind. This word eventually evolved into the name for both the city and the modern Mexican state: Oaxaca.

Shortly after the fall of Tenochtitlan, Spanish conquistadors arrived in the valleys of Oaxaca. The land was seen as a great prize among the invaders, and Hernán Cortés requested the title “Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca” from the King of Spain. The Spanish sent four expeditions to the region before they felt safe enough to found the city of Oaxaca de Juárez in 1529. The Spanish brought many new things with them to the valleys; Animals such as cows, chickens, horses, and pigs, as well as foreign crops such as vanilla, sugar, and tobacco. Due to war, disease, and repression, the indigenous population in Oaxaca suffered and drastically shrank, and rebellions continued through to the twentieth century. Catholicism became an important part of social life. But indigenous culture, language, and tradition in Oaxaca continue to survive and thrive. Two of the most significant leaders of modern Mexico, Benito Juárez and Porfirio Díaz, came from Oaxaca and both men were of indigenous descent. Juárez was born to Zapotec parents while Díaz was of Mixtec origin.

The city remains today, and every time period has influenced its contemporary cultural DNA: Colonial architecture, Catholic cathedrals, Spanish, Mixtec and Zapotec spoken on the streets, tlayudas (pictured above) and grasshopper tacos eaten with great relish in the city square.

If you ever get the chance, visit Oaxaca City. There is amazing art, food, drink, and plenty to experience.

#travelgram#mexico#historyofmexico#oaxaca#cuidaddeoaxaca#oaxacadejuarez#oaxacacity#historymexicana#aztecs#zapotec#mixtec#indigenousmexico#southernmexico#surmexico#historia#history#culturamexicana#mexicanculture#surdeméxico#cocinamexicana#mexicancuisine#ancientmexico#méxicoantiguo

0 notes

Text

The Glorious Street Food of Oaxaca

“They saw it as a food of the gods, and believed that the cacao tree originally grew only in Paradise, but was stolen and brought to mankind by their god Quetzalcoatl, who descended from heaven on a beam of the morning star, carrying a cacao tree.”

― Oliver Sacks, Oaxaca Journal

I am going to be going to Oaxaca City next week and I am super excited. The street food is supposed to be amazing. Here is a video that shows some places I am excited to check out:

youtube

#oaxaca#Cuidaddeoaxaca#travelgram#mexico#comidamexicana#mexicancuisine#gastronomiamexicana#mexicangastronomy#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Feliz Día de Muertos y Halloween!

"From my rotting body, flowers shall grow and I am in them and that is eternity." -Edvard Munch

One of the fun things about Mexico City is how thoroughly Juagulin (Halloween) and the Day of the Dead merge to create this super holiday and distinct season. Orange, purple and black flags float above entrance ways, and marigold flowers and pumpkins adorn doorways and windows. The most common symbol is a skull, which represents both death and rebirth. The Aztecs thought the afterlife was more important than our time on earth, so the Day of the Dead was not a time for mourning, but joy. Many families here will have their kids dress up in costumes on October 31st, go to mass on All Saints Day (November 1st), and then have altars for their dead family members on November 2nd.

I thought I would share a few photos I have taken around town. I particularly like how they have the dead do things alive people would do (sitting around chatting, drinking coffee, etc). I imagine the point of all this is to show the univerality of death, that is makes no sense to worry about something we all, in our time, must face. In death, there is no suffering, and the things that seemed to matter so much in life, no longer are factors (like food, money, status, etc.) Many of the skeletons are dressed up in rich and expensive seeming clothes, to drive home how frivilous and silly are the things that we, the living, so often care about. Be sure to check out the cool video at the end of a high tech ofrenda. Happy spooky season!

#mexico#cdmx#diadelosmuertos#halloween#mexicanhistory#travelgram#tradicionmexicana#cultura#decorations#calaveras#ofrenda#altar

0 notes

Text

This is Halloween

“Halloween is a celebration of the inversion of reality and a necessary Gothic hat-tip to the darker aspects of life, death and ourselves.”

― Stewart Stafford

Happy Halloween! May your days be dark, dreary, and spooky.

0 notes

Text

Amaizeing Cocktails!

"It's not true that you shouldn't drink alone: these can be the happiest glasses you ever drain.” -Christopher Hitchens

A few weeks ago, I wrote about how corn is an important source of nutrition, history, and Mexican culture. But there are any number of ways that corn is not eaten, but sipped. There is the corn and cacao based street drink Pozol and the sweet alcoholic beverage, Pox, both found in the southern state of Chiapas. For the ancient Mayans, Pox had a ceremonial and religious role, but today it is enjoyed casually on a typical Friday night by their descendants. There are any number of corn based beverages here in Mexico but I wanted to create a few of my own.

There is this alcohol brand I have seen at any number of bars and liquor stores and a few weeks ago curiosity got the better of me and I bought one. It is Nixta, a corn liquor or liquor de elote. Nixta is short for nixtamalization, a process by which corn is soaked typically in lime water and then hulled. Nothing is more Mexican than finding new ways to enjoy corn, so I decided to try and be creative and come up with a cornucopia (pardon the puns) of cocktails.

Jimmy Jack Corn

-.25 parts Nixta Licor de Elote

-2 parts Jack Daniels Whiskey

-1 dash of Angostura Bitters

-Splash of water

-Dash of sugar

-ice

-Garnish with a lime wedge

Pour the Nixta and Jack Daniels over ice in a rock glass. Add one dash of bitters and stir. Add a splash of water, dash of sugar, and a bit of the lime juice into the cocktail. Stir once more and serve.

The Mexican Godfather (El Padrino)

-2 parts Mezcal Toblar

.-25 parts Amaretto syrup

-.25 parts Nixta

-Splash of water

-Served over ice

A Mexican adaptation of a popular (and simple) scotch drink. Pour the mezcal, Nixta and amaretto over ice and stir in a rocks glass. Add a splash of water, stir again, and serve.

#mixology#halloweencocktails#dayofthedeadcocktails#diadelosmuertos#cocktails#corn#oldfashioned#whiskey#mezcal#tequila#bartender#bar#homebar#halloween

0 notes

Text

The Art of Remembering

“So long as we are being remembered, we remain alive.”

― Carlos Ruiz Zafón

For most of us, autumn is a contemplative season. If spring represents birth and renewal, and summer the glory and vitality of youth, then there is a wise wistfulness to the fall, of reflecting before the inevitable coming of winter and death. Being a transitory season, not quite summer and not quite winter, many cultures have viewed this time of year as a season where magical things can happen.

Halloween and the Day of the Dead are in many ways very different holidays from different places, but they are both based on this idea that this time of year is special, and that the border between worlds becomes thin and spirits can move amongst us. The ancient Celts of Ireland would leave out food and treats to try to appease the spirits that may cross over. From here it is easy to see where trick or treating evolved from, and the Celtic holiday of Samhain eventually became a major source for modern Halloween. The Aztecs believed that in the fall, spirits of loved ones could cross over, and visit us for a while. It wasn’t a time of sorrow, but a time of joy and remembering those who are dead but are not gone from our hearts. For the Aztecs, death was merely a door to another room, and we keep people alive by remembering and honoring them. These ancient beliefs underpin the modern practices of the Day of the Dead.

El Día de los Muertos is largely celebrated, both in private homes and in public displays, by the creation of ofrendas. These offerings or altars are meant to be a physical manifestation of the remembering, complete with photos of the deceased and items that they enjoyed or used, such as candy, cigarettes, or cans of beer. There are a lot of personal and regional variations in the styles of ofrendas, but there are certain symbolic items that are placed on the ofrenda that are crucial and long predate the arrival of the Spanish in Mexico.

One of the most important symbols of the Day of the Dead is cempasúchil, the Aztec name for the fragrant marigold flower native to Mexico. The Aztecs believed cempasúchil had a special smell that would guide the dead back to their families, so it is naturally an important part of the ofrenda. The flower is associated with Mictecacihuatl, or the Lady of the Dead, who permitted spirits to leave the underworld to commune with their families.

There are other ancient components of the ofrenda. Ceramic or sugar skulls are included to represent the truth that death is a part of life. An important element of the altar is salt, which represents the purification of the dead after they have moved on from this life. The salt is meant to purify the souls of the ancestors, so that they are able to travel back and visit next year. Candles are included to represent hope and faith, and light the way to the altar. An important symbol of the spirit and the afterlife is the xolo. Native to Mexico and one of the few domesticated animals of the Aztecs, the breed xoloitzcuintli was believed to help the spirits of the dead cross the Chiconauhuapan river and enter the underworld, Mictlān. In ancient times, people were even buried with these dogs. But today, placing a figurine on an altar will do. On my ofrenda, my xoloitzcuintli is also an alebrije, a spirit animal that is meant to guide and protect the dead as they travel through Mictlān. A common offering that is placed on the altar is water. In ancient times and today, it is believed that that the first thing the souls of the departed ask for after arriving in the underworld is water, as they are parched from their long journey.

In my second year living in Mexico, I decided to make my first ofrenda, in large part because I find the tradition touching and also, I hope, cathartic. In the United States, we tend to work very hard not to think about death and mortality, despite its universal inevitability. We pay a high price for these mental gymnastics: We often don’t take the necessary time to think of our loved ones who are gone, how they cared for us and made us the people we are today. As I look upon the faces of my grandparents, so young in their photos, I can’t help but wonder about their dreams and aspirations, if their lives turned out as they hoped, and what it must have been like to live through the Great Depression and World War II. El Día de los Muertos is not supposed to be a sad day, but a celebration, and yet I can’t help feeling bittersweet about the whole experience. These were people I loved. People who made me feel safe and loved. I am sad they are gone. But the Day of the Dead has given me the opportunity to honor them and be grateful. And maybe invite them to visit for a while.

#halloween#dayofthedead#thedayofthedead#ofrenda#altar#eldiadelosmuertos#diadelosmuertos#travelgram#mexico#México#culturamexicana#ElDíadelosMuertos#DíadelosMuertos#ofrendas#tradicionmexicana#autumn#fall

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Irish I was Mexican

A billion Catholics can't be wrong, right?

#halloween#Irish#Ireland#Mexico#Mexican#dayofthedead#catholicism#saintpatrick#Samhain#irlanda#méxico#culturamexicana#culturairlandesa#beer#tequila#spirits#ghosts#sugarskull#jackolantern#virgen de guadalupe#diadelosmuertos#juagulin#virgendelaguadalupe#calaverasdeazúcar#culture#meme#culturememe

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day of the Bread Part II

Autumn has arrived. It is getting cooler, and more leaves are on the ground. And it is the time of pan de muerto, or bread of the dead. Last week I wrote about the interesting history and origin stories of the common Mexican autumnal pastry. I like how this baked good is a good example of a modern culinary meme: There is a basic outline (shape, ingredients, taste, etc.) but there is a huge amount of regional and personal variations and people can put their own spin on it. Pan de muerto this time of year, like traffic or air pollution, is everywhere, cannot be escaped, and thus must be embraced. I wanted to share a few more photos of Dead Bread Season (included a scented candle for an ofrenda!) before it goes back into hibernation, not to emerge above ground until late September 2024.

#halloween#dayofthedead#mexicanfood#pandemuerto#breadofthedead#diadelosmuertos#travelgram#cuidadedemexico#chilango#mexicocity#mexico#cuidaddeMéxico#México#tradicionesmexicanas#postremexicano#postres#bakedgoods#panmexicano#pan#panaderia

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pan de Muerto or Carbohydrates of the Deceased

“Remember me as you pass by. As you are now, so once was I. As I am now, you soon will be. Prepare for death and follow me.”

– Traditional Calavera Verse

A fun fact about Mexico City is that oftentimes holidays or seasons are represented by a particular type of bread. For Christmas, there is Rosco de Reyes, associated with the three kings that brought gifts to Bethelehem. In mid-September, you begin to see an oddly named bread in bakeries and supermarkets: Pan de muerto, or bread of the dead. This bread appears when Mexico is preparing to celebrate Dia de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead. For those who haven’t seen the movie Coco, the Day of the Dead is the time of year when Mexicans remember and honor their ancestors. Pan de muerto is often placed as an offering on home altars for the visiting spirits of deceased family members.

By one estimate, between October 3rd and November 2nd (the actual Day of the Dead), over 30 million pieces of the bread are consumed in Mexico each year. 94% of Mexicans eat pan de muerto.

What exactly is it? Pan de muerto is a rich, doughy style bread, similar in consistency to challah bread and roughly the size of a hamburger bun. It is said to be shaped like a coffin, with designs of a cross or skull and bones sometimes placed on top. Often baked with butter to give it a rich flavor, there are regional variants, but generally it is topped with sugar and an orange zest.

Like almost all local food in today’s Mexico, the bread of the dead was born of the contact between the indigenous traditions of Mesoamerica and the Spanish arrival and colonization. The main ingredients (wheat, butter, milk, sugar) came to Mexico through the Columbian Exchange, the great swapping of people, diseases, animals, and plants between the Old World and the New. Among other things, pumpkins from the Americas were brought to Ireland, where they replaced turnips as the vegetable used to make jack-o-lanterns.

But while pan de muerto dates its creation to the time of the conquistadors in the 1500’s, the concepts behind the bread of the dead come from Mexica (or Aztec) religion and culture. One explanation is that around the start of Autumn, in order to give thanks for the harvest, the Aztecs would bake a type of bread made out of amaranth (a local grain), honey, and human blood as an offering to the gods. This was seen as a sacred offering, and was then eaten by the entire community. There is an echo of this today, in that the bread is eaten by the living relatives but is also thought of as an offering that is spiritually “nourishing” to the ancestors.

Another origin story for bread of the dead involves the Aztecs sacrificing a young woman, placing her heart in a clay pot, and then mixing the heart with grain. The priest would then eat the heart in gratitude to the gods for a good harvest. The Spanish priests quickly banned these types of practices, but the the modern pan de muerto was born: A bread to represent the heart sprinkled with red sugar to represent the blood of the sacrificial victim.

However it got started, pan de muerto is here to stay. A bakery near my house makes a version with a delicious mazapán cream inside. On a cool Fall morning, sitting outside with a hot coffee and a delicious bread of the dead, there is nothing better.

#Mexico#cuidaddemexico#México#diadelosmuertos#dayofthedead#pandemuerto#breadofthedead#mexicanfood#mexicancuisine#halloween#columbianexchange#mexicanbread#panmexicano#mexicantraditions#mexicanhistory#historiademéxico#tradicionesmexicanas#Mexicocity#travelgram#food#cocinamexicana

1 note

·

View note

Text

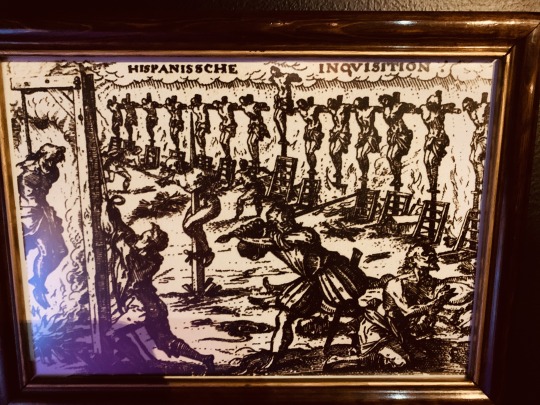

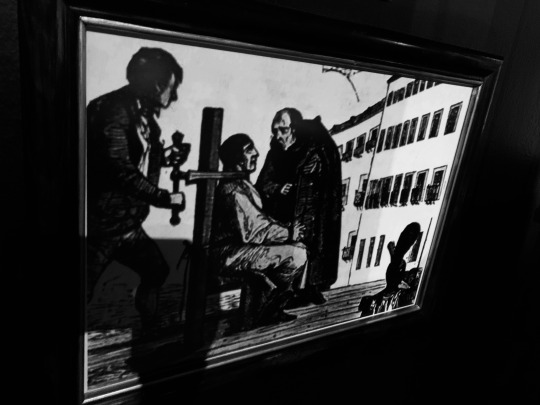

The Inquisition Comes to Mexico

“Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him.” -Fyodor Dostoyevsky

When Hernán Cortés and his small army arrived in Mesoamerica in 1519, they were horrified by the common practice of human sacrifice. The first town they arrived in still had wet blood on the temple floor. From the fundamentalist Christian perspective, Satan is “the prince of this world”, and thus all non-Christian faiths are on some level a form of Satan worship. The fact that the Aztec religion regularly required cutting out the hearts of people made this fact seem, at least to the conquistadors, rather obvious. Not surprisingly, the Aztec hosts did not much care for Cortés basically implying they were idiots for believing in such deities. “Throughout all time we have worshiped our own gods,” Emperor Moctezuma told Cortés, “and thought they were good, as no doubt yours are, so do not trouble to speak to us any more about them at present.” It has been claimed that part of the reason the Spanish attacked the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan so savagely, even by the standards of the day, was because of their hatred of human sacrifice.

There is of course a major fly in the ointment of framing the Conquest of Mexico as some sort of holy war against human sacrifice: The Spanish burned men alive, including Aztec warriors who had taken up arms against them. The Aztecs at least believed human sacrifice was required to keep the universe functioning and the world from ending, as ridiculous as this sounds in the age of science. The high and mighty Spanish burned men alive to strike fear into the hearts of their enemies, all while claiming they believed in a god of peace and forgiveness.

I have written a few posts about religion in modern Mexico, how it is in many ways both deeply Christian and at the same time something else entirely. There is no doubt that Catholicism, even in this modern secular age, is still important to many Mexicans. But it was also the tip of the spear for the Spanish conquest and colonization of Mexico, both as a rallying cry for the deeply religious conquistadors and as a way to justify imperialism and “civilizing” the indigenous population. Catholicism both destroyed what came before and brought into being Mexico as we know it today.

But the Spanish Catholics also brought something darker and more sinister to what at the time was called “New Spain”: The Inquisition. There is a museum that seeks to commemorate the horror and suffering brought by the Spanish Inquisition in Mexico City and I visited to learn more.

The exact causes of the Spanish Inquisition are complex. At a time when Martin Luther was preaching in Germany that the Pope was the Antichrist, and Galileo was peering through his telescope and directly challenging church dogma, some historians argue that the leadership of the Catholic Church had become deeply insecure. The Pope claimed to have authority over pretty much every aspect of human life, and having the church's authority seriously challenged made the Inquisition particularly violent and overreaching. Others like Sam Harris argue that the theological roots of the Inquisition had begun in the writings of the Catholic Church’s founding fathers, including that heretics should be tortured (as argued by Saint Augustine) or killed outright (as written by Saint Thomas Aquinas). What initially began as a exercise to enforce religious conformity on Catholics and purify the Iberian Penninsula after generations of Muslim rule, evolved to become a far-reaching organization that tortured, imprisoned and executed Jews, Muslims, Protestants, and women who did not conform to typical social norms. Dominican and Franciscian friars became the judge, jury, and executioner over terrified populations who would denounce their neighbors just to get ahead of being denounced themselves. The forms of torture were excruciating: People had their bodies stretched on the rack, spiked collars placed on their necks, and were burned alive merely for being assumed guilty of thought crimes. How fortunate that Spain brought the Inquisition 5,000 miles from Europe to the heart of Mexico.

The Spanish Inquisition is both fascinating and horrifying to our modern minds. It is obviously a form of collective delusion and hysteria that spiraled out of control, and the idea of a religious institution having such political and judicial power feels foreign to the world as we know it today. The Inquisition occurred at a time in history when many beliefs and concepts we currently hold as sacrosanct just simply did not exist: Human rights, the clear divide between church and state, acceptance of religious diversity, and even the right to a fair and speedy trial. Some languished and died in prison merely for an unsubstantiated accusation. Others were killed quickly before a trial or even a confession (or confessed for a quick death rather than be slowly tortured). The exact number of victims is hard to quantify. Some claim 30,000 to 300,000 perished during the Inquisition in Europe, while others claim the number is much higher.

The Inquisition in New Spain was less severe, in part because Mesoamerica was far from the religious fanaticism raging across Europe and because indigenous people, still seen as “uneducated” in the teachings of the Catholic Church, were largely exempt. Records are far from perfect, but around 50 people were killed during the Inquisition in Mexico, many convicted of heresy for having practiced or continuing to practice Judaism. There were a few cases of people executed for practicing Nahua sorcery. While that is a much lower number compared to the death toll in Europe, these were still people that were killed for merely practicing the religion of their ancestors.

The beauty of ancient churches, the sense of hope and community that comforts many believers, the veneration of the Virgin of Guadalupe: These are the positive benefits of Christianity in Mexico. But the Conquest and the Inquisition form the darker side of Catholicism coming to this corner of the Americas. Mexico has been profoundly shaped by both the good and the bad of the Catholic faith, and must reckon with both.

#cdmx#Mexicanhistory#religion#thespanishinquisition#NewSpain#Historiamexicana#historiademexico#Inquisiciónespañola#Catholicism#LaConquista#catolicismo#iglesiacatolica#elmuseodelatortura#torture#execution#religiónmexicana#judiosenmexico

0 notes

Text

Spinning Cones of Meat: A Cultural Convergence

“I've seen zero evidence of any nation on Earth other than Mexico even remotely having the slightest clue what Mexican food is about or even come close to reproducing it. It is perhaps the most misunderstood country and cuisine on Earth.”

-Anthony Bourdain

If there is one thing people in Mexico are proud of, it’s their food. Many people here see it as their national gift to the world. Whether it is a Michelin star restaurant or eating cheap tacos on the street, local cuisine is such a crucial part of Mexican culture and history.

Perhaps the most iconic culinary symbol is the trompo, the spinning cone of meat that is a staple at street side taquerías. Trompo is the term for a children’s spinning top, which makes sense given the shape of the spinning roasted carne. A vertical spit, with large chunks of meat stacked on top of it, is slowly turned in front of a flame so that it cooks for hours. If that doesn’t sound wildly appetizing to you, people here live for tacos al pastor (shepherd's tacos), perhaps the official dish of Mexico City. Usually at the top there is a chunk of pineapple that is sliced off and placed on the tacos. The trompo is so ubiquitous here that they are a popular costume for Halloween. Where did the trompo come from and how did it become such a symbol for street food and Mexico City?

With the increased mobility afforded by technology and the high number of interstate and ethnic conflicts, the twentieth century was one of the great periods of human movement in the history of the world. Mexico was not left out of these global changes. In fact, Mexico is a unique country where movement is concerned: It is one of the few countries that experiences both high levels of emigration (Mexicans moving to the United States and other places) and immigration (people moving to Mexico, primarily from Central America, looking for a better life). Migrants from the Middle East began coming to Latin America in the nineteenth century, but this accelerated in the twentieth century when the Ottoman Empire began to collapse after World War I. Lebanese immigrants reshaped many parts of Latin America, giving us the gifts of Shakira in Colombia and bringing delicious street food such as kipe to the Dominican Republic. By some estimates there are 800,000 Lebanese people and their descendants living in Mexico today.

In the nineteen thirties, these newly arrived Lebanese immigrants began opening restaurants in places like Mexico City and Puebla, offering Arab tacos (tacos arabes). They carefully cooked their meat in a style similar to that of a shawarma or kebab. They used a bread more similar to a pita than a tortilla. The tacos were originally filled with lamb (hence the name shepherd’s taco), a meat popular in the Middle East, but not a common part of culinary practice in Mexico. "People didn't like it so they tried it with beef and it didn't work out,” said Alejandro Escalante, the author of TACOPEDIA, an encyclopedia on tacos. “Finally pork got on this vertical grill and it turned out to be great." Pork is taboo for Muslims and thus is expensive and hard to find in places like Lebanon. But in Mexico it is everywhere.

After finally finding the right meat for trompos, eventually the Arab style bread was replaced with traditional corn tortillas. What was once foreign and unpopular, had become so intrinsic to street food culture it was hard to remember Mexico without it.

Food can be thought of as our cultural DNA. It tells us who we are, where we are, and where we come from. Tacos al pastor, with meat cooked in the style of the Levant wrapped in a tortilla, the staple food of Mesoamerica, is a perfect metaphor for modern Mexico. It makes me hungry just thinking about it.

#mexico#cdmx#streetfood#mexicancuisine#comidademexico#trompo#comidamexicana#travelgram#historiadecomida#lebanon#lebanesefood#tacosarabes#cuisine#historyoffood#pork#tacosalpastor#mexicanculture#culturamexicana

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Poet Prince of Texcoco

“O friends, to a good place we’ve come to live, come in springtime! In that place a very brief moment! So brief is life!” -Nezahualcoyotl

In the downtown Zocalo district, there is a small monument that you could easily miss unless you were looking for it. It is the Garden of the Triple Alliance, a peaceful monument to a violent empire. The Triple Alliance is a term used to describe the trio of Nahuatl city-states in central Mexico, Tenochtitlan (what is now Mexico City), Texcoco and Tlacopan, that together conquered much of what is today Mexico. While their dialects and religions varied slightly, they came from similar ancestors and had similar cultures. This small, quaint garden is a funny way to commemorate an empire that expanded through war and conquest, and would at times require sacrificial victims as tribute. The Alliance’s oppression and subjugation of other Mesoamerican peoples, such as the Tlaxacala and Toltecs, led in part to their fateful decisions to help the invading Spanish. But today this park is a lovely and peaceful spot amidst the chaotic churn of downtown.

Also commemorated in this park is Nezahualcoyotl, the prince of Texcoco. Born in 1402, Nezahualcoyotl (often translated as “Hungry Coyote”) became prince of his territory at the young age of fifteen, but was overthrown and forced into exile. Nezahualcoyotl would spend three years fighting and return with an army of 10,000 soldiers to return his family and regain his throne. As prince, Nezxhualcoyotl supported the artists and philosophers in his kingdom, and encouraged education. In the incredible historical novel Aztec, Nezahualcoyotl is portrayed as a cautious and clever leader, in contrast to the egotistical and ambitious, younger Moctezuma. Rebuffing Moctezuma’s desires to continue to use their armies to expand the empire, Nezahualcoyotl wisely plans to conserve his kingdom’s resources for whatever dark forces are amassing in the east. At that point in the novel (and history), both Moctezuma and Nezahualcoyotl have heard reports of strange, white men appearing on the eastern coast, and Nezahualcoyotl is proven right to view this threat as gravely serious.

There is something romantic, even cinematic, about this figure: A prince in exile, a warrior poet fighting to retake his kingdom. Later a wise, older ruler who can see the danger and destruction that is to come. There is of course, something deeply tragic about Nezahualcoyotl, too: He was a man who may have sensed his civilization would soon face an existential threat, and even with his foresight, knew there was very little he, or anyone, could do about it.

Nezahualcoyotl survives today not just in history, but in his writing. He is considered to be one of the greatest poets of ancient Mexico. The royalty and nobility of the Triple Alliance were expected to be well educated in many subjects, and nobles were taught how to use both the pen and the sword. There are some historical parallels with the samurais of Japan and the scholarly nobles of ancient Greece and Rome. It is amazing that we still have access to his poems, considering that poetry and literature at that time was often times memorized and reproduced orally, as well as the fact that there was great literary and cultural destruction by the Spanish in the generations after the Conquest.

Here is an excerpt of a poem written by Nezahualcoyotl, perhaps reflecting on his own experience of war and reconquest:

The battlefield is the place: where

one toasts the divine liquor in war,

where are stained red the divine

eagles,

Where the tigers howl,

Where all kinds of precious stones

rain from ornaments,

where wave headdresses rich with

fine plumes,

where princes are smashed to bits.

Here is another excerpt of a poem that is kind of like a pre-modern take on “these are a few of my favorite things”:

I love the song of the mockingbird,

bird of four hundred voices;

I love the color of jade

and the drowsy perfume of flowers;

but more than these, I love

my fellow human beings.

In recent years, as Mexico has strived to decolonize their national identity and intentionally celebrate their long ignored indigenous roots, Nezahualcoyotl has been frequently honored as a wise and fair ruler in Mexican history. There is a neighborhood named after him in Mexico City that, true to the character of the man, is home to many artists. He is even honored with his likeness on the 100 peso bill.

But I imagine the actual man would take all this recognition in stride. Like another poet who once famously wrote “nothing gold can stay”, Nezahualcoyotl also wrote about the impermanence and ever changing nature of life:

Truly do we live on earth?

Not forever on earth; only a little while here.

Although it be jade, it will be broken,

Although it be gold, it is crushed,

Although it be quetzal feather, it is torn asunder.

Not forever on earth; only a little while here.

#travelgram#mexico#cdmx#historiamexicana#mexicanhistory#aztec#poesiamexicana#mexicanpoetry#poetry#literature#triplealliance#triplealianza#parks#texcoco#history

3 notes

·

View notes