#kanehsatake: 270 years of resistance

Text

At Ninety-One, Alanis Obomsawin Is Not Ready to Put Down Her Camera

She revolutionized cinema and is inspiring the next generation of Indigenous filmmakers

Until a few years ago, the National Film Board was headquartered in a sprawling suburban complex off a Montreal highway. In 2019, it moved into its new downtown space, a slick thirteen-storey building designed with Obomsawin in mind. In a reception room on the main floor, a recording of an interview with her plays on loop. On the second floor is the 138-seat Alanis Obomsawin Theatre. A few floors above, a still from Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance covers the wall of a conference room. If her work and image are part of the building’s DNA, it’s because she has become, as Wente puts it, the raison d’être of Canada’s public film producer and distributor. “If you were to ask me why the NFB should exist,” Wente tells me, “she’s why. She’s who I would point to.”

Read more at thewalrus.ca.

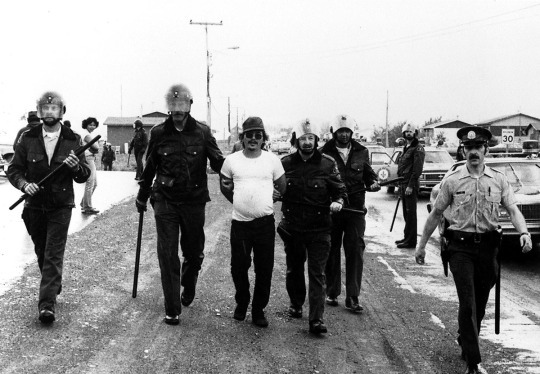

Stills and photography from When All the Leaves Are Gone (2010), Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993), Christmas at Moose Factory (1971), and Incident at Restigouche (1984), courtesy of the National Film Board

#Film#Documentary#Indigenous#Alanis Obomsawin#Directed by women#Photography#September/October 2023#Zoe Heaps Tennant

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celebrating Alanis Obomsawin!

"Alanis Obomsawin (Abenaki) is a trailblazing artist, performer and activist celebrated internationally as one of Canada’s most distinguished documentary filmmakers.... Her films address the struggles of Indigenous peoples in Canada from their perspective, giving prominence to voices that have long been ignored or dismissed."

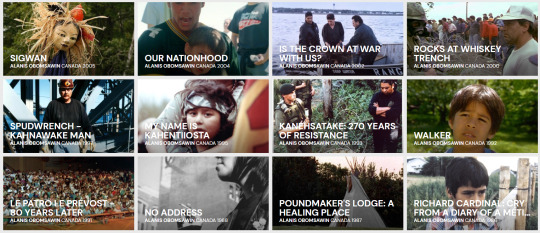

Streaming now through January 30, 2023 in Media City Film Festival's Thousand Suns Cinema:

Christmas at Moose Factory, 13 min, 1971

My Name Is Kahentiiosta, 29 min, 1995

Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, 119 min, 1993

'After the government told the film crew that they couldn’t guarantee their safety should a fight occur, only Obomsawin stayed. “I saw so many people, like the warriors, having so much courage—feeling that they had a mission in going through with this. I felt like I had the courage enough to stay there and document it, and that’s how the film got made.”'

Read more in Canada’s Documentary Essentials: ‘Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance’,

Find out more about Obomsawin's filmography on MUBI:

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Kanehsatake#indigenous rights#indigenous perspective#the canadian government does not represent or work for the people#postcolonialism does not exist#indigenous voices#oka crisis#no one is illegal on stolen land#mohawk#mohawk nation

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

There is a documentary called Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, not sure if you've even seen it, about Kanien’kéhaka resistance to golf courses being built on their land, and today I learned that almost no Canadian moviemakers in 1993 wanted to publish it due to it being "controversial"... Vile that Canada still hides behind it's "oh we're so friendly, eh?" façade regarding its Indigenous peoples, especially everything about MMIW.

Yes, I have seen it - It's from Alanis Obomsawin, who I first discovered through Is the Crown At War With Us and then went into a dive of her filmography. All great work IMO.

(FYI to anyone reading this interested, it is publicly available for free to stream HERE.)

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

17: Alanis Obomsawin // Bush Lady

Bush Lady

Alanis Obomsawin

1985, Radio Canada (Bandcamp)

youtube

A review of the well-meaning things I meant to say about Alanis Obomsawin’s Bush Lady

“No matter how accomplished Obomsawin’s sole LP, 1988’s cult classic Bush Lady may be, it’s naturally overshadowed by her extensive work as a documentary filmmaker. Her searing Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (available to stream for free from the National Film Board), covering the 1990 Oka standoff between local Indigenous land defenders, Quebec police, and the Canadian military, is a landmark. Her films are celebrated, broadcast on public television, and taught in schools.”

1.5/5—Book report quality. This is a not-very-slick way of admitting the only one of her movies I’ve seen in her most famous one. Also saying a director’s films are “celebrated, broadcast on public television, and taught in schools” in Canada sounds a lot like saying not many people have actually seen them.

“Her roots as a singer-songwriter predate her filmmaking, however. By the late 1950s, when she was in her twenties, she was performing and writing original songs in the Waban-Aki/Abenaki language, English, and French, but her recordings are sporadic prior to cutting this set at the CBC in the mid-1980s. The material was scantly issued at the time, and it probably found its widest listenership after a 2018 reissue by Constellation Records.”

2/5—Solid enough exposition, though it does beg the question why I didn’t just paste in the press release from the label.

“Bush Lady finds her singing and playing a handheld frame drum alongside a Quebecois chamber quartet. I was drawn to the record by ‘Odana,’ a melancholy fable about resisting colonial land grabs written in Abenaki by a tribal elder in the 1800s, which Obomsawin has presumably set to music of her own devising. Arranger Jean Vanasse and the quartet, likely trying to equate the song to a mode they were more familiar with, approach it like Nelson Riddle on Sinatra’s Only the Lonely. Nocturnal strings and woodwinds ripple around Obomsawin’s satiny vocal, lending the tragic folk tale the style of a blue ballad in an urban theatre.”

2.5/5—It took a while, but finally something about the music, an opinion even!

“There may be a bit of a feint in opening an album called Bush Lady with such a high-thread-count piece. ‘Odana’ lulls the non-Abenaki-speaking listener in with its soothingly westernized take on ‘Indian music,’ the lyrics’ message about stolen land masked by the unfamiliar tongue.”

2/5—Translation: “I am sort of embarrassed that the song I like best on this protest album is the one that sounds kind of like Nat King Cole, so I’ll change the subject to rhetoric.”

“But as the music segues into the theatrical 13-minute title track, its politics become explicit even to an English speaker. Obomsawin chants ritualistically over the insistent thump of her frame drum, interspersed with semi-spoken dialogue. She acts out characters: leering white men who harass and prey upon young Native girls; scornful, gossiping housewives; and finally the ‘Bush Lady’ herself, asking a white woman to care for her blonde mixed race child for fear it will be rejected by her own people. The recurring chant serves as a Greek chorus, a mournful counterpoint to the acrid sarcasm of the dialogue. The song undergoes a dramatic shift at the end when the fallen woman is visited by the spirit by her kokum (grandmother), who ushers her into paradise, accompanied by fluttering strings.”

3/5—Decent exegesis. But, dammit man, do you enjoy it or don't you?

“The track is a surprisingly good fit with reissuing label Constellation’s own catalogue. Like their cohort of Godspeed You! Black Emperor-adjacent projects, ‘Bush Lady’ is expansive and confrontational, fusing funereal cello and violin with blunt agitprop. When it works, it has a palpable force. Like agitprop though, the song isn’t subtle fare, and I have to admit the melodramatic conclusion (which is a harp or two away from a caricature of Christian heaven) feels a bit Wizard of Oz to me. I also don’t have a lot to say about the nearly side-length ‘Théo,’ a second drum-driven story song, this one sung in French. It is even more in a spoken word style than ‘Bush Lady,’ and as an Anglophone I can’t glean much despite another magnetic Obomsawin vocal.”

2.5/5—Reader, that must be one comfortable fence.

“I’m glad to have this reissue of Bush Lady in my collection for its transfixing A-side, and its significant overall historical interest. It’s well worth a listen for the curious.”

Overall review rating: 2.2142857142857142857142857142857/5, or 5 CLICK THE LINK TO WATCH HER FILMS FOR FREEs out of 5.

youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

locating myself

I am a settler in Canada, and recognize how my understanding of Indigenous cultures, history, and resistance is consistently mediated through the government and its projects of settler colonialism and white supremacy. Maintaining a personal practice of introducing myself to Indigenous writers, thinkers, and artists, and consuming their work, has helped me realise how misconstrued my previous understandings were, or more often just how much I did not know. Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993) was the first film of Alanis’ that I watched, and I remember how captivated I was by her ability to balance historical context with her subject matter, and the enduring honesty of her work. Many of her films have been jumping off points for me and my reading/listening/watching endeavours.

1 note

·

View note

Text

favourite film-makers (so far) from the thousand suns media festival - I still have roughly seven creators to watch

shelley niro: hers were the first of the collection that spoke to me, not on a level of learning (although -- as with all of them -- there is that too), but hitting something close to me in one of the films centering a character who inhabits some space of crossdressing/queerness. that film was also one of the few in the whole festival that is fiction rather than documentary. In the last couple of years I’ve been trying (and succeeding) to watch stories told outside of the mainstream, while asking myself, what are the narrative structures created? whose story is at the center? what are the ideas of crime/punishment + social acceptability/unacceptability and how are they challenged? I watched one of her non-fiction pieces too, and I am in love with her images in both of them, the second creating some visual poetry that is so simple and so affecting. have saved the last of her movies uploaded there for last

svetlana romanova: the first of her movies had a whole bunch of punk music in it, and started with someone getting a mohawk shaved on the side of a road, of course I was going to love it. both of her films feel anarchic and adventurous, I want to give her a million dollars (ok, the going rate for “big” movies is very expensive these days, but I think film-makers like this probably thrive on challenge, but emotionally all the moneys). like many others her films were depicting where she lives, and so there was a lot to learn, but hers specifically gripped me on a bigger scale -- not just the punk music, but, I think, mainly the way they’re doing the telling with a lot of very direct showing that seemed both natural and curated. simply put, the cinematic language was beautiful (as were the landscapes and people that the visuals were being trained on). someone on letterboxd said she ought to be given money to do a siberian western

mosha michael: according to the site, often referred to as the first inuk film-maker, starting in 1975. also according to the site, he died while unhoused as an alcoholic in 2009. I think I do a lot of projection onto his life between this, but I cannot help but see through researching him a lot of intensity for the work he was doing and a world in which earnestly wanting to share brand new artistic languages doesn’t get met with a lot of support (not necessarily financially, although there is that too -- more like there’s no way of bridging the gap between who you are and what you are seen as). there were several movies that centered on a day-to-day life in the festival collection, but his two that were presented just felt like I was watching them at the exact right time. they’re from the 70s, and filmed with Super 8, and they feel (to me) like I can reach in and touch them. I felt that way before I read up on him, simply like the viewer was involved in what was being shown

hon. mention to alanis obomsawin for putting images of protest out there that would never have been given longevity otherwise, and placing them within a wider historical political context with Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance

#im watching movies#im watching the thousand suns media festival#there was something about narrative i think in the movies/videos that i was drawn to the most#also there are some wonderful animations in some of the other films!#i am not as big an animation fan as i am live-action but i thought they were very neat

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

La première québécoise de ᑕᐅᑐᒃᑕᕗᒃ Tautuktavuk (Sous nos yeux) un film primé de Lucy Tulugarjuk et Carol Kunnuk – le lundi 11 décembre 2023 à 19h

Isuma Productions, Isuma Distribution International et Kingulliit Productions,en collaboration avec Cinema Politica, ont le plaisir d’annoncer que le long métrage dramatique primé TAUTUKTAVUK (SOUS NOS YEUX), coréalisé par Lucy Tulugarjuk (Tia and Piujuq, One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk, Atanarjuat : The Fast Runner) et Carol Kunnuk (Welcome to my Qammaq, Being Prepared, Attagatuluk), sera présenté en première québécoise comme film de clôture de la saison d’automne de Cinema Politica Concordia le lundi 11 décembre 2023 à 19h à l’Université Concordia (salle H-110).

La première québécoise sera suivie d’une séance de questions et réponses et d’une conversation avec Lucy Tulugarjuk et la documentariste Alanis Obomsawin (Incident at Restigouche, Kanehsatake : 270 Years of Resistance, Our People Will Be Healed). La table ronde sera animée par l’artiste multidisciplinaire, cinéaste et conservateur d’art Asinnajaq (Upinnaqusittik, Three Thousand). Tous les détails sont disponibles ici.

TAUTUKTAVUK (SOUS NOS YEUX) a été présenté en première mondiale au Festival international du film de Toronto (TIFF) en septembre 2023, où il a remporté le prix Amplify Voices BIPOC & Canadian First Feature Award, ainsi que le Sun Jury Award au 2023 ImagineNATIVE Film Festival.

Après sa première québécoise au Cinema Politica, TAUTUKTAVUK (SOUS NOS YEUX) sortira en salle à Montréal le 12 janvier 2024, avec des projections du film sous-titré en français et en anglais au Cinéma Moderne.Ce film inuit contemplatif, à la fois provocateur et subtilement intersectionnel, explore les points de convergence entre les mesures pandémiques, la violence domestique, la famille et les traumatismes intergénérationnels. Brouillant la frontière entre fiction et non-fiction, après un événement traumatisant, Uyarak et sa sœur aînée Saqpinak entreprennent un difficile voyage de guérison qui leur rappelle l’importance de la communauté, de la culture et de la famille. TAUTUKTAVUK (SOUS NOS YEUX) explore les questions de violence domestique et de toxicomanie du point de vue de deux femmes inuites.

0 notes

Photo

Some of the biggest moments and movements in modern human history have been (or are being) carefully documented by independent artists working in film, theatre, VR, music, and beyond.

For Preservation Week, we’ve highlighted a selection of Sundance-supported stories told by extraordinary artists during extraordinary times that must be seen and remembered. Read the full blog post Preserving the Record: Why Storytelling Is So Vital in Times Like These.

1. Trouble the Water film still. Courtesy Trouble the Water.

2. Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance film still. Courtesy of Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance.

#trouble the water#kanehsatake: 270 years of resistance#preservation week#extraordinary times#modern movements#storytellers#storytelling#storytelling saturday#independent artists#documentation#history#bear witness#black artists#indigenous artists#lgbtq#aids history#new orleans#hurricane katrina#angels in america#sundance film festival#how to survive a plague#the square#egypt#belgrade#whose streets#crip camp#disability-rights#ada#preservation#sundance

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm resharing this because the last version that I posted died? Which is interesting considering whats going on in the world today.

This documentary is about the Oka Crisis in Quebec about 30 years ago. And it all started with trying to build a golf course on a Mohawk graveyard.

#kanehsatake 270 years of resistance#oka crisis#indigineous people#canada#canada politics#documentary#me#mine

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

July 1st Activities

Preface: I am a white settler residing on Gitxsan territory. I have compiled this list (guided by this infographic from Covid19Indigenous, conversation with Indigenous friends, and conversation I’m seeing on social media) for anyone who wants to educate themselves about Indigenous people and/or support Indigenous people. I have done my best to only center Indigenous voices however, I acknowledge that as a white settler, I have blind spots, and if there are any issues with the list I have compiled or something should be added or removed, please let me know.

Watch a free film online to learn more about Indigenous Peoples

CBC Gem: Indigenous Stories Collection (all free)

Angry Inuk: (documentary) Exploring how Inuit hunters in tiny remote communities in the high arctic are negatively affected by animal rights groups protesting against the Canadian east coast seal hunt that happens a thousand kilometers away.

Birth of a Family: (documentary) Three sisters and a brother, removed from their mother's care as part of Canada's infamous Sixties Scoop and adopted as infants into separate families across North America, meet for the first time.

The Grizzlies: (movie) An Inuit community in the Arctic is transformed when a high school teacher reignites his students' passion for living through the game of lacrosse.

Indian Horse: (movie) The film follows Saul Indian Horse as he survives residential school and the racism of the 1970s. A talented hockey player, Saul must find his own path as he battles stereotypes and alcoholism.

Trickster: (TV series) Jared is only sixteen but feels like he is the one who must stabilize his family's life. He puzzles over why his maternal grandmother has never liked him, why she says he's the son of a trickster, that he isn't human.

We Were Children: In this emotional film, the profound impact of the Canadian government's residential school system is shown through the eyes of two children who were forced to endure unimaginable hardships.

Many more films are available

Much more info under the cut

National Film Board (some free, some paid)

Trick or Treaty: (documentary) Trick or Treaty? succinctly and powerfully portrays one community’s attempts to enforce their treaty rights and protect their lands, while also revealing the complexities of contemporary treaty agreements.

Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance: (documentary) In July 1990, a dispute over a proposed golf course to be built on Kanien’kéhaka (Mohawk) lands in Oka, Quebec, set the stage for a historic confrontation that would grab international headlines and sear itself into the Canadian consciousness. Director Alanis Obomsawin—at times with a small crew, at times alone—spent 78 days behind Kanien’kéhaka lines filming the armed standoff between protestors, the Quebec police and the Canadian army.

Many more films are available

YouTube

Blockade: (documentary) Documents the blockade of logging roads and the CNR railway line by the Gitksan in defence of their aboriginal land claims in British Columbia. Footage highlights differences in viewpoint between citizens of the white community of Kitwanga and natives of the Gitwangak Reserve vis-a-vis logging, moral and political issues.

Podcasts

Telling Our Twisted Histories: Words connect us. Words hurt us. Indigenous histories have been twisted by centuries of colonization. Host Kaniehti:io Horn brings us together to decolonize our minds– one word, one concept, one story at a time.

Nation to Nation: Nation to Nation takes a weekly look at the politics affecting Indigenous people in Canada.

Follow and Support Indigenous Artists and Creators

Michelle Stoney: Gitxsan artist. Instagram. Etsy. Facebook. (formline)

btw: she will be going live on insta/fb today to show how she does formline, not so anyone can use it, but just so people can learn more about it

also there are lots of free colouring pages on her FB and Insta

Home and Native Productions by Alex Stoney (photography and film)

Facebook

Gitxsan Mystic Crafts

Etsy. Instagram.

Chase Gray: Abbotsford-based queer xʷməθkʷəy̓əm and tsimshian artist.

Instagram. Website.

Luke Swinson: Anishinaabe - Mississaugas of Scugog Island First Nation.

Instagram. Website.

Check out this Twitter thread by Angela Sterritt for more

Learn about the History and Legacy of Residential Schools

Truth and Reconciliation Commission Findings

TRC Calls to Action

Beyond 94: CBC webpage that measures the progress of the Calls to Action.

Map of Residential Schools in Canada (only includes the schools listed in the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement)

Learn Whose Land You’re On

Whose Land

Native-Land

Contact your MP and Provincial Representative and Demand they Implement all 94 of the TRC’s Calls to Action

Current Members of Parliament

Current Cabinet

Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations

Alberta MLAs

British Columbia MLAs

Northwest Territories MLAs

Manitoba MLAs

New Brunswick MLAs

Newfoundland & Labrador MHAs

Nova Scotia MLAs

Nunavut MLAs

Ontario MPPs

Prince Edward Island MLAs

Quebec MNAs

Saskatchewan MLAs

Yukon MLAs

Donate

Indian Residential School Survivors Society

BIKE PROJECT for the children of Puvirnituq!

Follow Indigenous TikTok creators

Ashley Calingbull @ashleycallingbull

James Jones @notoriouscree

Sherry McKay @sherry.mckay

Shina Nova @shinanova

Tia Wood @tiamischihk

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 27, 2022 - Beans

Beans (2020) Tracey Deer, 1h 32min [QC Thurs]

“My name is Tekehentahkhwa” - Beans

Tracey Deer’s Beans is a coming-of-age story of a Mohawk girl set in 1990 during the Oka Crisis.

Tekehentahkhwa (Kiawentiio) is 12 years old and she loves art and her younger Ruby, and really admires her mom. That’s why she’s interviewing to go to a private school, because she knows it will make her mom happy. She also kinda wants to go because of the art supplies she saw there, but it’s mostly because of her mom. Mostly.

After repeatedly saying her name to the white lady across the desk, Tekehentahkhwa reassuringly tells her it’s okay to call her “Beans” because everyone else does.

Bean’s aunt Hawi is part of a group protesting the expansion of a golf course in Oka that would destroy a sacred Mohawk site. Beans and family decide to visit Hawi to lift spirits and bring supplies. While on that visit, the local police force instigates a riot that leads to a months long blockade after the army arrives.

The people who were once protesting are now trapped alongside families without access to outside food or supplies. The community quickly pulls together to wait it out and survive this volatile situation. Beans and Ruby have to find a way to fit in, as they’re city kids. Most of the other kids there with them are teens. The worldly April takes a reluctant shine Beans and vows to toughen Beans up for the real world through physical injury and improved fashion.

We watch Beans as she grows, learning that the world is not as sympathetic as she thought; where people don’t act the way they’re supposed to act. People who never met you will hate you. People who are supposed to protect you will be indifferent or try and hurt you[i].

It’s a struggle to figure out what the right thing is to do; what is the right kind of Mohawk to be?

The film is beautifully shot, with lots of lovely wide angles to bring the audience into this world – a home thrown into crisis. Light streaming through trees and bright green grass as the girls play. Then fires flickering in the silence of the night that conveys the anxiety of the people on the front line as they await the inevitable racist violence from the locals and the police[ii].

Kiawentiio who plays Beans captures both the character’s intelligence and naivety as the later changes from experience. Rainbow Dickerson is wonderful as Bean’s mom Lily, a practical yet loving woman.

An affecting and moving film. Recommended.

TRAILER: https://youtu.be/MIlC3zT1gw4

NOTES:

[i] Content Warning: There is sexual assault and the revelation of assault in the film

[ii] Tracey Deer based much of the film on her own experience as a child during the Oka Crisis : https://variety.com/2020/film/spotlight/tracey-deer-beans-toronto-1234767591/

I also would direct you to Alanis Obomsawin’s documentaries Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993) and Rocks at Whiskey Trench (2000)

#film penance#filmpenance#filmpenance2022#beans 2020#beans the film#movie review#film review#lent#recovering catholic

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

I was a 16-year-old living in a sprawling suburb north of Toronto when Mohawk land defenders faced off against military and police forces at Kanehsatake in the summer of 1990.

I was only vaguely aware of the deadly standoff unfolding just a five-hour drive away. A private golf course, supported by the town of Oka in Quebec, wanted to expand onto land claimed by the Mohawk Nation in neighbouring Kanehsatake. The fairways and greens would push through a pine forest sacred to the Mohawks, where their ancestors were buried.

If I had an opinion on the Oka crisis then, it wasn’t strong enough to last 30 years. I do recall a vague sense of injustice and discomfort with the white, middle-class opinions that surrounded me.

Thirty years later and more than 4,000 kilometres away, I was a journalist covering the Wet’suwet’en conflict as it unfolded 100 kilometres south of my home in Smithers, British Columbia this winter. Land defenders supporting hereditary chiefs had blocked portions of the Morice West Forest Service Road, denying access to pipeline builder Coastal GasLink. The RCMP had responded by filling hotels in local communities with armed officers ready to remove the barricades.

I made many reporting trips to the Morice, travelling a snowy highway and rugged forestry road in temperatures that sometimes dipped below -40 C. On my final journey before the RCMP moved in to clear the blockades in early February, I travelled 22 hours by car, foot and snowmobile to spend six days reporting for The Tyee from the Unist’ot’en Healing Centre. I was there when heavily armed police, supported by helicopters and search dogs, made the last arrests.

I decompressed one evening several weeks later by curling up in front of Alanis Obomsawin’s 1993 NFB documentary Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance.

I was struck by how little had changed.

Continue Reading.

Tagging: @politicsofcanada @abpoli @pnwpol

189 notes

·

View notes

Photo

30 years since the Kahnawà:ke Uprising (Oka Crisis in bougie press)

Watch Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance

40 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (Dir. Alanis Obomsawin) I see clips included in this film get circulated all the time on...

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indigenous Resistance Through Film

Obomsawin reimages Indigeneity through the medium of filmmaking. Following the lives of Indigenous people across “Canada,” and taking a particular interest in their struggle for sovereignty and state recognition, Obomsawin renegotiates the objective, omnipotent presence of the documentary filmmaker and rather positions herself within the struggle, centering Indigenous culture, history, and experiences as the argument, evidence, and conclusion of her films. Therefore, her work contests twofold; firstly the ways in which documentary filmmaking as a medium has been used in the colonial sense to control public perception/understanding of a certain event, people, or history, and secondly, the subject matter of her films — seminal Indigenous issues and events in Canada — expose the continuous colonial violence that is enacted upon by all levels of government towards Indigenous people, whilst challenging official histories and narratives about Canada’s relationship with Indigenous people. Her films continue to see what the rest of the county cannot see, or chooses to ignore.

Obomsawin’s filmmaking practice begins with listening. Often, before any second that is caught on camera, she will go into the community that she is working with alone, without a crew or a camera, and engage in conversation and daily life. She insists on building relationships and connections first, attentive to witnessing before any act of producing. Her participatory style of filmmaking adapts the didactic documentary tradition. Obomsawin appears in all of her films, seated in homes interviewing subjects, engaging with children in schools, or barricaded behind the lines during a resistance. You will often hear her voice encouraging subjects during interviews, or laughing with a group. Her presence throughout the films reminds viewers of her intimate, intrinsic connection to the subject matter — as an Indigenous woman she is just as much shaped and informed by the events, communities, and histories that she documents.

The subject matter of Obomsawin’s films speak to the ongoing effects of settler colonialism, genocide, persecution, and state surveillance of Indigenous people. Incident at Restigouche (1984) follows the raids on the Listuguj Mi'gmaq First Nation by the Quebec provincial police, as an effort of imposing restrictions on their fishing rights, Richard Cardinal: Cry from a Diary of a Métis Child (1986) is a devastating examination of Canada's child welfare system in regards to the (mis)treatment of Indigenous children and youth, and the harm that the system causes. Christmas at Moose Factory (1971), her first feature-length film, is filmed at a residential school in northern Ontario around Christmas time, Hi-Ho Mistahey! (2013) follows the campaign Shannen’s Dream, which lobbies for improved educational opportunities for Indigenous youth, and examines the on-going impacts of the lack of proper education for Indigenous youth, and Our People Will Be Healed (2017) profiles the Helen Betty Osborne Ininiw Education Resource Centre in Norway House Cree Nation, the structure of the school, offering a vision for what Indigenous based education could look like in the future, whilst recognizing the challenges the school is facing today.

Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993) documents the Kanehsatà:ke Resistance/Oka Crisis and is the most well known of Obomsawin’s films. Had it not been for Obomsawin and her crew documenting 250 hours worth of footage behind the barricade, in standoff with the military, and at the end of resistance, the public memory of this event would have been shaped solely by one-sided government press releases, limited CBC reporting, and Prime Minister Mulroney asserting that the Mohawk warriors were dangerous criminals with illegal weapons. Emotive, intense moments behind the barricade, articulated through interviews with individual Mohawk warriors, offer a closer account of the events instead. Obomsawin’s uncompromising and partisan view of what occurred at the Oka golf course gave way for Mohawk historical narratives to be re-articulated and Indigenous efforts for self-determination to be legitimised.

1 note

·

View note