#native plants of North America

Text

Virginia Springbeauty (Claytonia virginica)

One of the earliest spring flowers!

It is called "fairy spud" because it produces tubers that you can eat just like potatoes!

A particular species of mining bee depends almost entirely upon this plant!

It can go in a lawn—it will blanket the ground in blossoms in early spring before mowing starts, and die off before summer. The leaves look just like grass. (I think it probably needs fallen leaves for support and moisture though!)

#native plants#native plant gardening#lawn alternatives#no lawns#plants#native plants of north america#usa centric#kentucky#eastern usa#gardening#flowers#spring

363 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quaking Aspen - Populus tremuloides

Today I want to bring up a charismatic favorite: the Quaking Aspen. Like all populus species, it's a fast growing, clonal colony forming, northern extreme and mountain loving tree (just like its Eurasian sister species: A. tremula) with an incredibly wide range of distribution. In addition to all those interesting qualities, the oldest known organism is presumed to be a Quaking Aspen colony (Pando, in Utah)

General identification before I can talk about the more interesting bits, Aspens are best known for their yellow autumn leaves and smooth white bark with dark knots, they can grow as large as 60' but depending on their environment can be stunted to around 5-20' (think of krummholz). Leaves of this species appear slightly heart shaped and retain the same sheen on both sides (image 1). Plants are unisexual meaning individuals either have male or female flowers, interestingly enough this is a good method to distinguish where one colony begins and ends by looking at the color of the branches in spring (see image from Colorado below, note trees with light green and those without). Emerging catkins are white at first which become green and longer as the season changes, male catkins having slightly longer stamen but female fruiting catkins ultimately growing longest at 10 cm. Seeds are small capsules with silky hairs to assist in wind dispersion, these trees are ruderal so they produce around 1.6 Million a season with many unable to germinate. Seedlings often need consistent moisture and full sun to even germinate, most of the seeds growth goes to root structure the first year.

The name Quaking Aspen (or trembling per the Latin) refers to the extremely mobile habit of the leaf. Leaves are connected to flexible petioles (stems) which flip around in the slightest breeze. Environmentally speaking, I was once told that leaves have chlorophyll on both sides however this stem could also be a biological strategy to cope with harsh wind conditions in mountainous environments, I didn't encounter any recent research verifying this though. Interestingly enough, given the harsh nature of which this tree thrives, apparently, there is chlorophyll in its trunk, allowing extra energy to enter the tree when it's leaves are gone.

Quaking Aspen is an early succession species, able to reestablish/colonize a site after a fire or other major disturbance. Many of Upstate New York's famous Aspen forests are actually a result of logging and fires in the early 1900s rather than a typical forest compostion. Establishment is different depending on opportunity, in the west its often long lived clonal roots systems, in the high arctic its often through wind blown seed, in the east its generally short lived clones out-competed by hardwood/conifer forest after a century, and in its furthest southeastern range I typically only encounter individuals on rocky outcrops or former fields.

Above ground trees usually live less than a century, in the east maybe 50-80 years given our moisture, out west individual trunks can live two centuries. It's common to find dense forests with even-age trees since clonal root structures re-emerge together (Image above from Bluebell Knoll Mountain in Utah). Its also thought that the root system can live for two millenia or longer, Pando being an example of extreme longevity (I mean 40,000 years would survive an ice age, even in Utah there would be mountain glaciation, thats quite spectacular if true). Ironically, one of the best survival tools in the Aspen's playback is fire recovery, otherwise it will get out-competed/shaded pretty fast (see the context in image 2, that NJ forest used to have lots of aspen).

All this in mind its good to point out that Aspen's early successional habit makes it great for ecological restoration. It's common to find them as the first pioneers on former mines or superfund sites (aspen grove below from Palmerton gap, Pennsylvania). Unfortunately one of the negative side affects is that populus species often bring up a lot of heavy metals in their leaves and wood meaning they can re-contaminate through their own biological accumulation. Which is good for extracting small scale contaiminants...very bad for large sites where you need to trap metal under soil to prevent toxins from eroding offsite

All this being said Quaking Aspen's large geographic range mirrors that of the last glacial maximum, implying a rapid spread onto retreating glaciers. This also suggests a growth habit requiring wet or moist soil conditions. This range is North West to Alaska nearly touching the Arctic Ocean at its Northern-most range in the Yukon, then east to Newfoundland; south west to Mexico (usually restricted to high mountains) and east from Iowa to New Jersey (with scattered populations in West Virginia).

Since Aspen often colonizes sites of former glaciation, with climate change it's predicted there will be a northward and uphill progression of populations. Aspen isn't really in intense danger of dissappearing but studies have shown major stressors (draught, extreme heat, over-grazing) cause higher mass-mortality events from minor stressors (typically disease and insect herbivorey). Given the fact that many forests are clonal there was a question of low genetic diversity amoung populations, yet interestingly, individuals undergo somatic mutations (DNA alterations after conception) and are extremely variable, so different individuals often place different energies into different defense tactics.

In addition to all of this information Aspens are primarily used today to make paper pulp. Historically settlers used aspen to derive quinine (think gin and tonic), and indigenous tribes have a history of using big trunks to create dug out canoes.

So please go out to your nearest mountain/boreal forest to enjoy the Quaking Aspen's lovely smooth bark and haunting shaking in the wind!

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh my gosh!!! 🦊 Poor thing is injured.

#red fox#fox#homegrown national park#plant native plants#native plants#if you grow them they will come#native plants of north america#certified wildlife habitat#respect nature#vulpes vulpes#backyard habitat

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Native Plants I’ve Actually Seen Growing Wild in Southern Ontario

Acer saccharinum (silver maple) --along the sides of highways

Acer saccharum (sugar maple) --GTA ravines

Achillea millefolia (yarrow) --GTA ravines

Allium schoenoprasum (wild chives) --GTA ravines, Ridgetown

Allium tricoccum (ramps) --Niagara region escarpments

Amaranthus retroflexus (redroot amaranth) --fallow areas in the GTA

Ambrosia artemisiifolia (ragweed) --fallow areas in the GTA

Ambrosia trifida (giant ragweed) --parks in the GTA

Amelanchier spp. (saskatoon/serviceberry) --GTA ravines

Arisaema triphyllum (Jack-in-the-pulpit) --GTA ravines

Aronia melanocarpa (black chokeberry) --ravines and parks in the GTA

Asarum canadense (Canada ginger) --GTA ravines

Asclepias syriaca (common milkweed) --fallow areas, ravines, and parks throughout southern Ontario from Windsor to GTA

Asplenium trichomanes (maidenhair spleenwort) --Niagara region escarpments

Betula spp. (birch) --ravines and parks throughout southern Ontario from Windsor to GTA

Bidens spp. (beggar ticks) --GTA ravines

Caulophyllum thalictroides (blue cohosh) --GTA parks

Ceratophyllum demersum (hornwort) --GTA ravines (native in freshwater across the globe anyway)

Circaea lutetiana (enchanter’s nightshade) --fallow areas in the GTA

Commelina spp. (dayflower) --fallow areas in Windsor

Cornus alternifolia (Pagoda dogwood) --GTA wooded areas

Cornus sericea (red osier dogwood) --GTA ravines and in Windsor riverside parks

Crataegus spp. (hawthorn) --GTA ravines and parks

Echinocystis lobata (wild prickly cucumber) --GTA ravines

Elaeagnus commutata (silverberry) --GTA parks and fallow areas

Epilobium ciliatum (fringed willowherb) --fallow areas in the GTA

Equisetum spp. (horsetail/scouring rush) --GTA ravines and fallow areas

Erigeron spp. (fleabane) --GTA parks and fallow areas, Ridgetown

Erythronium americanum (trout lily) --GTA ravines and parks

Eutrochium maculatum (Joe-Pye weed) --GTA parks

Fragaria virginiana (wild strawberry) --fallow areas in the GTA

Geranium maculatum (wild geranium) --Windsor green spaces

Geranium robertianum (herb robert) --Windsor green spaces

Geum aleppicum (yellow avens) --GTA fallow areas

Geum canadense (white avens) --GTA fallow areas

Geum macrophyllum (large-leaved avens) --GTA fallow areas

Gymnocladus dioicus (Kentucky coffee tree) --GTA ravines

Helianthus spp. (sunflower) --GTA fallow areas and parks

Heracleum maximum (cow parsnip) --GTA ravines

Hordeum jubatum (foxtail barley) --GTA fallow areas

Humulus lupulus (hops) --GTA ravines

Hydrophyllum virginianum (Virginia waterleaf) --GTA ravines

Impatiens capensis (jewelweed) --GTA ravines and in Windsor riverside parks

Juglans nigra (black walnut) --GTA ravines

Lactuca canadensis (Canadian lettuce) --GTA fallow areas

Lilium michiganense (Michigan lily) --GTA ravines

Lupinus perennis (sundial lupine) --GTA parks

Maianthemum canadense (Canada mayflower) --GTA ravines

Maianthemum racemosum (starry false solomon’s seal) --GTA ravines and parks

Maianthemum stellatum (starry false solomon’s seal) --GTA ravines

Matteuccia struthiopteris (ostrich fern) --GTA ravines

Monarda fistulosa (wild bergamot) --GTA ravines and parks

Morus rubra (red mulberry) --fallow areas in Windsor, GTA parks

Myosotis laxa (smallflower forget-me-not) --GTA fallow areas

Oenothera biennis (evening primrose) --GTA fallow areas

Onoclea sensibilis (sensitive fern) --GTA ravines

Oxalis stricta (yellow wood sorrel) --fallow areas and ravines throughout southern Ontario from Windsor to GTA

Parietaria pensylvanica (Pennsylvania pellitory) --GTA fallow areas

Parthenocissus quinquefolia (Virginia creeper) --Windsor fallow areas and GTA ravines and parks

Persicaria lapathifolia (curlytop smartweed) --GTA fallow areas

Podophyllum peltatum (mayapple) --GTA ravines and parks

Portulaca oleracea (purslane) --fallow areas throughout southern Ontario from Windsor to GTA (native globally anyway)

Potentilla norvejica monspeliensis (ternate-leaved cinquefoil) --GTA fallow areas

Prunella vulgaris (selfheal) --fallow areas and ravines throughout southern Ontario from Windsor to GTA

Prunus virginiana (chokecherry) --Windsor fallow areas, GTA ravines and parks, Niagara region escarpments

Pteridium aquilinum latiusculum (western bracken fern) --GTA parks

Quercus spp. (oak) --wooded areas throughout southern Ontario from Windsor to GTA

Rhus typhina (staghorn sumac) --parks and fallow areas throughout southern Ontario from Windsor to Collingwood

Ribes spp. (currants) --GTA ravines and parks

Ribes spp. (gooseberries) --GTA ravines

Robinia pseudoacacia (black locust) --GTA ravines and parks

Rosa spp. (roses) --GTA ravines, parks, and fallow areas

Rubus occidentalis (black raspberry) --ravines, parks, and fallow areas in Hamilton and GTA

Rubus odoratus (purple-flowered raspberry) --GTA ravines and parks

Rubus strigosus (American red raspberry) --GTA parks

Rudbeckia hirta (black-eyed susan) --GTA parks

Salix spp. (willow) --GTA ravines

Sambucus canadensis (common elderberry) --Windsor riverside parks, GTA ravines

Sambucus racemosa (red elderberry) --GTA ravines and parks

Smilax spp. (greenbrier) --GTA parks

Solidago canadensis (Canada goldenrod) --parks and fallow areas throughout southern Ontario from Windsor to GTA

Sorbus spp. (mountain ash) --GTA ravines and parks

Streptopus spp. (twistedstalk) --GTA parks

Symphoricarpos spp. (snowberry) --GTA parks

Symphyotrichum ericoides (heath aster) --fallow areas throughout southern Ontario from Windsor to GTA

Symphyotrichum novae-angliae (New England aster) --fallow areas throughout southern Ontario from Windsor to GTA

Symplocarpus foetidus (skunk cabbage) --GTA parks

Tilia spp. (linden) --GTA ravines

Trillium grandiflorum (white trillium) --parks throughout southern Ontario from Windsor to GTA

Tsuga canadensis (eastern hemlock) --GTA parks

Typha latifolia (broad-leaved cattail) --marshes in Essex county and GTA

Urtica gracilis (slender nettle) --GTA ravines

Uvularia spp. (bellwort) --streams in Windsor green spaces

Verbena hastata (blue vervain) --GTA ravines

Viburnum lentago (nannyberry) --GTA parks and Ridgetown ravine

Viburnum trilobum (highbush cranberry) --Ridgetown

Viola sororia (wood violet) --fallow areas and wooded areas throughout southern Ontario from Windsor to GTA

Vitis riparia (riverbank grape) --GTA fallow areas, ravines, and parks

Waldsteinia fragarioides (barren strawberry) --GTA ravines and parks

Xanthium strumarium canadense (Canada cocklebur) --GTA parks and fallow areas

I’ve likely seen many others and just couldn’t identify them, but there are a lot I’ve never seen growing wild. What I’m hoping is that some of the native species I have in my garden will make their way to the nearby ravine. If I get around to it, though, I might just take a walk with some Asclepias incarnata (swamp milkweed) seeds in the fall. They certainly seem to successfully germinate in my garden whether I want them to or not (don’t have space for them to go crazy). Can’t see why they wouldn’t in a natural swamp area.

#text post#long text post#native plants of Ontario#native plants of North America#wild native plants

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red baneberry, in western Montana. Regrowth after last year's wildfire. Actea rubra. Ranunculaceae.

0 notes

Text

All the babies. Of the ~550 trays here, I personally seeded about 240 of them. Only the very early stuff is coming up, mostly the alliums and violets. Every single one of these was seeded by hand from seeds we stratified (unless they don’t require stratification). There are 70,040 cells in here and our germination rate is very high, we usually have just as many finished plants as there are cells started. So around 70,000 native plants will be sold to the public and some local government programs but they’ll all get planted somewhere. 70,000 more links in the chain for the ecosystem. 70,000 more chances a pollinator finds the plant they need to survive. 70,000 more root systems anchoring degraded soils. 70,000 more reminders that the earth is home for all of us, including those who cannot speak and are easily ignored.

This is the 5th season my boss has grown native plants for sale at this scale. So there may be as many as 350,000 plants out there that he ushered along into existence. To do all this work, stratifying and hand seeding, takes about two weeks (not including the 90 days the seeds just sit in the fridge). It’s not impossible, there’s very little mystery, once you find your rhythm it’s all very doable. You take the time to tediously tweezer a little gooey clump of seeds into a seedling cell 128 times and that’s one tray. You do that for 20 trays, that takes about 5 hours. You go to lunch. Repeat for two weeks. Your coworkers come in after you and do the same thing. Three people make enough plants to cover about 1.5 acres of land. It’s not changing the world but it is changing my town.

#native plants#nature#plants#gardening#greenhouse content#seeds#seed starting#spring#north america#great plains

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

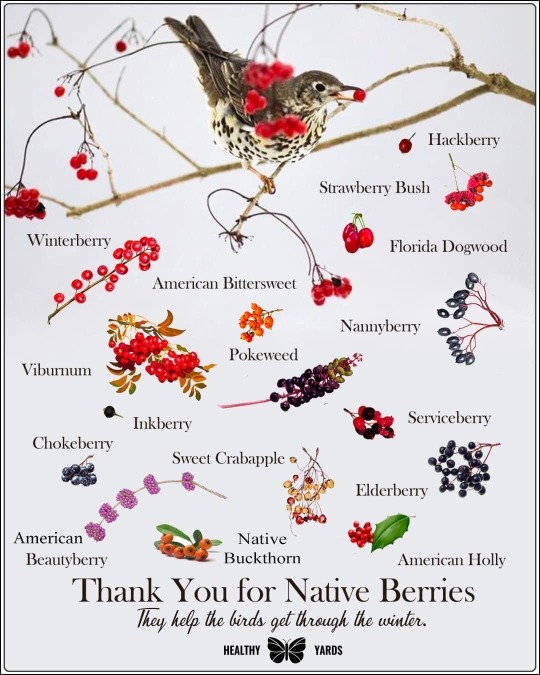

Hey friends, if you have some yard space, and you live in North America, consider planting some of these NATIVE plants in your yards to feed birds in the winter.

Gardening with native plants helps wildlife, you can be sure that you’re not contributing to invasive species damaging local habitats, and… These are all really beautiful plants.

#animals#nature#north america#bird#conservation#birdwatching#gardens#gardening#plants#native plants#environment

337 notes

·

View notes

Text

my biggest pet peeve is how many people in my life (knowing i know things about Plants and Science) ask me if things are weeds are not. stop asking me if that's a weed! weeds do not exist! there are no weeds! it's only a weed if you don't want it there! are you trying to make a pristine flower bed or growing crops? okay, then that might be a weed if you don't want it to be growing there. is it just growing in a random place? is it just growing in a field? then leave it alone, it's just a little guy! it might even be a beneficial little guy, you just don't like how it looks! now in some circumstance it might be a (harmful) invasive plant we should be eradicating, but most of the time i get asked this it is literally just some innocuous plant or flower

i'm for real gonna cry if one more person points to a native wildflower and asks me if that is a weed or not

#i know they just dont know but it's driving me a little mad helpppp#it happens a lot to me because i have a tendency to point out wildflowers and plants that i know how to identify#so i have a lot of people in my life who are like 'oh alyssa can help me with this plant question. is this a weed or not?'#but bestie i'm gonna snap if yall keep pointing to random innocent plants and asking this#it's only a weed if you want it out of your garden. or for it to not cause cracks in a sidewalk or smth i dont know#also i put harmful in parenthesis because dandelions are not native to north america but they're not really harming the ecosystem#my friend asked me this on saturday we were taking photos in the bluebonnets#and there was some other plant in the way of the photo and my friend was like is this a weed? can i pull it?#and im like. we are in a field. that is a native wildflower the same way the bluebonnet is#it's no more of a weed than the flowers we are taking pictures in right now? it just doesnt look as pretty. i just held it aside for the pi#anyway. like i said. pet peeve. this doesnt matter much i am just tired of getting asked it#because i find so many people want an excuse to pull up any plant that they dont like#but we need a lot of these 'weeds' for the ecosystem....if it isnt harming u then just leave it alone....

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Identify American Holly

Click here to learn more about the How to Identify article series.

Name: American Holly (Ilex opaca)

Range and typical habitat(s): Typically southeastern United States, from eastern Texas to the Atlantic coast, southern Missouri, and central Florida to scattered portions of New England. iNaturalist observations also place it in portions of Michigan, Illinois, Ohio, and Oklahoma, showing some expansion compared to the 2014 BONAP map, so its range may be expanding in response to climate change. In most of its range it is an understory tree growing in the shade of larger species. However, in Florida’s scrub habitat it grows as a shrub.

Photo by Derek Ramsay, GNU FDL 1.2

Distinguishing physical characteristics (size, colors, overall shapes, detail shapes): At first glance American holly looks quite similar to the European holly (Ilex aquifolium) so commonly used got holiday decorations (more about the differences between the two below.) It has medium to dark green oval-shaped leaves, sometimes with a yellowish tint, whose margins (edges) have concave curves between sharp points that are regularly spaced; large leaves may reach three inches long.

Photo by Famartin, CCA-SA-4.0-INTL

The American holly’s leaves have a leathery, stiff texture, and may appear waxy, and the underside is paler, often yellow in color. Each leaf has a central vein (midrib) that is depressed, appearing almost like a deep crease. Thinner veins branch off of both sides of the midrib. Some leaves may display smooth margins instead of the more typically spiky ones, especially when they are high enough to be out of the reach of browsing herbivores like deer.

The foliage stays green throughout the year rather than being shed in fall; a given leaf may stay on the tree for up to three years before being displaced by a new replacement leaf. The leaves grow in an alternate pattern along a twig, with each leaf growing a little further along the twig than the last. The tree’s branches and trunk are covered in pale gray bark that is relatively smooth, but may have horizontal and vertical striations, along with various nodes and bumps, and might also play host to white patches of microlichen colonies. Other lichens, as well as mosses, also may add color to the American holly’s bark.

Photo by Krzysztof Ziarnek, CCA-SA-4.0-INTL

An exceptional specimen of American holly can reach almost 100 feet tall when mature, though it grows slowly. Such large trees are generally a century or more old, and the oldest on record was just a few years shy of 150.

The flowers of American holly are small (1/2″ or less across) with green centers and four (sometimes six) white petals that are broad with a rounded end, and whose tips curve back toward the plant. They grow in clusters of several flowers sprouting from one spot. American holly is dioecious, meaning that there are female and male plants; the males tend to reach sexual maturity a few years earlier than the females, but they all are generally reproducing by the age of ten.

When fertilized by insects the female flowers then turn into the well-known red berries. Technically these are drupes rather than true berries, with four seeds apiece, and while they start out green they ripen to a bright red. The berries are popular with birds like cedar waxwings (Bombycilla cedrorum), but are toxic to humans and our pets.

Photo by Douglas Goldman, CCA-SA-4.0

Other organisms it could be confused with and how to tell the difference: Due to their similarity, American holly and European holly may easily be confused at first glance, and both prefer the understory of a forest. However, the European species does not grow as large. The leaves of European holly are darker and have a glossier appearance; the edges may also be more warped where those of American holly lie comparatively flat. Moreover, European holly grows more commonly along the west coast of North America, and is more sparse throughout American holly’s native range, especially outside of cultivated spaces.

European holly (Ilex aquifolium)

Yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria) is another species native to the southeastern North America, particularly the Gulf Coast states and the southern third of the Atlantic coast. It is a much smaller shrub that rarely exceeds thirty feet tall, and its leaves are round with serrated or scalloped edges rather than the pointed margins of American holly. The petals of the flowers may not curve as much as on American holly.

Yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria)

Dahoon holly (Ilex cassine) also grows in the extreme southeastern United States, from Louisiana to the southern tip of North Carolina, and primarily along the coastline except in Florida where it can be found across much of the peninsula. Its leaves are longer and more slender than those of American holly, and the margins are almost entirely smooth except for a series of very small spikes.

Dahoon holly (Ilex cassine). Photo by Douglas Goldman, CCA-SA-4.0

Possumhaw (Ilex decidua) has long, slender leaves with a gently pointed tip and serrated edges. This deciduous plant drops its leaves in fall, unlike the evergreen American holly.

Possumhaw (Ilex decidua)

There are other plants that have similar leaves to American holly but that grow out of its range, such as the various species of Oregon grape (Mahonia spp.) in the Pacific Northwest, and holm oak (Quercus ilex), for which the genus Ilex was originally named.

Further reading:

USDA: American Holly

North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox: Ilex opaca

Missouri Botanical Garden Plant Finder: Ilex opaca

Native Plant Trust: Ilex opaca – American holly

University of Connecticut Plant Database: Ilex opaca

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes or hiring me for a guided nature tour, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#holly#American holly#North America#native plants#Ilex#shrubs#plants#plant identification#nature identification#botany#trees#ecology#conservation#biodiversity#long post#nature#Yule#Christmas#holidays#scicomm

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wish more people would grow plants from seed so they can experience for themselves the amazing individuality of plants.

These flowers are both purple passion flower, scientific name passiflora incarnata.

They were both grown from seed. They came from the same seed packet, they might have even come from the same fruit.

But they are individuals with their own unique characteristics, just like animals.

But instead of being celebrated, individuality and diversity in plants is instead demonized and you are supposed to think that this is a horrible thing and that should be Stamped Out at all fucking costs.

Because God's fucking forbid your flowers look slightly different from the flowers your neighbor has. God's fucking forbid your Apple Tree produces apples that are a different color or have a different flavor.

Gods forbid we not worship the idea of monoculture.

Look at these beautiful fucking flowers. And I bet you tomorrow when I go out to look at the leaves you'll be able to see differences in the leaves too.

[ID: Two photos, each showing a different purple passionflower flower.

The first is extremely pale, with almost white petals, tendrils in the center that are almost white, and most of the color in the very center of the flower where it is purple in a ring around the reproductive parts, and another smaller ring of blue around the outside.

The second flower has more color, with royal blue tendrils, brighter purple in the center, and slightly more color on the petals.

End ID.]

#described images#Rjalker takes pictures#purple passionflower#passiflora incarnata#monoculture is death#plants#wild edibles#North america native plants#Georgia native plants#Savannah native plants#passionflower#passiflora#passionfruit#purple passionfruit#vines#wildlife#photos

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just a couple of great (Eastern) North American native seasonings, which sadly usually get completely ignored outside Native culinary traditions. You've got essentially a different species of Sichuan/sansho pepper, and "Appalachian allspice" which especially deserves more attention.

As discussed here, the young twigs and leaves are also good in teas. Usually to add a nice flavor in with other herbs. You could do worse than to try it with mint or rosehips. Also good to throw some into sumac "lemonade".

Also often combined with native bay leaves to season meats and stews!

(I am honestly not sure what species of bay leaves grow where I'm from, only what it looks like. Not finding much info right now, on the fly. The level of biodiversity can actually complicate things sometimes!)

Another useful Eastern North American plant, which can unfortunately be trickier to grow than any of the shrubby ones above if you don't have good access to the wild stuff:

As mentioned, that also combines great with the spicebush berries. Usually in sweet dishes, but I don't see why it wouldn't work well in savory recipes too. They're suggesting the combo in seasoning rubs. It would probably work well with sumac for that. Throw in some bay leaf and possibly some Sichuan pepper-alike, and you're set! 😁

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rattlesnake Plantain - Goodyera pubescens

Finally a wild orchid! Albeit the most common one in our region. Rattlesnake plantains are commonly found in slightly acidic oak-heath forests near mountain ridgelines. This plant is also a wetlands indicator species however it can grow in both moist and dry conditions (like the mossy ridgeline off the Appalachian trail where I found it).

Rattlesnake plantains are named for the variegated foliage which resembles snake skins, the leaves produce a single stalk which can contain around 50 flowers. This orchid typically spreads colonally via rhizome, like all orchids its 'seeds' require a particular fungal relationship to grow and survive.

In the case of this orchid habitat is very particular, in addition to shady conifer/heath/oak forests, the plant enjoys hummus rich soils and the wood of both white oak and tulip poplars. Given all this context it should cue you in on the fact that this plant will not survive transplant so please do not remove it and place it in your garden.

The Rattlesnake Plantain can be found throughout the entirety of the eastern US and parts of Ontario.

#Rattlesnake Plantain#native plants of eastern north america#wild orchids#goodyera pubescens#plant profiles

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some things in my yard. I cultivated some, others are growing wild.

#nature#certified yard habitat#yard habitat#spring#spring ephemerals#plant native#native plants#native plants of north america#prairie trillium#trillium recurvatum#virginia bluebells#mertensia viginica#Dutchman’s breeches#dicentra cucullaria#Podophyllum peltatum#mayapple#fungi#fungicore

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Goldenrods

It’s nowhere near the fall hayfever season, but I thought I’d PSA anyway.

Hayfever is caused by RAGWEED (Ambrosia artemisiifolia and Ambrosia trifida where I live).

NOT. Goldenrod (Solidago, Oligoneuron, Euthamia). It is impossible for goldenrods to even cause hayfever since their pollen isn’t released to the wind. Goldenrods are beautiful, with some edible parts, some medicinal properties, and middle of summer through fall pollenators love them.

Non-exhaustive list of goldenrods

Euthamia graminifolia (Flat-top goldenrod):

Oligoneuron rigida (Stiff goldenrod):

Solidago bicolor (Silverrod):

Solidago caesia (Blue-stem goldenrod):

Solidago canadensis (Canada goldenrod):

Solidago flexicaulis (Zigzag goldenrod):

Solidago juncea (Early goldenrod):

Solidago missouriensis (Prairie goldenrod):

Solidago multiradiata (Alpine goldenrod):

Solidago nemoralis (Gray goldenrod):

Solidago odora (Anise-scented goldenrod):

Solidago ohiensis (Ohio goldenrod):

Solidago patula (Rough-leaf goldenrod):

Solidago ptarmicoides (Upland white aster):

Solidago rugosa (Wrinkleleaf goldenrod):

Solidago simplex (Spike goldenrod):

Solidago speciosa (Showy goldenrod):

Solidago uliginosa (Bog goldenrod):

The only drawback is that many goldenrod species spread a lot and quickly if you don’t keep on top of those rhizomes. But if you need to fill a space in a relatively short period of time, why not try some in your garden? They’ll grow up green through spring and summer and put on a show in the fall (earlier depending on the species)!

#long image post#goldenrods#hayfever#ragweed#Ambrosia#Solidago#Oligoneuron#Euthamia#flowers#yellow flowers#native species of North America#North American native plants#pollinator plants

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Red baneberry, in western Montana. Regrowth after last year's wildfire. Actea rubra. Ranunculaceae.

0 notes

Text

where is the gardening faction of tumblr, I want to read other people's posts so I can improve my plan to turn front and backyards into pollinator-friendly erosion control water retention food-bearing landscapes

#gardening#sustainability#native plants#native plants doesn't mean north america-specific btw#the aims are p universal and climate change means i need to be planting for future habitat changes too

5 notes

·

View notes