#these are subject to reworking if the settings are RADICALLY different than how i imagined them once the game comes out

Text

THEDAS; a fanmix collection for the settings of dragon age: dreadwolf. listen on spotify: TEVINTER / ANTIVA / ANDERFELS / RIVAIN

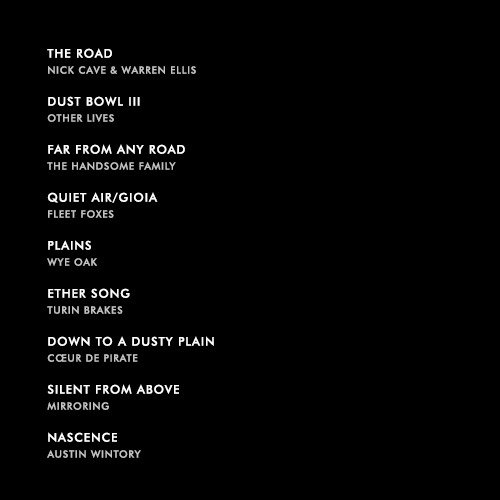

TEVINTER /

opulent, magnificent, but creepy, sinister... corrupt city of darkness and hedonism. immense gothic cathedrals of dark stone tower above the downtrodden masses that scurry beneath. so much history, so much culture, but the blood will never wash out

ANTIVA /

italian, with hints of spain. neighbours sit around in the streets to play guitars or lutes and sing/clap together. beautiful twisting spires, refinement, but there's a seedy underbelly, the stink of leather and the risk of murder- the people are joyful nevertheless- wine, food, song flows from every open window.

ANDERFELS /

vast, open, nothingness. a feeling of pervasive doom, a searching for some sign of the maker in the unforgiving wastelands under an expanse of empty sky. grim soldiers clad in grey march across the dusty landscape, the king has long abandoned his people who must fend for themselves against the constant threat of darkspawn.

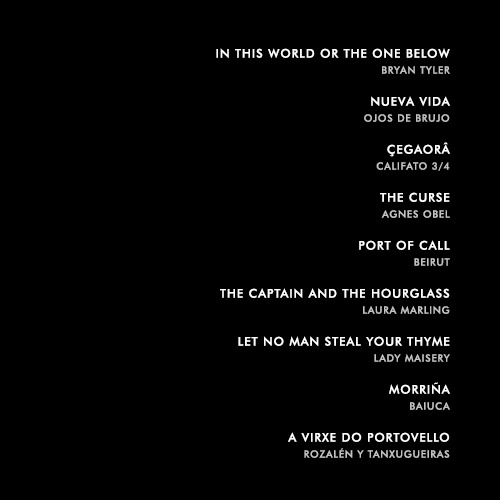

RIVAIN /

their lives are intertwined with the sea. fishing nets, the smell of salt. pirates and sailors come and go, drinking spiced rum at the taverns. and there's an old magic there which sits on the skin, it's as natural to them as breathing. respected seeresses with wrinkled, weather-beaten faces ply their trade under the smoke of burning herbs and cured fish. women sell branches of rosemary on street corners. hints of spanish romani culture and music, also north african and al-andalus.

#dragon age#dragon age fanmix#dragon age: dreadwolf#antiva#tevinter#anderfels#rivain#dragon age 4#minrathous#treviso#these took ages! im particularly proud of tevinter.#with rivain i went for the sort of seeress/hedge witches vibe. but also pirates#these are subject to reworking if the settings are RADICALLY different than how i imagined them once the game comes out#also if there are more settings i will do those too. like kal-sharok fingers crossed#and i may do the settings from the prev games#mix#mine#also lol thats a pic of notre dame burning im sorry

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Cinder’s plan is brilliant

I’ll freely admit that I can be a bit of a negative nancy about RWBY. In fact I’ve partly made my blog off of it, alongside sharing other people’s content. But I like to think that, going off the responses I get to my analysis posts, that they get a good reception. So today, I’d like to try something different and do some positive analysis of RWBY.

Volume 3 has become known as the highlight of the show for good reason. It’s the volume that brings together the past two years and concludes the first act of RWBY’s story on a truly desolate note- the heroes have failed and only narrowly pulled victory from the jaws of defeat, while the villains nearly got away without a single notable casualty, their plan having successfully gone off without a solitary hitch.

And what a plan. Cinder Fall’s nefarious schemes across the prior two volumes come into the forefront and utterly cripple Beacon. In one semester, she plants the seeds of a multinational world war, cripples the world’s communication network, kills countless citizens and Huntsmen, secures the powers of a demigod and gets away with killing one of the most powerful men alive. Not bad at all Cinder.

So that’s the purpose of today’s post. I’m going to break down, in my opinion, why I think Cinder’s plan to destroy Beacon was nearly full-proof and why it’s a genius scheme. Buckle up, I get wordy.

Cinder’s plan has the least presence in Volume 1, though that’s more due to Volume 1 thinking it was too cool for things like plots and overarching narratives. But more seriously, the Volume 1 part of the plan needed some quiet reworking after Cinder’s power source was changed.

See, Cinder wasn’t originally a Maiden. In fact, the Maidens only existed after Volume 2 had wrapped. CRWBY have been quite open about this plot change, as it was one Monty came up with prior to his untimely death. Cinder instead would have simply been a powerful Dust Mage who was using the Dust Roman stole to gain power for herself and the White Fang. In all honesty going from using Dust-infused clothing to the Maiden powers was one of the smoother retcons in RWBY’s history, especially compared to some of the more egregious incidents like the handling of Aura. So Cinder quietly went from a Dust user to someone with half the powers of a Maiden Ultimately since most of the major elements in Cinder’s scheme such as Ironwood, the transfer students or the mech army are present, Cinder herself has little to do in Volume 1 after saving Roman and looking Mysterious.

And that’s the point. Roman’s part of the plan is to be as attention-seeking as possible, Cinder’s plan relies on Roman getting all eyes on him as he steals as much Dust as he can carry. Not only does he deplete reserves that go into the White Fang and her own pockets, but it also creates distrust in Vale, brewing up tensions that the White Fang use to radicalize more people and bolster their numbers.

Volume 2 marks the point where Cinder begins making deliberate steps on her plan. Now that Ironwood (and his ships with all their robots and big guns) have arrived along with the transfer students now entering Beacon, Cinder has the perfect cover to slip into Beacon undetected thanks to the security nightmare that is the Vytal Festival alongside Mercury and Emerald (and Neo I suppose), and she wastes no time with setting the stage. Mercury is immediately set out to analyse the most powerful fighters at Beacon and figure out their Semblances ahead of time. Emerald meanwhile played social butterfly, getting in good with some of the teams and sneakily learning who they were sending forward ahead of the matches. And Neo... was busy helping Roman and likely only appeared in the first episode of Volume 3 so people wouldn’t ask who the fourth person on Cinder’s team was. This was mostly a three-man mission after Cinder got to Beacon while Roman and Adam prepped for the bigger events.

Even here, Cinder was already setting up three chess pieces of her own in her master-stroke to take down Ozpin: The assaulter, the murderer and the patsy. Barring the murderer (who was almost always going to be Pyrrha because Cinder loves dramatic irony and nothing’s better than a champion helping cause the apocalypse), these roles could have been taken by nearly anyone. Once Cinder knew which team members would advance, she could play around them. Hell, if Cinder hadn’t learned about Penny’s robotic nature, things could have easily been set up for Pyrrha to kill someone else instead-

Cinder even manages to spin a school dance in her favor. It may seem on the service like some harmless fluff between the big battle episodes, but the dance arc episodes are made critically important through Cinder’s infiltration of the CCT and planting of Watts’ Queen Virus, alongside the episodes themselves letting us see Mercury and Emerald’s parts of the plan. With this in play along with the White Fang, Cinder had half the work done for the Fall of Beacon before RWBY even had a clue she existed.

When you’re this confident in your plan (and when you don’t ever skip leg day) you earn the right to make some sick flips

Talking of RWBY, it’s interesting how they never really had a chance at stopping Cinder. Thanks to Roman hogging the spotlight, RWBY genuinely think they’ve stopped his plans entirely after the Breach. Qrow has to tell Yang and Ruby that yes, crime’s down, but every hydra’s got another head. Cinder basically sets Roman up as a patsy, and I think it’s safe to say she didn’t really care if Roman lived or died after the Breach. If he happened to live, then she could use that and send Neo to break him out before they caused more damage during the Fall, but it wasn’t a be-all-or-end-all if Roman died early. Regardless, the Breach was a giant distraction, a gambit that Cinder intended to lose. It was one that RWBY jump-started early, but the results were ultimately the exact same.

There was no hopes of the Breach being enough to take out Beacon, even if Cinder, Emerald and Mercury had personally joined the fight. Its goal was always to make Ozpin’s leadership look incompetent. Under his watch, with the Vytal Festival looming on the horizon, a massive terror attack occurs and Ozpin is left looking like a headless chicken. People being to distrust Ozpin, the council gives James new privileges and more emphasis is placed on the Atlas military for security reasons. Which, with the Queen virus in place, is exactly what Cinder wants. The more androids on the night of the Fall, the more images of Atlas mechs firing on civilians to fill the nightly news. The Breach was never Cinder’s endgame- to quote @alexkablob, it was just Act 2.

With Volume 3, the stage is set. Once Ironwood connects his scroll to the CCT, Cinder has access to all of his personal files, and that gives her the cherry on top for her Murder Souffle. With Penny, Cinder has just been given the prime target to set up as the fall guy for the Fall of Beacon.

Also on the subject of the Vytal Festival, can you imagine what it must have been like to be the first year team that had to fight Team CMSN? Two trained assassins, a master illusionist whose stealth skills make her just as lethal as the assassins, and a 23-year-old posing as a teenager in leather pants who didn’t even use a weapon to kick your ass. The whole “How’d your team do?” Emerald flashes back to her team ripping some first years a new asshole “... Really well.” joke is one of the best gags in all of RWBY BTW.

Lady can you CHILL

With her hacking of the CCT, Cinder basically just needed to do one fight and then she could sit back and enjoy the fireworks. She had her Actor in Mercury, and after watching the Vytal matches, it was easy to find someone with a short temper who the crowd could believe was willing to shoot an injured man after he’d already lost, breaking his leg. Penny was the perfect target to die, but make no mistake, Cinder would have used anyone else as the victim. Heck, in an alternate timeline, whose to say someone like Ruby wasn’t the one gutted on Pyrrha’s spear in the Vytal finals?

Pyrrha, however, was always going to be the Murderer in this little stage play of Cinder’s. Cinder likely pegged Pyrrha as one of the candidates to become the new Fall Maiden early on, and if she hadn’t before the finals, seeing Pyrrha and Ozpin enter the CCT was the red flag she needed. Pyrrha was the Invincible Girl, the one everyone knew as a hero, greatest Huntress of her generation, and she was someone who it wouldn’t look suspicious if she curbstomped all of her enemies. Why else does JNPR fight BRNZ, a team with at least one electrical weapon, in an environment that spawns thunder? Neptune’s weapon also would have likely supercharged Nora, so the SN vs NP match that was cut for time would have had a similar outcome (including another water biome). Pyrrha was really the perfect person to take to the finals, and her polarity Semblance just made Penny that much better a target.

To further my point, here’s a stellar post made by @alexkablob, with the relevant part quoted:

But she (Cinder) 100% wanted Pyrrha, specifically, to be the one who killed her opponent in the finals, and she wanted that as early as volume 2. Because Pyrrha is the Invincible Girl, she’s the greatest huntress of her generation, she’s the world’s icon, she’s a hero in the making, she’s on the cover of every Pumpkin Pete’s Marshmallow Flakes box. And Cinder wanted to take that image and tear it down for the entire world to see.

So when the finals came around, after the crowd had already seen barbarism from Yang, Pyrrha’s shoddy mental state after the last few days combined with Emerald’s Semblance to make a show no one ever forgot.

Once the Fall kicked off, everything went straight to hell in a handbasket. The mechs went rogue, Adam’s White Fang brought Grimm in and caused chaos while an army of Grimm charged Vale. Cinder cut the broadcast on Atlesian mechs firing on civilians, all while delivering a monologue that nailed home just how utterly screwed everyone was. The Huntsmen were scattered, and the fleet was firing on itself thanks to Roman.

Which let Cinder lead Ozpin into the final stage of her plan.

Cinder needed Ozpin to come out onto the battlefield, so that the CCT would be unguarded. Ozpin would be forced to choose between the people he swore to protect, the citizens and Huntsmen who he tries to care for as people and as children, and a sickly, dying woman. If he wasn’t there, her chances of finding Amber and killing her skyrocketed. The only way it could be better was if Ozpin basically led her right to the Maiden-

Well, well, well. YOU HAD ONE JOB, JAUNE.

And with that arrow, Cinder wins. She’s got this in the bag, she just got the full Maiden powerset, Ozpin is alone because his need to put The Men First meant that he sent Qrow and Glynda into the city instead of staying with him to protect Amber and the Vale Relic. As an aside, look at their faces.

As @ozcarpin pointed out in this post that I took some notes from:

The logical option here is to double down on protection of the Relic and Amber, a few more casualties cannot hope to compare to the destruction that Salem can wreak with a maiden on her side. But Salem knows what option Ozpin will pick, what he can’t help but choose again and again no matter how many times it does him over.

Glynda and Qrow come to him, looking for direction amid the panic, torn between what they know are their duties, and he tells them to leave, to go to the city. Their enemies are coming for the vault, and they don’t know how many of them there are, how powerful the opposition might be, but Ozpin chooses to go alone. Cinder later calls it arrogance but Salem knows better.

Even knowing that he’s dooming them all, even knowing that he’s likely marching to his own death, Ozpin will always pick the safety of his people above all else.

And in that moment, all three of them knew it.

Cinder makes short work of Ozpin after this, even with all of his experience she immolates him. After that, before going to secure the Relic, she returns to Ozpin’s office to lord over her victory. And gee, it’s almost like Cinder’s big weakness is that she’s prideful and will always take time to gloat before confirming the mission’s complete! Like, seriously, if Cinder just grabbed the Relic and snuck out of Vale with Em and Merc, she’d have been clear. Roman and Neo would have likely died and taken a lot of the heat posthumously and Cinder would have had perfect checkmate.

But she had to go to his office, and she had to gloat. Meaning she had to fight Pyrrha and had to kill her, meaning she had to take Ruby’s Silver Eyes right to the face. Because you can have the best damn plan, but if you let your ego control you, the best laid plans often go awry.

In conclusion, Cinder’s plan throughout Volumes 1-3 is perfectly laid out and designed in such a way that Cinder was able to make rapid adjustments on the fly. Thanks to using Roman and the Breach as scapegoats, she diverted attention away from her (in spite of Qrow nearly seeing her face when she went for Amber), her underlings were able to assist in pinpointing who would be fighting and when, and Watts’ Queen Virus let her wreak havoc on Beacon when the time came. Cinder’s plan is genuinely a well-written masterplan; the pieces were on the board right from the start, but only in hindsight did we see everything after all we knew and loved had come crumbling down around us. Or to put it another way:

The shining light will sink in darkness

Victory for hate incarnate

Misery and pain for all

When it falls...

Thank you for reading.

#rwby#cinder fall#pyrrha nikos#ozpin#rwby analysis#roman torchwick#mercury black#emerald sustrai#james ironwood#qrow branwen#penny polendina#yang xiao long#glynda goodwitch#rwby volume 1#rwby volume 2#rwby volume 3#character analysis#neopolitan#i actually like roman but jeez in hindsight roman is SUCH a patsy#when it falls

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

So, the more I think about The Last Jedi, the more problems I have with it. I came out of the theater thinking I loved it but had a few quirk moments that really annoyed me, but as time has gone on I’ve reached this point where I simultaneously love it and hate it, and I’m just going to embrace that and both love and hate it in equal measure.

And because of this, I have a lot to say and I’m just gonna go ahead and post it. Obviously, under a read more cus I’m not gonna bother attempting to hide spoilers. This may ramble some too, but whatever. Time for Starcourse!

The first thing I have to make clear about The Last Jedi is, to me, it did not feel like a Star Wars movie. By this I mean that the way it was shot, the way it was written, the way it is placed inside the whole cinematic series just doesn’t feel like a Star Wars film. Some of this is on a meta level: it begins mere moments after the end of The Force Awakens, and that sets it apart from all the other films, which have massive gaps between them.

The Last Jedi and The Force Awakened could be one movie, in many ways, and that’s not really a good thing, because regardless of anything else, it begins to break down the feel of what a Star Wars movie is. However, the issues that make me say this go on further. On a technical side, the scenes don’t FEEL like a Star Wars movie. There are many things to say about George Lucas but I feel the cinematography in his films was, at the least, distinct. And that distinctness left a clear impression.

But The Last Jedi doesn’t really have that. It’s shot radically different than other films in the series, I felt like. And so that contributes to the feel that it’s a movie using Star Wars props and settings and characters, but yet not feeling like a Star Wars Movie, if you catch my meaning.

Another issue is music. In prior Star Wars films, the music is as much a part of the scenes as any other element, and it stands out in my head. I can hear the music when imagining the scenes, the music is distinctive because of how the scenes are shot and scored. I don’t remember any of the music from The Last Jedi, and while I’m sure it’s actually fantastic it just... didn’t capture me the same way. I’m not sure why yet, and it’ll take multiple viewings to really grasp it probably.

Moving on, the way it’s written also doesn’t feel Star Wars. I mean this in two ways: it’s pacing is all over the place, it’s dialogue feels out of place, and the humor, while occasionally actually good, doesn’t feel like Star Wars humor. I want to be clear that for some of these, much like the above comments, these are not necessarily reasons why it’s a bad movie, but perhaps why it may be a bad Star Wars movie. Other cases, though, absolutely mark it out as just bad writing regardless, but I’ll touch on that in each case.

Firstly, the humor. There is a lot of attempted humor in this film, some which works better than others. I’ll admit, while I found the opening bit with Poe and Hux amusing, it felt utterly out of place. It’s basically an extended version of the scene from The Force Awakens, which itself felt out of place, particularly given the context. In that, we literally just saw a mass slaughter of a village and you’re now doing a comedy bit. Not only that, Star Wars doesn’t really do comedy bits. The humor in Star Wars is delivered in different ways, but the timing is also key. This is akin to Padme cracking wise after Anakin talk’s about how he killed all the Tusken Raiders.

In The Last Jedi, there is less of a poor timing, but the entire bit robs the film of momentum, and also serves to render Hux into a buffoonish character (which I’ll touch on later,) and it just doesn’t feel like Star Wars. It’s funny, but out of place. In a lot of ways, I include Luke’s flick of the saber (though I think that also works well enough) but even more so his dusting his shoulder off. The former at least serves well as a shocking sort of moment. The latter serves to break the drama and scale of it all. Included in this, though, are Poe’s ‘permission to jump in an X-Wing and blow stuff up’ line, which again, just feels... out of place given the situation. It robs the scene of seriousness.

Which is sort of the major issue; I don’t feel like The Last Jedi takes itself seriously. Or, at least, it doesn’t do so consistently. Lines like that, or then lines like Rey when Kylo shows up in the mind link shirtless, and so on just serve to make it feel... less serious. Some might say it grounds things, but that’s the big issue: Star Wars isn’t grounded. It’s a Space Opera, it’s epic fantasy in space, and The Last Jedi doesn’t feel epic. Indeed, the whole film seems... small.

This is as much an issue with The Force Awakens, though, in that it really fails to establish the sort of scope of the First Order, and the Resistance really comes off as minor as well. It continues in TLJ though in that it really just never feels like things are ‘a big deal.’ We’re told of things but it’s very mixed on actually showing, I guess? Or the showing just... falls flat.

Linked to the issue of it taking place right after The Force Awakens, the whole film takes place in, arguably, the course of, what, a day? A few days? It’s hard to tell. At first, I thought it was only literally about a day because they literally give hour counts on their fuel but Rey is with Luke for what seems like a few days. Yet the pacing is such that thing seem both too slow and too fast. There is no real sense of time in a lot of the scenes, and that really causes issues with the pacing. And also with things like Rose and Finn, because we’re talking about people who just met at most a few days ago, on less then stellar circumstances, and then things progress so very quickly, and it seems... out of place.

And then we get things like the entire Casino subplot, which irks me on many levels. First, the intentional aping of the Cantina introduction with a reworking of the ‘scum and villainy’ line, the panning around of all these fantastic and weird aliens and all, and whatnot. Sort of clever, but it just gets hamfisted when Rose goes on to imply that the only way to get this rich is arms sales. I damn near groaned out loud at that moment, because this is a movie by Disney telling me the only way to get rich is arms sales. Eat my ass, Disney! You mean to tell me there are no Space Googles or Space Comcasts or Space Disneys? It doesn’t even make sense!

Particularly not when we just had a bunch of movies about the Trade Federation and the Banking groups and other members of the Confederacy that were rich, and thus had a lot of arms to defend their financial interests, rather than being rich BECAUSE of their arms. And then we have the whole stampede through the city, and how great it was to stick it to them... yet are you trying to imply EVERYONE in the city, all the stuff you broke only belonged to rich arms dealers who are assholes to kids and kick puppies or something? I get that Finn is new to this, impressionable, and so on, but he went from being amazed and loving it to literally being glad they smashed stuff up.

Also, the alien dude with the southern accent was terrible. Should have let it be an alien language and just let us UNDERSTAND through VISUAL STORYTELLING. You know, like we got with the Kubaz who ratted out Luke and Han and them in A New Hope. Indeed, not doing this makes the whole universe feel small. Aliens just aren’t used right.

And honestly, I’m just going go through a long string of ‘why’ questions that really irked me, in no particular order or organization. These aren’t all equal complaints, but they’re just things that got to me...

Why are the bombers literal bombers, when we had Y-Wings and B-Wings in the other movies that clearly were strike craft with heavy payloads for the sort of thing they were doing. Why would you ever have a literal ‘bomber’ in space, given there is no gravity for the bombs? That whole sequence also makes the Resistance feel very very small, because it doesn’t feel like a lot of ships get blown up but apparently that’s their WHOLE bomber wing?

On that subject too, Poe gets hemmed up for disregarding orders and taking out the dreadnought, abet at heavy losses, to the point that he gets demoted and the Vice Admiral (who, by the by, I really hate the design of. Leia looks at least paramilitary in outfit, but she is just straight up wearing a dress and it just feels... out of place) treats him pretty badly despite later saying she actually understood and likes him, but later, when they get caught due to their hyperspace tracking stuff, it becomes utterly apparent that it was absolutely a good thing that Poe did what he did cus had he not, the Dreadnought could have just blasted them from space. Instead, they manage to outpace them because Poe’s desperate gambit took out the ship that could have blasted them due to its superweapon guns.

On that subject, how the hell does ‘out of range’ in a vacuum work? Like, I guess the argument is the energy dissipates but how the hell can they maintain that speed that always keeps them at range yet never outpaces them? And why doesn’t the supermassive Snoke battleship have those same guns? (Also the way these ships are introduced is meh, not like how they did the like Super Star Destroyer in the original trilogy, but that gets back to how the movie is shot and not feeling right.)

And how the hell does on person manage to fly that massive Mon Cal ship, anyway? How come the massive damage done by it ramming them going into hyperspace is played up yet apparently the ships are still mostly functional, at least enough to get folks down to the planet and all? That felt very odd...

And on that subject, the planet! The whole plan seems so very odd. How the hell did they manage to fly so far on sublight speed to get in range of this planet that just so HAPPENED to be an old rebel base (which only has one way in an out, for some reason,) and somehow no one saw these planets? Or, you know, the SUN it must be orbiting? And why not TELL people this plan, like what was the purpose of KEEPING IT SECRET? Particularly not when you have a hotheaded and brash guy who already is on notice for disobeying orders he thought was wrong, and you think your little stern talking to was gonna shut him down? Really?

And the irony is, Poe got hemmed up for his scheme to take out the dreadnought, which ended up being not merely good but necessary. But no one really talks about how his scheme to shut off the tracker, which led to the First Order becoming aware of the transports because the slicer (cus he’s a slicer, not a codebreaker, again, use the damn Star Wars-y terms, film!) ratted them out, and that leads to, what, like 90% of the Resistance dying? For that matter, how big IS the resistance, cus you seem to have enough folks to fill the trench yet apparently everyone fits on the Millennium Falcon in the end?

And why the hell is Finn piloting one of those speeders anyway? He’s not a pilot, we’ve literally been shown he was figuring out how to operate the guns on the TIE Fighter and Falcon but he explicitly NEEDED a pilot, that’s why he rescued Poe, after all, and that’s why Rey piloted their escape. If anything, he should be with the ground forces cus that’s his expertise. And speaking of expertise, how is it that this one guy who was a janitor apparently was a janitor for Starkiller base, and thus knows his way around that in a complex and technical way, and ALSO knows his way around Snoke’s superbattleship, in a complex and technical way? That seems... weird.

Like, I liked when Rey could navigate Starkiller base cus she was familiar with Imperial tech and designs from crawling around in them her whole life. Finn being that knowledgeable seems... sort of weird.

On the earlier thing, why is Hux portrayed in an almost buffoonish way? It robs him of any menace. His other officers seem more competent, and he just seems... very very NOT competent, and it sort of messes things up. It robs some menace from the First Order when he’s the on in charge.

Why does everyone seem to get to where they’re going instantly? Travel time seems simultaneously a plot point and non-existent.

Why introduce Snoke as this strange character if you do basically almost nothing with him? Like, the Emperor at least had build up and then sort of mattered. And yeah, they could reveal more in the third film but that’s... really not helpful for THIS film feeling odd. And then the biggie: Rey and Kylo. And I don’t mean any sort of romantic overtones cus I actually like how they handled that, with Rey conclusively saying fuck no to Kylo and thus squashing that as a thing (though I know some folks refuse to see it that way,)

What I mean is that Kylo’s ‘let the past die, kill it, and start over’ ideology is basically the exact same thing that Yoda is telling and what is happening with the Resistance and Jedi. Which, honestly, is itself fairly stupid and I object to this idea that somehow she already knows any of the good things in ‘old religious texts’ and whatnot, because of broader implications, but if you’re gonna have that message then why show that actually they saved the books and their on board the falcon at the end.

Honestly, there is probably more that I’m missing but this is the general thrust of things. I want to be clear, though, I actually liked a lot of it. Finn is still the best character, even if put in situations I don’t actually totally agree with. The humor was legitimately funny, and sometimes actually fit well. BB8′s constantly trying to pluck the ‘leaks’ and then using their head to do it felt both funny and very Star Wars-y; I can see R2 doing something like that. (though, as a note, that R2, C3P0, and Chewbacca all get basically no real place again sort of stands out. R2 and C3P0 being major aspects of the Star Wars franchise is sort of a big deal. They’re supposed to be there, and they’re really not in this.)

But the fight sequences are pretty damn good, with a few minor hiccups, and like I really enjoyed the film while watching it. I’ll certainly watch it again, but there is so much that I feel also was just in JUST to tweak with people and Rian trying to play gotcha games, and it, at the core, just didn’t feel like a Star Wars movie. It’s a movie using Star Wars trappings in ostensibly the Star Wars universe, but it just...

Didn’t feel like Star Wars.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adam Tooze in the LRB

I learned a lot from this early April piece by Adam Tooze in the London Review of Books on the economic fallout from the coronavirus crisis.

However, I also have my quibbles, particularly over its ending:

And once the crisis is over? What then? How do we imagine the restart? … Will the world economy rise from the dead? Are we going to rely once more on the genius of modern logistics and the techniques of dollar-finance to stitch the world economy back together again? It will be harder than before.

Any fantasy of convergence that we might have entertained after the ‘fall of communism’ has surely by now been dispelled. We will somehow have to patch together China’s one-party authoritarianism, Europe’s national welfarism and whatever it is the United States will be in the wake of this disaster. But in any case, for those of us in Europe and America these questions are premature. The worst is just beginning.

In that last paragraph, note Tooze’s rhetorical trick. First he baits us:

We will somehow have to patch together China’s one-party authoritarianism, Europe’s national welfarism and whatever it is the United States will be in the wake of this disaster.

Then he changes the subject:

But in any case, for those of us in Europe and America these questions are premature. The worst is just beginning.

So actually we don’t have to think about what he just said, as we’ll be too worried and busy coping.

I think this is a shame. Because this means he glosses over some fairly bold assertions – ones that could do with some further scrutiny.

In the previous paragraph, he elides two rather different matters:

Are we going to rely once more on the genius of modern logistics and the techniques of dollar-finance to stitch the world economy back together again?

The answer to whether we can rely once again on modern logistics is surely yes. Supply chains will continue to supply stuff for us through and beyond the crisis; some of them may change, but many won’t. So, broadly, how we’ve set up things for goods to come our way will continue. Why? Because there isn’t an alternative. Sports shoes, iPhones and what-not will continue to be made in Asia and brought to us; food will continue to be grown around the world and brought to us. Maybe various medical suppliers will be made nearer home; maybe the US-China trade war will rework the ways in which electronic goods come our way; maybe there will be will be less immediate demand for fashion and smartphones. But the machine that supplies us with goods hasn’t gone away, nor will it.

The answer to whether we can rely once more on dollar-finance is I don’t know. It could turn out to be yes, as like supply chains, there isn’t an obvious alternative. But it could also be no, as it is possible – just – to envisage a world where people are no longer confident that the US economy will continue to expand.

There are of course other, more radical, possibilities that we could take in the shorter term. But who, at times like these, would want to risk something totally new and untested? We don’t know enough about the things we are familiar with; trying the unfamiliar would be a jump into the dark for far too many people.

Looks like there’s a big restitching job ahead.

0 notes

Text

Susan Reynolds Whyte, Health Identities and Subjectivities: The Ethnographic Challenge, 23 Med Anthro Quart 6 (2009)

Abstract

The formation of identity and subjectivity in relation to health is a fundamental issue in social science. This overview distinguishes two different approaches to the workings of power in shaping senses of self and other. Politics of identity scholars focus on social movements and organizations concerned with discrimination, recognition, and social justice. The biopower approach examines discourse and technology as they influence subjectivity and new forms of sociality. Recent work in medical anthropology, especially on chronic problems, illustrates the two approaches and also points to the significance of detailed comparative ethnography for problematizing them. By analyzing the political and economic bases of health, and by embedding health conditions in the other concerns of daily life, comparative ethnography ensures differentiation and nuance. It helps us to grasp the uneven effects of social conditions on the possibilities for the formation of health identities and subjectivities.

The ways that health is invoked in the formation of identity and subjectivity is a fruitful field for anthropologists, whether or not they consider themselves “medical.” That is because they touch on fundamental issues in social science: the workings of power in relation to social differentiation and senses of self and other. In this article, I review some of the theoretical issues at stake here, to underline the contribution of detailed ethnography to these discussions. In the interest of oversight, I will radically simplify by distinguishing two approaches: the focus on politics of identity and the concern with subjectivity and biopower. Both themes are part of a wider intellectual discussion in cultural studies, sociology, political science, history, and philosophy. Anthropologists have found inspiration here, but the commitment to comparative ethnography means that our contributions have problematized both approaches. We are concerned to specify: What particular political, historical, technological, and cultural circumstances facilitate, shape, and constrain the working of health identities? How and when do specific situated concerns move some social actors, but not others, to think and act in terms of health? What resources are at stake?

Identity Politics

The link between health and identity is not a new topic for social scientists. Goffmanput it firmly on the agenda with his magnificent essay on stigma from 1963. Health issues—disability and mental illness—provided some of his most striking examples of the management of spoiled identity. Sociologists working with labeling theory in the 1960s and 1970s emphasized the formative effects of diagnostic practices for people who learned how to be different after being so identified by authorities. In anthropology, research on spirit possession and initiation to the role of healer, shaman, or diviner often focused on identity and its transformation. Ethnic or national identity, indeed identification with any kind of imagined community, can be linked to therapeutic systems. Pride in, or allegiance to, Ayurveda or African traditional medicine or homeopathy is a kind of medicinal cultural politics that places a person by expressing loyalty to one system in opposition to another.

Identity is about similarity and difference between selves and others. But as Richard Jenkins points out, it is the verb to identify and not the noun identity that opens the richest analytical perspectives. The verb makes identity a process that happens between people. He quotes Boon to the effect that social identity is a game of playing the vis-à-vis; and he underlines that identities work and are worked (Jenkins 1996:4–5). It is this practicing of identities with an eye to consequences that forms the first part of the opposition I wish to explore.

Identity politics is about the revaluation of difference: the assertion of a difference that had been disvalued, the witnessing of discrimination, and the struggle for recognition, rights and social justice. Sometimes called the politics of difference or of recognition, it is at once personal and collective. As noted in an early article on mental illness and identity politics: “insofar as they seek to effect changes in public policy, [such social movements] consciously endeavor to alter both the self-concepts and societal conceptions of their participants” (Anspach 1979:766).

Identity politics is a child of the 1960s and very much a part of U.S. social history. The philosopher Richard Rorty traces a transformation in U.S. leftist thinking from the pre-1960s Reformist Left to the Cultural Left that marked the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. Where the old Left was concerned with economic injustice, the new one took on prejudice. As Rorty puts it, the new “politics of difference” was about stigma and humiliation, rather than greed and money: sadism not selfishness (Rorty 1998:76–77). He thus sets up a dichotomy between a politics of recognition and a politics of redistribution (Fraser 1998).

From the civil rights movement to Black power, feminism, gay rights, and multi-

culturalism, the politics of identity put recognition of difference on the agenda. Recognition was a first and necessary step toward action for change. As Terence Turner argued concerning multiculturalism, identity politics was about “collective social identities engaged in struggles for social equality” (Turner 1993:412). There is always a possibility that politics of identity can fetishize difference and tend toward separation, but it can also make a critical contribution to politics in the sense of discussion and action among a plurality of people.

In the arena of health, the disability movement is perhaps the clearest example of identity politics. The militant campaign for disability rights in many countries was accompanied by an increased sensitivity about identity and respect, as expressed in language, law, and even architecture. In the academy, the field of Disability Studies emerged with a strong focus on recognition, personal experience, and the social and cultural processes of disablement. The interest in identity spread beyond the “classic” motor, sensory, and intellectual handicaps to encompass obesity, chronic illnesses, infertility, old age, and even traumatic experiences like being raped or tortured (see the range of contributions in Ingstad and Whyte 2007).

There is often an overlap between movements making claims for justice from the larger society and support groups for people sharing a common problem. Between the two poles of identity politics, the collective and the personal, different balances are made between common political efforts and individual endeavors to rework a devalued identity. The whole continuum of health rights movements and support groups is better represented in the global north than in the resource-poor settings of the south. But scholars are beginning to examine the emergence of identity politics of health in developing countries, and their research can provide a needed comparative perspective.

One of the best studies from Africa is a historical work on leprosy and identity in twentieth-century Mali (Silla 1998). Silla shows how the establishment of leprosaria by missionaries and later the implementation of vertical treatment programs by WHO facilitated the transition from commonality to community. People with leprosy left their rural homes to move near clinics and remained in town with others like themselves after being cured. Silla shows that a group identity as lepers developed out of an interplay of institutional catalysts, a critical mass of similarly disabled people, and common interests in survival strategies (including begging). In 1991, a formal association of leprosy patients emerged to overshadow earlier informal groupings, such as the one formed by women beggars. The new organization had more educated leaders, and it joined the national disability federation and took up an agenda of disability rights.

I and Herbert Muyinda (2007) trace the mobilization of people with mobility disabilities in two border towns in eastern Uganda. Accused of being smugglers, they counter by asserting their rights as disabled people. Unlike the situations of lepers in Mali described by Silla, or that of mobility-disabled people in Western Tanzania studied by Van den Bergh (1995), there were neither treatment institutions nor training programs that drew disabled people to town. They came seeking economic opportunities they did not have in their villages. People used connections with relatives and friends to make a start in town, and to get enough cash to obtain their most essential capital: a hand-crank tricycle. Physical mobility was necessary for social extension and political mobilization. Getting a life in the particular niche of cross-border trade that they were exploiting brought them together around common interests; they formed an association to support those interests and took advantage of the national requirement that disabled people be represented on district and municipal councils. Although the political organization of people with disabilities is countrywide, some people identify themselves as disabled far more actively than others. In Busia and Malaba, men with motor impairments form the core of organization, whereas women and people with other disabilities are far less active. We draw connections to the political economy of the border region, to the role of donors in supporting rehabilitation projects, and to Uganda's policy on disability.

Both the lepers in Mali and the mobility-disabled people in eastern Uganda came together around common interests in particular local worlds. From there they made contacts with national and even international organizations. They connected with people from outside their immediate localities who passed on new ideas and new social technologies that they could use in their own local situations. Even in European countries, where institutions and organizations have been in place for some time to provide services or advocate for people with disabilities, the importance of grounding fellowship in specific projects and experiences of commonality should not be underestimated, as shown in Priestley's work (1995) on an organization of blind Asians in Leeds.

These examples of identity politics fit well with current paradigms for health and development that emphasize the “rights-based” approach. Whether the theme is sexual and reproductive health, disability, or health care services, people are to be seen as citizens having rights, rather than mere beneficiaries, clients, or customers. They are to make claims and participate in decisions that affect their lives. Their own understandings and actual struggles, not the programs of outside agencies, should be the basis for change (Institute of Development Studies [IDS] 2003). But of course their own understandings include their perceptions of the possibilities and rationalities of programs. Ethnographic approaches to health identity politics often focus on the way people use agencies and discourses to make claims that further their own projects and agendas.

Ethnography does not assume identity politics but questions the conditions for its existence, as exemplified by a study of diabetes in Beijing by Mikkel Bunkenborg (2003). In the liberalizing political economy of China, where multinational drug companies play an important role in providing information about diabetes, patients become consumers and are rather left to their own devices to manage their condition. They feel unjustly treated, and they carry a heavy economic burden in having to finance their own treatment while they also risk losing their jobs. Bunkenborg describes the informal circles of fellow patients who support one another and pass on knowledge. But he doubts whether there is a politics of identity at work here. It is not a case of diabetic identity as a basis for a social organization of equals with common interests making claims for recognition and rights. Rather he sees these networks as part of the politics of the self in which people cultivate moral character and interact in differentiated and more hierarchical networks of particularistic relations. This is not just a legacy of Confucianism, but a function of the difficulty of forming civil society organizations in China, the insecurity of an unregulated market, unequal access to health care and knowledge, and the management of a disease that requires discipline of the self (Bunkenborg 2003:89–91). Bunkenborg's analysis leads on to the second way of approaching the link between health and identity, which is perhaps better phrased as a relation between health and subjectivity.

Biopower

Michel Foucault's influence in problematizing health and power has been enormous, although perhaps more profound for medical sociology than anthropology. His concept of biopower focuses on discourses and practices that work both at the level of the self and at the level of whole populations. In this sense, it is relevant to consider biopower in relation to health and the politics of identity. However, unlike identity politics, biopower approaches are not generally concerned with explicit political action and debates about social justice. Rather they point toward the much more subtle shaping of subjectivity, of assumptions and bodily practice and attentiveness. Knowledge, technologies, and control are the watchwords.

Inspired by his writings and deeply immersed in the significance of new developments in biological science, Paul Rabinow (1996) launched the term biosociality to capture the ways that biological nature, as revealed and controlled by science, becomes the basis for sociality. His examples are the ways that genetic testing and other kinds of medical technology yield social–biological classifications that are practiced in new kinds of organizations.

I will underline … the likely formation of new group and individual identities and practices arising out of these new truths. There already are, for example, neurofibromatosis groups whose members meet to share their experiences, lobby for their disease, educate their children, redo their home environment, and so on. That is what I mean by biosociality. [Rabinow 1996:102]

Whereas an older generation of social scientists was concerned with the relation between health and bioidentities like race, gender, and age, we must now, according to Rabinow, examine the ways that diagnostic technology actually creates social difference and social groupings. Maybe this is beginning to happen even in developing countries. In Uganda, people who have been screened for HIV are encouraged to join post-test clubs. Although Rabinow emphasizes diagnostics, therapeutic technology can also form the basis for biosociality as in the case of support groups for people who have had mastectomies, colostomies, and transplants, or who are on lifelong antiretroviral therapy.

Here too ethnography is the test. Biosociality is not a given, but an empirical question. How does it work in particular circumstances? A beautiful example is Rayna Rapp's monograph on amniocentesis in the United States (1999). Her study differentiates “the subject,” which includes a whole range of people who live in New York, whom she identifies by age, ethnicity, and job.

Biosociality, “the forging of a collective identity under the emergent categories of biomedicine and allied sciences” (Rapp 1999:302) was one possibility for the parents of Down syndrome children. But it was mostly for a minority: mothers from two-parent families, middle-class, white, having resources of time and income. Although Rapp describes with sympathy the communities of difference, the friendship, the sharing of experience that these parents found in support groups, she also conveys critical voices, like that of Patsy DelVecchio, a recovering alcoholic who expresses resentment of class and of what she sees as self-promotion through identifying with difference.

I cannot see myself sitting with a bunch of petty little women, talking about their children like they were some kind of topic of conversation. This is just life … You get a lot of mothers that's behaving just like in AA, like, “Yeah, I'm an alcoholic,”“Yeah, I'm the mother of a Down's child.”… You get these Park Avenue high-society women with charge accounts saying, “I have my daughter at the institute, I have a private tutor for my daughter.”[Rapp 1999:299–300]

Concerning biosociality, Rapp concludes:

Biomedicine provides discourses with hegemonic claims over this social territory, encouraging enrollment in the categories of biosociality. Yet these claims do not go uncontested, nor are these new categories of identity used untransformed. … At stake in the analysis of the traffic between biomedical and familial discourses is an understanding of the inherently uneven seepage of science and its multiple uses and transformations into contemporary social life. [Rapp 1999:302–303]

It is the uneven seepage of science, the multiple uses and transformations that catch the ethnographer's eye, and not any straightforward working out of biopower expressed in bioidentities, subjectivities, and socialities.

The influence of Foucault is further refracted in the notion of biological (or biomedical or therapeutic) citizenship. Two sociologists, Nikolas Rose and Carlos Novas (2005), use “biological citizenship” to call attention to the way that conceptions of citizens are linked to beliefs about biological existence. Like Rabinow, they are interested in the implications of new biomedical technology for forms of biosociality, although they also note that biosocial groupings are far older than recent developments in genomics and biomedicine—and they make the link to earlier forms of activism and identity politics. Biological citizens are “made up” from above (by medical and legal authorities, insurance companies). And they also make themselves. The active biological citizen informs herself, and lives responsibly, adjusting diet and lifestyle so as to maximize health. “The enactment of such responsible behaviors has become routine and expected, built in to public health measures, producing new types of problematic persons—those who refuse to identify themselves with this responsible community of biological citizens” (Rose and Novas 2005:451).

This discussion of biological citizenship is programmatic and decontextualized. Most of the examples come from Internet sites; there are no lifeworlds here and no social differences of the kind Rapp reported. In this formulation, politics concerns an all-pervasive power that shapes perceptions and subjectivity. Citizens are categorized and behave (or not) in conformity with a biologically oriented discourse. In contrast, the ethnographic uses of the concept of citizenship are more focused on the variety of ways in which actors try to make claims and relate to agencies and institutions through health identities.

Adriana Petryna's original concept of biological citizenship was developed to analyze the struggles and strategies of Ukrainians exposed to radiation when the Chernobyl nuclear reactor exploded in 1986 (Petryna 2002). Skillfully she weaves the original Soviet denial of extensive damage together with the acceptance of state obligations to its citizens by the new government of independent Ukraine. She shows how damaged biology became the basis for making citizenship claims in the difficult conditions of a harsh market transition, increasing poverty, and loss of security. Biopower is part of her story, in that access to treatment, pensions, and other welfare benefits was based on medical, scientific, and legal criteria: “… science has become a key resource in the management of risk and in democratic polity building” (Petryna 2002:7).

Citizens have come to rely on available technologies, knowledge of symptoms, and legal procedures to gain political recognition and access to some form of welfare inclusion. Acutely aware of themselves as having lesser prospects for work and health in the new market economy, they inventoried those elements in their lives (measures, numbers, symptoms) that could be connected to a broader state, scientific, and bureaucratic history of error, mismanagement, and risk. The tighter the connections that could be drawn, the greater the probability of securing economic and social entitlements—at least in the short term. [Petryna 2002:15–16]

In a sense Petryna is describing what Rose and Novas call “making up biological citizens.” To “make the Chernobyl tie” and thus gain recognition by the state, people have to identify themselves in terms of certain symptoms. But Petryna is not talking about some general biopower; she specifies in terms of Ukrainian political history and the international humanitarian aid that made a disabled identity a survival strategy. She brings in the Ukrainian (and Soviet) cultural economy showing how those with good blat connections, or those who could exchange favors or money, were able to negotiate “better” diagnoses, higher disability status, and more entitlements. She gives examples of people who chose to neglect their symptoms, to keep working in the contaminated zone where salaries were much higher. Through her descriptions, we see situated actors who get drunk and beat their wives, try to avoid being drafted into the army, fail to play their sick roles convincingly, or succeed brilliantly as members of disability organizations.

Also anthropologists working with responses to AIDS have taken on the concept of biological citizenship to illuminate issues of rights, claims, and social exclusion. Like Petryna, they place health identities in the context of national history and global connections. Biehl (2004), writing about the activist state in Brazil, shows that “biomedical citizenship” includes those who identify themselves as having AIDS and actively struggle for treatment from public services. Those who do not assert their AIDS identity and rights to treatment—people marginalized by poverty, drug use, prostitution, homelessness—are excluded and made invisible. Community-run houses of support provide a chance for some of these “disappeared” people to be included in the “biocommunity” of AIDS patients: “in such houses of support, former noncitizens have an unprecedented opportunity to claim a new identity around their politicized biology” (Biehl 2004:122).

In a similar approach Nguyen analyses access to antiretroviral drugs in Burkina Faso in terms of a kind of biopolitics that he calls “therapeutic citizenship.” Unlike Brazil, most African states have so far been unable to include those identified as having AIDS within a supportive national community. Instead, local mobilization appeals to a global therapeutic order. Therapeutic citizenship is “a form of stateless citizenship whereby claims are made on a global order on the basis of one's biomedical condition” (Nguyen 2005:142). Activism on behalf of a wider community—a kind of identity politics—is one outcome of identification as HIV+ in Burkina Faso. But Nguyen's ethnographic analysis, like Petryna's, reveals a differentiated situation, in which some people form a vanguard of activists, whereas others are discrete about their identity as HIV+.

Toward Comparative Ethnography

At the risk of caricature, I have contrasted two different approaches to the study of health, identity, and politics. Identity politics focuses on social movements and organizations that reject neglect and discrimination and look to gain recognition and change social conditions. Scholars and activists in this tradition tend to assume conscious actors with intentions. Their questions move forward from the present: who is suffering? what is just? what can be done? The biopower approach problematizes the workings of discourse and technology in the shaping of subjectivity and new kinds of social relations. Its actors are not necessarily conscious of the processes affecting them. The questions here look back to explain the present: how is it that we have come to think like this? associate like this? act like this?

Conventionally, such a strategy of rhetorical dichotomizing ends with a synthesis. Nancy Fraser (1998), for example, argues that neither the politics of recognition, nor that of redistribution, can stand alone in the pursuit of social justice. Both are necessary. In the same classic style, I could point out that newer work on biocitizenship combines identity politics with biopower. The Foucauldian interest in the state and the self, the two poles of biopower, is enlarged with a focus on biosocial groups that make claims for inclusion and justice.

Yet I think it is more important to draw another point from this brief overview. There are pitfalls in both approaches. There is a danger that we lose sight of the political and economic bases of health in our concern with identity, recognition, and the formative effects of biomedical and social technology. By concentrating on the emergence of identities based on health categories, we may ignore other fundamental differences at the root of health inequities. Moreover, focusing narrowly on relations among people with the same health condition excludes all the other relations and domains of sociality that actually fill most of their daily lives. In fact, those other relations may strongly influence the ways that health comes to shape their identities and subjectivities. By defining research problems based on identifications like diabetic, Down syndrome, HIV+, we essentialize, fragment, and decontextualize what is really only part of a life. And it is, after all, a life and not an identity that people are usually seeking, as Michael Jackson reminds us (2002:119).

I have tried to show how detailed, comprehensive ethnography avoids these pitfalls and thereby problematizes identity politics and biopower in more interesting ways. By specifying history and political economy, the examples I have adduced allow us to examine the conditions under which identity politics and biopower might come into play. By describing patterns of social interaction, morality, and meaning, they suggest the processes through which assumptions and consciousness about health assume significance. Finally they are richly textured because the researchers have talked to many kinds of people and considered the multiplicity of domains in social life. The differentiated picture they paint shows not only the uneven seepage of science and medicine into social life, but also the uneven effects of different social conditions on the possibilities for the formation of health identities and subjectivities. With such ethnography in hand, we can begin to make comparisons over time and across social settings—still a major task for anthropology, medical and otherwise.

References

Anspach, Renee 1979 From Stigma to Identity Politics: Political Activism among the Physically Disabled and Former Mental Patients. Social Science and Medicine 13A:765–773.

Biehl, João 2004 Global Pharmaceuticals, AIDS, and Citizenship in Brazil. Social Text 22(3):105–132.

Bunkenborg, Mikkel 2003 Crafting Diabetic Selves: An Ethnographic Account of a Chronic Illness in Beijing. Masters thesis in Chinese Studies. Copenhagen : University of Copenhagen.

Fraser, Nancy 1998 Social Justice in the Age of Identity Politics: Redistribution, Recognition and Participation. Tanner Lectures on Human Values 19:1–67.

Goffman, Erving 1963 Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs , NJ : Prentice-Hall.

Ingstad, Benedicte, and Susan ReynoldsWhyte, eds. 2007 Disability in Local and Global Worlds. Berkeley : University of California Press.

Institute of Development Studies (IDS) 2003 The Rise of Rights: Rights-Based Approaches to International Development. IDS Policy Briefing 17. Sussex : IDS.

Jackson, Michael 2002 The Politics of Storytelling: Violence, Transgression and Intersubjectivity. Copenhagen : Museum Tusculanum Press.

Jenkins, Richard 1996 Social Identity. London : Routledge.

Nguyen, Vinh-kim 2005 Antiretroviral Globalism, Biopolitics, and Therapeutic Citizenship. InGlobal Assemblages: Technology, Politics, and Ethics as Anthropological Problems. A.Ong and S. J.Collier, eds. Pp. 124–144. Malden , MA : Blackwell.

Petryna, Adriana 2002 Life Exposed: Biological Citizens after Chernobyl. Princeton : Princeton University Press.

Priestley, Mark 1995 Commonality and Difference in the Movement: An “Association of Blind Asians” in Leeds. Disability and Society 10(2):157–169.

Rabinow, Paul 1996 Artificiality and Enlightenment: From Sociobiology to Biosociality. In Essays on the Anthropology of Reason. P.Rabinow, ed. Pp. 91–111. Princeton : Princeton University Press.

Rapp, Rayna 1999 Testing Women, Testing the Fetus: The Social Impact of Amniocentesis in America. New York : Routledge.

Rorty, Richard 1998 Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America. Cambridge , MA : Harvard University Press.

Rose, Nikolas, and Carlos Novas 2005 Biological Citizenship. In Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics, and Ethics as Anthropological Problems. A.Ong and S. J.Collier, eds. Pp. 439–463. Malden , MA : Blackwell.

Silla, Eric 1998 People Are Not the Same: Leprosy and Identity in Twentieth-Century Mali. Portsmouth , NH : Heinemann.

Turner, Terence 1993 Anthropology and Multiculturalism: What Is Anthropology that Multiculturalists Should Be Mindful of it? Cultural Anthropology 8(4):411–429.

Van den Bergh, Graziella 1995 Difference and Sameness: A Socio-Cultural Approach to Disability in Western Tanzania. MA thesis, Social Anthropology, University of Bergen.

Whyte, Susan Reynolds, and Herbert Muyinda 2007 Wheels and New Legs: Mobilization in Uganda. In Disability in Local and Global Worlds. B.Ingstad and S. R.Whyte, eds. Pp. 287–310. Berkeley : University of California Press.

#identity#identityformation#subjectivity#identity politics#ethnography#health#biomedicine#technology#biosociality

0 notes