#Buddhist and taoist figures...

Text

A Journey to the West x SL crossover would be fun

Liu Zhigang as Sun Wukong

Woo Jin-Chul as Tang sanzang

Christopher Reed as Pigsy Zhu Bajie

Thomas Andre as Sandy Sha Wujing

Kaisel is the White Dragon Horse

Cha Hae-In as GuanYin

Woo Jin-Chul who always has to get saved from every kind of demon attack by Liu Zhigang and the gang, all of this crisis just to deliver some scrolls to the West. Meanwhile lady Hae-In is just giving them farewell wishes from afar with her pet fish and her disciple Han Song-Yi.

Liu Zhigang was known very well as the Sage Equal to Heaven, often caused chaos since the time of his birth, it wasn't until he got kicked to the ground by Buddha and rested over a mountain for 500 years. Then Hae-In, trying to see who would be a good candidate to take care of this very important monk, decided to go to his mountain and convince him that he shall take care of Woo Jin-Chul from all kinds of evils in this trip.

The old Lao Tzu is Go Gun Hee.

The Jade Emperor is Yoo Jin-Ho who was entirely scared of a lot Liu Zhigangs acting and the way he just became immortal like 5 times. He eventually was the one to ask for help from the Buddha.

S-

S-sung

S-sung Jin Woo as six ear macaque 👀👀👀

Sung Jin Woo creating tension between Zhigang and Jin-Chul because he knows how much zhigang cares for Jin-Chul and he is jealous of that.

Sung Jin-Woo also appearing more times in the story just to keep creating problems for Zhigang more than Jin-Chul, he gets to be a bit fond of Jin-Chul and wants to take him away so that HE can be Jin-Chul's disciple and not Zhigang, that way Zhigang cannot become enlightened with Jin-Chul.

#guys i just realised#there might be fon jinchul Mpreg#god i love the journey to the west like ill read it and proabbly make more headcanons about it here#Jin woo fooling Jin chul about being Liu Zhigang and then Liu zhigang is just over there eating peaches and crying because Woo Jin chul -#said he doesnt want him as a disciple anymore and Hae In is like 'i guess imma have to talk to him about it ughhh'#I dont know whenever I should choose Laura or Hae In as Guan Yin#I also dont know whenever its rude to change the people as whoever you want? i mean they are characters from a book but they are also real#Buddhist and taoist figures...#I mean here Jesus could be portrayed as Beyonce and no one would bat an eye.#but idk if its the same there hmmmm#anyways might just get the story from the movies too so its more acceptable#hwbisbwk im doing mental gymnastics for some reason#solo leveling#solo leveling manwha#cha hae in#sung jin woo#he only appears once lmao#but in this fanfic he will probably appear more times absolutely just to cause chaos between Jin-Chul and Zhigang#Julyarya this can absolutely count as a shipping fanfic of Zhigang and JinChul#liu zhigang#thomas andre#christopher reed#kaisel sl#go gun hee#yoo jinho#woo jin chul

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

How many layers of ‘glamour’ does Macaque have?

We know that Macaque is using magic to hide his blind eye since we briefly saw it in S1EP9

However there is a chance that Macaque is changing his appearance even more than just covering up his blind eye

During S3EP8 ‘Benched’ we briefly see Macaque’s tail turn white before turning back to black & this has caused some debate on whether or not Macaque actually has white fur since there are white furred Macaque’s & previous interpretations of Macaque such as Monkey King 2009 have depicted him with more of a white furred shade

So there is the possibility that Macaque could have white fur but is using another layer of glamour to cover it up though since we saw his blind eye in season one a lot of people have argued that Macaque doesn’t have another layer of glamour usually & that the white fur we saw was from LBD’s influence on Macaque in season 3.

Whether Macaque is naturally white furred or not though in season 3 it’s possible he had two layers of glamour one to cover his blind eye and one to cover his white fur but there’s also a possibility of a third layer of glamour.

For his six ears

Despite introducing himself as the Six Eared Macaque & LBD also referring to him under the same title we’ve never actually seen Macaque’s six ears though the shows team say that Macaque’s reaction to Pigsy’s singing is a reference to his six ears & keen hearing.

There’s been some debate on whether Macaque actually has six ears since we didn’t see them when we saw his blind eye & the argument that people have made is that the six ears are metaphorical since there’s a chance that Macaque’s ‘six ears’ are actually a pun based off an old Buddhist sayings of “The dharma is not to be transmitted to the sixth ear [i.e. the third pair/ person]”. A 'sixth ear' refers to an extra person in a private conversation, someone possibly eavesdropping or listening in & Macaque is said to have exceptional hearing.

Macaque being called the Six Eared Macaque because he has the ability to constantly be 'the sixth ear' or third party listening in on peoples conversations.

Those that believe that Macaque had come from Monkey King representing his ‘evil side’ think that Macaque’s six ears are actually a reference to the six desires a concept found in some Buddhist and Taoist writings & those desires are things that Sun Wukong had to cast aside in order to achieve true enlightenment.

However in the show there is a chance that Macaque does literally have six ears that he’s hiding since he has at least one lego figure which were given six ears & the season 3 concept art showed him with six ears as well

So there is a chance that Macaque has six ears in the show but is just covering them up though that has led to some debate on why he revealed his blind eye in S1EP9 but not his ears even though he introduced himself as the Six Eared Macaque. The debate may continue until we actually see Macaque’s six ears in the show itself.

So as it stands it’s possible that Macaque is using three layers of glamour:

One to hide his blind eye

Another to hide his white fur (debatable since the white fur could have been caused by LBD

A final one to hide his six ears

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Horned hermits and immoral immortals: an inquiry into Zanmu's background

As you might remember from my previous post covering Zanmu, I was initially unable to tell how her historical background led to ZUN choosing to make her an oni. The historical, or at least legendary, Zanmu seemed to be, for all intent and purposes, a human. That has since changed, and the matter now seems considerably more clear to me. Read on to learn more about the real monk Zanmu is based on, and to find out what she has in common with the most famous Zen master in history, Taoist immortals, and Tsuno Daishi.

Even if you are not particularly interested in Zanmu, this article might still worth be checking out, seeing as the discussed primary sources are also relevant to a number of other Touhou characters, including Byakuren, Yoshika and Kasen.

As in the case of the previous Touhou article, special thanks go to @just9art, who helped me with tracking down sources advised me while I was working on this.

The historical Zanmu

Statue of Zanmu from the Sazaedo pagoda (Fukushima Travel; reproduced for educational purposes only)

As already pointed out by 9 here even before my previous post about Unfinished Dream of All Living Ghost, Zanmu is based on a real monk also named Zanmu. His full name was Nichihaku Zanmu (日白残夢), and he also went by Akikaze Dōjin, but even Japanese wikipedia simply refers to him as Zanmu. ZUN basically just swapped one kanji in the name, with 日白残夢 becoming 日白残無. The character 無, which replaces original 夢 (“dream”), means “nothingness” - more on that later.The search for sources pertaining to the historical Zanmu has tragically not been very successful. In contrast with some of the stars of the previous installments, like Prince Shotoku or Matarajin, he clearly isn’t the central topic of any monographs or even just journal articles. Ultimately the main sources to fall back on are chiefly offhand mentions, blog articles and some tweets of variable trustworthiness.

The only academic publication in English I was able to locate which mentions Zanmu at all is the Japanese Biographical Index from 2004, published by De Gruyter. The price of this book is frankly outrageous for what it is, so here’s the sole mention of him screencapped for your convenience:

The book referenced here is the five volume biographical dictionary Dai Nihon Jinmei Jisho from 1937. I am unable to access it, but I was nonetheless able to cobble together some information about Zanmu from other sources.

Not much can be said about Zanmu’s personal life. He was a Buddhist monk (though note a legend apparently refers to him as “neither a monk nor a layperson”, a formula typically designating legendary ascetics and the like) and a notable eccentric. Both of these elements are present in the bio of his Touhou counterpart.

The Sazaedo pagoda (Fukushima Travel; reproduced for educational purposes only)

Zanmu’s tangible accomplishments seem to be tied to the temple Shoso-ji, which he apparently founded. He is enshrined in the Sazaedo pagoda near it, though this building postdates him by over 200 years. It’s located in Aizuwakamatsu in Fukushima. You can see some additional photos of his statue displayed there in this tweet. It’s a pretty famous location due to its unique double helix structure, and it has a pretty extensive article on the Japanese wikipedia. It’s also covered on multiple tourist-oriented sites in English, where more photos are available (for example here or here). There’s even a model kit representing it out there. Sazeado’s fame does not really seem to have anything to do with Zanmu, though.

While many Buddhist figures ZUN used as the basis for Touhou characters in the past belonged to the “esoteric” schools (Tendai and Shingon), Zanmu was a practitioner of the much better known Zen, specifically of the Rinzai school.

The kanji mu (無 ) caligraphed by Shikō Munakata (Saint Louis Art Museum; reproduced for educational purposes only)

Since the concept of “nothingness” or “emptiness” represented by the kanji 無 (mu) plays a vital role in Zen (see here or here for a more detailed treatment of this topic; it’s covered on virtually every Zen-related website possible though), and there’s even a so-called mu kōan, it strikes me as possible this is the reason behind the slightly different writing of the names of ZUN’s Zanmu, as well as the source of her ability. Granted, the dialogue in the games makes it sound like Zanmu (and by extension Hisami) just talks about nothingness as a memento mori of sorts, which is not quite what it entails in Zen. Of course, ZUN does not adapt Buddhist doctrine 1:1 (lest we forget Kasen seemingly being unaware of the basics of Mahayana in WaHH) so this point might be irrelevant.

The legendary Zanmu

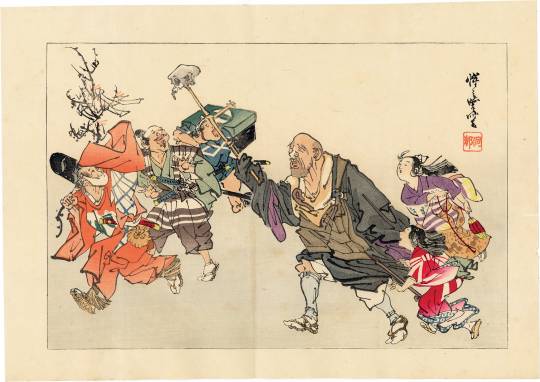

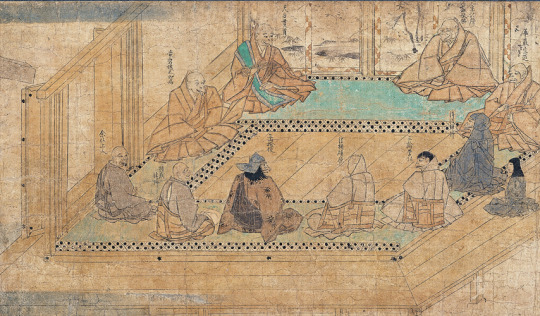

The eccentric monk Ikkyū (center), as imagined by Kawanabe Kyōsai (Egenolf Gallery; reproduced for educational purposes only)

A number of legends developed around the historical Zanmu. If this blog post is to be trusted, there is a tradition according to which he was a student of arguably the most famous member of the Rinzai school, and probably one of the most famous Buddhist monks in the history of Japan in general, Ikkyū. He is remembered as the archetypal eccentric monk, and spent much of his life traveling as a vagabond due to his disagreements with Buddhist establishment and unusual personal views on matters such as celibacy. As I already said in my previous article pertaining to Zanmu, long time readers of my blog might know Ikkyū from the tale of Jigoku Dayū and art inspired by it, though since this motif only arose in the Edo period it naturally does not represent an actual episode from his very much real career.

A page from Ikkyū Gaikotsu (wikimedia commons)

In art a distinct tradition of depicting Ikkyū with skeletons developed, as seen both in the case of works showing him with his legendary student Jigoku Dayū and in the so-called Ikkyū Gaikotsu. Skeletons also played a role in Zen-inspired art in general (for more information see here). Whether this inspired ZUN to decorate Zanmu’s rock with bones is hard to determine, but it does not seem implausible. It would hardly be the deepest art history cut in the series, less arcane of a reference than the very existence of Mai and Satono or Kutaka’s pose.

Obviously, it does not seem very plausible that Ikkyū ever actually met the historical Zanmu. Ikkyū passed away in 1481, and Zanmu in 1576, with his birth date currently unknown. Even if we assume he was a particularly long-lived individual and by some miracle was born while Ikkyu was still alive, it is somewhat doubtful that an elderly sick monk would be preaching Zen doctrine to an infant. However, apparently legends do provide a convenient explanation for this tradition. Purportedly Zanmu lived for an unusually long time. The figure of 139 years pops up online quite frequently, and does seem to depend on a genuine tradition, but even more fabulous claims are out there.

Kaison Hitachibō, as imagined by an unknown artist (wikimedia commons)

According to another legend, Zanmu was even older, and in fact remembered the Genpei war, which took place in the Heian period - nearly 400 years before his time. Supposedly he told many vivid tales about its famous participants, Yoshitsune and Benkei. A tradition according to which he was himself originally a legendary retainer of Yoshitsune, the warrior monk Kaison Hitachibō (常陸坊海尊) developed at some point. This has already been pointed out by others before me in relation to the Touhou version of Zanmu. From what I’ve seen, some Japanese fans in fact seem excited primarily about the prospect of Zanmu offering an opportunity to connect Touhou and works focused on the Genpei war.

The tradition making Zanmu a centuries-old survivor from the Heian period must be relatively old, as his supposed immortality is already mentioned in Honchō Jinja Kō (本朝神社考; “Study of shrines”) by Razan Hayashi, who was active in the first half of the seventeenth century, mere decades after Zanmu’s death. While I found no explicit confirmation, it seems sensible to assume this legend was already in circulation while Zanmu was still alive, or at least that it developed very shortly after he passed away. Perhaps he really was invested in accounts of that period to the point he sounded as if he actually lived through it.

The choice of Kaison as Zanmu’s original name in the legend does not seem random, as there was a preexisting tradition according to which this legendary Heian figure was cursed with eternal life for betraying Yoshitsune by fleeing from the battlefield instead of remaining with his lord to die. You can read more about this here. Apparently there is a version where he instead becomes immortal to make it possible to pass down the story of the Genpei war to future generations (this is the only source I have to offer though), and there's even a well-received stage play based on it, Hitachibō Kaison (translated as "Kaison, priest of Hitachi") by Matsuyo Akimoto.

Another thing worth pointing out is that Kaison was seemingly a Tendai monk from Mount Hiei, which means that even though Okina isn’t in a new game, you can still claim she’s metaphorically casting her shadow over it in some way if you squint (and that’s without going into the fact sarugami are associated with Mount Hiei). I've seen two separate sources which mention that according to a legend he trained Benkei there, and that the two did not get along because Kaison was a corrupt monk (lustful, keen on substance abuse, greedy, the usual routine). You can access them here and here,but bear in mind they're old.

Zanmu’s Genpei war connection does not really seem to matter in Touhou, though, as ZUN pretty explicitly situated his version in the Sengoku period, with no mention of earlier events. Granted, if you like it, this should not prevent you from embracing the view that Zanmu is an alter ego of Kaison as your headcanon - as I said people are already doing that. It seems equally fair game as “Okina is Hata no Kawakatsu”, easily one of the most popular “historical” headcanons in the history of the franchise.

According to this twitter thread, the legends about Zanmu’s longevity (or immortality) have a pretty long lifespan themseles, as they were referenced by relatively high profile modern writers, like Orikuchi Shinbou and Tatsuhiko Shibusawa.

Buddhist immortals

A word carving of a sennin, "immortal" or "hermit" (wikimedia commons)

Legends about long-lived (or outright immortal) monks, such as Zanmu or Kaison, are hardly uncommon. A work which seems to be the key to understanding their early development, and by extension possibly also the portrayal of Zanmu in Touhou, might be Honchō Shinsenden, “Records of Japanese Immortals”. This title refers to a collection of setsuwa, short stories typically meant to convey religious knowledge or morals. Its title pretty much tells you what to expect.

Honchō Shinsenden is an interesting work in that while it in theory deals with Buddhism, and largely describes the individual immortals as, well, Buddhists, it ultimately reflects a Taoist tradition. There is a strong case to be made that it was an inspiration for another Touhou installment, specifically Ten Desires, already, seeing as it mentions prince Shotoku and Miyako no Yoshika and its Taoist-adjacent context has a long paper trail in scholarship, but I will not go too deep into that topic here - expect it to be covered in a separate article later on.

Stories of immortals are pretty schematic, and their protagonists can be categorized as belonging to a number of archetypes. I think it’s safe to say this has a lot to do with the self-referential character of this sort of literature - compilers of new works were obviously familiar with their forerunners, and imitated them for the sake of authenticity. In China, literary accounts of the lives of immortals circulated as early as in the first century BCE, with the concept of immortals (xian, 仙, read as sen in Japanese; this term and its derivatives have various other translations too, with Touhou media generally favoring “hermit”) itself already appearing slightly earlier.

It seems Shenxian Zhuan (Biographies of Spirit Immortals) by a certain Ge Xuan, certified immortals enthusiast and cinnabar-based immortality elixir connoisseur (discussing and developing immortality elixirs was a popular pastime for literati in ancient and medieval China), can in particular be considered the inspiration for the later Japanese compilation.

While the concept of immortals was largely developed by Taoists, tales focused on them were already not strictly the domain of Taoism by the time they reached Japan. They were embraced in Chinese culture in general, both in strictly religious context and more broadly in art. In Japan, they came to be incorporated into Buddhist worldview, and in fact Honchō Shinsenden states that their protagonists can be understood as “living Buddhas” (ikibotoke), a designation used to refer to particularly saintly Buddhists. Their devotion to both Buddhas and other related figures, and to local kami, is stressed multiple times too.

Presumably this was the result of the influence of the Japanese Buddhist concept of hijiri (聖), a type of particularly rigorous solitary ascetic in popular imagination regarded as almost divine. Needless to say, most of you are actually familiar with the hijiri even if you never read about them, as this is the source of Byakuren’s surname and a clear influence on her character too. In Honchō Shinsenden, it is outright said that the sign 仙, normally read as sen, should be read as hijiri in this case.

A portrait of Huisi (wikimedia commons)

The notion of extending one’s lifespan was not incompatible with Buddhism, as evidenced by tales of adepts who lived for a supernaturally long period of time to show their compassion to more beings or to get closer to the coming of Maitreya. Even the founder of the Tiantai school of Buddhism (the forerunner of Japanese Tendai), Huisi, was said to meditate in hopes of extending his life to witness Maitreya. At the same time, Chinese compilations of stories about immortals do not list Buddhists among them, in contrast with Japanese ones. This might be due to the rivalry between these religions which was at times rather pronounced in Tang China, culminating in events such as emperor Wuzong's persecution of Buddhism.

Let’s return to Honchō Shinsenden, though. Its original author was most likely Ōe no Masafusa, active in the second half of the eleventh century. No full copy survives, but the original contents can nonetheless be restored based on various fragmentary manuscripts. Some of the sections are preserved as quotations in other texts or in larger compilations of stories, too. I have seen claims online that the historical Zanmu is covered in some editions of the Honchō Shinsenden or works dependent on it. So far I was only able to determine with certainty that Zanmu is covered alongside the immortals from Honchō Shinsenden in at least one modern monograph (Nishi-Nihon-hen by Kōsai Chigiri; if anyone of you have access to it I’d be interested to learn what exactly it says about Zanmu) and a number of posts and articles online. However, he lived around 400 years after this work was completed, so he quite obviously does not appear in its original version, contrary to what the Touhou wiki says right now.

Masafusa does not necessarily portray the immortals as pinnacles of morality, and indeed moral virtues do not seem to be a prerequisite for attaining this status in his work. It is therefore possible that despite being setsuwa, his tales of immortals were an entirely literary endeavor and were not meant to evoke piety, let alone promote the worship of described figures.

A recurring pattern which unifies all of these tales is describing immortals as eccentric. As I already noted, this is a distinct characteristic of the historical Zanmu too, and it comes up in the bio of his Touhou counterpart as well. She has “reached the absolute pinnacle of eccentricity”. It seems safe to say ZUN is aware of that pattern, then, and consciously chose to highlight this. He also stresses that Zanmu has lived through an era of marital strife, specifically through the Sengoku period. The inclusion of such episodes is another innovation typical for Japanese immortal tales, and does appear to be a feature of the tradition pertaining to Zanmu’s counterpart too, as discussed above.

Horned hermits?

A modern devotional statuette of Laozi with horns, found on ebay of all places; reproduced here for educational purposes only.

There is a further possible feature of Zanmu that might be tied to Honchō Shinsenden. While there are numerous physical traits attributed to immortals in Chinese sources, Masafusa decided to only ever highlight two. One of them are unusual bones, the other - horns on the forehead. Tragically one of my favorites, square pupils (mentioned in Liexian Zhuan), is missing. Masafusa relays that an anonymous hijiri, the “Rod-Striking Immortal”, grew stumpy horns as a sign of attaining his supernatural status.This might be a stretch, but perhaps Zanmu, due to being the Touhou version of a legendary immortal, also already had horns before becoming an oni. You have to admit it would be funny.

The two horns - or rather small bumps, based on available descriptions - characteristic for some immortals were known as rijiao (日角; “sun-horn”) and yuenxuan (月懸; “moon crescent”). Such unusual physical features were already attributed to various legendary and historical rulers and sages in China in the first century CE, so this is not really a Taoist invention, but rather an adoption of beliefs widespread in China in the formative years of this religion. They also intersected with the early Buddhist tradition about the so-called “32 marks of the Buddha”, documented for example in Mahāvastu and later in Chinese Mahayana tradition which Taoist authors were familiar with. Yu the Great, the flood hero, was among the legendary figures said to possess horns in Chinese tradition. It is even sometimes believed Laozi had them when he was born, which according to Livia Kohn was meant to symbolically elevate him to the rank of such mythical figures as Fuxi.

While this is ultimately a post focused on Zanmu, I think it’s worth pointing out this belief in horned ascetics has very funny implications for Kasen. Being a “horned hermit” is not really an issue, it would appear. If anything, it adds a sense of authenticity. Clearly Kasen needs to study the classics more.

Immortals (and mortals) in hell

One last connection between Zanmu and legends about immortals is her role as an official in hell. However, this is much less directl. Early Chinese sources mention “Agents Beneath the Earth” (dixia zhu zhe 地下主者), a rank available to low class immortals choosing to serve in the land of the dead. They could be contrasted with the immortals inhabiting heaven, regarded as higher ranked than them. However, note that there are also many narratives focused on mortals becoming officials in hell - in Japan arguably the most famous case is the tale of Ono no Takamura, a historical poet from the early Heian period. In Chinese culture there are multiple examples but I think none come close to the popularity of judge Bao. It does not seem any immortals playing a similar role retain equal prominence in culture.

Ultimately this paragraph is only a curiosity, and a much closer parallel to Zanmu's role in hell exists - and it’s connected to materials ZUN already referenced to booth.

Corrupt monks, oni and tengu

Ryōgen, the most famous monk turned demon, and his alter ego Tsuno Daishi (wikimedia commons)

In addition to characterizing Zanmu as eccentric, ZUN also wrote in her bio that she is a corrupt monk. As we learn, she developed a belief that the best way to reconcile the Sengoku period ethos which demanded boasting about the number of enemies killed with Buddhist precepts was to focus on spirits rather than the living, since she will basically deliver salvation to them. She ultimately “absorbed some beast-youkai spirits, thus discarding her life as a human”. This to my best knowledge does not really match any genuine tradition about the historical Zanmu, related figures or anyone else. As far as I can tell, it’s hard to find a direct parallel either in irl material or elsewhere in Touhou... at least if we stick to the details. More vaguely similar examples are not only attested, discussing them was for a time arguably the backbone of Buddhist discourse in Japan, and neatly explains why Zanmu became an oni.

The idea that monks who broke Buddhist precepts in some way turned into monsters is not ZUN’s invention. It first appears in sources from the Heian period, and gained greater relevance in the Kamakura period. Particularly commonly it was asserted that members of Buddhist clergy who fail to attain nirvana turn into tengu. However, oni were an option too. Bernard Faure points out that Ryōgen, the archetypal example of a fallen monk (see here for a detailed discussion of this topic, and of his return to grace as a demon keeping other demons at bay), could be described as reborn as an oni, for example. The Shingon monk Shinzei is variously described as turning into an oni, a tengu or an onryō (vengeful spirit). Oni are also referenced in a similar context in Heike Monogatari alongside tenma, a term referring to demons obstructing enlightenment in general.

Corrupt monks turned into tengu in the Tengu Zoshi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

Typically it was believed that monks who turned into demons went to a realm variously known as makai, tengudō or madō. As you may know, normally there are three realms one should avoid reincarnating in - beasts, hungry ghosts and hell - but this was basically a bonus fourth one. Granted, this view was not recognized universally, and the alternative interpretation was that it was just a specific hell with a distinct name.

At the absolute peak of this concept’s relevance, the foremost Buddhist thinkers of these times, including Nichiren, were accusing each other of being demons. Additionally, some of the past emperors, especially Sutoku and Goshirakawa, could be presented as tengu, for example in Hōgen monogatari. There was also an interest in finding gods who could keep the forces of disorder at bay. You can see echoes of these beliefs in rituals pertaining to Matarajin, which ZUN rather explicitly referenced in Aya's route in Hidden Star in Four Seasons.

Typically the reason behind transformation into an oni, tengu or another vaguely similar being were earthly attachments. Alternatively, it could be pursuing gejutsu, “outside arts”, essentially teachings which fell outside of what was permitted by Buddhism. Note this does not necessarily mean anything originating in religions other than Buddhism, though, the term is more nuanced. So, for instance worship of kami or following Confucian values are perfectly fair game. A synonymous term was gedō, “heretical” way (on the use of the term “heresy” in the context of study of Buddhism see here). We can make a case for Zanmu’s bio alluding to that - she wanted to adhere to the social norms of the Sengoku period by symbolically taking in a headcount by absorbing spirits, I suppose. That’s not really a thing in any Buddhist literature, though, and I assume ZUN came up with this himself.

Conclusion

While this article is slightly less rigorous than my recent research ventures pertaining to Matarajin, let alone the Mesopotamian wiki operations, I hope it nonetheless sheds some additional light on Zanmu. I will admit I already liked her even before I started digging into the possible inspiration behind her, and finding out more only strengthened my enthusiasm.

While there are clear parallels between Zanmu, her namesake and a variety of other characters from Japanese and Chinese literature and religions, as usual for a character made by ZUN her strength lies both in creative repurposing of these elements and in adding something new.

Postscriptum: Zanmu and Tang Sanzang?

Xuanzang, as depicted by an unknown Qing artist (wikimedia commons)

While much about Zanmu’s character - her backstory as an eccentric fallen monk who became a demon, her apparent zen theme, and so on - all form a coherent whole, there is a tiny detail which does not really match anything else discussed in this article.

It does not come from her dialogue or bio, but rather from Enoko’s. As we learn, she became immortal herself after eating a piece of Zanmu’s body back when the latter was still a human. Or rather, the combination of that and subsequently consuming a magical gemstone as recommended by Zanmu did it - I’m pretty sure I misread this before. As 9 pointed out to me, probably the implications are just that Enoko’s backstory is a partial reference to Perfect Memento in Strict Sense, which does state that consuming the flesh of a monk would be a particularly suitable way for an ordinary animal to turn into a youkai.

Still, comparisons between this tidbit and Journey to the West have been made by others before already, so I figured it would be suitable to address them here even if they lie beyond my own argument about the inspiration behind Zanmu. In this novel, many demons want to devour its protagonist Tang Sanzang because his flesh is said to make anyone who consumes immortal. This is because he is a reincarnation of Master Golden Cicada (Jinchan zi, 金蟬子), a disciple of the Buddha invented for the sake of the story. Interestingly, Sanzang is portrayed as an adherent of Chan Buddhism, the school from which Japanese Zen is derived (note that his historical forerunner Xuanzang belonged to the Yogācāra tradition instead).

Despite the vague similarities, I ultimately do not think there are particularly close parallels between Zanmu and Sanzang. For starters, Zanmu is meant to be a corrupt monk, while Sanzang is the opposite of that. Their respective characters couldn’t differ more either. Throughout the entire novel, Sanzang is a pretty poor planner, shows doubt in his own abilities, and regularly misjudges the situation. Needless to say this does not exactly offer a good parallel to Zanmu. Sure, she creates a bootleg Wukong, but Sanzang did not create Wukong, the famous primate was just assigned to him as a bodyguard. Therefore, until evidence on the contrary appears (for example in an interview) I would personally remain cautiously pessimistic regarding a possible connection here.

Recommended reading

Bernard Faure, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Noga Ganany, Baogong as King Yama in the Literature and Religious Worship of Late-Imperial China

Zornica Kirkova, Roaming into the Beyond: Representations of Xian Immortality in Early Medieval Chinese Verse

Christoph Kleine & Livia Kohn, Daoist Immortality and Buddhist Holiness: A Study and Translation of the Honchō shinsen-den

Livia Kohn, The Looks of Laozi

James Robson, The Institution of Daoism in the Central Region (Xiangzhong) of Hunan

Haruko Wakabayashi, From Conqueror of Evil to Devil King: Ryogen and Notions of Ma in Medieval Japanese Buddhism

Idem, The Seven Tengu Scrolls. Evil and the Rhetoric of Legitimacy in Medieval Japanese Buddhism

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

emperor!geto x imperial concubine!reader

a/n: I’ve spent way too much time to research about chinese imperial concubines, playing with Royal Chaos during my highschool years and I had a boring shift at work. This is the result. Probably out of character as hell but hey, I wrote this for my enjoyment.

This is part 1 of a lil historical AU drabble series. I’m already finished with Sukuna, Gojo is in the works, and I got some ideas for Choso and Toji but don't think too much about it, ideas are just ideas.

I was so close to write reader as gender neutral but reader owns a type of traditional chinese headgear used exclusively by noblewomen so... yeah, reader is afab if you squint (very hard).

Likes and reblogs are appreciated, mwah <3

wc: 1011, I initally wanted a few headcannons but I got a full ass drabble

cw: suggestive, false accusations, implied murder, mentions of whipping, choking (not the kinky kind), yandere behavior

credits: renmakia for the gorgeous fanart and my dear @notveryrussian for proofreading and just putting up with my massive jjk brainrot every day, luv ya darling <33

MDNI, if you do, I'm gonna catch you like I'm gonna catch Gege.

He’s a monarch who considers his mind a weapon and information as a whetstone despite being born in relative peace. Spending his leisure time reading Sun Ce, the scripts of Confucian and Taoist scholars, sharing afternoon teas and long walks around the gardens with Buddhist priests and conversing about reaching enlightenment. As if he desperately wanted to understand how the world he was meant to rule works. His mandate of heaven brought prosperity, a flourishing economy, a strong connection between allied realms, a good education system that produced more scholars than in any other time before.

Competing for his attention is not an easy task. You almost gave up, bracing yourself for a long and uneventful life where you can only admire him from afar. You sit in the shade of a willow tree with a board of xiangqi, your playmate having left you not so long ago and you were trying to figure out which tactics and strategies they should’ve used to defeat you. You’re so lost in your thoughts you can’t notice him standing there, in the presence of his guards. You kowtow to him, excusing yourself for daring to bother him, pleading for his patience while you pack your things and leave. He likes that your manners are spot on, and he rewards you with a command to stay, to play with him, since xiangqi is a game between two people. And based on the positions of the pieces on the board you’re an experienced player.

Of course, he defeats you with ease, but he’s grateful you showed him everything you’ve got and didn’t let him win. He tells you that his victory lies in applying the teachings of Sun Ce to his playstyle. Your eyes light up and you beg him to elaborate further, maybe he can help you improve your tactics in the next game. He’s such a well-read man, so hungry for knowledge, so desperate to understand people. You’re sure he wants to figure out your thoughts too, what you think about the world, what values dominate your heart. And the secret to win him over is to shower him with all the details and even politely disagree with some of his beliefs and explain your point of view. That’s what gets him going, knowing your place in the hierarchy but not being afraid to stand your ground. Mindless obedience, at this point, bores him. That’s probably the reason why he slowly starts to favor you, your conversations refresh him, inside and outside of his bedchambers.

You may think that earning your place in his heart is a lengthy and hard process, but when he becomes sure that your infatuation comes from an honest place, he generously rewards your efforts. He showers you with gifts, each more thoughtful than the other. He sends you scripts from his personal library about topics that interest you, fulus he received from his priests to protect you and your chambers, phoenix crowns so elaborately adorned with pearls, sapphires, small dragons, and phoenixes made from solid gold. Gowns embroidered with clouds, cranes dancing around them, gifting you a small piece of the sky itself he descended from. He elevates your rank quickly so you can accompany him during events. Letting the whole court look at you, wrapped in everything he gave you, standing so close you can see him stealing glances at you from under the twelve tasseled crown. He rewards your family with money, grain, rice, political power. If he lifts you up, he does the same with everyone important to you.

But Geto’s court is highly competitive. It’s certainly not easy to be his favorite. You can literally smell the stench of jealousy eminating from the other consorts. Their gaze pierces your skin deeply when the eunuchs drag you around the Palace of Heavenly Grace with a brocade blanket hugging your naked figure. They must endure the sight every other night and they have no idea that the son of heaven is ready to serve you and do as you please behind closed doors and not the other way around, as tradition dictates.

Though he can comfort you, outside of his chambers you fear for your life. You needed a food taster now and never dared to walk the gardens without at least four guards in your proximity. You begin to doubt the trust between you and those you’ve befriended, because they can only blame you for his negligence towards them.

And then, the first accusation about you begins circulating around the palace. Some concubines claimed that you were guilty of witchcraft. So many of them are against you, with so much made-up proof you cannot do more than spend the night crying, believing that at dawn, guards will come for you and throw you into a well. You have no idea where Geto is or how you could beg him for protection.

The next day, strangely, a new set of officials deem you innocent. What boggles you even more is that he comes to your residence instead of having you delivered to him. Even his scent is not like it usually is, there’s something metallic, salty, and musky mixed in with the incense smoke.

That night he cradles you, shushing you, promising to keep you safe at all costs. Keeping it a secret how brutally he disposed of the rumor mongers, how he had some of his officials whipped bloody for not believing your testimony or about the thinly veiled threats that he’ll make anyone’s life a living nightmare if anything happened to you. Your heart skips a beat and simultaneously sinks deep in your chest when those of higher rank than you lower their head, trying their best to not look at you as they pass you by. With dark marks staining the skin below the neckline of their gowns, not even the empress consort being an exception.

It's not easy to be his favorite. It’ll never be easy.

But he’s a god, the son of heaven, and heaven will forgive him and so will you.

#jujutsu kaisen#jjk#jjk x reader#jujutsu kaisen x reader#geto suguru x reader#jjk drabbles#getou suguru x reader#jjk x y/n#meesa writes

255 notes

·

View notes

Note

I know you most likely already realized this, but I was just thinking about Aang as a father in LOK, and realized something. If Katara ended up with Zuko and eventually had children together, Zuko would likely end up being a better father than Aang. Aang never even met his parents, and only had instructors as parental figures. They're like parents but mostly just in the way that a school teacher would be. But Zuko understands what good parents and what bad parents look like because he knows what his own parents are like. His memories of Ursa and Iroh would be his guide to what you SHOULD do for a child, and Ozai is an example of what you should NOT do. Zuko doesn't have the pressure of repopulating firebenders because firebenders aren't virtually extinct, so there wouldn't be as much (if any) pressure to pay unfairly extra attention to one child over the other. Zuko knows what it's like to be neglected by a parent that's supposed to love because of something you can't control. Aang clearly doesn't, hence why he neglected Bumi and Kya II in the first place. Zuko also has experience with Azula, and would know to recognize any bad signs of sibling jealousy and/or hatred, and put an end to it because he knows what bad sibling dynamics look like.

I feel like he would also be a better husband to Katara. He's not as naive as Aang when it comes to marriage; Zuko has the experience of growing up with two married parents, and would know what not to do. Katara would relax better because the distribution over who watches the kids would be more fair, as Zuko would give them ALL attention. While Aang made Katara jealous from always being around the Air Acolytes (in the comics), I feel like Zuko would not give polite attention to women who are rude to Katara/flirting with him because in the show, Zuko knows exactly how hurtful it feels for a romantic partner to flirt with/give polite attention to people who are obviously pursuers. Imagine being in an alternate dimension where Zutara was the main endgame couple, and we get to see their parental dynamics in LoK. There would probably be a flashback of Katara getting worked up about one of their children, and Zuko would ease her into calming down because he sees a solution that she didn't.

Aang's issues are more than he doesn't know. He is selfish by nature. Selfish parents aren't good parents. I know this for a fact. It's an endless cycle of 'It's your fault' or 'what about how I feel' every time you try to say something. It's not fun, and it's damaging. I can totally see Aang using this behavior as a way to get what he wants. As far as him being naive... yes. He is very naive and doesn't take anything seriously.

Like the war, for instance. He was only there for the last year of it. He wasn't born into the war like Zuko, Katara, Sokka, Toph, and Suki. They aren't naive. They know what war is like. Toph is the same age as Aang, and she is much more mature than he is. He's got this idea that killing anyone is bad, but he is responsible for a lot of deaths. Honestly, he has a kill count from the Fire Nation attack on the NWT, and a lot of people overlook that for some reason. Actually, the show overlooks it because Aang is the Hero, and it's okay if he killed people. So, when all is said and done, all of the things that he does afterward is overlooked too. It's a huge writing flaw with the show. So how does this translate to him as a parent?

It makes him a hypocrite.

Plain and simple.

He's so focused on reviving the Air Nomads that he has little knowledge on what they actually believed. What we are given is a few Taoist, Hindu, and Buddhist proverbs to go off of. Then, it's completely disregarded (disrespected as well) for 'Love'. This 'Love' is actually deep infatuation fueled by jealousy and possessive behavior. Which is actually frowned upon by the three religions mentioned above. It is a 'poison' to the spirit. And disconnects you from being enlightened (I think that is what the proverbs/scriptures are eluding too, if I'm wrong, please do not hesitate to explain, I'm super interested in cultures and eastern religions) or granted a place in Heaven (or their version of it). Letting go of all earthly possessions is common place in most religions. Aang does not do this. But I digress.

So, while there is the Nature vs Nurture aspect of parenting... where Katara does most of the Nurturing because that is how her character is written post-war and LoK. Notice how is said Written. Written by two misogynistic men who stripped her of a lot of her characteristics from the original run of the show. This is the problem. And it's the same with Aang. I can't take him seriously because he doesn't take any of it seriously. Especially with his children. He's not a serious character. He acts like he's serious, but he never really left the 12 year old boy behind to mature. Probably because in his fictional relationship with Katara, she enables him to keep doing what he always does. Which is to not grow. Relationships grow sour when the two people in them do not grow. It's not really about who grew up with parents at that point because it's the current parents that are the ones that should be to blame.

Now on to Headcanon space...

Zutara is a Headcanon ship. Did it almost happen? Oh yes I believe it did because the writing supports it heavily and Bryke's actions post show also scream 'lairs'. Sorry, but I have a pretty good Bullshit metor and Bryke set it off big time by their immature behavior.

But I digress.

Zuko grew up with a Narcissistic Sociopath as a Father and a Mother who was caught in the middle of a choice she was essentially forced to make. Ursa was also forced to forget her own parents never existed after she married Ozai. This is all canon, by the way. Her life before her marriage was great, but then it was taken away so she had nothing left but her morals and beliefs. However, while she loved both of her children, her influence on Zuko is essentially what made him who he is. Ursa didn't get to influence Azula like she did Zuko. Why? Because of Ozai.

Ozai pit his children against each other. This was apparently a Fire Nation Royal Family tradition because it sounds like Azulon did this with Iroh and Ozai as well. This kind of parenting style is abusive to its core. What Ozai did to Zuko isn't neglect... it's straightforward abuse and control. How do you make a child do what you want? You hurt them, or you take something away from them. Ozai both hurt Zuko and took away his home by banishing him. If Zuko wants to go back home, he has to find and capture the Avatar. It's that simple, but at the same time, it's also near impossible.

Flash forward to Canon Zuko and we see he has one child and he is a very loving father. Actually, he's the best father in the show. His experiences with growing up as the not so favorite child has made his choice to have one child easy. Probably because he and his spouse had a less than perfect relationship. This also may have influenced him to be protective of Izumi (as we can see he's still protective over her even at 90 years old) because of the loveless relationship his parents had. It was enough to damage him deeply when it came to relationships. This is likely also why he had trouble with Mai as well.

Headcanon space now...

Zuko loving Katara is what makes the difference here. Love is giving your partner the freedom to make their own choices and support them. As long as there is good communication, trust, and honesty. Something Maiko does not have, by the way. So it stands to reason that even with Nature Vs Nurture in the way of parenting, both win here. I'll tell you why Zuko's relationship with his parents here have no effect on why he would choose to have more children with Katara.

Because if written well, it's a very good relationship between them. We already know they work well as a team. The show gives us this. We know that Zuko absolutely cares about Katara. The show also gives us that. We also know they become lifelong friends. So why do they make great parents?

Because they rely on each other.

It has nothing to do with how they were raised individually, but everything to do with how they support each other narritively. They trust each other to make good decisions together. They rely on being honest with each other. They also communicate with each other. This by itself is the building blocks for a healthy and stable relationship. With that in mind, parenting is easier. There is no need to be afraid of becoming a bad parent because they hold each other accountable. It's a deep relationship. Having multiple children is easier because it is a loving relationship. There's no conflict besides the silly little arguments over simple things that happen all the time. It's just an overall healthy dynamic.

And that is what appeals to Zutarians.

While it was almost canon, I'm glad it isn't because Bryke would definitely not get it right. They tried to make Korra and Mako happen out of spite because they believe Zutara is toxic. It's not. Their children would turn out absolutely fine because Zuko would not change a thing about Katara. It's in the show. He doesn't try to change her because that's not his job. His job in TSR is to let her find closure. He offers it to her because he cares about her. Bottom line.

Anyway, I probably forgot what you said at this point because I just tend to go on and on, but I tried my best to stay on topic... ADHD is both a blessing and a curse.

#parenting is not about the past as long as you have a good partner#a bad relationship will force a parent to make decisions to protect their child.#if Zuko was like his father his partner would be the one making the hard decisions to protect their child.#if mai is Zuko's wife then it was not a good relationship.#zutara#relationships#parenting#anti bryke#anti aang

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

DESIGN REFERENCES FOR LI JINZHA

⚠️NOTE⚠️ I am NOT a researcher, meaning I did not go beyond his baike article for this post, so please don't take this post as a concrete, definite description of Jinzha. Remember that there are different versions of mythology characters all the time, and these are simply some of them. I'm only making this so others can have a starting point in designing him!

Any rbs with corrections/additions are highly welcome!!

Throughout my year of Li Brother Illness TM, I've seen some li brother designs which always makes me incredibly happy. However, I still thought it'd be neat if I shared some stuff that helped inspire my headcannons/designs of the li siblings. This one will be about Jinzha!

I hope this gives a little more insight to my beloveds while also generating more ideas for them <33

Jinzha is described as a handsome young man who wears light yellow/white Taoist robes. Sometimes the ends of his Daoist robes is drawn poofy which is so cute,, he is also depicted wearing a golden hair crown (束发金冠). Other figures like Sun Wukong and Lu Bu wear this too, but with pheasant feathers attached to it

There are also designs that depict him in armor!

SNAKES (蛇)

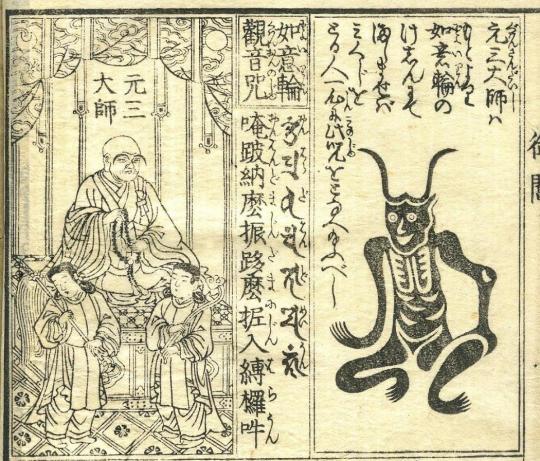

This is an older version of Jinzha, Bodhisattva Jundali Mingwang. He is a Buddhist figure, and can be seen decorated with red snakes and yellow-collared snakes around his body. He also has a spirit snake (灵蛇), which could either mean a magical snake or a fast and precise one. He uses it as a weapon, which I think means he flings the lil guy at his opponent and it just starts biting them (erlang shen strat with his dog)

While this isn't fsyy Jinzha, I still think it'd be neat to include snake motifs in Jinzha's design more,, plus I think it'd tie in nicely with his Dragon Stake :)

(Bodhisattva Jundali also wields other weapons such as a spear, a whip and a polearm that looks similar to a halberd (戟). Jinzha doesn't have any of these in fsyy, but just gonna put these here if you want more weapons to draw him with :>)

DRAGON STAKE (遁龙桩)

I've shown this weapon briefly here, but I'll show it again so it's much more organized! The Dragon Stake appears time to time in fsyy alongside Jinzha's swords, and is a weapon that can bind any opponent. It's commonly depicted as a pole with three rings. It seems to be able to change its size, growing bigger when in use. In fsyy, Jinzha would sometimes bind the enemy first with the Dragon Stake before finishing them off with his swords.

I was luckily able to find an illustration showing how it looks like in action!

This weapon was used by Jinzha's master before it was passed onto Jinzha. It's also what was used to subdue Nezha when he tried to kill Li Jing

More illustrations with Jinzha holding it:

more illustrations of Jinzha and the stake!

(^illustration credits: 苍狼野兽 on weibo)

VASE OF SWEET DEW (甘露宝瓶)

(For those who use his wikipedia article, the 'Ganlu Treasure Vase' is this.)

甘露 gān lù, meaning sweet dew, is a special substance that functions like holy water. It is contained in a vase, and Bodhisattva Jundali used this to defeat demons. This one doesn't seem to have a particular design, but it looks similar to the one that Bodhisattva Guanyin holds in her hand.

I did find some variations of it online though!

I hope this can give more ideas when drawing Jinzha! There aren't many english sources about him, so maybe this helps make researching a little easier <33

#jinzha#li jinzha#fsyy#chinese mythology#needed my dad to help translate for some of this pfff#jinzha was that kid with a hardcore reptile phase pass it around#manifesting for jinzha content

26 notes

·

View notes

Note

was subodhi teaching just taoism or some combination of taoism and buddhism?

While Puti was more known for the Taoist practices that Wukong learned about he does allude to express Buddhist allegories!

Puti is based on Subhūti one of the ten disciples of the Buddha, similar to how the Golden Cicada was as well. In Theravada Buddhism, he is considered the disciple who was foremost in being "worthy of gifts" and "living remote and in peace". In Mahayana Buddhism, he is considered foremost in understanding emptiness. Puti is a major figure in Mahayana Buddhism and is one of the central figures in Prajñāpāramitā sutras. Puti became a monk after hearing the Buddha teach at the dedication ceremony of Jetavana Monastery. After ordaining, Puti went into the forest and became an arahant.

Puti spent the first 7 years of Wukong's training with more mundane takes from writing, reading, cleaning, gardening, and meditation before teaching him more advanced arts. While Puti publicly chastised Wukong's desire to reach immorality he was secretly telling Wukong to meet him in the middle of the night to learn such secrets. And it is only after he masters these skills does he learn the 72 transformations and the somersault cloud.

Puti hits Wukong on his head three times similar to the life of Huineng who was another Buddhist monk known in early Buddism. Huineng was hit on the head three times by his master as well which lead to a quiet communication to come to his chambers and learn the Diamond Sutra. Wukong being a combination of both Taoism influences and Buddhist influences could represent Puti's own description within the story and how the story itself pushes for that connection of riding the gap between cultivation practices.

#anonymous#anon#anon ask#jttw#journey to the west#xiyouji#sun wukong#master subodhi#master puti#patriarch subodhi#ask

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

howd u come up with hiruko's character design :)

Most of the design was inspired by the mythological figure I based him on. I just tailored elements of his real-world history so they fit into the larger tapestry of LC and its themes.

Hiruko (AKA Ebisu) is one of the Seven Gods of Fortune. As a consequence of originating in Japan, he is the only one who doesn't have any Buddhist/Taoist influence. I gave him pink hair as a nod to Japanese cherry blossoms and his purely Japanese origin. The symbolic meaning of cherry blossoms in Japan ties into Hiruko's history and motivations nicely.

One of his many names is "the laughing god," which is why I nearly always depict him smiling and laughing.

I dressed him in traditional Japanese fashion because of his connection to ancient Japanese history.

Because he's known as the god of fishermen, I gave him a fishing hook earring hanging from a thread of fishing line. Given his connection to the Fates and their weaving within the context of LC, I liked the inclusion of thread in his character design. It was a way to marry his design with the item(s) he stole from the Fates. Webs/weaving/thread/tapestry are a big part of his role in LC, and it's one of the motifs I lean on when writing about him.

Since he is both the god of fisherman AND luck, I dressed him in red, which is known as an auspicious or lucky color in many East Asian cultures. It's also a color very commonly found in Shinto temples and is said to scare away evil spirits, so I thought he'd wear that color to try and signal to whoever saw him that he's a "good guy" and not a villain.

But that's also why I gave him blue eyes. In kabuki theater, blue is the color of villainous characters as well as the supernatural world, so they're a clue about his role in the story. Ocean blue eyes also connect back to the "god of fishermen" origin. Blue denoting the supernatural has some plot relevance as well.

Aaaand I guess the last notable trait I gave him was initial appearance of a child. This was partially inspired by Koenma, of course, who can change between a childish and adult appearance at will. A huge part of the Ebisu legend involves him being abandoned as a child, and I wanted a direct callout to that history from his first appearance. (I also think he took that form so people would underestimate him.)

That's the bulk of it, I think. Basically all of the most important bits come right out of Japanese culture and Hiruko/Ebisu's history.

Thanks for asking!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Selections from Hongmei Sun’s “Transforming Monkey”

Here it is! My compilation of quotes that I particularly liked from Sun’s excellent overview of the figure of the Monkey King. I hope you all enjoy them and find that they give you a richer understanding of an amazing text and its amazing monkey

---

Sun, Hongmei. Transforming Monkey: Adaptation & Representation of a Chinese Epic. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2018.

3: “Sun Wukong, known as the Monkey King in English, is the protagonist of the Ming dynasty novel Journey to the West (Xiyou ji). He is famous for his ability to shape-shift and ride the clouds, his size-changing magic rod, and his love of playing tricks. The longevity of his story reflects his popularity in Chinese culture: the ‘Journey to the West’ narrative is among the most malleable and long-lasting in Chinese literary history. With the repeated adaptations of the narrative over the centuries, the image of the protean monkey character has evolved into the Monkey King we know today.

Journey to the West is a one-hundred-chapter novel published in the sixteenth century during the late-Ming period. It is considered one of the four masterworks of the Ming novel, along with Water Margin (Shuihu zhuan), Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguo yanyi), and The Plum in the Golden Vase (Jinping mei). Loosely based on the historical journey of the famous monk Xuanzang (602-664), who traveled in the Tang dynasty from China to India in search of Buddhist scriptures, the story experienced a series of adaptations over hundreds of years before it was developed into the full-length novel, which recounts a mythological pilgrimage of the monk Tripitaka (the fictional Xuanzang), accompanied by three disciples and protectors he converts along the way: Sun Wukong (aka the Monkey King, or Monkey), Zhu Bajie (aka Zhu Wuneng, Pigsy, or Pig), and Sha Wujing (aka Sha Seng, Sha Heshang, Friar Sand, or Sandy). These disciples, as well as a dragon prince who transforms into a white horse as Tripitaka’s steed, are demons or animal spirits who have sinned…”

4: “Along the way, the group encounters and overcomes eighty-one tests, most of which involve demons and spirits who want to capture Tripitaka and eat his flesh in order to gain immortality.

The history of Journey to the West represents a process of continuous adaptations of Xuanzang’s story. The historical trip becomes a mythological journey in a world full of demons, spirits, Taoist gods, and Buddhist celestials. At some point—the actual origin and provenance remain unclear—the monkey follower of Xuanxang was added to a retelling of the story. Once included, the monkey figure grew in popularity until he replaced the monk as the main character and protagonist. It is owing to the long process of adaptation that today the Monkey King remains popular globally.”

5: “Literary analyses of the text have taken diverse and heterogeneous approaches but have predominantly focused on the religious and allegorical meanings of the tales. Little has been written about the Monkey King image in contemporary settings from the approach of adaptation, despite the obvious importance of this approach for Journey to the West, which is the product of repeated adaptations and maintains its influence in popular culture through ongoing adaptation today. Journey to the West is an accretive text, shaped by many hands at many times, and through interactions with many audiences.”

6: “…for lack of new data and more convincing interpretation, the Shidetang edition printed in 1592 is generally considered the ‘original.’ Although it is now generally accepted that Wu Cheng’en (ca. 1500-ca. 1582) is the author of the Shidetang edition of Journey to the West, this position is supported only by the lack of better candidates and more convincing evidence. Furthermore, the origin of the Monkey King character remains unclear.”

-“Through hundreds of years the Monkey King figure has shown amazing adaptability. His story appears in various forms in all media, crossing borders of culture and time, and his image has been frequently used in racial and political representations with social and political impact. Sun Wukong’s changes throughout modern history, intertwined with the construction and representation of Chinese identity, require a thorough examination.”

9: “Tracing further back from “Journey to the West,” two major sources for the narrative have been found: the historical journey of Xuanzang and the mythical figure of the Monkey King. Although the historical event clearly refers to the journey to India that the monk Xuanzang undertook in the seventh century, and the historical figure Xuanzang is accepted almost unanimously by scholars as the source of the character Tripitaka in the novel, the source of the Monkey King is unclear. Multiple figures may have influenced the image of the Monkey King, including Hanuman in the Indian tradition and monkey lore in the Chinese tradition. Each of these two major narrative lines revolves around one protagonist, who together become the two major characters in Journey to the West. Although the Monkey King figure was adopted into the narrative of the journey to India as only a helper of the monk, in later versions of the story the monkey becomes the protagonist, as becomes evident in Journey to the West, and more obviously in contemporary adaptations in China, where the Monkey King becomes the central figure with whom the audience identifies, and Tripitaka is portrayed with more negative features.”

11: “If one were to narrow the rich meaning of the Monkey King image down to a trope, it would like in the tension between the monkey, the human, and the god that coexists in the Monkey King. Because the tension exists in something as important and personal as the body itself, the image of Sun Wukong is therefore being used in a varied situations representing the struggle in identity. What the Monkey King can contribute to the issue of Asian American identity is the metaphor of transformation, the freedom one can attain in one’s body, and by extension in aspects of one’s social life.”

13: “Because of the fundamental multivalence in this figure, various political and ethnic groups use him as a representative to tell their own stories…Historically speaking, ‘Journey to the West’ is a product of adaptation. When the image of the Monkey King is added to the narrative and gradually takes the shape of Sun Wukong in Journey to the West, the influence of antecedents and the interlacing traditions of popular and elite culture together shape what we know as the protagonist of the sixteenth-century novel. A major transformation takes place in the mid-twentieth century during the reign of Mao Zedong, when the trickster monkey is collectively recast as a revolutionary hero. This heroic image remains the mainstream view until a new change is initiated by a Stephen Chow film, A Chinese Odyssey (1995), after which the image of Monkey takes a postsocialist turn. While the new transformation of the Monkey King as a hero is ongoing in China, in American popular media the Monkey image is adapted in a different manner, representing a mythical and antiprogressive oriental. Asian American adaptations, on the other hand, use the image of the Monkey King to illustrate the struggles of ethnic minorities in the United States, racial stereotypes, and ethnic identity. Monkey continues to shape-shift in new places and times, and each new Monkey collectively enriches our understanding of his image.”

15: “At the beginning of the hundred-chapter novel Journey to the West, a monkey is born from a primeval stone egg. This uncommon birth makes it impossible to place him into a distinct taxonomic category. ‘Born of the essences of Heaven and Earth,’ he is nonetheless still one of ‘the creatures from the world below.’ While the Monkey King belongs to both heaven and earth, his legendary birthplace is not easily locatable in either. According to the Buddhist cosmology introduced to the reader at the beginning of the first chapter, the Flower-Fruit Mountain (Huaguo Shan) appears to be located on the East Purvavideha Continent (Dong Shengshen Zhou), one of the four continents of the world. However, its geographic location relative to heaven and earth, or to the other continents that the monkey traverses in his journey, is never accounted for. To some extent the ambiguous birth and birthplace of the monkey contribute to his multivalent character.

At home on the Flower-Fruit MMountain, the monkey soon declares himself the Monkey King after demonstrating his prowess by crossing a waterfall and discovering a new territory, the Water-Curtain Cave, on behalf of the entire monkey kingdom. It is the first breakthrough in his life and is accomplished through crossing boundaries. Soon thereafter, and having become dissatisfied with a mortality that, by necessity, would subject him to the border between life and death, the self-proclaimed king sets off on a raft in search of a teacher who might guide him toward immortality. This journey brings him from the East Purvavideha Continent to the West Aparagodaniya Continent (Xi Niuhe Zhou), where he finds a master in the Patriarch Subhuti (Xuputi Zushi) on Lingtai Mountain.”

16: “Of no small significance, the master, one of the ten disciples of the Buddha, is described here as one who finds harmony among Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism. By means of the physical and spiritual journey from east to west, the monkey has acquired a name, Sun Wukong (Awaking to Emptiness), together with esoteric techniques enabling him to wield magical powers.

After returning to the Flower-Fruit Mountain, Sun Wukong successfully defends the subjects of his monkey kingdom by defeating a demon foe and thereby creating a name for himself among the demon kings. In addition, he befriends a number of immortal beings who occupy neighboring lands, one of whom in the Bull Demon King (Niumo Wang), who later becomes an antagonist of the pilgrims. By becoming brothers with these demons on earth, Sun Wukong posits himself as one of them. He tests his power in the water realms and convinces the dragon kings there to present him with their treasured magic iron, which becomes hi famous iron rod. He also creatures turmoil in hell when he deletes the names of his monkey tribe from the Register of Life and Death, hence attaining immortality, although unofficially. The sphere in which he can be active is thus enlarged to include the earth, the sea, and the underworld.

Heaven, having learned of the monkey’s mischievous behavior, appoints him as Supervisor of the Imperial Stables (Bimawen), in an effort to co-opt him. His territory is thus further enlarged to include heaven. This is an important step in his life since he is now recognized as a deity within the heavenly hierarchical system rather than an outsider demon. When Sun Wukong recognizes his low position in the celestial hierarchy, he returns to his mountain and lays claim to the title ‘Great Sage, Equal to Heaven,’ essentially declaring himself the strongest demon in the world in possession of an outlaw power on par with heaven’s. Dissatisfied with marginalization within one system, he simply chooses to create a parallel system and names himself its head. And when heaven is unable to take him by force, it once again must reabsorb the monkey peacefully by reaccepting him into the heavenly fold. Despite being officially recognized as the Great Sage, the Monkey King still constantly breaks rules in heaven, and ultimately creates havoc when he learns he is not invited to the Peach Banquet. The disgruntled monkey breaks off yet again from heaven, this time demanding that he replace the Jade Emperor…”

17 + 18 (for list): “…himself. Significantly, the domains that Sun Wukong has so far tested and conquered include the earth, water, hell, and the Taoist heaven. Being active in all levels of the mythic cosmos enables him to enjoy immense growth in his realm—but more importantly, he becomes effectively limitless.”

Sun Wukong’s rebellion comes to an end when he meets the Buddha. He accepts the wager the Buddha has proposed, which is to jump out from the Buddha’s palm. Failing to do so, since the Buddha’s palm can grow as fast as Wukong can jump, he is subsequently imprisoned under the Five Phases Mountain for five hundred years, which functions as a turning point in Monkey’s life and an intermission in the narrative. What Monkey goes through during this period is completely omitted by the narrative, which simply switches to the story of Tripitaka and the beginning of the journey. When the Monkey King reappears in the story, his life starts anew on a very different track.

The monkey is in due course released by the traveling monk Tripitaka, who becomes his master and gives him the name Pilgrim (Xingzhe). At the beginning the master is shocked by Wukong’s demonic behavior and worried that the monkey might be out of control. The Bodhisattva Guanyin responds by setting a fillet on the monkey’s head. The tightening of this band—in response to Tripitaka’s recitation of the Tight-Fillet Spell (Jingu Zhou)—enables Tripitaka to control the monkey’s actions. Henceforth Sun Wukong serves as Tripitaka’s protector and as leader of the other disciples. He becomes the monk’s most reliable defense against demons and monsters on their way to the West. In the following eighty-seven chapters, which are primarily a long series of captures and releases of the pilgrims by monsters, demons, animal spirits, and gods in disguise, Sun Wukong either defeats the adversaries himself or finds a natural or sociopolitical conqueror of the enemy to ensure victory.

In Journey to the West, Monkey’s life can be summarized as composed of two parts, with the Five Phases Mountain as the watershed. Before his subjugation by the Buddha under the Five Phases Mountain, his life can also be divided into several phases, each phase with a different name and identity:

I: Before Subjugation:

a. The nameless stone monkey

b. The Handsome Monkey King (Mei Houwang)

c. Sun Wukong (name given by Subhuti)

d. The Supervisor of the Imperial Stables (Bimawen)

e. The Great Sage, Equal to Heaven (Qitian Dasheng)

Intermission: 500 years under the Five Phases Mountain

II: After Subjugation

Pilgrim (Xingzhe)

18: “The five phases of the monkey’s life before his subjugation by the Buddha demonstrate the innate drive of the monkey to test every limit that defines his sphere. With each step the monkey takes in his life, there is a transformation, a breakthrough, and his magic skills allow him to transgress limits. Step by step he broadens his sphere, challenging every authority, until he is facing the greatest cosmic power (who is, interestingly, the foreign Buddha from the West, invited by the indigenous god, the Jade Emperor). It is the spirit that challenges all limits that identifies him as a demon, one of those who dwell outside of the space of heavenly order. Since hierarchical control is about keeping boundaries and maintaining order, this kind of nonstop challenge cannot be accepted. Monkey therefore has to be either considered as a challenge from the outside (a demon) or changed and co-opted within the system.”

--“The five hundred years serve as a narrative gutter, before which Monkey strives to surpass all boundaries—the patriarch of all beings—while after it the monkey becomes a servant, a pilgrim following the orders of a monk, confined by the magic headband. Before the gutter, he was a demon himself; after the gutter, he becomes a demon-subjugator and a demon killer. When encountering and fighting antagonist demons, the pilgrim monkey continually boasts to them about his glorious past as a demon monkey but the kills or subjugates them by himself or with celestial help. In this sense, the journey of the pilgrims is at the same time a story of demon-conquering and an account of the subjugation of the monkey himself.”

19: “He is simultaneously the one and the other, dual contradictions within one body.

But this is not only a journey from China to India. The Monkey King’s journey, far from unidirectional, is also full of upward and downward movement—he bounces between the heavenly gods and the demons and monsters on earth both before and after his submission. The nature of these trips does, however, change after his imprisonment. In the early phases of his life, the journeys up and down are carried out via his free will, whereas the later ups and downs as a pilgrim are mostly arranged by Guanyin and the other gods, as part of the trials of the journey. Just as his somersault never enables him to jump out of the hand of Buddha, his somersaulting up and down during the pilgrimage never gets him out of the determined trajectory of his life. He is only fulfilling his task, the mission of a pilgrim who works as a mediator.

The character of the Monkey King is fundamentally self-contradictory. In the earlier stage of his life, his is a self-important heroic rebel, but later he transforms into a loyal disciple of the monk master and a pious believer in Buddhist thought. Monkey does go through some transitional periods during the journey, including a few incidents in which he is in disagreement with, yet has to obey, Tripitaka, but later in the journey the narrative demonstrates that his understanding of the Heart Sutra often even surpasses that of Tripitaka.”

20: “Reflected by his names and titles, Sun Wukong juggles his multiple identities, some of which are sharply opposed to each other.”

21: “Rather than mediating between two opposite states, the Monkey King denies and deletes dualism and brings multiple and otherwise incompatible possibilities together.”

24: “As a narrative rejecting dichotomy, Journey to the West clearly rejects a simple division of the story into shouxin (controlling the mind, retrieving of mind) and fangxin (letting the mind go, exile of the mind). Not only is the ‘mind monkey’ always fond of his mischievous ways when he remains a follower of Tripitaka, in the two episodes of the ‘exile’ of the ‘mind monkey,’ he is never totally let loose either. In both cases he asks Tripitaka or Bodhisattva to take his head fillet off, but neither of them is able to fulfill his request. Ironically, although Tripitaka ‘exiles’ the monkey from the pilgrim group, his power over the Tightening Fillet remains. Monkey, on the other hand, is also never totally happy when being released. In the case of the first release, Bajie (Pigsy) has to resort to a stratagem to persuade the monkey to return: he lies to the monkey that the monster who had beaten the pilgrims does not take seriously of the name of Sun Wukong and his deeds in heaven five hundred years ago. It is in defense of his reputation as the ‘number one monster’ that the monkey leaves his Flower-Fruit Mountain and returns to rejoin the band of pilgrims.

In the case of the second ‘exile,’ the episode of the ‘double-mind monkey’ (erxin yuan), a fake Wukong commits a series of monstrous crimes in his name. While one ‘mind monkey’ is staking with the Bodhisattva, the other ‘mind monkey’ goes to strike the master Tripitaka unconscious, takes his travel documents, returns to the Flower-Fruit Mountain, and sets up another pilgrim band, ready for his own journey to the West. The resemblance of the two ‘mind monkeys’ deceives everyone except the Buddha, who sees through the fake Wukong and recognizes him as a six-eared macaque (liuer mihou). The use of a double of Wukong enables the narrative to literally grant the monkey the facility to be self-contradictory, with one Monkey being a pious follower of Tripitaka, and the other a monster who is even capable of beating his master. At the culmination of this episode, Sun Wukong uses his rod to kill the six-eared macaque,…”