#Class: Reptilia

Text

Range: North America, Certain islands in the Pacific & the Caribbean, Japan, & some parts of Europe

#poll#Class: Reptilia#Order: Squamata#Family: Dactyloidae#Genus: Anolis#Anolis Carolinensis#Range: Nearctic#Range: Neotropical#Range: Palearctic

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

A tiny Mediterranean House Gecko! Not Juice though-

#Phylum: Chordata#Class: Reptilia#Order: Squamata#Family: Gekkonidae#Genus: Hemidactylus#Hemidactylus turcicus#mediterranean house geckos#house geckos#geckos#lizards#reptiles

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Birds are class Aves.

Sure, under Linnaean taxonomy. But, well,

A) Linnaeus was a eugenecist so his scientific opinions are suspect and his morality is awful

B) he didn't know about evolution

C) he didn't know about prehistoric life

so his classification system? Sucks ass. It doesn't work anymore. It no longer reflects the diversity of life.

Instead, scientists - almost across the board, now - use Clades, or evolutionary relationships. No rankings, no hierarchies, just clades. It allows us to properly place prehistoric life, it removes our reliance on traits (which are almost always arbitrary) in classifying organisms, and allows us to communicate the history of life just by talking about their relationships.

So, for your own edification, here's the full classification of birds as we currently know it, from biggest to smallest:

Biota/Earth-Based Life

Archaeans

Proteoarchaeota

Asgardians (Eukaryomorphans)

Eukaryota (note: Proteobacteria were added to an asgardian Eukaryote to form mitochondria)

Amorphea

Obazoa

Opisthokonts

Holozoa

Filozoa

Choanozoa

Metazoa (Animals)

ParaHoxozoa (Hox genes show up)

Planulozoa

Bilateria (all bilateran animals)

Nephrozoa

Deuterostomia (Deuterostomes)

Chordata (Chordates)

Olfactores

Vertebrata (Vertebrates)

Gnathostomata (Jawed Vertebrates)

Eugnathostomata

Osteichthyes (Bony Vertebrates)

Sarcopterygii (Lobe-Finned Fish)

Rhipidistia

Tetrapodomorpha

Eotetrapodiformes

Elpistostegalia

Stegocephalia

Tetrapoda (Tetrapods)

Reptiliomorpha

Amniota (animals that lay amniotic eggs, or evolved from ones that did)

Sauropsida/Reptilia (reptiles sensu lato)

Eureptilia

Diapsida

Neodiapsida

Sauria (reptiles sensu stricto)

Archelosauria

Archosauromorpha

Crocopoda

Archosauriformes

Eucrocopoda

Crurotarsi

Archosauria

Avemetatarsalia (Bird-line Archosaurs, birds sensu lato)

Ornithodira (Appearance of feathers, warm bloodedness)

Dinosauromorpha

Dinosauriformes

Dracohors

Dinosauria (fully upright posture; All Dinosaurs)

Saurischia (bird like bones & lungs)

Eusaurischia

Theropoda (permanently bipedal group)

Neotheropoda

Averostra

Tetanurae

Orionides

Avetheropoda

Coelurosauria

Tyrannoraptora

Maniraptoromorpha

Neocoelurosauria

Maniraptoriformes (feathered wings on arms)

Maniraptora

Pennaraptora

Paraves (fully sized winges, probable flighted ancestor)

Avialae

Avebrevicauda

Pygostylia (bird tails)

Ornithothoraces

Euornithes (wing configuration like modern birds)

Ornithuromorpha

Ornithurae

Neornithes (modern birds, with fully modern bird beaks)

idk if this was a gotcha, trying to be helpful, or genuine confusion, but here you go.

all of this, ftr, is on wikipedia, and you could have looked it up yourself.

671 notes

·

View notes

Text

an update on neilbot's pregnancy that no one asked for

THINGS ARE HAPPENING. @thearoacemess IS ACCUSING ALL MAGGOTS OF NOT KNOWING ANYTHING ABOUT REPTILE PREGNANCIES AND SAYING THAT NEIL HAS A TUMOUR.

NEIL IS EXPERIENCING PREGNANCY MOOD SWINGS.

NO ONE IS SURE WHETHER HE IS PREGNANT WITH BABIES OR WITH EGGS.

ACCUSATIONS HAVE BEEN FLYING FROM AARON OF ME AND @random-doctor-on-the-internet, NEIL'S PARENTS, NOT TEACHING HIM ABOUT PROTECTION.

I THEN DEMANDED WHY @anadyomena AND @ivory--raven, PARENTS OF HAMPTER (@smspikyhampster) WHO IMPREGNATED NEIL THROUGH THE POWER OF GOD OR SOMETHING, DIDN'T TEACH HIM ABOUT PREGNANCY.

MAE IS ATTEMPTING TO DO RESEARCH ON THE DNA. NEIL IS AFRAID FOR HIS BABIES.

RAY HAS NOW GIVEN UP THE CASE. TENSIONS ARE RUNNING HIGH IN MY COURT.

@achilles-in-a-blanket-burrito HAS ENTERED. KIT SEEMS TO BEHIND ON THE EVENTS. HE IS DEMANDING CLARIFICATION. HAMPTER CLAIMS THERE IS A POLL ON HIS TUMBLR DECIDING WHETHER IT'S EGGS OR LIVE BIRTH.

DON'T DO PREGNANCY BETWEEN CLASS REPTILIA AND CLASS MAMMALIA KIDS IT'S NOT WORTH IT POOR NEIL.

#neil who is not here#neilbot#good omens mascot#weirdly specific but ok#good omens#asmi#maggots#the official maggots server of doom#maggots server#neil's pregnancy

72 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello

I hope you are having a pleasant day.

I have been interested in animal taxonomy for a while now and would like to spend more time working on it. Do you have any recommendations on sources, et cetera, that could guide me on how to start?

(I cannot figure out how to ask this anonymously, hope that is bot some sort of Tumblr faux pas)

Regards

I'm afraid I can't really recommend much as I don't own any books on the subject and I've learned the taxonomy I do know just by IDing bugs regularly and having to know the classes, orders, families, and genera that I see commonly. I primarily use iNaturalist for IDing and they organize everything there taxonomically which is hugely helpful.

Although even if there are good books on the subject, it's literally constantly changing, so they may become outdated very quickly.

I think if you want to get into it, it may be helpful to narrow your area of interest to at least a class (Insecta, Arachnida, Mammalia, Reptilia, etc) just so it's not such a huge undertaking.

Beyond that, maybe some of my followers have recommendations for resources?

P.S. - You can't ask anonymously because I have anonymous asks disabled to avoid rude messages. But this certainly wasn't any sort of faux pas!

144 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dragon Taxonomy

Every so often I get struck by the urge to try and make a somewhat coherent taxonomy for the dragons, because if HTTYD is meant to be ‘our world’ and the dragons are animals instead of like, magical beings who appeared out of the ether, they must have evolved.

I went through three iterations of this cladogram before settling on one I’m happy with (for now), so allow me to break it down for y’all:

For those who don’t know, Linnaean taxonomy (which I am using here) has seven main ranks, as well as sub ranks, which start off broad/general and get more and more specific. They are Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, and Species. Dragons are in the Kingdom Animalia, the Phylum Chordata and the Class…

Okay so I originally put them in their own class, but assuming they’re reptiles, they’d more likely be considered a subclass, or superorder, within the Class Reptilia. It’s up to interpretation.

There are two Orders grouped under Drakontes. The first is Nykteromorpha, which are all the dragon species with a wing membrane that attaches from the shoulders down to the hips. The second is Ornisteromorpha, which are all the dragon species with a wing membrane that attaches at the shoulder and sometimes partway down the ribs for more support. This is the biggest order.

Each Order has two suborders. As you can see from the cladogram, we have the bat winged dragons with short necks, the bat winged dragons with long necks, the bird winged dragons with short necks and the bird winged dragons with long necks.

So there are two Orders, four Suborders, and eight Families. The Families are named after the most well known dragon species in each of those groups, e.g: Nadderidae, Furidae and Groncklidae.

Four of those Families are in turn split into two subfamilies, for the dragons that (I think) are more closely related to the titular species, and the dragons that are less closely related to them. For example, dragons that are most closely related to Furies are in the subfamily Furinae, whereas those less closely related are in the subfamily Parafurinae, meaning ‘almost/close to alike Furies’.

I could be totally off about this (there’s literally no way to tell) but I tried to base it on what I know of real evolution and taxonomy, and on the dragons body plans rather than shared features. Dragons with similar physical characteristics seem more likely to be related than dragons that look almost nothing alike and just happen to have certain abilities in common, such as flicking spines.

I think that pretty much sums everything up. Thanks for reading!

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just got reminded by the Doctor Who wiki that the Silurians are also called Homo reptilia, and as a person with an anthropology background and decent knowledge of how evolution and taxonomy work, *eye twitch.*

No. Just. No. Two species have to be closely related to be in the same genus and I promise you reptiles and humans cannot be that closely related. No amount of convergent or divergent evolution can be responsible for that. Just no. Reptilia sapiens is better but also bad, because it's a dumb idea to give a genus the same name that's already used for a class, that's just asking for trouble - Reptilia is already the name of the class which contains all reptiles, not just the humanoid ones. And we know it has to be referring to a genus in this context because it's in the standard binomial naming system which uses genus followed by species, both in italics. The format is distinctive, you don't italicize a class, or a family, or a kingdom, or anything else.

In summary: grrrr. I'm mad about an inconsequential fictional thing that very few people would ever even notice.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why defining "birds" precisely is hard

(A reply to @lyxthen-reblogs that got too long and is now its own post)

A long time ago (in the 1700s), we didn't really have any idea of how birds came about - evolutionary theory itself would have to wait another century! And, we didn't have knowledge of extinct species either, or even of the fact extinction was a thing. Carl Linnaeus, when setting up the first taxonomical classification of life, grouped modern birds in the class Aves. Mammals were grouped in Mammalia, reptiles, amphibians and cartilaginous fish in Amphibia, bony fish in Pisces, arthropods in Insecta and all other animals in Vermes.

This first classification was pretty crude, and, around 1820, scientists like de Blainville and Latreille began distinguishing reptiles from "batrachians" as separate classes. De Blainville, pointing out similarities between reptiles and birds, labelled the former as "ornithoid" (bird-like) while amphibians were "ichthyoid" (fish-like). In 1825, Latreille fully separated amphibians (Batrachia, later Amphibia) from reptiles (Reptilia).

The first major turning point for taxonomy came in the next decades, as many fossils of now-extinct creatures were unearthed. In 1842, Richard Owen coined the term Dinosauria, then uniting the recently discovered Megalosaurus, Hylaeosaurus and Iguanodon.

But it wouldn't be until the 1860s that Darwinian evolution would highlight the flaws in the earlier understanding of separate classes. In 1863, Thomas Henry Huxley would suggest uniting birds and reptiles, creating the class Sauropsida the next year. Huxley was the first to suggest birds evolved from dinosaurs, comparing the recently-discovered Archaeopteryx (1861) with Compsognathus. As cladistics didn't exist back then, no attempt at precisely extending the definition of "bird" to extinct forms was made, even though Archaeopteryx was usually called "the first bird" (Urvogel).

Unfortunately, this hypothesis would be shelved for a whole century, leading to little progress happening in terms of understanding bird evolution. It wouldn't be until the 1960s and the Dinosaur Renaissance that the links between birds and dinosaurs would be rediscovered, with birdlike theropods like Deinonychus being unearthed. This would really accelerate with the discovery of extremely well-preserved feathered dinosaurs, starting with Sinosauropteryx in 1996.

With numerous fossils showing steps of a gradual dinosaur-to-bird transition, the question of defining the "first bird" came to be asked again. To try to answer this, Jacques Gauthier coined the clade Avialae in 1986 as all dinosaurs more closely related to modern birds than to deinonychosaurs. This included Archaeopteryx, which other authors used for an alternate definition of Avialae: "the smallest clade containing Archaeopteryx and modern birds".

Still, the conflict didn't end there. Fundamentally, there were many ways to extend Aves (as defined from modern birds) to past ancestors, and, in 2001, Gauthier and de Quieroz identified four. Avemetatarsalia, defined as any archosaur closer to birds than to crocodilians (including all dinosaurs and pterosaurs!). Avifilopluma, defined as any archosaur possessing feathers homologous to bird ones. Avialae, redefined as any dinosaur able to fly (and their flightless descendants). And finally, Aves or Neornithes, the crown-group (the last common ancestor of modern birds, and its descendants).

The issues were many. Avifilopluma became mostly useless as a definition as ornithischians, then pterosaurs, were found to possess filaments homologous with bird feathers. Virtually every bird-line archosaur (with the possible exception of the little-known aphanosaurs) could likely fit in this clade, and its content was too uncertain to be reliably used.

Meanwhile, Avialae had (and continues to have) three distinct definitions. Notably, the ability for flight itself proved to be a poor definition, as bird relatives (Maniraptora, including Deinonychus, Velociraptor, Oviraptor, and many other bird-like theropods) likely evolved flight several times, from the four-winged Microraptor to the bat-winged Yi qi. Truly, most maniraptorans were extremely bird-like: wings had evolved much earlier than flight itself, with even dinosaurs like Velociraptor sporting fully feathered wings despite being unable to fly.

So, what was left? The crown group Neornithes, a vaguely defined Avialae, a more extensive Maniraptora, the stem group Avemetatarsalia, and lots of confusion. Usually, Aves is taken today as referring to either Neornithes or Avialae, although Avifilopluma/Avimetatarsalia are also in use (for instance, the Sinosauropteryx discoverers used Avifilopluma, and considered it a bird).

But none of these definitions are inherently better or worse. They are all different ways of extending a definition made for modern creatures to have it apply to past ones.

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello!

Im finally sending another science thing!

studying zoology

Im back at my intial believe, I used to believe in the kingdom classifications as any young biologist would. Then I started believing in the domain classifications. And now im like, non clade taxonomy doesnt make any sense

so even the newly published paper asking for an empire or even a 3 life taxonomy structures are just.. trying to tape over the old sciences

I dont see a pro of a non clade taxonomy structure

It only made sense before we started DNA sequencing life

bc now we know that life only was created once in the entire history of Earth. So everything evolved from one thing

So have a taxonomy where there different types of life from the start is.. wrong

It only helps to keep the non scientific terms alive. Bc if we dont have the hierchy taxonomy we cant call only specific animals what we call them

like cats wont be just the things we casually call cats if we adopt a clade structure

And humans would be monkeys and apes depending on which clade u go back to

From what I read so far, biologists already use clade classifications in research. And microtaxonomists neontologists handle the kingdom classifcations later

And im kinda fine with that, but I wouldnt use the kindgoms in my head atleast

Disclaimer: I'm not a taxonomist so stuff i say may be wrong

honestly? the traditional biological ranking system sucks. i mean, its okay, but cladistics give the viewer much more information about what am organism is and how theyre related to others imo.

it also offers much greater room for nuance like in the case of birds and crocadillians. in traditional taxonomy, or at least the way i was taught in school, birds fall under class aves and crocadilians under class reptilia. this, ofc, implies crocadillians are closer related to other traditional reptilians than they are to birds, which isnt true. a cladistic approach, imo, is better suited to reflect those actual relationships.

Of course, this does lead to some interesting conclusions since, cladistically, once an organism is something, it will never stop being that thing. For example, this means all tetrapods are technically fish. However, personally I would not consider that a flaw but moreso a feature. After all, when would tetrapods stop being fish? There's no good point where you can accurately say they aren't that isn't super arbitrary. theres more to be said, but im tired so ill leave it at this for now

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Average Pacific Rim Imagines: The World Keeps Moving

Robots built for small robot tournaments often resemble jaegers, if they aren't just designed to look like miniature versions of famous jaegers.

In the US, midwestern cities swell in size as people leave coastal areas. Of course, these are just the ones who can afford to move. Many poorer residents remain stuck. Also, poorer residents of midwestern towns are evicted as landlords prepare to welcome wealthier residents.

You watch a kaiju scientist you follow on social media grow increasingly frustrated as they find themselves explaining repeatedly that kaiju are not reptiles because they're aliens and therefore not part of the class reptilia.

You know how there's tornado chasers? There are kaiju chasers. They follow kaiju around from a hopefully safe distance and make videos, take observations, etc.

Coastal cities pass ordinances prohibiting the construction of tall buildings near the coast. Not that anyone wants to build them anyway; the insurance rates are excruciating and few people want to live or run their business there.

You know of a guy on social media who has successfully predicted every kaiju arrival. The PPDC has seemingly taken no notice of him. He's also not a kaiju spiritualist; in fact, he seems like a pretty normal guy.

Controversy exists over whether to recycle the iron in old jaeger hulls into new buildings (such as housing, perhaps), new jaegers, or to leave the jaegers intact as historical relics.

Due to kaiju attack risk and the corrosive effects of kaiju blue on cargo ships, the cost of international shipping goes up. Any product that is or was shipped across the Pacific drastically raises in price. Many products you took for granted skyrocket out of your price range.

As the jaeger program fails, an arrogant billionaire claims that if it was privatized under his company, he could make it work. He describes his plans to optimize the jaeger program. They would never work.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Green Sea Turtle - The Port A Jetty, East Cotter Avenue, Port Aransas, Texas, USA

Joshua J. Cotten

Scientific name: Chelonia mydas

Conservation status: Endangered (Population decreasing)

Mass: 350 lbs (Adult)

Class: Reptilia

Domain: Eukaryota

Family: Cheloniidae

Genus: Chelonia; Brongniart, 1800

The green sea turtle, also known as the green turtle, black turtle or Pacific green turtle, is a species of large sea turtle of the family Cheloniidae. It is the only species in the genus Chelonia.

Green turtles are found worldwide primarily in subtropical and temperate regions of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, and in the Mediterranean Sea. In U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico waters, green turtles are found in inshore and nearshore waters from Texas to Maine, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico.

#The Port A Jetty#East Cotter Avenue#Port Aransas#Texas#USA#US#United States#United States of America#North America#Turtles#Turtle#Sea Turtle#Green Sea Turtle#Wildlife#TXWildlife#Chelonia mydas#Reptilia#Eukaryota#Cheloniidae#Chelonia

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#poll#Class: Reptilia#Order: Squamata#Family: Varanidae#Genus: Varanus#Varanus Komodoensis#Range: Australasian

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eroctavian, P.2~

#Phylum: Chordata#Class: Reptilia#Order: Squamata#Suborder: Serpentes#Family: Colubridae#Genus: Diadophis#Diadophis punctatus#ring-necked snakes#ringneck snakes#snakes#reptiles#my pets

0 notes

Text

Kiri & Ankha re-imagine

Kiri and Ankha are characters featured in the television show Mortal Kombat: Conquest. They are portrayed as two female reptiles, similar to that of Khameleon.

In alternative universe of MK New Era,Zaterran is not limited to shape shifting lizards;but also all type class Reptilia animals considered as Zaterran.Kiri's clothing designed is Korean hanfu & based on Scincella lizard (found in Korea & Japan) while Ankha's clothing is Egyptian robe & based on South Alligator Lizard.Their relationship is more than friends & family (they're not blood related)

#mk#mortal kombat#mk fanart#mortal kombat fanart#fanart#mortal kombat conquest#mk kiri#mk ankha#kiri and ankha#ankha and kiri

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

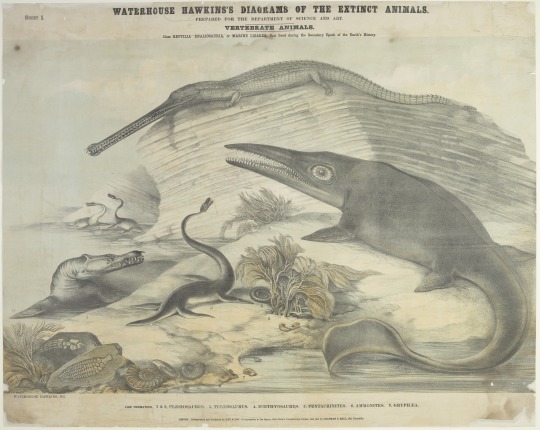

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's diagrams of the extinct animals, prepared for the Department of Science and Art, 1857?

"Sheet 1, Class Reptilia : Enaliosauria, or marine lizards, that lived during the secondary epoch of the Earth's history

Lias formation -- 1. & 2. Plesiosaurus -- 3. Teleosaurus -- 4. Ichthyosaurus -- 5. Pentacrinites -- 6. Ammonites -- 7. Gryphaea"

https://nhm.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/44NHM_INST/16ehpmm/alma9934228102081

#benjamin waterhouse hawkins#1857#plesiosaurus#teleosaurus#ichthyosaurus#pentacrinites#ammonite#gryphaea

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Desert Banshee

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class/Clade: Reptilia (Sauropsida)

Clade: Diapsida

Clade: Archosauria

Clade: Dinosauria

Clade: Saurischia

Clade: Eusaurischia

Clade: Theropoda

Clade: Neotheropoda

Superfamily: Coelophysoidea

Family: Coelophysidae

Subfamily: Allophysinae

Genus: Aravadromeus

Species: A. kakophonia (”dissonant runner of the Arava Desert”)

Ancestral species: Coelophysis bauri

Temporal range: late Pliocene to recent (3 mya - present)

Information:

While this creature superficially resembles an odd cross between a proceratosaurid and an ornithomimid, its origins actually lie far closer to the base of the theropod family tree: this odd creature is, in fact, a highly-derived coelophysid. Outside of its appearance, however, it has one notable difference: at some point within the last 30 million or so years, its lineage has made the switch from carnivory to herbivory. While the desert banshee feeds primarily on desert shrubs, fruits, leaves, and grasses, facultative carnivory has been observed: they are known to occasionally hunt and eat small birds, reptiles, and mammals, and females may do this leading up to when they lay their eggs. (But that’s a story for a little latter). As with many animals inhabiting the Arava Desert (though it also inhabits the grasslands and dry forests much further north in smaller densities and parts of the jungle to the east, though the latter may actually be a distinct but closely-related species), it is quite hardy, able to go long periods without food or water by storing fat in its tail.

In addition to their dietary switch, they have also developed unique behaviors to accommodate such changes: as the desert banshee is rather small, only around 8-9 feet in length, 3-4 feet at the hip, and around 70-80 lbs, it is a prime target for many desert predators, including the many species of carnivorous theropods and synapsids (including humans) who inhabit the region. As such, this animal is built for speed, being able to run up to 40 miles per hour in short bursts and preferring to flee from predators. However, if cornered or injured, it will not hesitate to put up a fight, making use of its two large ankle spurs to slash at its attackers. Additionally, it is nocturnal, preferring to travel at night to both avoid the scorching desert sun and to find new feeding grounds. While the obvious assumption would be that these animals would additionally flock together for protection, desert banshees deeply detest sharing space with congeners, and territorial confrontations can get bloody very quickly. However, it frequently travels with large flocks of ornithomimids for protection. The relationship this creature has with its larger distant cousins may be described as a form of commensalism: in exchange for protection, the desert banshee acts as a watchman of sorts to the ornithomimids, alerting the flock when predators are near with the deafeningly shrill, shrieking call that gave it its name. (Among its repertoire of other sounds are clucks and “drums” to communicate with its ornithomimid protectors long-distance and hissing when threatened or otherwise angered). In a rare example of non-primate social grooming, this creature will readily allow the ornithomimids it lives around to groom its feathers and remove parasites.

Just about the only time when these creatures will tolerate one another is when they are ready to mate: while these animals mate year-round, most mating occurs in late spring to early summer. With only slight sexual dimorphism, the males and females are not always easy to tell apart. Both have the same coloring: a white crest with black stripes, a white beak with black spots, creamy blue skin, dark blue spots on the wattle, grey feathers with black bands, and brown-to-black eyes. However, the female being able to distinguish herself by her warbling call which signals she is sexually receptive. Flashing his bright wattle, the male will flick his head up and down as part of a mating dance to get the female’s attention. If she accepts his display, the pair will walk side-by-side in synchronized movement, warbling and cooing while bobbing their heads up and down. After this display is over, the pair will mate and go separate ways. In the few weeks leading up to laying her clutch, the female may become facultatively carnivorous in order to obtain the calcium needed to produce her eggs. She will lay a clutch of 3-5 eggs in due time, and after a few weeks, they will hatch. However, she can retain the eggs inside her for an extended period of time until conditions are favorable or to synchronize the birth of her chicks with those of the ornithomimid flocks she follows. For the first 1.5 years of their life, the young are dependent on their mother as they reach near-adult age, at which point they are chased away and must find their own herd to follow. By 2.5 years, they will have reached sexual maturity and will be ready to mate, and if they can successfully avoid predators, they can expect to live 12-14 years in the wild and, if born in captivity, 20-30 years.

This species’ relationship with humans is one which is both riddled with mutualism and marred by tragedy: the desert banshee’s naturally social nature makes it exceptionally tame when raised in captivity, and some nomadic Lowland Xenogaean tribes keep them as their equivalent to sheepdogs. They are also known to be quite affectionate with their caretakers. Their ability to run fast in short bursts has also made them quite common as race animals which betters will gamble on. This species is also a frequent pest in the desert city of Tairokôna, where its habit of eating local crops and decorative plants have put it at odds with the city’s denizens. In addition to being used as a shepherd animal by Lowland Xenogaeans, they have also long been a source of food, with cut marks on fossil bones dated to around 50,000 years ago indicating that ancient humans in the area butchered and ate these animals. At one point, wild desert banshee numbers were driven so low due to pressures put on them by human hunters, that these animals experienced a bottleneck where smaller animals went on to breed and pass on their genes, meaning the modern population may be as much as 15% smaller than the Plio-Pleistocene variant of this species. Thankfully, its numbers have rebounded significantly in modern times, albeit they are still proportionally small and at risk of extinction in the wild, with only around 30,000 wild specimens across their entire range. At one point, this animal was also one of most trafficked and poached animals in the entire region, being hunted specifically for its bony crest in addition to its meat. Though its numbers rebounded significantly, there are a number of zoos and private collections across the world which still have illegally-bought desert banshees and their goods, particularly in the United Arab Emirates and Qatar. Even amongst Xenogaean aristocracy (Xenogaea being the larger of 1 of 2 nations inhabiting the archipelago), this animal is frequently seen as an exotic pet, and the King of Xenogaea, Tlahula I, has an entire stable of captive-bred desert banshees which have been selectively bred for several generations. Nowadays, most desert banshees killed for human consumption are captive-bred, with some debate over whether or not they may be undergoing domestication and if the captive-bred populations should be counted as a distinct species or subspecies from the wild one. However, the lack of morphological differences would seem to suggest that the captive-bred population are merely just that: captive-bred specimens of a wild species. Fossils of this species go back to at least the late Pliocene around 3 million years ago, though similar species are known from fossils in what is now the western grasslands as far back as the Eocene some 34 million years ago. Genetic divergence suggests it diverged from its closest living relatives over 150 million years ago, predating the split of most modern mammal lineages.

#novella#speculative evolution#fantasy#scifi#scififantasy#speculative biology#speculative fiction#speculative zoology#worldbuilding#fantasy worldbuilding#fantasy creature#sci fi creature#sci fi#scifi worldbuilding#creative writing#creature art#creature#coelophysid#coelophysis#dinosaurs#original species#spec evo

6 notes

·

View notes