#Peritio

Text

Ok so ...

Filament fever stage is interesting. One thing to point out is that the sculpture at the side of the stage. The animal sculpture looks like a deer with wings:

It's also in Meiko's trained card:

But for the virtual shop merch. Instead of the same animal, the merch instead has the pegasus instead as the sculpture:

So why the 3dmv stage did not use the pegasus and instead use deer with wings? The deer with wings that we know of is Peryton. Which, is similar to pegasus. A mythical beast.

One of the things about Peryton is that the Peryton can "casts the shadow of a man until it kills one during its lifetime, at which time it starts to cast its own shadow".

This sounds very similar with Tsukasa's gacha banner name:

The text design here has a wing at the y. So what if, instead of the wings belong to a pegasus or a phoenix, the wings actually belongs to a peryton instead?

Also, although unclear, the peryton may derived from the Latin form of the Greek name of the fourth month on the ancient Macedonian calendar (Peritios, moon of January).

Coincidently the next wxs event, Rui event, starts on January. And there's also the moon in the filament fever 3dmv:

So I wonder if Tsukasa is now a peryton instead of a pegasus. Since there's some other lore point out that when the peryton finds its shadow, it can transform into a genuine bird. Like the star Tsukasa admires which is compared to the phoenix. Which is also a bird.

#project sekai#tsukasa tenma#wonderlands x showtime#wonderland sekai#rui kamishiro#wxs meiko#prsk analysis#prsk theory

191 notes

·

View notes

Note

TIL the Peryton wasn't named until 1957 and that its historical basis is tenuous at best, how's your day going?🙃

Also it wasn't even called Peryton, the original Spanish version calls it Peritio!

Day is going stressful but thanks for asking! 🙃

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Serie de ilustraciones de diversas mitologías del mundo, realizadas para el "Diccionario Universal de Criaturas Fantásticas" de Luciano Hernandez. En orden de aparición:

Akangüé: Dueño de los Pájaros en el folklore guaraní.

Blemias: seres de la mitología greco-romana.

Leszi: proveniente de la mitología eslava.

Nyarlathotep: Una a la que le tengo un cariño especial, aunque no es de ninguna mitología o folklore tradicional se ganó un lugar en el Diccionario directo desde el ideario de H.P. Lovecraft.

Peritio: Otra criatura que técnicamente no pertenece al folklore o mitos "tradicionales", el Peritio, imaginado por Borges, se ganó un lugar en el imaginario colectivo... al punto que incluso llegó a aparecer en compendios de monstruos en Dungeons and Dragons (entre muchas otras referencias en la cultura popular)!

Quetzalcoatl: serpiente emplumada de la mitología azteca.

Rakshasa: seres de la mitología hindú.

Quedan más en el tintero, pero por ahora simplemente les recomendaré leer el Diccionario Universal de Criaturas Fantásticas Imperdible lectura, donde no sólo van a poder encontrar aún más ilustraciones de las que he estado subiendo, sino también conocer más sobre estos seres y muchos otros, guiados por el enorme conocimiento del autor.

#mythical creatures#mythology#myths#folklore#folklore creatures#creature design#creature art#cthulhu mythos#slavic folklore#roman mythology#greek mythology#hindu mythology#aztec mythology

43 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi !

I'm so fond of your sketchs !! Will you draw more mythological horses (kelpies, backahasts, each uisges, alastyns, unicorns, sleipnir, pegasus...) ? Or others mythological creatures like wolpertingers, valravens, peritios, jackalopes... ?

I would like to draw more often with pen ball but I just don't practice enough and the result is not okay ^^

Have a good day !

I'm very happy to have found your blog :)

Thanks!

It kind of depends on how I'm feeling, I'm generally drawn to more realistic subjects but since it seems like quite a few people enjoy my more mythologicaly inspired work I will try to do some more. I'm probably less likely to attempt mythological creatures that aren't horses, but I do like the idea of being a bit more artistically adventurous at some point. A lot of this uncertainty is to do with the insecurities I feel about creating more imaginative art.

I have actually painted a troll but it was a couple of years ago and in the style of John Bauer. I'm not sure if that counts but I've included it here anyway.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

peryton

This isn't quite a real word, but since that has never stopped me before, I looked around to see what I could find about its usage. A peryton is a mythical beast, composed of the body of a stag and the wings of a bird. They're actually quite majestic in a lot of the artwork depicting them. Also fairly irrelevant, but I think it's interesting it is an anagram for entropy.

The term was coined in a very interesting book, the title of which is A Book of Imaginary Beings in English, by Jorge Luis Borges and translated by Norman Thomas di Giovanni. Its original Spanish title from the first 1957 printing is Manual de zoología fantástica. The book received a few updates over the next couple of decades before landing on the final Spanish title, El libro de los seres imaginarios, in 1969.

There is a fairly long, but very interesting passage on them in the book. Their most pertinent details are originating from Atlantis, having the shadow of a man until they manage to kill a human, at which point their shadow is restored to their own figure, and being very bloodthirsty, violent creatures.

I found fleeting mentions of similar beasts before Borges' book, but none especially substantial, suggesting there was either predecessor to his creation or some inspiration for it. Either way, this particular version of the concept came from Borges, who originally penned it as the Spanish peritio.

However, this word has gone on to accumulate more meaning, and after a publication by S. Burke Spolaor et al., the term was adopted into astronomy as meaning "a terrestrially originating burst of radio waves." (As someone who is very not an astronomer, I can't explain what this means, but apparently you can produce them by opening a microwave door prematurely).

#wiktionary.org#perseus.net#Henry George Liddel Robert Scott A English-Greek Lexicon#dianeduane.com#https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stv1242#Oxford University Press: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society#linguistics#language#history#etymology#mythology#beasts#creatures#peryton#astronomy#myths and legends#Spanish#English#books#translation

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

They are not related and yet they go so well together

#look at the dates it was planed since 2019 ahaha im so slow#jackalope#skvader#peritio#wolpertinger#bird#pheasan#deer#rabbit#hare#the Known Ones#notes#compendium#diagram

2K notes

·

View notes

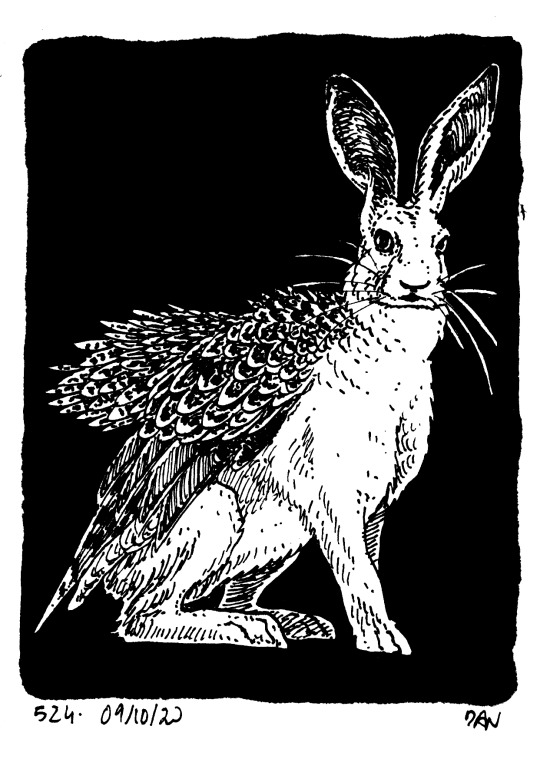

Photo

Peryton sketch

The peryton is a mythological hybrid animal combining the physical features of a stag and a bird. The peryton was first named by Jorge Luis Borges in his 1957 Book of Imaginary Beings, using a supposedly long-lost medieval manuscript as a source.

The peryton is said to have the head, neck, forelegs and antlers of a stag, combined with the plumage, wings and hindquarters of a large bird, although some interpretations portray the peryton as a deer in all but coloration and bird's wings. According to Borges, perytons lived in Atlantis until an earthquake destroyed the civilization and the creatures escaped by flight. A peryton casts the shadow of a man until it kills one during its lifetime, at which time it starts to cast its own shadow. A sibyl once prophesied that the perytons would lead to the downfall of Rome.

In Borges' original Spanish edition, the word is given as peritio so the presumptive Latin original would be peritius, which happens to be the Latin name of the fourth month on the ancient Macedonian calendar (Peritios, moon of January). The connection of this, if any, to the peryton is unclear. As at least one depiction of the Peryton - namely on the late medieval battle standard of the Dukes of Bourbon - pre-dates Borges' description, he clearly was not its inventor, though the creature's exact origins remain unclear.

#Peryton#European Folklore#Folklore#Mythological Creature#Legendary Creature#Digital Art#Pencil Sketch

85 notes

·

View notes

Note

This is probably a very stupid question, but how did the Ancient Greeks measure time (in terms of years and months) ? What was their calendar like? What year would Alexander have viewed himself to be living in?

I love these sorts of daily-life details, so I may have got a little carried away…. Before I get into the weeds, however, I want to make everyone aware of a reference resource:

E. J. Bickerman, Chronology of the Ancient World. Thames & Hudson, 1968.

Yeah, it’s old now, but Bickerman spent most of his career on dating puzzles, and I don’t think there’s anything recent to match it. When I first was told about it years ago in my historiography class, I practically bounced off the walls. (My fellow grad students thought I’d lost my mind.)

I’m not sure of the best way to address this query—topically or geographically—but I’ll go with topically. I’ll also say upfront that I’m unfamiliar with Egypt, so they’re not much mentioned. Also, if you want more details on any particular system (Roman, Athenian, Babylonian, Jewish), there are plenty of online resources.

Long-count Calendar

How to number years across a span? Regnal years was most common in antiquity: year 1, year 2, year 3 of ___ king. Also, king lists detailed how long ___ ruled. The Ancient Near East (ANE) excelled at chronologies; we have some that go back to Sumer. That’s pre-Bronze Age. The span of some reigns can be deeply problematic (e.g., mythical), but we have the lists. Fun note, Neo-Assyrians named years by its major military campaign. Tells us a lot about them, no?

What about places without kings? Greece, Rome, Carthage?

The Greeks had several systems, internal and panhellenic. Internal systems often dated by the name of a prominent city magistrate. In Athens, that was the eponymous archon, in Sparta, the eponymous ephor, etc. The panhellenic system used Olympic years. In Dancing with the Lion, if you look at date plates before sections, that’s what I used. It’s a 4-year system, so, “In the year of the 97th Olympiad,” “In the first year of the 97th Olympiad,” “In the second year…,” and “In the third year…,” then we’re to “In the year of the 98th Olympiad…” In modern annotation it’s Ol. 97.1, Ol. 97.2, Ol. 97.3, Ol. 97.4. From (our year) 776 BCE down into the Roman Imperial era, the Olympics made useful anchor dating for the eastern Mediterranean (Magna Graecia).

Rome had its own system: two in fact. It counted years by both consuls, but also AUC = ab urba condita … “from the founding of the city.” Carthage used a similar system involving their two senior Judges for their senate.

When it came to “world histories,” authors such as Diodoros Siculus used several systems: Olympiad, Athenian archon, and Roman consuls. It gets a bit unwieldy, but is about as universal as we have for the Med until Christianity took over everything.

Yearly Calendars

Much of the ancient world used lunar (354 days), not solar (356 days) calendars. Yes, they knew a lunar year didn’t line up with the solar, and they used “intercalation” to fix it, avoiding summer festivals being celebrated in winter. Either a 13th month was needed every 3 years, or they added a few days to months here and there, making a “lunisolar” calendar. We have an intercalated day in our own calendar: Feb. 29th in Leap Year. To fix a calendar, however, an “anchor” is needed. This anchor is usually a solstice or equinox, which may (or may not) correspond to their New Year.

Our modern (Western) world places New Year’s in the dead of winter. But many pre-modern calendars put it in spring. Makes sense: life renews, it’s a new year. The Babylonian New Year was decided by the spring equinox—first new moon after—which pattern affected most of the ANE.

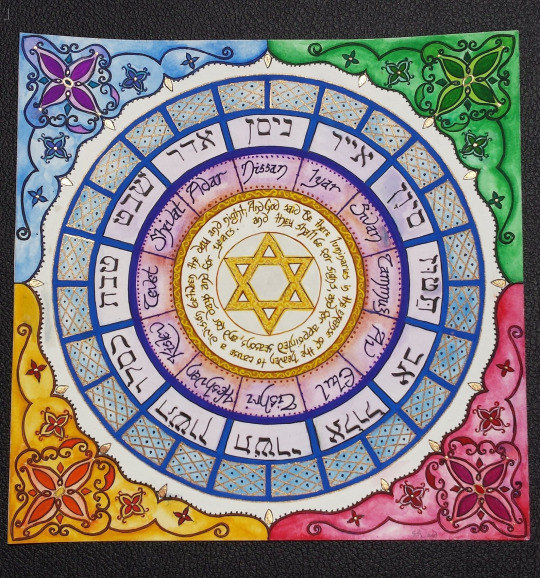

The Hebrew New Year (Rosh Hashana) is in autumn, but their first month (Nisan) is in spring. (They also have a New Year for Trees! Tú bish'vat. How cool is that?) Wanna know when your Jewish friends are having a holiday? Use Hebcal, the gold standard.

MANY ancient cultures have more than one calendar running at a time. So do we. Working in the uni, I have the “normal” year, but also the “academic” year to keep up with.

Despite the dominance of certain early systems like Babylon, counting the new year was specific to a region and people, and their religious traditions. No single Greek new year tradition existed. Both Delos and Athens used the first new moon after the summer equinox: early July. The Macedonian calendar seems to as well, so Alexander was born in the first month of the year. Other city states were different. I’ve forgotten most but do remember Sparta’s is in autumn because their new year almost falls on my birthday.

Remember, although we today talk about “ancient Greece” as if it were a country—it wasn’t. There was a landmass called Hellas, but each city-state was independent, and had its own laws, gov’t, coinage, and religious cult. Too often “Greek” winds up being conflated with “Athenian,” because we happen to have the most evidence from ancient Athens. But both Athens and Sparta were weirdos. Corinth, Thebes, Argos, Mytilene, Cos, Eretria, Miletus…all were a lot more typically Greek in their gov’t systems, etc. There were also 3 (or 4) different branches of Greek: Ionic-Attic, Doric, and Aeolic. When we talk about reading the “ancient Greek” language today, most people mean Attic Greek, or even Koine Greek (Hellenistic era common Greek).

That means every city-state had its own calendar, connected to its own festivals.

In fact, most city-states had several: sacred, civic, etc. Athens had a 12-month lunar calendar for festivals, but a 10-month civic calendar corresponding to the 10 tribes for Assembly business. Originally, they had only 4 tribes, not 10, so political changes meant calendar changes.

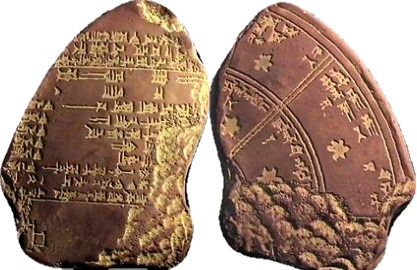

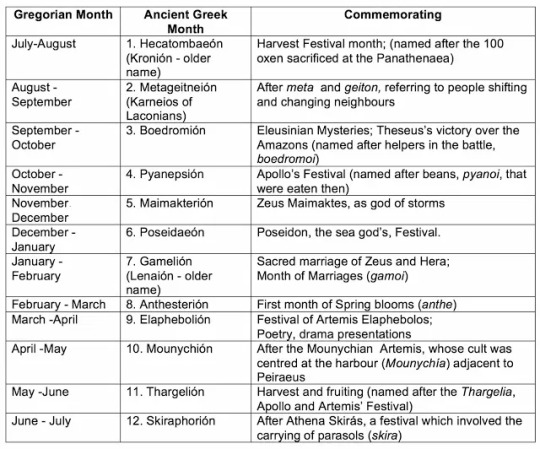

In each city-state, month names were derived from the major festival for that month. We have the complete month names for only a few: Athens is one and (fortunately for me) Macedon is another (specifically Ptolemaic, but it’s likely the same as the Argead). Below “Ancient Greek Month” REALLY means “Athenian month,” which annoys the hell out of those of us who don’t consider Athens the be-all and end-all of Greek history!

Because their months were lunar, they bisect our months, e.g., July/Aug = Athenian Hekatombian or Macedonian Loos [Alexander’s birthmonth], Jan/Feb = Athenian Gamelion or Macedonian Peritios [probably the month that gave Alexander’s favorite hound his name: Peritos]. Likewise, as the Athenian new year began in midsummer, dating ancient events also bisects. You’ll see 342/1 to designate the year from July of 342 BCE to June of 341.

As mentioned, most places used lunar months as the most basic time-keeping, but the moon isn’t the only way to make a “month.” Rome originally had 10 months of 30/31 days, adding 2 later, which is why our 12 months have Romanesque names.

Just remember: NO UNIVERSAL SYSTEM for months.

What About Weeks?

A seven-day week is borrowed from the Jews via Christianity. Both Jews and Egyptians had a dedicated day of rest. (For Egypt, the 10th day.) In most places, however, days off were festival related. Every month had festivals, which might last from half a day to several days in a row. You worked…took off for a festival…then you worked. No regular day of rest. (For the modern weekend? Thank unions and the Labor Movement!)

How did others subdivide a month? Athenian months were c. 30 days, divided into 10s: 1-10, 11-20, 10-1. Yup, the last is backwards. But dating also counted waxing and waning moons. So the new moon began a month, the 7th of the month would be the 7th waxing moon, the 24th the 6th waning moon. This is the Athenian system. Other city-states are less clear, but probably similar.

Romans had kalens (1st), nones (7th), and ides (15th). Nundinae (market days) means 9th, but were really the 8th day. The 7-day week is late Imperial and, again, owes to Christian take-over of Jewish weeks.

Most systems had “auspicious” and “inauspicious” days for religious activities, civic activities, and business activities. Don’t start anything on an inauspicious day! (These were manipulated, especially in Rome, but that’s a whole different discussion.) The closest modern equivalent I can think of is Mercury Retrograde. 😊 Although in modern Greece, signing a contract on a Tuesday morning is bad juju, or May 29th. Constantinople fell on a Tuesday morning May 29th, 1453. We might, in America, consider 9/11. Who wants to open a business on 9/11?

The Horai (The Hours)

When did the day begin? Again, the ANE and Med are different. In the ANE, day typically began at sunset. So yes, that’s why the Jewish shabbat starts at sunset on Friday and lasts till sunset on Saturday. (If you didn’t know, the Jewish “day of rest” isn’t Sunday, but Saturday.)

For Greece and Rome, et al., day began at dawn. Each day was then evenly divided between day and night, so there was no standard length of an hour. It depended on the time of year. Each half had twelve hours, subdivided into 4 groups of triads. Originally in Greece it seems there were only 9, not twelve, but they increased to match the lunar months. The division of 4 groups of triads also yielded the 4 seasons of 3 months each. Hora was initially a season, not an hour.

In any case, dawn was always the first hour, noon the 6th, sunset the 12th. Same deal for night (twilight, midnight, pre-dawn).

This is great for military and civic purposes, but most people tended to refer to daytime divisions more generally: dawn, midday, etc. And there was nothing like minutes or seconds. That’s totally modern. Closest, they might come would be to count “breaths.”

The gnomon (sundial) was the chief way to measure hours, as it matched longer or shorter days. But it’s kinda hard to use a sundial at night, or on a cloudy day, or inside. Night hours were approximate.

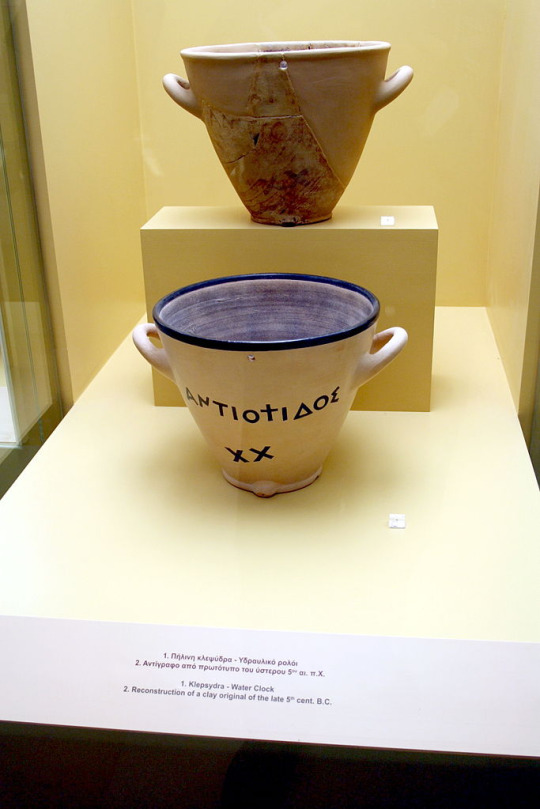

The water clock (klepsudra) was first popularized in Greece in courts and the Assembly (to time speeches), but spread to other use, for inside or on shady days. Yet water clocks are unwieldy to carry around.

The Romans did have portable sundials (below), but again…needs the SUN. Btw, I should add that sundials aren’t only a Greco-Roman thing. The Chinese had them too. By contrast, the sand-clock or hourglass is a medieval invention. Won’t find them in the ancient world.

#time-keeping#calendars#time in the ancient world#months in the ancient world#ancient Greece#ancient Rome#ancient near east#Jewish calendars#sundials#the Horae#The Hours#Classics#ancient history#ancient Mediterranean history#asks

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peryton

Perytons (peritio in their original Spanish) are a fairly recent creature, first seen in Borges’ Book of Imaginary Beings in 1957 although supposedly based on an old Medieval manuscript. Borges himself was Argentinian, though he claims that the peryton hailed from the lost city of Atlantis.

A peryton is a hybrid creature between a bird and a stag. Some variations cast it as a winged deer, but it is more accurately a deer with a bird’s wings and hind quarters. It casts the shadow of a man up until the point where it kills a man, at which point it casts its own shadow.

I also remember (though I can’t remember where I learnt this) that peryton’s were the mounts of the dead and could travel great distance at great speed. In the particular story I’m thinking of a wounded traveller called on a peryton to take him to safety; the peryton carried him as requested, but would not let the traveller dismount. The traveller had to trick the peryton into tangling its antlers in the trees so that he could leave it and return to the land of the living.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Borges invented the peryton" factoid actually slight translational error. In the original Spanish-language version of his Book it is called the peritio. The English translation is an outlier adn should not have been counted

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Borges’s Peritio, the 149th Known One.

#im dring flying bastards lately#Peritio#Peryton#Borges#jorge luis borges#deer#bird#pheasant#the Known Ones#596#octem 75#terra 3#chimera#monster

253 notes

·

View notes