#accepted: troilus

Note

Some started called gay men achilleian as in emphasize the same term lesbians give on the term "Sapphic love" which doesn't make ANY SENSE.

Firstly Sapphic comes from the Greek poet Sappho who lived on the Greek Island Lesbos and was famous for her romantic poems.

Achilles is just a character in a story by Homer written thousands of years ago mostly remembered for his complex character, his rage. His love for Patroclus may be for debate, but soulmate love is also platonic as it is romantic.

Achilles was never a gay icon before Miller's fiction book and the Iliad is a masterpiece of literature and his character is waaay more than his sexuality which also isn't labelled or certain either so why people are having a YA novel be the source material for his sexuality?

Interesting question.

I do not believe Miller to be responsible for the queering of Achilles. In fact, if you listen to interviews with her, her reasons for a queer interpretation are thoughtful and thorough. Namely, that a “bomb seems to go off” when Patroclus is killed. She believed his consequent actions to be most aligned with those of a grieving husband.

The novel’s earliest draft actually began as an academic essay after she directed Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, which characterizes Patroclus as more effeminate than Homer’s representation. Miller’s narrator is more closely aligned with Shakespeare, actually.

If you go further back, you have other ancient Greeks commenting on and disputing not whether or not Achilles and Patroclus were having sex, but who topped.

Returning to the Iliad itself. I believe it is most accurate to say both men were bisexual. They live together in fairly close quarters. If they aren’t partners, they are at least comfortable performing sex acts in front of one another with their concubines. I would say that Miller’s version where they “rescue” the girls but never sleep with them is a bit far fetched. However, there is also some implication that the two men shared a bed. I’d ask yourself, if this were a man and a woman, would I be thinking this hard as to whether they were a couple? Probably not.

There is finally the issue of the word “philtatos” itself. The -tos suffix is superlative. There’s no way around the translation “most beloved.” I am dubious of Victorian scholars who were bent on inserting “comrade” or “companion” in there. I call censorship.

So yes, I think queer interpretation really is an interpretation and not a fetishized, contemporary theory.

However, I’d like to address your point of platonic love and it’s societal value. To the understanding of many, (actually, Aristotle) “philia” between two men was the most fulfilling relationship possible. This creates a bit of a confusing wrinkle in ancient literature, doesn’t it? Gilgamesh and Enkidu’s behavior certainly queer-codes in 2023, but they come from a context which de emphasized women and their capacity to relate to male partners. So sure, maybe Patroclus and Achilles are meant to be broing out this whole time mainly because Briseis is too stupid and too afflicted by wandering-womb to understand them. I guess that’s the book you could read.

Maybe you wish to shelf that criticism and what you saw was a rich friendship. To challenge my own point above about if they were a straight couple, we accept completely different behavior from two women. There’s no reason friends can’t share profound intimacy and physical affection without any sexual connotation. You can’t say the death of a dear friend isn’t big enough to serve as the poem’s crisis point. You’re right — especially considering that these boys were raised together and have been living together and at war together their whole lives. The same could be said of David and Jonathan, another popular queer speculation. A sexual relationship is not needed to validate such a bond.

I still think they were having sex. I am sorry to have nothing to cite but remember my own mother explaining a queer reading of the Iliad to me before The Song of Achilles was even published. I believe she was teaching the Aeneid at that time but doing some background research. She mentioned specifically reading that sex was normal and encouraged between specifically infantry and charioteers. The idea was that by forming a sexual/romantic bond, those men would be more effective as a team. The point being, this is nothing new.

I want to speak to your comparison to Sappho, because it is pertinent. The prose of The Song of Achilles is heavily inspired by Sappho’s style. Her intention with that particular project was to focus on the perspective of a sidelined character and give him an intimate, lyric voice. That was the point. For her purposes, Achilles is a sexual and romantic icon because of who is telling the story. Contrast even the openings, “Sing, muse of rage of Achilles,” to, “my father was a king, and the son of kings.” One is invoking Calliope to tell us an epic about an angry little man and the other sets the expectation that you’re going to get his life story. If you read this book, you will get a subjective one-to-one experience of Achilles as a primary love interest and sexual partner. If that’s not for you, I recommend Pat Barker’s work.

A fair question, and I don’t know the answer, would be when did guys start referring to themselves as Achillean? Personally, I don’t really care. I think other people should describe their sex lives how they like. Hypothetically, even if the term were responsive to Miller’s fiction, I still don’t care.

And here’s where we get to what I really have to say. The Homeric tradition is oral— no one really “wrote” the Iliad in accordance with modern standards of intellectual property. We carry that tradition today. Here is the part where I disagree with you: Achilles is not just a character in a book written by Homer thousands of years ago. He is ours. Fluid and thriving, part of culture. If the myths of Achilles continue another millennium, carried by tumblr girlies and esoteric gay men, then great. It’s as it should be. It’s how fiction works.

#thank you#anonymus#the song of achilles#tsoa achilles#achillean#saphhic#greek mythology#homer#tagamemnon#the iliad#oral tradition#madeline miller

24 notes

·

View notes

Note

Brad and Bergy as Judas and Jesus 👀👀

Oh, so we're doing this?

Okay. Buckle up. I have Thoughts. I have Feelings. I Don’t Have a Brain to Mouth Filter.

So first of all, Brad Marchand did all the heavy lifting for me on this one. Him talking about Patrice Bergeron being ABOVE??? JESUS??? HELLO??? Their relationship. Their personalities. The “Saint Patrice” nickname. The dedication. The potential for ANGST

The way Marchand looks at him.

ALL THE TIME.

I didn’t make this up he did this to himself.

(note: I’ve seen other people talk about this as well. Linking this post by @hard4softthings because I like the way they phrased their response, but there’s other people who’ve been talking about this recently I just don’t remember any specific posts.)

Now. Here comes the Narrative:

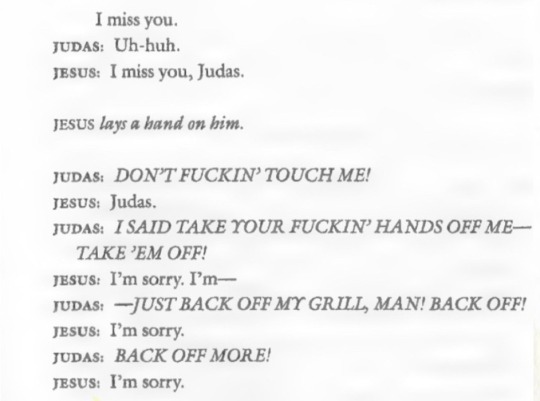

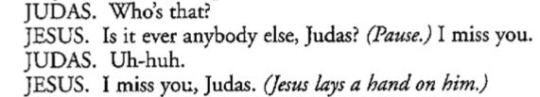

We’re all on Tumblr so we’ve probably all come across this line from Stephen Adly Guirgis´ The Last Days of Judas Iscariot (2005) that reads like a punch to the fucking gut:

Which is an INCREDIBLE line, but the play itself is actually .. um.. a very different vibe:

Tell me Judas doesn’t read a whole lot like Brad Marchand. I dare you.

The line that precedes this is also pretty Brad/Bergy.

Is it ever anybody else? No. It’s Patrice Bergeron and Brad Marchand and it’s BEEN the two of them together at the centre of all this for years. It’s Jesus and Judas, Bergeron and Marchand, their names go together.

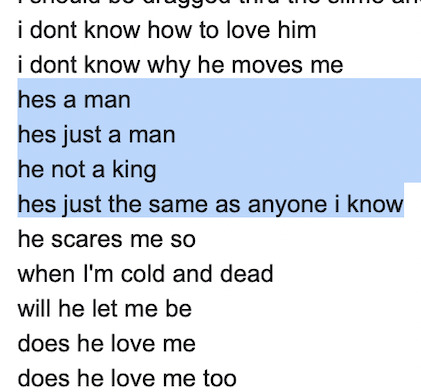

One of my personal favourite Judases is played by Carl Anderson in Jesus Christ Superstar (1973). He really embodies the Tragic Villain I believe Judas to be. In several of his lines/lyrics he talks about the myth/person dichotomy. He loves Jesus of Nazareth, but does not know how to feel about Jesus Christ the Son of God.

Link

Link (SERIOUS TRIGGER WARNING: SUICIDE)

Which becomes especially relevant if you think about Bergeron being Saint Patrice, and Marchand being The Rat.

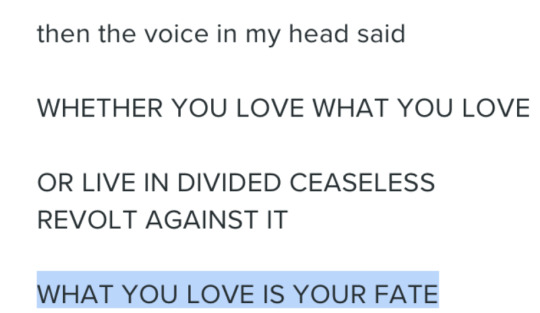

Borrowing from Frank Bidart’s “Guilty of Dust”:

Except we’re taking the Mythology approach to this: your name is your fate.

Now the real tragedy of Judas Iscariot is that his name is Judas Iscariot. We are all familiar with the bible story and as a result, the actor playing the part of Judas simply HAS TO betray Jesus. It’s what his entire identity is centred around. If he didn’t, the audience wouldn’t be able to recognise the character as Judas.

(Obligatory Richard Siken:

Snow and Dirty Rain)

That’s just tragic inevitability for you bay-bey.

In Jesus Christ Superstar, Judas’ name is repeated twice right after he betrays Jesus:

“Well done, Judas. Good old Judas” = Good job person who claims to be Judas, you have betrayed Jesus and proved yourself to be Judas. You are now “Good old Judas”, which is to say, the Judas we recognise from the Bible.

A lot of theatre productions play with this idea of inevitability & living up to ones name in interesting ways.

(See: Shakespeare’s Antony & Cleopatra & their repeated failure to live up to their own myths / Troilus & Cressida “This is and is not Cressid” (5.2.175) when Cressida lives up to her name by being unfaithful, which Troilus thinks is unlike the Cressida he knows personally / Iago’s “I am not what I am,” (Othello, 1.1.65) - I am Othello’s loyal friend except that I’m not, I am Iago & will betray Othello, except that I am not yet because I haven’t betrayed him yet & earned the name Iago)

In Terrence McNally´s play Corpus Christ there is a moment where Judas becomes Judas:

The actor stops shuddering, has now been Named Judas and will go on to fulfil the ROLE of Judas.

In the case of Marchand and Bergeron I am most interested in the ways in which their nicknames become their fate:

Brad the rat - This one’s relatively straight forward. Marchand accepts this role and really works hard to seep living up to it. He has received the Rat label and My God he will act like the rat you think he is.

Saint Patrice - a nickname Bergeron has said he does not particularly like or agree with, but which DOES affect his behaviour and our perception of him. If Bergeron was to take on the role of the rat, that would be weird and uncomfortable to us. We expect Patrice Bergeron to act “like himself”.

Which ties it back to Jesus Christ Superstar: “If you strip away the myth from the man / You will see where we all soon will be”. Carl Anderson’s (brilliant) Judas struggles with the fact that he loves Jesus the man, but not Jesus the myth. In the case of NHL stardom you can look at this in terms of the difference between their on-ice personalities vs. their off ice friendship. Brad loves Patrice The Man, Patrice His Friend, he is less concerned with Patrice The Myth.

I also cast Brad as Dionysus in my little hockey mythologies. There are a few obvious (and slightly silly) reasons for this: Dionysus being the god of the grape harvest (read: wine, drunken revelry), festivity, insanity, (religious ecstasy .. interpret that however you will.. ), but it is partly because Dionysus is the god of theatre.

(I will circle back around to Brad/Judas I promise)

Dionysus = Theatre = The Rat Persona As Performance

(Note: person/persona/personality, from πρόσωπον or perhaps persōna = mask)

Now this idea of the Persona (rat personality) as that which helps the audience recognise your role in the play (the name of the character you play and the expectations that come with said name) and mask as something used to obscure your actual face is really interesting!!

It comes back to this question of free will vs. predestination. How much of what Judas does is the Human Person, how much of it is his Name-Fate. How much of The Rat is Brad. How much is just him living up to his reputation/nickname.

Oscar Wilde has a fun little quote about this that’ll complicate it further:

“Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.”

(The internet informs me this is from The Happy Prince & Other Tales but I will admit I only know it from the end of a Criminal Minds episode)

Michael Kinnucan in my favourite essay ever written about anything ever The Gods Show Up writes:

Brad is the rat, the rat is brad. It’s a person. It’s an act. It’s a mask. We know it’s a mask, but how much of it is a mask. No idea. COMPELLING THOUGH.

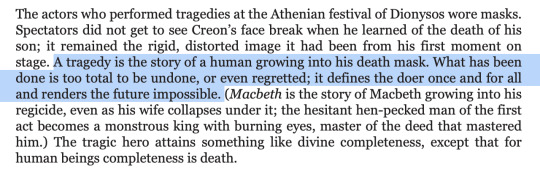

This same essay then brings us back to the tragedy of Judas:

Now this is where it gets niche.

(I´ll continue in a second post.)

#dont ask me!!! about narratives!!! unless you're prepared for me to be annoying!!! about narratives!!#brad marchand#patrice Bergeron#judas iscariot#long post#pt. 1

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is an Achilles x Patroclus short story I wrote in my AO3 book, inspired by "The Very Hungry Caterpillar"

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In the light of the moon, a dead soldier was brought back to the Greek camps.

One Sunday night, Achilles found out his boyfriend Patroclus was dead... and BAM, in the next second he became a very, very angry Achilles.

He started looking for revenge.

On Monday, he made one bloody carnage through the Trojan army. But he was still angry.

On Tuesday, he scared the shit out of two gods on the Trojan side. But he was still angry.

On Wednesday, he killed the Trojan prince Hector and dragged him around Troy three times. But he was still angry.

On Thursday, he wailed and mourned at Patroclus's body for four hours straight. But he was still angry.

On Friday, he destroyed five Trojan legions with his bare hands. But he was still angry.

On Saturday, he had killed one Iphition, one Demoleon, one Hippodamus, one Polydorus, one Dryops, one Demouchos, one Laogonus, one Dardanus, one Tros, one Mulius, one Echeclus, one Deucalion, one Rhigmus, one Areithous, one Lycaon, one Asteropaeus, one Thersilochus, one Mydon, one Astypylus, one Mnesus, one Thrasius, one Aenius, one Ophelestes, one Penthesilea, one Memnon and one Troilus.

That night he continued crying over Patroclus's body.

The next day was Sunday again. Achilles accepted King Priam's plea and returned his son's corpse, but after that, he didn't feel better.

Now he wasn't scary anymore - and he wasn't an angry Achilles anymore. He was a sad, depressed Achilles.

He continued his massacre through the battlefield, getting the blood of Trojans he decapitated all over himself.

He continued the massacre for more than two weeks.

Then he got shot by Paris, a deadly arrow pierced through his heart and...

He fell down to the ground with a beautiful smile.

#achilles#patroclus#patrochilles#achilles x patroclus#patroclus x achilles#the iliad#homer's iliad#short story#writing#inspired by The Very Hungry Caterpillar#my works

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

ill be honest. troilus is a very interesting characterization of whats supposed to be a protagonist? like for all hes worth hes very Passive and basically lets panderus do all the heavy work for him. hes too much of a coward to confess and get rejected so he manipulates cressida into having no other choice but to accept him - ie pretending someone is talking behind her back / threatening to kick her out of troy so he could comfort her, pretending to be sick so she will comfort him, etc etc...like....dude come on

#t+c#i just need to keep on reading bc i cannot possibly see how this gets turned on CRESSIDA being the bad one like man you fucking suck LOL#but now im wondering. cause the reason im getting sooo into this is cause i was going to do a short story retelling. wondering if i should#make it a bit longer now. probably not like a novel but it would make a nice novella ? ill have to see. i have a lot to be read b4 then lol

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

“ i’m not leaving you here . ” @ Achilles????

"It's not as if this is either permanent or actually deadly." Achilles scoffed, wondering in that moment if that was why the boy had so deliberately broken his spine and then stormed out of the arena instead of finishing him off.

Achilles didn't even come here often. Only did so when he was feeling particularly... dark-minded. Elysium was a gentle, generous existence, to be sure. As close a simulacrum to life as the Underworld could offer the souls of the dead, and it was certainly close enough.

He could tell, though. Could tell the difference, and though he'd 'gotten better' about it, sometimes the only thing that helped was the arena. It offered a thrilling suggestion of actual life in its momentary threat. He felt as close to mortal and alive in the arena whether he won or - rarely, extremely rarely - lost. He would never lose on purpose, but sometimes that brief moment of flickering consciousness was something he sought, the not-death that was the only thing that could be experienced here.

So he'd come here, today. What was the odds that Troilus would be the one across from him? This was only the third time in all the time they'd been inhabiting Elysium that he'd met the boy - in or out of the arena.

"The dead, after all, can't die." Annoyance edged his words, though they were not really meant for the mortal son of Hades where he stood over him. Wasn't even aimed at his disappeared opponent. He wasn't sure what the boy was doing here - was he simply not used to how the arena worked?

Of course, usually the defeated participant wasn't left lying on the ground with a broken spine that would only heal outside of the arena's bounds.

He could undoubtedly accept the implied offer to help him out, but Achilles would rather wait for Patroclus.

Who would scold him for not taking the aid offered, but it mattered little.

1 note

·

View note

Note

“Love can arguably make people unhappy just as much as it makes them happy … ”

It's an admission that she's never actually brought up before to anyone, and of all people--Tessa never expected to be saying as much to one of the men she oft read about in her well-worn romances. Well ... Tragic romances. Romeo & Juliet, Troilus & Cressida, Antony & Cleopatra--Those were the tales hidden away in that carefully cloaked shelf of hers. Love was beautiful and burned brightly, but that very same flame could burn a person alive.

"--My apologies, Sir Tristan. I am not saying it is a bad thing. I just ... "

Gripping her arm, the fabric of her blazer bunches up beneath her gloved fingers.

That same brand of love gave birth to the likes of me.

Fate Grand Order - Ooku Event Sentence Starters Part 2 -- Accepting! -- @ardensfides

The Child of Sadness knew this all too well. There was a part of him that nearly accepted the same sentiment as his Master spoke of, but he knows that it is not something they both can cast aside. No matter how many times they have been burned by it, soared to the highest layer of the atmosphere, only to be thrown down hard by it. Love is something that will always stick with the. He's tried it many times before. Past, present, and maybe he will in the future as he stays by her side.

"Do not apologize. I may be the best person to understand your point of view. However…"

He moves a gloved hand towards her, resting it upon her clutched fingers.

"You have nothing more to fear when it comes to love."

Was he speaking as a Servant, or as someone more than that? He promised to protect her, even though he also wished for her not to rely on him so much. Ah, how things have shifted over their time together. He can't promise much, but he can promise that she has no need to push it away.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Congratulations, LINA! You’ve been accepted for the role of TROILUS with an FC change to Henry Golding. Admin Rosey: I am absolutely HOWLING. So, when I was writing Troilus, I was having an amazing time -- he’s so nuanced and seemingly superficial, but there are so many detailed facets that contribute to his happy-go-lucky attitude. He’s so utterly disarming and charming that, from the interview alone, I couldn’t help but swoon over him. Your development for him promises so much, from the sought-after revelation of Celeste’s infidelity to turning him into a hollow and hungry creature. I’m absolutely over the moon to be putting my precious boy into your hands, Lina. By all means, ruin us all. Please read over the checklist and send in your blog within 24 hours.

WELCOME TO THE MOB.

Out of Character

Alias | Lina.

Age | 26

Preferred Pronouns | She/her

Activity Level | 5 – Med school honestly wipes the floor with me most days, so I can’t promise daily activity but as I’ve said before, I promise consistency and communication. I’ll request a hiatus if needed, and I won’t disappear or drop-out without warning.

Timezone | Finally back in EST (UTC-5:00)

Current/Past RP Accounts | —

In Character

Character | Tomas Sabello -> Could I request an FC switch to ether Henry Golding or Godfrey Gao? I love Bob Morley to pieces but I’ve used him as an FC for long enough that I really struggle to dissociate him from the role I played. I think Henry fits Tomas’ gentle disposition best, but Godfrey has more versatility in terms of acting roles/expression which seems more in line with the mood in Verona and what he may eventually become… I dunno! I’ll leave it to you guys to choose the preferred alternate FC in the event that I do get accepted. I’d be happy working with either one.

What drew you to this character? | I really liked how opposite he is to Viv, honestly. He’s so enamored with emotion, and despite the fact that he’s an actor by trade, he’s an open book when it comes to anything that inspires feeling within him. I think Tomas loves the idea of love to such an extreme that there’s no thought to guarding himself from it. No amount of pride could keep him from offering his heart up, not even the threat of rejection. He takes and he takes, but he also gives to the people around him, indiscriminately; even to the most insignificant of passersby who’ve touched his life or inspired his creativity in some brief, ephemeral way. While Viv absorbs and safeguards whatever light she finds, Tomas reflects it freely back into the universe, and I really like that dichotomy.

What is a future plot idea you have in mind for the character?

*∆* - Ignorance isn’t bliss, it’s oblivion: I’ll keep this point short and sweet; I want Tomas to find out about Celeste’s infidelity and for his heart to get absolutely shattered in the process. It could be sooner, later or whenever, but I think we’re all holding our breaths for that to happen in the story, and I’d love the opportunity to portray that.

*∆* - To fight one’s nature is a losing battle: This is a plot contingent on the arc of his relationship with Celeste and details pertaining to their marriage (how long it takes for him to find out she’s cheating on him, what they do with that information, if they divorce, etc.). But essentially, I’d like to show Tomas’ struggle with his own fidelity because in his bio, he strikes me as the sort of character that doesn’t settle on one lover easily. And he loves Celeste with every inch of his being and right now that’s what’s keeping him faithful, but I think that even if her infidelity isn’t revealed, eventually Tomas will start to feel the strain. He’ll notice the little signs along the way that hint that she doesn’t quite love him the way he loves her. I think those would put cracks in the marriage even if Isabella wasn’t in the picture. I’d like to explore those, and how little micro-tensions crop up in chronic relationships when one partner feels like they’re pulling all the weight. I want to dig into that and cast the lens on a quietly troubled relationship, and I want to see how far it pushes Tomas in response. Does he grow colder? Does he seek intimacy elsewhere? Does he fall into the same temptation and cheat on Celeste, whether physically or emotionally? Let’s find out!

*∆* - Any way the wind blows: I’ve always imagined Tomas to be the unsettled sort, in all senses of the word. His loves have always been transient and fleeting, his decisions (both in leaving Rome and marrying Celeste) seem rash and impulsive… I think capriciousness is a trait of his that extends to all facets of his life. So one headcanon I have for him is that now that he’s on sabbatical from acting, he’d want to try his hand at something new. Activities or careers that he gets excited by every few weeks and actively chases until something changes and then he drops the ball and moves on, certain he’ll find his luck elsewhere. I think it’d be interesting to see him get into all sorts of mix-ups while catering to this instinct, and maybe unintentionally making himself a nuisance to other characters in their line of work in the rp. Just this over-excited dude picking up positions and then dropping them as if life’s his own picnic… It’s definitely going to rub some people the wrong way and I’m here to see it happen!

*∆* - The hardest of hearts: … I’m intrigued by Tomas’ deep resentment of Roman Montague. His bio implies that it’s his acting experience which primes him to look at Romeo as if he’s also an actor, playing a part he doesn’t deserve. But I think it goes deeper than that. I think canonically, even, Tomas’ character seems to have a lot in common with Romeo from Shakespeare’s original, or at least, the earliest version of Romeo that we see. Lovelorn and lackadaisical, an innate predisposition for goodness, and yet undoubtedly leaving lovers a little carelessly in his pursuit of love, etc. So the way I see it, beyond his judgment of Roman as being unfit to rule, I think Tomas doesn’t like him bc he sees in Roman all of the same flaws he recognizes subconsciously in himself. It’s always easier to see our flaws through a mirror. I’m interested in seeing how far Tomas would go to spite Roman in order to avoid having to confront himself. The fact that Celeste is still tied to the Montagues would also be a continuous dilemma for Tomas, who dislikes both mobs. Depending on what plots come up, I might even entertain the thought of getting Tomas tied up in Capulet business, with the singular goal of bringing down Roman Montague.

*∆* - … Destroys itself in the end: In his bio, it’s alluded that Tomas took from both his parents when it came to his nature. He loved as frequently and as persistently as his mother, but destroyed those in his wake as surely as his father; leaving his path littered with broken hearts. I want to see that side of Tomas again. Except this time, instead of it being an accident of youth and of too much ignorance, I want it to be intentional. I feel like heart-break would leave him hollow and hungry, and I want to experience that side of him. I think his capacity for hurt is almost equally potent to his capacity for love, and that’s what makes him such a compelling character in my eyes.

Are you comfortable with killing off your character? | Through a well-developed plot, yes.

In Depth

These interview chairs are always so stiff that Tomas has to wonder whether it’s intentional. Maybe it’s to keep him from falling asleep, but he’d never do that. He likes giving interviews for the most part. Of course, it was easier in his early twenties; when he had very little in the ways of a filter but was blessed with the circumstances in life that permitted him to get away with it. Oh, and an adoring audience. That always helped of course. These days, as a married man in a new city, he has to be more careful with his tongue.

That doesn’t make him any more careful with his smiles, however. And right now he’s aiming one of his most brilliant at the interviewer who’s already started asking him questions. They’re three minutes in, but she hasn’t returned any of his good cheer so far, and that’s uncommon. He’s remembered all his pleasantries, he’s been considerate enough in opening doors and waiting to be seated - but still, nary a smile. He doesn’t mind too much, but it makes his job so much more enjoyable when they do. And as a result, Isabella Gagliano is both a damper and a challenge. But before Tomas can engage her into lowering her defenses, she’s presented him with the next in a series of fan-chosen questions.

“What is your favorite place in Verona?”

”The Two Gentlemen. Certainly the best bottle of pinot grigio that I’ve ever had.” Tomas tells her, lips pressing together as sweetly as the juice from those sticky wine grapes. “You wouldn’t be remiss either if you tried the risotto al tastasal. That’s a real recommendation, you know?” He stage-whispers with a grin, “Off-the record.” But if Isabella takes note, he can’t tell.

The truth is, it’s a lie. A white lie, he consoles himself, because sometimes, the truth is too heavy a price to pay. The truth is that his favourite place in all of Verona is the recently abandoned Multisala Rivoli. It’s a cliche, he knows, an actor finding his second-home inside of a rundown movie-theatre. But it isn’t for the movies that he goes, nor out of any misplaced vainglory. Rather, it’s the promise of nondescript privacy that draws him like a bee to to honey. There, he can meet his new friends beyond the prying eyes of the media. There, he has a clandestine spot to escape the humdrum of the city for a few hours, alone with his thoughts. But it’s not a truth he’s ready to share, and moreover, the Montagues will like this answer better. It’s a nod to their territory; a little more promotion for their best-boasted restaurant. He refuses to join them, he refuses to share in their cause, but maybe sliding in such harmless tips will convince them to lay off of Celeste’s case and stop pressuring her to pressure him to join. Truth and politics don’t mix. Every time a video begins recording, Tomas is well aware of that. But above all, an actor must always remember his part.

“What does your typical day look like?”

“What, like a twenty-four hour play-by-play?” He asks playfully. “No one’s that interesting,signorina, I promise. I remember I was asked a similar question in an interview two or three years ago. I think it was for Sorrisi e Canzoni? Or maybe GQ…. Either way, it was a much more exciting answer back then. Plays, parties, private jets… ” Tomas reminisces fondly, but not fond enough to want to trade it in for his present. “I hate to disappoint, but it’s not the same anymore. I’m a married man on sabbatical now, remember??” He says, directing the question towards the camera before letting his gaze find Isabella once more. His life is quieter now, but happier too. “Not that it’s boring by any stretch. I’d recommend marriage, actually. I know it’s done wonders for me! But if I start talking about her and all the ways she’s changed my routine everyone will be rolling their eyes and complaining about cavities before this interview’s over.” Tomas chuckles, thinking of the myriad of ways his daily life has become synonymous with Celeste. What time she wakes, what time she leaves, when she comes home or when he gets to persuade her out of the house on little dates… He has a life outside of Celeste to be sure, but it’s only around her that he’s really reminded of what he’s working towards. Like Eros and Psyche, he thinks. He loves, but she sets fire to his love and gives it true sustenance. A future, a family, a very happy ending - That’s all he wants these days.

“What has been your biggest mistake thus far?”

He laughs at that, taken aback by the girl’s directness. “Is that really what it says on your sheet??” He cocks a brow, leaning forward as if to sneak a peek. “Damn… That’s harsh.” Sometimes, his fans seem like tiny mosquitoes; hungry for every teeny-tiny drop of his blood as they submit questions as invasive as these. “I have to think about that one…” Tomas admits with a bemused shake of his head. “I try not to think of my experiences as mistakes. Even the ones that might feel like it initially. Everything happens for a reason, doesn’t it? Don’t you believe that?” He looks to his interviewer as though hoping to coax another answer out of her, but she doesn’t indulge him. He’s always preferred dialogue to monologue, despite his choice of career. It takes an exchange of ideas to see the world through new lenses, and he can’t do that while talking continuously about himself. But another pensive, stolen glance at Isabella tells him that she probably won’t care what his answer is, so long as he gives one. He could make it up right here on the spot - something like ‘I’ve started a third gang in Verona to spite the Mobs‘ or ‘I kicked a dog once’, and she probably wouldn’t bat an eyelash. He wonders why. He wonders why she’s so determinedly expressionless.

“Do you play Poker?” Tomas asks without warning. He hadn’t meant for that to come out of his mouth but somehow it does and it takes another laugh and a wave of his hand to dismiss it. “Sorry. But you could! It’s impressive actually - in a good way. To answer your question, I think I’ll have to keep this one to myself.” It’s apologetic but firm, because his biggest mistake is failing his parents. Of all the roles he’s played thus far, that of ‘son’ has always left him most wanting. He couldn’t fix their marriage. He couldn’t inspire their divorce… To this day, his adulterous mother and destructive, ill-tempered father remain tethered to each other. Two rusting anchors, weighing themselves down to the bottom of the sea-bed… Most days, Tomas tries hard not to think about it. But there are some moments, moments when he’s feeling low, that he wonders if he’s responsible for their unhappiness; wonders if he couldn’t have done more to help them find happiness, along the way. Today is one of the predetermined no-thinkdays though. The days he’s giving interviews always are. “Sorry about that… Got anything else on your nifty list?” He prompts her, hoping to move on to a happier topic.

“What has been the most difficult task asked of you?”

This question too, gives him pause. More than he’d like. There’s the shadow of fleeting suspicion as he steals a glance at Isabella, wondering if they’re posing these questions on purpose to throw him off. But what cause would a reporter have to do that? You’re being silly,he chides himself, mulling over the question. Again, he knows the real answer.

Commitment.

It isn’t easy to choose a single person in this life, Tomas thinks. To narrow his expansive romantic inclinations and promise them to one individual and one individual only. But it’s a choice he reminds himself of every morning when he wakes up, when he cracks an eye open only for his gaze to fall on the familiar comfort of Celeste’s blazing red hair, like a halo around her cherubic face. It’s a choice he must remember when he’s comparing paintings with Juliana and hears the clear-bell tone of her laughter echo in the museum. A choice he must remember when his fingers find the soft, unwritten skin beneath Santino’s wrist as they look for stars in a midnight sky. A choice he recalls even as he listens to Paola recount the tales he’s missed in her life; eyes dancing with ferocious passion and he thinks what if, what if…

… But it’s a struggle he dares not reveal. It would insult his beloved wife, it would make a mockery of the vows they took in front of that altar, all those months ago. Worse still, it would surely garner derision from the audience, especially from his most die-hard fans; some of who still count on the failure of his marriage in order to regain the bachelor fantasy they’d attached to their idol. But idols were effigies of gold and silver. He was not an idol, he was a man of flesh and blood and feeling. Do you understand?… You will never understand me like she has, he wants to rebuke them. But there’s an old fondness that he can’t help when it comes to those who loved him first. And so his countenance softens as he answers the reporter’s question. “The most difficult task for me, has been leaving behind all my loved ones in Rome. My friends, my family, my fans…” He presses his fingertips to his lips for a moment before waving them towards the camera, sending the kiss to those who’ll hope for it most, when the interview airs tomorrow night. “I send my love, and I’m humbled by your continued support.”

“What are your thoughts on the war between the Capulets and the Montagues?”

“It’s-… It’s insanity.“

Now the Montagues won’t like that. But he feels the answer so strongly, and with so much conviction that he thinks the glassy brightness in his eyes would betray him anyway. Some lies are too big to swallow, even for an actor. “Brutal and unnecessary - do they even remember what they’re fighting for?” He asks Isabella, though he thinks she’s probably no closer to answering that than the other Veronesi. “You know, the stories say that it’s been so many decades now that no one knows any more… Isn’t that silly? To fight over something that you can’t even remember?” But deep down, Tomas knows it’s not that simple. Because mobs don’t need an impetus; not when there’s so much profit to be made in criminality. All the rest is just stories, to play on the sympathies of a winsome public. He should know… He played on that same, guileless sympathy, night after night after night on a front-lit stage. But art is one thing, war is another. And Celeste is tied up in this war, much as he hates to think about it.

“Maybe I’ll go back to Rome one of these days,” Tomas announces abruptly, shifting upright in his chair. There’s an ardent gleam in his eyes because he likes thinking in maybes. They’re so much more satisfying than the limitations of what is or isn’t strictly possible. “I’d like to take my wife with me. She’s never been… Can you believe it?? Never been to Rome… We could start there, then maybe a tour of Europe. Maybe a second honeymoon. I’m sure she’d like that.” He doesn’t know if that’s true, he doesn’t know if he can ever return to Rome, but it has a romantic ring to it nonetheless. And when has Troilus ever been able to deny the sweet-nothing whispers of romance, even as a city tears itself apart around him?….

Never, he thinks… Not even then.

——————————————-

(Thank you for Reading!!)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Little Troy

Word Count: 577

TW: Death mention, sex mention (neither are on page, simply very vague mentions)

A drabble in which Apollo remembers his son Troilus. Troilus‘ mother was Hecuba, queen of Troy and Hector’s mother. There was a prophecy that if Troilus grew to be 20, Troy would never fall, so Achilles nabbed young Troilus (10 in my version) and proceeded to kill and mutilate him in Apollo’s temple.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I was not present for Troilus’ birth.

It was not out of hatred for the boy, for my boy, but out of fear. Fear that I would taint him, hurt him. That his association with me would lead to disaster. Had I known then that he was destined to die either way, I would have been a real father to him. But instead I let Priam and Hector take that place, both far better men than I.

I am still unsure what compelled me to lay with the queen of Troy in the first place. Perhaps I thought that if I slept with Hecuba, I could be part of this family. A moment of weakness on my part. Had I forgotten what I had done, and what they were destined to endure? Did I not remember that I was Apollonas, the destroyer? I had slipped, dreaming that maybe they would accept me as their own, not as their patron but something else, something closer and more meaningful. Something I wasn’t meant for. But even if I could not have these things, I would not deprive my son of them. He deserved to grow up with his mother, his siblings, his family, in the city most beloved to me that gave him his name. Little Troy.

And so I stepped away, knowing my love was a punishment. I watched him remain safe behind the walls I had built with my own two hands, laboring for hours against the blistering heat of the sun with not a single of Father’s clouds to shield me. I saw how beloved he was to all who lay eyes on him; Hecuba who would fuss over him with an endearment none of her other children had felt in years, Polyxena running after him throughout the palace, Hector taking him to ride the horses they both so adored. Very rarely did I dare to approach my son, to speak to him and give him small gifts. I thought he’d despise me, and I wouldn’t blame him for it in the slightest if he had. But though he was small, his heart was vast as the heavens, and he only ever met my guarded gaze with wide smiles and eyes that sparkled like twin stars. I wasn’t deserving of such love, and yet he gave it freely, an endless fountain of joy.

I hadn’t seen him the day of his birth, but I saw my son the day of his death. He had sat behind Polyxena on a horse, his cheeks flushed pink from laughter and his arms wrapped tight around her middle. It seemed mere moments before when he had first perched in the saddle, having to be lifted on and clinging to the seat precariously, but now he hopped on with ease. He’d be a great horseman, just as Hector was, and one day a great warrior too. He would surpass his brothers, his step-father, perhaps even me, if only he had more time left.

I shouldn’t have taken my eyes off of him that day. I should’ve kept watching, kept following him. I should’ve been there. But I wasn’t. I had turned away. I had left him. And by the time I heard him screaming from within my temple, clinging to my statue as he pleaded for his father to save him, it was too late. All I had left were his scattered remains and regret that would haunt me for millennia.

#apollo#apollon#apollo deity#the iliad#homer's iliad#tagammemnon#greek mythology#greek myth#greek gods#hector of troy#troilus#trojan war#classic literature#classics

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prophesy

For @drarrymicrofic prompt, better than fighting. This is a 1.4k "microfic" lmao. You can read on AO3 as well as here.

You know when you look at someone and just know they're no good? Pansy says it's a sure sign that they pissed you off in a past life. I tell her that's about the funniest shite I've ever heard. I don't need divinity to explain myself; I've always been good at reading people. That's just how I am.

Say, Pansy. I knew we'd hit it off the moment I saw her head-to-toe in Prada, her hair as glossy as volcanic glass. That's not fate: that's good taste. And Crabbe, well — that one is a bit odd, I'll give you that. Lord knows why I have a soft spot for him when he's far too much trouble for his worth. Nearly got me killed once or twice, even. Not literally, of course — just at the bars, when he drinks me under the table. Pansy says he's "mine" the same way Theo is "hers"; I've never cared for Theo. He seems the type of guy who holds back while you make a rash of bad decisions. Mind you, Pansy isn't much better either, but at least she's always right there, too, making the same damn mistakes.

Pansy asked me what Theo did to piss me off so much. I made up some lie about how he didn't warn me about a rotted foundation on a house I was trying to sell, but really, I don't know why I think that about Theo. I'm a genius people-reader, alright? And I don't question intuition.

So I'm not worried when Blaise calls me in to meet a high-profile client. Rich geezers, they're all the same. And I've seen this one plenty in the newsstands before, so I've already sussed him out. He always looks like he doesn't want to be there. A bit sullen — dead inside — but harmless enough.

"Seems a trifle odd, doesn't it?" I tell Pansy that morning. "He could've called me direct. My number's on half the park benches around his neighbourhood."

"Maybe he thinks you'll say no," Pansy says. She has that faraway look in her eyes she gets every morning before the caffeine kicks in.

"Why would I say no?" I laugh. "I'd be an idiot to give up a million-pound commission."

She's not paying attention to me. Her eyes bug out and her lips part. It's like she's in a bloody trance. I swear she does it just to piss me off.

I'm still thinking about her ugly mug when I'm going up to Blaise's office. He's got the entire penthouse of the building for him to sign papers, and the elevator ride up the twenty-three floors leaves plenty of time for spacing out. So I'm caught off guard when, coming out of the elevator, Harry Potter smacks straight into me and all I want to do is kill him.

Oh lord, how I want to kill him. My rage builds so strong that I'm taken out of my body. Where I go, I don't know. But when I come to, Potter is gone and I'm sitting across from Blaise.

Blaise has his pitying face on, the one he practices in the mirror. His hands are clasped over the expansive walnut desk (live edge, of course), his suit as green as Potter's eyes.

Potter's eyes. Merlin, I barely remember meeting the man, but it's all I can think of now. That luxurious, deep emerald. Green as everything I ever wanted.

"No," I say. "I won't take him on."

"Dee," Blaise says, gentle. His brows raise.

I'm on the spin bike at the gym trying to blow off some steam when Pansy calls and says, "Blaise is right, you know," her voice tinny above the whirl of bikes around me. "You'll be stupid to walk away from a million pounds over a premonition."

"He's a lying tramp, I swear. I'll put in all this work, set up the listing, stage the place, and then he'll change his mind and walk right out. I know. He's a ticking time bomb."

"So...." she giggles, "what'd you think he did?"

I'm confused for a second, but then I realise she's probably talking about her reincarnation theory again.

"Don't you dare start on this past life shite," I warn. "I'm not in the damn mood."

"Maybe he razed your lands. Ohhh, can you imagine, Harry Potter — a viking? All that fur… mm, and those horned helmets. Sure makes me horny —"

"Jesus, woman. I'm at the gym."

"Okay, okay," she says. "Since you're at the gym, what about this: Harry Potter as naughty, lying George Wickham. And you: the poor Lydia Bennet, tricked into a life of poverty and ridicule for the rest of your days. Embittered, you —"

"That's Jane Austen, that's not even real life," I say before hanging up.

I meet Potter at his Islington townhouse the following Tuesday. He's a capital C celebrity so he's got no regular day job, which makes him horrifying easy to slot into my schedule.

"You're late," I say as soon as he opens the front door. He runs a hand through his tangled hair — soft, I know — and bleats out an apology as I brush past him into the grim, old place. The hallway is long and dark. There's a kitchen in the far west corner overlooking the garden. And upstairs there are three bedrooms, of which the medium-sized one is his because it faces east, and he enjoys waking sun-rumpled and satisfied.

The floorplan, I pulled from public records. The rest, I — well, I don't know. I just know. I know it with such vivaciousness that I can see us there, on his — no, our — bed, his arm thrown across my chest, and I —

"Draco?" he asks, tentative. Like he's found something he's lost but isn't sure what to do with it, yet.

My hands clam up, my heart racing back to the present. He's only a foot from me, his doe eyes searching. I know what it feels like to pull him in by the waist, to watch those lids flutter shut as we kiss. And I know he knows this too, so I lean in and punch his face.

"He called me Draco," I say to Pansy later. "Draco. Only my mother calls me Draco, and she's been dead a full decade."

"You're crazy, Dee," Pansy says, patting my hand with hers on the bar counter. "What did you do after? Get on your knees to kiss his arse so he'd keep you on?"

"Bloody hell, no. I bolted the fuck out of there thinking I lost the biggest deal of my life. But then the next day, Blaise calls and says Potter stopped by the office. Says could I get him a list of stagers, all cool and shite like nothing had happened!"

"Hm… maybe you two are more Troilus and Cressida than Brutus and Caesar. Ohh, or Achilles and Patroclus. God, yes. That fits so well —"

"Good God, woman! Unless Patroclus was trying to sell Achilles' ionic column abode, I don't want to hear another peep of past lives from you."

Pansy pushes her martini to me and waits for me to drain it before signalling for another round. "I'm only saying," she says, tapping her square-tip nails on the stem of the glass, "Kissing. Fucking, even. Wouldn't that be better than fighting?"

Naturally, I choke on my drink.

I meet with Potter the next day and manage to get through the walkthrough without any further hallucinations or fisticuffs. I call Greg up to stage the place and we go through the house again the following week. Potter's in the kitchen when Greg leaves and offers me a cup of tea while I wait for my car. I'm out of excuses and exhausted from the day, so I accept.

"Draco," he says when he hands the cup to me. Two sugars, a splash of milk. I try not to think about how he knows.

"Why do you call me that?" I ask instead, blustering.

"Why do you call me Potter?" he retorts. He's smiling, but I can tell he's not really happy. It's the same smile the paparazzi catches him with.

"I don't know," I say because I don't. My tongue knows his name better than I do.

I can't keep my eyes off of his as he comes up to me. "Draco," he says my name like he had a claim to it, long ago. I let him loosen the cup from my hand and push me up onto the counter. The angle's better here; perfect if I want to slide my hand up to his cheek and through his hair. He smells like broomstick and phoenix ash. I love him, I know. But it's not supposed to be this easy.

#blame tsoa for most of this#drarrymicrofic#drarry microfic#drarry#drarry fic#drarry squad#fwoosh writes

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reading a book about Hittite society, and while I haven't gotten too far, it started out with things relating to the royal family/ruling the kingdom, which is useful for Trojan family related things. So:

Presuming vassal kingdoms work similar (just on a lesser plane so to speak) to the Hittite core kingdom, then Priam being married to several women is perfectly apt, and he can have two wives, one more important than the other (both sons of these women would be of the "first rank", all equally legible for being heirs to the throne).

Hecuba would of course be the one of highest rank, and given that Laothoe is a princess (out of the few other names we do know for wives/concubines) saying she's the other major wife but still of lesser rank works as well as anything else.

Both Medesicaste and Kebriones are called illegitimate/bastards, but I'd say we can just assume that means they're offspring of one of the "actual" concubines (who weren't necessarily free women, as the two of the first rank would be), whose children might have status as princes and princesses but can't be used for heirs.

Having fifty sons would be extremely useful! The Hittite king appointed his sons to a wide range of positions, and sometimes it was even necessary/only acceptable that they be sons of the king, so Priam having a score and more to spare would just give him lots of maneuverability ruling- and administration-wise.

While a son of the first rank would be the only one allowed on the throne, that doesn't necessarily mean it be the oldest son (being a favourite would/might be weightier). Hektor as both oldest and a/the favourite of his father has a very solid grip on the position as crown prince. (I would say, given this, that if Troilus was still alive when Hektor died, HE'd become the crown prince.)

I only ever considered the position of Gal Mesedi (captain of the king's bodyguard basically, one of the commander in chiefs next to the crown prince and someone who would usually be a brother to the king) when it came to Tros' sons, but I feel like putting Deiphobos in that position is fitting? (Given the way Hektor talks of him when Athena impersonates him, he'd definitely fit/undoubtedly be given that position when Hektor ascends the throne if he didn't before that.) Before Mestor died, he probably had it, the way Priam singles him out as one of the (dead) favourites/best at fighting.

Administration-wise, the best use of Paris, and one of the positions he would be eligible for, would be as an ambassador (yes, even with how the visit to Sparta goes, but that's an outlier and special circumstances). It would undoubtedly fit him (and he has made at least one guest-friendship/ambassador trip as per the Iliad, to the "Paphlagonians" = most probably the Kaskians, who were actually a real big trouble to the Hittite heartland in earlier years and fierce warriors, funnily enough).

(If you want to know something amusing/that fits with the myth of how the royal princes of Troy are often shepherds or cowherds, the royal princes, even the crown prince, would have a "regular" job for a bit - one of the kings was a stablehand!)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…Many readings of Troilus and Criseyde suggest that Criseyde occupies a masculine space in the narrative that is vacated by Troilus through his courtly love behavior – certainly in the first three books of the poem, and perhaps the fourth as well, since there, Troilus is rendered passive in the parliament, in the bedroom, and in his inability to affect any change of circumstance, or even to change Criseyde’s mind. Perhaps more useful, however, is recognizing Criseyde as offering up an alternative, female masculinity. Speaking of the Wife of Bath, Karma lochrie implies that Chaucer challenges ideas of masculinity, noting “by placing masculinity, with its ties to authority, commerce, violent mastery, social mobility, and publicity, ‘up for grabs,’ the Wife performs an alternative masculinity.”

Given that Criseyde is already, to misquote Chaucer’s Franklin’s Tale, “lord in love” (5.793), the possibilities for her offering up an alternative masculinity that extends beyond the boundaries of the romance plot into the epic and thus bring her into what lochrie calls the “world of marital rivalry, textual contestation, and sexual struggle” come to the fore. Criseyde’s authority in romance is unsurprising: the lady is conventionally constructed as the locus of power against the vulnerability created by the male lover’s desire. For all her seeming anxiety about the love affair, Criseyde appears to be the far more experienced, active lover, another function of her widowhood. If Troilus’s inactivity prevents him from showing a “mannes herte,” Criseyde’s composure suggests that she possesses one.

The overarching narrative conventions of romance render her masculine in these first books, provided readers proceed from the shreds of definitions of masculinity that Chaucer offers up. However, once the war reasserts itself within the narrative, and epic takes over from romance, the reading of Criseyde as “tendre-herted, slydynge of corage” (5.825) tends to dominate readers’ understanding and thus becomes the source for both condemnation and sympathy. The image of her “with women fewe, among the Grekis stronge” (5.688), with all its implicit threat, becomes a symbol of a reclaimed feminine isolation and vulnerability.

This reading ultimately negates Criseyde, rendering her formless and passive, which the poem quietly but steadily refuses to do. Understanding Criseyde as entirely vulnerable and useless, unable to escape her father and prey to the dangerous advances of powerful men, is to make her, in Mary Behrman’s words, “much less interesting. Stripped of any motives of her own, Criseyde becomes a mere automaton, and the readers’ interests switch to the men who manipulate her.” Criseyde is either “the tale’s victim or its villain.” She can be read as a simple traitor to love, who should have chosen death over dishonor (or Diomede) when circumstances refused to allow her to return to Troy, but while many readers have done so, the poem suggests a more complex course: it reveals her as condemned not because she is “slydynge of corage,” but because she acts in self-protection, choosing the most powerful figure around as her protector in Greece as she had in Troy, denying certain elements of her own desires to do so.

Thus, Criseyde’s failure in Troilus and Criseyde comes not from her rejection of her position as the masculinized lady created by the romance genre, but in her at least partially successful attempt to preserve it, even within the epic narrative of war. Halberstam’s definition of masculinity is essentially epic, noting that it seems to “extend outward to patriarchy and inward into the family”; that it “represents the power of inheritance, the consequences of the traffic in women, and the promise of social privilege”; that it inevitably “conjures up notions of power and legitimacy and privilege”; and that it “refers to the power of the state,” she could be describing the gendered dynamics of Troilus and Criseyde. By maintaining her active, self-determining position within the war, instead of accepting the feminine vulnerability that brought about her trade in the first place, Criseyde attempts to save herself, if not her reputation.

Throughout the poem, Criseyde’s portrayal creates a tension between passive construction and self-determined action; she is pulled between the roles that the text’s genres create for her and the contradictory actions the poet allows her to take, which, to increase confusion, are often a product of the very roles they seem to countermand. Part of the difficulty arises from the ways that Criseyde is defined by the passive femininity conveyed by her status as solitary widow and romance lady. Indeed, Gretchen Mieszkowski views her as “substanceless, ... a lack” in her position of the “lady of courtly love” and adds that “she responds to others; she does not act herself. She stands for no independent values. She is Western woman: supportiveness without content, and absence of being, the Other, sheer responsiveness, no one at all.” Chaucer certainly opens up the possibility of reading Criseyde as passive femininity through the emphasis on her solitude, although this, too, is ultimately ambiguous.

Her fear, which by Book 5 comes to be an essential texture of her portrait, makes her vulnerable, while her role as desired object also renders her passive and observed, tied to the conventions of love. Yet ironically, her fear causes her to act as much in Book 5 as in Book 1, and it is her position as romance heroine that provides her with a kind of subjectivity and authority in the love relationship that does not completely vanish at the point of consummation but continues to inform her actions – and Troilus’s expectations – in Book 4. Even her widowhood is an ambiguous symbol of passivity and activity. Widowhood is a kind of solitude, as we see in Chaucer’s repeated use of the word “alone” to describe Criseyde, but it also provides an opportunity for women to be free of male control, a status she later calls to the reader’s attention.

…This picture is further complicated by the reintroduction of her anxiety; she is “Wel neigh out of hir wit for sorwe and fere” (1.108). Yet this very fear, which would seem to render her inert, does the opposite; taking control of her situation, she allies herself with the most powerful, most masculine figure the poem offers, Hector, the prince of Troy. Always a warrior, never a lover (his wife, Andromache, never enters the text), Hector occupies one of the few uncom-promised spaces. Edward Condren sees Criseyde’s plea here as an attempt at seduction; in abandoning “her passivity to lay her helplessness before Hector,” she aims to cast him as her lover.

Although this argument is somewhat unconvincing, Condren’s analysis remains suggestive: if Criseyde is indeed making this ploy, she is casting herself in the male role. After all, Blamires reminds us, “that, since men ‘do’ the deed in sex and pursue women, then women are recipients not agents where sexual activity is concerned.” Readers of Chaucer are aware from the Book of the duchess that the male lover casts himself at the lady’s feet crying “Merci”; of course, Troilus and Criseyde offers this formula as well. So in her mixture of passivity and activity – Condren agrees that “this sequence ... remains the only act planned and executed by Criseyde herself”– she mirrors two male activities.

Of the two, however, her active choice to connect herself to Hector bears greater implications for understanding Criseyde’s masculinity in the poem. Berhman points out that Criseyde “admires men of action, men like heroic Hector who value their individuality and refuse to let challenges daunt them.”Her vision of Troilus as war hero causes her to fall in love with him, not any admiration for the passive lover who writes the letter and whom Pandarus represents. The Troilus she sees is “a knyghtly sighte” (2.628). To look on him is “to loke on Mars, that god is of bataille” (2.630); he is further described as “so like a man of armes and a knight / He was to seen, fulfilled of heigh prowesse” (2.631–32). Troilus here appears at his most Hector-like, which the people’s cry, “‘Here cometh oure joye / And, next his brother, holder up of Troye!’” (2.643–44), firmly cements in Criseyde’s mind.

…That she ends up loving Troilus does not negate her acknowledgment of her own active will in her choice; she is not simply the objectified lady of romance. Even when the romance constitutes her as passive and desired, the immobile object of her dream of the eagle in Book 2, Criseyde “certainly does not view herself as a passive person” on whom meaning is imposed. Again, the reader is confronted with a tension between Criseyde’s fear and her self-determining force. At this moment, her understanding of her widowhood as a complex position is also revealed. The role of modest widow suggests a kind of isolation, if only a social one that allows singing and reading with her ladies, and Criseyde’s dark clothing “evokes both the idea of Criseyde’s vulnerability and the visual sign of her personal loss” and testifies “to the reality of human mortality and mutability,” while emphasizing her “state of being alone and vulnerable.”

It also suggests a possible availability: “the role [of modest widow] is not compatible with a sexual relationship, but it is compatible with the platonic segment of the lady-role, which Pandarus bullies Criseyde into accepting.” Yet in her widowhood, Criseyde sees her own freedom: “I am myn owene womman, wel at ese,/I thank it God – as after myn estat,/Right yong, and stonde unteyd in lusty leese, Withouten jalousie or swich debat./Shal noon housbonde seyn to me ‘Chek mat!’ For either they ben ful of jalousie,/Or maisterfull, or loven novelrie.” (2.750–56) Her recognition that widowhood provides self determination because it frees women from the hierarchies of the sexual economy causes Criseyde to ask “‘Sholde I now love, and put in jupartie / My sikernesse, and thrallen libertee?’” (2.773–74), noting that in love, “‘we wrecched women nothing konne’” (2.781).

In contrast to the earlier presentation of widowhood as fearful solitude, here it becomes an active, powerful position that allows for self-determination and self- construction. Criseyde’s chess metaphor reveals her masculine agency again: while “Criseyde’s allusion to chess also reveals that she thinks of herself in martial terms,” allying herself with the powerfully masculine figures of Hector and Troilus in their warrior guise that has just been presented to her, it also shows the potential for the female to take on masculine traits of mobility, power, and central importance. Or, as Jenny Adams comments, “a reader/player, who sees himself or herself as a piece on the board, must take responsibility for his or her own ethical conduct”; therefore, the player becomes responsible for her own actions rather than perceiving herself as acted upon.

In chess, the queen is the most versatile piece, able to move in all directions and any number of squares, while the king is limited to a single square’s movement, and his capture loses the game. Indeed, the king is a quite feminized figure in chess; he runs and hides behind the castle, and if he must start moving around, the player is in trouble. If widowhood allows Criseyde to assume the metaphoric position of a chess queen, it also allows her to win within a metaphor equally suited to love and to war, the two worlds of Chaucer’s poem. In the romance world, Criseyde claims the power available to romance heroines. This power may ultimately be a conventional fiction providing no real autonomy, but it remains inscribed in the story as a given. Criseyde is aware of and seems to enjoy some of these elements of power while understanding the difference between them and the more “real” autonomy of her widowhood.

Criseyde adds to the powers of romance a self-determining factor. The contrast between the two lovers’ decisions are striking; “while Troilus performs his unconditional surrender in a soliloquy, Criseyde negotiates a contract in front of a witness, fixing the rights and duties of both parties.” Blamires calls this a radical disruption of the “passive/active assumption in the scenes of courtship of Criseyde,” and in so doing alerts readers to the shifting nature of gender within the love narrative. In establishing the terms under which she will agree to love Troilus – that her honor and reputation will be protected – Criseyde again defines the terms of her consent – and does so publicly, thus in the masculine realm. That these guarantees ultimately fail does not detract from Criseyde’s self-determination, but from its ability to function within the assumptions of the genres of the narrative. The irony of her desires – the protection of her honor and reputation – given the ending of the poem only serves to create greater tension between the roles Criseyde attempts to play and the boundaries the worlds of Troy and the Greek camp (as well as the boundaries of epic and romance) impose.”

- Angela Jane Weisl, “A Mannes Game”: Criseyde’s Masculinity in Troilus and Criseyde

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

A dark, mocking hoodlum

a little provocation from the old play...

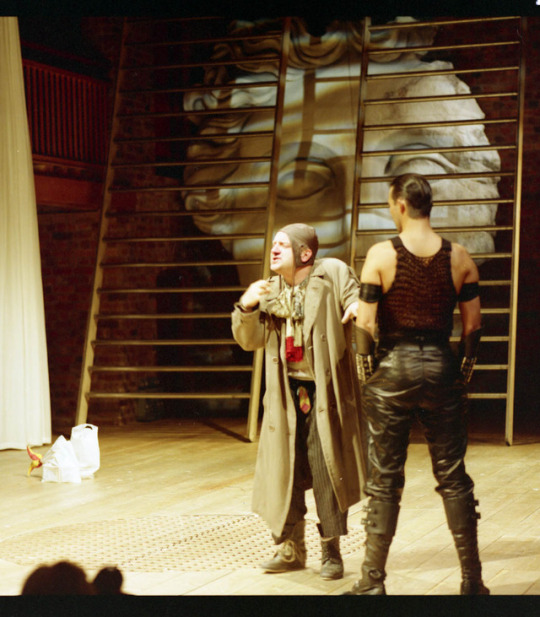

Troilus and Cressida by William Shakespeare

Directed by Sam Mendes

Theatre: Royal Shakespeare Company (1991)

In 1990, in the Swan theatre, Sam Mendes’ production of Troilus and Cressida was very well received, and particular praise was given to Ciaran Hinds’ performance as ‘a balefully magnificent Achilles’ (Wardle, 1990), ‘a dark, mocking hoodlum in leather, who might be on loan from a Los Angeles street gang’ (Nightingale, 1990).

Reviewers stressed the chilling, sinister nature of the portrayal of the character by Hinds: R. V. Holdsworth (1990) called him a ‘contemptuous psychopath’ and several other reviewers referred in passing to Patroclus as his ‘lover’ or his ‘boyfriend’ (for example: Taylor, 1990; de Jongh, 1990).

The relationship between the two men was clearly depicted as homosexual, including the use of contemporary visual references such as black leather, but by 1990 there was no gasp of shock. It was no longer modesty or distaste which relegated the nature of the men’s relationship to a subclause in a review. It had become an accepted convention of the play in production.

The review in the Guardian, by Nicholas de Jongh, was particularly interesting, since it compared the 1990 Achilles with the 1968 version: ‘Ciaran Hinds as the bisexual Achilles, in an astonishing performance which even surpasses Alan Howard’s once definitive portrayal, prowls suave, quiet and watchful in black leather and a nasty smile. He exudes all the charm of a python – except with his boyfriend Patroclus’ (de Jongh, 1990).

During the run at the Swan in 1990, de Jongh used the term ‘bisexual’ for Achilles, whilst most other reviewers were concentrating their description of the 250 character on his threatening, sinister quality. By the time the production transferred to the Barbican, a year later in the summer of 1991, there had been an enormous increase in the frequency of the use of the word ‘bisexual’ to describe Ciaran Hinds’

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 9 AFTA Footnotes

All that guff about Westron being related to the language of the Mark is completely true, but Faramir’s concerns about learning it without having someone to speak to are based in the relationship of modern vernacular English to Anglo Saxon/Old English. Terribly difficult to parse in writing, infinitely easier (though not easy!) to do in speech.

“His leg healed with impressive speech,” not because there’s a medical reason for this, but because I am, let’s say, a fucking goblin with no serious commitment to realistic portrayals of injury. Amen.

The Galadriel comparison is my hobby horse. I hate the fanon interpretation that the White Lady comment is because she wears white. It’s not!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! Only two people are called the “White Lady” in LOTR: Galadriel and Éowyn, and only one person refers to both of them as that, and it’s F A R A M I R. Motherfucker knows what he’s doing!

Okay so, heavy sigh, this Númenórean clear sight stuff was/is really difficult for me to manage, so my guiding logic for it is something along the lines of a radio. All the channels are there, just out in the ether (hello Tesla!) but you can’t hear all of them at once. You can tune into them, and some might be fuzzier than others based on your proximity to the source, outside interference, etc, or you can accidentally hit the ‘scan’ button on your radio and be subjected to a whole bunch in rapid succession. But also, given that I’ve had to use modern technology for comparison, I envision this being a particularly frustrating thing for Faramir and Denethor to explain, especially given that they have basically never interacted with the Elves who have a similar shtick going on.

The dance is a Pavane, a traditional processional Renaissance dance. Incredibly funny to imagine how furious Éowyn must’ve been trying to dance that sucker. So stilted!

I think Faramir’s line about “I would not have you think me foolish,” might be a bit problematic for some fanon characterisations, but I think I legitimise that entirely from his “Do you not love me, or will you not?” line, which actually seems to me to be a pretty overt desire for approval. I think it’s important that the only other person we see him asking for approval from is Denethor, while with everyone else he just obviously doesn’t give a fuck, because I think him going out of his way to seek verbal affirmation is very, very much a sign of his personal respect for someone. And I think it’s really important to notice how few and far between those instances are — he is not, as I think is quite popular to imagine especially amongst movie fans, desperate for everybody’s approval. He knows whose opinion he cares about and is intent on getting it, but he’s selective. And I also think there’s kind of a cynical element to it, by asking these people to vocalise their approval of him, he’s getting them to emotionally commit to it. Once it’s out there, it’s out there, and it’s much more difficult to take it back. Which is why I think it’s significant that Denethor basically sees right through it and tells him to fuck off, he knows exactly what sort of game Faramir’s playing. I want to make it clear here that I don’t think this is Faramir, like, consciously manipulating Éowyn or anything, I just think this is how he’s been socialised and so it comes naturally to him.

I have almost certainly gotten something wrong about the Rohirrim not patrolling the Anduin, and I’m sure Tolkien’s got an appendix to the Unfinished Tales or whatever explaining that actually they had the most successful river navy in M-E or whatever, but it’s not narratively helpful to me so we’re just gonna accept that they broadly leave the Anduin untouched.

Éowyn’s attitude to sex is, to be clear, not unprecedented in (our) medieval era. See: the Decameron, the Heptameron (sort of — she’s careful to nuance sex generally), Chaucer’s Wife of Bath and Troilus and Criseyde, the letters of Abelard and Heloise, the implications of quite a lot of the Lancelot stories, the erotic language of eg. Dante’s Purgatorio and Paradiso, etc. Sex is there, sex is happening, it’s not such a stretch to imagine that someone who sees herself as largely socially secure would find virginity and sexuality more of a burden than a tool.

Jasmine growing in the garden, not necessarily accurate for a lot of the visions of Gondor as England or France, but if you, like me, are enamoured with Gondor as Byzantium, then yes, jasmine grows. Hell yeah baby.

The would not/could not distinction is basically the summation of Faramir’s character to me so I busted ass to get that in there lol. I think too often fans think that he could not be a brutal, cynical warrior. He could, he so obviously could, but he consistently makes the choice not to be.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Geoffrey Chaucer Biography

Chaucer has presented exemplifications of himself again and again — in such early poems as The Book of the Duchess, The Parliment of Fowles, Troilus and Criseyde, The House of Fame, and The Legend of Good Women, and besides in his masterpiece, The Canterbury Tales. Chaucer's narrators are, clearly, not the "certifiable" Chaucer — other than in certain real respects — yet the various kid's shows share much for all aims and reason with one another and totally uncover, either directly or indirectly, what Chaucer regarded in a man.

Aside from the Troilus narrator, an extraordinarily jumbled and special case, all of Chaucer's narrators are learned, fat, nearsighted, amusingly self-ingested, to some degree self righteous, fictionistic poet chaucer life and personality detailed biography and plainly — by virtue of a significant shortfall of affectability and refinement — out and out vain in the focal specialty of obsolete holy people: love. We may be really sure that the significant and mental qualities in these embellishments are not really Chaucer's. Chaucer's real shortfall of vainglory, affectedness, and indecency lies at the center of our response to the comic self-portrayals wherein he affirms for himself these flaws.

A conclusive effect of Chaucer's refrain is acceptable, anyway it is missing to depict Chaucer as a moralist, significantly less as a joke artist. He is a lovely onlooker of humankind, a storyteller, similarly as a comedian, one whose satire is generally without veritable eat. He is in like manner a reformer, yet he is boss a celebrator of life who comments keenly on human ineptitudes while being, at the same time, an admirer of mankind.

Most unmistakable English craftsman of the Middle Ages; b. London, c. 1340–45; d. there, Oct. 25, 1400. From suffering position records, Chaucer would appear to have been an appropriately productive local area specialist. He was working class by birth, the relative of a prosperous family since quite a while past associated with London and the wine trade. The main records (1357) place him as a person from the group of Elizabeth, Countess of Ulster and companion of Lionel, third offspring of the legitimate ruler, Edward III. Chaucer's father, John Chaucer, had adequately made a beginning on the side of the crown, and the presence in a good group of the offspring of a rich normal was not unexpected during that period.

Life. The particular thought of Chaucer's underlying mentoring is uncertain, anyway another kind of his tutoring isn't. He went with the mission to France in 1359, apparently as a person from the association of Lionel, and was gotten and conveyed. He apparently rejoined the military and was accessible at the Peace of Brétigny (1360). The situation of Chaucer's strategic assistance is critical, considering the way that the mission

1 note

·

View note

Text

i like how troilus and cressida is basically a fanfiction of a fanfiction about a OC and a secondary character that is so accepted that is basically considered canon of a fanfiction of a legend that may have or may have not happened

#never disreslect fanfiction writers#they have been there since the beginning#troilus and cressida#shakespeare#shitposts#memes

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

slow on the uptake and it quite sure what you have/haven't answered so: a number you haven't been asked yet but want to answer (if there is one) for the meme thing

This meme has been amazingly fruitful - I’m used to reblogging a meme and getting 0-2 responses so I’m a little stunned lol. There were 4 questions left so I did them and posted another excerpt because I could. :D

3: Does your WIP have a title? If so, explain its significance. If not, what are you calling it for now?

I have no title for the Eleanor novel. I was briefly considered “Lady of Shadows” but ended up hating it. I’m thinking I should probably try mining some of the contemporary writings about Eleanor or something like Troilus and Criseyde which plays a significant part in the narrative.

For the Henry V novels I have:

The Brittle Crown: specifically because it deals with Richard II’s deposition and the sense that there is no security in the crown.

The Bloody Field: about the Battle of Shrewsbury. I’m not totally happy with it because it’s very clearly linked to Edith Pargeter’s A Bloody Field By Shrewsbury, and, through that, Shakespeare. So I want something a bit more... my own thing.

The Deaths of Kings: about Henry IV’s physical death and Henry V’s metaphorical death as he becomes king. Again, not too happy with this one but it’s very fitting.

Sword Year: Agincourt!! I love this one.

The Perfect King: aka Ian Mortimer’s going to write a strongly worded tweet about this. In my defence, I named it that because this book is where the questions about kingship really come home to roost and one of my notes is, “the perfect king is a dead king”.

10: How would you describe your WIP’s narrative style? (1st person, 3rd person, multiple POVs, single POV, alternating chapters, etc.)